Abstract

Accurately determining the risk of long COVID is challenging. Existing studies in children and adolescents have considerable limitations and distinguishing long-term SARS-CoV-2 infection-associated symptoms from pandemic-related symptoms is difficult. Over half of individuals in this age group, irrespective of COVID-19, report physical and psychologic symptoms, highlighting the impact of the pandemic. More robust data is needed to inform policy decisions.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, persistent, post COVID, neurologic mental, fatigue, headache

The majority of children with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection have asymptomatic or mild disease.1 The long-term effects of the infection might therefore have greater weight in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination and other policy decisions in this age group. We recently reported that the frequency of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 in children and adolescents is uncertain.2,3 Almost all of the studies on ‘long COVID’ in this age group have considerable limitations, for example, the inclusion of children without confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and a lack of appropriate control groups.3,4 As the number of published studies on this topic has doubled, we reassessed the current evidence on long COVID in children and adolescents.

We identified 27 studies (13 cross-sectional studies,5–17 9 prospective cohort studies,18–26 4 case series27–30 and 1 retrospective cohort study31) investigating persistent symptoms in a total of 34,664 SARS-CoV-2-infected and 38,988 uninfected children and adolescents. The number of children in each study varied from 5 to 30,117 [median 105, interquartile range (IQR) 30–859]. The study findings are detailed in the Table, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/INF/E684. Studies which followed children after a SARS-CoV-2 infection but did not evaluate symptoms of long COVID,32–34 did not evaluate more than 1 symptom35 and those which did not report separate results for children and adolescents36–39 were not included.

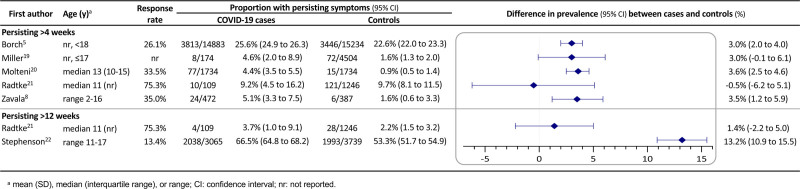

Nine of the 27 studies included an uninfected control group.5–8,18–22 Six studies compared the proportion of children and adolescents with persistent symptoms in those with and without evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.5,8,19–22 The difference in proportions varied between Please replace by -0.5% and 13.2% (median 3.0%, IQR 1.4%-3.6%) (Fig. 1). In all but one study,22 the difference was less than 4%. The study which reported a difference of 13.2% had a response rate of only 13.4% and therefore a major risk of sampling bias. A further study reported a difference of 45.2% in persistent symptoms when comparing children after SARS-CoV-2 infection with those after other respiratory infections.7 However, it is likely that a large part of this difference is attributable to the considerable difference in age between the two groups (median of 10 vs. 2 years). Two studies did not report the proportion of children affected by long COVID symptoms in the control group.6,18

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 in children and adolescents and in non-COVID-19 controls.

Although many studies included a control group, they all had other deficiencies meaning their results need to be viewed with caution. Many had low response rates or differences in response and inclusion rates between children with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/E684).

The 11 studies which investigated persisting symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection without control groups reported prevalences of long COVID symptoms between 7.9% and 58.1% (median 27.1%, IQR 12.5%–41.4%).9,13–15,17,23–26,30,31 However, many of these studies included children without laboratory-confirmed infections, studied children at arbitrary time points, relied on self- or parent-reported symptoms without clinical assessment and objective parameters or varied in the proportion of children with preexisting medical conditions.

The large variation in results from studies underlines how difficult it is to accurately determine the risk of long COVID. In addition to the lack of a clear case definition, it is impossible to blind participants to whether they have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or not. Another unavoidable limitation includes the possibility that the uninfected control group is contaminated by children who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 but who were not tested or who did not seroconvert.40 Further, studies that evaluate a single time point might miss transitory or intermittent symptoms of long COVID. Finally, the range and the number of symptoms sought in studies vary considerably and some studies have been criticized for evaluating certain key symptoms.

In future studies, it is important to collect age-aggregated data, as the incidence and characteristics of long COVID will be different in young children and adolescents. Moreover, more studies are needed to investigate the association between the initial severity of COVID-19 and the number and duration of persistent symptoms. Additionally, other risk factors for long COVID should be identified. It is also important to unravel the mechanisms underlying persistent symptoms after COVID-19 and to identify similarities to and differences from other postviral syndromes. This will help find treatment options and define the role of vaccination in the prevention of long COVID.

The fact that nearly all symptoms reported by children and adolescents infected with SARS-CoV-2 are also reported in similar frequencies in those without evidence of infection highlights that one of the major challenges remains to distinguish long-term SARS-CoV-2 infection-associated symptoms from pandemic-related symptoms. It is worrisome that more than half of children and adolescents, even when they have not had COVID-19, report physical and psychologic symptoms, highlighting how much children and adolescents have suffered from the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site www.pidj.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Coronavirus infections in children including COVID-19: an overview of the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prevention options in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:355–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann P, Pittet LF, Curtis N. Long covid in children and adolescents. BMJ. 2022;376:o143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann P, Pittet LF, Curtis N. How common is long COVID in children and adolescents? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:e482–e487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behnood SA, Shafran R, Bennett SD, et al. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst children and young people: a meta-analysis of controlled and uncontrolled studies [published online ahead of print November 24, 2021]. J Infect 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borch L, Holm M, Knudsen M, et al. Long COVID symptoms and duration in SARS-CoV-2 positive children - a nationwide cohort study [published online ahead of print October 01, 2022]. Eur J Pediatr 2022:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04345-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roessler M, Tesch F, Batram M, et al. Post COVID-19 in children, adolescents, and adults: results of a matched cohort study including more than 150,000 individuals with COVID-19. medRxiv 2021:2021.10.21.21265133. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.21.21265133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roge I, Smane L, Kivite-Urtane A, et al. Comparison of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 and other non-SARS-CoV-2 infections in children. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:752385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zavala M, Ireland G, Amin-Chowdhury Z, et al. Acute and persistent symptoms in children with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to test-negative children in England: active, prospective, national surveillance [published online ahead of print December 02, 2021]. Clin Infect Dis 2021. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asadi-Pooya AA, Nemati H, Shahisavandi M, et al. Long COVID in children and adolescents. World J Pediatr. 2021;17:495–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L, Shmueli E, Ehrlich S, et al. Long COVID in children: observations from a designated pediatric clinic. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:e509–e511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brackel CLH, Lap CR, Buddingh EP, et al. Pediatric long-COVID: an overlooked phenomenon? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:2495–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buonsenso D, Espuny Pujol F, Munblit D, et al. Clinical characteristics, activity levels and mental health problems in children with long COVID: a survey of 510 children. Preprints 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buonsenso D, Munblit D, De Rose C, et al. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2208–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erol N, Alpinar A, Erol C, et al. Intriguing new faces of Covid-19: persisting clinical symptoms and cardiac effects in children [published online ahead of print August 20, 2021]. Cardiol Young 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1017/s1047951121003693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knoke L, Schlegtendal A, Maier C, et al. More complaints than findings - Long-term pulmonary function in children and adolescents after COVID-19. medRxiv 2021:2021.06.22.21259273. doi: 10.1101/2021.06.22.21259273 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leftin Dobkin SC, Collaco JM, McGrath-Morrow SA. Protracted respiratory findings in children post-SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56:3682–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sante GD, Buonsenso D, De Rose C, et al. Immune profile of children with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Long Covid). medRxiv 2021:2021.05.07.21256539. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.07.21256539 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink TT, Marques HHS, Gualano B, et al.; HC-FMUSP Pediatric Post-COVID-19 Study Group. Persistent symptoms and decreased health-related quality of life after symptomatic pediatric COVID-19: a prospective study in a Latin American tertiary hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2021;76:e3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller F, Nguyen V, Navaratnam AMD, et al. Prevalence of persistent symptoms in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a household cohort study in England and Wales. medRxiv 2021:2021.05.28.21257602. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.28.21257602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molteni E, Sudre CH, Canas LS, et al. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic UK school-aged children tested for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:708–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radtke T, Ulyte A, Puhan MA, et al. Long-term Symptoms After SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents [published online ahead of print July 16, 2021]. JAMA 2021. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson T, Pereira SP, Shafran R, et al. Long COVID - the physical and mental health of children and non-hospitalised young people 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection; a national matched cohort study (The CLoCk) Study. Nature Portfolio, in Review 2021. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-798316/v1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, et al.; Bergen COVID-19 Research Group. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021;27:1607–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osmanov IM, Spiridonova E, Bobkova P, et al. Risk factors for long covid in previously hospitalised children using the ISARIC Global follow-up protocol: a prospective cohort study [published online ahead of print July 03, 2021]. Eur Respir J 2021. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01341-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Say D, Crawford N, McNab S, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 outcomes in children with mild and asymptomatic disease. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:e22–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterky E, Olsson-Åkefeldt S, Hertting O, et al. Persistent symptoms in Swedish children after hospitalisation due to COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2578–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludvigsson JF. Case report and systematic review suggest that children may experience similar long-term effects to adults after clinical COVID-19. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:914–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morand A, Campion JY, Lepine A, et al. Similar patterns of [(18)F]-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in paediatric and adult patients with long COVID: a paediatric case series [published online ahead of print August 21, 2021]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05528-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrow AK, Ng R, Vargas G, et al. Postacute/Long COVID in pediatrics: development of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation clinic and preliminary case series. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;100:1140–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nogueira López J, Grasa C, Calvo C, et al. Long-term symptoms of COVID-19 in children. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2282–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smane L, Stars I, Pucuka Z, et al. Persistent clinical features in paediatric patients after SARS-CoV-2 virological recovery: a retrospective population-based cohort study from a single centre in Latvia. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2020;4:e000905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denina M, Pruccoli G, Scolfaro C, et al. Sequelae of COVID-19 in hospitalized children: a 4-months follow-up. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:e458–e459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isoldi S, Mallardo S, Marcellino A, et al. The comprehensive clinic, laboratory, and instrumental evaluation of children with COVID-19: a 6-months prospective study. J Med Virol. 2021;93:3122–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bottino I, Patria MF, Milani GP, et al. Can asymptomatic or non-severe SARS-CoV-2 infection cause medium-term pulmonary sequelae in children? Front Pediatr. 2021;9:621019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusetsky Y, Meytel I, Mokoyan Z, et al. Smell status in children infected with SARS-CoV-2. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E2475–E2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, et al. Long COVID in the faroe Islands: a longitudinal study among nonhospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e4058–e4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chevinsky JR, Tao G, Lavery AM, et al. Late conditions diagnosed 1-4 months following an initial Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) encounter: a matched-cohort study using inpatient and outpatient administrative data-United States, 1 March-30 June 2020 [published online ahead of print April 29, 2021]. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(Suppl 1):S5–S16. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blankenburg J, Wekenborg MK, Reichert J, et al. Mental health of adolescents in the pandemic: long-COVID19 or long-pandemic syndrome? medRxiv 2021:2021.05.11.21257037. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.11.21257037 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Wood J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and participation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;101:48–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toh ZQ, Anderson J, Mazarakis N, et al. Reduced seroconversion in children compared to adults with mild COVID-19. medRxiv 2021:2021.10.17.21265121. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.17.21265121 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.