Abstract

Responses of visual neurons to natural scenes provide a link between classical descriptions of receptive field structure and visual perception of the natural environment. A natural scene video with a movement pattern resembling that of primate eye movements was used to evoke responses from macaque ganglion cells. Cell responses were well described through known properties of cell receptive fields. Different analyses converge to show that responses primarily derive from the temporal pattern of stimulation derived from eye movements, rather than spatial receptive field structure beyond center size and position. This was confirmed using a model that predicted ganglion cell responses close to retinal reliability, with only a small contribution of the surround relative to the center. We also found that the spatiotemporal spectrum of the stimulus is modified in ganglion cell responses, and this can reduce redundancy in the retinal signal. This is more pronounced in the magnocellular pathway, which is much better suited to transmit the detailed structure of natural scenes than the parvocellular pathway. Whitening is less important for chromatic channels. Taken together, this shows how a complex interplay across space, time and spectral content sculpts ganglion cell responses.

Keywords: Retinal ganglion cells, natural scenes, eye movements, primate vision

Introduction

Responses of visual neurons to natural scenes provide a link between classical descriptions of receptive field structure and visual perception of the natural environment. For relevance to human vision, responses of primate retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are of most interest. The visual systems of primates and humans closely resemble one another in their processing of spatial and temporal information (DeValois et al., 1974a; DeValois et al., 1974b). The three main cell systems of the afferent pathway (associated with the magnocellular (MC), parvocellular (PC) and koniocellular (KC) layers of the LGN) have all been intensively studied. We are concerned here with a quantitative description of the neuronal responses of these three systems when provided with natural stimuli. We pursue this question along three synergistic paths, which converge in the discussion section.

The first goal was to test how far primate RGC responses to natural scenes are consistent with spatial and temporal responses measured with traditional stimuli. Retinal responses to natural scenes across species are sometimes complex and challenging to interpret (Carandini et al., 2005; Wienbar & Schwartz, 2018). We survey single cell responses in the central retina in primates in vivo to natural scenes, and describe cellular responses. We show these to be consistent with known RGC properties.

A second theme is how far the retinal response, when the eye moves, is sculpted by the interaction of a scene’s spatial structure with the center-surround organization of RGC receptive fields, or whether the retinal response derives from the temporal modulation that occurs as a scene shifts across the retina due to eye and head movement (Nothdurft & Lee, 1982b; Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Pitkow & Meister, 2012). This question echoes earlier psychophysical work, where Kelly (1979) showed that the classic human spatial contrast sensitivity function (Campbell & Robson, 1968) is mostly determined by the interaction of grating drift (due to eye movement) with spatial frequency rather than spatial structure of the grating per se. Recent interest in the role of eye movements in perception has led to further evidence as to their importance, for example, in contrast detection (Ennis et al., 2014; Mostofi et al., 2016; Casile et al., 2019). We provide evidence here in favor of the temporal alternative, i.e. responses of RGCs are surprisingly well described by only two parameters: position and center size. This is in contrast to other brain regions, like primary visual areas, where the neuronal response of orientation-tuned cells is primarily sculpted by their spatial receptive field structure.

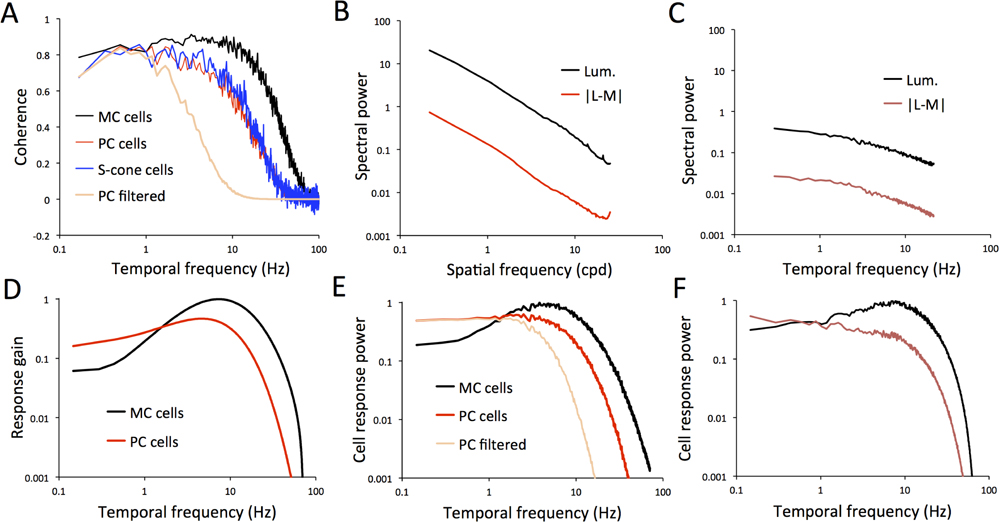

A third theme is relevant to ‘whitening’ of the retinal signal with natural scenes. Whitening or efficient encoding refers to the removal in cell responses of ubiquitous long-range correlations in natural scenes (e.g. (Burton & Moorhead, 1987)) to optimize information transfer. The spatial center-surround structure of ganglion cell receptive fields might remove redundant information in neighboring regions of natural scenes (Atick & Redlich, 1992; Dan et al., 1996; Graham et al., 2006; Dorr et al., 2010). More recently, eye and head movements were suggested to also contribute to whitening, because scanning across a scene transforms scene structure into temporal fluctuations (Rucci et al., 2007; Rucci & Victor, 2015; Segal et al., 2015). The results of the first two parts of this paper strongly support the temporal whitening hypothesis, but with caveats; such effects are most evident in the MC pathway, and whitening of the signal in the PC (and S-cone) pathways might be restricted.

Scenes can be presented in different ways. Primates continuously scan the visual environment through eye and head movements, so the pattern of movement of the scene across the retina differs significantly from, say, viewing a movie. We recorded activity of primate ganglion cells in response to a natural environment (a flower show in Holland) moved in a pattern resembling eye movements. In a preliminary study (van Hateren et al., 2002), we had reported responses to simplified stimuli, derived from natural scenes, but devoid of spatial structure. The analyses here use a full spatial video and identify the factors driving the three canonical visual pathways (magnocellular, parvocellular, and koniocellular). They show that whitening of the retinal signal is critical in the MC pathway, while in the chromatic pathways less decorrelation takes place.

Methods

Ethical approval

Macaques (M. fascicularis) were drawn from the in-house breeding colony at the MPIBPC in Göttingen. This colony consisted of one or two older males and a group of breeding females and offspring, with inside and outside runs and with free access to food and water. Young male animals (total 4; weights 2.5–4.0 kg) were taken from the breeding groups for use in experiments, and kept overnight in single cages with free water access; food was removed from cages on the evening before the experiment. Recordings providing other data sets were also carried out in these animals. The animals were initially sedated with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (10 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained with inhaled isoflurane (0.2–2%) in a 70:30 N2O-O2 mixture. Local anesthetic was applied to points of surgical intervention. EEG and ECG were monitored continuously to ensure animal health and adequate depth of anesthesia. Tachycardia or desynchronization of the EEG were countered with an increase in anesthetic depth. Muscle relaxation was maintained by a constant infusion of gallamine triethiodide (5 mg/kg/hr i.v.) with accompanying dextrose Ringer solution (5 ml/hr). Body temperature was kept close to 37.5°. End-tidal CO2 was adjusted to close to 4% by adjusting the rate of respiration. After the completion of recording (3–5 days) the animals were euthanized with an intravenous injection of barbiturate (60 mg/kg or more) until the ECG showed the heart rate to have fallen to zero. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Welfare Committee and the State of Lower Saxony Animal Welfare Committee. The experiments were performed in 1999 under a license for such experiments awarded to the senior author (BBL).

Preparation and recording.

In this section, the technical description resembles that in an earlier publication (van Hateren et al., 2002). Ganglion cell activity was recorded from the retina of the anesthetized macaque. A tungsten-in-glass recording microelectrode was introduced to the retina via a scleral hole using established techniques (Lee et al., 1989). The location of each cell’s receptive field was mapped onto a tangent screen 114 cm from the eye. Cell identification was achieved using a battery of tests including chromatic sensitivity, time course of responses and other tests previously shown to reliably distinguish between MC- and PC-cells and those with S-cone input. The center of the movie was centered on the receptive field by flashing spots (1 Hz) of decreasing sizes (down to ca. 2 arc min) and adjusting display position for maximum response. The accuracy of this localization was sometimes in error, up to several arc min. Eccentricity of receptive fields ranged between 2 and 15 degrees. Times of spike occurrence were recorded with a precision of 0.1 msec.

Stimuli.

The stimulus movie was recorded at a flower show, the Westfriese Flora (Bovenkarspel, The Netherlands). While walking through the exhibition, a movie was recorded with a digital video camera (JVC GR-DVL9600). A detailed discussion of similarity to primate visual experience is provided in the discussion section. The camera was used in progressive scan mode, at 25 frames/s (fps). The camera was held steady, with either only unintentional manual vibration or deliberate manual displacements and smooth scans. Every 2–3 seconds a shift of varying angle was made toward a new camera heading aimed at flowers of interest. The movie was presented to the monkey 6 times faster than recorded (see below), and so there were effectively 2–3 gaze shifts per second in the stimulus. This recording procedure was an attempt to roughly mimic typical eye movements, as quantified below. The recorded movie was transported to a PC, and stored as separate frames in a non-compressed format.

For the preliminary paper (van Hateren et al., 2002), we reduced the movie to a temporal stimulus. This was done by averaging the L, M, and S cone illuminances produced by the display over a circular weighting profile shaped as a raised cosine in the interval −π/2 to π/2 (full diameter 15 arcmin, positioned in the center of the movie). For both the spatial stimulus and the uniform-field stimulus, the movies were displayed with a field of 4.6×4.6 deg2 (256×256 pixels), viewed through a 4 mm artificial pupil. The stimulus contrast for each gun (relative to mean level) was tapered with a Kaiser-Bessel function to reduce edge artifacts. This can be seen in Figure 1A. The video was compressed to a mpeg-1 movie at 25 fps, and displayed at 150 fps on a PC with Windows 98SE by using the Microsoft Mediaplayer 6.4 controlled by a script increasing the displayed fps sixfold. The PC had a dual-head display video card (Matrox G400), with a dedicated display for stimulation (Iiyama Vision Master Pro 410, running at a resolution of 640×480 at 150 Hz refresh rate).

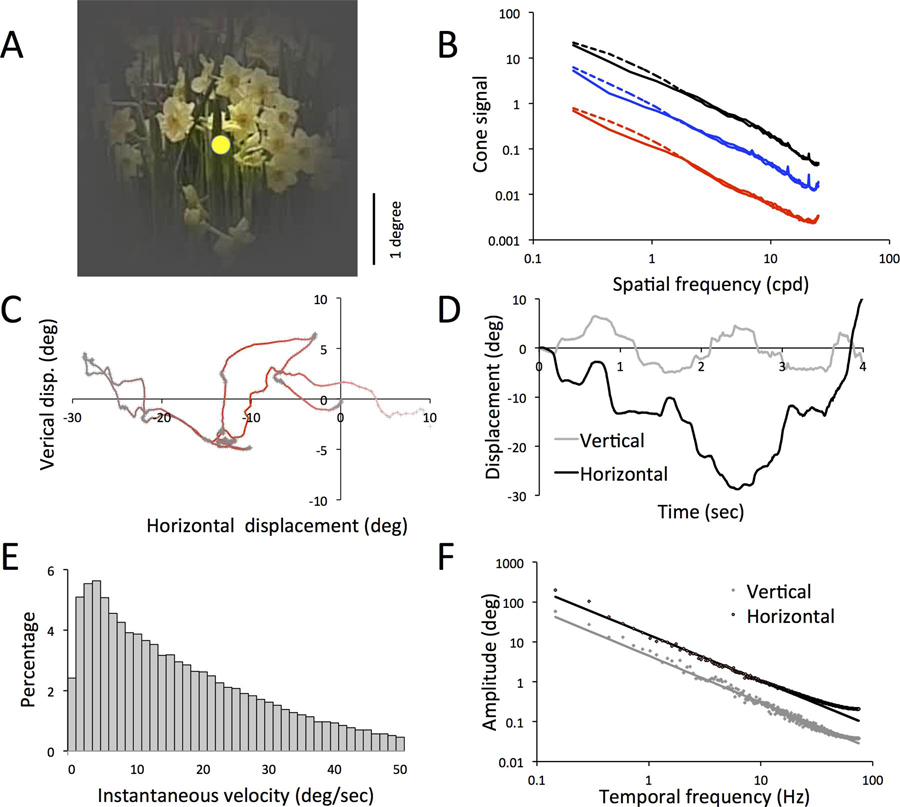

Figure 1. Statistical properties of the stimulus reflect natural scenes as seen with natural gaze shifts.

A. Sample 4×4 deg frame of video. The central disc indicates typical MC/PC center size. B. Amplitude spectra of single video frames, averaged over 10000 frames. The cone signal was derived from luminance-normalized L+M values for luminance (black), and similarly normalized |L−M| signals for the L,M chromatically opponent signal (red), and S-cone signals (blue). Best fits have slopes −1.15 (luminance), −1.18 (|L−M|) and −1.23 (S-cone). The luminance cone signal is 27.2 times larger than the L,M opponent signal at 0.22 cpd. C. Sample temporal trajectory of movements; horizontal movements are of larger amplitude than vertical movements. D. Same as C, but vertical and horizontal components are plotted as function of time. Notice the gaze-shifts between relatively stable periods E. Velocity distribution of movement derived from frame-to-frame displacements. F. Fourier amplitude spectra of horizontal and vertical movements. The straight lines are power law fits of the spectra (slopes ca. −1.1).

Two video durations were used. The spatial and full-field videos had durations of 1 min, and were repeated 6 times. Each repeat was preceded (and followed) by an equal energy white of the same mean luminance as the movie. Alternatively, a 10 min spatial movie was used, repeated several times dependent on recording stability. The movie modifies the stimulus luminances and chromaticities actually present in the natural environment by nonlinearities inherent in camera and display. Synchronization of movies with the data acquisition was achieved with timing pulses provided on the audio track of the movie.

The display used for stimulation was gamma corrected with a calibrated photomultiplier; spectral calibration was performed with an Ocean Optics spectrometer. Individual frames of the movies were extracted using FFmpeg and, after gamma correction, estimates of the luminance and the L-, M- and S-cone excitations of each pixel of each image were obtained using the Smith-Pokorny 10 degree fundamentals (Smith & Pokorny, 1975) and the emission spectrum of the screen’s three guns. Luminance (L+M) and L−M values and S-cone activations were calculated; the latter were normalized to S-cone activation for equal energy white (Boynton & Kambe, 1980).

Two-dimensional spatial frequency spectra were averaged. These are shown in Figure 1B, for the luminance (L+M), L−M and S-cone signals. Horizontal and vertical spectra differed little. Spectra were fitted with power laws (not shown: luminance parameters, amplitude 3.03, power −1.15; |L−M| parameters, 0.123, −1.18 S-cone parameters. 1.25, −1.28). Such slopes are typical for natural scenes (Burton & Moorhead, 1987; Hateren, 1992; Simoncelli & Olshausen, 2001). However, in some frames distortions associated with the mpeg compression were visible, and these are visible as minor peaks at frequencies above ca. 20 cpd in the averaged curves. The luminance signal is larger than the L−M signal, as described in the previous paper (van Hateren et al., 2002).

Reverse correlation analysis.

Standard reverse correlation procedures were employed (Chichilnisky, 2001; Pitkow & Meister, 2012; Sharpee, 2013). Spike trains were binned to a frequency of 150 Hz, the frame rate. The 64 frames before and after spike occurrence were summed. We then recover the spatiotemporal receptive fields using reverse correlation and correcting the resulting spike-weighted averages by removing bias produced by correlated stimuli.

Under the assumption of linear response and a Gaussian stimulus spectrum, this spike-triggered average is composed of a convolution of the spatiotemporal receptive field with the stimulus autocorrelation function, even in the presence of a nonlinearity (Sharpee et al., 2008; Sharpee, 2013). To remove these contributions, we deconvolved the spike-triggered average with the autocorrelation function. This was conveniently done in the Fourier domain, where the spectrum of the spatiotemporal receptive (, where k is spatial frequency and ω is temporal frequency) is obtained by the ratio of the spike-triggered average to the autocorrelation function (Theunissen et al. 2001; Theunissen et al. 2000). This was done in the presence of a regularizer λ.

| (1) |

Here FT{} indicates the Fourier transformation in space and time. AC(k, ω) is the spatiotemporal spectrum of the autocorrelation function, defined as AC(k, ω) = FT{I}(k, ω), where I is the entire video, i.e., either 90k or 9k frames displayed at 150 Hz and 256×256 pixels. Small peaks along the cardinal spatial frequency axes of the autocorrelation function corresponding to the 8×8 pixel blocks of the mpeg compression were seen and truncated. The regularization parameter corresponded to the power of the stimulus at 15 cycles per degree, λ = |AC(k = 15 cpd, ω = 0)|2, frequencies above 15 cpd accounted for only ca. 2% of power. This parameter was used for all cells. Finally we obtained the spatiotemporal receptive field by inverse Fourier transform .

Correlation.

As a means of calculating the reliability of the ganglion cell signal, the correlation of responses to the repeated one-minute movie was calculated. In order to remove high-frequency noise associated with spike generation, trains were binned to 1 msec and smoothed, using filters employed in the previous paper (van Hateren et al., 2002); 8-stage low pass filters were used with time constants of 2 msec for MC-cells and 4 msec for PC- and S-cone cells. The correlation coefficients between smoothed waveforms were calculated for further analysis. In addition, cross-correlation functions of the smoothed spike trains were calculated. This gave an indication of the temporal structure of the correlation. Functions were not made sharper by reducing the smoothing time constants. These data are not further described here.

Coherence analysis.

A detailed description of the procedure used to calculate coherence is given in the previous paper (van Hateren et al., 2002). Briefly, the 10 kHz resolution during spike acquisition was reduced to 1 ms bins. For the 1 min movie (60000 bins), the response is averaged over the 6 repeats. The power spectrum of this average is an estimate of the power strength of the signal delivered by the cell. Deviations of each response from the average can be used to derive a noise power spectrum. This permits an estimate of the frequency-dependent signal-to-noise ratio, from which coherence can be calculated as the ratio of signal power to the sum of signal and noise power. From the coherence, one can calculate the coherence rate by integrating across frequency, which provides a bound on the maximum information transmission in a noisy channel (Haag & Borst, 1998). The bit rates given were obtained by integrating coherence up to 70 Hz. This constitutes, under mild assumptions, an upper bound for the Shannon’s information rate (van Hateren & Snippe, 2001) measured in bits/sec.

Scene movement.

We extracted the movement vector from the movie frames by performing a correlation of successive frames of the RGB pixel values. The central 1.5×1.5 deg of a frame were compared with the preceding frame in pixel steps, to find the best positional match (least-squares criterion). This provided an accurate reconstruction (judging from visual inspection of the stimulus TIFF files) of the movement pattern, except for frame-to-frame displacements greater than 1 deg. These large displacements occurred ca. once a second, and would correspond to a displacement velocity greater that 150 deg/sec.

Ganglion cell models.

To predict ganglion cell responses from natural scenes, we constructed biophysically explicit models around normalized 2D Gaussian spatial center and surround mechanisms,

| (2) |

where x and x0 are vectors, with x0 the center of a receptive field mechanism relative to the video center and σ its Gaussian radius. We assumed concentric center and surround. The signals were then processed by a cascade of temporal filters. Shared across pathways is cone-specific outer retinal adaptation, which low-pass filters the signal with a series of three first-order filters (Smith et al., 2001), applies a divisive feed-back filter where the output is calculated from the input I(t) as where a(t) is the solution to the first-order differential equation , and finally a compressive nonlinearity (Lankheet et al., 1993). Note that this filter retains a certain luminance dependence, i.e. it falls short of Weber’s law. In a narrow range of inputs, a rescaling of the input by a factor s will lead to a rescaled output by ., i.e., the DeVries-Rose law. In a wider range of inputs, output is ultimately bound by the compressive nonlinearity. All signals were processed with cone adaptation (CA), before further processing that depended on the cell type, consistent with reports of the light response (Smith et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2008).

For the achromatic MC pathway, we used the combined M+L signal collected by the two gaussians corresponding to center and surround. After CA, the surround signal was delayed by an adjustable time constant, subtracted from the center, and a contrast gain control applied. Fast contrast gain control is specific to the MC pathway, and was modeled as sequence of filters, where the output O(t) is calculated from the input I(t) as where b(t) and c(t) are helper variables that obey the differential equations and , and f[…] is a squared-rectifying nonlinearity. The divisive normalization controlled the magnitude of positive peaks in the response, essentially making peaks sharper and reduced in area. This nonlinearity was chosen to be expansive, which means that large peaks are affected more strongly than small peaks. This circuit block resembles the contrast gain control mechanism described for cat ganglion cells (Victor, 1987), but for simplicity we chose a first order high-pass filter with fixed time constant, rather than an additional slow control loop with adaptive time constant (Victor, 1987; Benardete et al., 1992) or adaptive power-law shape (van Hateren et al., 2002). Finally, the output is compressed and rectified. The only difference between MC on- and MC off –center cells is the inverted action of luminance. In total, the MC model is defined by 14 parameters: 5 spatial parameters (two centering coordinates, radius of center, radius of surround, relative weight), 5 time constants, and 4 parameters controlling the non-linearities.

PC cells are cone opponent. We restricted their model to M and L cone signals separately inputting center and surround; direct physiological evidence suggests this is the case near the fovea (Lee et al., 2012). After cone-specific adaptation and compressive non-linearity, the surround is then subtracted from the center at the cone opponent stage, and the signal is sent through a compressing and rectifying nonlinearity. PC cells do not exhibit contrast gain control (Benardete et al., 1992; Yeh et al., 1995). In total, the PC model is defined by 12 parameters: 5 spatial parameters (2 center-coordinates, radius of center, radius of surround, relative weight), 3 time constants, and 4 parameters controlling the non-linearities.

For S-cone cells, we treated S, M and L cone signals separately. After cone specific adaptation, M and L signals were combined to a LM signal. This signal was delayed (Martin & Lee, 2014) and subtracted from the S-cone signal. Finally, the signal was filtered with a first-order high-pass filter, and rectified. Similar to PC cells, we found an inclusion of a contrast gain control not necessary. In total, the S- cone model is defined by 14 parameters: 6 spatial parameters (two center-coordinates, radius for S-cone, radius for LM, relative weights between S:M and S:L), 4 time constants, and 4 parameters controlling the non-linearities.

All models were optimized for the 60 sec recordings, averaged over the 6 consecutive measurements of the same stimulus on the same target cell. Briefly, spikes were translated into a smooth waveform by binning into 1ms bins, and smoothing with an 8-stage low pass filter with time constants of 2 msec for MC-cells and 4 msec for PC- and S-cone cells, as in the correlation analysis. This continuous signal was then resampled at 150 Hz, the frame rate, which is considerably higher than the point where responses reach zero coherence. As metric for comparing re-binned firing rate and model prediction, we chose the correlation coefficient.

For all three models, we disentangled spatial from temporal factors. To estimate the contribution of center and surround to the response, for MC cells we used the best-fit for the spatial receptive fields and calculated the variance explained by this signal, and then repeated the analysis without a surround. The difference in the variance we attributed to a surround contribution to the response. For PC cells, a similar procedure was adopted but as a second step center and surround diameters (the cone-opponent mechanisms) were set equal. Variance associated with retinal reliability was estimated from the 6 repeat measurements. There remains a residual variance not accounted for by the model. Figures 8,9 shows these contributions in the pie charts.

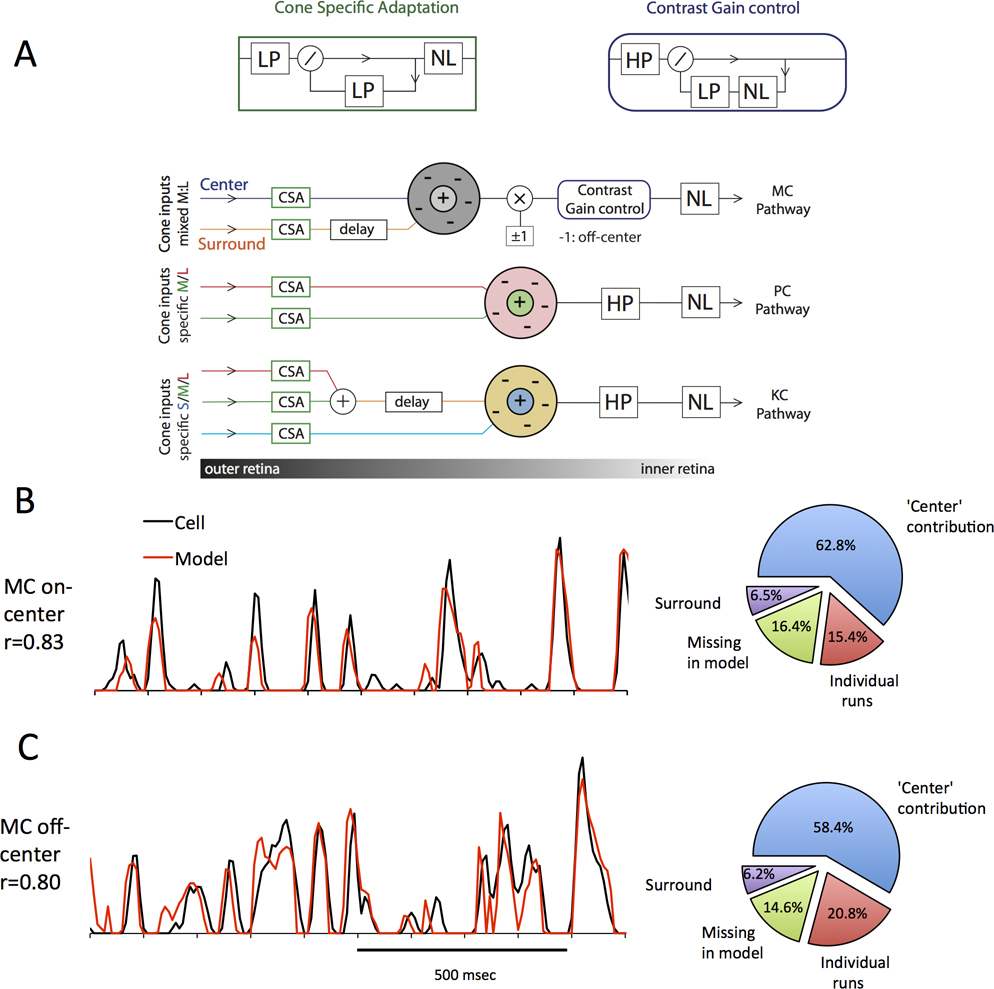

Figure 8. Construction and performance of biophysical models for RGC responses.

A Top panel: Key building blocks of the model. Cone specific adaptation (CSA) and Contrast Gain control are constructed with low-pass (LP) and high-pass (HP) filters, and a set of nonlinearities (NL), see text. Mathematical symbols indicate algebraic operations, and arrows indicate signal flow. Bottom panel: overview of the three models for magnocellular, parvocellular and koniocellular responses. Line-Colors corresponds to L and M cone signals. Blocks correspond to the blocks above. Note that MC cells only sample from luminance (fixed L:M ratio), while PC and blue-on separate the cone signals until combined to yield a cone opponent result, indicated by the RF color. B: Representative 1-second window of the response of an MC-on cell to the full stimulus, together with model prediction. Pie charts to the right indicate the key contributions to the cells’ total variance. Blue is variance explained by the center, Purple by the surround, Green: consistent response missing in model and red variations of individual runs. C: Same as B but for an MC off-center cell. For a visualization of the MC cell model as function of space and time, see supplemental video 1 and 2.

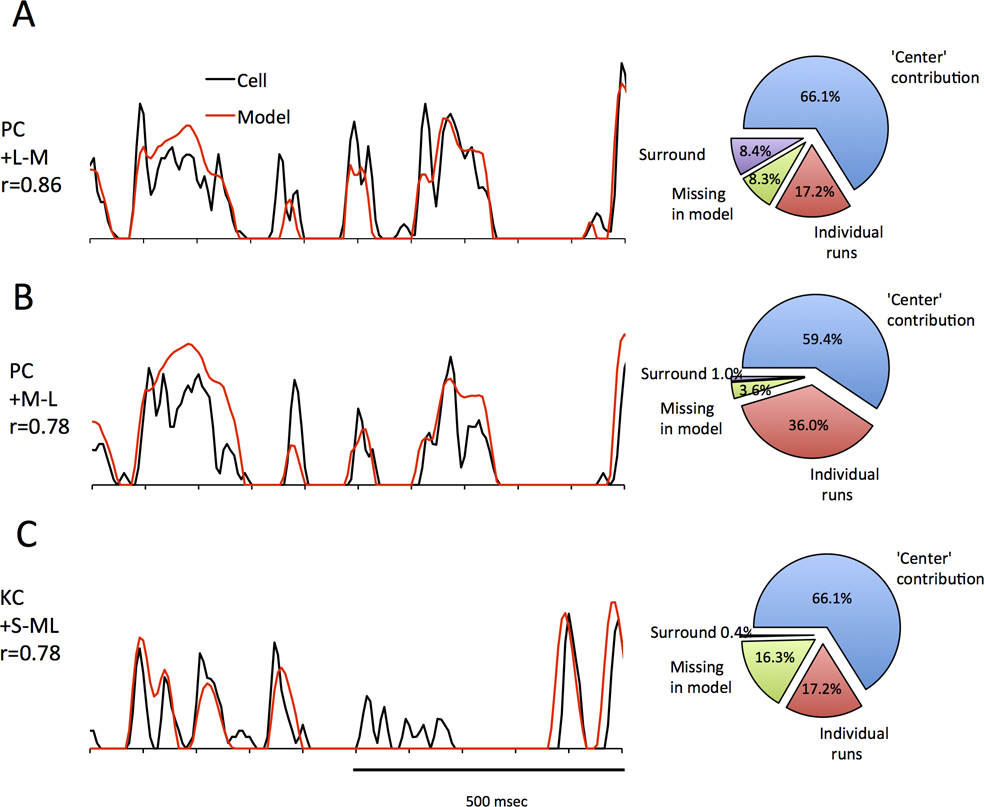

Figure 9. Model performance for cone-opponent responses.

A Representative fit to a PC +L−M cell, and model contributions. B same as A but for a green-on cell. Note the similarity to A as PC cells are mostly luminance driven. C: Representative fit to a koniocellular response. For a visualization of these models in space and time, see supplemental videos 2/3/4.

Cell samples and analysis.

Prolonged recordings of cell responses to the spatial video were obtained from 26 PC cells, 16 MC cells and 5 cells with excitatory S-cone responses. For most cells, responses to both the 6×1 and 1×10 minute videos were obtained. Stability of recordings during the recording runs was checked by monitoring mean firing rates, and inspecting the time-related correlation analysis as described below. For many cells repeated 10 minute measurements were made as a further check of stability.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical tests were performed with Python or Excel. When multiple comparisons were made on the same data, the Bonferroni correction of p-values was performed by multiplying the unadjusted p-value by the number of multiple comparisons made.

Results

The video and its motion pattern

To better understand how closely our stimulus resembles natural viewing, we first briefly review some stimulus details. An individual frame is shown in Figure 1A; the central spot indicates the typical size of a receptive field center in parafoveal retina (Lee, 2011). Spatial frequency spectra, averaged over frames, are shown in Figure 1B. The luminance signal for this stimulus was ca. 25 times larger than the L−M signal, as described in the previous paper (van Hateren et al., 2002).

We plot a typical 3 sec movement segment in Figure 1C. Figure 1D show the horizontal and vertical components as a function of time. There is some resemblance to standard eye movement patterns, with relatively stationary ‘fixation’ periods interspersed with faster movements. However, the abrupt, rapid displacements associated with saccades are not readily apparent. Frame-by-frame examination revealed many small movements of 1–3 pixels, presumably associated with muscular tremor when holding the camera. There was more movement in the horizontal direction, presumably associated with walking through the scene. Instantaneous drift velocity across the retina (from frame-to-frame comparison) is shown in Figure 1E. The shape of the distribution resembles that for velocities in the absence of head fixation (see discussion). The fourier amplitude spectra of the horizontal and vertical movement components are shown in Figure 1F; spectra of 10 six-second segments were averaged. The data points have been fitted with power laws (fit parameters: horizontal amplitude 14.9, power −1.14; vertical amplitude 4.5, power −1.17). The ca. 3.35 greater amplitude at 1 Hz of the horizontal movement is apparent.

This analysis suggests that the scene movement in these experiments plausibly mimicked that of humans viewing a natural scene.

Reverse correlation and receptive field structure

With these complex spatio-temporal stimuli, we next considered whether receptive fields from our data, derived using reverse correlation techniques (Chichilnisky, 2001; Ringach & Shapley, 2004; Sharpee, 2013), resemble reports in the literature typically obtained with simpler stimuli. With structured stimulus patterns, estimates of field structure can be generated by whitening the reverse correlation response using the covariance matrix of the stimulus (Chichilnisky, 2001; Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Pitkow & Meister, 2012; Sharpee, 2013). The goal of the next sections is to relate such reverse correlation maps to receptive field properties estimated using traditional stimuli.

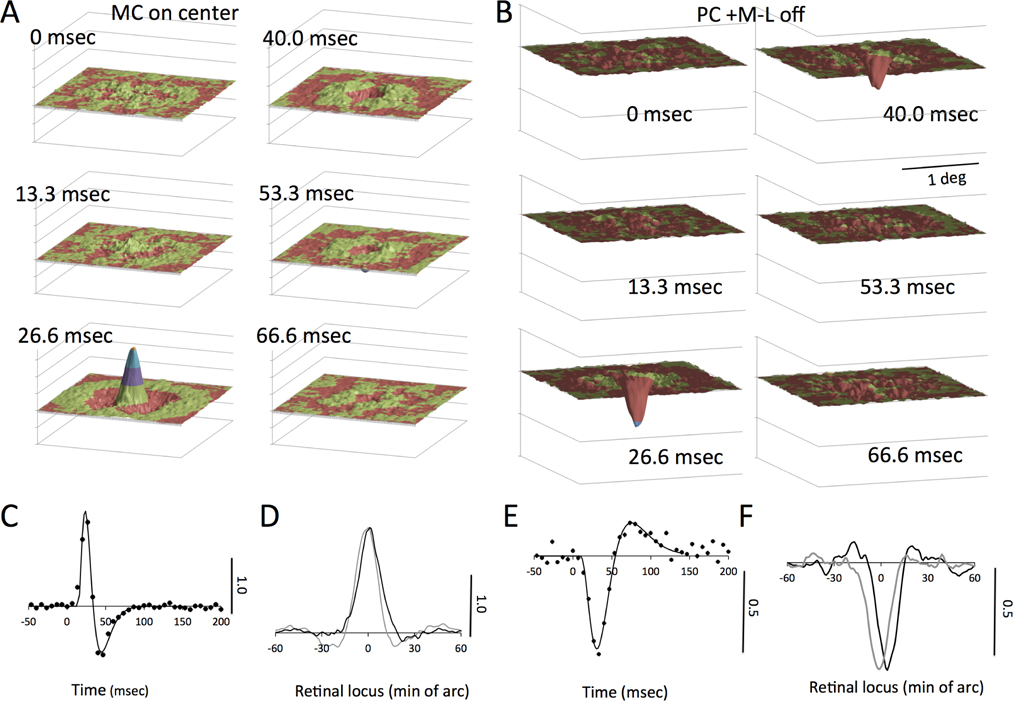

We first describe luminance responses. MC cells are much more sensitive to luminance contrast than PC cells. However, in natural scenes luminance contrast dominates (Fig. 1B) so a significant luminance response is expected from PC cells. Figure 2 shows maps from an on-center MC cell and an off −L+M PC cell. Maps for alternate frames are shown (2×2 deg; half the stimulus video size). Positive (on-center cell Fig. 2A) or negative peaks (off-center cell, Fig. 2B) arise in the 26.6 msec frame, extending to later frames in the PC cell; this fits with cells’ temporal response at mid-photopic levels (Lee et al., 1990; Lee et al., 1994). A weak center-surround structure can be seen. The MC-cell map resembles those shown in Chichilnisky and Kalmar (2002). There is a peak reversed in polarity in the later frames, especially for the MC cell. This is shown more clearly in impulse response functions derived from the central pixels of the peak (Fig. 2C,E). The amplitude scale bar is arbitrary but the same for all plots in this and subsequent figures. The solid curves in these temporal plots are fits of a model described later. Finally, horizontal and vertical cuts through the peaks are plotted in Figure 2D,F. The video center was at locus 0, but inadequate centering sometimes shifted the peaks away from this point. The indications of center-surround structure in these sections were variable and often weak. The PC cells and MC cells were recorded at similar eccentricities and show little difference in width of the peaks. This is consistent with the general finding that receptive field center sizes of PC and MC cells are similar in central retina (reviewed in Lee (2011)). A quantitative survey is provided in a later section.

Figure 2. Spatiotemporal luminance response maps for on-center MC cell (A) and off +M−L PC cell (B).

A,B. The central 2×2 deg of alternate frames is shown. Colors indicate amplitude. A central peak representing the receptive field center and a weak surround is seen. C,E. Temporal response functions of cells, derived from a weighted average of the 9 pixels around the peak. Response of the PC cell is less biphasic and slower. Fitted curves as derived in the text. D,F. Horizontal and vertical profiles through the spatial peak at 26.6 msec (cf. A,B). These may be displaced from zero, the video center, due to inadequate centering. The amplitude of the signal has been normalized to the same value for all luminance plots in this and the subsequent figures.

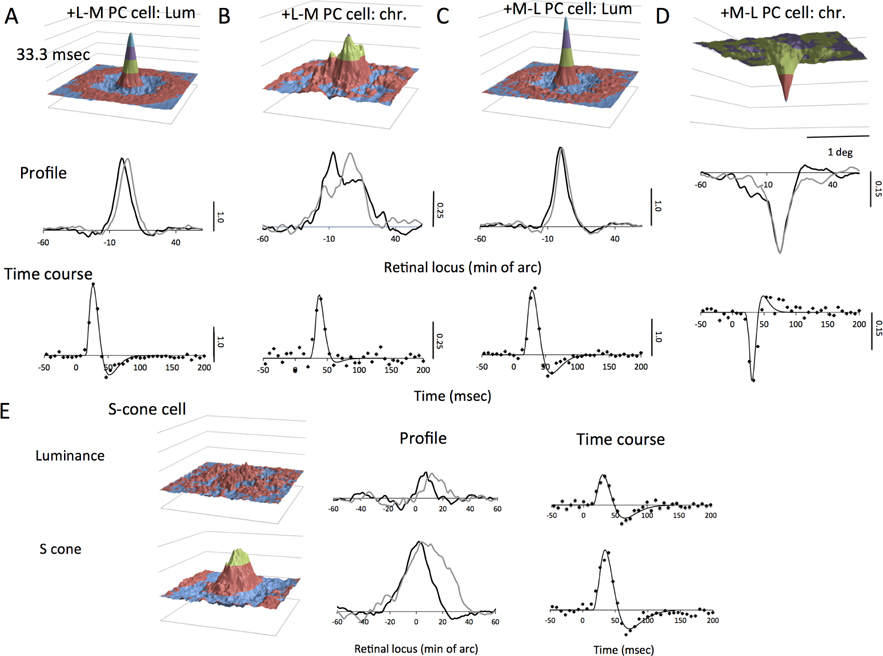

Despite the lower luminance contrast sensitivity of PC cells, they showed well-defined peaks in luminance response maps. We also derived cell responses to the L−M opponent signal. In Figure 3, both +L−M and +M−L cells gave excitatory responses to luminance as seen in response maps at 33 msec latency. Sections through the peak and temporal response are similar to those of the cell in Figure 2. The L−M signal response map (Fig. 3B) is broader in diameter and less regular in shape, as seen in the cross sections. Temporal response is of similar time course to that for luminance but more monophasic. The polarity of response is consistent with the +L−M opponent signal. For the +M−L cell, similar response patterns are seen, except that the polarity of the response to the L−M signal was reversed (Fig. 3D). These features were common through the cell sample; the response maps to the L−M signal were spatially less well defined, and the signal noisier. This is also seen in the temporal response; the peak amplitude relative to the baseline noise is less. This is due to the lower |L−M| cone contrast compared to luminance, as quantified in the next section. Response maps of MC cells to the |L−M| signal were noisy without consistent structure.

Figure 3. Response maps of PC and S-cone cells to luminance and chromatic signals.

A,B. Maps and temporal and spatial response profiles of +L−M cell with an excitatory luminance response. The chromatic responses are noisier due to the low |L−M| contrast in the natural scene; there is a positive peak since the response is referred to the +L−M signal. The spatial profile is broader for |L−M| than for luminance. The temporal response is more monophasic. C,D. Maps and temporal and spatial response profiles of +M−L cell with an excitatory luminance response. The chromatic response is inverted because cone inputs are inverted in sign. E. Responses of S-cone cell to luminance and S cone. Luminance response was weak for this cell. Sections through luminance and S cone maps also shown.

We recorded from a limited sample of cells with excitatory S-cone input. An example is shown in Figure 3E. Peak luminance responses and responses correlated with S-cone excitation are shown. A weak luminance response is present. A clear response peak associated with S-cone excitation is apparent. Spatial profiles for luminance were broader than for MC- and PC- cells. The temporal response was of similar time course to that of PC cells, as described elsewhere (Yeh et al., 1995).

Quantitative analysis of cell responses

In this section we provide a quantitative analysis of various features of cell response maps and relate them to properties of ganglion cells measured with traditional stimuli. Our data were obtained from central retina in the in vivo preparation. They may provide a link to data and models available from primate retina in vitro obtained using reverse correlation techniques at greater retinal eccentricities.

As background, we first consider firing rates. During the videos, firing rates were higher for MC cells than PC cells (means 43.75 imp/sec, S.D. 11.2, n=16 cells; 35.6 imp/sec, S.D. 12.1, n=26 cells; p=0.0422 (t test; corrected for multiple comparisons); S-cone cell mean 27.7 imp/sec, S.D. 7.75, n=5 cells; p=0.00458; corrected for multiple comparisons. These are somewhat higher rates than steady discharges with a uniform field at a similar retinal illuminance (Troy & Lee, 1994), which are ca. 20 imp/sec, for all cell types. These rates are higher than those usual in the vitro preparation (Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002).

To quantify receptive field profiles, we fitted the peak response frame with a linear two-dimensional difference-of-Gaussians (DoG) model (Eq. 2), using a least-squares criterion. Most response plots were close to circular, and we assumed that receptive fields were circularly symmetric, and that center and surround were concentric. A sample fit is shown in Figure 4A,B for a +L−M cell, where A is the cell response and B the fit. The peak of the field is satisfactorily described by the fit. The cell response map shows a weak inhibitory surround with a weak disinhibitory region around it. This latter structure cannot be captured by the simple DoG model.

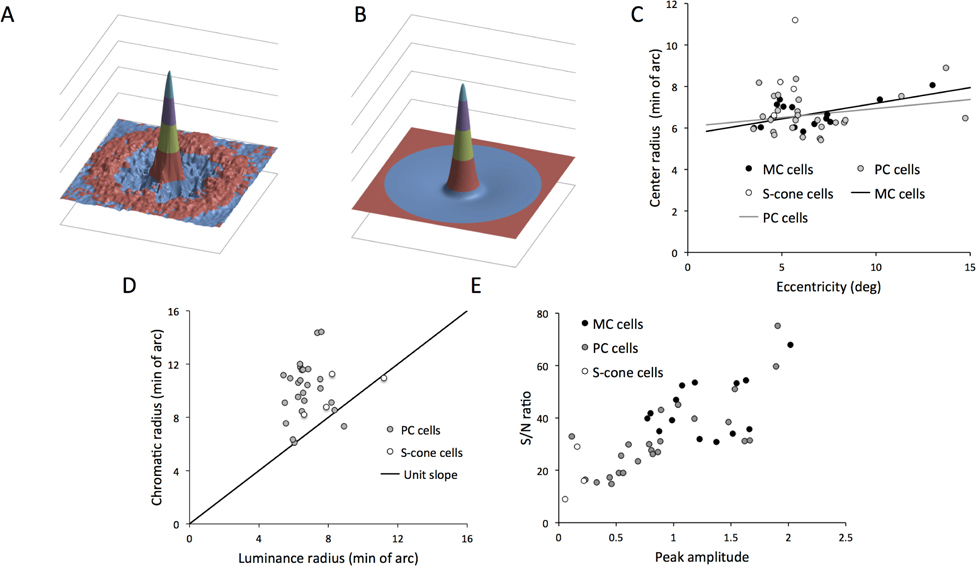

Figure 4. Fits and statistics of receptive field properties.

A, response map and, B, fit of difference-of-Gaussian model for a MC cell. Response maps often show a weak surround with a larger, weak disinhibitory area. The fit captures the shape of the peak but the disinhibitory region is not captured. C. Relation of center gaussian radius to eccentricity. D. Center sizes are similar for MC and PC cells and scatter is restricted in extent. Straight lines indicate linear fits. Although the range of eccentricities is restricted, MC center sizes significantly increase with eccentricity. S-cone cells show larger center diameters. Center radius for chromatic response maps for PC and S-cone cells also shown. The chromatic radius is larger, on average by 55%, and S-cone cells fall closer to unity. E. Scatterplot of the peak amplitude of the luminance response map as function of the signal-to-noise ratio of the luminance response map, defined by the ratio of the peak amplitude to the baseline standard deviation (see text). High luminance responses are reflected by both, high S/N and high peak amplitude. Note: PC and MC cell distributions overlap considerably, but PC cells show more variability with typically smaller peak values in comparison to MC cells. S-cone cells populate the bottom of the range.

First estimates suggested that center sizes of PC cells were smaller than those of MC cells (de Monasterio & Gouras, 1975). However, cumulative evidence suggests that there is little difference in size, at least in central retina (Lee, 1996). Center radii from the luminance fits are plotted as a function of eccentricity in Figure 4C for PC, MC cells and S-cone cells; values for subgroups of these cell classes did not differ in our sample. For repeat measurements on the same cells, radii differed by less than 5%. The distribution of radii for PC and MC (and S-cone) cells overlap, as in Derrington and Lennie (1984), and in other measurements in the literature (Lee, 1996); values are comparable with those measurements. Although the range of eccentricities was limited, there is an indication of an increase in center size with eccentricity. This was significant for MC cells (p=0.0197 n=16 cells) but not for PC cells (p=0.292 n=26 cells; least-squares regression lines are shown in Fig. 4C). The scatter in center sizes is restricted in comparison with measurements based on spatial frequency tuning curves (e.g., Derrington and Lennie (1984)). This is likely due to the dense spatial sampling inherent in the use of natural scenes, which leads more accurate estimates.

To disambiguate chromatic from luminance responses, we also fitted the |L−M| response fields of PC cells with a single Gaussian function. Luminance and chromatic radii for PC and S-cone cells are compared in Figure 4D. For PC cells, the chromatic are larger than the luminance values, as expected since center and surround act in synergy to generate the chromatic response. The mean ratio of |L−M| to luminance diameter was by a factor of 1.53 (mean across n=26 PC cells; S.D. 0.337). However, there was a continuous distribution of values, consistent with a continuum of field structure from Type I (center-surround structure) to Type II (opponent cone mechanisms are co-extensive) in PC cells (Derrington & Lennie, 1984; Lee et al., 2018). Ratios for the few S-cone cells fall closer to unity, consistent with a Type II field structure for these cells.

MC cells possess greater luminance contrast sensitivity than PC cells, i.e., greater responsivity to low luminance contrast (Kaplan & Shapley, 1986; Lee et al., 1989; Lee et al., 1990). One might therefore expect that response maps from MC cells should show greater peak amplitudes. However, MC cells’ responses rapidly saturate with increasing contrast due to contrast gain controls, while those of PC cells do not (Purpura et al., 1987; Lee et al., 1990). The range of intensities in the videos was well within the range where contrast (and luminance) gain controls might be expected to operate. We therefore tested if MC cells yielded, on average, larger luminance responses than PC cells. To estimate if MC cell luminance responses were larger than PC cell responses, we used two measures. One was peak amplitude. The same whitening and regularization was used for each cell. Secondly, we estimated the signal-to-noise ratio in responses by calculating the ratio of the peak amplitude in impulse responses (normalized as in Figs. 2) to the baseline standard deviation. These two estimates are shown as a scatterplot in Figure 4E for the different cell classes. There is a correlation between the two values (correlation coefficient 0.78, p<0.0001). PC and MC cell distributions overlap to a considerable extent, but PC cell data show much variability with many cell points falling in the lower ranges. On average, peak values for MC cells are larger than for PC cells (MC mean 1.26, S.D. 0.37, PC mean 0.81, S.D. 0.52; p = 0.0146, t test), consistent with their greater luminance contrast sensitivity. However, the ratio of contrast sensitivities is almost a log unit, and in Figure 4 the difference is much less, presumably due to the rapid saturation of MC cell responses. Those PC cells delivering a larger response presumably are those with an L/M cone-weighting imbalance. The limited sample of S-cone cells fell toward the bottom of the range.

Of the other parameters for the luminance fits, the ratio of center/surround weights (ks /kc) was similar for MC and PC cells (MC mean 0.126, S.D. 0.014 n = 16, PC mean 0.113, S.D. 0.024, n =26 p = 0.0951, t test) and the ratio of center/surround diameters (rc /rs) was also similar (2.93 for MC cells and 3.06 for PC-cells, p = 0.26). These values would suggest that the surround is weakly expressed in responses to natural scenes. The x,y values represent errors in centering the receptive field within the video. Errors were radially symmetric with a mean positional error (z) of 5.6 min of arc. Lastly, we estimated the signal-to-noise ratio in the responses of PC cells to luminance and chromatic components. These ratios were 32.2 (S.D. 14.7) for luminance and 8.0 (S.D. 4.58) for |L−M| (p<0.0001, n = 26, paired t test). Thus, as mentioned in the previous section, the high responsivity of PC cells to |L−M| modulation does not fully compensate for the low |L−M| contrast in the natural scene.

Temporal response

We now consider the temporal response. The time course of ganglion (or LGN) cell responses has been investigated with reverse correlation techniques in several species, and off-center cells have often been reported to respond more rapidly than on center cells. In the primate however, results have been mixed (Benardete & Kaplan, 1999; Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Reid & Shapley, 2002). We analyzed temporal responses to see how far this was the case in our cell sample. Each temporal data set was fitted with a difference of two 4-stage low-pass filters with delay.

| (3) |

where p1,2 are amplitude scaling factors, δ1,2 are delay terms and τ1,2 are time constants (and n=4). These fits are the curves shown in the temporal responses in Figs. 2–3. They can be seen to provide an adequate description of the data. From these curves, we extracted three temporal parameters – the time to peak, the time to crossover, and the time to trough. A further parameter was an estimate of response transience, the ratio of the trough-to-peak areas under the curve. A ratio of one indicates a fully transient response, and a ratio of zero a fully sustained response, with no transient component. Mean (and S.D.) of parameters for different cell classes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Fit values for the temporal response kernel across cell types.

Stated are mean peak, trough and crossover (in msec), and the mean transience index (the ratio of the integrated area under the second lobe of the temporal kernel, divided by the area of the first lobe. If they are equal (TI=1), the response is fully transient, if there is no second lobe the ratio is TI=0). The value provided is averaged across cells together with standard deviation (in parentheses). The number of cells n that went into the average is stated in the table. Indicated in brackets (...) is the standard deviation.

| Peak (msec) | Trough (msec) | Crossover (msec) | Transience index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC on n=11 | 23.6 (1.9) | 46.3 (3.1) | 35.4 (2.4) | 0.98 (0.12) |

| MC off n=5 | 26.6 (2.0) | 55.5 (4.3) | 41.1 (2.9) | 1.12 (0.16) |

| PC on +L-M n=12 | 26.6 (11) | 55.7 (4.2) | 43.7 (2.9) | 0.49 (0.08) |

| PC off +L-M n=7 | 29.1 (16) | 78.6 (4.4) | 56.0 (4.0) | 0.51 (0.14) |

| PC on +M-L n=7 | 28.3 (12) | 59.0 (3.5) | 45.7 (2.4) | 0.58 (0.19) |

| PC off +M-L n=3 | 29.6 (0.9) | 76.3 (2.8) | 54.4 (2.7) | 0.58 (0.10) |

Combining different cell groups from this table, all temporal parameters for MC cells were one or two milliseconds faster than for PC cells (p <0.0001 in all cases; t tests, subtypes of cells of the two groups combined). This is consistent with previous measurements (Lee et al., 1994; Reid & Shapley, 2002). Comparing MC on- and off-center cells, on cells had slightly shorter timing latencies than off cells (p = 0.0350 for time-to-peak, p = 0.00396 for time to crossover and p = 0.00113 time to trough; t tests, corrected). Comparing PC on- and off-center cells, again on cells had shorter timing latencies than off cells (p = 0.00230 time to peak; p < 0.0001 for time to crossover and time to trough). A similar result for PC cells was noted previously (Lankheet et al., 1998). Lastly, the transience index was close to one for both on- and off-center MC cells, indicating highly transient responses. All PC cell groups had much lower transience indices, indicating more sustained responses (p< 0.0001; t test). Between subclasses in these groups there was no systematic difference. We review the relation of these differences to other reports in the discussion.

Reliability and correlation

After establishing that spatio-temporal receptive field properties matched expectations from the literature, we next seek to identify the prime drivers of neuronal activity in the stimulus video. The next sections demonstrate that the temporal pattern of stimulation due to the simulated eye movements interact with center size and locus to determine cell responses, rather than the interaction of spatial structure in the scene with center-surround receptive field structure. To make this analysis, we first considered correlation within and between cells. This provides a framework to show that temporal factors are critical.

Recordings of simultaneous activity of many cells have provided substantial insights into the role of correlated firing in determining information transfer from the retina (Greschner et al., 2011). We recorded from single cells and so could not compare simultaneous responses from different cells, but we can consider correlation between successive responses to the video of the same cell, and between different cells. We first sketch the pattern of cell responses to the video.

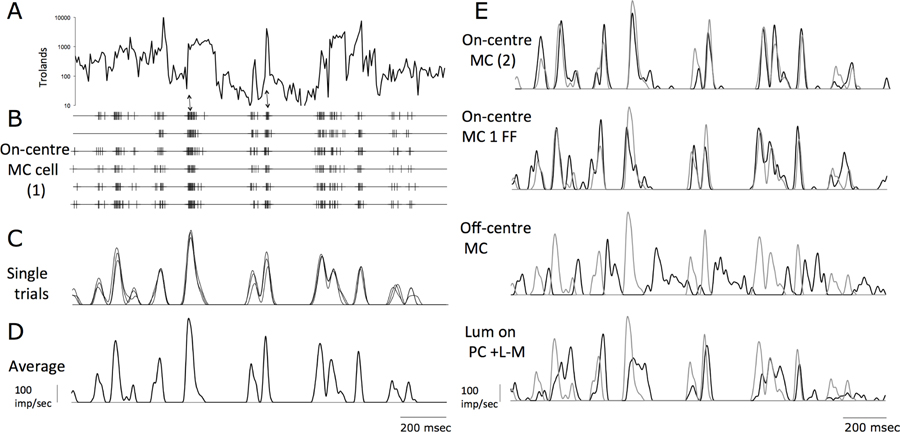

Some examples of responses to a 1 second stretch of the video are shown in Figure 5. In the top panel, Figure 5A, the luminance averaged over the central 9 pixels is plotted on a logarithmic scale. In Figure 5B, spike responses of an on-center MC cell to 6 stimulus repetitions are shown. Bursts of impulses are often associated with rapid luminance increments (two examples are arrowed); this correspondence was less obvious when luminance was scaled linearly, indicating significant response compression. As in previous studies (Pitkow & Meister, 2012), the characteristic pattern was bursts of impulse interspersed with silent periods, especially in MC cells. It was frequently the case that for some frames one or more impulses were evoked on every trial, resulting in high instantaneous firing rates (see scale bar). Some trial-to-trial variability in responses is apparent. To quantify trial-to-trial correlation, we first smoothed each spike train with a low-pass filter, as described in the methods section. The low-pass filter was chosen to have a cutoff similar to that of MC (or PC) cells’ temporal frequency response (van Hateren et al., 2002). Curves for 3 of the 6 repeats are shown in Figure 5C; similarity is apparent, with some variability. The averaged waveform over all trials is shown in Figure 5D.

Figure 5. Example data of different cell types to different stimuli.

A. Sample 1.5 sec trace of video log luminance (averaged over central 9 pixels). A logarithmic axis has been used; luminance varies over 3 log units. B. Sample spike traces of 6 repetitions of video for on-center MC cell. Bursts of spikes are associated with luminance increments; two instances are arrowed. C. Smoothed traces of 3 of the 6 sweeps, filtered as described in Methods. D. Mean response of the 6 traces E. Top comparison: response of a second MC cell (black trace) compared to the trace from D (grey trace). Next comparison: response of the MC cell to spatial (grey trace) and full-field (black trace) videos. Significant correlation is apparent. Next panel: comparison of the on- and an off-center MC cell; responses are opposite in phase. Next panel: comparison of +L−M on-luminance cell with the MC cell. Correlation is weak.

How do these responses relate to cell class? Of the recorded cells, on- and off-center MC cells make up two classes. PC cells were grouped according to whether the luminance component of the video evoked an increase or decrease in firing rate (on or off), and to a cell’s cone inputs (+L−M or +M−L), i.e., 4 classes. When the averaged responses of two cells of the same class were compared, they showed obvious similarities. The cell of the top panel of Figure 5E (MC cell 2) was another well-centered on-center MC cell (black trace); the replotted trace from Figure 5D (grey trace) shows general similarities, with differences in detail. The second panel shows responses obtained from the same cell as in Figure 5D, but with the non-spatial stimulus (van Hateren et al., 2002); the spatial panel data are again shown in grey. Again, there are close similarities but with differences in detail. Responses of an off-center MC cell are clearly different (Fig. 5E) from the on-center cells, and largely opposite in polarity; when one cell responds the other is silent. Lastly, responses of a +L−M cell with an excitatory luminance response are shown in the bottom panel; there is only occasional correspondence to the responses of the on-center MC-cells.

To quantify the similarity of responses, we calculated correlation coefficients over the 60 seconds. Values for each cell class can be found in Table 2. Correlations of repeat measurements on the same cell are shown in the Single Trials column, and vary from 0.58 to 0.81. Values are higher for MC cells than PC cells (t test, p = 0.000554), and higher for PC lum-on cells than PC lum-off cells (p = 0.00140. These values provide a reference when comparing responses of different cells. We next correlated the averaged responses (e.g., those in Fig. 2) between different cells. Averaged values are given in Table 2. Cells of the same type showed well-correlated responses; these values lie on the diagonal in Table 1. They lie in the range (0.59–0.75), somewhat lower than the range found for correlation within cells. Between cells of different types, there is less correlation in responses; in particular, on and off cell responses are negatively correlated, as anticipated.

Table 2: Correlation within and between cells.

Stated are mean correlation coefficients between the response of the seven cell classes together with standard deviations. The number of cells n used to calculate the average is stated in the table. Lm on and Lm off refer to whether cells gave an on or off luminance response. Correlation between repeat measures o the same cell or between cells of the same type are high. Correlations between cells of different types are lower. Indicated in brackets (...) is the standard deviation.

| Single Trials | MC on | MC off | Lm on +L-M | Lm off +L-M | Lm on +M-L | Lm off +M-L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC on n=12 | 0.81 (0.058) | 0.72 (0.16) | −0.31 (0.1) | 0.46 (0.14) | −0.36 (0.07) | 0.35 (0.13) | −0.39 (0.07) |

| MC off n=7 | 0.76 (0.041) | 0.59 (0.11) | −0.27 (0.14) | 0.33 (0.14) | −0.22 (0.11) | 0.34 (0.15) | |

| Lm on +L-M n=10 | 0.74 (0.099) | 0.69 (0.11) | −0.39 (0.13) | 0.47 (0.21) | −0.54 (0.12) | ||

| Lm off +L-M n=7 | 0.58 (0.059) | 0.67 (0.09) | −0.54 (0.17) | 0.65 (0.11) | |||

| Lm on +M-L n=7 | 0.72 (0.050) | 0.62 (0.16) | −0.48 (0.15) | ||||

| Lm off +M-L n=3 | 0.64 (0.076) | 0.75 (0.07) | |||||

| S-cone cells n=5 | 0.81 (0.075) |

To validate the correlation analysis on smooth firing rates, we also calculated the full temporal auto- and cross-correlation functions of spike trains over time without smoothing (not shown). Correlation functions of repeat measurements on cells of the same type were similar (full width at half height 22 msec for MC, 28 msec for PC cells), very similar to functions for cells of the same type. For cells of different types, correlation functions were broader (full width at half height >50 msec), inverted for on-off comparisons and often temporally asymmetrical; this latter feature would be expected when comparing temporal signals of cells with different temporal properties. We do not consider this aspect of the data further here.

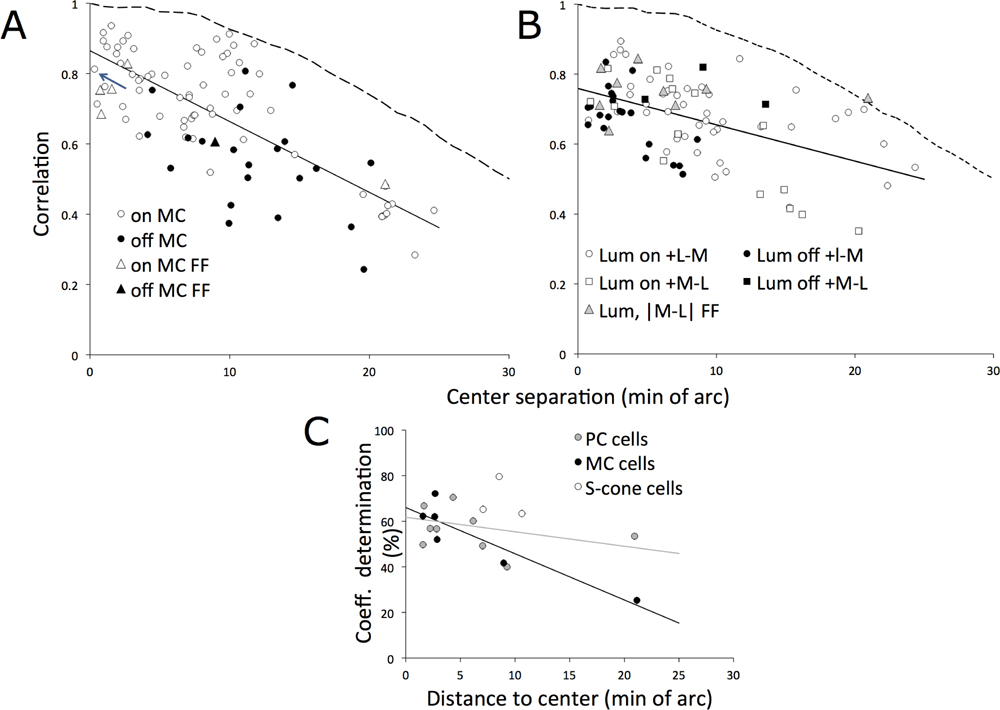

How does the pairwise correlation depend on the separation between two RF loci? In our experiments, effective separation depended on the accuracy of the centering of the receptive fields on the video. This allows us to compare our data to the study by Pitkow and Meister (2012), which was primarily concerned with correlations across neighboring cells. From the reverse correlation analysis, it was possible to assess receptive field location relative to the video’s center. Centering was sometimes many minutes of arc in error (mean error PC cells 5.50 S.D. 4.81 min of arc; MC cells 8.15 S.D. 4.78). These dimensions are comparable with receptive field center radii at this eccentricity. Thus, variability in correlation between cells may be partly due to their sampling different loci of the video, and the averaged values in Table 1 just represent lower bounds. This is supported by the plots in Figure 6A,B. The correlation coefficients of pairs of cells of the same type are plotted against the separation of the cells’ receptive fields in the video. Figure 6A shows comparisons of MC cells. The farther separated the cell pairs’ loci, the less correlated their responses, as expected. Correlations were fit with a straight line. Figure 6B shows comparisons for PC cells. Again, correlation decreases with separation. The slope of the regression line is shallower than for MC cells. Extrapolating to zero separation yielded an intercept of 0.865 (95% confidence interval 0.02) for MC and 0.76 for PC cells (95% confidence interval 0.02). These intercepts are similar to the single trial values; this confirms that the averaged values along the diagonal in Table 2 represent a lower bound, since they do not take spatial separation of fields into account.

Figure 6. Statistical analysis of correlation coefficients between pairs of ganglion cells.

A. Coefficients for MC cells plotted as a function of the separation of the cells, estimated from receptive field centers. The arrow indicates the cell pair in Fig. 2E (top). Straight line indicates a linear fit. Triangles show correlation between responses to spatial and full-field videos for the same cell and fall into the main sequence. Separation for these points is between the reverse correlation peak and the central pixel. B. Same analysis as in A but for PC cells. In A,B, the dashed lines show the autocorrelation function of averaged stimulus frames, normalized to unity. C. Coefficients of determination for the cell sample for which both spatial and full-field videos were tested, plotted against the distance of the receptive field center from the center of the video (the central pixels were used to derive the full-field stimulus). Lines are linear fits to PC and MC cells. Note that the high coefficients of determination indicate that most of the variance in the spatial video response can be accounted for by the response to the full-field video.

Based on this analysis, we can now consider the subset of cells that were recorded with both spatial and full-field stimuli. Centering errors also occurred for these cells. Since the full-field stimulus was derived from the center of the video, the peak displacement from the reverse correlation yields a separation estimate. Correlation values for these cells are included in Figure 6A,B (triangles). These values fall within the range of the cross-cell comparisons. This strongly suggests that full-field and spatial video responses are highly correlated; weaker correlations were due to poor centering.

In the context of these high correlations, we considered whether the majority of neuronal response is cause by temporal variations. To quantify this issue, we calculated the coefficient of determination for the cells tested with both spatial and full-field videos as in Eq. 3.

| (4) |

where rf(i(t)) is the firing rate for the spatial stimulus in a single trial, i, RS(t) is the averaged response over trials to the full-field stimulus and μit represents the mean spatial firing rate; the symbols <…> indicate averaging over trials and time. The coefficient of determination estimates how much of the variance in the spatial video response can be accounted for by the response to the full field video. These values are plotted in Figure 6C for the cell sample and are generally over 50% (mean MC 55.2%, S.D.. 16%; mean PC 56%, S.D. 9%; mean S-cone 69% S.D. 9%). For MC cells, there is a significant effect of separation on the coefficient of determination, with an intercept near 66%. These coefficients are very high, indicating that center-surround spatial interactions have little influence on the ganglion cell signal.

The steeper slope of the linear relation for MC cells in Figure 6A is consistent with their strongly band-pass temporal response, which concentrates response energy into a higher spatio-temporal frequency band (as complex patterns drift across the retina, higher spatial frequency components drift at higher temporal frequencies). This effect is smaller with PC cells, which are more sustained. Thus the difference in regression slope in Figure 6A,B is consistent with the importance of temporal rather than spatial factors in response determination.

To summarize our analysis across cells, and across spatial and non-spatial stimuli, our evidence suggests that correlation of responses of cells of the same class with very similar receptive field locations is very similar to the correlation of repeat measurements on the same cells. Cells with opposite luminance responses, e.g., MC on- and off-center, cells show negative correlation coefficients. For PC cells, Lum on and off +L−M cells showed negative correlation coefficients, despite having opponent cone input of the same polarity, and this was also the case for +M−L cells. This indicates that luminance changes play a major role in determining responses compared to the L−M signal, due to the much greater luminance contrast in the video compared to the |L−M| signal (Fig. 1). This indicates that |L−M| chromatic signals must be extracted from PC signals in the face of background luminance responses (see discussion). Finally, the correlation analysis indicates that temporal factors are important in determining the structure of cell responses, rather than spatial structure in the video per se.

Coherence rate estimates

If spatial structure per se was critical to neuronal responses, the presence of spatial structure in the stimulus might increase the information rate of ganglion cells. To assess this possibility, and to make our results comparable to an earlier analysis (van Hateren et al., 2002), we calculated coherence rates for the spatial stimulus, using the same procedure. Coherence rate is an estimate and upper bound of Shannon’s information (bit) rate, and is derived from the frequency-dependent signal-to-noise ratio of a cell’s response. Values close to 1 indicate a large signal contribution, while values close to 0 indicate a dominant noise contribution (see methods). From the coherence, one can calculate the coherence rate by integrating across frequency, which provides a bound on the maximum information transmission in a noisy channel. The term coherence rate, rather than bit rate, is used, since neither signal nor noise is Gaussian. For a subsample of the cells, measurements of coherence rate to both spatial and full-field stimuli were obtained.

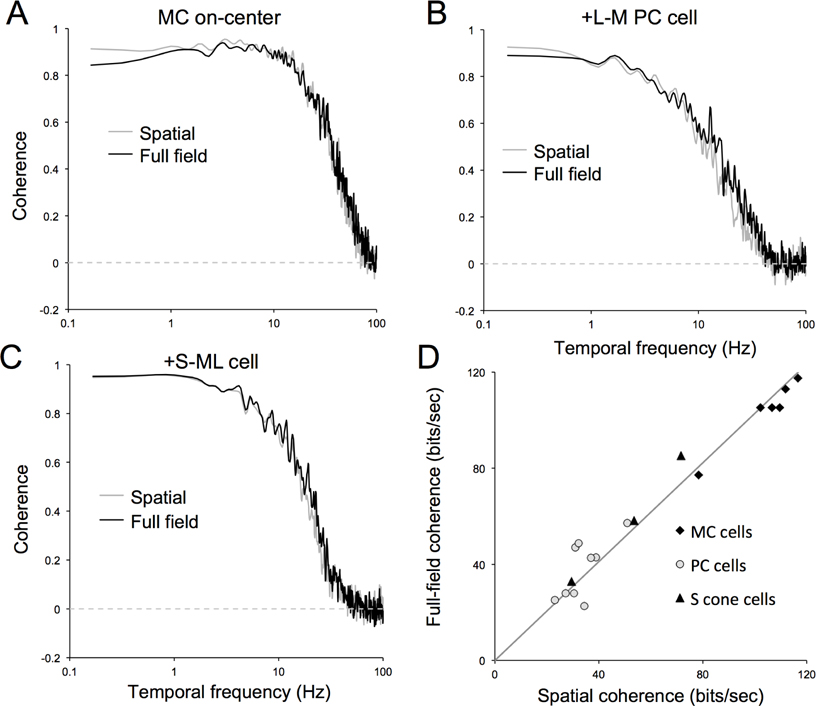

A comparison of coherence as a function of temporal frequency for spatial and full-field stimuli are shown in Figure 7A–C for an MC, a PC cell and a S-cone cell. Coherence functions for all cells are low-pass in shape. The curves for the two conditions are very similar for all cells. For the MC cell, coherence falls off toward 70 Hz and for the other two cells at 30–40 Hz. These frequencies are comparable to the high-frequency response cutoff for these cell types. Bit rates obtained by integrating over the coherence curves were also very similar for spatial and full-field stimuli (111.9 and 112.9 bits/sec for the MC cell, 37.0 and 42.7 bits/sec for the PC cell, and 53.4 and 58.2 bits/sec for the S-cone cell, for spatial and full-field conditions. A comparison of coherence rates for those cells tested with both stimuli is show in Figure 7D. The least-squares regression line through the origin does not differ significantly in slope from one (slope 1.027; S.D. 0.112).

Figure 7. Coherence measurements across cell types and stimuli.

A-C. Coherence as a function of temporal frequency for typical examples of MC, PC and S-cone cells. Cells selected were those for which coherence for both the spatial and full-field videos were available. Similarity between the curves is obvious. Curves for MC cells show a low-pass shape to a extending to a greater frequency than the PC and S-cone cell (MC cell drops to 0.5 coherence at 35 Hz, PC cell 16 Hz, S-cone cell 18 Hz). D. Comparison of coherence rates (coherence integrated over temporal frequency) for spatial and full-field videos reveal a close correlation with slope close to one.

For the whole cell sample, mean coherence rates for the spatial stimulus were 93.4 (S.D. 20.4), 36.2 (S.D. 16.1) and 44.2 (S.D. 20.2) bits/sec for MC, PC and S-cone cells respectively. These are similar to mean rates for the full-field stimulus (98, 35, 55 bits/sec respectively (van Hateren et al., 2002)). This would suggest that introducing spatial structure to the stimulus did not increase information rates in cell responses. Some further implications of these coherence rate estimates are taken up in the discussion.

Cell response models

Since retinal responses to the video were consistent with published data using simpler stimuli, we next considered whether one can construct a descriptive biophysical model for responses, based on known retinal mechanisms, such as illumination and contrast gain control circuits. The models are sketched in Figure 8A and details of the model are given in the methods section. These models were then provided with the stimulus video as input to determine simulated responses that we compared to ganglion cell responses. Spatial (i.e., receptive field location, center and surround radii) and temporal parameters were optimized to maximize correlation between cell and model responses for a representative set of ganglion cells. Figure 8B,C show sample fits for 1 sec of response for typical MC on- and off center cells. Most features of cell responses are captured; correlation coefficients between cell and model were 0.806 (S.D. 0.010) across all MC cells. The pie charts describe the distribution of response variance among various factors. In previous sections, we have stressed that temporal rather than spatial structure in the video was evident as the major drive for cell responses. To assess this division of labor, we modeled MC cells either with or without a surround mechanism. The pie chart shows that most response variance can be accounted for by the center response, with the surround playing only a minor role. Since the response was derived from 6 video repeats, we could also estimate variance associated with trial-to-trial variability. The remaining slice of the pie represents variance not captured by the model. Modeling of other MC cells also yielded good fits.

Figure 9 shows sets of data for three cone opponent cells. Again, most features of the data are captured by the model. In order to assess the role of center-surround structure on responses, the opponent mechanisms were set to the same radius, to provide the equivalent of a Type II receptive field structure. Again, the surround contribution to the response appears to be minor.

Across all cells, the models performed slightly better for PC cells (average r=0.810 ± 0.038 (S.D.)) than for MC cells and blue-on (both average r=0.806 ± 0.010 (S.D.) and r=0.776 ± 0.020), with a grand average of r=0.801±0.032, while all three approached retinal reliability. We also found biophysical model and receptive field estimates from reverse correlation consistent to within 1–2 pixels and consistent with cell type. It should be noted that reverse-correlation estimation of receptive fields is difficult in the presence of both non-linearity and non-Gaussian statistics (Sharpee et al., 2008; Sharpee, 2013), but also non-symmetric stimuli (Lesica, 2008). This agreement validates the regularized reverse-correlation approach.

To illustrate the differences between the three cell-types, we provided the full video with a dense array of ganglion cells and generated a movie of the pattern of responses. Frame-by-frame examination yields an impression of the pattern of cell responses. As expected, MC-on and MC-off cells responses appear out of phase (Suppl. Videos 1,2), while red-on and green-on PC cell responses are similar (Suppl. Videos 3,4), as they are mostly luminance driven when provided with naturalistic inputs, and considerably more sustained than MC cell responses. Both pathways exhibit similar, and higher spatial resolution in comparison to blue-on (Suppl. Video 5).

To summarize the model section, we constructed a biophysical model that allowed us to disentangle spatial from temporal contributions to the retinal response. In this model, we found temporal factors considerably more important, and the role of space was constrained to RF location, and center size with only minor contributions of the surround. The surround accounted for only few percent of variance across cells, much smaller than trial-to-trial variation (~20% of variance). This finding further supports the importance of temporal over spatial factors, consistent with the high degree of similarity between responses to full-field and spatial videos.

Discussion

The experiments presented here measured responses of macaque ganglion cells to natural scenes using a movement pattern intended to mimic that provided by eye and head movement in humans. We interpret our results as favoring the idea that the temporal pattern of stimulation as the eye moves across a scene is more important in determining responses than spatial context per se. This is not a new idea (Nothdurft & Lee, 1982b; Pitkow & Meister, 2012) but we back up this suggestion by a detailed analysis of cell responses, coherence estimates and a modeling approach describing cell responses. To paraphrase a previous title, time rather than space, is what ganglion cells really care about (Enroth-Cugell & Shapley, 1973), although we would stress that RF location and center size are spatial filters which critically determine responses. However, the contrast with V1, where spatial filtering is critical, e.g., for orientation specificity, is striking. Also, our results relate to the idea that temporal modulation (i.e., eye or head) movements help reduce redundancy of the retinal signal, as mentioned in the introduction. This is a complex issue that we assess further in the next sections.

The stimulus and eye movements

The camera shifts in the stimulus video are only an approximation of the rich pattern of eye movements, which include saccades of various types. Modeling studies (Donner & Hemilä, 2007) suggested that microsaccades help visual acuity. However, other evidence has been more ambiguous (McCamy et al., 2014; Mostofi et al., 2016). In any event, the importance of fixational eye movements in various aspects of spatial vision has received considerable support (Casile et al., 2019; Intoy & Rucci, 2020). Indeed, the importance of subjective (eye and head) movement in perception has long been recognized (Gibson, 1954), as has specificity of gaze shifts (Yarbus, 1967). More recent work in human subjects has made these earlier suggestions subject to precise experiments (Matthis et al., 2020).

Movement in the video exhibited gaze shifts across all scales, including slow drifts and high-frequency tremor (cf. Fig. 1F), but the average values of motion were similar to those for fine foveal vision, around 30 arcmin/sec (Kuang et al., 2012; Intoy & Rucci, 2020). When freely viewing natural pictures, this doubles to ~120 arcmin/sec (Aytekin et al., 2014). Our recordings were obtained from parafoveal retina (mean eccentricity 8.4 degrees), where center diameters are ca. 4 times larger than in the fovea (Lee, 2011). The measured distribution of velocities in our stimulus (cf. Fig. 1C) peaks around 300 arcmin/sec. Thus, in terms of velocity relative to receptive field size, our stimulus video was therefore intermediate between that found in free viewing (Aytekin et al., 2014) and with the head fixed (Kuang et al., 2012). It should also be noted that freely moving subjects, e.g. walking along a forest path, can exhibit considerably higher scene movements, with velocities exceeding ~250 deg/sec, compared to humans just viewing a natural scene (Matthis et al., 2020). In recording the video, there was an attempt to sequentially focus on different floral regions, but this may not have adequately mimicked normal viewing. Also, an observer with a stable head viewing small targets in a psychophysical experiment might show further differences in eye movement pattern. This makes it difficult to specify a ‘natural’ eye movement pattern. Nevertheless, our frequency content captures the phenomenology of human and primates exploring the natural world, while positioning itself on the more conservative side, containing only mild temporal fluctuations.

Recordings

Our recordings were obtained from the retina in vivo. RGC responses can be obtained in vitro using electrode arrays, usually from peripheral retina. Apart from the physiological environment, a key difference is in optics. Comparing retinal illuminance between in vivo and in vitro preparations is difficult. Recordings with the whole-mount preparation have noted that (judging from cell responses) retinal illuminance was much lower than expected from quantal flux (discussed in Smith et al. (2008)). In vivo, the cone outer segments point toward the pupil. In far peripheral retina, outer segments tilt well away from a perpendicular to the pigment epithelium to achieve this. In the whole-mounted in vitro preparation, light reaches the retina perpendicular to the pigment epithelium (i.e., at a substantial angle to the outer segment). The Stiles-Crawford effect strongly restricts the effectiveness of light entering the cone outer segment off-axis, so this makes effective illuminance in vitro uncertain. With an inverted retina, light enters from the photoreceptor side (Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002), so that other factors such as outer segment disorder might also contribute.

Although recordings in vivo profit from high stability and the ability to record from near the fovea, simultaneous recordings are not possible. These techniques are therefore complimentary. In vitro studies can provide insights across populations, their geometrical arrangements, and population activity and this can constrain cortical models (Schottdorf et al., 2014). In vivo data is well suited to better understand the physiological basis of foveal vision with intact optics. Other instances where our data deviates from in vitro recordings are discussed in the modeling discussion.

Receptive fields and responses

The reverse correlation profiles in Figures 2–3 resemble classical receptive field structures. Such comparisons must be undertaken with care, since the stimuli were not Gaussian in spectral distribution. However, we would stress several features of these response maps. Firstly, surrounds were poorly expressed. This is a common finding, from the earliest measures of cell responses to moving scenes (Nothdurft & Lee, 1982a) to a variety of later work (Dan et al., 1996; Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Pitkow & Meister, 2012). Secondly, the peak diameter for the luminance response of MC and PC cells was very similar, with restricted scatter; this diameter represents center size. We emphasize this point since the data of Croner and Kaplan (1995) are often used in modeling for center sizes of these cells (e.g., (Pitkow & Meister, 2012)). However, their MC data were derived from a very small cell sample. Other work (reviewed in Lee (2011)) has uniformly found similar sizes in central retina. Center sizes in our data do not vary much compared to many earlier studies (e.g., Derrington and Lennie (1984), Fig. 6), where scatter of center radii is almost a log unit, but here it is less than a factor of two. This is likely due to the dense spatial sampling inherent in the natural scene video providing more reliable center size estimates.

A weak surround was usually apparent. This was often surrounded by a further, very weak disinhibitory region. Extraclassical receptive field effects in the retina have frequently been reported, first in the cat (McIlwain, 1966; Passaglia et al., 2001), and in primate MC cells (Solomon et al., 2006). However, such effects often have a non-linear basis and might be poorly captured by reverse correlation analysis.

Surrounds were weakly expressed in our data. Pitkow and Meister (2012) noted a similar result. However, some degree of center-surround organization is present in both MC and PC cells. In a recent study (Turner et al., 2018), MC cell center-surround interaction in peripheral retina in vitro were studied. They stimulated center or surround separately; some response peaks were center and some surround related. This could be reproduced with our model (data not shown), but with fewer surround transients. In any event, for our data the weak surround expression could have other causes. MC cells are very band-pass in their temporal response. With a moving natural scene, higher spatial frequency components move at higher temporal frequencies. These factors combine to concentrate MC cell response energy to higher SFs. These are not resolved by the surround, so it is only weakly expressed; this issue has been specifically addressed in a model of cell responses to complex waveforms, e.g., square waves (Cooper et al., 2016). For PC cells, although cone balance of center/surround is almost equal (Derrington et al., 1984), center-surround structure is often weak, as in the early Type I/Type II classification (Wiesel & Hubel, 1966; Lee et al., 2018). These factors may contribute to the weak surround expression in natural scene responses.

Reverse correlation of the PC cells with the |L−M| video component yielded response fields consistent with the polarity of the L,M cone inputs based on cell classification (+L−M or +M−L). However, these response maps were noisier than those derived for luminance, as were impulse response functions, since the mean luminance contrast in the video was ca. 20 times the |L−M| contrast. A noisier signal for color has been predicted on a theoretical basis (MacLeod & Twer, 2003). The spatial width of response peaks for the |L−M| maps (compared to a cell’s luminance map) was variable. This is again consistent with previous reports that PC cells display a spectrum of receptive field structures, from Type I (center-surround) to Type II (opponent cone mechanisms of similar size). The diameters of S-cone responses of excitatory S-cone cells were similar, although the sample was small.

The time course of cell responses was consistent with that expected at low-to-mid photopic levels (Lee et al., 1994). Responses of PC cells were a few milliseconds slower than those of MC cells, and their chromatic responses were less biphasic than their luminance responses. In the primate literature, results about ON/OFF asymmetries have been mixed (Benardete & Kaplan, 1999; Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Reid & Shapley, 2002). A faster response time course for MC on-center cells, relative to off-center cells, was reported from in vitro measurements by Chichilnisky and Kalmar (2002) but others (Reid & Shapley, 2002) found any difference to be in the opposite direction. Time courses in our data were very similar to those of Reid and Shapley (2002), but on cells were faster than off cells, although differences were small, in the millisecond range. However, we would stress that the time course of our MC-cell responses was much faster (time to peak 25 msec) than the in vitro measurements (time to peak 50 msec) (Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002), and our responses appeared significantly more biphasic. Both these differences might be associated with a lower effective retinal illuminance in the in vitro data, as discussed above. This makes comparison difficult. We also found slightly larger MC on than off centers, 6.80 vs 6.44 minutes of arc on average, but this difference was not significant.

Cell models

Our cell modeling accounted for a large proportion of the variance of cell responses. The model used was similar to previous approaches (van Hateren et al., 2002), with the addition of spatial receptive field structure. The model provided a good account of the data. While it required non-linearities such as contrast gain and luminance adaptation, spatial nonlinearities were not evident. Natural images can be reconstituted from ganglion cell responses in primate retinae (Brackbill et al., 2020), which also implies spatial linearity, although their study was limited since they used flashed, grey scale images. Our models also showed that, beyond position and size, spatial receptive field structure does not sculpt the firing pattern. This is quite different from cortical areas where, for example, spatial filtering gives V1 cells oriented receptive fields.