Abstract

Background

Advanced renal cell carcinoma has been resistant to drug therapy of different types and new types of drug therapy are needed. Targeted agents inhibit known molecular pathways and have been tested in renal cancer for just over a decade.

Objectives

1) To provide a systematic and regularly updated review of randomized studies testing targeted agents in advanced renal cell cancer. 2) To identify the type and degree of clinical benefit of targeted agents over the prevailing standard of care.

Search methods

Period of search: January 2000 to June 2010. 1) Electronic search of CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. 2) Hand search of international cancer meeting abstracts.

Selection criteria

Randomized, controlled studies, including a targeted agent in patients with advanced renal cell cancer reporting any pre‐specified cancer outcome by allocation.

Data collection and analysis

The majority of the standardized search and data extraction was conducted independently by two investigators with subsequent resolution of differences. Handsearching, quality of life and toxicity data extraction, most of the initial analysis, and risk of bias assessment, was carried out by one investigator and verified by additional authors as required. Twenty‐five fully eligible studies tested thirteen different targeted agents in a total of 7484 patients with mostly Stage IV disease; 61% had not received prior systemic treatment. The majority of patients were good performance status (ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) 0 to 1). Most comparisons were each examined in only a single study. Risk of bias was considered low for studies that were placebo‐controlled, had a primary outcome of overall survival, or that evaluated progression by independent radiologic reviewers unaware of the intervention allocation.

Main results

Most progress has been made in patients with advanced renal cancer of the clear cell subtype, a condition with a clearly defined molecular pathology promoting angiogenesis. In systemically untreated patients, two approaches to angiogenesis inhibition have demonstrated benefit. Compared with interferon‐alfa monotherapy, oral sunitinib improved multiple outcomes including overall survival (18% risk reduction for death; median survival improved from 21.8 to 26.4 months, P = 0.049) without correction for crossover) in patients with mostly good or moderate prognosis. In the same setting, two studies have shown that the addition of biweekly intravenous bevacizumab to interferon‐alfa also improved the chance of major remission and prolonged progression‐free survival. These two bevacizumab plus interferon studies each observed improved overall survival approaching statistical significance (each study observed a 14% risk reduction for death). Additional anti‐angiogenesis agents, such as pazopanib and tivozanib, are in earlier stages of evaluation. After progression of clear cell disease on prior cytokine therapy, oral sorafenib results in a better quality of life than placebo. In patients with clear cell disease with progression on or within 6 months of first‐line targeted therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib, the targeted oral mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor everolimus resulted in prolonged disease‐free survival without detriment to quality of life. Remissions were very infrequent and no improvement in overall survival was observed in this study where the majority of placebo‐assigned patients received everolimus at disease progression. In untreated patients with unselected renal cancer histology and poor prognostic features, weekly intravenous temsirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, improved outcomes compared with interferon‐alfa (median overall survival improved from 7.3 to 10.9 months, P = 0.008). Of particular interest, an exploratory analysis observed a marked reduction in hazard for death in the non‐clear cell subgroup. Combinations of targeted agents are being evaluated, but toxicity is problematic.

Authors' conclusions

Several agents with specified molecular targets have demonstrated clinically useful benefits over interferon‐alfa, and also after either prior cytokine or initial anti‐angiogenesis therapy. More research is required to fully establish the role of targeted agents in this condition.

Plain language summary

Targeted drug therapy for advanced kidney cancer

Background

Cancer of the kidney is an important health problem with over 15,000 deaths in North America annually. Kidney cancer in adults that has spread or is too advanced for surgery is incurable and is resistant to conventional chemotherapy drugs. Drugs that affect the body's immune system have been standard care in the past two decades but have been associated with unpleasant side effects and poor results in most patients. Recent advances in understanding the molecular biology of kidney cancer have resulted in the development of drugs that target known molecular pathways (targeted therapy). This review critically examines reports of clinical trials that have directly compared the new targeted "designer" drugs with previous standard therapies for this condition, to see if these drugs could be considered an advance in care. Studies identified A systematic survey of reports published in electronically available medical journals and cancer meeting reports since 2000 identified 25 studies that looked at 13 different new drugs in a total of over 7000 patients. Patients were generally representative of those with advanced kidney cancer, with the exception of being fully ambulatory, and with no evidence of spread to the brain. Most studies were restricted to patients with renal carcinoma of the clear‐cell subtype. Over 60% of patients had not received any prior drug treatment. All patients consented to be randomly assigned to receive the test program or standard care, often with the opportunity to receive the test drug later if beneficial (this ethical approach may have reduced any differences in survival between groups). Results of studies demonstrating important benefits A. Untreated patients with advanced kidney cancers of the clear‐cell subtype 1. In patients with no prior drug therapy and most with a predicted survival of over 12 months, a drug called sunitinib was given daily by mouth for 4 weeks out of 6. Sunitinib caused more frequent major remissions (at least 50% shrinkage of cancer) than standard interferon‐alfa given by injection under the skin three times per week (major remissions in 39% of treated patients versus 8% respectively). This benefit was associated with improved average sense of well‐being and other measures of quality of life, though patient's responses may have been influenced because they knew whether they were getting the new treatment or not. Interferon caused more fatigue, whereas sunitinib caused more diarrhea, high blood pressure, and skin problems. On average, sunitinib was associated with an extra 6 months delay in the time before the cancer grew on X‐rays, and an extra 4.6 months of survival. Sunitinib has been approved for use in North America, the European Union, and elsewhere. 2. Two studies also in untreated patients, one in Europe and one in North America, observed greater anti‐cancer effect by adding bevacizumab by vein on alternate weeks to interferon‐alfa. The magnitude of the benefits was similar to those seen with sunitinib, and the combination is in use in Europe. However, this regimen is less convenient than oral sunitinib and has side‐effects associated with both interferon and bevacizumab. 3. In untreated patients with poor predicted survival, weekly intravenous temsirolimus was associated with longer survival (10.9 versus 7.3 months) and better quality of life than interferon alfa. However, remissions were uncommon. B. Patients previously treated with drug therapy

1. Following initial interferon therapy, sorafenib improved quality of life and delayed disease growth compared to placebo.

2. Following initial targeted therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib, daily oral everolimus delayed cancer growth compared to placebo but did not result in remissions or improve quality of life. Survival was similar but most placebo‐assigned patients received everolimus later, making survival interpretation difficult. C. Patients with advanced kidney cancers of the non clear‐cell subtypes

These cancers lack the primary target for sunitinib or sorafenib, consequently patients with non clear‐cell kidney cancers have been excluded from comparative studies of those and similar drugs. Temsirolimus may help some patients in this group, according to one analysis. Implications for care

About three‐quarters of patients with advanced kidney cancer have the clear‐cell subtype and the new targeted drugs can modestly improve the quantity and quality of life in this setting. Most oncologists in North America consider oral sunitinib to be the current standard of initial drug care in appropriately selected patients. Additional after‐market studies have extended these results to patients who are older or only partially ambulatory. The expense of these drugs limits their availability in some regions, an aspect beyond the scope of this review. Complete disappearance of advanced kidney cancer remains very uncommon and will be the main objective for further research.

Summary of findings

Background

*Additional reference names are marked with an asterisk to distinguish them from study names with no asterisk.

Advanced renal cell cancer has been one of the most drug‐resistant malignancies. Hormonal and cytotoxic chemotherapy agents have not been demonstrated to improve overall survival for this condition, and remissions occur at a frequency similar to that seen with no therapy (Oliver 1989*) or with placebo (Gleave 1998*). For most of the past 20 years immunotherapy has been the main focus of the search for an effective drug therapy for renal cancer, and is the subject of a companion Cochrane systematic review (Coppin 2006*). In summary, immunotherapy is associated with very modest survival benefit at best. Pretreatment prognostic factors that predict survival are useful for stratification purposes and have been determined in both the first‐line setting (Leibovich 2005*) and in previously treated patients (Motzer 2004*). There is evidence that the distribution of risk categories in clinical trials is changing to a more favourable profile (Patil 2010*). Until now, interferon‐alfa has been considered the standard comparator for first‐line therapy of advanced kidney cancer (Mickisch 2003*; Motzer 2002*), and placebo‐controlled trials have been appropriate in the second‐line setting.

There is clearly high interest in finding more effective treatment for advanced renal cell cancer. The search for specific targets for therapy goes back at least to Paul Ehrlich's "magic bullet" over a century ago. This concept has recently received an enormous boost with the knowledge explosion of molecular targets and the potential for associated therapies that are target specific and therefore might have greater efficacy with less toxicity (Sawyers 2004*). Clinical proof of concept came with the remarkable success of single agent imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia (Deiniger 2005*). In advanced solid tumours, bevacizumab has been demonstrated, if used in combination with chemotherapy, to improve survival in colorectal cancer (Hicklin 2005*).

Molecular analysis of renal cell carcinoma has shown that kidney cancer is not a homogeneous condition (Linehan 2005*; Hacker 2010*). A high proportion of sporadic clear cell renal cell cancers have biallelic abnormalities of the VHL (Von Hippel‐Lindau) tumour‐suppressor gene (Young 2009*), whereas other subtypes do not. Absence of the active VHL gene product results in unregulated activation of the hypoxia‐inducible system and accumulation of growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In future, it will be necessary to distinguish the impact of therapy on different molecularly defined tumour types but the necessary technology has not yet reached routine use. The molecular complexities of both the disease (renal cell cancer) and the treatment (targeted therapy) are resulting in a rapidly evolving and exciting phase in the history of the treatment of advanced kidney cancer. According to one reviewer (Uzzo 2003*), "an understanding of the basic biology of renal cell carcinoma is more advanced than that of any other solid malignancy". Further molecular subclassification within clear cell renal cancer may well become feasible (Kaelin 2008*).

Molecular pathways with multiple targets that are of particular interest in renal cell cancer currently fall into two major groups including angiogenesis (Rini 2005*), and intracellular signal transduction pathways (Adjei 2005*). The presence of a target may or may not translate into benefit from a targeted agent (Bergsland 2006*). Some agents have activity against multiple targets. Classic immunotherapies such as interferon‐alfa may have anti angiogenic activity but are considered as a separate class of agent (Coppin 2006*). Suitably large randomized controlled trials have a high financial and resource cost so that selection of agents for Phase III testing requires strategic decision making (Roberts 2003*). Since the new agents are not necessarily cytotoxic, it is possible that tumour shrinkage may not be a reliable indicator of drug activity (Stadler 2006*); for example, stabilization of previously progressive disease might result in extension of overall survival. Additionally, objective response of renal cell carcinoma has not hitherto been associated with subsequent regulatory approval of an agent (Goffin 2005*). Our review examines the primary and secondary endpoints used by investigators, including progression‐free survival. Additional background will be provided in the 'Results' section for individual agents tested in the studies identified by this review.

Objectives

The primary objectives of this review are to provide a systematic survey of randomized trials of targeted agents in advanced renal cancer, and to assess whether any of these agents provide better clinically relevant outcomes than other therapies for advanced renal cell cancer. An additional objective is to provide a continuously updated reference resource in this rapidly developing field.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials, except that randomized Phase I trials were excluded.

Types of participants

Adult patients with metastatic or locally inoperable renal cell carcinoma, histologically verified at presentation or relapse. Some patients with "operable" tumours but who had serious co morbidities were enrolled in these studies. Studies of mixed solid tumours were eligible only if patients with renal cell carcinoma were stratified and reported separately from other tumour types. Patients may or may not have received prior systemic therapy.

Types of interventions

Agents with known or presumed molecular targets and known or presumed anti‐angiogenesis agents must have been part of the therapeutic regimen of at least one study arm. Classic immunotherapy agents, including recombinant cytokines and their predecessors, were excluded from this definition of targeted therapy, but may have been included as part of the regimen in any study arm. Studies in which maintenance therapy by a targeted agent was the randomized variable were eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Studies reported at least one efficacy outcome by allocation arm to be eligible for inclusion. Eligible efficacy outcomes were categorical or time‐dependent. Categorical efficacy outcomes included achievement of tumour shrinkage or disease stabilization according to commonly recognized criteria. Time‐dependent outcomes included overall survival or progression‐free survival from date of randomization. Quality‐of‐life outcomes were examined where available. Adverse events were examined in studies reporting superior efficacy or decreased toxicity for the investigational arm. Studies that reported only adverse events were not eligible.

Search methods for identification of studies

See also the Cochrane Prostatic Diseases and Urologic Cancers Group search strategy.

Sources

Online databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, and EMBASE. The main search terms were: 'cancer, renal cell/' with 'randomized controlled trial(pt)' or 'random(tw)'. We have also used a comprehensive search strategy developed for a kidney cancer policy document and kindly provided by Dr Mike Shelley (NICE 2002*; Thompson Coon 2010a*).

Handsearching of abstracts in the proceedings of the periodic meetings of the American Urologic Association, ECCO ‐ the European Cancer Conference, ESMO ‐ the European Society of Medical Oncology, and ASCO ‐ the American Society of Clinical Oncology (the general meeting held annually, and the genitourinary meeting held annually since 2008).

Handsearching of the bibliography of each primary reference and of recent reviews of renal cell cancer.

Published/unpublished material: all study identification is from published resources. Where studies were identified as meeting abstracts, the presented material was included if publicly accessible on the Internet.

Period of review: January 2000 through June 2010. Language: there was no language restriction for searching. Inclusion of otherwise eligible studies depended on the availability of translation resources for the language(s) concerned. Duplicate search: databases were independently searched by two reviewers; systematic handsearching was conducted by one reviewer (CC).

Data collection and analysis

Inclusion and exclusion of studies

Abstracts of potentially relevant studies identified by the search strategy were surveyed as well as the full text where available electronically. All study reports that met basic eligibility criteria (randomized trial of drug therapy for renal cell carcinoma) were assessed for inclusion or exclusion by two reviewers independently (CC, LL). Studies were evaluated for quality using the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001*). Faulty randomization methodology was not identified. Post‐randomization patient exclusions or inappropriate statistical methods did not necessarily exclude studies if the minimum required data for our analysis was provided, but were considered in the interpretation of results.

Completeness of ascertainment of eligible studies

The clinical trials database clinicaltrials.gov (initiated 2002) was searched for all trials of kidney or renal cancer, then limited to randomized trials that were terminated, or were still active but closed to accrual and candidates for publication. Trials are herein referred to by their eight‐digit NCT number where known. This database lists protocol elements for each trial including the estimated primary completion date, defined as the final data collection date for the primary outcome measure. Also listed is the name of the sponsor (such as the co‐operative research group or sponsoring pharmaceutical company) and the principal contact (principal investigator or sponsoring company). Trials that were terminated or were active and closed for more than one year, and not identified by the search process for published studies, were deemed missing and a potential source of publication bias. This source was also used in preparing the risk of bias tables for each study. Attempted search of additional trials databases was not productive, in some cases because they are access restricted (eg EudraCT.emea.europa.edu).

Data extraction

Data from included studies were independently extracted onto a standardized form by two reviewers (LL, CC), and any discrepancies resolved by consensus. Data extraction fields for each study included: (a) patient eligibility criteria and accrual by arm for age, race, gender, performance status, prior nephrectomy, prior systemic therapy, histologic subtype, and prognostic risk distribution; (b) stratification parameters if any; (c) stated primary and secondary outcome measures; (d) sample‐size calculation; (e) detailed interventions, including criteria for discontinuing therapy and crossover to the investigational arm; (f) treatment delivery evaluation; (g) primary and secondary outcome measures by treatment allocation; (h) adverse events.

Planned comparisons (original protocol)

Individual targeted single agents versus non‐targeted therapies (including classic immunotherapies, hormone therapies, or placebo)

Non‐targeted therapies with or without a targeted agent

Individual targeted agents with or without another agent

Other comparisons

Revised comparisons

Comparisons of different dose and/or schedule of the same agent(s) to clarify the dose‐response‐toxicity relationship for further study

Comparison of targeted agent(s) with a placebo or hormonal control, to identify agents with clinical activity

Comparison of targeted agent(s) with a cytokine control, interferon‐alfa being usual first‐line standard care until approximately 2008

Comparison of targeted agents(s) with a targeted agent control, to identify a superior agent or combination of agents

Since the original version of this review in 2008, targeted agents have become common first‐line therapy for advanced clear‐cell renal cancer, and consequently the appropriate control arm for targeted trials is evolving. In the current analysis, comparisons have been based on the nature of the control arm as in our original protocol (instead of being based on indication as in the 2008 version of this review). Meta‐analyses of groups of agents were only considered if class homogeneity was convincingly demonstrated. Studies that randomized to three or more intervention arms were considered as a set of multiple two‐arm comparisons.

Statistical analysis

We anticipated analysis of four types of outcomes: categorical outcomes, such as tumour remission; single time‐dependant outcomes, such as overall survival; quality‐of‐life surveys; and toxicity tables. Of these, methods for analysis of dichotomous outcomes were fully covered by standard Cochrane Collaboration procedures (Higgins 2005*); there was no need for other measures to be converted into dichotomous outcomes. Multidimensional quality‐of‐life and toxicity outcomes were considered individually. Time‐dependent outcomes were potentially problematic. Where only a single study was available for a comparison, any standard statistical analysis, such as the log‐rank test used by the author, was accepted. For meta‐analysis of multiple studies of the same type, extraction of a dichotomous endpoint such as survival at one year from randomization could be used but was not required.

Methodologic issues arising

Outcome statistics: the author‐quoted outcome statistics were used for the individual studies, except for remissions that were entered as a dichotomous outcome. All authors used the log‐rank test and quoted P values are all two‐sided.

Multi‐arm studies: studies with more than two arms have been approached as comparisons of pairs of trial arms of interest (Atkins 2004; Hudes 2010; Yang 2003). One additional 3‐arm study randomized patients 2:1:1 to an investigational arm and to 2 control arms considered of similar efficacy (Escudier(5) 2010).

Remission rate: major remission by RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) (Therasse 2000*) or WHO (World Health Orginization) (Miller 1981*) criteria as specified by the study, divided by number of patients evaluable for this endpoint according to investigators (patients with measurable/evaluable disease).

Overall survival as an endpoint: The original intent of this review was to focus on overall survival as definitive endpoint. However, some of the recently available targeted agents described herein have proven or probable survival benefit. Consequently their use in control arm patients within studies (crossover) or before/after study participation may confound potential differences in overall survival. For this reason regulatory bodies may approve marketing of new agents on the basis of improvement in progression‐free survival (PFS). We therefore modified the original protocol to include PFS for standardized data extraction. The interpretation of survival data is discussed in several trials reports and reviews (Escudier(3) 2010; Pal 2010*).

Risk of bias tables were constructed for each study using consistent definitions extended from the general principles described in the Cochrane Handbook (for example, "patients were randomized" was not considered sufficient to qualify as low risk of bias for either the generation sequence or allocation concealment but listed as unclear).

Nomenclature for studies

Study names in this version are based on the name of the principal investigator for each study (usually the first author of related key publications), combined with the year of the most recent related publication. Where the same investigator has led more than one study, the study names include a sequential number e.g. Escudier(1), Escudier(2), etc.

Results

Description of studies

Completeness of Ascertainment

Search of the trials database clinicaltrials.gov identified 19 of the 25 included studies described below. Eight additional studies were identified, five that had been terminated before completion, and three that had been closed for over a year as of the search cutoff date (June 2010). Early termination trials included poor accrual (NCT00110344, NCT00678288), poor tolerance (NCT00491738), a Phase IV trial (NCT00352859), and a placebo‐controlled Phase III trial of bevacizumab after prior cytokine terminated for unknown reasons (NCT00061178). Further efforts failed to identify reports from three completed studies closed for over one year, these being two randomized discontinuation trials of VEGFR‐TKIs (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐tyrosine‐kinase inhibitors) cediranib (NCT00423332) and pazopanib (NCT00244764), and a comparison of standard or low dose sorafenib with placebo (NCT00606866).

Survey of Included Studies

Additionally, see 'Table 3' ('Summary of included studies'), and 'Characteristics of included studies'. Note: for consistency across studies, for each comparison 'Arm 1' is the investigational or higher dose arm, 'Arm 2' is the control or lower‐dose arm, and these designations may differ from those used by the study authors. For three‐arm studies, comparisons (A), (B), (C) refers to pairs of arms as defined in the 'Characteristics of included studies'.

1. Summary of Included studies.

| Study Name | Publication Status |

Accrual Started |

Total Patients/ Measured for ORR |

RCC Subtype CC = Clear Cell Component |

Prior Prior Systemic Therapy |

This Review "Arm 1" (investigational) |

This Review "Arm 2" (and "Arm 3" if any) |

| Atkins 2004 | Peer reviewed journal | 2000 | 111 / 111 | any | cytokine | Temsirolimus 250 mg | Temsirolimus 75 mg or Temsirolimus 25 mg (Arm 3) |

| Bhargava 2010 | Abstract+slides | 2007 | 272 / 258 | any, 83% CC | naive 54% | Tivozanib (AV‐951) | Placebo |

| Bracarda 2010 | Abstract+slides | 2006 | 101 / 101 | CC required | naive | Sorafenib + Interferon 3MUx5 | Sorafenib + Interferon 9MUx3 |

| Bukowski 2007 | Peer reviewed journal | 2004 | 104 / 103 | CC required | naive | Bevacizumab + Erlotinib | Bevacizumab |

| Ebbinghaus 2007 | Abstract+slides | 2003 | 103 / 103 | any | naive | ABT‐510 100 mg | ABT‐510 10 mg |

| Escudier(1) 2007 | Abstract; Polish Jnl | 2000 | 305 / 0 | any | cytokine | AE‐941 | Placebo |

| Escudier(2) 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2003 | 903 / 903 | CC required | cytokine | Sorafenib | Placebo |

| Escudier(3) 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2004 | 649 / 649 | CC required | naive | Bevacizumab + Interferon | Placebo + Interferon |

| Escudier(4) 2009 | Peer reviewed journal | 2005 | 189 / 170 | CC required | naive | Sorafenib | Interferon |

| Escudier(5) 2010 | Abstract+slides | 2008 | 171 / 171 | any except papillary | naive | Bevacizumab + Temsirolimus | Bevacizumab+Interferon or Sunitinib (combined for this analysis) |

| Gordon 2004 | Abstract+slides | 2000 | 342 / 342 | any | naive | Interferon + Thalidomide | Interferon |

| Hudes 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2003 | 626 / 626 | any | naive | Temsirolimus | Interferon alone or +Temsirolimus (Arm 3) |

| Jonasch 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2005 | 80 / 80 | CC required | naive | Sorafenib + Interferon | Sorafenib |

| Lee 2006 | Peer reviewed journal | 2000 | 60 / 48 | any | 10% naive | Thalidomide | Hormone |

| Madhusudan 2004 | Abstract only | 2002 | 34 / 20 | not stated | naive | Interferon + Thalidomide | Interferon |

| Motzer(1) 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2004 | 750 / 750 | CC required | naive | Sunitinib | Interferon |

| Motzer(2) 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2006 | 410 / 334 | CC required | sunitinib &/or sorafenib |

Everolimus | Placebo |

| Procopio 2010 | Abstract+slides | 2006 | 128 / 128 | any | naive | Sorafenib + Interleukin‐2 | Sorafenib |

| Ratain 2006 | Peer reviewed journal | 2002 | 65 / 0 | any | naive 16% | Sorafenib | Placebo |

| Ravaud 2008 | Peer reviewed journal | 2002 | 416 / 416 | any, CC 87% | cytokine | Lapatinib | Hormone |

| Rini 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2003 | 732 / 639 | CC required | naive | Bevacizumab + Interferon | Interferon |

| Srinivas 2005 | Peer reviewed journal | 1999 | 14 / 14 | any | naive 29% | Thalidomide 800 mg | Thalidomide 200 mg |

| Stadler 2005 | Peer reviewed journal | 2000 | 368 / 0 | any | naive 41% | Carboxyaminoimidazole | Placebo |

| Sternberg 2010 | Peer reviewed journal | 2006 | 435 / 435 | CC required | naive 54% | Pazopanib | Placebo |

| Yang 2003 | Peer reviewed journal | 1998 | 116 / 116 | CC required | IL2 93% | Bevacizumab 10 mg/kg | Bevacizumab 3 mg/kg or Placebo (Arm 3) |

As of the search cutoff date of 30 June 2010, 26 potentially eligible studies were identified and defined as randomized controlled trials, including one or more targeted drugs in patients with advanced renal cell cancer. One study was excluded because there was no reported outcome data by allocation (Escudier(6) 2009); this study of continuous daily sunitinib randomized patients to morning or evening dosing and its omission is not likely to have biased the conclusions of this review. The remaining 25 studies were found to be fully eligible for inclusion (see 'Table 3' for current publication status, year that accrual commenced, total number of patients randomized, histologic subtype, prior systemic therapy, and study treatment summary).

Since the original version of this Review (literature search 2000 to 2007), five new eligible studies were now available for analysis (Bhargava 2010; Escudier(5) 2010; Motzer(2) 2010; Procopio 2010; Rini 2010); also, a previously ineligible study (Hutson 2007*), has been updated and now eligible (Sternberg 2010), and nine of nineteen previously reviewed eligible studies have been updated so that only one study is limited to a meeting abstract with no additional material (Madhusudan 2004).

Study design was standard 2‐arm with 1:1 randomization in the majority. Three studies used a randomized discontinuation design that randomized patients with stable disease after an induction period of 3 to 4 months (Bhargava 2010; Ratain 2006; Stadler 2005). Targeted therapy, in the sense described above, is a relatively new concept. Randomized trials of targeted therapy for advanced renal cancer first commenced accrual in October 1998 (Yang 2003). Since that time, the research effort in this field has accelerated rapidly, as judged by the number of abstracts submitted for presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). In order to give a sense of the chronological development of this rapidly moving field, this report considered studies within each analytic group in the approximate order in which they began accrual.

A survey of reported outcomes is informative ('Table 4'). Major remissions (usually based on the RECIST criterion) were reported in 21 of 22 studies (not relevant in the 3 randomized discontinuation studies) and were listed as the primary or co‐primary endpoint in 5. The hard endpoint of overall survival has so far been reported in 15 of the 25 studies but was a reported primary endpoint of only 7. Progression‐free survival has become the most commonly used endpoint, justified mainly because of the use of crossover and multiple lines of therapy that makes evaluation of overall survival problematic, and because remission has been an unreliable predictor of clinical benefit. Formal quality‐of‐life data have been reported in some studies (Bukowski 2007; Escudier(2) 2010; Escudier(4) 2009; Gordon 2004; Hudes 2010; Motzer(1) 2010; Motzer(2) 2010; Sternberg 2010) and illuminate the clinical relevance of differences in remission rates or freedom from disease progression, most clearly in studies using a placebo control to reduce the risk of patient bias (Escudier(2) 2010). Most studies have reported safety data with details of toxicities encountered in each arm but this material will be selectively reviewed when it bears on study interpretation and application.

2. Outcomes reported by allocation.

| Study Name | Comparison |

Analysis Group |

Pts | ORR | PFS | OS | QOL | Other |

| Atkins 2004 | Temsirolimus (3 doses) | 1 | 111 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Bhargava 2010 | Tivozanib vs Placebo (RDT) | 2 | 272 | no | yes | no | no | 12‐week PFS |

| Bracarda 2010 | IFNa+Sorafenib (2 regimens) | 1 | 101 | yes | yes | no | no | |

| Bukowski 2007 | Bevacizumab + Erlotinib | 4 | 104 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Ebbinghaus 2007 | ABT‐510 (2 doses) | 1 | 103 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Escudier(1) 2007 | AE‐941 vs Placebo | 2 | 305 | no | no | yes | no | |

| Escudier(2) 2010 | Sorafenib vs Placebo | 2 | 903 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Escudier(3) 2010 | IFNa+Bev vs IFNa+Placebo | 2 | 649 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Escudier(4) 2009 | Sorafenib vs IFNa | 3 | 189 | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| Escudier(5) 2010 | Tem+Bev vs IFNa+Bev vs Sunit | 4 | 171 | yes | yes | no | no | 48‐week PFS |

| Gordon 2004 | IFNa + Thalidomide | 3 | 342 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Hudes 2010 | Temsirolimus vs IFNa vs both | 3,4 | 626 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Jonasch 2010 | Sorafenib + IFNa | 4 | 80 | yes | yes | yes | no | biomarker |

| Lee 2006 | Thalidomide vs Hormone | 2 | 60 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Madhusudan 2004 | IFNa + Thalidomide | 3 | 34 | yes | no | no | no | |

| Motzer(1) 2010 | Sunitinib vs IFNa | 3 | 750 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Motzer(2) 2010 | Everolimus vs Placebo | 2 | 410 | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Procopio 2010 | Sorafenib + IL2 | 4 | 128 | yes | yes | no | no | |

| Ratain 2006 | Sorafenib vs Placebo (RDT) | 2 | 65 | no | yes | no | no | |

| Ravaud 2008 | Lapatinib vs Hormone | 2 | 416 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Rini 2010 | IFNa + Bevacizumab | 3 | 732 | yes | yes | yes | no | |

| Srinivas 2005 | Thalidomide (2 doses) | 1 | 14 | yes | no | yes | no | |

| Stadler 2005 | CAI vs Placebo (RDT) | 2 | 368 | no | yes | no | no | |

| Sternberg 2010 | Pazopanib vs Placebo | 2 | 435 | yes | yes | interim | yes | |

| Yang 2003 | Bevacizumab (2 doses) vs Placebo | 1,2 | 116 | yes | yes | yes | no |

Groups 1 to 4 results: see Tables 6‐9; primary outcome(s) are in bold;

RDT = randomized discontinuation trial; pts = total patients randomized; ORR = objective remission rate; PFS = progression‐free survival; OS = overall survival; QOL = formal quality‐of‐life assessment

Patient and disease characteristics

(see table 'Characteristics of included studies')

All studies included adult men and women in approximately the ratio expected for renal cancer (2:1), and age range was broad. Patients with brain metastases were usually excluded. Most studies restricted entry to patients with ambulatory performance status, and other prognostic factors were in approximately the expected distribution, with the exception of one study specifically designed for patients with poor prognosis (Hudes 2010). The majority of patients had undergone prior nephrectomy and some studies required this. With regard to disease profile, histology was restricted to renal cancers with a clear‐cell component in most studies of anti‐angiogenic agents. In the absence of routine gene profiling of primary cancers, histologic subtype represented a practical way of selecting patients with cancers likely to have VHL gene inactivation, resulting in constitutive activity of the hypoxia‐inducible pathway, including angiogenesis promoting factors. Some studies required measurable disease: this may select for a less generalizable patient group but is otherwise unlikely to be an important study distinction because major remissions were generally infrequent and of questionable clinical relevance. Extent of disease, directly determined or as reflected by patient performance status and laboratory correlates, is the main determinant of prognosis and was frequently used for stratification purposes or during analysis. The Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) prognostic risk stratification system (Motzer 1999*; Motzer 2002*; Leibovich 2005*) is most commonly used and was based on patients treated with cytokines. A similar system is now validated in patients treated with targeted agents with the addition of elevated neutrophil or platelet counts as adverse factors (Heng 2009*). The number of involved organ sites may provide additional prognostic power and has been incorporated into systems developed at the Cleveland Clinic in the USA and by the French collaborative Groupe Francais d'Immunotherapie (Mekhail 2005*; Negrier 2005*). These variations require care in the application of study results and in making cross‐study comparisons.

The extent of prior systemic treatment was a key factor in large Phase III studies designed to establish a new standard of care. The three major categories were (a) systemically untreated, (b) second‐line after cytokine therapy, and (c) second‐line after targeted therapy. The approach taken in this review considered the validated patient population (in 'Discussion') should a new intervention be shown superior to control (in 'Results'). In some placebo‐controlled studies of new agents designed to assess activity, mixed populations of untreated and pre‐treated patients have been examined (Sternberg 2010; Bhargava 2010).

Targeted agents tested

A total of 13 targeted agents have been tested in the included studies ('Table 5'). Nine agents were considered to have anti‐angiogenic action, of special interest in renal cell cancer, especially of the clear‐cell histologic subtype. Of these anti‐angiogenic agents, five have known specific targets (bevacizumab binds extracellular VEGF; sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib and tivozanib inhibit VEGF cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases with or without additional targets), and four have undefined or putative anti‐angiogenic action (thalidomide, AE‐941, carboxyaminoimidazole CAI, ABT‐510). The VEGFR (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor) tyrosine kinase inhibitors vary somewhat in their spectrum of action against the three VEGF receptor subtypes and against additional targets (Chow 2007*). Two other agents target EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, lapatinib and erlotinib), and two inhibit mTOR (temsirolimus, everolimus). A recent review of kinase targets in RCC is available (Furge 2010*).

3. Targeted agents in Included studies.

| Generic Name | Code Name | Trade Name | Company | Route | Group | Class | Primary Target | Secondary Target(s) | Studies |

| bevacizumab | Avastin® | Genentech | iv | anti‐angiogenic | humanized monoclonal antibody | VEGF | Bukowski 2007; Escudier(3) 2010; Escudier(5) 2010; Rini 2010; Yang 2003 | ||

| sunitinib | Sutent® | Pfizer | oral | anti‐angiogenic | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | VEGF receptor | PDGFR, c‐kit, flt3 | Escudier(5) 2010; Motzer(1) 2010 | |

| sorafenib | Nexavar® | Bayer | oral | anti‐angiogenic | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | VEGF receptor | PDGFR, Raf kinase | Bracarda 2010;Escudier(2) 2010; Escudier(6) 2009; Jonasch 2010; Procopio 2010; Ratain 2006 | |

| pazopanib | GW786034 | Votrient® | GSK | oral | anti‐angiogenic | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | VEGF receptor | PDGFR, c‐kit | Sternberg 2010 |

| tivozanib | AV‐951 | Aveo | oral | anti‐angiogenic | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | VEGF receptor | Bhargava 2010 | ||

| thalidomide | Thalomid® | Celegene | oral | anti‐angiogenic | small synthetic molecule | not defined | Gordon 2004; Lee 2006; Madhusudan 2004; Srinivas 2005 | ||

| AE‐941 | Neovastat® | Aeterna | oral | anti‐angiogenic | shark cartilage derived | not defined | Escudier(1) 2007 | ||

| ABT‐510 | ‐ | Abbott | sc | anti‐angiogenic | thrombospondin‐like | not defined | Ebbinghaus 2007 | ||

| carboxyaminoimidazole | CAI | ‐ | ‐ | oral | anti‐angiogenic | small synthetic molecule | not defined | Stadler 2005 | |

| lapatinib | GW572016 | Tykerb® | GlaxoSmithKline | oral | anti‐growth factor | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | EGF receptor | Her2 | Ravaud 2008 |

| erlotinib | OSI774 | Tarceva® | Roche | oral | anti‐growth factor | tyrosine kinase inhibitor | EGF receptor | Bukowski 2007 | |

| temsirolimus | CCI‐779 | Torisel® | Wyeth | iv | mTOR inhibitor | macrolide antibiotic | mammalian target of rapamycin | Atkins 2004; Escudier(5) 2010; Hudes 2010 | |

| everolimus | RAD001 | Afinitor® | Novartis | po | mTOR inhibitor | macrolide antibiotic | mammalian target of rapamycin | Motzer(2) 2010 |

Studies listed by target and accrual order. VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; EGF = epidermal growth factor

Risk of bias in included studies

In general, the methodologic quality of studies in oncology often cannot be completely assessed by standard CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) criteria (Moher 2001*), such as the mechanism by which allocation concealment is achieved, since this level of detail is infrequently provided in published reports. To some extent it must be taken on trust that multicentre trials have unbiased central randomization procedures and data repositories. Close data monitoring is to be expected to ensure that protocol procedures are rigorously followed that will satisfy regulatory authorities. The large Phase III studies providing the most interesting results in the following analysis had independent data and safety monitoring committees and/or submitted their outcome data for blinded review by observers unaware of the treatment allocation of each patient (see tables 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Table 1'). In addition, eight studies included a placebo component. Since the first edition of this review concerning eligible studies available to the end of 2007, most included studies previously available only from preliminary meeting reports have now been fully published in peer‐reviewed journals with substantially improved level of methodologic detail.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Phase III studies of Targeted Therapy versus Standard of Care.

| Study Name | Prior Drug Therapy | Comparison | Randomization and Allocation Issues |

PBO Control |

BIA |

Remission Odds Ratio |

Progression Hazard Ratio |

Mortality Hazard Ratio |

QOL |

| Rini 2010 | none | Bevacizumab+IFN vs IFN | None | No | No | 2.28* | 0.71* | 0.86# | nr |

| Escudier(3) 2010 | none | Bevacizumab+IFN vs PBO+IFN | None | Yes | Yes | 3.11 | 0.61 | 0.86# | nr |

| Motzer(1) 2010 | none | Sunitinib vs IFN | None | No | Yes | 6.34 | 0.54 | 0.82 | * |

| Hudes 2010 | none | Temsirolimus vs IFN | None | No | Yes | ns | nr | 0.73 | * |

| Escudier(2) 2010 | cytokine | Sorafenib vs PBO | None | Yes | Yes | ns | 0.44 | ns | +ve |

| Motzer(2) 2010 | anti‐VEGFR | Everolimus vs PBO | None | Yes | Yes | ns | 0.30 | ns | ns |

Only statistically significant results are shown numerically, all favour investigational arms; ns = not statistically significant; IFN = interferon‐alfa; PBO = placebo; nr = not reported; QOL = formal quality‐of‐life evaluation; BIA = blinded imaging assessment (for response and progression). The primary outcome for each study is indicated in bold type.

Hudes 2004 restricted to patients with 3+ adverse factors, all histologies; all other studies restricted to clear‐cell subtype

*= risk of bias because the outcome was observed by investigators or patients in an open‐label study; #= consistent and significant when considered together

Another measure of study quality is study size as surrogate for power to detect differences. The number of patients per arm in ascending order was as follows: 7, 17, 30, 32, 37, 38, 40, 50, 51, 52, 64, 85, 94, 136, 152, 171, 184, 205, 208, 208, 217, 324, 366, 375, 451. Studies at or below the median of 94 patients per arm would have low power, and little can be said of negative small studies.

Risk of bias tables were constructed for each study and tabulated in 'Table 2'. In many fields, the risk of bias was unclear because of failure to provide sufficient detail. Study outcomes were considered at high risk of bias if they were open label and assessed by investigators (remission or progression) and/or by patients (toxicity or formal quality‐of‐life assessment), except that overall survival was considered reliable. A further concern was involvement of an industry sponsor in the randomization process, data management, or publication of reports, risk of bias listed as "unclear" in these circumstances. We did not find the GRADEpro software suitable for this review where the studies were mostly of different comparisons and important outcomes were time‐dependent.

Summary of findings 2. Study quality (from risk of bias tables for individual studies).

|

Allocation Sequence |

Randomization Concealment |

Blinding (objective outcomes) |

Blinding (QOL outcomes) |

Incomplete Data (objective outcomes) |

Incomplete Data (QOL outcomes) |

Selective Reporting |

Other Risks | |

| Atkins 2004 | ? | ? | X | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Bhargava 2010 | ? | ? | √ | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Bracarda 2010 | ? | ? | X | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Bukowski 2007 | ? | √ | √ | ? | √ | ? | √ | ? |

| Ebbinghaus 2007 | ? | ? | X | ? | √ | ? | ||

| Escudier(1) 2007 | ? | ? | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Escudier(2) 2010 | √ | ? | √ | ? | √ | √ | √ | ? |

| Escudier(3) 2010 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Escudier(4) 2009 | √ | ? | √ | X | ? | ? | √ | ? |

| Escudier(5) 2010 | √ | ? | X | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Gordon 2004 | √ | √ | ? | ? | ? | ? | √ | √ |

| Hudes 2010 | ? | ? | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | ? |

| Jonasch 2010 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Lee 2006 | ? | ? | X | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Madhusudan 2004 | ? | ? | X | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Motzer(1) 2010 | ? | ? | √ | X | √ | ? | √ | ? |

| Motzer(2) 2010 | ? | ? | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | ? |

| Procopio 2010 | ? | ? | X | ? | ? | ? | ||

| Ratain 2006 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Ravaud 2008 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? | ||

| Rini 2010 | √ | √ | ? | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Srinivas 2005 | ? | ? | ? | √ | ? | ? | ||

| Stadler 2005 | √ | √ | √ | ? | √ | √ | ||

| Sternberg 2010 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ? |

| Yang 2003 | √ | ? | √ | √ | √ | √ |

√ = low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias; X = high risk of bias

Effects of interventions

Approach to detailed comparisons

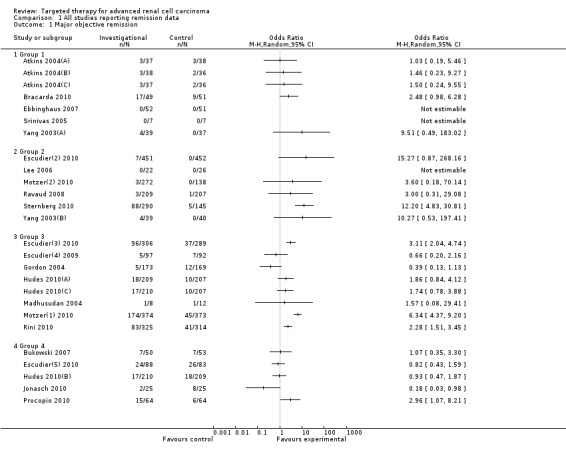

The overall intent was to be able to divide studies into meaningful groups that would easily incorporate future studies as they are reported. After consideration of alternatives, such as grouping by type of agent or by prior therapy, we have grouped studies based on the type of control used. Detailed outcome data are provided in 'Table 6' (Overall survival), 'Table 7' (Progression‐free survival), and 'Analysis 1.1' (Major objective remission rate). Summarized outcome data are provided for study Groups 1 to 4 in 'Additional tables' 6 to 9, respectively.

4. Overall survival (OS).

| Study Name | "Arm 1" Median OS | "Arm 2" Median OS | Third Arm Median OS |

Author HR (95%CI) |

Author P value | Comment |

| Atkins 2004(A) | 17.5 months | 11.0 months | 13.8 months | 0.66 | ||

| Bhargava 2010 | randomized discontinuation trial | |||||

| Bracarda 2010 | not reported | |||||

| Bukowski 2007 | 20 months | not reached | 0.16 | interim analysis | ||

| Ebbinghaus 2007 | 26.1 months | 27.8 months | 0.59 | |||

| Escudier(1) 2007 | 12.5 months | 12.4 months | 0.51 | |||

| Escudier(2) 2010 | 17.8 months | 15.2 months | 0.88 (.74‐1.04) |

0.15 | see text for secondary analysis | |

| Escudier(3) 2010 | 23.3 months | 21.3 months | 0.86 (.72‐1.04) |

0.13 (stratified) | see also Rini 2010 see text for results for cross over and reduced‐dose patients |

|

| Escudier(4) 2009 | not reported | |||||

| Escudier(5) 2010 | not reported | |||||

| Gordon 2004 | 10.8 months | 13.1 months | 0.88 | |||

| Hudes 2010(A) | 10.9 months | 7.3 months | 0.73 (.58‐.92) |

0.008 | ||

| Jonasch 2010 | 27.04 months | not reached | 1.94 .84‐4.52 2.172 .92‐5.12 |

0.1219 (univariate) 0.0764 (multivariate) |

||

| Lee 2006 | 8.2 months | 4.8 months | 0.88 (.67‐1.94) |

0.62 | ||

| Madhusudan 2004 | not reported | |||||

| Motzer(1) 2010 | 26.4 months | 21.8 months | 0.82 (.67‐1.00) |

0.049 (stratified) |

||

| Motzer(2) 2010 | 14.8 months | 14.4 months | 0.87 (.65‐1.17) |

0.18 | update from Hutson 2009 see text for x‐over analysis |

|

| Procopio 2010 | not reported | |||||

| Ratain 2006 | randomized discontinuation trial | |||||

| Ravaud 2008 | 46.9 weeks | 43.1 weeks | 0.88 (.69‐1.12) |

0.29 | see also Escudier(3) 2010 see text for EGFR 3+ subset |

|

| Rini 2010 | 18.3 months | 17.4 months | 0.86 (.73‐1.01) |

0.069 (stratified) |

||

| Srinivas 2005 | 6 months | 16 months | not available | 0.04 | 14 pts total | |

| Stadler 2005 | randomized discontinuation trial | |||||

| Sternberg 2010 | interim analysis | |||||

| Yang 2003(A) | not reported | not reported | > 0.2 |

All P values are base on the log‐rank test. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval

5. Progression‐free survival (PFS).

| Study Name | "Arm 1" median PFS | "Arm 2" median PFS | Third Arm median PFS |

Author HR (95%CI) |

Author P value | Comment |

| Atkins 2004 | 5.2 months | 6.7 months | 6.3 months | 0.93 | ||

| Bhargava 2010 | not reached | 2.1 months | 0.006 | randomized discontinuation trial | ||

| Bracarda 2010 | 8.6 months | 7.9 months | 0.049 | |||

| Bukowski 2007 | 9.9 months | 8.5 months | 0.58 | |||

| Ebbinghaus 2007 | 3.3 months | 4.2 months | 0.80 | |||

| Escudier(1) 2007 | not reported | |||||

| Escudier(2) 2010 | 5.5 months | 2.8 months | 0.44 (.35‐.55) |

<0.000001 | ||

| Escudier(3) 2010 | 10.2 months | 5.4 months | 0.61 (0.51‐0.73) |

<0.0001 stratified | ||

| Escudier(4) 2009 | 5.7 months | 5.6 months | 0.88 (.61‐1.27) |

0.50 | independent assessment | |

| Escudier(5) 2010 | 8.2 months | 16.8 months | 8.2 months | arms not compared | ||

| Gordon 2004 | 2.8 months | 2.8 months | 0.33 (stratified) | |||

| Hudes 2010(A) | 3.8 months | 1.9 months | not reported | P<0.05 based on non‐overlapping 95% CIs |

investigator assessed | |

| Jonasch 2010 | 7.56 months | 7.39 months | 0.85 (.51‐1.42) |

0.53 (univariate & multivariate) | ||

| Lee 2006 | 2.4 months | 2.8 months | 0.89 | time to failure | ||

| Madhusudan 2004 | not reported | |||||

| Motzer(1) 2010 | 11 months | 5 months | 0.54 (.45‐.64) |

<0.001 | central review | |

| Motzer(2) 2010 | 4.0 months | 1.9 months | 0.30 (.22‐.40) |

<0.0001 | central review | |

| Procopio 2010 | 8.8 months | 6.9 months | 0.22 | |||

| Ratain 2006 | 5.5 months | 1.4 months | 0.0087 | randomized discontinuation trial | ||

| Ravaud 2008 | 3.6 months | 3.6 months | 0.94 (.75‐1.18) |

0.60 | time to progression | |

| Rini 2010 | 8.5 months | 5.2 months | 0.71 (.61‐.83) |

<0.0001 | investigator assessed | |

| Srinivas 2005 | too small to analyze | |||||

| Stadler 2005 | 2.8 months | 4.2 months | 'no difference' | randomized discontinuation trial | ||

| Sternberg 2010 | 9.2 months | 4.2 months | 0.46 (.34‐.62) |

<0.0001 | ||

| Yang 2003 | 4.8 months | 3.0 months | 2.5 months | 0.39 (95%CI n/a) |

<0.001 | arm 1 vs 3 |

All P values are base on the log‐rank test. HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All studies reporting remission data, Outcome 1 Major objective remission.

Group 1: Same agents in investigational and control arms

Dose‐ and schedule‐finding studies (5 studies, 'Table 6')

Included studies/comparisons: Atkins 2004 (temsirolimus, 3 dose levels); Bracarda 2010 (sorafenib/interferon); Ebbinghaus 2007 (ABT‐510); Yang 2003(A) (bevacizumab); Srinivas 2005 (thalidomide).

This group is presented first as any differences in outcome for the same agent at different dose (or schedule) would influence the interpretation of other studies of that agent. Unlike cytotoxic agents, where the maximum tolerated dose is usually utilized, targeted agents are most rationally used at the lowest dose that reliably blocks the target. In some instances this dose may be determined in vivo as has been done for the mTOR inhibitors temsirolimus (Harding 2003*) and everolimus (Tanaka 2008*). In general an empirical approach to dose optimization is required. Except for bevacizumab dose based on body weight, targeted agents are given initially at fixed dose not adjusted for body size, then adjusted downward for toxicity if necessary. There is emerging evidence for a dose‐response relationship for the VEGFR inhibitors sunitinib (Houk 2010*) and sorafenib (Escudier(4) 2009). Dose titration to tolerance in each patient has been carried out in non‐randomized studies (Amato 2007a*; Rini 2009*) but not in the randomized studies reviewed here.

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds circulating VEGF often found in high levels in patients with clear cell renal cancer. In a three arm placebo‐controlled study, biweekly intravenous bevacizumab was tested at two dose levels: 3 mg/kg (milligrams per kilogram) and 10 mg/kg (Yang 2003). The trial was stopped after accrual of 116 patients when a planned interim analysis showed the higher dose bevacizumab arm to be superior to placebo. Cox modelling gave a time‐to‐progression ratio of 2.55 for placebo versus high dose bevacizumab (P < 0.001) but only 1.26 versus the low‐dose arm (P = 0.053). The median PFS was longer for bevacizumab 10 mg/kg than 3 mg/kg (Yang 2003(A)), at 4.8 versus 3.0 months, respectively, but the authors do not provide statistics for this comparison.

Srinivas 2005 (14 patients total) was considered too small for further consideration. One study compared two schedules of interferon along with standard sorafenib 400 mg twice daily: as such, it was of interest with regard to optimizing subcutaneous interferon dose/schedule and suggested an advantage to treating more frequently despite lower weekly dose (3 MU three times per week compared to the usual 9 MU three times per week, median PFS 8.6 versus 7.9 months, respectively (P = 0.049), and trends to higher objective response rate and reduced incidence of fatigue) (Bracarda 2010). The remaining two studies in Group 1 did not demonstrate significant differences in generally low remission rates for different doses of the same drug, in progression‐free survival, or overall survival (where reported). These studies are small with low power to detect outcome differences.

Conclusions from Group 1 Dose/Schedule Studies: 1. Bevacizumab 10 mg/kg given intravenously on alternate weeks has been validated as the dose and schedule taken forward for additional study. 2. When combined with a targeted agent, interferon may be more effective if given more frequently. 3. The additional agents tested in this group did not demonstrate efficacy differences in the evaluated outcomes (see 'Table 8'); possible reasons for this lack of difference include low study power, lack of efficacy, or lack of a dose‐response relation between the doses tested. ABT‐510 has not been further evaluated. Temsirolimus, despite low remission rates across a 10‐fold dose range, has subsequently shown efficacy at the lowest dose utilized here (Hudes 2010, see 'Group 3' below).

6. Group 1 outcomes summary: dose/schedule studies.

| Agent | Study | ORR | PFS | OS |

| Bevacizumab 10 vs 3 mg/kg | Yang 2003(A) | ns | +ve | ns |

| Thalidomide high vs low dose | Srinivas 2005 | ns | ‐ve* | |

| Temsirolimus (3 dose levels) |

Atkins 2004 | ns | ns | ns |

| ABT‐510 100 vs 10 mg | Ebbinghaus 2007 | ns | ns | ns |

| Sorafenib/IFN (2 schedules) | Bracarda 2010 | ns | +ve |

ns = not statistically different; +ve = statistically favours investigational arm; ‐ve = statistically favours control arm

* very small study suggesting detrimental effect of high dose thalidomide

Group 2: Targeted agent versus inert control

(10 studies, 'Table 9')

7. Group 2 Outcomes Summary: Targeted Agent vs Placebo/Hormone Control.

| Agent | Study | ORR | PFS | OS | QOL |

| Bevacizumab | Yang 2003(B) | ns | +ve | ns | |

| CAI | Stadler 2005 | ns | |||

| AE‐941 | Escudier(1) 2007 | ns | |||

| Thalidomide | Lee 2006 | ns | ns | ns | |

| Lapatinib | Ravaud 2008 | ns | ns | ||

| Sorafenib | Ratain 2006 | +ve | |||

| Sorafenib | Escudier(2) 2010 | ns | +ve | ns | +ve* |

| Everolimus | Motzer(2) 2010 | ns | +ve | ns | ns |

| Pazopanib | Sternberg 2010 | +ve | +ve | ns | |

| Tivozanib | Bhargava 2010 | +ve |

ns = not statistically different; +ve = statistically favours investigational arm; *= placebo‐controlled

(Inert control = placebo or hormone)

Included studies/comparisons: Bhargava 2010 (tivozanib); Escudier(1) 2007 (AE‐941); Escudier(2) 2010 (sorafenib); Lee 2006 (thalidomide); Motzer(2) 2010 (everolimus); Ratain 2006 (sorafenib); Ravaud 2008 (lapatinib); Stadler 2005 (carboxyaminoimidazole); Sternberg 2010 (pazopanib); Yang 2003(B) (bevacizumab).

Nine different targeted single agents have been compared to placebo (8 studies) or hormone control (2 studies). Hormone therapy has no demonstrated objective efficacy and is considered equivalent to placebo. Additional Table 7 lists these studies in approximate accrual order with an efficacy summary. The majority of these studies have been in patients previously treated with a cytokine before this approach was displaced from first‐line by targeted therapy; two recent studies are with new VEGFR inhibitors pazopanib (Sternberg 2010) and tivozanib (Bhargava 2010). Patient selection has increasingly focused on the clear‐cell subtype of renal cancer, especially for treatment with VEGFR inhibitors. Placebo controlled trials are particularly useful for documentation of adverse effects and impact on quality‐of‐life of new agents, but do not permit reliable efficacy comparisons of different agents.

a) Randomized discontinuation trial design (3 studies)

Three studies used a randomized discontinuation trial (RDT) design intended to detect objective stabilization of disease should the agent be cytostatic rather than cytoreductive. After a 12‐to‐16 week run‐in period on the active agent, patients with stable disease were randomly assigned to placebo or to continue the active agent (responding patients continue active therapy). These RDT studies are discussed separately because this strategy is somewhat different than the classic RCT design, and may be attractive for recruitment of untreated patients in future studies since all patients begin with active drug on the open‐label initial phase.

Stadler 2005 (carboxyaminoimidazole, CAI) and Ratain 2006 (sorafenib) from the University of Chicago Medical Center successfully implemented the RDT approach. The majority of patients had received prior systemic therapy with cytokines. The outcome of interest is progression‐free survival. CAI was inactive by this criterion; Bayesian probability of greater disease stability was less than 9% (Stadler 2005). Sorafenib was superior to placebo with a median progression‐free period of 5.5 months on continuing therapy versus 1.4 months for placebo, P = 0.0087; placebo patients went back on sorafenib at progression (Ratain 2006) potentially confounding any further outcome differences. Sorafenib was further evaluated in a large placebo‐controlled study using conventional randomization discussed below (Escudier(2) 2010).

Tivozanib, a new small molecule oral inhibitor of VEGFR, has also been assessed by the RDT technique (Bhargava 2010). Tivozanib inhibits all three VEGFR kinases. In a study of 272 patients, of whom half had no prior systemic therapy, tivozanib was initially given open label for a run‐in period of 16 weeks: 25% of patients demonstrated at least 25% tumour shrinkage by independent review, 8% progressed, and the remainder were stable. One hundred eleven consenting patients with stable disease were then randomized to continue tivozanib 1.5 mg daily or to placebo. Progression‐free survival at a protocol‐specified further 12 weeks was better on continued tivozanib than on placebo (59% versus 38%, P = 0.029). The common toxicities were hypertension (54%, all grades) and dysphonia (21%). Information is not provided as to whether prior systemic therapy influenced the chance of benefit. A Phase III comparison of tivozanib with sorafenib is in progress in the first‐line setting (NCT01030783).

b) Standard randomized controlled trial design (7 studies)

Agents are presented in the approximate order that included studies commenced accrual.

Bevacizumab

In the bevacizumab dose‐finding study mentioned in 'Results' 'Group 1', progression‐free survival was significantly better for bevacizumab 10 mg/kg than for placebo, median PFS 4.8 versus 2.5 months, respectively (hazard ratio (HR) 0.39, P < 0.001) (Yang 2003(B)), but supporting clinical outcome data such as symptom improvement was not provided. The combination of bevacizumab and interferon alfa is discussed under 'Group 3' studies.

Thalidomide

Thalidomide was not beneficial compared to hormone therapy (Lee 2006) and had substantial toxicity.

AE‐941

A large placebo‐controlled study of AE‐941, a derivative of shark cartilage, did not improve the primary outcome of overall survival (Escudier(1) 2007).

Lapatinib

Lapatinib is an oral inhibitor of EGFR (ErbB1) and HER‐2 (ErbB2). Lapatinib 1250 mg daily did not improve progression‐free or overall survival compared to hormone control on an intent‐to‐treat basis (Ravaud 2008). Remissions were rare. However a pre‐planned subset analysis examined outcomes in the 56% of patients with tumours strongly overexpressing the main target for this tumour type ErbB1 (3+ by IHC), a factor that was shown in exploratory analysis to be both prognostic (adverse) and predictive for benefit. Progression‐free survival showed borderline improvement for lapatinib in this subset (HR 0.76, P = 0.06), while median overall survival was increased from 8.7 months for hormone to 10.6 months for lapatinib (HR 0.66, P = 0.012), consistent with improved survival in the ErbB1 3+ setting. The main toxicities of lapatinib were diarrhea and rash (40% and 44% respectively, all grades).

Sorafenib

Sorafenib is an oral small molecule inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase, a key locus in the angiogenesis pathway. A pivotal study of second‐line sorafenib after cytokine failure has been extensively analyzed (see Escudier(2) 2010 references). Sorafenib 400 mg twice daily doubled median progression‐free survival versus placebo (Escudier(2) 2010), 5.5 versus 2.8 months, respectively, as assessed by independent review (HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.55, P < 0.000001). Subset analysis suggested a similar PFS benefit in different subgroups, including patients over 65 years of age without greater apparent toxicity (Eisen 2008*). There may also be a reduced incidence of brain metastases, an uncommon but devastating complication of the disease (3% and 12% for sorafenib and placebo respectively, P < 0.05, Massard 2006*). Most types of severe adverse events grades 3 or 4 were more common on the sorafenib arm than placebo, including cardiac ischemia or hypertension (4% versus < 1%), diarrhea (2% versus 1%), or hand‐foot syndrome (6% versus 0%), though bone pain was more common on placebo. Grade 1 to 2 adverse events were common but their clinical impact is better evaluated by patient self‐reporting: the authors documented symptomatic improvement of sorafenib over placebo on formal quality‐of‐life assessment with validated QOL (quality of life) measures FACT‐G and FKSI (Bukowski 2007*). Skeletal muscle wasting with sorafenib has been reported and sarcopenia may be a feature of multi kinase inhibitors (Antoun 2010*).

The study was closed to accrual following a planned interim analysis because PFS was clearly better for the sorafenib arm. There was an initial trend to improved overall survival at study closure (HR 0.71, P = 0.015) but this failed to reach the prespecified boundary and has disappeared with further follow up (Escudier 2009*). There was no significant difference for the ITT (intention to treat) final overall survival analysis: median OS was 17.8 months for sorafenib versus 15.2 months for placebo (HR 0.88, P = 0.15). At study closure, surviving placebo‐assigned patients were offered crossover to sorafenib, and 48% of all placebo‐assigned patients did so. In an attempt to assess the impact of crossover on overall survival, a pre‐planned secondary survival analysis that censored placebo patients at the time of crossover observed a difference of overall survival (median 17.8 versus 14.3 months, HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.97, P = 0.029, O'Brien‐Fleming boundary P = 0.037). However, placebo‐assigned patients who were censored at crossover to sorafenib were different from those who did not cross over and were not censored, being nearly twice as likely to be ECOG 0 or low MSKCC risk at baseline, and this censoring difference might account for the observed survival difference rather than a salvage effect of crossover. In this regard, the uncensored survival trend of the interim survival analysis is more suggestive of a crossover effect but the hypothesis remains unproven.

Everolimus

Following the publication of evidence for superior outcomes with sunitinib or sorafenib over first‐line interferon alfa (discussed in 'Group 3' below), the need for a new second line of therapy became evident. Everolimus is an oral inhibitor of mTOR (see also temsirolimus below) (Coppin 2010*) and therefore has a different mechanism of action than VEGFR inhibitors with potential for non‐crossresistance. Following encouraging non‐randomized studies in this setting, everolimus was compared to placebo in 410 heavily pretreated ambulatory patients with disease progression on or within 6 months of sunitinib and/or sorafenib (Motzer(2) 2010). The primary endpoint of progression‐free survival was improved from a median 1.9 months for placebo to 4.0 months for everolimus (HR = 0.30, P < 0.0001), with an associated 2‐month delay in decline of performance status and no detriment to overall quality‐of‐life from toxicity. The probability of remaining progression‐free at 10 months on study was 25% on everolimus versus < 2% for placebo. The remission rate was very low. The main concerns with this agent are reversible immunosuppression, non‐infectious pneumonitis, and hyperglycemia. Overall survival was essentially the same in both arms and at this time there is no generally agreed method to correct for the possible impact of crossover to everolimus of most placebo‐assigned patients at disease progression (see references in Motzer(2) 2010 for examples of techniques used to correct overall survival for crossover).

Pazopanib

Pazopanib is an oral antiangiogenesis multi‐kinase inhibitor targeting VEGFR as well as c‐Kit (also known as mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (SCFR) or CD117) and PDGFR. A substantial study randomized 435 patients to pazopanib 800 mg daily or placebo in a 2:1 ratio; 54% had not received prior systemic therapy and the remainder had prior cytokine therapy (Sternberg 2010). The primary outcome of progression‐free survival was median 9.2 months for pazopanib and 4.2 months for placebo (HR = 0.46, P < 0.0001), and was significantly improved for both the cytokine pretreated and naive subpopulations as well as those with favourable or intermediate prognostic scores. In addition, the major objective remission rate was 30% with pazopanib compared to 3% on placebo (P < 0.001). Unfortunately this benefit did not translate into any improvement in formal quality‐of‐life measurement. Interim overall survival did not cross the prespecified difference threshold and final results are awaited, noting that 48% of placebo‐assigned patients crossed over to pazopanib after progression. A Phase III comparison of pazopanib with sunitinib in the first‐line setting is in progress (NCT00720941).

Conclusions from 'Group 2 placebo‐controlled studies': 1. Nonspecific antiangiogenesis agents AE‐941, thalidomide, and carboxyaminoimidazole have no demonstrated benefit over placebo in these studies. 2. All tested VEGF receptor kinase inhibitors have shown some evidence of benefit compared to placebo and have completed or are undergoing comparative evaluation against other agents in the first‐line setting as single agents (except bevacizumab used in combination with interferon alfa). 3. Lapatinib, an EGFR inhibitor, may have activity against tumours that strongly express the primary target but is not reported to be undergoing further evaluation for advanced renal cancer. 4. An oral mTOR inhibitor, everolimus, can delay disease progression compared to placebo following sunitinib and/or sorafenib failure and is a reasonable comparator for additional agents to be tested in this setting.

Group 3: First‐line targeted agent versus cytokine control

(8 comparisons, 'Table 10')

8. Group 3 Outcomes Summary: Targeted Agent vs Cytokine Control.

| Agent | Study | ORR | PFS | OS | QOL |

| Thalidomide+IFN | Gordon 2004 | ns | ns | ns | ‐ve |

| Thalidomide+IFN | Madhusudan 2004 | ns | |||

| Temsirolimus | Hudes 2010(A) | ns | +ve | +ve | +ve |

| Temsirolimus+IFN | Hudes 2010(C) | ns | ns | ns | |

| Bevacizumab+IFN | Rini 2010 | +ve | +ve | ns | |

| Bevacizumab+IFN | Escudier(3) 2010 | +ve | +ve | ns | |

| Sunitinib | Motzer(1) 2010 | +ve | +ve | +ve | +ve |

| Sorafenib | Escudier(4) 2009 | ns | ns | ns |

ns = not statistically different; +ve = statistically favours investigational arm; ‐ve = statistically favours control arm

Included studies/comparisons (all versus interferon‐alfa): Gordon 2004, Madhusudan 2004 (thalidomide + interferon); Hudes 2010(A) (temsirolimus); Hudes 2010(C) (temsirolimus + interferon); Rini 2010, Escudier(3) 2010 (bevacizumab + interferon); Motzer(1) 2010 (sunitinib); Escudier(4) 2009 (sorafenib).

Interferon‐alfa has been shown to modestly improve overall survival (see Coppin 2006*) and became an accepted standard of care suitable as a first‐line trial control arm in both the USA (Motzer 2002*) and Europe (Mickisch 2003*). This somewhat simplified the situation compared to the previous decade when high dose interleukin‐2 was approved in the USA on the basis of occasional durable remissions in the minority of patients fit enough to receive it. High dose IL‐2 has since been shown to have no impact on median overall survival compared to interferon‐alfa (McDermott 2005*). First‐line targeted studies versus interferon‐alfa provided the main focus of interest until recently when targeted agents were shown superior and became the new first‐line standard in North America and Europe. The following studies have all used the standard dose, route, and schedule of interferon‐alfa 9 MU by subcutaneous injection three times per week. In order to provide some chronological perspective, agents will be presented in the approximate order in which accrual commenced in the related randomized studies.

Thalidomide

This oral agent, withdrawn as a sedative following discovery of teratogenicity in the 1960s, has found a new indication as an anti‐cancer agent, initially for multiple myeloma. Thalidomide is a glutamide derivative that has a broad spectrum of cellular action including an anti‐angiogenic effect of interest in RCC. The drug has dose‐limiting neuropathy requiring very careful monitoring. Thalidomide has been added to first‐line interferon in two RCTs (Gordon 2004; Madhusudan 2004). The large ECOG study (Gordon 2004) escalated thalidomide dose to individual MTD (median 400 mg daily, range < 100 to 1000 mg). There was no significant difference in disease‐related endpoints but the detrimental effect of therapy on global quality‐of‐life (FACT‐G assay) was greater for the combined arm than interferon alone. The other small study, reported in abstract only, did not provide additional insight (Madhusudan 2004).

Temsirolimus

Temsirolimus is metabolized to sirolimus, a macrolide antibiotic and immunosuppressive drug also known as rapamycin and derived from a Streptomyces species. Both analogues are inhibitors of an intracellular kinase called mTOR, resulting in disruption of cell cycle progression as well as inhibition of angiogenesis. A large Phase III study has compared temsirolimus with interferon‐alfa in RCC patients with three or more of six adverse prognostic factors for survival: metastasis‐free interval from diagnosis less than one year, impaired performance status (Karnofsky 60 or 70), metastases to multiple organs, elevated LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), low hemoglobin, or high corrected serum calcium (Hudes 2010). It should be noted that this definition of adverse prognosis is slightly different from the MSKCC poor risk group, and the study included 28% patients with intermediate risk as well as patients with poor risk by MSKCC criteria (Dutcher 2007*). All histologic subtypes of renal cell cancer were eligible. The single‐agent temsirolimus arm used a dose of 25 mg IV weekly, which was the lowest dose previously tested in a dose‐finding study (Atkins 2004; see Group 1 above). Temsirolimus has diverse toxicities but at this dose, severe adverse reactions were more common in the interferon arm (78% interferon patients versus 67% temsirolimus patients experienced one or more grade 3/4 adverse events (P = 0.02). The types of adverse events were different, the main toxicity of interferon being asthenia, whereas rash, edema and stomatitis were more common with temsirolimus. Remissions were infrequent and not statistically different, though minor tumour shrinkage was more commonly seen with temsirolimus (Dutcher 2009*). Progression‐free survival, as determined by the investigators and taking into account symptomatic deterioration, was superior for temsirolimus versus interferon (median 3.8 versus 1.9 months, respectively, non‐overlapping 95% confidence intervals). On the average, the additional time progression‐free is spent without symptoms or toxicity: a Q‐TWiST (quality adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity) analysis observed that the median time without grade 3/4 treatment toxicity or recurrence was 6.5 months for temsirolimus versus 4.7 months for interferon (Zbrozek 2010*). Importantly, overall survival was improved for temsirolimus versus interferon, median 10.9 versus 7.3 months respectively, HR 0.73, 95%CI 0.58‐0.92, P = 0.008. A third trial arm randomized patients to receive the combination of interferon‐alfa plus temsirolimus 15 mg/dose; however, outcomes were not superior to interferon alone and there was greater toxicity with the combination.

An exploratory analysis of this study by histologic subtype has been published (Dutcher 2009*). Clear cell cancers constituted 82% of the total, and the overall survival for this subtype showed a trend in favour of temsirolimus over interferon although did not quite reach statistical significance (HR 0.82, P = 0.06, unstratified Cox model). Patients with cancers having non‐clear cell histology, 18% of the total population, had a statistically better survival with temsirolimus than with interferon (HR 0.49, P < 0.05). Similarly, for progression‐free survival, the benefit of temsirolimus over interferon may be greater for non‐clear cell tumours (HR 0.38) than for clear cell tumours (HR 0.76). These observations are of interest because non‐clear cell histologies have been excluded from most studies of angiogenesis inhibitors considered unlikely to be efficacious against RCC histologies that lack the VHL mutation.

Bevacizumab + Interferon