Abstract

Delayed in Transit, the report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) on acute bowel obstruction (ABO), highlighted a number of areas for improvement in this group of patients. The overarching finding was that there were delays in the pathway of care for patients with ABO at every stage of the clinical pathway, including diagnosis, decision-making and the availability of operating theatres. Furthermore, basic measures including hydration, nutritional screening and nutritional assessment were noted to be deficient. Patients who were admitted to non-surgical wards had an increased risk of delayed treatment and subsequently a longer starvation period. There was room for improvement of nutritional screening and assessment on admission, throughout the hospital stay and on discharge. A selection of the report recommendations that address these areas requiring improvement is discussed here.

Keywords: abdominal surgery, colorectal surgery, nutritional status

Introduction

Acute bowel obstruction (ABO) is a painful condition that occurs when there is an interruption to the forward flow of intestinal contents. It can occur in the small or large bowel and can be associated with life-threatening complications, accounting for up to 12%–16% of emergency surgical admissions.1 In the small bowel, obstruction is most commonly caused by adhesions from previous surgery, followed by hernias, inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy. Malignancy and volvulus are the most common causes of large bowel obstruction.2

The majority of patients requiring surgery are ‘high-risk’, as their mortality can exceed 10%, higher than seen in elective gastrointestinal (GI) surgery. ABO is more common in older adults who may be frail. The incidence of bowel obstruction increases with age; the median age at diagnosis is 64 years.3

Patients with ABO require careful observation and consultant-led care throughout their hospital stay, before and after any surgery.

Hydration and nutritional status are particularly important in patients with ABO. Up to half of patients will have had a period of prolonged starvation and up to one-third will be at risk of malnutrition.4 Reduced fluid intake and fluid shifts from ABO mean that patients are at particular risk of acute kidney injury (AKI).

Despite this being a high-risk group of patients with specific healthcare requirements, potentially requiring time-critical interventions, the published guidance is fragmented. Currently, there is no one unifying national guideline/framework for the management of ABO and there is considerable variation in care and outcomes.2 5–7

‘Delay in Transit’ published by NCEPOD described the quality of care provided to patients with either large or small bowel obstruction throughout their hospital stay. The recommendations made in this report are targeted at clinicians and management to make changes in practice with the aim of improving the care provided to this group of patients. A selection of the report recommendations that focus on the nutrition, hydration and delay in diagnosis and treatment for patients with ABO is discussed here. The full report with its complete list of recommendations can be found at https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2020abo.html. 8

Method

Data were collected on patients aged 16 and older who had an ABO either on presentation to hospital or during a hospital admission. Patients admitted to hospital between 16 April and 13 May 2018 were identified retrospectively from hospital records through International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems- 10th Revision (ICD10) codes for conditions associated with ABO. From the patients identified, a maximum of 10 per hospital were pseudorandomly selected for inclusion in the review using a stratified sampling methodology, split between medical and surgically treated patients and including a maximum of two patients who had died and two patients who had AKI.

A comprehensive questionnaire was completed by the admitting consultant clinician for 690 patients and a multidisciplinary group of healthcare professionals undertook peer review using the case notes of 294 patients. This group comprised clinical nurse specialists, senior dietitians and consultants, and trainees from the following specialties: colorectal surgery, general surgery, hepatobiliary/pancreatic surgery, upper GI surgery, anaesthesia, intensive care medicine, acute medicine, emergency medicine, gastroenterology and radiology.

Results

Study population

Out of 668 patients, 476 (71.3%) were reported to have a small bowel obstruction and 158 (23.7%) were reported to have a large bowel obstruction. A further 34 out of 668 (5.1%) patients had both small and large bowel obstruction. The study population had a median age of 59.4 years (range 19–99 years).

Acute kidney injury

The fluid shifts associated with bowel obstruction coupled with impaired oral intake of fluids mean that hypovolaemia is a significant risk in ABO. Early fluid resuscitation and awareness of the risk of AKI can help to prevent deterioration in renal function and to improve patient outcome.9

It is impossible to extrapolate the results of this study to ascertain the risk of AKI in patients with ABO as the selection criteria for the study specified that 2 of every 10 patients from a given hospital had to have had AKI.

The case reviewers found that 69 out of 264 (26.1%) patients had AKI at their initial assessment. A further 16 patients developed AKI following admission, and in 4 of these patients, the AKI was thought to be avoidable if adequate fluid resuscitation had taken place. In the view of the clinicians completing questionnaires, 180 out of 666 (27.0%) patients had AKI on admission and fluid resuscitation was inadequate in 10 out of 178 (5.6%). Recommendation 5 in the NCEPOD report states that for patients presenting with symptoms of ABO, hydration status should be recorded from first presentation in the emergency department and throughout the admission (box 1).8

Box 1. Recommendation 5 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit—Recommendation 5:

Measure and document hydration status in all patients presenting with symptoms of acute bowel obstruction in order to minimise the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI). Ensure that hydration status is:

Assessed at presentation to the emergency department.

Assessed throughout the admission.

Nutritional support

Mechanical bowel obstruction has a significant effect on oral intake and therefore patients presenting with obstruction are at risk of malnutrition. This risk of malnutrition is associated with poorer clinical outcomes such as delayed wound healing, reduced muscle strength and fatigue, and longer hospital length of stay. If the patient goes on to have surgical intervention with prolonged periods of fasting, then these issues are exacerbated.10

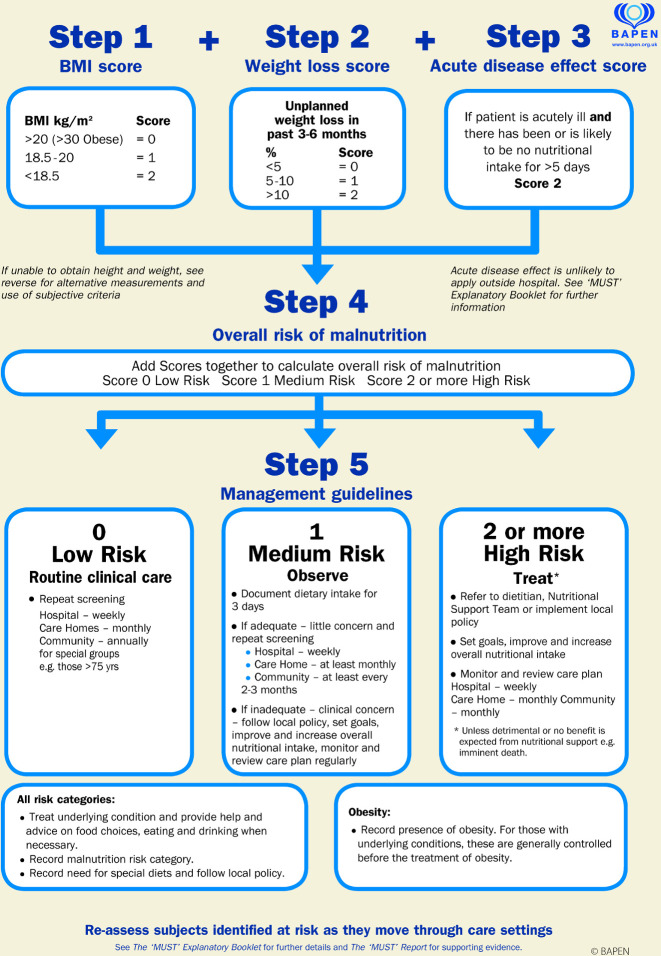

The ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’) is a tool used to identify adults who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition and includes three steps (figure 1). Steps 1 and 2 determine Body Mass Index (BMI) and percentage weight loss, respectively. Step 3 assesses the impact of the disease and asks, ‘If patient is acutely ill and there has been or is likely to be no nutritional intake for >5 days’. If the answer to this question alone is ‘yes’, then a score of 2 is recorded and the patient should be referred to the dietitian or nutritional support team or implement local policy.11 Once a referral has been made, a dietitian will complete a nutritional assessment. This is different from screening, as it involves a more complex assessment of nutritional, biochemical, clinical, dietary, environmental and functional status, and how these impact on the patient.12

Figure 1.

‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’) is reproduced here with the kind permission of BAPEN (British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition). For further information on ‘MUST’, see https://www.bapen.org.uk/.11 BMI, Body Mass Index.

The interpretation of weight and BMI may be inaccurate in patients with ABO who have significant fluid shifts caused by either the disease or intravenous rehydration. This means that steps 1 and 2 of the ‘MUST’ cannot be relied on and reinforce the need to consider the disease process (step 3) in identifying patients at risk of malnutrition. Therefore, education around step 3 may improve referrals to the appropriate staff. In the NCEPOD report, 496 out of 647 (76.7%) patients were on a surgical ward; these wards should therefore be targeted for training.

On admission to hospital

In the UK, up to 29% of all patients admitted to hospital are at risk of malnutrition.13 The symptoms that patients presented with in the NCEPOD report included abdominal pain in 438 out of 690 (63.5%), nausea and vomiting in 302 out of 690 (43.8%), and distension in 94 out of 690 (13.6%), all of which would have contributed to reduced oral intake. Furthermore, it was noted that on arrival to hospital, 41 out of 163 (25.2%) patients (for whom it was documented) had already been starved for more than 24 hours. The detection and treatment of malnutrition in the context of ABO should therefore be a top priority. However, the results from the NCEPOD report indicated that nutrition was an often-overlooked issue.

The importance of taking a good patient history, including the number of days of reduced oral intake preadmission, is the responsibility of the multidisciplinary team looking after the patient. In the NCEPOD report, reviewers noted that this was only recorded in 163 out of 294 (55.4%) patients.

Out of 516 patients, 271 (52.5%) had a ‘MUST’ score recorded on admission, but the accuracy of this score was unknown. Additionally, case reviewers in the NCEPOD report were of the opinion that on admission to hospital, a complete nutritional assessment was either not performed (when it should have been) or inadequate in 105 out of 254 (41.3%) patients.8

Postoperatively

Out of 181 patients, 35 (19.3%) did not have any ongoing nutritional screening or assessment. Only 105 out of 191 (55.0%) had a repeat ‘MUST’ score if their length of stay was over 7 days. The mean length of stay was 12.4 days and therefore the ‘MUST’ should have been repeated in those patients.11

It was noted that barriers to implementing nutrition support occurred in 108 out of 356 (30.3%) patients in the NCEPOD report and included ileus in 54 patients and increased nasogastric aspirates in 7 patients. These represent type 1 intestinal failure and are indications for short-term parenteral nutrition (PN).

In the NCEPOD report, the evidence of supplemental enteral nutrition (EN) or PN in patients was variable. Of those undergoing surgery, 43 out of 390 (11.0%) had EN and 102 out 390 (26.2%) had PN. Only 17 out of 292 (5.8%) and 12 out of 292 (4.1%) non-surgical patients received EN and PN, respectively. Of those that did not undergo supplemental feeding, clinicians answering the clinician questionnaire self-reported that 34 out of 266 (12.8%) should have done.8

There may be a reluctance to start PN due to the belief that it increases complications including catheter-related bloodstream infections. However, one study has demonstrated few differences in septic complications between PN and EN, while other complications such as vomiting, diarrhoea and tube misplacement were more commonly seen in patients who received EN, which was also associated with a higher morbidity and mortality. The study concluded that patients who have reduced GI function (eg, ABO) should be fed by the parenteral route under the supervision of an experienced dedicated nutrition team.14

On discharge

Only 88 out of 233 (37.8%) patients had an assessment of their nutrition documented at discharge, and 147 out of 409 (35.9%) did not appear to receive any nutritional advice. It was possible that a patient referred to dietitians during their stay would have been reviewed as an outpatient either in clinic or referred to a community dietitian. However, from the organisational data, the discharge planning team did not include a dietitian in 68 out of 149 (45.6%) hospitals in this study.8

Dietitians are uniquely qualified to provide impartial dietary advice to individuals regarding food-related difficulties, to improve health and to treat conditions including bowel obstruction and malnutrition. Dietitians will also be able to advise patients who have had a bowel obstruction on maintaining a nutritionally adequate diet and on the manipulation of fibre to reduce the incidence of obstruction, they can also provide advice on what to do if obstruction occurs at home and how to reduce the risk of malnutrition. Simple advice such as chewing food thoroughly can make an impact. Recommendation 6 in the NCEPOD report emphasises the need for ‘MUST’ screening and dietetic review of patients with ABO throughout their hospital admission (box 2).8

Box 2. Recommendation 6 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit—Recommendation 6:

You should undertake, record and act on nutritional screening in all patients who present with symptoms of acute bowel obstruction. This should include:

‘MUST’ score on admission to hospital.

‘MUST’ score at least weekly throughout admission.

Review by a dietitian/nutrition team once a diagnosis has been made.

‘MUST’ score, and if required a dietitian/nutrition team assessment at discharge.

Delays in assessment, diagnosis and treatment

Timely assessment, diagnosis and treatment are all pivotal stages in the optimal care of patients with ABO. Delays in any of the above can further exacerbate protracted periods of starvation (due to symptoms of ABO or induced perioperatively), leading to a higher risk of malnutrition and associated complications.15

The NCEPOD report found that all these key stages of the pathway could be improved on. Out of 291 patients, 126 (43.3%) whose care was reviewed experienced some delay in their treatment pathway (table 1). The following describes the delays that occurred and the recommendations that can be implemented to avoid such delays.8

Table 1.

Delays in the pathway of care in the NCEPOD report—Delay in Transit

| Reported delay in pathway of care | Patients (n) | Percentage |

| Total number patients who had a delay at some point in the pathway of care* | 126/291 | 43.3% |

| Delay in imaging* | 57/276 | 20.7% |

| Delay in diagnosis of ABO* | 51/285 | 17.9% |

| Delay in surgery† | 72/368 | 19.6% |

*Case review data.

†Clinician questionnaire data.

ABO, acute bowel obstruction.

Assessment

An early consultant review is essential in the patient journey.

The NCEPOD report showed clear evidence of delays in consultant assessment which in turn led to a delay in diagnosis in 13 out of 32 (40.6%) patients. Only 23 out of 147 (15.6%) patients who were seen in a timely manner by a consultant experienced a delay in diagnosis. The report echoed the recommendation made by the Royal College of Physicians of London16 and NHS England17 that patients should be reviewed by a consultant within 14 hours of admission to hospital (box 3) and also recommended that patients with a definitive diagnosis should be admitted under the care of a surgical team (box 4).8

Box 3. Recommendation 2 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit—Recommendation 2:

A consultant review should be undertaken in all patients diagnosed with acute bowel obstruction and at the latest within 14 hours of admission to hospital. Discussion with a consultant should occur within an hour for high-risk patients*.

Box 4. Recommendation 3 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit—Recommendation 3:

Admit patients with symptoms of acute bowel obstruction as necessary, but patients who have a definitive diagnosis of acute bowel obstruction should be admitted under the care of a surgical team.

Diagnosis

An early contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan is mandatory.

The report clearly highlights that timely imaging is essential in avoiding delays in diagnosis. There were delays in imaging in 57 out of 276 (20.7%) of the cases reviewed and the delays increased if an abdominal X-ray was performed as well as an abdominal CT. Furthermore, a delay in imaging led to a delay in diagnosis in 35 out of 57 (61.4%) patients, whereas only 14 out of 219 (6.4%) patients had a delay in diagnosis if there was no delay in imaging. The report recommends therefore that a prompt CT scan with intravenous contrast should be carried out as the definitive method of imaging for patients with suspected ABO (box 5).8

Box 5. Recommendation 1 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report—Recommendation 1

Undertake a CT scan with intravenous contrast promptly, as the definitive method of imaging* for patients presenting with suspected acute bowel obstruction. Prompt radiological diagnosis will help ensure admission to the correct specialty, so the time to CT reporting should be audited locally.

Treatment

Timely surgical treatment is essential in the patient journey.

Clinician questionnaire data in the report indicated delays in accessing appropriate surgical treatment, with 72 out of 368 (19.6%) patients experiencing a delay in access to surgery, and in 38 out of 72 (52.8%) patients, the delay was due to non-availability of theatre, and in 34 out of 72 (47.2%), it was due to non-availability of an anaesthetist. Case review data also showed a delay to surgery for 29 out of 172 (16.9%) patients. The report recommends that local policies are put in place that enable patients with ABO requiring surgery to have rapid access to the operating theatre (box 6).8

Box 6. Recommendation 8 in the NCEPOD report: Delay in Transit.

NCEPOD report—Recommendation 8

Ensure local policies are in place for the escalation of patients requiring surgery for acute bowel obstruction to enable rapid access to the operating theatre.* This should be regularly audited to ensure adequate emergency capacity planning.

Top tips for the optimal care of patients with ABO

The main areas of care that were found to require improvement in the NCEPOD report—Delay in Transit are summarised in the infographic in figure 2. The recommendations from the report aim to address these areas of care in this high-risk group of patients and can be condensed into the following key tips for healthcare professionals caring for patients with ABO shown in box 7.

Figure 2.

Infographic showing the key areas for improvement in the NCEPOD report—Delay in Transit. This image and the full report can be found at https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2020abo.html.8

Box 7. Top tips for the care of patients with ABO.

Top tips for the care of patients with ABO

-

Ensure early assessment and recognition of acute bowel obstruction.

This is pivotal in improving patient outcomes.

-

Ensure early consultant assessment.

This reduces delays in diagnosis.

-

Ensure an early CT abdomen with IV contrast (except in severe AKI) is undertaken.

This reduces delays in diagnosis and is essential to diagnose ischaemia and closed loop obstruction.

-

Ensure adequate hydration.

This is essential to avoid AKI.

-

Ensure that nutritional screening has been undertaken, for example, MUST score.

This is essential to identify patients at risk of malnutrition and avoid deterioration in nutritional status.

Once a diagnosis of acute bowel obstruction has been made, ensure the patient is referred to a dietitian and reviewed by the nutrition team.

-

Ensure that there is adequate nutritional supplementation by oral, enteral or parenteral route.

Depending on the nature and severity of the obstruction throughout the patient journey.

Take into account any periods of starvation prior to surgery when planning instigation of nutritional support.

-

Develop a local evidence-based pathway for ABO.

To minimise delays to diagnosis and treatment.

The pathway should be audited at specific timepoints such as (1) time from arrival to CT scan, (2) time from arrival to diagnosis, (3) time from decision to operate to start of anaesthesia.

Include nutritional screening, assessment and supplementation.

-

Ensure that medical and surgical colleagues are made aware of the NCEPOD report and its recommendations.

Via clinical governance meetings and highlight to clinical and medical directors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at NCEPOD for their work in collecting and analysing the data for this study and particularly, Marisa Mason, who provided oversight to the project and editorial advice in the preparation of this manuscript. Thanks also to BAPEN (British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition) for allowing us to reproduce the ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’.

Footnotes

Twitter: @QI_surgeon

Contributors: AC was part of the Study Advisory Group who helped design the study. MS and AM were clinical coordinators leading the study and HS oversaw the data collection. ACD was one of the case reviewers, contributing to data collection for the study. HS carried out the data analysis, and MS and AM wrote the resulting NCEPOD report. MS planned the article and contributed it. AM contributed to, reviewed and edited the article. AC and ACD contributed to and reviewed the article. HS contributed to, reviewed, edited and submitted the article.

Funding: The NCEPOD review of acute bowel obstruction was commissioned by The Health Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP). HQIP is led by a consortium of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, the Royal College of Nursing, and National Voices. Its aim is to promote quality improvement in patient outcomes, and in particular, to increase the impact that clinical audit, outcome review programmes and registries have on healthcare quality in England and Wales. HQIP holds the contract to commission, manage, and develop the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP), comprising around 40 projects covering care provided to people with a wide range of medical, surgical and mental health conditions. The programme is funded by NHS England, the Welsh Government and, with some individual projects, other devolved administrations, and crown dependencies (http://www.hqip.org.uk/national-programmes).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Maung AA, Johnson DC, Piper GL, et al. Evaluation and management of small-bowel obstruction: an eastern association for the surgery of trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:S362-9. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827019de [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finan PJ, Campbell S, Verma R, et al. The management of malignant large bowel obstruction: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis 2007;9 Suppl 4:1–17. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drożdż W, Budzyński P. Change in mechanical bowel obstruction demographic and etiological patterns during the past century: observations from one health care institution. Arch Surg 2012;147:175–80. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland . Report of the National audit of small bowel obstruction. Available: https://www.acpgbi.org.uk//content/uploads/2017/12/NASBO-REPORT-2017.pdf [Accessed 4 Dec 2020].

- 5. Ten Broek RPG, Krielen P, Di Saverio S, et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2017 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world Society of emergency surgery ASBO Working group. World J Emerg Surg 2018;13:24. 10.1186/s13017-018-0185-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guideline for the management of colorectal cancer: NICE NG151. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151 [Accessed 4 Dec 2020]. [PubMed]

- 7. National Emergency Laparotomy Audit . Fourth patient report of the National emergency laparotomy audit, 2018. Available: https://www.nela.org.uk/Fourth-Patient-Audit-Report#pt [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 8. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) . Delay in transit: a review of the quality of care provided to patients aged over 16 years with a diagnosis of acute bowel obstruction, 2020. Available: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2020abo/ABO_report%20final.pdf [Accessed 20 Jan 2021].

- 9. Bhatraju PK, Zelnick LR, Chinchilli VM, et al. Association between early recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury and long-term clinical outcomes. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e202682. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gustafsson UO, Ljungqvist O. Perioperative nutritional management in digestive tract surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2011;14:504–9. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283499ae1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition . The ‘MUST’ report: nutritional screening of adults: a multidisciplinary responsibility, 2003. Available: https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must-report.pdf [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 12. The BDA- the Association of British Dietitians . Model and process for nutrition and dietetic practice, 2012. Available: https://www.bda.uk.com/uploads/assets/395a9fc7-6b74-4dfa-bc6fb56a6b790519/ModelProcess2016v.pdf [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 13. Stratton R. Trevor Smith and Simon Gabe on behalf of BAPEN. managing malnutrition to improve lives and save money, 2018. Available: https://www.bapen.org.uk/news-and-media/news/718-managing-malnutrition-to-improve-lives-and-save-money [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 14. Woodcock NP, Zeigler D, Palmer MD, et al. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition: a pragmatic study. Nutrition 2001;17:1–12. 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00576-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee MJ, Sayers AE, Drake TM, et al. Malnutrition, nutritional interventions and clinical outcomes of patients with acute small bowel obstruction: results from a national, multicentre, prospective audit. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029235. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rcp acute care toolkit4: delivering a 12-hour, 7-day consultant presence on the acute medical unit, 2012. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/resources/acutecaretoolkit-4-delivering-12-hour-7-day-consultantpresenceacute-medical-unit [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 17. NHS England . Nhs services, seven days a week forum. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/forum-summary-report.pdf [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].