Key Points

Question

Did the frequency of adverse pregnancy outcomes change from 2014 to 2020 among individuals with gestational diabetes by racial and ethnic subgroup in the US?

Findings

In a serial cross-sectional descriptive study of 1 560 822 individuals with gestational diabetes aged 15 to 44 years with singleton nonanomalous live births, the overall rate of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, transfusion, preterm birth, and neonatal intensive care unit admission significantly increased; cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, large for gestational age, and macrosomia significantly decreased; and maternal intensive care unit admission and small for gestational age did not significantly change from 2014 to 2020.

Meaning

From 2014 through 2020, the frequency of multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes in the US increased among all pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes, with persistence of differences by race and ethnicity.

Abstract

Importance

Gestational diabetes, which increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, has been increasing in frequency across all racial and ethnic subgroups in the US.

Objective

To assess whether the frequency of adverse pregnancy outcomes among those in the US with gestational diabetes changed over time and whether the risk of these outcomes differed by maternal race and ethnicity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Exploratory serial, cross-sectional, descriptive study using US National Center for Health Statistics natality data for 1 560 822 individuals with gestational diabetes aged 15 to 44 years with singleton nonanomalous live births from 2014 to 2020 in the US.

Exposures

Year of delivery and race and ethnicity, as reported on the birth certificate, stratified as non-Hispanic American Indian, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latina, and non-Hispanic White (reference group).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Maternal outcomes of interest included cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and transfusion; neonatal outcomes included large for gestational age (LGA), macrosomia (>4000 g at birth), small for gestational age (SGA), preterm birth, and neonatal ICU (NICU) admission, as measured by the frequency (per 1000 live births) with estimation of mean annual percentage change (APC), disparity ratios, and adjusted risk ratios.

Results

Of 1 560 822 included pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes (mean [SD] age, 31 [5.5] years), 1% were American Indian, 13% were Asian/Pacific Islander, 12% were Black, 27% were Hispanic/Latina, and 48% were White. From 2014 to 2020, there was a statistically significant increase in the overall frequency (mean APC per year) of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension (4.2% [95% CI, 3.3% to 5.2%]), transfusion (8.0% [95% CI, 3.8% to 12.4%]), preterm birth at less than 37 weeks (0.9% [95% CI, 0.3% to 1.5%]), and NICU admission (1.0% [95% CI, 0.3% to 1.7%]). There was a significant decrease in cesarean delivery (−1.4% [95% CI, −1.7% to −1.1%]), primary cesarean delivery (−1.2% [95% CI, −1.5% to −0.9%]), LGA (−2.3% [95% CI, −2.8% to −1.8%]), and macrosomia (−4.7% [95% CI, −5.3% to −4.0%]). There was no significant change in maternal ICU admission and SGA. In comparison with White individuals, Black individuals were at significantly increased risk of all assessed outcomes, except LGA and macrosomia; American Indian individuals were at significantly increased risk of all assessed outcomes except cesarean delivery and SGA; and Hispanic/Latina and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals were at significantly increased risk of maternal ICU admission, preterm birth, NICU admission, and SGA. Differences in adverse outcomes by race and ethnicity persisted through these years.

Conclusions and Relevance

From 2014 through 2020, the frequency of multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes in the US increased among pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes. Differences in adverse outcomes by race and ethnicity persisted.

This study using US National Center for Health Statistics data for more than 1.5 million individuals with gestational diabetes aged 15 to 44 years with singleton nonanomalous live births assesses whether the frequency of adverse pregnancy outcomes among those in the US with gestational diabetes changed over time, and whether the risk of these outcomes differed by maternal race and ethnicity.

Introduction

It was estimated that in the US in 2016, gestational diabetes affected approximately 250 000 pregnant individuals, or 6% of pregnancies.1 In 2015, an estimated 33% of pregnant individuals affected by gestational diabetes experienced an adverse outcome, including cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, and severe maternal morbidity, which includes transfusion and maternal intensive care unit (ICU) admission.2,3,4,5,6 In 2015, an estimated 25% of infants born to individuals with gestational diabetes had an adverse outcome, including preterm birth, growth abnormalities (macrosomia and large and small for gestational age), and neonatal ICU (NICU) admission.5,6 Many adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with gestational diabetes have been causally linked to hyperglycemia based on prior studies that demonstrate a reduction in these outcomes with glycemic control.2,6,7

A recent study using US birth records from 2011 to 2019 demonstrated that the rate of gestational diabetes increased across all race and ethnicity subgroups, but more so among some racial and ethnic minority populations.8 In addition, risk factors for gestational diabetes and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including obesity, advanced maternal age, and social determinants of health, vary by race and ethnicity.9,10,11 These factors add to the generally increasing racial and ethnic disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes.12

Population-based studies on racial and ethnic disparities in gestational diabetes have focused on differences in the rate of diagnosis, rather than adverse pregnancy outcomes.13 Racial and ethnic differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes in this high-risk population may be modifiable through equitable delivery of evidence-based clinical interventions, which reduce the risk of hyperglycemia-associated complications.14

The objective of this descriptive study was to assess whether the frequency of adverse pregnancy outcomes with gestational diabetes changed from 2014 to 2020 and whether the risk of these outcomes differed by maternal race and ethnicity.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

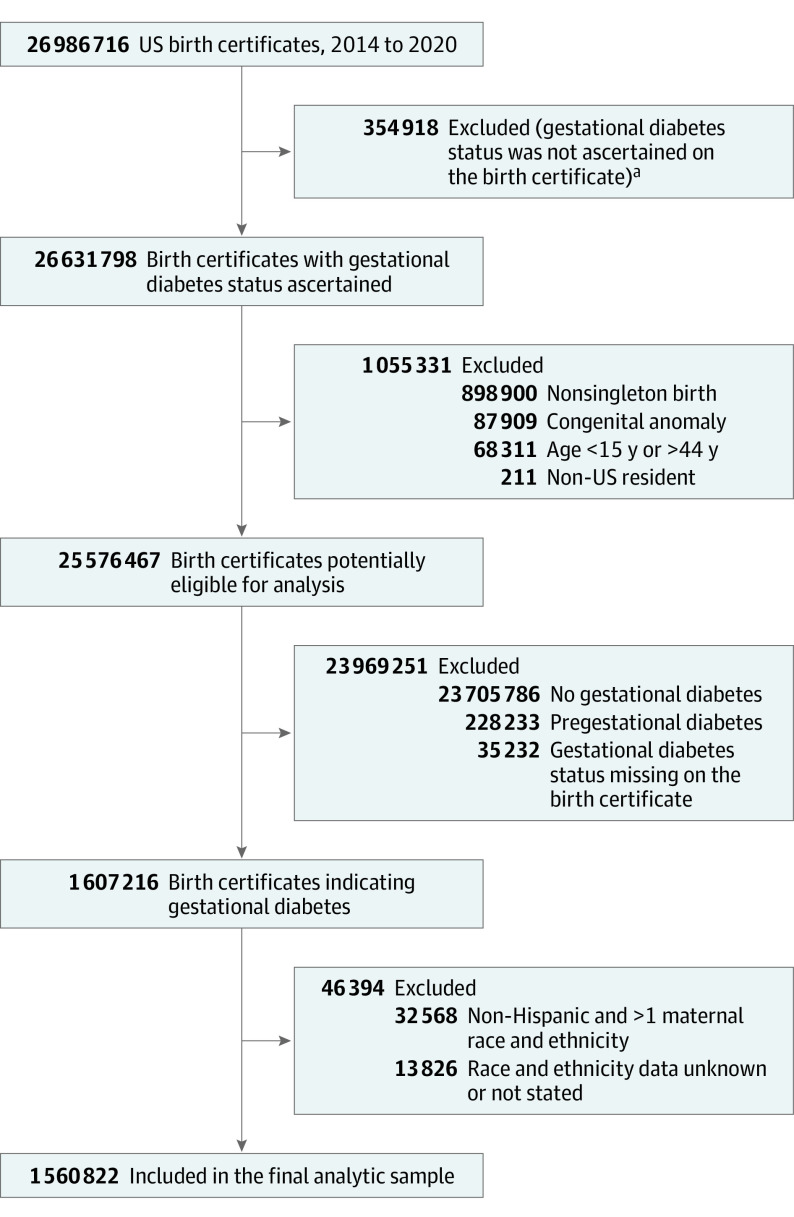

This exploratory study used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Natality Files from 2014 to 2020 to conduct a serial cross-sectional descriptive study. We compared pregnancy outcomes among non-Hispanic American Indian, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic/Latina and with non-Hispanic White pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes. To report and meaningfully compare racial and ethnic group–specific rates and associations using the NCHS bridged-race categories, we excluded individuals with unknown or who identified with other smaller race and ethnic subgroups, as well as those who identified as biracial or multiracial (Figure 1). We included singleton, nonanomalous live births to pregnant individuals with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. A diagnosis of gestational diabetes was defined per the NCHS protocol worksheet as diabetes that was diagnosed during pregnancy, and we excluded those with unknown diabetes status. As coded in this data set, a diagnosis of pregestational diabetes (ie, type 1 or 2 diabetes) was mutually exclusive of a gestational diabetes diagnosis.15 We further excluded individuals younger than 15 or older than 44 years and records from non-US residents to be consistent with recent analyses.8 Because the public use data set of the US Natality Files was deidentified and publicly available for research, the study was reviewed and deemed exempt under category 4 by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University.

Figure 1. Birth Records Included for Primary Analysis in a Study of the Trends in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes With Gestational Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the US From 2014 to 2020.

aPrior to implementation of the 2003 Standard Certificate of Live Birth, state birth certificate data did not include information on gestational diabetes.

Data Collection

Birth certificate data are gathered by birth facilities (or health departments, if a birth occurs outside of a birth facility) using standardized maternal and facility worksheets. Demographic and limited health information are collected on the maternal worksheet, whereas most medical data are collected on the facility worksheet by a health information specialist. NCHS provides extensive guidance regarding where in the medical record data are to be abstracted.16 Birth data are sent to the local state health departments for cleaning and state-level reporting and then to NCHS for federal reporting purposes. Per NCHS guidance, individuals completing the facility worksheet use data from the medical record according to the following priority to identify an individual’s diabetes status: prenatal care record, nursing notes from the delivery admission, delivery admission history and physical, and the labor and delivery summary. Individuals are advised to select prepregnancy diabetes or gestational diabetes, as applicable, but not both.16

Exposures

We compared non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (hereafter referred to as American Indian), non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic/Latina and with non-Hispanic White (reference group) individuals. We used race and ethnicity as reported on the maternal worksheet using categories consistent with recent analyses evaluating gestational diabetes using this data set8 and prior studies demonstrating differences in the rate and risk of outcomes by race and ethnicity.17 Our use of the terms race and ethnicity recognizes these terms as social constructs reflecting a range of processes and does not presuppose a biologic construct.18 Race and ethnicity status is abstracted from the patient’s medical record into predetermined categories, and some institutions may use self-identified data, whereas others may assign race and ethnicity.19 As defined by NCHS, we used bridged-race categories due to differences in state-level categorization of those with multiple racial identifications to permit estimation and comparison of race-specific statistics over time and to facilitate comparison with prior analyses from this data set.20 However, using bridged-race categories may misclassify and exclude some individuals.21

Outcomes

The adverse pregnancy outcomes of interest included maternal outcomes (ie, any cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, gestational hypertension or preeclampsia, ICU admission, and transfusion) and neonatal outcomes (ie, large for gestational age [LGA], small for gestational age [SGA], macrosomia, any preterm birth, and NICU admission). Cesarean delivery included any clinical indication as well as primary or repeat procedures. Primary cesarean delivery was assessed among those without a history of cesarean delivery. Gestational hypertension or preeclampsia was inclusive of eclampsia and superimposed preeclampsia. Maternal ICU admission included admission for any clinical indication during delivery hospitalization. Maternal transfusion was inclusive of any blood products during delivery hospitalization. LGA was defined as a standardized birth weight greater than the 90th percentile, and SGA as less than the 10th percentile. We used an updated 2017 birth weight–for–gestational age reference for the US and reported parity-specific percentiles.22 This newer standard includes the most recent sociodemographic composition in the US and addresses concerns regarding the validity of prior last menstrual period–based references by using an obstetric estimate-based reference. Macrosomia was defined as a birth weight greater than 4000 g. Preterm birth was defined as any birth at less than 37 weeks based on the best obstetric estimate, regardless of clinical indication.

Statistical Analyses

To describe the frequency of study outcomes, we calculated the number of events per 1000 live births among individuals with gestational diabetes per year overall and by race and ethnicity subgroups from 2014 to 2020. To calculate adjusted risk ratios between maternal race and ethnicity and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we used modified Poisson regression with robust error variance. Other covariates of interest, which were selected a priori based on a directed acyclic graph (eFigure in the Supplement), included sociodemographic covariates (education [some high school or less, high school graduate, any college], insurance status or principal source of payment for the delivery [Medicaid, private, self-pay, other], Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC] receipt [yes or no], and delivery year [continuous]); clinical covariates (age [<25, 25-<30, 30-<35, and ≥35 years]; prepregnancy body mass index [BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, World Health Organization obesity classification: underweight or normal {BMI <25}, overweight {BMI 25-<30}, class I obesity {BMI 30-<35}, class II obesity {BMI 35-39}, and class III obesity {BMI ≥40}], tobacco use in pregnancy [yes or no], and chronic hypertension [yes or no]); and obstetric covariates (parity [0, 1, 2, or more] and prior preterm birth [yes or no]). We also adjusted for prior cesarean delivery (yes or no) for all models except for the model with primary cesarean delivery as the outcome, and adjusted for infant sex (male or female) for all models with an infant outcome. We did not adjust for gestational age at birth given that it could lie on the causal pathway between race and pregnancy outcomes, and its inclusion may result in collider bias.23

To describe the change in rates of adverse outcomes over time overall and by racial and ethnic subgroup, we calculated the mean or average annual percentage change (APC). We used Joinpoint Regression statistical software version 4.7.0 (National Cancer Institute). Briefly, Joinpoint Regression accounts for potential nonlinear trends by inflection points and accounts for identified nonlinear trends by weighting for the trend segment.24 To assess changes in racial and ethnic disparities over time, we calculated (1) the disparity ratio in 2014 and 2020, which is the relative risk between each racial and ethnic subgroup and the largest group (ie, White individuals) and (2) the interaction between each racial and ethnic minority subgroup vs White individuals and year (represented as a continuous variable), modeled in the above multivariable regression models.

As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the above trend analysis, including mean APC, among nulliparous pregnant individuals who may be at lower risk of adverse outcomes compared with parous individuals with a history of that outcome. We also reperformed the above regression models: (1) restricted to 2016 to 2019, which were the years by which all US states and reporting areas had adopted the 2003 birth certificate revision and (2) among only nulliparous pregnant individuals, consistent with the exclusion criteria of a recent analysis reporting rates of gestational diabetes using these birth certificate data.8 Like prior analyses using this data set, missing data for covariates were represented in the model with a categorical-variable term given the low frequency of missing values, rather than as imputed values. All statistical tests were 2-sided and statistical significance was assessed based on a 95% CI excluding the null value. Given the potential for type I error due to the large number of statistical comparisons, all analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Maternal Characteristics

Among 26 986 716 live birth records in the US from 2014 to 2020, 26 631 798 (99%) had gestational diabetes status recorded, of which those with nonsingleton births, age younger than 15 years or older than 44 years, non-US residents, and with congenital anomalies (Figure 1) were excluded from further analysis. Among the 1 607 216 of 26 986 716 birth records (6%) with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes who met the above criteria, we further excluded those missing reported maternal race and ethnicity and those identified outside of the bridged–race and ethnicity categories assessed in this analysis. The final study sample included 1 560 822 of 1 607 216 singleton, nonanomalous live births (97%) to individuals with gestational diabetes. Differences in characteristics between the final analytic sample and excluded birth records are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Among the study population, the median age was 31 years (IQR, 27-35), 66% were multiparous, 86% had a high school education or greater, and 39% were enrolled in WIC. Most had health insurance (42% Medicaid and 51% private) (Table) and 80% initiated prenatal care in the first trimester. Most (73%) had overweight BMI or obesity when initiating prenatal care.

Table. Maternal Characteristics of Individuals With Singleton Nonanomalous Live Births and Gestational Diabetes by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2014 to 2020.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian (n = 19 261) | Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 195 982) | Black (n = 185 629) | Hispanic/Latina (n = 415 477) | White (n = 744 473) | Overall (N = 1 560 822) | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (25-34) | 33 (30-36) | 31 (26-35) | 31 (27-35) | 31 (27-35) | 31 (27-35) |

| <25 | 4135 (21.5) | 7821 (4.0) | 30 236 (16.3) | 62 370 (15.0) | 97 374 (13.1) | 201 936 (12.9) |

| 25 to <30 | 5529 (28.7) | 39 205 (20.0) | 48 342 (26.0) | 101 082 (24.3) | 194 615 (26.1) | 388 773 (24.9) |

| 30 to <35 | 5431 (28.2) | 78 962 (40.3) | 56 196 (30.3) | 124 698 (30.0) | 255 310 (34.3) | 520 597 (33.4) |

| ≥35 | 4166 (21.6) | 69 994 (35.7) | 50 855 (27.4) | 127 327 (30.7) | 197 174 (26.5) | 449 516 (28.8) |

| Delivery year | ||||||

| 2014 | 2532 (13.2) | 22 392 (11.4) | 22 875 (12.3) | 50 491 (12.2) | 93 946 (12.6) | 192 236 (12.3) |

| 2015 | 2623 (13.6) | 23 666 (12.1) | 23 545 (12.7) | 52 905 (12.7) | 96 922 (13.0) | 199 661 (12.8) |

| 2016 | 2751 (14.3) | 27 519 (14.0) | 25 316 (13.6) | 57 733 (13.9) | 101 956 (13.7) | 215 275 (13.8) |

| 2017 | 2636 (13.7) | 29 163 (14.9) | 26 532 (14.3) | 59 601 (14.4) | 106 699 (14.3) | 224 631 (14.4) |

| 2018 | 2801 (14.5) | 29 976 (15.3) | 27 209 (14.7) | 61 115 (14.7) | 110 495 (14.8) | 231 596 (14.8) |

| 2019 | 2882 (15.0) | 31 053 (15.8) | 27 876 (15.0) | 63 127 (15.2) | 112 743 (15.1) | 237 681 (15.2) |

| 2020 | 3036 (15.8) | 32 213 (16.4) | 32 276 (17.4) | 70 505 (17.0) | 121 712 (16.4) | 259 742 (16.6) |

| Multiparous | 14 319/19 210 (74.5) | 112 925/195 670 (57.7) | 128 631/185 102 (69.5) | 308 980/414 790 (74.5) | 465 342/742 820 (62.7) | 1 030 197/1 557 592 (66.1) |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy | 2414/19 059 (12.7) | 1296/194 916 (0.7) | 9409/184 346 (5.1) | 6574/413 608 (1.6) | 77 285/741 013 (10.4) | 96 978/1 552 942 (6.2) |

| Education | ||||||

| No. | 19 143 | 193 543 | 184 089 | 409 667 | 740 950 | 740 950 |

| Some high school or less | 3182 (16.6) | 14 243 (7.4) | 20 442 (11.1) | 130 846 (31.9) | 44 791 (6.1) | 213 504 (13.8) |

| High school graduate | 6910 (36.1) | 25 575 (13.2) | 57 158 (31.1) | 123 051 (30.0) | 160 026 (21.6) | 372 720 (24.1) |

| Any college | 9051 (47.3) | 153 725 (79.4) | 106 489 (57.9) | 155 770 (38.0) | 536 133 (72.4) | 961 168 (62.1) |

| Insurance | ||||||

| No. | 19 042 | 195 122 | 184 662 | 413 219 | 740 031 | 1 552 076 |

| Medicaid | 12 396 (65.1) | 52 425 (26.9) | 113 903 (61.7) | 248 750 (60.2) | 229 189 (31.0) | 656 663 (42.3) |

| Private insurance | 4091 (21.5) | 130 567 (66.9) | 60 826 (32.9) | 119 952 (29.0) | 475 057 (64.2) | 790 493 (50.9) |

| Self-pay | 214 (1.1) | 6406 (3.3) | 3872 (2.1) | 26 797 (6.5) | 11 197 (1.5) | 48 486 (3.1) |

| Otherb | 2341 (12.3) | 5724 (2.9) | 6061 (3.3) | 17 720 (4.3) | 24 588 (3.3) | 56 434 (3.6) |

| WIC enrolled | 10 834/18 914 (57.3) | 44 584/192 157 (23.2) | 103 079/182 980 (56.3) | 243 799/410 991 (59.3) | 197 284/736 634 (26.8) | 599 580/1 541 676 (38.9) |

| Prenatal care | ||||||

| No. | 18 871 | 192 069 | 180 129 | 406 970 | 731 591 | 1 529 630 |

| Started in first trimester | 12 872 (68.2) | 157 422 (82.0) | 128 804 (71.5) | 304 020 (74.7) | 618 643 (84.6) | 1 221 761 (79.9) |

| Started in second trimester | 4313 (22.9) | 26 245 (13.7) | 38 333 (21.3) | 79 705 (19.6) | 88 894 (12.2) | 237 490 (15.5) |

| Started in third trimester | 1686 (8.9) | 8402 (4.4) | 12 992 (7.2) | 23 245 (5.7) | 24 054 (3.3) | 70 379 (4.6) |

| Pregestational BMI | ||||||

| No. | 18 901 | 191 647 | 179 970 | 404 414 | 730 871 | 1 525 803 |

| Mean (SD) | 32.6 (7.34) | 25.5 (5.22) | 32.7 (8.16) | 30.9 (6.96) | 30.7 (7.94) | 30.4 (7.67) |

| <25, underweight/healthy | 2816 (14.9) | 101 166 (52.8) | 29 944 (16.6) | 79 635 (19.7) | 198 932 (27.2) | 412 493 (27.0) |

| 25 to <30, overweight | 4366 (23.1) | 56 719 (29.6) | 44 035 (24.5) | 119 732 (29.6) | 178 293 (24.4) | 403 145 (26.4) |

| 30 to <35, class I obesity | 5169 (27.4) | 23 493 (12.3) | 43 767 (24.3) | 104 138 (25.8) | 151 827 (20.8) | 328 394 (21.5) |

| 35 to <40, class II obesity | 3626 (19.2) | 7204 (3.8) | 30 128 (16.7) | 58 170 (14.4) | 104 680 (14.3) | 203 808 (13.4) |

| ≥40, class III obesity | 2924 (15.5) | 3065 (1.6) | 32 096 (17.8) | 42 739 (10.6) | 97 139 (13.3) | 177 963 (11.7) |

| Chronic hypertension | 977 (5.1) | 4241 (2.2) | 16 443 (8.9) | 13 427 (3.2) | 36 148 (4.9) | 71 236 (4.6) |

| Prior cesarean delivery | 3785 (19.7) | 36 983 (18.9) | 44 455 (24.0) | 97 221 (23.4) | 141 438 (19.0) | 323 882 (20.8) |

| Prior preterm birth among multipara | 1259/14 319 (8.8) | 5890/112 925 (5.2) | 12 705/128 631 (9.9) | 20 486/308 980 (6.6) | 34 689/465 342 (7.5) | 75 029/1 030 197 (7.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Percentages sum to the total nonmissing data for each covariate.

Other insurance includes Indian Heath Service, TRICARE, and other government sources.

One percent were American Indian, 13% Asian/Pacific Islander, 12% Black, 27% Hispanic/Latina, and 48% White (reference) (Table). American Indian, Black, and Hispanic/Latina individuals were more likely to be parous, have lower educational attainment, be Medicaid insured, be enrolled in WIC, start prenatal care after the first trimester, and have overweight BMI or obesity compared with White individuals. Black individuals were more likely to have chronic hypertension, and both American Indian and Black individuals were also more likely to have a prior preterm birth. Black and Hispanic/Latina individuals were more likely to have a prior cesarean delivery. In contrast, Asian/Pacific Islander individuals were more likely to be nulliparous, have higher educational level, and have private insurance, while they were less likely to be enrolled in WIC, have overweight BMI or obesity, have chronic hypertension, or have a prior preterm birth compared with White individuals.

Frequency of Adverse Outcomes

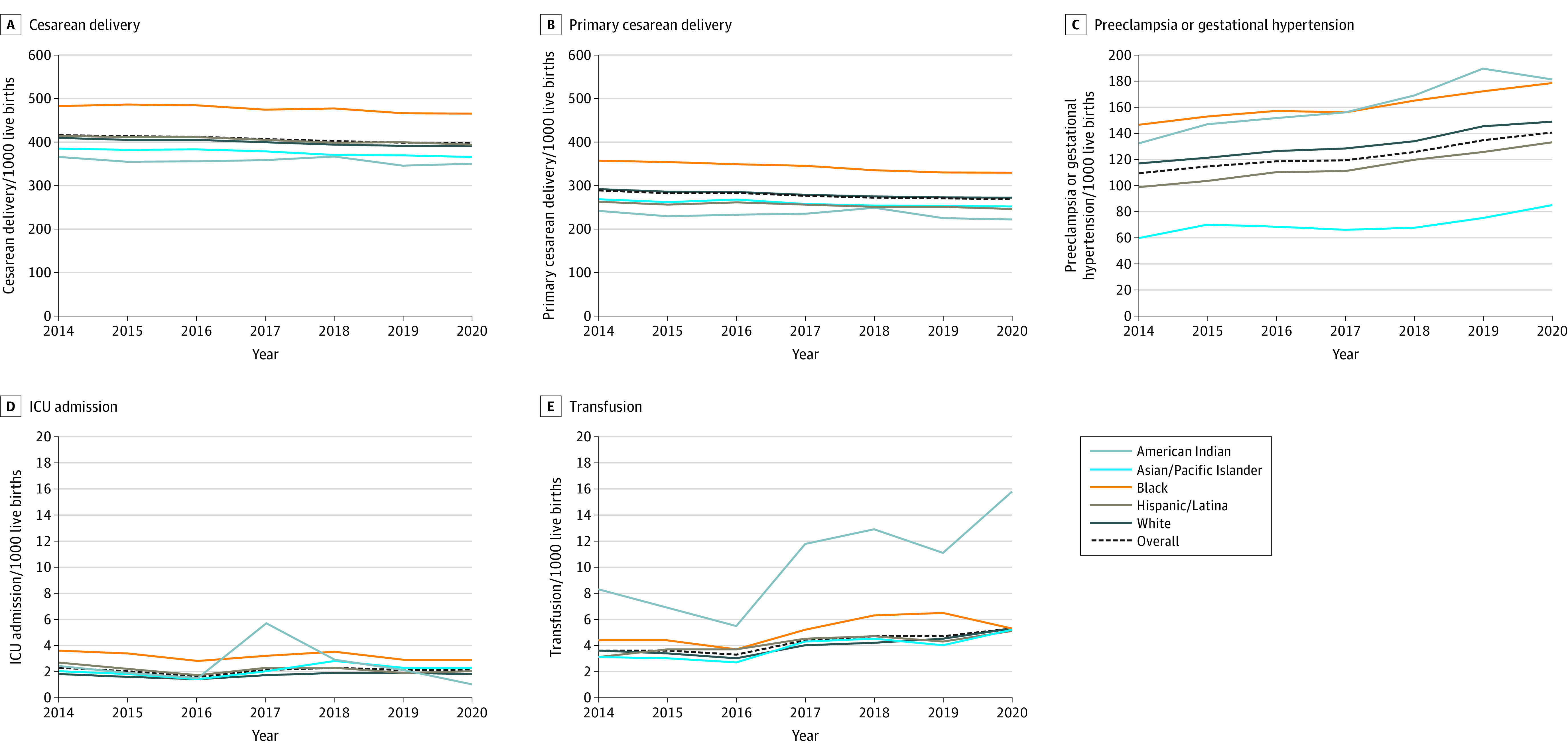

From 2014 to 2020, the frequency of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension significantly increased from 109.2 (95% CI, 107.8 to 110.6) to 140.7 (95% CI, 139.3 to 142.0) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was 4.2% (95% CI, 3.3% to 5.2%) per year (Figure 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The frequency of maternal transfusion also significantly increased from 3.5 (95% CI, 3.3 to 3.8) to 5.3 (95% CI, 5.0 to 5.6) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was 8.0% (95% CI, 3.8% to 12.4%) per year. The frequency of cesarean delivery significantly decreased from 416.1 (95% CI, 413.9 to 418.3) to 397.6 (95% CI, 395.8 to 399.5) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was −1.4% (95% CI, −1.7% to −1.1%) per year. Similarly, the frequency of primary cesarean delivery significantly decreased from 289.0 (95% CI, 286.7 to 291.2) to 269.1 (95% CI, 267.1 to 271.0) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was −1.2% (95% CI, −1.5% to −0.9%) per year. The frequency and rate of maternal ICU admission did not significantly change in the 7-year period under study.

Figure 2. Maternal Outcomes (Frequency per 1000 Live Births) From 2014 to 2020 of Pregnant Individuals Aged 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes.

The numbers of pregnant individuals for each outcome are as follows: cesarean delivery (n = 1 560 511), primary cesarean delivery (n = 1 236 666), preeclampsia or gestational hypertension (n = 1 560 822), intensive care unit (ICU) admission (n = 1 559 445), and transfusion (n = 1 559 445). The y-axes vary in range. Corresponding data, including the calculated annual percentage change, are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

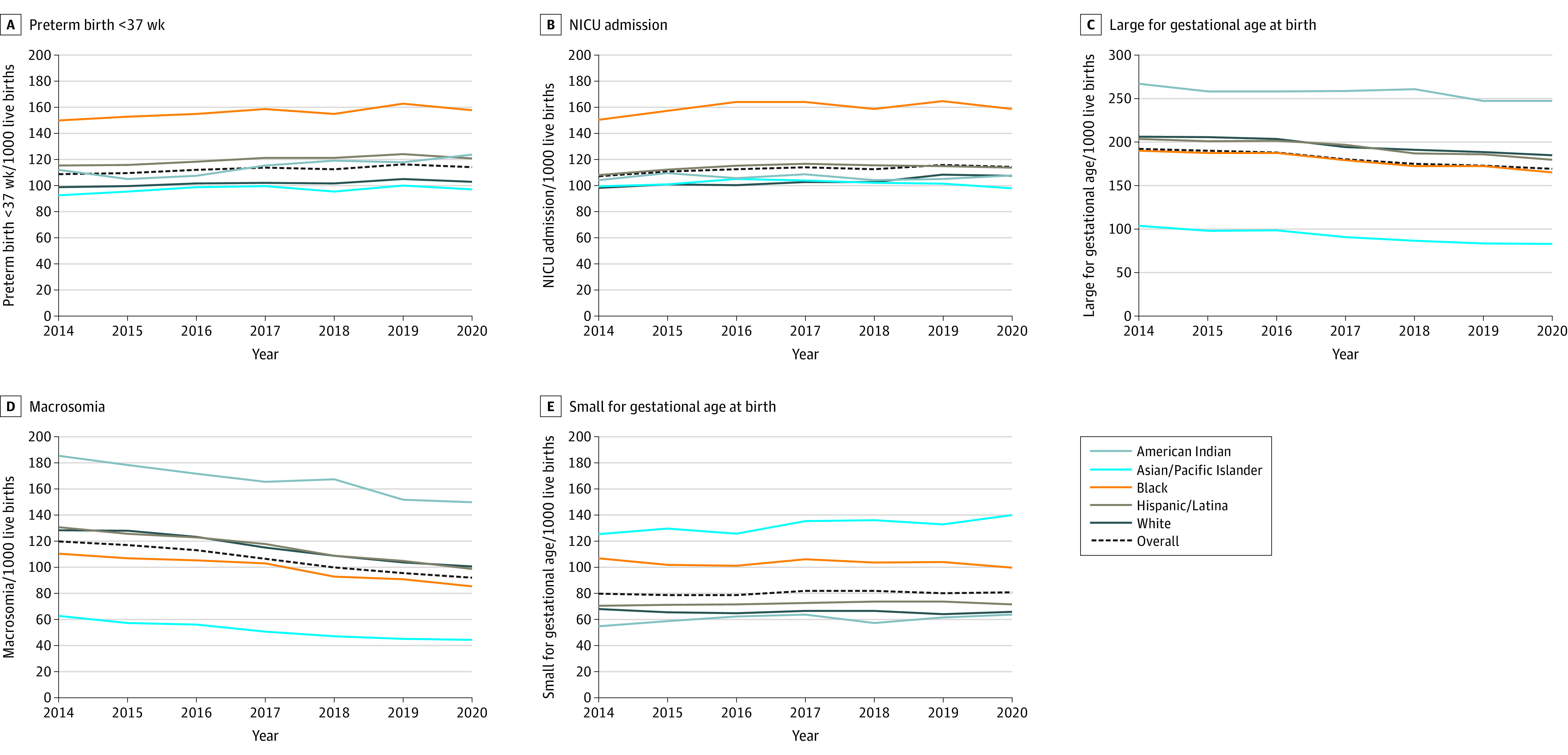

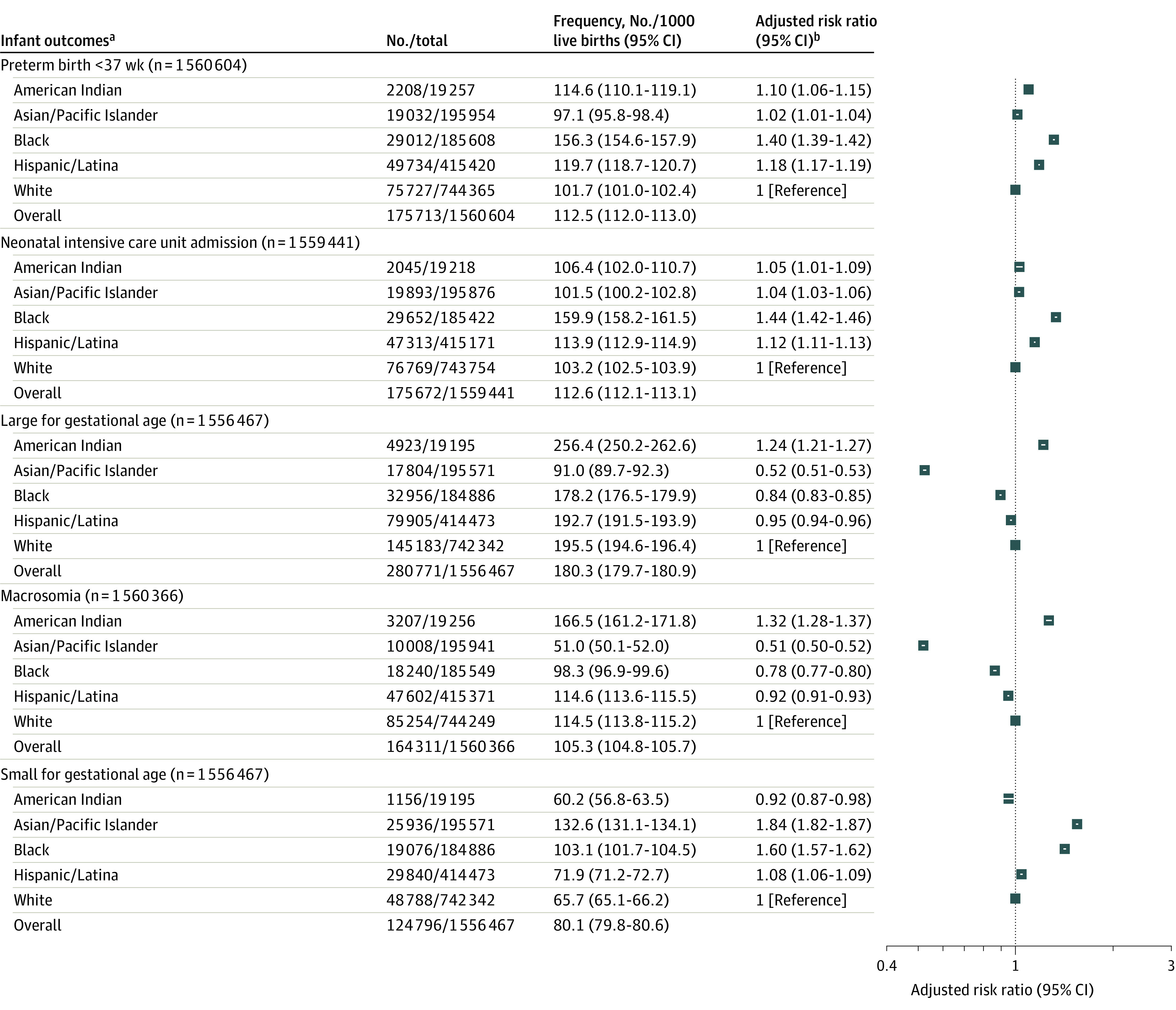

For infant outcomes, the frequency of preterm birth significantly increased from 108.6 (95% CI, 107.2 to 110.0) to 114.1 (95% CI, 112.9 to 115.3) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.3% to 1.5%) per year (Figure 3; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The frequency of NICU admission significantly increased from 107.2 (95% CI, 105.8 to 108.5) to 114.4 (95% CI, 113.1 to 115.6) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was 1.0% (95% CI, 0.3% to 1.7%) per year. The frequency of LGA significantly decreased from 192.3 (95% CI, 190.6 to 194.1) to 169.0 (95% CI, 167.6 to 170.4) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was −2.3% (95% CI, −2.8% to −1.8%) per year. Similarly, the frequency of macrosomia significantly decreased from 119.9 (95% CI, 118.4 to 121.3) to 91.7 (95% CI, 90.6 to 92.8) per 1000 live births, and the mean APC was −4.7% (95% CI, −5.3% to −4.0%) per year. The frequency and rate of SGA did not significantly change in the 7-year period under study.

Figure 3. Infant Outcomes (Frequency per 1000 Live Births) From 2014 to 2020 to Pregnant Individuals Aged 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes.

Preterm birth included a birth at less than 37 weeks based on the best obstetric estimate for any indication. Large for gestational age was defined as a parity-specific standardized birth weight greater than the 90th percentile, and small for gestational age as less than the 10th percentile. Macrosomia was defined as a birth weight greater than 4000 g. The y-axes vary in range. The numbers of infants for each outcome are as follows: preterm birth (n = 1 560 604), neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission (n = 1 559 441), large for gestational age (n = 1 556 467), macrosomia (n = 1 560 366), and small for gestational age (n = 1 556 467). Corresponding data, including the calculated annual percentage change, are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

The above overall trends held for nulliparous pregnant individuals (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

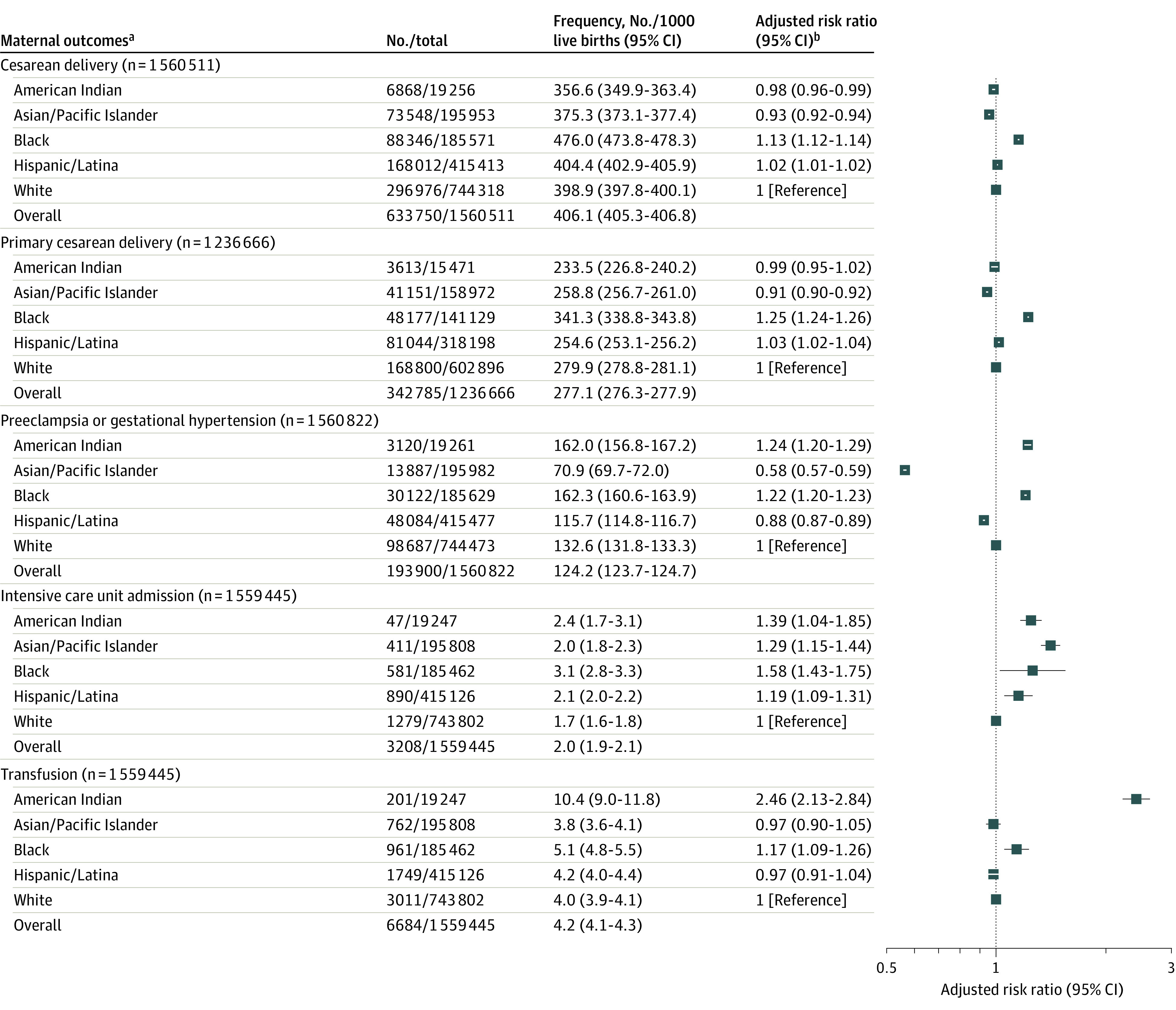

Risk of Adverse Outcome by Race and Ethnicity

Black individuals were at significantly increased risk of most assessed adverse pregnancy outcomes, including cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, maternal ICU admission, transfusion, SGA, preterm birth, and NICU admission compared with White individuals (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Conversely, they had a significantly lower risk of LGA and macrosomia. American Indian individuals were also at significantly increased risk of most adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, maternal ICU admission, transfusion, preterm birth, NICU admission, LGA, and macrosomia compared with White individuals. They had a significantly lower risk of SGA, cesarean delivery, and primary cesarean delivery. Hispanic/Latina individuals were at significantly increased risk of cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, maternal ICU admission, SGA, preterm birth, and NICU admission, but at significantly lower risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, LGA, and macrosomia. Asian/Pacific Islander individuals were at significantly increased risk of maternal ICU admission, SGA, preterm birth, and NICU admission, but at significantly lower risk of cesarean delivery, primary cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, LGA, and macrosomia.

Figure 4. Maternal Outcomes and Association Between Race and Ethnicity Among Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, US Natality Files, 2014-2020.

aMaternal outcomes of intensive care unit admission and transfusion were ascertained at delivery hospitalization.

bAll models adjusted for age; parity; tobacco use in pregnancy; chronic hypertension; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children receipt; prepregnancy body mass index; education status; insurance status; prior preterm birth; and delivery year. All models adjusted for prior cesarean delivery except primary cesarean delivery. Model for primary cesarean delivery conducted among individuals without a history of cesarean delivery.

Figure 5. Infant Outcomes and Association Between Race and Ethnicity Among Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, US Natality Files, 2014-2020.

aInfant outcomes of neonatal intensive care unit admission, large for gestational age (LGA), macrosomia, and small for gestational age (SGA) also adjusted for infant sex.

bAll models adjusted for age; tobacco use in pregnancy; chronic hypertension; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children receipt; prepregnancy body mass index; education status; insurance status; prior preterm birth; and delivery year. All models, except LGA and SGA, adjusted for parity, because parity-standardized LGA and SGA definitions were used.

In sensitivity analyses, the above associations generally held when restricted to 2016 to 2020 (eTable 4 in the Supplement) and when restricted to only nulliparous pregnant individuals (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Change Over Time in the Frequency of Adverse Outcome by Race and Ethnicity Subgroups

From 2014 to 2020, the rate of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension significantly increased for all racial and ethnic subgroups, ranging from a mean APC of 3.2% (95% CI, 2.5% to 4.0%) per year for Black individuals to 5.7% (95% CI, 3.7% to 7.8%) per year for American Indian individuals (Figure 2; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The rate of maternal transfusion significantly increased for all racial and ethnic subgroups except Black individuals, ranging from a mean APC of 7.2% (95% CI, 3.1% to 11.4%) per year for Hispanic/Latina individuals to 14.0% (95% CI, 2.5% to 26.9%) per year for American Indian individuals. The rate of cesarean delivery significantly decreased slightly for all racial and ethnic subgroups, ranging from a mean APC of −0.5% to −0.9% per year. The rate of primary cesarean delivery also significantly decreased for all racial and ethnic subgroups, except American Indian individuals. The rate of maternal ICU admission did not significantly change.

For infant outcomes, the rate of preterm birth significantly increased for all subgroups, ranging from a mean APC of 0.8% (95% CI, 0.3% to 1.4%) per year for White individuals to 2.3% (95% CI, 0.6% to 4.1%) per year for American Indian individuals, except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals (Figure 3; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The rate of NICU admission significantly increased for White individuals (mean APC, 1.6% [95% CI, 0.9% to 2.3%] per year) and Hispanic/Latina individuals (mean APC, 0.9% [95% CI, 0.7% to 1.1%] per year), for which an inflection point was identified in 2016 for Black, Hispanic/Latina, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. The rate of SGA significantly increased for Asian/Pacific Islander individuals, with a mean APC of 1.7% (95% CI, 0.5% to 2.9%) per year, and Hispanic individuals, with a mean APC of 0.4% (95% CI, 0.2% to 0.5%). The rate of LGA significantly decreased for all subgroups, ranging from a mean APC of −1.1% (95% CI, −1.9% to −0.3%) per year for American Indian individuals to −3.9% (95% CI, −4.9% to −2.9%) per year for Asian/Pacific Islander individuals (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The rate of macrosomia also significantly decreased for all subgroups.

The observed racial and ethnic differences in the risk of adverse outcomes as measured by disparity ratios persisted from 2014 to 2020 (eTable 6 in the Supplement). While the magnitude of most differences remained similar over time, those for preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and SGA significantly increased, while that of maternal ICU admission, NICU admission, LGA, and macrosomia significantly decreased for some racial and ethnic subgroups (interaction P < .05) (eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Among pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes in the US, the frequencies of multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes increased from 2014 to 2020. There were differences in rates of adverse outcomes by race and ethnicity, with American Indian and Black individuals generally at the highest risk of adverse outcomes compared with White individuals. These differences in rates of adverse outcomes persisted over time.

The current analysis, which was focused on pregnancy outcomes, builds on a recent publication using US vital statistics between 2011 and 2019 that found the prevalence of gestational diabetes was increasing among all race and ethnicity subgroups and in all age groups, but more so among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic/Latina subgroups relative to White individuals.8 Prior cross-sectional studies have also documented differences in the risk of gestational diabetes by race and ethnicity subgroup and country of birth.25 It is possible that the increasing rates of preterm birth and SGA for some racial and ethnic subgroups were related to increasing rates of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension. More than 20% of SGA infants and preterm births may be attributable to preeclampsia, and its incidence has continued to increase in concert with increasing rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease among pregnant individuals.26 Randomized clinical trials have suggested that improving glycemic control reduces the risk of preeclampsia in pregnancies affected by gestational diabetes.2,6

In contrast, the rates of cesarean delivery, LGA, and macrosomia slightly decreased over time.27 This finding may reflect utilization of more stringent criteria for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes28 and more intensive medical management,29 including changing patterns of preferred pharmacotherapy (more insulin use).30 It is possible that these clinical interventions aimed at improved glycemic control may have resulted in less fetal overgrowth and fewer cesarean deliveries.6,29

Many of the observed racial and ethnic disparities in adverse outcomes have been previously noted, regardless of gestational diabetes status.12,26,31 American Indian individuals, who were at increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, are also at increased risk of gestational diabetes and maternal morbidity.32 The increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes among Asian/Pacific Islander and Hispanic/Latina individuals with gestational diabetes is likely compounded by the increased rates of gestational diabetes in these groups as observed in previous studies.27 The increasing prevalence of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, in particular among Black individuals, is consistent with recent data highlighting the contribution of cardiovascular disease inclusive of preeclampsia to maternal morbidity and mortality.33

Variations in the rate and risk of adverse outcomes by race and ethnicity subgroup are likely multifactorial. Systemic racism, which includes racial biases, power structures, and policies embedded in institutions, may limit access to quality health care and to resources that support changes in diet and lifestyle that promote health.11 The differences in risk factors and differential exposures are associated with social determinants of health, which may include the neighborhood and physical environment, diet quality and the food environment, access to quality health care, and social context with diabetes-related outcomes.34 These social determinants of health may affect glycemic control and in turn the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.35

Because this analysis was restricted to pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes, the extent to which gestational diabetes contributes to differential pregnancy outcomes in the overall population requires further study. Further research could focus on greater understanding of racial and ethnic differences in the management of gestational diabetes, including health care utilization, type of pharmacotherapy, and glycemic control; differential risk factors for gestational diabetes by race and ethnicity; and ways to decrease the likelihood of developing gestational diabetes.13

The current analysis focused on relatively frequent adverse outcomes, in comparison with more severe measures of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, for which the relative risk is even higher for Black individuals.12 Baseline risk factors for adverse outcomes varied by race and ethnicity; these may also affect the risk of gestational diabetes and its severity. Other factors unmeasured in this analysis may also increase the risk of adverse outcomes for racial and ethnic minority groups include discrimination,36 variations in delivery of guideline-based care, failure to rescue to prevent clinically important deterioration, and birth hospital.37 In addition, screening and diagnostic criteria used for gestational diabetes diagnosis by individual institutions may have changed during the study period and affected the composition of the race and ethnicity groups included in this analysis.38

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because the analysis was based on administrative data, it could not determine the mechanisms underlying observed racial and ethnic differences or provide inferences regarding how maternal care can be improved to reduce these differences.

Second, findings from the aggregated groups in this analysis cannot necessarily be extrapolated to any subgroup within these bridged-race categories and may not be reflective of trends or associations of these smaller subgroups.8 NCHS bridged-race categories provide single race-specific rates21 and may fail to accurately represent individuals who may increasingly identify as biracial or multiracial.39

Third, while the analyses adjusted for measures of socioeconomic status, it did not directly measure social determinants of health, such as food insecurity and characteristics of a neighborhood’s built environment. It did not evaluate the degree to which patient, hospital, and clinician factors may also account for adverse outcomes.

Fourth, data before 2016 may be biased because not all states had adopted the 2003 birth certificate revision; however, the findings were consistent in sensitivity analyses restricted to 2016 to 2020.

Fifth, vital statistics are a deidentified publicly available resource and could not distinguish individuals who had multiple children during the study period. The current analysis did not account for this, but the results were similar when restricted to pregnancies in nulliparous individuals.

Sixth, it is possible that cases of pregestational diabetes or gestational diabetes were miscoded as each other, and this may occur more frequently in certain racial or ethnic groups.11 Validation studies assessing agreement between birth certificate and medical record data have found sensitivity of 46% to 83% and specificity of 98%.40

Conclusions

From 2014 through 2020, the frequency of multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes in the US increased among pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes. Differences in adverse outcomes by race and ethnicity persisted.

eTable 1. Maternal Characteristics Overall and by Whether or Not Included in the Analytic Sample, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 2. Maternal and Infant Outcomes From 2014 to 2020 to Pregnant Individuals Age 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes

eTable 3. Maternal and Infant Outcomes in Nulliparous Pregnant Individuals Age 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 4. Association Between Race and Ethnicity and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Among Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, Restricted to 2016-2020

eTable 5. Association Between Race and Ethnicity and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Restricted to Nulliparous Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 6. Disparity Ratios for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Comparing Each Subgroup to White Individuals (Reference), U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 7. P-values for Interaction of Race/Ethnicity (Referent White Individuals) With Year of Delivery, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eFigure. Directed Acyclic Graph

References

- 1.Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, Bullard KM. Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live birth—United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(43):1201-1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network . A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1339-1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillay J, Donovan L, Guitard S, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326(6):539-562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourad M, Wen T, Friedman AM, Lonier JY, D’Alton ME, Zork N. Postpartum readmissions among women with diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):80-89. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camelo Castillo W, Boggess K, Stürmer T, Brookhart MA, Benjamin DK Jr, Jonsson Funk M. Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with glyburide vs insulin in women with gestational diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):452-458. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Solà I, Roqué M, Gich I, Corcoy R. Glibenclamide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS; Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) Trial Group . Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2477-2486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660-669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pu J, Zhao B, Wang EJ, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in gestational diabetes prevalence and contribution of common risk factors. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29(5):436-443. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Ren X, He L, Li J, Zhang S, Chen W. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108044. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(1):258-279. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDorman MF, Thoma M, Declcerq E, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality in the United States using enhanced vital records, 2016-2017. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(9):1673-1681. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powe CE, Carter EB. Racial and ethnic differences in gestational diabetes: time to get serious. JAMA. 2021;326(7):616-617. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wexler DJ, Powe CE, Barbour LA, et al. Research gaps in gestational diabetes mellitus: executive summary of a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(2):496-505. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanhope KK, Joseph NT, Platner M, et al. Validation of ICD-10 codes for gestational and pregestational diabetes during pregnancy in a large, public hospital. Epidemiology. 2021;32(2):277-281. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Vital Statistics . Guide to completing the facility worksheets for the certificate of live birth and report of fetal death. Updated September 2019. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/GuidetoCompleteFacilityWks.pdf

- 17.Tutlam NT, Liu Y, Nelson EJ, Flick LH, Chang JJ. The effects of race and ethnicity on the risk of large-for-gestational-age newborns in women without gestational diabetes by prepregnancy body mass index categories. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(8):1643-1654. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2256-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine . Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarneri CE, Dick C. Methods of assigning race and Hispanic origin to births from vital statistics data. Published 2012. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/pdf/Guarneri_2012FCSM_X-B.pdf

- 20.Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N, et al. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. Vital Health Stat 2. 2003;2(135):1-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker JD, Schenker N, Ingram DD, Weed JA, Heck KE, Madans JH. Bridging between two standards for collecting information on race and ethnicity: an application to Census 2000 and vital rates. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(2):192-205. doi: 10.1177/003335490411900213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aris IM, Kleinman KP, Belfort MB, Kaimal A, Oken E. A 2017 US reference for singleton birth weight percentiles using obstetric estimates of gestation. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20190076. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1062-1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedderson MM, Darbinian JA, Ferrara A. Disparities in the risk of gestational diabetes by race-ethnicity and country of birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24(5):441-448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01140.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JD, Louis JM. Does race or ethnicity play a role in the origin, pathophysiology, and outcomes of preeclampsia? an expert review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;20:30769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen BT, Cheng YW, Snowden JM, Esakoff TF, Frias AE, Caughey AB. The effect of race/ethnicity on adverse perinatal outcomes among patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):322.e1-322.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauring JR, Kunselman AR, Pauli JM, Repke JT, Ural SH. Comparison of healthcare utilization and outcomes by gestational diabetes diagnostic criteria. J Perinat Med. 2018;46(4):401-409. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sridhar SB, Ferrara A, Ehrlich SF, Brown SD, Hedderson MM. Risk of large-for-gestational-age newborns in women with gestational diabetes by race and ethnicity and body mass index categories. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1255-1262. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318291b15c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesh KK, Chiang CW, Castillo WC, et al. Changing patterns in glyburide, metformin, and insulin prescription for gestational diabetes treatment during a time of guideline change, 2016-2018. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;129(3):473-483. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Zivin K, Terplan M, Mhyre JM, Dalton VK. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of severe maternal morbidity in the United States, 2012-2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1158-1166. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson KG, Spicer P, Peercy MT. Obesity, diabetes, and birth outcomes among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(12):2548-2556. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2080-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramer CK, Campbell S, Retnakaran R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2019;62(6):905-914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4840-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogunwole SM, Golden SH. Social determinants of health and structural inequities-root causes of diabetes disparities. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(1):11-13. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jardine J, Walker K, Gurol-Urganci I, et al. ; National Maternity and Perinatal Audit Project Team . Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: a national cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1905-1912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01595-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacGregor C, Freedman A, Keenan-Devlin L, et al. Maternal perceived discrimination and association with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(4):100222. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mujahid MS, Kan P, Leonard SA, et al. Birth hospital and racial and ethnic differences in severe maternal morbidity in the state of California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(2):219.e1-219.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Ogasawara KK, et al. A pragmatic, randomized clinical trial of gestational diabetes screening. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(10):895-904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarrín OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care. 2020;58(1):e1-e8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devlin HM, Desai J, Walaszek A. Reviewing performance of birth certificate and hospital discharge data to identify births complicated by maternal diabetes. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(5):660-666. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0390-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Maternal Characteristics Overall and by Whether or Not Included in the Analytic Sample, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 2. Maternal and Infant Outcomes From 2014 to 2020 to Pregnant Individuals Age 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes

eTable 3. Maternal and Infant Outcomes in Nulliparous Pregnant Individuals Age 15 to 44 Years With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 4. Association Between Race and Ethnicity and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Among Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, Restricted to 2016-2020

eTable 5. Association Between Race and Ethnicity and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Restricted to Nulliparous Pregnant Individuals With Gestational Diabetes, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 6. Disparity Ratios for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Comparing Each Subgroup to White Individuals (Reference), U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eTable 7. P-values for Interaction of Race/Ethnicity (Referent White Individuals) With Year of Delivery, U.S. Natality Files, 2014-2020

eFigure. Directed Acyclic Graph