Abstract

Striatal medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs) output through two diverging circuits, the “direct and indirect pathways” which originate from minimally overlapping populations of MSNs expressing either the dopamine receptor D1 or the dopamine receptor D2, respectively. One modern theory of direct and indirect pathway function proposes that activation of direct pathway MSNs facilitates the output of desired motor programs, while activation of indirect pathway MSNs inhibits competing motor programs. A separate theory suggests that coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements. These hypotheses are made testable by a common type of striatal GABAergic projection neuron known as type IIb MSNs. Clusters of these MSNs exhibit phasic increases in firing rate (FR) related to the sensorimotor activity of single body parts. If these MSNs were found to reside only in the direct pathway, it would provide evidence that D1 MSNs are “motor program” specific, which would lend credence to the “competing motor programs” hypothesis. However, if both D1 and D2 MSNs may be type IIb, evidence would be provided for the “coordinated timing or synchrony” hypothesis. Given the substantial anatomical differences between D1 and D2 MSNs, as well as the functional differences proposed by the “competing motor programs” hypothesis, it was predicted that D1 and D2 neurons would process body part stimulation differently. However, type IIb neurons may express either D1 or D2. This evidence, combined with a number of other recent studies, supports the theory that the coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements. We also propose an updated version of this model in which the direct and indirect pathways act as a differentiator circuit. This model provides a possible mechanism by which coordinated activity of D1 and D2 neurons may output meaningful somatosensorimotor information to downstream structures.

Keywords: Direct and indirect pathways, Optogenetics, Single-Unit, Basal Ganglia, Striatum, Type IIb, Somatosensorimotor

Introduction

Dorsolateral Striatum (DLS) medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs) output through two diverging circuits, the “direct and indirect pathways” which originate from minimally overlapping populations of MSNs expressing either the dopamine receptor D1 or the dopamine receptor D2, respectively. Direct (D1) pathway MSNs project preferentially to the globus pallidus internal segment (GPi)/ substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), while indirect (D2) MSNs project to the globus pallidus external segment (GPe). Activity of direct-pathway MSNs was originally presumed to facilitate movement, whereas activity of indirect pathway MSNs was presumed to inhibit movement, though historically these functional properties proved difficult to test. Recent advances in genetic neuroscience toolkits allow for the monitoring and manipulation of direct- and indirect-pathway MSNs in behaving animals. In a first of its kind study, it was shown that, as presumed, activation large populations of striatal D1 MSNs increased movement, i.e., locomotion, while activation of large populations of striatal D2 MSNs decreased locomotion (Kravitz et. al., 2010). However, multiple recent observations have challenged this classical view of basal ganglia function. For example, the first study to record the activity of each pathway during movement found concurrent activation of MSNs from both pathways in one hemisphere during contraversive movements (Cui et al., 2013).

One modern theory proposes that activation of direct pathway MSNs facilitates the output of desired motor programs, while activation of indirect pathway MSNs inhibits competing motor programs (Mink, 2003; Nambu, 2000; Friend and Kravitz, 2014). A separate theory suggests that coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements (Chan et al., 2005; Brown, 2007). Both theories accommodate evidence showing that both D1 and D2 MSNs are active during actions and both neuronal types are sensitive to somatosensory stimulation (Cui et al., 2013; Silberberg et al., 2014). Further, earlier optogenetic findings are not inconsistent with these models, as non-selective global activation of a large population of D2 MSNs could lead to bradykinesia by inhibiting motor programs or desynchronizing striatal MSNs.

A feature of the “competing motor programs” hypothesis is that for every desired motor program, there would be a large number of possible competing motor programs. A logical consequence of this theory is that direct pathway neurons associated with a particular motor program would have to be active during that specific motor program, while indirect pathway MSNs would be active during all actions other than their related motor program. This hypothesis is made testable by a common type of striatal GABAergic projection neuron known as type IIb MSNs (Kimura, 1990). These neurons receive patchy, convergent monosynaptic excitatory input from primary somatosensory (S1) and motor (M1) cortices (Kunzle, 1975; 1977; McGeorge and Faull, 1989; Flaherty and Graybiel, 1993; Hattox and Nelson, 2007; Tai and Kromer, 2014). As a consequence, clusters of these MSNs exhibit phasic increases in firing rate (FR) related specifically to the sensorimotor activity of single body parts (Liles, 1979; Crutcher and Delong, 1984; Alexander and Delong, 1985; McGeorge and Faull, 1989; Cho and West, 1997; Coffey et al., 2016). It is known that about 50% of striatal MSNs in rodents are type IIb (Cho and West, 1997; Coffey et al., 2016). If these MSNs were found to reside only in the direct pathway, evidence would be provided that D1 MSNs are highly specific, which would lend credence to the “competing motor programs” hypothesis. However, if both D1 and D2 MSNs are type IIb neurons that increase firing only during specific “motor programs”, evidence would be provided for the “coordinated timing or synchrony” hypothesis.

As an initial step toward testing this hypothesis, we demonstrated for the first time that type IIb neurons can be discriminated in the DLS of freely moving mice (Coffey et al., 2016). In the present study, we optogenetically identified MSNs in the DLS of freely moving D1-Cre or D2-Cre mice to determine if neurons reside in the direct or indirect pathway. Then, we employed a standard somatosensorimotor exam to determine if the neurons were type IIb. Using these two techniques, we were able to determine unambiguously if a neuron expressed D1 or D2 and if type IIb neurons reside in the direct and/or indirect pathways.

Methods

Subjects

Adult mice (N = 15) were used in this study. Five wild type C57/BL6 mice were used as optogenetics controls, and helped us determine the validity of body exams in the mouse. Two strains of transgenic cre-driver mice were used in order to facilitate optogenetic identification of D1 and D2 expressing neurons. Breeding pairs of D1-Cre [B6.Cg-Tg(Drd1-Cre)262Gsat/Mmcd] and Drd2-Cre [B6.FVB(Cg)-Tg(Drd2-Cre)ER44Gsat/Mmcd] were purchased from the UC Davis Mutant Mouse Research and Resource Center (MMRRC, Davis, CA), and back bred to C57/BL6 in order to produce heterozygous D1-Cre and D2-Cre animals for experimentation. Five D1-Cre and 5 D2-Cre animals were utilized in this study. The following Protocols were performed in compliance with the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publication 865–23) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Rutgers University.

Viral Vector

An adeno-associated virus (AAV-EF1a-FLEx-Chronos-GFP; UNC Vector Core, Chapel Hill, NC) was used to express a light sensitive cation channel (Chronos-GFP) in the presence of Cre (Klapoetke et al., 2014). This is achieved by FLEX recombination of the transgene, which changes the orientation of the coding sequence with respect to the promoter such that the protein may be expressed. In the present animals, the Cre enzyme was selectively expressed in either D1 or D2 expressing neurons. Accordingly, Chronos-GFP expression was limited to those neurons. Chronos-GFP could only express in D1 neurons in a D1-Cre animal and in D2 neurons in a D2-Cre animal. To limit spatial spread of Chronos-GFP, the AAV was intra-cranially microinjected into the DLS (Fig. 1a).

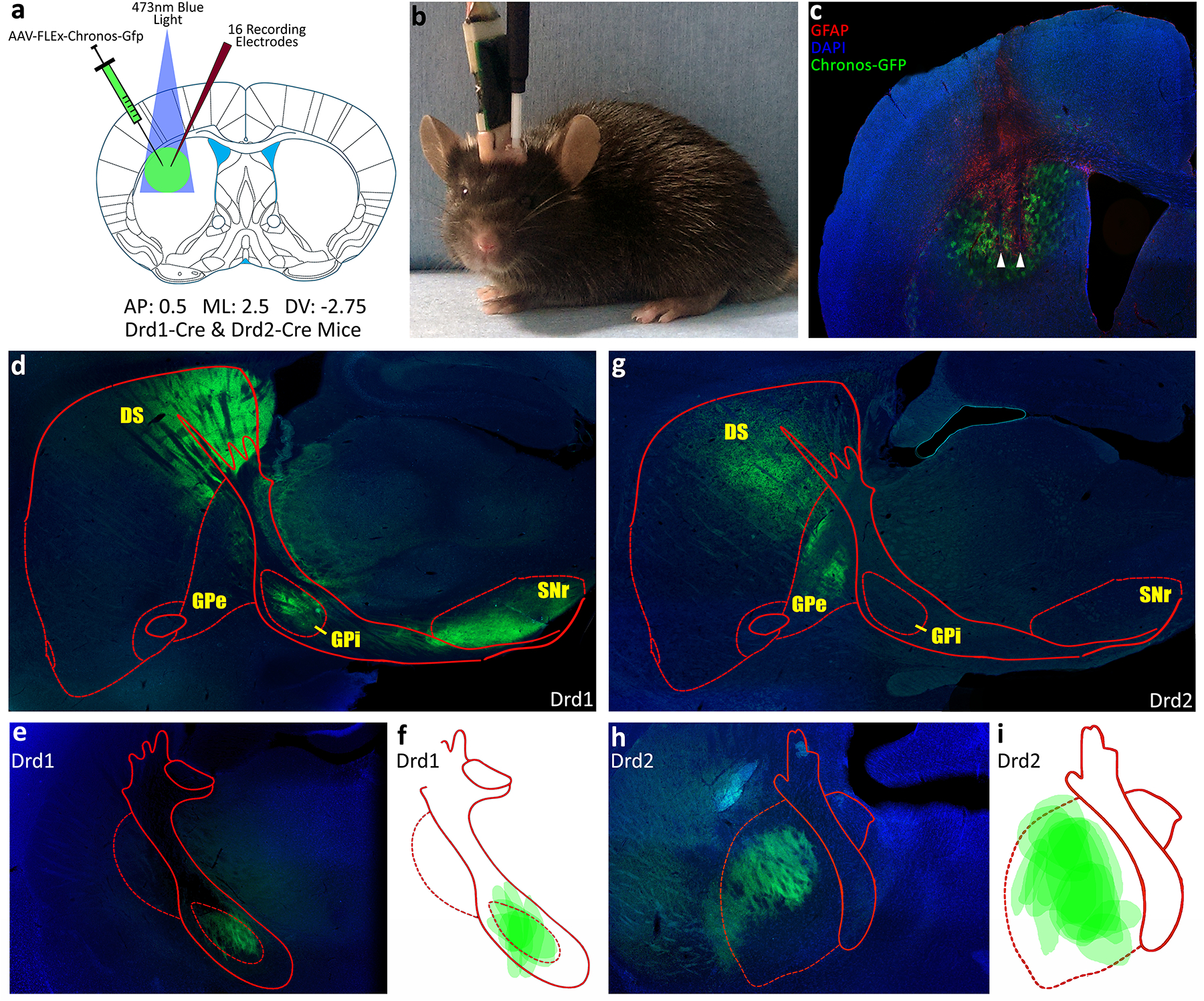

Figure 1.

a) Schematic representation of AAV-EF1a-FLEX-Chronos-GFP injections and optogenetic and microwire array implants. b) Post surgery mouse in the test chamber connected to the electrophysiological recording harness and optical stimulation fiber simultaneously. c) Example coronal slice showing Chronos-GFP in green and wire damage (GFAP) in red on a blue DAPI counterstain. d,e) Representative histology showing Chronos-GFP expression in direct pathway of a D1-Cre mouse. f) Reconstruction of Chronos-GFP expressing axon terminals in GPi of all experimental D1-Cre mice. g,h) Representative histology showing Chronos-GFP expression in indirect pathway of a D2-Cre mouse. i) Reconstruction of Chronos-GFP expressing axon terminals in the GPe of all experimental D2-Cre mice.

Surgery

Mice (25–30g) were anesthetized and surgically prepared for chronic, extracellular single unit recording as described previously (Barker et al., 2014) using a fully automated stereotaxic instrument (Coffey et al., 2013). Each animal was intra-cranially injected with 1ul of AAV-EF1a-FLEX-Chronos-GFP (titer>3×1012) at the following coordinates relative to bregma over 10min (ML 2.5mm, AP 0.5mm, DV −2.75mm; right side). Following injections, animals were implanted with a circular array of 15× 25μm stainless steel micro-wires (Micro-Probes, Gaithersburg, MD) surrounding a 200μm, 39NA, optical fiber (Thor Labs; Newton, NJ) through the same craniotomy. The micro-wires extended 300μm ventral to the tip of the optical fiber and a maximum of 500μm laterally from the center of the optical fiber, allowing for illumination of the entire wire array (Fig. 1a). Opto-arrays were lowered using a motorized stereotaxic device (Coffey et al., 2013) at a rate of 200μm/min and to a depth of 2.75mm below the surface of the skull. The array was sealed to the surface of the skull with cyanoacrylate. The microwires led to a connector strip embedded in dental cement on the skull. Animals were given one week to recover from surgery, and had ad lib access to food and water at all times.

Electrophysiological Recording

When recording commenced, a recording harness (Triangle Biosystems; Durham, NC) connected to a commutator was attached to the connector strip on the skull, allowing free movement within the Plexiglas recording chamber (25cm × 40cm × 40cm; Fig. 1b). Signals were amplified and filtered (450Hz to 10kHz; roll off 1.5dB/octave at 1kHz and −6dB/octave at 11kHz), and digitized (50kHz sampling frequency per wire) for off-line analysis (DataWave Technologies; Loveland, CO). Every neuron in this study was cluster cut offline using strict procedures developed in our lab over 30 years (West et al., 1990; Carelli et al., 1991; Coffey et al., 2015). We use waveform parameters to isolate single units from each recording, and we produce auto-correlograms from each neuron’s sorted spike timings to ensure that only a single neuron exists in each recording. If any spike occurs within the natural 2ms refractory period of a MSN, the entire channel was discarded. This is true for both the body exam and the optogenetic identification. A statistical analysis of this technique has shown that the waveforms we record on a single wire are significantly more likely to belong to a single neuron, then two or multiple neurons (Coffey et al., 2015).

Optogenetic Identification of D1 & D2 Receptor Expressing Neurons

Light stimulation consisted of a 1min baseline recording period, followed by 4 blocks of light stimulation at increasing intensities, ranging from 0.1mW to 03.0mW measured at the fiber tip (~1–25mW/mm2; Kravits et al., 2013). Each stimulation block consisted of 100× 5ms light pulses delivered at 1Hz. Each block was separated by a 1min “laser-off” interval. To determine if neurons were light sensitive, a baseline firing rate (FR) and standard deviation were calculated for each single neuron from the 1m baseline recording as well as all “laser-off” intervals. If a neuron’s average FR during the 5ms light stimulations, in any intensity block, exceeded its 99.5% confidence interval from baseline, it was deemed light sensitive (Kravits et al., 2013). Any neurons deemed light sensitive in D1-Cre animals were identified as D1 expressing neurons of the direct pathway, and any neurons deemed light sensitive in D2-Cre animals were identified as D2 expressing neurons of the indirect pathway. While some Cholenergic interneurons may express Chronos in D2-Cre animals, these neurons constitute an extremely small fraction of striatal units, and are easily identified based on their high baseline FR. Any neuron with a non-movement baseline FR greater than 5 spikes/s was considered to be an interneuron and was removed from the study.

Body Exam

Procedures for conducting the somatosensorimotor exam were similar to those used recently in a study of mice (Coffey et al., 2016) and previously in rats (Carelli and West, 1991; Cho and West, 1997; Prokopenko et al., 2004). The change in FR of a type IIb neuron during activity of the related body part is exclusively an increase. Therefore, animals were handled daily, which increased the likelihood of remaining still. The lack of movement and corresponding low baseline FRs of DLS MSNs were essential for detecting phasic increases in FR during stimulation. Body exams required weeks of patient, daily handling before and after surgery. The exam was conducted in its entirety and video recorded over several sessions (~1h/session). Multiple stimuli (at least 10) of each type were applied to each body part. Cutaneous stimulation was delivered via a handheld probe (2mm in diameter), calibrated to deliver 2–4g of force. The probe travels a distance of up to 3cm in 0.15–0.75s. All accessible body parts (head, vibrissae, paw, chest, chin, snout, ear, shoulder, cheek pad, and trunk) underwent stimulation of various types, e.g., cutaneous touch, passive manipulation, and active movement. Body parts were observed during active movement, were tapped with the probe, and the fur or skin was gently palpated. Passive manipulation was applied to the limbs and neck. The latter, achieved by gently manipulating the harness, was used to identify neurons related to head movement. Firing in relation to the snout, chin or trunk was evaluated using cutaneous stimulation. Testing of the shoulder consisted of cutaneous stimulation, palpation, either manually or with the probe, and passive rotation. Vibrissae collectively were stimulated by stroking with the probe forward, backward, up and down. Multiple stimuli (at least 10) of each type were applied to each body part. All types of manipulation are referred to here as “stimulation”. Habituation was minimized by the continual shifting of stimulation to different body parts in different sequences. An example video from a head movement exam can be seen in the supplemental files (Supplementary Vid. 1).

Video Analysis

Video recordings time stamped by the computer which also recorded neural activity (Datawave Video Bench; Loveland, CO) were obtained during every exam. They enable unambiguous identification (33ms resolution) of the onset and offset of each individual stimulus using post-hoc frame-by-frame (30 frames/s) analysis. The onset of each movement or touch was defined as the timestamp of the video frame immediately prior to the frame that first captured body part movement or touch, while offset was defined as the timestamp of the first video frame after the frame that captured the end of body part movement or touch. Video analysis was used to filter out trials containing extraneous events, such as movements of non-stimulated body parts. This “purification” of stimuli, to the extent possible, enabled a clear depiction of a difference between Stimulation FR vs Baseline FR with as few as 10 trials. When more than one body part moved on a given trial, not only did we discard the trial and select trials lacking extraneous movements, we also examined trials that isolated stimulation of the extraneous body part, in order to verify lack of responsiveness. The protocols described here are the same as those that were effective in our recent identification of DLS neurons related to body parts in wild type mice (Coffey et al., 2016).

Identifying Type IIb Medium Spiny Neurons with Firing Related to Body Part Stimulation

Rasters and peri-event time histograms (PETHs) displaying FR of individual neurons were constructed using video-defined nodes. For each neuron, raster-PETHs corresponding to all examined body parts were created. The mean Stimulus FR was defined as the average FR during body part stimulation, i.e., between all onset-to-offset nodes set during video analysis. The mean and standard deviation for Baseline FR were calculated during all periods of non-stimulation by the experimenter, during which time the animals were not moving. Average FR during the stimulus was compared to Baseline FR and baseline variance. Each neuron was tested for sensitivity to 10 body parts, so the alpha value for determining sensitivity was Bonferroni corrected from 0.05 to 0.005. Thus, any Stimulus FR exceeding the neuron’s 99.5% confidence interval for Baseline FR was deemed to be a type IIb medium spiny neuron.

Fluorescent Immunohistochemical Labeling

Following all recordings (~30 days after surgery) animals received an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and were perfused transcardially with 0.9% phosphate buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were post-fixed for 48h in 4% paraformaldehyde and transferred to a 30% sucrose solution. Brains were sliced into 30μm coronal sections. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed on free floating brain tissue. Slices were incubated for one hour in a 4% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and 0.3% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffer. Sections were rinsed and incubated overnight in a 4% BSA with rabbit anti-GFAP antibody. Next, tissue was rinsed and incubated in anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to a red fluorophore (Alexa Fluor ® 555). Subsequently, tissue was washed with phosphate buffer and mounted on a slide using mounting medium containing Dapi (nucleic acid stain), which serves as a counter stain. All slices were photographed and recorded with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M, Fluorescence microscope. The presence of astrocytes with upregulated GFAP along the entire length of microwires and the fiber optic allowed tracing of microwire tracks by staining for GFAP protein (Polikov, 2006; Fig. 1c). If all 15 wires could not be tracked from their entrance into the cortex to their tips in the DLS, data from that animal were discarded.

Direct and Indirect Pathway Reconstruction

One D1-Cre animal and one D2-Cre animal were used to reconstruct the striato-pallidal projections of the direct and indirect pathways. Each animal was injected with 1μl of AAV-EF1a-FLEX-Chronos-GFP in the right DLS. Following 2 months of AAV expression, the animals were sacrificed and their brains were sliced coronally at 100μm thickness for the extent of the striatum and globus pallidus. The slices were then serially mounted and imaged in high resolution. To ensure the highest resolution possible for tracking projections, each coronal section was imaged in 9 overlapping frames under a 4x objective and then stitched back together using an automated stitching algorithm (Image J; Preibisch et al., 2009). Each coronal section was then aligned using an automated image alignment algorithm (Image j; Thévenaz et al., 1998). Aligned images were rendered as “flythrough” videos (Supplementary Vid. 2; 3).

Results

Viral Tract Tracing and Histological Verification of Wire Tips

For all D1-Cre and D2-Cre experimental mice, viral expression and wire placement was verified through sectioning and fluorescent imaging of the DLS. All neurons in this study were recorded on wires that were histologically verified to terminate in the viral expression field within the DLS (Fig. 1c). Chronos-GFP expressed in D1-Cre mice projected exclusively to the GPi (Fig. 1d; 1e; 1f), whereas in D2-Cre mice Chronos-GFP projected exclusively to the GPe (Fig. 1g; 1h; 1i).

Summary of All Wires Implanted into the Dorsolateral Striatum

All 15 wires in the 5 wild type animals terminated in the DLS. All 15 wires were tracked to the viral field in the DLS in 4 D1-Cre animals (1 animal was removed), and all 15 wires were tracked to the viral field in the DLS in 3 D2-Cre animals (2 animals were removed). In total, 12 mice including of 5 WT, 4 D1-Cre, and 3 D2-Cre implanted with 180 microwires were used in the study. Of the 180 wires implanted, 125 yielded neural recordings. Of those 125 recorded neurons, 99 were not identified to be D1 or D2 expressing. Thirteen neurons were identified as D1 expressing MSNs and another 13 neurons were identified as D2 expressing MSNs. Fifty-five wires yielded no recorded neurons (Table 1).

Table 1.

A Summary of all 180 wires implanted into experimental animals.

| Summory of Implanted Wires | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implanted Wires: 180 | |||||||||||||||

| Isolated Single Units: 125 | |||||||||||||||

| Neuron Type | No Correlate | Head Up | Head Down | Head Left | Head Right | Snout | Cheek | Chin | Shoulder | Ear | Paw | Chest | Trunk | Vibrissae | Total |

| Unknown | 61 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 99 | |

| Dl | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 13 | ||||||||

| D2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | |||||||

| 125 | |||||||||||||||

Type IIb Medium Spiny Neurons in the Mouse Dorsolateral Striatum

Of the 125 neurons isolated, 51 broke their 99.5% CI during a specific body part stimulation and were thus deemed Type IIb medium spiny neurons. For all body parts, type IIb neurons increased FR only during stimulation (e.g., not before movement onset) and decreased back to baseline quickly at the offset of stimulation. This pattern was consistent across all body parts (Fig. 2; 3). The remaining 74 neurons were not deemed type IIb neurons. These neurons may not process single body part stimulation, or may have receptive fields that were not easily stimulated (e.g. axial musculature). These non-type IIb neurons were not analyzed further.

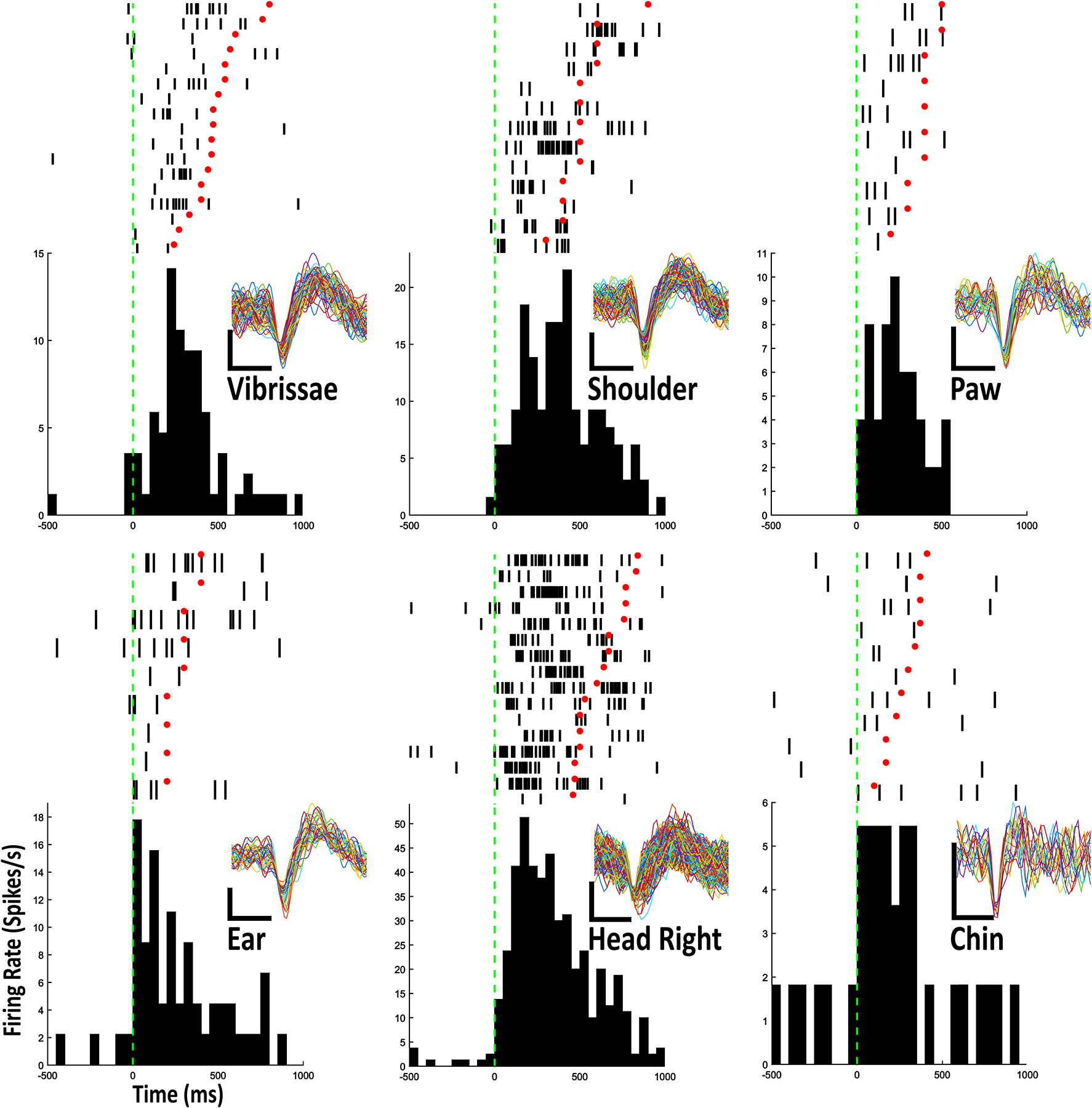

Figure 2.

Example Raster-PETHs for 6 body part stimulations from 6 individual type IIb neurons. Each row in rasters contains 1 stimulation trial. Onset of stimulation is aligned to green dashed vertical line and offset of stimulation is marked with red dot. Vertical ticks represent action potentials. The PETHs show an average of action potentials in 50ms bins. Every cluster cut waveform is shown for each raster-PETH. Scale bar: vertical, 1 mV; horizontal, 0.4 ms

Figure 3.

Example Raster-PETHs for 6 body part stimulated in this study from 6 individual type IIb neurons. Layout is identical to figure 2.

Of the 99 neurons for which dopamine receptor type was unknown, 38 neurons were deemed sensitive to single body part stimulation and categorized as type IIb neurons. One neuron each fired in relation to trunk, contralateral (left) shoulder, contralateral paw, and contralateral ear stimulation; 2 neurons fired in relation to contralateral cheek stimulation; 3 neurons fired in relation to contralateral vibrissae stimulation; 4 neurons fired in relation to head movement in a downward direction; 5 neurons fired in relation to head movement toward the left (contraversive); 5 neurons fired in relation to chest stimulation; 5 neurons fired in relation to stimulation of the snout; 6 neurons fired in relation to chin stimulation and 6 neurons fired in relation to head movement toward the right (Fig. 2; 3; Table 1).

D1 and D2 Optogenetic Identification

Optogenetic identification procedures never produced a neuron sensitive to light stimulation in WT animals. This result was corroborated by a total lack of viral expression in the wild type animals. Without the Cre enzyme, AAV-EF1a-FLEX-Chronos-GFP is not inverted and therefore not expressed, and neurons remain insensitive to very short light pulses. In D1-Cre animals, 13 neurons were deemed sensitive to light stimulation (Table 1), and in D2-Cre animals, 13 neurons were deemed sensitive to light stimulation (Table 1). Neurons that were sensitive to light stimulation increased firing beyond their 99.5% confidence interval during at least one of the 5ms “laser on” periods. Light sensitive neurons produced spikes on between 9.6% and 25.4% of “laser on” periods. Using a short light pulse ensured that it was impossible for surrounding GABAergic MSNs to increase (e.g., disinhibit) the FR of the recorded MSN within 5ms. Further, light sensitive neurons in D1-Cre animals project through the direct pathway to the GPi while light sensitive neurons in D2-Cre animals project through the indirect pathway to the GPe (Fig. 1e; 1f; 1h; 1i).

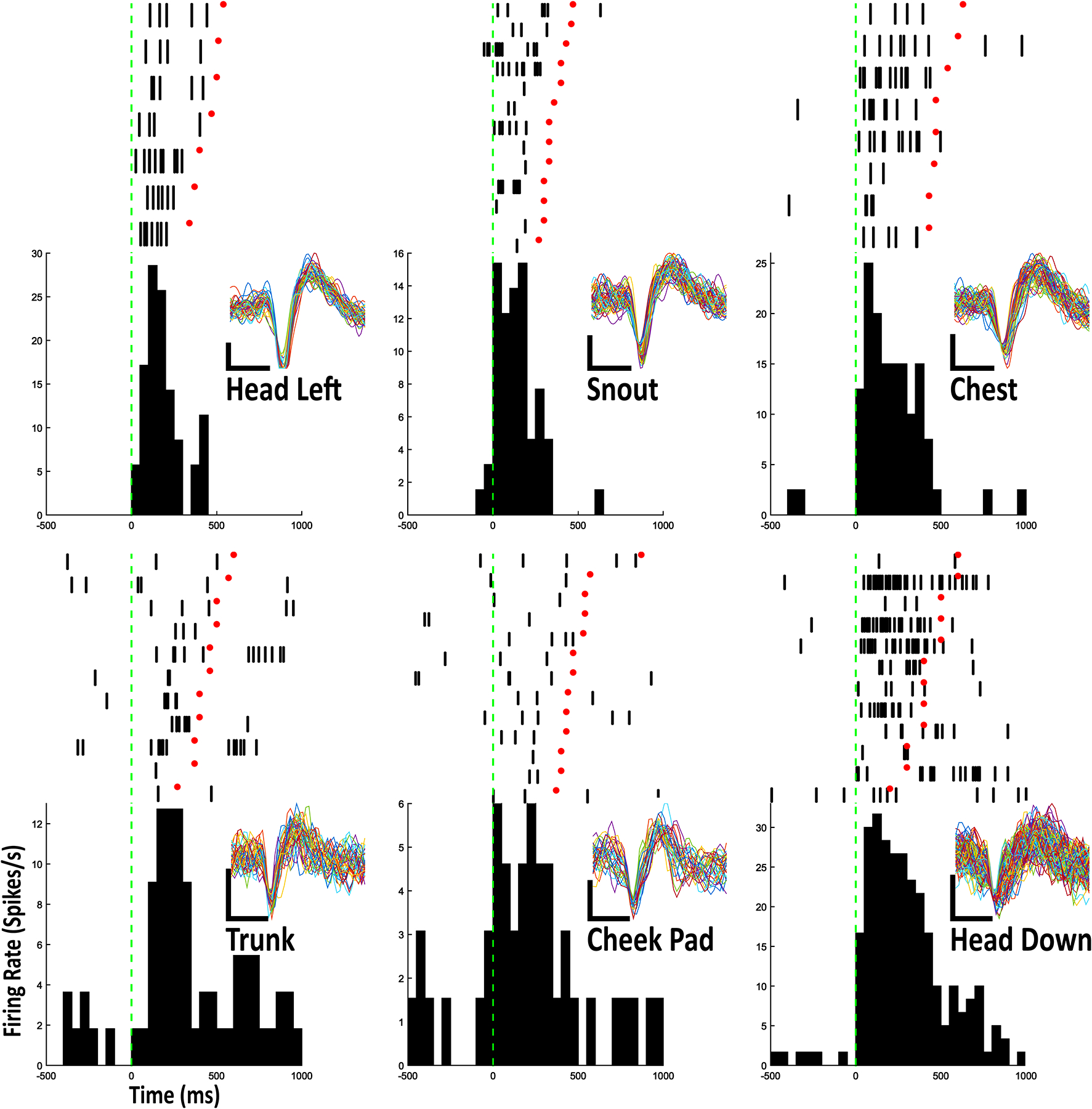

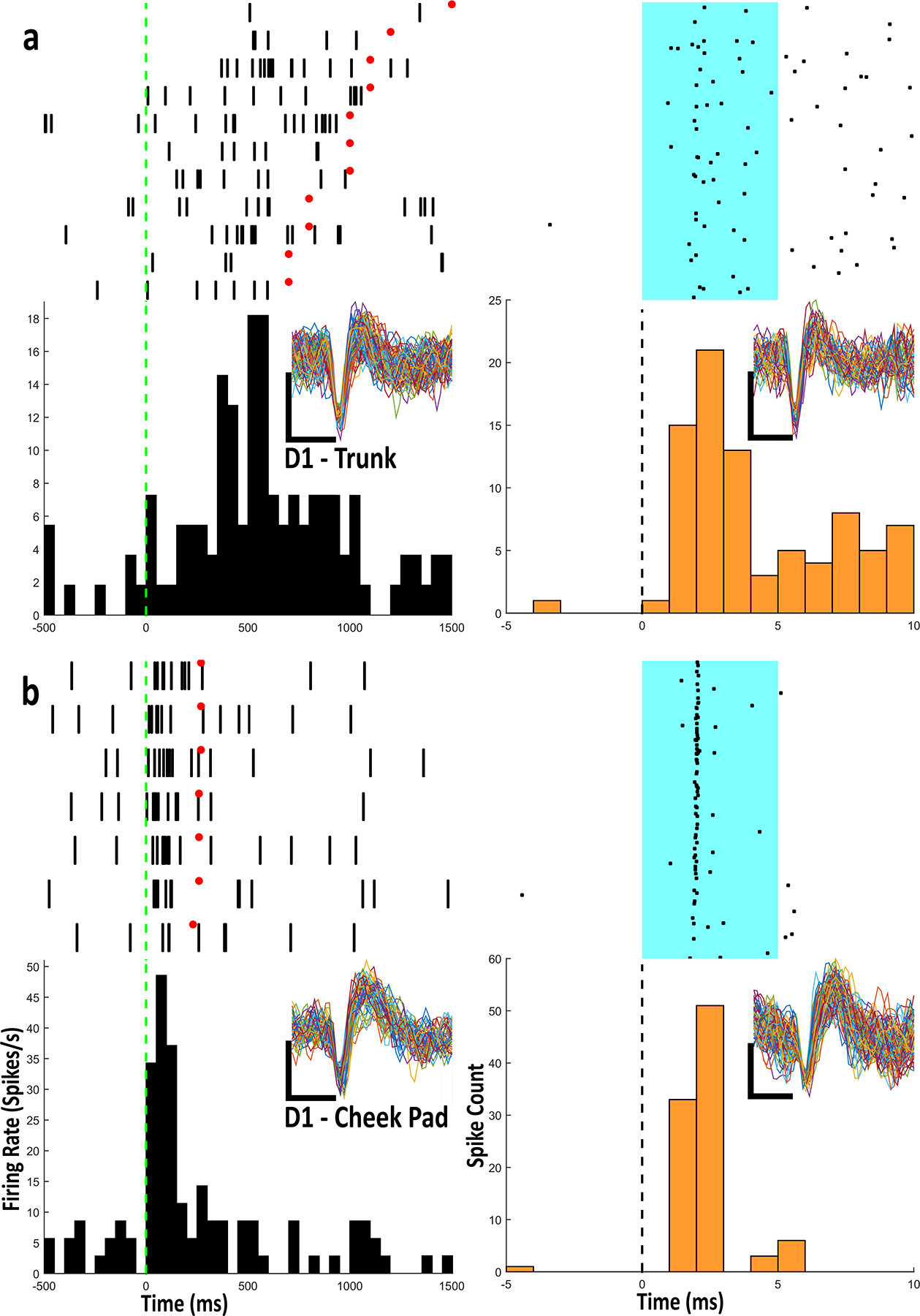

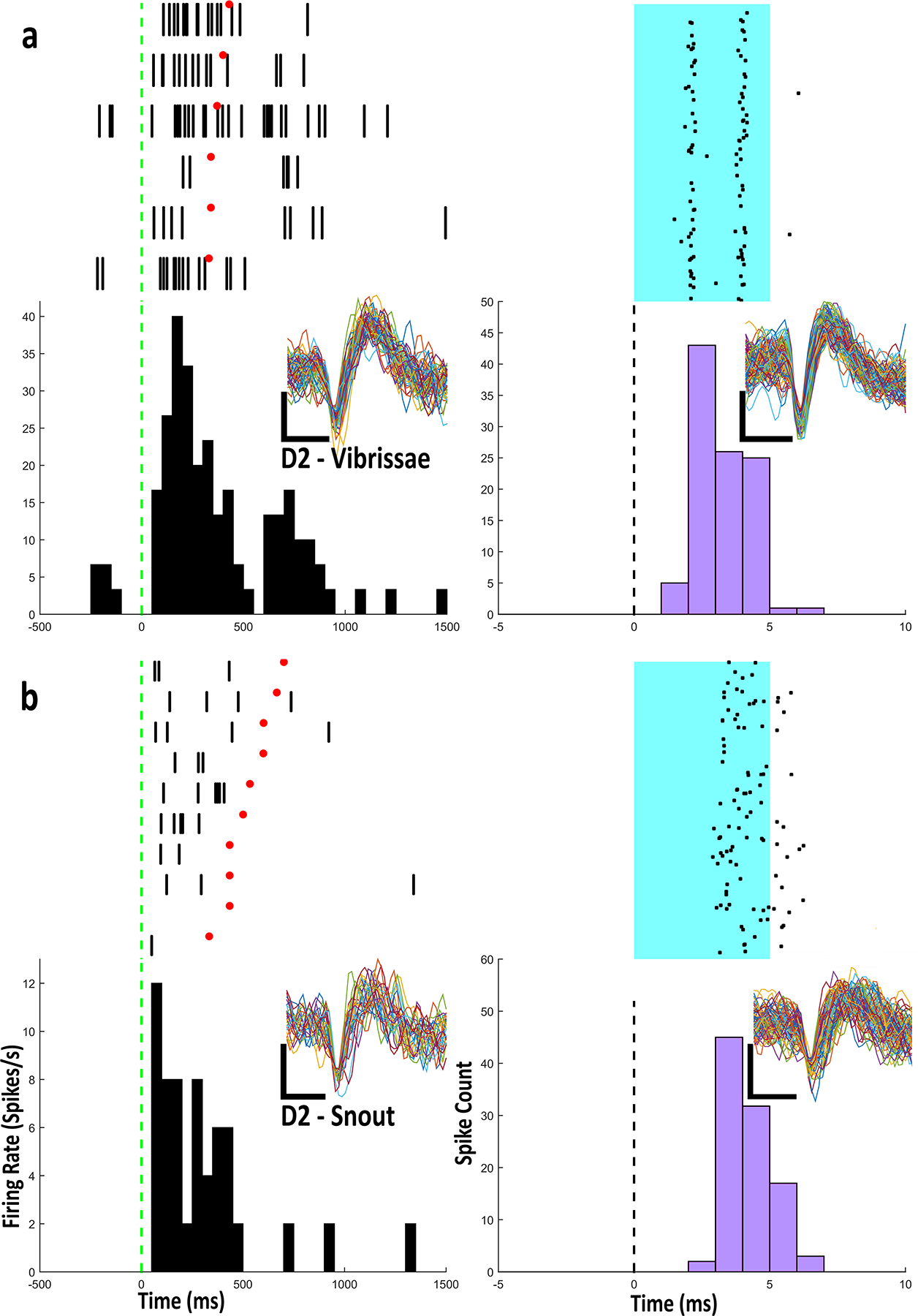

Both D1 and D2 MSNs can be Type IIb Medium Spiny Neurons

The type IIb MSNs in D1-Cre and D2-Cre animals were identified with the same criteria as the WT neurons. Of the 13 identified D1 neurons, 7 were not categorized as type IIb neurons, and did not exhibit firing related to body part stimulation. Of the 6 remaining D1 neurons, 1 neuron fired in relation to head movement in the upward direction, 1 neuron fired in relation to head movement to the left, 1 neuron fired in relation to snout stimulation, 1 neuron fired in relation to contralateral cheek stimulation (Fig. 4b), and lastly, 2 neurons fired in relation to trunk stimulation (Fig. 4a). The waveforms of these neurons were identical during body part stimulation and light stimulation (Fig. 4). Of the 13 identified D2 neurons, 6 were not categorized as type IIb neurons. Of the remaining 7 D2 expressing neurons, 1 neuron fired in relation to chin stimulation, 1 fired in relation to contralateral shoulder stimulation, 1 fired in relation to contralateral vibrissae stimulation (Fig. 5a), 1 fired in relation to head movement in a downward direction, 1 fired in relation to head movement in the upward direction, and 2 neurons fired in relation to snout stimulation (Fig. 5b). The waveforms of these neurons were identical during body part stimulation and light stimulation (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

a) Example Raster-PETHs from an optogenetically identified D1 type IIb neuron with firing related to trunk stimulation. All aspects of Raster-PETHs for body part stimulation are identical to previous figures. For light stimulation, each row in rasters contains 1 light stimulation trial. Onset of stimulation is aligned to dashed line and lasts for duration of cyan patch (5ms). Black dots represent action potentials. PETHs show summation of action potentials in 1ms bins. b) Example Raster-PETHs from an optogenetically identified D1 type IIb neuron with firing related to cheek stimulation. Every cluster cut waveform from the body part and light stimulation is shown for each raster-PETH. Scale bar: vertical, 1 mV; horizontal, 0.4 ms

Fibure 5.

a) Example Raster-PETHs from an optogenetically identified Drd2 type IIb neuron with firing related to vibrissae stimulation. b) Example Raster-PETHs from an optogenetically identified Drd2 type IIb neuron with firing related to snout stimulation. Every cluster cut waveform from the body part and light stimulation is shown for each raster-PETH. Scale bar: vertical, 1 mV; horizontal, 0.4 ms

Summary of Type IIb Medium Spiny Neurons

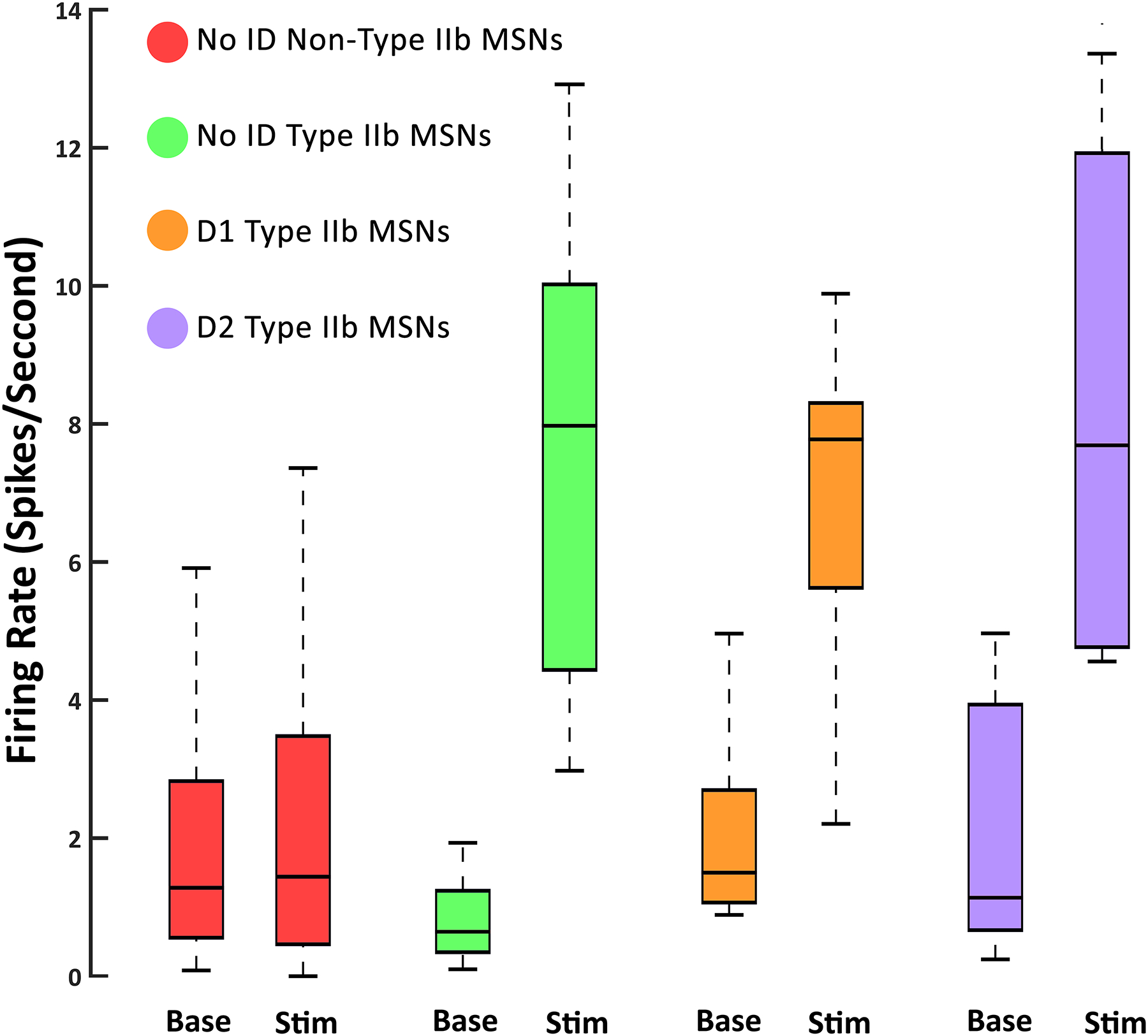

All type IIb neurons processed body part stimulation similarly whether they were unidentified, D1 expressing, or D2 expressing (Fig. 6). Unidentified type IIb neurons on average increased FR from 0.75 spikes/s during baseline to 7.95 spikes/s during body part stimulation. D1 type IIb neurons on average increased FR from 1.65 spikes/s during baseline to 7.91 spikes/s during stimulation. D2 type IIb neurons, on average, increased FR from 1.24 spikes/s during baseline to 7.89 spike/s during stimulation. We observed no significant difference in stimulation FR between all 3 categories of type IIb neurons. Unidentified type IIb neurons’ FR during stimulation did not differ from that of D1 type IIb neurons [KS=0.33, p=0.57]. Unidentified type IIb neurons’ FR during stimulation did not differ from that of D2 type IIb neurons [KS=0.27, p=0.75]. D1 type IIb neurons’ FR during stimulation did not differ from that of Drd2 SBP neurons [KS=0.26, p=0.85]. Non-type IIb MSNs exhibited no difference in FR between baseline and stimulation [KS=.35, p=.68].

Figure 6.

Average FRs for all neurons during non-movement (Base) and body part stimulation (Stim). There was no significant difference in FR at baseline between any group, or between baseline and stimulation for non-type IIb MSNs. FRs during body part stimulation were also not significantly different for D1, D2, or unidentified type IIb MSNs. All type IIb MSNs fired similarly during stimulation of their related body part.

Selectivity of Type IIb Medium Spiny Neurons

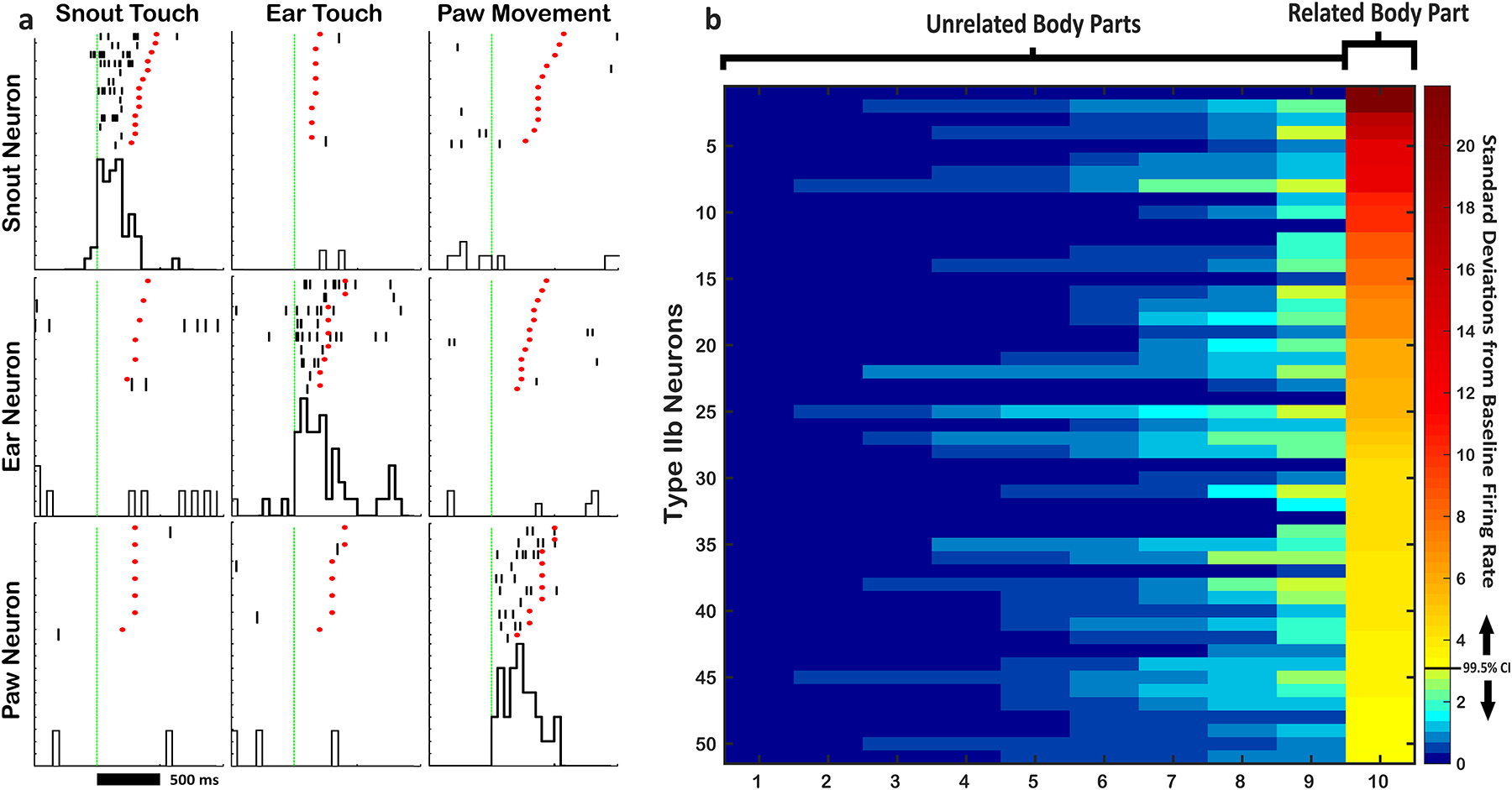

Type IIb neurons fire during stimulation of a particular body part, but not during stimulation of other body parts (Fig. 7). Furthermore, neurons that process head movement were selective for a single direction. The extent of this selectivity can be visualized through a heat map of activity (Fig. 7b). All type IIb neurons fired highly selectively during stimulation of their correlated body part and fired minimally during all other body part stimulations and no type IIb neuron in this study was identified as being related to more than one body part. Minimal observed firing during stimulation of unrelated body parts could involve the receptive zones of some type IIb neurons crossing the boundaries that were required for stimulating each category in the present approach of objectively testing up to 15 simultaneously recorded neurons, without the ability to customize stimulation for each neuron as in previous studies (Prokopenko et al, 2004).

Figure 7.

a) Example Raster-PETHs showing selectivity of 3 different type IIb neurons. Each row shows 3 Raster-PETHs from 1 neuron. Each column shows responses of the 3 different neurons to single body part stimulation. Note that each neuron spikes only during stimulation of its related body part, and not during stimulation of other body parts. b) Heat map showing the extent of selectivity for all type IIb neurons in the study. Each row represents a single neuron and each column represents a body part. FR during stimulation is converted to sigma (standard deviations from baseline FR) and coded in color. Each neuron’s correlated body part is aligned to the right column, while each unrelated body part is shown in the remaining columns, sorted from least to most (left to right) firing during stimulation.

Discussion

Type IIb Neurons in the Mouse Dorsolateral Striatum

While it is known that the mouse striatum responds to somatosemsorimotor activity (Cui et al., 2003), this study was the first to systematically study type IIb neurons in the direct and indirect pathways of the mouse striatum. These neurons show consistency with previous studies, especially those in the rat. For example, 55 of 125 (40.8%) neurons in this study were found to fire in relation to single body part stimulation; a nearly identical ratio of type IIb neurons (524 of 1287; 41%) found in a larger sample of rat DLS neurons (Cho and West, 1997). Furthermore, although the sample of D1 and D2 neurons was relatively small, both groups showed similar ratios of type IIb neurons (45–55%). Finally, type IIb MSNs in the mouse striatum are selective for a single body part and direction of movement, as they are in the rat (Cho and West, 1997; Carelli and West, 1991).

Drd1 and Drd2 MSNs Can Be Identified Unambiguously

The present study used D1-Cre and D2-Cre mice, which are well categorized and highly representative of endogenous D1 and D2 in the direct and indirect pathways (Gerfen et al., 2008). We were able to unambiguously identify those neurons by their response to a brief 5ms light pulse, and we are confident in our ability to record just a single neuron on any given wire across multiple recording sessions (Coffey et al., 2015). We chose a very conservative identification procedure with a short light pulse to ensure that the neurons classified as D1 and D2 MSNs were in fact directly sensitive to the light stimulation, and not to secondary stimulation (e.g. through multisynaptic activation). Finally, every animal’s brain was dissected to determine if the opsin expressing neurons in D1 animals projected to GPi, and if the opsin expressing neurons in D2 animals projected to GPe.

Type IIb MSNs Reside in Both the Direct (D1) and Indirect (D2) Pathways

Given the substantial anatomical differences between D1 and D2 MSNs, as well as the functional differences proposed by the “competing motor programs” hypothesis, it was predicted that D1 and D2 neurons would process body part stimulation differently. However, both D1 and D2 MSNs type IIb neurons processed single body part stimulation similarly. First, roughly the same proportion (~50%) of Drd1 and Drd2 MSNs were classified as body part sensitive type IIb MSNs, which matches the ratio of body part sensitive neurons in the wild type mouse, as well as in rats and monkeys. Second, both D1 and D2 type IIb neurons had similar baseline FRs (~1 spike/sec) and stimulation FRs (~8 spikes/sec), and both were similar to the wild type mouse. Finally, both D1 and D2 neurons showed selectivity to a single body part. No neuron in either group was classified as a type IIb neuron related to more than one body part.

Functional Hypotheses of the Direct and Indirect Pathways

Our result, that both D1 and D2 neurons increase FR during stimulation, is consistent with what is known about corticostriatal input to MSNs. They are also consistent with a theory which suggests that coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements (Chan et al., 2005, Brown, 2007). However, they are inconsistent with the “competing motor programs” hypothesis. For D2 MSNs to inhibit “competing motor programs”, indirect pathway neurons would have to be active during all actions other than their related motor program. However, D2 MSNs were only ever active during single body part stimulations. Further, for a D2 neuron to inhibit movements other than its related movement, its target neurons in pallidum would also have to be responsive to stimulation of body parts other than the one currently moving. No such result has ever been reported; the specificity of phasic firing in relation to movement around an individual joint is similar between GPi and GPe neurons (Iansek and Porter, 1980; Erez et al, 2011), and is lost only in disease models (Filion et al 1988; Rothblat and Schneider, 1995). We have recently suggested that maintaining low FR of MSNs that are unrelated to the current movement may involve striatal fast spiking interneurons that respond to individual body parts (Kulik et al, 2016).

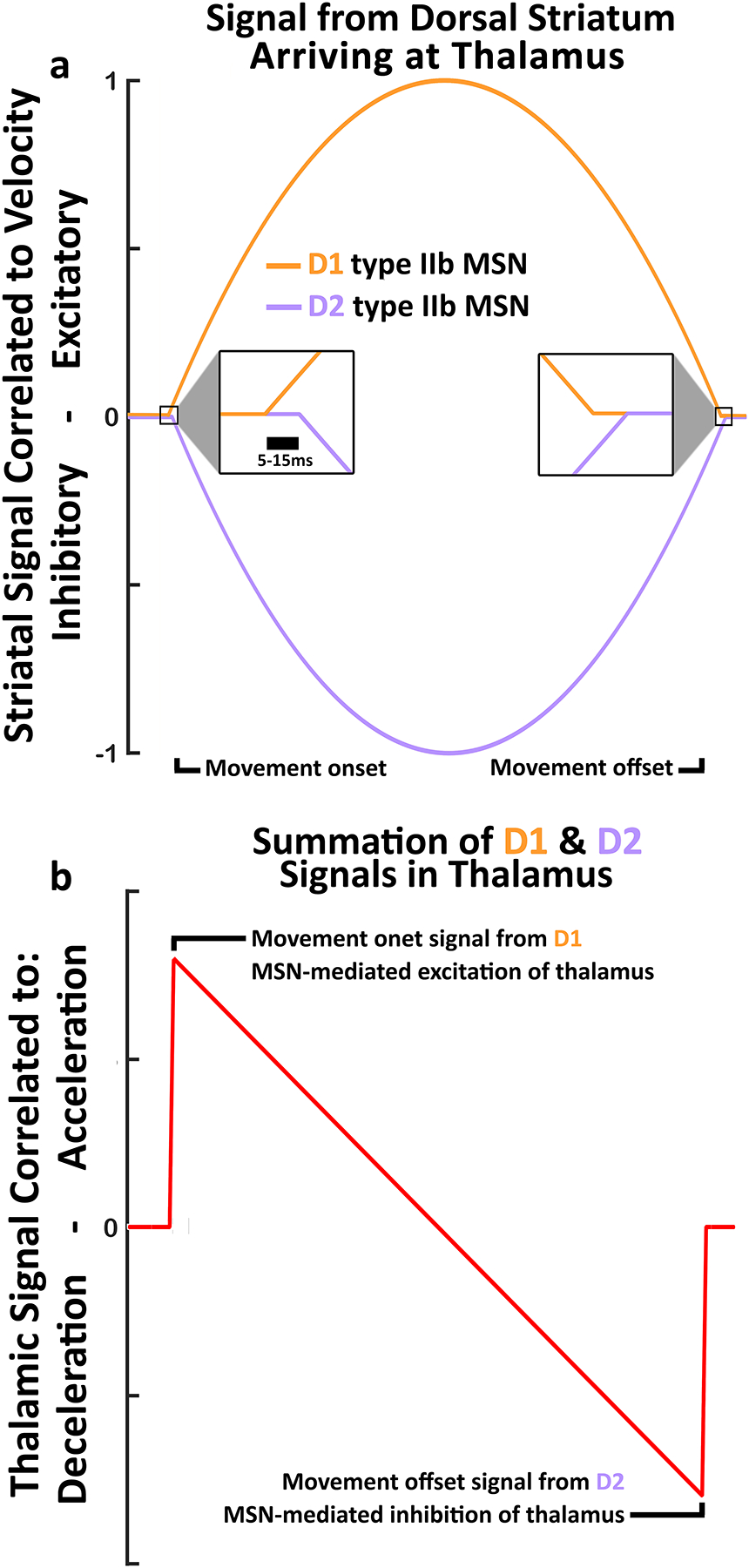

The Direct and Indirect Pathway as a Differentiator Circuit

Of numerous possible explanations for the segregation of D1 and D2 MSN outputs, we suggest a model that is consistent with the role of DLS as a sensorimotor integrator for refining ongoing movement. It is known that type IIb MSNs in the DLS exhibit FRs correlated to some parameters of movement. Using velocity as an example, some type IIb neurons in the direct pathway send current velocity information “directly” to motor thalamus. The indirect pathway, on the other hand, projects through more synapses and becomes inhibitory before reaching motor thalamus ~5–15ms delayed. Throughout the duration of a movement, type IIb MSNs in the indirect pathway could send a time-lagged and inverted (inhibitory) copy of the velocity signal to thalamus, allowing it to compute the difference between the current velocity and the immediately preceding velocity of the movement. This is effectively a differentiator circuit which allows the thalamus to calculate the change in movement velocity (acceleration) from two inverted and time-lagged velocity signals (Fig. 8). This kind of process could be useful in refining an ongoing movement, as the thalamus could calculate change in any movement parameter (position, direction, velocity, etc.), and make corrections to trajectory. This explanation also accommodates the cessation of movement induced by artificially activating only the indirect pathway found by Kravitz et al (2010). The model presented in Fig. 8 is consistent with the present findings and is more parsimonious with the “coordinated timing or synchrony” hypothesis than “competing motor programs” hypothesis. While this model may be testable, it is far beyond the scope of the current project, and would make for an excellent future direction.

Figure 8.

a) Theoretical signals correlated to velocity from D1 and D2 neurons arriving at thalamus. Both types of DLS MSNs are excited by cortical input at movement onset. At Thalamus, D1 signals are excitatory and arrive first, while D2 signals are inhibitory and arrive lagged by ~5 to 15ms. b) The summation of the D1 and D2 signals in the Thalamus along the same time axis as a). This summation produces a unique pattern that carries new information, including a start signal from D1 excitation arriving alone, then a continuous measure of change in velocity (acceleration/deceleration), followed by a stop signal from D2 inhibition arriving alone.

Conclusion

In this study we were able to unambiguously identify D1 and D2 MSNs in the striatum of awake, behaving, mice. We then studied those neurons with regard to single body part processing. While type IIb neurons have been well characterized in other species, they were only recently characterized in the mouse (Coffey et al., 2016). It may have been presumed that these neurons would reside only in the direct pathway, however, the present study showed that both the direct and indirect pathways contain type IIb neurons, which phasically increase FR in relation to stimulation of individual body parts. This evidence, combined with a number of other recent studies, supports the theory that the coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements. A new model of the direct and indirect pathways as a differentiator circuit was also proposed which provides a possible mechanism by which coordinated activity of D1 and D2 neurons may provide meaningful information to downstream structures.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video 1. Example of a head movement body exam aligned to the neural recording of a head movement sensitive type IIb neuron. This neuron spikes only during the period of time when the head is moving left.

Supplementary Video 2. Flythrough reconstruction of striatal D1 projections to the GPi.

Supplementary Video 3. Flythrough reconstruction of striatal D2 projections to the GPe.

Significance Statement.

The direct and indirect pathways hypothesis is undergoing a modern reevaluation. One modern theory proposes that activation of direct pathway MSNs facilitates the output of desired motor programs, while activation of indirect pathway MSNs inhibits competing motor programs. A separate theory suggests that coordinated timing or synchrony of the direct and indirect pathways is critical for the execution of refined movements. Here we show that somatosensorimotor responsive type IIb neurons exist in both the direct and indirect pathways, and that their activity is specific to individual body parts. This provides more evidence that there is homogenous and concurrent activation of the pathways during sensation and movement, but is inconsistent with the “competing motor programs” hypothesis. We also suggest an alternate model of the direct and indirect pathways as a differentiator circuit.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Accessibility

The dataset for this experiment is extremely large, and as such is available only upon request from the corresponding author.

References

- Barker DJ, Coffey KR, Ma S, Root DH, & West MO 2014. A Procedure for Implanting Organized Arrays of Microwires for Single-Unit Recordings in the Awake, Behaving Animal. J. Vis. Exp 84, e51004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P 2007. Abnormal oscillatory synchronisation in the motor system leads to impaired movement. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 17, 656–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli RM, & West MO 1991. Representation of the body by single neurons in the dorsolateral striatum of the awake, unrestrained rat. J. Comp. Neurol 309, 231–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Surmeier DJ & Yung WH 2005. Striatal information signaling and integration in globus pallidus: timing matters. Neurosignals 14, 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, & West MO 1997. Distributions of single neurons related to body parts in the lateral striatum of the rat. Brain Res 756, 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KR, Barker DJ, Ma S, & West MO 2013. Building an open-source robotic stereotaxic instrument. J. Vis. Exp 80, e51006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KR, Nader M, & West MO 2016. Single body parts are processed by individual neurons in the mouse dorsolateral striatum. Brain Res 1636, 200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey KR, Barker DJ, Gayliard N, Kulik JM, Pawlak AP, Stamos JP, & West MO 2015. Electrophysiological evidence of alterations to the nucleus accumbens and dorsolateral striatum during chronic cocaine self-administration. Euro. J. Neurosci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crutcher MD, & Delong MR 1984. Single cell studies of the primate putamen. I. Functional organization. Exp. Brain. Res 53, 233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, & Costa RM 2013. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature 494(7436), 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez Y, Tischler H, Belelovsky K, & Bar-Gad I 2011. Dispersed activity during passive movement in the globus pallidus of the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated primate. PloS one, 6(1), e16293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion M, Tremblay L, & Bédard PJ 1988. Abnormal influences of passive limb movement on the activity of globus pallidus neurons in parkinsonian monkeys. Brain research, 444(1), 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty AW, & Graybiel AM 1993. Output architecture of the primate putamen. J. Neurosci 13(8), 3222–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend DM, & Kravitz AV 2014. Working together: basal ganglia pathways in action selection. Trends in Neurosci 37(6), 301–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Paletzki R, & Heintz N 2013. GENSAT BAC Cre-recombinase driver lines to study the functional organization of cerebral cortical and basal ganglia circuits. Neuron. 80(6), 1368–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox AM, & Nelson SB 2007. Layer V neurons in mouse cortex projecting to different targets have distinct physiological properties. J. Neurophysiol 98(6), 3330–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iansek R, & Porter R 1980. The monkey globus pallidus: neuronal discharge properties in relation to movement. The Journal of physiology, 301, 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Kato M, & Shimazaki H 1990. Physiological properties of projection neurons in the monkey striatum to the globus pallidus. Exp. Brain. Res 82, 672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapoetke NC, Murata Y, Kim SS, Pulver SR, Birdsey-Benson A, Cho YK, & Wang J 2014. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nature Meth 11(3), 338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, & Kreitzer AC 2010. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature 466(7306), 622–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Owen SF, & Kreitzer AC 2013. Optogenetic identification of striatal projection neuron subtypes during in vivo recordings. Brain Res 1511, 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik JM, Pawlak AP, Kalkat M, Coffey KR, & West MO 2017. Representation of the body in the lateral striatum of the freely moving rat: Fast Spiking Interneurons respond to stimulation of individual body parts. Brain Research, 1657, 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzle H 1975. Bilateral projections from precentral motor cortex to the putamen and other parts of the basal ganglia: An autoradiographic study in Macaca fascicularis. Brain. Res 88, 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzle H 1977. Projections from the primary somatosensory cortex to basal ganglia and thalamus in the monkey. Exp. Brain. Res 30, 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles SL 1979. Topographic organization of neurons related to arm movement in the putamen. In: Advances in Neurology Chase TN, (ed). Raven Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- McGeorge AJ, & Faull RLM 1989. The organization of the projection from the cerebral cortex to the striatum in the rat. J. Neurosci 29, 503–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW 2003. The basal ganglia and involuntary movements: impaired inhibition of competing motor patterns. Arch. Neurol 60, 1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu A 2008. Seven problems on the basal ganglia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 18, 595–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polikov VS, Block ML, Fellous JM, Hong JS, & Reichert WM 2006. In vitro model of glial scarring around neuroelectrodes chronically implanted in the CNS. Biomat 27(31), 5368–5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, & Tomancak P 2009. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics 25(11), 1463–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopenko VF, Pawlak A, West MO (2004) Fluctuations in somatosensory responses and baseline firing rates of neurons in the lateral striatum of freely moving rats: effects of intranigral apomorphine. Neurosci 125: 1077–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig R, & Silberberg G 2014. Multisensory integration in the mouse striatum. Neuron 83(5), 1200–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothblat DS, & Schneider JS 1995. Alterations in pallidal neuronal responses to peripheral sensory and striatal stimulation in symptomatic and recovered parkinsonian cats. Brain research, 705(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai AX, & Kromer LF 2014. Corticofugal projections from medial primary somatosensory cortex avoid EphA7-expressing neurons in striatum and thalamus. Neurosci 274, 409–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thévenaz P, Ruttimann UE, & Unser M 1998. A Pyramid Approach to Subpixel Registration Based on Intensity. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 7(1), 27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MO, Carelli RM, Cohen SM, Gardner JP, Pomerantz M, Chapin JK, & Woodward DJ 1990. A region in the dorsolateral striatum of the rat exhibiting single unit correlations with specific locomotor limb movements. J. Neurophysiol 64, 690–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Video 1. Example of a head movement body exam aligned to the neural recording of a head movement sensitive type IIb neuron. This neuron spikes only during the period of time when the head is moving left.

Supplementary Video 2. Flythrough reconstruction of striatal D1 projections to the GPi.

Supplementary Video 3. Flythrough reconstruction of striatal D2 projections to the GPe.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset for this experiment is extremely large, and as such is available only upon request from the corresponding author.