Abstract

Regardless of the prevalence and value of change initiatives in contemporary organizations, these often face resistance by employees. This resistance is the outcome of change recipients’ cognitive and behavioral reactions towards change. To better understand the causes and effects of reactions to change, a holistic view of prior research is needed. Accordingly, we provide a systematic literature review on this topic. We categorize extant research into four major and several subcategories: micro and macro reactions. We analyze the essential characteristics of the emerging field of change reactions along research issues and challenges, benefits of (even negative) reactions, managerial implications, and propose future research opportunities.

Keywords: Reactions to organizational change, Research framework, Research issues, Systematic literature review

Introduction

During the past two decades, many studies have been conducted that have been interested in organizational change and the mechanisms that promote that process smoothly (Benford & Snow, 2000; Bouckenooghe, 2010; Caldwell et al., 2009; Pettigrew et al., 2001). Despite that wide interest in the process of organizational change, these studies reported negative results, as most of those efforts ended with an unsuccessful implementation of the process of organizational change and ultimately failure (Beer & Nohria, 2000; Meaney and Pung, 2008; Hussain et al., 2018). This is because the focus was on many secondary variables and ignored the most important factor of individual and organizational reactions towards organizational change in those studies (Oreg et al., 2011; Penava and Sˇehic, 2014). Herold et al., 2008; Holten and Brenner, 2015; Oreg & Berson, 2011; Alnoor et al., 2021).

A reaction towards a change is a cognitive and behavioral response based on an adaptation and a comprehensive understanding of how to react towards a change (AL-Abrrow et al., 2019b; Peng et al, 2020). This largely depends on how managers introduce a change and on the extent to which others respond. Usually, a negative reaction towards change happens when it is expected to result into more workload, uncertainty, and fatigue, especially when change is rapid and spans the whole organization or large parts of it (Beare et al., 2020; Li et al., 2017). Individuals’ reactions towards organizational change are expected to be dependent on the individual’s perception and assessment of the change effects on the individual. This suggests that a reaction towards a change is developed through the interactions between attitudes, beliefs, and feelings of an individual towards a change. A successful implementation of a change depends on how individuals interact with organizational change (Oreg et al, 2011; Shura et al., 2017). Participation in the change process is closely related with reactions towards a change. Practitioners are likely to be able to effectively diagnose and improve the willingness to change when they understand the need for change (Albrecht et al., 2020). Besides, people are more inclined to commit to a change if they perceive the change in alignment with their expectations and the resistance to change would be minimal (Helpap, 2016).

A positive reaction allows individuals to be more job focused and hence less resistance to change can be expected (Gardner et al., 1987). Similarly, a negative reaction towards change often generates a strong resistance to change. This happens if change is perceived as harming. Moreover, individuals’ resort to negative reactions when work relationships are threatened because of a change in a way that causes them to quit their job (Michela & Vena, 2012). However, some individuals are indecisive in their reactions towards a change, especially when future outcomes are unpredictable. This results into disruption and anxiety for both organizations and individuals, and thus reactions serve as the method aimed at dealing and engaging with change (Blom, 2018).

These considerations suggest that individuals react differently towards organizational change, depending on their respective perceptions. This invites a comprehensive study to understand the differences in reactions and to explain the main role that reactions play towards organizational change. Based on a systematic literature review, we provide a comprehensive framework that can help get an in-depth understanding of the reactions on organizational change. Earlier studies on precedents and consequences of change have been more concerned about reactions to organizational change (Akhtar et al., 2016). Despite the need of organizational change, many change initiatives fail (Beer & Nohria, 2000), mainly because of differences in individuals’ interactions in the change process (Oreg et al., 2011). Rafferty et al. (2013), developed a model to study individual level willingness to change. It was found that change based on interactions, homogeneous attitudes, and feelings are successful, and vice versa. Still, there is need to present a broader and more comprehensive theoretical framework based on earlier studies to better understand reactions towards change at different levels, i.e., micro and macro level. Although many researchers have contributed to conducting many studies to try to analyze the nature of cognitive and behavioral responses, for example, job satisfaction, individual performance, emotional intelligence, readiness for organizational creativity, and leadership abilities of all kinds (Malik and Masood, 2015; Malik and Masood, 2015). There are rare studies that dealt with reactions to organizational change at all levels, micro and macro (Khan et al., 2018). Thus, the number of studies that investigated reactions to change has increased, but the different types of study cases are still unknown to allocate the most critical determinants that contribute to positive and negative reactions to change. Hence, further investigation is needed. This systematic analysis seeks to provide useful insights into contexts of change reactions and to assist the authors in identifying current options and gaps in this type of study. Accordingly, our research meets the stated literary need. Our focus is to find how the subject of reactions towards change has been studied so far. The main goal is to provide a detailed methodological framework based on earlier studies, which explains the differences and trends in prior research. Additionally, we critically assess methodological issues and challenges found in previous research on reactions to organizational change, which can be overcome in future research. We plead for a changed perspective, which disentangles negative employee reactions to change from negative change outcomes. Rather, we argue that negative reactions can be interpreted as constructive criticism, which can improve the outcome process.

Methodology

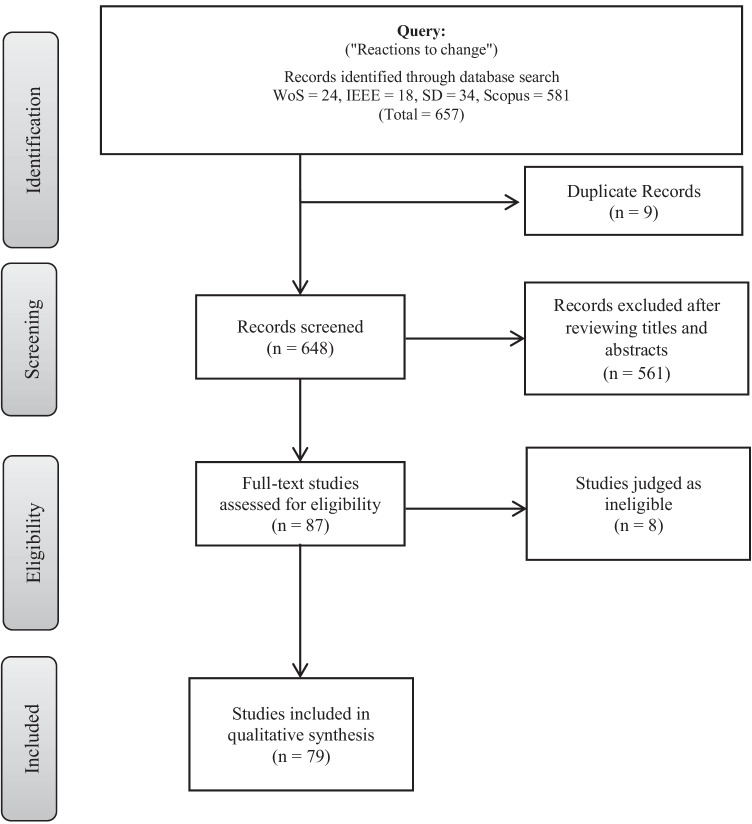

To archive our research goal, we conducted a systematic literature review. We used ‘reactions to change’ as the main key word to search relevant articles in four databases. We considered only those articles written in English, which is considered to be the predominant scientific language. Only peer-reviewed articles and conference papers were included. The current study was accomplished according to the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta Analyses’ (PRISMA) criterions (Moher et al., 2015). For systematic reviews, PRISMA suggests that counting on a single database search for literature should be avoided; no single database is likely to contain all relevant references. Therefore, extensive searching is recommended (Berrang-Ford et al., 2015; Monroe et al., 2019).

In particular, we used four major databases to assemble the literature sample: IEE Xplore, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science. These databases were selected based on their academic reliability and wider availability of relevant articles to discover the research gap and provide critical practical and theoretical implications (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017; Knobloch et al., 2011).

The selection process consisted of two phases of screening and filtration. First, duplicate articles found through matching of titles and abstracts were excluded. Second, articles were filtered after reading the entire article. This resulted in 79 articles (Fig. 1). Then, the main findings of the remaining articles were extracted and categorized.

Fig. 1.

Systematic review protocol

Results and discussion

A Critical overview of the change reactions literature

Previous studies of organizational change attempted to reach an increase in organizational effectiveness by focusing on organizational change and how change is implemented (Oreg & Berson, 2011; Oreg et al., 2011; Tavakoli, 2010; Tyler & De Cremer, 2005; Vakola et al., 2013; Van Dick et al., 2018; Walk & Handy, 2018; Whelan-Barry et al., 2003). The basic logic of such studies is based on the main assumption the positive or negative organizational consequences depend primarily on the extent to which individuals accept organizational change and their reactions to that change. Such a hypothesis is supported by many recent studies (Alfes et al., 2019; Borges & Quintas, 2020; Beare et al., 2020). Through the growing interest in researching the reactions of individuals towards organizational change. For example, the role of individuals’ reactions and how they interact with organizational change was examined within a time frame that spanned six decades from the end of the forties to 2022. A model was built on the basis of this research showing the relationship between the three main axes in the change process represented by the precedents of individuals’ reactions to change and responses to Their public actions and the consequences of that change (Oreg et al., 2011).

The vast majority of the total 79 studies relied on the longitudinal design in the research, and the other studies varied, including in adopting the type of design from transverse design to experimental studies, and 90% of those studies relied on data collection on self-reports of the study variables. Three main axes were discussed in terms of their relationship to the process of organizational change and the potential resistance that individuals come up with towards that change. Such three axes were represented by the cognitive axis, which is analyzed based on how individuals think about organizational change. The emotional axis by understanding and measuring the positive or negative feelings of individuals toward organizational change. The behavioral axis through which the extent to which the individual accepts or rejects organizational change appears (Bhatti et al., 2020; Constantino et al., 2021; Kashefi et al., 2012).

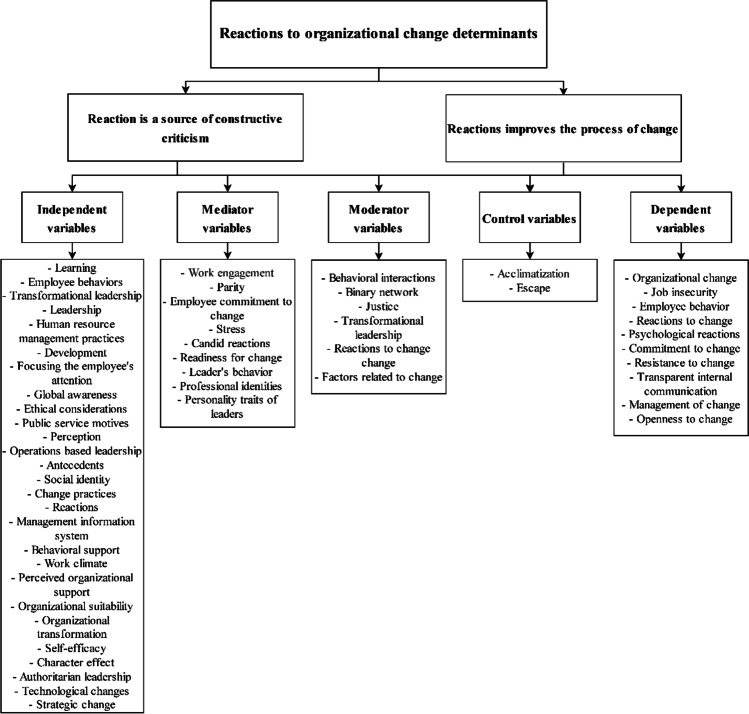

In recent years, factors such as the extent to which individuals accept organizational change and reactions to organizational change were the basic logic of previous studies that grew interested in researching the reactions of individuals towards organizational change (i.e., Roczniewska, & Higgins, 2019; Borges & Quintas, 2020; Du et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Prior studies have been focused on topics such as the psychodynamic explication of emotion, perception, behavior, and learning (Armenakis & Harris, 2009; Reiss et al., 2019; Tang & Gao, 2012; Al-Abrrow et al., 2019a; Borges & Quintas, 2020), the behavior of leadership (Fugate, 2012; Matthew, 2009; Alnoor et al., 2020), the focus of attention (Gardner et al., 1987), internal communication (Men & Stacks, 2014; Li et al., 2021), individual attitudes (Akhtar et al., 2016; Jacobs & Keegan, 2018; Liu & Zhang, 2019; McElroy & Morrow, 2010; Sanchez de Miguel et al., 2015), openness to change (Straatmann et al., 2016), and information systems (Bala & Venkatesh, 2017; Beare et al., 2020; Thirumaran et al., 2013). Figure 2 simplifies the determinants of reactions to change explored and investigated by the previous literature.

Fig. 2.

Determinants of reactions to change

Taxonomy of reactions to organizational change

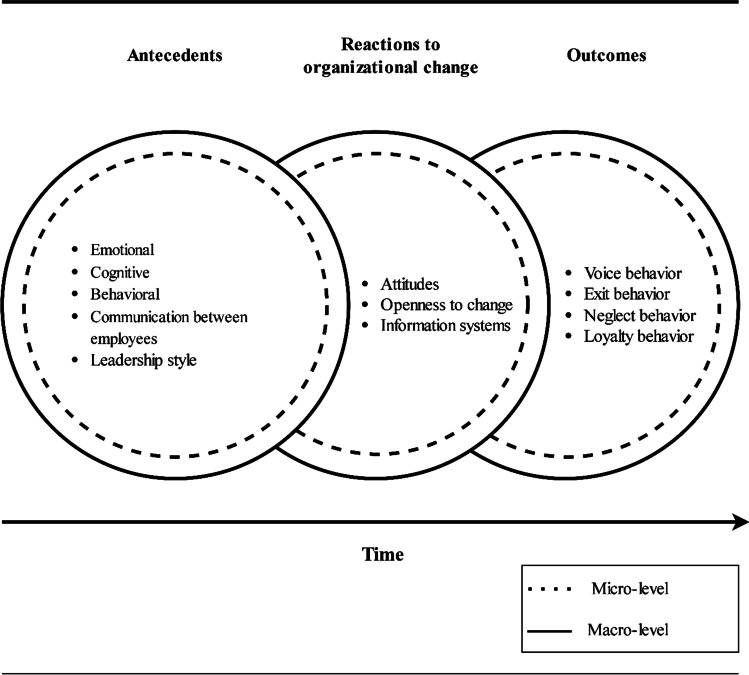

The remaining 79 articles were divided into four categories (Fig. 3) regarding the level of reactions towards change i.e., micro and macro level. There were 39 articles relating to micro reactions to change and 40 articles on macro reactions. Hence, these major categories were linked to their corresponding subcategories as shown in Fig. 3, depending on the frequency of relevance to ‘reactions to change’.

Fig. 3.

Taxonomy of reactions to change

Micro-level reactions

Antecedents of micro-level reactions

In this category, the research articles discuss aspects the antecedents of individuals’ reactions to organizational change. The subcategory contains major topics where reactions to organizational change was adopted with regards to (1) Emotional, cognitive, and behavioral therapy, (2) Communication between employees, (3) Leadership style, (4) Individual attitude, (5) Openness to change, and (6) Information systems.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

At the individual level, aims to help human resource to relieve emotional stress and reduce the need for associated dysfunctional coping behaviors. Hence, this set of studies discusses reactions to organizational change with psychodynamic perspective and include 19 studies. Four studies (Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001; Armenakis & Harris, 2009; Reiss et al., 2019; Tang & Gao, 2012) discuss emotional and motivational responses to organizational change and strategies to overcome these emotional and motivational challenges. The other nine studies discuss perceptions about organizational change. Beside this, to present a systematic analysis of positive psychology, one of the studies emphasized the relationship between perceptions about organizational support and resistance to change (Ming-Chu & Meng-Hsiu, 2015; Al-Abrrow et al., 2019a; Abbas et al., 2021b). According to Albrecht et al. (2020) and Hatjidis and Parker (2017) change engagement influences employees’ perceptions of organizational change. Thus, employees’ cognitive and behavioral reactions influence their perceptions of organizational change (Borges & Quintas, 2020). Endrejat et al. (2020) and Helpap (2016) argue that organizational communication reinforces employees’ positive perceptions of organizational change and affects their psychological mechanisms. Contrary to this, a negative awareness about organizational change causes psychological withdrawal or distancing from organization (Michela & Vena, 2012). Belschak et al. (2020) found that the Machiavellianism leads to negative perceptions and negative reactions to change. Organizational efforts to induce change are much consistent when employees are more concerned with change target (Gardner et al., 1987; Hadi et al., 2018). Six studies discuss two aspects of personality and health regarding employees’ reactions towards change. We found two articles, which describe that organizational justice and culture significantly influence employees’ personality. Additionally, job satisfaction, once change occurs, is critical to personality development (Bailey & Raelin, 2015; Caldwell & Liu, 2011). The remaining four articles encompass employees’ health related concern in relation to organizational change in health sector (Abbas et al., 2020; Fournier et al., 2021). It was found that organizational change is perceived as causing fear of job insecurity and health and safety issues among doctors, which resulted into less job satisfaction and reduced level of motivation (Størseth, 2006; Tavakoli, 2010; Al-Abrrow et al., 2021).

Communication between employees

Communication between employees originated from the concept of organizational transparency. Communication provides positive and negative information to employees in a timely manner. Furthermore, communication between employees enhances the organizational capacity of employees and holds organizations accountable for practices and policies (Li et al., 2021). Communication between employees includes transparency, accountability, participation, and informatics (Men & Stacks, 2014). The change can be planned or unplanned. Planned change is the discovery of problems that need improvement in a proactive manner. Unplanned change is imposed by external forces. Therefore, organizations must react flexibly and quickly to survive (Seeger et al., 2005; Alnoor et al., 2020). However, the lack of communication between employees creates barriers and threats to organizations towards increasing negative reactions to change. Planned and unplanned changes increase people's confusion and uncertainty. Therefore, employees' understanding of changes through communication between them is critical to the success of change (Gillet et al., 2013).

Leadership style

Leadership contributes 71% of the success of change amongst employees. Therefore, leadership and leadership traits were critical factors for change reactions for employees (Fugate, 2012). The openness of the leader increases the positive reactions to change. However, the resistance of the leader stimulates negative reactions to change from the employees (Matthew, 2009). Relationships with employees by leaders are critical determinants of successful change leadership (Alnoor et al., 2020). Leadership style affects employees in different ways, such as credibility and trust are important drivers of change for leaders to certify employee interests are considered. The literature confirms the leader-member exchange theory increases the negative reactions of employees to the change linked with corporate merger (Fugate, 2012). On the other hand, creative leadership and transformational leadership inspire employees and increase positive employee reactions. Change leaders are creative and transformative leaders (Matthew, 2009). In addition, practical leadership reduces employee resistance to change and increases individual interest in implementing change (Herold et al., 2008; Khaw et al., 2021).

Individual attitude

This set of studies discusses reactions to organizational change in relation to different individual attitude and included eight studies. Two studies discuss gender attitude, especially the reactions of female employees towards organizational change (Sanchez de Miguel et al., 2015). Similarly, employees differ in their attitude of reactions to organizational change depending on their age. Additionally, cultural and attitude differences cause numerous employee reactions towards organizational change (McElroy & Morrow, 2010). Three studies discussed the influence of employees’ respective experiences on their attitude of reactions towards organizational change. These studies assert that employees’ previous experiences are important to influence employees’ reactions to organizational change (Alas, 2007). A frequent exposure to organizational change causes change fatigue and cynicism and accordingly produce employees’ reactions to organizational change (Stensaker & Meyer, 2012). Thus, there is a relationship between the frequency of change and the reactions to change represented by exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect (Akhtar et al., 2016). On the other hand, the attitude of employees’ reactions towards organizational change in the public sector differs from the private sector in many ways, because the various processes of logistics and implementation. Therefore, the reactions of employees in the public sector are different compared to those in private sector. For this, the attitude of employees’ reactions in South African prisons to transformative changes in leadership were studied (Mdletye et al., 2013). In a policing context, 23 interviews were conducted, and it was concluded that the employees’ feedback began with three foci (me, colleagues, and organization) to assess change (Jacobs & Keegan, 2018). Moreover, a relationship between employees’ attitude in public service and their commitment to change was found (Liu & Zhang, 2019).

Openness to change

Four studies discussed employees’ openness to change in change and suggested that employability is related to positive emotions and higher level of employees’ openness to change in organizational changes (Fugate & Kinicki, 2008). Employees’ (dis) openness to change influences their emotional responses to organizational change (Saunders & Thornhill, 2011). It was found that the size and age of a company as well as employees’ expectations boost employees’ openness to change for the successful implementation of change (Lines et al., 2015). It is common that employees react whenever a new system is introduced. Yan and Jacobs (2008) studied employees’ trust and openness to change in relation to organizational change under the lean enterprise system. Two studies discuss diagnostic assessments, which are important during change implementation to deal with employees’ reactions to organizational change (Straatmann et al., 2016). Hence, creating interpersonal consensus promotes positive perceptions of change (Dickson & Simmons, 1970).

Information systems

This set of studies discusses reactions to organizational change in form of Information systems adoption and included six studies. For example, employees’ cognitive evaluation in reaction to Information systems implementation initiatives was discussed, which provided a deeper understanding of employees' feelings and perceptions of change (Kashefi et al., 2012). The authors claimed that a system can be designed to measure the feelings of individuals and customers towards the change implementation (Thirumaran et al., 2013). In another study, individuals' reactions to changes within supply chains were measured through the implementation of interorganizational business process standards (Bala & Venkatesh, 2017). Moreover, another study presented reactions of employees to digitally enabled work events and how digital technology affects employees ‘emotions (Beare et al., 2020). Lilly and Durr (2012), discussed the effect of implementing new technology on increasing the anxiety and stress among employees. Similarly, employees’ reactions towards technological change implemented in a bank were analyzed (Vakola, 2016).

Outcomes of micro-level reactions to organizational change

The change reaction leads to many outcomes and at different organizational levels. The range of literature examining employees' reaction to change is wide. Furthermore, the results of the literature review identified four vital categories: Voice behavior, exit behavior, neglect behavior, and loyalty behavior.

Individual voice behavior

Voice behavior is a type of organizational citizenship behavior differs from altruism, conscientiousness, and sportsmanship because such behavior is costly (Chou & Barron, 2016). Voice behavior is discussing problems with the administrator or staff, suggesting solutions, solve problems, and whistleblowing (Farrell & Rusbult, 1992). There is a high perceived risk of employee voice behavior. Nevertheless, organizations invest in voice behavior to make efficient management decisions and solve problems (Akhtar et al., 2016). The change literature has shown one of the consequences of change reactions is the voice behavior (Abdullah et al., 2021; Barner, 2008; Svendsen & Joensson, 2016). According to Ng and Feldman (2012) the higher employee voice behavior increases creativity, performance, exploration, and exploitation of ideas. Therefore, the voice behavior reduces anxiety and fatigue of individual toward organizational change. Previous literature has demonstrated voice behavior due to change increases employee turnover (Bala & Venkatesh, 2017). Individual voice behavior leads to undesirable results. In this context, change affects the social exchange and social relations between employees. Hence, organizational change reduces the quality of social exchange. Employees feel unappreciated and involved, which increases resistance to change (Zellars & Tepper, 2003). From a psychological perspective, the reaction to change is crucial for employees to express their opinions (Bhatti et al., 2020). Therefore, the voice behavior should be considered as a positive behavior that solves problems rather than identifying them (Whiting et al., 2012).

Individual exit behavior

Exit behavior is transferring, thinking about quitting, searching for a different job, and sabotage (Farrell & Rusbult, 1992). Most of the literature on reactions to change confirmed the main reason for employees to exit work is change (Akhtar et al., 2016; Bryant, 2006; Šedžiuvienė & Vveinhardt, 2018). However, there are two types of exit behavior, vertical and horizontal. Vertical mobility is moving upwards in the same organization. Horizontal mobility is the employee’s turnover of the organization (Davis & Luthans, 1988). Many firms view employee turnover negatively. The literature confirmed the employee turnover can be positive because it renews blood and increases the recruitment of skilled human resources (Elfenbein & Knott, 2015). Negative change reactions cause an increase in employee turnover. In this context, many human resources are transferred to other organizations. Such human resources bringing with them competitive advantages that increase innovation and creativity (Walk & Handy, 2018). Therefore, the literature confirms organizational inertia reduces organizational development. Hence, turnover allows work to correct organizational errors and provides further improvement for tasks (Piderit, 2000). Horizontal mobility due to change reduces organizational loyalty of employees caused by increased desire to search for new work (Carnall, 1986). In conclusion the reactions to organizational change contribute to the withdrawal of employees from the organization. However, employee turnover may promote to superior performance.

Individual neglect behavior

The literature indicates that one of the outcomes of micro-level reactions to organizational change is neglectful behavior (Akhtar et al., 2016). Employees who experience negative reactions to change contribute less organizational effort (Vantilborgh, 2015). Hence, individual neglect behavior is chronic lateness, reduced interest, increased error rate, and using firm time for personal business (Farrell & Rusbult, 1992). The change increases uncertainty due to several employees loses their jobs and positions. In this context, many employees underestimate the seriousness of their work (Svendsen & Joensson, 2016). Previous studies on organizational change have argued employees' reactions to change are a decisive factor in reducing efforts, decreasing work quality, and increasing absenteeism (Chou & Barron, 2016; Withey & Cooper, 1989). Therefore, negative reactions to change are negatively related to the time spent by the employee and the efforts made at work (Alnoor et al., 2022; McLarty et al., 2021).

Individual loyalty behavior

Loyalty behavior is waiting and hoping for improvement, giving support to the organization, being a good soldier, and trusting the organization to do the right thing (Farrell & Rusbult, 1992). Organizational change that maintains working relationships and psychological contracts with employees is likely to increase the strength of individuals’ loyalty due to the rule of reciprocity (Davis & Luthans, 1988). Individual realization that organizational change fulfills organizational commitment to individuals, strengthens the relationship amongst the organization and the individual (McElroy & Morrow, 2010). Negative employee reactions to change reduce individual loyalty (Constantino et al., 2021). Individual loyalty is the employee's readiness to maintain affiliation in the organization by giving attention to the goals and values of the organization (Aljayi et al., 2016). Individual loyalty receives outstanding consideration in the change literature because individual reactions to change can be a fundamental determinant of individual loyalty to the organization (Akhtar et al., 2016). Hence, job satisfaction and a positive reaction to change increase the emotional and mental connection of individuals to the organization (Milton et al., 2020).

Macro-level reactions

Antecedents of macro-level reactions

This category included 40 research articles, which discuss macro-level related aspects of reactions towards organizational change. In this category, the research articles consider aspects the antecedents of macro-level reactions. Major topics are (1) Organizational emotional, cognitive, and behavioral, (2) Organizational communication, (3) Leadership style, (4) Organizational attitude, (5) Organizational openness to change, and (6) Organizational information systems.

Organizational emotional, cognitive, and behavioral

Organizational reactions towards organizational change are informed by emotional, cognitive, and behavioral therapy of strategic changes such as mergers and strategic alliance. Strategic mergers can influence stakeholders’ decisions, which may result into negative reactions towards such merger (Basinger & Peterson, 2008; Bowes, 1981). This negative reaction is expressed through heightened anxiety levels and reduced emotional attachment (Rafferty and Jimmieson, 2010). Such a strategic change can lead to organizational exit (Schilling et al., 2012). Moreover, the effect of changes introduced by cross-border processes on organizational reactions was studied and it was found that there is an effect of dynamic cultures on organizational reactions towards change (Chung et al., 2014; Khaw et al., 2022).

Organizational communication

The second set of studies discusses reactions to organizational change regarding organizational communication. The lack of organizational communication caused organizational imbalances that negatively affected reactions towards organizational change in a way that tends to follow negative reactions such as an exit (Kruglanski et al., 2007). Weakness in organizational communication caused tension among employees and resulted into negative reactions towards change (Li et al., 2021). In this context, numerous environmental changes and crises have led to weak organizational communication during the change. For example, the recent Covid-19 pandemic that caused many barriers in organizational communication (Milton et al., 2020). Hence, when there is an abrupt change due to unexpected circumstances the organizational negative reactions would be increased towards change due to the lack of organizational communication (Fadhil et al., 2021).

Leadership

Transformational leaders’ reactions are affected by organizational change in a way that enhances their readiness for change and motivates them for increased participation and performance to support change (Faupel, & Süß, 2019). It was also found transformational leaders and their reactions are significantly related to change. Transformational leaders are committed and willing to bring change and react in a way to defuse resistance to change (Peng, et al., 2020). Transformational leadership facilitates a successful implementation of a change (Islam et al., 2021; Thomson et al., 2016). There is an influence of transformational leaders in supporting the change processes which commensurate with their positive reactions towards change (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020). Transformational leaders play an important role in shaping positive reactions towards organizational change and supporting the changes process (Busari et al., 2019). On the other hand, the success of a change process depends on leaders’ competency in inducing change, and transactional leadership can provide such competency. Transactional leadership encourages critical thinking and participation to ensure success of a change process (Khan, et al., 2018). As transactional leadership is supportive to change, it is helpful to reduce resistance to change (Oreg & Berson, 2011). Therefore, managers use their authority to support organizational change (Tyler & De Cremer, 2005). Organizational confidence in managers is a critical factor that generates positive managerial reactions towards organizational change (Du et al., 2020; Harley et al., 2006). However, change may generate negative managerial reactions of non-acceptance of change (Huy et al., 2014). The magnitude of managers response and their reactions depends on the degree and intensity of a change (Bryant, 2006).

Organizational attitude

There is an agreement between leadership and organizational change such that organizational attitude is employed in a way that reflects positive reactions towards organizational change (Fugate, 2012). It was found that, acceptance or rejection of change depends on the existing organizational attitude and measures taken to implement change (Bin Mat Zin, 2009). Hence, organizational wellness is positively related to the ability to deal with change. Moreover, leaders provide insight about how change affects the organization’s procedures, and this may help to overcome resistance to change (Alfes et al., 2019). Although change is inevitable, individuals struggle with change when their vision is unclear, which causes turmoil and increased anxiety. Additionally, individuals find it difficult to engage in organizational change when the organizational policies develop feelings of fear among individuals, and this causes resistance to change (Blom, 2018). Firms’ responses to organizational change requires confidence and adaptation necessary to engage with change, and this depends on the self-evaluation and the extent of accept the changes. Therefore, leaders highlight the change and call for a commitment to it (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2011; Rizzuto et al., 2014). Reactions towards change are dependent on firms' belief about change. Organizational actions and beliefs induce constructive change (Vakola et al., 2013).

Organizational openness to change

The literature found reactions pose a challenge for organization towards change when there is a lack of organizational openness to change. Therefore, employees have negative reactions towards change, while leaders have positive reactions that support the change process and help to get change accepted (Walk & Handy, 2018). Individual employees understand that change can create a complex situation, which can give rise to issues for employees, and they refute change. In contrast, leaders perceive change as beneficial to the organization and they support it. Leaders see change as one major requirement for the development of organization. Therefore, they encourage openness to change. Whereas individual employees are not opened to change because they perceive change will create organizational instability. Leaders encourage organizational activities, which facilitate change. In contrast, individuals express lower level of openness and acceptance to change (Rechter & Sverdlik, 2016). Leaders see the attainment of organizational and personal goal through change. Contrary to this, the lack of opened to accept change create incompatibility between the organizational goals and the change initiative (Roczniewska & Higgins, 2019). Explicit reactions to change can be interpreted in many ways, some of which involve the benefits of change, while others are related to the negative consequences of change (Oreg et al., 2011). Thus, employees do not show a stronger commitment to accept change, but leaders tend to understand a change (Mangundjaya et al., 2015).

Organizational information systems

Organizational information systems are a vital and significant resource for companies. Consequently, the huge development in information and communication systems led to taking proactive steps towards adopting innovative and modern technology (Hadid & Al-Sayed, 2021). The adoption of modern information systems has contributed to increasing organizational anxiety due to fear of change (Paterson & Cary, 2002). However, interest in new technology development by companies increases the potential for long-term downtime. Therefore, context conditions must be created to encourage organizational changes (Walk & Handy, 2018). Digital technologies have penetrated companies tremendously and rapidly. Rapid technological changes have transformed organizational work designs by increasing flexibility and empowerment (Beare et al., 2020). However, digital technologies have negatively affected the organization by not separating personal and work life (Chen & Karahanna, 2014). Digital technologies have created enormous social challenges through the constant bombardment of social media messages and emails (Vakola, 2016). Therefore, the working hours of employees have increased because they are sometimes obligated to respond. Furthermore, organizational information systems enhanced emotional reactions by increasing feelings of anger, unhappiness, and frustration (Andrade & Ariely, 2009).

In conclusion, the level-specific study offers an examination of the antecedents, associations, and implications of reactions to organizational change at the individual and organizational level. However, multilevel theories, methods, and analyses have gained popularity in recent years (Walk & Handy, 2018), and the reactions to organizational change have been studied in this manner. Several studies examine how reactions to organizational change operates across levels, while others use cross-level designs to examine how reactions to organizational change is concurrently influenced by variables at different levels. Exemplary studies for both kinds are discussed below and are arranged according to the main predictor variable (or variables) from the preceding categories.

Outcomes of macro-level reactions to organizational change

The change reaction indicates to various consequences at macro-level. Hence, the frequency of macro-level reactions to change, relating to the reaction typology suggested by Akhtar et al. (2016). Apart from voice, exit, loyalty, and neglect, we added social identity as the most frequently mentioned reaction type at the macro level.

Organizational voice

A positive organizational change results into a voice behavior where employees accept organizational change (Barner, 2008). However, change is without organizational support led in negative voice behavior such as employees’ resistance (Peachey & Bruening, 2012). Directing organizations has the enormous leadership task of listening to the voices of managers and employees about strategies for change (O'Neill & Lenn, 1995). The literature indicates responses to change, such as organizational voice behavior, leave managers stuck between fear of the future and respect for the past (Stylianou et al., 2019). Organizational voice behavior affects the professional and personal lives of managers and employees. Consequently, the practice of organizational changes causes the loss of many jobs, which is reflected on the feelings of managers and employees and causes ridicule, anger, anxiety, resentment, and organizational surrender (O'Neill & Lenn, 1995). Organizational voices due to change exacerbate organizational problems because of constant blaming of the chief executive officer. Organizational concerns are heightened by the difficulty of expressing opinions. In this context, organizational voices turn into sources of organizational mopping throughout the organization except perhaps the chief executive office (Barner, 2008). As a result, the negative reactions cause feelings of organizational anger and anxiety by increasing the difficulty of articulate the organizational voice.

Organizational exit

The literature shows negative reactions to change increase workplace bullying (Barner, 2008; Peachey & Bruening, 2012). Thus, reactions to organizational procedures encourage behavioral responses to organizational exit (Akhtar et al., 2016). Negative responses to organizational change are likely to be stronger in the exit behavior comparative with voice behavior (Balabanova et al., 2019). Because exit behavior is an assertive reaction that is associated with change and is not bound by organizational conditions (Farrell & Rusbult, 1992). Hence, exit behavior is risky because such behavior increases organizational disruption and stimulates harmful work behavior (Ng et al., 2014). Unexpected change leads to the organization's exit from the entrepreneurial work. In this context, organizations leave the entrepreneurial profession. Exiting creative and entrepreneurial businesses affects the company and the economy in general (Shahid and Kundi, 2021b). Negative reactions to change reduces motivation and self-efficacy, which increases organizational fatigue, impedes the implementation of organizational tasks, and causes exit (Surdu et al., 2018).

Organizational loyalty

Panchal and Catwright (2001) argued that organizational change is a complex process that makes it difficult for employees to accept such a process. Because routine work and many tasks affect change. Employees are significantly affected by frequent organizational change and are reflected in the practice of exit and neglect behaviors and low level of loyalty (Akhtar et al., 2016). Adopting successful organizational change increases positive reactions. However, most of the change literature confirms numerous change programs erupt and increase the negative reactions that occur through the practice of neglectful behaviors and lack of organizational loyalty (Bartunek et al., 2006). Organizational change increases stress, decreases commitment, and decreases loyalty. Frequent and ineffective changes produce negative responses and cause a decrease in job security. Consequently, the organization will suffer from low loyalty (Guzzo et al., 1994). Organizational loyalty decreases due to frequent changes lead to employees rethinking that continuing in this organization is not beneficial (Reiss et al., 2019). Such changes create uncertainty and cause organizational mopping (Constantino et al., 2021). Organizational change is a critical cause of low loyalty because inefficient changes increase negative organizational perceptions regarding social atmosphere, perceived promise, job content, and rewards (Van der Smissen et al., 2013). Therefore, increased negative reactions to change due to frequent and ineffective changes raises organizational perceptions of low loyalty and decreases organizational loyalty.

Organizational neglect

Hirschman (1970) proposed the employees' enactment of exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model and was expanded by (Farrell, 1983; Rusbult et al., 1988). The employees' enactment of exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model refer the decline of the organization creates many negative reactions that increase the deterioration in performance and reduce efficiency and learning, involving exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Reactions contributes to identifying failures and correcting tracks. Therefore, adverse behaviors assist the organization to deal with unfavorable situations, because the behavior of neglect and tardiness for work represents a communication strategy for the members of the organization (Meyers, 2020). Organizational neglect represents dishonorable behavior and organizational leniency. Organizational neglect behaviors include reduced attention and delay, reduced effort, increased absenteeism, increased error rates, and concern for personal issues at work (Lee & Varon, 2020). Unsuccessful organizational change is a major source of social loafing. Social loafing is the tendency of people to neglect work (Murphy et al., 2003). Thus, the reactions of employees at the organizational level contribute to reducing performance and increasing organizational failure (Abbas et al., 2021a; Akhtar et al., 2016).

Social identity

A fantastic reaction is generated by the members of the organization to protect and prove the social identity of the organization. Therefore, managing stability is as important as managing change in the context of social identity (Dutton et al., 1994). Organizational change affects some basic features of employees’ social identity, which leads to an imbalance in reactions towards change and causes uncertainty among individuals (Jacobs et al., 2008). The intense reactions of the members of the organization highlight the importance of organizational identity. Social identity is useful to understand and analyze reactions to deal positively with organizational change. For example, a weak social identity may lead to a negative reaction towards organizational change, such as disloyalty. Flexible social identity helps to give a quick response to organizational change and facilitates an anticipation of reactions towards change (Aggerholm, 2014). The success of organizational change and positive reaction is linked to the recognition of organizational identity based on the intention to remain in the organization and job satisfaction. Developing social identity in change programs reduces negative reactions to change (Clark et al., 2010). Łupina-Wegener et al. (2015) argued shared identity positively influences employees' perceptions of accepting change. Because the shared identity stimulates the transfer of organizational practices between units and departments after the post-change. Therefore, the organization must give employees a sense of continuity for the organization's bright future to practice transferring positive behaviors after implementing change programs (Jacobs et al., 2008).

Research issues and challenges

Previous research on reactions to organizational change is subject to several methodological issues and challenges. In the following, we asses methodological issues relating to research design, sector, country, research sample, techniques, and variables (Table 1). Compared to a multitude of other management subjects, research on reactions to organizational change shows both its strengths and limitations. Furthermore, it seems that similar problems are relevant at different levels of analysis. To a certain extent, a reaction to organizational change literature advances systematically, while other subject areas have not progressed as much.

Table 1.

Issues and challenges of research on reactions to organizational change

| Reactions to organizational change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Issues and Challenges | |||||

| Research design | Sector | Country | Research sample | Techniques | Variables | |

| Antonacopoulou and Gabriel (2001) | √ | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Armenakis and Harris (2009) | √ | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Barner (2008) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Casey et al. (1997) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Faupel and Süß (2019) | √ | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Fugate (2012) | √ | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Fugate and Kinicki (2008) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Gardner et al. (1987) | √ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hatjidis and Parker (2017) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Jacobs and Keegan (2018) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Kruglanski et al. (2007) | √ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Liu and Zhang (2019) | √ | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Oreg et al. (2011) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Peng et al. (2020) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Santos Policarpo et al. (2018) | - | - | √ | - | - | - |

| Reiss et al. (2019) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Saunders and Thornhill (2011) | √ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Straatmann et al. (2016) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Tavakoli (2010) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Tyler and Cremer (2005) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Vakola et al., (2013) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Van Dick et al. (2018) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Chung et al. (2014) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Dickson and Simmons (1970) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Fournier et al. (2021) | - | - | √ | - | - | √ |

| Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller (2011) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Kennedy-Clark (2010) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Li et al. (2021) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lines et al. (2015) | - | √ | √ | - | - | - |

| Mangundjaya et al. (2015) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Milton et al. (2020) | - | √ | - | - | - | - |

| Ming-Chu and Meng-Hsiu (2015) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Rechter and Sverdlik (2016) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Rizzuto et al. (2014) | - | - | - | √ | √ | - |

| Roczniewska and Higgins (2019) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Thomson et al. (2016) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Valitova et al. (2015) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Peachey and Bruening (2012) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Kashefi et al. (2012) | - | √ | √ | - | - | - |

| Thirumaran et al. (2013) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Yan and Jacobs (2008) | - | - | - | √ | - | - |

| Bin Mat Zin (2009) | √ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Belschak et al. (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aggerholm (2014) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Alas (2007) | - | - | √ | - | - | - |

| Albrecht et al. (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alfes et al. (2019) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Bailey and Raelin (2015) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Bala and Venkatesh (2017) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Basinger and Peterson (2008) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bayraktar and Jiménez (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Beare et al., (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Borges and Quintas (2020) | - | √ | - | √ | - | - |

| Busari et al. (2019) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Caldwell and Liu (2011) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sanchez de Miguel et al. (2015) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Du et al. (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Endrejat et al. (2020) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Harley (2006) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Helpap (2016) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Huy et al. (2014) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lilly and Durr (2012) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| McElroy and Morrow (2010) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Michela and Vena (2012) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rafferty and Jimmieson (2010) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Šedžiuvienė and Vveinhardt (2018) | - | - | - | √ | - | √ |

| Stensaker and Meyer (2012) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Bryant (2006) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Walk and Handy (2018) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Størseth (2006) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Khan et al. (2018) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Schilling et al. (2012) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Oreg and Berson (2011) | - | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Tang and Gao (2012) | √ | - | - | - | √ | - |

| Akhtar et al. (2016) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Belschak et al. (2020) | - | √ | - | - | - | - |

| Blom (2018) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Jacobs et al. (2008) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mdletye et al. (2013) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

| Vakola (2016) | - | - | - | - | - | √ |

Reactions to organizational change as a multidimensional construct

Evidence has collected that a five-factor multi-indicator CFA model fits Akhtar et al. (2016) and Van Dick et al. (2018) reactions to organizational change measure at the individual levels of analysis (e.g., Exit, neglect, loyalty, voice, and social identity). Using first-order CFA, Akhtar et al. (2016) found an “modest fit” with one sample. Elsewhere, both Bryant (2006) and Šedžiuvienė and Vveinhardt (2018) found satisfactory fit for a two-factor (i.e., Exit and voice) latent model. Divergent validity of the five-dimensional reactions to organizational change scale was shown by Akhtar et al. (2016) who discovered that it was different from a single order factor. It should be noted that in addition to obtaining evidence supporting the discriminant validity of the reactions to organizational change dimensions from negative affectivity, job satisfaction, and psychological climate Van Dick et al. (2018) examined the relationships between social identity and voice behavior. Researcher Aggerholm (2014) was able to show the discriminant and convergent validity of reactions to organizational change, namely, the capacity to increase organizational misbehavior, working relationship with a supervisor, decrease trust in one's supervisor, and work performance, with unrespect to work engagement and job satisfaction.

There has been relatively little team-level CFA work done as compared to work done at the individual level. It should be clear that this fact comes from the truth that it is very difficult to sample enough teams to do studies for this kind of analyses. Although CFA models have been applied to the Walk and Handy (2018) individual and organizational outcomes but without respect multilevel model. This produces a discontinuity between the amount of investigation and the amount of theory used (Maynard et al., 2012). While we believe this is a promising approach, we encourage researchers to use multilevel CFA methods when conducting analyses that seek to elucidate the construct validity of aggregate variables, with the goal of the study being the total number of teams in the focus population. Concurrently, there is no published research on whether two- and four-dimensional forms of reactions to organizational change provide equivalent criterion-related validity. Here, future studies could compare the two measures, determine whether there are important changes between the various versions, and investigate if the various conceptualizations maintain validity and stability through time and cultures by respecting the assessment of measurement model. In addition, we think that these problems offer valuable topics for future study. In this context, there was vital issue which is related to assessment of structural model. Moreover, there is no study combination of structural equation modeling and artificial neural network. Hence, they did not consider the two mains of benefits the combination of structural equation modeling and artificial neural network is that the use of multi-analytical two-phases SEM–ANN method tool up two vital benefits. First, it allows for further validation of the SEM analysis findings. Second, this approach captures not just linear but also dynamic nonlinear interactions between antecedents and dependent variables and a more accurate measure of each predictor's relative power as well. Furthermore, the potential future work can use SEM-ANN model to determine the reactions to organizational change by adopting multilevel model.

Mono-method issues

At the individual and team levels, most research done on reactions to organizational change consists of questionnaires asking workers about antecedents, correlates, and consequences of such reactions. Any common measurement or percept-percept biases will increase observed associations (Maynard et al., 2012). These biases are intensified if both variables are measured at the same time. Three percent of the individual-level research utilized a different source, whereas 97 percent used self-reported criteria measures. Individual-level reactions to organizational change are more likely to be biased by monothiol bias, resulting in inflated correlations, while team-level relationships are less likely to be distorted by monothiol bias. In keeping with this result, Mangundjaya et al. (2015) showed that task performance correlated more strongly with the reactions of individuals when responses were obtained through self-report measures than when responses were collected by other means. Reactions to organizational change have been operationalized in different ways throughout the literature at each level of study. Reactions to organizational change, as measured and studied at both the individual and team levels, are each shown in the literature as being in two-dimensional, four-dimensional, and aggregated forms. However, yet, there has been no study to account for the disparate measuring methods that may influence the correlations shown in studies like this. Therefore, we believe future studies should examine how measuring approaches influence such correlations.

Mediator and moderator inferences

As mentioned before and shown in Fig. 2, reactions to organizational change are usually regarded as a mediator between the characteristics of people and environments and outcomes, regardless of the substantive level of study. The validity of mediational effects is contingent on a variety of variables, most notably the accuracy of the assumed causal chain connecting antecedents to reactions to organizational change and to outcomes (Chung et al., 2014; Li et al., 2021). As shown in the contribution section, 49% of individual-level studies and 16% of team-level studies used cross-sectional designs. The studies conducted so far have shown nothing in the way of causation or association between organizational change and reactions at the level of analysis. Additional work exploring how direct impacts are mediated and/or studying variables that may mitigate such direct effects appears to hold across different levels of analysis in which reactions to organizational change have been examined. Researchers to date have mostly examined things that serve as antecedents to reactions and results that are influenced by reactions to organizational change. According to the authors of the paper Walk and Handy (2018), job crafting acts as a mediator in explaining the connection between the perceived effect of change and people's reactions to organizational change. Hence, there are many additional possible mediators that have not yet been studied. In fact, the few research that investigate how specific connections within the reactions to organizational change influence other possible moderators are found at different levels of analysis. And thus, we believe that it is the appropriate moment for those interested in the influences that mediate and moderate reactions to organizational change to investigate many facets that are intricately intertwined in these responses.

Research design

Research design refers to a general strategy chosen to integrate various components of a study in a coherent and logical manner. It is always challenging to choose an appropriate research design because sometimes a chosen design does not align with the data. For example, a longitudinal design often used in qualitative studies can be time consuming due to nature of data (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020; Faupel & Süß, 2019; Liu & Zhang, 2019). Similarly, the descriptive design may not generate the required results due to inability to control the tendencies of the individuals involved in data collection (Barner, 2008; Bin Mat Zin, 2009). Some of the studies that have been covered focus on cross-sectional or one-way design, but they are not generalizable because they may be biased (Vakola et al., 2013). In addition, future studies should use longitudinal designs that allow tracking of changes at organizational levels and aim to collect data from multiple sources (Barner, 2008; Chung et al., 2014; Fournier et al., 2021; Kashefi et al., 2012; Oreg et al., 2011), while other studies called to follow the method of interviews that extract information and provide insight into the nature of change processes in organizations (Jacobs & Keegan, 2018; Saunders & Thornhill, 2011). An improved understanding of the long-term consequences of organizational transformation might enhance the reactions to such studies. Gerwin (1999) proposed managers could empower teams throughout the life cycle, for example, while the teams are forming, maturing, and growing. According to Gerwin (1999), organizational change may take place as a cycle, and it is the role of reactions to these changes to push the cycle in one direction or another.

Sector

The sector refers to research site where the study is to be conducted and can be public or private organization as per the study requirements. Choosing a public sector as study site may be problematic for change related studies because public sector employees resist change and can generate biasness in responses (Borges & Quintas, 2020; Kennedy-Clark, 2010; Santos Policarpo et al., 2018; Milton et al., 2020). Studies conducted in industrial organizations do not allow generalization of the results because these organizations require changes in terms of organizational structures, strategy, and operating procedures, but they are not on a large scale. Thus, results could not be generalized, and such studies should be conducted in other organizations (Mangundjaya et al., 2015). Studies in service sector (hotels, hospitals) give great importance to adopting actual change (Hatjidis & Parker, 2017). As a result, it must be considered when generalizing to all other service organizations, as there may be fundamental differences between organizations. Future research should focus on other service sectors such as banking (Vakola, 2016). Regarding security issues, the effect of the organizational identity on the change processes of national security institutions has been verified, and the results of these studies cannot be generalized because the changes that are made may lead to imbalances with the organizational culture in other organizations (Belschak et al., 2020; Jacobs et al., 2008). In addition, researchers can focus on industrial companies such as technological industries, digital technologies, wired and wireless communication companies (Tang & Gao, 2012).

Country

Countries differ from one another in many ways. Hence, the result of a study conducted in one country may not be generalized to other countries. Similarly, economic, social, and political restrictions among countries may reduce the possibility of generalization of research findings across countries (Fournier et al., 2021; Lines et al., 2015; Tang & Gao, 2012). Some studies focused on one country without considering the role of the social and political factors of other countries, Therefore, the results of these studies cannot be generalized to other countries (Kashefi et al., 2012; Mangundjaya et al., 2015). As a result, future studies are encouraged to use data from other countries to conduct comparative analyzes, which may allow generalization (Fournier et al., 2021; Straatmann et al., 2016). A study of Blom (2018) in manufacturing industries of South Africa, which included a sample of companies interconnected with the parent company, and thus studied the opinions of employees from other countries. As for studies conducted in developing countries, their results are not generalizable, as the behavioral responses in these countries differ from those in European countries (Busari et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Consequently, the country differs in many ways in terms of productive and social capabilities, and this may be a limitation in several countries (Huy et al., 2014; McElroy & Morrow, 2010).

Research sample

A sample represents a component of population chosen to provide the required data. There is problem when sample size is too small to generalize the result to larger population (Šedžiuvienė & Vveinhardt, 2018; Yan & Jacobs, 2008). Similarly, a larger sample may provide the data which may not be relevant to the study objectives (Rizzuto et al., 2014; Stensaker & Meyer, 2012). Most of the studies discussed focused on collecting data from individuals working in different organizations. However, there is a strong tendency to conduct more studies that enable data collection in other contexts to highlight the roles of leaders and managers to participate in providing support for change processes (Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001; Barner, 2008; Jacobs & Keegan, 2018). Moreover, the choice of the sample determines the fate of the study, whether it is possible to generalize or not. The larger sample size, the greater the possibility of generalization (Šedžiuvienė and Vveinhardt, 2018; Yan and Jacobs, 2008). Sample selection was problematic during the pandemic period because there were difficulties in collecting data and accessing responses (Li et al., 2021). In addition, some authors have dealt with specific groups in state-owned organizations, but such studies were hard to generalize as they need more verification and other opinions to prevent bias (Lines et al., 2015). More studies shed light on urging researchers to survey the opinions of users and beneficiaries at all organizational levels to reach the results. The researchers were also urged to take into consideration the age composition of the polarized sample before embarking on organizational change initiatives (McElroy & Morrow, 2010).

Techniques

Among the other challenges that some studies faces are the choice of statistical methods to analyze the data because the chosen methods may be not suitable for data and the results are less convincing (Bin Mat Zin, 2009; Chung et al., 2014). Many researchers have used exploratory studies, which are of great importance in drawing conclusions. However, previous studies focused on use such design in one context and limits the possibility of generalization (Jacobs & Keegan, 2018; Vakola et al., 2013). Researchers also used interviews for a specific number of employees, which caused biasness in reactions (Jacobs & Keegan, 2018; Saunders & Thornhill, 2011). Therefore, focusing on other methods such as observation to see the impact of reactions to change will provide motivational cases and ideas worth sharing (Kruglanski et al., 2007). Some studies used structural equation modeling, which revealed the suitability of this technique for experimental research (Borges & Quintas, 2020; Faupel & Süß, 2019; Gardner et al., 1987). Likewise, some studies used a questionnaire and performed analysis, such as multiple regression and content analysis, which is considered a qualitative method in analyzing data and interpreting its meaning and provides an opportunity for researchers to choose different issues (Alas, 2007; Busari et al., 2019; Chung et al., 2014; Tavakoli, 2010). Although these analyses have proven their worth in extracting results, it requires researchers to use deep statistical analysis to reach generalizable results (Hatjidis & Parker, 2017; Huy et al., 2014). The researchers urged for future studies to use surveys and conduct comparative analysis between groups that would reduce time bias in the data (McElroy & Morrow, 2010).

Variables

The selection of incorrect variables may generate the biased result, or the variables may not be able to sufficiently serve the purpose of study and researchers need to add more variable to get rich data (Albrecht et al., 2020; Tyler & De Cremer, 2005). Table 1. Explain the issues and challenges of reactions organizational change in this regard. One of the limitations that some studies faced is they did not examine the personal characteristics of individuals, such as the influence of traits and the role of personality in directing reactions, as individuals with a high degree of negative influence of traits tend to follow the opposite reactions, neglecting this aspect may cause bias (Huy et al., 2014). It was also noted the studies discussed focused on the pace of change and trust in management and still there is necessity to discuss other variables that are highly related to change such as organizational culture, employee communication, commitment, fairness, job characteristics, resistance to change, psychological context, individual incentives, and anxiety of change (Busari et al., 2019; Lines et al., 2015; Oreg et al., 2011). Given the behavioral aspect is very important in human studies, addressing the use of behavioral support for organizational performance contributes to improving the reaction to change processes (Fournier et al., 2021). Moreover, considering technological development and intense competition between current organizations, the use of management information system will reduce behavioral and organizational problems (Dickson & Simmons, 1970). Researchers called for attention to the problem of studying the planned organizational change on a large scale in a place where employees do not have a voice, and the opportunities for participation are limited and the resistance to change is extreme (Fugate, 2012; Jacobs & Keegan, 2018). As a result, the changing organizations face huge challenges and spend massive amounts of resources on training and developing their employees (Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001).

Benefits of (Even Negative) reactions to organizational change

The purpose of this systematic review is to expand theory and the understanding on reactions to organizational change by incorporating ideas from several disciplines (e.g., psychology, sociology, complexity sciences, and institutional perspectives). Many studies on organizational change reactions have concentrated on the causes or outcomes of these reactions, with a specific focus on resistance and, therefore, rather negative outcomes. Organizational change is often a necessity caused by external threats, such as intense competition (Oreg et al., 2011; Tavakoli, 2010). To implement change, the cooperation of employees is required (Antonacopoulou & Gabriel, 2001; Hatjidis & Parker, 2017; Peng et al., 2020). However, a mixture of psychological, social, emotional, and cultural dimensions in employees’ reactions can negatively interfere with the process of organizational change itself (Armenakis & Harris, 2009).

In this section, we attempt to change this perspective and, based on the findings in Sect. 3.1, formulate several propositions, which may enable organizations to overcome negative reactions and transform them into positive change outcomes. Basically, we argue that (1) negative reactions can be seen as a source of constructive criticism, (2) which can be used to improve the change process. Employees can be viewed as a critical authority in an organization, which might evoke new perspectives on the change process. The provided constructive criticism points to issues that require further attention by the organization. The antecedents, process, and outcomes of the change process are more thoroughly analyzed regarding possible weaknesses and strengths, which can improve the whole change process (Fournier et al., 2021; Straatmann et al., 2016). In particular, this encourages those in charge to address shortcomings and help facilitate change processes (Jacobs & Keegan, 2018). It can also help increase communication between members of the organization during various stages of organizational change (Li et al., 2021). Listening to employees’ objections might reduce the complexity of change (Chung et al., 2014; Fugate, 2012; Reiss et al., 2019) and can motivate and empower them to contribute to the success of change processes (Casey et al., 1997; Kruglanski et al., 2007; Tavakoli, 2010).

Theoretical recommendation

The results of this review revealed several critical variables and factors that had been investigated in previous research on change responses. There are many challenges and benefits that academics should take into consideration. Hence, understanding the negative and positive effects of change reactions can be an essential key concept to the successful implementation of organizational change. The results of an extensive literature review show allowing human resources to participate and rush into change programs increases the likelihood of successful implementation of planned and unplanned change. The leadership style has a strong and significant role in adopting change. Theoretically, the literature has proven the transformational and transactional leadership style are vital leadership styles that raise positive reactions to organizational change (e.g., Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020; Busari et al., 2019; Faupel, & Süß, 2019; Khan, et al., 2018; Oreg & Berson, 2011; Peng, et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2016). The leadership aspect is of fantastic importance in the success of implementing change because the leader has ability to inspire employees towards increasing levels of motivation and deliver the message of change with the lowest level of negative reactions. Because leadership styles achieve mutual gain between individuals by giving individuals a sense of power to adjust or accept the changes that occur in the organization. This review expanded the communication's vision of change by identifying reactions in four integrated behaviors (i.e., Exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect) that explain why individuals reject, resist, accept and embrace change.

Understanding reactions to change plays a critical role in enhancing individuals' cognitive, emotional experiences, and perceptions of changes. The results of this study shed light on the implementation of change during crises. The results prove epidemics and sudden consequences lead to lack of resources and loss of market share. There is huge benefit in adopting and responding to change programs amid crises, especially in the aftermath of unexpected crises, such as the COVID-19. Although crises add a significant burden to organizations in implementing change, it is necessary to face crises with a fantastic deal of courage, confidence, and communication to reduce exit reactions and disloyalty amongst employees. Supporting human resources and creating a work context with less organizational mopping leads to positive results and increases the success of organizational change adoption (Barner, 2008; Qin et al., 2019). Adopting organizational change is an emotional process based on individuals' feelings and perceptions of change. Organizational change causes high levels of anxiety and tension. Because the individual adversely interferes with aspects of organizational change in a manner that creates the feeling of anxiety increased and loss of identity. However, reactions to organizational change are varied and may be positive by increasing job satisfaction and granting of responsibility. In this context, the reactions toward change may be negative also by increasing the likelihood of unsuitability of change with the organizational work. Furthermore, academics and practitioners should be concerned with the sensory and emotional aspects of how individuals react to organizational change. Because the organizational changes that include providing importance to the emotions and feelings of staff as part of the change process can encourage employees to change the attitude towards change and cooperate with current events (Beare et al., 2020).

Organizational communication is important for understanding people's emotions and perceptions of change. Communication before and post organizational change provides people with suitable and timely information, creates a sense of delegation of responsibility for change, and mitigates negative responses to organizational change (e.g., Basinger & Peterson, 2008). Academics can use the results of this review to understand change reactions from an organizational and individual perspective and to highlight challenges and barriers to implementing change. Analyzing and examining organizational elements such as organizational communication and organizational attitudes provides solutions while implementing change. Additionally, sharing responsibilities and integrating roles between participants in the change increases the results achieved from adopting organizational change. This review confirms there is a dearth of investigation into the influence of psychological context factors such as individual incentives, change anxiety, and organizational mopping on post change results at the individual and organizational level. Studying reactions to organizational change at different organizational levels contributes to identifying differences and similarities to reactions at multiple organizational levels. In this context, using the results of this review by academics and practitioners contributes to reducing negative reactions and increases the chances of successful implementation of change programs.

Conclusion

Many studies highlight the importance of change efforts in contemporary organizations to address external threats. However, employees’, i.e., change recipients’, cognitive and behavioral responses to change often result in resistance. A comprehensive perspective of past research is required to have a clear understanding of the causes and consequences of responses to change. For this reason, we have conducted a systematic literature review on this subject. Much of what has been discovered before may be categorized into these four levels: micro and macro level responses. An in-depth analysis of the literature helped identify the antecedents, effects, benefits, challenges, and recommendations associated with reactions to organizational change.

Our findings have managerial implications. Based on the literature review, we derive recommendations for change agents to facilitate the issues experienced by researchers whilst studying reactions to organizational change. Insights from our literature review highlighted both positive and negative aspects of reactions towards change. Accordingly, we divided these studies into two groups discussing positive and negative aspects. The positive aspects highlight the importance of reactions in supporting change and broadening the view of the motives for change (Armenakis & Harris, 2009; Gardner et al., 1987; Mangundjaya et al., 2015). This increases employees’ participation and positively affects their perceptions of change (Faupel & Süß, 2019; Straatmann et al., 2016; Paterson & Cary, 2002; Bin Mat Zin, 2009). In addition, there is a significant correlation between reactions, emotional commitment, self-respect, and optimism (Fugate & Kinicki, 2008; Liu & Zhang, 2019; Vakola, 2016), and this depends on administrative support to reduce the negative feelings towards change implementation. The stronger communication between individuals, the more it has a positive effect towards improving reactions to change (Tang & Gao, 2012). The leadership plays a big role in directing reactions by providing opportunities to participate in decision-making, build confidence, and give individuals compensation opportunities (Khan et al., 2018). Likewise, individuals’perception of change depends on their reactions and behaviors (Hatjidis & Parker, 2017; Rechter & Sverdlik, 2016; Saunders & Thornhill, 2011). As the human being consists of a group of elements (emotional, mental, spiritual, and physical), when one of these elements is disrupted, it affects the other elements, which requires equal attention to these elements in order have a coherence and non-conflicting reactions (Blom, 2018).