Abstract

SCH 56592 (posaconazole), a new triazole antifungal agent, was tested in vitro, and its activity was compared to that of itraconazole against 39 Aspergillus strains and to that of fluconazole against 275 Candida and 9 Cryptococcus strains. The SCH 56592 MICs for Aspergillus ranged from ≤0.002 to 0.5 μg/ml, and those of itraconazole ranged from ≤0.008 to 1 μg/ml. The SCH 56592 MICs for Candida and Cryptococcus strains ranged from ≤0.004 to 16 μg/ml, and those of fluconazole ranged from ≤0.062 to >64 μg/ml. SCH 56592 showed excellent activity against Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus in a pulmonary mouse infection model. When administered therapeutically, the 50% protective doses (PD50s) of SCH 56592 ranged from 3.6 to 29.9 mg/kg of body weight, while the PD50s of SCH 56592 administered prophylactically ranged from 0.9 to 9.0 mg/kg; itraconazole administered prophylactically was ineffective (PD50s, >75 mg/kg). SCH 56592 was also very efficacious against fluconazole-susceptible, -susceptible dose-dependent, or -resistant Candida albicans strains in immunocompetent or immunocompromised mouse models of systemic infection. The PD50s of SCH 56592 administered therapeutically ranged from 0.04 to 15.6 mg/kg, while the PD50s of SCH 56592 administered prophylactically ranged from 1.5 to 19.4 mg/kg. SCH 56592 has excellent potential for therapy against serious Aspergillus or Candida infections.

Of the estimated 100,000 known species of fungi, only about 180 have been shown to cause disease in humans, and only about 10% of these are encountered in most clinical settings (8). However, fungal infections have substantially increased over the past two decades, and invasive forms are important causes of morbidity and mortality (2, 16). The major increase in fungal infections is related to increased numbers of immunocompromised patients including those with human immunodeficiency virus infection-AIDS or cancer and bone marrow or solid organ transplant recipients, who are at risk of developing invasive fungal infections (5, 7, 12, 16). Disseminated candidiasis, pulmonary aspergillosis, and mycoses caused by emerging opportunistic fungi are the most common of these serious mycoses (7, 16, 38). As a result, there is a developing consensus that prophylactic therapy should be used for these high-risk patients (12). Fluconazole (FLC) is used for prevention of fungal infections in some of these patients, but it is not active against Aspergillus or other filamentous fungi. However, there is great concern about the development of resistant Candida due to prophylactic use of FLC (4, 10, 15, 18, 23, 35, 37). Clearly, alternative antifungal agents are needed for both therapeutic and prophylactic use. SCH 56592 (SCH; posaconazole) is a new triazole antifungal agent with broad-spectrum activity against fungi including strains of Aspergillus and Candida resistant to FLC (9, 11, 19, 24, 30, 33). This report describes the in vitro activity of SCH against Aspergillus and Candida and its efficacy in clinically relevant experimental infection models in mice with both prophylactic and therapeutic dosing regimens.

(Preliminary reports of this research were presented at the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 17 to 20 September 1995 [A. Cacciapuoti, R. Parmegiani, D. Loebenberg, B. Antonacci, E. L. Moss, Jr., F. Menzel, Jr., C. Norris, R. S. Hare, and G. H. Miller, Abstr. 35th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F66, p. 124, 1995], and the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Diego, Calif., 24 to 27 September 1998 [D. Loebenberg, F. Menzel, Jr., E. Corcoran, K. Raynor, J. Halpern, A. F. Cacciapuoti, and R. S. Hare, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-63, p. 469, 1998].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

White male CF1 mice from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, Mass.) were used in these studies. At the time of infection the mice in the pulmonary infection studies weighed 16 to 18 g and those in the systemic infection studies weighed 18 to 20 g.

Antifungal agents.

SCH was prepared at Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J., either as a micronized powder or as the clinically formulated suspension. For in vitro susceptibility tests the powder was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, while for in vivo studies it was prepared as a suspension in 0.4% (wt/vol) methylcellulose (MC) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) polysorbate 80 and 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl. The clinical suspension was diluted as needed in sterile water for injection (sWFI) and used for some in vivo studies. Both forms of SCH were previously tested in our laboratory and were found to have the same in vivo efficacy. FLC powder and Diflucan oral suspension were obtained from Pfizer, Inc., Kent, England. For in vivo use, FLC powder was prepared in MC and Diflucan was diluted as needed in sWFI. Itraconazole (ITC) powder and Sporanox oral solution were obtained from Janssen Pharmaceutica Inc., Beerse, Belgium. For in vivo use only Sporanox was used, and it was diluted as needed in hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; 40% [wt/vol] in water; Cerestar USA, Inc., Hammond, Ind.).

In vitro antifungal activity.

All strains of Aspergillus, Candida, and Cryptococcus were from the Schering-Plough Research Institute fungal culture collection. The MICs for Candida and Cryptococcus strains were determined by the broth microdilution method according to the procedures of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) described in document M27-A, Reference Method for Broth Dilution Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts (26), and those for Aspergillus strains were determined by the procedures described in NCCLS document M38-P, Reference Method for Broth Dilution Susceptibility Testing of Conidium-Forming Filamentous Fungi (27).

Therapeutic activity against pulmonary aspergillosis.

Aspergillus fumigatus strains ND152, ND158, ND159, and ND164 and Aspergillus flavus strains ND83, ND134, ND149, and ND168 were grown on malt extract agar for 13 days at 25°C in an inhalation chamber. Mice were compromised with subcutaneous cortisone acetate (100 mg/kg of body weight once daily on the day before infection and the following 2 days) and were exposed to a spore cloud for 0.5 to 1 min in the chamber on the second day of compromise (day 0), as described previously (20). Oral administration of SCH (dose range, 40 to 2.5 mg/kg; 10 mice per dose) began 24 h postinfection, and SCH was given once daily for 4 days. Control mice were administered MC. The 50% protective dose (PD50), defined as the dose which allowed 50% survival, was calculated from the data for the surviving mice on day 7 postinfection by the Hill equation (1).

Prophylactic activity against pulmonary aspergillosis.

A. flavus ND83 or A. fumigatus ND152 or ND158 was grown as described above. Mice were compromised with cortisone acetate and were infected as described above. Cortisone acetate was also administered on days 6 and 12 postinfection to maintain immunosuppression. Oral administration of drugs (25 to 0.025 mg/kg) to groups of eight mice was once (SCH) or three times (ITC) daily beginning at 24 h preinfection (prophylactic) and continuing through day 7 postinfection. Control mice were administered MC or HPβCD. PD50s were determined as described above by use of the data for the surviving mice on day 7 postinfection. Fungal counts in the lungs of mice that survived at the termination of the experiments were determined by spreading aliquots of homogenized suspensions onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA).

Therapeutic activity against systemic candidiasis.

Candida albicans strains C43, C65, C72, C84, C260, C284, C286, C288, and C342 were grown for 48 h on SDA, and inocula were prepared as described previously (3). Normal mice or immunocompromised mice (which were immunocompromised by exposure to 500 rads 3 days prior to infection in a Shepherd Mark I cesium gamma irradiator) were infected on day 0 by injecting 2.5 × 106 to 1 × 107 CFU as a saline suspension into the tail vein. Groups of 10 mice each were treated with SCH (100 to 0.063 mg/kg) or FLC (200 to 0.63 mg/kg) orally once daily for 4 days beginning at 4 h postinfection. Control mice were administered MC or sWFI. PD50s, calculated as described above, were determined by use of the data for the surviving mice on day 4 postinfection. Survivors were killed 24 h after the last treatment, and the fungal counts in the kidneys were determined as described previously (3).

Prophylactic activity against systemic candidiasis.

C. albicans strains C43, C284, C288, and C310 were grown as described above. Groups of 10 mice each were immunocompromised, infected (5 × 106 CFU) as described above, and given SCH (50 to 0.025 mg/kg) or FLC (250 to 0.025 mg/kg) orally once daily beginning at 24 h preinfection and continuing through day 7 postinfection. Control mice were administered sWFI. PD50s were calculated by use of the data for the surviving mice on day 7 postinfection as described above.

Statistical analysis.

A logistic model was used to determine differences between PD50s by using their 95% confidence bounds. A chi-square test or logistic model was used to determine if the levels of survival among mice in the treatment groups were significantly different from those among mice in the control group. Comparison of survival-versus-time curves in prophylactic activity experiments with mice to determine efficacy differences between drugs at various dose levels was done by log-rank tests. A chi-square test was performed to show significant differences between treatment groups in the clearance of Aspergillus from the lungs of the mice.

Statement of animal care and use.

These studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (28) and the Animal Welfare Act in an Association for Assessment Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited program.

RESULTS

In vitro antifungal activity.

The in vitro activities of SCH and ITC against 39 strains of Aspergillus are shown in Table 1. The MICs of SCH and ITC ranged from ≤0.002 to 0.5 and ≤0.008 to 1 μg/ml, respectively. Against A. flavus, A. fumigatus, and other Aspergillus species, SCH was overall more active (MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited [MIC50s], 0.008, ≤0.002, and 0.016 μg/ml, respectively; MIC90s, 0.125, 0.031, and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively) than ITC (MIC50s, 0.125 μg/ml; MIC90s, 0.25, 0.25, and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively).

TABLE 1.

In vitro activities of SCH, ITC, and FLC against Aspergillus, Candida, and Cryptococcus

| Species | No. of isolates | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCH

|

ITC

|

FLC

|

||||||||

| Range | 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| A. flavus | 11 | ≤0.002–0.125 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 0.008–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | NDa | ND | ND |

| A. fumigatus | 17 | ≤0.002–0.062 | ≤0.002 | 0.031 | 0.004–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND |

| Aspergillus speciesb | 11 | ≤0.002–0.5 | 0.016 | 0.5 | ≤0.008–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| C. albicans | 156 | ≤0.004–16 | ≤0.004 | 0.125 | ND | ND | ND | 0.062–>64 | 0.125 | 16 |

| C. tropicalis | 20 | ≤0.004–8 | ≤0.016 | 2 | ND | ND | ND | 0.125–>64 | 0.25 | >64 |

| C. glabrata | 20 | ≤0.016–2 | 0.25 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | 0.5–>64 | 4 | 64 |

| C. krusei | 20 | 0.062–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ND | ND | ND | 8–64 | 32 | 64 |

| Candida speciesc | 59 | ≤0.004–1 | ≤0.016 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ≤0.062–>64 | 0.25 | 16 |

| C. neoformans | 9 | ≤0.016–0.5 | 0.062 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ≤0.062–16 | 2 | ND |

ND, not determined.

Includes the following species and number of strains: A. niger, n = 5; A. terreus, n = 4; A. nidulans, n = 1; species not identified, n = 1.

Includes the following species and number of strains: C. kefyr, n = 7; C. parapsilosis, n = 7; C. guilliermondii, n = 6; C. dubliniensis, n = 5; C. lusitaniae, n = 5; C. lambica, n = 3; C. rugosa, n = 3; C. famata, n = 2; C. inconspicua, n = 2; C. pseudotropicalis, n = 1; C. stellatoidea, n = 1; species not identified, n = 17.

The in vitro activities of SCH and FLC against 275 strains of Candida, including strains which were susceptible (S), susceptible dose-dependent (S-DD), or resistant (R) to FLC on the basis of NCCLS breakpoints (26), are also shown in Table 1. The MICs of SCH and FLC ranged from ≤0.004 to 16 and ≤0.062 to >64 μg/ml, respectively. The potent activity of SCH against FLC-S, FLC-S-DD, and FLC-R strains was reflected in the MIC90s of SCH for C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and other Candida species (SCH MIC90s, 0.125, 2, 1, 0.5, and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively compared to those of FLC (16, >64, 64, 64, and 16 μg/ml, respectively). The only resistance to SCH observed was by one strain of C. albicans, for which the MIC was 16 μg/ml, and two strains of C. albicans and one of C. tropicalis, for which the MICs were 8 μg/ml.

SCH was also more active than FLC against nine strains of Cryptococcus neoformans (MIC50s, 0.062 and 2 μg/ml, respectively) (Table 1).

Therapeutic activity against pulmonary aspergillosis.

The in vivo efficacy of SCH administered therapeutically against pulmonary aspergillosis in immunocompromised mice was examined by using four strains each of A. fumigatus and A. flavus. The MICs of SCH were ≤0.002 μg/ml for A. fumigatus ND158, ND159, and ND164 and A. flavus ND134 and ND168, while the SCH MICs were 0.0625, 0.008, and 0.125 μg/ml for A. fumigatus ND152 and A. flavus ND83 and ND149, respectively. PD50s on the basis of the data for the surviving mice at 7 days postinfection ranged from 3.6 to 29.9 mg/kg against A. fumigatus and from 4.8 to 6.5 mg/kg against A. flavus (Table 2), and the survival results showed significant differences between treatment groups and controls (P < 0.05). The highest PD50s were observed against A. fumigatus ND158 (29.9 mg/kg) and ND164 (22.2 mg/kg), although these strains were clearly susceptible to SCH in vitro. All control mice died within 3 to 8 days postinfection.

TABLE 2.

Efficacy of therapeutic and prophylactic administration of SCH against pulmonary Aspergillus infections in immunocompromised mice

| Strain | PD50 (mg/kg) on day 7

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic administration of SCHa | Prophylactic administration ofb:

|

||

| SCH | ITC | ||

| A. fumigatus | |||

| ND152 | 3.6 | 2.2, 0.9c | >75, >75c |

| ND158 | 29.9 | 2.6 | >75 |

| ND159 | 10.9 | NDd | ND |

| ND164 | 22.2 | ND | ND |

| A. flavus | |||

| ND83 | 5.7 | 3.9, 9.0c | >75, >75c |

| ND134 | 4.8 | ND | ND |

| ND149 | 6.5 | ND | ND |

| ND168 | 5.6 | ND | ND |

ITC was not tested therapeutically.

The PD50 was based on the total daily dose.

Results from experiments 1 and 2.

ND, not done.

Prophylactic activity against pulmonary aspergillosis.

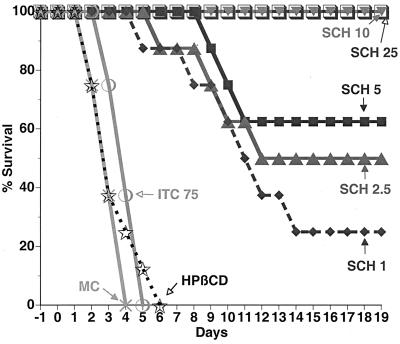

The in vivo efficacy of SCH against Aspergillus in mice was further investigated with a clinically relevant infection model characterized by prophylactic administration preinfection, followed by continued treatment postinfection. SCH administered once daily was compared to ITC administered three times daily, and the results are shown in Table 2. SCH (PD50 range, 0.9 to 9.0 mg/kg) was efficacious against strains of A. fumigatus and A. flavus, while ITC failed to protect the mice (PD50s, >75 mg/kg). The survival-versus-time graph for A. fumigatus ND152 is shown in Fig. 1. Against this strain, SCH at 25 and 10 mg/kg protected 100% of mice for 19 days, while control mice and those administered ITC (total daily dose, 75 mg/kg) were all dead by days 4 to 6. SCH at 25, 10, 5, 2.5, and 1 mg/kg was significantly more effective than ITC at 75 mg/kg (P < 0.01). The survival-versus-time graphs for the other Aspergillus strains tested (data not shown) showed that SCH had significant efficacy compared to that of ITC at 75 mg/kg (P < 0.01).

FIG. 1.

Effects of SCH (administered orally once daily) and ITC (administered orally three times daily) administered in a prophylactic regimen 1 day preinfection to 7 days postinfection on survival of immunocompromised mice infected (by 1 min of exposure to spores on day 0) with A. fumigatus ND152 by the pulmonary route. Total daily doses (in milligrams per kilogram) are indicated. Controls were administered MC or HPβCD.

SCH also appeared to be more effective in clearing the infection from the lungs of mice infected with A. fumigatus than those of mice infected with A. flavus. At 25 and 10 mg/kg, the lungs of 65% of mice infected with A. fumigatus ND152 or ND158 were sterilized, but the lungs of only 3% (one mouse) of those infected with A. flavus ND83 were sterilized (P < 0.01) (Table 3). This differential effect against A. fumigatus and A. flavus was also evident at the lower doses.

TABLE 3.

Proportion of mice infected with Aspergillus with negative lung cultures following prophylactic treatment with SCH 56592

| SCH dose (mg/kg) | Strain | Total no. of micea | % (no.) of mice with negative lung culturesb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | A. fumigatus ND152 | 16 | 75 (12) |

| A. fumigatus ND158 | 8 | 62 (5) | |

| A. flavus ND83 | 16 | 6 (1) | |

| 10 | A. fumigatus ND152 | 16 | 63 (10) |

| A. fumigatus ND158 | 8 | 50 (4) | |

| A. flavus ND83 | 16 | 0 | |

| 5 | A. fumigatus ND152 | 16 | 31 (5) |

| A. fumigatus ND158 | 8 | 50 (4) | |

| A. flavus ND83 | 16 | 6 (1) | |

| 2.5 | A. fumigatus ND152 | 16 | 6 (1) |

| A. fumigatus ND158 | 8 | 0 | |

| A. flavus ND83 | 16 | 0 |

The surviving mice were killed, and lung homogenates were diluted and spread onto SDA plates. The totals include the mice from two experiments with strains ND152 and ND83 and one experiment with strain ND158.

No growth was detected on SDA plates with a 101 dilution.

Therapeutic activity against systemic candidiasis.

The in vivo efficacy of SCH administered therapeutically against systemic candidiasis was examined in immunocompetent and/or immunocompromised mouse models by using nine strains of C. albicans. Included were five FLC-S strains (strains C43, C65, C84, C72, and C286, for which FLC MICs were 0.125, 0.25, 0.25, 0.25, and 4 μg/ml, respectively), two FLC-S-DD strains (strains C288 and C342, for which FLC MICs were 32 and 16 μg/ml, respectively), and two FLC-R strains (strains C260 and C284, for which FLC MICs were >64 μg/ml). The SCH MICs for the strains ranged from ≤0.004 to 0.5 μg/ml; however, the SCH MIC for C260 was 16 μg/ml. The results of these in vivo studies are shown in Table 4. SCH was active against all strains tested, but the PD50 against C260 (15.6 mg/kg) was higher than those against the other eight strains (PD50 range, 0.04 to 7.1 mg/kg). FLC was active against the FLC-S strains (PD50 range, 0.9 to 6.1 mg/kg), less active against the FLC-S-DD strains (PD50s, 25 and 30.5 mg/kg, respectively), and inactive against the FLC-R strains (PD50s, 342 and 417 mg/kg, respectively). In these studies, 80 to 100% of control mice were dead by 4 days postinfection. Statistical analysis of the PD50s of SCH and FLC on the basis of their 95% confidence bounds indicated that SCH was significantly more active than FLC against FLZ-S-DD strain C288 and the FLC-R strains (P < 0.05). The in vivo efficacy of SCH was further reflected in the reduced fungal burdens in the kidneys of the surviving mice (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Efficacies of therapeutic and prophylactic administration of SCH and FLC (both once daily) against systemic C. albicans infections in mice

| C. albicans susceptibility and strain | Mice | PD50 (mg/kg)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic administration (day 4)a

|

Prophylactic administration (day 7)b

|

||||

| SCH | FLC | SCH | FLC | ||

| FLC S | |||||

| C43 | Normal | 0.3 | 1.2 | NDc | ND |

| C43 | Irradiated | 1.7 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 5.3 |

| C84 | Normal | 0.6 | 4.3 | ND | ND |

| C286 | Normal | 0.1 | 0.9 | ND | ND |

| C65 | Irradiated | 0.04 | 2.6 | ND | ND |

| C72 | Irradiated | 0.6 | 2.4 | ND | ND |

| FLC S-DD | |||||

| C288 | Normal | 0.6 | 25 | ND | ND |

| C288 | Irradiated | ND | ND | 7.8 | >25 |

| C342 | Normal | 7.1 | 30.5 | ND | ND |

| FLC R | |||||

| C284 | Normal | 4.1 | 342 | ND | ND |

| C284 | Irradiated | ND | ND | 7.0 | 431 |

| C260 | Normal | 15.6 | 417 | ND | ND |

| C310 | Irradiated | ND | ND | 19.4 | 204 |

PD50 determined on day 4 postinfection.

PD50 determined on day 7 postinfection.

ND, not done.

Prophylactic activity against systemic candidiasis.

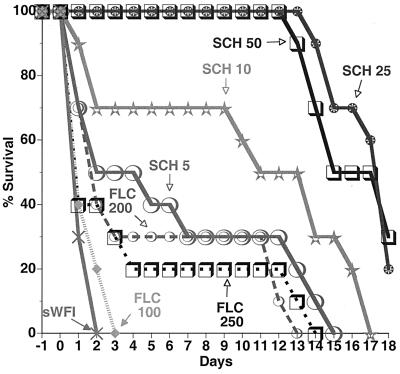

A systemic infection model with immunocompromised mice was used to evaluate the prophylactic efficacy of SCH against C. albicans. In these experiments, SCH was compared to FLC (Diflucan) administered once daily beginning at 24 h preinfection and continuing to day 7 postinfection against C. albicans C43 (FLC-S), C288 (FLC-S-DD), C284 (FLC-R), and C310 (FLC-R; FLC MIC, >64 μg/ml). The results in Table 4 show that SCH was efficacious against all strains (PD50 range, 1.5 to 19.4 mg/kg), while FLC was active against C43 (PD50, 5.3 mg/kg) but not against the less susceptible and resistant strains (PD50s, >25, 431, and 204 mg/kg against strains C288, C284, and C310, respectively). The survival-versus-time graph for FLC-R strain C284 shows that SCH at 50 and 25 mg/kg protected 100% of mice for 12 days postinfection, while FLC at 250 mg/kg was ineffective (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Other survival-versus-time graphs (data not shown) indicated that SCH at 10 and 25 mg/kg was more efficacious than FLZ at 25 mg/kg against strain C288 and FLZ at 100 mg/kg against strain C310, respectively (P < 0.01 for each comparison).

FIG. 2.

Effect of SCH and FLC (administered oral once daily) administered in a prophylactic regimen 1 day preinfection to 7 days postinfection on survival of immunocompromised mice systemically infected (with 5 × 106 CFU/mouse on day 0) with C. albicans C284 (FLC R). Dose levels (in milligrams per kilogram) are indicated. Controls were administered sWFI.

DISCUSSION

The potent in vitro activity of SCH against Aspergillus, Candida, and Cryptococcus was shown in the study described in this report. Other investigators have found SCH to have broad-spectrum in vitro activity not only against these fungi but also against Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, and other filamentous and dimorphic fungi (6, 9, 11, 19, 22, 24, 30, 32, 33, 34, 36).

This report also highlights the in vivo efficacy of SCH against pulmonary A. fumigatus and A. flavus strains and systemic C. albicans strains (including strains with reduced susceptibility or resistance to FLC) in normal or immunocompromised mouse models of infection. In these studies, SCH was effective whether it was initially administered therapeutically after infection or prophylactically before infection. SCH was also reported by Graybill et al. (13) to be more effective than amphotericin B against invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in mice. In addition, Oakley et al. (31) found SCH to be more effective than ITC against disseminated aspergillosis in mice, while Kirkpatrick et al. (17) reported that SCH is more effective than ITC and is as effective as amphotericin B for the clearance of Aspergillus from tissues in a rabbit model of invasive aspergillosis.

In experimental infection models SCH was active not only against the more common opportunistic pathogens like Aspergillus and Candida but also against the less common fungi. Perfect et al. (32) reported that the activity of SCH was comparable to that of FLC against C. neoformans in a rabbit model of cryptococcal meningitis. Sugar and Liu (36) found that SCH was more effective than ITC and that the activity of SCH was similar to that of amphotericin B in prolonging survival and sterilizing the lungs of mice infected with B. dermatitidis. Lutz et al. (22) showed that SCH, but not FLC or ITC, cured survivors in a mouse model of systemic coccidioidomycosis. Connolly et al. (6) demonstrated in a pulmonary model of histoplasmosis in mice that SCH was more active than ITC and that the activity of SCH was similar to that of amphotericin B for sterilization of the lungs and spleens. SCH was also shown to increase the rate of survival and reduce the organ burdens in mice infected with Fusarium solani (21).

Pulmonary aspergillosis and disseminated candidiasis are recognized as serious complications and the leading causes of death among immunosuppressed patients, especially those with AIDS and those who have received bone marrow or liver transplants, for which only inadequate treatment or prophylaxis is available (2, 5, 7, 12, 16). Although prophylaxis with FLC is used to prevent fungal infections in certain patient populations, there are major concerns about the development of resistance (4, 12, 15, 18, 23, 35, 37). ITC was recently evaluated for its prophylactic activity in a clinical trial and was found to reduce the incidence of systemic Candida infections and related deaths in neutropenic patients; however, it had no apparent efficacy in the prevention of Aspergillus infections (25). The need for more potent, broader-spectrum, longer-acting antifungal agents which are not associated with the emergence of resistance clearly exists. The broad-spectrum activity and experimental efficacy of SCH suggest that it could be effective for the treatment and prevention of severe fungal infections, such as aspergillosis and azole-refractory candidiasis, in high-risk individuals. In addition, the development of resistance to SCH may be a less likely event than with the development of resistance to other azole antifungal agents. Although SCH, like other azoles, blocks fungal sterol biosynthesis by inhibiting C-14 demethylation of lanosterol (H. Munayyer, K. J. Shaw, R. S. Hare, B. Salisbury, L. Heimark, B. Pramanik, and J. R. Greene, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F92, p. 115, 1996), Sanglard et al. (D. Sanglard, F. Ischer, and J. Bille, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-11, p. 48, 1997) found that SCH was insensitive to mutations in cytochromes known to hinder the binding of other azole drugs. However, the C. albicans ABC transporters Cdr1 and Cdr2 but not the major facilitators Ben and Flu1 were able to use SCH as a substrate when they were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sanglard et al., 37th ICAAC).

Preliminary pharmacodynamic analyses suggested that the area under the concentration-time curve is the most important factor in determining the efficacy of SCH in experimental infection models (G. H. Miller, D. Loebenberg, B. Antonacci, A. Cacciapuoti, E. L. Moss, Jr., F. Menzel, Jr., M. Michalski, C. Norris, R. Parmegiani, T. Yarosh-Tomaine, B. Yaremko, and R. S. Hare, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F94, p. 116, 1996). Nomeir et al. (29) reported that the concentrations of SCH in serum remained above the MIC for most filamentous fungi and yeasts 24 h following the administration of a single oral dose to various animal species, suggesting that once-daily administration of the compound should be a therapeutically effective dosage regimen. In mice, the mean concentrations of SCH in serum were >2 μg/ml for at least 12 h after oral administration of 20 mg/kg. In addition, SCH achieved a maximum concentration in serum of 6.3 μg/ml at 1 h after dosing, with an area under the concentration-time curve of 63.7 μg · h/ml and bioavailability of 47%. Dose-related increases in both the area under the concentration-time curve and the maximum concentration in serum were also observed in mice over a dose range of 20 to 160 mg/kg. SCH is being evaluated in Phase II and III clinical trials. Preliminary results from a phase II clinical trial indicated that SCH is an effective and well-tolerated alternative treatment for oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients unresponsive to FLC or ITC (D. Skiest, D. Ward, A. Northland, J. Reynes, and W. Greaves, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1162, p. 491, 1999).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Ferdous Gheyas for statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes D, van Ogtrop M. Characterization and quantitation of the pharmacodynamics of fluconazole in a neutropenic murine disseminated candidiasis infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2116–2120. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong D. Problems in management of opportunistic fungal diseases. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:S1591–S1599. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_7.s1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacciapuoti A, Loebenberg D, Parmegiani R, Antonacci B, Norris C, Moss E L, Jr, Menzel F, Jr, Yarosh-Tomaine T, Hare R S, Miller G H. Comparison of SCH 39304, fluconazole, and ketoconazole for treatment of systemic infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:64–67. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron M L, Schell W A, Bruch S, Bartlett J A, Waskin H A, Perfect J R. Correlation of in vitro fluconazole resistance of Candida isolates in relation to therapy and symptoms of individuals seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2449–2453. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castaldo P, Stratta R J, Wood R P, Markin R S, Patil K D, Shaefer M S, Langnas A L, Reed E C, Li S, Pillen T J, Shaw B W., Jr Clinical spectrum of fungal infections after orthotopic liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 1991;126:149–156. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410260033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly P, Wheat J, Schnizlein-Bick C, Durkin M, Kohler S, Smedema M, Goldberg J, Brizendine E, Loebenberg D. Comparison of a new triazole antifungal agent, Schering 56592, with itraconazole and amphotericin B for treatment of histoplasmosis in immunocompetent mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:322–328. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denning D. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781–805. doi: 10.1086/513943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emmons C W. Medical mycology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea and Febiger; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinel-Ingroff A. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH 56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;36:2950–2956. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2950-2956.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan-Havard P, Capano D, Smith S M, Mangia A, Eng R H K. Development of resistance in Candida isolates from patients receiving prolonged antifungal therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2302–2305. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galgiani J N, Lewis M L. In vitro studies of activities of the antifungal triazoles SCH 56592 and itraconazole against Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and other pathogenic yeasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:180–183. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman J L, Winston D J, Greenfield R A, Chandrasekar P H, Fox B, Kaizer H, Shadduck R K, Shea T C, Stiff P, Friedman D J, Powderly W G, Silber J L, Horowitz H, Lichtin A, Wolff S N, Mangan K F, Silver S M, Weisdorf D, Ho W G, Gilbert G, Buell D. A controlled trial of fluconazole to prevent fungal infections in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. N Eng J Med. 1992;326:845–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203263261301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graybill J R, Bocanegra R, Najvar L K, Luther M F, Loebenberg D. SCH 56592 treatment of murine invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:539–542. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta A K, Sauder D N, Shear N H. Antifungal agents: an overview. Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:911–933. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havlir D V, Dube M P, McCutchan J A, Forthal D N, Kemper C A, Dunne M W, Parenti D M, Kumar P N, White A C, Jr, Witt M D, Nightingale S D, Sepkowitz K A, MacGregor R R, Cheeseman S H, Torriani F J, Zelasky M T, Sattler F R, Bozzette S A. Prophylaxis with weekly versus daily fluconazole for fungal infections in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1369–1375. doi: 10.1086/515018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoo S H, Denning D W. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:S41–S48. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.supplement_1.s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkpatrick W R, McAtee R K, Fothergill A W, Loebenberg D, Rinaldi M G, Patterson T F. Efficacy of SCH 56592 in a rabbit model of invasive aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:780–782. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.780-782.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law D, Moore C B, Wardle H M, Ganguli L A, Keaney M G L, Denning D W. High prevalence of antifungal resistance in Candida spp. from patients with AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:659–668. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law D, Moore C B, Denning D W. Activity of SCH 56592 compared with those of fluconazole and itraconazole against Candida spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2310–2311. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Parmegiani R, Moss E L, Jr, Menzel F, Jr, Antonacci B, Norris C, Yarosh-Tomaine T, Hare R S, Miller G H. In vitro and in vivo activities of SCH 42427, the active enantiomer of the antifungal agent SCH 39304. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:498–501. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lozano-Chiu M, Arikan S, Paetznick V L, Anaissie E J, Loebenberg D, Rex J H. Treatment of murine fusariosis with SCH 56592. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:589–591. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutz J E, Clemons K V, Aristizabal B H, Stevens D A. Activity of the triazole SCH 56592 against disseminated murine coccidioidomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1558–1561. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maenza J R, Merz W G, Romagnoli M J, Keruly J C, Moore R D, Gallant J E. Infection due to fluconazole-resistant Candida in patients with AIDS: prevalence and microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:28–34. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marco F, Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Jones R N. In vitro activity of a new triazole antifungal agent, SCH 56592, against clinical isolates of filamentous fungi. Mycopathologia. 1998;141:73–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1006970503053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menichetti F, Del Favero A, Martino P, Bucaneve G, Micozzi A, Girmenia C, Barbabietola G, Pagano L, Leoni P, Specchia G, Caiozzo A, Raimondi R, Mandelli F. Itraconazole oral solution as prophylaxis for fungal infections in neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:250–255. doi: 10.1086/515129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard. Document M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi. Proposed standard. Document M38-P. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Research Council. NIH guide to the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nomeir A A, Kumari P, Hilbert M J, Gupta S, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Hare R, Miller G H, Lin C-C, Cayen M N. Pharmacokinetics of SCH 56592, a new azole broad-spectrum antifungal agent in mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, and cynomolgus monkeys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:727–731. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.727-731.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oakley K L, Moore C B, Denning D W. In vitro activity of SCH 56592 and comparison with activities of amphotericin B and itraconazole against Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1124–1126. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oakley K L, Morrissey G, Denning D W. Efficacy of SCH 56592 in a temporarily neutropenic murine model of invasive aspergillosis with an itraconazole-susceptible and an itraconazole-resistant isolate of Aspergillus fumogatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1504–1507. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perfect J R, Cox G M, Dodge R K, Schell W A. In vitro and in vivo efficacies of the azole SCH56592 against Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1910–1913. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaller M A, Messer S, Jones R N. Activity of a new triazole, SCH 56592, compared with those of four other antifungal agents tested against clinical isolates of Candida spp. and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:233–235. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Hollis R J, Jones R N, Doern G V, Brandt M E, Hajjeh R A. In vitro susceptibilities of Candida bloodstream isolates to the new triazole antifungal agents BMS-207147, SCH 56592, and voriconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3242–3244. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sangeorzan J A, Bradley S F, Xiaogang H, Zarins L T, Ridenour G L, Tiballi R N, Kauffman C A. Epidemiology of oral candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: colonization, infection, treatment, and emergence of fluconazole resistance. Am J Med. 1994;97:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugar A M, Liu X-P. In vitro and in vivo activities of SCH 56592 against Blastomyces dermatitidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1314–1316. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Troillet N, Durussel C, Bille J, Glauser M P, Chave J P. Correlation between in vitro susceptibility of Candida albicans and fluconazole-resistant oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF01992164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh T J, Pizzo P A. Nosocomial fungal infections: a classification for hospital-acquired infections and mycoses arising from endogenous flora and reactivation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:517–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]