Abstract

The influence of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) on the efficacies of topical gel formulations of foscarnet against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) cutaneous infection has been evaluated in mice. A single application of the gel formulation containing 3% foscarnet given 24 h postinfection exerted only a modest effect on the development of herpetic skin lesions. Of prime interest, the addition of 5% SLS to this gel formulation markedly reduced the mean lesion score. The improved efficacy of the foscarnet formulation containing SLS could be attributed to an increased penetration of the antiviral agent into the epidermis. In vitro, SLS decreased in a concentration-dependent manner the infectivities of herpesviruses for Vero cells. SLS also inhibited the HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect. Combinations of foscarnet and SLS resulted in subsynergistic to subantagonistic effects, depending on the concentration used. Foscarnet in phosphate-buffered saline decreased in a dose-dependent manner the viability of cultured human skin fibroblasts. This toxic effect was markedly decreased when foscarnet was incorporated into the polymer matrix. The presence of SLS in the gel formulations did not alter the viabilities of these cells. The use of gel formulations containing foscarnet and SLS could represent an attractive approach to the treatment of herpetic mucocutaneous lesions, especially those caused by acyclovir-resistant strains.

Recurrent herpes labialis and herpes genitalis represent the most common clinical manifestations associated with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) infections, respectively. The frequencies of recurrent herpetic infections in the U.S. population are estimated to be 50 to 70% for HSV-1 and 23% for HSV-2 (59). In immunocompetent individuals, recurrences are self-limiting, but in immunocompromised patients, untreated mucocutaneous herpetic infections can be chronic and progressive. Acyclovir and penciclovir and their respective prodrugs valaciclovir and famciclovir are the drugs of choice for the treatment of herpetic infections. However, the emergence of drug-resistant virus mutants after long-term treatment of immunocompromised patients with acyclovir led to an increased number of acyclovir treatment failures in this population (7, 10, 17, 34, 45, 51). The recovery of acyclovir-resistant HSV among clinical isolates from patients with normal immunity has not been associated with the progression of clinical disease (5, 13, 29). However, acyclovir-resistant HSV has been recovered more frequently from immunocompromised patients and has resulted in locally progressive mucocutaneous lesions (5, 13, 18, 19, 29, 31, 34). The majority of acyclovir-resistant HSV clinical isolates are also cross-resistant to penciclovir (39, 60). Alternative therapy for mucocutaneous herpetic infections includes foscarnet (trisodium phosphonoformate), a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits HSV DNA polymerase without activation by viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet is thus effective for the treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpetic infections (25, 38). However, the currently available treatments, either topical or systemic, have only moderate effects on the clinical course of recurrent herpes labialis and herpes genitalis in immunocompetent hosts (6, 9, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50, 55).

Topical formulations for the treatment of herpetic mucocutaneous infections have several potential advantages over formulations used systemically for drug delivery, including targeting of the drug to the specific sites of infection, higher tissue drug levels, reduced side effects, lower treatment costs, and better convenience (49). However, the efficacy of topical formulations is often limited by the poor ability of antiviral agents to penetrate into the skin. The stratum corneum or horny layer constitutes an effective barrier against the penetration of substances into the skin. This layer consists of corneocytes embedded in a double-layered lipid matrix composed of free sterols, free fatty acids, triglycerides, and ceramides (12, 15, 16, 21, 27). Thus, the use of skin penetration enhancers could represent a convenient strategy to increase the penetration of antiviral agents into the skin and therefore their efficacies against herpetic lesions.

Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), an anionic surfactant, possesses skin penetration enhancer properties and enhances penetration into the skin by increasing the fluidity of epidermal lipids (20, 30, 36, 37). The increase in lipid fluidity below the applied site may allow SLS to diffuse in all directions including the radial path (36). SLS could thus increase intraepidermal drug delivery without increasing transdermal delivery. Furthermore, SLS is a potent inhibitor of the infectivities of various HSV strains at quite low concentrations and under very mild conditions (24, 42). Taken together, these properties suggest that SLS could be a potential candidate for use in combination with antiviral agents in topical formulations.

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that the efficacy of 5% acyclovir incorporated into a polymer composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene was more effective than that of the commercial 5% acyclovir ointment (Zovirax) in reducing the development of herpetic skin lesions in mice after a single application given 24 h postinfection (40). The improved efficacy of the gel formulation of acyclovir was attributed to the semiviscous character of the polymer, which allows a more efficient drug penetration into the skin. However, foscarnet incorporated into this polymer had no marked effect under the same treatment regimen. In the present study, we have evaluated whether the incorporation of the skin penetration enhancer SLS into the polymer formulation containing foscarnet could increase the penetration of this drug into the skin and, thereby, its efficacy against HSV-1 cutaneous lesions in hairless mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Foscarnet (trisodium phosphonoformate) and SLS were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). [14C]foscarnet was obtained from Moravek (Brea, Calif.).

Cell lines.

Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cells; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were cultivated in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM; Canadian Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) supplemented with sodium bicarbonate (0.22%), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), l-glutamine (2 mM), and 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Canadian Life Technologies). Human skin fibroblasts (from a healthy control; American Type Culture Collection) were cultivated in EMEM containing sodium bicarbonate (0.22%), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml), l-glutamine (2 mM), l-pyruvate (100 mM), and 10% FBS. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Virus strains.

HSV-1 strain F (American Type Culture Collection), HSV-2 strain 6, which is resistant to acyclovir (thymidine kinase deficient), and HSV-2 strain 15589, which is resistant to foscarnet (kindly provided by Guy Boivin, Centre de Recherche en Infectiologie, Laval University, Sainte-Foy, Québec, Canada), were propagated in Vero cells in complete EMEM containing 2% FBS.

Preparation of topical formulations.

For in vivo studies, we have used a polymer composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene suspended in phosphate buffer (200 mM; pH 6.0) at a concentration of 18% (wt/wt). We selected a pH of 6.0 to correspond to the pH of the skin. Foscarnet and/or SLS was added to the polymer powder and was then dissolved in phosphate buffer (200 mM; pH 6.0). The final concentration of foscarnet was 3% (wt/wt; i.e., 100 mM), while that of SLS was 1, 5, or 10% (wt/wt; i.e., 35, 174, or 347 mM, respectively). For cell culture studies, the formulations were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4).

Plaque reduction assay.

Confluent Vero cells seeded in 24-well plates were infected with approximately 100 PFU of HSV-1 strain F in 0.5 ml of EMEM–2% FBS for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell sheets were washed twice with fresh culture medium, overlaid with 0.5 ml of 0.6% SeaPlaque agarose (Mandel Scientific, St-Laurent, Québec, Canada) in EMEM–2% FBS containing increasing concentrations of foscarnet and/or SLS, and incubated for 2 days at 37°C. The cells were then fixed with 10% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, washed with deionized water, and stained with 0.05% methylene blue. Virus-induced cytopathic effect was evaluated by determination of the numbers of PFU.

Analysis of drug combination effect.

The inhibitory effects of combinations of drugs on the HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect was examined with combinations of various concentrations of the test compounds in a checkerboard design. The drug combination effect was analyzed by the isobologram method as described previously (4). In this analysis, the 50% effective dose (ED50) was used to calculate the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC). When the minimum FIC index of the combined compounds (i.e., FICx + FICy) is equal to 1.0, the combination is assumed to act in an additive manner; when it is between 0.5 and 1.0, the combination acts subsynergistically, and when it is less than 0.5, it acts synergistically. On the other hand, when the minimum FIC index is between 1.0 and 2.0, the combination is subantagonistic, and when it is greater than 2.0, the combination is antagonistic.

Virus inactivation assay.

Prior to infection, HSV-1 strain F, HSV-2 strain 6, or HSV-2 strain 15589 was suspended in PBS or diluted with different concentrations of SLS in PBS and preincubated for 1 h at 37°C in a water bath. Confluent Vero cells, seeded in 24-well plates, were then infected with pretreated viruses (approximately 50 PFU/500 μl) and the plates were immediately centrifuged (750 × g for 45 min at 20°C). Virus was removed by aspiration, and the cell sheets were overlaid with 0.5 ml of EMEM–2% FBS containing 0.6% SeaPlaque agarose. The plates were incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were then fixed, washed, and stained as described above. Virus inactivation was evaluated from the determination of the numbers of PFU.

Cytotoxicities of foscarnet and SLS.

Vero cells, seeded at midconfluency in 24-well plates, were incubated with EMEM–5% FBS (control) or with foscarnet alone or in combination with SLS at various concentrations in culture medium for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Afterward, the cell sheets were washed twice with EMEM–5% FBS and cellular viability was determined with a tetrazolium salt (MTS) which in the presence of phenazine methosulfate is reduced by living cells to yield a formazan product that can be assayed colorimetrically (8).

Cytotoxicities of gel formulations.

Briefly, a semiconfluent monolayer of cultured human skin fibroblasts has been deposited on 0.4-μm cell culture inserts (Millipore Products Divisions, Bedford, Mass.) in six-well plates. The tested compounds (foscarnet and/or SLS), prepared in PBS or incorporated in the gel formulation prepared in PBS, were deposited on top of the cells. The culture medium (EMEM–10% FBS) was added below the insert and was in close contact with cells. This experimental design allowed the elimination of potential interference from the interaction of FBS with the tested compounds. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the cells were washed with PBS and their viabilities were evaluated as described above.

Animal model.

Female hairless mice (SKH1; age, 5 to 6 weeks; Charles River Breeding Laboratories Inc., St-Constant, Québec, Canada) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a mixture containing 70 mg of ketamine hydrochloride (Rogar/STB Inc., Montréal, Québec, Canada) and 11.5 mg of xylazine (Miles Canada Inc., Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada) per kg of body weight. The virus was inoculated on the lateral side of the body in the left lumbar skin area. The skin was scratched six times in a crossed-hatch pattern with a 27-gauge needle held vertically. A viral suspension (5 × 105 PFU/50 μl) was rubbed for 10 to 15 s on the scarified skin area with a cotton-tipped applicator saturated with EMEM–2% FBS. The scarified area was protected with a corn cushion (Schering-Plough Canada Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), which was held on the mouse body with surgical tape (Transpore Surgical Tape; 3M, St. Paul, Minn.). The porous inner wall of the aperture of the corn cushion was made impermeable with tissue adhesive (Vet-bond; 3M Animal Care Products, St. Paul, Minn.) prior to use to prevent drug absorption by the patch, which could act as a reservoir due to the accumulation of drug formulations. The aperture of the corn cushion was also closed with adhesive tape. The mice were then returned to their cages and observed daily.

Treatments.

A single application of the different topical formulations was given 24 h after infection (i.e., prior to the apparition of the zosteriform rash). Briefly, the tape that closed the aperture of the corn cushion was removed, and 15 μl of one of the topical formulations was applied to the scarified area. The aperture of the corn cushion was closed with surgical tape to avoid rapid removal of the drug by the mice and prevent accidental systemic treatment that could occur due to potential licking of the treated lesions. The corn cushions were removed approximately 24 h after application of the topical formulations. The efficacies of the different formulations were evaluated from the mean lesion scores, according to criteria that we have described previously (40, 42), viral titers in skin samples, and survival of animals. No blind evaluations between treatment groups were undertaken in this study.

In vivo skin penetration studies.

In vivo skin penetration studies were designed to compare the influence of SLS in the polymer matrix on the penetration of foscarnet into uninfected and infected skin tissues. Hairless mice were infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F in order to get a fully developed zosteriform rash. On day 5 postinfection, a corn cushion was placed at the inoculation site of the infected mice. A corn cushion was also placed on the left lumbar skin area of control uninfected mice. Fifteen microliters of 3% foscarnet alone or in combination with 5% SLS incorporated in the gel formulation, each of which contained 1.8 μCi of 14C-labeled foscarnet, was deposited into the aperture of the corn cushion as described above. Twenty-four hours following treatment, the mice were killed and blood was withdrawn, placed in heparinized tubes, and centrifuged (10,000 × g for 3 min at 4°C). The patches were then removed carefully and the test area was cleaned with a humidified cotton-tipped applicator and then dried with a sterile gauze to remove the formulations remaining from the application. The test area was stripped with tape 15 times by using an approximately 1-cm length of adhesive tape to remove the stratum corneum. Thereafter, the skin was excised (approximately 2 cm2), and the epidermis and dermis were separated by heat splitting at 60°C in a water bath. The tissues were then treated with Tissue Solubilizer-450 (BTS-450; Beckman Instruments Inc., Irvine, Calif.), decolorized with hydrogen peroxide, and neutralized with glacial acetic acid. The radioactivity associated with tape strips, plasma, and each tissue sample was determined with a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Instruments Canada Inc., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Statistical analysis.

The areas under the curve (AUC) of the mean lesion scores for the different treatment groups were compared by using a one-way analysis of variance test, followed as appropriate by a t test with Fisher's corrections for multiple simultaneous comparisons. The significance of the differences in the mortality rates between infected control and drug-treated groups was evaluated by a chi-square test. The significance of the differences between the AUCs of foscarnet in the stratum corneum tape strips and between the concentrations in the epidermis and dermis was evaluated by an unpaired t test. The significance of the differences between the viabilities of cells incubated with foscarnet in PBS or in gel formulations was evaluated by an unpaired Student t test. All statistical analyses were performed with a computer package (Statview+SE Software; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, Calif.). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Efficacies of topical formulations.

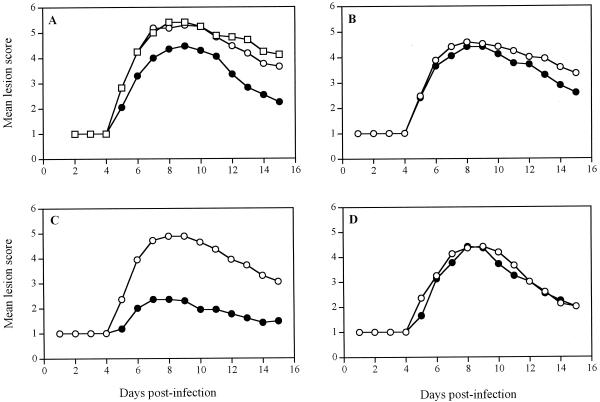

Figure 1 shows the time evolution of the mean lesion scores for untreated infected mice and infected mice treated 24 h postinfection with a single application of the gel alone or with gel formulations containing foscarnet and/or SLS. Among the untreated infected mice, no pathological signs of cutaneous lesions were seen during the first 4 days following infection, and only the scarified area remained apparent (Fig. 1A). On day 5, mice developed herpetic skin lesions in the form of vesicles distant from the inoculation site. On day 7, these vesicles became coalescent to form a zoster-like lesion along the affected dermatome. Mean lesion scores were maximal on day 8 and decreased thereafter from days 10 to 15 because of the spontaneous healing of cutaneous lesions in the surviving mice. Treatment with the polymer alone exerted no therapeutic effect. The topical formulation containing 3% foscarnet exerted a modest but significant effect on the development of herpetic skin lesions compared to the effect of no treatment and treatment with the gel alone (Table 1). Treatment of the mice with the polymer containing 10% SLS significantly reduced the mean lesion score, but treatment of the mice with formulations containing 1 or 5% SLS did not (Fig. 1B to D). Treatment of the mice with the gel containing 1 or 10% SLS in combination with 3% foscarnet gave results similar to those achieved by treatment with the formulation containing 3% foscarnet only. Of prime interest, treatment with the gel formulation containing 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS resulted in a marked and significant reduction in the mean lesion score compared to those for all groups tested. Among the untreated infected mice, 59% of animals died from encephalitis between days 7 and 12, whereas about 80% of mice treated with the gel plus 3% foscarnet, the gel plus 10% SLS, or the gel plus 3% foscarnet and 1, 5, or 10% SLS survived the infection (P < 0.001) (data not shown). Furthermore, no significant reduction of viral titers in skin samples from the inoculation site and from the lower flank (located between the inoculation site and the ventral midline) was observed following treatment with all the topical formulations tested (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Time evolution of the mean lesion scores for hairless mice infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F. (A) Mean lesion score for mice treated with the gel alone (○) or with the gel containing 3% foscarnet (●). Untreated infected mice (□) were used as controls. (B) Mean lesion score for mice treated with the gel containing 1% SLS (○) or 3% foscarnet and 1% SLS (●). (C) Mean lesion score for mice treated with the gel containing 5% SLS (○) or 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS (●). (D) Mean lesion score for mice treated with the gel containing 10% SLS (○) or 3% foscarnet and 10% SLS (●). Treatments were given as a single application 24 h after infection. Values represent the means for 17 animals per group pooled from three independent experiments (5 mice per group for the first experiment and 6 mice per group for the second and third experiments).

TABLE 1.

AUC of the time evolution of the mean lesion scores for mice treated 24 h postinfection with a single application of different gel formulations

| Treatment | AUCa |

P

value (compared to the results for the corresponding group)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | ||

| (a) None | 32.12 ± 0.97 | NSb | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | NS | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | |

| (b) Gel alone | 32.12 ± 1.18 | NS | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 | NS | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | |

| (c) Gel + 3% foscarnet | 26.24 ± 1.86 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | NS | |

| (d) Gel + 1% SLS | 27.94 ± 2.73 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | NS | |

| (e) Gel + 3% foscarnet + 1% SLS | 26.24 ± 2.35 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | NS | |

| (f) Gel + 5% SLS | 29.18 ± 1.85 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | NS | |

| (g) Gel + 3% foscarnet + 5% SLS | 14.38 ± 2.46 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| (h) Gel + 10% SLS | 26.24 ± 1.80 | <0.05 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | |

| (i) Gel + 3% foscarnet + 10% SLS | 24.65 ± 1.93 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NS | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | NS | |

Values are means ± standard errors of the means calculated as [(score on day 4 + score on day 10)/2] + sum of all scores between days 4 and 10.

NS, not significant.

Figure 2 shows the time evolution of the mean lesion scores for untreated infected mice and mice treated 24 h postinfection with a single application of solution or gel formulations of foscarnet and/or SLS. For mice treated with the buffered solutions of foscarnet that contained or that did not contain SLS, the evolution of the mean lesion score was slightly decreased compared to that for untreated infected mice (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Treatment with the gel formulation containing 3% foscarnet or 5% SLS reduced the level of development of herpetic skin lesions, which was similar to the effect of the drug administered in a buffered solution. Of prime interest, treatment with the polymer formulation containing 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS markedly reduced the level of development of herpetic skin lesions compared to the effect of no treatment (P < 0.01) and treatment with the polymer formulation of foscarnet (P < 0.05). Treatment of mice with a 3% foscarnet solution had no marked effect on the survival rate of animals compared to that for untreated infected mice (57 versus 35%; data not shown). A survival rate of 71% was obtained for mice treated with the combination of 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS in solution (P < 0.001), whereas 86% of mice treated with a gel formulation containing 5% SLS alone or in combination with 3% foscarnet survived the infection (P < 0.001). All mice treated with the polymer formulation containing 3% foscarnet survived the infection (P < 0.001).

FIG. 2.

Time evolution of the mean lesion score for hairless mice infected cutaneously with HSV-1 strain F and treated 24 h postinfection with a single application of buffered solution containing 3% foscarnet (○) or 3% foscarnet plus 5% SLS (▵) or with the gel containing 5% SLS (⧫), 3% foscarnet (●), or 3% foscarnet plus 5% SLS (▴). Untreated infected mice (□) were used as controls. Values represent the means for seven animals per group.

TABLE 2.

Effects of topical treatments on the development of herpetic cutaneous lesions in mice after a single application 24 h postinfection

| Treatment | AUCa |

P

value (compared to the results for the corresponding group)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | e | f | ||

| (a) None | 39.42 ± 1.06 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.01 | |

| (b) 3% foscarnet–buffer | 25.50 ± 4.23 | <0.05 | NSb | NS | NS | NS | |

| (c) 3% foscarnet + 5% SLS–buffer | 27.14 ± 4.58 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| (d) Gel + 5% SLS | 26.64 ± 2.76 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| (e) Gel + 3% foscarnet | 28.00 ± 2.60 | <0.05 | NS | NS | NS | <0.05 | |

| (f) Gel + 3% foscarnet + 5% SLS | 16.57 ± 4.92 | <0.01 | NS | NS | NS | <0.05 | |

Values are means ± standard errors of the means calculated as [(score on day 4 + score on day 10)/2] + sum of all scores between days 4 and 10.

NS, not significant.

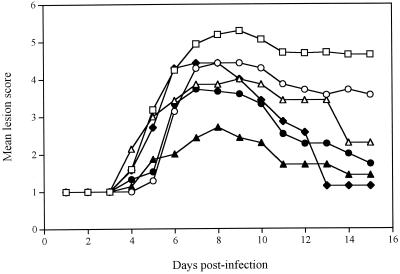

In vivo skin penetration studies.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of foscarnet in the skin tissues of uninfected and infected mice 24 h after its topical application either alone or in combination with SLS in the gel formulation. The amount of foscarnet in the stratum corneum tape strips of uninfected mice was significantly higher (P < 0.005) when SLS was incorporated in the polymer matrix. No or negligible amounts of foscarnet were found in the underlying epidermis and dermis of uninfected mice even when SLS was added to the gel formulation. The amount of drug recovered in the skin tissues of infected mice were systematically higher than those detected in uninfected mice. In infected mice, the concentration of foscarnet in the epidermis was higher when SLS was incorporated into the gel formulation, but the variability was high. Conversely, the concentration of foscarnet in the dermis of uninfected and infected mice was not influenced by the presence of SLS. Foscarnet was not recovered in the plasma of uninfected and infected mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Distribution of foscarnet in the tape strips of the stratum corneums of uninfected (open symbols) and infected (filled symbols) mice 24 h after the topical application of the gel containing 3% foscarnet (PFA; ○, ●) or 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS (▵, ▴). (B and C) Concentrations of foscarnet in the epidermis and dermis of noninfected (NI) and infected (I) mice, respectively. Values represent the means ± standard errors of the means for six animals per group.

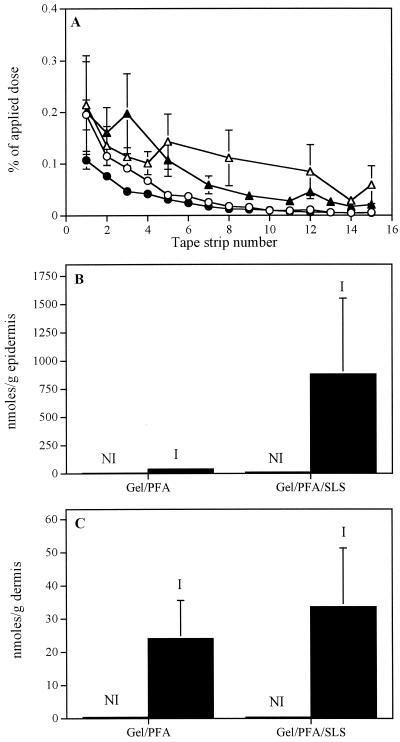

Virus inactivation.

Figure 4 shows that pretreatment of wild-type HSV-1 and of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV-2 strains with SLS for 1 h at 37°C decreased, in a concentration-dependent manner, their infectivities for Vero cells. Following pretreatment with 25 μM SLS, the infectivities of wild-type HSV-1 and acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV-2 strains were reduced to 9, 34, and 38% of control values, respectively. A complete loss of the infectivities for all strains tested was obtained following pretreatment of the viruses with 50 μM SLS.

FIG. 4.

Infectivities of wild-type HSV-1 strain F (□), acyclovir-resistant HSV-2 strain 6 (●), and foscarnet-resistant HSV-2 strain 15589 (○) pretreated with SLS for Vero cells. Cells were infected with viruses pretreated for 1 h at 37°C with increasing concentrations of SLS prepared in PBS. Infectivity was expressed as the percentage of PFU compared with that for cells treated with the control (to which SLS was not added). Results represent the average of triplicate incubations from one typical experiment of four experiments conducted.

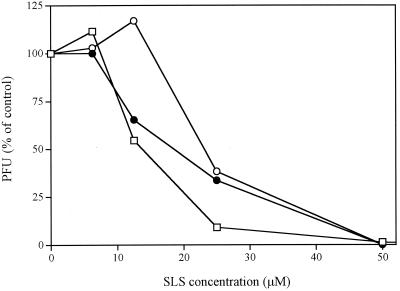

Inhibitory effect.

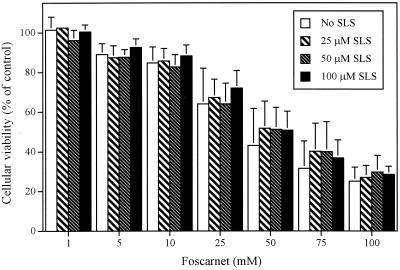

Table 3 shows the inhibitory effect of foscarnet, alone or in combination with SLS, on the HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect in Vero cells. The ED50 of foscarnet was 74.18 μM. The ED50 decreased to 30.10, 34.40, and 55.24 μM when foscarnet was combined with 12.5, 25, and 37.5 μM SLS, respectively. SLS alone also exerted an inhibitory effect on the HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect, with an ED50 of 65.30 μM. The ED50 was not modified when SLS was combined with 17 μM foscarnet, but it was decreased to 32.61 and 55.35 μM in the presence of 33 and 50 μM foscarnet, respectively. The inhibitory effects of combinations of both compounds on the virus-induced cytopathic effect were analyzed by the isobologram method. The FIC of SLS plus the FIC of foscarnet were between 0.87 and 1.82 for all combinations, indicating that combinations were subsynergistic to subantagonistic, depending on the concentration used. Figure 5 shows the effect of foscarnet alone or in combination with various concentrations of SLS on the viabilities of Vero cells. Foscarnet decreased the viabilities of Vero cells in a concentration-dependent manner. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of foscarnet for this cell line was 50 mM. Incorporation of SLS at a concentration up to 100 μM did not potentiate the toxic effect exerted by foscarnet. The CC50 of SLS for Vero cells was 275 μM (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Inhibitory effects of combinations of foscarnet and SLS on HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect in Vero cells

| Formulations | ED50 (μM)a | FICSLS + FICPFAa | Inhibitory effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foscarnet | 74.18 ± 4.73 | ||

| Foscarnet + 12.5 μM SLS | 30.10 ± 4.52 | 0.87 ± 0.14 | Subsynergistic |

| Foscarnet + 25 μM SLS | 34.40 ± 0.95 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | Subsynergistic |

| Foscarnet + 37.5 μM SLS | 55.24 ± 4.55 | 1.59 ± 0.14 | Subantagonistic |

| SLS | 65.30 ± 2.60 | ||

| SLS + 17 μM foscarnet | 63.33 ± 3.95 | 1.82 ± 0.12 | Subantagonistic |

| SLS + 33 μM foscarnet | 32.61 ± 2.36 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | Subsynergistic |

| SLS + 50 μM foscarnet | 55.35 ± 3.89 | 1.60 ± 0.12 | Subantagonistic |

Results are means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. FICSLS and FICPFA, FICs of SLS and foscarnet (PFA), respectively.

FIG. 5.

Viabilities of Vero cells incubated in the presence of foscarnet, alone or in combination with various SLS concentrations, for 24 h at 37°C. Results are expressed as the percentage of cellular viability compared with that for control cells (cells incubated in culture medium). Values represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

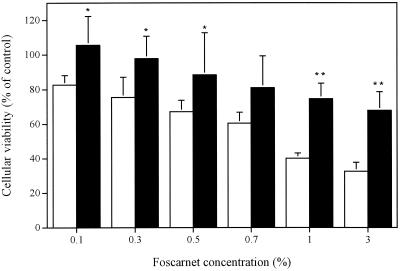

Cytotoxicities of gel formulations.

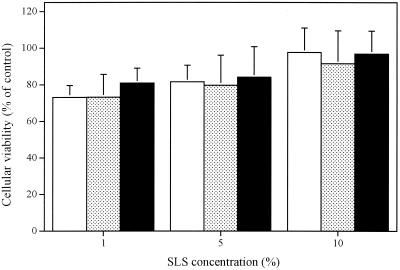

Figure 6 shows the influence of foscarnet in PBS or foscarnet incorporated in the polymer prepared in PBS on the viabilities of cultured human skin fibroblasts. Foscarnet also decreased the viabilities of these cells in a concentration-dependent manner. The CC50 of foscarnet for this cell line was 0.85% (28 mM). Thus, this cell line is susceptible to foscarnet at concentrations approximately twofold lower than those to which Vero cells are susceptible. Of prime interest, the incorporation of foscarnet into the gel formulation significantly decreased the cellular toxicity of the antiviral agent. Figure 7 shows that SLS in PBS or SLS incorporated into gel formulations containing or not containing 3% foscarnet did not markedly alter the viabilities of fibroblasts even at a concentration of 10% (347 mM).

FIG. 6.

Viabilities of cultured human skin fibroblasts incubated in the presence of foscarnet in PBS (□) or foscarnet incorporated into the gel formulation (■) for 24 h at 37°C. Results are expressed as the percentage of cellular viability compared with that for control cells (cells incubated in culture medium). Values represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. ∗, P < 0.05 compared to foscarnet in solution; ∗∗, P < 0.01 compared to foscarnet in solution.

FIG. 7.

Viabilities of cultured human skin fibroblasts incubated in the presence of SLS in PBS (□), SLS incorporated into the gel ( ), or SLS incorporated into the gel containing 3% foscarnet (■) for 24 h at 37°C. Results are expressed as the percent viability compared with that for control cells (cells incubated in culture medium). Values represent the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have evaluated the effect of SLS on the efficacies of topical formulations containing foscarnet against cutaneous HSV-1 infection in hairless mice. Foscarnet and/or SLS was incorporated into a polymer matrix composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene. A single application of the gel formulation containing 3% foscarnet given 24 h after infection showed modest efficacy against the development of herpetic skin lesions. The low level of efficacy of the foscarnet formulation can be attributed to the high anionic character of the drug, which limits its intracellular penetration, thereby restricting its efficacy (14). Of prime interest, the addition of 5% SLS to the foscarnet formulation resulted in a marked and significant reduction of the mean lesion score, whereas the addition of 1 or 10% did not improve the efficacy of the formulation containing the drug. In aqueous solutions, surfactants like SLS aggregate to form micelles. The hydrophobic moieties compose the core of the micelles and are shielded from the surrounding solvent by the shell formed by the anionic head groups. The size and polydispersity of SLS micelles increase with the surfactant concentration (2). Several investigators have reported that surfactants induce a concentration-dependent biphasic action with respect to alteration of skin permeability (2, 56). Indeed, at low concentrations, surfactants increase the permeability of the skin to many substances probably because they penetrate the skin and disrupt the skin barrier function, whereas the permeability of the skin decreased when higher surfactant concentrations (which are generally above the critical micellar concentration) were used. This could perhaps explain why we did not observe an increased efficacy when the SLS concentration was enhanced from 5 to 10%.

The better efficacy of the combination of 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS was observed only when compounds were incorporated into the polymer matrix. We have previously shown that a polymer composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene, a nonionic surfactant, formed micelles which are highly opaque to electrons when observed by electron microscopy (41) and that SLS formed mixed micelles with this polymer (unpublished data). Goldemberg and Safrin (23) have also reported a similar behavior for a mixture composed of polyoxyethyleneglycol and polyoxyethylated nonionic surfactant with SLS. This suggests that complexes or mixed micelles formed by SLS and the polymer may play a role in the better efficacy of the foscarnet formulation. In addition, since the corn cushions were removed approximately 24 h after application of the topical treatments, the efficacy observed may also result from a continuous contact with a depot of the gel formulation over the 24-h period.

Despite the marked efficacy exerted by the formulation containing both 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS on the development of herpetic skin lesions and survival rates, we could not observe any effect of the treatment on viral titers in skin samples. Similarly, treatment of mice with a gel formulation containing 5% acyclovir given only once 24 h postinfection decreased the development of herpetic skin lesions without any effect on viral titers (40). Klein et al. (26) also showed that topical treatment with phosphonoacetic acid started 2 days postinfection reduced the development of skin lesions without affecting significantly the virus titers in skin. Awan et al. (3) also reported that treatment of mice with 0.5% hydrocortisone in a zosteriform infection model with the adoptive transfer of immune cells caused an increase in the viral titers and an extended presence of infectious virus, while they observed a reduction of the clinical signs of cutaneous lesions. In our study, viral replication could be inhibited following topical treatments initiated 24 h after infection. However, because of the progressive decrease of the foscarnet concentration in skin tissues, remaining viruses or a supply of virus coming back from the ganglia may still replicate to reach titers similar to those observed in untreated infected mice on day 5 postinfection. Thackray and Field (52, 53) have described a rebound of infectious virus in tissues following cessation of therapy. In addition, it is well established that the clinical signs of the disease result from both cytolytic virus replication and the inflammatory response triggered by the presence of virus. This suggests that the decrease in the virus content that could occur soon after topical treatment may reduce the effects of one or both factors. However, it is important to mention that treatment of mice with a gel formulation containing 3% foscarnet, given three times daily for 4 days and initiated 24 h after the infection, exerted a marked effect on the development of cutaneous lesions and survival rates, as well as viral titers in skin samples (40).

An important point for consideration in the treatment of mucocutaneous infections is the delivery of adequate amount of drugs to the site(s) of infection (49). Despite the high degree of variability of foscarnet concentrations, the better efficacy of the polymer formulation containing 3% foscarnet and 5% SLS observed could be attributed to an increased penetration of the drug into the epidermis, which is actually the site of virus localization, as demonstrated by immunoperoxidase staining of viral antigen (41). Patil et al. (36) have reported that SLS diffuses mostly by a radial path when it is applied topically. The mechanism involves an increased lipid fluidity below the applied site, which allows SLS to diffuse rapidly in the radial path without necessarily increasing the amount of drug delivered transdermally. Diffusion by such a radial path may occur for foscarnet in the presence of SLS, leading to a better targeting of sites of viral replication, therefore explaining the better efficacy of this topical formulation. We have already shown that foscarnet concentrations measured in the epidermis and dermis were higher in infected than in uninfected tissues (40). This effect is probably due to the fact that the scarification and the zosteriform lesion led to a loss of integrity of the skin, thereby altering its barrier function. Although we have not measured the penetration of foscarnet into skin at 24 h postinfection, we may assume, on the basis of the observations described above, that the concentration of foscarnet at this time point would also have been higher in skin tissues of infected mice than in those of uninfected control mice due to the lesions induced by the scarification.

Incorporation of SLS into the polymer matrix exerted a modest effect on the development of herpetic cutaneous lesions but significantly increased the survival rate for the mice. Previous studies have demonstrated that the administration of potent polyclonal and monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibodies with high virus neutralizing activities also protects mice from death even when they are given 1 or 2 days after the infection (11, 32, 35, 47). Although the mechanism of action is not clearly understood, immunoglobulin G antibodies may participate in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent complement-mediated cytolysis (33, 47). Antibodies could also neutralize the infectivity of the virus released from dying cells, thereby preventing local and distant virus dissemination (28). In vitro studies revealed that pretreatment of herpesviruses with SLS decreased in a concentration-dependent manner their infectivities for Vero cells. Ward and Ashley have already reported that SLS inactivates rotaviruses at concentrations that are quite low and under very mild conditions (58). Most of the proteins of the outer shell remained associated with the virions, and the decreased adsorption may be an electrostatic effect due to the adsorption of SLS molecules on the virus surface (57). Recently, Howett et al. (24) have reported that SLS is a potent inactivator of HSV-2, human immunodeficiency virus, and human papillomaviruses. In that study, it was suggested that SLS denatures the capsid proteins of nonenveloped viruses, while both envelope disruption and denaturation of virus structural proteins occurred for enveloped viruses. Previous studies from our laboratory also showed that SLS is a potent inactivator of the infectivities of HSV-1, HSV-2, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains (42). SLS did not interfere with the binding of HSV-1 to Vero cells, but viruses were able to enter cells and to produce capsid shells devoid of a DNA core in the nuclei. The amount of the glycoprotein D gene produced in these cells remained unchanged compared to the amount produced in control cells, suggesting that SLS could interfere with the maturation of the virus. Our results showed that SLS inhibited the HSV-1 strain F-induced cytopathic effect in Vero cells probably by affecting newly synthesized viruses that come into contact with the SLS present in culture medium following their release from cells, therefore preventing a productive infection of new cells. Combination of foscarnet and SLS resulted in a subsynergistic to subantagonistic effect. Toxicity studies with Vero cells confirmed that the inhibitory effect observed was due to the effects of the tested compounds on the virus itself rather than on the cells.

Foscarnet in PBS decreased in a concentration-dependent manner the viabilities of cultured human skin fibroblasts. Alenius et al. (1) have reported that treatment of guinea pigs with a 3% foscarnet cream once daily for 4 days caused transient skin irritation in some animals. In addition, foscarnet excreted in the urine caused ulcerations of mucous membranes in the genital area (54). Our results have demonstrated that the gel has a protective effect against the toxicity of foscarnet. This suggests that the incorporation of foscarnet into the polymer formulation could reduce the apparition of irritations and ulcerations following topical administration of this drug. Gagné et al. reported a similar reduction of the toxicity of nonoxynol-9, a nonionic surfactant, for human cervical and colon epithelial cells as well as for the vaginal mucosa of rabbits following its incorporation into this polymer matrix (22). On the other hand, our results showed that 10% SLS incorporated in buffer or SLS in the gel formulation was nontoxic to human skin fibroblasts. The nontoxicity of SLS for cultured cells is supported by the fact that shampoos and toothpastes that contain 5 to 10% SLS are nontoxic for skin and/or mucosal surfaces.

In conclusion, our results showed that the incorporation of SLS into a polymer matrix composed of polyoxypropylene and polyoxyethylene containing foscarnet increased the efficacy of this drug administered topically and could represent a suitable formulation for the treatment of cutaneous or genital herpes infections, especially those caused by acyclovir-resistant strains. The incorporation of foscarnet into the gel formulation may also reduce the potential risks of skin irritation or mucosal ulcerations associated with the topical administration of this antiviral agent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from Infectio Recherche Inc.

We thank Guy Boivin and Rabeea F. Omar for constructive comments and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alenius S, Berg M, Froberg F, Eklind K, Lindborg B, Öberg B. Therapeutic effects of foscarnet sodium and acyclovir on cutaneous infections due to herpes simplex virus type 1 in guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:569–573. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attwood D, Florence A T. Surfactant systems, their chemistry, pharmacy and biology. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awan A R, Harmenberg J, Flink O, Field H J. Combinations of antiviral and anti-inflammatory preparations for the topical treatment of herpes simplex virus assessed using a murine zosteriform infection model. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1998;9:19–24. doi: 10.1177/095632029800900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba M, Ito M, Shigeta S, De Clercq E. Synergistic antiviral effects of antiherpes compounds and human leukocyte interferon on varicella-zoster virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:515–517. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry D W, Lehrman S N, Ellis M N, Biron K K, Furman P F. Viral resistance, clinical experience. Scand J Infect Dis. 1986;47:155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton S E, Munday P E, Kinghorn G R, van der Meijden W I, Stolz E, Notowicz A, Rashid S, Schuller J L, Essex-Cater A J, Kuijpers M H M, Chanas A C. Topical treatment of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infections with trisodium phosphonoformate (foscarnet): double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Genitourin Med. 1986;62:247–250. doi: 10.1136/sti.62.4.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns W H, Saral R, Santos G W, Laskin O L, Lietman P S. Isolation and characterization of resistant herpes simplex virus after acyclovir therapy. Lancet. 1982;i:421–423. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttke T M, McCubrey J A, Owen T C. Use of an aqueous soluble tetrazolium/formazan assay to measure viability and proliferation of lymphocyte-dependent cell lines. J Immunol Methods. 1993;157:223–240. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90092-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey L, Nahmias A J, Guinan M E, Benedetti J K, Critchlow C W, Holmes K K. A trial of topical acyclovir in genital herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1313–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206033062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crumpacker C S, Heath-Chiozzi M. Overview of cytomegalovirus infections in HIV-infected patients: current therapies and future strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis W B, Taylor J A, Oakes J E. Ocular infection with herpes simplex virus type 1: prevention of acute herpetic encephalitis by systemic administration of virus-specific antibody. J Infect Dis. 1979;140:534–540. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deffond D, Leger D S, Leveque J L, Agache P. In vivo measurement of epidermal lipids in man. Bioeng Skin. 1986;2:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker C, Ellis M N, McLaren C, Hunter G, Rogers J, Barry D W. Virus resistance in clinical practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12(Suppl. B):137–152. doi: 10.1093/jac/12.suppl_b.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusserre N, Lessard C, Paquette N, Perron S, Poulin L, Tremblay M, Beauchamp D, Désormeaux A, Bergeron M G. Encapsulation of foscarnet in liposomes modifies drug intracellular accumulation, in vitro anti-HIV-1 activity, tissue distribution, and pharmacokinetics. AIDS. 1995;9:833–841. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elias P M. Epidermal lipids, membranes and keratinization. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb05278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elias P M. Lipids and epidermal permeability barrier. Arch Dermatol Res. 1981;270:95–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00417155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis M N, Keller P M, Fyfe J A, Martin J L, Rooney J F, Strauss S E, Lerhman S N, Barry D W. Clinical isolate of herpes simplex virus type 2 that induces a thymidine kinase with altered substrate specificity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1117–1125. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engle J P, Englund J A, Fletcher C V, Hill E L. Treatment of resistant herpes simplex virus with continuous-infusion acyclovir. JAMA. 1990;263:1662–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlich K S, Jacobson M A, Koehler J E, Follansbee S E, Drennan D P, Gooze L, Safrin S, Mills J. Foscarnet therapy for severe acyclovir-resistant herpes virus type-2 infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). An uncontrolled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:710–713. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Froebe C L, Simion F A, Rhein L D, Cagan R H, Kligman A. Stratum corneum lipid removal by surfactants: relation to in vivo irritation. Dermatologica. 1990;181:277–283. doi: 10.1159/000247822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulmer A W, Kramer G J. Stratum corneum lipid abnormalities in surfactant-induced dry scaly skin. J Investig Dermatol. 1986;86:598–602. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagné N, Cormier H, Omar R F, Désormeaux A, Gourde P, Tremblay M J, Juhász J, Beauchamp D, Rioux J E, Bergeron M G. Protective effect of a thermoreversible gel against the toxicity of nonoxynol-9. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:177–183. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldemberg R L, Safrin L. Reduction of topical irritation. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1977;28:667–679. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howett M K, Neely E B, Christensen N D, Wigdahl B, Krebs F C, Malamud D, Patrick S D, Pickel M D, Welsh P A, Reed C A, Ward M G, Budgeon L R, Kreider J W. A broad-spectrum microbicide with virucidal activity against sexually transmitted viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:314–321. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones T J, Paul R. Disseminated acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus type 2 treated successfully with foscarnet. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:508–509. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein R J, Friedman-Kien A E, Kaley L, Brady E. Effects of topical applications of phosphonoacetate on colonization of mouse trigeminal ganglia with herpes simplex virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:65–68. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lampe M A, Burlingame A L, Whitney J, Williams M L, Brown B E, Roitman E, Elias P M. Human stratum corneum lipids: characterization and regional variations. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:120–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBlanc R A, Pesnicak L, Godleski M, Straus S E. Treatment of HSV-1 infection with immunoglobulin or acyclovir: comparison of their effects on viral spread, latency, and reactivation. Virology. 1999;262:230–236. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehrman S N, Douglas J M, Corey L, Barry D W. Recurrent genital herpes and suppressive oral acyclovir therapy. Relationship between clinical outcome and in vitro drug sensitivity. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:786–790. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-6-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leveque J L, de Rigal J, Saint-Leger D, Billy B. How does sodium lauryl sulfate alter the skin barrier function in man? A multiparametric approach. Skin Pharmacol. 1993;6:111–115. doi: 10.1159/000211095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marks G L, Nolan P E, Erlich K S, Ellis M N. Mucocutaneous dissemination of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus in a patient with AIDS. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:474–476. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKendall R R, Klassen T, Baringer J R. Host defenses in herpes simplex infections of the nervous system: effect of antibody on disease and viral spread. Infect Immun. 1979;23:305–311. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.305-311.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mester J C, Glorioso J C, Rouse B T. Protection against zosteriform spread of herpes simplex virus by monoclonal antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:263–269. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norris S A, Kessler H A, Fife K H. Severe, progressive herpetic whitlow caused by an acyclovir-resistant virus in a patient with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:209–210. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oakes J E, Rosemond-Hornbeak H. Antibody-mediated recovery from subcutaneous herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Infect Immun. 1978;21:489–495. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.489-495.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patil S, Singh P, Maibach H. Radial spread of sodium lauryl sulfate after topical application. Pharm Res. 1995;12:2018–2023. doi: 10.1023/a:1016220712717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patil S, Singh P, Sarasour K, Maibach H. Quantification of sodium lauryl sulfate penetration into the skin and underlying tissue after topical application, pharmacological and toxicological implications. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:1240–1244. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600841018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pechere M, Wunderli W, Trellu-Toutous L, Harms M, Saura J H, Krischer J. Treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpetic ulceration with topical foscarnet and antiviral sensitivity analysis. Dermatology. 1998;197:278–280. doi: 10.1159/000018014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pelosi E, Mulamba G B, Coen D M. Penciclovir and pathogenesis phenotypes of drug-resistant herpes simplex virus mutants. Antivir Res. 1998;37:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(97)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piret J, Désormeaux A, Gourde P, Juhász J, Bergeron M G. Efficacies of topical formulations of foscarnet and acyclovir and of 5% acyclovir ointment (Zovirax) in a murine model of cutaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:30–38. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.30-38.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piret J, Gourde P, Cormier H, Désormeaux A, Beauchamp D, Tremblay M J, Juhász J, Bergeron M G. Efficacy of gel formulations containing free or liposomal foscarnet in a murine model of cutaneous herpes simplex type-1 infection. J Liposome Res. 1999;9:181–198. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piret J, Lamontagne J, Bestman-Smith J, Roy S, Gourde P, Désormeaux A, Omar R F, Juhász J, Bergeron M G. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of sodium lauryl sulfate and dextran sulfate as microbicides against herpes simplex and human immunodeficiency viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:110–119. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.110-119.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichman R C, Badger G J, Guinan M E, Nahmias A J, Keeney R E, Davis L G, Ashikaga T, Dolin R. Topically administered acyclovir in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex genitalis: a controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:336–340. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sacks S L, Portnoy J, Lawee D, Schlech W, Aoki F Y, Tyrrell D L, Poisson M, Bright C, Kaluski J. Clinical course of recurrent genital herpes and treatment with foscarnet cream: results of a Canadian multicenter trial. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:178–186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schinazi R F, del Bene V, Scott R T, Dudley-Thorpe J B. Characterization of acyclovir-resistant and -sensitive herpes simplex virus isolated from a patient with an acquired immune deficiency. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986;18(Suppl. B):127–134. doi: 10.1093/jac/18.supplement_b.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaw M, King M, Bes J M, Banatvala J E, Gibson J R, Klaber M R. Failure of acyclovir cream in treatment of recurrent herpes labialis. Br Med J. 1985;291:7–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6487.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simmons A, Nash A A. Role of antibody in primary and recurrent herpes simplex virus infection. Virology. 1985;53:944–948. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.3.944-948.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spruance S L, Crumpacker C S. Topical 5 percent acyclovir in polyethylene glycol for herpes simplex labialis: antiviral effect without clinical benefit. Am J Med. 1982;73:315–319. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spruance S L, Freeman D J. Topical treatment of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infections. Antivir Res. 1990;14:305–321. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(90)90050-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spruance S L, Freeman D J, Seth N V. Comparison of foscarnet, acyclovir cream, and acyclovir ointment in the topical treatment of experimental cutaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:196–198. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svennerholm B, Vahlne A, Lowhagen G B, Widell A, Lycke E. Sensitivity of HSV strain isolated before and after treatment with acyclovir. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1985;47:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thackray A M, Field H J. Comparison of effects of famciclovir and valaciclovir on pathogenesis of herpes simplex virus type 2 in a murine infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:846–851. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thackray A M, Field H J. Differential effects of famciclovir and valaciclovir on the pathogenesis of herpes simplex virus in a murine infection model including reactivation from latency. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:291–299. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wald A, Mattson D, Schubert M A. Photo quiz. Foscarnet-induced genital ulcers. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:13. doi: 10.1086/515072. , 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wallin J, Lemestedt J O, Ogenstad S, Lycke E. Topical treatment of recurrent genital herpes infections with foscarnet. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17:165–172. doi: 10.3109/inf.1985.17.issue-2.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walters K A. Penetration enhancers and their use in transdermal therapeutic systems. In: Hadgraft J, Guy R H, editors. Transdermal drug delivery: developmental issues and research initiatives. Vol. 35. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. pp. 197–245. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ward R L, Ashley C S. Comparative study on the mechanisms of rotavirus inactivation by sodium dodecyl sulfate and ethylediaminetetraacetate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.6.1148-1153.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ward R L, Ashley C S. pH modification of the effects of detergents on the stability of enteric viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:314–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.2.314-322.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitley R J. Herpes simplex viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Chanock R M, Hirsch M S, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, editors. Fields virology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1843–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitley R J. Penciclovir/famciclovir: parent and child in the treatment of herpes virus infections. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 1994;3:759–761. [Google Scholar]