Abstract

Objectives

Medication adherence is critical in the successful management of lupus. There is very limited existing literature on reasons why non-adherence is not reported. This study explores the impact of current and previous medical experiences on patient satisfaction, adherence and reporting of non-adherence.

Methods

Mixed methodology involved thematic analysis of in-depth interviews (n = 23) to further explore the statistically analysed quantitative survey findings (n = 186).

Results

This study identified five themes: (i) physician-patient discordance and a ‘hierarchy of evidence’ in medication decisions; (ii) the association of adherence with satisfaction with care; (iii) the persisting impact of past adverse medical experiences (AMEs); (iv) the dynamic balance of patient-physician control; and (v) holistic care, beyond a purely medication-based focus. Improving quality of life (43% of participants) and a supportive medical relationship (24%) were the main reasons for adherence. Patient-priorities and self-reported symptoms were perceived as less important to physicians than organ-protection and blood results. Non-reporters of non-adherence, non-adherers and those with past AMEs (e.g. psychosomatic misdiagnoses) had statistically significant lower satisfaction with care. The importance of listening to patients was a key component of every theme, and associated with patient satisfaction and adherence. The mean rating for rheumatologist’s listening skills was 2.88 for non-adherers compared with 3.53 for other participants (mean difference 0.65, P = 0.003).

Conclusion

Patients would like more weight and discussion given to self-reported symptoms and quality of life in medication decisions. Greater understanding and interventions are required to alleviate the persisting impact of past AMEs on some patients’ wellbeing, behaviour and current medical relationships.

Keywords: SLE, rheumatology, medication adherence, patient behaviour, patient–physician interactions

Rheumatology key messages.

Many systemic lupus erythematosus/systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease patients prioritize current symptom improvement and quality of life over long-term considerations for medication decisions.

Non-adherers and non-reporters of non-adherence gave significantly lower ratings for physician listening skills.

Adverse medical experiences, particularly disbelief, psychosomatic misdiagnoses and long diagnostic journeys can reduce longer-term patient satisfaction.

Introduction

Medication adherence can improve outcomes and reduce costs to health services [1]. It is of particular importance for SLE and other systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease (SARD) patients as these diseases remain incurable, necessitating lifelong medications in those with moderate and severe disease [2]. The timely use of appropriate medications in SLE/SARDs can prevent or slow disease progression [3, 4]. Adverse drug reactions are more common in SLE patients [5], are often exacerbated by multimorbidity and polypharmacy and can also reduce adherence [6, 7]. Medication non-adherence is difficult to accurately quantify, with rates of 3% to 80% previously reported in SLE patients [8–11].

There are multiple models [12–14] relating to adherence and medical interactions, which provide insights into patient beliefs and behaviours. Although the importance of the medical relationship in promoting adherence has been researched, including in SLE [8], the enduring impact of past medical interactions has not been explored in depth.

We have used the concept of ‘adverse medical experiences’ (AMEs) to encompass past experiences that we identified in our previous research [15, 16] as having persisting negative psychological impacts. AMEs include repeated physician dismissal and disbelief of patient-reported symptoms and/or a feeling of being endangered by many physicians lacking the necessary knowledge to assist with these potentially life-threatening diseases. We hypothesized that these AMEs may also negatively impact medical relationships and medication adherence. We also explored the (greatly under-researched) question of why patients do not inform their doctors when they have been non-adherent. Previous studies showed that some SLE patients were not open about non-adherence, even when measurements of serum concentrations of HCQ and MMF definitively demonstrated their non-adherence [9–11].

We sought to gain insights into how clinician behaviour can positively or negatively influence patient behaviour in order to improve medical relationships, adherence and potentially reduce under or over-treatment.

Methods

Data collection

Inclusion criteria: age ≥18 years; reporting a diagnosis of lupus, undifferentiated connective tissue disease, mixed connective tissue disease, Sjögrens, or overlap condition on their clinic letters.

Ethical approval was obtained through the Cambridge Psychology Research Committee, and all respondents gave informed written (electronic) consent.

A questionnaire was made available online in December 2019, using Qualtrics, to LUPUS UK forum members and an online Facebook lupus support group. Questions elicited quantitative (rated from 1–5), and qualitative responses, and included: perceptions of medical support, reasons for adherence, non-adherence and non-reporting of non-adherence. Interviewees were purposively selected from the questionnaires to ensure a range of socioeconomic and disease characteristics, (including age, gender and severity of disease) adherence behaviours and views of medical support. The interview schedule was semi-structured and explored views of the relationship between satisfaction with care and adherence. M.S., an experienced, qualitatively trained researcher conducted the interviews. They continued until thematic saturation was reached (no novel insights arising from subsequent interviews). Interviews lasted for ≈1 h and were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS v.26, using comparison of means (t-tests) and Spearman’s rank correlations. Thematic analysis [17] was used for the interviews and qualitative data from the surveys to further explain quantitative findings. M.S. coded data using NVivo12, after immersion in the transcripts. R.H. double coded 25% of interviews, and E.L. reviewed all interview extracts, to enhance agreement and reliability. Themes were discussed and agreed by the wider team, including five patient representatives. Validity was strengthened by considering deviant cases [18], member checking [19] and triangulating quantitative and qualitative results. Detailed methods, the criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [20], and the questionnaire are included in the supplementary material, available at Rheumatology online.

Results

Survey respondents were predominantly from the UK, white and female (>92%), and 83% had SLE (Table 1). The most prescribed medication among the 186 survey respondents was HCQ, with 69% currently taking. Self-reported adherence rates (by asking if they always take/took as prescribed) were ascertained for each medication and ranged from 71% for HCQ to 86% for oral steroids. Reasons elicited for adherence and non-adherence were for any of their SLE/SARD-specific medications. Any percentages quoted within the text refer to survey data.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (survey: n = 186; interview: n = 23)

| Characteristic | Number (survey, n = 186) | % (survey) | Number (interview, n = 23) | % (interview) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age band (years) | ||||

| 18–29 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| 30–39 | 27 | 15 | 1 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 53 | 28 | 7 | 30 |

| 50–59 | 52 | 28 | 7 | 30 |

| 60–69 | 28 | 15 | 4 | 17 |

| 70+ | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| SLE | 155 | 83 | 19 | 83 |

| UCTD/unspecified CTD | 12 | 6 | 4 | 17 |

| Sjögrens | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| MCTD | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cutaneous/discoid lupus | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Overlap | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Current main medicationsa | ||||

| HCQ | 128 | 69 | 14 | 61 |

| Oral steroids | 61 | 33 | 13 | 57 |

| Steroid injections | 43 | 23 | 6 | 26 |

| MMF | 28 | 15 | 4 | 17 |

| MTX | 27 | 15 | 3 | 13 |

| AZA | 19 | 10 | 4 | 17 |

| Biologic | 12 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| CYC | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequency of reporting non-adherence to their doctor | ||||

| Always | 78 | 53 | 10 | 59 |

| Usually | 19 | 13 | 2 | 12 |

| Sometimes | 15 | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| Occasionally | 10 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Never | 26 | 18 | 3 | 18 |

| Missing | 38 | 5 | ||

| Delays to diagnosis | ||||

| <1 year | 40 | 25 | 3 | 14 |

| 1–2 years | 23 | 14 | 4 | 18 |

| 3–5 years | 22 | 14 | 1 | 5 |

| 6–9 years | 18 | 11 | 6 | 27 |

| 10+ years | 57 | 36 | 8 | 36 |

| Missing/unsure or non-quantitative response given | 26 | 1 |

Infusions/injections were classified as ‘current’ if they were within the previous 12 months. MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; UCTD: undifferentiated connective tissue disease.

Themes

Five main themes were identified: (i) physician–patient discordance and a ‘hierarchy of evidence’ in medication decisions; (ii) association of adherence with satisfaction with care; (iii) the persisting impact of past adverse medical experiences (AMEs); (iv) the dynamic balance of patient-physician control; and (v) holistic care, beyond a purely medication-based focus.

Theme 1: physician–patient discordance and a ‘hierarchy of evidence’

They just tend to treat what they think you have rather than what you tell them that you’ve got (Ppt Q, Male, 70 s)

Many patients perceived that physicians prioritized blood results and their judgement over patient-reported symptoms and priorities. Examples of how this was considered to create a ‘hierarchy of evidence’ and generated barriers to being prescribed and/or adhering to an optimal medication regimen included the following.

Discordance between patient and physician priorities: While physicians were perceived to be focused on preventing organ damage and death, less than 10% of respondents cited these long-term impacts as reasons for adherence. As Fig. 1 shows, far more (43%) gave improving their immediate QoL/reducing symptoms as a reason for adherence:

I just want to maximise my quality of life now … I don't want [my children] to remember me being ill all the time and in bed constantly. (Ppt 94, Female, 40s)

Diagnostic delays/misdiagnoses: The lack of definitive diagnostic tests combined with the frequent dismissal of early patient-reported symptoms was felt to have led to misdiagnoses that delayed the correct diagnosis and relevant treatment (approx. 50% took >5 years to diagnosis). Patients reported enduring physical and psychological damage as a consequence (Table 2, quote 1).

Difficulties accepting disease and medications: The initial physician and societal disbelief of the often ‘invisible’ symptoms could increase post-diagnosis self-doubt and delays in accepting the disease and medications (Table 2, quote 2).

Insufficiently accurate tests for diagnosis and monitoring: Blood tests were reported to often not correspond with how unwell participants felt yet were required as ‘evidence’ for treatment initiation/continuation by some clinicians. This reliance on blood markers over patient-reported symptoms affected those at both extremes of the serological spectrum, leading to perceptions of under- and over-treatment (Table 2, quotes 3a,b,c).

Limited availability of evidence-based medications: Limited medication options and high costs were sometimes reported to have been given as reasons for not prescribing medications:

I said about the mycophenolate. ‘I’m not prescribing an expensive drug like that’ she [rheumatologist] said’ (Ppt L, Female, 30s)

Fig. 1.

Main reasons given for adherence, non-adherence and non-reporting

Figure 1 depicts the main reasons given by participants for medication adherence (a), non-adherence (b) and non-reporting of non-adherence to clinicians (c). Note: These graphs were generated from responses to open-ended questions, e.g. ‘Please give any reasons for taking your medication as prescribed’. Some participants gave more than one reason. QoL: quality of life.

Table 2.

Barriers to being prescribed and/or taking appropriate medication

| Barriers | Illustrative patient quotes |

|---|---|

|

Very angry that I had been told it wasn’t lupus all those years ago and that the rheumatologist diagnosed me within minutes … It ruined decades of my life and has had a lasting impact … also lost 6 babies … which I believe could have been prevented if I had been diagnosed and on treatment. (Ppt R, Female, 40s) |

|

They kept banging on take steroids, take steroids … I refused for a very long time … Because as a lupus patient, on the whole, you look fine, you know? … you don’t have anything that people can see … I guess I doubted myself. Am I making this up? Is it in my head? (Ppt N, Female, 50s) |

|

|

Theme 2: association of adherence with satisfaction with care

Supportive and empathetic … always makes time to listen (Ppt F, Female, 40s)

Support, trust and feeling ‘cared about’

Almost a quarter (Fig. 1a) of participants reported adhering due to a supportive medical relationship:

I respect my rheumatologist, he’s knowledgeable, up to date and I believe he has my best interests at heart (ppt 62, Female, 50s).

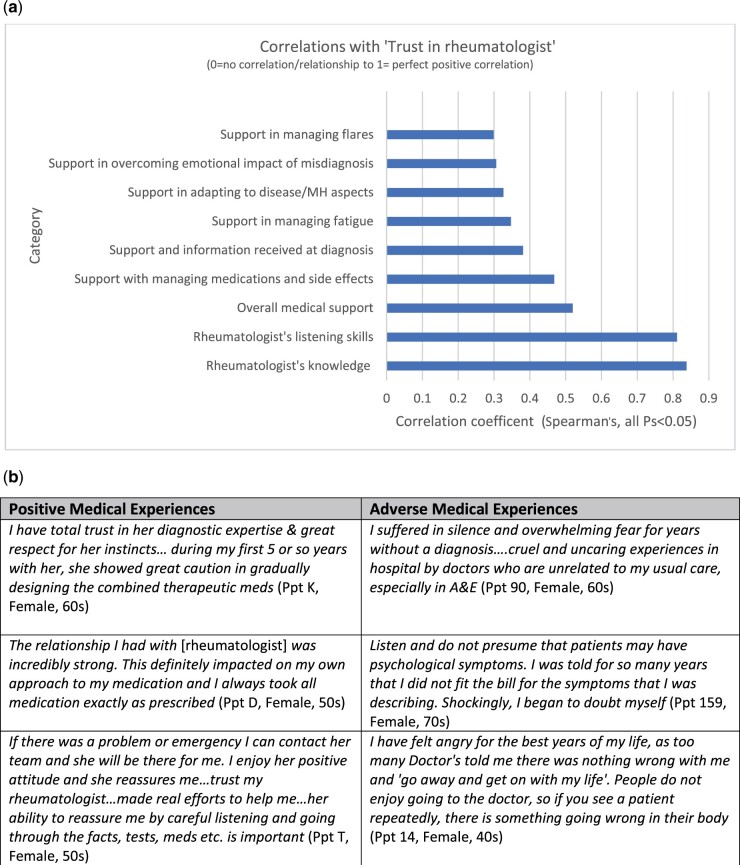

Trust in doctors was multi-faceted and discussed in interviews as being influenced by physicians listening, believing patient symptoms, being accessible in an emergency, sharing information, and showing that they care. Trust was correlated with multiple other measures of patient satisfaction with care (Fig. 2), and highly correlated with ratings of physicians’ listening and knowledge (rs >0.8).

Fig. 2.

Trust in doctors and medical support

(a) graphical presentation of correlations between ‘trust in rheumatologist’ with other patient-reported measures of support and satisfaction with care. (b) Physician behaviours influencing patient wellbeing and trust; contains patient quotes relating to positive and adverse medical experiences that have altered trust.

Feeling ‘cared about’ by their clinicians was extremely important to patients, and reported by many to improve their adherence, while perceptions of uncaring, inattentive doctors were reported to have led to reduced adherence to medications and advice:

I feel that she [rheumatologist] doesn’t care about me and so I no longer care about my lupus treatment and medication either. The result is that I am a lot more patchy in taking my meds. (Ppt D, Female, 50s)

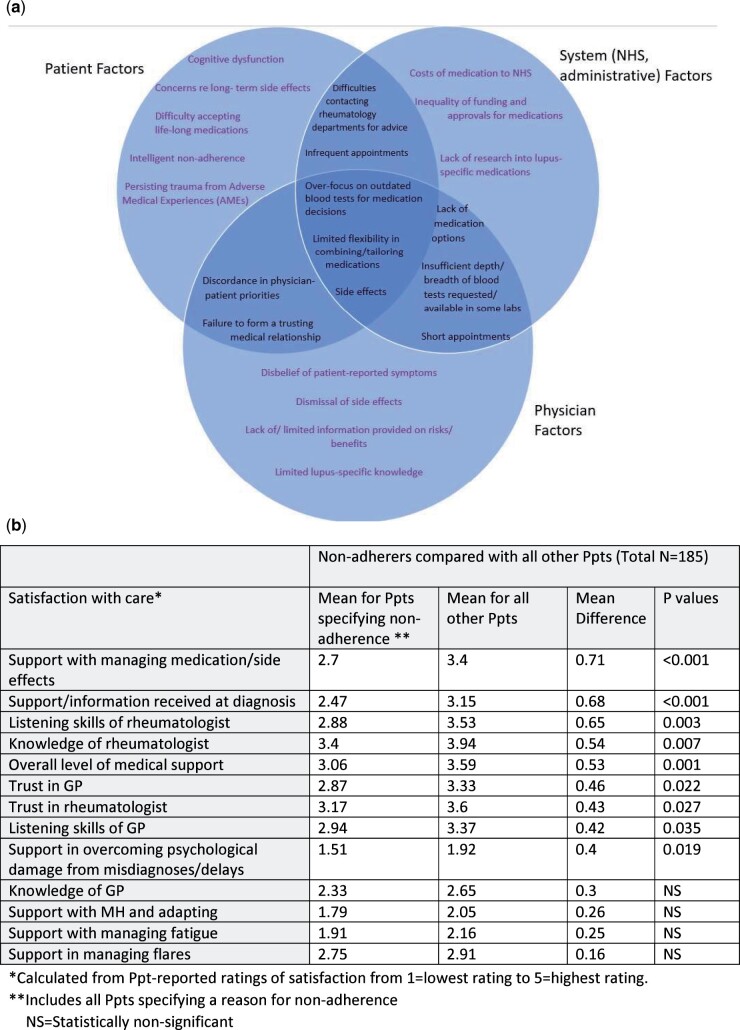

Although only a minority directly reported on the survey that a negative or unsupportive medical relationship was the cause of non-adherence (14%, Fig. 1b), interviews revealed that non-adherence involved complex inter-linked relationships between patient, system and physician factors (Fig. 3a). Most participants reported adhering in order to improve their condition, regardless of the quality of the medical relationship. Non-adherers had significantly lower levels of satisfaction with care in most domains (Fig. 3b). For example, the mean rating for listening skills of rheumatologist was 2.88 for non-adherers compared with 3.53 for other participants (mean difference (MD), 0.65, P = 0.003).

Fig. 3.

Inter-linking factors contributing to non-adherence and/or poor satisfaction with care and comparison (t test) of satisfaction with care ratings between non-adherers and other Ppts

(a) shows inter-linking factors contributing to non-adherence and/or poor satisfaction with care. (b) statistically compares (t-test) mean satisfaction with care between those reporting non-adherence and other participants. *Calculated from Ppt-reported ratings of satisfaction from 1 = lowest rating to 5 = highest rating. **Includes all Ppts specifying a reason for non-adherence. *** N: Statistically non-significant.

Communication and information sharing

Poor physician communication about medication risks/benefits, insufficient monitoring and not sharing test results were widely reported, and contributed to non-adherence:

My appointments kept getting cancelled and I just stopped taking the meds, I thought I was falling through the cracks, my bloods weren’t getting done, no-one was telling me the results (Ppt A, Female, teens)

This contrasted with other participants who reported feeling informed and reassured by being given sufficient information on a new medication and the opportunity for discussion:

She [lupus nurse] was brilliant, she started me on [DMARD] and she went through absolutely everything with it … a leaflet, when to take it, these are the risks, the benefits … a time frame. (Ppt P, Male, 40s)

Clinician impact on side effects and non-intentional non-adherence

Although less explicitly identified by participants, non-adherence due to cognitive dysfunction and side effects could be reduced by clinicians’ being supportive, non-judgemental, encouraging discussion and offering advice.

Reports of non-intentional non-adherence were almost wholly related to cognitive difficulties (35% giving as a reason for non-adherence). Embarrassment was often expressed about memory problems, which reduced the likelihood of reporting their difficulties and accessing support:

Embarrassingly as I’m a nurse I regularly mis-dose myself, either forget or overdose due to my memory problems. I still struggle with the idea of a Dosette box as I don’t feel old (Ppt R, Female, 40s)

Discussions revealed that physicians could also reduce non-adherence arising from side effects (which 44% gave as a reason for non-adherence). Many participants reported an unsympathetic response to reports of side effects, leading to patient–physician conflict and non-adherence:

I refused to take the medication that I was allergic to … Well it’s your fault you’re in pain because you won’t take the tablets … she [rheumatologist] said … didn’t even listen … her own agenda (Ppt N, Female, 50s)

Impact of medical relationships on openness in reporting non-adherence

Only 53% of respondents reported always informing their physician if they did not take their medication as prescribed. An unsupportive or insecure medical relationship, including difficulty in accessing support or fear of disapproval, was reported by over 50% of those specifying a reason for non-reporting:

But I only see [rheumatologist] every 6 months and I've given up trying to talk to my GP … not seen them in 3 years … so I'm on my own (Ppt 4, Female, 40s)

Those not informing physicians about non-adherence (excluding the 33% who gave the reason it was too infrequent to mention) had a statistically significantly lower satisfaction with care in every domain (minimum P = 0.05), with the exception of support with fatigue and mental health (MH). The difference was particularly pronounced in ratings of listening skills for GPs (non-reporters = 2.5, all other participants = 3.3, MD = 0.8, P = 0.016) and rheumatologists (non-reporters = 2.6 vs 3.3, MD = 0.7, P = 0.032). This was explored further in interviews where multiple participants discussed how their diagnostic difficulties and perceptions of poor physician listening skills led to non-adherence and/or non-reporting of non-adherence:

Sometimes I feel it is pointless being honest as doctors never seem to listen properly and believe they know best rather than listening to suggestions and how I feel … Doctors don’t seem to care. (Ppt B, Female, 20s)

Conversely, physicians who had built up trust by being available and listening attentively were felt to improve openness in reporting difficulties, including with medication:

We have a good relationship and he [GP] has an idea of who I am as a person and my health … even the little things … I generally feel I can be very open with him (Ppt J, Male, 20s)

Theme 3: the persisting impact of past AMEs

‘ Literally terrified … no confidence whatsoever’ (Ppt S, Female, 30s)

Although the majority of interviewees reported current secure medical relationships, past ‘adverse medical experiences’ (AMEs) were found to have a persisting impact on medical security, psychological wellbeing, trust (Fig. 2b, column 2) and satisfaction with care, including in support in managing medications/side effects.

We defined AMEs as stressful healthcare-related experiences, including long diagnostic journeys (>1 year) and previous MH or medically unexplained or ‘in your head’ type misdiagnosis (MH/MUS), which were commonly reported to have had persisting negative psychological impacts.

AMEs and satisfaction with care

Those whose diagnosis was delayed (using >1 year of symptom onset) gave statistically significantly lower ratings in many areas of support, including: support received at diagnosis (2.7 vs 3.18 for those diagnosed <1 year, MD = 0.48, P = 0.031), support with managing flares (2.72 vs 3.31, MD = 0.6, P = 0.018) and support in overcoming psychological impact of delays/misdiagnoses (1.58 vs 2.13, MD = 0.54, P = 0.019). The MH/MUS misdiagnosed gave significantly lower ratings for GPs’ listening and knowledge (both Ps 0.037), likely because they were the physicians most frequently misdiagnosing early SARD symptoms.

AMEs and adherence

There was no significant difference in adherence for AMEs categories despite lower satisfaction with care. However, when looked at individually, some of the most traumatized by multiple AMEs, were either highly avoidant:

I don’t go to doctors or hospitals if I can avoid it, I’ve lost too much and feel scared what will happen when I do (Ppt 95, Female, 50s)

or highly adherent:

I scored very high in the PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] scale [from multiple AMEs] … spent too much of my life just plain fighting to give in now … so I never take less than prescribed … greedily take whatever treatment I can get (Ppt V, Female, 50s)

Theme 4: the dynamic balance of physician–patient level of control of medications

My body, my life, my illness (Ppt H, Male, 60s)

Preferences for degree of control over medication decisions varied between participants. The vast majority preferred a fully-informed collaborative approach, and felt it improved acceptance and adherence:

Looked at all the pros and cons of a medication … before a final decision was reached. It felt like a kind of joint brainstorming session and it meant that I felt entirely on board with the result (Ppt T, Female, 50s)

Many participants also strongly felt that they should be given more input into medication decisions in order to improve, often very poor, QoL:

Surely the balance of risk should be discussed and assessed by both, and patients allowed an informed opinion as to an acceptable level of risk … I'd risk a lot, almost anything, because this is no life … few years of goodish life would be worth so much more than endless risk-free sofa years (Ppt E, Female, 60s)

‘Intelligent’ non-adherence

Medical insecurity was frequently indicated to have resulted from doctors having insufficient knowledge of lupus (only 16% of participants rated GPs as having good/very good knowledge of lupus). Patients therefore reported having to acquire knowledge and advocate for themselves:

I brought up that I needed an eye test, because I’ve been on Hydroxychloroquine for a long time, and [GP] was like, ‘Well, I’ve not heard of that, did you read it on the internet?’ … they’re out of their depth (Ppt M, Female, 50s)

Some participants reported taking control and being ‘intelligently’ non-adherent for their own safety:

I have no trust at all, particularly when I felt an interaction between HCQ and a GP-prescribed medication but my GP dismissed it as all in my head … I found there is a potent interaction in some patients that can cause heart standstill … won’t be taking any medication on doctors’ advice alone (Ppt G, Female, 50s)

Several patients discussed altering their dose themselves to improve QoL by balancing benefits with reducing side effects:

Well, if I’m going to only have another five years to go … I need quality of life … so I actually increased my steroids … certainly made me a bit better … I just do it (Ppt Q, Male, 70s)

More physician direction/information required at times

Many patients reported being given very little information, were often just handed leaflets, and felt anxious and confused about the lack of physician direction in medication decisions, often then seeking online advice from medically unqualified peers:

I find it really difficult that doctors do not give you their opinion any more. I appreciate the free choice but it is difficult to know what to do for the best … It seems like a pretty heavy duty drug [AZA] to take if I don’t really need it … would I be better off waiting until things get worse? Am I doing myself harm by not taking it? (Forum post, Female)

Some participants preferred physicians taking a more decisive or directive approach at times, especially when severely unwell. This could increase security and was reported to improve adherence, especially within a trusting relationship. A very firm response from a trusted clinician to non-adherence was also felt by some participants to ensure future adherence:

She very clearly, concisely and firmly told me ‘never ever again change any medication dosage without my approval’ … my consultant’s mode of communicating her point acted as very effective ‘aversion training’. I’ve never even been tempted to experiment with dosage since’ (Ppt K, Female, 60s)

However, fear of physician displeasure was also a barrier to reporting non-adherence. Terminology included ‘embarrassment’ and ‘guilt,’ and there was concern that reporting non-adherence could lead to a withdrawal of support: ‘they will give up on me’.

Theme 5: holistic care – beyond a purely medication-based focus

They’re basically pill-centred … they’re missing a trick’ (Ppt M, Female, 50s)

Rheumatologists were widely considered to be very focussed on medications, with limited/no time spent assisting patients with non-medication support to improve acceptance and self-management. Physiotherapy, psychological support, diet and pacing advice were only occasionally provided (Table 3). Fatigue was reported as the most life-changing symptom, yet only 12% felt they were receiving good/excellent support with fatigue and 41% reported no support at all.

Table 3.

Patient quotes on receiving and/or the importance of non-medication support

| Non-medication options to improve quality of life | Patient quotes |

|---|---|

| Pacing and exercise | One of the most useful things from a Doctor was my rheumatologist giving me a 30 min consultation once just to tell me to slow down, to take rest, pace myself etc. I didn’t listen at the time, but it sank in and I now do it and it is the best advice and time spent by a Doctor ever. He also told me to take up Tai Chi to aid in pain relief and relaxation … massive positive impact on my lupus (Ppt R, Female, 40s) |

| Psychological support | I have become even more appalled at the lack of counselling support for patients of lupus and other chronic diseases. It would seem that you are expected ‘to get on with it’ (Ppt 159, Female, 70s) |

| Alternatives offered to anti-depressants | My GP has also always been very understanding and supportive … suggested last week that instead of going back on antidepressants straight away that he wants me to try holistic therapy first and see how that goes. I am very lucky to have such a sympathetic GP and I can message him any time if I need to. (Ppt F, Female, 40s) |

| Fatigue management support | I appreciate that they’re doing all the stuff to do with heart and lungs as a priority … the fatigue is seen as a side effect, whereas I think it really is something that needs to be actually looked into … There must be chemical changes. There must be biology going on, and I just find it incredible that nobody seems to be able to say what that biology is (Ppt M, Female, 50s) |

| Physiotherapy | I’ve been waiting like 2 years, every time I go on about physio, to me this is a big deal like losing ability in hands and knees and stuff, whereas for her [rheumatologist] it seems like nothing but that’s on my mind quite a lot … it’s not on her agenda … Even to get some exercises I can do at home because I’ll do it. Just get some advice (Ppt A, Female, teens) |

| Holistic care | My wonderful local nurses got me into a local hospice for extra support in the form of advice on pain management, reiki, reflexology and some counselling. I am eternally grateful … practical solutions, advice, reassurance and compassion (Ppt F, Female, 40 s) |

| Occupational therapy for cognitive dysfunction | I didn't keep up with medication not because I chose not to, but often I would forget to take them, or I would forget to order new scripts in time. But now I have a monthly pill box, alarms, and working with OT for my dysfunction issues in general and that has made a big difference (Ppt J, Male, 20s) |

| Diet advice | Docs are terrible about issues of diet and lifestyle in the management of Lupus. I am on the autoimmune protocol and really notice a difference. When I eat something that doesn't agree with me I immediately fall into fatigue (Ppt 165, Female, 50s) |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this mixed-methods study is the first to explore the enduring impact of past medical interactions, particularly AMEs, on SLE/SARD patient behaviour. The potential comparison with some aspects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) [21] and other adverse life experiences [22] remains tentative, but highlights the severity of damage, and longer-term sequalae. Many participants reported repeated AMEs, particularly dismissal, psychosomatic misdiagnoses and lack of physician knowledge, often on their arduous diagnostic journeys [15, 16, 23], but also post-diagnosis. An unexpected finding in our study was that, although participants with AMEs had significantly lower satisfaction with many aspects of medical care, the non-adherence rate for the AME group as a whole was not significantly greater than the rate for the non-AME group. One theory, identified through interviews, is that AMEs contributed to both extremes of adherence, thus balancing each other out when combined quantitively. In particular, some interviewees reported greater avoidance of physicians, while others stated they were completely adherent due to the lengthy time undiagnosed and untreated.

Our findings are also in agreement with previous research identifying discordance between SLE/SARD patient and physician priorities [24–27] and the importance of medical relationships in medication adherence [8, 28]. Satisfaction with medical care was significantly lower for non-adherers and those not reporting non-adherence to their physicians, particularly in relation to support, information and listening skills. A key, previously unexplored, finding was that half of participants who reported not telling their clinicians about non-adherence gave an unsupportive/unavailable medical relationship as a reason. Supportiveness of the current medical relationship was directly cited by a quarter of participants as a reason for adhering, often with the use of the words ‘trust’ and ‘respect’ when describing their current physician(s), particularly their rheumatologist. However, many participants reported adhering to improve their QoL, regardless of the quality of their medical relationships.

Improving QoL was the most frequently cited reason for medication adherence whereas preventing organ damage and/or death—which physicians were felt to be focussed on—was only cited by <10% of participants. Physicians have guidelines to follow [29] and clearly a responsibility for ensuring medication choices prevent organ damage and reduce mortality. However, our findings suggest that medication discussions may promote greater adherence if the physician elicits each patient’s priorities and presents the more immediate as well as long-term benefits. Although this study has focussed on intentional non-adherence, we found that clinicians could also influence the frequent non-intentional non-adherence caused by the cognitive dysfunction common in many SARDs patients. Participants’ discussions of embarrassment and reticence to admit forgetting medication suggests that non-judgemental raising of the topic and advice on memory aids such as using Dosette boxes, reminder apps and family support could be helpful.

We identified a ‘hierarchy of evidence’ in both diagnosis and treatment decisions, perceived to be dominated by a limited range of blood tests (especially with GPs and less experienced rheumatologists) and clinician judgement. These were felt by patients to not always be reflective of their actual condition, or in line with their often extensive knowledge of current research, thus further reducing medical security. While ANA is helpful (although not essential) in diagnosis, the titre can vary over time independently of disease activity [30–32], and is therefore not recommended for monitoring/medication decisions [29]. Although dsDNA and/or complement are accurate biomarkers in some patients, that is not the case for all patients [33]. This research builds on previous reports [26] that greater prioritization should be given to patient-reported symptoms. Patient self-reported symptoms are often the least susceptible to external verification, yet can be the most life-changing (fatigue, pain, neurological and cognitive difficulties) [15]. Currently, most studies only use patient- reported outcomes (PROs) as secondary endpoints, if at all. This limited evidence-based data likely influences many clinicians’ preference (as perceived by these patients) for clinical or laboratory evidence over PROs. However, with such a heterogeneous disease and highly individual responses/reactions to medications, our study participants expressed strong feelings that the ‘evidence-based data’ should also include evidence gained from actively listening to their symptoms. Failure to listen to patients was commonly discussed as one of the main contributors to misdiagnoses, damaging to the clinical relationship and potentially leading to sub-optimal medication decisions. The key importance of listening in adherence was verified quantitatively by ratings for clinicians’ listening skills being significantly lower in non-adherers and non-reporters of non-adherence. Rheumatologists were also viewed as medication-focussed while patients wanted greater support with non-pharmacological measures, such as physiotherapy and psychotherapy, which have been found to improve QoL in previous studies [34–36].

This study has a number of limitations, particularly in the self-reporting and self-selecting nature of respondents to online surveys. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, reasons for adherence were extracted from open-ended answers, which can reduce reliability. In introducing the concept of AMEs for these patients, we used proxy measures that were enlightening for initial exploration of the concept yet cannot be assumed to be reliable. We will further explore the concept of AMEs, and their enduring impact, in future studies. There was a low proportion of males and respondents from minority ethnic groups leading to lower generalizability, although interviewees were selected purposively to ensure more of a balance. Interviewees had a slightly longer than average [15] length of diagnostic journey, and we did not elicit quantitative measures of severity of physical and mental health, both of which may have impacted views of care. Further details of the mixed methodology used, including strengths and limitations, are reported in the supplementary material, available at Rheumatology online.

We have extended the work of Náfrádi et al. who identified the need for a flexible physician–patient balance of control in medication decisions [37] with our findings that level of control desired differed for each patient and varied over the disease course. We have also built on Smith’s discussions of ‘institutional betrayal’ [38] and how improved physician–patient concordance in decision making can ameliorate distrust from adverse medical events. Collaboration and concordance were invariably preferred, although a more directive physician approach may be required/wanted more in the early stages of diagnosis, when severely unwell or cognitively impaired. Although fear of physician displeasure motivated adherence in some, it was also reported as a barrier to reporting any non-adherence. Intelligent or creative non-adherence [39] [40], whereby knowledgeable patients made rational decisions to self-adjust dosage or to not adhere was not infrequent, often underpinned by distrust or inadequate access to support. As it was reported to have preferable outcomes at times, patient blaming [41] and always viewing non-adherence as a negative patient behaviour is not appropriate, especially in the context of many physicians being widely perceived as lacking basic knowledge of SLE. This contributed to patient insecurity in the appropriateness and safety of diagnostic, medication or monitoring decisions. With no clear treatment pathways, and undiscovered or unclear biomarkers in some SARD patients, there is an even greater requirement for improved physician–patient communication and shared decision making, in addition to targeted, individualized tests and medication [42].

More physicians actively listening to patients, both in terms of symptom-reporting and ascertaining individual treatment goals, would improve medical relationships, satisfaction and potentially medication adherence. Optimal medication prescribing and adherence, enabled by positive medical relationships, not only improves disease outcomes but can also reduce the significant psychosocial impact of SLE. Despite the many positive current medical relationships cited by most interviewees, this study highlights the importance of clinicians being aware of the persisting impact on patient wellbeing, behaviour and medical relationships of past adverse medical experiences (AMEs).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A group of four expert patient representatives, ‘the wolf-pack’, assisted at every stage of the research, including: developing the research questions, designing and testing surveys, discussing and analysing data and critically reviewing the draft manuscript. With particular thanks to these expert team members, Lynn Holloway, Colette Barrere, Mike Bosley and Mo Blane for all their time and support with all these studies. Many of the most insightful analyses come from their discussions of the data including the concept of adverse medical experiences. Thank you also to Paul Howard and Chanpreet Walia at LUPUS UK for contributing to discussions with their vast knowledge of this patient group, and to all the participants in this study for their engagement and sharing their—sometimes difficult—experiences so willingly to help to improve the experiences of future patients. Physician influence on non-adherence relating to side-effects will be covered in more detail in a further paper. Ethical approval was obtained through the Cambridge Psychology Research Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. PRE 2018–84: Approval for survey and interviews. PRE.2018.120: Approval for analysis and quoting from the LUPUS UK forum.

Funding: This research was funded by LUPUS UK.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Additional anonymised data may be made available on request.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Contributor Information

Melanie Sloan, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Elliott Lever, Rheumatology Department, Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow.

Caroline Gordon, Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing, College of Medical and Dental Science, University of Birmingham, Birmingham.

Rupert Harwood, Patient and Public Involvement in Lupus Research Group, Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Sofia Georgopoulou, Department of Inflammation Biology, King’s College London, London.

Felix Naughton, Behavioural and Implementation Science Group, School of Health Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich.

Chris Wincup, Department of Rheumatology, University College London.

Stephen Sutton, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

David D’Cruz, The Louise Coote Lupus Unit, Guy’s and St Thomas’, NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

References

- 1. Sabaté E, ed. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Achaval S, Suarez-Almazor ME. Treatment adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2010;5:313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruiz-Irastorza G, Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Khamashta MA. Clinical efficacy and side effects of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Esdaile JM, Joseph L, MacKenzie T, Kashgarian M, Hayslett JP. The benefit of early treatment with immunosuppressive drugs in lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol 1995;22:1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hennessey A, Lukawska J, Cambridge G, Isenberg D, Leandro M. Adverse infusion reactions to rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective analysis. BMC Rheumatol 2019;3:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn J et al. The implications of therapeutic complexity on adherence to cardiovascular medications. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanlon P, Nicholl B, Jani BD et al. Examining patterns of multimorbidity, polypharmacy and risk of adverse drug reactions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional UK Biobank study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e018404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Georgopoulou S, Prothero L, D'Cruz DP. Physician-patient communication in rheumatology: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 2018;38:763–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Pouchot J, Guettrot-Imbert G et al. Adherence to treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013;27:329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feldman CH, Costenbader KH, Solomon DH, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Area-level predictors of medication nonadherence among US Medicaid beneficiaries with lupus: a multilevel study. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71: 903–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cunha C, Alexander S, Ashby D et al. Hydroxycloroquine blood concentration in lupus nephritis: a determinant of disease outcome? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018;33:1604–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson MJ. The Medication Adherence Model: a guide for assessing medication taking. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2002;16:179–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harrison JA, Mullen PD, Green LW. A meta-analysis of studies of the Health Belief Model with adults. Health Educ Res 1992;7:107–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q 1988;15:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sloan M, Harwood R, Sutton S et al. Medically explained symptoms: a mixed methods study of diagnostic, symptom and support experiences of patients with lupus and related systemic autoimmune diseases. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2020;4:rkaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sloan M, Naughton F, Harwood R et al. Is it me? The impact of patient–physician interactions on lupus patients’ psychological well-being, cognition and health-care-seeking behaviour. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2020;4:rkaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho J, Trent A. Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qual Res 2006;6:319–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res 2016;26:1802–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shapiro F. The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. Perm J 2014;18:71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Price E, Walker E. Diagnostic vertigo: the journey to diagnosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Health 2014;18:223–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Golder V, Ooi JJY, Antony AS et al. Discordance of patient and physician health status concerns in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2018;27:501–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pascoe K, Lobosco S, Bell D et al. Patient- and physician-reported satisfaction with systemic lupus erythematosus treatment in US clinical practice. Clin Ther 2017;39:1811–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kernder A, Elefante E, Chehab G et al. The patient's perspective: are quality of life and disease burden a possible treatment target in systemic lupus erythematosus? Rheumatology 2020;59:v63–v68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alarcón G, McGwin G, Brooks K et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. X1. Sources of discrepancy in perception of disease activity: a comparison of physician and patient visual analog scale scores. Arthritis Care and Research 2002;47:408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Kitas GD. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of psychosocial factors. Psychol Health Med 2004;9:337–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon C, Amissah-Arthur MB, Gayed M et al. The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Rheumatology 2018;57:e1–e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pisetsky DS, Spencer DM, Lipsky PE, Rovin BH. Assay variation in the detection of antinuclear antibodies in the sera of patients with established SLE. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:911–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sjöwall C, Sturm M, Dahle C et al. Abnormal antinuclear antibody titers are less common than generally assumed in established cases of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1994–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ippolito A, Wallace DJ, Gladman D et al. Autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison of historical and current assessment of seropositivity. Lupus 2011;20:250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thanadetsuntorn C, Ngamjanyaporn P, Setthaudom C et al. The model of circulating immune complexes and interleukin-6 improves the prediction of disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Rep 2018;8:2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatol 2003;42:1050–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Navarrete-Navarrete N, Peralta-Ramírez MI, Sabio JM et al. Quality-of-life predictor factors in patients with SLE and their modification after cognitive behavioural therapy. Lupus 2010;19:1632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karlson EW, Liang MH, Eaton H et al. A randomized clinical trial of a psychoeducational intervention to improve outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1832–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Náfrádi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shoemaker K, Smith C. The impact of patient-physician alliance on trust following an adverse event. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1342–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Britten N. Patients’ ideas about medicines: a qualitative study in a general practice population. Br J Gen Pract 1994;44:465–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hale ED, Radvanski DC, Hassett AL. The man-in-the-moon face: a qualitative study of body image, self-image and medication use in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2015;54:1220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown M, Bussell J. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lever E, Alves MR, Isenberg DA. Towards precision medicine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2020;13:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional anonymised data may be made available on request.