Abstract

This quality improvement study assesses the success of medical assistant–supported virtual rooming for physician video visits among patients in Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

COVID-19 pandemic–related increases in physician video visit availability have created new opportunities but may engender inequities. Patients who have lower socioeconomic status (SES), low English proficiency, or are African American or Black or Latino are less likely to use video visits successfully.1,2,3 Limited information exists to guide systems on bridging this “digital divide.” Medical assistant (MA)-supported virtual rooming has been suggested to facilitate patient access4,5 but to our knowledge has not been systematically evaluated.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study evaluated factors associated with successful video visit connections in Kaiser Permanente Northern California, an integrated system with 4.5 million members served by The Permanente Medical Group. Medical assistants conduct virtual rooming by telephoning patients before visits to facilitate connecting and administer rooming procedures.

We analyzed video visits to adult and family medicine physicians from October 1 through October 31, 2020, retaining each patient’s first video visit during this period. The MA virtual rooming rate for each of the 61 medical offices was the percentage of scheduled video visits with an MA involved; to avoid circularity, this was calculated for September 2020. We evaluated correlates of successful connection via Poisson regression models using generalized estimating equations.

A research determination official for Kaiser Permanente Northern California determined that this project did not meet the regulatory definition of research involving human participants per the Common Rule (45 CFR §46). Analyses were conducted in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

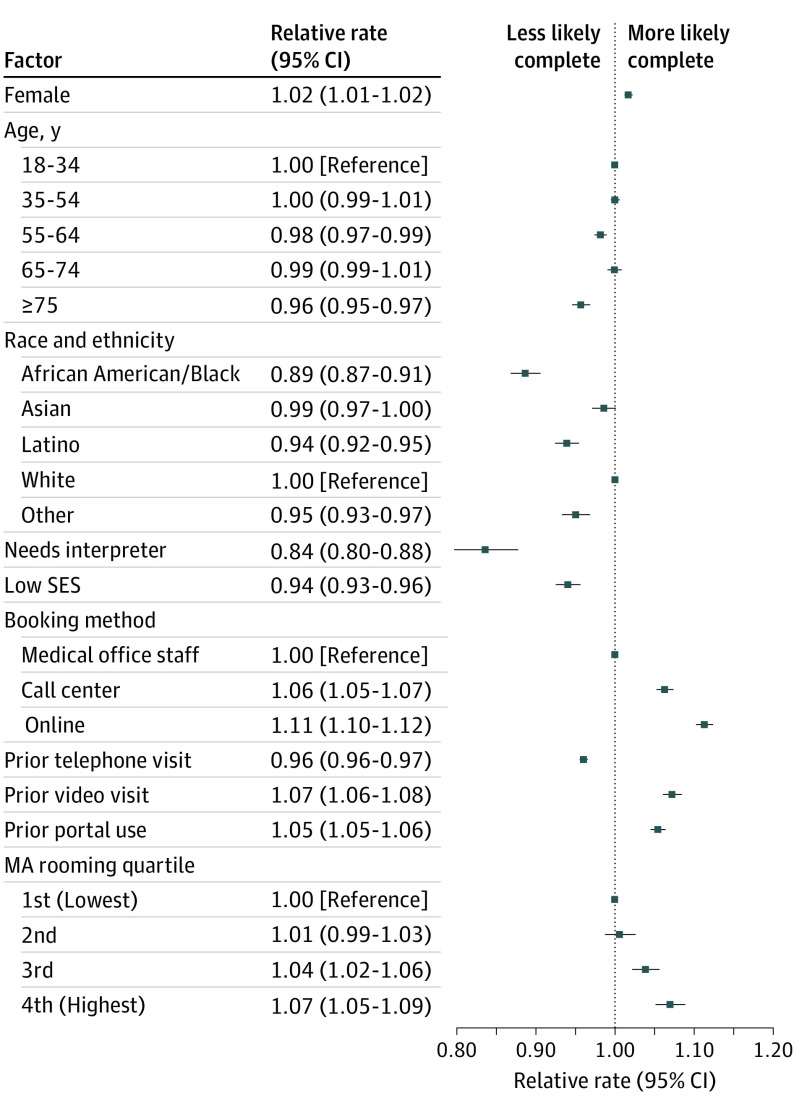

Of the 136 699 video visits studied, 114 214 (83.6%) had successful connections. Of patients making these visits, 14.2% had low neighborhood SES, 3.6% needed interpreters, 20.1% were Latino, and 7.9% were African American or Black. African American or Black race (relative rate [RR], 0.89; 95% CI, 0.87-0.91), Latino ethnicity (RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.92-0.95), needing an interpreter (RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88), and living in a low SES neighborhood (RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.93-0.96) were associated with a lower likelihood of connecting (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Factors Associated With Successful Connection of Scheduled Video Visits at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, October 2020.

A successful connection was defined as both the patient and physician connecting for 1 minute or longer. Low neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) was defined by patient residential US Census tract with 20% or more households in poverty or 25% or more residents without a high school education. The final multivariable model also included comorbidity burden (high comorbidity burden: relative rate [RR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93-0.96; moderate comorbidity burden: RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-1.00; low comorbidity burden: reference), imputed comorbidity burden (RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.79-0.88), Medicaid insurance (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.91-0.95), and any patient portal access by a proxy in the prior year (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03). The unadjusted RRs, taking into account clustering of patients by physician, were 1.02 (95% CI, 1.00-1.03), 1.07 (95% CI, 1.05-1.08), and 1.10 (95% CI, 1.08-1.12) in the second through fourth quartiles for medical assistant (MA) rooming, respectively.

Medical office MA virtual rooming rates varied, with ranges in the first through fourth quartiles of 4.6% to 30.9%, 35.9% to 50.6%, 52.4% to 72.0%, and 72.3% to 97.2%, respectively. Unadjusted rates of successful connection in these quartiles were 79.8%, 81.2%, 85.7%, and 88.1%, respectively. The MA virtual rooming rates were not statistically significantly associated with medical office–level measures of SES or interpreter need.

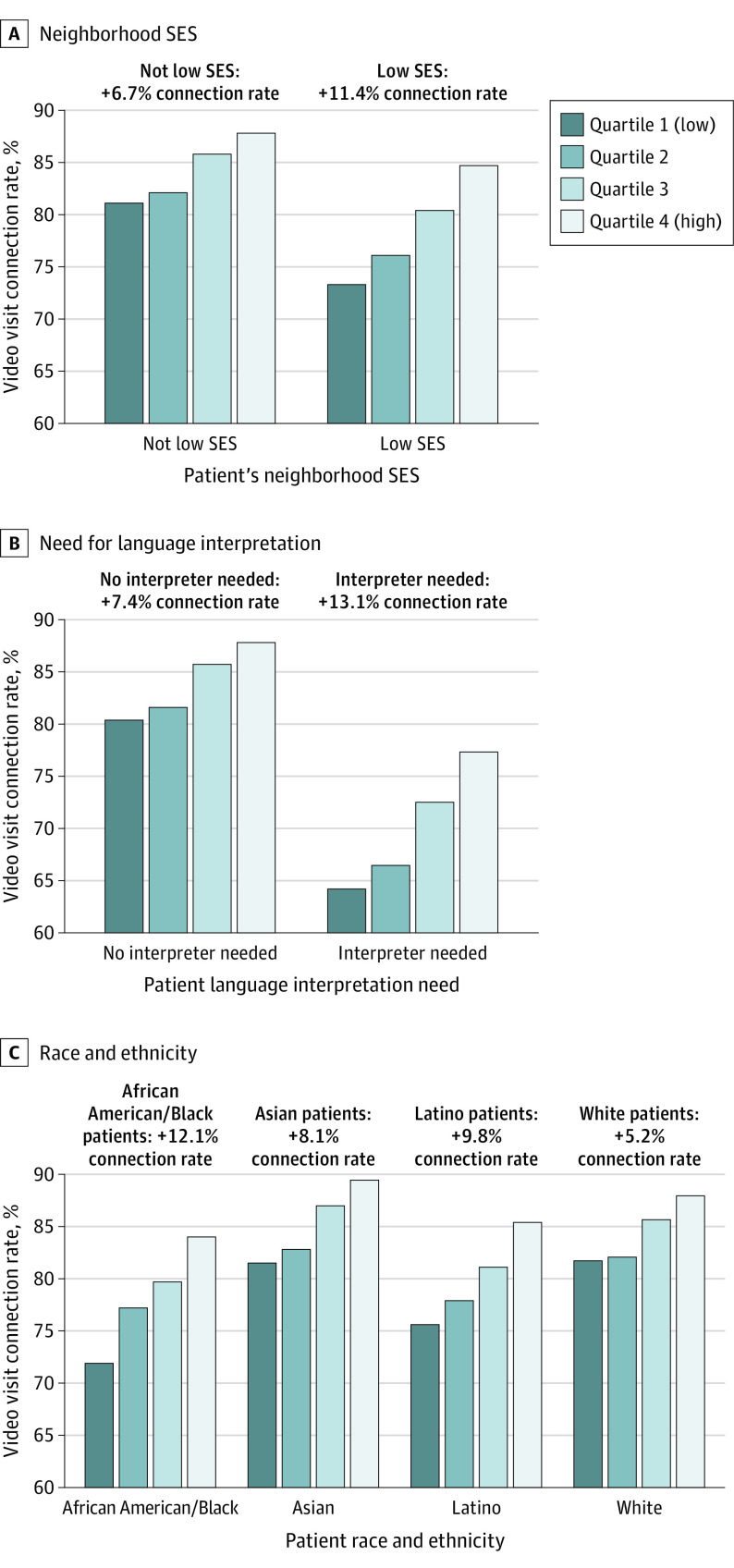

After adjustment, patients of medical offices with high MA virtual rooming rates were more likely to connect (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.05-1.09) (Figure 1). Medical assistant virtual rooming was associated with higher increases in connection rates among groups with the lowest connection rates in interaction term analyses (Figure 2). Between the lowest and highest quartiles for MA rooming, connection rates increased by 11.4% for patients in low SES neighborhoods vs 6.7% for others. High MA rooming rates were associated with higher connection rate increases for African American or Black (12.1%) or Latino (9.8%) patients compared with Asian (8.1%) or White (5.2%) patients. For patients needing interpreters, the predicted connection rate increase associated with high MA rooming was 13.1% compared with 7.4% for others.

Figure 2. Association of Medical Assistant Virtual Rooming With Predicted Video Visit Connection Rates by Risk Groups at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, October 2020.

Predicted percentages are based on interaction terms between medical assistant rooming quartile and patient characteristics from final multivariable models, including patient demographics and experience variables. Estimates were generated using the least-square means procedure. The unadjusted video visit connection rate estimates from this model, taking into account clustering of patients by physician, were 80.0%, 81.2%, 85.2%, and 87.7% in the first through fourth quartiles for medical office medical assistant virtual rooming rates, respectively. Rates of medical assistant virtual rooming for video encounters at 61 medical offices during September 2020 were 4.6% to 30.9%, 35.9% to 50.6%, 52.4% to 72.0%, and 72.3% to 97.2% in the first through fourth quartiles, respectively. SES indicates socioeconomic status.

Discussion

Medical assistant–supported virtual rooming was associated with successful video visit connections in this diverse population. High MA rooming rates were associated with larger connection improvements for patients at higher risk of not connecting, including those with lower SES, of Latino ethnicity or African American or Black race, or needing interpreters.

This observational design cannot exclude unmeasured confounding by other factors (eg, other effective practices) as potentially explaining these associations. However, MA virtual rooming rates were not associated with medical office–level population SES. The variation observed in MA virtual rooming rates aligns with anecdotal reports that implementation can be variable owing to multiple factors.

These findings suggest that medical office practices may play a role in facilitating video visits for patients at risk of inequitable access to care. Medical assistant–supported virtual rooming merits further testing as a possible means of narrowing the digital divide.

References

- 1.Crotty BH, Hyun N, Polovneff A, et al. Analysis of clinician and patient factors and completion of telemedicine appointments using video. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2132917. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsueh L, Huang J, Millman AK, et al. Disparities in use of video telemedicine among patients with limited English proficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2133129. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205873. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan M, Asch S, Vilendrer S, et al. Qualitative assessment of rapid system transformation to primary care video visits at an academic medical center. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):527-535. doi: 10.7326/M20-1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan M, Phadke AJ, Zulman D, et al. Enhancing patient engagement during virtual care: a conceptual model and rapid implementation at an academic medical center. NEJM Catalyst . July 10, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0262