Abstract

Introduction

Older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) often are inadequately prepared to make informed decisions about treatments including dialysis and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Further, evidence shows that patients with advanced CKD do not commonly engage in advance care planning (ACP), may suffer from poor quality of life, and may be exposed to end-of-life care that is not concordant with their goals. We aim to study the effectiveness of a video intervention on ACP, treatment preferences and other patient-reported outcomes.

Methods and analysis

The Video Images about Decisions for Ethical Outcomes in Kidney Disease trial is a multi-centre randomised controlled trial that will test the effectiveness of an intervention that includes a CKD-related video decision aid followed by recording personal video declarations about goals of care and treatment preferences in older adults with advancing CKD. We aim to enrol 600 patients over 5 years at 10 sites.

Ethics and dissemination

Regulatory and ethical aspects of this trial include a single Institutional Review Board mechanism for approval, data use agreements among sites, and a Data Safety and Monitoring Board. We intend to disseminate findings at national meetings and publish our results.

Trial registration number

Keywords: nephrology, chronic renal failure, end stage renal failure, dialysis, geriatric medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of a human-assisted Natural Language Processing (NLP) tool that can quickly and comprehensively evaluate a large corpus of clinical notes.

A broad selection of study sites leading to diversity and geographic spread of the subject population.

Findings may be of limited generalisability, for example, the study findings may not extend to older adults with chronic kidney disease who also have cognitive impairment or patients who are receiving dialysis treatments.

Only advance care planning (primary outcome) that is documented in the chart is assessable by the NLP methodology.

‘Dosage’ of the video decision aid intervention will not be tracked and thus the study will not assess how often patients watch which portions of the video intervention and how much in total was viewed.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is an iterative process that involves conversations about patients’ goals and preferences for future medical care.1 The core value of ACP lies in conversations exploring what matters most to patients and in preparation of patients and families for future ‘in-the-moment’ shared decision making.2 Conversations between clinicians and their patients about their goals and values in serious illness are associated with outcomes such as improved patient and family satisfaction about the quality of death, end-of-life care, as well as less anxiety and depression.3–7 In addition, failing to address patients’ goals and values through ACP conversations is associated with more hospital use at the end of life, more burdensome interventions, less use of hospice and more difficult bereavement for families and caregivers.8–13

ACP conversations frequently do not happen for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).14–16 Advanced CKD carries notable morbidity and mortality for patients and is marked by frequent interaction with the healthcare system.17–20 Older adults bear a significant burden of CKD and have high rates of mortality from comorbid illnesses and after starting dialysis.21–25A growing body of literature suggests that some older adults with CKD and other comorbidities who progress to kidney failure may receive few benefits from dialysis and may experience a degradation in quality of life and functional status.26–28 In addition, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) appears to be particularly ineffective in older adults with advanced CKD and overall knowledge about CPR remains low in this population.14 29 As such, experts and guidelines have called for increased efforts to improve on shared advance care planning and decision-making for older adults around initiation of dialysis and CPR preferences.30–32 Further, medical treatments, such as dialysis, are often presented as necessary rather than a matter of personal preference while the option of medical management of kidney disease without dialysis is poorly described to patients, if at all.33–38 As a result, there is a call for research to develop and test tools to improve ACP and treatment decision-making among older adults with advanced CKD.33

Traditional ACP and decision-making for patients rely on clinicians’ ad hoc verbal or paper-based descriptions of treatment options as patients consider what preferences meet their unique goals.34 39–41 This approach is limited because treatment decisions, such as those for dialysis, and medical management without dialysis options, and CPR are challenging to describe or may not be accessible to patients with limited literacy. Additionally, information provided to patients is variable and both verbal and paper explanations are hindered by literacy and language barriers. Patients often look to video media for information on CPR,42 however, fictional video representations in popular media can sensationalise and misrepresent outcomes.14 43–46 To address these shortcomings, we developed and tested a video decision aid to improve knowledge of kidney failure treatment options (including medical management without dialysis) among older patients with advanced CKD.38 The tool, which is available in both English and Spanish, significantly improved knowledge of medical management without dialysis and participants also reported high satisfaction and acceptability ratings.38 Video-based tools can improve decision making by providing visual information to capture complex medical and emotional scenarios and lead to increased ACP documentation.47 48 Additionally, a growing body of evidence supports the effectiveness and feasibility of decision aids on decision-making outcomes among patients with various serious illnesses, including in kidney disease.38 43 44 47–59 In this paper, we present the rationale, methodology and design of the Video Images about Decisions for Ethical Outcomes in Kidney Disease (VIDEO-KD) trial.

Methods

Overview

The VIDEO-KD trial is a planned 5 years (1 April 2020–31 March 2025), multi-centre randomised controlled trial that will test the effectiveness of a two-part video intervention on the primary outcome of ACP documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) among patients aged 65 and older with advanced CKD. The first part of the intervention consists of a video aid to facilitate informed decision-making for patients with kidney disease.38 In the second stage of this intervention, patients can record their ACP preferences (called ‘video declarations’ or ‘ViDecs’) to share with their clinicians and caregivers.60 The specific aims for this study are as follows:

Aim 1: To compare ACP documentation after 1 year (or at the time of death) among English and Spanish speaking patients aged 65 or over with advanced CKD and poor prognosis randomly assigned to either: (1) an ACP video visually depicting CKD treatment options with a patient’s personalised video declaration (intervention); or (2) usual care (control).

Aim 2: To compare knowledge, decisional conflict, ACP engagement, CKD treatment preferences for CPR and dialysis, self-reported ACP conversations with clinicians and caregivers, and concordance of preferences with medical care delivery after 1 year (or at time of death) between intervention and control subjects.

Aim 3: To explore the quality of life, longevity and cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) associated with patients’ CKD treatment decisions in the intervention versus control groups.

Aim 4 (Exploratory): To conduct qualitative assessment of personal video declarations from 300 patients.

We will use Natural Language Processing (NLP) of the EHR to abstract our primary outcome for 600 patients. We will also assess the effect of the video intervention on secondary outcomes including decision-making experiences, treatment practices, and quality of life compared with participants who undergo usual care. Demonstrating the effectiveness of a video intervention in persons who are facing decisions regarding treatment for kidney failure represents an essential step to implementing these tools into standard clinical practice. We used the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials reporting guidelines in preparing this manuscript.45

Patient and public involvement

Patients were involved in the design and validation of the video aids being studied in this research.

Study timeline

The first year will involve design of data collection processes, study-site staff training and standardisation activities around video delivery and patient enrolment processes. This will be followed by 42 months of recruitment and survey administration. Enrolled patients will be followed from initiation of trial procedures until death or the end of study, whichever comes first. Participants will be contacted every 2 months up until 1 year via follow-up phone calls to complete study surveys.

Sites and randomisation

We will draw participants from ten healthcare systems across several regions in the USA. These include organisations that represent the Mid-Atlantic (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania), Northeast (Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Renal Transplant Associates of New England), Southwest (University of New Mexico), West (Stanford University, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System), Northwest (University of Washington) and Midwest (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) regions. These systems represent a geographically diverse sample of patients and feature researchers and clinicians with expertise in the care of older patients with advanced CKD.38 61–67 Combined, these centres have over 80 000 outpatient nephrology visits annually.

VIDEO-KD will employ central, computer-generated block randomisation at each site with varying block sizes of 4 and 6, starting at a random point within the first block to blind staff from randomisation patterns and to protect against the influence of secular trends over the trial period by ensuring balance between study arms. Randomisation will be stratified by site and language, English versus Spanish, to ensure even distribution across study arms.

Population

We aim to recruit a total of 600 patients over the study period. Study participants will be selected from ambulatory nephrology practices at each site. The inclusion criteria are: (1) 65 years or older in age; and (2a) advanced CKD and/or (2b) poor prognosis. Advanced CKD will be defined by at least two measurements for eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 separated by at least 90 days. Poor prognosis will be defined as less than a 1 year prognosis as determined by the treating nephrologists answering ‘No’ to the Surprise Question (‘Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?’). A ‘No’ answer to the Surprise Question has been demonstrated to be an accurate predictor of 1 year mortality in older patients with advanced CKD not on dialysis and patients with multiple comorbidities.63 68–70 Subjects aged 65–69 will require both advanced CKD and a poor prognosis while those aged 70 and older will require either advanced CKD or a poor prognosis. The exclusion criteria for the VIDEO-KD study include: (1) patients who are listed for kidney transplantation or those who have received a kidney transplant prior to study enrolment; (2) patients who have previously received or are receiving dialysis; (3) patients who are new to the clinic (ie, on their initial visit); (4) people who are visually impaired beyond 20/200 corrected; (5) patients who have been deemed by their nephrologists to have a psychological state that is not appropriate for study participation; and (6) cognitive impairment evaluated by administering the validated Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire71 where patients with two or more errors will be excluded from the study.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria aim to capture a broad population of older adults with advanced CKD for whom ACP and decisions about kidney failure therapy are relevant. We used similar enrolment criteria in a pilot study to assess the efficacy of the video decision aid.38 We aim to evaluate only patients returning to clinic with an established relationship with the nephrology clinic due to the sensitive nature of ACP conversations. We anticipate patients will be racially/ethnically, socioeconomically and culturally diverse.

Recruitment

Potential participants with advanced CKD will be identified by their EHR. The research assistant (RA) will review a list of scheduled patients 2 weeks prior to their clinic visit. Only established patients known to the nephrologist will be considered. Using the EHR, the RA will identify potential participants who meet our eligibility criteria. To conduct this screening procedure, a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) waiver of individual authorisation for disclosure of personal health information will be obtained. For those patients meeting the criteria, their nephrologist will then be notified by email to solicit their opinion as to whether the patient is otherwise appropriate to approach for participation based on the nephrologist’s knowledge of the patient’s clinical status, psychological disposition and decision-making capacity. They will also be asked to review their panel of patients for any patients meeting the Surprise Question criterion but not selected by the RA. When an appropriate patient is identified, they will either be mailed an opt-out recruitment letter and then called by phone for recruitment, or, if they are seen in the clinic in person, they will be asked by a member of their care team if they would like to speak with an RA to hear about the study. If the patient is amenable, the RA will administer the cognitive screening and schedule a time to administer the informed consent. The RA will then obtain informed consent (online supplemental file 1), which will be documented in accordance with each site’s requirements for each mode (phone, video or in-person). The RA will verify the ability of the patient to provide consent by explaining the nature of the study and having the patient repeat (teach-back) the aims and risks of the study. Only those patients who can understand the aims of the project, what their involvement entails and the risks and benefits of participation will be eligible. Family members and friends who might be present with the patient will be invited to remain during the survey if that is agreeable to the patient; however, all answers will be provided by the patient. After completing informed consent, the randomisation assignment is automated within the REDCap system, telling the RA in real time if the patient has been randomised to the intervention or control arm.72 An analyst with the central research team created the randomisation scheme and uploaded it into REDCap so study staff can access it directly as part of patient enrolment. We have successfully used similar procedures to the above in our prior National Institutes of Health-funded trials.50 73

bmjopen-2021-059313supp001.pdf (667.3KB, pdf)

Intervention design, implementation and adherence monitoring

The first element of the video intervention is the video decision aid, which reviews kidney failure therapies (10 min) and CPR (2 min). The 12 min video decision aid is designed for older patients with kidney failure making decisions about medical treatments.38 The development of the video followed a systematic approach, using an iterative process of design, content and structure reviews by geriatricians, nephrologists, palliative care clinicians, patients with kidney disease and their caregivers. The decision aid was designed using the internationally recognised decision aid criteria (International Patient Decision Aid Standards, http://ipdas.ohri.ca/). The proposed video decision aid for this study was certified by the Washington Health Care Authority and is the only decision aid currently certified in kidney disease (https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/healthier-washington/patient-decision-aids-pdas). Additionally, the video was developed with content intended to be objective and balanced. It is scripted at a sixth-grade level of health literacy in both English and Spanish and has closed captioning. The Spanish script was also back-translated into English and reviewed by multiple stakeholders to ensure cultural appropriateness and accuracy. All investigational team members have reviewed and approved the video for use at their specific site.

The video decision aid is designed for older people with advanced CKD and their family members who are making decisions regarding three kidney failure treatment options: haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or medical management without dialysis. The aid also reviews CPR. The goal of this tool is to use decision science to support the person’s ability to make patient-centred informed decisions by considering: (1) accurate information about each option; (2) the risks and benefits of each alternative; (3) each choice within the context of their values and lifestyles; (4) a decision based on trade-offs among options; and (5) means for engaging with clinicians to discuss and document values, lifestyle and prognoses.

The video begins with a physician introducing the viewer to the concept of ACP as well as a review of advanced CKD and kidney failure. The narrator explores each of the options for kidney failure, reviewing the risks and benefits of each, and then discussing the trade-offs among the three options. For each option, visual images illustrate the therapy while discussing risks and benefits. The visual images illustrating the first option, haemodialysis, include a patient receiving in-centre haemodialysis, nurses attending to the person on haemodialysis, and images of caregivers. The second option, peritoneal dialysis, includes visual images of a person at home on peritoneal dialysis with the assistance of caregivers, and the daily activities around peritoneal dialysis equipment care. The third option, medical management without dialysis, is introduced by the narrator as a potential option for those persons who wish to not pursue dialysis or any of its associated burdens and who would prefer to focus on their quality of life. The narrator explains that medical management without dialysis focuses on clinicians, patients and caregivers working together to treat symptoms through medical management, and other core principles of palliative care.

The narrator then begins to describe CPR and the option of whether to receive CPR or not. The images include CPR on a mannequin and the likelihood of success for older patients with CKD. Visual images include physicians, nurses, patients and caregivers in clinic, at home, and in the hospital. The video was created using filming criteria formulated by this research team.46 The video was filmed without the use of prompts or stage directions (ie, no actors) to convey a candid realism in the style known as cinema verité.74

In order to watch the video beyond the initial exposure during the survey (for the intervention arm), participants will be given a code without expiration for home use as well as to share with their caregivers; the code can be used as many times as they wish. The research team will track use of the video (ie, number of times the patient accessed the video decision aid from home using their code).

After viewing the video decision aid, the RA will assist the participant in recording a ViDec of their ACP preferences. First, the RA invites the patient to introduce her/himself; afterwards, the RA will ask a series of open-ended questions intended to draw responses to a range of topics both important for a full discussion of ACP preferences and raised in our previous qualitative research.60 The questions and this process was developed by a core group of study team members (NE, MP-O, AV, LMQ) with expertise in health literacy, nephrology, health equity, qualitative methods, video documentary and ACP for language appropriateness and breadth of content. These topics include: awareness of the kidney disease, goals and values, kidney failure treatment preferences (ie, medical management without dialysis, peritoneal dialysis, haemodialysis), emergent medical treatments (ie, CPR, intubation), faith/spirituality and any other topics the patient would like to discuss. After recording, the RA asks the patient questions about the helpfulness and ease of making the ViDec and will share the ViDec with the patient and the patient’s nephrologist, primary care physician and any other provider that the patient requests. Clinicians will be encouraged at this time to document preferences and goals in the medical record. The video will be shared through HIPAA compliant methods (such as secure online platforms or encrypted flashdrive) approved by the IRB and privacy officer at the site where the patient was enrolled. The patient will be encouraged to share their video with family and loved ones.

To assist participants in creating a ViDec, the RA will provide a brief introduction to patients by explaining that the video is to help doctors and family understand their wishes (online supplemental file 2). The RA will use conferencing software (eg, if visit is remote) or an iPad (if visit is in person) to ask the patient questions and record the patient’s answers. If the patient declines to be video-recorded, the RA will offer an audio-only option. When the recording is complete, the RA will offer to play the video for the patient to see if they feel it accurately represents their choices and if not, if they would like to re-record their video. Patients will be able to re-record their ViDecs with each study check-in (every 2 months) or at an earlier time if they wish. We expect patients will wish to discuss their preferences with family and that their preferences may change over time. As new ViDecs replace prior videos they will again be shared with the patient and with the patient’s clinicians, with the patient’s permission.

bmjopen-2021-059313supp002.pdf (45.7KB, pdf)

To ensure appropriate delivery of the intervention, the co-principal investigators and site coinvestigators will lead weekly supervision meetings with RAs to discuss any issues regarding implementation of the video decision aid and ViDecs. Also, all video decision aid showings will be tracked with a date, time stamp and playthrough rate to ensure complete showing of the video decision aid to patients randomised to the intervention. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, study activities will be available both in-person and remotely.

Control condition

Patients assigned to the control arm will receive the typical current ACP practices that already exist in each of their local respective sites. These will vary by site and can include activities such as distribution of educational materials reviewing dialysis, medical management of kidney failure, CPR, educational classes or instructional sessions regarding dialysis options, and ongoing site activities around engagement with ACP. Notably, especially considering the COVID-19 pandemic, ACP-improvement initiatives may be active and different across sites over the course of the trial, this heterogeneity reflects the current dynamic state of ‘usual’ care.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the VIDEO-KD trial is the presence of ACP documentation in the EHR within 1 year of follow-up after study enrolment or death, whichever comes sooner. Secondary outcomes include: engagement with ACP, preferences stated in ACP conversations, self-reported ACP conversations, both kidney disease specific and health related quality of life, decisional conflict, acceptability of video intervention, CKD care preferences outlined in discussions (haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or medical management without dialysis) and healthcare costs, assessed per QALY associated with patients’ kidney failure and CPR treatment decisions.

Additional exploratory outcomes will include: (1) thematic analysis of the ViDec content; (2) analysis of ViDec change over time (for participants who record multiple ViDec recordings over the course of their participation); (3) assessment of ACP preferences as communicated in the ViDec recordings; (4) comparison of ACP preferences as communicated in the ViDec recordings to the contemporaneously reported ACP preferences documented in the medical record and in research surveys; and (5) description of the usefulness, understandability and relevance of the video intervention package.

Data sources, data elements and linkage

Table 1 shows study data elements and sources and time points of data collection.

Table 1.

Data elements and sources for key trial outcomes by study procedure

| Data collected | Purpose | Tool/source | By whom | When |

| Prognosis | Target subpopulation identification, covariate | eGFR, SQ/EHR | RA, PN | 2 weeks prior to visit |

| Cognitive assessment | Screening | SPMSQ | RA | Prescreening |

| Sociodemographics | Covariate | Study survey | RA | Baseline |

| ACP documentation | 1o outcome | EHR | RA | 1 year or at death |

| ACP engagement | 2o outcome | ACPE | RA | Baseline |

| ACP preferences | 2o outcome | Study survey | RA | Baseline, every 2 months |

| ACP conversations | 2o outcome | Study survey | RA | Every 2 months |

| Kidney disease specific quality of life | 2o outcome | KD-QoL | RA | Baseline, every 2 months |

| Health related quality of life | 2o outcome | EuroQol | RA | Baseline, every 2 months |

| Decisional conflict | 2o outcome | DCS | RA | Baseline |

| Acceptability of video intervention | 2o outcome | YDDAU | RA | Baseline |

| CKD care preferences | 2o outcome | EHR | RA | 1 year or at death |

| Healthcare costs | 2o outcome | Medicare claims data | RA | Expected year 4 and 5 |

ACPE, Advance Care Planning Engagement Questionnaire; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; DCS, Decisional Conflict Scale; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EHR, Electronic Health Record; EuroQol, 5-level EuroQol-5D version (EQ-5Dimension-5Level); KD-QoL-36, Kidney Disease Quality of Life; PN, primary nephrologist; RA, research assistant; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; SQ, Surprise Question; YDDAU, Yorkshire Dialysis Decision Aid Usefulness Scale.

Sociodemographics

Data on sociodemographics including age, gender, race, ethnicity, primary language, health insurance, education, marital status, religion and religious attendance will be assessed via surveys.

ACP documentation

Will include any documentation in the EHR reflecting an ACP conversation (completion of advance directive or Physician’s Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST); code status documentation; provider note reflecting ACP discussion) (primary outcome). The primary analysis will be based on the EHR notes of the nephrology clinic team. In the secondary analysis, we will also add notes from other providers.

ACP engagement

We will ask, via RA administered survey, four validated questions regarding ACP engagement.75 (How ready are you to talk to your caregiver? To your doctor? To appoint a surrogate? To sign an ACP document?)

ACP preferences

Resuscitation preferences regarding CPR (yes, no or unsure) and dialytic versus non-dialytic treatment (haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, medical management without dialysis or unsure) will be assessed after randomisation, and every 2 months until the end of study follow-up at 12 months or death.

ACP conversations

We will survey patients regarding whether they have had prior ACP discussions.

Kidney disease specific quality of life

We will also measure disease-specific quality of life using data obtained from the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-36)76 administered at baseline and every 60 days thereafter. Responses to each of the 36 items will be scored (0–100) and the overall mean used as the quality of life measure for each survey round.

Health related quality of life

To capture differences in quality of life, besides longevity, associated with the choice of kidney care approach, we will use EuroQol’s EQ-5D-5L instrument as the quality measure.77 This instrument takes responses to five questions on mobility, self-care, ability to perform usual activities, pain and anxiety/depression to produce a validated quality score (0–1). This instrument will be administered at baseline and every 60 days thereafter. The cumulative quality scores from consecutive rounds of survey will be used to obtain the QALYs for the exposure time.

Decisional conflict

We will measure decisional conflict using the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS), which attempts to measure decisional uncertainty.78

Acceptability of video intervention

For those patients randomised to the video intervention, we will measure, via survey, acceptability of the decision aid using a modified version of the validated Yorkshire Dialysis Decision Aid Usefulness Scale.79 We will also ask questions regarding comfort viewing the video, which we have validated in our prior work.38 47 48 50 52 54–56 80

CKD care preferences

All patients will be asked their preferences for kidney failure care at baseline. We will then assess their follow-up preferences by chart review in the electronic medical record.

Healthcare costs

The main source of differences in costs between the video and control arms will be from the stream of healthcare services used, including that for kidney failure care, over the exposure time. Based on prior evidence of healthcare spending of CKD patients, we will identify the major components of services used, including inpatient, pharmacy, outpatient, emergency department and dialysis.21 81 We will also examine utilisation by subgroups with comorbidity of diabetes, heart failure and cardiovascular disease. We will use Medicare claims data to obtain the associated costs, including payments by Medicare and secondary payers (eg, out-of-pocket payments).82 Medicare claims data are available for a majority of Medicare enrollees (about 75% choose the Fee for Service plan). As these data are unavailable for the others who choose managed care plans or are enrolled from the Veterans Affairs, we will impute the costs (per year) based on the average costs for the Fee for Service participants separately by the type of kidney care chosen.81

Natural Language Processing

We will conduct NLP-assisted EHR review for documentation of ACP (primary outcome). This EHR review will include keyword-based searches for documentation of limitations to life-sustaining treatment, goals of care, healthcare proxy designation or communication on the patients’ behalf, palliative care involvement, hospice preference or utilisation, discussions surrounding dialytic versus non-dialytic therapies (including time-limited trials of dialysis), as well as completion of any advance directive and/or POLST. For patients who die prior to 12 months, we will conduct an NLP-assisted EHR review to assess ACP documentation (primary outcome), type of kidney failure treatment received prior to death, receipt of palliative care, hospice, or CPR/intubation in the last month of life, and place of death (eg, intensive care unit, home, etc).

NLP-assisted EHR review will rely on the ClinicalRegex software, which allows for rapid semi-automated clinical note review. ClinicalRegex presents operators with clinical notes highlighted in particular areas located by keywords associated with the concepts in question. Site operators will then ensure that keywords found within the notes appear in the correct clinical context (as in the documentation of ACP conversations). This method will be used at each site to search all collected outpatient clinical documentation data from the EHR for ACP documentation, similar to prior studies using NLP.83–85

For each NLP domain (ie, goals-of-care discussion, limitations to life-sustaining treatment), we have built a keyword library with the goal of identifying relevant documentation within clinical notes. Each keyword library will be refined and validated by the review of retrospective clinical notes in each site’s local EHRs to generate formal metrics (accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, etc) across all sites.86

All site operators who will be engaged in this NLP must participate in training on note annotation practices and must demonstrate proficiency in annotating notes containing clinical concepts expected to be found during this trial. Proficiency will be determined by the use of a calibration test consisting of 20 mock clinical narratives which will be used to cross-validate annotation practices across all sites.

The EHR data will be reviewed by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) data staff and unblinded investigators. The NLP results and metadata (keyword frequencies, rates of agreement between annotator and keyword library) for each domain will be used across all sites to identify out of range or unexpected results, and a summary will be sent to each site. Conference calls will be conducted with relevant investigators and programmers to adjudicate any issues. We will then finalise NLP analysis results and submit to the study statistician for further analysis.

We have data use agreements from all sites to ensure adherence to the process and procedures for the protection of human subjects and protected health information (PHI). We will collect the minimum PHI needed from study participants and store all study information on HIPAA-compliant, password secured servers. We will separate participant identifying information from password-secured files while maintaining a linkage file at study sites. The linkage file will be restricted per local rules for PHI. We will transfer study data through HIPAA-secure methods specific to each site. Data will be sent to DFCI for data management and to Boston Medical Center and Massachusetts General Hospital for analysis. The final data set will be available to trial investigators on completion of the study and others can be provided access on reasonable request.

Masking

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants and study staff will not be blinded to the intervention. The NLP outcomes adjudication used in this study is a human-assisted NLP in which a staff member validates the text presented in the software as a possible outcome. For analysis, the following steps will be taken to ensure blinding to study arm assignment by the staff member doing the NLP outcome attribution:

Prior to adjudication activities, names will be anonymised.

Annotation will be performed in large batches with all enrolled patients who have clinical notes to that point.

NLP notes for adjudication will not be grouped by study ID when presented to annotators. Each note will be annotated individually, without reference to concepts contained in other notes.

When possible, a staff member who did not enrol the participants will perform the annotation.

Statistical analysis

Our primary analyses will use an intention-to-treat approach including all randomised patients in the analysis regardless of whether patients receive the intended intervention. Secondary analysis will be used to address any non-compliance issues (eg, patients in the control group review publicly accessible videos or patients in the intervention group choose not to watch study videos). For all outcomes, we will include known predictors of outcomes in the regression models to increase the precision of the effect estimates. We will also evaluate the possibility of secular trends through including information such as year of study enrolment in the models. We will examine the heterogeneity of treatment effect by testing the interaction between intervention and prespecified subgroups (LatinX and non-LatinX, whites and non-whites, English speaking vs non-English speaking) to determine whether the intervention effect differs among subgroups. We will conduct subgroup analysis if there is evidence of an interaction between subgroup and study arm. For outcomes assessed every 2 months (eg, treatment preferences, ACP conversations), we will use a repeated measures analysis to include data from all available time points (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 months) to (1) compare the trend over time and (2) compare outcomes at each time point using the Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) approach.

ACP documentation

Our primary outcome is clinician ACP documentation within 1 year. We will use a Poisson model to compare the rate of patients with ACP documentation with the length of follow-up treated as an offset. Patients lost to follow-up or patients who died within 1 year will be considered as ‘censored’ in this approach.

ACP engagement

ACP engagement will be summarised using the 4-item survey tool.75 We will use a repeated measures analysis with GEE to compare the level of engagement at each time point and the trend over time.

ACP preferences

We will use χ2 tests to compare the proportion of participants choosing ‘No CPR’ and ‘medical management without dialysis’ at any point during the study between the two arms. For the analysis of CPR, patients who choose ‘Unsure’ will be considered ‘Yes CPR’ since in clinical practice patients who are unsure receive the clinical default of ‘Yes CPR’.47–49 The repeated measures analysis will be used to summarise the stability of treatment preferences over time. Treatment preference concordance will be treated as a dichotomised variable aligning what patients say or (after the intervention for patients randomised to this arm) with CKD care received after 1 year (or at time of death) and compared using a χ2 test. For people who are deceased, we will use NLP to extract data from the EHR for the last 3 months of life for all deceased patients regarding CKD care received.

ACP conversations

The number of patient self-reported ACP conversations will be compared using a Poisson regression model with repeated measures analysis.

Quality of life and costs

Due to differential preference for medical management without dialysis, we expect patients randomised to the video arm to have different health outcomes (longevity and quality of life) and healthcare utilisation relative to the control group. We will first estimate the impact of the video on longevity, quality of life and healthcare utilisation separately. Depending on these results, we will use cost-effectiveness analysis to compare the value of the services used between the two groups.87 For our primary analysis we will use the perspective of the healthcare payer (Medicare). Using generalised Poisson regression models, we will separately estimate the average difference in quality of life and costs associated with the video arm relative to the control arm, expressed per 1 year of exposure time. Using generalised linear and survival models we will also examine longevity both as a dichotomous survival indicator (0/1) and as a continuous measure. We will adjust for systematic differences across hospitals using either a random or fixed effects specification.88 We will use increment net benefit (INB) as the cost-effectiveness measure.89 INB is defined as the difference between change in quality of life evaluated at monetary valuation of 1 QALY (currently $100 000) and change in costs. Positive INB indicates net improvement in quality of life, while a negative INB denotes a worsening of quality of life. In the case of improvement in quality of life and lower healthcare utilisation from the video intervention, INB captures gains from both the improvements. We will obtain 95% CI of the INB estimates based on bootstrapping estimation.90

Decisional conflict

Decision conflict scale78 is a continuous variable ranging from 3 to 15 and will be compared using a two-sample t-test.

Statistical power and sample size requirements

ACP outcomes

Our prior studies showed that 81% of video participants had ACP documentation compared with 46% in controls.47 With 300 patients per group, the study will have >90% power to detect such a difference with a two-sided 0.05 significance level. For CKD preferences, the study will have 90% power to detect a difference of 46% of video participants choose medical management without dialysis vs 33% in the control arm estimated from our pilot study. Assuming 60% of video participants achieve preference concordance, the study will have 96% power to detect a 15% difference (60% vs 45%) and 84% power to detect a 12% difference (60% vs 48%). For continuous outcomes such as ACP engagement, the study will have 90% power to detect an effect size of 0.265% and 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.229. Both are considered as small to medium effect sizes.

Quality of life

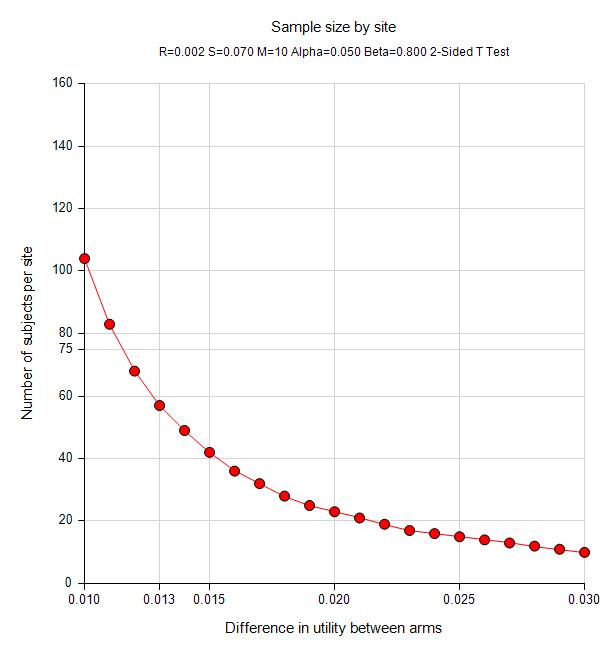

Figure 1 gives the sample sizes needed to distinguish utility differences of 0.01–0.03 between intervention and control participants with 80% power (alpha=0.05 and intracluster correlation=0.02).82 89 91 For instance, with 10 institutions (total 10 clinics), 60 participants from each institution (N=600)—with half assigned to each arm—will be adequate to distinguish 0.013 difference in utility between the two arms. A difference of 0.013 amounts to a 2.3% difference in utility based on the estimate of 0.56 utility level for patients on haemodialysis (using the EuroQol-5D instrument). If a 20% combined loss to follow-up and study withdrawal is included, the sample enrolled would be 588 participants.

Figure 1.

Sample sizes needed to distinguish utility differences for quality of life.

Qualitative analyses

Qualitative analyses will begin by transcribing ViDecs verbatim, adding non-verbal cues such as emotional expressions. We will create a preliminary codebook based on a prior ViDec project60 and the ViDec questionnaire guide to identify ACP preferences, goals and values, among others. One team member will lead the coding process and meet with team members to conduct peer debriefing sessions92 to discuss and resolve coding differences, refining, adding and deleting codes as needed.93 We will group similar codes to conduct a thematic analysis of the ViDec content and compare these themes over time for participants who record multiple ViDec recordings. After identifying the ACP preferences from the ViDecs (including expressions of preferences that are unclear), will indicate how often ACP preferences match or do not match the preferences stated in the medical record and in research surveys. Finally, we will use information from patients about the helpfulness and ease of making a ViDec and use a case study approach94 to identify subsets of patients, caregivers (who may or may not have seen the ViDec) and clinicians to describe the video intervention package along several dimensions including usefulness, understandability and relevance. NVivo V.12 will serve as the data management platform.

Regulatory considerations

The use of Institutional Review Board (IRB) review and approval, data use agreements among partners, and an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (online supplemental file 3) provide the foundation of regulatory efforts for VIDEO-KD. This study was approved via a single IRB (protocol version 3.0, Western IRB (WIRB) #20193321) as a multi-centre trial. Each study location established official agreements to use the WIRB as their primary regulatory agent. Any protocol changes will be communicated in written form by all relevant parties. This is a minimal risk study for study subjects and principal and site investigators will report unforeseen adverse events to the IRB. We have created committees of study personnel to manage oversight of project direction and administration, implementation, quality and monitoring of data, and regulatory/ethical considerations. A HIPAA authorisation was approved for the EHR review to identify potentially eligible study participants. Waivers of documentation of consent were approved for cognitive screening assessment and for caregiver surveys.

bmjopen-2021-059313supp003.pdf (61KB, pdf)

Ethics and dissemination

The VIDEO-KD trial will be the first large, multi-site trial to evaluate the impact of a video intervention on ACP and patient experience. The strengths of the study include the innovative video intervention and the diversity of the population of study participants. This study has the potential to add to a growing literature around the use of video decision aids and declarations in supporting people with advanced kidney disease as they learn about their illness and make decisions with clinical teams about what types of care help them to best achieve their goals. We aim to distribute results of this study through invited presentations and manuscripts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating site teams at each of our sites for their involvement in this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AmakaEMD, @lindvalllab

Contributors: AV designed and conceptualised the study, acquired data, drafted and critically revised the manuscript, obtained funding, supervise the study, and provided administrative and technical support. MP-O designed and conceptualised the study, acquired data, drafted and critically revised the manuscript, obtained funding, supervise the study, and provided administrative and technical support. NE designed and conceptualised the study, drafted and critically revised the manuscript and provided administrative and technical support. JRL drafted and critically revised the manuscript and provided administrative and technical support. CL designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. LH designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. ADH designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. ADD designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. AE-J designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. LMQ designed and conceptualised the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided administrative and technical support. YC acquired data, critically revised the manuscript, provided statistical analysis, and provided administrative and technical support. ETM, EIM, SPYW, SNZ, SW, ADB, JS, ALL, MKT, MKY, MU, CA, MG critically revised the manuscript and provided administrative and technical support.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, grant number R01 AG066892.

Competing interests: NE is a scientific advisor for Somatus and Davita. MKT has received honoraria from the American Federation of Aging Research and serves as Associate Editor at CJASN. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. AV has a financial interest in ACP decisions, a non-profit organisation developing advance care planning video decision support tools. AV’s interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies. No other disclosures to report.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–32. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:256–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-Of-Life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203–8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–73. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2006;333:886. 10.1136/bmj.38965.626250.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014;28:1000–25. 10.1177/0269216314526272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Baskin SA. Treatment of the dying in the acute care hospital. advanced dementia and metastatic cancer. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2094–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:321–6. 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorne SE, Bultz BD, Baile WF, et al. Is there a cost to poor communication in cancer care?: a critical review of the literature. Psychooncology 2005;14:875–84. 10.1002/pon.947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress 2008.

- 14.Eneanya ND, Olaniran K, Xu D, et al. Health literacy mediates racial disparities in cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge among chronic kidney disease patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29:1069–82. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladin K, Neckermann I, D'Arcangelo N, et al. Advance care planning in older adults with CKD: patient, care partner, and clinician perspectives. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;32:1527–35. 10.1681/ASN.2020091298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oskoui T, Pandya R, Weiner DE, et al. Advance care planning among older adults with advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD and their care partners: perceptions versus reality? Kidney Med 2020;2:116–24. 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, et al. Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:2487–94. 10.1681/ASN.2005020157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davison SN, Moss AH. Supportive care: meeting the needs of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:1879–80. 10.2215/CJN.06800616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 2015;88:447–59. 10.1038/ki.2015.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah KK, Murtagh FEM, McGeechan K, et al. Quality of life among caregivers of people with end-stage kidney disease managed with dialysis or comprehensive conservative care. BMC Nephrol 2020;21:160. 10.1186/s12882-020-01830-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USRDS . 2019 annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, 2019. www.usrds.org [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, et al. Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:177–83. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wachterman MW, O'Hare AM, Rahman O-K, et al. One-year mortality after dialysis initiation among older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:987. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2758–65. 10.1681/ASN.2007040422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Wahsh H, Tangri N, Quinn R, et al. Accounting for the competing risk of death to predict kidney failure in adults with stage 4 chronic kidney disease. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e219225. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.9225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2009;361:1539–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, et al. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:260–8. 10.2215/CJN.03330414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, et al. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1611–9. 10.2215/CJN.00510109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong SPY, Kreuter W, Curtis JR, et al. Trends in in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival in adults receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1028–35. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renal Physicians Association, American Society of Nephrology Working Group . A new clinical practice guideline on initiation and withdrawal of dialysis that makes explicit the role of palliative medicine. J Palliat Med 2000;3:253–60. 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss AH. Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:2380–3. 10.2215/CJN.07170810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns RB, Waikar SS, Wachterman MW, et al. Management options for an older adult with advanced chronic kidney disease and dementia: grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess medical center. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:217–25. 10.7326/M20-2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Hare AM, Song M-K, Kurella Tamura M, et al. Research priorities for palliative care for older adults with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Palliat Med 2017;20:453–60. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulsky JA. Improving quality of care for serious illness: findings and recommendations of the Institute of medicine report on dying in America. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:840–1. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu C-F, et al. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:305. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eneanya ND, Labbe AK, Stallings TL, et al. Caring for older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and considering their needs: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol 2020;21:213. 10.1186/s12882-020-01870-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlin J, Chesla CA, Grubbs V. Dialysis or death: a qualitative study of older patients' and their families' understanding of kidney failure treatment options in a US public hospital setting. Kidney Med 2019;1:124–30. 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eneanya ND, Percy SG, Stallings TL, et al. Use of a supportive kidney care video decision aid in older patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Nephrol 2020;51:736–44. 10.1159/000509711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.In: dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington DC: 2015 by the National Academy of sciences 2015. [PubMed]

- 40.Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J Palliat Med 2005;8:s-95–s-101. 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillick MR. Advance care planning. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2004;350:7–8. 10.1056/NEJMp038202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moss AH, Hozayen O, King K, et al. Attitudes of patients toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the dialysis unit. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;38:847–52. 10.1053/ajkd.2001.27705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volandes AE, Barry MJ, Chang Y, et al. Improving decision making at the end of life with video images. Med Decis Making 2010;30:29–34. 10.1177/0272989X09341587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volandes AE, Kennedy WJ, Davis AD, et al. The new tools: what 21st century education can teach us. Healthc 2013;1:79–81. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med 2008;11:754–62. 10.1089/jpm.2007.0224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Periyakoil VS, Kraemer H, Neri E. Multi-Ethnic attitudes toward physician-assisted death in California and Hawaii. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1060–5. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Jawahri A, Mitchell SL, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR and intubation video decision support tool for hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1071–80. 10.1007/s11606-015-3200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:380–6. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.9570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 2016;134:52–60. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:305–10. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, et al. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. J Palliat Med 2008;11:700–6. 10.1089/jpm.2007.0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals-of-care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med 2012;15:805–11. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, et al. Assessing end-of-life preferences for advanced dementia in rural patients using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2011;14:169–77. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Volandes AE, Lehmann LS, Cook EF. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:828–33. 10.1001/archinte.167.8.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Volandes AE, Levin TT, Slovin S, et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention-postintervention study. Cancer 2012;118:4331–8. 10.1002/cncr.27423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b2159. 10.1136/bmj.b2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis AD, et al. Use of Video Decision Aids to Promote Advance Care Planning in Hilo, Hawai‘i. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1035–40. 10.1007/s11606-016-3730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sudore RL, Boscardin J, Feuz MA, et al. Effect of the prepare website vs an Easy-to-Read advance Directive on advance care planning documentation and engagement among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1102. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video in advance care planning for progressive pancreas and hepatobiliary cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2013;16:623–31. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quintiliani LM, Murphy JE, Buitron de la Vega P, et al. Feasibility and patient perceptions of video Declarations regarding end-of-life decisions by hospitalized patients. J Palliat Med 2018;21:766–72. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schell JO, Cohen RA. Communication strategies to address conflict about dialysis decision making for critically ill patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:1248–50. 10.2215/CJN.00010118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD. Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:854–63. 10.2215/CJN.05760516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmidt RJ, Landry DL, Cohen L, et al. Derivation and validation of a prognostic model to predict mortality in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019;34:1517–25. 10.1093/ndt/gfy305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, et al. Provider knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding conservative management for patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:812–20. 10.2215/CJN.07180715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradshaw CL, Gale RC, Chettiar A, et al. Medical record documentation of goals-of-care discussions among older veterans with incident kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;75:744–52. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oestreich T, Sayre G, O'Hare AM. Perspectives on conservative care in advanced kidney disease: a qualitative study of US patients and family members. Am J Kidney Dis 2021;77:355–64. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gelfand SL, Mandel EI, Mendu ML, et al. Palliative care in the advancing American kidney health Initiative: a call for inclusion in kidney care delivery models. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:877–82. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lakin JR, Robinson MG, Bernacki RE, et al. Estimating 1-year mortality for high-risk primary care patients using the surprise question. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1863–5. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lakin JR, Robinson MG, Obermeyer Z, et al. Prioritizing primary care patients for a communication intervention using the “surprise question”: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:1467–74. 10.1007/s11606-019-05094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salat H, Javier A, Siew ED, et al. Nephrology provider prognostic perceptions and care delivered to older adults with advanced kidney disease. Clinical J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1762–70. 10.2215/CJN.03830417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975;23:433–41. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lakin JR, Brannen EN, Tulsky JA, et al. Advance care planning: promoting effective and aligned communication in the elderly (ACP-PEACE): the study protocol for a pragmatic stepped-wedge trial of older patients with cancer. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040999. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Volandes AE, Barry MJ, Wood F, et al. Audio-video decision support for patients: the documentary genré as a basis for decision AIDS. Health Expect 2013;16:e80–8. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00727.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. Measuring advance care planning: optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:669–81. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, et al. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res 1994;3:329–38. 10.1007/BF00451725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davis S, Mohan S. Managing patients with failing kidney allograft: many questions remain. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;17:444–51. 10.2215/CJN.14620920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O'Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making 1995;15:25–30. 10.1177/0272989X9501500105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Winterbottom AE, Gavaruzzi T, Mooney A, et al. Patient acceptability of the Yorkshire dialysis decision aid (YODDA) booklet: a prospective Non-Randomized comparison study across 6 predialysis services. Perit Dial Int 2016;36:374–81. 10.3747/pdi.2014.00274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volandes AE, Mitchell SL, Gillick MR, et al. Using video images to improve the accuracy of surrogate decision-making: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:575–80. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nichols GA, Ustyugova A, Déruaz-Luyet A, et al. Health care costs by type of expenditure across eGFR stages among patients with and without diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;31:1594–601. 10.1681/ASN.2019121308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donner A, Klar N. Statistical considerations in the design and analysis of community intervention trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:435–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00511-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lindvall C, Lilley EJ, Zupanc SN, et al. Natural language processing to assess end-of-life quality indicators in cancer patients receiving palliative surgery. J Palliat Med 2019;22:183–7. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Poort H, Zupanc SN, Leiter RE, et al. Documentation of palliative and end-of-life care process measures among young adults who died of cancer: a natural language processing approach. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2020;9:100–4. 10.1089/jayao.2019.0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Udelsman BV, Lilley EJ, Qadan M, et al. Deficits in the palliative care process measures in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer undergoing operative and invasive Nonoperative palliative procedures. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:4204–12. 10.1245/s10434-019-07757-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindvall C, Deng CY, Moseley E. Natural language processing to identify advance care planning documentation in a multisite pragmatic clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lakin JR, Gundersen DA, Lindvall C, et al. A yet Unrealized promise: structured advance care planning elements in the electronic health record. J Palliat Med 2021;24:1221–5. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. London: Arnold, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liem YS, Bosch JL, Hunink MGM. Preference-based quality of life of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health 2008;11:733–41. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Briggs AH, Mooney CZ, Wonderling DE. Constructing confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios: an evaluation of parametric and non-parametric techniques using Monte Carlo simulation. Stat Med 1999;18:3245–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. 117. SAGE Publications, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1758–72. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-059313supp001.pdf (667.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059313supp002.pdf (45.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059313supp003.pdf (61KB, pdf)