Abstract

Background:

Garcinia cambogia, either alone or with green tea, is commonly promoted for weight loss. Sporadic cases of liver failure from G. cambogia have been reported, but its role in liver injury is controversial.

Methods:

Among 1418 patients enrolled in the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) from 2004 to 2018, we identified 22 cases (adjudicated with high confidence) of liver injury from G. cambogia either alone (n=5) or in combination with green tea (n=16) or Ashwagandha (n=1). Control groups consisted of 57 patients with liver injury from herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) containing green tea without G. cambogia and 103 patients from other HDS.

Results:

Patients who took G. cambogia were between 17 to 54 years, with liver injury arising 13 to 223 days (median = 51) after the start. One patient died, one required liver transplantation, and 91% were hospitalized. The liver injury was hepatocellular with jaundice. Although the peak values of aminotransferases were significantly higher (2001 ± 1386 U/L) in G. cambogia group (p <0.018), the median time for improvement in total bilirubin (TB) was significantly lower compared to the control groups (10 vs. 17 and 13 days, p = 0.03). The presence of HLA-B*35:01 allele was significantly higher in the G. cambogia containing HDS (55%) compared to patients due to other HDS (19%) (p = 0.002) and those with acute liver injury from conventional drugs (12%) (p = 2.55×10−6).

Conclusions:

The liver injury caused by G. cambogia and green tea is clinically indistinguishable. The possible association with HLA-B*35:01 allele suggests an immune-mediated mechanism of injury.

Keywords: herbal and dietary supplement, hepatotoxicity, weight loss supplement

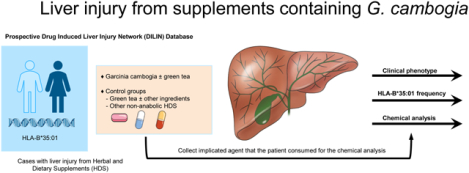

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity continues to rise across the world.1 Behavior and lifestyle modification with a decrease in calorie consumption is the standard approach to achieve the desired weight loss. However, long-term success is limited and resource-intensive.2,3 There are approved therapies for weight loss that work through appetite suppression.4 Unfortunately, these medications have not had much success due to the cost and side effects resulting in low compliance rates.4,5 The perception that certain plant extracts effectively reduce body weight through appetite suppression is common.6 Therefore, herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) are trendy for weight loss or to avoid weight gain. Their use has steadily increased over time due to aggressive marketing strategies and burgeoning sales through the Internet and social media.7–9 The HDS product adoption rate is very high due to perceived safety from the belief that the product is natural in origin.10 In one extensive survey of 3500 adults in the United States, many users and non-users of HDS had misperceptions about these products, wrongly believing that they had been evaluated for safety and efficacy by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before marketing and that dietary supplements are safer than over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications.11

Garcinia cambogia (Malabar tamarind) is native to India and Southeast Asia.12 The rind contains a chemical called hydroxycitric acid (HCA) that has been purported to decrease appetite.12–14 HDS with G. cambogia or HCA, either alone or in combination with other ingredients, commonly green tea, are marketed for weight loss.13,15–17 Most studies in humans have been conducted over a short duration with a limited number of study participants.18–20 The doses used in these studies ranged from 1000 mg 1500 mg of HCA per day. None of these studies have shown if the weight loss if any persists beyond the 12 weeks of intervention.18–20 Concerning toxicity and safety, studies conducted in experimental animals have not reported increased mortality or significant toxicity.13,21 Furthermore, at the doses usually administered, no differences have been reported in terms of side effects or adverse events (those studied) in G. cambogia and control groups.18–20 It was therefore believed to be safe, and its potential for hepatotoxicity was not questioned.22 However, rare cases of liver injury or failure requiring liver transplantation after the use of G. cambogia have been reported.23–27

In one recent paper from the Drug-induced Livery Injury Network (DILIN) consortium, the HLA-B*35:01 allele was found in 72% of patients with green tea-associated liver injury and more than 90% of those where the injury was judged as highly likely or definite.28 It is unknown if liver injury from G. cambogia is also associated with this allele. In this study, we analyzed cases of G. cambogia either alone or in combination with green tea enrolled in the US DILIN between September 2004 and April 2018 and described the clinical, laboratory, and histopathological features of the injury. We then compared the differences in clinical phenotype (patterns and trends in liver biochemistries and clinical outcomes) between liver injury from G. cambogia, green tea without G. cambogia, and other non-anabolic steroid containing HDS. Furthermore, we examined the prevalence of HLA-B*35:01 allele frequency in cases of liver injury from G. cambogia containing HDS compared to patients due to other HDS (non-anabolic steroid HDS) and patients with acute liver injury due to conventional drugs. Finally, in cases where we collected the implicated supplements from the patients, we performed chemical analyses to identify the presence of G. cambogia, its active ingredient HCA, and green tea extract and compared it with the package label.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The clinical protocols and study design of the DILIN are previously reported.29 Institutional Review Boards approved the DILIN Prospective Study (NCT00345930) at participating centers. Briefly, DILIN is an NIH-funded consortium of 5 to 8 medical centers in the United States where incident cases of suspected drug-induced liver injury are prospectively enrolled and followed with a standardized causality evaluation.29 The eligibility criteria includes suspected liver injury related to consumption of drug or HDS product in 6-month period prior to enrollment with documented clincially important drug-induced liver injury (DILI) defined ast ALT or AST > 5 × ULN or ALP >2 × ULN confirmed on at least two consecutive blood draws in patients with previously normal values. Known, pre-existing autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis or acetaminophen hepatotoxicity was excluded. Serologic work up was performed to rule out competing etiology per protocol. A diagnosis of chronic DILI was assigned when liver test abnormalities persisted at the time of 6 month follow up visit. All eligible patients underwent medical history, physical examination, and chart review for relevant data on the liver injury after informed consent. If a liver biopsy was done as a part of clinical care, unstained slides were requested for standardized central reading. Causality assessment was assessed through review of case narratives and case report forms and scored for the likelihood that G. cambogia played a role in causation, as 1 (definite, >95% likelihood), 2 (highly likely, 75–95% likelihood), 3 (probable, 50–74%), 4 (possible, 25–49%) or 5 (unlikely, <25%).29 Each case was also assessed for severity of injury based on the DILIN’s severity scoring system.30 In 2009, a repository was set up with standardized protocols. Patients were asked to provide samples of the implicated products. These were collected and shipped to the supplement repository, where they entered into a database, photographed, and aliquoted.31,32 Chemical analyses of these products were performed at the National Center for Natural Products Research of the University of Mississippi using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MS).33 The results of the chemical analyses were not available at the time of causality assessment.

For the current study, only high confidence cases of HDS-related liver injury (causality scores 1 to 3), were assessed for demographic, clinical, biochemical, and histologic features. The product labels of the implicated HDS were photographed whenever possible. When the product label was not available, the ingredients were sought from the Dietary Supplement Label Database or the Internet. The investigators based the causality scores on clinical information only, without knowledge of the chemical analyses or genetic results. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) testing was performed using established protocols.28 Descriptive statistics were computred for demographic and patient characteristics by mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (lowest, highest) for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. Differences between the groups were tested using the nonparametric test (Kruskal-Wallis test among groups of GC containing HDS, GT containing HDS and other HDS, Wilcoxon between GC alone and GC+GT groups) for continuos variables and chi-square test (or Fisher exact test for those with low frequencies) for categorical variables. HLA allele carriage frequency was defined as the proportion of patients carrying the corresponding allele. Fisher exact tests were performed to compare each HLA allele’s carriage frequency in DILI cases due to G. cambogia containing HDS and DILI cases from other non-anabolic steroid HDS and conventional drugs. Results were reported as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Significance was determined by p<0.05. Statistical analyses used SAS 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and R 4.0.2 (R Foundation). All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

There were 1987 patients enrolled in the DILIN Prospective Study between September 2004 and April 2018. Of these patients, 1768 had undergone follow-up and causality assessment, and 1414 were judged as probable, highly likely, or definite drug-induced liver injury. Among these verified cases, 272 (19%) were attributed to an HDS product. A review of product labels of implicated agents for mention of G. cambogia, HCA, green tea, or its component catechins or epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) identified 22 cases of G. cambogia either alone (n=5 with causality assessment scored as 1 in one patient, 2 or 3 in two patients each) or in combination with green tea (n=16, scored as 1 in four patients, 2 in ten patients, and 3 in two patients) or Ashwagandha (n=1, scored as 3). The control groups consisted of 57 patients with liver injury from green tea alone or with other ingredients (except G. cambogia), 103 patients with liver injury from other non-anabolic steroids HDS, and 1143 patients with liver injury from conventional drugs.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes

The demographic, clinical, and biochemical features of the 22 cases of G. cambogia-related liver injury are given in Table 1. The patients’ median age was 35 years, 55% were women, most were white (64%), but strikingly 41% were of self-reported Hispanic ethnicity. The stated reason for taking the supplement was weight loss in 82%. At the time of enrollment, laboratory results demonstrated marked elevations in serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferase (ALT and AST) with only modest increases in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels so that all except four subjects (82%) had a hepatocellular pattern of enzyme elevations; three subjects had a “mixed” and one a cholestatic pattern (Table 1). Immunologic features were not prominent; only three patients mentioned a rash and two fever, one patient having both (Table 1). The liver injury severity was scored as moderate in 11 (59%) and severe in 7 (32%) cases. There was one death, and one patient required liver transplantation within three months of disease onset. Chronic DILI occurred in 2 of the 19 patients in whom 6-month follow-up data were available.

Table 1.

Selected demographic, clinical, and biochemical results, clinical course, and outcomes of cases with liver injury from herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) containing Garcinia cambogia (GC), green tea (GT), or Others (non-anabolic steroid HDS).

| Characteristic | GC containing HDS (N=22) |

GT containing HDS (N=57) |

Other HDS (N=103) |

P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (Min, Max) | 35 (17, 54) | 41 (21, 80) | 53 (21, 81) | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 12/22 (55%) | 38/57 (67%) | 66/103 (64%) | 0.600 |

| Self-reported race | 0.343 | |||

| • White or Caucasian | 14/22 (64%) | 45/56 (80%) | 71/103 (69%) | |

| • Black or African American | 2/22 (9%) | 4/56 (7%) | 10/103 (10%) | |

| • Asian | 1/22 (5%) | 1/56 (2%) | 10/103 (10%) | |

| • Other/Multiracial | 5/22 (23%) | 6/56 (11%) | 12/103 (12%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 9/22 (41%) | 19/56 (34%) | 20/103 (19%) | 0.037 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.6 (16.4) | 79.8 (20.2) | 73.1 (18.7) | 0.011 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.6 (4.8) | 28.6 (6.8) | 26.4 (5.4) | 0.034 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions | ||||

| • Prior drug allergies | 3/22 (14%) | 14/57 (25%) | 42/103 (41%) | 0.015 |

| • Alcohol use | 12/22 (55%) | 28/52 (54%) | 50/99 (51%) | 0.897 |

| • Chronic hepatitis C | 2/22 (9%) | 1/57 (2%) | 2/103 (2%) | 0.188 |

| Temporal association | ||||

| • Days from primary drug start to earliest sign or symptom | 51.0 (13.0, 223.0) | 65.5 (11.0, 442.0) | 59.5 (0.0, 1885.0) | 0.623 |

| • Days from primary drug start to DILI onset | 71.5 (16.0, 424.0) | 74.5 (15.0, 448.0) | 61.0 (1.0, 1891.0) | 0.153 |

| Signs and symptoms at DILI onset | ||||

| • Jaundice | 19/22 (86%) | 47/57 (83%) | 71/103 (69%) | 0.072 |

| • Nausea | 15/22 (68%) | 41/57 (72%) | 52/103 (51%) | 0.020 |

| • Fever | 3/22 (14%) | 6/57 (11%) | 16/103 (16%) | 0.678 |

| • Abdominal pain | 12/22 (55%) | 24/57 (42%) | 49/103 (48%) | 0.589 |

| • Rash | 2/22 (9%) | 8/57 (14%) | 13/103 (13%) | 0.839 |

| • Itching | 10/22 (46%) | 24/57 (42%) | 39/103 (38%) | 0.751 |

| Liver biopsy performed | 16/22 (73%) | 31/57 (54%) | 61/102 (60%) | 0.329 |

| Treated with Prednisone or Other Corticosteroids | 2/22 (9%) | 7/57 (12%) | 18/101 (18%) | 0.458 |

| At the date of DILI onset | ||||

| • ALT (U/L) | 1975 (1400) | 1650 (1418) | 1091 (1228) | 0.003 |

| • AST (U/L) | 1679 (1958) | 1081 (944) | 900 (1278) | 0.018 |

| • Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 170 (66) | 228 (238) | 246 (184) | 0.094 |

| • Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (TB) | 9.3 (5.7) | 9.4 (7.5) | 8.2 (8.0) | 0.244 |

| • INR | 1.4 (0.50) | 1.5 (0.86) | 1.6 (1.12) | 0.907 |

| Pattern of liver injury at DILI onset or earliest after onset (R-value) | 0.160 | |||

| • Hepatocellular (> 5) | 18/22 (82%) | 46/57 (81%) | 69/103 (67%) | |

| • Mixed (2–5) | 3/22 (14%) | 4/57 (7%) | 21/103 (20%) | |

| • Cholestatic (<2) | 1/22 (4.5%) | 7/57 (12%) | 13/103 (13%) | |

| Peak Value from DILI onset to month 6 visit, means (SD) | ||||

| • ALT (U/L) | 2010 (1388) | 1680 (1437) | 1238 (1260) | 0.008 |

| • AST (U/L) | 1767 (1934) | 1335 (1103) | 1065 (1424) | 0.018 |

| • Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 215 (80) | 262 (234) | 309 (241) | 0.267 |

| • Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 18.6 (13.8) | 16.7 (11.44) | 13.6 (11.38) | 0.103 |

| Median Days from onset to peak serum TB (min, max) | 7 (0, 39) | 7 (0, 77) | 7 (0, 178) | 0.834 |

| Median Days from peak to a 50% reduction in serum TB | 10.0 | 17.0 | 13.0 | 0.030 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Patient was hospitalized or non-DILI hospitalization was prolonged | 20/22 (91%) | 38/57 (67%) | 67/103 (65%) | 0.055 |

| All death | 1/22 (5%) | 1/57 (2%) | 6/103 (6%)* | 0.579 |

| All liver-related death | 0/21 | 0/56 | 0/97 | NC |

| All liver transplant | 1/22 (5%) | 4/57 (7%) | 7/103 (7%) | 0.927 |

| Chronic DILI | 2/19 (11%) | 4/41 (10%) | 12/89 (14%) | 0.933 |

| Severity Score | 0.126 | |||

| • Mild | 0/22 | 8/57 (14%) | 24/103 (23%) | |

| • Moderate | 2/22 (9%) | 12/57 (21%) | 14/103 (14%) | |

| • Moderate-hospitalized | 11/22 (50%) | 21/57 (37%) | 31/103 (30%) | |

| • Severe | 7/22 (32%) | 11/57 (19%) | 22/103 (21%) | |

| • Fatal | 2/22 (9%) | 5/57 (9%) | 12/103 (12%) |

All values are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or number (proportion) with denominator given when there are missing data unless otherwise mentioned.

R = alanine aminotransferase ÷ alkaline phosphatase, both expressed as multiples of the upper limit of the normal range. TB = total bilirubin.

One patient died after undergoing liver transplant.

Comparison with cases ascribed to HDS containing green tea and HDS from other ingredients revealed that patients with DILI due to G. cambogia were significantly younger, more often Hispanic, and had higher serum aminotransferase levels both at the time of study enrollment and peak values. The mean time from onset to peak total bilirubin values was 7 days and was not different among the three groups, but the G. cambogia containing HDS group had significantly faster improvement in total bilirubin levels (10 days vs. 17 and 13 days, P=0.03) (Table 1).

HLA Association

HLA testing was performed on 22 patients in the G. cambogia group, 96 in the other HDS group, and 1113 in the conventional drug group. The presence of HLA-B*35:01 allele was 55% (60% in those where G. cambogia was the only product taken) in the G. cambogia containing HDS group compared to 19% (18 of the 96) in cases ascribed to other HDS, and 12% (133 of 1113) in the conventional drug group. The carriage frequency of the HLA-B*35:01 allele was significantly higher in the G. cambogia cases than the other HDS [OR = 5.1 (1.7, 15.6), P= 0.0018] and the conventional drug group [OR =8.8 (3.4, 23.2), P=2.55×10−6], respectively.

G. cambogia alone vs. G. cambogia with Green Tea

Comparison of cases with liver injury from HDS with G. cambogia alone vs. G. cambogia with green tea (Table 2) failed to show any differences in demographics, clinical characteristics, biochemical patterns, and temporal trends of liver tests. The clinical outcomes were not different (Table 2). Liver biopsy slides were available for central review in 2 of the 5 patients with G. cambogia alone group compared to 5 of the 16 patients in the G. cambogia with green tea group. The histology revealed varying degrees of hepatitis (mainly acute), with some cases demonstrating cholestasis. There were no characteristic differentiating histologic features between the patients with liver injury from HDS containing G. cambogia with and without green tea.

Table 2.

Select demographic, clinical, and biochemical results, clinical course, and outcomes of cases with liver injury from Garcinia cambogia (GC) alone or in combination with green tea (GT). All values are expressed as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise mentioned.

| GC Alone (n=5) | GC + GT (n=16) | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years median (min, max) | 34.9 (33.3, 37.2) | 33.4 (26.6, 43.6) | 0.741 |

| Female gender | 4/5 (80%) | 7/16 (44%) | 0.311 |

| Self-reported race | 0.356 | ||

| • White or Caucasian | 3/5 (60%) | 11/16 (69%) | |

| • Black or African American | 0/5 | 2/16 (13%) | |

| • Asian | 1/5 (20%) | 0/16 | |

| • Other/Multiracial | 1/5 (20%) | 3/16 (19%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1/5 (20%) | 7/16 (44%) | 0.606 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7 (3.5) | 28.6 (5.2) | 0.965 |

| Liver injury | |||

| Days from primary drug start to DILI onset, median (min, max) | 87 (35, 139) | 72 (16, 424) | 0.710 |

| Signs and symptoms at DILI onset | |||

| • Jaundice | 3/5 (60%) | 15/16 (94%) | 0.128 |

| • Nausea | 3/5 (60%) | 11/16 (69%) | >0.999 |

| • Fever | 0/5 | 3/16 (19%) | 0.549 |

| • Abdominal pain | 2/5 (40%) | 10/16 (63%) | 0.611 |

| • Rash | 0/5 | 2/16 (13%) | >0.999 |

| • Itching | 1/5 (20%) | 8/16 (50%) | 0.338 |

| Liver enzymes at the date of DILI onset | |||

| • ALT (U/L) | 2383 (1211) | 1870 (1514) | 0.315 |

| • AST (U/L) | 1489 (754) | 1803 (2286) | 0.458 |

| • Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 198 (62) | 160 (69) | 0.127 |

| • Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 8.3 (5.6) | 9.7 (6.1) | 0.689 |

| • INR | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.5 (0.6) | 0.551 |

| Pattern of liver injury at DILI onset or earliest after onset (R-value) | >0.999 | ||

| • Hepatocellular (>5) | 4/5 (80%) | 13/16 (81%) | |

| • Mixed (2–5) | 1/5 (20%) | 2/16 (13%) | |

| • Cholestatic (<2) | 0/5 | 1/16 (6%) | |

| Peak values from DILI onset to month 6 visit, means (SD) | |||

| • ALT (U/L) | 2493 (1002) | 1890 (1523) | 0.322 |

| • AST (U/L) | 1536 (655) | 1900 (2240) | 0.741 |

| • Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 215 (60) | 218 (89) | 0.836 |

| • Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 21.4 (12.6) | 18.5 (14.6) | 0.457 |

| • INR | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.6 (0.4) | 0.535 |

| Time to peak and recovery (total bilirubin peak must be >=2.5 mg/dL) | |||

| • Days from onset to peak | 18 (1, 39) | 7 (0, 37) | 0.220 |

| • Days from peak to <2.5 mg/dL | 39 | 35 | 0.337 |

| • Days from peak to a 50% reduction from the peak | 10 | 10 | 0.903 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Patient was hospitalized or non-DILI hospitalization was prolonged | 5/5 (100%) | 14/16 (88%) | >0.999 |

| All death | 0/5 | 1/16 (6%) | >0.999 |

| All liver-related death | 0/5 | 0/15 | NC |

| All liver transplant | 1/5 (20%) | 0/16 | 0.238 |

| Chronic DILI | 1/4 (25%) | 1/14 (7%) | 0.405 |

| Severity Score | 0.180 | ||

| • Mild | 0/5 | 0/16 | |

| • Moderate | 0/5 | 2/16 (13%) | |

| • Moderate-hospitalized | 4/5 (80%) | 6/16 (38%) | |

| • Severe | 0/5 | 7/16 (44%) | |

| • Fatal | 1/5 (20%) | 1/16 (6%) |

One case of GC with Ashwagandha was excluded from this analysis.

Chemical Analyses

Chemical analyses were available on 12 products provided by 8 of the 22 patients who consumed G. cambogia containing HDS (Table 3). Comparisons were made between the label claim and chemical profiling results. One product (patient 3) was without detectable catechins despite the label claim of a “diet spray” with green tea (Table 3). Interestingly, this product was also listed to have G. cambogia, and it was detected, suggesting that the liver injury was due to G. cambogia rather than the presumed green tea, based on the label. In another case (patient 7), the product label claim for G. cambogia was correct with detectable levels on chemical profiling. In this case, the product label did not claim for green tea extract or EGCG, suggesting that G. cambogia by itself can cause the liver injury that is very similar to green tea.

Table 3.

Names of products linked to Garcinia cambogia (GC) and green tea (GT) induced liver injury with chemical analysis.

| Patient | Garcinia cambogia /HCA | GT Extract/EGCG | Total Catechins | EGCG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label Claim | Chemical profiling | Label Claim | Chemical profiling | |||

| 1. | Mega-T Green Tea Extract | NO | Not detected | YES | Detected | Detected |

| 2. | Hydroxycut | YES | Detected | YES | Detected | Detected |

| 3. | Quick Loss Diet Spray with Hoodia | YES | Detected | YES | Not detected | Not detected |

| 4. | Visalus Sciences Vi-Slim Metab-Awake | NO | Not detected | YES | Detected | Detected |

| OmegaKrill Pure Concentrated Krill Oil | NO | Not detected | NO | Not detected | Not detected | |

| Visalus Sciences Neuro | NO | Not detected | YES | Detected | Detected | |

| Visalus Sciences Vi-Trim | YES | Detected | NO | Not detected | Not detected | |

| 5. | Hydroxycut | NO | Not detected | YES | Detected | Detected |

| 6. | Fat Burner | YES | Detected | YES | Detected | Detected |

| Great Start-Energy Formula | NO | Not detected | YES | Detected | Detected | |

| 7. | Garcinia Cambogia X Treme | YES | Detected | NO | Not detected | Not detected |

| 8. | Super Plus Weight Loss Enhancer | Yes | Not detected | Yes | Detected | Detected |

HCA: hydroxycitric acid, EGCG: epigallocatechin gallate.

DISCUSSION

Several individual case reports over the years have raised concern for the hepatotoxic potential of G. cambogia.23–25,34–36 The exact mechanism is unclear. One study in mice suggested that G. cambogia may increase hepatic collagen accumulation and lipid peroxidation resulting in oxidative stress.37 The study also revealed increased expression of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 resulting in hepatocyte injury and inflammatory response.37

The current study summarizes the clinical insights gained from several liver injury cases from G. cambogia, either alone or in combination, from the ongoing study of DILI in the United States.29,31,33 The clinical, biochemical, and histologic features of G. cambogia related liver injury were remarkably consistent and resembled green tea-related liver injury, i.e., acute hepatitis with a hepatocellular injury.28 The marked serum aminotransferase elevations almost always resulted in hospitalization with a severity that was at least moderate. The fatality rate (death or liver transplantation) was typical for acute, icteric hepatocellular drug-induced liver injury (2 of 22 jaundiced cases: 9%) as would be predicted by “Hy’s Law.”

Some striking observations made in the current study were that G. cambogia was used primarily by young women, mostly White and Hispanic, who were overweight but not obese. It is possible that sellers of HDS mainly target this select demographic for a natural product purported to aid in weight loss or prevent weight gain. Furthermore, the carrier frequency of HLA-B*35:01 in the cases with G. cambogia alone was 60% compared to controls with liver injury due to the other dietary supplements (19%), both higher than that found in the population controls (11%).28 Although the allele frequency was lower than what was reported recently with green tea-associated liver injury (72–90% depending on causality score), the hepatocellular pattern of enzyme elevations and moderate to a severe course with jaundice raises the possibility that G. cambogia liver injury is immune-mediated occurring in predisposed individuals.28 However, this association needs to be confirmed by other group of investigators with a larger sample size. The HLA allele, B*35:01, is found in 5% to 15% of US populations, rates modestly higher in Hispanics compared to Caucasians and African Americans.28,38 In the current study, 41% of G. cambogia containing HDS group were Latino/Hispanic ethnicity. The current study also builds on a Chinese population study that associates HLA-B*35:01 with DILI from yet another herbal product, Polygonum multiflorum.38 Together, these studies suggest that HLA-B*35:01 could potentially serve as a biomarker for predicting DILI associated with plant-based products.28,38 The molecular and immuno-pathogenetic bases for these striking associations deserve further study.

A limitation in the current study is that the chemical analyses were not available for all implicated HDS products. Among patients in whom the product was not available for analysis, the commonly reported reasons were either full use of the product or that the product had been discarded. No patient refused to part with their supply of the product if they were still in possession of it at the time of enrollment. The chemical analysis indicated that there were discrepancies between the label claim and chemical profiling. This finding is consistent with prior analysis from the DILIN cohort that showed that 51% of HDS products were mislabeled with chemical contents present that did not match the label.33 However, the chemical analysis available in the two illustrative cases, patients 3 and 7 (Table 3) provides definitive evidence that G. cambogia as a single ingredient can result in a liver injury similar to green tea. Another limitation inherent to the study design is the inability to use the chemical analyses’ results in the causality assessment. Foremost, these results are not available at the time of causality assessment, and the products are not always available to pursue this prospectively. For example, patients 3 and 8 (Table 3) were attributed to having a liver injury from a combination of G. cambogia and green tea based on the label and not on the chemical analysis. Although resegregation after the chemical analysis was not done, we do not believe that it will alter our current conclusions.

The profile of a young woman, perhaps overweight but not obese, White and Hispanic, is so innocuous that, unless the clinician actively pursues provoking questions during clinical history taking, G. cambogia as the implicated agent for liver injury could be easily missed. This situation emphasizes the need for clinicians to inquire about HDS use in all cases of acute hepatitis. Furthermore, the pattern of injury and levels of serum aminotransferases in 1700 to 2000 U/L range seen in this analysis are similar to liver injury from intentional or unintentional acetaminophen overdose. Lastly, the latency period, i.e., duration from the start of the HDS to DILI onset, is very broad -- up to a year. This long latency period is unusual and might falsely reassure patients and the clinicians treating these patients about G. cambogia as an implicated agent. The perception that the natural derived products are safe for consumption coupled with the assumption that these products are formally evaluated for safety prior to marketing needs to be addressed to avoid these, albeit rare, but serious adverse events that are preventable. Perhaps educational campaign targeting the at-risk consumer or publications of manuscripts such as these, in peer reviewed articles to increase the awareness among health care providers may help avert these unfortuate situations.

In summary, the current study provides evidence for the hepatotoxicity potential of G. cambogia containing HDS products. The clinical phenotype is akin to acute-hepatitis, similar to what one would see with acetaminophen overdose or viral hepatitis, arising two weeks to 12 months after start. Association with HLA B*35:01 allele, an emerging risk factor associated with plant-based dietary supplement-induced liver injury, further adds to the body of evidence. G. cambogia is often marketed with green tea; perhaps, the two are additive or synergistic in their adverse effects in genetically susceptible individuals.

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge with thanks the invaluable help of Hoss Rostami, BSMSE, for identifying product labels.

Funding:

Funded as a Cooperative Agreement by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases with support from the Intramural Division of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (to the Drug‐induced Liver Injury Network [https://dilin.dcri.duke.edu/]): U01‐DK065176 and U24‐DK065176 (Duke University), U01‐DK065211 (Indiana University), U01‐DK065201 (University of North Carolina), U01‐DK065184 (University of Michigan), U01‐DK065193 (University of Connecticut), U01‐DK065238 (University of California San Francisco/California Pacific Medical Center), U01‐DK083023 (University of Texas‐Southwestern), U01‐DK083020 (University of Southern California), U01‐DK082992 (Mayo Clinic), U01‐DK083027 (Thomas Jefferson/Albert Einstein Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania), and U01‐DK100928 (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai).

Disclosures:

Drs. Ahmad, Barnhart, Gu, Hoofnagle, Khan, Koh, Li, Serrano, and Stolz have no financial disclosures to report.

Dr. Bonkovsky has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years, he has served as a consultant to Alnylam Pharma, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, NA, and Recordati Rare Chemicals, NA, regarding porphyrias; and he serves as principal investigator at Wake Forest University for clinical trials in acute hepatic porphyria, erythropoietic protoporphyria, and primary sclerosing cholangitis, funded, respectively by Alnylam, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, and Gilead Sciences.

Dr. Durazo has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years, he has served as a member of the Drug Monitoring Committee of Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Fontana has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years he had received research support from Gilead Sciences, Abbvie Inc., and Bristol-Myers Squibb and consulting fees from Sanofi-Aventis.

Dr. Navarro has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past 3 years he had received research grant support from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the Albert Einstein Society of the Albert Einstein Medical Center.

Dr. Phillips has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years she has served as a consultant to Biocryst Pharma; she serves as Section Editor for Drug Allergy for UpToDate. She is co-director of IIID Pty Ltd that holds a patent for a method for identification and determination of hypersensitivity of a patient to abacavir.

Dr. Rockey has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past 3 years he has received research grants support for his institution from Connatus Pharmaceuticals, Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, Galectin Pharmaceuticals, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Sequana Medical, and has written chapters for UpToDate.

Dr. Seeff has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years, he has served as a member of the Drug Monitoring Committee for Second Genome, Lipocine, Enyo Pharmaceuticals, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, and KPB Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Tillman has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years, he has served as a consultant to Trevena Inc, and his wife is an employee of Abbvie Inc and holds stock in AbbVie Inc, Abbott Laboratories, and Gilead Sciences.

Dr. Vuppalanchi has no disclosures relevant to this manuscript. Within the past three years he has received consulting fees for serving on Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Labcorp/Covance, Enyio and Enanta. He also received research grant support to his institution from Gilead Sciences, Zydus Discovery, Cara Therapeutics and Intercept.

Abbreviations:

- HDS

herbal and dietary supplements

- DILIN

Drug-induced Liver Injury Network

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- eMERGE

the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Network

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

Footnotes

Clinical Trials.gov number: NCT00345930

REFERENCES

- 1.Collaboration, N. C. D. R. F. Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature 569, 260–264, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1171-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnaswami A et al. Real-World Effectiveness of a Medically Supervised Weight Management Program in a Large Integrated Health Care Delivery System: Five-Year Outcomes. Perm J 22, 17–082, doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers VH et al. Five-year medical and pharmacy costs after a medically supervised intensive treatment program for obesity. Am J Health Promot 28, 364–371, doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120207-QUAN-80 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elangovan A, Shah R & Smith ZL Pharmacotherapy for Obesity-Trends Using a Population Level National Database. Obes Surg 31, 1105–1112, doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04987-2 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tak YJ & Lee SY Anti-Obesity Drugs: Long-Term Efficacy and Safety: An Updated Review. World J Mens Health, doi: 10.5534/wjmh.200010 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Astell KJ, Mathai ML & Su XQ Plant extracts with appetite suppressing properties for body weight control: a systematic review of double blind randomized controlled clinical trials. Complement Ther Med 21, 407–416, doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.05.007 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homoud MK The sale of weight-loss supplements on the Internet: A lurking health care crisis waiting to strike. Heart Rhythm 6, 663–664, doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.03.001 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizvi RF et al. Analyzing Social Media Data to Understand Consumer Information Needs on Dietary Supplements. Stud Health Technol Inform 264, 323–327, doi: 10.3233/SHTI190236 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sfodera F, Mattiacci A, Nosi C & Mingo I Social networks feed the food supplements shadow market. British Food Journal 122, 1531–1548, doi: 10.1108/BFJ-09-2019-0663 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing S, Sharp LK & Touchette DR Weight loss drugs and lifestyle modification: Perceptions among a diverse adult sample. Patient Educ Couns 100, 592–597, doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.11.004 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillitteri JL et al. Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 790–796, doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.136 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/garcinia-cambogia (accessed June 27th 2021).

- 13.Ohia SE et al. Safety and mechanism of appetite suppression by a novel hydroxycitric acid extract (HCA-SX). Mol Cell Biochem 238, 89–103, doi: 10.1023/a:1019911205672 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jena BS, Jayaprakasha GK, Singh RP & Sakariah KK Chemistry and biochemistry of (−)-hydroxycitric acid from Garcinia. J Agric Food Chem 50, 10–22, doi: 10.1021/jf010753k (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattes RD & Bormann L Effects of (−)-hydroxycitric acid on appetitive variables. Physiol Behav 71, 87–94, doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00321-8 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Cortes M, Robles-Diaz M, Ortega-Alonso A, Medina-Caliz I & Andrade RJ Hepatotoxicity by Dietary Supplements: A Tabular Listing and Clinical Characteristics. Int J Mol Sci 17, 537, doi: 10.3390/ijms17040537 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payab M et al. Effect of the herbal medicines in obesity and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Phytother Res 34, 526–545, doi: 10.1002/ptr.6547 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayamizu K et al. Effects of garcinia cambogia (Hydroxycitric Acid) on visceral fat accumulation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 64, 551–567, doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2003.08.006 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heymsfield SB et al. Garcinia cambogia (hydroxycitric acid) as a potential antiobesity agent: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280, 1596–1600, doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1596 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opala T, Rzymski P, Pischel I, Wilczak M & Wozniak J Efficacy of 12 weeks supplementation of a botanical extract-based weight loss formula on body weight, body composition and blood chemistry in healthy, overweight subjects--a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur J Med Res 11, 343–350 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preuss HG et al. An overview of the safety and efficacy of a novel, natural(−)-hydroxycitric acid extract (HCA-SX) for weight management. J Med 35, 33–48 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burdock G, Soni M, Bagchi M & Bagchi D Garcinia cambogia toxicity is misleading. Food Chem Toxicol 43, 1683–1684; author reply 1685–1686, doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.05.011 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crescioli G et al. Acute liver injury following Garcinia cambogia weight-loss supplementation: case series and literature review. Intern Emerg Med 13, 857–872, doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1880-4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira V, Mathieu A, Soucy G, Giard JM & Erard-Poinsot D Acute Severe Liver Injury Related to Long-Term Garcinia cambogia Intake. ACG Case Rep J 7, e00429, doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000429 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yousaf MN, Chaudhary FS, Hodanazari SM & Sittambalam CD Hepatotoxicity associated with Garcinia cambogia: A case report. World J Hepatol 11, 735–742, doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i11.735 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bessone F et al. Herbal and Dietary Supplements-Induced Liver Injury in Latin America: Experience from the Latindili Network. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.011 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andueza N, Giner RM & Portillo MP Risks Associated with the Use of Garcinia as a Nutritional Complement to Lose Weight. Nutrients 13, doi: 10.3390/nu13020450 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoofnagle JH et al. HLA-B*35:01 and Green Tea Induced Liver Injury. Hepatology, doi: 10.1002/hep.31538 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalasani N et al. Features and Outcomes of 899 Patients With Drug-Induced Liver Injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology 148, 1340–1352 e1347, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.006 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548241/ (accessed on January 26th 2021).

- 31.Navarro VJ et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology 60, 1399–1408, doi: 10.1002/hep.27317 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vuppalanchi R et al. Herbal dietary supplement associated hepatotoxicity: an upcoming workshop and need for research. Gastroenterology 148, 480–482, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navarro V et al. The Contents of Herbal and Dietary Supplements Implicated in Liver Injury in the United States Are Frequently Mislabeled. Hepatol Commun 3, 792–794, doi: 10.1002/hep4.1346 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma A et al. Acute Hepatitis due to Garcinia Cambogia Extract, an Herbal Weight Loss Supplement. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2018, 9606171, doi: 10.1155/2018/9606171 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kothadia JP, Kaminski M, Samant H & Olivera-Martinez M Hepatotoxicity Associated with Use of the Weight Loss Supplement Garcinia cambogia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Reports Hepatol 2018, 6483605, doi: 10.1155/2018/6483605 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corey R et al. Acute liver failure associated with Garcinia cambogia use. Ann Hepatol 15, 123–126, doi: 10.5604/16652681.1184287 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YJ et al. Garcinia Cambogia attenuates diet-induced adiposity but exacerbates hepatic collagen accumulation and inflammation. World J Gastroenterol 19, 4689–4701, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4689 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C et al. HLA-B*35:01 Allele Is a Potential Biomarker for Predicting Polygonum multiflorum-Induced Liver Injury in Humans. Hepatology 70, 346–357, doi: 10.1002/hep.30660 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]