Abstract

Background

Research to date has suggested that religion might be a source of comfort and strength in times of crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it may also be a form of stress if spiritual struggles are experienced. We posit the discussion of religious and spiritual matters as a potential feature of religious life that may be helpful or harmful for dealing with the impacts of spiritual struggles.

Purpose

This study has two objectives. First, we assess the association between religious/spiritual struggles and both perceptions of psychological distress and self-rated health, affording attention to the prevalence of religious struggles during this time. Second, drawing from social penetration theory, we consider both the potential helpful and harmful role of discussing religion with friends and family members for the well-being of those experiencing various degrees of religious/spiritual struggles.

Methods

Using data from a nationally representative sample of Americans collected in January 2021, nearly a year after the onset of the pandemic (N = 1,711), we conduct a series of OLS and ordinal logistic regression models.

Results

Results suggest that religious/spiritual struggles were somewhat common among Americans during COVID-19 and were associated with greater psychological distress and worse perceived self-rated health during the pandemic. In the context of high R/S struggles, both psychological distress and perceived self-rated health were more favorable when religious and spiritual matters were discussed very frequently, several times a week or more. Unlike for psychological distress, however, we found no evidence that discussion of religious matters in the face of greater R/S struggles exacerbated their ill effect on health. Supplemental analyses showed that these findings are not being driven by religious denominational differences across our focal variables.

Conclusions and implications

Encouraged by discussions of faith with close network confidants, people experiencing R/S struggles might seek help in the form of counseling in both secular and/or religious settings. Exploring potential resilience factors, such as religious discussion, may help inform broader or more local strategies aimed at economic recovery. Our results therefore invite future investigation into the role of religious coping in mitigating the health effects of pandemic hardship.

Keywords: religious/spiritual struggles, Religious discussion, Perceived self-rated health, Psychological distress, COVID-19

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic upended daily life worldwide, infecting tens of millions of people and causing more than 5 million deaths to date as of December 2021. However, the pandemic had a much wider-reaching effect beyond the medical victims of the virus. The early months of 2020 witnessed immense changes to the entirety of social life, where many “normal” social behaviors underwent dramatic change in an effort to tame the spread of the virus. Though the COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding lockdown measures exacted a significant influence on all features of daily life, including work, school, and family routines, religious behavior was also affected by the pandemic in significant ways, not the least of which were the closing of churches and cancellation of live religious services.

In the months following the pandemic outbreak, there was an outpouring of scholarly work on religiosity and COVID-19. Bentzen (2020) noted a 50% increase in Google searches for topics related to prayer prior to the COVID-19 period, with searches nearly doubling for every 80,000 newly registered cases of COVID-19. What is more, nearly 25% of American adults reported that their faith had become stronger because of the pandemic (Gecewicz 2020), even despite overall decreases in religious attendance.

These recent research findings related to religiosity in the wake of the pandemic invite further reflection. The COVID-19 pandemic has taken an immeasurable toll on mental and physical health at the population level, due in no small part to the disruptions created by the lockdowns and social distancing measures (Bierman and Schieman 2020; Bierman, Upenieks, and Schieman 2021; Holingue et al. 2020; Van Bavel et al. 2020). Recent research has begun to explore the role of religion in responding to and coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Religious beliefs, practices, and ideologies have been found to be helpful for protecting well-being during the pandemic (Pirutinsky 2020; Schnabel and Schieman 2021). In the face of threatening situations that were inevitabilities of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., illness, death, fear of unemployment, social isolation), religion can be an effective resource for dealing with such difficulties by providing psychological as well as social support. Indeed, religion can furnish cognitive and psychological support through shared religious worldviews (Pargament 1997) and help to create a sense of certainty in the midst of chaos (Brandt and Henry 2012). Religion can also provide and strengthen social ties and religious communities where people find support (Ellison and George 1994; Lim and Putnam 2010). Through both of these pathways, religion is often thought to protect adherents from the detrimental physical and mental health consequences of stress.

But what if religion is the source of stress during these troubled times? Religious/spiritual (R/S) struggles are an example of the bittersweet nature of the religious experience, and reflect a spiritual tension characterized by a less secure relationship with God (e.g., feeling punished or abandoned by God), uncertainty in the tenets of one’s faith, or feelings of criticism or strain from co-religionists (Exline et al. 2014). Religious/spiritual struggles are known to be associated with negative coping (Hayward and Krause 2016), worse mental health (Ellison and Lee 2010; Exline et al. 2015; May 2018), lower physical health (Fenelon and Danielsen 2016; Upenieks 2021), and eventual mortality (Pargament and Exline 2021). No existing study, however, has sought to uncover the prevalence of spiritual struggles during the pandemic (Dein et al. 2020), nor considered any aspects of religious life that may be helpful in reducing the impacts to well-being from these struggles. As Exline and Rose (2013) have pointed out, how people deal with spiritual struggles or doubt is a vastly understudied area. The COVID-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to further explore the links between religious coping and well-being. Stressors do not affect all people in the same way because some individuals possess social and psychological resources that help them cope with the stressors they encounter. For one, the deleterious effects of stress are typically dampened for individuals with a strong social support system (Thoits 2010). However, researchers have been slow to identify coping resources that are well-suited for the task of quelling the negative health impacts of religious/spiritual/struggles.

This paper posits the discussion of religious and spiritual matters as a potential resource of religious life that may be well-suited for mitigating the health impacts of spiritual struggles. Despite the uncomfortable cultural connotations associated with “talking religion,” religion is a topic that just over 50% of American adults discuss with someone outside of the home, with the likelihood of such conversation increasing to 83% among those who see themselves as highly religious (Cooperman 2016). Americans also report discussing religion and spirituality with about half of their non-residential close relationships (Merino 2014; Schafer 2018). Talking about religious and spiritual matters may affect the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being in two ways; first, as a measure of intimacy and support, religious discussion might offer a way for people to work through any struggles they are experiencing, supported by their spiritual peers. Second, however, discussing matters of faith and spirituality when experiencing religious uncertainty and doubt could exacerbate the stress if these struggles are a source of stigma or judgment on the part of one’s discussants, making the health impacts more deeply felt.

Therefore, using data from a nationally representative sample of Americans collected in January 2021, nearly a year after the onset of the pandemic, this study has two objectives. We first assess the association between religious/spiritual struggles and both perceived physical health and psychological distress, and afford attention to the prevalence of religious struggles during this time. As a second objective, we consider both the potential helpful and harmful role of discussing religion with friends and family members for the well-being of those experiencing various degrees of religious/spiritual struggles. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of the study, which involves testing whether religious discussion moderates the association between R/S struggles and both forms of well-being.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Framework Linking R/S Struggles, Religious Discussion, and Well-Being

Religious/Spiritual Struggle and Well-Being

The last several decades have witnessed an explosion of research on the relationship between religiosity, health, and well-being (see Koenig et al. 2012; Page et al. 2020 for reviews). The majority of these studies were designed to assess the potentially beneficial ways in which greater religiosity promotes better mental and physical health. A smaller cluster of these studies, however, explored the potential downsides of greater involvement in religion, which Ellison and others have referred to as the “dark side” of religion (Ellison and Lee 2010). Work on the dark side of religion is often cast under the broad rubric of “spiritual struggles.”

R/S struggles can take many forms, including (1) divine struggles (feelings of abandonment or being punished by God), (2) interpersonal struggles (conflicts with family, friends, and others within one’s religious group about religious issues), or (3) intrapersonal struggles (doubts about the truth of one’s faith, or question about ultimate meaning or purpose in life) (Exline et al. 2014). Several studies have linked religious struggles to a range of adverse mental health outcomes, including anger, depression, and anxiety (Ellison and Lee 2010; Exline et al. 2015) as well as physical health (Mannheimer and Hill 2015; Upenieks 2021) and mortality (Pargament and Exline 2021). Notably, these patterns are remarkably consistent across all forms of religious struggle.

Major life crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have the potential to shake people not only psychologically, socially, and physically, but religiously and spiritually as well. Stressful events like the pandemic could foster a view of the world as fundamentally chaotic and unsafe (e.g., Janoff-Bulman 1989). Although data surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic on this matter are lacking, other studies have demonstrated robust links between stressful life events and a greater prevalence of R/S struggles (Wortmann, Park, and Edmondson 2011; Stauner et al. 2019). For example, in a representative study of adults from the United States, greater exposure to major life events was tied to more R/S struggles, which in turn predicted greater psychological distress (Pomerleau et al. 2021). It is important to underscore that people who experience more stressful life events tend to report more of all forms of R/S struggles, regardless of how personally religious they are (Stauner et al. 2019).

We might expect that the COVID-19 pandemic has (and continues to) trigger many of these profound and existential questions. Some people were likely grappling with, for instance, ways to reconcile their beliefs in a loving God with the extensive suffering that was engendered by the pandemic. In the only study to date conducted on this topic in relation to COVID-19, Lee (2020) found that higher levels of struggles with God were associated with higher anxiety about the coronavirus. If this is any indication, we would expect a fairly high prevalence of R/S struggles in the ensuing months after COVID-19 and an association between these struggles and both physical and mental health costs after the pandemic’s onset. Based on this body of evidence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

Greater R/S struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic will be associated with higher perceptions of psychological distress and worse self-rated health.

Despite the establishment of strong theoretical links between R/S struggles and well-being, significantly fewer studies have investigated what may moderate the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being during a religious strain experience (Zaezycka and Zietek 2019). One potential candidate for modifying the relationship between R/S struggles and physical and mental well-being is social support, of which religious discussion could be part and parcel of. Social support has been conceptualized as the flow of information, instrumental assistance, and emotional concern within social networks (Berkman and Glass 2000; Hartwell and Benson 2007). Religious discussion may be an especially important form of social support to guide individuals through religious struggles and shield them from declining health. However, talking about religious/spiritual matters when it is exactly these topics that are the cause of great angst could also be a risky endeavor that makes people feel a heightened sense of vulnerability or stigma for having doubts about their faith during a time when perhaps faith is needed the most. We outline these possibilities in the following sections.

The Helpful (or Harmful) Role of Religious Discussion When Confronting R/S Struggles

For many Americans, faith provides a lens through which most matters of importance are approached. A health crisis on the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic seems tailor-made for employing methods of religious coping, but even at a more basic level, for discussing R/S matters in an effort to make sense of changing social circumstances. Yet, the religiosity of Americans was up against a dauting challenge during the pandemic, as the comfort that religion provides during tumultuous times is often premised on congregating in religious communities, which was banned due to social distancing protocols in many states. For these reasons, it is essential that we look at more private dimensions of religiosity—including discussing religion with family members and close friends—and how it may shape the relationship between spiritual struggles and physical and mental health. The intimacy involved in discussing religious or spiritual matters is “simultaneously rewarding and risky” (Collins and Miller 2012:469), and the costs of delving into religion when confronted with spiritual struggles could improve or exacerbate any costs to health and well-being associated with uncertainties about one’s faith.

Religious Discussion May be Helpful

R/S struggles tend to arise when a person is unable to identify a plausible reason for the pain and suffering that has been inflicted upon their life. Overcoming struggles which stem from that which cannot be immediately grasped may require assistance from others in order to achieve a deeper understanding. Therefore, religious discussion may be an avenue leading to the perspectives, knowledge, and wisdom of close others to cope with these spiritual challenges. Some Christian theologians (e.g., Snowden 1916; Tillich 1957) have argued that struggles with one’s faith are inevitable and may actually play a constructive role in personal spiritual development, eventually producing a stronger, deeper faith.

Sensitive matters such as religion may often be discussed only with one’s trusted confidants, or “strong ties” (Small 2013). Mark Granovetter (1973:1361) famously defined a tie’s strength as some “combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie.” Frequently discussing religious/spiritual matters with emotionally close others when one is personally experiencing struggles with faith might buffer the pernicious health effects of spiritual struggles, weakening correlations between them and any negative consequences for health and well-being.

Support for this assertion may be found in the auspices of social penetration theory, which offers a developmental account of relationships (Altman and Taylor 1973). Social penetration theory asserts that people have layers of beliefs, values, and commitments that are slowly peeled back and revealed to other persons over time, with the inner core opening only after conversation has moved beyond the more outer (superficial) layers. According to this theory, then, people open up about sensitive matters only when they believe that the “rewards” of this intimacy will outweigh the costs. Therefore, once a person believes they have developed sufficient rapport and trust with another person, they may come to anticipate that greater social penetration will be a rewarding experience.

Social penetration processes have an important affinity with discussions surrounding religion and spirituality. Religious/spiritual concerns are of ultimate or sacred significance. For devout believers, dialogue about religion is a “central, intimate facet of personality” because it touches on issues of personal vulnerability (Altman and Taylor 1973:58). Religion could therefore be a discussion topic that is the marker of a strong, emotionally close bond between people. Using longitudinal data, for instance, Schafer (2018) found that talking about religion with a member of one’s close social network was associated with a greater likelihood of that person remaining in that person’s close network five years later. Discussion about religious/spiritual matters could therefore be a unique form of social support that might be especially valuable for the well-being of those trying to work through the stress posed by faith-related struggles. People often perceive that they have grown spiritually in response to struggles, especially if they engage in positive religious coping methods such as perceiving that they are working together with God to overcome them (Desai and Pargament 2015; Exline, Hall, Pargament, and Harriot 2017) or if one sees God as intervening to help them address their struggles (Exline et al. 2017). Growing from struggles is crucial for well-being, as Wilt and colleagues (2017) documented that people who experienced higher spiritual growth and derived greater meaning through their struggles reported lower depression and anxiety.

Though extant research has not explicitly theorized the health-protective effects of religious discussion in the midst of spiritual struggles, social support processes are likely to be involved. Discussing religious/spiritual struggles during the pandemic likely reveals a great degree of personal expression and self-disclosure, signaling a trusting relationship (Greene, Derlega, and Matthews 2006). This may condition the flow of social support resources in the face of uncertainty. Indeed, Merino and colleagues (2014) find that religious discussion was one of the strongest predictors of social support, as help provision was more than twice as likely to come from someone that an individual reported having discussed religion with. Studies have consistently extolled the benefits of social support (Berkman and Glass 2000; Cohen and Willis 1985; Uchino 2006) and the dangers of social isolation (Cacioppo and Hawkley 2003) for physical and mental health. On one hand, individuals who are socially isolated when religious/spiritual struggles occur may have only their own internal resources to help them cope with these uncertainties. Without confidants to help them work through spiritual struggles, one might overwhelm their personal coping resources, leading to stronger R/S struggle and further declines to health.

Considered as a whole, this body of evidence on R/S struggles and social support suggests that in the process of discussing religion with close family and friends, individuals may find a useful coping resource to mitigate any detrimental effects of R/S struggles on well-being. Family and friends have likely also experienced R/S struggles of their own during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conversations about faith may help reinforce or advocate the message, that notwithstanding any struggles experienced, a divine power has a “greater plan” that may have included the COVID-19 pandemic. The opportunity to discuss such matters with others might promote optimism about the future and may be linked to better physical and mental health. Discussing such struggles with others may reinforce the idea that one is not alone in doubting their faith or feeling abandoned or punished by God. Religious discussion could therefore act as a resource inasmuch as it promotes a quicker resolution of R/S struggles and minimizes the relative impact it has on mental and physical health (e.g., Upenieks 2021). Based on this body of work, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

More frequent discussion of religious/spiritual matters with family members and close friends will be associated with higher perceptions of psychological distress and worse self-rated health for those experiencing greater R/S struggles.

Religious Discussion May be Harmful

Although religious discussion may be a source of comfort and support for those experiencing R/S struggles, another possibility is that the practice of religious discussion could be harmful for the health and well-being for those facing these struggles during the coronavirus pandemic. In fact, discussion of religious/spiritual matters could be encountered as yet another religious obstacle for the reasons outlined below.

The greater intimacy that is generally required to discuss religious/spiritual matters may also come with hefty costs. If individuals share their doubts or struggles with others, they may run the risk of being criticized or ostracized for having a blemish in their faith. In this way, then, R/S struggles could be a source of social stigma or embarrassment. According to the theory of Charles Horton Cooley (1902/2003), an individual’s sense of self-worth is determined by feedback received from close others. If a person is having doubts or struggling with their faith, then any real or imagined disapproval by others may affect their health and mental health accordingly. It is possible that in the course of conversation involving religious/spiritual matters, the discussant might mention divine punishment for their lack of faith (Exline and Rose 2013). For instance, it is stated in the Book of St. James (1:6, ESV): “for the one who doubts is like a wave of the sea that is driven and tossed by the wind.” Being reminded of such literal interpretations of scripture may produce significant internal discomfort and be a source of stress that undermines health.

Negative interactions with co-religionists are also a source of R/S struggle and may undermine well-being (Krause and Ellison 2009). Choosing to discuss difficult matters of faith with co-religionists might therefore further exacerbate any ill effects already attributable to R/S struggles. By expressing uncertainty in one’s faith, the flow of social resources and support might be extinguished when the standards of faith are not perceived to be upheld. When individuals admit doubt in their faith or come to hold controversial perspectives constitutive of negative religious coping (e.g., believing that God has abandoned you, attributing religious/spiritual struggles to divine punishment, feeling negativity toward church members of the clergy) (Pargament, Smith, and Perez 1998), they could be ostracized by the religious community. Holding contentious beliefs and interpretations and doubts and failing to meet the standards of faith communities could lead to criticism from co-religionists and family and friends (Ellison and Lee 2010; Hill and Cobb 2011). For those experiencing spiritual struggles, “talking religion” more frequently could be perceived as a communication of inadequacy for having doubts or not fully trusting God in the incredible stressful times of the pandemic.

Under conditions of unfavorable interactions with co-religionists, the structural basis for social support is undermined, and processes of shame, criticism, and ostracism could worsen the already vulnerable health profiles of those experiencing R/S struggles. One prior study found that discussing religion with a greater proportion of one’s network ties was associated with higher depression, an effect which was magnified for those placing less importance on religion (Upenieks 2020). Upenieks (2020) speculated that for those not holding religion to be of great import, discussing religious or spiritual matters could be a form of “unsolicited social support” (Song 2014) that is ripe with judgment or criticism for low religiosity on the part of network members. Based on this evidence, we therefore present the following alternative hypothesis for how religious discussion might condition the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being:

Hypothesis 3

More frequent discussion of religious/spiritual matters with family members and close friends will be associated with higher perceptions of psychological distress and worse self-rated health for those experiencing greater R/S struggles.

Data and methods

For this investigation, we use data from the 2021 Crime, Health, and Politics Survey (CHAPS). CHAPS is based on a national probability sample of 1,771 community-dwelling adults aged 18 and over living the United States. Respondents were sampled from the National Opinion Research Center’s (NORC) AmeriSpeak© panel, which is representative of households from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Sampled respondents were invited to complete the online survey in English between May 10, 2021 and June 1, 2021. The data collection process yielded a survey completion rate of 30.7% and a weighted cumulative response rate of 4.4%. The weighted cumulative response rate is the overall survey response rate that accounts for survey outcomes in all response stages, including the panel recruitment rate, panel retention rate, and survey completion rate. It is weighted to account for the sample design and differential inclusion probabilities of sample members. Our cumulative response rate is within the typical range of high-quality general population surveys (4–5%). See Pew Research, for example (https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/05/17/scope-of-government-methodology/).

The multistage probability sample resulted in a margin of error of ± 3.23% and an average design effect of 1.92. The median self-administered web-based survey lasted approximately 25 min. All respondents were offered the cash equivalent of $8.00 for completing the survey. The survey was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at NORC and one other university review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The primary purpose of CHAPS is to document the social causes and social consequences of various indicators of health and well-being in the United States during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

Post-stratification weights were used is subsequent analyses to reduce sampling error and non-response bias. NORC developed post-stratification weights for CHAPS via iterative proportional fitting or raking to general population parameters derived from the Current Population Survey (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data.html). These parameters included age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and several interactions (age*sex, age*race, and sex*race).

Dependent Variables

Two outcome variables were assessed in the current study: perceptions of psychological distress and perceived self-rated health.

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was assessed with a six-item scale taken from the K6 psychological distress scale (Kessler et al. 2002). Respondents were asked to report how often, in the last 30 days, they felt, (1) “nervous,” (2) “restless or fidgety,” (3) “that everything was an effort,” (4) “hopeless,” (5) “so sad that nothing could cheer you up,” and (6) “felt worthless.” Response options were coded where 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Rarely, 3 = “Sometimes,” 4 = “Very often,” and 5 = “Always.” Responses to the six items were averaged to form a scale (alpha = 0.93), with higher scores representing greater psychological distress.

Self-Rated Health

Self-rated health was assessed with a one-item measure gauged by the question, “How would you rate your overall health at the present time?” Responses were coded where 1 = “Poor/Fair” (combined to achieve adequate sample size), 2 = “Good,” 3 = “Very good,” and 4 = “Excellent.” A five-category measure of self-rated health has been shown to be a valid and reliable assessment of individuals overall health status and has been widely used in previous research on individuals’ health (Ferraro and Farmer 1999; Idler and Benyamini 1997), even, in some cases, exceeding the predictability of physician assessment (Ferraro and Farmer 1999).

Focal Independent Variables

Religious/Spiritual Struggles: Four items were used to assess the extent to which respondents experienced R/S struggles (see Idler et al. 2003; Pargament et al. 2000). These were as follows: (1) “How often do you have doubts about your religious or spiritual beliefs? (2) “How often do you feel judged or mistreated by religious or spiritual people?” (3) How often do you feel as though God has abandoned you?” and (4) “How often do you feel as though God is punishing you?” Responses were coded according to the following scheme: 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Rarely,” 3 = “Sometimes,” 4 = “Very often,” and 5 = “Always.” Responses to these four questions were averaged and combined into a scale with higher scores indicating greater R/S struggles (alpha = 0.73), though supplemental analyses considered each dimension of religious/spiritual struggles separately. All four items of the R/S struggle scale were only weakly correlated with religious discussion (correlations ranged from r = -.01 to r = -.05), assuaging concern that strong correlations with the religious discussion variable (which it is eventually interacted with) could produce confusing results.

Religious Discussion: In the CHAPS data, religious discussion was measured by the following question: “How often do you discuss religious or spiritual matters with your friends or family members?” Responses were initially coded into seven categories, but the final four-category variable used for analyses is as follows to ensure adequate cell size among groups: 0 = “Never,” 1 = “Less than once per month,” 2 = “Once a week or less,” and 3 = “Several times a week or more” (hereafter, referred to as biweekly).

Religious Covariates

To ensure that any relationship between R/S struggles and well-being, and any moderating role of religious discussion is not confounded by other indicators of religiosity, especially any (temporary) changes in religiosity that might have been spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic, we adjust for the following covariates.

First, we include a measure of change in religious attendance. Respondents were asked, “During the coronavirus pandemic, have you attended church meetings in person more often, less often, or about the same frequency as before the pandemic? Answer options were as follows: 1 = “Attended more often” [reference group], 2 = “About the same as before the pandemic,” 3 = “Attended less often.” We also incorporated a measure which captures whether the subjective importance of religion in one’s life changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, “Has the importance of religion in your life changed during the coronavirus pandemic?” Response options were 1 = “Religion has become more important,” 2 = “About the same as before the pandemic,” and 3 = “Religion has become less important.”

Finally, we also include a measure of religious affiliation using a modified version of the commonly employed RELTRAD variable (Steensland et al. 2000). We therefore contrast Conservative Protestants (those who reported being Protestant and evangelical/born again, reference group) with Mainline Protestants, Catholics, Other Christian (Mormons, Orthodox), Other Religion (non-Christians, such as Jewish people, Buddhist, and Muslims, collapsed into one category because of small cell sizes), and Religious Nones (no religious affiliation, including atheists and agnostics). Conservative Protestants were chosen as the reference group because they typically discuss religion more with their network members (Schafer 2018).

Demographic Covariates

Several demographic covariates were also included in our analysis. We included a four-category measure of age: 18–29 years of age (reference group), 30–44 years, 45–49 years, and 60 years and older. Race was measured by a four-category variable as well, where White, non-Hispanic served as the reference group, compared to Black, non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Other Race. Female was coded as 1. Marital status compared those who were married to those who reported being widowed, divorced, separated, never married, or living with a co-habiting partner. Educational attainment was a five-category variable, coded where 1 = Less than high school [reference group], 2 = High school graduate or equivalent, 3 = Vocational/tech school/some college/associate degree, 4 = Bachelor’s degree, and 5 = Post grad study/professional degree. Personal income was coded as a four-category variable, comparing those with an income of $30,000 or less with those earning $30,000-$60,000, $60,000-$100,000, and $100,000 or more. We also include a binary variable indicating whether a respondent had been unemployed because of the COVID-19 pandemic as a measure of potential economic hardship. Finally, a variable indicating the region of residence for respondents (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) was featured, as COVID protocols and restrictions were not uniform across the United States and because religious discussion might be more common in certain parts of the country (e.g., American South).

Plan of analysis

The relationship between R/S struggles and mental health is evaluated with ordinary least squares regression (OLS) with robust standard errors. Analyses taking physical health as the outcome are estimated using ordinal logistic regression, with 95% confidence intervals shown. Brant tests conducted for all models related to self-rated health reveal that the parallel lines assumption was not violated for our variables of interest (R/S struggles, religious discussion), making an ordered logit multilevel model appropriate. Listwise deletion was used as the method to address missing data, as less than 5% of all cases had data missing on focal study variables. This procedure yielded 1,711 cases for analyses. Results are also robust if multiple imputation with chained equations were used to handle missing data.

Analyses for both mental and physical health proceed in an identical series of three models. In Model 1, the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being is assessed to establish the baseline association between these struggles and health during the COVID-19 pandemic. This serves as a test of Hypothesis 1. Model 2 then adds the measure of religious discussion to the fold, to establish its baseline association with well-being and whether its addition alters the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being. Finally, Model 3 tests the interaction term between R/S struggles and the frequency of religious discussion, serving as a test of Hypotheses 2 and 3, whether religious discussion buffers or exacerbates the harmful effects of R/S struggles on mental and physical health.

Results

Before proceeding to document the results of the multivariable analyses, a series of key descriptive statistics are highlighted to provide a sense for the extent of R/S struggles, religious discussion, and health and mental health problems in the early months of 2021. All unweighted descriptive statistics for the sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unweighted Descriptive Statistics, CHAPS Project (N = 1,711)

| Mean/% | S.D. | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Psychological Distress | 2.29 | 0.94 | 1 | 5 |

| Self-Rated Health | ||||

| Poor/Fair | 20.69 | |||

| Good | 41.61 | |||

| Very Good | 30.22 | |||

| Excellent | 7.48 | |||

| Focal Independent Variables | ||||

| Religious/Spiritual Struggles (index) | 1.89 | 0.74 | 1 | 5 |

| Religious Discussion | ||||

| Never | 21.34 | |||

| Less than once a month | 31.98 | |||

| Once a week or at least monthly | 25.13 | |||

| Several times a week or more | 21.56 | |||

| Control Variables | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 years | 13.83 | |||

| 30–44 years | 29.08 | |||

| 45–59 years | 22.59 | |||

| 60 years or older | 34.50 | |||

| Race | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 67.31 | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.67 | |||

| Hispanic | 16.49 | |||

| Other Race | 5.53 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0.47 | |||

| Female | 0.53 | |||

| Educational Attainment | ||||

| Less than high school | 4.27 | |||

| HS graduate or equivalent | 16.45 | |||

|

Vocational/tech school/some college/ Associate degree |

43.53 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 21.40 | |||

| Post grad study/professional degree | 14.34 | |||

| Income | ||||

| $30,000 or less | 22.25 | |||

| $30,000 -$60,000 | 28.57 | |||

| $60,000 to under $100,000 | 27.16 | |||

| $100,000 or more | 22.02 | |||

| Unemployed due to COVID-19 | 0.20 | |||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 54.21 | |||

| Widowed | 4.12 | |||

| Divorced | 10.56 | |||

| Separated | 3.90 | |||

| Never married | 21.40 | |||

| Living with partner | 5.82 | |||

| Region of United States | ||||

| Northeast | 14.46 | |||

| Midwest | 27.61 | |||

| South | 33.43 | |||

| West | 24.51 | |||

| Religious Controls | ||||

| Religious Attendance during pandemic | ||||

| Attended more often | 2.94 | |||

|

Attended about the same as before the pandemic |

51.19 | |||

| Attended less often | 45.87 | |||

| Change in Religious Importance during the pandemic | ||||

|

Religion has become more important |

17.76 | |||

| About the same as before pandemic | 76.22 | |||

| Religion has become less important | 6.02 | |||

| Religious Affiliation | ||||

| Evangelical Protestant | 22.76 | |||

| Mainline Protestant | 14.29 | |||

| Catholic | 18.52 | |||

| Other Christian | 14.91 | |||

| Other | 4.52 | |||

| No religion | 24.90 |

Note. Standard deviations are omitted for categorical variables

First, psychological distress scores had an average of 2.29 in the sample, with almost a 1-unit standard deviation (0.94) on a 5-point scale. What is more, over 20% of respondents reported poor or fair self-rated health, and only 7.48% of respondents reported having excellent health. Nearly three-quarters of the sample had good or very good health.

[Table 1 about here]

As for religious/spiritual struggles, the mean score on the R/S struggles index was 1.89 on a 5-point scale, with fairly substantial variation (SD = 0.74). While on the surface the presence of struggles may seem relatively uncommon, breaking this down by each item on the scale, 15% of respondents felt at least “sometimes” abandoned by God, 17% of respondents felt at least “sometimes” punished by God, over 35% felt judged by religious or spiritual people, and 32% in total felt at least “some” doubt toward that their religious/spiritual beliefs were accurate.”

With respect to religious discussion, our focal moderator, only 21.34% of respondents reported never having discussed religious/spiritual matters with close friends or family members. Nearly half the sample discussed religion at least monthly, with 22% of the sample discussing religion several times a week or more. We also obtained cross-tabulations to assess how religious discussion varied across levels of R/S struggles. For those experiencing low religious struggles (defined as 1 standard deviation below the mean on the R/S struggles index), 35.40% never discussed religious matters, while 25% discussed religion several times a week or more. At the mean level of R/S struggles, only 18% did not discuss religious matters with close friends/family members, while 23% discussed them several times a week or more, and 23% discussed them at least monthly. Finally, at one standard deviation above the mean in R/S struggles, 26% never discussed religion, while 42% discussed religion at least monthly. Based on these figures, it appears that more frequent religious discussion is slightly more common as religious struggles increase. However, spiritual struggles, as well as the propensity to discuss religious/spiritual matters, is almost surely confounded with personal religiosity (including religious affiliation) as well as sociodemographic characteristics, so the interactive influence of R/S struggles and religious discussion are more rigorously tested in regression models which include adjustments for several potential confounders.

Multivariable Regression Results

Psychological Distress

Results from regression analyses predicting psychological distress are shown in Table 2. In Model 1 of Table 2, greater spiritual struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with greater psychological distress (b = 0.45, p < .001), net of religious and demographic covariates. This coefficient for R/S struggles corresponds to nearly ½ of a standard deviation in psychological distress scores, suggesting a fairly substantial association between R/S struggles and distress in the era of COVD-19. This aligns with Hypothesis 1, which predicted that greater spiritual struggles would be associated with higher psychological distress. Several interesting patterns were also observed with respect to various demographic covariates and their associations with psychological distress during the pandemic in Model 1. For instance, respondents 60 years or older report lower psychological distress relative to respondents ages 18–29 (b = -0.68, p < .001). Black respondents also reported higher psychological distress compared to White respondents (b = -0.23, p < .01). Each successive higher income category was also consistently associated with lower distress, and the unemployed reported higher levels of distress (b = 0.22, p < .001).

Table 2.

Coefficients from OLS Regression Models Predicting Psychological Distress by Spiritual Struggles and Religious Discussion, CHAPS (N = 1,711)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious/Spiritual Struggles (index) |

0.45*** (0.02) |

0.45*** (0.03) |

0.29*** (0.05) |

| Religious Discussion | |||

| Less than once a montha |

-0.05 (0.06) |

-0.45** (0.14) |

|

| Once a week or lessa |

-0.05 (0.06) |

-0.55*** (0.15) |

|

|

Several times a week or morea |

-0.17* (0.07) |

-0.35* (0.17) |

|

| Religious/Spiritual Struggles*Religious Discussion | |||

|

Struggles * Less than once a montha |

0.21** (0.07) |

||

|

Struggles * Once a week or lessa |

0.26*** (0.07) |

||

|

Struggles * Several times a week or morea |

0.09 (0.09) |

||

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | |||

| 30–44 yearsb |

-0.03 (0.07) |

-0.04 (0.07) |

-0.03 (0.07) |

| 45–59 yearsb |

-0.18* (0.08) |

-0.18* (0.08) |

-0.17* (0.08) |

| 60 years or olderb |

-0.38*** (0.08) |

-0.39*** (0.08) |

-0.38*** (0.08) |

| Race | |||

| Black, non-Hispanicc |

0.23** (0.07) |

0.22** (0.07) |

0.21** (0.07) |

| Hispanicc |

-0.07 (0.06) |

-0.07 (0.06) |

-0.05 (0.06) |

| Other Racec |

-0.08 (0.09) |

-0.08 (0.09) |

-0.07 (0.09) |

| Gender | |||

| Femaled |

0.22*** (0.04) |

0.23*** (0.04) |

0.23*** (0.04) |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| HS graduate or equivalente |

-0.03 (0.12) |

-0.02 (0.12) |

-0.01 (0.12) |

|

Vocational/tech school/some college/Associates degreee |

-0.01 (0.11) |

0.01 (0.11) |

0.01 (0.11) |

| Bachelor’s degreee |

0.03 (0.12) |

0.03 (0.12) |

0.04 (0.12) |

|

Post grad study/professional degreee |

-0.11 (0.12) |

-0.11 (0.12) |

-0.09 (0.12) |

| Income | |||

| $30,000 -$60,000f |

-0.15** (0.06) |

-0.15** (0.06) |

-0.15* (0.06) |

| $60,000 to under $100,000f |

-0.23*** (0.06) |

-0.23*** (0.06) |

-0.22*** (0.06) |

| $100,000 or moref |

-0.22** (0.07) |

-0.22** (0.07) |

-0.21** (0.07) |

| Unemployed due to COVID-19 |

0.22*** (0.05) |

0.22*** (0.05) |

0.23*** (0.05) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Widowedg |

0.06 (0.10) |

0.05 (0.10) |

0.06 (0.10) |

| Divorcedg |

0.17** (0.06) |

0.17* (0.07) |

0.16* (0.07) |

| Separatedg |

-0.05 (0.10) |

-0.06 (0.10) |

-0.06 (0.10) |

| Never marriedg |

0.12* (0.06) |

0.10 (0.06) |

0.11 (0.06) |

| Living with partnerg |

0.10 (0.09) |

0.08 (0.09) |

0.08 (0.09) |

| Region of United States | |||

| Midwesth |

-0.03 (0.06) |

-0.04 (0.06) |

-0.04 (0.06) |

| Southh |

-0.06 (0.06) |

-0.06 (0.06) |

-0.05 (0.06) |

| Westh |

-0.05 (0.07) |

-0.05 (0.07) |

-0.06 (0.07) |

| Religious Controls | |||

| Religious Attendance during pandemic | |||

|

Attended about the same as before the pandemici |

-0.29 (0.16) |

-0.31* (0.15) |

-0.28 (0.16) |

| Attended less ofteni |

-0.28 (0.16) |

-0.29 (0.17) |

-0.26 (0.15) |

| Religious Importance | |||

|

About the same as before the pandemicj |

-0.14* (0.06) |

-0.17** (0.06) |

-0.17** (0.06) |

|

Religion has become less importantj |

0.01 (0.09) |

-0.04 (0.10) |

-0.04 (0.10) |

| Religious Affiliation | |||

| Mainline Protestantk |

-0.01 (0.07) |

-0.05 (0.07) |

-0.04 (0.07) |

| Catholick |

-0.04 (0.06) |

-0.08 (0.07) |

-0.09 (0.07) |

| Other Christiank |

0.07 (0.07) |

0.04 (0.07) |

0.03 (0.07) |

| Other Religionk |

0.11 (0.10) |

0.07 (0.10) |

0.05 (0.10) |

| No religionk |

0.25*** (0.06) |

0.20** (0.07) |

0.19** (0.07) |

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

Notes. Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05

a. compared to Never discusses religion

b. compared to 18–29 years

c. compared to White, non-Hispanic

d. compared to Male

e. compared to Less than high school

f. compared to $30,000 or less

g. compared to Married

h. compared to Northeast region

i. compared to Attended more often

j. compared to Religion became more important

k. compared to Conservative Protestant

Model 2 of Table 2 introduces religious discussion to the fold. As in Model 1, greater spiritual struggles were still associated with greater psychological distress (b = 0.45, p < .001). As for the frequency of discussing religious/spiritual matters, relative to those who never discussed religious/spiritual matters with friends/close family members, those who did so several times a week or more reported lower psychological distress (b = -0.17, p < .05). This suggests that as a main effect, greater religious/spiritual discussion was associated with lower psychological distress. We also observe that stable religious attendance before and during the pandemic was associated with lower psychological distress (b = -0.28, p < .05), a finding that also approached significance at the p < .05 alpha level in Model 1. Net of religious/spiritual struggles and religious discussion, it appeared that maintaining the same level of involvement in a religious community as prior to the pandemic was associated with better mental well-being.

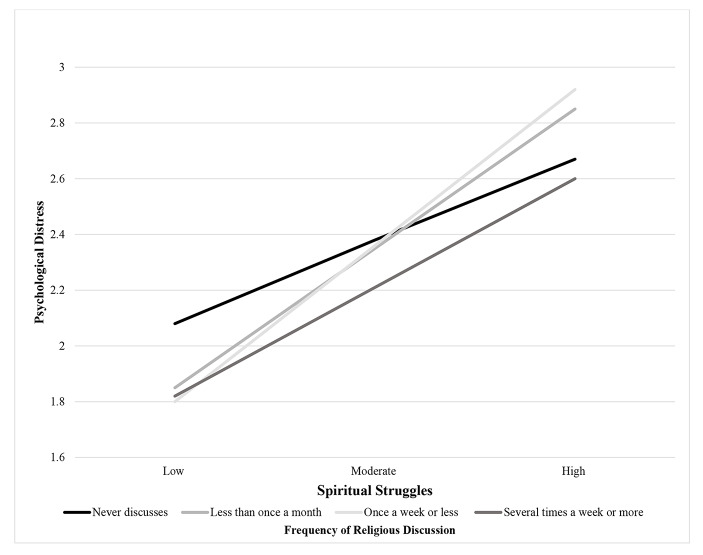

Model 3 analyzed a statistical interaction term between R/S struggles and religious discussion, serving as a test of Hypotheses 2 and 3, which proposed buffering or exacerbating effects of religious discussion for those facing R/S struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results in Model 3 show a significant interaction term between R/S struggles and religious discussion less than once a month (b = 0.21, p < .01) and several times a week or more (b = 0.26, p < .001). Since categorical*continuous interaction terms are notoriously difficult to interpret, Fig. 2 shows predicted psychological distress scores at low (one standard deviation below the mean), moderate (at the mean) and high (one standard deviation above the mean) levels on the spiritual struggles index.

Fig. 2.

Spiritual Struggles and Psychological Distress across Frequency of Religious Discussion. Note. Estimates are derived from Model 3 of Table 2. All other covariates are held at their respective means

We would draw attention to the dark black and dark grey lines of Fig. 1, which represent the relationship between spiritual struggles and psychological distress for those that never discuss religious/spiritual matters, and those that discuss them several times a week or more. At high levels of R/S struggles, psychological distress is minimized by never talking about R/S matters or talking about them frequently. Those who discuss religious matters frequently have average psychological distress scores of 2.60, and those who never discuss religion have average distress scores of 2.67. However, psychological distress appears to be highest in the context of high R/S struggles for those who discuss R/S maters less than once a month, or once a week or less, as these individuals have, on average, psychological distress scores of 2.85 and 2.92. On the whole, the pattern of results depicted in Fig. 1 shows support for Hypotheses 2 and 3: in the context of high amounts of R/S struggles, frequent discussion about religion can act as a buffer, so long as it occurs at least several times a week. However, if it occurs at any lower frequency, religious discussion appears to exacerbate the effects of R/S struggles on psychological distress.

Self-Rated Health

Moving now to the results for physical health (Table 3), Model 1 shows that greater religious/spiritual struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with lower self-rated health (OR = 0.65, p < .001), supporting Hypothesis 1. This relationship between greater R/S struggles and worse self-rated health persists in Model 2 (OR = 0.66, p < .001). Model 2 also considers the main effects of religious discussion on self-rated health. Here, we observed that discussion of religious/spiritual matters once a week or less (OR = 1.35, p < .05) or several times a week or more (OR = 1.65, p < .01) were both associated with better self-rated health relative to those who never discussed religious/spiritual matters. As with psychological distress, religious/spiritual discussion on its own appears to be associated with better self-rated health. A few sociodemographic patterns are also noteworthy in Model 1. For instance, a higher age, 44–59 years, (OR = 0.56, p < .01) and 60 years and older (OR = 0.62, p < .01) was associated with worse self-rated health relative to respondents were 18–29 years old. Education was also associated with better self-rated health during the pandemic (OR = 1.74 for those with a bachelor’s degree, p < .05, OR = 2.08 for those with a graduate degree, p < .05). Falling in a higher income category was also associated with better self-rated health.

Table 3.

Coefficients from Ordinal Logistic Regression Models Predicting Self-Rated Health by Spiritual Struggles and Religious Discussion, CHAPS (N = 1,711, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals shown)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious/Spiritual Struggles (index) |

0.65*** (0.57–0.74) |

0.66*** (0.58–0.75) |

0.67*** (0.52–0.86) |

| Religious Discussion | |||

| Less than once a montha |

0.86 (0.66–1.12) |

0.96 (0.49–1.87) |

|

| Once a week or lessa |

1.35* (1.01–1.80) |

1.29 (0.63–2.64) |

|

|

Several times a week or morea |

1.65** (1.19–2.27) |

1.85 (0.83–4.13) |

|

| Religious/Spiritual Struggles*Religious Discussion | |||

|

Struggles * Less than once a montha |

0.94 (0.68–1.31) |

||

|

Struggles * Once a week or lessa |

1.01 (0.72–1.43) |

||

|

Struggles * Several times a week or morea |

0.80* (0.61–0.97) |

||

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | |||

| 30–44 yearsb |

0.83 (0.60–1.14) |

0.84 (0.61–1.17) |

0.85 (0.61–1.16) |

| 45–59 yearsb |

0.56** (0.39–0.80) |

0.56** (0.39–1.27) |

0.56** (0.39–0.80) |

| 60 years or olderb |

0.62** (0.44–0.88) |

0.63* (0.44–0.90) |

0.64* (0.45–0.91) |

| Race | |||

| Black, non-Hispanicc |

0.88 (0.65–1.22) |

0.85 (0.61–1.17) |

0.85 (0.61–1.16) |

| Hispanicc |

0.99 (0.76–1.29) |

0.97 (0.74–1.27) |

0.96 (0.74–1.26) |

| Other Racec |

0.90 (0.60–1.37) |

0.91 (0.60–1.37) |

0.90 (0.60–1.36) |

| Gender | |||

| Femaled |

0.99 (0.82–1.18) |

0.98 (0.81–1.17) |

0.97 (0.81–1.16) |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| HS graduate or equivalente |

1.25 (0.71–2.18) |

1.23 (0.71–2.14) |

1.24 (0.71–2.16) |

|

Vocational/tech school/some college/Associates degreee |

1.20 (0.71–2.05) |

1.19 (0.70–2.01) |

1.19 (0.70–2.02) |

| Bachelor’s degreee |

1.74* (1.01–3.03) |

1.74* (1.01–3.01) |

1.74* (1.01–3.03) |

|

Post grad study/professional degreee |

2.08* (1.16–3.71) |

2.03* (1.14–3.62) |

2.07* (1.16–3.69) |

| Income | |||

| $30,000 -$60,000f |

1.53** (1.18–1.99) |

1.56*** (1.20–2.03) |

1.56** (1.20–2.04) |

| $60,000 to under $100,000f |

1.77*** (1.34–2.35) |

1.82 (1.37–2.40) |

1.83*** (1.38–2.42) |

| $100,000 or moref |

2.26*** (1.66–3.08) |

2.30*** (1.69–3.13) |

2.31*** (1.70–3.14) |

| Unemployed due to COVID-19 |

0.77* (0.61–0.97) |

0.77* (0.60–0.97) |

0.76* (0.61–0.97) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Widowedg |

1.11 (0.71–1.75) |

1.13 (0.72–1.79) |

1.13 (0.72–1.79) |

| Divorcedg |

0.96 (0.70–1.32) |

1.00 (0.73–1.37) |

0.99 (0.73–1.36) |

| Separatedg |

0.95 (0.59–1.54) |

0.97 (0.60–1.57) |

0.97 (0.60–1.56) |

| Never marriedg |

0.79 (0.60–1.03) |

0.81 (0.61–1.07) |

0.81 (0.61–1.07) |

| Living with partnerg |

0.65* (0.43–0.99) |

0.70 (0.46–1.06) |

0.70 (0.46–1.06) |

| Region of United States | |||

| Midwesth |

0.93 (0.69–1.24) |

0.91 (0.68–1.22) |

0.91 (0.68–1.22) |

| Southh |

1.19 (0.90–1.59) |

1.15 (0.86–1.53) |

1.14 (0.86–1.52) |

| Westh |

0.99 (0.73–1.34) |

0.97 (0.72–1.32) |

0.97 (0.72–1.32) |

| Religious Controls | |||

| Religious Attendance during pandemic | |||

|

Attended about the same as before the pandemici |

0.54 (0.26–1.10) |

0.64 (0.32–1.31) |

0.66 (0.33–1.33) |

| Attended less ofteni |

0.52 (0.26–1.04) |

0.57 (0.28–1.15) |

0.58 (0.29–1.16) |

| Religious Importance | |||

|

About the same as before the pandemicj |

0.95 (0.74–1.23) |

1.06 (0.82–1.37) |

1.07 (0.85–1.40) |

|

Religion has become less Importantj |

0.86 (0.55–1.35) |

1.00 (0.64–1.58) |

1.02 (0.68–1.59) |

| Religious Affiliation | |||

| Mainline Protestantk |

0.96 (0.71–1.30) |

1.10 (0.80–1.50) |

1.10 (0.81–1.50) |

| Catholick |

1.20 (0.91–1.61) |

1.41* (1.04–1.90) |

1.42* (1.05–1.91) |

| Other Christiank |

1.16 (0.85–1.58) |

1.36 (0.99–1.86) |

1.36 (0.99–1.86) |

| Other Religionk |

1.33 (0.82–2.14) |

1.61 (0.99–2.62) |

1.62 (0.99–2.63) |

| No religionk |

0.71* (0.53–0.96) |

0.87 (0.64–1.58) |

0.87 (0.64–1.18) |

| McFadden Pseudo R2 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Notes. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05

a. compared to Never discusses religion

b. compared to 18–29 years

c. compared to White, non-Hispanic

d. compared to Male

e. compared to Less than high school

f. compared to $30,000 or less

g. compared to Married

h. compared to Northeast region

i. compared to Attended more often

j. compared to Religion became more important

k. compared to Conservative Protestant

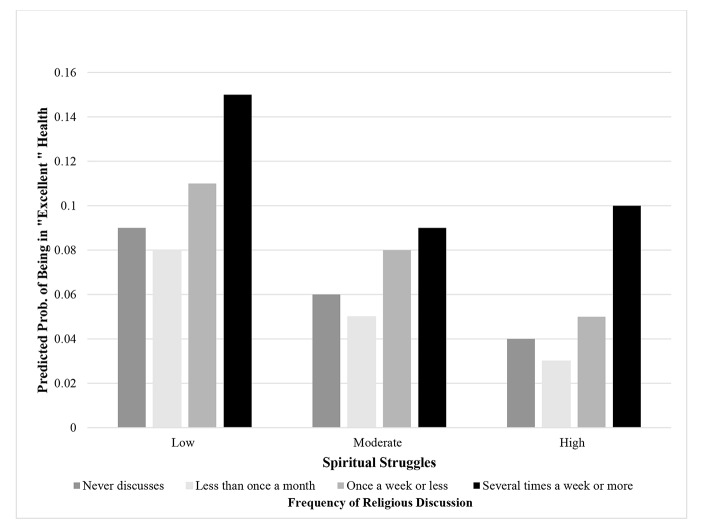

Model 3 of Table 3 shows results from an interaction term between religious discussion and spiritual struggles. As before, we observed a significant interaction term between these two variables for self-rated health, but this time only between R/S struggles and religious discussion several times a week or more (OR = 0.80, p < .05). This interaction term is better described visually, so Fig. 3 plots the predicted probability of being in “excellent” self-rated health across low, moderate, and high spiritual struggles and religious/spiritual discussion.

Fig. 3.

Spiritual Struggles and Self-Rated Health across Frequency of Religious Discussion. Note. Estimates are derived from Model 3 of Table 3. All other covariates are held at their respective means

We focus our attention to Fig. 3 on the last set of bars, which show the likelihood of being in “excellent” physical health for those experiencing high amounts of R/S struggles. Relative to those who never discuss religious/spiritual matters, who only have a 4% likelihood of being in excellent health, those discussing R/S matters several times a week or more have a 10% chance of falling into this top category of self-rated health. In other words, the relationship between R/S struggles and self-rated health is weaker (i.e., attenuated) among those who discuss matters of faith on a bi-weekly basis relative to those who never discuss religious matters. The results for physical health are thus consistent with Hypothesis 2. Unlike for psychological distress, however, we found no evidence that discussion of religious matters in the face of greater R/S struggles exacerbated their ill effect on health. We return in the discussion section to offer an interpretation of this divergent pattern of results across our two indicators of well-being.

Supplemental Analyses

In our main analyses, R/S struggles were assessed as a unidimensional construct and averaged to form an index. Since each type of R/S struggle (interpersonal, intrapersonal, and divine) may have independent effects on health and may combine differently with the discussion of religious/spiritual matters, ancillary analyses examined each type of R/S struggle separately. Results suggest that the main pattern of findings held. Each type of religious struggle was associated with higher psychological distress and worse self-rated health. The main pattern of interaction effects documented in the main analysis also held for each form of R/S struggle, with the exception that the interaction between divine struggles and religious discussion was only marginally significant at a bi-weekly or more discussion frequency. Since prior research (e.g., Exline et al. 2014; Hill et al. 2021) recommends combining these indicators of R/S struggles into an index, we elected to follow suit in our main analyses.

Supplemental analyses also considered whether our main pattern of results differed across religious denomination. Previous research, for instance, has found that Conservative Protestants discuss religious/spiritual matters more with their close confidants (Schafer 2018) and may experience greater negative health consequences of R/S struggles (Mannheimer and Hill 2015). We therefore tested an interaction term between Conservative Protestant, R/S struggles, and religious discussion, which failed to achieve statistical significance. Separate three-way interaction terms between all other religious denominations, R/S struggles, and religious discussion also failed to reach statistical significance. On the basis of these analyses, therefore, we do not have reason to believe that the findings of the main study are being driven by religious denominational differences across our focal variables.

Discussion

Research to date has suggested that religion might be a source of comfort and strength in times of crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic (Dein et al. 2020; Pirutinsky 2020; Schnabel and Schieman 2021). The religious/spiritual dimension of life represents an important source of human strength, coping, and meaning for many people (Exline et al. 2014; Hill and Pargament 2003), contributing to comfort and security in turbulent times (Wilt et al. 2016) and facilitating better well-being (Page et al. 2020). However, the religious life is not always “smooth and easy.” At various points in the life course, individuals are prone experience religious/spiritual struggles, manifested as negative thoughts, beliefs, emotions, or behaviors toward God and other religious people or institutions (Exline et al. 2014). Stressful life events may be an antecedent to R/S struggles, as they have a high potential to shake and shatter the individual’s spiritual orientation and values. The COVID-19 pandemic and the drastic changes to social life that followed were a breeding ground for R/S struggles: lives were lost, many became unemployed, and work, school, and social routines were significantly disrupted. Surely the COVID-19 pandemic challenged individuals’ religious/spiritual belief systems and views of the world. Using data collected roughly one year after the pandemic’s onset, this study had two objectives: first, it sought to assess the prevalence of R/S struggles in a nationally representative sample of Americans, and how these associated with perceptions of psychological distress and self-rated health. Second, recognizing the need to examine aspects of religious life that could alter the negative consequences of R/S struggles for well-being, we proposed that discussing matters of faith and spirituality could help one experience growth through processes of social support (and thus be health beneficial) or it could initiate a process by which one sinks deeper into spiritual despair or loses their faith further (and thus be health detracting).

We discuss three key findings observed in the current study. First, we found that religious/spiritual struggles were somewhat common during COVID-19 across all domains—interpersonal, intrapersonal, and divine. Over a quarter of respondents felt judged by religious people, and over one-third of respondents felt doubt about their religious/spiritual beliefs. Just under 20% of respondents felt abandoned or punished by God. Taken together, this pattern of findings resonates with previous research which has shown robust associations between stressful life events and a fairly high prevalence of R/S struggles (Wortmann, Park, and Edmondson 2011; Haugen 2011; Stauner et al. 2019). In contrast to these prior studies, however, the era of COVID-19 is not an isolated stressful life event, but one that has consequences that reverberates across domains of social life. Therefore, it could be argued that all respondents in our sample, to a greater or lesser extent, were simultaneously experiencing many stressful life events, such as financial hardship (Bierman, Upenieks, Glavin, and Schieman 2021), role blurring from the excessive combination of work and family role (Schieman and Badawy 2021), or fear of a loved one contracting the virus.

A second finding of our study was that R/S struggles were associated with greater psychological distress and worse self-rated health during the pandemic, an association which persisted with controls for changes in other forms of religiosity (e.g., increases/decreases in religious attendance and religious importance) and demographic covariates. This finding is not entirely surprising, since past research has linked greater R/S struggles to higher depression (Ellison and Lee 2010), lower physical health (Mannheimer and Hill 2015; Upenieks 2021) and earlier mortality (Pargament and Exline 2021). To our knowledge, however, this is the first study that has documented a link between R/S struggles and discussions about religious/spiritual matters and their effect on well-being and we do so by using nationally representative data. Our findings add to this growing body of research on the “dark side” of religion by showing that these very same patterns remain true in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, we observe an effect size for psychological distress, where each one-unit increase in R/S struggles is associated with a corresponding 0.5 standard deviation increase in psychological distress, an effect size which supersedes those documented for R/S struggles and distress in more usual times (Ellison and Lee 2010; Hill et al. 2021; Upenieks 2021).

Our third and final key set of findings refer to how the frequency of discussing religious and spiritual matters with close friends and family members may modify the relationship between R/S struggles and psychological distress. Drawing from work on social penetration theory and work within the sociology of religion on negative interaction with co-religionists, we posited that more frequent religious discussion could be a form of positive or negative religious coping which could attenuate or exacerbate the deleterious health consequences of R/S struggles. We observed a different pattern of findings for psychological distress and self-rated health. Beginning with the former, we found that in the context of high R/S struggles, psychological distress was minimized when religious and spiritual matters were never discussed, or were discussed very frequently, several times a week or more. This non-linear “all or nothing” modifying role of religious discussion invites further reflection on the social processes involved in discussing R/S matters.

The insights of social penetration theory proposed that people may talk about sensitive matters with a social tie only when they feel sufficient rapport and trust have been developed, and only when they anticipate that greater “penetration” will be a rewarding experience. This helps understand why, in the context of high R/S struggles, religious discussion several times a week or more would be helpful in mitigating some of the strain that might precipitate psychological distress. Indeed, it is unlikely that someone would discuss religious matters on a bi-weekly or more basis with someone whom they were not comfortable expressing vulnerability about uncertainties in faith with. Spurred by such frequent and intimate discussion about matters of faith, these discussants could be helpful sources of social support for the individuals undergoing R/S struggles. Feeling emotionally supported by those who have engaged in open and honest conversations about faith is beneficial for mental health (Berkman and Glass 2000) and may result in the faster resolution of any R/S struggles, limiting their ability to exact a toll on future mental well-being.

Compared to bi-weekly or more religious discussion, avoiding discussing religious or spiritual matters in its entirety also appeared to be associated with lower psychological distress among those experiencing higher R/S struggles. What may explain this pattern? Though speculative, given that nearly a quarter of the sample was non-religious, the non-religious may not discuss religious matters with their close ties. For these people, not discussing religion when they are experiencing religious/spiritual struggles might be an effective form of avoidance to minimize any impacts of R/S struggles on well-being. For those respondents who are religious, however, it is possible that the harmful association with psychological distress via discussing religious/spiritual matters on a regular (at least monthly) or semi-regular (a few times a year) basis might be accompanied by more negative conversations about religious and spiritual matters. Discussing religious/spiritual matters fairly infrequently, compared to more regular discussion, might signal that the discussant may not be perceived as emotionally close to the respondent. If these relationships lack the greater intimacy that would characterize more frequent religious discussion, it is possible that these relationships are accompanied by more negative social interactions. For instance, still discussing matters of faith, but less frequently, could be an indication that a person perceives being ostracized, shamed, or stigmatized for having uncertainties in faith (Ellison and Lee 2010) and failing to meet the standards of the religious community (Hill and Cobb 2011; Mannheimer and Hill 2015). Choosing to infrequently discuss matters of faith appears to exacerbate the negative mental health consequences precipitated by R/S struggles. Discussions of religious/spiritual matters should therefore be approached with caution for those experiencing struggles given the findings of the current study.

This non-linear pattern of frequency of religious discussion in the context of high R/S struggles was not entirely replicated for self-rated physical health, however. For this outcome, we observed that bi-weekly or more religious discussion mitigated the harmful association between R/S struggles and physical health, yet we did not find that those who never discussed religious matters were not better off compared to those who discussed religious matters but did so infrequently. We offer a speculative interpretation for this divergent finding. It should be noted that there has been less work in the religion and health field on how R/S struggles affect perceptions of psychological distress and self-rated health so theoretical mechanisms are not firmly established.

As one possible interpretation, self-rated health captures indices of physical stress responses such as inflammation as well as allostatic load (Leshem-Rubinow et al. 2015; Vie et al. 2014). Compared to psychological distress, which may be respond more rapidly to life stressors (including those caused by the pandemic), self-rated physical health, at least physiologically, may not have the same immediate response. More frequent religious discussion may protect against physical health decline for people faced with R/S struggles, but conversations of matters of faith that are more negative in tone (e.g., as possibly indicated by less frequent discussion) may not exert a physiological health toll until months or even years later. More research is certainly needed on the longitudinal consequences of R/S struggles and physical health, and the inclusion of objective physiological indicators (e.g., biomarkers) could also allow for a more thorough test as well. Taken together, however, that we found consistent buffering patterns across perceptions of psychological distress and self-rated health for bi-weekly or more religious discussion in the context of R/S struggles provides greater confidence in this result. These results suggest that once a deeper level of comfort and trust have been established with another individual, discussing religious/spiritual matters may be a helpful strategy for dealing with R/S struggles, having a confidant alongside to help one work through their uncertainties in faith and perhaps achieve spiritual growth.

Limitations and Future Directions

Though this was the first study to consider how R/S struggles are associated with well-being in nationally representative sample of Americans and how religious discussion may factor into the overall association of R/S struggles with perceptions of psychological distress and self-rated health, the analysis does not come without limitations. First, an important limitation of this study was the reliance on cross-sectional data, rendering all causal and temporal inferences tentative. For instance, it was proposed that R/S struggles impact well-being. However, one could also argue that people with initially low levels of mental and physical well-being could experience more struggles with their faith. It is clear that this issue must be explored more rigorously with longitudinal data. What is more, panel data that measures religious behavior before and during the pandemic would have allowed us to document within-person changes in R/S struggles and religious doubt both in more normal and chaotic times.

Second, more research is needed to advance the themes presented in this study. On our key moderator, religious discussion, much is left unknown with only a one-item measure. For instance, what do people actually talk about when they discuss religious or spiritual matters? Do the topics of discussion closely relate to the three domains of R/S struggles? In an increasingly polarized political climate in the United States, it would be helpful, at a minimum, to distinguish conversations of personal religious beliefs and spirituality from conversations about the intersection of religion and public/political life. Moreover, what is the relationship of the respondent to each of the social ties they report discussing religion with, and what is the discussant’s religious background? Prior research has found that people are more likely to discuss religious matters with those who share their religious background (Schafer 2018). Since these questions cannot be answered within the current data, the precise theoretical mechanisms linking R/S struggles, religious discussion, and well-being cannot be inferred.

Finally, further chronicling the religious disclosure process would be another fruitful direction for future research. In particular, it would be helpful to know how the non-religious (who also experience R/S struggles) decide to initiate conversations about religious and spiritual matters. As a distrusted and stigmatized group in the United States (Edgell et al. 2016), the non-religious may be more guarded in their discussion of religious/spiritual matters and may have to perceive an even higher likelihood of benefits flowing from such intimate disclosure to open up about matters of faith.

Conclusions and implications

We see several implications of the findings of our study for clinical practitioners and religious counselors. Encouraged by discussions of faith with close network confidants, people experiencing R/S struggles might seek help in the form of counseling in both secular and/or religious settings. Therapies focusing on R/S struggles might be effective for treating mental and physical health problems. The mixed findings of our study showing that never discussing religion with close ties or discussing religion several times a week or more producing the most favorable psychological distress scores should sensitize counselors to the benefits and harm that could be associated with opening up discussions on matter of faith. If therapists sense, for instance, that a client wants to rely on God to help them cope with life stressors but is feeling abandoned or punished by God, a gentle prompt to help them explore the reasons for why this is. Free of judgment for experiencing R/S struggles, which may unfortunately be commonplace in religious communities on the part of the therapist could help promote spiritual growth and help a person re-establish their reliance on God. It is also likely that by expressing an interest in the R/S struggles of their clients, clinicians might open the door to a conversation about deeper sources of distress and suffering, especially in light of the hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers, clinicians, and religious clergy should all have a vested interest in the relationship between R/S struggles and well-being. Post-pandemic economic recovery is almost surely going to be connected to population physical and mental health. Exploring potential resilience factors, such as religious discussion, may help inform broader or more local strategies aimed at economic recovery. However, the results of the current study suggest that religious coping methods such as religious discussion had both positive and negative implications for well-being. Our results therefore invite future investigation into the role of religious coping in mitigating the effects of pandemic hardship.

Altogether, the findings of the current study highlight the role of spiritual struggles in undermining health and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers and clinical practitioners alike should devote more attention to R/S struggles and how they continue to ebb and flow as society makes its return to a state of normalcy, seeking to assess in the coming months and years what is likely to be persistent negative impacts on physical and mental health.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Altman Irwin, Taylor Dalmas A. Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, Jeanet. S. 2020. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Working paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo John T, Hawkley Louise C. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3):S39–S52. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley Charles Horton. Human nature and the social order. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publisher; 1902. [Google Scholar]