Abstract

Background:

Racial/ethnic minorities (REMs) continue to carry the burden of sexual health disparities in the United States, including increased health risks and lower proportions of preventative care. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been useful in developing interventions aimed at reducing these disparities. Specifically, partnership with the target group members has resulted in more culturally relevant intervention strategies.

Aim:

The purpose of this systematic review was to analyze existing research on sexual health interventions targeting U.S. REMs that were developed using CBPR, to highlight the role target group members played, and to explore the benefits and outcomes of these partnerships.

Method:

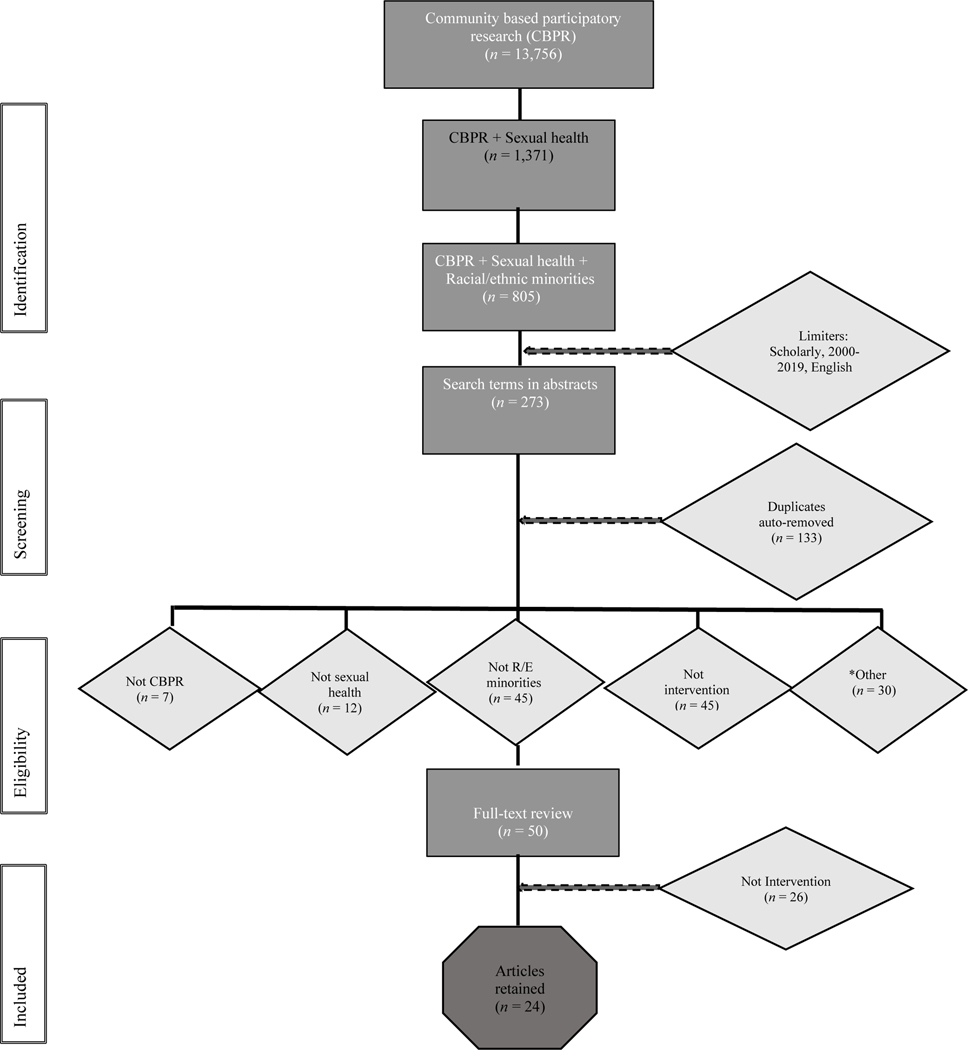

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guided the search of 46 thesauri terms for CBPR, sexual health, and REMs across six databases.

Results:

The initial search yielded 805 identified studies. After applying limiters, reviewing abstracts, and a full-text review, 24 appropriate studies were retained. The key findings indicated significant intervention outcomes such as increased health knowledge, attitude change, and behavioral intention that could reduce sexual risk-taking behaviors. Twelve studies detailed methods for partnering with target group members to formulate interventions, highlighting benefits related to recruitment, retention, and cultural relevance.

Discussion:

CBPR is well-positioned to address sexual health disparities among REMs. While community partnership strategies vary, the findings yield evidence that CBPR addressing sexual health disparities is achievable, can influence the effectiveness of interventions, and should be considered as an orientation in future sexual health research.

Keywords: Community-Based Participatory Research, sexual health, health disparity, racial/ethnic minority, underrepresented racial minority, intervention

Health equity is “the absence of disparities… among socioeconomic and demographic groups or geographical areas in health status and health outcomes” (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2019). Health inequity not only has a deleterious impact on the lives of underserved populations, but can also result in increased expenditures in public healthcare (Suthers, 2008). Health inequities impact several areas of well-being including sexual health, which is defined as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality” (World Health Organization [WHO], 2019). Within the U.S., optimal sexual health is not achieved equally across all communities, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities (REMs).

While REMs do not represent a monolithic group, there are several REM populations that have experienced documented sexual health inequities, including African Americans, American Indian/Alaskan Natives, and Latinx populations. These sexual health inequities are represented in areas such as unequal progress in HIV risk reduction for African Americans and Latinx individuals (CDC, 2019, CDC, 2020a, CDC, 2020b). Another area of sexual health inequity is increased STI transmission rates, with certain groups such as American Indian/Alaskan Natives experiencing rates as high as three times that of Whites (CDC, 2017). Racial/ethnic disparities also exist in access to preventative care measures (e.g., cervical cancer screenings, access to family planning services; Dehlendorf, Rodriguez, Levy, Borrero, & Steinauer, 2010; Musselwhite et al., 2016).

These unacceptable sexual health inequities must be acknowledged within the context of social determinants of health. Factors such as institutional racism and segregation, socioeconomic status, lack of treatment access, reasonable mistrust in the healthcare system, and disparate incarceration rates can all contribute to sexual health inequity among REMs (Hogben & Leichliter, 2008; CDC, 2020c). Due to these systemic issues, it cannot be assumed that generic intervention strategies (often developed by non-REM academicians) will be adequate at addressing the nuanced needs of REMs. Instead, new research strategies are necessary to support these communities to reduce these disparities and reach health equity.

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) has been described as the gold-standard for developing interventions for underserved communities (Kwon, Tandon, Islam, Riley, & Trinh-Shevrin, 2018; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). CBPR promotes collaboration between academic and community partners throughout the scientific inquiry, from developing relevant research objectives to dissemination of research findings. As an orientation to research that engages the community as full and equitable partners in the research process, CBPR is one promising approach to reducing health disparities (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Minkler, 2010). CBPR has also been shown to be a successful method for addressing sexual health inequity (Rhodes, Malow, & Jolly, 2010). Given that REMs frequently experience several systemic issues (often the result of institutional racism) that can influence sexual inequity, the inclusion of REM community members in research is imperative for accurately identifying and addressing the needs of REM communities. CBPR allows for REM community members to have full participation in accurately identifying their community needs and developing targeted and sustainable interventions.

Specifically, partnering with members of the community who are “insiders” and represent the project’s target population (e.g., have lived experiences) can result in a multitude of benefits, including increased participant engagement, improved understanding of community need, tailored intervention strategies, and increased sustainability (Vaughn et al., 2018). The importance of community partnership is also demonstrated by the International Association for Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation (International Association for Public Participation, 2018). This spectrum highlights that with increased involvement of community members in all phases of the research process, community members become empowered and can significantly impact implementation.

Despite several studies relying on CBPR to research sexual health, to our knowledge, there is only one known review that synthesizes this large breadth of research. Coughlin’s (2016) systematic review summarized the literature on CBPR and HIV/AIDS in articles published between 2005–2014. Through using Medical Subheadings (MeSH) terms, this search (which was not guided by PRISMA guidelines) identified 44 studies that used various methodologies. Coughlin (2016) noted that many of the identified studies represented formative research (70%), with several others demonstrating issues that likely impacted generalizability. The author identified that only 36% of the studies focused on REMs. While these findings are informative, the review had a broad focus which included literature from various types of studies that used CBPR and HIV/AIDS, including formative work. Specific attention to research-based intervention strategies for reducing sexual health inequities among REMs is essential. To our knowledge, there are no other summative studies that identify empirically examined interventions developed using CBPR to address the sexual health disparities among REMs.

Previous research also suggests that involving community members who are culturally representative of the target group in the research can result in improved outcomes (Vaughn et al., 2018). Yet, no coordinated investigation has been undertaken to identify the specific ways in which these target group members are included as partners in sexual health research. Understanding the roles that community members have played in existing CBPR projects could be useful for future research.

The current systematic review aims to address these gaps with the following research objectives: 1) summarize the existing research on sexual health interventions targeting REMs that were developed using CBPR; 2) explore the roles that REMs, as members of the target group, played in the research and; 3) examine the potential benefits and outcomes associated with including members of the target group in sexual health intervention research.

Method

Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) Process

PICO is an evidence-based process for structuring and assessing research questions, executing the search strategy, and synthesizing the results. For the present study, the PICO was as follows: 1) Our identified population of inquiry included REMs due several REM populations having a documented history of sexual health disparities; 2) CBPR was identified as the methodological focus of the interventions; 3) assessing the comparison of intervention methods can be and was thus omitted; and; 4) the outcomes of the interventions and level of involvement of community members were assessed.

Selection of Databases

The research team selected databases based on scholarly foci, breadth, and expert recommendations. CINAHL, Medline/PubMed, and Cochrane served as the sources for publications focused in the health sciences. PsycINFO was used since it is the world’s largest behavioral science repository. Academic Search Complete was selected as it is one of the leading scholarly research databases. Lastly, Embase, Google Scholar and Web of Science Core Collection were used. Along with Medline/PubMed, research suggests these three databases can be used to access approximately 95% of available scholarly research (Bramer et al., 2017).

All the aforementioned databases, except Cochrane and Google Scholar, were searched within the newer iteration of EBSCOhost, an online search platform. The search was conducted in July 2019. The latest version of the platform is amenable to conducting simultaneous searches, eliminating the need for multiple independent database searches. EBSCOhost provides retrievable metadata on each individual database, including selected limiters, and limits duplicate results thereby reducing the number of articles needed to read. EBSCOhost also uses proximity operators to broaden the search beyond the exact phrases entered and includes plural derivatives and word variants using truncations (e.g., Latin* = Latina/Latinas/Latino/Latinos/Latinx).

To reduce the effects of publication bias, some gray literature was examined within Google Scholar and Cochrane in December of 2019. The Google Scholar search yielded over 13,000 returns in order of relevance. As Eiseman (2012) suggested, a review of the top results failed to identify any new or appropriate studies. Cochrane, a clinical trials registry, identified 147 CBPR studies. Nine focused on sexual health but had already been identified in the EBSCOhost search.

Database Limiters

Articles were limited to those published since 2000 to account for the responses to a national call for health research with community partners and the subsequent onslaught of CBPR research (National Institute of Nursing Research, 2003). Returns were limited to intervention studies published in the U.S. and in English.

Identification of Search Terms

Within each database, thesaurus terms (synonyms and related concepts) including subjects and natural language (i.e., bridge between human and computer language) were mapped for the target variables. For example, thesaurus terms for CBPR included participatory action research and community action research. The results were narrowed to relevant terms by consensus and culminated with nine words/phrases for sexual health (e.g., HIV, AIDS sexually transmitted infections [STIs]) and 35 terms for race/ethnicity (e.g., race, immigrant, African Americans). These 46 words/phrases were linked with appropriate operators (i.e., “AND,” “OR”; complete syntax is available upon request).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Filtering

PRISMA is an evidence-based method for reporting and evaluating systematic reviews. In four phases, articles are identified, screened for inclusion/exclusion, full-text reviewed, and then determined eligible or ineligible in a refined screening process. Those remaining are included in a summative synthesis (Liberati et al., 2009). For the present review, when all search terms were included, 805 records were identified.

Title and Abstract Review

A system-generated search of the articles with the identified terms appearing in the title or abstract, with aforementioned limiters, reduced the count to 273 records. EBSCOhost removed numerous duplicate records, resulting in 140 articles retained. The first two primary authors read the titles and abstracts of each. As a result, another 91 articles were either deemed ineligible (i.e., not CBPR, sexual health, on REMs, an intervention study, or in the U.S.) or were duplicates.

Full-Text Review and Data Extraction

After the lead team members reviewed the full-text review of the remaining 50 articles, 26 more articles were excluded that were not interventions or associated with identifiable interventions (i.e., focus groups, survey, etc.). The full research team conducted a summative review of the two dozen remaining articles (see Figure 1 for flow diagram of inclusion/exclusion).

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of search results

Microsoft Excel was used to gather the extracted data (e.g., author(s), publication date). Several studies published separate methodological and outcome papers, which the authors grouped together in the database to minimize duplicate data extraction. In addition to the PICO data extrapolation, the description of “community collaboration” at each phase of the scientific research process was copied. Inclusion at each stage was coded as absent or present and vague descriptions were rated using discussion and consensus.

Results

Summary of Studies

A closer examination of the original 140 unduplicated studies revealed that nearly a third of the studies did not include information specifically on REMs (32.14%) or were not interventions (32.14%). The 22 studies conducted outside of the U.S. were beyond the scope of the present study. Less than one-fifth of the identified studies met the inclusion criteria for this review (n = 24; 17.14%). The retained studies were published between 2004–2018. The studies were numbered to facilitate ease of referencing and are listed in brackets hereafter (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Sexual Health Interventions Targeting Racial/Ethnic Minorities Using CBPR

| Study # | *Author & Year | Name | Population | Locale Type | # of Sessions | Intervention Description | ***CBPR Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | Romero et al. (2006) | Woman to Woman | Minority women engaging in risky sexual behavior | Mixed | 17 | HIV prevention intervention focused on traditional HIV education as well as empowerment within the context of gender, cultural, economic, and inequality. | 1 |

| 2 | Yancey et al. (2012) | HIV-RAAP | Heterosexual African American men and women | Urban | 7 | Weekly two-hour meetings using Afrocentric and gender empowerment to teach HIV knowledge and risk reduction. | 1 |

| 3 | Griffith et al. (2010) | YOUR Blessed Health | African American children and young adults | Urban | -- | Training for adult church/community members to educate youth on HIV awareness and knowledge and reduce HIV risk behavior. | 1 |

| 4 | Moya et al. (2014) | -- | Mexican migrant female survivors of intimate partner violence | Urban | 5 | Photovoice photography for social change as it relates to intimate partner violence. | 1 |

| 5 | Richards et al. (2012) | Sacred Beginnings Project | American Indian adolescent girls | Rural | 15 | Culturally specific intervention on motherhood, womanhood, relationships, and preconception health. | 1 |

| 6 | **Berkley-Patton et al. (2010)/ Berkley-Patton et al. (2016) | Taking It to the Pews | African American adult churchgoers | Urban | 1–2 | Culturally and religiously developed HIV prevention program. | 1 |

| 7 | Sánchez et al. (2013) | Project Salud | Latinx men and women migrant workers | Rural | 4 | Adapted Stage-Enhanced Motivational Interviewing intervention to decrease HIV risk and increase positive health behaviors. | 1 |

| 8 | Dave et al. (2017) | Teach One Reach One | African American parents of adolescents | Rural | 12 | Intervention for adults on parental monitoring and communication about sexual health and healthy relationships with their children. | 1 |

| 9 | Rios-Ellis et al. (2011) | Rompe el Silencio | Latino family dyads | Urban | 2 | Intervention for mothers and daughters on values around sex, sexual health education, and risk reduction. | 2 |

| 10 | Marcus et al. (2004) | Project BRIDGE | African American adolescents | Urban | -- | Long-term intervention for substance use prevention, abstinence based sexual health, and peer education with a faith component. | 2 |

| 11 | **Tanner et al. (2018)/Tanner et al. (2016) | weCare | Racially diverse men who have sex with men living with HIV | -- | Individualized, theoretically founded social media-based intervention to reduce barriers to HIV treatment access and retention. | 2 | |

| 12 | Juzang et al. (2017) | 411 for Safe Text | African American men | Urban | 36 | Text message campaign with quizzes on HIV prevention. | 2 |

| 13 | **Wilson et al. (2019)/Gousse et al. (2018) | Barbershop talk w/ brothers | Heterosexual African American men | Urban | 1 | Modules on community responsibility and motivation to engage in health promotion, HIV education and condom education and dissemination within personal networks. | 3 |

| 14 | Hergenrather et al. (2013) | Hope Intervention | African American gay men living with HIV/AIDS | Urban | 7 | Intervention guided by social learning and hope theories focused on exploring and obtaining employment as well as self-management of HIV. | 3 |

| 15 | **Solorio et al. (2014)/ Solorio et al. (2016) | Tu Amigo Pepe | Latino MSM | Urban | -- | Social marketing campaign on HIV prevention using Spanish language radio public service announcements, a website, social media, printed materials and mobile communication. | 3 |

| 16 | Rios-Ellis et al. (2010) | Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba | Spanish speaking Latinx men and women | Urban | -- | Interactive training on cultural values and traditions that promote healthy families and communities, communication about sexual health, and HIV risk-related information. | 3 |

| 17 | McKay et al. (2014) | CHAMP+ | Family dyads of youth living with HIV and their caregiver | Urban | 10 | Family program covering topics such as impact of health and social aspects of HIV as well as parental supervision of sexual risk taking. | 3 |

| 18 | **Madison et al. (2000)/ McKay et al. (2004)/ McBride et al. (2007) | CHAMP | African American youth | Urban | 12 | Developmentally timed intervention that includes information on family processes, family communication, social support, parental supervision and monitoring, child assertiveness and social problem solving related to HIV prevention. | 3 |

| 19 | Rhodes et al. (2011) | HoMBReS-2 (Men-2: Men Maintaining Wellbeing and Healthy Relationships-2) | Heterosexual immigrant Latino adult men | Rural | 4 | Interactive, small group, peer led HIV prevention program | 3 |

| 20 | Rhodes et al. (2017) | HOLA | Latino immigrant sexual minority men and transgender individuals | Urban | 4 | Culturally relevant, theoretically grounded intervention with modules on HIV education, condom negotiation and use, influence of cultural values and sexual health. | 3 |

| 21 | Aronson et al. (2013) | Brothers Leading Healthy Lives | African American male college students | -- | 5 | Weekend retreat on masculinity, HIV education, intimate relationships, communication, and peer advocacy. | 3 |

| 22 | Wilkinson-Lee et al. (2018) | -- | Latina women | -- | 3 | Individual participant contacts from a trained community partner delivering a culturally-based intervention focused on sexually transmitted infection and depression education. | 3 |

| 23 | Rink et al. (2016) | Unzip the Truth | American Indian men residing on a reservation | Rural | 3 | Peer based intervention on pregnancy, HIV/STI attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors | 3 |

| 24 | DeMarco et al. (2013) | Sistah Powah | HIV positive African American women | Urban | 4 | Writing intervention focused on adherence, stigma, and self-advocacy outcomes. | 3 |

Note.

Abbreviated author list provided.

Additional method or outcome paper identified. See References for details.

CBPR level assigned: = Level 1: REM serving community agencies were the CBPR partners; 2 = Level 2: REM were involved in CBPR project, but specific role was not described and; 3 = Level 3: REM were directly involved in CBPR project and their roles are clearly described.

Objective 1: Summarizing Research on Interventions Developed Using CBPR

Study Populations

The mean sample size was robust with 261 participants (range = 7 – 1,187). Most studies were conducted in urban settings (n = 15; 62.5%). Ten studies included both males and females, whereas separately males were the target participants in nine studies and females were the focus in five studies. All the studies had racial/ethnic minority samples greater than 89%, with the vast majority at 100% representation (n = 21; 87.5%). African Americans/Blacks were represented in 50% of the retained studies [3, 6, 8, 10, 12–14, 17–18, 21, 24] followed by Latinx (referred to as Latino or Hispanic in several of the studies; n = 8; [4, 7, 9, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22]), American Indian (n = 2; [5, 23]), and mixed samples (n = 2; [2, 17]). Adults were the sole focus in most of the studies (n = 16; 66.6%) with five studies including adolescents/youth [3, 5, 10, 17–18]. Three interventions included family dyads [8, 9, 17]. Four studies included gay (n = 3; [11, 14, 15]) and transgender (n = 1; [20]) participants. Finally, there were four interventions with participants who had HIV [11, 14, 17, 24].

Intervention Methodologies

The strategies used by the 24 different interventions to address the sexual health needs of their respective target groups varied. Several studies relied on a behavioral intervention. The sessions (ranging from 1–17) occurred either individually or in a group setting. Other interventions utilized unique approaches, including a social marketing campaign [15], a social media intervention [11], and a text-based intervention [12].

Most of the studies focused on HIV prevention (75%; n = 18). Four studies (16.6%) targeted sexual health more generally, including reproductive health and safer sex practices [5, 8, 12, 24]. One study targeted increased communication about sex among family members [8]. Another study targeted intimate partner violence [4].

Summary of Outcomes

Outcomes of the interventions varied significantly; however, all studies provided results related to changes in thoughts, attitudes, and/or behavior change. A third of the studies reported significant outcomes regarding changing participants’ thoughts such as improved HIV or STI knowledge [16, 18, 20, 21, 22]. Of the 24 studies, 37.5% reported a significant impact on individual’s attitudes. For example, numerous studies reported improved condom use self-efficacy or communication capacity regarding sex [14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 23]. Finally, 79% of the studies reported significant changes in behavior, including increased condom use [19, 20, 21, 24], decreased condomless sex [13, 21], and decreased number of sexual partners [21].

Objective 2: Explore Role of Target Group Members

To understand how community members, who are typically the targeted participants in intervention research, were involved as partners in these CBPR projects, we investigated their role in each study and assigned them progressively inclusive ascending levels (1–3; see Table 1). In Level 1 studies [1–8], REMs-serving community agencies were the partners and not necessarily members of the target group. One third of the studies (identified as Level 1; n=8) worked with leaders from community-serving organizations rather than with individuals from the target population. This distinction is commonly known as grass tops (i.e., leaders and decision-makers) versus grassroot (i.e., community members) partnerships. For example, researchers in New Mexico partnered with Planned Parenthood staff to deliver an HIV prevention program with strong empowerment components in the curriculum (Romero et al., 2006). For Level 2 [9–12], REMs were involved but details of the role of target members were not provided or were unclear (n = 4; 16%). For example, Project BRIDGE is a faith-based/academic partnership targeting middle school African American adolescents (Marcus et al., 2004). The authors mention having a youth coalition but go on to describe the inclusion of a pastor with oversight of youth rather than specific inclusion of African American adolescents or, if present, the details of their involvement. Lastly, Level 3 studies [13–24] included members of the target group and clearly delineated their role (n = 12; 50%).

The role that community members played in Level 3 studies was further analyzed. Based on previous research (Jacquez, Vaughn, & Wagner, 2013), we created six non-mutually exclusive categories to describe target group member involvement in stages of the research process (see Table 2). These categories included: 1) preliminary research design, 2) choosing/developing data collection methods or instruments, 3) recruitment, 4) facilitating the intervention, 5) data collection, and 6) data analysis/interpretation.

Table 2.

Level of Community involvement in 12 Interventions Developed in Partnership with Target Group Members

| Intervention | Authors | Community Partners and Target Group Members | Phases of Community Involvement | Degree of Collaboration | Key Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 13 Barbershop Talk with Brothers | Wilson et al. (2019) | Community-based organizations (CBO) and a board consisting of barbers, barbershop owners and managers, and one target group member | + | + | + | + | Moderate | Higher percent of no condomless sex at 6-month follow up. | ||

| 14 Hope Intervention | Hergenrather et al. (2013) | Members of the CBO serving people living with HIV/AIDS. Team of target group members, including African American gay men living with HIV/AIDS | + | + | Low | Improved HIV treatment and medication adherence. Improved ability to communicate with treatment provider. | ||||

| 15 Tu Amigo Pepe | Solorio et al. (2016) | CBO serving the Latino LGBT community and Latino MSM | + | Low | Increased HIV testing rates, intention, attitudes, and self-efficacy toward testing. Improved attitudes and beliefs about condom use. | |||||

| 16 Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba | Rios-Ellis et al. (2010) | Two CBO’s as well as HIV+ peer health educators from the Latino community | + | + | + | + | + | High | Increased condom use and refusal of unsafe sex. Improved HIV knowledge, intention for safer sex and HIV testing. | |

| 17 CHAMP+ | McKay et al. (2014) | Pediatric HIV primary care staff and HIV-positive youth and their adult caregivers | + | + | Low | Marginal increases in treatment knowledge and caregiver being involved in medication adherence. | ||||

| 18 CHAMP | McKay et al. (2004) | Parents, students, school staff, and a community mental health center staff member | + | + | + | Moderate | Increased HIV knowledge and comfort discussing sensitive topics. | |||

| 19 HoMBReS-2 | Rhodes et al. (2011) | Local health and Latino-serving CBOs, religious organizations, and several Latino community members | + | + | + | + | + | High | Significantly more likely to get tested for HIV and use condoms regularly. | |

| 20 HOLA | Rhodes et al. (2017) | Local health and Latino-serving CBOs and Latino MSM | + | + | + | + | + | + | *High | Consistent condom use and HIV testing. |

| 21 Brothers Leading Healthy Lives | Aronson et al. (2013) | African American college students, university faculty and staff, and community partners involved in HIV prevention | + | + | + | + | + | High | Decreased number of sexual partners and unprotected sex, increased condom use, and increased HIV knowledge and condom use intention. | |

| 22 Intervention not named | Wilkinson-Lee et al. (2018) | CBOs, community health centers, neighborhood associations, and community volunteers | + | + | + | + | + | High | Increased STI knowledge and screening. | |

| 23 Unzip the Truth | Rink et al. (2016) | Health department staff members and tribal residents | + | + | + | + | + | + | *High | Increased sexual health knowledge and positive attitudes towards contraceptives (not significant). |

| 24 Sistah Powah | DeMarco et al. (2013) | Black women with HIV | + | + | Low | Increased condom use and safer sex practices. | ||||

Note. Roles of community members are as follows: 1 – Design of protocol and study set up; 2 – Choosing/developing data collection methods or instruments; 3 – Recruitment; 4 – Facilitation of intervention; 5 – Data collection; 6 – Data analysis and interpretation. Degree indicates that target members were included in 1–2 aspects of the intervention (Low), 3–4 (Moderate), or 5–6 (High).

Indicates studies with full participation.

All twelve Level 3 studies described target group member collaboration in the preliminary design stages of the research process, including creating study protocols and choosing design strategies. Community partners were involved in development of data collection tools in half of Level 3 studies (n = 6 [16, 19–23]). Target group members were also commonly included in recruitment of participants (n = 7 [13, 16, 19–23]) and facilitating or implementing the intervention (n = 8; 66.7% [13, 16, 19–24). Members of the target group were involved in data collection efforts in more than half of the studies (n = 7 [13, 16, 18–20, 22,23]), and half of the studies reported target group member involvement in data analysis/interpretation (n = 6 [14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23]).

Studies that reported collaboration with members of the target community in 1–2 aspects of the project were labeled low collaboration (n = 4; 33.3% [14, 15, 17, 24]. Those with 3–4 areas of collaboration were labeled medium (n = 2; 16.6% [13, 18]) and inclusion in 5–6 aspects are labeled high collaboration research partnerships (n = 6; 50% [16, 19–23]). Two of these studies reported full participation of target group members. The key outcomes of these studies are also described in Table 2.

Example of Full Target Group Member Collaboration (Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba)

Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba is an example of full community engagement throughout the entire project (Rios-Ellis et al., 2010).The aim of the project was to develop a culturally appropriate intervention to increase HIV awareness and testing, reduce risky sexual behaviors, and decrease HIV stigma among Spanish speaking Latinx men and women. The community representatives included promotores (peer health educators) and three bicultural female group facilitators. During the formative stage, the female group facilitators conducted four family-based, mixed group focus groups. In the intervention stage, the promotores collaborated with the University staff to utilize the information gained from the focus groups to create a tailored curriculum and an instructional manual. During the implementation stage, both promotores and University staff recruited new participants and delivered the one-time, two-hour intervention. The sample included 461 adults in 27 charlas (i.e., groups) who were either US born or foreign-born Latinos. Finally, in the evaluation stage, the promotores who had co-developed the assessment materials with the University staff participated in training in basic evaluation methods in order to conduct the pre- and post-test telephone surveys and to evaluate the findings. The findings demonstrated not only the efficacy of the intervention in increasing HIV knowledge and improving intent for behaviors such as HIV testing, but also the feasibility and value-added of involving the community throughout the project. The authors suggested that the community involvement resulted in a more linguistically and culturally appropriate intervention that holds promise for reducing sexual health inequity (Rios-Ellis et al., 2010).

Objective 3: Potential Benefits/Outcomes of Partnering with Target Group Members

The third objective of this review was to explore potential benefits related to engaging in CBPR with target group members. Twelve of the identified studies described target group members as research partners and clearly outlined the role these members played in several aspects of the study. While each study targeted different sexual health concerns among several REMs, the reported outcomes are promising for reducing sexual health disparities. The studies reported significant outcomes such as decreased sexual risk taking (e.g., increased condom use), increased engagement in HIV prevention behaviors (e.g., increased medication adherence and HIV testing), attitude change (e.g., increased condom use self-efficacy or intention), and increased communication with sexual partners (e.g., discussing safer sex).

In addition to the reported outcomes related to sexual health, several studies highlighted benefits of partnering with target group members. Multiple studies attributed successful recruitment and retention to the partnership with community members (Aronson et al., 2013; DeMarco & Chan, 2013; McBride et al., 2007; Rhodes et al., 2017). Other studies highlighted that community partnership likely resulted in more culturally relevant interventions (Rios-Ellis et al., 2010; McBride et al., 2007). Wilson and colleagues (2019) found that target group members who participated in the partnership experienced more self-efficacy to serve as community advocates. Hergenrather Geishecker, Clark, and Rhodes (2013) suggested that the cohesiveness of a 10-year partnership likely contributed to significant intervention outcomes. Rink and colleagues (2013) highlighted the potential limitations of using academically developed theoretical approaches to research with REM communities. Results from their project suggested the utility of a more indigenous theoretical approach that was aligned with the culture of their community partners. Thus, the invaluable benefits of academic community partnerships on sexual health of REMs is evident.

Discussion

CBPR is a research orientation that encourages collaboration and shared decision making across community and academic partnerships and can often result in more culturally relevant outcomes (Jacquez, Vaughn, & Wagner 2013). Given their unique experience with sexual health inequity, REMs may benefit more from intervention strategies that are culturally adapted or tailored (Burlew, Copeland, Ahuama-Jonas, & Calsyn, 2013; Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti, & Stice, 2016). Collaboration with target group members is one method for developing these culturally tailored interventions (Vaughn et al., 2018). Without involvement of target group members, it may be difficult to understand the nuanced experiences that REMs often face related to sexual health.

The present review assessed 24 sexual health interventions for REMs developed with a CBPR orientation, examined the role of target group members, and summarized some of the major findings. Great variability existed in the target populations and reported intervention outcomes, which impeded conducting a meta-analysis. Although most studies focused on behavioral change for HIV risk reduction, several appeared to mirror a biopsychosocial model of health by also focusing on other social contexts (e.g., familial communication or cultural values) that can also influence health behaviors(Engel, 1977), particularly among REMs. Overall, 79% of the studies reported significant changes in sexual risk behaviors, which is a salient step for reducing sexual health inequity. While many of studies utilized more traditional behavioral interventions, several employed novel strategies for engaging populations who may experience stigma related to sexual health including REM men who have sex with men (Tanner et al., 2018; Solorio et al., 2016) or Black youth (Juzang, Fortune, Black, Wright, & Bull, 2011).

These findings suggest that while intervention methodology may vary, interventions developed using CBPR hold promise for reducing sexual health inequity for REMs. Many of the interventions developed with target group members partially attributed their significant outcomes to the collaboration with community members. This is particularly important, given that REMs are often underrepresented in research (Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006).

This review illuminated substantial variability within the studies regarding the description of CBPR and community partnership. Of the 273 original articles identified, 91 were eliminated at the abstract review due to lack of any provided details on community partnership. Of the 24 retained studies, half of the studies either did not identify how community members were involved or reported partnership with community-based organizations only. In the other 12 studies, target group member collaboration was split equally between low/moderate and high levels of collaboration. However, only two studies reported target group members participating in all aspects of the research, which could be indicative of shared decision-making and power throughout the research process (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). While it is not assumed that manuscripts with a dearth of this information did not collaborate with community members, the lack of provided detail on such collaboration when reporting use of CBPR could be considered as a concerning finding, given that collaboration is a core tenant of the CBPR orientation. It is noteworthy that including community partners throughout the research process may not always be feasible (e.g., attrition) but should always be meaningful (e.g., utility of participating in technical activities).

While the identified studies demonstrated important outcomes, they were not without limitations. Collaboration with the target group members was often presented with variable detail across the 24 studies, making it difficult to consistently determine the exact role target group members played. At times, the authors of the current review had to search and consult additional methodological papers to gain more information about how community members were involved. It is not presumed that all articles that do not describe the community/academic partnership in detail were not engaging in CBPR; however, the lack of description does impede analysis and replicability in future research.

While several of the studies mentioned a seemingly meaningful outcome of including target group members, none presented empirical findings of how community member collaboration improved the intervention. Future studies should work to measure the impact of community collaboration on study findings. For example, documenting change in target group members’ interest in being advocates for their communities or serving on future research teams.

This review itself also has some limitations. Although this search was comprehensive, using other research databases may have resulted in additional articles being identified. It is possible that additional ‘gray literature’ could have enhanced the picture of the available manuscripts, especially since some of this research could be completed outside of the academic setting. However, by relying on published research, the peer-review process contributes to a certain level of consistency which allows for a systematic review. The authors could have also been biased in applying inclusion/exclusion criteria and study level. However, all team members discussed all ambiguous information as a full team and came to a verbal consensus on decisions regarding retainment of studies or assignment of study level during regular team meetings. Moreover, there may be other methods to classify inclusion of target group members that were not utilized within this review.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study has several strengths. The search process was conducted in a way to permit replication (syntax available upon request). Building upon previous literature (Coughlin, 2016), this review addressed a gap by summarizing empirically-examined interventions developed using CBPR for addressing sexual health disparities for REMs. Additionally, it highlights the benefit of CBPR and target group member involvement in health inequities research. By outlining where in the research process target group members are more often involved, this review could provide a roadmap for future community/academic partnerships to engage in collaborative work. Based on our findings that all 24 reviewed manuscripts reported significant changes on thoughts, attitudes, or behaviors related to sexual health inequity, it can also be hypothesized that involvement of target group members is an effective strategy. Thus, this review could hold clinical implication, as it serves as a summary of interventions that could be appropriate for REM communities impacted by sexual health inequity.

This project is the first comprehensive investigation of CBPR sexual health interventions targeting REMs. The study outcomes provide informative targets and methodology for future interventions. The studies demonstrated that successful community collaborations can have a strong effect. More broadly, research is needed to measure the specific dimensions of this influence. The methods used for this review may be utilized to assess CBPR interventions around the world, with special attention being given to other communities uniquely impacted by sexual health disparities (e.g., LGBTQ communities, individuals who use substances, etc.). Our findings also provide important insights into the limited disclosure of true CBPR practices and the variability in collaboration with target group members, despite knowledge that increased collaboration in all phases of the research can be empowering for community members (International Association for Public Participation, 2018). Researchers should make a targeted effort to report specific details on the roles played by community members, which could be important for replication. Journal editors should also be invested in publishing manuscripts that provide such detail. Greater efforts are needed to ensure not only full, but equitable partnerships with target group members to develop effective, culturally relevant interventions. Continued work on CBPR and sexual health will have a meaningful impact in reducing the sexual health inequities among REMs.

Contributor Information

Caravella McCuistian, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Bridgette Peteet, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Kathy Burlew, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Farrah Jacquez, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA..

References

- Aronson RE, Rulison KL, Graham LF, Pulliam RM, McGee WL, Labban JD, ... Rhodes SD (2013). Brothers leading healthy lives: Outcomes from the pilot testing of a culturally and contextually congruent HIV prevention intervention for black male college students. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(5), 376–393. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley-Patton J, Bowe-Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A, Hawes S, Moore E, Williams E, ... & Goggin K (2010). Taking it to the pews: A CBPR-guided HIV awareness and screening project with black churches. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(3), 218–237. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Moore E, Hawes S, Simon S, Goggin K, … Booker A (2016). An HIV Testing Intervention in African American Churches: Pilot Study Findings. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 50(3), 480–485. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9758-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, & Franco OH (2017). Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Systematic Reviews, 6(245) 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Copeland VC, Ahuama-Jonas C, & Calsyn DA (2013). Does cultural adaptation have a role in substance abuse treatment?. Social Work in Public Health, 28, 440–460. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2013.774811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2018). STDS in Racial and Ethnic Minorities. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/minorities.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2019). CDC Data Confirm: Progress in HIV Prevention has Stalled. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/0227-hiv-prevention-stalled.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020a). HIV and African Americans. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020b). HIV and Hispanics/Latinos. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispaniclatinos/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020c). STD Health Equity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/health-disparities/default.htm#ftn6

- Coughlin SS (2016). Community-based participatory research studies on HIV/AIDS prevention, 2005–2014. Jacobs Journal of Community Medicine, 2(1), 1–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave G, Ritchwood T, Young TL, Isler MR, Black A, Akers AY, ... & Stith D (2017). Evaluating teach one reach one—an STI/HIV risk-reduction intervention to enhance adult–youth communication about sex and reduce the burden of HIV/STI. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(6), 465–475. doi: 10.1177/0890117116669402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, & Steinauer J (2010). Disparities in family planning. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(3), 214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco RF, & Chan K (2013). The Sistah Powah structured writing intervention: a feasibility study for aging, low-income, HIV-positive black women. American Journal of Health Promotion, 28(2), 108–118. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120227-QUAN-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiseman J (2012, November 6). Google Scholar Searching: 10 Ways to Avoid Retrieving Millions of Hits. Retrieved April 2, 2020, from https://library.law.yale.edu/news/google-scholar-searching-10-ways-avoid-retrieving-millions-hits

- Engel G (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science., 196:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousse Y, McFarlane D, Fraser M, Joseph M, Alli B, Council-George M, ... & Stewart M (2018). Lessons Learned from the Implementation of a Shared Community-Academic HIV Prevention Intervention. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 12(4), 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Pichon LC, Campbell B, & Allen JO (2010). YOUR Blessed Health: A faith-based CBPR approach to addressing HIV/AIDS among African Americans. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(3), 203–217. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, Marti CN, & Stice E (2016). A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 993–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Service Administration (2019). Office of Health Equity. Retrieved from https://www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/bureaus/ohe/index.html

- Hergenrather KC, Geishecker S, Clark G, & Rhodes SD (2013). A pilot test of the HOPE Intervention to explore employment and mental health among African American gay men living with HIV/AIDS: Results from a CBPR study. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(5), 405–422. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogben M, & Leichliter JS (2008). Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 35(12), S13–S18. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3cad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Public Participation (2018). IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. Retrieved from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5×11_Print.pdf

- Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, & Wagner E (2013). Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: A review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR). American Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 176–189. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9533-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juzang I, Fortune T, Black S, Wright E, & Bull S (2011). A pilot programme using mobile phones for HIV prevention. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17(3), 150–153. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SC, Tandon SD, Islam N, Riley L, & Trinh-Shevrin C (2018). Applying a community-based participatory research framework to patient and family engagement in the development of patient-centered outcomes research and practice. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8(5), 683–691. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, ... & Moher D (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W-65-W-94. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison SM, McKay MM, Paikoff R, & Bell CC (2000). Basic research and community collaboration: Necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based HIV prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention, 12(4), 281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus M, Walker T, Swint JM, Smith BP, Brown C, Busen N, ... & von Sternberg K (2004). Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African-American adolescents. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 18(4), 347–359. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CK, Baptiste D, Traube D, Paikoff RL, Madison-Boyd S, Coleman D, ... & McKay MM (2007). Family-based HIV preventive intervention: child level results from the CHAMP family program. Social Work in Mental Health, 5(1–2), 203–220. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Chasse KT, Paikoff R, McKinney LD, Baptiste D, Coleman D, ... & Bell CC (2004). Family‐level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Family Process, 43(1), 79–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Alicea S, Elwyn L, McClain ZR, Parker G, Small LA, & Mellins CA (2014). The development and implementation of theory-driven programs capable of addressing poverty-impacted children’s health, mental health, and prevention needs: CHAMP and CHAMP+, evidence-informed, family-based interventions to address HIV risk and care. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 428–441. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M (2010). Linking science and policy through community-based participatory research to study and address health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100(S1), S81–S87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya EM, Chávez-Baray S, & Martinez O (2014). Intimate partner violence and sexual health: voices and images of Latina immigrant survivors in southwestern United States. Health Promotion Practice, 15(6), 881–893. doi: 10.1177/1524839914532651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselwhite LW, Oliveira CM, Kwaramba T, de Paula Pantano N, Smith JS, Fregnani JH, ... & Longatto-Filho A (2016). Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytologica, 60, 518–526. doi: 10.1159/000452240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Nursing Research. (2003, April). Community-partnered interventions to reduce health disparities. Retrieved from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-02–134.html.

- Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Song EY, Tanner AE, Arellano JE, ... & Painter TM (2017). Small-group randomized controlled trial to increase condom use and HIV testing among Hispanic/Latino gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 107(6), 969–976. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montaño J, Remnitz IM, & al, e. (2006). Using Community-based Participatory Research To Develop An Intervention To Reduce HIV And STD Infections Among Latino Men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(5), 375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, McCoy TP, Vissman AT, DiClemente RJ, Duck S, Hergenrather KC, … Eng E (2011). A randomized controlled trial of a culturally congruent intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexually active immigrant Latino men. AIDS and Behavior, 15(8), 1764–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9903-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Malow RM, & Jolly C (2010). Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(3), 173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, & Mousseau A (2012). Community-based participatory research to improve preconception health among Northern Plains American Indian adolescent women. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. The Journal of the National Center, 19(1), 154–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink E, Ricker A, FourStar K, & Anastario M (2016). Unzip the Truth: Results from the Fort Peck Men’s Sexual Health Intervention and Evaluation Study. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(4), 306–330. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2016.1231649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rios-Ellis B, Espinoza L, Bird M, Garcia M, D’Anna LH, Bellamy L, & Scolari R (2010). Increasing HIV-related knowledge, communication, and testing intentions among Latinos: Protege tu Familia: Hazte la Prueba. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 148–168. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios-Ellis B, Canjura AC, Garcia M, & Bird (2011). Rompe el silencio (break the silence)-increasing sexual communication in Latina intergenerational family dyads. Hispanic Health Care International, 9(4), 174–185. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.9.4.174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Wallerstein N, Lucero J, Fredine HG, Keefe J, & O’Connell J (2006). Woman to woman: coming together for positive change—using empowerment and popular education to prevent HIV in women. AIDS Education & Prevention, 18(5), 390–405. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez J, De La Rosa M, & Serna CA (2013). Project Salud: Efficacy of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for Hispanic migrant workers in South Florida. AIDS Education and Prevention, 25(5), 363–375. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.5.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, Martinez M, & Aguirre J (2014). HIV Prevention Messages Targeting Young Latino Immigrant MSM. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2014 (353092), 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2014/353092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, Montaño D, Stern J, Aguirre J, & Martinez M (2016). Tu Amigo Pepe: Evaluation of a multi-media marketing campaign that targets young Latino immigrant MSM with HIV testing messages. AIDS and Behavior, 20(9), 1973–1988. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthers K (2008). Evaluating the economic causes and consequences of racial and ethnic health disparities. Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/∼/media/files/pdf/factsheets/corrected_econ_disparities_final2.ashx

- Tanner AE, Mann L, Song E, Alonzo J, Schafer K, Arellano E, … Rhodes SD (2016). weCARE: A Social Media-Based Intervention Designed to Increase HIV Care Linkage, Retention, and Health Outcomes for Racially and Ethnically Diverse Young MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention, 28(3), 216–230. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.3.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner AE, Song EY, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, Schafer K, Ware S, ... & Rhodes SD (2018). Preliminary impact of the weCare social media intervention to support health for young men who have sex with men and transgender women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(11), 450–458. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn LM, Whetstone C, Boards A, Busch MD, Magnusson M, & Määttä S (2018). Partnering with insiders: A review of peer models across community‐engaged research, education and social care. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(6), 769–786. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2019). Sexual and Reproductive Health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/

- Wallerstein NB, & Duran B (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100(S1), S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson-Lee AM, Armenta AM, Leybas Nuño V, Moore-Monroy M, Hopkins A, & Garcia FA (2018). Engaging promotora-led community-based participatory research: An introduction to a crossover design focusing on reproductive and mental health needs of a Latina community. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(4), 291–303. doi: 10.1037/lat0000119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Gousse Y, Joseph MA, Browne RC, Camilien B, McFarlane D, ... & Johnson S (2019). HIV Prevention for Black Heterosexual Men: The Barbershop Talk with Brothers Cluster Randomized Trial. American Journal of Public Health, 109,(8), 1131–1137. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, & Kumanyika SK (2006). Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey EM, Mayberry R, Armstrong-Mensah E, Collins D, Goodin L, Cureton S, ... & Yuan K (2012). The community-based participatory intervention effect of “HIV-RAAP”. American Journal of Health Behavior, 36(4), 555–568. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.4.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]