Abstract

Family members, also known as patients’ guardians (PG) are involved in caring for inpatients in acute care hospital settings. The practice is adopted from Family Centred Care (FCC) approach. This literature review aimed to provide an overview of key findings in literature on the practice of involving PGs in acute care hospital settings We used a systematic literature search to select original research articles or systematic reviews published in English between 2008 and 2019 that discussed PGs in acute care hospital settings. Studies that discussed PGs in long-term care hospital or in-home settings were excluded from this literature review. Literature was sought from CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. CASP and JBI checklist was used to appraise the full-text articles for inclusion in the literature review.

Twenty-six articles were included. Findings show that there is limited literature on this topic although healthcare institutions involve PGs in their routine inpatient care. Three themes emerged from the review; the FCC approach, roles of PGs in acute care hospitals, and implications of involving PGs in acute care hospitals.

PGs offer any care that is left undone by nurses in acute care hospitals to ensure that their patients’ needs are met. However, their involvement is not consistent with FCC principles. This leads to physical, psychosocial, and economic implications for PGs. We recommend that nurse practitioners should consistently implement FCC principles to enable PGs to offer meaningful care to their inpatients.

Keywords: patient's guardian, family centred care, acute care hospital, family caregiver

Introduction

This paper provides a review of literature, using a systematic search, regarding the involvement of family members commonly known as patient guardians (PG) in caring for inpatients in acute care hospital settings. A PG is a family member or friend who voluntarily offers to stay with an inpatient either throughout the period of hospitalization or part of the hospitalization period to provide physical, psychosocial, or spiritual care (Gwaza et al., 2017). The following are some of the synonyms used by different authors to describe a PG; informal caregiver (Ambrosi et al., 2017), hospital guardian (Hoffman et al., 2012), family member (Liput et al., 2016), patient's family ( Khosravan et al., 2014), the family caregiver(Dehghan Nayeri et al., 2015), in-hospital informal caregivers (Lavdaniti et al., 2011), for this literature review, all these shall be addressed as PG.

The presence of PGs and their involvement in caring for acutely ill adult inpatients is a common practice in African countries (Aziato & Adejumo, 2014; Phiri et al., 2017; Söderbäck & Christensson, 2008; Yakubu et al., 2018), the Middle East (Mobeireek et al., 2008), and Asia (Ito et al., 2010). In Europe, the presence of PGs in acute care hospitals is becoming more evident with the increase in the burden of chronic disease and increased life expectancy (Ambrosi et al., 2017; Caporaso et al., 2016). PGs are involved in caring for acutely ill adult inpatients due to cultural expectations (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Solum et al., 2012) and shortage of staff in the healthcare delivery system, (Ambrosi et al., 2017; Auslander, 2011; Phiri et al., 2017). Shortage of Health Care Workers (HCW) is one of the major direct causes of poor healthcare service delivery (Bradley et al., 2015; Shangwa, 2015).

With the recognition and adoption of the patient and family-centred care approach (Greene et al., 2012), involving PGs is recognized as one way of improving the quality of healthcare services. Partnership and collaboration between the nurses, patients, and PGs are regarded to be a standard component of care in hospitals yet it is not stipulated how this should be implemented (Kuo et al., 2012). There are no policies, regulations, and guidelines on the involvement of PGs in an acute care hospital setting (Dehghan Nayeri et al., 2015; Hoffman et al., 2012; Khosravan et al., 2014). The lack of clarity on the role of PGs in the hospital settings leads to inconsistent and ineffective communication between nurses and PGs. Alshahrani et al. (2018) reported that nurses withdraw from interacting with patients for fear of taking responsibility due to uncertainty on how they are supposed to be involved in the caring role. FCC is a model of care characterised by partnership and collaboration between HCW and the family in all aspects of child care (Festini, 2014). FCC was initiated to meet the psychosocial and developmental needs of children in recognition of the essential role the family plays in promoting the health and well-being of children (Majamanda et al., 2015). The principles of FCC are information sharing, respect, honouring differences, partnership, collaboration, and negotiation (Kuo et al., 2012). The benefits of FCC are; improved health outcomes for children, effective allocation of resources, increased patient, family, and HCW satisfaction, and promotion of parent-child bond (Coyne, 2015; Majamanda et al., 2015). Given the benefits of FCC, various healthcare institutions have adopted FCC in their models of patient care, not only in acute paediatric care settings but also in acute adult care settings (Alipoor et al., 2016; Auslander, 2011; Khosravan et al., 2014; Mackie et al., 2018; Solum et al., 2012).

Methods

We used a systematic review of the literature method that explores existing literature to provide an overview of key findings and debates that exist in theory and practice. The key findings may lead to new research objectives and thereby advance nursing research, theory, and practice (Hopia et al., 2016; Whittemore et al., 2014).

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted to understand the practice of involving PGs in caring for acutely ill adult inpatients. At the beginning of the literature search, a list of search terms was developed using synonyms used in literature to describe PGs that are involved in the care of inpatients. Table 1 shows the search terms that were used to search for the literature based on the concepts identified from the research question; what are the perspectives of nurses and family members in the practice of involving PGs in caring for adult inpatients in acute care hospital settings? We sought guidance from the librarian on how to create a logic grid for the literature search from various databases.

Table 1.

Search Terms.

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Patient guardian | Caring | Inpatients |

| Patient guardian* | Caring* | Adult inpatient* |

| Hospital guardian* | Participate* | Hospitalised patient* |

| Family caregiver* | Involve* | Surgical inpatient* |

| Informal caregiver* | Care experiences* | Inpatient* |

| Guardian* | Family centred care* | Admitted patient* |

| Companion* | Family engagement* | |

| Inpatient companion* | Family involvement* | |

| Lay caregiver* | Family participation* | |

| Unpaid care worker* | Patient and family centred care* | |

| Patient companion* | Patient focused care* | |

| Caregiver* | ||

| Family member* | ||

| Unpaid care giver* | ||

| Hospital caregiver* |

CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO are the databases that were used to search for literature that discussed PGs in acute care hospital settings. These databases were selected based on their relevance to the research topic. The terms in each concept were combined using Boolean OR and concepts 1, 2, and 3 were combined using Boolean AND. The same search terms were used across all the databases. De-duplication of articles that were found in more than one database was carried out using endnote.

Search alerts were set up after the initial search process to receive notifications about any new publications on the topic. Some references were identified manually by searching from related literature from the retrieved articles in Google Scholar.

Inclusion Criteria

This literature search includes articles retrieved during the specified search period that met the following criteria to achieve the objectives of the literature review:

Articles published in English between 2008 and 2019.

Primary studies and systematic reviews that used either qualitative or quantitative or mixed methods approach.

Studies that discuss PGs looking after adults or children in an acute or critical care hospital setting.

Exclusion Criteria

The following publications were excluded from this literature review:

Commentaries, editorials, papers, or posters.

Articles not published in English.

Studies that discuss PGs in a long-term or chronic care hospital setting.

Studies that discuss PGs for palliative care patients in an acute care hospital setting.

Studies that discuss PGs in-home care settings.

Critical Appraisal

Following the initial search, titles and abstracts were read for relevance to the literature search objectives. Full texts of all selected articles that addressed the search objectives were retrieved. These were read several times and appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative research checklist (CASP, 2013) for qualitative studies and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal for analytical cross-sectional studies (JBI, 2017) for quantitative studies. The JBI approach provides a pragmatic systematic review that aims at including a summary of the best available evidence. The use of a standardized tool allows the evaluation of evidence using structured questions and facilitates transparent and repeatable appraisals (Buccheri & Sharifi, 2017). The appraisal assessed the methodological quality of the studies by identifying the strengths and weaknesses in the design, conduct, and analysis of each study using the appraisal criteria (Aromataris & Munn, 2017). Articles that met satisfactory methodological quality during the appraisal were included.

Results

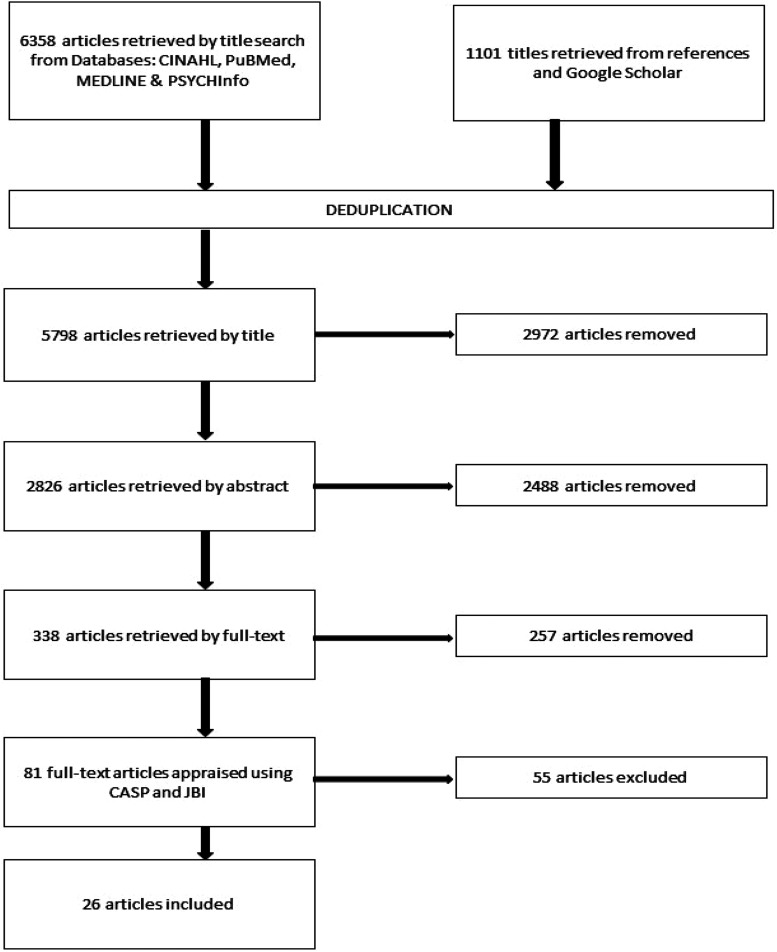

Figure 1 shows articles that were reviewed, included and excluded. After the appraisal, twenty-six articles met the inclusion criteria and were therefore included in this literature review. Out of these 26 studies, seven were qualitative, fifteen quantitative, and four mixed methods. Ten studies were from Europe, Four from Africa, Three from Asia and Australia, and one from America. These articles are summarised in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

Table 2.

Summary of Articles Included in the Literature Review.

| No. | Author/Year published/ Country | Title/Aim/Objectives | Methodology | Themes | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Hoffman et al., 2012 Malawi |

Utilization of family members to provide hospital care in Malawi: the role of hospital guardians To characterise guardian population and explore their role in the healthcare system of KCH |

Mixed methods Quantitative survey, 60 guardians, simple random and convenience sample In-depth interviews with guardians, HCWs and managers Descriptive analysis, emergent coding |

|

Poor FCC implementation as characterised by poor communication between HCWs and nurses. PG needs were not considered when involving them in the care. |

| 2 |

Khosravan et al., 2014 Iran |

Family participation in the nursing care of the hospitalized patients | Comparative descriptive 253 family members quota sampling 83 nurses, census sampling Questionnaire Descriptive stats and chi-square |

|

PGs voluntarily participate in the care of inpatients. Poor partnership and collaboration between PGs and HCWs leads to increased burden to the PGs |

| 3 |

Ewart et al., 2014, England |

PFCC on an acute adult cardiac ward To explore the effects of advancing PFCC within acute adult inpatient services |

Pre-post-intervention Survey, questionnaire Convenience sample 28PG, 24pts |

|

Collaboration and partnership between PG, patient and HCW in care provision has positive impact on patient and PG hospital experience |

| 4 |

Alipoor et al., 2016, Iran |

Care experiences and challenges of inpatients companions in Iran's healthcare context: A qualitative study To investigate the care experiences of inpatients companions at hospital |

Qualitative In-depth, unstructured interview 13PGs, purposive sample Thematic analysis |

|

PGs spend a substantial amount of time to voluntarily offer physical and psychological care to inpatients under strenuous conditions. HCW to provide support to meet their needs to help them cope with the caring role |

| 5 | Mackie et al., 2018, Australia |

Acute care nurses views on family participation and collaboration in fundamental care To understand how family participation and collaboration in care is enacted for hospitalised adult patients and their relatives |

Mixed methods, Exploratory sequential design Observer-as-participant observation Semi structured interviews 16 nurses observed 14 nurses purposeful sample interviewed Descriptive stats Qualitative thematic analysis |

|

Nurses behaviour and attitudes influence implementation of FCC in their practice |

| 6 |

Alshahrani et al., 2018, Saudi Arabia & Australia |

The involvement of relatives in the care of patients in medical settings in Australia and Saudi Arabia: an ethnographic study To understand the role of relatives in patient care and nurses’ roles in relation to involvement of relatives in medical settings in two different countries Impact of relatives on quality patient care in both medical settings |

Interpretivist, ethnographic Observation, interviews and review of public documents Spradley method of analysis of ethnographic enquiry Australia: 22pts, 22 relatives, 11 nurses (observed and interviewed) Saudi: 48 patients, 52 relatives & 18 nurses |

|

Need for policy to articulate roles and responsibilities for nurses and PGs in acute hospital settings |

| 7 |

Rostami et al., 2015 Iran |

The effect of education intervention on nurses attitudes toward the importance of FCC in paediatric wards in Iran. To determine nurses’ attitudes towards parents’ participation in the care of their hospitalised children in Iran |

RCT Experiment; pre-post-follow-up Questionnaire Random sample, 200 paediatric nurses Descriptive and analytical analysis |

|

Implementation of FCC problematic Educational intervention improves nurses attitudes towards FCC |

| 8 |

Segaric & Hall, 2015 Canada |

Progressively engaging: Constructing nurse, patient and family relationships in acute care settings To develop a substantive theory incorporating complex interactional processes and explanations for nurse, patient and family efforts to construct relationships during acute care hospitalisation |

Grounded theory Purposive sample of 17 nurses, 13 patients and 10 family members Interviews Constant comparison analysis |

|

Nurses to initiate relationship with family Workplace conditions and personal factors influence nurse-family relationships |

| 9 | Tehrani et al., 2012 Iran |

Effects of stress on mothers of hospitalised children in a hospital in Iran To investigate the impact of different stressors in mothers of hospitalised children |

Cross sectional study Simple random sample 225 mothers Descriptive and inferential analysis |

|

Need for professional and in depth training of for HCP and nurses on dealing with mothers of hospitalised children |

| 10 |

Lee et al., 2012 Malaysia |

Impact on parents during hospitalisation for acute diarrhoea in young children To determine the emotional impact on parents of young children who require hospitalisation for AD |

Prospective Convenience sample 85 parents/caregivers Descriptive stats |

|

Hospitalisation of children causes considerable distress and financial burden to parents and disruption of daily routines and missed workdays |

| 11 |

Sener & Karaca, 2017 Turkey |

Mutual expectations of mothers of hospitalised children and paediatric nurses who provided care: Qualitative study To identify the mutual expectations of mothers whose children were hospitalized in the paediatric department of a university hospital and nurses who provided care |

Descriptive phenomenological study In depth qualitative interview Purposive sample 5 nurses and 24 mothers |

|

Children's hospitalization is stressful for mothers. Open and therapeutic communication between parents and nurses contribute to improving quality of care provided to children and their families |

| 12 |

Söderbäck & Christensson, 2008 Mozambique |

Family involvement in the care of a hospitalized child: A questionnaire survey of Mozambican family caregivers To articulate Mozambican caregivers expressed needs, expectations and experiences of hospital care and hospital staff |

Cross sectional 100 PG, random sample Questionnaire |

|

Parents have desire to involve in the care of their hospitalized children. The PGs’ expectations are rooted in their poverty, households situation and healthcare system and hierarchical construct of their culture. Theses influence their communication and relationships hence they view hospital staff as superior. Need to empower the caregivers in the caring process in a cultural sensitive way |

| 13 | Tsironi & Koulierakis, 2018 Greece |

Factors associated with parents’ levels of stress in paediatric wards To assess the level of stress that parents of hospitalized children experienced and evaluate the association of parents stress and satisfaction and identify its predictors |

Cross sectional study Convenience sample 350 parents Qiuestionnaire |

|

During paediatric hospitalization, parental needs (Communication, interpersonal healthcare, continuous information and involvement in child care) should be considered to reduce parents’ stress and to improve their satisfaction in the quality of care provided |

| 14 |

Coyne et al., 2011 Ireland |

What does FCC mean to nurses and how do they think it could be enhanced in practice. To report nurses’ perceptions and practice of FCC |

Survey design 750 nurses, convenience sample Questionnaires, open-ended questions |

|

To provide good quality FCC nurses need adequate resources, appropriate education, support from managers and support from all members of the multidisciplinary team |

| 15 |

Phiri et al., 2017 Malawi |

Registered Nurses’ experiences pertaining to family involvement in the card of hospitalised children at a tertiary government hospital in Malawi To describe RNs experience of family involvement in the care of hospitalised children at a tertiary hospital |

Descriptive qualitative study Semi-structured interview 14 FT RNs purposive sample, data saturation Qualitative content analysis |

|

Family involvement in the care of hospitalised children desirable. Its implementation is inconsistent and problematic Need to regulate family involvement |

| 16 |

Wray, Lee et al., 2011 UK |

Parental anxiety and stress during children's hospitalisation: The stay close study To assess anxiety and stress in parents of children admitted to hospital, identify influencing factors and assess feasibility and acceptability of the methodology to parents and hospital staff |

Longitudinal study using mixed methods approach Pre-post hospitalization 28 convenience sample Descriptive stats and inferential analysis |

|

Parents experience substantial stress and anxiety when their child is admitted to hospital. Screening for those at high risk for anxiety and implementing interventions to reduce uncertainty and maladaptive coping strategies maybe beneficial |

| 17 |

Auslander, 2011 Israel |

Family caregivers of hospitalised adults in Israel: A point prevalence survey and exploration of tasks and motives. To estimate the extent of inpatient caregiving by family members of patients hospitalized in acute care hospitals in Israel, and its caregiver and patient correlates. |

Survey 513 convenience family caregivers Descriptive and inferential analysis |

|

Staff should identify caregivers, assess their motivations, and help determine appropriate tasks |

| 18 |

Caporaso et al., 2016 Italy |

Characteristics of caregivers attending adult and paediatric patients in Milan Hospital To investigate in depth characteristics and needs of caregivers involved in adult and paediatric patients who are receiving treatment for acute pathologies in hospital |

Questionnaire 364 caregivers |

|

Poor implementation of FCC when involving PG in caring for acute inpatients |

| 19 | Ambrosi et al., 2017 Italy |

Factors affecting in-hospital informal caregiving as decided by families: findings from a longitudinal study conducted in acute medical units To describe the proportion of patients admitted to acute medical units receiving care from informal caregivers as decided by the family To identify the factors affecting the numbers of care shifts performed by informal caregivers |

Longitudinal study 1464 patients convenience sample |

|

Families contribute substantially to the care of inpatients especially during the morning and afternoon shifts Patients are more likely to receive IC when they are risk of prolonged hospitalization and high occurrence of adverse clinical events such as falls, agitation/confusion, pressure sores and use of physical restraints Higher amount of missed nursing care is associated with higher amount of care shifts by IC |

| 20 |

Lavdaniti, Raftopoulos et al., 2011 Greece |

In-hospital informal caregivers’ needs as perceived by themselves and by the nursing staff in Northern Greece: A descriptive study To compare the perceptions of the nurses and in-hospital informal caregivers about in-hospital informal caregivers’ knowledge and informational needs, and factors that influence these perceptions |

Descriptive, non-experimental study 320 nurses and 370 IC in three general hospitals in Greece Questionnaires Descriptive stats |

|

In-hospital IC perceived that they have more educational and informational needs than nurses did. Nurses to identify these needs to be able to meet them |

| 21 |

Ito et al., 2010 Japan |

Perceptions of Japanese patients and their families about medical treatment decision making To investigate Japanese patients and their families’ perceptions regarding their actual and desired involvement in ethical decision making during a period of hospitalisation |

Survey Questionnaire, convenience sample 128 patients and 41 family members |

|

Family play crucial role in healthcare decision making even for competent patients Medical decision making to be done in collaboration with the HCW |

| 22 | Lin et al., 2016 Taiwan |

Reasons for family involvement in elective surgical decision making in Taiwan: a qualitative study To inquire into reasons for family involvement in adult patients’ surgical decision making processes from the view point of patients’ family |

Qualitative Purposive sample of 12 family members and 12 patients |

|

Family obliged to participate in decision making using their personal resources and connections. Family offers emotional support to patient by helping achieve a good relationship with medical team and protects patient's rights |

| 23 | Coyne, 2015 Ireland |

Families and health care professionals’ perspectives and expectations of FCC: hidden expectations and unclear roles To investigate how FCC was enacted from families and nurses’ perspectives |

Qualitative, grounded theory approach 18 children, parents and nurses |

|

Families willing to get involved in caring for their sick children in hospital Hidden expectations and unclear roles stressful for families Nurses to identify family needs and collaborate with them to provide optimal FCC |

| 24 |

Stuart & Melling, 2014 England |

Understanding nurses’ and parents’ perception of FCC To explore and compare the differences between parents and nurses perceptions of FCC for children's acute short stay admissions |

Mixed method Questionnaires |

|

Nurses to facilitate partnership with PGs to effectively implement FCC. |

| 25 |

Siffleet et al., 2010 Australia |

Costs of meals and parking for parents of hospitalised children in an Australian paediatric hospital To explore potential impact on family budget of costs of parking and meals incurred during a child's hospitalization |

Survey |

|

Hospital stay significantly depletes family disposable income Policy to consider offering three free meals to PGs Provide facilities with a broad choice of healthy, cheap and easily accessible meals on hospital site |

| 26 |

Ibilola Okunola et al., 2017 Nigeria |

Paediatric parents and nurses perception of FCNC in South West Nigeria To explore FCC behaviours perceived by paediatric nurses and parents as most and least important Effect of demographic characteristics on perception of FCNC |

Descriptive quantitative design Purposive sample 323 PG Simple random sample 176 nurses Questionnaire |

|

PGs and nurses value open communication and negotiation of patient care as the most important FCC behaviours. Years of nurses’ experience significantly influences perception of FCC behaviours by nurses. Length of hospital stay by PGs does not influence perception of FCC behaviours. |

The data was analysed by grouping similar findings into categories which were further refined into patterns and then into themes (Whittemore et al., 2014). The data identified from these articles informed this literature review.

Table 3.

Summary of PG Roles by Different Authors.

| No | Author/Year/Country | Roles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Hoffman et al. 2012 Malawi |

Cook and wash for patients |

| Give oral medication | ||

| Wound care and dressing | ||

| Nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding | ||

| Empty urine bag | ||

| 2 |

Ewart et al., 2014 England |

Feeding |

| Reassure patient | ||

| Provide information to HCW | ||

| Participate in doctors’ rounds | ||

| 3 |

Khosravan et al., 2014 Iran |

Take samples to the laboratory |

| Turn patient | ||

| Feeding patient | ||

| Give bedpan | ||

| Bath and dress patient | ||

| 4 | Alipoor et al., 2016 Iran |

Physical care |

| Psychosocial care | ||

| 5 | Mackie et al., 2018 Australia |

Give information to HCW |

| Advocate for quality care | ||

| Fundamental care | ||

| Promote patient safety | ||

| 6 |

Dehghan Nayeri et al., 2015 Iran |

Bathing patient |

| Feeding patient | ||

| Ambulation | ||

| Change beddings | ||

| Give medication | ||

| 7 |

Alshahrani et al., 2018 Saudi Arabia & Australia |

Activities of daily living |

| Ambulation | ||

| Positioning | ||

| Bathing | ||

| Monitoring and reporting patient's progress to HCW | ||

| Wound dressing | ||

| Oxygen administration | ||

| Stopping IV fluids | ||

| Read Bible and pray with patient |

The following three themes were identified from the literature: family-centred care (FCC) approach, roles of PGs in an acute care hospital setting, and implications of involving PGs in an acute care hospital setting.

Family Centred Care Approach

Thirteen studies are included in this theme; two were mixed-methods studies, four were qualitative and the rest were quantitative studies. This theme describes the evidence on the implementation of the FCC approach in different settings.

The continued physical presence of family members in acute care hospital settings and their involvement in caring for inpatients is a practice that has been adopted from the Family-centred care (FCC) approach. Although family members are willing to be involved in caring for inpatients (Ewart et al., 2014), the implementation of FCC has been problematic and inconsistent worldwide (Coyne, 2015). Nurses know FCC principles but they involve PGs to share the workload (Coyne et al., 2011; Phiri et al., 2017). Some of the identified barriers to FCC are; nurses attitude (Rostami et al., 2015), poor communication between nurses and PGs (Hoffman et al., 2012), lack of negotiation, poor staffing levels, organisational policy (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Phiri et al., 2017; Segaric & Hall, 2015), the power imbalance between HCWs and PGs (Söderbäck & Christensson, 2008) and over-dependence of nurses on PGs (Coyne, 2015).

Phiri et al., (2017) reported that Registered Nurses in Malawi listed information sharing and partnership as what it means to involve PGs. However, they involved the family to share the workload and to give themselves time to do other administrative duties due to the shortage of nurses and not to partner with the family. Involving PGs in the care of hospitalized children was perceived as time-consuming and demanding because some PGs were slow to understand some information and learn new skills. The nurse-PG relationship in this study was characterised by a lack of trust and a lack of negotiation of roles due to poor communication (Phiri et al., 2017).

Similarly, Segaric & Hall (2015) and Coyne (2015) revealed that nurses were able to define FCC and its principles. Parents, on the other hand, were not able to clearly define FCC. Parents participated in offering care to their hospitalised children because they perceived performing Activities of Living (AL) as their responsibility. Parents perceived that their role was to assist busy nurses to ensure that their children received good care. Children reported that they felt safe to have their parents around because they provided them with comfort in the unfamiliar and frightening hospital environment. Nurses on the other hand acknowledged that they were too busy to offer basic care; hence their role was to do technical procedures and administration work. The nurse-PG relationship was characterised by a lack of partnership, communication, and negotiation of roles (Coyne, 2015).

Furthermore, findings from Alshahrani et al. (2018) revealed that the practice of involving PGs in acute medical wards was characterised by a lack of role clarity between nurses and PGs due to lack of communication and negotiation. Lack of policy that would articulate the roles and responsibilities of patients, PGs, and nurses on the involvement of PGs in the care of inpatients led to nurses avoiding interaction with PGs (Alshahrani et al., 2018).

FCC advocates for a mutual partnership between the family and nurses in the care of hospitalised children. It is characterised by mutual respect, timely and unbiased sharing of information, and collaboration between the PGs and nurses. FCC requires effective communication between the PG and the healthcare team for both parties to negotiate each one's role and responsibility in the partnership (Coyne et al., 2011). Effective communication promotes psychological comfort for the patient and the PG (Gondwe et al., 2017).

Contrary to the above findings, Stuart & Melling, (2014) found that nurses were able to partner and collaborate with PGs in a paediatric short-stay ward in England. They effectively negotiated with parents to monitor and document fluid intake for their sick children thereby sharing responsibility in monitoring fluid balance. This demonstrates that it is possible to effectively implement FCC principles when involving PGs in acute care hospital settings. Information sharing and negotiation of caring roles are important in promoting effective FCC (Ibilola Okunola et al., 2017).

The Role of PG in Adult Acute Care Hospital Settings

This theme discusses the activities performed by PGs in acute care hospital settings. Twelve studies; (five qualitative, five quantitative, and two mixed methods studies), are included in this theme. Family members care for their sick relatives throughout their life-cycle. This involves care offered even when they are hospitalised. However, this practice has received ambivalence from both nurses and PGs. Although healthcare institutions have adopted the FCC model of patient care, the role of PGs in an acute care hospital setting is not stipulated ( Khosravan et al., 2014; Solum et al., 2012). HCWs recognise their involvement as one way of reducing the burden of shortage of staff in the hospitals (Ambrosi et al., 2017; Phiri et al., 2017). PGs offer any care that is missed by the nurses to ensure that their patients’ needs are met throughout the period of hospitalization. Table 3 summarizes PG roles as analyzed by different authors. PGs offer physical, psychosocial, and spiritual care to inpatients, (Alipoor et al., 2016; Khosravan et al., 2014; Mackie et al., 2018). Alshahrani et al., (2018) described the role of PGs in an acute care hospital setting as complex and undefined because they do anything that they feel needs to be done for their patients. Their lack of knowledge on their rights and responsibilities while in the hospital makes nurses get accustomed to leaving any care for them (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Coyne, 2015). Alshahrani et al., (2018) listed wound dressing, oxygen administration, stopping intravenous fluids, feeding patients, and helping them with toileting and personal hygiene as some of the activities PGs performed for inpatients. Stuart & Melling (2014) listed bathing and dressing the child, changing nappies, feeding, playing with the child, and bed-making as activities that were performed to meet the physical and psychological needs of the child. The following activities were listed as nursing activities; inserting NGT, giving oral and injectable medications, testing blood sugar, checking body temperature, distracting the child during a procedure, and monitoring fluid balance.

Similarly, Hoffman et al., (2012) found that PGs perform a wide range of activities. They reported that PGs cook, wash for patients, assist with giving medication, do wound care and dressing, NGT feeding, emptying urine bags, advocate for their patients, monitor and report patient progress to HCWs. In England, (Ewart et al., 2014), reported that PGs offered basic care, helped to feed the patients, reassured patients, and provided them with information to understand what was happening. PGs also participated in doctors’ rounds. While ( Khosravan et al., 2014), in a study conducted in Iran, found that PGs take samples to the laboratory, empty urine bags, turn and feed patients, give patients bedpan and bath and dress patients. In another study conducted in Iran, (Alipoor et al., 2016), stated that PGs offer physical and psychological care to inpatients. They, however, did not elaborate on the actual activities that PGs did that constituted physical and psychological care for their patients while in hospital. An Australian study, (Mackie et al., 2018), stated that PGs are key informants for HCWs because they provide them with important information regarding patient's conditions and preferences while in hospital, they advocate for quality care, provide fundamental care and promote patient safety. They also did not specify the actual activities that constituted fundamental care in their context. (Dehghan Nayeri et al., 2015) found that family members performed fewer priority aspects of care that were usually omitted by nurses due to increased workload. These among others included; showering and feeding the patient, ambulation, changing beddings, and providing medication and other medical supplies.

Due to the shortage of nurses, most of the patient care activities remain undone due to time pressure (Ball et al., 2014). The above literature demonstrates that involving PGs in an acute care hospital setting is one way of ensuring that most of the nursing care activities are done. Acutely ill inpatients are usually not able to take care of themselves, they need constant help, monitoring, and support to meet the activities of living and other needs (Ambrosi et al., 2017). Individual and nursing care factors influence the amount of informal care acutely ill patients receive during hospitalisation (Ambrosi et al., 2017). PGs are not aware of the nursing care plan for the patients they were assisting (Caporaso et al., 2016). Families participate in caring for acutely ill inpatients when they perceive that their patients are not adequately looked after by nurses (Ambrosi et al., 2017).

The above evidence has also shown that nurses, in some settings, leave technical nursing care activities for PGs, like wound care, NGT feeding, oxygen administration, stopping intravenous fluids, and monitoring medication (Hoffman et al., 2012; Alshahrani et al., 2018). This might not be safe for both the patient and the guardian because they may not know the technical aspect of performing such activities accurately. Evidence also demonstrates that the nurse-PG relationship is characterised by poor communication (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Hoffman et al., 2012; Khosravan et al., 2014). PGs were therefore allowed to perform those tasks without being trained or supervised or supported. PGs are more willing to perform familiar activities than those that cause discomfort to their patients because it gives them a feeling of being in control during the stressful hospitalisation period (Stuart & Melling, 2014). The lack of policies to guide the standard practice of involving family members in the care of acutely ill inpatients makes it difficult for nurses to facilitate the participation of PGs because they do not want to take responsibility if something goes wrong in the end (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Phiri et al., 2017). No literature evaluated the impact of involving PG in performing technical nursing activities like wound care and dressing and NGT feeding for acutely ill inpatients. The lack of support and supervision from nurses makes PGs a safety hazard to their patients and themselves because they are not trained to offer such care to inpatients (Solum et al., 2012).

PGs provide psychosocial care to their loved ones during the period of hospitalization. The hospital environment is frightening to children, therefore they preferred their parents to stay with them throughout the hospitalisation period to provide them with comfort (Coyne, 2015). This reduces stress. The presence of PGs throughout the patients’ hospitalization period make them feel secure (Alshahrani et al., 2018). Patients want their PGs to stay with them throughout the entire period of hospitalization to keep them company and help them meet some of their needs when nurses are busy. They also helped patients understand some information from the HCWs about their illness and treatment plan. Patients’ wishes, interests, and preferences were safeguarded by the PGs. They advocated for quality care for their patients during hospitalization by asking questions to seek clarification and complaining when they were not happy with some aspects of care (Alshahrani et al., 2018).

PGs play an essential role in ensuring that patients’ spiritual needs are met while in hospital. Alshahrani et al., (2018) revealed that PGs were instrumental in helping patients meet their spiritual needs. PGs read the Bible and prayed with patients in the hospital because they considered their spiritual needs important even when they were unwell in the hospital (Alshahrani et al., 2018).

Implications of the Caring Role to the PGs

Thirteen studies are included in this theme. These comprise of one mixed methods study, six quantitative studies and the rest are qualitative studies. Hospitalisation disrupts PGs’ daily routines (Lee et al., 2012) because they leave their routine roles and assume the new caring role without preparation. This leads to physical, psychosocial, and economic implications for PGs.

Physical Implications of the Caring Role

Lee et al., (2012) reported that some parents experience insomnia and physical exhaustion due to their children's physical and emotional condition. They reported that children who had more frequent diarrhoea and vomiting required more attention and care from their parents. This kept them busy for prolonged periods until the time the symptoms reduced in frequency (Lee et al., 2012). The noise in the wards from other patients and their PGs in the room and continuous activity from a multidisciplinary team of HCWs disrupted their rest and sleep patterns. Alipoor et al. (2016) found that PGs constantly suffer from caregiver burnout. This is manifested as persistent tension and fatigue because they are unable to cope with the complex care responsibilities. They further stated that PGs usually sacrifice their needs to make sure their patients have well looked after. They stand for prolonged periods, have no food and proper place to rest and sleep (Alipoor et al., 2016). Alshahrani et al., (2018) found that PGs had back, neck, and shoulder pain in the short term due to a lack of training on how they should position themselves when lifting or turning their patients.

Psychosocial Implications of the Caring Role

Hospitalisation is stressful to the patient and the rest of the family (Ambrosi et al., 2017; Tsironi & Koulierakis, 2018). Various factors contribute to the emotional distress of PGs in acute care hospital settings. The behavioural change of patients when they are just admitted leads to emotional distress for their family members (Lee et al., 2012; Wray et al., 2011). PGs feel empathetic, uncomfortable, worried, and anxious when they imagined their patients’ pain post-operatively (Aziato & Adejumo, 2014).

The separation of PGs from the rest of the family disrupts the normal lives of the entire family (Lee et al., 2012) and this may lead to stress and anxiety for the PGs. PGs reported feeling sad, afraid, and anxious not only for the sick child but for other children at home when they were advised that their child needs to be admitted (Şener & Karaca, 2017). They, however, reported that they felt safe to be in the hospital with the sick child because they knew they would not be able to look after the sick child at home. The ambiguity of the role of PGs in acute care hospital settings leads to poor interaction between nurses and PGs. Alshahrani et al. (2018) reported that nurses avoided interacting with PGs because they were viewed as a burden to them, hence they felt “invisible” in the hospital. The poor relationship between PGs and nurses led to frustration by the PGs.

Economic Implications of the Caring Role

The economic cost of informal care is difficult to quantify (Quattrin et al., 2009) but PGs produce a substantial amount of output in the healthcare delivery system (Ambrosi et al., 2017) because they perform duties that should have been done by a paid worker. The caring role has a considerable financial burden on the PG (Lee et al., 2012; Siffleet et al., 2010). Participation of the PGs in caring for acutely ill inpatients means that they temporarily abandon their routine roles to donate care in the hospital.

Lee et al., (2012) found that 81 out of 85 parents missed workdays to look after their sick children. 34% of parents in this study reported that they incurred a loss of income. The cost included medical expenses at an average of $225.09 and loss of income due to inability to go to work of $20.83 and a travelling cost of $6.96. The median total cost incurred due to such hospitalisation was $252.86 in an average of four admission days. This translated to approximately 16% of the combined family disposable income per month. Siffleet et al., (2010) revealed that an average of 30% of a family's disposable weekly income was spent on meals and parking. Parents of hospitalised children who offered to stay with their children throughout the period of hospitalisation spent at least $29.9 on meals and $13 on parking per day. The findings of this study showed that hospitals do not consider providing PGs with meals and parking space while they advocate for the effective implementation of FCC. The study reported that rooming-in parents were provided with breakfast only while breastfeeding mothers were provided with all meals. Parents were forced to leave their children and walk a long distance to buy meals which were quite expensive for them (Siffleet et al., 2010). This would increase the economic burden of the caring role for the PGs. Hoffman et al., (2012) reported that PGs looked for piece work around the hospital to earn some income to meet their needs and those of their patients while in the hospital because they depleted most of their disposable income during the period of hospitalization. No study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of involving PGs in acute care hospital settings despite the positive patient outcomes and its acceptability by both family members and nurses.

Implications for Practice

Most of the articles that met the inclusion criteria for this literature review were done in acute care paediatric settings. This is because little has been documented on involving PGs in adult acute care hospital settings although the practice has been adopted in adult acute care settings in various countries for a long time now ( Khosravan et al., 2014; Söderbäck & Christensson, 2008; Solum et al., 2012; Yakubu et al., 2018). More studies should be done in adult acute care hospital settings on this topic to ascertain the facts on PG involvement in adult settings.

Secondly, most of the studies presented in this literature review were conducted in the Middle East and Europe. The cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic characteristics of these countries are different from those in other continents. Therefore, we cannot generalise these findings in other contexts. The burden of shortage of nurses in Sub-Saharan Africa is not the same as in other contexts like Europe and the Middle East. We, therefore, recommend more studies on this topic in other contexts.

Thirdly, involving PGs in acute care has been adopted from the FCC approach. However, its implementation is inconsistent with FCC principles. Therefore, we recommend more research that would identify strategies to promote consistent implementation of FCC in acute care hospitals especially in settings with a shortage of nurses because FCC is well implemented in settings with adequate staffing (Ewart et al., 2014).

Lastly, no literature included in this review presented theoretical frameworks that guided their study.

Conclusion

The majority of family members are willingly involved in caring for their sick relatives in the hospital. FCC approach has been adopted as the model of patient care not only in paediatric settings but also in adult inpatient settings. However, its implementation is inconsistent and problematic worldwide due to nurses’ and PGs’ ambivalence on the practice. The involvement of PGs in an acute care hospital setting is characterised by poor communication, lack of negotiation on their roles, and lack of partnership and collaboration between PGs and nurses. PGs have proven to be resourceful in ensuring that most of the care missed by nurses is done. PGs usually offer basic care to inpatients in most settings. However, in other contexts, PGs perform some technical care activities without being trained, supervised, or supported. This may lead to physical and psychosocial implications for the PGs. The caring role has a substantial economic impact on the PGs and their families. They spend more money on transport, food, and other costs to meet their needs while in hospital. More studies should be done on the practice of involving family members in acute care hospital settings to develop a model of care that involves family members in acute care hospital settings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Prof. Dianne Watkins and Dr Judith Carrier of Cardiff University for their moral and technical support during the initial development of this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This literature review was part of a PhD research work which was funded by Norhed PhD Student Research Grant NORHED MWI-13 / 0032-QZA-0484.

Ethical Statement: The authors searched for all data included in this literature review ethically without infringing any rights.

ORCID iD: Elizabeth Gwaza https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4809-4259

References

- Alipoor T., Abedi H. A., Masoudi R. (2016). Care experiences and challenges of inpatients’ companions in Iran’s health care context: A qualitative study. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences, 5(7, S,), 286-U674. http://eprints.skums.ac.ir/id/eprint/1267 [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani S., Magarey J., Kitson A. (2018). Relatives’ involvement in the care of patients in acute medical wards in two different countries—an ethnographic study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(11–12), 2333–2345. 10.1111/jocn.14337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosi E., Biavati C., Guarnier A., Barelli P., Zambiasi P., Allegrini E., Bazoli L., Casson P., Marin M., Padovan M., Picogna M., Taddia P., Salmaso D., Chiari P., Frison T., Marognolli O., Benaglio C., Canzan F., Saiani L., Palese A. (2017). Factors affecting in-hospital informal caregiving as decided by families: findings from a longitudinal study conducted in acute medical units. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(1), 85–95. 10.1111/scs.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E., Munn Z. (2017). Joanna Briggs institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017(1). http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html [Google Scholar]

- Auslander G. K. (2011). Family caregivers of hospitalized adults in Israel: A point-prevalence survey and exploration of tasks and motives. Research in Nursing & Health, 34(3), 204–217. 10.1002/nur.20430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziato L., Adejumo O. (2014). Psychosocial factors influencing Ghanaian family caregivers in the post-operative care of their hospitalised patients. Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 16(2), 112–124. 10.10520/EJC169755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J. E., Murrells T., Rafferty A. M., Morrow E., Griffiths P. (2013). ‘Care left undone’ during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. Quality and Safety in Health Care, Bmjqs, 23(2), 116–125. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley S., Kamwendo F., Chipeta E., Chimwaza W., de Pinho H., McAuliffe E. (2015). Too few staff, too many patients: A qualitative study of the impact on obstetric care providers and on quality of care in Malawi. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(65). 10.1186/s12884-015-0492-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccheri R. K., Sharifi C. (2017). Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for evidence-based practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(6), 463–472. 10.1111/wvn.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso N., Lanzoni M., Castaldi S. (2016). The characteristics of caregivers attending adult and paediatrics patients in a Milan hospital . 10.7416/ai.2016.2092 [DOI] [PubMed]

- CASP (2013). Critical Appraisal Skills Program Qualitative Reseach checklist. Critical Appraisal Skills Program. www.casp-uk.net.

- Coyne I. (2015). Families and health-care professionals’ perspectives and expectations of family-centred care: hidden expectations and unclear roles. Health Expectations, 18(5), 796–808. 10.1111/hex.12104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., O’Neill C., Murphy M., Costello T., O’Shea R. (2011). What does family-centred care mean to nurses and how do they think it could be enhanced in practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(12), 2561–2573. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan Nayeri N., Gholizadeh L., Mohammadi E., Yazdi K. (2015). Family involvement in the care of hospitalized elderly patients. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 34(6), 779–796. 10.1177/0733464813483211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart L., Moore J., Gibbs C., Crozier K. (2014). Patient- and family-centred care on an acute adult cardiac ward. British Journal of Nursing, 23(4), 213–218. 10.12968/bjon.2014.23.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festini F. (2014). Family-centered care. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 40(1), A33. 10.1186/1824-7288-40-S1-A33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gondwe M. J., Gombachika B., Majamanda M. D. (2017). Experiences of caregivers of infants who have been on bubble continuous positive airway pressure at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Malawi: A descriptive qualitative study. Malawi Medical Journal, 29(1), 5–10. 10.4314/mmj.v29i1.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene S. M., Tuzzio L., Cherkin D. (2012). A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. The Permanente Journal, 16(3), 49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3442762/pdf/i1552-5775-16-3-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaza E., Maluwa V., Kapito E., Sakala B., Mwale R., Haruzivishe C., Chirwa E. (2017). Patient guardian: concept analysis. Intermational Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 6(8), 333–337. 10.24940/ijird/2017/v6/i8/AUG17042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M., Mofolo I., Salima C., Hoffman I., Zadrozny S., Martinson F., Horst C. V. D. (2012). Utilization of family members to provide hospital care in Malawi: the role of hospital guardians. Malawi Medical Journal, 24(4), 74–78. 10.4314/mmj.v24i4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopia H., Latvala E., Liimatainen L. (2016). Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(4), 662–669. 10.1111/scs.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibilola Okunola R. N., Olaogun A. A., Adereti S. C., Abisola Bankole R. N., Elizabeth Oyibocha R. N., Olayinka Ajao R. N. (2017). Peadiatric parents and nurses perception of family-centered nursing care in southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 10(1), 67. http://www.internationaljournalofcaringsciences.org/docs/8_ibilola_original_10_1 [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Tanida N., Turale S. (2010). Perceptions of Japanese patients and their family about medical treatment decisions. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(3), 314–321. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JBI (2017). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers Manual. Joanna Briggs Institute. http://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org.

- Khosravan S., Mazlom B., Abdollahzade N., Jamali Z., Mansoorian M. R. (2014). Family participation in the nursing care of the hospitalized patients. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16(1), e12686. 10.5812/ircmj.12868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D. Z., Houtrow A. J., Arango P., Kuhlthau K. A., Simmons J. M., Neff J. M. (2012). Family-centered care: current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(2), 297–305. 10.1007/s10995-011-0751-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavdaniti M., Raftopoulos V., Sgantzos M., Psychogiou M., Areti T., Georgiadou C., Serpanou I., Sapountzi-Krepia D. (2011). In-hospital informal caregivers’ needs as perceived by themselves and by the nursing staff in northern Greece: A descriptive study. BMC Nursing, 10(1), 1–8. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/1472-6955-10-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-S., Chai P.-F., Ismail Z. (2012). Impact on parents during hospitalisation for acute diarrhoea in young children. Singapore Medical Journal, 53(11), 755. http://www.smj.org.sg/sites/default/files/5311/5311a8.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. L., Huang C. T., Chen C. H. (2016). Reasons for family involvement in elective surgical decision-making in Taiwan a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(13-14), 1969–1977. 10.1111/jocn.13600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liput S. A., Kane-Gill S. L., Seybert A. L., Smithburger P. L. (2016). A review of the perceptions of healthcare providers and family members toward family involvement in active adult patient care in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 44(6), 1191–1197. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie B. R., Marshall A., Mitchell M. (2018). Acute care nurses’ views on family participation and collaboration in fundamental care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(11–12), 2346–2359. 10.1111/jocn.14185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majamanda M. D., Munkhondya T. E. M., Simbota M., Chikalipo M. (2015). Family centered care versus child centered care: the Malawi context. Health, 7(06), 741. 10.4236/health.2015.76088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mobeireek A. F., Al-Kassimi F., Al-Zahrani K., Al-Shimemeri A., Al-Damegh S., Al-Amoudi O., Al-Eithan S., Al-Ghamdi B., Gamal-Eldin M. (2008). Information disclosure and decision-making: the Middle East versus the far east and the west. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34(4), 225–229. 10.1136/jme.2006.019638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phiri P. G. M. C., Kafulafula U., Chorwe-Sungani G. (2017). Registered Nurses’ experiences pertaining to family involvement in the care of hospitalised children at a tertiary government hospital in Malawi. Africa Journal of Nursing & Midwifery, 19(1), 131–143. 10.25159/2520-5293/910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrin R., Artico C., Farneti F., Panariti M., Palese A., Brusaferro S. (2009). Study on the impact of caregivers in an Italian high specialization hospital: presence, costs and nurse’s perception. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 23(2), 328–333. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostami F., Hassan S. T. S., Yaghmai F., Ismaeil S. B., BinSuandi T. (2015). The effect of educational intervention on nurses’ attitudes toward the importance of family-centered care in pediatric wards in Iran. Electronic Physician, 7(5), 1261. 10.14661/1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segaric C. A., Hall W. A. (2015). Progressively engaging: constructing nurse, patient, and family relationships in acute care settings. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(1), 35–56. 10.1177/1074840714564787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şener D. K., Karaca A. (2017). Mutual expectations of mothers of hospitalized children and pediatric nurses who provided care: qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing: Nursing Care of Children and Families, 34(02.004), e22–e28. 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shangwa R. (2015). An investigation into the causes of understaffing of registered nurses in mission hospitals: A case for Mashoko Mission Hospital. http://ir.msu.ac.zw:8080/jspui/handle/11408/2491.

- Siffleet J., Munns A., Shields L. (2010). Costs of meals and parking for parents of hospitalised children in an Australian paediatric hospital. Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing, 13(3), 7–11. 10.3316/informit.543096194876776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Söderbäck M., Christensson K. (2008). Family involvement in the care of a hospitalised child: A questionnaire survey of mozambican family caregivers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(12), 1778–1788. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solum E. M., Maluwa V. M., Severinsson E. (2012). Ethical problems in practice as experienced by Malawian student nurses. Nursing Ethics, 19(1), 128–138. 10.1177/0969733011412106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart M., Melling S. (2014). Understanding nurses’ and parents’ perceptions of family-centred care. Nursing Children and Young People (2014+); London, 26(7), 10.7748/ncyp.26.7.16.e479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani H. T., Haghighi M., Bazmamoun H. (2012). Effects of stress on mothers of hospitalized children in a hospital in iran. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology, 6(4), 39–45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3943023/pdf/ijcn-6-039.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tsironi S., Koulierakis G. (2018). Factors associated with parents’ levels of stress in pediatric wards. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(2), 175–185. 10.1177/1367493517749327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R., Chao A., Jang M., Minges K. E., Park C. (2014). Methods for knowledge synthesis: an overview. Heart & Lung, 43(5), 453–461. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J., Lee K., Dearmun N., Franck L. (2011). Parental anxiety and stress during children’s hospitalisation: the StayClose study. Journal of Child Health Care, 15(3), 163–174. 10.1177/1367493511408632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu K., Malan Z., Colon-Gonzalez M. C., Mash B. (2018). Perceptions about family-centred care among adult patients with chronic diseases at a general outpatient clinic in Nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), 1–11. 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]