Abstract

An important and often overlooked subpopulation of cancer survivors is individuals who are diagnosed with or progress to advanced or metastatic cancer. Living longer with advanced or metastatic cancer often comes with a cost of burdensome physical and psychosocial symptoms and complex care needs; however, research is limited on this population. Thus, in May 2021, the National Cancer Institute convened subject matter experts, researchers, clinicians, survivors, and advocates for a 2-day virtual meeting. The purpose of this report is to provide a summary of the evidence gaps identified by subject matter experts and attendees and key opportunities identified by the National Cancer Institute in 5 research areas: epidemiology and surveillance, symptom management, psychosocial research, health-care delivery, and health behaviors. Identified gaps and opportunities include the need to develop new strategies to estimate the number of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers; understand and address emerging symptom trajectories; improve prognostic understanding and communication between providers, patients, and caregivers; develop and test models of comprehensive survivorship care tailored to these populations; and assess patient and provider preferences for health behavior discussions throughout the survivorship trajectory. To best address the needs of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancer and to deliver comprehensive evidence-based quality care, research is urgently needed to fill evidence gaps, and it is essential to incorporate the survivor perspective. Developing such an evidence base is critical to inform policy and practice.

The Office of Cancer Survivorship of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines a cancer survivor as any individual with a history of cancer from the time of diagnosis through the end of life (1). Using this definition, there are currently more than 16 million cancer survivors in the United States, and this number is expected to grow to more than 26 million by 2040 (2).

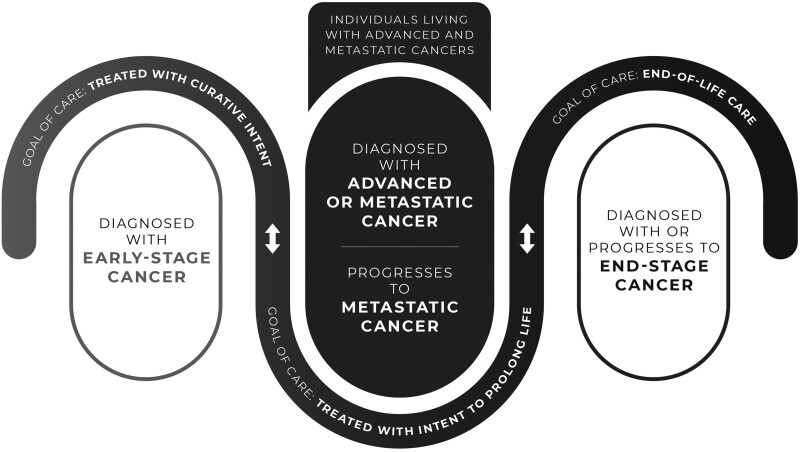

An important and often overlooked subpopulation of cancer survivors is individuals who are diagnosed with or progress to advanced or metastatic cancer. Historically, the goal of care for these individuals was primarily focused on palliation of symptoms and end-of-life care, given their poor prognosis and outcomes (3). In more recent years, however, with advances in treatment leading to increased survival rates for cancer survivors overall (4,5), a growing number of individuals diagnosed with advanced and metastatic cancer are living longer with their cancer. Goals of care for these individuals are often very different from individuals diagnosed with early-stage cancer who are likely treated with curative intent (Figure 1). For example, individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer may cycle on and off treatments to prolong life but without expectation of curing their cancer. They may also have periods with and without active disease for many years.

Figure 1.

The population of cancer survivors living with advanced and metastatic cancer within the context of the phases of cancer survivorship.

Living longer with advanced or metastatic cancer often comes with a cost of burdensome physical and psychosocial symptoms, complex care needs that include care coordination among multiple providers, and increased caregiver support (6,7). In addition, individuals living with metastatic or advanced cancer often experience great uncertainty about their prognosis (8) and fear of disease progression. The group of individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer is heterogenous in terms of cancer type, treatments received, prognosis, and outcomes. These factors must be considered when studying this subpopulation of cancer survivors.

Since the creation of the Office of Cancer Survivorship in 1996, NCI has demonstrated a commitment to funding survivorship science that seeks to understand and improve the health and well-being of cancer survivors and their caregivers (9). Much of the funded research, however, has focused on cancer survivors who are posttreatment and do not have detectable disease. Recently, we published a portfolio analysis of National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded grants focused on individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer. The analysis demonstrated a need for studies focused on the longitudinal examination of symptom trajectories, innovative models of care, the impact of newer therapies on survivor needs, financial hardship, and caregiver support in this subpopulation of cancer survivors (10).

NCI recognized a need to gather stakeholders with interest in advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship. In May 2021, NCI held a 2-day virtual meeting, which was open to the public, with the goals of 1) defining the current state of advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship research; 2) identifying health and supportive care needs of people living with advanced and metastatic disease; and 3) discussing gaps and opportunities for research on advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship (11). More than 300 individuals attended the meeting, including researchers (62%); clinicians (18%); patients, survivors, or caregivers (6%); advocates (4%); and other stakeholders (10 %).

The meeting began with a keynote presentation outlining the changing landscape of care for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers. It was followed by a survivor panel with 4 individuals (3 women, 1 man) diagnosed with advanced or metastatic cancer, who were chosen to represent multiple cancer types (breast, colorectal, and neuroendocrine), ages at diagnosis, and unique survivorship experiences (11). The remainder of the meeting was organized into 5 sessions covering broad scientific areas, which were identified through an examination of current literature and the NIH grant portfolio: epidemiology and surveillance, symptom management, psychosocial needs, health-care delivery, and health behaviors. Each session included 2-3 presentations from subject matter experts followed by a small group discussion, with additional extramural scientists and a survivor, the goal of which was to identify gaps in knowledge pertaining to that scientific area. Subject matter experts were identified through a review of the NCI-funded grant portfolio, as well as a search of relevant literature. Specific efforts were taken to include experts and survivors with diverse backgrounds, including variation by race, ethnicity, sex, geographic area, and representation of multiple care delivery systems (eg, academic and community settings).

At multiple points throughout the meeting, attendees were encouraged to submit questions and ideas about scientific gap areas and opportunities for future research. Evidence gaps (identified through subject matter expert presentations, attendee ideas, and topics that emerged in each session discussion) were discussed in a subsequent meeting of NCI staff to determine key opportunities.

The purpose of this report is to provide a summary of the evidence gaps identified by subject matter experts and attendees and key opportunities identified by NCI. We present the findings below for each scientific session topic, followed by a discussion of cross-cutting issues and synergies between topic areas.

Note on Terminology

Throughout the meeting, participants acknowledged that the term survivor may not resonate for all people who have a history of cancer, and this may be even more true for individuals who are living with advanced or metastatic cancer. Several terms used to identify this subpopulation of cancer survivors were mentioned, such as thriver, metavivor, metastatic survivor. However, it was agreed on by patient and survivor meeting participants that one term does not fit all. Therefore, we use in this article the label “individuals living with metastatic or advanced cancer” for this subpopulation of cancer survivors.

Presentation of Evidence Gaps and Key Next Steps

Epidemiology and Surveillance

Evidence Gaps. Subject matter experts and attendees indicated that there is a need to develop methods to identify and enumerate survivors diagnosed with or who have progressed to metastatic cancer in registries and other large databases. This information is essential for surveillance, to identify eligible individuals for study recruitment, and to document disease progression in observational and interventional research. Further, speakers and discussants commented on the very limited research on factors (both modifiable and nonmodifiable) associated with longer-term survival after an advanced or metastatic cancer diagnosis and the need for epidemiologic research investigating these factors. Subject matter experts further recognized that epidemiologic studies are needed to identify and track physical and psychological symptoms (including symptom trajectories), adverse effects, and long-term outcomes related to an advanced or metastatic cancer diagnosis and its treatments. Collection of complete treatment and toxicity data in epidemiologic research studies pertaining to these populations is critical.

Key Opportunities. Several important next steps were identified, including the need to develop new approaches and modeling strategies that use data from cancer registries, electronic health records (EHR), cancer survivor cohort studies, and clinical trials to estimate the number of individuals living with metastatic disease and to identify cohorts of individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer to study survivorship in this population. In addition, there is a need to use innovative methods to capture and monitor symptoms in existing data sources such as registries and EHRs and to obtain data on treatment changes and subsequent outcomes. Further, treatment trials that collect detailed treatment and adverse event information could potentially be leveraged for longer-term follow-up (observational epidemiology) studies of survivorship needs and outcomes in populations of individuals diagnosed with advanced or metastatic cancer. Finally, existing data resources (eg, large cancer survivor cohort studies) should be examined, where possible, to identify factors associated with outcomes in individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer.

Symptom Management

Evidence Gaps. Advances in novel therapies, including immunotherapies and targeted therapies, have contributed to a growing population of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers. However, these newer treatment approaches may be associated with burdensome and long-lasting immune-related adverse side effects, including endocrine disorders and arthritis or althralgias (12,13). Subject matter experts noted that there is a need to identify both prevalent and emerging symptoms experienced by individuals based on treatment type, cancer type, and other relevant factors. Given that individuals are living longer, panelists indicated a critical need to understand symptom trajectories over time, as well as mechanisms underlying symptoms. Although symptom assessment and management have been recognized as important for those with advanced cancer (14), understanding symptom patterns will inform the development of effective tailored interventions. Speakers and discussants noted that there are also few nonpharmacological symptom management interventions focused specifically on individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers. Further, there was no clear evidence identified in the meeting to determine whether existing symptom management interventions developed for cancer survivors with early-stage disease would be effective for advanced and metastatic cancer survivors. Such information is needed for the development of care pathways and practice guidelines.

Subject matter experts also indicated the need for ubiquitous, integrated palliative care for individuals being treated for advanced or metastatic disease. Although there has been research demonstrating the impact of early palliative care (15,16), palliative care and end-of-life or hospice care continue to be conflated, and often survivors living with advanced or metastatic cancer are not receiving appropriate palliative care while on treatment. Further, there is a need to understand the optimal delivery, timing, and components of palliative care for individuals living with advanced and metastatic disease. Finally, session participants noted a need to understand the optimal role of caregivers who support the management of symptoms, along with any associated burden or distress experienced by caregivers themselves.

Key Opportunities. A critical first step to reducing symptom burden for individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer is to identify survivors who have the greatest need for symptom management strategies. Thus, appropriately powered studies that assess and track symptoms in individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer, including the type, duration, and frequency, could inform interventions and substantially improve quality of life. Further, there is a need to identify factors that contribute to symptom burden among those with advanced or metastatic cancer, including cancer type, treatments received, and ability to self-manage. In addition, there may be opportunities to leverage existing data resources and clinical trial networks to increase our understanding of symptom trajectories and mechanisms. There is also a need for research to identify key components of symptom management interventions in survivors with early-stage cancer that can be adapted or tailored for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers.

Psychosocial Research

Evidence Gaps. Individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancer and their caregivers have unique psychosocial needs that are poorly described in the extant literature. Subject matter experts emphasized that, given the changing trajectory and transitions in goals of care for these individuals, there is a lack of information on the psychosocial impact for individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer and their caregivers. In addition, although these survivors may be living longer than they once were, uncertainty about their prognosis can contribute to psychological distress. For example, survivors living with advanced or metastatic cancer receive numerous scans to monitor their response to treatment and as part of routine follow-up care, which can trigger feelings of apprehension, anxiety, and distress (termed scanxiety). Additionally, caregivers for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers are increasingly providing home medical management and support for longer periods of time, often resulting in unmet needs and high levels of burden. Caregivers must also manage the changing trajectory and prognosis of their loved one.

Panelists discussed the importance of prognostic uncertainty and the fact that current work in this area is hampered by provider ability to offer an accurate prognosis. Although there are existing tools to measure prognosis in advanced cancer patients, it can be difficult to implement these tools in clinical practice (17). Further, studies to understand how providers communicate prognostic information and the factors that influence prognostic communication and understanding are needed. For example, how clinicians’ unconscious biases about disease severity may impact disclosure, documentation, and communication of prognosis is not well understood. Additionally, understanding how newer cancer treatments (eg, targeted therapy and immunotherapy) influence prognostic communication and decision making for both patients and providers merit study in this population. Overall, proactive, integrated, and survivor and caregiver-centric care is needed to address psychosocial well-being, symptom and comorbidity management, and quality of life at the point of diagnosis, particularly given the changing care trajectory for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers.

Key Opportunities. To address the psychosocial needs of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers and their caregivers, qualitative and quantitative studies are needed to describe their unique psychosocial experiences (eg, depression, anxiety, uncertainty, fear of death), especially in the context of receipt of newer cancer therapies. Existing epidemiologic cancer survivor cohorts may also be leveraged to elucidate how the psychosocial needs of individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer change over time and may be influenced by changes in prognosis. In addition, innovative interventions and models of care, such as telepsychiatry and mobile health, should be explored to improve access to psychosocial services in historically underrepresented and underserved communities and address the needs of caregivers. Finally, there is a need to develop and evaluate interventions to improve coping and address both existential and psychosocial needs of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers and their caregivers.

Health-care Delivery

Evidence Gaps. Follow-up care for cancer survivors requires comprehensive approaches including prevention and surveillance of recurrence and subsequent malignancies, surveillance and management of physical and psychosocial effects of cancer and its treatment, and health promotion (18). Previous research among survivors of early-stage cancers has focused on evaluating models of care delivery, measuring the quality of care, and promoting transitions in care. Subject matter experts emphasized how survivorship care for individuals with early-stage disease differed from survivorship care for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancer. Given the changing trajectory of care (ie, cycling on and off therapy, with and without evidence of disease, and between chronic and acute, episodic care), the fact that these individuals are living longer with their disease, and the impact of other comorbid conditions, it is not clear who is, or should be, part of the multidisciplinary team for individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer. This situation is further complicated by a lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities between various providers (eg, specialty vs primary care, non-oncology specialists, palliative care, social work, and other supportive care resources), and issues with communication and care coordination. In addition, there may be differences in care based on provider type and care delivery settings (eg, oncology vs primary care, academic medical centers and NCI-designated cancer centers vs community oncology practices and centers). Panelists noted that research is needed to determine optimal models that can be tailored based on the needs of the survivor and caregiver, the preferences (and availability) of specific providers and specialists, and health system resources. Experts also noted gaps in provider knowledge regarding the long-term impact of living with advanced and metastatic cancers, as well as uncertainties about how to approach comorbidity management for these individuals. Overall, these circumstances can contribute to challenges in care coordination between survivor and provider, and among providers, ultimately placing great burden on survivors to self-manage their complex care needs. Finally, there is a need to understand and intervene on financial hardship for individuals living long-term with cancer, given that the needs may be different based on changing care trajectories, and there are often high out-of-pocket expenses for individuals treated with newer therapies.

Key Opportunities. Several opportunities in the area of health-care delivery were identified. There is a need to understand the care patterns and health-care utilization for individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers. This research may involve novel approaches to leveraging existing datasets and the development of new data resources. Given the critical and essential role that caregivers of individuals with advanced and metastatic cancer play in delivering care, it is also necessary to develop and test optimal care models tailored for this population. Caregiver-focused interventions for these populations should focus on co-symptom management and relationship and sexual health and account for a longer intervention duration to address transitions from diagnosis to treatment to periods of disease stability to end-of-life care. In addition, it is important to understand the experiences and implications of financial hardship among survivors and caregivers and how the impact is magnified for those diagnosed with or dealing with a progression to advanced or metastatic disease. Overall, there is a critical need to develop tailored, innovative, and proactive models of care, including the delivery of supportive and palliative care, financial navigation, and related services, as well as comprehensive follow-up care. To best inform tailored care delivery models, it is necessary to prioritize subgroups based on need, including factors such as current and past therapies, disease trajectory, and complexity of care (including timing, type of providers, and comorbidities), and to address transitions in care. Finally, any research focused on improving health-care delivery for this population must acknowledge the myriad demographic and clinical characteristics that compound existing disparities in access to care and outcomes (19).

Health Behaviors

Evidence Gaps. Despite the knowledge that practicing certain healthy behaviors (including physical activity, maintaining optimal weight, and avoiding excess alcohol and tobacco use) may improve quality of life and/or be associated with survival among individuals diagnosed with early-stage cancer (20-25), panelists noted that it is not clear whether individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer receive the same benefits from these healthy behaviors. In this session, the scientific presentations focused on 3 health behaviors known to be understudied in this population: physical activity, alcohol use, and sleep. Diet and nutrition were also discussed in the small group discussion following the presentations. Experts noted the paucity of data on health behaviors in individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer. They also noted a lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of existing recommendations for healthy behaviors such as physical exercise, alcohol use, weight management, and sleep for individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer (26,27). Several questions emerged during the session, including the following: 1) What, if any, modifications to existing health behavior guidelines (eg, Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, US Department of Agriculture recommendations for alcohol use and other dietary components or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sleep guidance) are required to improve survivorship outcomes (eg, quality of life) for individuals with advanced or metastatic cancer? 2) What is the efficacy of interventions to change and maintain health behaviors in these populations? 3) Do intervention outcomes differ in efficacy and feasibility based on type of setting (ie, within or outside a clinical setting)? The literature is robust with intervention approaches, models, and frameworks for health behaviors in other survivor populations (28,29); however, experts identified gaps in evidence as to whether these can be extended to individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer and the need for data to inform the best environments to support positive behavior adoption.

Key Opportunities. Although the discussion focused on physical activity, alcohol use, and sleep, it is recognized that additional research is needed for other health behaviors not focused on in this meeting (eg, tobacco cessation, diet, and nutrition). Overall, key next steps identified include the need to catalogue existing resources that have available health behavior data on individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer (eg, cancer survivor cohorts, EHR and claims data, and national surveys) or could be leveraged to collect such information. These types of resources could be used to better understand the prevalence of positive health behaviors and effects on outcomes (eg, quality of life, physical and emotional functioning) in this population of cancer survivors. It is also important to develop new resources that explore innovative methods to capture health behaviors in clinical research studies, such as wearable technologies. Finally, a key opportunity is to assess provider practices and preferences on health behavior discussions with individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer to inform clinical guidelines. The overall goal would be to determine the optimal type, amount, and frequency of positive health behaviors necessary to maintain or improve health outcomes for these populations; determine their acceptability and feasibility for patients; and determine how health-care providers and health systems can support healthy behaviors throughout the care trajectory.

Cross-Cutting Issues

Several areas of synergy emerged in the meeting and subsequent discussions. First, to inform research across all 5 scientific areas discussed in the NCI meeting, there is a need to conduct environmental scans to identify existing research resources, including databases and ongoing research studies, that can be used to investigate research questions pertaining to advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship. However, resources with data reflecting the long-term survivorship trajectory in advanced and metastatic cancer survivor populations are rare. Thus, there is also a need for prospective studies to examine changes in treatment patterns, health-care utilization, and health behaviors, as well as physiological and psychosocial outcomes, and factors associated with these outcomes. Information collected in such studies is critical for identifying survivors at risk for high symptom burden or other adverse outcomes and is necessary for the development and testing of targeted interventions and care pathways.

A second theme that arose in each scientific area was the importance of including the survivor perspective in all phases of research on individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancer. Although this is true for all survivorship research, the unique perspectives of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers are essential, especially given the changing landscape of care for these populations. Engaging survivors in a systematic and deliberate manner is critical to ensure that the issues and experiences most important to them are accurately reflected in priority setting for future research efforts. In addition, subject matter experts emphasized a need to understand and address existing health disparities among those living with advanced or metastatic cancer by including understudied, historically underrepresented and underserved, and vulnerable populations in studies pertaining to advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship, as well as collect detailed and comprehensive data on social determinants of health.

Finally, it is widely recognized that caregivers should be included in cancer survivorship studies. Several discussions centered around the paucity of studies focused on the unmet supportive care needs and supportive interventions for caregivers of individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer and the need for such studies given that these caregivers are often expected to provide substantial care and may have high levels of burden. Specific research gaps include strategies to understand these needs and optimally support the caregiver and survivor dyad through treatment decision making and with the uncertainty and financial hardship that may result from living with advanced or metastatic cancer.

Summary

Over the last decade, advances in treatment, including newer immunotherapies and targeted therapies, have led to longer survival times for individuals diagnosed with advanced or metastatic cancer (4,5). However, little research has been conducted to identify their survivorship needs or develop effective ways to address those needs (6,10). NCI’s recent meeting convened stakeholders, including researchers, clinicians, survivors, and advocates, to discuss gaps in scientific knowledge and opportunities for research to improve the evidence base. Information from this meeting led to the identification of key opportunities for research in 5 scientific areas pertaining to advanced and metastatic cancer survivorship (Box 1).

Box 1.

Research opportunities for addressing survivorship needs among individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer

Epidemiology and surveillance

|

Symptom management research

|

Psychosocial research

|

Health-care delivery research

|

Health behaviors research

|

Cross-cutting issues

|

Identifying existing resources for conducting research is key to accelerating the generation of knowledge about this population. Several existing resources were mentioned over the course of the meeting, including the NCI’s Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Clinical Trials Network, NCI Community Oncology Research Program, and large ongoing NCI-funded cancer survivor epidemiology cohorts (https://cedcd.nci.nih.gov). These resources, along with others not yet identified, may be useful in conducting much-needed survivorship research among individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer. Additionally, NIH has a variety of funding opportunities that could be used to address the evidence gaps and next steps identified (30). Finally, many foundations and advocacy organizations also provide resources, research funding, and other support for the advancement of knowledge pertaining to specific metastatic cancer populations.

To best address the needs of individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancer and to deliver comprehensive evidence-based quality care, research is urgently needed to fill evidence gaps while incorporating the survivor perspective. Developing an evidence base for individuals living with advanced or metastatic cancer is critical to inform policy and practice. Overall, survivorship research on individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers has the potential to have high impact on the health and well-being of this important and understudied population of survivors.

Funding

No funding received.

Notes

Role of the funder: Not applicable.

Disclosures: No conflicts or disclosures exist.

Author contributions: MAM, LG: Conceptualization, Writing-original draft preparation, reviewing and editing; AWS, ET, KC, KKF, JG, FP, PG, PBJ, AM, GT: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge all subject matter experts, survivors, and attendees from this meeting.

Disclaimers: The article was prepared as part of the authors’ (MAM, ET, KC, KKF, JG, FP, AWS, PG, PBJ, AM, GT, LG) official duties as employees of the US federal government. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute.

Data Availability

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

Contributor Information

Michelle A Mollica, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Ashley Wilder Smith, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Emily Tonorezos, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kathleen Castro, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Kelly K Filipski, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Jennifer Guida, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Frank Perna, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Paige Green, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Paul B Jacobsen, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Angela Mariotto, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Gina Tesauro, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Lisa Gallicchio, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Survivorship; 2020. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs. Accessed October 7, 2020.

- 2. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto A, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singer A, Goebel J, Kim Y, et al. Populations and interventions for palliative and end-of-life care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(9):995–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):640–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mariotto AB, Etzioni R, Hurlbert M, Penberthy L, Mayer MJCE, Biomarkers P. Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(6):809–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang T, Molassiotis A, Man Chung B, Tan J. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moghaddam N, Coxon H, Nabarro S, Hardy B, Xox K. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3609–3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Coping and prognostic awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2551–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rowland J, Gallicchio L, Mollica M, Saiontz N, Falisi A, Tesauro G. Survivorship science at the NIH: lessons learned from grants funded in fiscal year 2016. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mollica MA, Tesauro G, Tonorezos ES, Jacobsen PB, Smith AW, Gallicchio L. Current state of funded National Institutes of Health grants focused on individuals living with advanced and metastatic cancers: a portfolio analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(3):370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute. Virtual Meeting on Survivorship Needs for Individuals Living with Advanced and Metastatic Cancers; 2021. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/metastatic-survivorship-meeting. Accessed May 24, 2021.

- 12. Kennedy LB, Salama A. A review of cancer immunotherapy toxicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(2):86–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patrinely JR, Johnson R, Lawless AR, et al. Chronic immune-related adverse events following adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy for high-risk resected melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(5):744–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henson LA, Maddocks M, Evans C, Davidson M, Hicks S, Higginson I. Palliative care and the management of common distressing symptoms in advanced cancer: pain, breathlessness, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrell B, Temel J, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2016;35(1):96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greer JA, Jackson VA, Meier DE, Temel J. Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(5):349–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simmons CP, McMillan DC, McWilliams K, et al. Prognostic tools in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):962–970. e910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacobsen PB, de Moor J, Doria-Rose VP, et al. The National Cancer Institute’s role in advancing health-care delivery research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(1):20–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanna N, Mulshine J, Wollins DS, Tyne C, Dresler C. Tobacco cessation and control a decade later: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3147–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boyd P, Lowry M, Morris KL, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors and population controls from the National Health Interview Survey (2005-2015). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(5):pkaa043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. LoConte NK, Brewster AM, Kaur JS, Merrill JK, Alberg A. Alcohol and cancer: a statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palesh O, Aldridge-Gerry A, Zeitzer JM, et al. Actigraphy-measured sleep disruption as a predictor of survival among women with advanced breast cancer. 2014;37(5):837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott JM, Zabor EC, Schwitzer E, et al. Efficacy of exercise therapy on cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2297–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2375–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Washington (DC: ); USDA and US DHHS; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmitz KH, Campbell AM, Stuiver MM, et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):468–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheeran P, Jones K, Avishai A, et al. What works in smoking cessation interventions for cancer survivors? Health Psychol. 2019;38(10):855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Survivorship. Funding and grants; 2021. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/funding. Accessed May 25, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.