Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Mouse models of alcohol-associated liver disease vary greatly in their ease of implementation and the pathology they produce. This ranges from steatosis and mild inflammation in Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet, and severe inflammation, fibrosis and pyroptosis seen in the Tsukamoto-French intragastric feeding model. Implementation of all these models is limited by the labor-intensive nature of the protocols and the specialized skills necessary for successful intragastric feeding. We thus sought to develop a new model that would reproduce features of alcohol-induced inflammation and fibrosis with minimal operational requirements.

METHODS:

Mice were fed ad libitum with a pelleted high fat western diet (40% calories from fat) and alcohol added to the drinking water. We found that optimal alcohol consumption occurred when alcohol concentration alternated between 20% for 4 days and 10% for 3 days per week. Control mice received western diet pellets with water alone and the total feeding duration was 16 weeks.

RESULTS:

Alcohol consumption was 18–20 g/kg/day in males and 20–22 g/kg/day in females. Mice in the alcohol groups developed elevated serum ALT and AST after 12 weeks in males and 10 weeks in females. At 16 weeks, both males and females developed liver inflammation, steatosis and pericellular fibrosis. Control mice on western diet without alcohol had mild steatosis only. Alcohol fed mice showed reduced mRNA and protein expression of HNF4α, the master regulator of hepatocyte differentiation, downregulation of which is a known driver of hepatocellular failure in alcoholic hepatitis.

CONCLUSION:

A simple to administer, 16-week western diet alcohol model recapitulates the inflammatory, fibrotic and gene expression aspects of human alcohol-associated steatohepatitis.

Keywords: Steatohepatitis, fibrosis, liver inflammation, HNF4α, gender differences

Alcohol is a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide (Gao and Bataller, 2011, Orman et al., 2013, Pang et al., 2015) and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is the major cause of alcohol-related mortality (Rehm and Shield, 2019). ALD typically encompasses a spectrum of pathologies ranging from steatosis to steatohepatitis with or without progressive fibrosis and this fibrotic component ultimately leads to cirrhosis. In some individuals, a severe form of acute on chronic liver failure, acute alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), can occur at various stages along this progression, but in the majority of individuals who die from ALD, progression to cirrhosis occurs in the absence of an episode of acute AH (Joshi-Barve et al., 2015, Pang et al., 2015, Farooq and Bataller, 2016). Alcohol interacts with other causes of liver disease, including hepatitis B and C, and metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity increase the risk for development of cirrhosis and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (Pang et al., 2015, Joshi et al., 2016, Farooq and Bataller, 2016). The specific mechanisms responsible for ALD development and progression are not fully understood.

Animal models of ALD are critical tools to increase mechanistic understanding of the disease. Mice are the most important animal model due to the ease with which they can be handled and the availability of genetic alterations. Nonetheless, the available mouse models of ALD have major limitations. In the most commonly used model, Lieber-DeCarli feeding (Guo et al., 2018, Lieber and DeCarli, 1986, Lieber and DeCarli, 1989), mice consume a liquid diet high in fat (36% of calories from corn oil) with a similar proportion of calories derived from ethanol. Typically, mice consume on average about 18 (female) to 20 (male) grams of alcohol per kg mouse weight per day and feeding durations range anywhere from a few days to 8 weeks. This diet reliably produces hepatic steatosis and modest inflammation, but it does not typically result in fibrosis, its results are variable, and attempts to keep mice on this diet for prolonged periods result in significant mortality due to non-hepatic causes. Lieber-DeCarli feeding is labor intensive in that it requires daily feeding bottle changes throughout the feeding period. Various methods to enhance liver injury from the Lieber-DeCarli diet have been developed including adding one or more acute alcohol bolus gavages (Bertola et al., 2013a), pre-treating the animals with a high fat diet prior to alcohol gavage (Chang et al., 2015) or injecting intraperitoneal LPS (Gao et al., 2017). These models have been successful at inducing hepatic inflammation, but do not reproduce acute AH or mimic the slow progression of fibrosis characteristic of human alcohol-associated steatohepatitis (ASH). They also suffer from mortality that is typically about 10% but can be as high as 50% in some cases (Gao et al., 2017).

A more invasive model of ALD was initially developed by Tsukamoto and French who pioneered a chronic alcohol intragastric administration model in rats (Tsukamoto et al., 1990) that was later modified for mice by Thurman and colleagues (Kono et al., 2000) and further refined by Tsukamoto and colleagues (Ueno et al., 2012). As it has evolved, this model introduced the simultaneous ad libitum administration of a high fat diet along with continuous intragastric alcohol feeding that was punctuated with intermittent high dose alcohol boluses (Lazaro et al., 2015). Depending on the administration protocol and duration, this model produces inflammation, steatohepatitis and progressive fibrosis, and a more aggressive bolus regimen can produce a disease phenotype very similar to acute AH with prominent pyroptosis-dependent hepatocellular death (Khanova et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the technical demands of keeping mice alive and performing this feeding are substantial and this has limited the availability of the model to a single center in Los Angeles. Nonetheless, the success of the Tsukamoto model clearly shows that mice are able to develop pathology similar to human ALD and that this requires consistent alcohol administration over a long period of time with simultaneous consumption of a high fat diet.

The aim of this study was to develop a long-term alcohol feeding model that required minimal, if any, daily intervention, had minimal or no mortality, and produced an inflammatory and fibrotic phenotype similar to human ASH. As is commonly used for studies of neurological alcohol adaptation and alcohol drinking preference (Thiele and Navarro, 2014), we added alcohol to the drinking water. While C57BL/6 mice readily drink alcohol supplemented water (Yoneyama et al., 2008, Belknap et al., 1993), liver injury was previously not observed with this alone. We thus added a component of high fat diet via a high fat chow pellets. Similar to previous observations (Hwa et al., 2011), we observed that sustained maximal alcohol intake was best achieved when the drinking water alcohol concentration cycled between 10 and 20%. Mice tolerated this diet well and after about 16 weeks we observed a liver histological picture of steatosis, inflammation and peri-cellular fibrosis that resembled slowly progressive human ASH without acute AH.

Experimental Procedures

Mice and feeding procedures

6–7 week old C57BL6/J mice were purchased from Jackson labs. All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled, specific pathogen-free environment with 12-hour light-dark cycles. All animal handling procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center (Kansas City, KS). Both male and female mice were fed ad libitum Western diet (WD, Research Diets, Inc. Cat. No. D12079B, 40% calories from fat (90% milk fat, 10% corn oil), 0.2% cholesterol) and alcohol was given ad libitum in the sole source of drinking water at indicated concentrations. Mice in alcohol groups received progressively increasing amount of alcohol in water (1%, 3%, 10%, 15% and 20% v/v for 3 days each). We did not add sugar to the water. Mice in the 10% alcohol group stayed on 10% v/v alcohol for 16 weeks. Mice in the 20/10% group had alcohol concentration progressively increased as indicated, but after reaching 20% v/v they were then alternated between 20% v/v (4 days, Thursday through Sunday) and 10% v/v (3 days, Monday through Wednesday). Mice were caged in groups of 2–5 mice per cage but for individual experiments all mice were caged with the same number of animals per cage. Body mass, ethanol and water intake, were assessed twice a week and average liquid consumption was calculated from volume loss in the feeding bottle.

Lieber-DeCarli liquid diet feeding was performed as previously described (Guo et al., 2018). Mice received control or alcohol liquid diet (6.4% alcohol, v/v) for 3 weeks.

Aged matched control/chow mice were fed standard chow diet (10% fat).

For serial blood draws from live animals, blood was drawn from the retroorbital vein. Serum was collected and analyzed for ALT and AST activity with commercial kits. Blood alcohol was measured by EnzyChrom™ Ethanol Assay Kit (VWR, Cat # 75878–060).

Antibodies

Primary antibodies:

Anti- HNF4α antibodies were from Novus. Anti-F4/80 antibodies were from Abcam. Anti-β-actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz.

Secondary antibodies:

IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 680RD goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Li-COR. General HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, AL).

Real Time PCR

RNA was extracted from cultured cells or tissues using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using the RNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Cat.No 4368814). Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed in a CFX96 Real time system (Bio-Rad) using specific sense and antisense primers combined with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) for 40 amplification cycles: 5 s at 95 °C, 10 s at 57 °C, 30 s at 72 °C.

Primers were as follows: Gapdh, cgtcccgtagacaaaatggt, ttgaggtcaatgaaggggtc; Tnf, aggctctggagaacagcacat, tggcttctcttcctgcaccaaa; Il6, ttccatccagttgccttctt, cagaattgccattgcacaac; Mmp7, ggcttcgcaaggagagatca, gccaaattcatgggtggcag; Hnf4a, ggtcaagctacgaggacagca, atctgctgggacagaacctct; Hnf4a_p2, cttggtcatggtcagtgtgaac, aggctgttggatgaattgaggtt; Ccl2, acctggatcggaaccaaatgag, gctgaagaccttagggcagat; Ppargc1a, tgttcgcaggctcattgttg, ggtggattgaagtggtgtagc; Srebf1, tgtgcacttcgtagggtcag, gccatcgactacatccgctt; Col1a1, tggccaagaagacatccctg, gggtttccacgtctcaccat.

Western Blots

Protein extracts (15 µg) were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Hybond ECL, GE Healthcare), and blocked in 3% BSA/PBS at RT for 1 hour. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at manufacturer recommended concentrations. Immunoblots were detected with the ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) or using near-infrared fluorescence with the ODYSSEY Fc, Dual-Mode Imaging system (Li-COR).

Histological Analysis

Liver tissue sections (5 μm thick) were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples. For analysis of histological features, H&E and Masson trichrome stained sections were examined by an experienced liver pathologist (M.O.) in a blinded manner. Immunostaining on formalin-fixed sections was performed by deparaffinization and rehydration followed by antigen retrieval by heating in a pressure cooker (121°C) for 5 minutes in 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0 as described previously (Zhao et al., 2018). Peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes. Sections were rinsed three times in PBS/PBS-T (0.1% Tween-20) and incubated in Dako Protein Block (Dako) at room temperature for 1 hour. After removal of blocking solution, slides were placed into a humidified chamber and incubated overnight with an antibody, diluted 1:300 in Dako Protein Block at 4°C. Antigen was detected using the SignalStain Boost IHC detection reagent (catalogue # 8114; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), developed with diaminobenzidene (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich), and mounted. Signal intensity was analyzed by Aperio ImageScope 12.1.

TMT labeling and Mass spectrometric analysis

Whole liver extracts were lysed in 20mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1% SDS. Trypsin digestion and TMT labeling was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions using the TMT-sixplexMass tagging kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Briefly, 100 μg of protein per condition were digested with 2.5µg of trypsin (Promega). After trypsin digestion, TMT label reagent was added. Equal amounts of labeled samples were combined, sample was then loaded into a high pH reverse phase spin column previously conditioned following the manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher Scientific). The peptides were eluted in nine fractions. Eluted samples were injected into the HPLC coupled with the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). For data analysis all MSMS scans were searched using Protein Discoverer v.2.4 running Sequest HT and a mouse database downloaded from the NCBI NR repository. Protein quantification was done utilizing unique peptides only.

Immune Cell isolation and expression analysis

Immune cells were isolated by a modification of the method described by Troutman et al. (Troutman et al., 2021). Mouse livers were digested by retrograde perfusion with liberase via the inferior vena cava as previously described (Li et al., 2018). The dissociated cell mixture was placed into a 50 mL conical tube and centrifuged twice at 50 g for 2 min to pellet hepatocytes. The supernatant from the second 50 g spin contained the non-parenchymal cells and was subsequently spun at 300 g for 10 min. The cell pellet was gently resuspended in 20% Percoll solution (Sigma) and spun at 600 g for 15 min. The Percoll pellet was resuspended in 17% Optiprep solution (Sigma), about 5 mL of 10% FBS/2 mM EDTA/1X PBS was carefully overlayed on top, and it was then centrifuged at 1400 g for 15 min with minimum acceleration and no brake. After centrifugation, the non-parenchymal cells containing the immune cell component formed a thick white interface and was transferred into a new 50 mL conical tube. The mixture was diluted with 10% FBS/2 mM EDTA/1X PBS to 25 mL and then centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min.

The cells were further purified by FACS sorting. The pellet was incubated with purified anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) to minimize nonspecific antibody binding and subsequently stained with anti-CD45 (BioLegend, Catalog number 103116. Cells were analyzed on a BD LSR II cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). For flow cytometric analysis, DAPI+ cells were gated to exclude dead cells and CD45+ cells were gated to exclude endothelial cells, stellate cells, and residual hepatocytes. CD45+DAPI− cells were sorted using a BD FACSAria IIIu Cell Sorter (BD Bioscience). Sorted cells were immediately used to generate barcoded cDNA libraries using a 10x Genomics Chromium platform with a total input of 10,000 cells per condition. Libraries were sequenced with an Illumina Novoseq sequencer and data analyzed with the 10x Genomics Cell Ranger and Loupe Cell Browser software. Expression analysis identified 5 major immune cell clusters corresponding to macrophages, T-cells, B-cells, granulocytes, and NK cells.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. The Student t test, paired t test, Pearson’s correlation, or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used for statistical analyses. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Optimization of alcohol consumption in the alcohol/water high-fat diet in mice.

Extensive prior studies suggest that both high fat consumption and relatively high chronic alcohol exposure, such as from intragastric infusions, are required to produce liver pathology that resembles human ALD (Ueno et al., 2012, Ghosh Dastidar et al., 2018), but approaches to achieve these goals are limited by technical difficulties of the methods. To develop a technically simple dietary protocol that would reproduce aspects of human ALD, we fed mice a pelleted “western diet” (WD) with a composition of 40% calories from fat (90% milk fat, 10% corn oil), 0.2% cholesterol) in combination with alcohol provided in the drinking water. This diet was not supplemented with fructose or additional cholesterol, as is typically used for NASH models, and thus was not expected to produce liver injury without the addition of alcohol. We used the C57B6/J mouse strain since this is known for preference for alcohol in water consumption (Belknap et al., 1993, Yoneyama et al., 2008). Control mice received plain water with ad libitum WD. Our protocol was to keep the mice on this diet for 16 weeks. Initially we tested constant alcohol concentrations of either 10% or 20% in water in both males and females (Figure 1A). We found that in both male and female mice, fluid intake in the 10% alcohol group was increased compared to water alone. However, in the 20% group, male mice drank significantly lower amounts resulting in net alcohol intake comparable to the 10% group (Figure 1A). This agrees with previously published data on C57BL/6 mice. After reaching a certain concentration of alcohol in water, these mice consumed a similar amount of alcohol regardless of alcohol concentration, with a maximum for males of 10–14 g/kg/day and females of about 12–18 g/kg/day (Belknap et al., 1993, Blednov et al., 2005). In our protocol, both males and females drank more alcohol, 18–20 g/kg/day for males and over 20 g/kg/day for females. Female mice did not show a significant self-titration effect and drank more alcohol at the higher concentration.

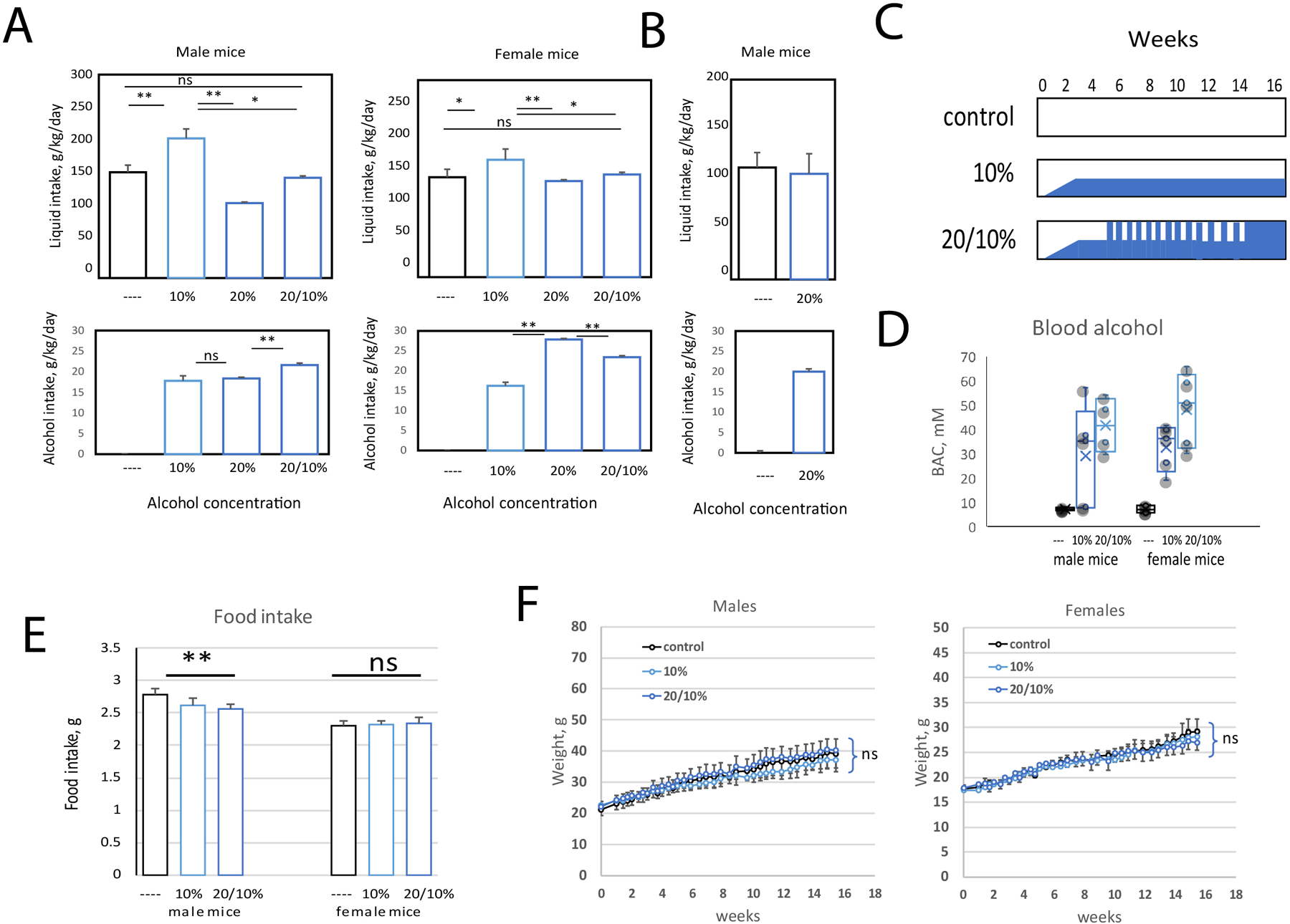

Figure 1. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding model.

A-F. Male and female C57BL6/J mice were fed ad libitum western diet and either given plain water or alcohol in water at indicated concentrations. A. Liquid intake and average alcohol intake of mice during the first 4 weeks of feeding. B. Liquid intake and average alcohol intake of mice during the last 2 weeks of feeding. C. Feeding scheme. Mice were slowly adapted to alcohol in water during the first 2 weeks of feeding (1%, 3%, 10% v/v at equal intervals). The 20/10% group received 20% v/v alcohol 4 days per week (Thursday-Monday) and 10% v/v alcohol 3 days per week (Monday-Thursday). This group had access only to 20% v/v alcohol during the last 2 weeks of feeding. D. Blood alcohol concentration in mice from 6 groups at 12 weeks after the start of the feeding. E. Average food intake in these mice. F. Weight gain during 16 weeks of feeding in male and female mice. Both male and female groups had N=11 (control), N=5 (10%) and N=11 (20/10%) mice per group.

Previous reports indicated that intermittent alcohol access could increase total alcohol consumption in some mouse strains (Hwa et al., 2011, Crabbe et al., 2012). We thus tested whether alternating 10% and 20% alcohol concentration could achieve higher total alcohol intake in mice fed WD. We gave mice 20% alcohol over the weekends (Thursday-Sunday) and 10% alcohol during the week (Monday-Wednesday). We found that alternating the alcohol concentration in this way increased fluid and total alcohol intake in males (Figure 1A). Interestingly, female mice drank similar amounts of fluid regardless of alcohol concentration suggesting that they did not reach maximum alcohol intake at 20% feeding (Figure 1A). We also found that after being on the alternating alcohol concentration protocol for several weeks, male mice then tolerated constant 20% alcohol without a decrease in fluid consumption. Thus, we kept both male and female mice at the alternating alcohol concentration for 14 weeks and changed to constant 20% only for the last 2 weeks of the experimental protocol. During this last 2-week period, the mice consumed similar volumes of 20% alcohol in water as water alone (Figure 1B). A feeding scheme for the three groups of mice is presented in Figure 1C. We noted that both male and female mice that received the 20/10% alcohol protocol reached higher blood alcohol concentrations compared to 10% only groups (Figure 1D).

Male mice that received the 20/10% alcohol protocol consumed a little less western diet pellets (2.6 g/day vs 2.8g/day for the no alcohol control), while female mice showed no significant difference in food intake between groups (Figure 1E). All three groups of mice had similar weight gain (Figure 1F) over the 16-week protocol. All the mice looked healthy throughout the 16-week feeding protocol, and unlike the situation with Lieber-DeCarli diet, we observed extremely low mortality in this model with only one death out of 82 mice completing 16 weeks. This death occurred early in the feeding period and may not have been related to the diet.

The WDA model promotes a liver disease phenotype in mice.

Next, we assessed liver pathology in these mice (Figure 2). By gross appearance, all WD control mouse livers appeared normal, while the WDA (Western Diet with alcohol) livers were enlarged and about 15% of the 20/10% livers showed nodularity and irregularity of the liver contour. Mice showing liver nodularity also had enlarged spleens (Figure 2A). All of the WDA mice had an increase in liver/body weight ratios compared to WD alone controls with mice in 20/10% groups having the biggest increase and mice in the 10% group having an intermediate phenotype (Figure 2B).

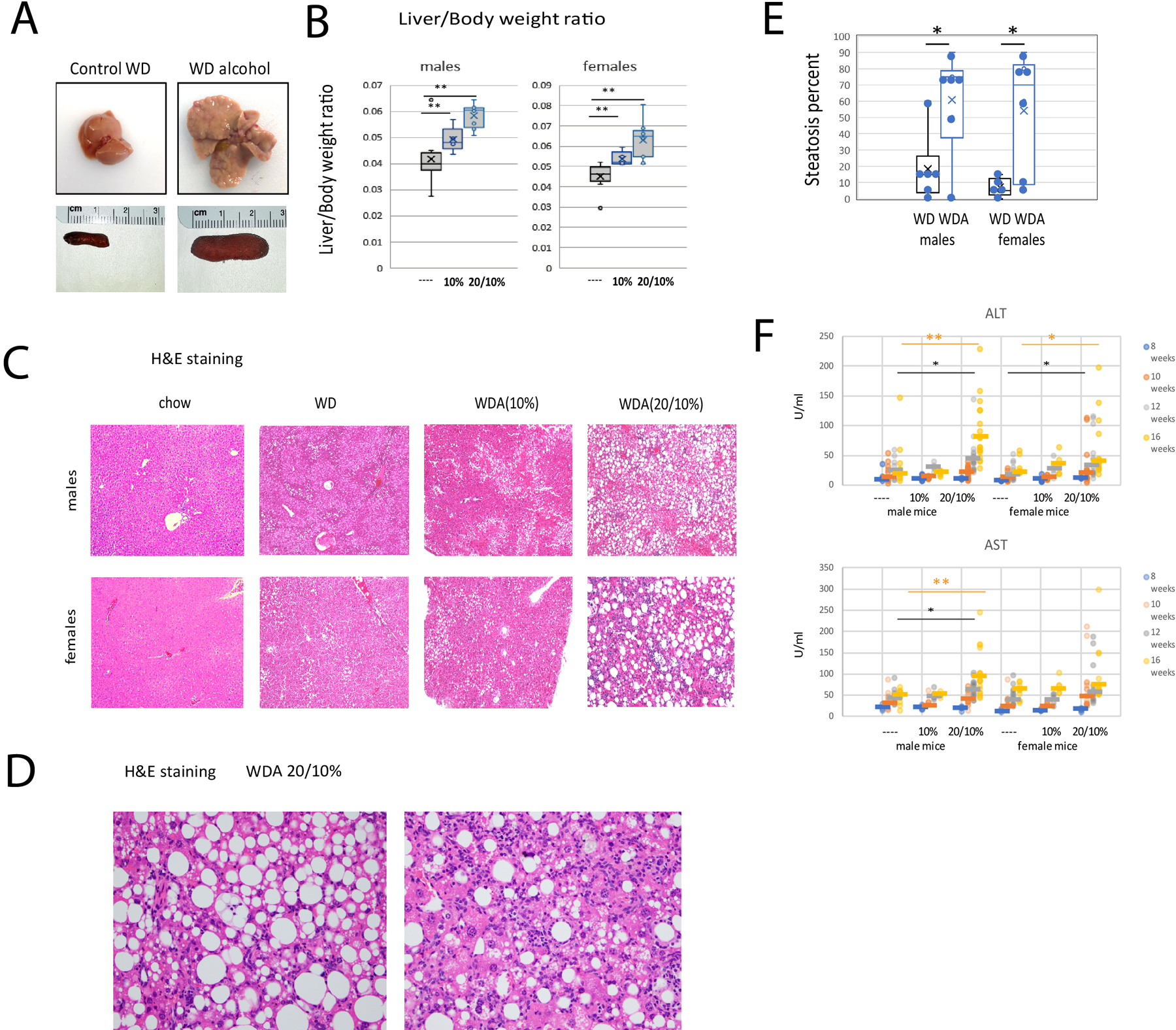

Figure 2. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding produces a liver injury phenotype in male and female mice.

A. Examples of livers from control and alcohol (20/10%) groups and corresponding spleens. B. Liver/body weight ratios of these mice. Both male and female groups had N=11 (control), N=5 (10%) and N=11 (20/10%) mice per group. **, P < 0.01. C. Representative images of H&E staining from 6 groups. D. Images showing features of ALD in the liver. E. Steatosis percentage for male and female mice on the WD and 20/10% WDA diet. F. Serum ALT and AST levels in these mice at indicated time points. **, P < 0.01, *, P < 0.05.

H&E staining of the livers (Figure 2C–E) showed that WD alone resulted in a mild degree of hepatic steatosis in more than 80% of the mice fed WD compared to chow control (Figure 2C). The average percentage of steatotic hepatocytes in the WD only group was less than 10% in females and less than 20% in males (Figure 2E). None of the WD livers showed inflammation or fibrosis. In the WDA diet fed mice (20/10% alcohol), severe steatosis involving 70–90% of hepatocytes was present in both male and female livers (Fig. 2C–E). In both males and females, steatohepatitis marked by hepatocyte ballooning and inflammation was present in about half of the mice.

We measured serum ALT and AST levels in these mice at 8, 10 12 and 16 weeks of feeding. At 8 weeks, AST and ALT were normal in all mice but ALT was elevated in both male and female mice in the 20/10% group at 16 weeks. Males did not develop elevated ALT until 16 weeks but some female mice showed elevated ALT as early as 10 weeks of feeding (Figure 2F).

The WDA model causes dramatic changes in liver proteome.

To further analyze changes induced by alcohol in the WDA model we performed TMT-mass spectrometry analysis to quantify changes in liver proteome in response to alcohol (Figure 3A, B). We used N=3 male mice per group either fed control WD only or WD in combination with 20/10% alcohol. In contrast to similar measurements in LieberDeCarli feeding (Schonfeld et al., 2021), we observed a large number of changes in protein abundance (331 differentially regulated proteins in the WDA model vs 52 proteins in the LieberDeCarli model). Among the top differentially regulated proteins we found that multiple proteins involved in fatty acid metabolism were upregulated and several cytochromes P450s involved in linoleic acid and arachidonic acid metabolic pathways were downregulated (Figure 3C).

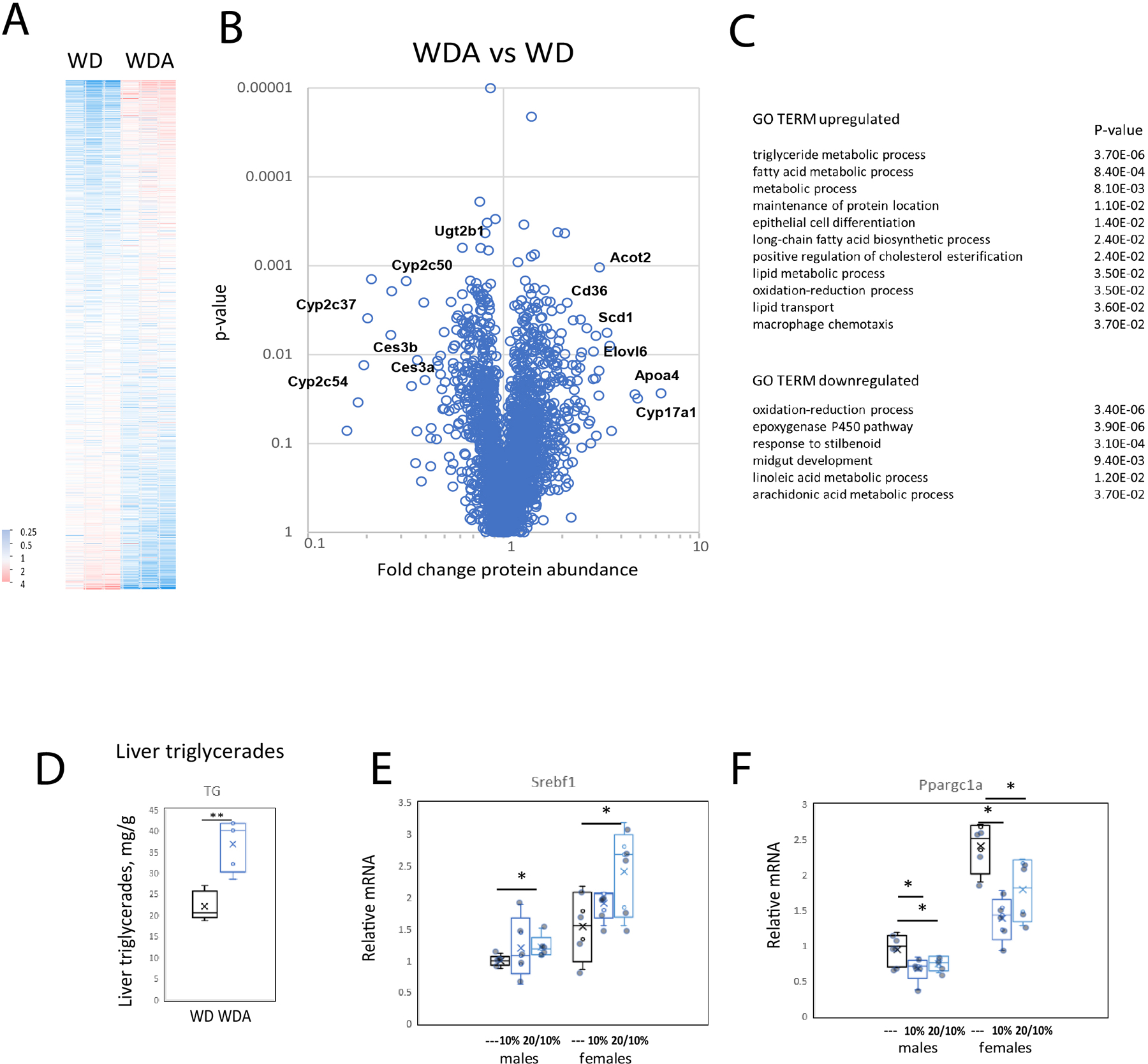

Figure 3. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding results in liver fat accumulation.

A-C. Whole liver extracts were analyzed by TMT mass spectrometry. N=3 mice per group. Relative abundance of proteins (A) fold change by alcohol (B) and GO TERM enrichment (C) in WD control and WD alcohol mouse livers. D. Liver triglycerides in livers of male mice in control (water) and alcohol (20/10%) groups. N=5. **, P < 0.01. E-F. Relative liver mRNA in these mice. N=5. *, P < 0.05.

We confirmed the increase in fat accumulation in the liver by measuring liver triglycerides in control and alcohol fed mice. Liver triglycerides were almost twice as high in the WDA 20/10% group as compared to the WD control group (Figure 3D). These data correlated with increased expression of SREBP1 (Figure 3E) and decreased PGC-1α expression in alcohol fed mice (Figure 3F).

The Western diet alcohol model promotes liver fibrosis.

To evaluate fibrosis in these mice we performed Sirius Red staining of livers (Figure 4A). We found that WD mice showed no increase in Sirius Red staining while both male and female WDA mice had an increase in Sirius Red staining (Figure 4B) in the 20/10% group and this showed a pronounced zone 3 pericellular pattern (Figure 4A). We performed Masson trichome stains on a subset of the livers as well (Figure 4C). About half of the female WDA mice showed pericellular fibrosis (Brunt stage 1a) while abnormal fibrosis was not detected by trichome in males. These findings correlated with upregulation of TGFβ and Col1a1 mRNA in livers of alcohol fed mice (Figure 4D, E).

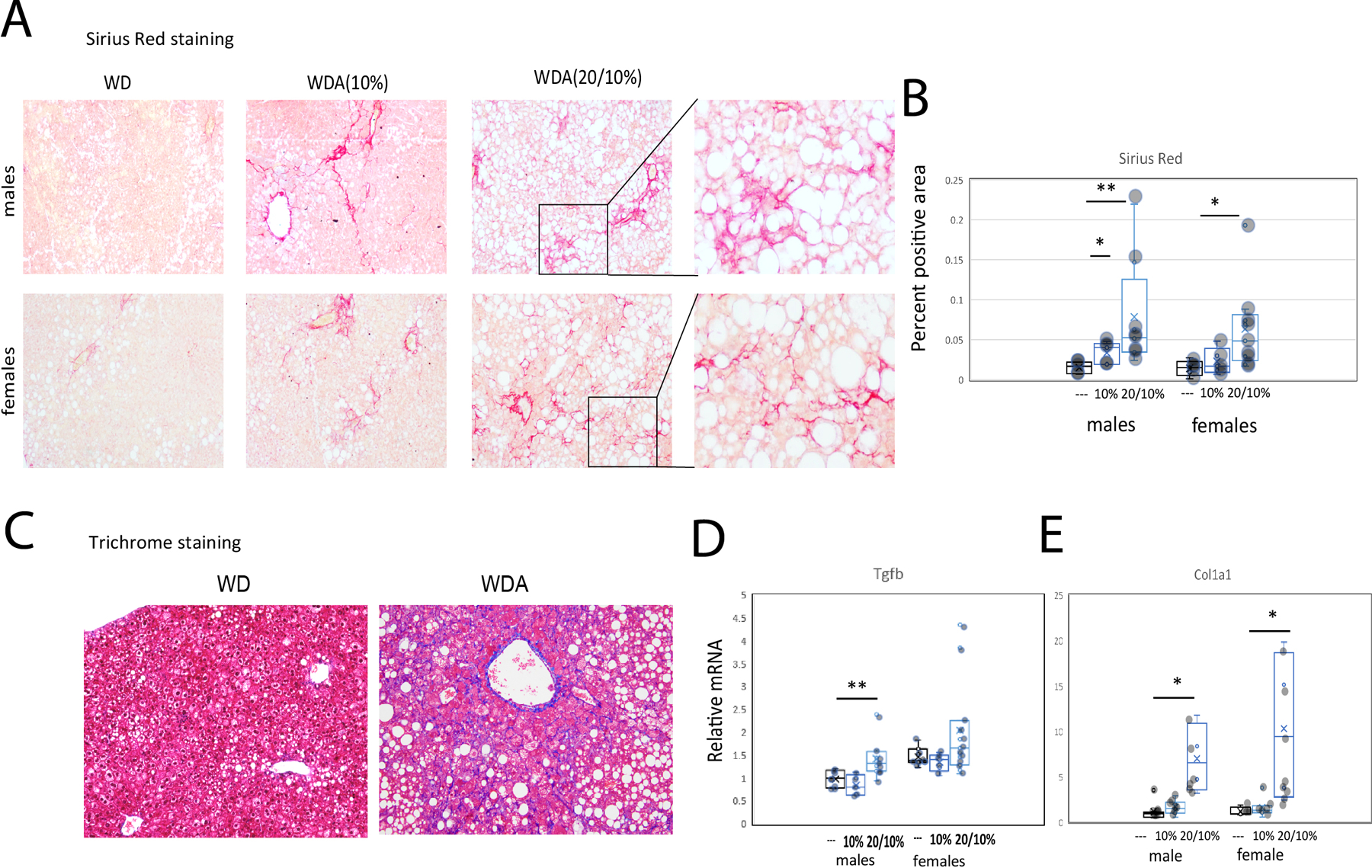

Figure 4. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding results in liver fibrosis.

A. Representative images of Sirius Red staining of liver sections from 6 groups. B. Sirius Red positive area. Both male and female groups had N=5 (---, water), N=5 (10%) and N=8 (20/10%). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. C. Trichrome staining of liver sections in control (water, WD) and alcohol (20/10% alcohol, WDA) groups. D-E. Relative liver mRNA in these mice. N=5 (---, water), N=5 (10%) and N=8 (20/10%). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

The WDA model alters the immune environment in the liver.

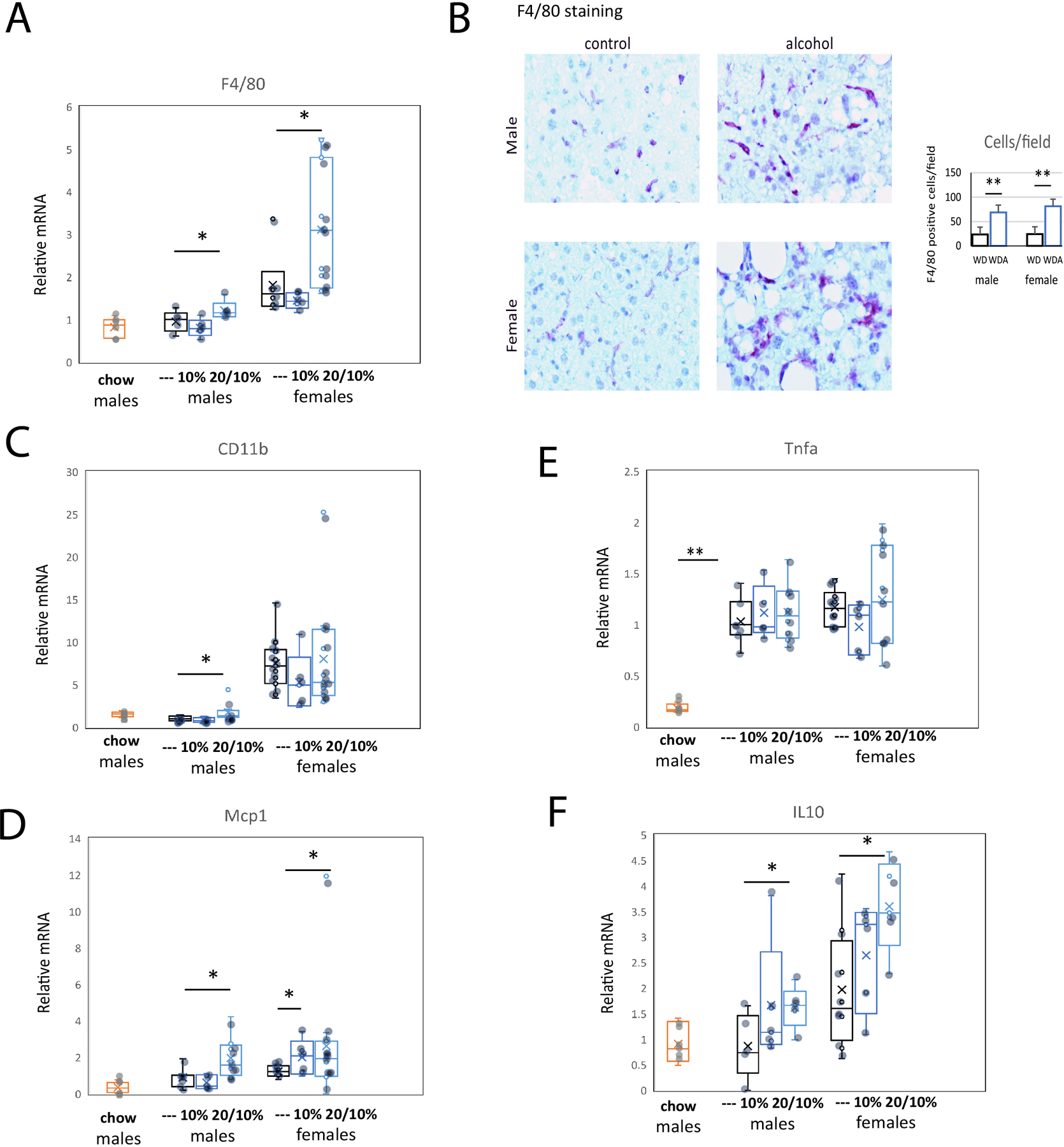

Next, we assessed the immune phenotype of control and alcohol fed mouse livers (Figure 5). We found that in male mice, the 20/10% alcohol group showed elevated levels of F4/80, CD11b, and MCP-1/Ccl2 mRNA (Figs. 5A,C,D). Immunohistochemistry in liver sections confirmed increased numbers of F4/80 positive cells in both males and females (Fig. 5B). Female mice in the 20/10% group similarly showed elevated levels of F4/80 mRNA and protein level (Figure 5A, B), as well as MCP-1/Ccl2 mRNA (Figure 5D). We did not observe any significant differences in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in these in WDA as compared to WD livers, for example TNFα mRNA is shown in Figure 5E. This could be due to the fact that WD alone resulted in elevated TNFα mRNA levels in the liver and alcohol exposure did not have additional effect (Figure 5E). In addition, we found that the both male and female WDA groups showed significant upregulation of IL-10 mRNA (Figure 5F).

Figure 5. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding results in liver immune cell accumulation and changes in the immune environment.

A. Relative liver mRNA in mice from 6 groups. N=6 (chow), N=5 (---, water), N=5 (10%) and N=8 (20/10%). *, P < 0.05. B. Representative images of F4/80 staining of liver sections in control (water) and alcohol (20/10%) groups. Right. Average number of F4/80 positive cells per high power field. N=5 per group. **, P < 0.01. C-F. Relative liver mRNA in mice from 6 groups. Corresponding mRNA levels in chow fed, age matched controls are indicated. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

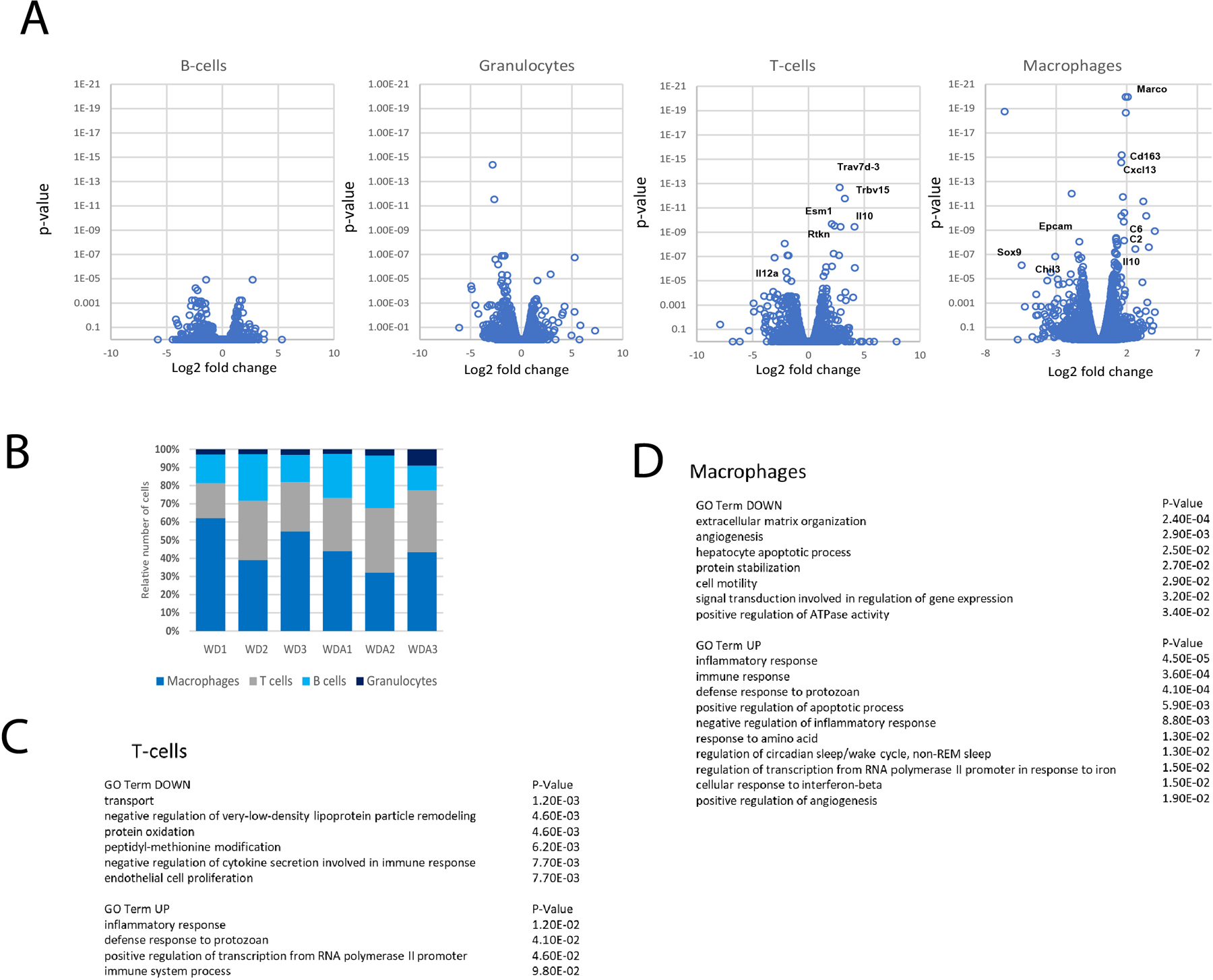

To further analyze the changes in immune cells we performed RNA-Seq analysis of CD45 positive cells isolated from WD and WDA livers and separately examined mRNA expression in macrophages, T-cells, B-cells and granulocytes (Figure 6). We found that alcohol caused multiple genes to be differentially regulated, particularly in T-cells and macrophages (Figure 6A–B). We analyzed the corresponding GO term enrichment in both T-cells (Fig. 6C) and macrophages (Fig. 6D). Among top up- and downregulated genes we found an enrichment of genes involved in extracellular matrix organization, angiogenesis, and apoptosis. Our data suggest that alcohol promotes changes in macrophages and T-cells that contribute to alcohol induced liver injury and fibrosis.

Figure 6. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding results in changes in the immune cell gene expression.

A-C. CD45 positive cells were isolated from control and alcohol (20/10% group) fed mouse livers (n=3 mice per group) and subjected to single cell RNA-seq analysis (3 mice per group). A. Volcano plot of differentially regulated genes in B-cells, T-cells, Granulocytes and Macrophages. B. Ratio of cell numbers for individual cell population. C-D. GO TERM enrichment in top upregulated and downregulated genes.

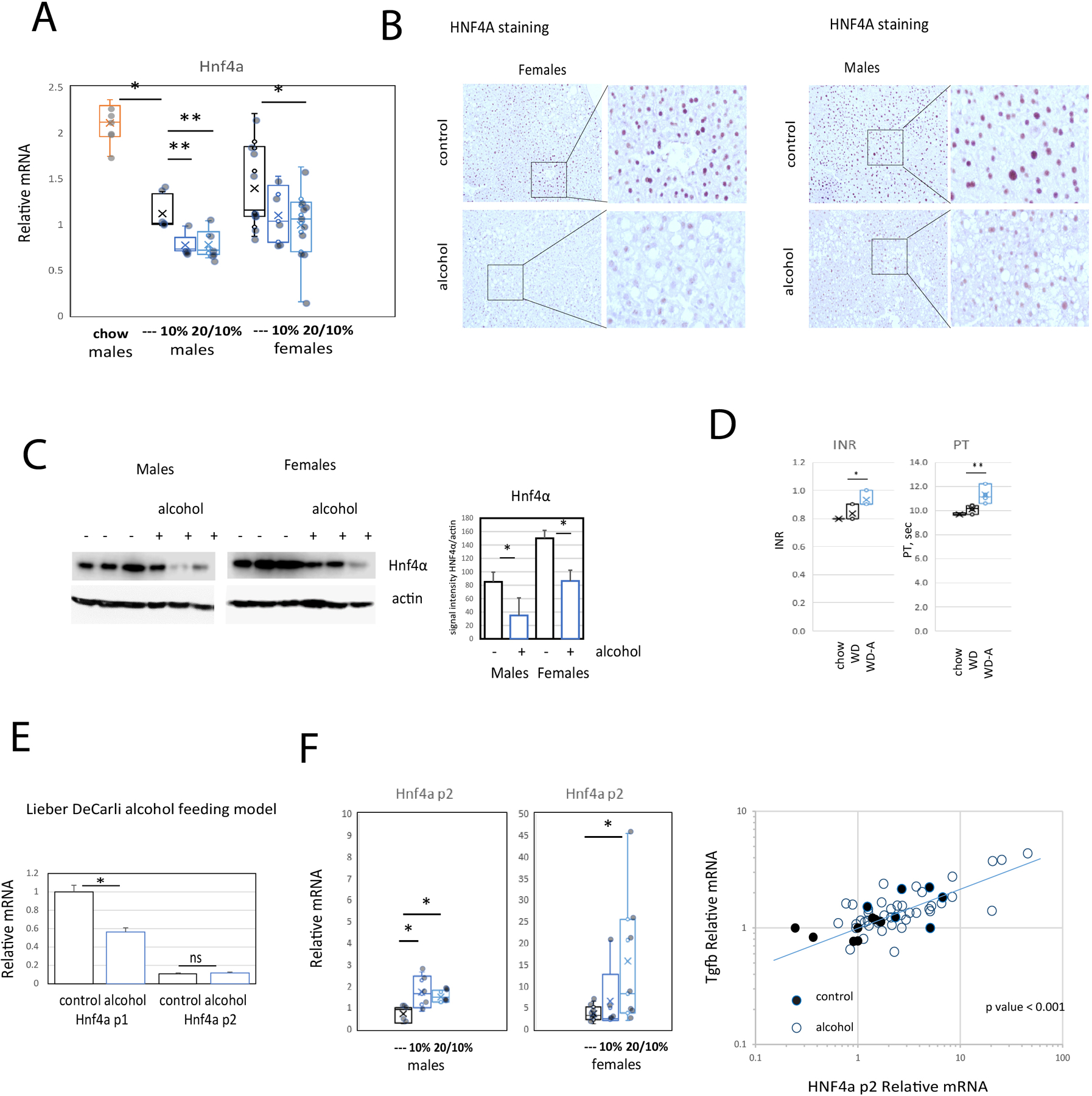

The WDA model promotes HNF4α downregulation.

The alcohol effect on protein expression as seen in the proteomic data (Figure 3) was notable for downregulated CYP2C37, CYP2C54, CYP2C50, CES3A, and CES3B. All of these are well documented targets of HNF4α (Walesky et al., 2013, Huck et al., 2019), suggesting that the function of this liver specific transcription factor was decreased by alcohol. This conclusion was further supported by the upregulation of expression of ACOT2 and CYP17A1, both proteins whose expression is suppressed by HNF4α. Since HNF4A downregulation is a known driver of hepatocellular failure in alcoholic hepatitis patients (Argemi et al., 2019), these observations raised the question of whether alcohol downregulates HNF4Α in this WDA model. To assess the effect of the alcohol and western diet combination on HNF4α expression, we measured Hnf4a mRNA and protein levels in livers of mice fed western diet alone or in combination with alcohol in water administration (Figure 7). We found that, as reported previously (Qin et al., 2020), western diet feeding reduced liver abundance of Hnf4a about 2-fold. Addition of alcohol in water further reduced Hnf4a mRNA levels (Figure 7A). We observed significant reduction of HNF4α protein levels using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 7B) or western blot analysis in both male and female mice (Figure 7C). As HNF4α expression is important for maintaining hepatocellular differentiated function we assessed PT/INR in plasma samples from chow-fed, WD, and WDA mice. There was a small but significant increase in PT/INR after 16 weeks of WDA feeding (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Alcohol in water in combination with western diet feeding results in HNF4α dysregulation.

A. Relative liver mRNA in mice from 6 groups. N=6 (chow), N=5 (---, water), N=5 (10%) and N=8 (20/10%). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01. B. Representative images of HNF4α protein staining in liver sections in control (water) and alcohol (20/10%) groups. C. Western blot analysis of HNF4α protein levels in liver extracts from control (water) and alcohol (20/10%) fed mice. Right. Densitometry analysis of HNF4α protein expression. N=3 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. D. INR and Prothrombin time of mice from chow fed (chow), WD fed (western diet + water) and WDA fed (western diet + 20/10% alcohol) mice. N≥4. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01.E. Relative liver mRNA in mice fed Lieber-DeCarli alcohol or control liquid diet for 4 weeks. F. Relative liver mRNA in mice from 6 groups as in Figure 1. N=5 (---, water), N=5 (10%) and N=8 (20/10%). *, P < 0.05. Right. Correlation between Hnf4a p2 mRNA and Tgfb1 mRNA in mice fed western diet with (○) or without (●) alcohol. r=0.75, N=64 mice, P < 0.00001.

The WDA model promotes upregulation of HNF4α isoforms transcribed from the p2 promoter.

Alcohol-associated liver disease in patients is often associated not only with HNF4A downregulation but also with upregulation of a distinct HNF4A isoform expressed from a different promoter called the P2 promoter (Argemi et al., 2019). Together this results in defective metabolic and synthetic functions. TGFβ1 is a key upstream transcriptome regulator that induces the use of the HNF4α P2 promoter in hepatocytes.

We directly compared changes in HNF4A promoter expression in the WDA model with that seen in a 3-week 6.4% Lieber-DeCarli mouse feeding. Lieber DeCarli feeding resulted in a decrease in Hnf4a expression with no elevation in p2 isoforms expression (Figure 7E). In addition to its reduction in mRNA from the Hnf4a P1 promoter (Figure 7A) and in contrast to the situation with Lieber-DeCarli diet, the WDA feeding protocol increased Hnf4a P2 expression (Figure 7F). In addition, we found strong correlation between Tgfb1 expression and Hnf4a P2 expression in these mice (r = 0.75, P < 0.0001, Figure 7F). This indicates that the WDA model more closely mimics some of the hepatocellular gene expression changes seen in human ALD. Unlike the Lieber-DeCarli diet, it reproduces the increase in Hnf4a P2 promotor expression that occurs in human ALD.

Discussion

Human alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) represents a diverse spectrum of pathologies encompassing steatosis, hepatocellular injury, immune cell infiltration, fibrosis and loss of liver function. It is thus clear that no one animal model will display the full range of pathology present in human disease and all models have their limitations (Gao et al., 2017, Ghosh Dastidar et al., 2018). There is, however, a need for models that reproduce the disease process most responsible for ALD mortality, a low grade steatohepatitis with progressive fibrosis that slowly and asymptomatically leads to cirrhosis, portal hypertension and hepatic failure (Seitz et al., 2018). Current models such as the Lieber-DeCarli diet (Guo et al., 2018), Lieber-DeCarli diet with one or multiple alcohol gavages (Bertola et al., 2013b, Gao et al., 2017), an all liquid “WASH” diet with high fructose, high cholesterol and high trans-fat content (Sengupta et al., 2021), intragastric alcohol infusion (Tsukamoto et al., 2008), or intragastric infusion with high fat diet and one or more alcohol boluses (Khanova et al., 2018, Lazaro et al., 2015) can reproduce different aspects of human ALD, but all these models have the limitation of being labor intensive due to long duration and need for daily or more frequent manipulation. They also produce significant mortality which can result from non-hepatic causes leading to weight loss and reduced intake, complications of the gavages, or complications of intragastic feeding. Mortality in long-term feeding experiments is typically at least 10% and can approach 50% for some protocols (Gao et al., 2017). The Lieber-DeCarli diet is easier to perform, but it only reproduces a limited spectrum of human ALD features and the WASH diet represents a combination of pathological entities as the diet without alcohol produces liver injury as well. These require daily bottle changes and depending on the number and duration of mice fed can require considerable manpower. Intragastric feeding produces results more representative of ALD, but the extreme technical requirements for doing this successfully have prevented nearly all alcohol research labs from performing it themselves.

The aim of this study was to develop an easy to perform mouse model that showed the characteristics of alcohol-induced steatohepatitis with progressive fibrosis. We chose to introduce alcohol via the drinking water for its ease of administration and because of the extensive literature defining the factors that promote higher voluntary alcohol consumption via this route (Hwa et al., 2011). Consumption of alcohol in water by itself, however, is not sufficient to produce liver disease in mice (Gäbele et al., 2011, Song et al., 2002). Ethanol with low fat diet (5% of the calories) does not produce fatty liver unless a high blood-alcohol level is achieved by the intragastric infusion model (Tsukamoto et al., 1985, Tsukamoto et al., 2008, Ueno et al., 2012). We thus chose to combine alcohol supplemented drinking water with a high fat diet as this has been shown to enhance liver injury by both Lieber-DeCarli (Chang et al., 2015) and intragastric (Lazaro et al., 2015) alcohol administration. We specifically avoided adding fructose or cholesterol to the diet as these cause a NASH-like inflammatory liver disease (Farrell et al., 2019) and we wanted to study the situation where the inflammatory and fibrotic component was being driven by alcohol feeding.

The results demonstrate that 16 weeks of alternating 10% and 20% alcohol in water along with high fat chow produces an inflammatory and fibrotic phenotype similar to human ASH. The alternation of alcohol concentration increased tolerability and maintained alcohol consumption at high levels, particularly in males, and was able to achieve alcohol consumption of 18–20 g/kg/day (males) and 20–22 g/mouse/day (females) without any mortality. Mice on the WDA diet consumed a high percentage of fat (40%) in the chow, with 60% of that fat consisting of saturated FA, about 30% mono-unsaturated FA, and less than 10% PUFA. This chow formulation, without alcohol, produced weight gain and mild hepatic steatosis but did not produce a NASH-like syndrome and is different than the more typical NASH diets in that it does not have either cholesterol supplementation, high fructose, or trans-fats. The addition of alcohol in this model alcohol profoundly increased liver steatosis, produced mild liver inflammation, and induced an ASH-like zone 3 pericellular fibrosis. Thus, the inflammation and fibrosis in the WDA model is due to its alcohol component.

The inflammatory character of the WDA model is similar to human ASH. In males, ALT elevations do not develop until about 16 weeks while in females they occur earlier at about 12 weeks. Histologically, there were ballooned hepatocytes, a marked increase in tissue macrophages and the formation of crown-like macrophage structures in females that resemble those seen in steatohepatitis (Itoh et al., 2013). Gene expression analysis in both macrophages and T-cells predict increases in inflammatory responses and expression of scavenger receptors. In combination with the observed pericellular fibrosis, this model thus bears significant similarly to chronic ASH.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) is a nuclear hormone receptor that is constitutively active and regulates lipid, glucose, bile acid and drug metabolism in hepatocytes. Its expression is reduced in multiple examples of organ injury (Dubois et al., 2020). Loss of hepatic HNF4α causes fatty liver, hepatocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. HNF4α expression is markedly reduced in diabetes, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and high fat diet (HFD) feeding as well as models of alcohol-induced liver disease (Gonzalez, 2008, Lu, 2016, Argemi et al., 2019, Qin et al., 2020). We found that the WDA diet promotes HNF4α downregulation in mice. We observed similar downregulation in both male and in female mice. HNF4α downregulation was accompanied by upregulation of an HNF4α isoform transcribed from the fetal P2 promoter. This phenomenon has been observed in human disease but is not reproduced in the Lieber-DeCarli model (Figure 7A). In this respect, the WDA model more closely resembles human ALD. TGFβ1 is a key upstream regulator in alcohol associated liver disease that induces HNF4α P1 and P2 imbalance in ALD patients. This, in turn, results in defective metabolic and synthetic functions. We found a strong correlation between TGFβ1 and HNF4α p2 expression in the livers of our mice suggesting that this can be a suitable model to study TGFβ1 and HNF4α deregulation in ALD.

There are several advantages to this model over other models of ASH and alcohol-induced fibrosis. It requires no special expertise, no special equipment, is not labor intensive, and requires just a brief water bottle change twice a week. It reproduces a very slow and largely asymptomatic disease progression and although the feeding protocol takes months, the minimal monitoring these animals require makes this highly feasible. Lieber-DeCarli diet requires daily manipulation and alcohol gavages to produce fibrosis, has significant mortality and thus is more labor intensive. The WDA diet protocol described here produces zone 3 pericellular fibrosis and thus resembles ASH histologically. It also shows inflammatory changes in macrophages and T-cells, and granulocytes are present. It can be applied equally to both males and females and preserves gender differences in the disease phenotypes as seen in humans.

While the WDA model differs considerably from Lieber-DeCarli and Tsukamoto-French models of ALD, several prior studies have also examined the effects of alcohol in drinking water, combined with various diets on liver pathology. Several of these studies added alcohol to diets already known to produce a NASH-like liver injury and showed enhancement of both inflammation and fibrosis by the added alcohol (Sengupta et al., 2021, Benedé-Ubieto et al., 2021). Others added alcohol to various non-hepatotoxic high fat diets but either did not examine liver pathology or did not reach optimal dietary alcohol concentrations or exposure duration to achieve an ASH-like liver phenotype (Song et al., 2002, Gelineau et al., 2017, Gäbele et al., 2011, Coker et al., 2020).

A previous report by Gäbele et al (Gäbele et al., 2011) in Balb/c mice combined 5% alcohol in drinking water with a high fat diet. While they did not observe overt liver injury, they did show that gene expression patterns associated with fibrosis were synergistically activated by the combination. A very recent report by Benedé-Ubieto et al. (Benede-Ubieto et al., 221) also describes a dietary protocol where the combination of a NASH-inducing diet (high fat containing 25% transfat, high fructose, high cholesterol) and 10% alcohol administered in the drinking water for 10 or 23 weeks produced inflammation, oxidative stress and mild fibrosis. While fibrosis at 23 weeks was similar in the high fat diet with or without alcohol, at 10 weeks abnormal fibrosis was seen only in the high fat diet plus alcohol group. These results are similar to our findings although in the paper by Benedé-Ubieto et al, the NASH diet without alcohol also produced inflammation and fibrosis making it an optimal model to study the combination of both metabolic and alcohol-induced steatohepatitis. In our studies, the high fat diet without trans-fat or added fructose or cholesterol produced only steatosis in the absence of alcohol and required alcohol for significant pathology. We were able to increase alcohol consumption relative to that achieved by Benedé-Ubieto et al by alternating alcohol concentration between 10% and 20% and thus our model is more a model of ALD without a distinct non-alcohol NASH-like component. Nonetheless, all these studies clearly demonstrate that alcohol in drinking water is a viable method for alcohol delivery in the study of liver disease and the very low technical demands of this method allows long-term protocols that produce liver fibrosis to be highly feasible.

In summary, we have developed a simple, easy to perform method to achieve long-term exposure of mice to pathologically relevant amounts of alcohol. The model requires 16 weeks of alcohol exposure, but then displays many of the characteristics of chronic alcohol-associated steatohepatitis including steatosis, steatohepatitis, macrophage infiltration, progressive pericellular fibrosis and a reduction in HNF4α without overt liver failure. It complements previously described experimental model systems and may prove useful for examination of the pathological events leading to alcohol-associated cirrhosis in the absence of acute AH.

Financial Support:

This study was supported by grants AA027586 and AA012863 from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, and VA Merit Award I01BX004694.

List of Abbreviations:

- ALD

alcohol-associated liver disease

- AH

alcohol-associated hepatitis

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- ASH

alcohol-associated steatohepatitis

- HNF4

Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- ARGEMI J, LATASA MU, ATKINSON SR, BLOKHIN IO, MASSEY V, GUE JP, CABEZAS J, LOZANO JJ, VAN BOOVEN D, BELL A, CAO S, VERNETTI LA, ARAB JP, VENTURA-COTS M, EDMUNDS LR, FONDEVILLA C, STARKEL P, DUBUQUOY L, LOUVET A, ODENA G, GOMEZ JL, ARAGON T, ALTAMIRANO J, CABALLERIA J, JURCZAK MJ, TAYLOR DL, BERASAIN C, WAHLESTEDT C, MONGA SP, MORGAN MY, SANCHO-BRU P, MATHURIN P, FURUYA S, LACKNER C, RUSYN I, SHAH VH, THURSZ MR, MANN J, AVILA MA & BATALLER R 2019. Defective HNF4alpha-dependent gene expression as a driver of hepatocellular failure in alcoholic hepatitis. Nat Commun, 10, 3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELKNAP JK, CRABBE JC & YOUNG ER 1993. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 112, 503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENEDE-UBIETO R, ESTEVEZ-VAZQUEZ O, GUO F, CHEN C, SINGH Y & NAKAYA HI 221. An Experimental DUAL Model of Advanced Liver Damage. Hepatol Commun, 5, 1051–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENEDÉ-UBIETO R, ESTÉVEZ-VÁZQUEZ O, GUO F, CHEN C, SINGH Y, NAKAYA HI, GÓMEZ DEL MORAL M, LAMAS-PAZ A, MORÁN L, LÓPEZ-ALCÁNTARA N, REISSING J, BRUNS T, AVILA MA, SANTAMARÍA E, MAZARIEGOS MS, WOITOK MM, HAAS U, ZHENG K, JUÁREZ I, MARTÍN-VILLA JM, ASENSIO I, VAQUERO J, PELIGROS MI, ARGEMI J, BATALLER R, AMPUERO J, ROMERO GÓMEZ M, TRAUTWEIN C, LIEDTKE C, BAÑARES R, CUBERO FJ & NEVZOROVA YA 2021. An Experimental DUAL Model of Advanced Liver Damage. Hepatol Commun, 5, 1051–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTOLA A, MATHEWS S, KI SH, WANG H & GAO B 2013a. Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model). Nat Protoc, 8, 627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTOLA A, PARK O & GAO B 2013b. Chronic plus binge ethanol feeding synergistically induces neutrophil infiltration and liver injury in mice: a critical role for E-selectin. Hepatology, 58, 1814–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLEDNOV YA, METTEN P, FINN DA, RHODES JS, BERGESON SE, HARRIS RA & CRABBE JC 2005. Hybrid C57BL/6J x FVB/NJ mice drink more alcohol than do C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 29, 1949–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG B, XU MJ, ZHOU Z, CAI Y, LI M, WANG W, FENG D, BERTOLA A, WANG H, KUNOS G & GAO B 2015. Short- or long-term high-fat diet feeding plus acute ethanol binge synergistically induce acute liver injury in mice: an important role for CXCL1. Hepatology, 62, 1070–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COKER CR, AGUILAR EA, SNYDER AE, BINGAMAN SS, GRAZIANE NM, BROWNING KN, ARNOLD AC & SILBERMAN Y 2020. Access schedules mediate the impact of high fat diet on ethanol intake and insulin and glucose function in mice. Alcohol, 86, 45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRABBE JC, HARKNESS JH, SPENCE SE, HUANG LC & METTEN P 2012. Intermittent availability of ethanol does not always lead to elevated drinking in mice. Alcohol Alcohol, 47, 509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUBOIS V, STAELS B, LEFEBVRE P, VERZI MP & EECKHOUTE J 2020. Control of Cell Identity by the Nuclear Receptor HNF4 in Organ Pathophysiology. Cells, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAROOQ MO & BATALLER R 2016. Pathogenesis and Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Dig Dis, 34, 347–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARRELL G, SCHATTENBERG JM, LECLERCQ I, YEH MM, GOLDIN R, TEOH N & SCHUPPAN D 2019. Mouse Models of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Toward Optimization of Their Relevance to Human Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology, 69, 2241–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GÄBELE E, DOSTERT K, DORN C, PATSENKER E, STICKEL F & HELLERBRAND C 2011. A new model of interactive effects of alcohol and high-fat diet on hepatic fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 35, 1361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO B & BATALLER R 2011. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology, 141, 1572–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO B, XU MJ, BERTOLA A, WANG H, ZHOU Z & LIANGPUNSAKUL S 2017. Animal Models of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Relevance. Gene Expr, 17, 173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GELINEAU RR, ARRUDA NL, HICKS JA, MONTEIRO DE PINA I, HATZIDIS A & SEGGIO JA 2017. The behavioral and physiological effects of high-fat diet and alcohol consumption: Sex differences in C57BL6/J mice. Brain Behav, 7, e00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH DASTIDAR S, WARNER JB, WARNER DR, MCCLAIN CJ & KIRPICH IA 2018. Rodent Models of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Role of Binge Ethanol Administration. Biomolecules, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GONZALEZ FJ 2008. Regulation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha-mediated transcription. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, 23, 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO F, ZHENG K, BENEDE-UBIETO R, CUBERO FJ & NEVZOROVA YA 2018. The Lieber-DeCarli Diet-A Flagship Model for Experimental Alcoholic Liver Disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 42, 1828–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUCK I, GUNEWARDENA S, ESPANOL-SUNER R, WILLENBRING H & APTE U 2019. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 Alpha Activation Is Essential for Termination of Liver Regeneration in Mice. Hepatology, 70, 666–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HWA LS, CHU A, LEVINSON SA, KAYYALI TM, DEBOLD JF & MICZEK KA 2011. Persistent escalation of alcohol drinking in C57BL/6J mice with intermittent access to 20% ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 35, 1938–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITOH M, KATO H, SUGANAMI T, KONUMA K, MARUMOTO Y, TERAI S, SAKUGAWA H, KANAI S, HAMAGUCHI M, FUKAISHI T, AOE S, AKIYOSHI K, KOMOHARA Y, TAKEYA M, SAKAIDA I & OGAWA Y 2013. Hepatic crown-like structure: a unique histological feature in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice and humans. PLoS One, 8, e82163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOSHI-BARVE S, KIRPICH I, CAVE MC, MARSANO LS & MCCLAIN CJ 2015. Alcoholic, Nonalcoholic, and Toxicant-Associated Steatohepatitis: Mechanistic Similarities and Differences. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1, 356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOSHI K, KOHLI A, MANCH R & GISH R 2016. Alcoholic Liver Disease: High Risk or Low Risk for Developing Hepatocellular Carcinoma? Clin Liver Dis, 20, 563–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHANOVA E, WU R, WANG W, YAN R, CHEN Y, FRENCH SW, LLORENTE C, PAN SQ, YANG Q, LI Y, LAZARO R, ANSONG C, SMITH RD, BATALLER R, MORGAN T, SCHNABL B & TSUKAMOTO H 2018. Pyroptosis by caspase11/4-gasdermin-D pathway in alcoholic hepatitis in mice and patients. Hepatology, 67, 1737–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONO H, BRADFORD BU, RUSYN I, FUJII H, MATSUMOTO Y, YIN M & THURMAN RG 2000. Development of an intragastric enteral model in the mouse: studies of alcohol-induced liver disease using knockout technology. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg, 7, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARO R, WU R, LEE S, ZHU NL, CHEN CL, FRENCH SW, XU J, MACHIDA K & TSUKAMOTO H 2015. Osteopontin deficiency does not prevent but promotes alcoholic neutrophilic hepatitis in mice. Hepatology, 61, 129–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI Z, ZHAO J, ZHANG S & WEINMAN SA 2018. FOXO3-dependent apoptosis limits alcohol-induced liver inflammation by promoting infiltrating macrophage differentiation. Cell Death Discov, 4, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIEBER CS & DECARLI LM 1986. The feeding of ethanol in liquid diets. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 10, 550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIEBER CS & DECARLI LM 1989. Liquid diet technique of ethanol administration: 1989 update. Alcohol Alcohol, 24, 197–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU H 2016. Crosstalk of HNF4alpha with extracellular and intracellular signaling pathways in the regulation of hepatic metabolism of drugs and lipids. Acta Pharm Sin B, 6, 393–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORMAN ES, ODENA G & BATALLER R 2013. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis, management, and novel targets for therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 28 Suppl 1, 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANG JX, ROSS E, BORMAN MA, ZIMMER S, KAPLAN GG, HEITMAN SJ, SWAIN MG, BURAK K, QUAN H & MYERS RP 2015. Risk factors for mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis and assessment of prognostic models: A population-based study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 29, 131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QIN Y, GRIMM SA, ROBERTS JD, CHRYSOVERGIS K & WADE PA 2020. Alterations in promoter interaction landscape and transcriptional network underlying metabolic adaptation to diet. Nat Commun, 11, 962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REHM J & SHIELD KD 2019. Global Burden of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Liver Disease. Biomedicines, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHONFELD M, VILLAR MT, ARTIGUES A, WEINMAN SA & TIKHANOVICH I 2021. Arginine methylation of hepatic hnRNP H suppresses complement activation and systemic inflammation in alcohol fed mice. Hepatology Communications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEITZ HK, BATALLER R, CORTEZ-PINTO H, GAO B, GUAL A, LACKNER C, MATHURIN P, MUELLER S, SZABO G & TSUKAMOTO H 2018. Alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 4, 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENGUPTA M, ABUIRQEBA S, KAMERIC A, CECILE-VALFORT A, CHATTERJEE A, GRIFFETT K, BURRIS TP & FLAVENY CA 2021. A two-hit model of alcoholic liver disease that exhibits rapid, severe fibrosis. PLoS One, 16, e0249316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONG K, COLEMAN RA, ZHU X, ALBER C, BALLAS ZK, WALDSCHMIDT TJ & COOK RT 2002. Chronic ethanol consumption by mice results in activated splenic T cells. J Leukoc Biol, 72, 1109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIELE TE & NAVARRO M 2014. “Drinking in the dark” (DID) procedures: a model of binge-like ethanol drinking in non-dependent mice. Alcohol, 48, 235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TROUTMAN TD, BENNETT H, SAKAI M, SEIDMAN JS, HEINZ S & GLASS CK 2021. Purification of mouse hepatic non-parenchymal cells or nuclei for use in ChIP-seq and other next-generation sequencing approaches. STAR Protoc, 2, 100363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUKAMOTO H, FRENCH SW, BENSON N, DELGADO G, RAO GA, LARKIN EC & LARGMAN C 1985. Severe and progressive steatosis and focal necrosis in rat liver induced by continuous intragastric infusion of ethanol and low fat diet. Hepatology, 5, 224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUKAMOTO H, MATSUOKA M & FRENCH SW 1990. Experimental models of hepatic fibrosis: a review. Semin Liver Dis, 10, 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUKAMOTO H, MKRTCHYAN H & DYNNYK A 2008. Intragastric ethanol infusion model in rodents. Methods Mol Biol, 447, 33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO A, LAZARO R, WANG PY, HIGASHIYAMA R, MACHIDA K & TSUKAMOTO H 2012. Mouse intragastric infusion (iG) model. Nat Protoc, 7, 771–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALESKY C, GUNEWARDENA S, TERWILLIGER EF, EDWARDS G, BORUDE P & APTE U 2013. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha in adult mice results in increased hepatocyte proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 304, G26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YONEYAMA N, CRABBE JC, FORD MM, MURILLO A & FINN DA 2008. Voluntary ethanol consumption in 22 inbred mouse strains. Alcohol, 42, 149–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO J, ADAMS A, ROBERTS B, O’NEIL M, VITTAL A, SCHMITT T, KUMER S, COX J, LI Z, WEINMAN SA & TIKHANOVICH I 2018. Protein arginine methyl transferase 1- and Jumonji C domain-containing protein 6-dependent arginine methylation regulate hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha expression and hepatocyte proliferation in mice. Hepatology, 67, 1109–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]