Abstract

The resistance profiles, for 15 antimicrobial agents, of 333 Salmonella strains representing the most frequent nontyphoidal serotypes, isolated between 1989 and 1998 in a Spanish region, and 9 reference strains were analyzed. All strains were susceptible to amikacin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and imipenem, and 31% were susceptible to all antimicrobials tested. The most frequent types of resistance were to sulfadiazine, tetracycline, streptomycin, spectinomycin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol (ranging from 46 to 22%); 13% were resistant to these six drugs. This multidrug resistance pattern was found alone or together with other resistance types within serotypes Typhimurium (45%), Panama (23%), and Virchow (4%). Each isolate was also screened for the presence of class 1 integrons and selected resistance genes therein; seven variable regions which carried one (aadA1a, aadA2, or pse-1) or two (dfrA14-aadA1a, dfrA1-aadA1a, oxa1-aadA1a, or sat1-aadA1a) resistance genes were found in integrons.

The worldwide use of antimicrobials in different fields, such as human and veterinary medicine and agriculture, and as food animal growth-promoting agents during the past decades has created enormous pressure for the selection of antimicrobial resistance among bacterial pathogens. Nowadays, there is increasing concern about the development of multiresistance in bacteria causing zoonosis and having an important animal reservoir, such as Salmonella strains (5, 6, 9); this multiresistance is of considerable importance in both human and veterinary medicine and is the subject of several surveillance programs (6, 9).

An efficient route of acquisition and vertical and horizontal dissemination of resistance determinants is through mobile elements including plasmids, transposons, and gene cassettes in integrons (5, 14, 15, 18, 22). Four distinct classes of integrons encoding different integrases have been reported (13, 18), and class 1 integrons are the most frequent in clinical strains, being found in many different organisms. Class 1 integrons often contain sul1, which encodes resistance to sulfonamides (14, 16, 20). At the present time, about 60 different cassettes associated with resistance genes have been identified, and the same cassettes can be found in different classes of integrons (7, 16).

The aims of the present work were to (i) trace the frequencies and major changes throughout the last decade in susceptibility patterns of Salmonella enterica organisms representing the most frequent nontyphoidal serotypes causing human salmonellosis in the Principality of Asturias, Spain; (ii) ascertain the presence and spread of class 1 integrons among nontyphoidal serotypes; and (iii) characterize the different variable regions of the class 1 integrons found in order to identify the resistance genes located therein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The study included 333 apparently epidemiologically unrelated nontyphoidal Salmonella strains collected in the Principality of Asturias, Spain, from 1989 to 1998 (Table 1), and 9 reference strains belonging to different serotypes: Enteritidis PHLS 2187-PT4, PHLS 2408-PT6a, PHLS 2468-PT8, and PHLS-PT13a (Public Health Laboratory Service, London, England) and ATCC 13076-PT1 (American Type Culture Collection); Typhimurium ATCC 14028-DT133 and LT2-DT104 and BC-25268-DT195 (Bayer AG Pharma-Research Center Collection, Wuppertal, Germany); and Virchow CECT 4154 (Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo, Valencia, Spain). Of the Asturian strains, 296 (representing about 10% of clinical isolates registered in the Laboratorio de Salud Pública [LSP] of the Principality of Asturias over the period under study) were associated with sporadic human salmonellosis episodes registered at different times and/or hospitals, implicated in both intra- and extraintestinal processes, and isolated from feces (246 strains), blood (33 strains), urine (9 strains), and other samples (8 strains); a further 19 strains (collected from feces and/or food) were associated with 19 different outbreaks; 7 strains were collected from food not associated with outbreaks; and 11 strains were from environmental sewage samples. These 342 strains belonged to 4 serogroups (B, C, D, and G) and 18 serotypes (Table 1). Serotyping of strains and phage typing of Typhimurium strains (1) have been carried out in the LSP and the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (CNM), Madrid, Spain.

TABLE 1.

Frequency of antimicrobial resistance in different Salmonella serotypes

| Serotype | No. of strains tested | % Resistance within serotype to antimicrobial agenta:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | CEF | CHL | GEN | KAN | NAL | STR | SPT | SUL | SXT | TET | ||

| Typhimurium | 83 | 77 | 8 | 64 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 69 | 54 | 93 | 31 | 89 |

| Enteritidis | 64 | 28 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 16 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 17 |

| Virchow | 49 | 25 | 6 | 16 | 6 | 12 | 20 | 24 | 20 | 39 | 10 | 24 |

| Hadar | 33 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 21 | 48 | 30 | 21 | 3 | 33 |

| Ohio | 32 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 38 | 34 | 47 | 19 | 31 |

| Panama | 30 | 23 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 30 | 77 | 37 | 33 | 43 | 33 | 43 |

| Muenchen | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Otherb | 35 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 20 | 14 | 43 | 14 | 23 |

| Total | 342 | 34 | 3 | 22 | 5 | 7 | 18 | 37 | 27 | 46 | 16 | 42 |

Drugs and disk loads were as follows: ampicillin (AMP), 10 μg; cephalothin (CEF), 30 μg; chloramphenicol (CHL), 30 μg; gentamicin (GEN), 10 μg; kanamycin (KAN), 30 μg; nalidixic acid (NAL), 30 μg; streptomycin (STR), 10 μg; spectinomycin (SPT), 10 μg; sulfadiazine (SUL), 300 μg; trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), 1.25 and 23.75 μg, respectively; and tetracycline (TET), 30 μg. Also tested were amikacin (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), and imipenem (10 μg), all strains being susceptible.

Other serotypes include Infantis (seven strains), Bredeney (six strains), Brandenburg (five strains), Derby (five strains), Newport (three strains), Worthington (three strains), Grumpensis (two strains), Agona (one strain), Havana (one strain), Ndolo (one strain), and Poona (one strain).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Salmonella strains were tested for their susceptibility to 15 antimicrobial agents (Table 1) by the disk diffusion assay according to a standard procedure (17). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant strains carrying an integron which generated a 1,600-bp amplicon were also tested for their resistance to trimethoprim. Each strain was assigned to a resistance pattern. Strains presenting intermediate resistance values were considered resistant strains.

Detection of class 1 integrons by PCR.

All strains were tested more than once for the presence of class 1 integrons (first PCR step) using the primers 5′CS-3′CS (14). The assays were performed as described in reference 21 using a hot start cycle of 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2.5 min and a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min (conditions which allowed the detection of fragments of at least 2,500 bp). Amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels, and a 100-bp ladder (Gibco BRL, Life Science Technologies, Barcelona, Spain) was used as the molecular size marker. Those strains generating one or more amplicons were also tested for the presence of sul1 associated with the integrons by amplification of the sul1 gene using the primers sul1-F–sul1-B (20) and by amplification of the fragment including the variable region and the sul1 gene using the 5′CS–sul1-B primers (14, 20). The PCR conditions used were the same as cited above, but with annealing temperature and extension steps of 70°C and 1 min (for sul1) or 65°C and 3 min (for the 5′CS-sul1 fragment), respectively.

The integron profiles (IPs) were defined by the number and the size of the amplicons generated by a strain. One strain of each serotype representing each IP was considered the “type strain” (IP-I: Typhimurium LSP14/92; IP-II: Virchow LSP87/92, Typhimurium LSP122/92, Worthington LSP7/93, Agona LSP51/93, Enteritidis LSP497/98, Hadar LSP186/98, Panama LSP580/95, and Poona LSP238/96; IP-III: Panama LSP304/92, Ohio LSP131/96, Brandenburg LSP331/96, Typhimurium LSP15/89, and Virchow LSP410/92; IP-IV: Typhimurium LSP31/93; IP-V: Virchow LSP159/94).

DNA purification and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis.

PCR products generated in the first PCR step (direct amplification samples as well as agarose gel fragments) were purified with the GFX PCR DNA and gel band kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Barcelona, Spain).

The RFLP analysis of the different amplicons was carried out using several endonucleases: TaqI (T↓CGA) (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) and BglII (A↓GATCT), PvuI (CGAT↓CG), and HincII (GT[T/C]↓[A/G]AC) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). For this, aliquots of the amplicons obtained in the first PCR step were directly purified and digested separately with 5 U of each endonuclease, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The restriction products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels.

Detection of resistance genes in variable regions of integrons by PCR.

The amplicons ascribed to each IP were tested in a second PCR step for the presence of aadA [ant-(3")], pse-1, oxa1, and dfr (dhfr) genes. The primers used for the amplification of the two former genes were reported in reference 20; the oxa1 (5′AGCAGCGCCAGTGCATCA3′-5′ATTCGACCCCAAGTTTCC3′) and dfr (5′GTGAAACTATCACTAATGG3′-5′CCCTTTTGCCAGATTTGG3′) primers were designed for the present work from the gene sequences introduced in GenBank (accession no. AJ009819 and Z8331, respectively). As template DNA, 15 μl of a 10-fold water dilution of amplicons in the first PCR step was used. For the analysis of IP-I, each of the two amplicons (1,000 and 1,200 bp) was collected from the gel, purified, and tested separately. The PCR conditions used were the same as those cited above with 1 min for the extension steps and annealing temperatures of 55°C for dfr, 65°C for pse-1 and oxa1, and 70°C for aadA.

Sequencing of PCR products.

PCR products, representing the different amplicons generated by the 16 type strains, were collected from the gels, purified, and directly analyzed by partial sequencing. Sequencing reactions were carried out using a DRho terminator TAQ FS kit (Perkin-Elmer) in a GeneAmp PCR system as recommended by the manufacturer. Sequences were read in an ABI Prism 310A apparatus with a 47-cm- by 50-μm capillary which allowed the reading of about 450 bp per run. The primers 5′CS and 3′CS (14) were used for sequencing both ends of the different amplicons under study. In addition, for 1,600-, 2,000-, and 2,300-bp amplicons, internal primers were synthesized and used to continue the process until the resistance genes inserted in each amplicon were identified. Sequences obtained were compared to those registered in GenBank.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

The findings obtained in the antimicrobial susceptibility test (Table 1) showed the following results. (i) Thirty-one percent of the strains were susceptible to all antimicrobials tested, 18% presented a single type of resistance, and 51% were multiresistant (two to nine types of resistance). (ii) All strains were susceptible to amikacin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and imipenem; more than 90% were susceptible to cephalothin, gentamicin, and kanamycin. (iii) When the study period was divided into two (1989 to 1993 and 1994 to 1998), an increase in the number of Asturian strains resistant to nalidixic acid and trimethoprim was found. These resistances probably emerged at different times in different serotypes, the increase being statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05, χ2 test) in only some serotypes (i.e., nalidixic acid resistance in Virchow, Panama, Hadar, and Enteritidis and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance in Typhimurium). (iv) The drug-resistant strains were grouped into 82 resistance patterns, of which only 22 were represented by more than two strains. (v) Typhimurium stood out as the serotype with the highest percentages of resistant strains (96%), with 37 strains showing multiresistant phenotypes which included ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin-spectinomycin, sulfadiazine, and tetracycline resistance. Twenty of these strains belonged to phage type DT104, and a further 15 were non-phage typeable, a fact which could be related to some phage conversion phenomena (2, 8). All these strains could be considered members of an emergent clone or lineage which has become a major cause of illness in humans and animals in several European countries and in the United States (3, 4, 9, 15, 19, 20, 23). (vi) Multiresistant phenotypes including four or more types of resistance were also found in 10 other serotypes (33% of Asturian strains), being more frequent among Ohio (34%), Panama (33%), Brandenburg (20%), Virchow (16%), and Hadar (15%) strains.

Determination of class 1 integrons.

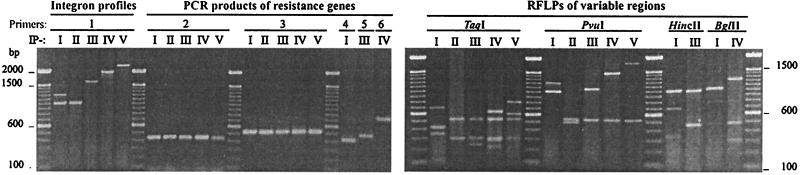

Class 1 integrons were present in 68 (20%) multiresistant strains (57 from clinical samples, 5 from pork, and 6 from sewage), none of them reference strains. Five IPs were defined, IP-I including two integrons and IP-II to IP-V including one integron each (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Some IPs appeared in a single serotype: IP-I (variable regions of about 1,000 and 1,200 bp) and IP-IV (variable regions of about 2,000 bp) in Typhimurium and IP-V (variable regions of about 2,300 bp) in Virchow. Other profiles appeared in several serotypes: IP-II (variable regions of about 1,000 bp) in Virchow, Typhimurium, Worthington, Agona, Enteritidis, Hadar, Panama, and Poona and IP-III (variable regions of about 1,600 bp) in Panama, Ohio, Brandenburg, Typhimurium, and Virchow. To determine the association between class 1 integrons and the sul1 gene, the strains of the different IPs were analyzed by PCR. With the sul1 primers, amplicons of the expected size (about 400 bp) were generated (Fig. 1). When the 16 type strains were analyzed with 5′CS–sul1-B primers, amplicons of about 1,900, 2,100, 2,500, 2,900, and 3,200 bp (representing the variable regions of 1,000, 1,200, 1,600, 2,000, and 2,300 bp, respectively) were generated (data not shown). These results indicated that the sul1 gene was located in all the integron types described in the present work.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of class 1 integrons from Salmonella. 1, PCR products generated with 5′CS-3′CS primers (14) used to define five IPs (IP-I to -V). 2 to 6; PCR products generated by specific primers for sul1, aadA, pse-1, dfrA, and oxa1, respectively, in each IP. The RFLPs were generated from amplicons representing each IP. A 100-bp ladder was used as the molecular size standard. Relationships between IPs, resistance genes, resistance patterns, and serotypes are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Relations between IPs, amplicon sizes, resistance genes, and resistance patterns found within Salmonella serotypes

| IP: amplicon size/resistance gene | Types of resistancea | Serotype (no. of strains) | Isolation period |

|---|---|---|---|

| I: 1,000-bp/aadA2; 1,200-bp/pse-1 | SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CHL-TET (NAL; CEF; SXT) | Typhimurium (30)bc | 1991–1998 |

| II: 1,000-bp/aadA1a | SUL-STR-SPT-CHL-SXT (AMP; CEF; GEN; KAN; TET) | Virchow (4) | 1992–1994 |

| SUL-STR-SPT-CHL-GEN (AMP; KAN; NAL; TET) | Typhimurium (2) | 1992–1998 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-CHL-KAN-SXT-TET | Worthington (2) | 1993 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-CHL-SXT-TET | Agona (1) | 1993 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-NAL-SXT-TET | Panama (1)c | 1995 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-GEN-TET | Poona (1) | 1996 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-GEN | Enteritidis (1) | 1998 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT | Hadar (1) | 1998 | |

| IIIa: 1,600-bp/dfrA14-aadA1a | SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CEF-CHL-KAN-SXT-TET | Typhimurium (1) | 1989 |

| IIIb: 1,600-bp/dfrA1-aadA1a | SUL-STR-SPT-KAN-SXT-TET (AMP; CEF; NAL) | Panama (9) | 1996–1998 |

| SUL-STR-SPT-SXT-TET (AMP; CHL; KAN) | Ohio (5) | 1996–1998 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CHL-KAN-SXT | Brandenburg (1) | 1996 | |

| SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CHL-SXT-TET | Virchow (1) | 1992 | |

| IV: 2,000-bp/oxa1-aadA1a | SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CHL-TET (GEN; SXT) | Typhimurium (5) | 1993–1998 |

| V: 2,300-bp/sat1-aadA1a | SUL-STR-SPT-AMP-CHL-KAN | Virchow (3) | 1992–1994 |

Additional types of resistance found in some but not all of the strains of the serotype are indicated by parentheses. Drug abbreviations are defined in Table 1, footnote a.

Food strains are also included.

Sewage strains are also included.

The RFLP analysis of variable regions representing the different IPs and serotypes was carried out using four endonucleases. TaqI digested all amplicon types; PvuI digested all except for the 1,000-bp amplicon of IP-I; HincII digested only the 1,200-bp amplicon of IP-I and the 1,600-bp amplicon of IP-III; and BglII digested only the 1,200-bp amplicon of IP-I and the 2,000-bp amplicon of IP-IV. It was observed that amplicons of about 1,000 bp from IP-I (generated with only Typhimurium strains) and IP-II (generated by strains of several serotypes, including Typhimurium) yielded different RFLPs (Fig. 1).

Relationships of class 1 integrons, resistance genes, and resistance patterns.

Analysis of the resistance profiles of the strains, the sizes of the amplicons, and the resistance genes in class 1 integrons reported for Salmonella (3, 4, 15, 19, 20, 24) suggested that aadA (encoding streptomycin-spectinomycin resistance), pse-1 and oxa1 (encoding ampicillin resistance), and dfrA (encoding trimethoprim resistance) genes could be present in some of the variable regions. The presence of these genes was tested by PCR using specific primers. The aadA primers generated a fragment of about 500 bp in the samples representing the five IPs (in the case of IP-I, only from the 1,000-bp amplicon) which included strains ascribed to 10 serotypes. The pse-1 and the oxa1 primers generated amplicons of about 400 and 700 bp in samples from IP-I (only from the 1,200-bp amplicon) and IP-IV, respectively, both represented by only serotype Typhimurium. The dfrA primers generated amplicons of about 450 bp in samples from IP-III, which included strains from five serotypes. Whereas ampicillin and trimethoprim are antimicrobials widely used in human medicine, streptomycin has been seldom used for over 2 decades in this field. Therefore, both the selection and dispersion of aadA genes in integrons could be related to the extensive use of this antibiotic in veterinary treatments and agriculture.

It is of note that the primers used for the detection of resistance genes (mainly for aadA and dfrA) could amplify different types of each gene. To confirm the presence of the suspected resistance genes, nucleotide sequencing of the PCR products from each type strain was carried out. When the 1,200- and 1,000-bp PCR product generated by the Typhimurium DT104 strain LSP14/92, which represented IP-I, were sequenced, it was found that the 1,200-bp region carried pse-1 (GenBank accession no. AF071555), whereas the 1,000-bp region carried aadA2 (accession no. AF071555). The presence of integrons with variable regions of 1,200 bp (pse-1) and 1,000 bp (aadA2) is very common among multiresistant DT104 Typhimurium strains, in which both integrons are chromosomally located (3, 4, 19, 20). Within the series analyzed in this study, 76% of the Typhimurium DT104 and 48% of the non-phage-typeable strains carried integrons with both resistance genes and were related to the multiresistance patterns described above and compiled in Table 2. In previous work carried out in our laboratory, most of these strains had been ascribed to ribotypes and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types which showed more than 90% similarity (10, 11).

The sequencing of the 1,000-bp variable regions of the integrons generated in the eight type strains representing IP-II showed the presence of aadA1a in all of them (accession no. AJ009820). It proved interesting that the two Typhimurium strains classified as IP-II belonged to phage type DT80. Variable regions of similar size and carrying aadA1a have been found in other enterobacteria (14, 16). The sequencing of the 1,600-bp PCR products generated by the five type strains classified as IP-III revealed the presence of two different resistance gene combinations (dfrA14-aadA1a and dfrA1-aadA1a), the profiles thus being considered IP-IIIa and IP-IIIb. The type strains of serotypes Ohio, Panama, Virchow, and Brandenburg carried dfrA1 (dhfrI, accession no. X17478) located near the 5′ conserved region (5′CR) and aadA1a near the 3′CR, whereas the type strain Typhimurium DT204 LSP15/89 carried dfrA14 (dhfrIb, accession no. Z50805) and aadA1a, located near the 5′CR and the 3′CR, respectively. Variable regions of similar sizes and carrying aadA1a and different dfr gene cassettes, including dfrA1, have been found in Escherichia, Klebsiella, and Serratia species (12, 14, 16). When the 2,000-bp variable region of the Typhimurium DT104 strain LSP31/93 which represented IP-IV was sequenced, the presence of oxa1 (accession no. AJ009819.1) located near the 5′CR and aadA1a near the 3′CR was confirmed. This variable region is similar to the one from In-t2 (2,100 bp) located in a 140-kb IncFI plasmid carried by other DT104 Typhimurium strains (24). The 2,300-bp variable region of the Virchow strain LSP159/94, which represented IP-V, carried two resistance genes: sat-1 (accession no. X56815), which encoded streptothricin resistance, near the 5′CR and aadA1a near the 3′CR.

In light of the results obtained for the frequency and spread of class 1 integrons among nontyphoidal Salmonella serotypes, the following findings can be noted. (i) Salmonella strains carrying class 1 integrons were collected throughout the entire study period, being more frequent in serotypes Typhimurium, Ohio, Panama, and Virchow. (ii) The spread of complete integron structures, assigned to IP-II and -III, has occurred among different Salmonella serotypes. (iii) Some serotype-specific integrons were found, such as those forming IP-I and -IV in Typhimurium, as has been previously reported (3, 4, 19, 20, 24), and IP-V in Virchow. (iv) aadA1a alone or in combination with other resistance genes in different variable regions of integrons was found in several Salmonella serotypes. In Salmonella and other enterobacterial species, single and fused aadA gene cassettes in integrons have been reported (12, 14, 16, 19, 24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. A. González-Hevia (LSP, Principado de Asturias, Spain), H.-P. Kroll (Bayer AG, Pharma-Research Center, Wuppertal, Germany) and M. A. Usera (CNM, Madrid, Spain) for Salmonella strains and A. Aladueńa (CNM) for phage typing of Typhimurium strains. We are also indebted to M. R. Rodicio for her critical revision of this paper.

This work was supported by grants from the “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria” (FIS 98/0296 and 00/1084), Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Spain. S. Soto is the recipient of a grant of “Formación de Personal Investigador” (Ref AP98), Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson E S, Ward L R, de Saxe M J, de Sa J D H. Bacteriophage typing designations of Salmonella typhimurium. J Hyg. 1977;78:297–300. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400056187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggesen D L, Skov M N, Brown D J, Bisgaard M. Separation of Salmonella Typhimurium DT2 and DT135: molecular characterization of isolates of avian origin. Eur J Epidemiol Infect Dis. 1997;13:347–352. doi: 10.1023/a:1007302205271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briggs C E, Fratamico P. Molecular characterization of an antibiotic resistance gene cluster of Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:846–849. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casin I, Breuil J, Brisabois A, Moury F, Grimont F, Collatz E. Multidrug-resistant human and animal Salmonella typhimurium isolates in France belong predominantly to a DT104 clone with the chromosome- and integron-encoded beta-lactamase pse-1. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1173–1182. doi: 10.1086/314733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies J. Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes. Science. 1994;264:375–382. doi: 10.1126/science.8153624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher I S T. The Enter-Net International surveillance network. How it works. Eurosurveillance. 1999;4:52–55. doi: 10.2807/esm.04.05.00073-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fluit A C, Schmitz F J. Class 1 integrons, gene cassettes, mobility, and epidemiology. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:761–770. doi: 10.1007/s100960050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost J A, Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Characterization of resistance plasmids and carried phages in an epidemic clone of multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium in India. J Hyg. 1982;88:193–204. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400070066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glynn M K, Boop C, Dewitt W, Dabney P, Moktar M, Angulo F. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra B, Landeras E, González-Hevia M A, Mendoza M C. A “three-way ribotyping scheme” for Salmonella typhimurium: usefulness for phylogenetic and epidemiological purposes. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:307–313. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-4-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerra B, Schroers P, Mendoza M C. Application of PFGE to an epidemiological and phylogenetic study of Salmonella serotype Typhimurium. Relationships between genetic types and phage types. New Microbiol. 2000;23:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones M E, Peters E, Weersink A M, Fluit A, Verhoef J. Widespread occurrence of integrons causing multiple antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Lancet. 1997;14:1742–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazama H, Kizu K, Iwasaki M, Hamashima H, Sasatsu M, Arai T. Isolation of a new integron that includes a streptomycin resistance gene from the R plasmid of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levèsque C, Pyche L, Larose C, Roy P H. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:185–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llanes C, Kirchgesner V, Plesiat P. Propagation of TEM- and PSE-type β-lactamases among amoxicillin-resistant Salmonella spp. isolated in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2430–2436. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez-Freijo P, Fluit A C, Schmitz F-J, Verhoev J, Jones M E. Many class 1 integrons comprise stable structures occurring in different species of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from widespread geographic regions in Europe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:686–689. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M2-A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recchia G D, Hall R M. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology. 1995;141:3015–3027. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley A, Threlfall J. Molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance genes in multiresistant epidemic Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandvang D, Aarestrup F M, Jensen L B. Characterization of integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in Danish multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;160:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soto S M, Guerra B, González-Hevia M A, Mendoza M C. Potential of a three-way randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis as a typing method for twelve Salmonella serotypes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4830–4836. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4830-4836.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokes H W, Hall R M. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene integration functions: integrons. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1669–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Threlfall E J, Frost J A, Ward L R, Rowe B. Epidemic in cattle and humans of Salmonella typhimurium DT104 with chromosomally-integrated multiple drug resistance. Vet Rec. 1994;134:577. doi: 10.1136/vr.134.22.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tosini F, Visca P, Dionisi A M, Pezzella C, Petruca A, Carattoli A. Class 1 integron-borne multiple antibiotic resistance carried by IncFI and IncL/M plasmids in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3053–3058. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]