Abstract

Background

While hate crimes rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, few studies examined whether this pandemic-time racial discrimination has led to negative health consequences at the population level.

Objective

We examined whether experienced and perceived racial discrimination were associated with mental or behavioral health outcomes during the pandemic.

Design

In October 2020, we conducted a national survey with minorities oversampled that covered respondents’ sociodemographic background and health-related information.

Participants

A total of 2709 participants responded to the survey (response rate: 4.2%).

Main Measures

The exposure variables included (1) experienced and encountered racial discrimination, (2) experienced racial and ethnic cyberbullying, and (3) perceived racial bias. Mental health outcomes were measured by psychological distress and self-rated happiness. Measures for behavioral health included sleep quality, change in cigarette smoking, and change in alcohol consumption. Weighted logistic regressions were performed to estimate the associations between the exposure variables and the outcomes, controlling for age, gender, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, eligibility to vote, political party, COVID-19 infection, and geographic region. Separate regressions were performed in the six racial and ethnic subgroups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, East Asian, South Asian, and Southeast Asian respondents.

Key Results

Experienced racial discrimination was associated with higher likelihood of psychological distress (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.18, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.34–3.55). Experienced racial discrimination (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.34–3.99) and perceived racial bias (AOR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.00–1.09) were both associated with increased cigarette smoking. The associations between racial discrimination and mental distress and substance use were most salient among Black, East Asian, South Asian, and Hispanic respondents.

Conclusions

Racial discrimination may be associated with higher likelihood of distress, and cigarette smoking among racial and ethnic minorities. Addressing racial discrimination is important for mitigating negative mental and behavioral health ramifications of the pandemic.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07540-2.

KEY WORDS: racial bias, racial discrimination, mental health, cyberbully, substance use, COVID-19, pandemic

INTRODUCTION

Disease outbreaks often result in rising mental health challenges,1 and the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception.2 Racial stereotyping of the pandemic (e.g., labeling COVID-19 as “kung flu”)3, 4 could elevate psychological challenges for underserved groups.5 While personally mediated racism, defined as discrimination toward others according to their race, is known to have adverse health effects, evidence is scarce regarding the impact of interpersonal racism during the pandemic, such as hate crimes against Asian Americans and police brutality experienced by Black individuals, on victims’ mental health,6 and possible subsequent behaviors such as substance misuse. With these factors stacked on top of disparities that minorities have been facing in exposure, susceptibility, and treatment prior to the pandemic,7 empirical research is needed to study the possible role of racial discrimination in mental and behavioral health during the pandemic.

Given the potential ramifications after the pandemic-time rise of hate crimes, our study aims to examine whether personal experiences of racial discrimination, racial and ethnic cyberbullying,8 or perceived racial bias are associated with mental and behavioral health during the pandemic in the USA.

METHODS

In October 2020, we worked with the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) to conduct a nationally representative survey of adults (18 and above) in the USA.9 We oversampled Asian, Black, and Hispanic respondents as major racial injustice events occurred to these minority groups in 2020.5 The sample for our study was randomly selected from the AmeriSpeak Panel using sampling strata based on age, gender, race and ethnicity, and educational attainment, following the American Association for Public Opinion Research guidelines.8, 10 AmeriSpeak® is a probability-based panel designed to be representative of the US non-institutionalized population, with most households participating in online surveys and non-Internet households being provided with telephone interviews. Additional Asian respondents were recruited from Dynata panel participants.11 With a response rate of 4.2%, 2709 respondents were surveyed in either English or Spanish. Poststratification survey weights were constructed to reflect the demographic profile of the US population, incorporating the probability of selection and then incorporating the probability of nonresponse and ranking ratio adjustments (to population benchmarks).12 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the NORC.

Survey respondents were asked about whether they personally experienced discrimination or unfair treatment because of their race or ethnicity during the pandemic. Additionally, one’s perceived racial bias was assessed using an eight-item Coronavirus Racial Bias Scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).13 We averaged the Likert-scale responses to the eight questionnaire items (from 1 being “strongly disagree” to 4 being “strongly agree”); thus, a higher score indicates more perceived bias against one’s race or ethnicity. Given the documented link between racialized aggression in social media and the victim’s mental health issues,14 we asked respondents whether they had been cyberbullied because of their race or ethnicity.

The Kessler Distress Scale-6 (K6, Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.89 to 0.92) was used to measure psychological distress.15 The items included feeling “nervous,” “hopeless,” “restless or fidgety,” “depressed,” “everything was an effort,” and “worthless” in the past 30 days, with responses of “none of the time” being zero to “all of the time” being four. The K6 score ranges 0–24, with a score of 13 or higher indicating non-specific serious psychological distress.16, 17 Moreover, the respondents were asked to rate their level of happiness with a single-item overall happiness scale both before and during the pandemic.18 We recoded the change from pre-pandemic happiness to post-pandemic happiness into a dichotomous variable to measure decrease in happiness during the pandemic.19

For behavioral outcomes, the respondents were asked to report the number of cigarettes they smoked per day and the number of alcoholic drinks they consumed per week before and during the pandemic. Dichotomous variables were created to indicate any increase in cigarette consumption and any increase in alcohol consumption during the pandemic. A study from Italy showed that quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with poor sleep quality, which could lead to negative mental health.20 Further, disparities in sleep quality by race and ethnicity and socioeconomic status have been documented.20, 21 Therefore, we included poor sleep quality as an outcome.22 A single-item Sleep Quality Scale (SQS, 0 = terrible and 10 = excellent) was used to measure the respondent’s sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic, with those reporting 3 and lower coded as having poor sleep quality.23

Unadjusted associations between personal experiences of racial discrimination and perceived racial bias and mental and behavioral health by race and ethnicity were examined using chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA test for continuous variables, respectively. Simple weighted logistic regressions and multivariate weighted logistic regressions were used to estimate the associations between the racial discrimination predictors and mental and behavioral outcomes described above.

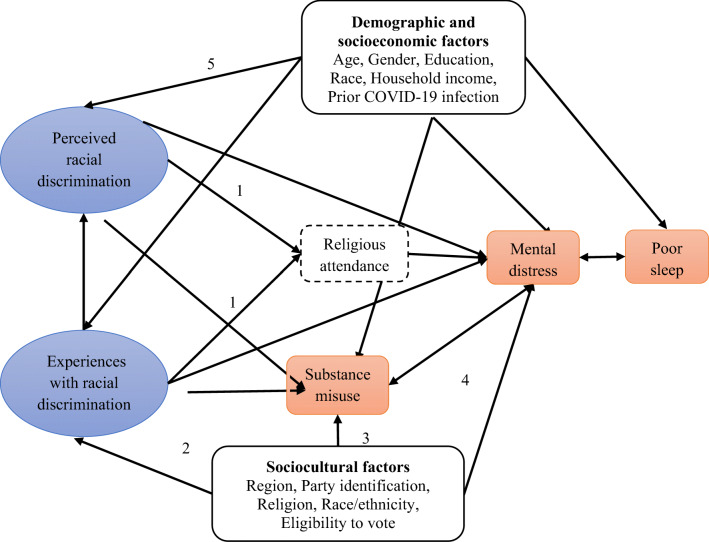

We developed a conceptual framework to guide the covariate selection in the multivariate models (Fig. 1). We controlled for sociodemographic factors that are associated with experienced and perceived racial discrimination: age, gender, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, and household income. We also included the following sociocultural confounders that were associated with experienced and perceived racial discrimination and could influence mental and behavioral outcomes: ineligibility to vote (a proxy for being a noncitizen immigrant or being denied voting rights due to prior conviction, because both disenfranchised groups reported higher likelihood of experiencing racial discrimination and psychological distress),24–27 party identification, and geographic region, as previous research has found that geographic region and political affiliation were associated with racial discrimination experience28 and mental and behavioral health outcomes.29, 30 Additionally, we controlled for whether the respondents reported testing positive for COVID-19, as mental illness was found to be more often among COVID-19 survivors and racist attacks targeting minority groups’ preventive behaviors (e.g., mask wearing) have been documented.31, 32 Race and ethnicity is considered both a demographic factor and a sociocultural factor that is linked with one’s social status, access to resources, social capital, and experiences of racism. Therefore, we included race and ethnicity in the main model to control for race-related residual confounding. Since racial discrimination experience and perception might affect racial or ethnic subgroups differently, we performed these models separately for six racial and ethnic subgroups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, East Asian, South Asian, and Southeast Asian respondents.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the relationship between racial discrimination and mental health. References: 1, Hayward, R. D., & Krause, N. (2015). Religion and strategies for coping with racial discrimination among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(1), 70; 2, Mayrl, D., & Saperstein, A. (2013). When white people report racial discrimination: the role of region, religion, and politics. Social Science Research, 42(3), 742-754; 3, Nesoff, E. D., Marziali, M. E., & Martins, S. S. (2021). The estimated impact of state-level support for expanded delivery of substance use disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addiction; 4, Collins, R. N., Mandel, D. R., & Schywiola, S. S. (2021). Political identity over personal impact: early US reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 555; 5, Goldman, D. S. (2004). The modern-day literacy test: felon disenfranchisement and race discrimination. Stan. L. Rev., 57, 611.

All analyses were weighted to account for the survey design and nonresponse bias using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). For the subgroup analyses, Bonferroni adjustment was applied: dividing the threshold p value of 0.05 by the number of comparisons (n = 6) to get a p value of 0.0083 and 99.17% confidence intervals. As the variables used in our models had few missing values (among 2709 respondents, we had 2699 complete cases for the serious psychological distress, 2629 for the decrease in happiness, 2613 for the increase in smoking, 2621 for the increase in alcohol consumption, and 2584 complete cases for the sleep quality models), we decided not to impute these missing values.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the analytic sample. About 8.81% of the participants had experienced racial discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic by October 2020, with higher percentages seen in racial and ethnic minorities (Table 2). Similarly, minority groups reported a significantly higher level of perceived racial bias than non-Hispanic White respondents. There was a statistically significant association between race or ethnicity and personal encounter with racial and ethnic cyberbullying, with East Asian respondents reporting the highest frequency of encountering racial and ethnic cyberbullying (19.45%) and non-Hispanic White respondents reporting the lowest frequency (6.54%) (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Study Sample

| Proportion * (%) | Count in Sample (n=2709) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean, S.E.), y | 47.49 (0.61) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 48.3 | 1,296 |

| Female | 51.7 | 1,413 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 9.8 | 154 |

| High school graduated | 28.2 | 429 |

| Vocational/some college | 27.7 | 1,073 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 18.7 | 584 |

| Post grad/professional | 15.5 | 469 |

| Ineligible to vote | ||

| Yes | 1.8 | 104 |

| No | 98.8 | 2605 |

| Political Party | ||

| Independent/None | 13.2 | 448 |

| Democrat | 50.9 | 1610 |

| Republican | 35.9 | 651 |

| Household Income | ||

| <$39999 | 33.4 | 967 |

| $40000-$99999 | 42.5 | 1,099 |

| $100000+ | 24.1 | 643 |

| Prior COVID-19 infection | ||

| Yes | 2.5 | 69 |

| No | 97.5 | 2,640 |

| Region | 17.4 | 392 |

| Northeast | 20.7 | 477 |

| Midwest | 38.0 | 906 |

| South | 23.8 | 934 |

| West | 17.4 | 392 |

*Mean and proportions were estimated using sampling weights

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis Between Race/Ethnicity and Experienced/Perceived Racial Discrimination and Mental Health and Substance Use

| Race/ethnicity | Overall | p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | East Asian | South Asian | Southeast Asian | Other | |||

| Encountered discrimination, % (95% CI)* |

2.70 (1.23–4.16) |

19.27 (15.46–23.08) |

15.68 (11.31–20.06) |

22.46 (17.71–27.22) |

10.57 (5.09–16.06) |

16.84 (10.93–22.77) |

28.13 (15.76–40.5) |

8.81 (7.38–10.24) |

< 0.001 |

| Perceived racial bias, mean (95% CI)† |

1.51 (1.45–1.57) |

2.48 (2.41–2.55) |

2.09 (2.01–2.17) |

2.36 (2.29–2.43) |

1.82 (1.69–1.94) |

2.20 (2.08–2.32) |

2.14 (1.95–2.32) |

1.79 (1.74–1.84) |

< 0.001 |

| Encountered racial/ethnic cyberbully, % (95% CI)‡ |

6.54 (3.98–9.10) |

18.32 (14.30–22.32) |

16.98 (12.43–21.52) |

19.45 (15.25–23.67) |

15.11 (8.96–21.26) |

17.03 (11.42–22.64) |

10.42 (2.60–18.24) |

10.54 (8.67–12.40) |

< 0.001 |

| Psychological distress, % (95% CI)§ |

13.96 (10.28–17.64) |

15.93 (12.15–19.72) |

22.62 (17.78–27.46) |

12.02 (8.87–15.17) |

22.61 (15.57–29.66) |

29.68 (21.63–37.72) |

13.82 (3.34–24.29) |

15.90 (13.42–18.39) |

< 0.001 |

| Poor sleep quality, % (95% CI) |

11.88 (8.60–15.17) |

16.49 (12.68–20.29) |

18.31 (13.73–22.89) |

11.44 (7.64–15.23) |

7.16 (3.26–11.06) |

8.15 (4.39–11.90) |

24.53 (11.27–37.79) |

13.84 (11.55–16.11) |

0.009 |

| Decrease in happiness, % (95% CI) ¶ |

57.87 (52.82–62.92) |

54.68 (49.75–59.61) |

56.71 (51.15–62.27) |

61.26 (55.87–66.66) |

55.73 (47.10–64.37) |

54.00 (45.33–62.68) |

64.05 (51.00–77.11) |

57.51 (54.17–60.84) |

0.247 |

| Increase in cigarette smoking, % (95% CI) # |

9.06 (6.13–11.98) |

19.89 (15.78–24.01) |

14.64 (10.47–18.82) |

4.59 (2.69–6.48) |

12.76 (6.55–18.96) |

8.43 (3.52–13.34) |

15.19 (5.07–25.30) |

11.40 (9.36–13.44) |

< 0.001 |

| Increase in alcohol consumption, % (95% CI)** |

21.40 (17.28–25.54) |

32.51 (27.89–37.13) |

34.33 (28.99–39.69) |

16.25 (11.92–20.57) |

23.32 (16.02–30.61) |

14.69 (7.78–21.60) |

40.91 (26.48–55.34) |

25.36 (22.52–28.19) |

< 0.001 |

| Sample size, n | 514 | 590 | 529 | 518 | 187 | 219 | 94 | 2709 | |

All statistics are weighted

*Pearson chi-square test shows a significant association between race/ethnicity and experiencing racial discrimination during the pandemic

†ANOVA test shows that the scale of concern for racism against one’s race/ethnicity differs significantly between different racial/ethnic groups. This scale is constructed by summing up the responses to the following eight questions: a. [I believe the country has become more dangerous for people in my racial/ethnic group because of the coronavirus; b. [People of my race/ethnicity are more likely to lose their job because of the coronavirus]; c. [I worry about people thinking I have the coronavirus simply because of my race/ethnicity]; d. [Most social and mass media reports about the coronavirus create bias against people of my racial/ethnic group]; e. [People of my race/ethnicity are more likely to get the coronavirus]; f. [People of my race/ethnicity will not receive coronavirus healthcare as good as the care received by other groups]; g. [Since the coronavirus I have seen a lot more cyberbullying of people of my race/ethnicity]; h. [Negative social media posts against people of my race/ethnicity have increased because of the coronavirus]

‡Pearson chi-square test shows a significant association between race/ethnicity and experiencing racial/ethnic cyberbullying during the pandemic

§ANOVA test shows that distress differs significantly between different racial/ethnic groups

¶Pearson chi-square test shows an insignificant association between race/ethnicity and decrease in happiness

#Pearson chi-square test shows a significant association between race/ethnicity and increase in cigarette smoking

**Pearson chi-square test shows a significant association between race/ethnicity and increase in alcohol consumption

Around 16% of the respondents reported having serious psychological distress. Hispanic respondents had a significantly higher proportion of serious psychological distress (22.62%) and a higher proportion of increasing alcohol consumption (34.33%) than non-Hispanic White (serious psychological distress: 13.96%; increase in alcohol consumption: 21.40%) and East Asian respondents (serious psychological distress: 12.02%; increase in alcohol consumption: 16.25%), whereas Black respondents had a significantly larger proportion of increasing cigarette smoking (19.89%) than non-Hispanic White (9.06%) and East Asian respondents (4.59%). The prevalence of poor sleep quality was similar between non-Hispanic White (11.88%) and East Asian respondents (11.44%), with higher prevalence among Black (16.49%) and Hispanic respondents (18.31) and lower prevalence among South Asian (7.16%) and Southeast Asian respondents (8.15%).

In the unadjusted models (Table 3), personal encounter with racial discrimination and racial and ethnic cyberbullying were significantly associated with higher risk of serious psychological distress (racial discrimination: odds ratio [OR] = 2.09, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.36–3.22; racial and ethnic cyberbullying: OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.01–2.70), whereas in the adjusted models, only personal racial discrimination encounter was significantly associated with serious psychological distress (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.32–3.56). In the unadjusted models, both perceived and experienced racial discrimination were significant predictors of poor sleep quality (perceived racial discrimination: OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.07; experienced racial discrimination: OR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.25–3.14), while in the adjusted models, no significant association was observed between racial discrimination and poor sleep quality (AOR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.06). None of the three exposure variables were significantly associated with decreases in happiness in either unadjusted or adjusted models. In the unadjusted models, all three exposures were significantly associated with increases in cigarette smoking, and perceived racial bias was also significantly associated with increases in alcohol consumption (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.04), whereas in the adjusted models, perceived racial bias and personal racial discrimination encounter were significantly associated with an increase in cigarette smoking during the pandemic (perceived racial bias: AOR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00–1.09; racial discrimination encounter: AOR = 2.44, 95% CI: 1.42–4.21), and none of the associations were significant for increases in alcohol consumption in the adjusted model (AOR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.96–1.02).

Table 3.

Associations of Perceived Racial Bias and Experiences with Racial Discrimination with Mental Health and Substance Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Psychological distress OR (95% CI) | Decrease in happiness OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |

| Perceived racial bias | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 2.09** (1.36, 3.22) | 2.17** (1.32, 3.56) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.11) | 0.78 (0.52, 1.16) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.65* (1.01, 2.70) | 1.34 (0.76, 2.34) | 0.93 (0.62, 1.39) | 0.98 (0.63, 1.52) |

| Sample size, n | 2699 | 2629 | ||

| Poor sleep quality OR (95% CI) | Increase in cigarette smoking OR (95% CI) | |||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |

| Perceived racial bias | 1.04* (1.01, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.08*** (1.04, 1.11) | 1.04* (1.00, 1.09) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 1.98** (1.25, 3.14) | 1.54 (0.91, 2.63) | 3.52*** (2.24, 5.54) | 2.44** (1.42, 4.21) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.54 (0.94, 2.53) | 1.05 (0.61, 1.80) | 2.68*** (1.67, 4.31) | 1.20 (0.67, 2.16) |

| Sample size, n | 2584 | 2613 | ||

| Increase in alcohol consumption OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.02* (1.00, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | ||

| Racial discrimination encounter | 1.37 (0.95, 1.98) | 1.11 (0.75,1.63) | ||

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.40 (0.94, 2.07) | 1.27 (0.81, 1.99) | ||

| Sample size, n | 2621 | |||

*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001

†The weighted logistic regressions controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, eligibility to vote, party identification, household income, prior COVID-19 infection, and region; odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) are reported

Our subgroup analyses (Table 4) found that perceived racial bias was associated with serious psychological distress among Black (AOR = 1.12, 99% CI: 1.02–1.23) and East Asian respondents (AOR = 1.13, 99% CI: 1.04–1.23), and encounters with racial discrimination was significantly associated with serious psychological distress only among East Asian respondents (AOR = 2.98, 99% CI: 1.09–8.13). Perceived racial bias was significantly associated with a decrease in happiness among Black respondents (AOR = 1.07, 99% CI: 1.01–1.13), as well as having higher odds of poor sleep quality among Black (AOR = 1.08, 95% CI: 0.99–1.17) and East Asian respondents (AOR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.00–1.19). Table 5 shows that experiencing racial discrimination was significantly associated with an increase in cigarette smoking among non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and South Asian respondents, as well as higher odds of increases in alcohol consumption among South Asian respondents. Experiencing racial and ethnic cyberbullying was associated with increases in smoking among Hispanic respondents (AOR = 3.87, 99% CI: 1.31–11.48).

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations Between Perceived Racial Bias and Experiences with Racial Discrimination and Mental Health and Sleep Quality During the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Race/Ethnic Subgroups

| Psychological distress OR (99% CI) |

Decrease in happiness OR (99% CI) |

Poor sleep quality OR (99% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 7.07 (0.96, 52.32) | 0.51 (0.09, 2.80) | 2.64 (0.29, 23.71) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.20 (0.14, 10.18) | 1.94 (0.49, 7.75) | 1.10 (0.22, 5.42) |

| Sample size, n | 511 | 507 | 501 |

| Black respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.12* (1.02, 1.23) | 1.07* (1.01, 1.13) | 1.08* (0.99, 1.17) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 1.72 (0.64, 4.57) | 1.02 (0.49, 2.11) | 2.42 (0.94, 6.25) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 0.82 (0.27, 2.48) | 1.00 (0.45, 2.21) | 0.85 (0.31, 2.36) |

| Sample size, n | 586 | 585 | 580 |

| Hispanic respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 2.08 (0.76, 5.71) | 0.70 (0.26, 1.89) | 0.96 (0.26, 3.47) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.34 (0.42, 4.28) | 0.49 (0.19, 1.31) | 0.88 (0.25, 3.11) |

| Sample size, n | 528 | 527 | 517 |

| East Asian respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.13* (1.04, 1.23) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.10) | 1.09** (1.00, 1.19) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 2.98* (1.09, 8.13) | 1.79 (0.77, 4.16) | 2.89 (0.86, 9.76) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 0.75 (0.26, 2.16) | 0.46 (0.18, 1.19) | 1.27 (0.37, 4.34) |

| Sample size, n | 736 | 736 | 472 |

| South Asian respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.03 (0.90, 1.19) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.31) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 5.71* (1.08, 30.18) | 1.06 (0.19, 5.85) | 4.10 (0.80, 21.15) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.29 (0.21, 7.84) | 0.58 (0.13, 2.61) | 0.80 (0.13, 4.79) |

| Sample size, n | 187 | 181 | 103 |

| Southeast Asian respondents | |||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.04 (0.93, 1.18) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.31) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 2.27 (0.55, 9.33) | 1.02 (0.29, 3.62) | 4.10* (0.80, 21.15) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 2.22 (0.49, 10.04) | 0.50 (0.13, 1.99) | 0.80 (0.13, 4.79) |

| Sample size, n | 219 | 216 | 134 |

The weighted logistic regressions controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, eligibility to vote, party identification, household income, prior COVID-19 infection, and region. Odds ratios (ORs) and 99.17% confidence intervals (99% CIs) are reported

*p is smaller than the Bonferroni-corrected threshold value of 0.0083

Table 5.

Adjusted Associations Between Perceived Racial Bias and Experiences with Racial Discrimination and Substance Use Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Race/Ethnic Subgroups

| Increase in smoking OR (99% CI) |

Increase in alcohol OR (99% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.08 (0.96, 1.23) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 20.24* (1.62, 253.21) | 0.89 (0.10, 7.68) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 0.20 (0.01, 4.03) | 0.85 (0.18, 4.05) |

| Sample size, n | 482 | 504 |

| Black respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.08 (1.00, 1.16) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 1.32 (0.53, 3.32) | 0.93 (0.45, 1.91) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.26 (0.48, 3.33) | 1.65 (0.75, 3.60) |

| Sample size, n | 574 | 585 |

| Hispanic respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 0.99 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 3.87* (1.31, 11.48) | 1.14 (0.44, 2.96) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 4.16* (1.24, 13.99) | 1.21 (0.43, 3.42) |

| Sample size, n | 527 | 527 |

| East Asian respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 0.71 (0.12, 4.14) | 1.29 (0.51, 3.25) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 4.99 (0.89, 28.03) | 1.30 (0.44, 3.79) |

| Sample size, n | 694 | 727 |

| South Asian respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 0.99 (0.89,1.09) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 13.79* (1.36, 139.87) | 10.85† (1.45, 81.47) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 7.94 (0.74, 84.94) | 1.72 (0.34, 8.81) |

| Sample size, n | 162 | 180 |

| Southeast Asian respondents | ||

| Perceived racial bias | 1.01 (0.86, 1.18) | 0.92 (0.88, 1.31) |

| Racial discrimination encounter | 2.28 (0.30, 17.42) | 4.10 (0.80, 21.15) |

| Racial/ethnic cyberbully | 1.19 (0.07, 19.43) | 0.80 (0.13, 4.79) |

| Sample size, n | 159 | 199 |

The weighted logistic regressions controlled for age, gender, educational attainment, eligibility to vote, party identification, household income, prior COVID-19 infection, and region. Odds ratios (ORs) and 99.17% confidence intervals (99% CIs) are reported

*p is smaller than the Bonferroni-corrected threshold value of 0.0083†p = 0.009, slightly larger than our Bonferroni-adjusted p value threshold of p = 0.0083

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that experiences of racial discrimination were associated with elevated risk of serious psychological distress and increased cigarette consumption. Perceived racial bias was significantly associated with increases in smoking during the pandemic. We did not find the link between experienced or perceived racial discrimination and decreases in happiness, poor sleep quality, or increases in alcohol consumption among the full sample. When stratified by race and ethnicity, the associations of racial discrimination with mental or behavioral health were most salient among Black, East Asian, Southeast Asian, and Hispanic respondents. Moreover, we found that 15.90% of the participants in our national sample had serious psychological distress in October 2020, a prevalence estimate similar to the proportion estimated in April 2020 (13.6%) and much higher than the pre-pandemic prevalence in 2018 (3.9%).33 A longitudinal survey of a global convenience sample (in April and September 2020) identified increased alcohol consumption and psychological distress among adults during the pandemic, and these challenges tended to be elevated among minorities. 34 These prevalence estimates showed the magnitude of mental health challenges the pandemic incurred.

Previous studies have documented how interpersonal racism affected the health of the minorities before the pandemic, 35, 36 as well as how elevated racism during the pandemic worsened the mental health status of the population.37 But to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to identify the associations between experienced and perceived racial discrimination and serious psychological distress among the adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, perceived racial bias was significantly associated with serious psychological distress and poor sleep quality among Black and East Asian respondents, and experiences of racial discrimination were associated with serious psychological distress among South Asian respondents. In fact, exposure to racial discrimination may upregulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, increase stress and cardiometabolic disease risk, and cumulatively lead to chronic conditions.38 In this study, we also studied substance use behaviors. The link between one’s experience with racial discrimination and substance use has been documented in previous studies,39 and it has been proposed that racial discrimination victims may use smoking as a coping strategy with their stress from experiencing racial discrimination.39 While previous studies about racial discrimination and substance misuse tended to focus on Black individuals, our study reveals that such a link is significant across different racial/ethnic subgroups, including Hispanic and Asian adults, demonstrating the far-reaching harm of racial discrimination on population health. However, we noticed that some of the findings on smoking behavior had extremely large confidence intervals, and this was due to our Bonferroni adjustment that generated less precise estimates and also due to the small cell sizes in certain variables (e.g., racial discrimination encounter among non-Hispanic white respondents).40 Nevertheless, the estimates were conservative, and the presence of a significant finding underscores the likely strength of the association.

Our study shows that one’s encounter with racial discrimination during the pandemic was more prevalent among all minority groups than the non-Hispanic White population. This includes East Asian and South Asians, who have a higher average household income than the non-Hispanic White population.41 On the other hand, considering that 60% of the US population are non-Hispanic White, the 2.70% of them who had experienced racial discrimination during the pandemic were not trivial. In our subgroup analysis, their experience with racial discrimination was also linked with increased cigarette smoking and elevated level of distress. A study of low-income, urban White people found that 39% of them perceived racial discrimination, associated with a higher rate of anxiety and depression,42 while the low-income White population was understudied in health literature.42 Therefore, while the minority groups bear a disproportional burden of the negative health consequences of racial discrimination, it is important to note that racial discrimination poses a threat to mental and behavioral health to all racial and ethnic groups despite major structural protections and privileges for the non-Hispanic White population.

It is concerning that Hispanic respondents have higher risks of increasing cigarette smoking during the pandemic than the non-Hispanic White population, a pattern consistent with an April–May 2020 nationwide survey showing that increased or newly initiated substance use was reported among 36.9% of Hispanic respondents, compared with 14.3–15.6% among non-Hispanic White people.43 Acculturation and acculturative stress among Hispanic adults could influence substance use through the deterioration of their cultural-specific family values, attitudes, and familistic behaviors.44 The anti-immigrant political environment and policies during and before 2020 could have added to the stress from racial stigma and fear of deportation,45 which could help explain the increased cigarette smoking among the Hispanic population during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the Hispanic population’s higher risk of losing jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic could have contributed to increased cigarette smoking, given the documented evidence that unemployment could lead to more substance misuse.46, 47 Regardless of the causal mechanism behind the Hispanic–White difference in cigarette smoking increase, more culturally tailored substance misuse prevention is needed to reverse or mitigate smoking increase among the Hispanic population.

Our results show that East Asian respondents perceived a higher level of racial bias against their racial group than non-Hispanic White respondents and reported a higher chance of encountering racial discrimination than non-Hispanic White respondents. Anti-Asian discrimination has increased since the beginning of the pandemic, partly due to the negative stereotypes that Asians were more likely to carry the coronavirus, and the racist rhetoric of naming the coronavirus as “kung flu.”48 We found that racial discrimination was associated with increased psychological distress among East Asian population. Unlike the longstanding discrimination experienced by the Black population, the anti-Asian racism was particularly specific to the pandemic.37 More research on risks and resilience of Asian communities is needed to understand the mechanism through which anti-Asian racism leads to negative health consequences.

Our study is limited in that we did not measure more specific mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, or stress. Since a weighted proportion of 15.90% of respondents in our national sample reported serious distress, which is often significantly associated with more specific mental health conditions,49 more research is needed for surveillance of specific mental health conditions and to examine whether they could be triggered by racial discrimination or perceived racial bias during and after the pandemic. Another limitation is that the survey was conducted only in English and Spanish due to budget constraints, which might have created some nonresponse bias in sampling and measurement errors among some Asian respondents who preferred responding to the survey in an Asian language though our survey weights adjusted for the nonresponse bias. Moreover, the nature of our cross-sectional study means that we cannot interpret our observed associations as evidence for causal relationships. Though it is common in online-based survey studies and nonresponse bias is accounted for in the analysis, the low response rate (4.2%) is a limitation that may bias population estimates. Finally, the self-reported cigarette smoking behavior and alcohol consumption behavior prior to the pandemic, as measured in October 2020, could have a recall bias whereby the survey respondent did not recall their health behavior accurately. Recall bias also affects the measurement of perceived or encountered racial discrimination. Nonetheless, these recall biases were more likely to be underreported and thus may bias the results toward the null. Further study is needed to monitor whether the increased substance use will persist as the pandemic gradually wanes.

Our study shows that racism may play a significant role in population health outcomes, particularly under the stress of a pandemic. To tackle racial injustice, policies and culturally appropriate mental health interventions need to be developed and implemented to reduce the harmful effects of racism, promote health equity, and improve population health.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 13 kb)

Acknowledgements

The “Health, Ethnicity, and Pandemic” study was funded by the Center for Reducing Health Disparities at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, The Chinese Economists Society, and the Calvin J. Li Memorial Foundation.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lu Shi, Donglan Zhang and Emily Martin contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Jalloh MF, Li W, Bunnell RE, et al. Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(2):e000471. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litam SDA. “Take Your Kung-Flu Back to Wuhan”: counseling Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders with race-based trauma related to COVID-19. Professional Counselor. 2020;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.15241/sdal.10.2.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubey AD. The resurgence of cyber racism during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftereffects: analysis of sentiments and emotions in tweets. Original Paper. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(4):e19833. 10.2196/19833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Devakumar D, Shannon G, Bhopal SS, Abubakar I. Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses. The Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1194–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tessler H, Choi M, Kao G. The anxiety of being Asian American: hate crimes and negative biases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Crim Justice. 2020:1-11. 10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Quinn SC, Kumar S, Freimuth VS, Musa D, Casteneda-Angarita N, Kidwell K. Racial disparities in exposure, susceptibility, and access to health care in the US H1N1 influenza pandemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(2):285–293. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.188029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salazar LR, Garcia N, Diego-Medrano E, Castillo Y. Handbook of Research on Cyberbullying and Online Harassment in the Workplace. IGI Global; 2021. Workplace cyberbullying and cross-cultural differences: examining the application of intercultural communication theoretical perspectives; pp. 284–309. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews TA, Chen L, Chen Z, et al. Negative employment changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and psychological distress: evidence from a nationally representative survey in the U.S. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2021;10.1097/jom.0000000000002325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Montgomery R, Dennis JM, Ganesh N. Response rate calculation methodology for recruitment of a two-phase probability-based panel: the case of AmeriSpeak. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raj A, Johns NE, Barker KM, Silverman JG. Time from COVID-19 shutdown, gender-based violence exposure, and mental health outcomes among a state representative sample of California residents. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100520. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fell J. Underutilized strategies in traffic safety: results of a nationally representative survey. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2019;20(sup2):S57–S62. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2019.1654605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher CB, Tao X, Liu T, Giorgi S, Curtis B. COVID-related victimization, racial bias and employment and housing disruption increase mental health risk among U.S. Asian, Black and Latinx Adults. Original Research. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021 ;9. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.772236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.McCready AM, Rowan-Kenyon HT, Barone NI, Martínez Alemán AM. Students of color, mental health, and racialized aggressions on social media. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2021;58(2):179–195. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2020.1853555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health services research. 2019;54:1374–1388. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm HC. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290:113172. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian SV, Kim D, Kawachi I. Covariation in the socioeconomic determinants of self rated health and happiness: a multivariate multilevel analysis of individuals and communities in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):664–669. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.025742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, et al. The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(5):653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franceschini C, Musetti A, Zenesini C, et al. Poor sleep quality and its consequences on mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Original Research. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jehan S, Myers AK, Zizi F, et al. Sleep health disparity: the putative role of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Sleep Med Disord. 2018;2(5):127–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonzo R, Hussain J, Stranges S, Anderson KK. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2021;56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder E, Cai B, DeMuro C, Morrison MF, Ball W. A new single-item sleep quality scale: results of psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic primary insomnia and depression. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2018;14(11):1849–1857. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai JH-C, Thompson EA. Impact of social discrimination, job concerns, and social support on filipino immigrant worker mental health and substance use. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2013;56(9):1082–1094. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stolzenberg L, D’Alessio SJ, Eitle D. Race and cumulative discrimination in the prosecution of criminal defendants. Race and Justice. 2013;3(4):275–299. doi: 10.1177/2153368713500317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldman DS. The modern-day literacy test?: felon disenfranchisement and race discrimination. Stanford Law Review. 2004;57(2):611–655. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assari S, Miller RJ, Taylor RJ, Mouzon D, Keith V, Chatters LM. Discrimination fully mediates the effects of incarceration history on depressive symptoms and psychological distress among African American men. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(2):243–252. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0364-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayrl D, Saperstein A. When white people report racial discrimination: the role of region, religion, and politics. Social Science Research. 2013;42(3):742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesoff ED, Marziali ME, Martins SS. The estimated impact of state-level support for expanded delivery of substance use disorder treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addiction. 10.1111/add.15778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Collins RN, Mandel DR, Schywiola SS. Political identity over personal impact: early U.S. reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. Original Research. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.607639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;89:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren J, Feagin J. Face mask symbolism in anti-Asian hate crimes. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2021;44(5):746–758. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1826553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veldhuis CB, Nesoff ED, McKowen ALW, et al. Addressing the critical need for long-term mental health data during the COVID-19 pandemic: changes in mental health from April to September 2020. Preventive Medicine. 2021;146:106465. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health. 2019;40(1):105–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31(1):130–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JA, Zhang E, Liu CH. Potential impact of COVID-19–related racial discrimination on the health of Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(11):1624–1627. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goosby BJ, Cheadle JE, Mitchell C. Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2018;44(1):319–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corral I, Landrine H. Racial discrimination and health-promoting vs damaging behaviors among African-American adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(8):1176–1182. doi: 10.1177/1359105311435429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burmeister LF, Bimbaum D, Sheps SB. The merits of confidence intervals relative to hypothesis testing. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 1992;13(9):553–555. doi: 10.2307/30147184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guzman GG. Household income: 2016. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US …; 2017.

- 42.Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, LaVeist TA. Perceived racial discrimination and mental health in low-income, urban-dwelling Whites. International Journal of Health Services. 2013;43(2):267–280. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKnight-Eily LR, Okoro CA, Strine TW, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(5):162–166. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):443–458. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007)28:4<443::AID-JCOP6>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morey BN. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. American journal of public health. 2018;108(4):460–463. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Couch KA, Fairlie RW, Xu H. Early evidence of the impacts of COVID-19 on minority unemployment. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;192:104287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Current Drug Abuse Reviews. // 2011;4(1):4-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Walker D, Daniel AA. “China Virus” and “Kung-Flu”: a critical race case study of Asian American journalists’ experiences during COVID-19. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies. 2022;22(1):76–88. doi: 10.1177/15327086211055157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2021;295:113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 15 kb)

(DOCX 13 kb)