Abstract

Objective

To explore maternal humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and the rate of vertical transmission.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted at two university-affiliated medical centers in Israel. Women positive for SARS-CoV-2 reverse-transcription-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) test during pregnancy were enrolled just prior to delivery. Levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike-IgM, spike IgG, and nucleocapsid IgG were tested in maternal and cord blood at delivery, and neonatal nasopharyngeal swabs were subjected to PCR testing. The primary endpoint was the rate of vertical transmission, defined as either positive neonatal IgM or positive neonatal PCR.

Results

Among 72 women, 36 (50%), 39 (54%) and 30 (42%) were positive for anti-spike-IgM, anti-spike-IgG, and anti-nucleocapsid-IgG, respectively.

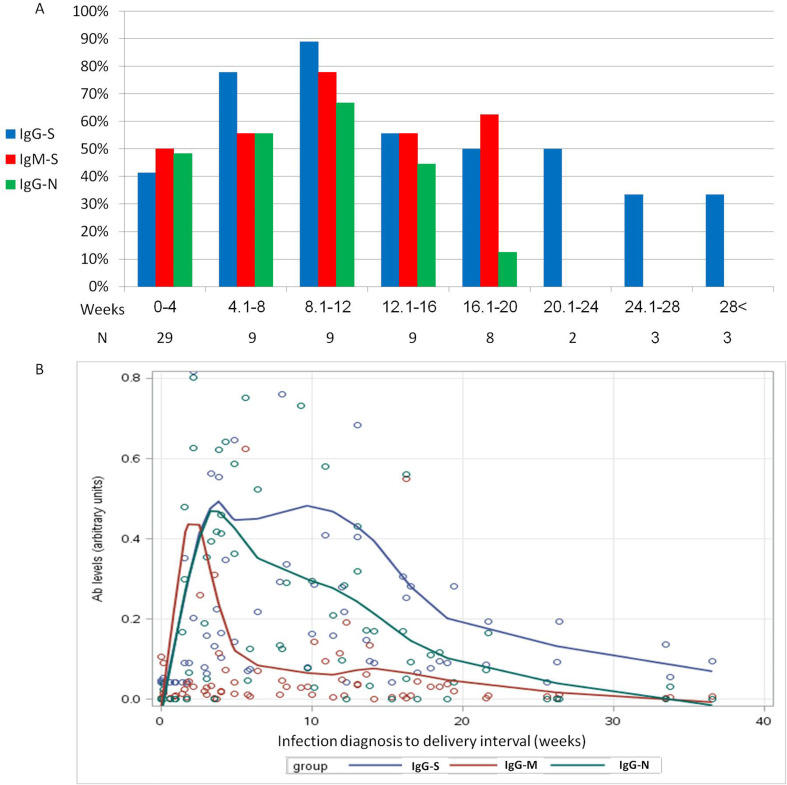

Among 36 neonates in which nasopharyngeal swabs were taken, one neonate (3%, 95% confidence interval 0.1–15%) had a positive PCR result. IgM was not detected in cord blood. Seven neonates had positive IgG antibodies while their mothers were seronegative for the same IgG. Anti-nucleocapsid-IgG and anti-spike-IgG were detected in 25/30 (83%) and in 33/39 (85%) of neonates of seropositive mothers, respectively. According to the serology test results during delivery with respect to the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the highest rate of positive maternal serology tests was 8 to 12 weeks post-infection (89% anti-spike IgG, 78% anti-spike IgM, and 67% anti-nucleocapsid IgG). Thereafter, the rate of positive serology tests declined gradually; at 20 weeks post-infection, only anti-spike IgG was detected in 33 to 50%.

Discussion

The rate of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was at least 3% (95% confidence interval 0.1–15%). Vaccination should be considered no later than 3 months post-infection in pregnant women due to a decline in antibody levels.

Keywords: Antibodies, COVID-19, Neonates, Pregnancy, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

The effect of pregnancy on humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as the rate of vertical transmission are not fully understood. At the beginning of the current COVID-19 pandemic, evidence pointed to a lack of vertical transmission, as determined by amniocentesis, umbilical cord blood, placenta, neonatal secretion, and breast milk sampling [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. However, recent data, mostly from case reports and case series, demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the placenta [[7], [8], [9]], positive reverse-transcription-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal swabs of newborns, and evidence of seropositivity in neonates [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]].

Evidence for vertical transmission is suggested in either positive neonates for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR or the presence of IgM-type antibodies in the newborn since these antibodies do not cross the placenta.

The present study explored maternal humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and the rate of vertical transmission.

Methods

Patient recruitment

This prospective multicenter cohort study was conducted between 3 July 2020 and 24 January 2021 at Emek and Baruch-Padeh Medical Centers, two university-affiliated medical centers in north Israel. The study protocol was approved by the Local Institutional Review Boards (60-20-EMC and 90-20-POR). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in the study. During the study period vaccination was not available in Israel.

The study cohort consisted of pregnant women ≥18 years old who had a positive nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2, as determined by RT-PCR, during pregnancy.

Data collection

Women were enrolled at admission to the delivery ward, before delivery, by one of the team investigators. After enrollment, SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid-IgG, anti-spike-IgG, and anti-spike-IgM levels in maternal and cord blood were measured near delivery. Nasopharyngeal samples were collected from the neonates in the Department of Neonatology and were subjected to SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing. Participants were excluded from the study if both cord blood serology tests and neonatal RT-PCR could not be obtained due to technical reasons.

Determination of SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels

Serum was separated from clot and blood cells by centrifugation (1000 × g, 10 min) using gel separator tubes. Samples were either directly tested for SARS-CoV-2 anti-nucleocapsid-IgG antibodies by the Architect i2000 analyzer on the day of sample collection or were separated into a secondary tube and frozen at –200C until the test was performed. After performing the test, samples were frozen at –200C. For determination of SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike (S1/S2) IgG and IgM antibody titers, samples were thawed and mixed by vortex, and then subjected to ready-to-use assays on automated analyzers, as detailed in Supplement 1.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the rate of vertical transmission, defined as either positive neonatal IgM serology or positive neonatal SARS-COV-2 PCR. Humoral immune response was also evaluated, including the rate of positive mothers for each tested antibody and antibody levels by time between infection and delivery.

Correlation between antibody levels and clinical manifestation of COVID-19 was also evaluated as well as demographic and pregnancy characteristics and data regarding fetal malformations.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated using the binomial proportion test. The rate of vertical transmission was estimated to be 7% when defined by RT-PCR [6]. Assuming that using serology tests increases the rate to 10% versus 0% in noninfected population, 71 women were required (80% power, 5% one-sided alpha).

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. The correlation between maternal and neonatal IgG antibody levels was assessed by the Pearson coefficient. The locally scatterplot smoothing nonparametric regression model was utilized to compare the mean drop in antibody levels over time from COVID-19 diagnosis and delivery. Antibodies levels were normalized by dividing each value by the largest value. Anti-spike antibodies were also multiplied by 3 in order to fit the scale. Antibodies levels below the threshold for positive results according to the kit instructions were set to be zero.

Statistical analyses were carried out with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significance was set at a p value of <0.05. Data were analyzed by the authors EY and ZN.

Results

Seventy-nine women were offered participation in the study. All of them agreed to participate. Among them, 72 had available serology test results. Seven women did not have serology information due to technical reasons. Thirty-six neonates did not undergo nasopharyngeal swabbing for SARS-CoV-2 PCR due to parental refusal. One woman did not have enough serum to determine anti-spike IgM levels.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1 . SARS-CoV-2 antibody profiles of women who had COVID-19 during pregnancy and of their neonates, are presented in Table 2 . Among the 72 women, 36 (50%), 39 (54%), and 30 (42%) women tested positive for anti-spike-IgM, anti-spike-IgG, and anti-nucleocapsid-IgG, respectively. The difference between the rate of positive anti-spike-IgG and anti-nucleocapsid-IgG was statistically significant (p < 0.0001; Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and pregnancy course of women with COVID-19 during pregnancy (N = 72)

| Age | 30.2 (4.6) |

|---|---|

| BMI (kg/M2) | 26.2 (5.1) |

| Number of children | 1.7 (1.5) |

| Place of residency | |

| City >20 000 | 36 (50%) |

| Town≤20 000 | 30 (42%) |

| Village | 6 (8%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Jew | 27 (38%) |

| Arab | 45 (63%) |

| Gestational week at COVID-19 disease | 29.27 (8.94) |

| Trimester at COVID-19 disease | |

| 1 | 5 (7%) |

| 2 | 21 (29%) |

| 3 | 46 (64%) |

| Illness duration (days) | 8 (12) |

| Symptoms | |

| Asymptomatic | 14 (19%) |

| Fever | 12 (17%) |

| Cough | 23 (32%) |

| Dyspnea | 20 (28%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 9 (13%) |

| Loss of smell sensation | 39 (54%) |

| Fatigue | 28 (39%) |

| Myalgia | 23 (32%) |

| Vomiting | 3 (4%) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (8%) |

| Headache | 17 (24%) |

| Interval between COVID-19 infection diagnosis and delivery (weeks) | 9.6 (8.9) |

| Delivery week | 38.9 (1.8) |

| Preterm delivery | 6 (8%) |

| Gestational hypertension/preeclampsia | 4 (6%) |

| GDM | 7 (10%) |

| Neonate gender | |

| Male | 43 (60%) |

| Female | 29 (40%) |

| Cesarean delivery | 16 (22%) |

| Birth weight | 3281 (457) |

| SGA neonate | 2 (3%) |

| APGAR at 1 minute | 3 (4%) |

| APGAR at 5 minute | 1 (1%) |

| Cord pH | 7.3 (0.1) |

BMI, body mass index; COVID, coronavirus disease; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; SGA, small for gestational age.

Values are presented as mean (standard deviation) or number (percent) missing values: BMI-2, cord pH – 8.

Table 2.

SARS-COV-2 antibody profile of women with COVID-19 disease during pregnancy and of their neonates

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid IgG | |

| Negative | 42 (58%) |

| Positive | 30 (42%) |

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG | |

| Negative | 33 (46%) |

| Positive | 39 (54%) |

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike IgG | |

| Negative | 30 (42%) |

| Both positive | 27 (38%) |

| One positive | 15 (21%) |

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 spike IgM | |

| Negative | 35 (49%) |

| Positive | 36 (51%) |

| Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid IgG | |

| Negative | 42 (58%) |

| Positive | 30 (42%) |

| Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG | |

| Negative | 35 (49%) |

| Positive | 37 (51%) |

| Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and spike IgG | |

| Negative | 32 (44%) |

| Both positive | 27 (38%) |

| One positive | 13 (18%) |

| Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 spike IgM | |

| Negative | 72 (100%) |

| Positive | 0 (0%) |

| Neonatal PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Negative | 35 (97%) |

| Positive | 1 (3%) |

Values are presented as number (percent). Missing values: Neonatal PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 36); maternal SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike IgM (n = 1).

Nasopharyngeal swabs were taken to 36 neonates as mentioned above. Comparison between maternal and pregnancy characteristics of mothers of whom nasopharyngeal swab was taken versus not taken is presented in Supplement 2. Among 36 neonates in which nasopharyngeal swabs were taken, one neonate (3%, 95% confidence interval 0.1–15%) had a positive PCR result. IgM was not detected in cord blood. Seven neonates had positive IgG antibodies while their mothers were seronegative for the same IgG. The rest of the neonates were either seronegative or had the same IgG as their mothers, and therefore whether the IgG transferred from the mothers or was self-produced by the fetus could not be determined. No fetal malformations were detected.

Anti-nucleocapsid-IgG and anti-spike-IgG were detected in 25/30 (83%) and in 33/39 (85%) of neonates of seropositive mothers, respectively. Maternal and neonatal IgG antibody levels were positively correlated (Pearson coefficient 0.8, p < 0.001). With regards to the interval between infection and delivery, the highest rate of maternal positive serology tests was when the interval was between 8 to 12 weeks (89% anti-spike IgG, 78% anti-spike IgM, and 67% anti-nucleocapsid IgG). Thereafter, the rate of positive serology tests declined gradually. After 20 weeks, only anti-spike IgG was detected in 33 to 50% (Fig. 1 A).

Fig. 1.

Maternal humoral immune response following infection with SARS-CoV-2 according to time from infection to delivery. (A) The rate of pregnant women with positive serum anti-spike IgG (IgG-S), anti-spike IgM (IgM-S), and anti-nucleocapsid IgG (IgG-N) antibodies over time (weeks) from infection. (B) Locally scatterplot smoothing smooth curve (smoothing parameter 0.4) of mean antibody levels according to time between COVID-19 disease and delivery (weeks). Antibody levels were normalized by dividing each value with the highest value measured. Anti-spike antibodies were also multiplied by 3 in order to fit the scale. Antibody levels below the seropositivity threshold are shown as zero. Note that the graph represents the rate of antibody level decline and not their actual values.

Maternal anti-spike-IgG responses were the longest compared with anti-nucleocapsid-IgG and anti-spike-IgM responses (Fig. 1B).

The rate of women with positive IgG serology was higher if COVID-19 was symptomatic compared to asymptomatic (anti-nucleocapsid-IgG 29 (50%) vs 1 (7%), p = 0.004; anti-spike-IgG 35 (60%) vs 4 (29%), respectively, p = 0.03).

Discussion

The present study explored the rate of vertical transmission and humoral immune responses following maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. Evidence of a vertical transmission rate of at least 3% (95% confidence interval 0.1–15%) was observed. In addition, the highest rate of positive serology tests was among women who delivered 8 to 12 weeks postinfection, after which, the rate of positive serology tests declined gradually. Women delivering 20 or more weeks after infection only carried anti-spike IgG antibodies.

Data regarding vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 are scarce. Most data are based on case reports and small case series. A recent review analyzed 38 studies that assessed COVID-19 and pregnancy. The rate of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 differed by sample source and test type; rates were 2.9%, 7.7%, 2.9%, and 3.7% for neonatal nasopharyngeal swab testing (n = 936), placental sampling (n = 26), cord blood IgM serology (n = 34), and neonatal IgM serology (n = 82), respectively. Amniotic fluid (n = 51) and neonatal urine (n = 17) analyses showed no evidence of vertical transmission [15]. The highest vertical transmission rates (9.7% of n = 31) were observed when testing neonatal fecal/rectal samples [16,17]. In our study, the rate of vertical transmission measured by neonatal nasopharyngeal swab testing was 3%. It should be noted that seven neonates (10%) had positive IgG antibodies with a seronegative mother for the same IgG antibody. This observation may suggest either rapid decline in IgG levels in the mothers or self-produced IgG by the fetus following viral vertical transmission.

Approximately 50% of the mothers in our cohort had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. In a study that examined 392 COVID-19 convalescent subjects, 366 (93.4%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies [18]. Time from positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab correlated with SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody levels (Pearson r –0.281, p < 0.001), with a 50% decline in antibody levels within 6 months; however, levels were still above the cut-off for positive serology result. Thereafter, antibody levels stabilized and remained similar up to 9 months postinfection. In 15% of participants with tests at two time points (n = 59), SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibodies decreased below the positive cut-off [18]. According to our results, during pregnancy, anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers declined more rapidly, with the rate of women with positive anti-spike IgG declining from 89% at 2 to 3 months postinfection to 38% by 5 months postinfection. These data suggest that while immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy are similar to those measured in nonpregnant women [18], antibody titer decline more rapidly during pregnancy. One explanation is due to the transition to a Th2 anti-inflammatory environment during pregnancy that may attenuate the immune response [[19], [20], [21]]. Future studies should explore this hypothesis. In a recent study, in the general population, vaccination at least 3 months postinfection has led to 82% protection rate from reinfection. Protection against reinfection was naturally acquired in the first 3 months postinfection [22]. Based on those and our results, we suggest that vaccination should be considered no later than 3 months postinfection in pregnant women due to a decline in antibody levels.

The strengths of the study lay in its prospective design and evaluation of several antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. The limitations of the study were the lack of serial maternal serology sampling, insufficient sample size for assessing neonatal complications related to COVID-19, and parental refusal to allow neonatal SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swabbing. It should be noted that only five neonates were born within 2 weeks of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection, when serology test sensitivity and specificity might be lower.

Taken together, the rate of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was at least 3% (95% confidence interval 0.1–15%). The highest rate of maternal seropositivity was 8 to12 weeks postinfection. Anti-spike IgG levels remained high for the longest period of time and therefore should be used in serology testing, to avoid false-negative results. We suggest that vaccination should be considered no later than 3 months postinfection in pregnant women due to a decline in antibody levels.

Transparency declaration

All authors declare no competing interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. This study was performed in collaboration with the Israeli Ministry of Health.

Author contributions

MM, EY, OR, SS, JH, TS, AA, YP, and ZN participated in the study design and data collection. EY and ZN analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. MM, OR, SS, JH, TS, AA, and YP critically reviewed the manuscript. MM and EY contributed equally.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Mrs. Ibtehal Odeh and Mr. Ariel Abaev for performing the serology tests.

Editor: R. Chemaly

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.04.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W., et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslin N., Baptiste C., Gyamfi-Bannerman C., Miller R., Martinez R., Bernstein K., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y., Peng H., Wang L., Zhao Y., Zeng L., Gao H., et al. Infants born to mothers with a new coronavirus (COVID-19) Front Pediatr. 2020;8:104. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li N., Han L., Peng M., Lv Y., Ouyang Y., Liu K., et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2035–2041. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Shi Y., Xiao T., Fu J., Feng X., Mu D., et al. Chinese expert consensus on the perinatal and neonatal management for the prevention and control of the 2019 novel coronavirus infection (First edition) Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:47. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan C., Lei D., Fang C., Li C., Wang M., Liu Y., et al. Perinatal transmission of 2019 coronavirus disease-associated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: should we worry? Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:862–864. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baud D., Greub G., Favre G., Gengler C., Jaton K., Dubruc E., et al. Second-trimester miscarriage in a pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323:2198–2200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penfield C.A., Brubaker S.G., Limaye M.A., Lighter J., Ratner A.J., Thomas K.M., et al. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in placental and fetal membrane samples. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Algarroba G.N., Rekawek P., Vahanian S.A., Khullar P., Palaia T., Peltier M.R., et al. Visualization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 invading the human placenta using electron microscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alzamora M.C., Paredes T., Caceres D., Webb C.M., Valdez L.M., La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:861–865. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong L., Tian J., He S., Zhu C., Wang J., Liu C., et al. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamaniyan M., Ebadi A., Aghajanpoor S., Rahmani Z., Haghshenas M., Azizi S. Preterm delivery, maternal death, and vertical transmission in a pregnant woman with COVID-19 infection. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40:1759–1761. doi: 10.1002/pd.5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrazzi E., Frigerio L., Savasi V., Vergani P., Prefumo F., Barresi S., et al. Vaginal delivery in SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnant women in Northern Italy: a retrospective analysis. BJOG. 2020;127:1116–1121. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng H., Xu C., Fan J., Tang Y., Deng Q., Zhang W., et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323:1848–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saadaoui M., Kumar M., Al Khodor S. COVID-19 infection during pregnancy: risk of vertical transmission, fetal, and neonatal outcomes. J Pers Med. 2021;11:483. doi: 10.3390/jpm11060483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotlyar A.M., Grechukhina O., Chen A., Popkhadze S., Grimshaw A., Tal O., et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:35–53. doi: 10.3390/jpm11060483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novazzi F., Cassaniti I., Piralla A., Di Sabatino A., Bruno R., Baldanti F. SARS-CoV-2 positivity in rectal swabs: implication for possible transmission. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:754–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achiron A., Gurevich M., Falb R., Dreyer-Alster S., Sonis P., Mandel M. SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics and B-cell memory response over time in COVID-19 convalescent subjects. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.008. e1-1349.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dashraath P., Wong J.L.J., Lim M.X.K., Lim L.M., Li S., Biswas A., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aghaeepour N., Ganio E.A., Mcilwain D., Tsai A.S., Tingle M., Van Gassen S., et al. An immune clock of human pregnancy. Sci Immunol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enninga E.A., Nevala W.K., Creedon D.J., Markovic S.N., Holtan S.G. Fetal sex-based differences in maternal hormones, angiogenic factors, and immune mediators during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:251–262. doi: 10.1111/aji.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammerman A., Sergienko R., Friger M., Beckenstein T., Peretz A., Netzer D., et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine after recovery from Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1221–1229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.