Abstract

Rationale

Intensive care unit (ICU) visitation restrictions during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic have drastically reduced family-engaged care. Understanding the impact of physical distancing on family members of ICU patients is needed to inform future policies.

Objectives

To understand the experiences of family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19 when physically distanced from their loved ones and to explore ways clinicians may support them.

Methods

This qualitative study of an observational cohort study reports data from 74 family members of ICU patients with COVID-19 at 10 United States hospitals in four states, chosen based on geographic and demographic diversity. Adult family members of patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 during the early phase of the pandemic (February–June 2020) were invited to participate in a phone interview. Interviews followed a semistructured guide to assess four constructs: illness narrative, stress experiences, communication experiences, and satisfaction with care. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using an inductive approach to thematic analysis.

Results

Among 74 interviewees, the mean age was 53.0 years, 55% were white, and 76% were female. Physical distancing contributed to substantial stress and harms (nine themes). Participants described profound suffering and psychological illness, unfavorable perceptions of care, and weakened therapeutic relationship between family members and clinicians. Three communication principles emerged as those most valued by family members: contact, consistency, and compassion (the 3Cs). Family members offered suggestions to guide clinicians faced with communicating with physically distanced families.

Conclusions

Visitation restrictions impose substantial psychological harms upon family members of critically ill patients. Derived from the voics of family members, our findings warrant strong consideration when implementing visitation restrictions in the ICU and advocate for investment in infrastructure (including staffing and videoconferencing) to support communication. This study offers family-derived recommendations to operationalize the 3Cs to guide and improve communication in times of physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Keywords: communication, coronavirus disease, critical care, postintensive care syndrome-family

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has brought strict visitation limitations with physical distancing (i.e., prohibiting family member presence at bedside) to hospitals across the world (1–4). These restrictions, instituted to maximize public safety and reduce potential spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, have dramatically changed the intensive care unit (ICU) experience for patients and families. Patients are routinely isolated from family and separated from staff via extensive personal protective equipment (PPE) and closed doors (5), limiting overall human interaction. Family members are reliant on phone or video communication for daily updates, medical decision-making, and end-of-life discussions, leading to a condensed and disconnected dynamic with clinicians (6, 7).

Even in prepandemic circumstances, up to 30% of family members of ICU patients experience overt post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and up to 50% experience prolonged symptoms of anxiety and depression (8–14). Family engagement with the ICU team improves psychological outcomes for patients and families in both the short-term and long-term (15–19) and is recommended in family-centered care guidelines (20). Often reflected by family presence at the bedside and participation in team rounds (21, 22), family-centered care validates the pivotal role of family members during a patient’s critical illness and recovery.

Our team conducted a multisite, mixed-methods observational cohort study to quantitatively describe and qualitatively explore the experiences of family members of patients admitted to the ICU during times of strict visitation restriction. This manuscript reports the qualitative results of a subset of the participants. The parent study documented substantial stress and PTSD in 63% of 330 family members at 3-month follow-up (23). Our qualitative research objective was to explore those experiences to more fully understand the ramifications of physical distancing and develop recommendations to guide clinicians in supporting these families.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The parent study included 12 hospitals across five U.S. states (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Ten sites from four states were chosen for qualitative interviewing based on geographic variation and socioeconomic diversity. These included seven academic and three community hospitals from four states (New York, Colorado, Louisiana, and Washington), all of whom disallowed visitation during the study.

Participants were eligible for the parent study if they were English-speaking family members of patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19 between February and June of 2020. Approximately 3 months after ICU admission, eligible family members were invited to complete validated quantitative questionnaires, including the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6), which measures symptoms of stress-related disorders (IES-6 scores ⩾10 are associated with symptoms of PTSD) (24). Three months after ICU stay was chosen as the interview time point, as is common in trials examining stress after ICU stay (16, 25, 26) and allows participants time to process the experience and grieve (if applicable). Quantitative data from the parent study are reported separately (23).

A convenience sample of participants from the qualitative sites were invited to participate in an additional 30-minute semistructured phone interview. The sample included consecutive and willing family members at each qualitative site (Table E1). In New York City, however, a random sample of 25% of each month’s admissions were called secondary to high patient volume. Verbal informed consent was obtained at the time of the phone interview. Reasons for nonconsent are detailed in Methods E1. This study was approved by the [redacted] Institutional Review Board. Qualitative participants received a $25 stipend for participating.

Interview

Interviewers followed a semistructured guide (Methods section E2) that assessed four constructs: illness narrative, stress, communication, and satisfaction with care. Interviewers were provided with relevant data from the parent study (contact information, date of ICU admission, patient survivorship, and IES-6 score). Questions related to stress were tailored by family members’ IES-6 scores (high: ⩾10; low: <10) (Methods E1). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Qualitative Analysis

We used an ontological philosophical assumption that is appropriate when asking, “what is the nature of reality” (in this case, the experience of having a critically ill loved one with COVID-19) (27). A descriptive phenomenological approach was used for inductive thematic analysis, as the intent was to uncover both expected and unexpected phenomena.

Transcripts were analyzed using qualitative software (NVivo 12) (28). A preliminary codebook was created by five authors with diverse backgrounds who independently identified emerging concepts and codes. Saturation was achieved after reviewing 20% of transcripts. Five analysts used the preliminary codebook to apply the constant comparison method to code the data (29). Each transcript was coded by two different analysts, and Cohen’s kappa reports were used to identify and discuss coding discrepancies. Codes were adjudicated by a third analyst to ensure interrater reliability. Coding patterns and frequencies were reviewed by two authors who developed themes and subthemes, which were independently reviewed by a third author. Methods section E2 provides additional details relevant to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ).

Results

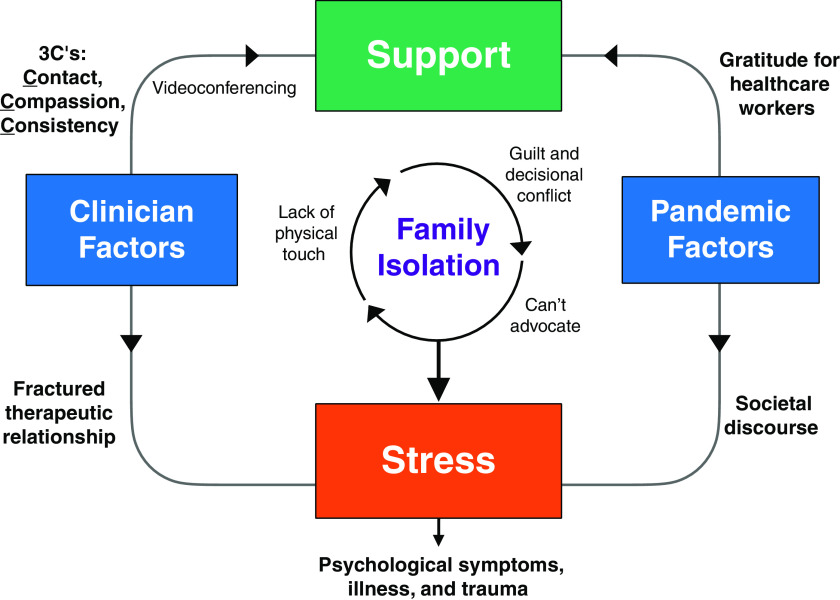

Table 1 reports the participant characteristics. They had a mean age of 53.0, 55% were white, and 76% were female. Nine themes related to stress emerged from the data, which we grouped into three overarching categories: stress related to having a critically ill loved one with COVID-19; clinician behaviors associated with alleviating or increasing this stress; and the contextual features of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tables 2 and 3 present the themes, subthemes, and representative quotations. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between the themes.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N = 74)

| Mean age (range) | 53.0 (18–93) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 56 (75.7%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (23.0%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 54 (73.0%) |

| No answer given | 3 (4.1%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 41 (55.4%) |

| Black/African American | 18 (24.3%) |

| Asian | 4 (5.4%) |

| Other* | 6 (8.1%) |

| No answer given | 5 (6.8%) |

| Site, n (%) | |

| New York City, NY (3 academic hospitals) | 17 (22.9%) |

| Kirkland, WA (1 community hospital) | 14 (18.9%) |

| Renton, WA (1 community hospital) | 3 (4.1%) |

| New Orleans, LA (1 academic hospital) | 10 (13.5%) |

| Denver, CO (1 academic hospital) | 17 (22.9%) |

| Seattle, WA (2 academic hospitals, 1 community hospital) | 13 (17.6%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school degree/equivalent or less | 11 (14.9%) |

| Trade school/some college | 19 (25.7%) |

| 4-yr college degree | 25 (33.8%) |

| Some graduate school/graduate degree | 19 (25.7%) |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | |

| Spouse/partner | 23 (31.1%) |

| Child | 26 (35.1%) |

| Sibling | 14 (18.9%) |

| Parent | 4 (5.4%) |

| Other† | 7 (9.5%) |

| Lives with Patient, n (%) | |

| Yes | 35 (47.3%) |

| No | 39 (52.7%) |

| Patient Survivorship, n (%) | |

| Patient survived | 38 (51.4%) |

| Patient deceased | 32 (43.2%) |

| Missing data | 4 (5.4%) |

| IES-R Total Score, n (%) | |

| IES-R <10 | 25 (33.8%) |

| IES-R ⩾10 | 49 (66.2%) |

Definition of abbreviation: IES-R = impact of event scale-revised.

African American and Indian, Hispanic, Jamaican, or Mexican.

Brother-in-law, friend, granddaughter, niece, professional guardian, or sister-in-law.

Table 2.

Themes (1–4), subthemes, and quotes related to family members’ stress while having a critically ill loved one during visitation restrictions and physical distancing

| Themes/Subthemes | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Inpatient visitation restrictions generated deep, emotional personal anguish and suffering. | |

| 1A. Feared their loved ones felt isolated or would die alone | “Knowing that he was isolated, and he was by himself, and we couldn’t be there with him to remind him that he wasn’t alone.” (Spouse, WA) “The scariest part was just not being able to be there to explain to her what was going on.” (Sibling, CO) |

| 1B. Yearned for physical presence and touch | “I think that having your family members there holding your hand, even though they can’t change the outcome, there’s– comfort.” (Child, WA) “We were there [on video], but we were not physically there for him. That was the hardest part of being in that room [but you can’t even] hold his hand for five minutes, and that’s all I was asking.” (Child, CO) |

| 1C. Overwhelmed by guilt, helplessness, and decisional conflict | “I would drop things off for him and I wrote on the bag: ‘We are not abandoning you. We can’t visit you.’ It broke my heart. And I told the staff, can you please, please tell my parents that I’m not abandoning them.” (Child, WA) “The stress is really because, what if I make the wrong decision? What if I should have done something, and what if I make a decision that’s going to ultimately be harmful to her and not have the best outcome?” (Other relative, NY) |

| 1D. Hard to advocate for their loved ones’ care | “My mom had dementia and COPD, which is why she was in the nursing home. And I could not advocate for her, like in two previous hospital stays…I was there and could actually interpret for her.” (Child, WA) “When you take away that extra support system for that patient, I feel like it might decline the patient a little bit quicker compared to if they had a support system there to advocate for them.” (Friend, CO) |

| Theme 2. The therapeutic relationship between family and clinicians suffered from fractured trust and ineffective communication. | |

| 2A. Struggled to take information at face value when they couldn’t see it for themselves | “We just had to believe whatever the nurse or the doctor was saying…I got so stressed out that I even asked one of the doctors to see a picture of him because I was doubting myself that he was still alive.” (Sibling, NY) “So it was really, really stressful because you were reliant on – and I’m not saying that clinicians are not truthful by any means – but you were relying on somebody else without being able to see it for yourself.” (Spouse, WA) |

| 2B. Perceived circumstances would be different if they were there in person | “I almost felt like, if I’m there, they know who I am, maybe they’ll take better care of my dad… if they had a [face to the name] and they saw family and they saw how much he was loved. They would do everything in their power and make sure that he fights through this.” (Child, CO) “From a minority standpoint, there’s always been distrust with health professionals, especially ones that don’t look like us… I wanted to make sure that I at least knew and confirmed that he was under the right team’s care, and that they were going to prioritize his health at all times. It was important for them to see me.” (Child, NY) |

| 2C. Goals of care conversations felt premature and pressured. | “I thought it was insensitive for the doctor to keep pressing me to give them permission to Do Not Resuscitate… knowing that the hospital had been on lockdown and knowing that the person probably hadn’t seen their loved one.” (Spouse, LA) “This doctor called me and said, I don’t think it’s a good idea to just give him oxygen because the chances of your dad of surviving is almost zero, so he’s just suffering… I was wondering if they are doing the right thing considering that they [already] think he’s a dead person.” (Child, WA) |

| Theme 3. Substantial psychological symptoms and illness were common in family members. | |

| 3A. Many described stress that manifested as physical symptoms. | “I couldn’t sleep. I lost weight. It was hard. I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy to go through that.” (Spouse, LA) “I’m very sensitive now to stress. It’s easier for me to have a panic attack from stress than it used to be.” (Guardian, NY) |

| 3B. Some described experiences as traumatic, noted ‘triggering’ episodes | “Not able to touch him, hug on him when he did pass, was hard. I had to ID him a week after he passed. And that was really hard too because it’s like dealing with the trauma of losing someone to a violent crime.” (Child, NY) “There’s the flashbacks of everything happening and how hard this was. So, it all kind of just comes back at once sometimes.” (Child, WA) |

| 3C. Some sought psychiatric care or medications. | “I actually entered a psychiatric unit. All of these experiences, much less the experience of having my spouse in the ICU and deathly ill and almost losing him, contributed to my breakdown.” (Spouse, WA) “I got some meds. I only took, like, a half a dose night. But that helped me.” (Spouse, WA) |

| Theme 4. Participants identified primarily positive coping strategies to address their distress. | |

| 4A. Many focused on maintaining hope and some semblance of normalcy. | “I tried to get out and get some exercise every day even if it was just taking a mile or two walk. That helps as well to deal with stress.” (Other relative, NY) “Just trying to take time to myself and just get my mindset back in a positive place. That kind of helps me a little bit.” (Sibling, CO) |

| 4B. Family and faith were prominent sources of support. | “My church members and my pastors and ministers, they were calling me throughout the night. There was always someone to talk to me, pray with me, and keep me comfortable because I was by myself.” (Spouse, CO) “I have bereavement groups. I have a therapist. I’m taking antidepressants and medication for anxiety.” (Spouse, NY) |

| 4C. A minority of participants used self-medicating strategies. | “Toward the second week of it, I would say I took a drink. And that seemed to calm me down. So, a drink a night just kept me calm.” (Spouse, LA) “And I can say this out loud because it’s legal. Cannabis kind of helped calm me down a little bit.” (Spouse, WA) |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU = intensive care unit.

Table 3.

Themes (5-9), subthemes, and quotes related to healthcare team behaviors and contextual pandemic features

| Themes/Subthemes | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Theme 5. Participants valued proactive, frequent, and consistent contact with providers. | |

| 5A. Daily updates with clear, detailed information were critical. | “It helps that we had clear consistent communication…I felt like I was able to perfectly visualize exactly what [the doctor] was saying… I’ve never once felt that I made the wrong decision or that I needed more information.” (Child, WA) “The doctors would call either morning or afternoon after their rounds to update us on his progress. But because they were keeping in contact with us and updating us regularly, it definitely made it a lot easier.” (Child, WA) |

| 5B. Inconsistent daily updates generated stress and anxiety. | “Absolutely for me it would have been a huge improvement if it could have been somewhere within a one-hour window each day–’cause it was all over the board. Some days I would call in at 10:00, not get called back till like 2:00. I’d have 20 texts going, what’s going on for the daily update? And I’m like, no, guys, I don’t know yet.” (Child, WA) “There were periods of time where I had a lot of difficulty getting through to people in the hospital to get status reports. And when someone is that sick and that touch-and-go, if you don’t hear anything for a day, it was very upsetting and very frustrating.” (Other relative, NY) |

| Theme 6. Compassionate communication coupled with humanistic acts were highly valued by distressed families. | |

| 6A. Relaying empathy and concern for the patient were extremely meaningful. | “Every single one seemed present, seemed very empathetic that I couldn’t be there, very gentle, very patient. And that helped me a lot thinking that they were caring for her when I couldn’t be there.” (Child, WA) “I felt that they were really concerned about him, his well-being. I even felt that they were concerned about me. Sometimes when they called me, it’s, wasn’t always about him. They would call to check on me to see how I’m doing.” (Spouse, CO) |

| 6B. Above and beyond acts of kindness made a big impact. | “After he passed, the doctor called me and said that he had passed and that not to worry, that he had held his hand.” (Spouse, WA) “They were also kind enough to ask to send photos, which they printed and hung up in his room so that whenever he did wake up he would be able to see faces of his loved ones… I think that was very helpful and key in his progression and getting better during that time… I had one nurse even tell me, if you want to write a letter to your dad, email it to me and I’ll read it to him.” (Child, NY) |

| Theme 7. Videoconferencing fostered a reassuring and shared experience between family members, patients, and providers. | |

| 7A. Seeing the patient via video provided significant reassurance. | “The number one thing that helped the most with stress was having a virtual FaceTime, being able to see and talk to him even though he couldn’t talk to us. The nurse would put the iPad next to his shoulder, and we would talk to him. I really think that had a lot to do with him coming out of it.” (Sibling, WA) “We were very much involved in a lot of what was going on. That helped tremendously to keep the stress level down because we didn’t have to think about what was happening or what was going on. We actually got to watch it all take place… When you can see who you’re talking to, it resonates with you much more than when it’s a telephone call.” (Sibling, CO) |

| 7B. Video calls helped families to feel like part of the care team. | “I think [video is] good. You can see face-to-face–because sometimes that emotional connection … it helps… when you’re able to see their emotions, you’re able to see how they feel regarding your loved one.” (Child, CO) “But what made it easier is the video visits, video calls and daily updates… Even when he was intubated and not responding, we still felt like we were included in his care.” (Child, WA) |

| 7C. Video calls with multiple family members allowed for additional support and family bonding. | “Even after the video visit would be done, we would stay on the video chat with each other. And all of us would talk because everybody was isolated at that time. We would all stay on the video and support each other.” (Child, WA) “We set up a multi-conference with both my daughters that don’t live here and all of us here so that we were able to sort of say goodbye. It would have been a lot harder without that. That was greatly appreciated.” (Spouse, WA) |

| Theme 8. Family members had high levels of appreciation, gratitude, and respect for providers. | |

| 8A. Many families were thankful for and confident in the care. | “Our doctors were staying on top of what the latest recommendations for the treatment were. And when he was getting really, really bad, we thought we were going to lose him, they proned him and did that every night, which actually helped him significantly get better. So I am happy with the overall care definitely because I felt like they were staying on top of the latest things to treat COVID.” (Child, WA) “I was really grateful. Before I got off the phone, I would always tell her thank you so much, and that we’re praying for y’all and y’all family. I want you to know that. And that I really appreciate the work that you’re doing. You’re risking your life to take care of another life.” (Sibling, LA) |

| 8B. Participants acknowledged the hard work and sacrifice of the healthcare workers. | “I don’t think they were eating well. I don’t think any of them slept. I mean, seriously… I can’t say enough good about the staff there. They were wonderful.” (Spouse, WA) “I can’t stop praising the medical team at that hospital. Really above and beyond.” (Other relative, WA) |

| Theme 9. Pandemic burdens weighed heavily on family members. | |

| 9A. Societal contexts and media exacerbated personal experiences. | “When we’d hear knuckleheads out there saying that this is all a hoax and made up and we’ve got my wife dying in the ICU. Looking at that kind of stuff would just make my head explode.” (Spouse, CO) “The mistake of turning the news on and watching the news. And then social media, everybody going insane. And then right in the middle of everything there just happened to start riots going on.” (Spouse, WA) |

| 9B. Rampant spread of the virus was devastating. | “And since we lost him, my neighbor was sick with it, and two people that I know have lost their husbands as well. So every time that happens, it’s revisiting all the angst and everything that comes with that.” (Spouse, WA) “There’s three other people in my family who got it too. And I just thank God that they’re all OK, and they’re doing well. It was like a triple effect.” (Child, CO) |

Definition of abbreviations: COVID = coronavirus disease; ICU = intensive care unit.

Figure 1.

Descriptive model of family stress and support derived from qualitative interviews. Family members of intensive care unit patients with COVID-19 experienced substantial stress from a variety of factors, particularly ruminating around feeling isolated (center circle) owing to lack of physical touch, guilt, and decisional conflict, and feeling unable to appropriately advocate for loved ones. These factors led to stress (red box), which was also exacerbated by clinician factors (blue box on left), including the fractured therapeutic relationship from physical distancing. Pandemic factors (blue box on right) also contributed to the stress, such as societal discourse about the pandemic. That said, there were also clinician factors that supported the family (green box), and these included the 3Cs and videoconferencing. Pandemic factors, such as the dialogue and gratitude around the healthcare workers’ sacrifice, also contributed positively and supported families’ experiences. 3Cs = contact, consistency, and compassion; COVID-19 = coronavirus.

Stress Related to Having a Critically Ill Loved One with COVID-19

Theme 1: Inpatient visitation restrictions generated deep, emotional anguish and suffering

Participants nearly universally described sadness and disappointment with the visitation restrictions. The majority described how restrictions created substantial distress arising from fears that their loved ones were feeling isolated, scared, confused, or would die alone (a sentiment expressed even by those whose loved ones survived). Families yearned for physical presence and touch as a way to show their support. They expressed guilt, helplessness, and regret over medical decisions and feared their loved ones felt abandoned. Participants noted stress from being unable to appropriately advocate for their loved ones and concern that the lack of advocacy could contribute to lesser quality care.

Theme 2: The relationship between family and clinicians was challenged by fractured trust and ineffective communication

Although some participants shared positive remarks regarding their interactions and communication with the care team (themes 6 and 7), the majority of family members felt the physical divide weakened their relationship with clinicians to some extent. Unable to visualize the daily care, families felt alienated and resented needing to take information from clinicians at face value because they couldn’t “see it for themselves.” Others overtly acknowledged distrust, pointing to concerns about racial biases, and expressed that a lack of physical presence may have impacted their loved one’s care. Goals of care conversations were often perceived as rushed. Participants felt pressured to make decisions and noted inconsistent prognostication between providers.

Theme 3: Substantial psychological symptoms and illness were common in family members after their loved one’s ICU experience

Many participants reported physical manifestations of their heightened stress response, including weight loss, insomnia, and panic attacks. Some family members described traumatic experiences and persistent triggering events, filled with disturbing thoughts or flashbacks of the enormity of the stress. Several participants sought medical care and were diagnosed with anxiety, depression, or PTSD, often prompting the need for new prescription medications, leave from work, or even psychiatric hospitalization.

Theme 4: Participants identified primarily positive coping strategies to address their distress

Family members coped by trying to maintain hope and optimism, stay busy, and maintain some normalcy in their self-care routines. Support systems included family, faith, and professional care, which for many involved counseling and medications. That said, a few participants turned to self-medicating strategies for coping, such as drugs or alcohol.

Healthcare Team Behaviors Associated with Alleviating or Increasing This Stress

Theme 5: Participants valued proactive, frequent, and consistent contact with providers

Many families were satisfied with the communication and praised the healthcare teams in their efforts to keep them informed, despite the circumstances. Family members consistently expressed that clear, detailed, daily updates from providers eased their burdens. They described clinicians who patiently answered their questions with descriptive yet easy to understand information as facilitating effective communication. They noted substantial stress and anxiety when waiting for the daily phone call and emphasized how consistent timing of phone updates would have substantially reduced their stress.

Theme 6: Compassionate communication coupled with humanistic acts were highly valued by distressed family members

Participants repeatedly praised members of the care team who manifested traits of humanistic care, including patience, empathy, and kindness. When describing effective communication, family members frequently cited these qualities. Families responded positively to empathetic comments and noted they could “hear” when a clinician was genuinely concerned about their loved one. They were particularly grateful for what they described as “above and beyond” acts of kindness by clinicians, which they described as genuinely supportive and compassionate conversations. Others were highly impacted by unique gestures, such as decorating the room with family photos and tokens, holding the patient’s hand during withdrawal of life support, and even moving a patient’s parked car to avoid towing.

Theme 7: Videoconferencing fostered a reassuring and shared experience between family members, patients, and providers

Communicating directly with their loved ones or seeing them via videoconference reduced stress for many families, as it provided information beyond merely hearing updates over the phone. Videoconferencing reassured families because they could see their loved ones’ physical and emotional states, as well as the ICU environment. This improved their reassurance in care by allowing them to draw their own conclusions, without relying solely on the words of a clinician. Families also found videoconferencing facilitated connection with the care team by “putting a face to a name” and offered a more personal and meaningful connection. Videoconferencing provided an opportunity for family togetherness, which was particularly meaningful during a time when family members were separated from each other. Approximately 20% of participants noted substantial barriers associated with videoconferencing, indicating that they preferred phone-only contact owing to the inconvenience, inefficiency, or logistical challenges associated with video calls. Others noted that the stress of seeing their loved one on life support without being present was substantial.

Contextual Features of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Theme 8: Family members had high levels of appreciation, gratitude, and respect for providers

Even amid the distress noted by family members, the majority of participants were very satisfied with and grateful for the care their loved ones received in the ICU. Family members frequently acknowledged the stress placed on healthcare workers through the pandemic, often recognizing that they were overwhelmed, and praised their hard work and sacrifice.

Theme 9: Pandemic burdens weighed heavily on family members

Societal contexts of the pandemic and its representation in the news and media exacerbated stress. Unknowns about the virus and political dialogues increased anxiety. Being ill themselves or having other family members who were sick also impacted family members’ stress.

Suggestions for Family-centered Care and Communication

Table 4 summarizes recommendations for family-engaged care through the lens of the family members. They identified three key features when asked what made for the most effective communication, features that can be summarized as “the 3Cs”: contact, consistency, and compassion.

Table 4.

Family-derived recommendations on how to incorporate the 3Cs during physical distancing: contact, consistency, and compassion

| Family-derived Recommendations | Suggestions for Implementation | |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Provide at least daily phone updates from the clinicians. | Maintain easy to access contact information in both the patient’s room and nursing stations. |

| Consider in-person visitation at least weekly. | Provide PPE for family members and disinfect conference rooms to allow for in-person family meetings. | |

| Incorporate video conferencing at least weekly (if family is interested). | Stock units with an ample supply of equipment and encourage unit staff to liberally accommodate family requests for video calls with the patient. Utilize video technology for family group gatherings. |

|

| Assess family preferences for timing, frequency, and platform related to daily updates. | Set communication expectations during the first family discussion, including preferences for video calls, involving the full care team. | |

| Improve availability of staff to field calls when family members call in at nonscheduled times. | Train unit clerks in compassionate communication and empower them to give nonmedical details whenever possible. | |

| Recognize that gaps in contact precipitate substantial stress for family members. | Stop rounds, if possible, to field a family phone call. | |

| Consistency | Create a family call schedule with a predictable time window and stick to it. | Clinician lets the family know that they will provide an update between 11:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. daily. |

| Ask support staff to contact families should a change in the daily update call be required (if the family member wishes). | If the arranged time window cannot be met, ask staff to contact family and provide a nonmedical update while they wait. | |

| Compassion | Provide personalized information whenever possible. | Describe vivid details of the patient’s room and environment. Offer to play music, messages, or television programs according to patient or family preferences. |

| Describe and show the care the patient is receiving. | Share images of the environment for family members to keep or share. Prepare family members for the potential shock of seeing their loved one on video by briefing them on the presence of lines, tubes, and equipment. Allow video conferencing during performance of care services (respiratory treatments, physical therapy, etc.). |

|

| Offer a creative means for family presence in the room. | Allow home items, messages, and photos to be sent in and shared with the patient. | |

Definition of abbreviation: PPE = personal protective equipment.

First, many advocated very strongly for hospitals to permit at least “some” in-person visitation, even if the contact was through a window, very brief, or while complying with safety precautions. One participant noted:

We are in the middle of a pandemic, but I’m just not taking that for granted by no means. But I would have if I had to come in with a full hazmat suit, and it didn’t matter what time of day or night. I just really wish I could have seen him, and he could have seen me, outside of his casket.

—Spouse, NY

Because physical contact was not possible and phone updates were required, families emphasized the importance of consistency of communication. They recommended maintaining a schedule whenever possible so that they could expect and prepare for the calls. Many noted how lack of consistency of contact contributed to their stress.

It was difficult for [the doctors] to give you a time of when they would call…some days they would call at noon and other days they would call at 3:00 p.m….your nerves get a little off when they still haven’t called and you’re waiting and stressing out over when they’re gonna call. So, if there was a possibility of controlling or getting a schedule of like, you’re gonna get called every day at 1:30 p.m…. That way you know what to expect.

—Child, NY

Although videoconferencing was often appreciated, there were also mixed opinions about the value and necessity of using videoconferencing (theme 7). Even so, many families made recommendations about how best to leverage video technology (Table 4).

It’d be good to me to actually see him…probably everybody doesn’t want that. But that would have been a nice to have an option to say, “OK, we’re going to put him on video, but be aware, he does have tubes”…that scares people.

—Sibling, CO

Finally, participants made recommendations about ways to improve communication by focusing on compassion and empathy during phone updates:

I was lucky that I was able to always talk to someone that was kind and compassionate and really took the time to consider that we were out here hurting not being able to be there.

—Child, LA

Discussion

This national, multisite observational study provides unique qualitative data that bring to light the voices of family members whose loved ones were in the ICU during the earliest days of the pandemic. Participants in our study expressed substantial harms caused by restrictive visitation, describing their experiences as agonizing and traumatic, with a profound, negative impact on their mental health, sometimes to the point of seeking medical treatment. Similar reports from smaller studies have recently emerged from France, the UK, and Buffalo, New York, suggesting that our findings are representative of trends occurring throughout the nation and perhaps the world (30–33). Our study offers a larger and more diverse sample than extant literature and provides insight into the extent of these psychological harms resulting from the visitation restrictions instituted to curtail spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Furthermore, our sample is unique as we included family members of both survivors and nonsurvivors and did not exclude based on the absence of mechanical ventilation. Finally, our study generated family-based recommendations regarding how best to communicate with families via phone or videoconferencing through the 3Cs: contact, consistency, and compassion. We discuss each of these contributions in turn.

In accordance with findings from smaller studies (30–33), our participants noted damage to the therapeutic relationship with the healthcare team, distress over their inability to engage in care or advocate for their loved ones, and fear that their absence may have reduced the quality and frequency of care. When considering the existing literature, these fears may have some merit as family absence may have detrimental effects on patient care, including delayed medication administration, decreased mobility, and increased incidence of delirium (2, 34, 35). Pandemic visitation restrictions may also lead to longer ICU stays and delay end-of-life decision making (36). Conversely, family engagement strategies, such as flexible visitation, family presence on rounds, participation in nursing care, or family care rituals have all been found to reduce psychological morbidities, including postintensive care syndrome-family (PICS-f) (2, 14, 16, 20, 21, 25, 37, 38). The distrust evident in our data warrant consideration as a detriment to the healthcare system in an already politically and racially charged healthcare environment. Therefore, the psychological, medical, and financial costs associated with visitation restrictions need to be examined as policies are revised in the event of a resurgence with new COVID variants or the next novel contagion.

Even so, when bedside presence is not possible, alternative means of communication are necessary. Although family-centered recommendations have been developed that provide theoretical frameworks for communicating with families during physical distancing (39–47), the 3Cs described here emerged directly from the voices of family members affected by the pandemic. Although many participants experienced video technology as a useful tool, it did not emerge as a marker of effective communication as frequently or with such emphasis as the 3Cs. This is in accordance with other studies revealing mixed feelings about videoconferencing (30). Although many noted that video technology helped restore the therapeutic alliance, for some, the technology was inconvenient or inefficient and even increased their stress. These findings are important because they suggest videoconferencing is not a panacea of support for all, and therefore clinicians should assess the extent to which family members wish to utilize videoconferencing and be prepared to deliver the 3Cs without it.

Furthermore, compassionate acts, such as going the extra distance to play music and messages, provide photos, and other family-centered practices, truly mattered to the physically distanced families and should be incorporated whenever possible. These small touches went a long way toward bridging the gap of physical distance between family members and their loved ones.

Importantly, particularly in the early period of the pandemic, the benefit of visitation restriction was in response to the need to preserve PPE for healthcare workers, reduce nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infections to patients, and protect healthcare workers and their families from potential infection (2, 3, 48, 49). Our data show that families understood and appreciated the reasons for visitation restriction, often prefacing their opinions about lessening restrictions by acknowledging the context of the pandemic and social circumstances surrounding the policies. That said, our data suggest the potential value of efficiently and safely incorporating families back into the care team, with reasonable safety precautions, as a way to reduce suffering and psychological morbidity.

Many medical experts and lawmakers have urged consideration of lightening visitation rules with proposed laws that forbid hospitals from unilaterally closing the ICUs to visitation during a public health emergency (2, 40–42, 44, 45, 49–56). Our findings lend credence to this growing movement by demonstrating the detrimental effect on families and the threat to their mental, and at times physical, health. Given what we now know about control and prevention of SARS-CoV-2 community spread, reasonable safety precautions such as masks, handwashing, and PPE may help mitigate viral spread, thereby allowing safe visitation (57). Policy makers should consider the profound impact that restrictive visitation has on family members’ health and future healthcare needs as more family members may struggle with postintensive care syndrome-family (23). Our findings should also be considered during COVID-19 resurgences or future public health crises.

Limitations

Our purposive sampling approach for site selection was intended to generate a diverse group of participants, and the final sample included those with geographic, racial, and ethnic diversity. However, the sample predominantly included family members from urban areas with high educational attainment and those who were English speaking. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to all family members. Furthermore, as the family member interviews were conducted 3–4 months after ICU stay, the recollection of their experiences may have been altered by recall bias. Our study was observational, so we cannot conclude with certainty that family presence would reduce distress nor examine the impact of varied communication approaches. As advances in knowledge and infrastructure evolve rapidly, the experiences of family members of patients in the ICU with COVID-19 may be different today than in the early stages of the pandemic. Finally, our conclusions about visitation policies are important to consider in the landscape of rapidly evolving contexts and infectious threats.

Conclusions

Visitation restrictions have substantial impact on the psychological health of family members of ICU patients. Improved mitigation strategies and new knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 transmission, coupled with increasing vaccine availability, may have tilted the scale toward acceptable risk in light of the substantial harms unearthed in our study. Should physical distancing be required owing to the pandemic or otherwise, the 3Cs of contact, consistency, and compassion may offer simple communication strategies (with or without videoconferencing) that could play a substantial role in clinician–family communication and minimize the distress of these burdened family members.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the following individuals for their tireless efforts in helping this study come to fruition: Melanie Ambler, Matt Baldwin, Mansoor Burhani, Jennifer Chiurco, Laura Fonseca, Mira Green, Karin Halvorson, Rachel Hammer, Joanna Heywood, May Hua, Jin Huang, Laura Johnson, Trevor Lane, Melissa Lee, Anna Rosie Levi, Keely Likosky, Tijana Milinic, Marc Moss, Sara Puckey, Jordyn Reilly, Sarah Rhoads, Renee Stapleton, and Stephanie Yu. They also thank members of the Qualitative and Mixed Methods Core at Penn State College of Medicine for assistance throughout the project, and they thank Andrew Foy for critical review of the manuscript draft.

Footnotes

Supported by Penn State College of Medicine Department of Medicine’s Innovation Award (L.J.V.S.).

Author Contributions: S.J.H., T.H.A., J.R.C., and L.J.V.S.: study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and reporting. P.W., X.W., O.T., D.L., P.A., M.H.C., and O.R.: data collection and reporting. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Weiner HS, Firn JI, Hogikyan ND, Jagsi R, Laventhal N, Marks A, et al. Hospital visitation policies during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Am J Infect Control . 2021;49:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Munshi L, Evans G, Razak F. The case for relaxing no-visitor policies in hospitals during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. CMAJ . 2021;193:E135–E137. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Valley TS, Schutz A, Nagle MT, Miles LJ, Lipman K, Ketcham SW, et al. Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;202:883–885. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1706LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siddiqi H. To suffer alone: hospital visitation policies during COVID-19. J Hosp Med . 2020;15:694–695. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abad C, Fearday A, Safdar N. Adverse effects of isolation in hospitalised patients: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect . 2010;76:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy NR, Steinberg A, Arnold RM, Doshi AA, White DB, DeLair W, et al. Perspectives on telephone and video communication in the intensive care unit during COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2021;18:838–847. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-729OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piscitello GM, Fukushima CM, Saulitis AK, Tian KT, Hwang J, Gupta S, et al. Family meetings in the intensive care unit during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care . 2021;38:305–312. doi: 10.1177/1049909120973431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med . 2000;28:3044–3049. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med . 2003;29:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, Zatzick D, Nielsen EL, Downey L, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest . 2010;137:280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. FAMIREA Study Group Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, et al. French FAMIREA Group Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med . 2001;29:1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, Joly LM, Chevret S, Adrie C, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med . 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosa RG, Falavigna M, da Silva DB, Sganzerla D, Santos MMS, Kochhann R, et al. ICU Visits Study Group Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet) Effect of flexible family visitation on delirium among patients in the intensive care unit: the ICU visits randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2019;322:216–228. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amass TH, Villa G, OMahony S, Badger JM, McFadden R, Walsh T, et al. Family care rituals in the ICU to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in family members-a multicenter, multinational, before-and-after intervention trial. Crit Care Med . 2020;48:176–184. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE, Jr, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA . 2004;291:1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tonelli MR, Misak CJ. Compromised autonomy and the seriously ill patient. Chest . 2010;137:926–931. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stevens RD, Nyquist PA. Types of brain dysfunction in critical illness. Neurol Clin . 2008;26:469–486, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med . 2017;45:103–128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kynoch K, Chang A, Coyer F, McArdle A. The effectiveness of interventions to meet family needs of critically ill patients in an adult intensive care unit: a systematic review update. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports . 2016;14:181–234. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacobowski NL, Girard TD, Mulder JA, Ely EW. Communication in critical care: family rounds in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care . 2010;19:421–430. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amass T, Van Scoy LJ, Hua M, Ambler M, Armstrong P, Baldwin MR, et al. Psychological symptoms in family members of patients admitted to the ICU with COVID-19, a multicenter, prospective cohort study [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;203:A1497. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hosey MM, Leoutsakos JS, Li X, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Parker AM, et al. Screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in ARDS survivors: validation of the Impact of Event Scale-6 (IES-6) Crit Care . 2019;23:276. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, Gold J, Ciechanowski PS, Shannon SE, et al. Randomized trial of communication facilitators to reduce family distress and intensity of end-of-life care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016;193:154–162. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0900OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2016;316:51–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guba EG, Lincoln YS.Denzin NK. Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research; London: Sage: 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res . 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl . 1965;12:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen C, Wittenberg E, Sullivan SS, Lorenz RA, Chang YP. The experiences of family members of ventilated COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care . 2021;38:869–876. doi: 10.1177/10499091211006914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kentish-Barnes N, Degos P, Viau C, Pochard F, Azoulay E. “It was a nightmare until I saw my wife”: the importance of family presence for patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in the ICU. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:792–794. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kentish-Barnes N, Cohen-Solal Z, Morin L, Souppart V, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Lived experiences of family members of patients with severe COVID-19 who died in intensive care units in France. JAMA Netw Open . 2021;4:e2113355. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hanna JR, Rapa E, Dalton LJ, Hughes R, McGlinchey T, Bennett KM, et al. A qualitative study of bereaved relatives’ end of life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med . 2021;35:843–851. doi: 10.1177/02692163211004210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nassar Junior AP, Besen BAMP, Robinson CC, Falavigna M, Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Flexible versus restrictive visiting policies in ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med . 2018;46:1175–1180. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zeh RD, Santry HP, Monsour C, Sumski AA, Bridges JFP, Tsung A, et al. Impact of visitor restriction rules on the postoperative experience of COVID-19 negative patients undergoing surgery. Surgery . 2020;168:770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Azad TDA-KM, Al-Kawaz MN, Turnbull AE, Rivera-Lara L. Coronavirus disease 2019 policy restricting family presence may have delayed end-of-life decisions for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med . 2021;49:e1037–e1039. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, Buddadhumaruk P, Pidro C, Paner C, et al. PARTNER Investigators A randomized trial of a family-support intervention in intensive care units. N Engl J Med . 2018;378:2365–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Downey L, Dotolo D, Shannon SE, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2011;183:348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flint L, Kotwal A. The new normal: key considerations for effective serious illness communication over video or telephone during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Ann Intern Med . 2020;173:486–488. doi: 10.7326/M20-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Akgün KM, Shamas TL, Feder SL, Schulman-Green D. Communication strategies to mitigate fear and suffering among COVID-19 patients isolated in the ICU and their families. Heart Lung . 2020;49:344–345. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ersek M, Smith D, Griffin H, Carpenter JG, Feder SL, Shreve ST, et al. End-of-life care in the time of COVID-19: communication matters more than ever. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2021;62:213–222.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, Courtright KR. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2020;60:e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Holstead RG, Robinson AG. Discussing serious news remotely: navigating difficult conversations during a pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract . 2020;16:363–368. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wittenberg E, Goldsmith JV, Chen C, Prince-Paul M, Johnson RR. Opportunities to improve COVID-19 provider communication resources: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns . 2021;104:438–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Back A, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills in the age of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med . 2020;172:759–760. doi: 10.7326/M20-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Azoulay É, Curtis JR, Kentish-Barnes N. Ten reasons for focusing on the care we provide for family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:230–233. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06319-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hart JL, Taylor SP. Family presence for critically ill patients during a pandemic. Chest . 2021;160:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou Q, Gao Y, Wang X, Liu R, Du P, Wang X, et al. COVID-19 Evidence and Recommendations Working Group Nosocomial infections among patients with COVID-19, SARS and MERS: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med . 2020;8:629. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/docs/default-source/itr/tools-and-resources/bt-re-integration-of-family-caregivers-as-essential-partners-covid-19-e.pdf?sfvrsn=5b3d8f3d_2 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Montauk TR, Kuhl EA. COVID-related family separation and trauma in the intensive care unit. Psychol Trauma . 2020;12:S96–S97. doi: 10.1037/tra0000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ritchey KC, Foy A, McArdel E, Gruenewald DA. Reinventing palliative care delivery in the era of COVID-19: how telemedicine can support end of life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care . 2020;37:992–997. doi: 10.1177/1049909120948235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tupper SM, Ward H, Parmar J. Family presence in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic: call to action for policy, practice, and research. Can Geriatr J . 2020;23:335–339. doi: 10.5770/cgj.23.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The General Assembly of Georgia. 2021.

- 54. Downar J, Kekewich M. Improving family access to dying patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med . 2021;9:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, Marshall S, Chamberlain C, Koffman J. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2020;60:e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mistraletti G, Giannini A, Gristina G, Malacarne P, Mazzon D, Cerutti E, et al. Why and how to open intensive care units to family visits during the pandemic. Crit Care . 2021;25:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html