Abstract

Tuberculosis is the second cause in infectious diseases leading to human death. Understanding the virulence mechanism is inevitable if the disease needs to be fully cured. Therefore, this study aimed to reveal this mechanism by comparing proteomic profiles of intracellular and extracellular virulent strain M.tb and bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) from infected THP-1cells. First, M.tb and BCG infected THP-1 at MOI 10:1. Twelve hours postinfection, intracellular bacteria of M.tb and BCG were collected, whereas the two bacilli cultured in 7H9 broth media were used as the control. Then four groups of bacilli were subjected to proteomic analysis, and differential proteomic profiles between M.tb and BCG were comparatively analyzed with bioinformatics tools. As a result, we identified a total of 1,557 proteins. Further, they were divided into four groups for comparison of M.tb versus BCG under 7H9 culture (shorten as out), M.tb in (intracellular) versus M.tb out, BCG in versus BCG out and M.tb in versus BCG in. Between M.tb in versus BCG in, a total of 211 differentially expressed proteins were found. Eight proteins like ESAT-6 distributed in six RDs and some known proteins related to virulence. Besides, five uncharacterized proteins were differentially expressed. Further analysis revealed enriched pathways were associated with glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism pathways. In M.tb out versus BCG out, a total of 144 differential proteins were identified and mainly involved in metabolism pathways. Then, 121 differential proteins in the group of M.tb in versus M.tb out were enriched in ribosome and oxidative phosphorylation related to adaptation to the host environment. The group of BCG in versus BCG out shared the same trend of different pathways to the M.tb in versus M.tb out. Finally, 42 proteins were identified to be up-regulated only in intracellular M.tb including eight RD proteins, whereas 22 up-regulated uniquely in intracellular BCG. Besides, only two proteins (Pks13 and Rv1405c) were commonly up-regulated in intracellular M.tb and BCG. Further, some unknown proteins were uniquely up-regulated in the intracellular M.tb and BCG. These findings provide valuable data for further exploration of molecular mechanism for M.tb virulence and BCG immune response.

Keywords: tuberculosis, M.tb, BCG, proteomics, macrophages, virulence

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), the etiologic agent of tuberculosis (TB), remains a serious global public health threat. As an extremely successful intracellular bacteria, M.tb can survive and cause disease correlated to their unique immune evasion mechanism. Despite the availability of anti-TB drugs, the normal treatment time lasts 6 to 12 months. In addition, increasing multidrug-resistant TB and extensively drug-resistant TB are bringing great difficulties to realize End-TB strategy proposed by the World Health Organization (Cohen et al., 2019).

Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of M. bovis that developed more than a century ago and remains the only licensed TB vaccine in humans for 100 years. Although the efficacy of BCG against active TB in adults has been challenged, it saves millions of lives by preventing severe, miliary, and meningeal TB, especially for children (Zhu et al., 2018). Genomic comparisons reveal at least 18 variable regions of difference (named RDs) representing more than 100 genes are deleted in BCG but present in M.tb. For example, the RD1 region contains ESAT-6 system and PE and PPE proteins, whereas the RD2 region includes MPT6, transcriptional regulator, and others (Brosch et al., 2001).

M.tb is an intracellular pathogen and mainly resides in macrophages and dendritic cells. To establish an infection, M.tb should internalize the host cells, survive, and reproduce in the environment of phagosomes with low pH, oxygen, and starvation. Further, the bacteria should win the fight of host defense called innate immunity including inflammatory responses (Liu et al., 2017), antimicrobial peptides, toxic antimicrobial effectors such as nitric oxide, or reactive oxygen intermediates in macrophages (Weiss and Schaible, 2015).

With coevolution of M.tb and the hosts, M.tb has evolved a series of strategies to evade immune responses and remains persistent infection for a long term in the hosts. For instance, M.tb is capable of recruiting GTPase Rab5 from phagosomes to inhibit phagolysosome maturation (Carranza and Chavez-Galan, 2019). In addition, M.tb can produce lots of 1-tuberculosinyladenosine and be selectively accumulated in the host cells to change its cellular microenvironment as a bacterial antacid after infection. This bacillus can utilize the host’s ubiquitination system to suppress host immune response (Wang et al., 2020) and mediate cellular events such as apoptosis and autophagy via various approaches such as miRNA (Li et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Evasion of TLR or NLR signaling and C-type lectin receptor signaling also help M.tb to resist the host innate immunity (Goldberg et al., 2014).

However, up to now, the virulence mechanism of M.tb is far away from complete understanding. To reveal the differential proteomic profiles between intracellular M.tb and BCG under infection would reveal the new mechanism to understand the virulence of M.tb and TB pathogenesis.

In this article, by using a model of macrophages infected with virulent M.tb and attenuated strains BCG, we compared the different proteomics of intracellular M.tb and BCG by using the cultured bacteria as the controls. The enriched differential pathways and individual proteins related to virulence would provide evidence for further elucidation of M.tb virulence and TB pathogenesis.

Methods

Bacterial Strains and Cell Culture

M.tb 1,458 strain (GenBank accession no. NZ_CP013475) is a strain of bovine origin isolated by the National Animal Tuberculosis Para-Reference Laboratory (Wuhan) at Huazhong agricultural university, Wuhan, China (Xiong et al., 2017). BCG Tokyo 172 (ATCC 35737, GenBank accession no.GCA_000010685.1) was a kind gift from Prof. Junyan Liu (School of Basic Medicine Sciences, Wuhan University, China). Both strains were grown in broth medium Middlebrook 7H9 with 10% of oleic acid–albumin–dextrose–catalase (BD, Franklin, NJ, United States), 0.5% glycerol (Sigma–Aldrich), and 0.05% Tween 80 (Sigma–Aldrich) at 37°C. The human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 (ATCC TIB-202) was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone, United States) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, United States) with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Infection Model of THP-1 Cells

THP-1 cells were seeded at 30 × 106 cells/well in a 145-mm cell culture dish and differentiated with 40 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, United States) for 12 h, at 37°C. For infection, the two logarithmic growing cultures (M.tb and BCG) were centrifuged and resuspended with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco). The bacterial concentrations (colony-forming units/ml) were estimated by measuring the OD600 values and infected at MOI (BCG, or MTB-1458: THP-1cells) of 10:1. After 12 h, the extracellular bacteria in the culture medium were collected. The cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 fresh medium and incubated with a fresh RPMI 1640 medium containing 100 µg/ml gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria.

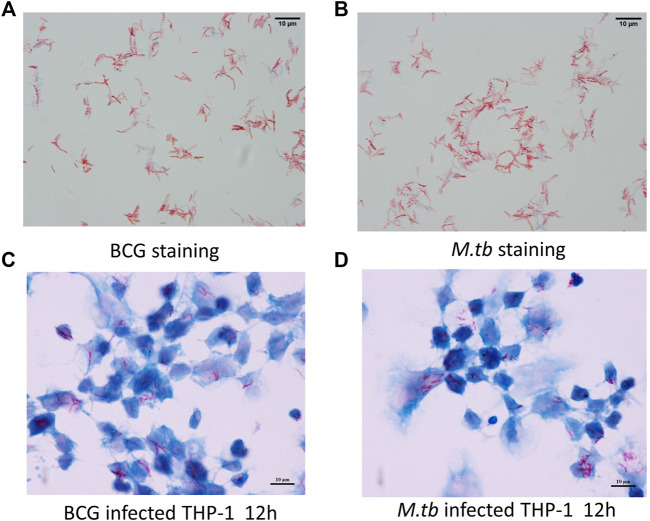

The bacteria were confirmed by acid-fast staining. Briefly, the smears of infected THP-1 cells were permeabilized with 0.4% triton X-100 for 10 min and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. Finally, the acid-fast staining was performed using acid-fast staining solution kit (Yuan Ye Biological Technology, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Extraction of Bacterial Proteomics and iTRAQ Labeling

For intracellular bacterial proteins, the infected cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, United States) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and subjected to be centrifuged for 15,000g for 2 min at 4°C. The pellet was collected and added 1 ml 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for resuspension.

Bacteria growing to logarithmic phase were centrifuged at 4,000g for 10 min. The pelleted washed by HBSS and centrifuged at 4,000g for 10 min. Then, 1 ml HBSS was resuspended, pelleted, and further lysed with sonication. The parameters were set as 1 s/1-s intervals, 3-min time, and 80-W power. After sonication, the samples were centrifuged at 15,000g for 15 min to remove insoluble particles, repeated once to further exclude precipitation. The bacterial proteins that contained membrane proteins were collected, and the concentration was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime). Finally, the sample was stored at −80°C for the following steps.

For tryptic digestion and iTRAQ labeling, 50 µg of each protein sample was mixed with 120 µl reduction buffer (10 mM DTT, 8 M urea, 100 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), pH 8.0) on a 10 K ultrafiltration tube, and incubated at 60°C for 1 h, and then IAA (3-indoleacetic acid) was added at a final concentration of 50 mM and stayed at room temperature for 40 min under protection from light. The solution was then centrifuged on the filter at 12,000g for 20 min at 4°C and the concentrated protein solution on the filter was added 100 µL of TEAB (100 mM) and centrifuged at 12,000g for 20 min. Then 100 µl of 100 mM TEAB and 2 µl trypsin (1 µg/µl) were added to each tube and then incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Finally, the digested peptides were centrifuged at 12,000g for 20 min, 50 µl of 100 mM TEAB were added and repeated centrifugation again. The generated peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation and re-dissolved with 100 µl of 0.5 mM TEAB. The 40 µl of each sample were transferred into a new tube and 100 µl of the iTRAQ label reagent dissolved in isopropanol was added. Finally, 200 µl of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) water were added and incubated for 30 min to terminate the reaction.

Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatographic and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

A 1100 HPLC system (Agilent) was used for reversed-phase (RP) chromatographic separation with an Agilent Zorbax Extend RP column (5 µm, 150 × 2.1 mm). Mobile phases A (2% acetonitrile in HPLC water) and B (98% acetonitrile in HPLC water) were used for the RP gradient. Trypsin peptides were separated at a steady flow rate of 300 µl/min, monitored at 210 and 280 nm. Then elution buffer at every minute was collected, lasting for 8–50 min. The separated peptides were lyophilized for mass spectrometer (MS) detection as follows.

All analyses were performed by a Q-Exactive MS (Thermo, United States) equipped with a nanospray flex source (Thermo, United States). The peptides were separated on a C18 analytical RP column (75 µm × 15 cm) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min and a linear gradient of 70 min. A full MS scan was obtained in the mass range of 300 to 1600 m/z. Ten strongest peaks in the MS were fragmented by high-energy collision dissociation. The resolution of the obtained MS/MS spectrum is 17,500 with the maximum injection time of 50 ms. Q-E dynamic exclusion was set to 15 s.

All of the Q exactive MS/MS raw data were analyzed by using proteome discoverer v.2.2 (Thermo Company, United States) software and the uniprot-M.tb database. The false-positive rate of peptide identification was controlled below 1%.

Bioinformatics Analysis

To compare the proteomics with 1,557 proteins, we divided them into four groups. Among them, the intracellular bacteria of M.tb and BCG from the macrophages were defined M.tb in and BCG in, whereas the extracellular bacteria cultured in 7H9 medium were defined M.tb out and BCG out. So, the four groups are BCG in versus M.tb in, BCG out versus M.tb out, M.tb in vs. M.tb out, and BCG in vs. BCG out.

Database searches were performed for proteins analyzed by RP liquid chromatography and MS. Experimental data were analyzed by Proteome Discoverer™ 2.2 (Thermo, United States) software. The data are from the Uniprot–Mycobacterium tuberculosis database. For the obtained search results, only unique peptides were contained for iTRAQ labeling quantification, and peptides with global false discovery rate (FDR) values from fit less than 1% were considered for further analysis. Based on the screened credible proteins, the difference multiple fold change (FC) value and difference significance p value of each comparison group were calculated. The proteins with significant differences were screened according to the criteria of FC >1.5 or FC < 2/3 and p < 0.05. Different proteins in four groups were analyzed by heatmaps and volcano plots based on a threshold FC >1.5 and p-value < 0.05. Using the OmicsBean omics data integration analysis cloud platform (http://www.omicsbean.cn/), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis was performed on the selected differential proteins. The KEGG analysis was used corrected p-value < 0.05 as a threshold for finding significantly enriched terms in the input list of differentially expressed proteins. To find the shared mechanism for both M.tb and BCG necessary mechanism to infection, the differential proteins with twofold difference were checked to analyze and identify commonly regulated proteins in different groups.

Results

Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation of Protein Samples

By using fast-acid staining, the smear showed M.tb and BCG in red and THP-1 in blue, demonstrating the infection was successful (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Infection model. PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were infected with M.tb and BCG for 12 h. Ziehl–Neelsen staining of the BCG in vitro cultured (A) and M.tb (B). Ziehl–Neelsen staining to detect the survival of BCG (C) and M.tb (D) in THP-1 cells.

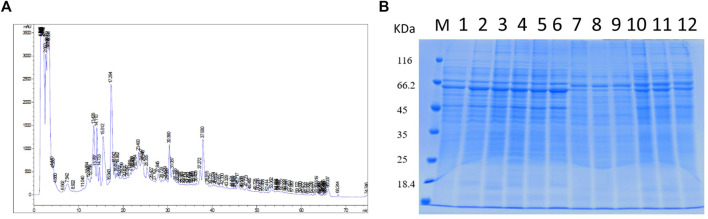

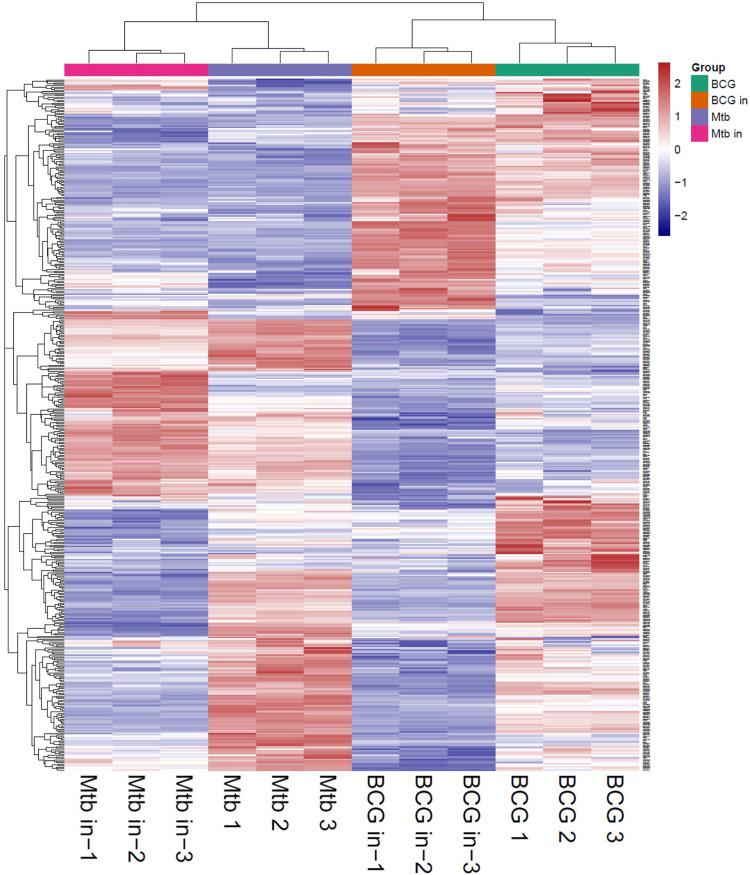

The proteins collected from the bacteria were analyzed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and RP chromatography (Figure 2). Combining the two checking methods, the replicates from the same experiment showed the similar trend representing that the extraction methods were reliable for further analysis. In addition, Table 1 showed the sample concentrations were sufficient for analysis. First, all the MS data of four bacterial samples (BCG in and BCG out, M.tb in and M.tb out) each in triplicate numbering 1 to 3 were divided into three groups 1, 2, and 3 by pooling the same number of the group into one group first for analysis of qualitative proteins by base search. Then, the data were filtered with a global FDR < 0.01 to obtain quantitative protein 1 to 3. Finally, we identified 2,442, 2,625, and 2,584 valid proteins for groups 1 to 3 samples (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). In the clustering analysis of the proteins according to different conditions revealed in the group of BCG in and M.tb in, 211 differentiated proteins were found, and half of them shared by BCG in and M.tb in, and another half were different. In the group of M.tb in and M.tb out, two-thirds of the total proteins were shared with similar change trend, whereas the remaining one-third proteins showed opposite trends. The same situation was found in the group of BCG in and BCG out. However, when proteomics of BCG out and M.tb out were compared, only one-third of the total proteins were shared with similar change trend, whereas the remaining two-thirds proteins showed opposite trends (Figure 3). Taken together, both the intracellular environment and virulence differences affected the expression of proteomics of BCG and M.tb.

FIGURE 2.

Quality control and overall primary results. (A) Extract the total protein in the sample and take out a part for protein concentration determination to SDS-PAGE detection. The molecular weights from top to bottom are as follows: 116, 66.2, 45,35, 25, and 18.4 (kDa). (B) High-pH RP chromatography separation peak diagram. The protein is trypsinized and labeled, and then the same amount of each labeled sample is mixed for chromatographic separation.1–12: BCG in-1, BCG in-2, BCG in-3, M.tb in-1, M.tb in-2, M.tb in-3, BCG1, BCG2, BCG3, M.tb1, M.tb 2, M.tb 3.

TABLE 1.

The absorbance and concentrations.

| Number | Absorbance 1 | Absorbance 2 | Absorbance 3 | Average absorbance | Concentration (µg/µL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG in 1 | 0.086 | 0.079 | 0.08 | 0.082 | 0.793 |

| BCG in 2 | 0.116 | 0.105 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 1.078 |

| BCG in 3 | 0.201 | 0.187 | 0.187 | 0.192 | 1.874 |

| M.tb in 1 | 0.25 | 0.243 | 0.241 | 0.245 | 2.394 |

| M.tb in 2 | 0.097 | 0.089 | 0.091 | 0.092 | 0.898 |

| M.tb in 3 | 0.106 | 0.099 | 0.098 | 0.101 | 0.983 |

| BCG 1 | 0.071 | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.067 | 0.646 |

| BCG 2 | 0.062 | 0.059 | 0.055 | 0.059 | 0.567 |

| BCG 3 | 0.079 | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.072 | 0.698 |

| M.tb 1 | 0.256 | 0.239 | 0.244 | 0.246 | 2.410 |

| M.tb 2 | 0.323 | 0.303 | 0.311 | 0.312 | 3.059 |

| M.tb 3 | 0.249 | 0.233 | 0.237 | 0.240 | 2.345 |

TABLE 2.

The reliable numbers of the proteins identified.

| Protein type | Qualitative protein 1 | Quantitative protein 1 | Qualitative protein 2 | Quantitative protein 2 | Qualitative protein 3 | Quantitative protein 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDR <1% | 2,634 | 2,442 | 2,828 | 2,625 | 2,797 | 2,584 |

FIGURE 3.

Heatmap of all groups (M.tb, intracellular M.tb, BCG, and intracellular BCG). Heatmap of proteins differentially expressed in all groups. Blue-to-red scale indicates low-to-high proteins expression levels. Differentially expressed proteins were defined based on a threshold fold change >1.5, at p < 0.05.

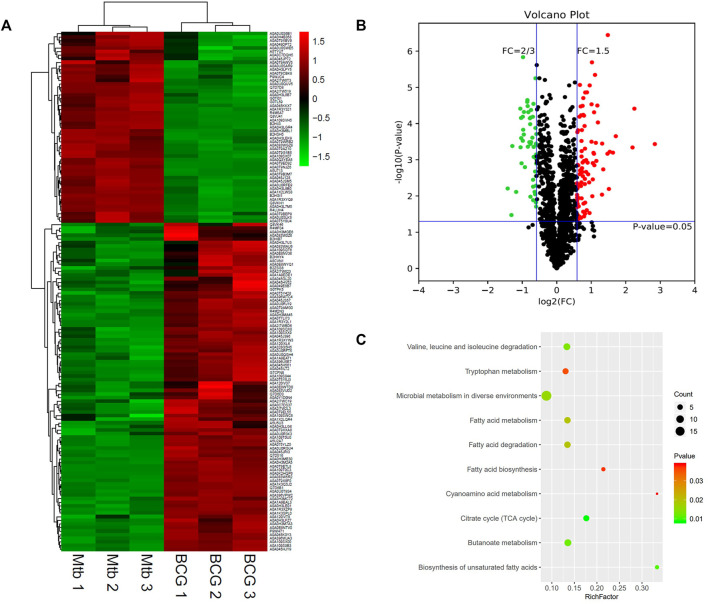

Differentiated Protein Expression Between BCG in and M.tb in During the Infection of Macrophages (BCG In vs. M.tb In)

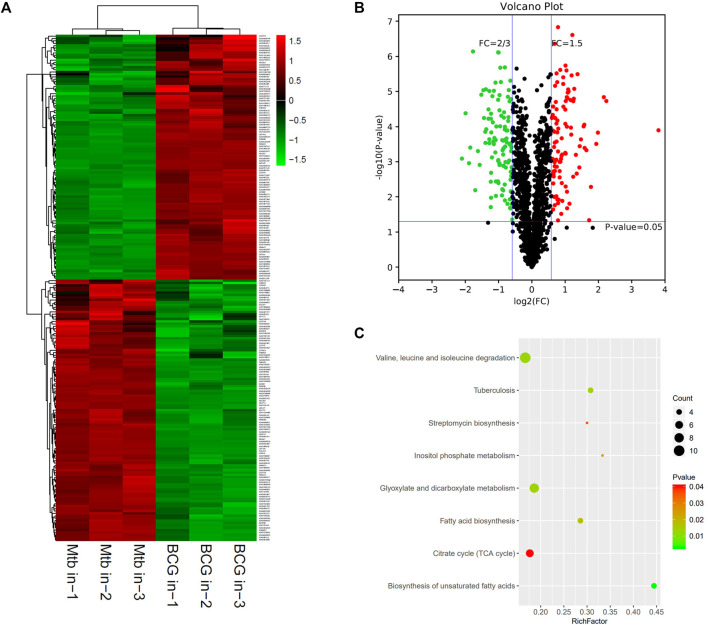

The proteomic profiles of BCG in vs. M.tb in were comparatively analyzed. The dysregulated proteins total to 211 between the intracellular M.tb and BCG. Almost equal numbers of genes were down-regulated (109) and up-regulated (102). Compared with the group of BCG out and M.tb out, their gene expression profiles in this group showed more diversity (Figures 4A,B). The top 10 up-regulated proteins in BCG compared with M.tb include RpsA, FadD29, Rv1473, Rv3699, SseA, Rv1358, Rv2588c, Rv1762c, Pks13, and Rv0025; among them, RpsA, the 30 S ribosomal protein S1, was mostly up-regulated (13.9-fold up). Rv2588c, Rv1762c, and Rv0025 were the proteins uncharacterized (Supplementary Table S2). On the contrary, the top 10 down-regulated proteins in BCG compared with M.tb include LppE, Rv3099c, PncB2, Rv1498A, VapB19, PstS1, Rv0795, Rv1817, Gnd1, and TB22.2, among them, TB22.2 was mostly down-regulated (five folds down) (Table 3). TB22.2 (Rv3036c), as a surface-anchored esterase, may play a role in structurally modifying the cell wall composition when M.tb infection (Trivedi et al., 2005). In addition, of the top 10 down-regulated proteins in BCG compared with M.tb, some differential known proteins including PPE family (PPE41 and PPE51) and RD regions EspK (RD1), EsxA (RD1), EsxO (RD7), LpqG (RD9), Rv0223c (RD4), epiA (RD6), Rv2073c (RD12), and Rv1513 (RD6). The functional studies of Rv2073c, EpiA, and Rv1513 remain not clear and deserve further study.

FIGURE 4.

Different protein profile between intracellular BCG and intracellular M.tb. (A) Heatmap of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular BCG and intracellular M.tb. Green-to-red scale indicates low-to-high proteins expression levels (p < 0.05). (B) Volcano plots of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular BCG and intracellular M.tb. The red dots on the right indicate the significantly upregulated proteins, whereas the downregulated are shown with green dots on the left. Differentially expressed proteins were defined based on a threshold fold change >1.5, at p < 0.05. (C) Top10 KEGG pathways (only eight in this group) enriched for the significantly differentially expressed proteins. Entries with larger bubbles contain more differential genes. The color of the bubbles indicates the p value. The smaller the enrichment p value means the greater the degree of significance (p < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

The top10 differentially expressed proteins between intracellular BCG and M.tb.

| Genes | Fold change | UNIPROT_URL | Annotation | Differential expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpsA | 13.94335938 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH43 | rpsA–30S ribosomal protein S1 | Up |

| fadD29 | 4.713255185 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P95141 | Long-chain fatty acid–AMP ligase FadD29 | Up |

| Rv1473 | 4.471317829 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53164 | Macrolide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | Up |

| Rv3699 | 3.954741379 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O69667 | Hypothetical protein | Up |

| SseA | 3.82406015 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WHF7 | Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase SseA | Up |

| Rv1358 | 3.421887391 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q11028 | Transcriptional regulator | Up |

| Rv2588c | 3.295882763 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WL75 | Membrane protein secretion factor YajC | Up |

| Rv1762c | 3.112998041 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O06797 | Hypothetical protein | Up |

| pks13 | 2.997491219 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6X8D2 | Polyketide synthase | Up |

| Rv0025 | 2.979821958 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMA1 | Hypothetical protein | Up |

| lppE | 0.369435344 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O07750 | Lipoprotein LppE | Down |

| Rv3099c | 0.364488171 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O05777 | Hypothetical protein | Down |

| pncB2 | 0.349864499 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WJI7 | Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase PncB2 | Down |

| Rv1498A | 0.325813729 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6XY36 | Hypothetical protein | Down |

| vapB19 | 0.308091531 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P95006 | Antitoxin VapB19 | Down |

| pstS1 | 0.293881008 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WGU1 | Phosphate ABC transporter substrate–binding lipoprotein PstS | Down |

| Rv0795 | 0.277755018 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WKH5 | Hypothetical protein | Down |

| Rv1817 | 0.270431497 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q50616 | Flavoprotein | Down |

| gnd1 | 0.251934327 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q79FJ2 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | Down |

| TB22.2 | 0.233486401 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6YF08 | Cell wall–anchored esterase | Down |

KEGG pathway of the differential expressed genes was further performed and showed that glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism; valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation; and TB are the top three pathways enriched (Figure 4C). Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism is essential for mycobacterial persistence; the enzymes of the glyoxylate cycle are activated during adaption to low oxygen environment. As glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism was upregulated more in intracellular BCG than M.tb, it might be used by BCG to adapt to the environment within macrophages. On the other hand, the intracellular M.tb relies more on TB pathway than BCG shown by the differential proteins including ESAT-6 (esxA), a protein in RD1, pstS1, and lprA up-regulated, whereas pstS3 down-regulated in M.tb compared with BCG.

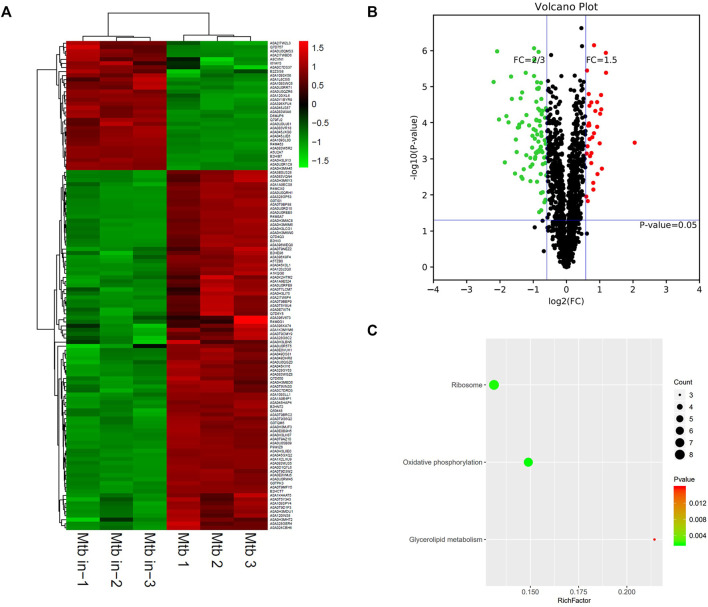

Differential Proteomic Profiles Between BCG and M.tb in Medium Culture (BCG Out vs. M.tb Out)

The differential proteomics between BCG out and M.tb out was analyzed. The cluster heatmap showed that both BCG and M.tb samples were clustered into two groups. In M.tb, there are more genes downregulated, whereas the trend was opposite in BCG samples (Figure 5A). Based on the trusted protein of M.tb selected, 91 proteins were upregulated and 53 downregulated in BCG (Figure 5B). The top 10 up-regulated proteins in BCG compared with M.tb include RpsA, FadD29, Rv1358, Rv3699, Rv1473, SseA, Rv3406, GltD, Ino1, and Pks13. Among them, RpsA was also the top1 up-regulation proteins, same as the group of M.tb in and BCG in (7.1-fold up). Rv3699 was uncharacterized, and Rv1358 was defined as transcriptional regulator, but the detailed functions remain unknown (Supplementary Table S2). On the contrary, the top 10 down-regulated proteins in BCG compared with M.tb include MmaA4,DesA1,PncB2,Rv0248c, Rv0247c, FadD15, Rv1817, HupB, FadD28, and Rv1514c; among them, Rv1514c was mostly down-regulated (two-point sevenfold down) (Table 4). For Rv1514c, the binding site prediction confirmed it might be bounded with UDP (uridine-diphosphate), and it could be a transferase activity protein, which possibly transfers glycosyl group action (Beg et al., 2018). It gives us the hint that M.tb needs more glycosyltransferase than BCG. Rv1817, relevant with oxidoreductase activity, was found dropped significantly in BCG compared with M.tb. The functions of genes Rv1358 and Rv3699 remain unknown in M.tb or BCG (Supplementary Table S2). In addition, of the top 10 proteins, Hsp and pstS3 were up-regulated in BCG compared with M.tb and play an important role in knowing the mechanism of protective immune responses against TB. It has been reported that heat shock protein (Hsp) generates production in low-virulence strains of mycobacteria to help persist in host macrophages and a crucial chaperon protein necessary for the survival of M.tb in the dormant phase (Dubaniewicz, 2010). Psts3 is a surface-exposed phosphate transport receptor. The use of DNA vaccine encoding pstS3 to trigger immune response can significantly protect mice attacked by M.tb (Tanghe et al., 1999).

FIGURE 5.

Differential protein profile between M.tb and BCG. (A) Heatmap of proteins differentially expressed between the group of M.tb and BCG. Green-to-red scale indicates low-to-high proteins expression levels (p < 0.05). (B) Volcano plots of proteins differentially expressed between the group of M.tb and BCG. The red dots on the right indicate the significantly upregulated proteins, whereas the downregulated proteins are shown with green dots on the left. Differentially expressed proteins were defined based on a threshold fold change >1.5, at p < 0.05. (C) The top 10 KEGG pathways enriched for the significantly differentially expressed proteins. Entries with larger bubbles contain more differential genes. The color of the bubbles indicates the p value. The smaller the enrichment p value means the greater the degree of significance (p < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

The top 10 differentially expressed proteins in BCG based on M.tb.

| Genes | Fold change | UNIPROT_URL | Annotation | Differential expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpsA | 7.17481203 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH43 | 30s ribosomal protein s1 rpsa | Up |

| fadD29 | 4.75609756 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P95141 | Fatty acid–CoA ligase | Up |

| Rv1358 | 4.58123371 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q11028 | Uncharacterized protein | Up |

| Rv3699 | 3.27470687 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O69667 | Uncharacterized protein | Up |

| Rv1473 | 3.0910596 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53164 | Probable macrolide-transport ATP-binding protein ABC transporter | Up |

| SseA | 2.89811584 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WHF7 | Maf-like protein | Up |

| Rv3406 | 2.85041908 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WKZ1 | Oxidoreductase | Up |

| ino1 | 2.78947368 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WKI1 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase | Up |

| gltD | 2.7698665 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WN19 | Putative NADH-dependent glutamate synthase (small subunit) | Up |

| pks13 | 2.54393673 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6X8D2 | 4-Carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase | Up |

| mmaA4 | 0.50533896 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q79FX8 | Hydroxymycolate synthase | Down |

| desA1 | 0.49308961 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNZ7 | Acyl-ACP desaturase DesA | Down |

| Rv0248c | 0.48947697 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53670 | Fumarate reductase/succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit | Down |

| Rv0247c | 0.48825875 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53669 | Succinate dehydrogenase | Down |

| pncB2 | 0.48340731 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WJI7 | Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase PncB2 | Down |

| fadD15 | 0.48100993 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53521 | Long-chain fatty acid–CoA ligase FadD15, putative | Down |

| Rv1817 | 0.44241645 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q50616 | 3-Ketosteroid-delta-1-dehydrogenase | Down |

| hupB | 0.40947969 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMK7 | DNA-binding protein Hu | Down |

| fadD28 | 0.40220787 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WQ59 | Long-chain fatty acid–AMP ligase FadD28 | Down |

| Rv1514c | 0.37287415 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMX9 | Glycosyltransferase | Down |

Further KEGG analysis showed the top three pathways enriched in microbial metabolism in diverse environments, fatty acid metabolism, and citrate cycle (TCA cycle) (Figure 5C). For BCG, the genes related to microbial metabolism in diverse environments are upregulated, whereas six differential genes involved in TCA cycle were enriched including acn, Rv0247c, Rv0248c, KorA, Rv0794c, and SdhD; among them, the expression of Rv0247c, Rv0248c, KorA, and Rv0794c was increased in M.tb, whereas the expression of Acn and SdhD upregulated in BCG. TCA cycle pathway is known to produce energy, lipid, heme, and other precursors in M.tb (Tian et al., 2005). It suggests that M.tb in medium culture relies on TCA cycle more than BCG.

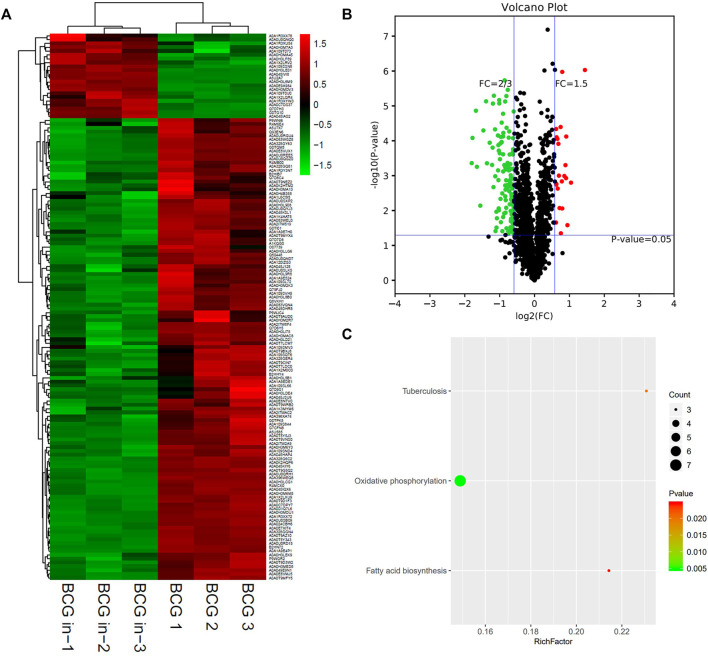

Differential Protein Expression Between Intracellular and Extracellular M.tb During the Infection of Macrophages (M.tb In vs. M.tb Out)

Based on the trusted protein selected, 121 differentiated proteins between M.tb in versus M.tb out were found (Figure 6A). The clustering heatmap between M.tb in and M.tb out showed that most (>70%) of the differential genes are repressed in M.tb in of macrophages compared with M.tb out (Figure 6B). The top 10 up-regulated proteins in intracellular M.tb compared with extracellular M.tb include Rv1498A, RpsF, Rv1405c, TB22.2, Rv1928c, LppE, Rv2466c, PPE41, FbpB, and Rv1674c. Rv1498A was the mostly up-regulated (four point one folds up), but the protein currently uncharacterized. RspF, 30S ribosomal protein S6, was modified by ATP-dependent glutamate ligase RimK and affected bacterium growth (Pipa et al., 2019). Therefore, it might play an important role in understanding the mechanism of M.tb. We also found that virulence-related gene PPE41 and RD region protein RV0223C were significantly up-regulated. When M.tb infected macrophages, PPE41 has been shown to induce macrophage necrosis (Tundup et al., 2014). Contrarily, the top 10 down-regulated proteins in intracellular M.tb compared with extracellular M.tb include HupB, NuoL, EmbA, GadB, MmpL13b, Rv0338c, AftC, QcrB, RpmF, and EccD3; among them, EccD3 was mostly down-regulated (five folds down) (Table 5). Eccd3, as part of the ESX-3 specialized secretion system, is important for iron and zinc uptake or homeostasis. RpmF, a 50S ribosomal protein, is down-regulated nearly fivefold too. In addition, of the top 10 proteins, many FadD family proteins are up-regulated after M.tb infection like FadE7, FadD7, FadD16, and FadD2, which might be relevant with M.tb virulence mechanism.

FIGURE 6.

Different protein profile between intracellular M.tb and extracellular M.tb. (A) Heatmap of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular M.tb and extracellular M.tb. Green-to-red scale indicates low-to-high proteins expression levels (p < 0.05). (B) Volcano plots of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular M.tb and extracellular M.tb. The red dots on the right indicate the significantly upregulated proteins, whereas the downregulated are shown with green dots on the left. Differentially expressed proteins were defined based on a threshold fold change >1.5, at p < 0.05. (C) Top10 KEGG pathways (only three in this group) enriched for the significantly differentially expressed proteins. Entries with larger bubbles contain more differential genes. The color of the bubbles indicates the p value. The smaller the enrichment p value means the greater the degree of significance (p <0.05).

TABLE 5.

The top10 differentially expressed proteins between intracellular M.tb and extracellular M.tb.

| Genes | Fold change | UNIPROT_URL | Annotation | Differential expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv1498A | 4.140093396 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6XY36 | Uncharacterized protein | Up |

| rpsF | 2.279103053 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH31 | 30S ribosomal protein S6 | Up |

| Rv1405c | 2.26984127 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WLY7 | Putative methyltransferase | Up |

| TB22.2 | 2.091614333 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6YF08 | hypothetical protein | Up |

| Rv1928c | 2.063829787 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P95286 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | Up |

| lppE | 2.016712009 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O07750 | lipoprotein LppE | Up |

| Rv2466c | 1.998148148 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53193 | Uncharacterized protein | Up |

| PPE41 | 1.907282133 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q79FE1 | PPE family protein PPE41 | Up |

| fbpB | 1.894904459 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WQP1 | diacylglycerol acyltransferase/mycolyltransferase Ag85B | Up |

| Rv1674c | 1.893905192 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53921 | Transcriptional regulatory protein | Up |

| hupB | 0.348717035 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMK7 | DNA-binding protein Hu | Down |

| nuoL | 0.342380423 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WIW1 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit | Down |

| embA | 0.320856727 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNL9 | Arabinosyltransferase EmbA | Down |

| gadB | 0.315456165 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6YG46 | Glutamate decarboxylase GadB | Down |

| mmpL13b | 0.29913522 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O06546 | Trehalose monomycolate RND transporter MmpL3 | Down |

| Rv0338c | 0.286153846 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O33268 | Iron sulfur–binding protein | Down |

| aftC | 0.276993265 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMZ7 | α-(1->3)-Arabinofuranosyltransferase | Down |

| qcrB | 0.245286344 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WP37 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase cytochrome subunit B | Down |

| rpmF | 0.235881842 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH99 | 50S ribosomal protein | Down |

| eccD3 | 0.219337979 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNQ3 | ESX-3 secretion system protein EccD | Down |

KEGG pathway showed that differentiated genes were enriched on ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid biosynthesis (Figure 6C). A highly dynamic intracellular environment and the M.tb are encountered with constant pressure; therefore, the intracellular bacteria need to coordinate its metabolic activity to adapt either replication or quiescence statue. The key feature is to generate ATP via oxidative phosphorylation. Many bacteria transited into hibernation of ribosome when faced with stresses to growth; the M.tb also has to rearrange ribosome pathway to adapt to the environment. In conclusion, M.tb survival strategies are linked with ATP generation and ribosome regulation to commensurate with intracellular environment.

Differentiated Protein Expression Between Intracellular and Extracellular BCG During the Infection of Macrophages (BCG In vs. BCG Out)

Finally, we wanted to know how the expression profile of BCG, a vaccine strain, changed when BCG infects macrophages. Similar to intracellular M.tb, or even more trend was seen, most of the infected BCG’s proteins were inhibited compared with BCG control (Figure 7A). Both M.tb and BCG are silenced when it arrived in macrophages; this was consistent with the latent state of M.tb infection. In total, there were 142 differentiated proteins, with 22 proteins up-regulated and the remaining 120 proteins down-regulated between the group of BCG in and BCG out (Figure 7B). Furthermore, the detailed information of the top 10 is shown in Table 6. The top 10 up-regulated proteins in intracellular BCG compared with extracellular BCG include Rv1405c, Pks13, Rv1939, Rv3046c, RpsA, MtnP, MmsA, Rv0177, Rv0315, and Hsp. The top 1 protein of up-regulation is Rv1405c, with two-point sevenfold increasing. This protein is uncharacterized, and according to the Gene Ontology function annotations, it may have methyltransferase activity, hinting epigenetic modifications probably happened during the infection (Table 6). Another research showed Rv1405c might promote the intracellular survival of bacteria, but the detailed mechanism remains unknown (Healy et al., 2016). The top 10 down-regulated proteins in this group include EfpA, EmbA, MmpL7, RpmF, EccD5, EchA18, AftC, EccD3, QcrB, and NuoL. The NuoL is most significantly reduced protein among the list with the reduction three-point fivefold. It is a subunit of NDH-1 and may play a role in proton translocation. BCG oxidative activity counts more compared with M.tb. Besides, an unknown protein Rv1939 double its expression was identified, which is supposed to be a possible cobalamin synthetic protein (Supplementary Table S2). Of the top 10 proteins, LprG is an interesting protein up-regulated in intracellular BCG compared with extracellular BCG. LprG is a lipoprotein that modulates the host immune response against mycobacteria. Hovav et al. demonstrated that immunization with LprG induces a strong TH1 response, but Mariana Noelia Viale et al. found that the deletion of LprG can reduce the replication of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in bovine macrophages. It seems a paradoxical mechanism but revealed that lprG is a key protein for Mycobacterium (Viale et al., 2021).

FIGURE 7.

Different protein profile between intracellular BCG and extracellular BCG. (A) Heatmap of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular BCG and extracellular BCG. Green-to-red scale indicates low-to-high proteins expression levels (p < 0.05). (B) Volcano plots of proteins differentially expressed between the group of intracellular BCG and extracellular BCG. The red dots on the right indicate the significantly upregulated proteins, whereas the downregulated are shown with green dots on the left. Differentially expressed proteins were defined based on a threshold fold change >1.5, at p < 0.05. (C) Top10 KEGG pathways (only three in this group) enriched for the significantly differentially expressed proteins. Entries with larger bubbles contain more differential genes. The color of the bubbles indicates the p value. The smaller the enrichment p value means the greater the degree of significance (p < 0.05).

TABLE 6.

The top10 differentially expressed proteins between intracellular BCG and extracellular BCG.

| Genes | Fold change | UNIPROT_URL | Annotation | Differential expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv1405c | 2.721303732 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WLY7 | Methyltransferase | Up |

| pks13 | 2.063557858 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6X8D2 | Polyketide synthase | Up |

| Rv1939 | 1.922230951 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P95275 | Oxidoreductase | Up |

| Rv3046c | 1.877678224 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/I6YF16 | Hypothetical protein | Up |

| rpsA | 1.870317003 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH43 | Ribosomal protein SA | Up |

| mtnP | 1.848929421 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O06401 | S-methyl-5′-thioadenosine phosphorylase | Up |

| mmsA | 1.807692308 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53816 | Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | Up |

| Rv0177 | 1.734368071 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O07421 | Mce associated protein | Up |

| Rv0315 | 1.734160241 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O07242 | β-1,3-Glucanase | Up |

| Hsp | 1.719887955 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O53673 | Heat shock protein | Up |

| efpA | 0.430492136 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WJY5 | MFS-type transporter EfpA | Down |

| embA | 0.410486891 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNL9 | Arabinosyltransferase A | Down |

| mmpL7 | 0.388711395 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WJU7 | Transmembrane transport protein MmpL7 | Down |

| rpmF | 0.38203724 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WH99 | 50S ribosomal protein L32 | Down |

| eccD5 | 0.361902625 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNP9 | ESX-5 type VII secretion system protein EccD | Down |

| echA18 | 0.340576847 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O50402 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | Down |

| aftC | 0.318328667 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WMZ7 | α-(1->3)-Arabinofuranosyltransferase | Down |

| eccD3 | 0.312172088 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WNQ3 | ESX-3 secretion system protein EccD | Down |

| qcrB | 0.291623037 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WP37 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome C reductase cytochrome subunit B | Down |

| nuoL | 0.287162891 | http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P9WIW1 | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit L | Down |

Interestingly, KEGG pathway showed that oxidative phosphorylation was unique and most relevant in the group of BCG in vs. BCG, instead of both oxidative phosphorylation and ribosome in M.tb strains (Figure 7C). As the vaccine strain, BCG shares parts of the strategies with M.tb (containing the same genes in oxidative phosphorylation pathway: NuoL, QcrA, and QcrB), while it also lost other capacities to coordinate like ribosome pathway.

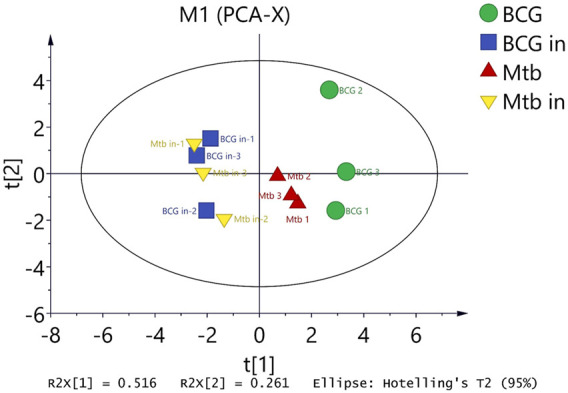

Principal Component Analysis

In summary, we could clearly show that BCG in and M.tb in clustered together, and BCG out and M.tb out clustered closer. But in between, there are clusters that form a separate group. At last, we used principal component analysis to summarize the different conditions. From the chart, we found the BCG was the farthest from the center; interestingly, the BCG in and M.tb in clustered as a whole separate group. M.tb group was close to both BCG and intracellular group but as a separate group (Figure 8). The information here showed that although M.tb and its vaccine strain have unique expression profiles, once they became intracellular bacteria (both BCG and M.tb) in macrophages, their protein expression were synchronized to the similar level.

FIGURE 8.

Differentiated protein expression with four groups were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA). PCA displaying the distinct biological variation among BCG, BCG in, M.tb, and M.tb in samples. Each point in the figure represents a repetition in a grouping experiment. Different colors and shapes distinguish different groups. All samples are within 95% confidence intervals (Hotelling T 2 ellipse).

Discussion

Previously, there are several works on the differentiated proteins between M.tb and BCG targeting novel mechanism underlying virulence and pathogenesis focusing on the whole proteins or only membrane proteins. However, all works used the bacteria in medium culture. In current study, we compared the proteomics of both intracellular M.tb and BCG from infected macrophages and the extracellular M.tb and BCG grown in 7H9 medium. Therefore, the differential proteins including membrane proteins and whole proteins in this study revealed data more relevant to virulence of M.tb.

Differential Proteins Common in Both Extracellular/Intracellular M.tb and BCG

Between M.tb in vs. M.tb out and BCG in vs. BCG out, there were 30 differential proteins up-regulated M.tb in vs. M.tb out, whereas 22 proteins in the group of BCG in vs. BCG out. However, only two proteins (Pks13 and Rv1405c) were commonly up-regulated, indicating both are essential for mycobacteria to enter THP-1 cells (Supplementary Table S3). Pks13 is required for mycolic acid biosynthesis; both M.tb and BCG need it to resist host immune cells (Wilson et al., 2013). Rv1405c is a methyltransferase that coordinates the adaptation of M.tb to the environment in vivo (Healy et al., 2016). On the other hand, there are both 41 differential proteins down-regulated in these two groups (M.tb in vs. M.tb out, BCG in vs. BCG out). Among them, 27 differential proteins were down-regulated commonly. Especially a series of oxidative phosphorylation pathway–related genes such as QcrA, QcrB, NuoL, NuoN, and CtaC that are closely related to energy metabolism were included. QcrA and QcrB are subunits of cytochrome-c complex, which is one of the transport electrons from the respiratory electron transport chain (Bahuguna et al., 2021). To establish an infection in the cells after invasion under the environment of phagosomes with low pH and oxygen and starvation, M.tb in and BCG in have to reduce their energy consumption and put themselves in a kind of dormant state.

The shared differential proteins between the group of BCG in vs. M.tb in and BCG out vs. M.tb out were further analyzed. There are 43 differential proteins up-regulated in group of BCG in vs. M.tb in, whereas there are 30 proteins up in group of BCG out vs. M.tb out. Among them, 20 proteins were commonly up-regulated. The phosphate-binding transporter lipoprotein PstS3 was a good immunogen inducing CD8(+) T-cell activation and both Th1 and Th17 immunity in mice (Palma et al., 2011). Hsp is up-regulated in the early stage of bacterial entry to cells and can help BCG stimulate the immune response of the hosts (Wilkinson et al., 2005). More interestingly, it seems that hsp is more important in BCG than M.tb, because it was only down-regulated after M.tb infection, but up-regulated in BCG in vs. BCG out, same as the two groups above. Thus, the results of the four groups were comprehensively analyzed, which provide partial explanation for M.tb survival better than BCG in host cells through immune evasion. In addition, Rv3699, Rv1762c, and Rv0825c are hypothetical proteins, which might be responsible for BCG immunogenicity and deserve to be further studied. On the other hand, there are 52 differential proteins down-regulated in group of BCG in vs. M.tb in, whereas there are 19 proteins down in group of BCG out vs. M.tb out. Among them, eight proteins were commonly down-regulated. A series of citrate cycle pathway–related genes, including Rv0247c and Rv0248c, are closely related to energy supply. In addition, some known virulence-related genes, such as RD region proteins and PPE family members, were not found in the shared differential proteins.

Taken together, among the differential proteins between BCG in/out and M.tb in/out, there are much more genes down-regulated than up-regulated for bacterial invasion of THP. Further, the down-regulation of genes is mainly enriched in pathways related to energy production. On the other hand, the commonly up-regulated genes are associated with induction of host immune response and bacterial intracellular survival.

Differential Proteins Only Between Intracellular M.tb and BCG

There are 211 differentially expressed proteins found in total between M.tb in and BCG in. In order to better understand the virulence mechanism of M.tb, the four groups of the differential proteins were analyzed comprehensively, we found 41 differential proteins uniquely up-regulated in the intracellular persistence of M.tb, which are supposed to be associated with M.tb virulence. First, eight RD proteins Rv0223c, EspK, Rv2073c, EsxA, EpiA (Rv1512), EsxO, LpqG, and Rv1513 were identified; among them, Rv1512, Rv1513, and Rv2073c need to be investigated in the future. There are seven other known virulence-related proteins including PPE41, PPE51, VapC10, VapB19, PhoB1, PhoH2, and Eccb1. PPE41 has been shown to induce macrophage necrosis (Tundup et al., 2014). PPE51 participates in the uptake of disaccharides and acid growth arrest by tubercle bacilli (Baker and Abramovitch, 2018; Korycka-Machala et al., 2020). PhoB1 controlled SenX3–RegX3 activity in response to phosphate availability and regulating phosphate transport by the Pst system; besides, it also affected M.tb tolerance to antitubercular drugs (Brokaw et al., 2017). VapC10, VapB19, and PhoH2 belong to toxin–antitoxin system proteins, which can promote M.tb persistence (Gerdes and Maisonneuve, 2012; Kedzierska and Hayes, 2016). VapC10 is toxin, whereas VapB19 and PhoH2 are antitoxin. In response to stress conditions, the labile antitoxin is degraded, and toxin is released, which in turn halts transcription, translation, and so on, and that leads to growth inhibition and even cell death (Sala et al., 2014). PhoH2 with additional RNA helicase activity acts on specific RNA substrates and plays a role in the adaptive response to changing environmental conditions (Andrews and Arcus, 2015; Andrews and Arcus, 2020). Eccb1 is one of the conserved components that contracted the core structure of the ESX-1 system (Houben et al., 2012). Other interested proteins with the expression difference above fourfold contained TB22.2 (Rv3036c) and gnd1. TB22.2 was characterized as a novel cell wall–anchored esterase from M.tb that can efficiently hydrolyze soluble p-nitrophenyl esters (Chen et al., 2014). Gnd1 encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase to engineering NADPH cofactor metabolism (Cheng et al., 2018). However, there are seven unknown function proteins including LppE, LpqD, Rv0795, Rv1532c, Rv2327, Rv3099c, and Rv1498A, which is worth to be investigated in the future.

For the differential proteins that are only up-regulated for the intracellular BCG, 23 proteins were identified, like Rv0315, FabG2, Rv1700, sigH, and Rv1523; they seem to be more related to immune response or fighting early stress in the host; only Rv1523 was related to virulence. Rv0315 is a novel dendritic cell maturation–inducing antigen that drives T-cell immune responses toward TH1 polarization and plays a crucial role in determining the nature of the immune response to TB (Korycka-Machala et al., 2020). Settles et al. found that FabG2-related vaccine candidates pgs1360 significantly reduced bacterial colonization in organs and induced an M. paratuberculosis–specific interferon γ production (Brokaw et al., 2017). Rv1700 and SigH play a key role in survival of bacteria against oxidative-stress (Raman et al., 2001; Patil et al., 2013). Methyltransferase Rv1523 induced virulence in mycobacteria (Ali et al., 2021).

In addition, there are six hypothetical proteins (Rv3046c, Rv0025, Rv1930c, Rv1262c, Rv0464c, and Rv0293c) and two less-information proteins (Rv0634c and Rv3842c) up-regulated in the group of intracellular BCG might be considered as candidate targets for vaccine research.

Differential Proteins Only in Extracellular M.tb and BCG

There are 10 proteins just significantly up-regulated in BCG compared with M.tb are also mainly related to immunity and can stimulate the host’s immune response. Like Rv0494, an FadR homolog in M.tb, directly binds to long-chain fatty acyl-CoA to inhibit fatty acid synthase II regulation (Biswas et al., 2013). Rv2466c is a key oxidoreductase that mediates the reductive activation of TP053, a thienopyrimidine derivative that kills replicating and nonreplicating M.tb (Albesa-Jové et al., 2015). PPE26 is a TLR2 agonist that stimulates innate immunity and adaptive immunity (Su et al., 2015). Rv2052c and Rv3747 are hypothetical proteins that may also have good immunogenicity.

For the differential proteins that are only up-regulated for the extracellular M.tb, 11 proteins were identified. Three proteins are involved in fatty acid metabolism, fadA6, FadE19, and FadD28. FadD28 plays a key role in the biosynthesis of a phthiocerol dimycocerosate lipid that occurs only in the cell wall of pathogenic mycobacteria (Goyal et al., 2006). All of these three proteins are involved in the fatty metabolism pathway and are essential for the utilization of fat by M.tb in vitro (Goyal et al., 2006; Kawaji et al., 2010; Cox et al., 2019). This suggests that M.tb makes better use of fat.

Although this study conducted in-depth data mining on four groups of differentially compared proteins and found some interesting proteins through analysis, there are also many works that deserve further studies. The proteins found in this research are based only on THP-1 cell, so the further test verifications could be considered to identify with other macrophages or in vivo. In addition, for some significantly differential proteins, specific verification and functional analysis need to be verified by a series of subsequent experiments. These will help to provide reliable data for the screening of potential TB antigen for development of vaccine.

In conclusion, more than 70% of the proteins in both M.tb and BCG were down-regulated after they infected macrophages enriched mainly in energy production. The numbers of differentially expressed proteins between M.tb and BCG were significantly greater after infection than before infection. Forty-two proteins were identified to be up-regulated only in intracellular M.tb including eight RD proteins, whereas 22 up-regulated uniquely in intracellular BCG. Besides, only two proteins (Pks13 and Rv1405c) were commonly up-regulated for intracellular M.tb and BCG. Further, 10 differential unknown proteins were uniquely up-regulated in the intracellular M.tb (10) and BCG (8). These findings provide valuable data for further exploration of molecular mechanism for M.tb virulence and BCG immune response.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to X. Chen and Z. G. Liang for use of the ABSL-3 facilities. Also, thanks for the help of Shanghai Lu-Ming Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

YC, HC, and AG conceived and designed the research; HL, TZ, YZ, and YP performed the experiments; HL, LS, KZ, and LW analyzed the data; HL, LS, YC, and AG contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No.2021YFD1800403), China Postdoctoral science foundation (Grant No. 2020M682447). National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U21A20259), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2021CFA016), and China Agricultural Research System (Grant No. CARS-37).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.847838/full#supplementary-material

References

- Albesa-Jové D., Comino N., Tersa M., Mohorko E., Urresti S., Dainese E., et al. (2015). The Redox State Regulates the Conformation of Rv2466c to Activate the Antitubercular Prodrug TP053. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (52), 31077–31089. 10.1074/jbc.m115.677039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Ehtram A., Arora N., Manjunath P., Roy D., Ehtesham N. Z., et al. (2021). The M. tuberculosis Rv1523 Methyltransferase Promotes Drug Resistance through Methylation-Mediated Cell Wall Remodeling and Modulates Macrophages Immune Responses. Front. Cel Infect. Microbiol. 11, 622487. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.622487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews E. S. V., Arcus V. L. (2015). The Mycobacterial PhoH2 Proteins Are Type II Toxin Antitoxins Coupled to RNA Helicase Domains. Tuberculosis 95 (4), 385–394. 10.1016/j.tube.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews E. S. V., Arcus V. L. (2020). PhoH2 Proteins Couple RNA Helicase and RNAse Activities. Protein Sci. 29 (4), 883–892. 10.1002/pro.3814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahuguna A., Rawat S., Rawat D. S. (2021). QcrB in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis : The New Drug Target of Antitubercular Agents. Med. Res. Rev. 41 (4), 2565–2581. 10.1002/med.21779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J. J., Abramovitch R. B. (2018). Genetic and Metabolic Regulation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Acid Growth Arrest. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 4168. 10.1038/s41598-018-22343-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A., Mathuria S., Athar F., Meena L. (2018). Structural and Functional Annotation of Rv1514c Gene of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis H 37 Rv as Glycosyl Transferases. J. Adv. Res. Biotech 3 (2), 1–9. 10.15226/2475-4714/3/2/00139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R. K., Dutta D., Tripathi A., Feng Y., Banerjee M., Singh B. N. (2013). Identification and Characterization of Rv0494: a Fatty Acid-Responsive Protein of the GntR/FadR Family from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Microbiology (Reading) 159 (Pt 5), 913–923. 10.1099/mic.0.066654-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw A. M., Eide B. J., Muradian M., Boster J. M., Tischler A. D. (2017). Mycobacterium Smegmatis PhoU Proteins Have Overlapping Functions in Phosphate Signaling and Are Essential. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2523. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch R., Pym A. S., Gordon S. V., Cole S. T. (2001). The Evolution of Mycobacterial Pathogenicity: Clues from Comparative Genomics. Trends Microbiol. 9 (9), 452–458. 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02131-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carranza C., Chavez-Galan L. (2019). Several Routes to the Same Destination: Inhibition of Phagosome-Lysosome Fusion by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Am. J. Med. Sci. 357 (3), 184–194. 10.1016/j.amjms.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Dang G., Deng X., Cao J., Yu S., Wu D., et al. (2014). Characterization of a Novel Exported Esterase Rv3036c from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Protein Expr. Purif. 104, 50–56. 10.1016/j.pep.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Wang S., Bilal M., Ge X., Zhang C., Fickers P., et al. (2018). Identification, Characterization of Two NADPH-dependent Erythrose Reductases in the Yeast Yarrowia Lipolytica and Improvement of Erythritol Productivity Using Metabolic Engineering. Microb. Cel Fact 17, 133. 10.1186/s12934-018-0982-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen K. A., Manson A. L., Abeel T., Desjardins C. A., Chapman S. B., Hoffner S., et al. (2019). Extensive Global Movement of Multidrug-Resistant M. tuberculosis Strains Revealed by Whole-Genome Analysis. Thorax 74 (9), 882–889. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. A. G., Taylor R. C., Brown A. K., Attoe S., Besra G. S., Fütterer K. (2019). Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis FadB2 Implicated in Mycobacterial β-oxidation. Acta Cryst. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 75 (Pt 1), 101–108. 10.1107/S2059798318017242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubaniewicz A. (2010). Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Heat Shock Proteins and Autoimmunity in Sarcoidosis. Autoimmun. Rev. 9 (6), 419–424. 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes K., Maisonneuve E. (2012). Bacterial Persistence and Toxin-Antitoxin Loci. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 6666, 103–123. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M. F., Saini N. K., Porcelli S. A. (2014). Evasion of Innate and Adaptive Immunity by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Microbiol. Spectr. 2 (5), 2–5. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0005-2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Yousuf M., Rajakumara E., Arora P., Gokhale R. S., Sankaranarayanan R. (2006). Crystallization and Preliminary X-ray Crystallographic Studies of the N-Terminal Domain of FadD28, a Fatty-Acyl AMP Ligase fromMycobacterium Tuberculosis. Acta Cryst. Sect. F 62 (Pt 4), 350–352. 10.1107/S1744309106005938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy C., Golby P., MacHugh D. E., Gordon S. V. (2016). The MarR Family Transcription Factor Rv1404 Coordinates Adaptation of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis to Acid Stress via Controlled Expression of Rv1405c, a Virulence-Associated Methyltransferase. Tuberculosis 97, 154–162. 10.1016/j.tube.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben E. N. G., Bestebroer J., Ummels R., Wilson L., Piersma S. R., Jiménez C. R., et al. (2012). Composition of the Type VII Secretion System Membrane Complex. Mol. Microbiol. 86 (2), 472–484. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaji S., Zhong L., Whittington R. J. (2010). Partial Proteome of Mycobacterium avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis under Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress. Vet. Microbiol. 145 (3-4), 252–264. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzierska B., Hayes F. (2016). Emerging Roles of Toxin-Antitoxin Modules in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Molecules 21 (6), 790. 10.3390/molecules21060790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korycka-Machala M., Pawelczyk J., Borowka P., Dziadek B., Brzostek A., Kawka M., et al. (2020). PPE51 Is Involved in the Uptake of Disaccharides by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Cells-Basel 9 (3), 603. 10.3390/cells9030603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Cui J., Niu W., Huang J., Feng T., Sun B., et al. (2019). Long Non-coding PCED1B-AS1 Regulates Macrophage Apoptosis and Autophagy by Sponging miR-155 in Active Tuberculosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 509 (3), 803–809. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. H., Liu H., Ge B. (2017). Innate Immunity in Tuberculosis: Host Defense vs Pathogen Evasion. Cell Mol. Immunol. 14 (12), 963–975. 10.1038/cmi.2017.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma C., Spallek R., Piccaro G., Pardini M., Jonas F., Oehlmann W., et al. (2011). The M. tuberculosis Phosphate-Binding Lipoproteins PstS1 and PstS3 Induce Th1 and Th17 Responses that Are Not Associated with protection against M. tuberculosis Infection. Clin. Develop. Immunol. 2011, 690328. 10.1155/2011/690328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A. G. G., Sang P. B., Govindan A., Varshney U. (2013). Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MutT1 (Rv2985) and ADPRase (Rv1700) Proteins Constitute a Two-Stage Mechanism of 8-Oxo-dGTP and 8-Oxo-GTP Detoxification and Adenosine to Cytidine Mutation Avoidance. J. Biol. Chem. 288 (16), 11252–11262. 10.1074/jbc.M112.442566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipa B., Mvn B., Mpra B., Mvsa B., Kd A., Iaoa B., et al. (2019). Oligoglutamylation of E.Coli Ribosomal Protein S6 Is under Growth Phase Control. Biochimie 167 (C), 61–67. 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman S., Song T., Puyang X., Bardarov S., Jacobs W. R., Husson R. N. (2001). The Alternative Sigma Factor SigH Regulates Major Components of Oxidative and Heat Stress Responses in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . J. Bacteriol. 183 (20), 6119–6125. 10.1128/Jb.183.20.6119-6125.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala A., Bordes P., Genevaux P. (2014). Multiple Toxin-Antitoxin Systems in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis . Toxins 6 (3), 1002–1020. 10.3390/toxins6031002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H., Kong C., Zhu L., Huang Q., Luo L., Wang H., et al. (2015). PPE26 Induces TLR2-dependent Activation of Macrophages and Drives Th1-type T-Cell Immunity by Triggering the Cross-Talk of Multiple Pathways Involved in the Host Response. Oncotarget 6 (36), 38517–38537. 10.18632/oncotarget.5956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanghe A., Lefèvre P., Denis O., D'Souza S., Braibant M., Lozes E., et al. (1999). Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of Tuberculosis DNA Vaccines Encoding Putative Phosphate Transport Receptors. J. Immunol. 162 (2), 1113–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Bryk R., Itoh M., Suematsu M., Nathan C. (2005). Variant Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Identification of -ketoglutarate Decarboxylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102 (30), 10670–10675. 10.1073/pnas.0501605102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi O. A., Arora P., Vats A., Ansari M. Z., Tickoo R., Sridharan V., et al. (2005). Dissecting the Mechanism and Assembly of a Complex Virulence Mycobacterial Lipid. Mol. Cel 17 (5), 631–643. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tundup S., Mohareer K., Hasnain S. E. (2014). Mycobacterium tuberculosisPE25/PPE41 Protein Complex Induces Necrosis in Macrophages: Role in Virulence and Disease Reactivation? FEBS Open Bio 4, 822–828. 10.1016/j.fob.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale M. N., Colombatti Olivieri M. A., Alonso N., Moyano R. D., Imperiale B., Morcillo N., et al. (2021). Effect of the Deletion of lprG and P55 Genes in the K10 Strain of Mycobacterium avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis. Res. Vet. Sci. 138, 1–10. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wu J., Li J., Yang H., Tang T., Liang H., et al. (2020). Host-mediated Ubiquitination of a Mycobacterial Protein Suppresses Immunity. Nature 577 (7792), 682–688. 10.1038/s41586-019-1915-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G., Schaible U. E. (2015). Macrophage Defense Mechanisms against Intracellular Bacteria. Immunol. Rev. 264 (1), 182–203. 10.1111/imr.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson K. A., Stewart G. R., Newton S. M., Vordermeier H. M., Wain J. R., Murphy H. N., et al. (2005). Infection Biology of a Novel α-Crystallin ofMycobacterium Tuberculosis: Acr2. J. Immunol. 174 (7), 4237–4243. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R., Kumar P., Parashar V., Vilchèze C., Veyron-Churlet R., Freundlich J. S., et al. (2013). Antituberculosis Thiophenes Define a Requirement for Pks13 in Mycolic Acid Biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9 (8), 499–506. 10.1038/nchembio.1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Wang R., Deng D., Chen Y., Liu H., Wang T., et al. (2017). Comparative Genomics of a Bovine Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Isolate and Other Strains Reveals its Potential Mechanism of Bovine Adaptation. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2500. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Wang Z., Zhang W., Zhang L. (2019). MicroRNAs Play an Essential Role in Autophagy Regulation in Various Disease Phenotypes. Biofactors 45, 844–856. 10.1002/biof.1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Dockrell H. M., Ottenhoff T. H. M., Evans T. G., Zhang Y. (2018). Tuberculosis Vaccines: Opportunities and Challenges. Respirology 23 (4), 359–368. 10.1111/resp.13245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.