Abstract

The 6-anilinouracils are novel dGTP analogs that selectively inhibit the replication-specific DNA polymerase III of gram-positive eubacteria. Two specific derivatives, IMAU (6-[3′-iodo-4′-methylanilino]uracil) and EMAU (6-[3′-ethyl-4′-methylanilino]uracil), were substituted with either a hydroxybutyl (HB) or a methoxybutyl (MB) group at their N3 positions to produce four agents: HB-EMAU, MB-EMAU, HB-IMAU, and MB-IMAU. These four new agents inhibited Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium. Time-kill assays and broth dilution testing confirmed bactericidal activity. These anilinouracil derivatives represent a novel class of antimicrobials with promising activities against gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to currently available agents, validating replication-specific DNA polymerase III as a new target for antimicrobial development.

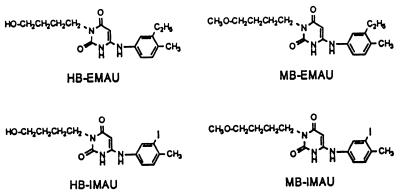

New antibacterial agents are needed to combat the multiply resistant gram-positive bacteria endemic in modern health care facilities (15). The 6-anilinouracils (AUs) illustrated in Fig. 1 are selective inhibitors of DNA polymerase III-c2 (pol III), an enzyme product of the polC gene (2, 8, 12). This enzyme is essential for the replication of the chromosome in gram-positive bacteria (7, 9, 17) and is found in low-G+C-content eubacteria, including staphylococci, enterococci, streptococci, Listeria species, Bacillus species, and clostridia (1, 8). Briefly, the AUs, inhibitors of the DNA pol III enzyme, act through their capacity to mimic the guanine moiety of dGTP by forming three hydrogen bonds with cytosine at one of the two active domains (6, 7, 14). This leaves the second active site on the inhibitor, the aryl domain, available to bind to DNA pol III, which sequesters the enzyme into a nonproductive complex with template primer DNA (19).

FIG. 1.

Structures of the four AUs used in this study: HB-EMAU, HB-IMAU, MB-EMAU, and MB-IMAU.

Structure-activity relationships of these AUs have been described previously (18, 19). The prototypic AUs, which have either weak antimicrobial activities or unacceptably low aqueous solubility (3–6, 13, 17), have now been substituted in their N3 positions and aryl rings to produce a series of more potent and more soluble molecules (13, 16, 19). The latest generation of these soluble forms (19) includes the N3-hydroxybutyl (HB) and N3-methoxybutyl (MB) derivatives of 6-[3′-ethyl-4′-methylanilino]uracil (EMAU) and 6-[3′-iodo-4′-methylanilino]uracil (IMAU) shown in Fig. 1. In this study, we describe the in vitro activities of HB-IMAU, HB-EMAU, MB-IMAU, and MB-EMAU against staphylococci and enterococci, bacteria that are pathogenic in humans and are difficult to treat with currently available and investigational antimicrobial agents.

(This work was presented in part at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 1999 [J. S. Daly, T. Giehl, N. C. Brown, C. Zhi, G. E. Wright, and R. T. Ellison III, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1808, 1999].)

Materials and methods.

Bacterial strains used in this study were unique clinical isolates collected in the clinical microbiology laboratory at UMass Memorial Health Care, Worcester, Mass. ATCC 29212 (Enterococcus faecalis) and ATCC 25923 (Staphylococcus aureus) were used as a control strains. Bacteria were initially subcultured on agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (PML Microbiologicals, Tulatin, Oreg.), heavy suspensions were made in Trypticase soy broth (BBL, Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) plus 15% glycerol, and the bacteria were frozen at −70°C. Aliquots were taken and subcultured overnight for susceptibility testing.

The following antibiotics were obtained from the sources indicated: clindamycin and linezolid, Pharmacia Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Mich.; quinupristin-dalfopristin, Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, Collegeville, Pa.; oxacillin, penicillin G, and rifampin, Sigma Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, Mo.; ofloxacin, Ortho-McNeil, Raritan, N.J.; and vancomycin, Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind. The pol III inhibitors HB-IMAU, HB-EMAU, MB-IMAU, and MB-EMAU were synthesized by methods described elsewhere (13, 19). The AUs were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted in Mueller-Hinton broth (MH broth; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) to a concentration of not higher than 1% dimethyl sulfoxide. Microbroth dilution testing was performed according to NCCLS standards (11) using MH broth, which was supplemented with 2% NaCl in oxacillin-containing wells for optimal growth of staphylococci. Antibiotic dilution plates were stored at −70°C and used within 12 weeks. Inocula were prepared by suspending growth from overnight incubation on Trypticase soy agar (TSA; BBL) in 4 ml of normal saline to yield an optical density at 450 nm of 0.6 to 0.7 (2 × 108 CFU/ml). The optical density of each culture was determined and compared to a standard growth curve. The 4-ml culture was diluted into 40 ml of saline for inoculating thawed MIC trays (2 × 107 CFU/ml). Plates were inoculated using a Dynatec MIC 2000 automatic inoculator to deliver the cell suspension to each 100-μl well. Plates were incubated for 20 to 24 h at 37°C and were read at both 18 h and 20 to 24 h. The number of colonies in at least one sample for each experiment was verified to ensure that an inoculum of at least 5 × 105 CFU was obtained. The lowest concentration of each antibiotic that prevented growth was recorded as the MIC. The minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) of each antibiotic was determined by plating the entire 100-μl contents of the last growth well and of each no-growth well onto a TSA plate. After overnight incubation, the concentration of antibiotic that gave 99.9% killing of the original inoculum was the MBC (10).

For time-kill assays, log-phase cultures in MH broth were diluted to ∼5 × 106 CFU/ml. One-milliliter test cultures were prepared with controls or antibiotics in MH broth; the MH broth was inoculated with 10% (100 μl) of the diluted culture to yield ≥5 × 105 CFU/ml. Each test culture was sampled after 0, 2, 4, and 24 h of growth at 37°C. The culture samples were diluted serially, plated onto TSA, and incubated for 48 h to determine colony counts.

Results and discussion.

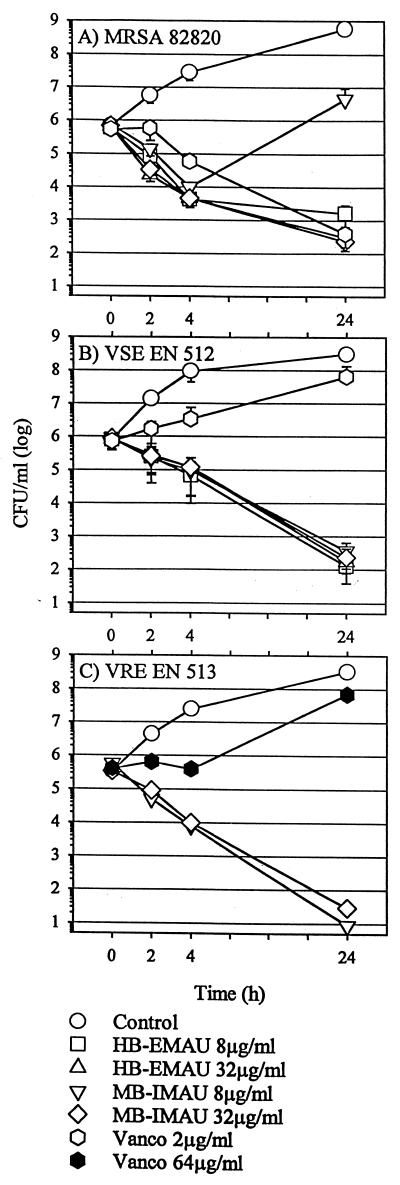

Results of microbroth dilution studies are shown in Table 1. Respective MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited of HB-IMAU, HB-EMAU, MB-IMAU, and MB-EMAU were as follows: 16, 16, 8, and 8 μg/ml for oxacillin-resistant S. aureus isolates; 16, 16, 16, and 16 μg/ml for oxacillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates; 32, 16, 16, and 8 μg/ml for coagulase-negative–oxacillin-susceptible staphylococci; 16, 8, 8, and 8 μg/ml for coagulase-negative–oxacillin-resistant staphylococci; 16, 8, 8, and 16 μg/ml for E. faecalis isolates; 16, 16, 16, and 16 μg/ml for vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium isolates; and 16, 16, 16, and 8 μg/ml for vancomycin-resistant E. faecium isolates. The novel AUs inhibited most strains at a concentration of 8 to 16 μg/ml, with there being no difference in the levels of activity against the oxacillin-resistant staphylococci or the vancomycin-resistant enterococci compared to those against the susceptible strains. There was no cross-resistance between the AUs and other inhibitors of DNA or RNA synthesis. The MICs for S. aureus ATCC 25923 were 8 to 32 μg/ml, and the MBCs were identical to the MICs for this strain in the cases of all four compounds. For the enterococcal control strain ATCC 29212 MICs were 4 to 8 μg/ml and MBCs were two to four times higher. The AUs were bactericidal to most of the clinical strains of staphylococci at one to two times their MICs and to the enterococci at one to four times their MICs. Time-kill assays, shown in Fig. 2 confirmed the bactericidal activities of HB-EMAU and MB-IMAU.

TABLE 1.

Activities of DNA pol III inhibitors and other antimicrobial agents against staphylococci and enterococci

| Organism | Relevant phenotype (no. of strains) | Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | Range | |||

| S. aureus | Oxacillin sensitive (15) | HB-IMAU | 16 | 16 | 8–32 |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 8–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | 1 | 2 | 0.5–4 | ||

| Synercid | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.125–0.25 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 0.5 | 16 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.125–4 | ||

| Vancomycin | 1 | 2 | 1–2 | ||

| Rifampin | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Penicillin G | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Oxacillin | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125–2 | ||

| Oxacillin resistant (17) | HB-IMAU | 16 | 16 | 8–32 | |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 8–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | 0.5–4 | ||

| Synercid | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25–1 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 16 | >16 | 0.25–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | >16 | >16 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 1–4 | ||

| Rifampin | ≤0.125 | 4 | ≤0.125–16 | ||

| Penicillin G | >16 | >16 | 4–>16 | ||

| Oxacillin | >8 | >8 | 4–>8 | ||

| Coagulase-negative S. aureus | Oxacillin sensitive (15) | HB-IMAU | 16 | 32 | 4–32 |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | ≤0.125 | 2 | ≤0.125–2 | ||

| Synercid | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.125–1 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25–16 | ||

| Clindamycin | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | ≤0.25 | 2 | ≤0.25–4 | ||

| Rifampin | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Penicillin G | ≤0.125 | 4 | ≤0.125–8 | ||

| Oxacillin | ≤0.125 | 2 | ≤0.125–2 | ||

| Oxacillin resistant (13) | HB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 4 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–8 | ||

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | ≤0.125–4 | ||

| Synercid | ≤0.125 | 1 | ≤0.125–2 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 16 | >16 | 0.25–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | >16 | >16 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | 4 | 4 | ≤0.25–8 | ||

| Rifampin | ≤0.125 | >16 | ≤0.125–>16 | ||

| Penicillin G | 8 | >16 | 1–>16 | ||

| Oxacillin | >8 | >8 | 4–>8 | ||

| E. faecium | Vancomycin sensitive (9) | HB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 8–16 |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Synercid | 1 | 4 | 1–4 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 4 | >16 | 2–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | 16 | >16 | 8–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | 8 | 16 | 1–16 | ||

| Rifampin | ≤0.125 | 16 | ≤0.125–16 | ||

| Penicillin G | 2 | >16 | 1–>16 | ||

| Oxacillin | >8 | >8 | >8 | ||

| Vancomycin resistant (23) | HB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 8–16 | |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 8–16 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | 2–8 | ||

| Synercid | 1 | 1 | 0.25–1 | ||

| Ofloxacin | >16 | >16 | 4–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | >16 | >16 | 0.25–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | >32 | >32 | >32 | ||

| Rifampin | 8 | 8 | ≤0.125–16 | ||

| Penicillin G | >16 | >16 | >16 | ||

| Oxacillin | >8 | >8 | >8 | ||

| E. faecalis | (32) | HB-IMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 |

| HB-EMAU | 8 | 8 | 4–8 | ||

| MB-IMAU | 8 | 8 | 2–16 | ||

| MB-EMAU | 8 | 16 | 4–16 | ||

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | 2–4 | ||

| Synercid | 4 | 8 | 2–16 | ||

| Ofloxacin | 4 | >16 | 1–>16 | ||

| Clindamycin | >16 | >16 | 8–>16 | ||

| Vancomycin | 2 | 8 | 1–>32 | ||

| Rifampin | 4 | 8 | 0.5–16 | ||

| Penicillin G | 4 | 8 | 2–16 | ||

| Oxacillin | >8 | >8 | 8–>8 | ||

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Results of time-kill assays showing the bactericidal activities of the AUs in comparison to those of vancomycin against an oxacillin-resistant S. aureus strain (SA 82820) (A), a vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis (VSE) strain (EN 512) (B), and a vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (VRE) strain (EN 513) (C). MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; Vanco, vancomycin.

HB-IMAU, HB-EMAU, MB-IMAU, and MB-EMAU are new representatives of a class of compounds that inhibit a novel target absolutely essential for the replication of the bacterial chromosome. These small molecules bind to the DNA pol III of low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria, including staphylococci and enterococci, pathogenic bacteria that have become increasingly resistant to currently available agents. These AUs have in vitro activities against other species, including Bacillus species and mycoplasmas, species that contain the same target DNA pol III, but further study is needed (19). They have no activity against the Enterobacteriaceae, as the target DNA polymerase is not found in gram-negative bacteria. Similarly, the target polymerase is not found in mammalian cells and the AUs do not bind to the mammalian polymerase alpha, the primary mammalian DNA polymerase (14). They are unrelated to available agents, to compounds currently being tested in clinical trials, and to antimicrobials used in animal feed. Two members of this class of antimicrobials, HB-IMAU and HB-EMAU, have been shown to have activity in a lethal S. aureus mouse peritonitis model, with 10 mg/kg of body weight providing protection equal to that of vancomycin at 20 mg/kg (19).

This study is the first to detail the in vitro activities of members of this class of antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates in comparison to those of available agents. There was no cross-resistance between these AUs and the fluoroquinolones or rifampin, other inhibitors of DNA and RNA synthesis. Similarly, no cross-resistance was detected with agents that exert their antibacterial action at the level of cell wall or protein synthesis. The AUs were bactericidal at one to four times their MICs for most strains.

The results of this study confirm the general hypothesis (14) that bacterial DNA pol III is a valid target for antimicrobial drug development, including the development of agents effective against clinically relevant organisms resistant to conventional antimicrobials. More specifically, our results demonstrate the strong potential of the AUs as model antibacterial agents. Given their potential, new forms of these AUs are under development with the objective of enhancing their aqueous solubility and in vitro potency, so that their safety and efficacy can be assessed in vivo against infections with relevant pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maureen Jankins, Brenda Torres, and Rosemary Dodge at the Clinical Microbiology Lab, UMass Memorial Health Care, for help with preparation of the MIC panels and collection of the bacterial strains. We thank Pharmacia Upjohn and Rhône-Poulenc Rorer for providing antimicrobial reference powders.

This work was supported in part by STTR phase I grant AI41260 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes M H, Leo C, Brown N C. DNA polymerase III of gram-positive eubacteria is a zinc metalloprotein conserving an essential finger-like domain. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15254–15260. doi: 10.1021/bi981113m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes M H, Tarantino P M, Spacciapoli P, Yu H, Brown N C, Dybvig K. DNA polymerase III of Mycoplasma pulmonis: isolation and characterization of the enzyme and its structural gene, polC. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:843–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown N C, Dudycz L W, Wright G E. Rational design of substrate analogues targeted to selectively inhibit replication-specific DNA polymerases. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1986;12:555–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown N C, Handschumacher R E. Inhibition of the synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid in bacteria by 6-(p-hydroxyphenylazo)-2,4-dihydroxypyrimidine: metabolic studies in Streptococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3083–3089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown N C, Gambino J J, Wright G E. Inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III. 6-(Arylalkylamino)uracils and 6-anilinouracils. J Med Chem. 1977;20:1186–1189. doi: 10.1021/jm00219a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements J E, D'Ambrosio J, Brown N C. Inhibition of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III by phenylhydrazinopyrimidines: demonstration of a drug-induced DNA:enzyme complex. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzarelli N R. The mechanism of action of inhibitors of DNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:641–668. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y-P, Ito J. The hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima has two different classes of family C DNA polymerases: evolutionary implications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5300–5309. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornberg A, Baker T. DNA replication. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman & Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Document M26-T. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. Tentative guideline. Vol. 12 1992. , no. 19. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Document M7-A3. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 3rd ed. 1993. Approved standard, vol. 13, no. 25. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacitti D F, Barnes M H, Li D H, Brown N C. Characterization and expression of Staphylococcus aureus polC, the structural gene for DNA polymerase III. Gene. 1995;165:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00377-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarantino P M, Zhi C, Gambino J J, Wright G E, Brown N C. 6-Anilino-uracil-based inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III: antipolymerase and antimicrobial structure-activity relationships based on substitution at uracil N3. J Med Chem. 1999;42:2035–2040. doi: 10.1021/jm980693i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarantino P M, Zhi C, Wright G E, Brown N C. Inhibitors of DNA polymerase III as novel antimicrobial agents against gram-positive eubacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1982–1987. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomasz A. Multiple-antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1247–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trantolo D J, Wright G E, Brown N C. Inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III. Influence of modifications in the pyrimidine ring of anilino- and (benzylamino)uracils. J Med Chem. 1986;29:676–681. doi: 10.1021/jm00155a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright G E, Brown N C. Deoxyribonucleotide analogs as inhibitors and substrates of DNA polymerases. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47:447–497. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90066-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright G E, Gambino J J. Quantitative structure-activity relationships of 6-anilinouracils as inhibitors of Bacillus subtilis DNA polymerase III. J Med Chem. 1984;27:181–185. doi: 10.1021/jm00368a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright G E, Brown N C. DNA polymerase III: a new target for antibiotic development. Curr Opin Anti-Infect Investig Drugs. 1999;1:45–48. [Google Scholar]