Abstract

Physician's assistants (PA) are an integral part of hospital teams. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of a multidisciplinary hospital-wide communication skills training (CST) workshop on PAs. From November 2017 to November 2019, all participants in the CST workshop were sent a web-based retrospective pre-post survey to measure self-reported attitudes and behaviors related to communicating with patients, CST, and specific skills taught. PA responses were analyzed alone and were compared to non-PAs. Non-PAs were physicians and 1 nurse practitioner. In total, 258 PA and 333 non-PA participants were surveyed for an overall response rate of 25%. Among PAs, in 9 out of 10 domains measured, there was a significant change in self-reported attitudes and behaviors toward communicating with patients, CST, and skills taught (P < .05). Similar to other providers, PAs experienced positive changes in these self-reported attitudes and behaviors after CST, however, there were some significant differences found when comparing PAs and non-PAs in the covariate analysis.

Keywords: communication skills training, attitudes, behaviors, physician assistant, multidisciplinary, experience, hospital, health care

Introduction

Physician assistants (PA) are health care providers (HCP) with independent medical licenses who practice under the supervision of physicians. In the United States (US) they complete 26.5 months of training in an accredited program and pass a national certifying examination every 6 years. Communication skills are a core competency taught to PA and medical students in the US. PAs directly impact the patient experience as members of health care teams (1,2).

Communication skills training (CST) has been used as a path to improving patient and HCP experience. CST studies on HCPs generally have been on CST models such as the Four Habits model and Calgary–Cambridge models (3–6). The benefits of CST have been well documented and can be measured in many ways such as self-efficacy, attitudes, patient and HCP satisfaction, and reported use of skills (7–18). Positive changes in reported attitudes and behaviors relating to the use of communication skills may suggest both increased awareness of specific skills, the importance of these skills to the trainee, and increased ability or desire to use the skills in practice. Institutions are measuring the impact of CST to choose trainee groups and make financial decisions to support such programs.

Studies on the impact of CST on HCPs have often focused on specific medical specialties or practice locations, trainees, or lengthier full-day to months-long programs (19–25). Although PAs have been an integral part of medical teams and patient-facing care in many countries, they are an understudied group in regards to CST. To the best of our knowledge, the existing studies looking at hospital-wide CST have not included PAs, or have not looked at the effects of CST on PAs as a separate group compared to other HCPs.

Studies of CST and PAs have shown the importance of CST to PA practice. Self-perceived gaps in knowledge and need for more CST, communication skills as a way of preventing burnout, and perceived skill and difficulty of utilizing communication skills have been examined (26–28). Despite the importance of CST to PAs, larger multispecialty institution-wide studies have focused primarily on physicians, nurses, and other non-PA groups (3,17,29–31).

The few studies of PAs and CST have found positive outcomes, but they have been limited to students, specific settings, or the use of only 1 specific communication tool (26,32,33). One multispecialty, institution-wide study looking at the effect of CST on patient satisfaction included PAs, but PA responses were grouped with other non-MD HCPs in the analysis. This study did not find changes in patient satisfaction scores after CST but did find that CST lead to participants’ self-reported improvement in communicating with patients (34).

As many studies have shown HCPs to benefit from CST, differences among PAs and non-PAs were not expected in this study. When examining potential differences among HCPs, our decision to study PAs separately was informed by studies that showed that HCP types may experience the effects of CST in differing degrees. Two studies found larger positive effects among nurses after CST compared to other HCPs (3,35). These studies did not include PAs. Even studies of other advanced practitioners such as nurse practitioners (NP) were limited. The studies either analyzed all HCP data together, looked only at trainees, or focused on one specialty (32,36–39). Similar to PAs, NPs also noted self-perceived gaps in using communication skills (40). Because our institution's workshop originally was physician-only CST, we wanted to be certain that all groups experienced positive effects after CST in a mixed provider environment similar to the positive effects seen in the physician-only groups (30).

In 2014 our academic hospital system in New York City with over 6500 affiliated physicians, 830 PAs and over 2 million patient visits yearly launched the “Relationship-Centered Communication Workshop,” a 7.5-hr CST workshop for attending physicians. Initially, the workshops were given to attending physicians only and were voluntary. In August 2015 some departments chose to mandate attendance by all or some of their HCPs. In 2016, based on participant feedback, the workshop was shortened to 5-hrs. In 2017 PAs were actively recruited as participants. A prior study of this 7.5-hr workshop found that physicians had a statistically significant change in self-reported attitudes and behaviors relating to CST and communicating with patients in 9 out of 10 domains measured 6-weeks postworkshop (30).

The current study examines the effects of our CST workshop on practicing PAs’ self-reported attitudes and behaviors related to communicating with patients, CST, and the skills taught, 6-weeks postworkshop. Differences between PAs and non-PAs (physicians and 1 NP) were also examined to understand if the CST workshop was experienced differently by the 2 groups.

Methods

The CST workshops were taught in an academic hospital system in New York City. PAs in our study period were actively recruited into a 5-h CST workshop from 10 clinical departments with a majority mandated by their departments to attend. PA participants completed the workshop in mixed provider groups and received the same curriculum as previous physician-only groups. Formal informed consent was not obtained as the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB deemed protocol AAA06353 for the study exempt from review as it involved research using educational tests and survey procedures with de-identified information and thus not requiring formal informed consent procedures. Participants were verbally informed after each workshop that the surveys were voluntary, de-identified, and not linked to receiving continuing medical education credit.

The facilitators for the CST workshops were trained by the Academy of Communication in Healthcare (ACH) through a train-the-trainer program which included 12 physicians from a variety of medical and surgical specialties. The curriculum was developed together with ACH and contained similar structure and elements found in the Four Habits Model and Calgary-Cambridge models of CST (3–6). Didactic themes were related to establishing rapport, eliciting concerns, agenda setting, the use of empathy, shared decision-making, and difficult/challenging communication scenarios. The workshop combined evidence-based didactics with small group skills practice through role plays followed by direct feedback. The original 7.5-hr workshop was taught by 2 physicians, with no more than 12 participants per class, and was offered 3 to 5 times each month. When the workshop was shortened to 5-hrs, the number of participants per class was reduced to 8 and continued with 2 physician facilitators.

The length of the original workshop designed to be a full day workshop was affected by the larger number of participants requiring more time for role play. In the 5-hr format critical content and the interactive elements of evidence-based CST were preserved. To shorten the length of workshops, breaks were eliminated and smaller learner groups were created which required fewer rounds of skills practice through role play. Despite this decrease, all participants had the chance to participate in a role play and many of the workshops had less than 8 participants which allowed each individual extra skills practice. The surveys analyzed in this study are from the 5-hr program.

A retrospective pre-post survey study design was chosen to measure changes in self-reported attitudes and behaviors toward CST, communicating with patients, and the use of communication skills taught, 6-weeks after completing the workshop. In this design, the pre- and post- questions are administered at the same point in time.

The advantages of this method include the ease of administration, ease of de-identification as surveys do not need to be linked, and a decrease in response shift bias which can occur in traditional pre-post surveys. Response shift bias in traditional pre-post surveys, administered prior to the activity and then after the activity as 2 separate surveys, can lead to the underestimation of a program's effectiveness if participants overestimate their skill or knowledge prior to completing an educational activity (41–44). Overestimation of communication skills has been documented among physicians which were our initial study group and informed the decision to use the retrospective pre-post format (42,45). This might not be an issue with PAs, as studies have shown self-identified acknowledgment of gaps in communication skills (26,28).

Limitations of the retrospective pre-post survey include the accuracy of recall over time and the general bias associated with self-reporting relying solely on PA self-assessment. Other limitations of the retrospective survey include “reporting biases.” Two common limitations are social desirability bias, where participants may understate socially undesirable actions or overstate socially desirable skills such as expressing empathy, and effort justification bias which can occur where a participant may underestimate the retrospective pre-test skill to rationalize the effort of participating in a program (46). As most of the participants were mandated, effort justification could play a role in the overestimation of program effects.

The survey instrument used was designed in collaboration with ACH focusing on the skills taught in our CST workshop in order to assess the impact of our workshop on attitudes and use of communication skills among participants. The survey was initially created for internal assessment of the program within our institution. When deciding to initiate the study of our program we were unable to find a validated survey assessing the use of the specific skill sets that were being taught and decided to continue using our unvalidated survey recognizing this as a limitation. We also decided to use it for continuity in this study of PA participants as it had been used with a previous study of physician participants in our CST workshops (30).

A web-based survey link was sent by email 6-weeks after the workshop to each participant. In addition to demographic data, the de-identified survey had 10-questions with a 5-point Likert scale (“5-Almost Always/Always” to “1-Never/Rarely”) focusing on participants’ self-reported attitudes and behaviors toward CST, communicating with patients, and use of specific communication skills pre- and post-workshop. The other outcome measure was assessing a difference in responses between HCP type (PA vs Non-PA).

Responses from November 2017 to November 2019 were analyzed. Simple frequencies were used to analyze demographic data such as years in practice, time in direct patient care, primary practice location, provider type, prior CST experience, and if participation was mandated. A paired t-test was used to examine changes in PA participants’ responses in the retrospective pre-post survey (See Supplemental materials: Appendix A). Glass's delta was chosen to determine effect size as standard deviations varied in the pre- and post- groups (47,48). Linear regression was used to see effects of covariates on subjects’ responses. Demographic covariates in the analysis were added to linear regression models to adjust for differences between subjects and to estimate the changes observed while accounting for demographic differences. SPSS v26.0 was used for the analysis. All tests were conducted 2-sided to achieve a significance level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 591 HCPs completed the 5-hr CST workshop during the study period. Registration data showed that 43.7% were PAs from 10 medical and surgical specialties. Almost two-thirds of PA participants came from the department of internal medicine. A total of 148 responses were received for an overall response rate of 25% (148/591). The response rate for PAs was 21.7% (56/258) and non-PAs 27.6% (92/333). The non-PA respondents were 91 physicians and 1 NP.

Demographic variables were equally distributed between PAs and Non-PAs with the exception of PAs being more likely to be less than 10 years in practice (88% PAs vs 60% non-PAs) and working in an inpatient setting only (96% PAs vs 45% non-PAs). Similar percentages of PAs and Non-PAs had taken prior CST courses (22% PAs vs 26% non-PAs). The percentage of mandated participants (82% PAs vs 85% non-PAs) was also similar between the 2 groups (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected Demographics for Physician Assistant (PA) vs non-PA Providers (n = 148).

| PA (n = 56) | Non-PA (n = 92) | |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of respondents | 38% | 62% |

| Practice for 10 years or less | 49 (88%) | 55 (60%) |

| At least half of time in direct patient care | 47 (84%) | 69 (75%) |

| Specialty type: | ||

| Medical specialties | 46 (82%) | 78 (85%) |

| Surgical specialties | 6 (11%) | 4 (4%) |

| Both medical and surgical | 4 (7%) | 10 (11%) |

| Practice setting: | ||

| Outpatient | 2 (4%) | 36 (39%) |

| Inpatient | 54 (96%) | 41 (45%) |

| Equal inpatient and outpatient | 0 (0%) | 15 (16%) |

| Mandated to take workshop | 46 (82%) | 78 (85%) |

| Had prior communication skills training | 12 (22%) | 24 (26%) |

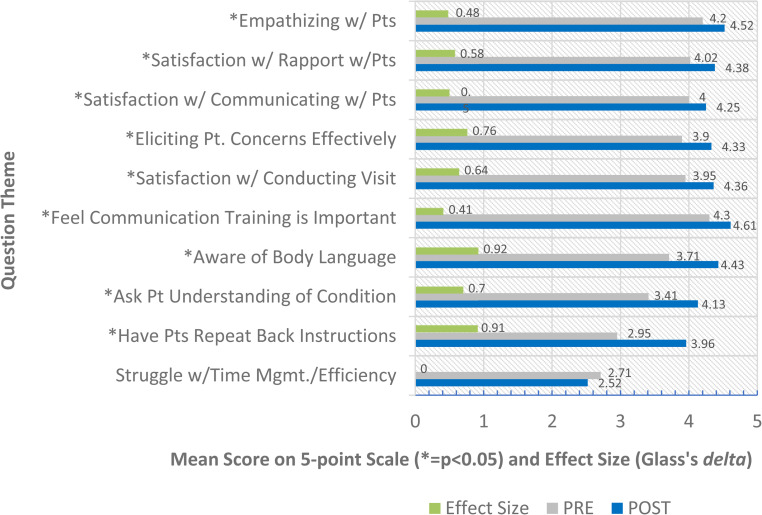

In 9 out of the 10 domains measured, there was a significant positive change among PAs in self-reported attitudes, and behaviors related to CST, communicating with patients, and communication skills taught (P < .05). There was no significant change in perceived time efficiency during visits. In total, 5 out of 9 domains had a moderate positive effect size (≥0.5 but <0.8). Awareness of body language and having patients repeat back instructions had a large positive effect size ≥0.8. Significant changes were similar among non-PA participants (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PA retrospective pre-post survey responses 6-weeks post-CST workshop n=56. Abbreviations: PAs, physician assistants; CST, communication skills training.

In the covariate analysis of all 148 respondents there was a significant difference (P < .05) between some PA and non-PA responses. PAs were more likely than non-PAs to report a significant improvement in their awareness of their body language when speaking to patients (P < .002), having patients repeat back instructions (P < .003), asking patients about the understanding of their condition (P < .012), and being satisfied with their patient visits (P < .034).

In addition, significant differences (P < .05) were found in 3 other PA-specific covariates related to specialty and time spent in direct care. After completing the CST workshop, PAs who were in surgical specialties tended to be more aware of their body language compared to those in non-surgical specialties (P < .031), PAs who spent a greater percentage of their time directly caring for patients were more likely to state that they were satisfied with their rapport with patients (P < .02) and to state that they were eliciting their patients’ concerns effectively compared to those with less time spent in direct patient care (P < .035).

Discussion

The results of this study add to the body of literature supporting the positive effects of CST which have been shown to improve patient experience, HCP well-being, and patient safety outcomes when taught to HCPs such as physicians and nurses. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the impact of a multidisciplinary, hospital-wide CST specifically on the attitudes and behaviors of PAs. Although further study is needed, increased use of behaviors promoting the use of communication skills among PAs could be expected to lead to similar improvements seen among other HCPs after completing CST (49).

The mixed-provider workshops also allowed the study of differences among PAs and non-PAs showing that PAs experienced a stronger positive effect in skills relating to non-verbal communication, relaying of instructions to patients, communicating with patients about their medical condition and general satisfaction with their patient interactions. The multidisciplinary nature of the workshops also suggested that there may be specific benefits to PAs in surgical disciplines in non-verbal communication skills, and that PAs with primarily patient care duties also benefited to a greater degree.

In our covariate analysis PAs were more likely than non-PAs to report a significant increase in using specific communication skills after CST compared to before CST. Some skill areas of note were the awareness of body language, use of communication skills to give patient education such as having patients repeat back instructions, and asking patients about the understanding of their condition. In addition to increased awareness of body language among PAs overall, PAs who were in surgical specialties were found to have more awareness of their body language compared to those in nonsurgical specialties. One possible reason for these findings may be the variability of how much specific skills are emphasized in PA school and training overall. In addition, for PAs in surgical specialties body language may not be a skill that is emphasized by peers in surgical practice as much as in nonsurgical practice.

Other findings in the covariate analysis were related to areas associated with positive connections with patients. PAs were more satisfied with their patient visits after CST compared to non-PAs. Those with a greater percentage of time in direct patient care were more satisfied with their rapport with patients and felt they were eliciting their patients’ concerns more effectively.

Other strengths of this study include the study setting in a hospital-wide implementation program with a mixed cohort of medical specialties and HCP types which can make the results more applicable to large hospital systems and a diverse learner group. The use of the retrospective pre-post format also limits response shift bias.

Findings could have been strengthened by objective measures of communication such as patient satisfaction scores, observation by trained raters or a validated survey. Although our survey measured changes in learning objectives specific to our institution's CST workshop, it was not a validated questionnaire such as the SE-12 to measure self-efficacy (50). We chose to continue to use our own survey questions to allow ease of comparison with previous groups we had studied and surveyed within our institution and to give a manageable amount of survey questions put forth to participants engaged in busy clinical care. Another limitation of this study was the low response rate.

In addition, the effects of length of workshop and mandated attendance were not specifically addressed in this study. This information could help inform the influence of CST length and mandated participation on HCPs. As prior studies examining the impact of CST have focused on full-day or multi-day workshops and the PAs in our study experienced positive effects on CST even in a shorter 5-h workshop it is plausible that negative effects from the length of CST would not be found in the future studies. Since most PAs were mandated to attend the workshop, it is also plausible that the positive effects experienced by PAs after CST might occur despite mandated attendance. Future studies are needed to examine these effects.

Conclusions

In the US, PAs have been a growing part of the hospital workforce interfacing with patients since the 1970s with PAs increasingly being hired as HCPs in other countries as well. As institutions grapple with limited financial and human resources, the positive results of our study may be of interest to programs planning to expand CST to HCP groups such as PAs.

This study demonstrates a positive change in self-reported attitudes and behaviors toward CST, communicating with patients, and the use of communication skills among practicing PAs after completing CST. This study also shows unique impacts on PAs compared to non-PAs after completing CST in mixed HCP workshops. Future studies will need to explore these effects further.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092626 for Evaluation of Physician Assistants’ Self-Reported Attitudes and Behaviors After Completion of a Hospital-Wide Multidisciplinary Communication Skills Training Workshop by Minna Saslaw, Steven Kaplan, Martina Pavlicova, Marcy Rosenbaum and Dana R. Sirota in Journal of Patient Experience

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Biostatistics support for this work was provided by the Irving Institute at Columbia University through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Grant Number UL1TR001873. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB's approved protocol AAA06353.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB's approved protocol AAA06353.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent for information to be published in this article was not obtained because the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB determined that this research met the regulatory guidelines for exemption from review by the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB. Per the Columbia University Irving Medical Center IRB, studies with exemption from review do not require informed consent. Participants were all informed verbally that the surveys were voluntary and de-identified.

ORCID iD: Minna Saslaw https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0229-8571

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.AAPA. American Academy of physician assistants: competencies for the physician assistant profession [updated 2021. Accessed https://www.aapa.org/career-central/employer-resources/employing-a-pa/competencies-physician-assistant-profession/.

- 2.Jones PE. Physician assistant education in the United States. Acad Med. 2007;82(9):882‐7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f7c0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolderslund M, Kofoed P-E, Ammentorp J. The effectiveness of a person-centred communication skills training programme for the health care professionals of a large hospital in Denmark. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(6):1423‐30. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammentorp J, Bigi S, Silverman J, Sator M, Gillen P, Ryan W, et al. Upscaling communication skills training – lessons learned from international initiatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(2):352‐9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. London: CRC Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. J Med Pract Manage. 2001;16(4):184‐91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553‐9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540310051034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(3):213‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796‐804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambady N, LaPlante D, Nguyen T, Rosenthal R, Chaumeton N, Levinson W. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5‐9. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez HP, Anastario MP, Frankel RM, Odigie EG, Rogers WH, von Glahn T, et al. Can teaching agenda-setting skills to physicians improve clinical interaction quality? A controlled intervention. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8(1):1‐7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284‐93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2010;29(7):1310‐8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12(4):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy MBA DM, Fasolino MD JP, Gullen MD DJ. Improving the patient experience through provider communication skills building. Patient Experience Journal. 2014;1(1):56‐60. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, Karafa M, Neuendorf K, Frankel RM, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755‐61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belasen AT, Oppenlander J, Belasen AR. The relationship between provider-patient communication and HCAHPS composite measures and hospital ratings. Available at SSRN. 2020;3518898. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed P-E, Mainz J. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):270‐7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunting M, Cagle JG. Impact of brief communication training among hospital social workers. Soc Work Health Care. 2016;55(10):794‐805. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2016.1231743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho IP, Pais VG, Almeida SS, Ribeiro-Silva R, Figueiredo-Braga M, Teles A, et al. Learning clinical communication skills: outcomes of a program for professional practitioners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(1):84‐9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung H-O, Oczkowski SJ, Hanvey L, Mbuagbaw L, You JJ. Educational interventions to train healthcare professionals in end-of-life communication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1‐13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0506-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulbrandsen P, Jensen BF, Finset A, Blanch-Hartigan D. Long-term effect of communication training on the relationship between physicians’ self-efficacy and performance. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):180‐5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norgaard B, Ammentorp J, Ohm Kyvik K, Kofoed PE. Communication skills training increases self-efficacy of health care professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2012;32(2):90‐7. doi: 10.1002/chp.21131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shama ME, Meky FA, Enein A, Mahdy M. The effect of a training program in communication skills on primary health care physicians knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2009;84(3–4):261‐83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker PA, Ross AC, Polansky MN, Palmer JL, Rodriguez MA, Baile WF. Communicating with cancer patients: what areas do physician assistants find most challenging? J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(4):524‐9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0110-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatt M, Lizano D, Carlese A, Kvetan V, Gershengorn HB. Severe burnout is common among critical care physician assistants: retracted. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1900–1906. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuang E, Lamkin R, Hope AA, Kim G, Burg J, Gong MN. I just felt like I was stuck in the middle": physician Assistants’ experiences communicating with terminally ill patients and their families in the acute care setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(1):27‐34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(1):4‐12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saslaw M, Sirota DR, Jones DP, Rosenbaum M, Kaplan S. Effects of a hospital-wide physician communication skills training workshop on self-efficacy, attitudes and behavior. Patient Exp J. 2017;4(3):48‐54. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iversen ED, Wolderslund M, Kofoed P-E, Gulbrandsen P, Poulsen H, Cold S, et al. Communication skills training: a means to promote time-efficient patient-centered communication in clinical practice. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2021;8(4):307‐14. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korc-Grodzicki B, Alici Y, Nelson C, Alexander K, Manna R, Gangai N, et al. Addressing the quality of communication with older cancer patients with cognitive deficits: development of a communication skills training module. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(4):419‐24. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hudak NM, Pinheiro SO, Yanamadala M. Increasing physician assistant Students’ team communication skills and confidence throughout clinical training. J Physician Assist Educ. 2019;30(4):219‐22. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown JB, Boles M, Mullooly JP, Levinson W. Effect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(11):822‐9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barth J, Lannen P. Efficacy of communication skills training courses in oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(5):1030‐40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2271‐81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones AH, Jacobs MB, October TW. Communication skills and practices vary by clinician type. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(4):325‐30. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.October TW, Dizon ZB, Hamilton MF, Madrigal VN, Arnold RM. Communication training for inter-specialty clinicians. Clin Teach. 2019;16(3):242‐7. doi: 10.1111/tct.12927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenzweig M, Hravnak M, Magdic K, Beach M, Clifton M, Arnold R. Patient communication simulation laboratory for students in an acute care nurse practitioner program. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(4):364‐72. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2008.17.4.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray LA, Buckley K. Using simulation to improve communication skills in nurse practitioner preceptors. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2017;33(1):33‐9. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drennan J, Hyde A. Controlling response shift bias: the use of the retrospective pre-test design in the evaluation of a master’s programme. Ass Eval Higher Educ. 2008;33(6):699‐709. doi: 10.1080/02602930701773026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konopasek L, Rosenbaum M, Encandela J, Cole-Kelly K. Evaluating communication skills training courses. In: Kissane DW. (ed) Oxford Textbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care . Oxford, UK: Oxford, 2010, p.399. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levinson W, Gordon G, Skeff K. Retrospective versus actual pre-course self-assessments. JOUR. 1990;13(4):445‐52. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pratt CC, McGuigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Eval. 2000;21(3):341‐9. doi: 10.1177/109821400002100305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38‐43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klatt J, Taylor-Powell E. Synthesis of literature relative to the retrospective pretest design. Presentation to the. 2005.

- 47.Glass GV, McGaw B, Smith ML. Meta-analysis in social research. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner HM III, Bernard RM. Calculating and synthesizing effect sizes. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord. 2006;33(Spring):42‐55. doi: 10.1044/cicsd_33_S_42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor F, Halter M, Drennan VM. Understanding patients’ satisfaction with physician assistant/associate encounters through communication experiences: a qualitative study in acute hospitals in England. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1‐11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4410-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Axboe MK, Christensen KS, Kofoed P-E, Ammentorp J. Development and validation of a self-efficacy questionnaire (SE-12) measuring the clinical communication skills of health care professionals. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1‐10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0798-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092626 for Evaluation of Physician Assistants’ Self-Reported Attitudes and Behaviors After Completion of a Hospital-Wide Multidisciplinary Communication Skills Training Workshop by Minna Saslaw, Steven Kaplan, Martina Pavlicova, Marcy Rosenbaum and Dana R. Sirota in Journal of Patient Experience