Executive summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need for well-functioning primary health care (PHC) into sharp focus. PHC is the best platform for providing basic health interventions (including effective management of non-communicable diseases) and essential public health functions. PHC is widely recognised as a key component of all high-performing health systems and is an essential foundation of universal health coverage.

PHC was famously set as a global priority in the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration. More recently, the 2018 Astana Declaration on PHC made a similar call for universal coverage of basic health care across the life cycle, as well as essential public health functions, community engagement, and a multisectoral approach to health. Yet in most low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), PHC is not delivering on the promises of these declarations. In many places across the globe, PHC does not meet the needs of the people—including both users and providers—who should be at its centre. Public funding for PHC is insufficient, access to PHC services remains inequitable, and patients often have to pay out of pocket to use them. A vicious cycle has undermined PHC: underfunded services are unreliable, of poor quality, and not accountable to users. Therefore, many people bypass primary health-care facilities to seek out higher-level specialist care. This action deprives PHC of funding, and the lack of resources further exacerbates the problems that have driven patients elsewhere.

Focus on financing

Health systems are fuelled by their financing arrangements. These arrangements include the amount of funding the system receives, the ways funds are moved through the system to frontline providers, and the incentives created by the mechanisms used to pay providers. Establishing the right financing arrangements is one crucially important way to support the development of people-centred PHC. Improving financing arrangements can drive improvements in how PHC is delivered and equip the system to respond effectively to evolving population health needs. Thus attention should be paid simultaneously to both financing and service delivery arrangements.

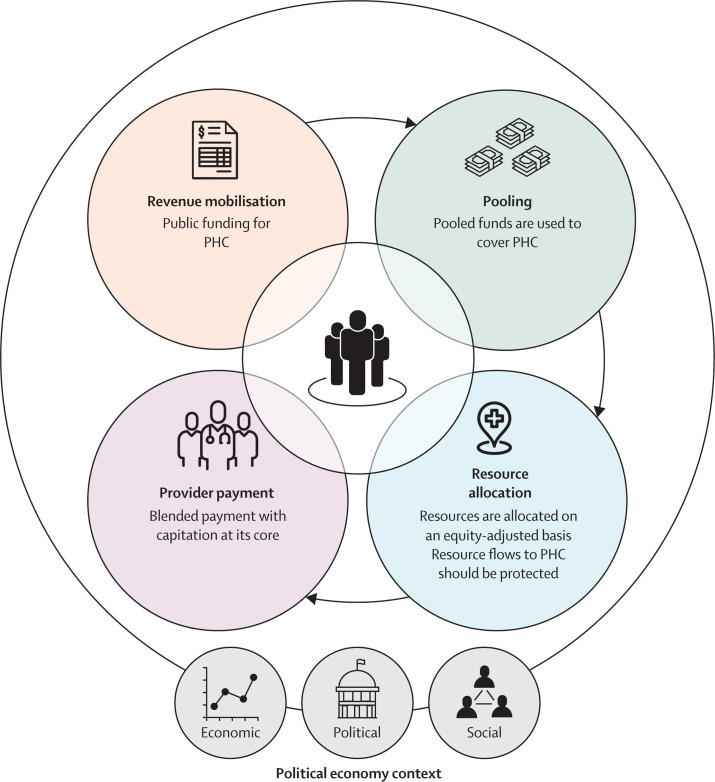

In this report, the Lancet Global Health Commission on financing PHC argues that all countries need to both invest more and invest better in PHC by designing their health financing arrangements—mobilising additional pooled public funding, allocating and protecting sufficient funds for PHC, and incentivising providers to maintain the health of the populations they serve—in ways that place people at the centre and by addressing inequities first.

Financing is political

Answering the question of how to make these changes goes far beyond technical considerations. Fundamentally shifting a health system's priorities—away from specialist-based and hospital-based services and towards PHC—involves political choices and creates numerous political challenges. Successfully reorienting a system towards PHC requires savvy political leadership and long-term commitment, as well as proactive, adaptable strategies to engage with stakeholders at all levels that account for the social and economic contexts. Therefore, this report addresses both technical and political economy considerations involved in strengthening financing for PHC.

Spending more and spending better on PHC

Despite broad recognition of the importance of PHC, there is no global consensus on what exactly constitutes PHC. This makes it challenging to measure and report on levels of expenditure on PHC. In this Commission we define PHC as a service delivery system or platform, together with the human and other resources needed for it to function effectively. We found that LMICs spend far too little on PHC to provide equitable access to essential services and that much of the (significant) variation in PHC spending levels across countries is explained by national income levels, although there is variation in the amount of government resources allocated to PHC at any given level of economic development. Furthermore, at every level of PHC spending, there is substantial variation in performance, suggesting that we need to spend better as well as spending more.

In this Commission, we analysed provider payment methods and found that the sources of PHC expenditure remain fragmented and overly reliant on out-of-pocket payments. Population-based provider payment mechanisms, such as capitation, should be the cornerstone of financing for people-centred PHC. However, these mechanisms are rare in LMICs, where input-based budgets are standard practice. Furthermore, many features of primary health-care organisation that are necessary for population-based payment strategies (such as empanelment, registration, and gatekeeping) are absent in LMICs.

Redressing these limitations to improving financing PHC is urgent, as new challenges continue to arise. As in other parts of the health sector, PHC will continue to become more integrated, digitally-driven, and pluralistic; therefore, PHC financing arrangements also need to evolve to support, drive, and guide these changes to better meet human needs.

The Commission takes the position that progressive universalism should drive every aspect of PHC. That means putting the rights and needs of the poorest and most vulnerable segments of a population first. This requires unwavering ethical, political, and technical commitment and focus. Together with this overarching principle, we identified four key attributes of people-centred financing arrangements that support PHC.

-

(1)

Public resources should provide the core of primary health-care funding. Revenue-raising mechanisms should be defined based on the ability to pay and be progressive. Out-of-pocket payments must be reduced to levels where they are no longer a financial barrier to accessing needed care, impoverish households, or push households deeper into poverty. In most LMICs, this level of public funding for PHC can only be generated through increased allocations to PHC from general tax revenue, and therefore requires an expansion of countries' taxation capacities. In low-income countries, more development assistance will be needed to expand the resource envelope for PHC.

-

(2)

Pooled funds should be used to allow all people to receive PHC that is provided free at the point of use. Only once universal coverage with PHC is achieved should pooled resources be extended to cover other entitlements. In this way, PHC can help fulfil the promise of universal health coverage.

-

(3)

Resources for PHC should be allocated equitably (across levels of service delivery and geographic areas) and protected as they flow through the system to frontline providers. Countries should deploy a set of strategic resource allocation tools (including a needs-based per-capita resource allocation formula and effective public financial management tools) to match primary health-care funding with population needs and ensure these resources reach the frontline, and prioritise the poorest and most vulnerable people.

-

(4)

Payment mechanisms for primary health-care providers should support allocation of resources based on people's health needs, create incentive environments that promote PHC that is people-centred, and foster continuity and quality of care. To achieve these goals, a so-called blended provider payment mechanism with capitation at its core is the best approach to paying for PHC. Capitation should form the core of the primary health-care financing system because it directly links the population with services. Combining capitation with other payment mechanisms, such as performance-based payments for specific activities, enables additional objectives to be achieved.

Each country is at a different point along its path towards the goal of effective financing for PHC. The four attributes outlined both represent goals and present a guide for working towards those goals. This Commission recognises that, depending on the context, the evolution of an effective primary health-care financing system in some countries might occur through incremental changes, whereas others can implement comprehensive reforms. Improving PHC financing can occur in response to bottom-up advocacy, top-down policy or, most likely, through a combination of grassroots and technocratic approaches. Political, social, and economic factors are therefore as important as technical design elements when it comes to enacting efficient and equitable primary health-care financing reform. Changing the ways in which PHC is financed requires support from a wide range of stakeholders, and deliberate political strategies, to determine and then stay the course. The change also requires good information about PHC resource levels and flows so that this reorientation can be effectively managed and monitored.

In this Commission, we provide five recommendations.

-

(1)

People-centred financing arrangements for PHC should have public resources provide the bulk of primary health-care funding; pooled funds cover primary-health care, enabling all people to receive PHC that is provided free at the point of service use; resources for PHC are allocated equitably across levels of service delivery and geographic areas, and are protected so that sufficient resources reach frontline primary health-care service providers and patients; and primary health-care provider payment mechanisms support the allocation of resources based on people's health needs, create incentive environments that promote PHC that is people centred, foster continuity and quality of care, and remain flexible enough to support rapidly changing service delivery models.

-

(2)

Spending more and spending better on PHC requires a whole-of-government approach involving all ministries whose remit interacts with health and requires the support of civil society. Key actors and stakeholders should be involved in designing and implementing financing arrangements for PHC that are people-centred. Although the specifics will vary depending on the national context, there are important roles and responsibilities for ministries of health, ministries of finance, local government authorities, communities and civil society groups, health-care providers and organisations, donors, and technical agencies.

-

(3)

Each country should plot out a strategic pathway towards people-centred financing for PHC that reflects the attributes outlined above, including investments in supporting basic health system functions. Technical strategies should be underpinned from the outset by analysis of the political economy.

-

(4)

Global technical agencies should reform the way primary health-care expenditure data are collected, classified, and reported to enable longitudinal and cross-country analyses of achievement of key primary health-care financing goals.

-

(5)

Academic researchers, technical experts, and policy makers, among others, should pursue a robust research agenda on financing arrangements for PHC that place people at the centre to support achievement of key primary health-care financing goals.

Introduction

Primary health care (PHC) is a key component of all high-performing health systems,1 an essential foundation for universal health coverage (UHC), and a prerequisite for meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. It is a pathway to achieving good health at low cost2 by providing essential and cost-effective health interventions, including health promotion; maternal, newborn, and child health care; immunisations; and treatment for common illnesses across the life course. As the global burden of non-communicable diseases increases, PHC is emerging as the locus of both prevention and the coordination of life-long management of chronic conditions. PHC also has an important role in providing essential public health functions, including responding to epidemic diseases such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

When successfully delivered, PHC serves as a key vehicle for fulfilling governmental and societal commitments. For example, primary health-care expansion improves equity when its services reach vulnerable segments of the population.3 Because primary health-care services are provided where people live and work,4 and because PHC focuses on population health, it can address many determinants of health that underpin various sources of vulnerability.5 PHC can protect households' financial wellbeing by fostering good health and reducing the risks of disease among breadwinners, caregivers, and other family members, and by averting the need for expensive secondary and tertiary health care.6 In fragile states and conflict-affected settings, primary health-care services can help build trust in the health system—and in the government it represents.7

A convincing economic case for PHC has been made repeatedly. Most of the available evidence comes from high-income countries. In these contexts, it has been shown that by providing key services at the lowest appropriate level of the health system, PHC can decrease the need for unnecessary hospital admissions, prevent avoidable readmissions, and limit inappropriate use of emergency departments.8 In low-income to middle-income countries (LMICs), an expanding body of evidence shows the cost-effectiveness of many interventions that are typically delivered through PHC. Indeed, a 2018 analysis classified 198 (91%) of 218 essential UHC interventions as PHC9 and another report estimated that up to 75% of the projected health gains from the SDGs could be achieved through PHC.10 Expanding a core set of integrated interventions for women's and children's health (narrower than PHC) is calculated to generate economic and health benefits in low-income countries valued at 7·2 times more than the costs; the value increases to 11·3 in lower-middle-income countries.11 A study of 67 LMICs projected that investing in PHC over the period from 2020 to 2030 would avert up to 64 million deaths.10

There is also a strong case for public investments in common goods for health, including public goods12 (which, in the economic sense, are services and functions that are both non-rival and non-exclusive), and in functions that generate strong positive externalities. These goods, which include the essential public health functions in PHC, require public funding as they are otherwise subject to market failure.

Yet despite its fundamental importance and incredible promise, PHC is not doing well in many countries, especially LMICs. The global community first proclaimed its commitment to multisectoral and integrated PHC in the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration. However, this commitment was quickly derailed, with funding and technical support flowing instead into vertical and disease-specific programmes.13 Despite periodic attempts to refocus on PHC, vertical programmes and hospital-based and specialist-based care models have regularly been prioritised over PHC. Funding for PHC is generally insufficient, access to primary health-care services remains inequitable, services are of inadequate quality, and patients often have to make out-of-pocket payments to use them. Health-care worker shortages persist, particularly in rural areas where the need is often greatest, and in many countries supplies of medicines, equipment, and other necessary commodities are grossly inadequate.6

This situation reinforces a cycle of neglect of PHC: when primary health-care services are unreliable, of poor quality, and not accountable to system users, it leads to poor uptake and low levels of trust in community-level health care. Users choose to bypass primary health-care services, which then receive even fewer resources. To successfully provide PHC at community level, national and local health-care systems need to be reimagined and restructured, beginning with placing the needs and preferences of people (including the intended users and providers) at the centre of the system design.6, 14

Health financing arrangements provide the fuel for health systems: they establish the amount of resourcing available and the way in which risks are shared among those who are ill and those who are well, the ways that funds flow through the system to frontline providers, and the payment systems that create incentives for providers. Together, these arrangements shape the equity, effectiveness, and efficiency of PHC.

This report focuses on how to get the financing arrangements right to serve and fuel effective, efficient, and equitable PHC service delivery. As will be discussed throughout the report, establishing the right financing arrangements for effective and equitable PHC can both support and drive other necessary transformations. This Commission contends that health financing arrangements for PHC—how to mobilise sufficient resources to support PHC objectives, how to ensure that resources reach frontline providers in ways that align with PHC objectives, and how to design financial incentives that encourage the delivery of, and access to, high-quality, equitable, integrated and efficient PHC—should be centred on people, and focused on equity. Panel 1 presents descriptions of two key terms that are used throughout the report: health financing functions and health financing arrangements.

Panel 1. Health financing functions and arrangements.

Three core health financing functions are mentioned throughout the report:

-

•

Mobilisation of funds: the collection of revenue (from taxes, insurance contributions, user fees, donations, or other means) that is used to pay for delivery of health services. Resource mobilisation is addressed in detail in section 3.

-

•

Pooling: accumulating prepaid funds (such as social security contributions, taxes, or health insurance premiums) to pay for health services for a group of people. Pooling is addressed in section 3.

-

•

Purchasing: the mechanisms by which mobilised and pooled funds are transferred to providers who deliver health services. Purchasing involves three elements: specifying what services will be purchased (often called the benefit package), identifying which providers are eligible to provide these services, and defining the set of arrangements through which providers are contracted to provide the services. How providers are paid to provide primary health care (PHC) is the focus of section 5.

We refer in the report to a number of different ways of paying PHC providers:

-

•

A line-item budget is when providers are given prospectively a fixed amount of funds to cover specific line items, such as medicines and utilities, for a period (usually a year).

-

•

A fee-for-service payment is when providers are reimbursed for each individual service provided.

-

•

A capitation payment is when providers are given a fixed per-person payment, determined and paid in advance, to deliver a defined set of services to each enrolled individual for a specified period of time.

-

•

A pay-for-performance system is when providers are given bonus payments (or penalties) for achieving service coverage or quality targets.

We use the broader term health financing arrangements to refer to both the core health financing functions and the ways in which they are organised and interact. These arrangements include the public financial management processes through which resources flow to frontline providers. Throughout the report we pay particular attention to:15

-

•

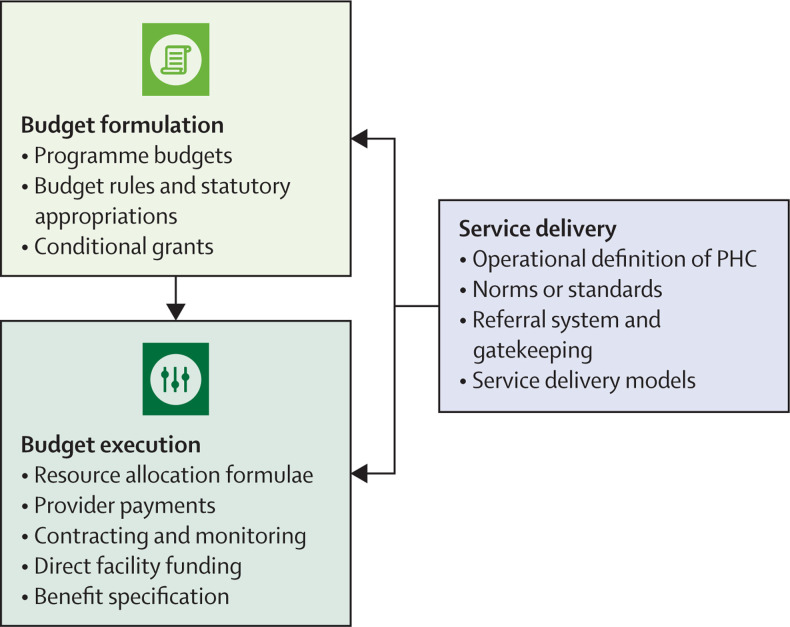

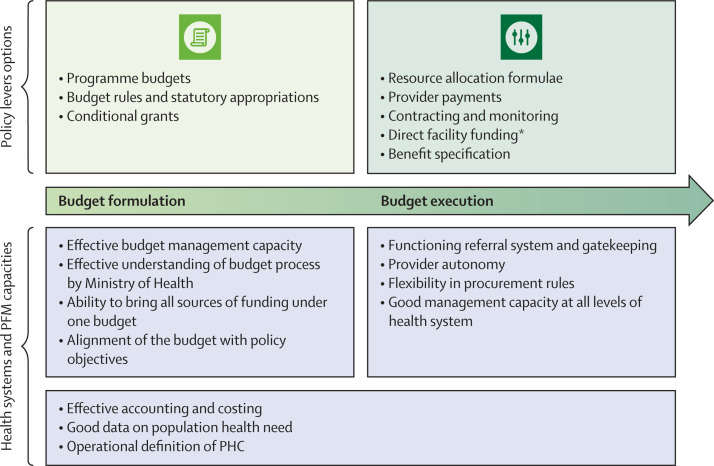

Budget formulation: the process of determining, soliciting, and securing sufficient public funding for PHC and the health system overall.

-

•

Resource allocation: the process of assigning available resources to specific uses (in this case, to PHC).

-

•

Budget execution: how the funds budgeted for services flow through the public system to providers.

In this Commission, we aimed to present new evidence on levels and patterns of global expenditure on PHC (throughout the report, the terms expenditure and spending are used interchangeably), including describing how PHC is currently organised and paid for; analyse key technical and political economy challenges faced in financing PHC; identify areas of proven or promising practices that effectively support PHC across the key health financing functions; and identify actionable policies to support LMICs in raising, allocating, and channelling resources in support of the delivery of effective, efficient, and equitable PHC that is people centred. Section 1 provides a general introduction to PHC policy and challenges. It then characterises global and national challenges, as well as opportunities, related to financing PHC. Section 2 describes the current financing landscape for PHC, detailing existing patterns of expenditure, provider payment, and related organisational features. Section 3 elaborates on mobilising sufficient resources for health through progressive means and then pooling resources to enable cross-subsidisation between those who are ill and those who are well. Section 4 focuses on how to ensure that resources mobilised for health are allocated to PHC, and emphasises the importance of engaging with the multiple budget tools available to Ministries of Health to ensure that resources reach frontline providers. Section 5 highlights the importance of structuring incentives for PHC providers so that they are motivated to provide PHC that is people centred, and proposes a strategic pathway of steps that countries can take to establish appropriate incentives. Section 6 describes the importance of, and notes strategies for, addressing the political economy of financing PHC. Finally, section 7 presents a synthesis of the vision for people-centred financing arrangements for PHC, summarises possible pathways for working towards this vision, and provides recommendations and proposes actions for different stakeholders committed to supporting LMICs to spend more—and to spend better—on PHC. It is the Commission's hope that this report will serve as a resource to policy makers around the world who are committed to this crucial endeavour.

We prepared this Commission through an extensive process of study and debate on good and promising practices in financing PHC. The 22 expert members, representing 19 nationalities, have amongst them experience working in national governments, technical agencies, bilateral and multilateral donors, universities, and independent think tanks. Assisted by a technical team based at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, Commissioners drew on the following sources of evidence: case studies prepared by national consultants on innovations in PHC financing in seven LMICs (Brazil, Chile, China, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, and Philippines) and three high-income countries (Estonia, Finland, and New Zealand); a compilation of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and WHO health expenditure data to conduct expenditure analysis; a new survey of PHC organisation and provider payment in LMICs; literature reviews, including systematic and scoping reviews, of existing knowledge on financing PHC; and an expert roundtable on digital technologies and PHC financing. Additional publications based on these products from the Commission are available on the Commission's website.

Section 1: Financing primary health care in the 21st century—challenges and opportunities

Defining PHC

In different contexts, PHC has been operationalised in different ways: as an approach to the delivery of health care that reorients the system away from hospitals and specialist care to practitioners working at community-level outpatient facilities; as a coordination mechanism which links primary care, community care, specialised care, wider public health interventions, and long-term care services;16 as a package of health services, often defined using cost-effectiveness as a primary criterion; as a service delivery level or platform, together with the human and other resources needed for it to function effectively; or as a system which combines a platform, a service package, and an approach that emphasises an orientation to meeting the needs of the population.

For the purposes of the Commission's health financing analyses, we found it necessary to link service delivery arrangements and orientations of PHC with the way resources are directed through the financing system to reach frontline providers. Resources typically flow to service delivery platforms. For this reason, PHC as a platform is our favoured operational definition of PHC. It typically includes both community-level and first-level health care. While it is true that some PHC services might be provided in hospital outpatient departments, it is the contention of this Commission that, over time, countries should aim to shift most PHC services out of hospitals to the appropriate community-level or first-level platforms where they can be delivered cost-effectively.

PHC is being transformed by new technologies that have the potential to overcome persistent challenges and radically change how people engage with health services. For example, digital technologies are streamlining procurement of commodities, improving supply chains, supporting health-care providers' adherence to clinical guidelines, and enabling tracking of patients who would otherwise be lost to follow-up.17, 18 New mobile and telemedicine technologies are helping patients to remotely access health information, medical advice, and their own health data. These technologies might help patients and their families to take greater responsibility for their own health and enable new, more horizontal relationships between patients and providers. Similarly, opportunities to pay insurance premiums digitally, such as via mobile phones, may help to mobilise additional financing for health. Technology-driven transformations bring some risks, including increasing health inequalities and fragmenting financing and delivery of care. However, they also offer avenues for making PHC more convenient, accessible, affordable, and high quality.

PHC will continue to evolve. For this evolution to fulfil the potential of PHC, health-care providers must expand their areas of focus and develop new skills, and health systems must develop new ways of delivering services across the life course, including incorporating preventive and supportive services. Innovations such as new digital and telehealth platforms must be deployed to support individuals and their families to manage their own health. Governments and communities must recognise and foster the role of PHC in essential public health functions, and PHC must engage with individuals and the wider community to co-produce forms of delivery that will meet people's needs. Appropriate use of technology will be key to support those delivering and those using services—eg, enabling task shifting between different cadres of health workers and delivering care that is flexible and closer to people's homes.

COVID-19: changing the context and highlighting lessons for PHC

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the need for PHC that is well financed into sharp focus in several ways:

-

•

It underscores the relationship between health and the economy. In particular, it has highlighted that failing to invest in health, including PHC, can have dramatic economic consequences.

-

•

Countries with stronger PHC systems were able to respond faster and more effectively to the pandemic.19, 20, 21 For example, Japan, Vietnam, and South Korea were better prepared to carry out COVID-19 surveillance because they were able to capitalise on existing public health capacity for contact tracing.22 Close partnerships between multidisciplinary PHC providers and local governments allowed rapid responses by reassigning roles while still maintaining other public health services, as seen in France23 and Catalonia, Spain.24 This shows that PHC systems provide a foundation for effective management of health crises.

-

•

The PHC system is a good platform for public health measures to control infectious diseases. The pandemic brought renewed attention to the vital importance of common goods for health,25 including the essential public health functions that are a component of PHC. Essential public health functions include surveillance systems, test-and-trace systems, quarantine functions, and vaccination.

-

•

Going forward, COVID-19 can only be overcome through action at the PHC level. For example, COVID-19 vaccinations will be provided through PHC platforms as provision shifts from a vertical campaign mode to a routine service. Management of mild-to-moderate illnesses related to COVID-19 will also be through PHC.

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated service delivery changes that were already underway. In particular, health care has rapidly adjusted to incorporate remote consultations, ramped-up support for home care, task shifting to lower-level cadres and structures, and expanded digital monitoring of health status, among others.

-

•

Above all, by highlighting the structural inequalities that exist within and across countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised the need to work for equity, solidarity, and social justice for all—these principles are central to the PHC approach.

Many of these lessons were highlighted in previous health emergencies, such as the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. However, the global scale of COVID-19, with its accompanying global and national responses, have conclusively shown that health issues can be made a top priority and that rapid changes to health systems and financing are possible. Governments and international funders alike created new flexibility in health financing arrangements, including rapid budget reallocations, mobilisation of new funds, and use of flexible purchasing arrangements. Some of these new arrangements should be retained and expanded. However, they have also exposed new areas of financial risk and vulnerability, as well as highlighting the need to continually focus on transparency and accountability.26

COVID-19 has shown that the need for well-financed, well-functioning PHC has never been greater. Yet many aspects of the pandemic response have instead led to a greater concentration of resources on hospital care, vaccines, and other so-called silver-bullet approaches27, 28 instead of prioritising basic public health interventions such as test-and-trace, disease surveillance, and population-based preventive measures.

This presents real risks to PHC financing and delivery. The financing requirements of the response to COVID-19 (both by the health system and in the economic response) have placed unprecedented pressure on government budgets, while spending capacity has decreased due to declines in revenue and borrowing.29 For example, the immediate financing needs for additional funding for COVID-19 prevention, treatment and surveillance in sub-Saharan African countries were estimated at about 3% of gross domestic product (GDP), or US$53 billion.30 At the same time, the International Monetary Fund estimated that economies around the world contracted in per-capita terms by an average 5·9% in 2020 as a result of COVID-19,31 driving an untold number of households into poverty and reducing their ability to pay for health care.

Spending on routine health services has fallen in many countries32 and generating more public resources for PHC will be challenging under conditions of fiscal restraint. In 90% of 105 countries surveyed by WHO, the pandemic badly disrupted many essential services that were not directly related to COVID-19, particularly mental health and reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health care.33 Among 22 low-income countries, ten (45%) reported disruptions in at least 75% of essential services—this represents far more disruption than was reported in LMICs (30%) and upper-middle and high-income countries (8%).34 In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, by October, 2020, up to 33% of the health budget had been redirected to the COVID-19 emergency response.33 Detailed accounts of the effect of COVID-19 on health financing in two other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Sierra Leone, and South Africa, can be found in the appendix (p 2).

The COVID-19 pandemic has thus shifted the landscape of possibilities for financing people-centred PHC in particular and health more broadly. Although it generated some new opportunities, it also created vast new challenges—and provided a glimpse of the potential havoc that future crises (health and otherwise) can create, and the consequences of not prioritising equity.35 Health financing systems need to be resilient to allow the surge capacity needed to respond to shocks while maintaining access to essential services.

Determining PHC packages

To examine and operationalise financing arrangements for PHC requires clarity on what services are being financed. The PHC package can be conceptualised at three levels. At the highest level, each government and national health system must articulate its own vision for comprehensive PHC that addresses its population health needs. Fulfilling a stated vision requires drawing on resources from both public and private sources. The Alma-Ata Declaration's vision of PHC also encompasses contributions from other sectors to address social determinants of health. In this report we focus on choices made within the health budget but recognise the need to identify mechanisms for securing contributions from outside the health sector, including education, water, and sanitation. At the benefit package level, each government and health system must identify which services it can afford to provide either for free or with partial coverage. In many low-income settings, external funds will be needed to augment government financing. At the provider payment level, each health system must determine which services it will pay providers for, at what level of payment, and via which provider payment mechanism (see section 5). Vertical programmes that provide some PHC services might be excluded from this payment system.

The specific PHC package that is financed and delivered in any particular setting will be determined by a country's (or region's) fiscal capacity, population health needs, and political decisions about priorities. It must include both population-based essential public health functions and personal health services. Cost-effectiveness criteria should inform these choices, but a pragmatic approach is needed when combining services at an operational, or service delivery platform, level.

PHC finance and delivery are linked

Directing resources to certain levels, structures, and providers makes it possible for them to function—and it also strengthens them so they can continue pulling and absorbing resources for appropriate and effective care. Conversely, inappropriate health financing arrangements can constrain effective care, and drive users to seek services that should be offered as PHC from higher levels of the system or from unregulated providers.

Getting financing functions right is important. But numerous countries' experiences have shown that PHC financing reforms work best when the organsation of PHC delivery is improved at the same time. This might be done by, for example, creating new cadres of health worker, or by incentivising multidisciplinary team approaches. Organisational reforms both enable the absorption of additional resources and make PHC more people centred. We therefore argue that countries need to address financing levels of PHC, financing arrangements, and delivery structures at the same time.

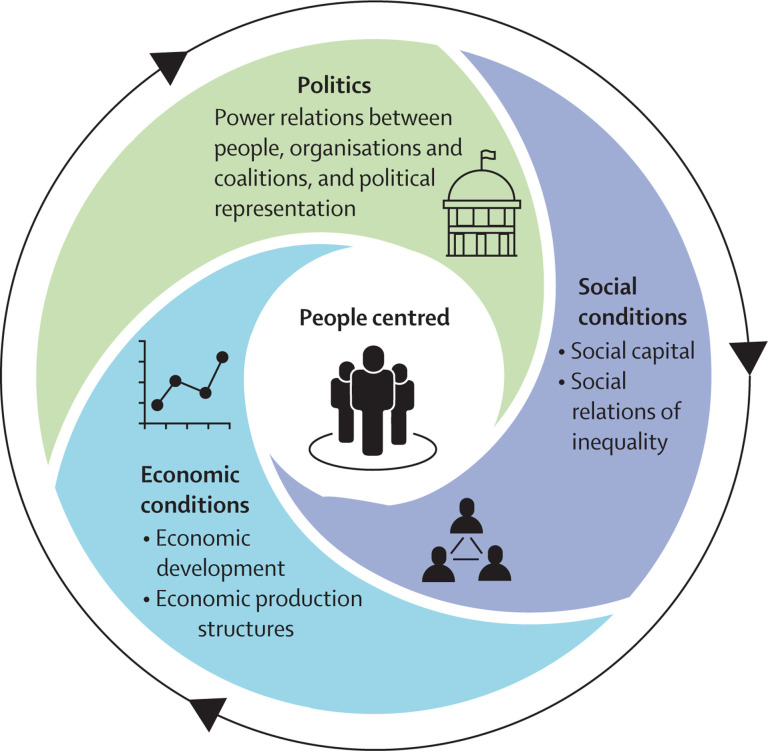

Financing is political

Designing financing arrangements is more than just a technical challenge—it also involves choices that are inherently political, in the broad sense of the term. Political, socioeconomic, and cultural conditions are part of the context in which PHC financing reforms take place and are integral to whether and how reform occurs.

Increasing the allocation of resources to health might require taking resources away from other sectors. It might also necessitate changing the roles of hospitals so they are more supportive of PHC and share responsibility for population health. Strengthening financing arrangements for PHC to better reach frontline providers and communities should mean that as resources increase, the relative distribution of resources and power will favour PHC providers compared to hospitals and specialists to ensure improvements in PHC services. Such shifts are complex because they run counter to political pressures that often favour investing in readily visible improvements, such as building facilities and reducing hospital waiting times. Whether changes are instituted as top-down radical changes or via bottom-up incremental modifications, they require shifts in power and influence at all levels.

In all cases, leaders pushing to change PHC financing must attend to the political economy of PHC financing reform (including making the political case for change and building the coalitions to enact it). Political economy considerations are woven throughout the report, and section 6 specifically addresses political economy analysis for PHC financing reform.

Building on strong health system foundations

Financing is only one, albeit an important, element of well-functioning health systems. It strongly influences, and is influenced by, other key health system building blocks. Having these other building blocks in place is crucial. These include governance arrangements that support delivery of people-centred PHC; a health workforce that is trained and supported to provide high-quality care; data, monitoring, evaluation and learning systems to capture and disseminate accurate health and spending information; functioning procurement and distribution supply chains for medicines and other commodities; and public finance management systems supporting every aspect of financing and delivery.

Financing community health and community health workers

The Commission has not differentiated between PHC and community health—an area that of late attracts substantial donor funding, particularly for the deployment of community health workers.36 Indeed, community health systems can be considered an advanced form of PHC implementation, where care takes place in the communities where people live and work. These platforms also present additional opportunities for deployment of new technologies. Although community health is arguably more focused on accountability and health service delivery in the context of the community (however defined), it still depends on trained staff, supplies, infrastructure, administrative processes, and integration with higher levels of care. Community health cannot exist outside the systems underpinning PHC, and must ultimately be financed on budget through the same mechanisms recommended elsewhere in this Commission. Although some governments or donor-funded programmes might separate community health activities in the context of PHC,36 others will integrate community health workers with their clinical personnel. What is most important is recognising the shared goal of universal access to primary care services and essential public health functions also prioritised by this Commission.

A key financing policy choice is whether and how to pay community health workers. Securing sustainable financing for community health worker programmes can be a challenge, particularly as in many countries these rely on external funding.37 Debates about paying community health workers typically focus on the trade-offs between reliance on volunteerism underpinned by intrinsic motivation of volunteers and the need to recognise and remunerate work fairly (and in doing so, addressing gender disparities, as most of the community health worker workforce is female).38, 39 Section 5 includes a brief summary of the evidence on paying community health workers.

The private sector and PHC

In many LMICS, the private sector is an important source of PHC provision.40, 41 Policy makers frequently express a desire to work with the private sector. However, the term private sector covers a heterogeneous set of providers, ranging from faith-based non-profit facilities that are well integrated into national health systems, to professionally trained clinicians operating private practices, to informally or untrained providers providing unregulated, low quality, even dangerous care. As noted, the Commission contends that universal PHC must rely predominantly on pooled public funds—but this does not preclude engaging with the private sector. Indeed, public financing mixed with private provision is widely adopted in OECD countries, where private providers are the main mode of provision of primary care in half of countries.42

Integrating the private sector into PHC platforms requires mechanisms to channel public funds to the private sector through purchasing arrangements. This pathway requires effective regulation, contracting capacity, and a broader set of purchasing institutions, including accreditation. In low-income countries, where informal private providers predominate and the public sector has insufficient resources for administering effective strategic purchasing and oversight, the best policy option is likely to be to start by providing good quality and affordable services in the public sector, while progressively strengthening regulation and professional bodies and collaborating with the private sector to develop referral pathways, training and qualification, and integration of clinical data.43 As both the public and private sectors develop greater capacities, the private sector can contribute to broader PHC functions, including public health surveillance and other essential public health functions, civil registration processes, the health management information system, and outbreak management.

Section 2: The landscape of financing and organisation of PHC

Analysing PHC expenditure

This section sets the scene for the rest of the report by presenting data on several topics: how PHC is currently financed, how PHC providers are paid, and some of the features of how PHC is organised that are particularly relevant to financing arrangements. Key messages from this section are presented in panel 2 .

Panel 2. Primary health care (PHC) financing landscape–key messages.

-

•

Despite the prominence of PHC in political commitments and policy statements, limited information is available on levels of, or trends in, financial resources for PHC. Different methods of calculating PHC spending are used, making it hard to compare expenditure data from different sources.

-

•

Annual government spending on PHC is $3 per capita in low-income countries and $16 per capita in lower-middle-income countries, which falls far short of any commonly used benchmark of the minimum amount needed to provide a basic package of health services.

-

•

Much of the variation across countries in estimated spending levels on PHC can be explained by national income level. However, there is also substantial variation in government spending on PHC among countries at similar income levels.

-

•

Higher levels of spending on PHC are generally associated with higher levels of service coverage. However, at any given spending level, there is substantial variation in performance, indicating that there is a need to spend better, as well as to spend more, on PHC.

-

•

Financing of, and spending on, PHC are fragmented. Governments typically invest in outpatient services, donor funding is used for prevention, and nearly half of private spending (most of which is out of pocket) is on medicines. Although external funds are an important source, particularly in low-income settings, that augment government and out-of-pocket expenditures, they can also cause fragmentation.

-

•

Out-of-pocket spending on PHC remains unacceptably high, particularly in low-income countries, continuing to expose households to financial risk.

-

•

The most common method for paying public providers for PHC in low-income to middle-income countries is input-based budgets. Capitation-based payment systems for PHC are rare in low-income to middle-income countries.

-

•

Public providers have little autonomy over their spending, which limits their efficiency and responsiveness.

To prioritise PHC expenditure, it is first necessary to measure what is currently spent. Empirical spending data allow policy makers to track existing expenditure, show how funds are currently being used, and make a case for increased commitments. Without data, it is hard to steer health systems toward stated goals, including equity, and even harder to track progress.

The first challenge: defining PHC for financing analysis

Analysing the financing arrangements for PHC requires clarity about what is (and what is not) part of PHC. Measuring PHC spending is challenging for numerous reasons, beginning with the breadth of the definition of PHC. As noted in section 1, PHC can include functions outside the health sector. Yet for conceptual and practical reasons, the current standard framework for tracking all financial resources for health in a country restricts the boundaries of health spending to the health sector itself. This framework, the System of Health Accounts, does refer (eg, through memorandum items for health promotion with a multisectoral approach) to expenditures by other sectors that clearly contribute to health, such as water and sanitation, but data on spending in these areas are not collected systematically.

Even within the health sector, there is no clear consensus on how to operationalise the definition of PHC in a robust expenditure monitoring exercise. The System of Health Accounts does not include a designated category for reporting spending on PHC.44 Instead, it classifies health spending in various ways, including by type of provider and by type of health-care service. In practice, most countries' definitions of PHC cut across these two classifications. Furthermore, the level of detail possible in System of Health Accounts reporting does not allow for accurate tracking of expenditure through to PHC services; instead System of Health Accounts measures rely on proxies derived from reported aggregates. For example, some countries do not distinguish expenditure on general outpatient services from that on specialised outpatient services, so their PHC expenditure estimates include both. The System of Health Accounts also does not distinguish among different levels of hospital care; however, in many countries district hospitals are part of PHC, while tertiary care is provided at centralised or regional hospitals. When used to estimate PHC expenditure, such approaches can give an impression of relatively high levels and shares of PHC spending. Panel 3 describes three countries' different approaches to organising PHC, and how the differences are reflected in expenditure tracking.

Panel 3. Three countries' approaches to defining primary health care (PHC).

Despite the existence of a global expenditure classification system, countries vary considerably in their models and conceptualisation of PHC, including how PHC spending is measured. Three examples, Thailand, South Africa, and the UK, are presented to show the breadth of this variety.

Thailand *

In Thailand, PHC is defined differently in rural and urban areas. PHC in rural areas includes all services provided by the District Health Systems Network, which is comprised of public subdistrict health centres and district hospitals (each of which serves a catchment of approximately 50 000 people). The District Health Systems Network is the first entry point to PHC for all people living in rural areas and provides a comprehensive range of services throughout the life course, including health promotion, disease prevention, and primary care services. It also provides public health functions, such as disease surveillance and response, and home visits, and supports multisectoral action to address social determinants of health and empower citizens and communities. In urban settings, meanwhile, PHC is less well-developed and most of the population uses hospital outpatient care directly, without any gatekeeping. In these settings, PHC is provided by the public and private hospital-based outpatient departments that provide a comprehensive range of primary care services similar to the District Health Systems Network.

Based on these definitions, the Thailand National Health Account estimates PHC expenditure as the sum of general and dental outpatient curative and preventive care provided at subdistrict health centres, and at public and private hospitals.45 Between 2015 and 2019, total PHC spending was 38% to 40% of current health expenditure. About 60% of PHC spending was financed by three public-health insurance schemes. Household out-of-pocket payments represented between 4% and 7% of PHC spending, as the publicly-covered benefit package is comprehensive and medicines are fully subsidised. Per capita PHC spending increased from US$85·7 in 2015 to US$114·8 in 2019.

South Africa

In South Africa, a uniform budget structure for the country's health programming was designed to specifically designate subprogrammes for PHC. The classification system is standardised across provinces and districts. Overall, South Africa spent US$92·9 per capita on public sector PHC in 2019–20. The five main subprogrammes of PHC comprise 18·8% of provincial health expenditure. South Africa also has a large, separately designated, HIV and AIDS subprogramme that adds an additional 10·4%, bringing total PHC expenditure to 32·3% of public health expenditure, or 1·3% of gross domestic product. This budget subprogramme classification differs somewhat from the WHO and System of Health Accounts 2011 classification system: the 2016–17 National Health Accounts for South Africa showed PHC represented 28% of government health expenditure.

UK

The National Health Service (NHS) in the UK describes PHC as “the first point of contact in the health care system, acting as the ‘front door’ of the NHS”. PHC is most closely linked to doctors in general practice, but also covers dentists, opticians, and pharmacists. Other professionals, such as nurses or physiotherapists, might also be part of a PHC team. Most primary care providers in the UK operate as independent contractors for the NHS. A range of services are contracted and financed through various models such as the General Medical Services or Personal Medical Services, Alternative Provider Medical Services, and Primary Care Trust Medical Services. According to the 2019–20 Annual Report and Accounts of the Department of Health and Social Care, primary care accounted for £12·6 billion (8·6%) of the total gross government expenditure on health of £145·27 billion. Prescribing costs, tracked separately, amounted to an additional £8·5 billion.

Many countries' expenditure reporting systems are inadequate for tracking expenditure on PHC. Although both OECD and WHO use the System of Health Accounts 2011 framework to track total health spending, only OECD collects disaggregated health spending (based on both the health-care function and provider classifications) for its 34 high-income-country members. WHO began tracking health spending based on health-care functions in 2016, but does not report health spending classified by provider. In 2016, WHO reported PHC estimates for 93 countries, increasing to 98 countries in 2018 (the most recent data available). Furthermore, breakdowns of public and private spending are only available in the WHO database for 57 countries in 2016, and 61 in 2018. Both the availability and the reliability of expenditure data on PHC in LMICs remain inadequate because of underinvestment in resource tracking systems, as well as the complexity of defining and tracking expenditure on PHC.6

Finally, different international bodies and countries compile PHC expenditure using different definitions (panel 4 ). Not only is there no agreed-on approach to estimate spending on PHC, but there is also no single database that provides globally comparable data for analysing PHC expenditure.

Panel 4. Working with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and WHO definitions of primary health-care (PHC) expenditure to construct an expenditure database on PHC.

To prepare our landscape analysis of PHC expenditure across countries, the Commission needed to combine data from various sources, considering different definitions and assumptions. We focused on two key sources: OECD46 and WHO.47

The OECD definition of PHC begins with expenditure on basic health care services derived from the health care function (HC) classification (namely, the sum of spending on general outpatient curative care (HC131), outpatient dental care (HC132), home-based curative care (HC14), and preventive care (HC61-HC64).48 An extended option also includes spending on pharmaceuticals. PHC expenditure is defined as expenditure on these services, limited to those delivered by ambulatory care providers derived from the health provider classification. WHO's definition of PHC uses only the HC classification. It starts with the same basic health care services in OECD's definition, and adds four additional components:

-

•

Curative outpatient care not elsewhere classified (HC13).

-

•

Outpatient and home-based long-term health care (HC33 and HC34).

-

•

80% of medical goods provided outside health care services (HC5). Because HC5 also includes inpatient-related medicines purchased outside health care facilities, the 80% share is an assumption aimed to capture just the PHC element.44

-

•

80% of health system administration and governance expenditure (HC7); this is included to represent the share of administrative expenditures related to policy and implementation costs for population-based public health interventions.

Because the WHO definition includes spending on hospital-based general outpatient care, pharmaceuticals, and administrative costs, the OECD definition is a subset of the WHO definition. Therefore expenditure levels estimated using the OECD definition will always be lower.

The Commission's definition

The Commission used a definition of PHC expenditure based on the WHO definition to compile the data presented below. However, we excluded the administration and governance expenditures. This brings our definition closer to that used by the OECD and limits additional arbitrary assumptions. We are not suggesting that administration and governance are not important for PHC; rather, we believe that these inputs are better captured outside the direct measurement of PHC spending. The inclusion of administration costs disproportionately biases estimates of PHC in low-income countries upwards. Even with this restriction on the definition of PHC spending, our estimates have been calculated using a broad definition of PHC that does include some hospital care. Therefore, our estimates should be seen as an upper bound estimate.

Details on how we combined data from the WHO and OECD databases to increase the number of countries we covered are presented in the appendix (p 5).

Definitions matter. They signal what is prioritised and valued, and they shape norms regarding how services should be organised. They also influence how data are collected and presented. There is a trade-off between using a simple global definition and accounting for country-specific definitions to permit more accurate reporting. In these early days of PHC expenditure reporting, what is most crucial is for each country to choose a way of operationalising PHC expenditure estimates so it can track its progress. Eventually, however, a consistent definition across countries will be needed to allow for cross-country comparisons and global monitoring of expenditure on PHC.

In generating our estimates of current levels of PHC expenditure, this Commission was constrained by both the levels of current reporting and the definitions used by the organisations that compile data.

The Commission's method of calculating PHC expenditure

The Commission's approach to measuring expenditure on PHC is presented in panel 4, along with the thinking behind it. For the purposes of tracking expenditures on PHC in the future, this Commission favours using an operational definition based on service delivery platforms for PHC: population-based public health services, community health services, health centres, and first-level hospitals. This is because financing arrangements typically channel resources to providers and platforms, rather than to interventions or services. We also take the normative position that PHC should not be delivered through higher-level hospitals, because improving financing arrangements should focus on driving resources to and supporting use at the appropriate level of care, which brings services as close as possible to people and delivers them at the lowest cost. To estimate PHC expenditure using a platform-based approach requires data that cross-classify between health care function and provider category. However, because currently available data from WHO are only reported by health-care function, we are limited to estimating PHC expenditure using a service-based (rather than a platform-based) approach. We also made some modifications to the PHC expenditure reported by the WHO for the purposes of our analysis (panel 4).

WHO reported data on total PHC spending on 98 countries for 2018 and government spending on PHC on 61 of these. We observed that the WHO database did not provide data on government spending on PHC for all OECD countries. In order to compare spending levels in high income countries with those in LMICs, we constructed PHC expenditure for OECD countries from data on expenditure by financing scheme, using expenditure by government and compulsory schemes to proxy for government spending on PHC. We used exchange rate data from the Global Health Expenditure Database to convert the raw data from local currency. With the addition of reconstructed government spending on PHC per capita from the OECD database following the WHO definition, the total number of countries providing data on government spending on PHC increased to 90 countries.

Levels of financing for PHC

Despite data limitations, our analyses have identified some notable patterns in the levels and sources of PHC spending across countries. Table 1 presents overall health expenditure data by country income group for 2018. The table shows that total expenditure on PHC in low-income countries is $24 per capita and in lower-middle-income countries it is $52 per capita. Government spending on PHC is even more meagre, at $3 in low-income countries and $16 in lower-middle-income countries, which falls short of the WHO estimate of the per capita recurrent cost for PHC of $65 in low income countries and $59 in lower-middle income countries10 (section 3). Although the share of government health spending allocated to PHC is similar in LMICs and high-income countries, government spending on PHC as a share of total PHC spending is lower in low-income countries than in high-income countries and the same is true of the share of government PHC spending in relation to GDP.

Table 1.

|

Level of spending per capita (US$) |

Share of spending (%) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Total) Current health spending | Domestic general government expenditure on health | Total PHC spending | Domestic general government spending on PHC | Out-of-pocket spending on PHC | External spending on PHC | PHC spending as a share of current health spending | Domestic general government spending on PHC as a share of total PHC spending | Domestic general government spending on PHC as a share of GDP | Domestic general government spending on PHC as a share of domestic general government expenditure on health | Out-of-pocket spending on PHC as a share of total PHC spending | External spending on PHC as a share of total PHC spending | |

| Low-income group | 40 (n=16) | 8 (n=16) | 24 (n=16) | 3 (n=14) | 12 (n=14) | 8 (n=14) | 59% (n=16) | 13% (n=14) | <1% (n=14) | 33% (n=14) | 44% (n=14) | 35% (n=14) |

| Lower-middle-income group | 104 (n=25) | 44 (n=25) | 52 (n=25) | 16 (n=24) | 23 (n=24) | 8 (n=24) | 52% (n=25) | 29% (n=24) | <1% (n=24) | 36% (n=24) | 49% (n=24) | 14% (n=24) |

| Upper-middle-income group | 416 (n=20) | 242 (n=20) | 169 (n=20) | 73 (n=19) | 65 (n=19) | 6 (n=19) | 42% (n=20) | 45% (n=19) | 1% (n=19) | 34% (n=19) | 39% (n=19) | 5% (n=19) |

| High-income group | 3310 (n=34) | 2355 (n=34) | 1312 (n=34) | 840 (n=33) | 318 (n=33) | 0 (n=33) | 42% (n=34) | 59% (n=33) | 2% (n=33) | 36% (n=33) | 28% (n=33) | <1% (n=33) |

| Total | 1306 (n=95) | 907 (n=95) | 523 (n=95) | 328 (n=90) | 139 (n=90) | 5 (n=90) | 48% (n=95) | 41% (n=90) | 1% (n=90) | 35% (n=90) | 39% (n=90) | 10% (n=90) |

GDP=gross domestic product. PHC=primary health care. OECD=Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. For total PHC spending, WHO provides data for 98 countries and OECD provides data on high income countries that overlap with WHO data but with an additional five countries which brings a total of combined data for 103 countries.. However, we excluded eight countries due to the inconsistency in how they reported health spending by functions (France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Portugal, UK, and USA). The total number of countries for which we present data is therefore 95 countries. For government spending on PHC, WHO provides data for 61 countries and OECD provides data for an additional 36 high income countries that brings a total of combined data for 97 countries. However, we excluded seven countries due to the inconsistency in how they reported health spending by functions (France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, UK, and USA). This gives a total number of 90 countries for this indicator. For five countries, the Global Health Expenditure Database reports total PHC spending data but no disaggregation by financial source (ie government, external, and private [Bosnia and Herzegovina, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Uruguay]). Only five high-income countries report external funding for PHC (Barbados, Mauritius, Seychelles, St Kitts and Nevis, and Trinidad and Tobago). For other high-income countries external spending is negligible or zero. Averages are unweighted means across countries. To calculate the average of ratios, we calculated the ratio for each country and took the average for each income group. The sum of government, external, and out-of-pocket spending will not be equal to the total spending due to the omission of other types of private spending, such as voluntary private insurance. The gap is bigger in high-income countries because private insurance is more common in high-income countries. Although out-of-pocket spending on PHC is available in the OECD database, WHO only reports domestic private spending on PHC. To estimate the out-of-pocket spending for PHC in low-income to middle-income countries, we took the ratio of total out-of-pocket spending on health to total domestic private spending on health and multiplied it by private spending for PHC for each country.

A descriptive analysis of PHC expenditure patterns is presented in the appendix (p 9). There is a strong correlation between income level and health expenditure on PHC, yet there is also substantial variation within any given economic level in how much governments spend on PHC. For example, spending in low income countries ranged from $8 to $46 and in lower middle-income countries, spending ranged from $11 to $120 per capita (appendix p 9). The share of PHC in current health expenditure (which includes expenditure from public, private, and external sources) decreases as countries' income levels increase—again, substantial variation exists at every income level. For example, the share in low income countries ranged from 29% to 86% (appendix p 10). Priority given to PHC within government health spending is similar on average across income groups, although there are variations in commitment at any given income level and this is more pronounced in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. However, the government share of total PHC spending was lowest in low-income countries, where both external sources and private spending (in LMICs, predominantly out-of-pocket spending) has a substantial role in financing PHC. Indeed only 13% of PHC financing in low-income countries is public.

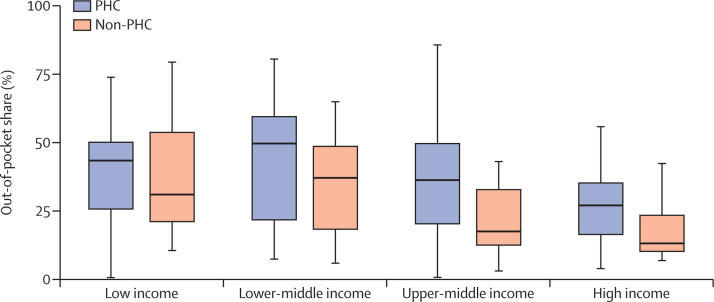

Financing for PHC in low-income and lower-middle-income countries is dominated by relatively unregulated private expenditure, most of which is out of pocket (figure 1 ). Only in high-income countries does the average share of out-of-pocket spending on PHC fall below 30% (although even in this group of countries, there is a long tail of countries with substantial out-of-pocket spending for PHC, suggesting that the issue is one of policy, not availability of resources). Figure 1 also compares the out-of-pocket share of PHC spending with the out-of-pocket share of non-PHC spending. At all country income levels, households are more exposed to out-of-pocket spending for PHC than for other health spending. This finding suggests that pooling arrangements provide less coverage for PHC and that households are more likely to be exposed to catastrophic financial consequences of paying for PHC—this underlines the importance of including PHC in benefit packages. The high level of out-of-pocket spending for PHC is particularly worrisome in LMICs, where the majority of people die from preventable causes that could be managed at the PHC level, and where poor people might be more likely to forego PHC than advanced specialist care. We contend that the lack of pooling for PHC runs counter to a progressive universalism approach to PHC, and exacerbates inequities. Finally, it is important to note that these figures do not account for people who are not able to access PHC at all; this is a general limitation of any equity analysis based on incurred expenditure.

Figure 1.

Out-of-pocket household spending as a share of total spending for PHC and non-PHC in 2018, by country income

Out-of-pocket share of PHC is calculated as out-of-pocket spending on PHC as a share of total PHC spending. Out of pocket share of non-PHC is calculated as out-of-pocket spending on non-PHC as a share of total non-PHC spending. The box represents IQR; the ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum value; the bold horizontal line represents the median. PHC=primary health care.

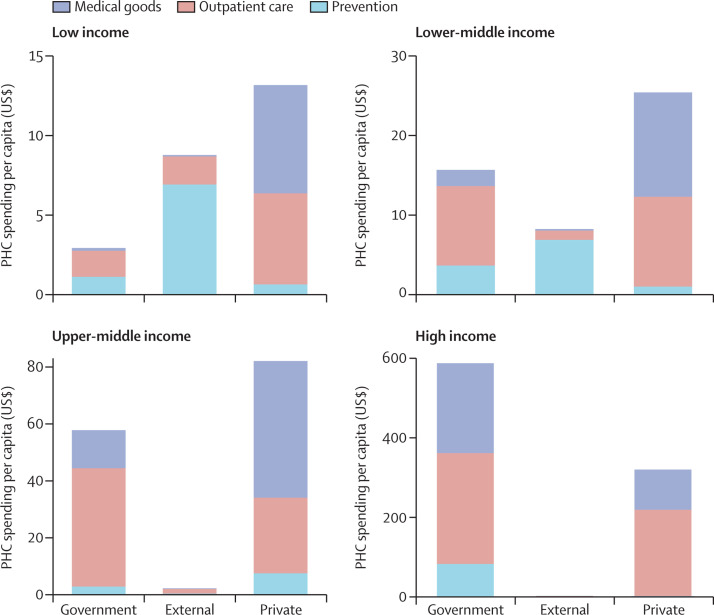

It is also notable that about half of private spending on PHC (most of which is out of pocket in LMICs) is for medical goods purchased outside health services (figure 2 ). Much of this is likely to be for medicines; for example, The Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines for Universal Health Coverage49 reported that more than 62% of pharmaceutical expenditure in LMICs was from private sources, which is likely to be mostly out-of-pocket spending considering the low levels of prepaid and pooled resources.

Figure 2.

Components of PHC spending by financial source in low-income to high-income countries in 2018

Figures exclude dental care and home care. Medical goods only include medicines and other medical goods purchased outside of outpatient facilities. Private spending includes individuals paying out of pocket and other domestic private sources, such as private insurance (voluntary and compulsory). External spending includes the use of grants, concessional loans, and aid in kind from outside the country. PHC=primary health care

In LMICs, the largest share of government expenditure is for outpatient care. Within this spending category, government health spending is highly skewed towards health-worker salaries. WHO's analysis of the Global Health Expenditure Database indicates that for 136 countries, 57% of public spending on health is allocated to wages.50 For PHC, in which few other inputs are used, salaries are likely to be an even higher share. This balance of spending likely represents a source of inefficiency if, after paying the wage bill, insufficient funds are left to purchase other inputs required for health workers to work effectively.

In low-income and lower-middle income countries, where external funds are a significant contributor to PHC expenditure, donor funds are predominantly spent on prevention. Figure 2 suggests significant fragmentation of PHC expenditure across financing sources.

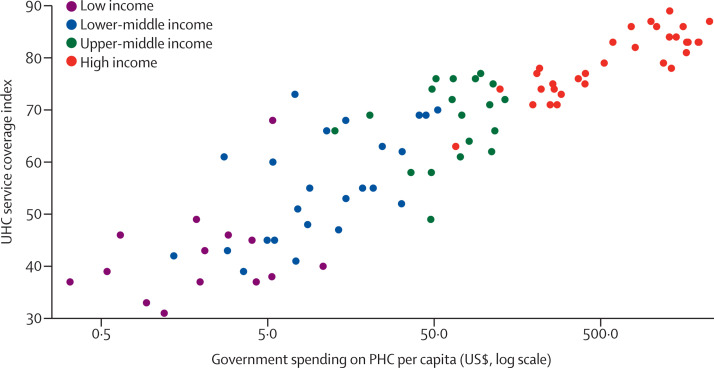

Does the level of spending matter? This Commission examined whether there is a relationship between overall government spending on PHC and coverage of key services (figure 3 ). We used the universal health coverage (UHC) service coverage index51 as a proxy for PHC service coverage—of the 14 variables indexed, 11 relate to core PHC services (in addition, the index includes hospital bed density, health-worker density, and capacity to implement the International Health Regulations). Two key findings emerge from the analysis. First, higher government spending on PHC is strongly associated with better service coverage. This relationship remains strong after adjustment for GDP per capita (result not shown), which figure 3 suggests could be a potential confounder. Second, for any given level of government spending, particularly below $50 per capita, there is substantial variation in performance on the service coverage index. For example, countries that spent between $50 and $55 have a range of UHC index from 42 to 68. Whether there is a causal relationship underlying the association between government spending on PHC and service coverage is hard to show. However, the data are consistent with the notion that countries should not only spend more but also spend better to achieve improved coverage of core PHC services.

Figure 3.

Government spending on PHC versus UHC index, 2018

PHC=primary health care. UHC=universal health coverage.

The role of donors in financing PHC

Low-income countries depend substantially on external sources to pay for PHC (appendix p 11). External funding typically focuses on prevention and treatment of single diseases, which can contribute to fragmentation in financing arrangements and PHC delivery—this is especially evident when externally funded programmes are not part of government planning and budgeting processes. Community health worker programmes, which often form the backbone of PHC delivery, are also highly dependent on donor funding: an estimated 60% of funding for community health worker programmes in sub-Saharan Africa comes from external sources, much of which is funding for vertical, disease-specific programmes.52 The fragmentation of PHC financing related to reliance on donor funding is due to requirements for tracking and reporting separately on donor funded activities. It might also be a source of inefficiency due to the so-called start-stop nature of donor funding (as compared with government budgeting).53

Limitations of our analyses

There are limitations to these analyses. First, use of the WHO's broad PHC expenditure definition has the effect of biasing the estimates of PHC spending upwards (because of the inclusion of outpatient services provided in hospitals). Any definition that uses a narrower scope would produce lower estimates of PHC expenditure. For example, in 2019, the OECD reported that spending on primary care within ambulatory settings represented just 12% of health expenditure; this increases to 17% when PHC services delivered in hospital settings are included, and to 34% by including retail pharmaceuticals.48

Second, data are only available for 95 out of 192 countries and for a single point in time. The spending estimates for some income groups are affected by the small number of countries in each group. Most importantly for our purposes, the absence of consistent and comparable data over time means that it is not possible to easily identify which countries are increasing or sustaining their commitments to PHC. Therefore, although these results are informative, throughout the report we also include more qualitative assessments of countries' progression towards adequate financing for PHC.

Even with our limited dataset, we argue that LMICs need to spend more on PHC to provide equitable and universal access PHC that is people centred. Further, the Commission contends that adopting a definition of PHC that is consistent with the vision of providing health care at the lowest possible level, and then supporting countries to collect and report data disaggregated in this way, are essential steps toward improving the quality of national data on PHC expenditure. Data, after all, are an essential part of the strategy for monitoring and actively protecting resources for PHC going forward, and for enabling countries to show their progress in increasing their commitment to PHC.52

Organisation and provider payment for PHC

Countries differ widely in terms of how PHC is structured and organised, including whether PHC includes community health workers and how they link to health facilities. Yet, although the availability of data on PHC expenditure in LMICs is improving, there is still little systematically collected cross-country data on the financial arrangements of LMIC health systems and provider payment structures. This contrasts with the data collected from OECD countries, for which the Health System Characteristics Survey provides comparable data on how countries finance, deliver, allocate resources to, and govern their health systems.42 To address this important data gap, in this Commission, we did our own cross-sectional survey in LMICs with the aim of collecting data on the key financing-related features of how PHC is organised, and on how PHC providers are paid. The questionnaire was sent in a personal email to health financing experts identified through the networks of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the World Bank, Results for Development, and WHO. The survey could be completed in two ways: either through self-completion or through a videoconference interview (for methods see appendix p 13). The survey was sent to 107 LMICs (one expert from each country), of which there were 75 responses: 22 from low-income countries, 22 from lower middle-income countries, and 31 from upper middle-income countries. Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 present key findings from this survey.

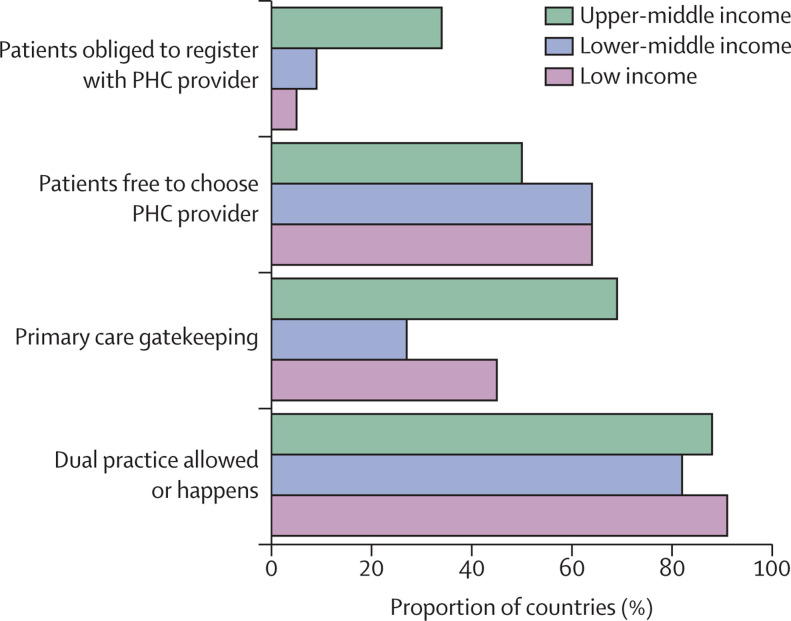

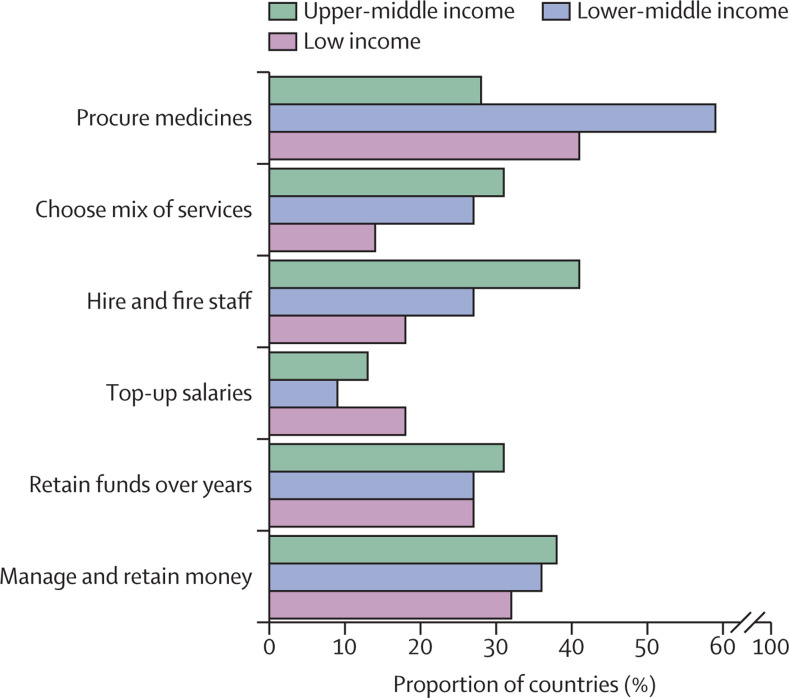

Figure 4.

Organisation and governance of public PHC providers

Data indicate the proportion of countries with each organisational and governance arrangement in place. Data are disaggregated by country income group. PHC=primary health care.

Figure 5.

Degree of autonomy for public PHC providers

Data indicate the proportion of countries in which public PHC providers have autonomy in how they function. Data are disaggregated by country income group. PHC=primary health care.

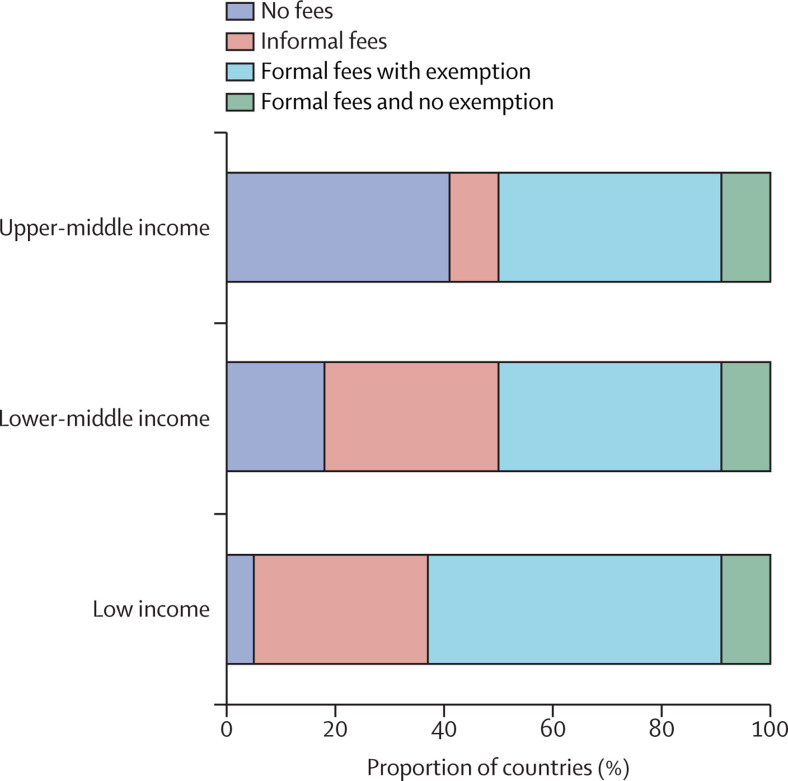

Figure 6.

Formal and informal user fees at public PHC providers

Data indicate the user fee policy in place in public PHC providers across surveyed countries (categories are mutually exclusive). Data are disaggregated by country income group. PHC=primary health care.

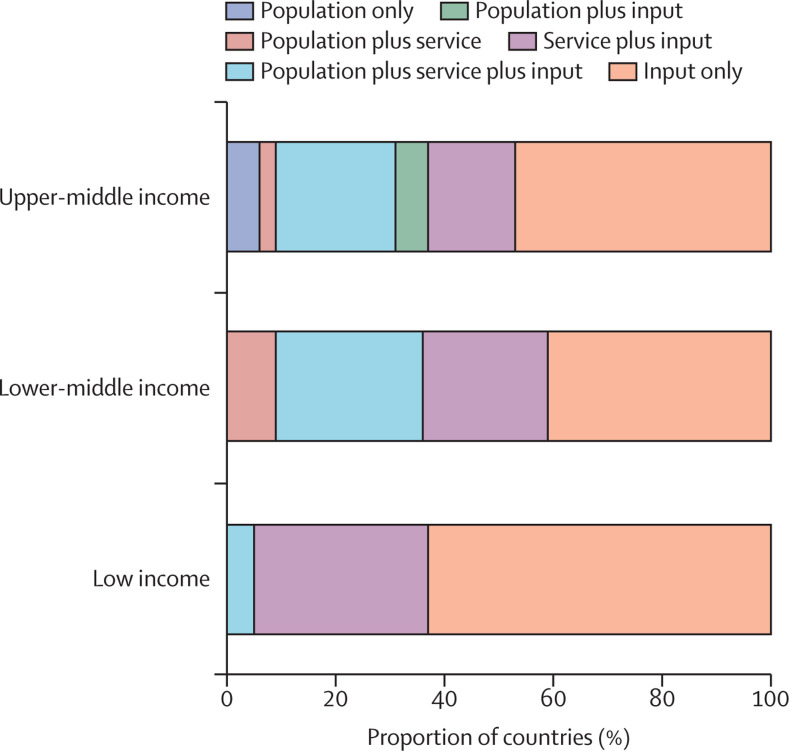

Figure 7.

Provider payment mechanisms for public PHC providers

Data indicate the type of payment system used in public PHC providers across surveyed countries (categories are mutually exclusive). Data are disaggregated by country income group. Population payment refers to capitation. Input-based payment refers to global budget, line item budget, and direct payment of salaries by government. Service-based payment refers to fee-for-service, case-based payment and pay-for-performance. PHC=primary health care.

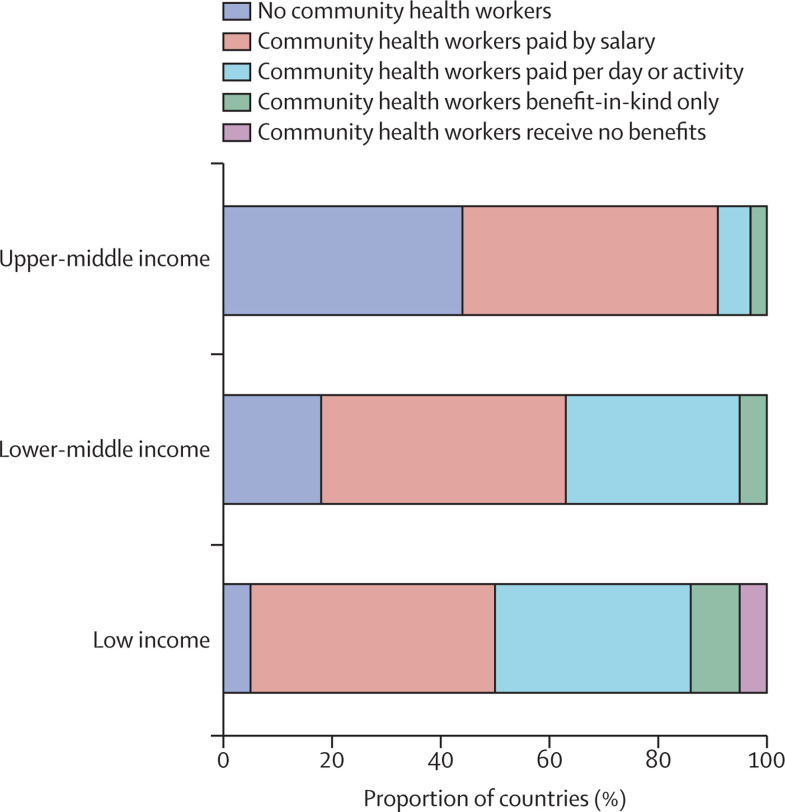

Figure 8.

Paying community health workers

Data indicate how community health workers delivering services on behalf of the government are remunerated in surveyed countries (categories are mutually exclusive). Data are disaggregated by country income group.

How PHC delivery is organised

Figure 4 presents results on indicators of how PHC services are organised that have implications for provider payment. The requirement for people to register with a public PHC provider, necessary for population-based forms of provider payment such as capitation, is uncommon in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, but more common in upper-middle-income countries. People are not restricted in their choice of public PHC providers in two-thirds of low-income and lower-middle-income countries. More restrictions on choice of provider (often in relation to the requirement to register with a provider) in upper-middle-income countries suggest that these countries seek to encourage greater consistency in use of PHC providers. Gatekeeping (in which individuals are required, or have strong financial incentives, to be referred by primary care providers to access higher-level services) is used in less than half of low-income countries. It is present in nearly three-quarters of upper-middle-income countries, although in practice these systems might frequently be circumvented. Dual practice (when a doctor works in both public and private sector practices) is common in all LMIC settings.

The extent of provider autonomy links closely with provider payment arrangements, because changing providers' incentives without enabling them to make decisions about how to use their resources constrains the potential for improvements in responsiveness and efficiency. Figure 5 shows that public sector PHC providers generally lack autonomy, with fewer than half of the countries included in the survey granting providers autonomy in any domain. More specifically, public PHC providers in fewer than 40% of LMICs have autonomy to manage and retain income, nor do they typically have the autonomy to top-up the salaries of their staff to reward performance. Provider autonomy to hire and fire staff, for example, tends to increase as country income level increases, with PHC providers in more than 40% of upper-middle-income countries able to make such decisions. There is a similar pattern across country income groups when it comes to autonomy to choose the mix of services to provide. Regarding procurement of medicines, however, autonomy is greatest in lower-middle-income countries—this might reflect chronic shortages of inputs.

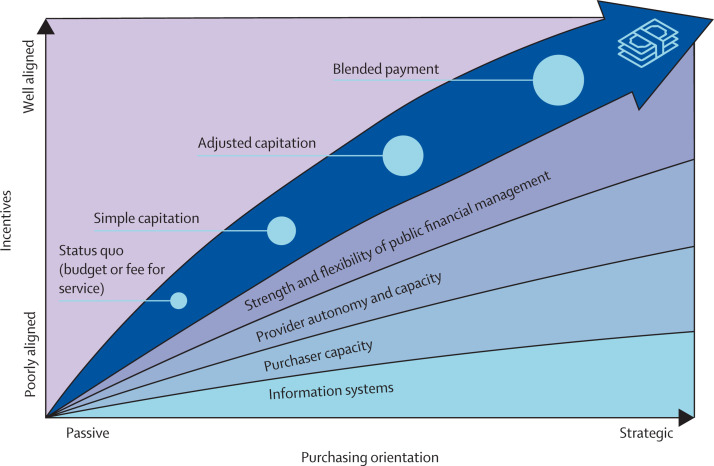

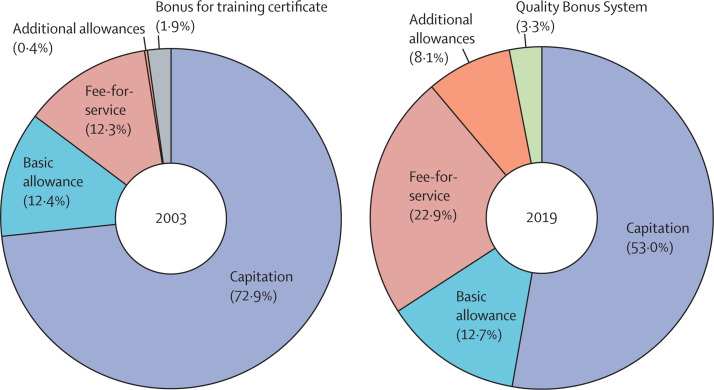

How PHC providers are paid by different funding sources