Abstract

Authentic or naïve embryonic stem cells (ESC) have probably never been derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of pig blastocysts, despite over 25 years of effort. Recently, several groups, including ours, have reported induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) from swine by reprogramming somatic cells with a combination of four factors, OCT4 (POU5F1)/SOX2/KLF4/c-MYC delivered by retroviral transduction. The porcine (p) iPSC resembled human (h) ESC and the mouse “Epiblast stem cells” (EpiSC) in their colony morphology and expression of pluripotent genes, and are likely dependent on FGF2/ACTIVIN/NODAL signaling, therefore representing a primed ESC state. These cells are likely to advance swine as a model in biomedical research, since grafts could potentially be matched to the animal that donated the cells for re-programming. The objective of the present work has been to develop naïve piPSC. Employing a combination of seven reprogramming factors assembled on episomal vectors, we successfully reprogrammed porcine embryonic fibroblasts on a modified LIF-medium supplemented with two kinase inhibitors; CHIR99021, which inhibits GSK-3beta, and PD0325901, a MEK inhibitor. The derived piPSC bear a striking resemblance to naïve mESC in colony morphology, are dependent on LIF to maintain an undifferentiated phenotype, and express markers consistent with pluripotency. They exhibit high telomerase activity, a short cell cycle interval, and a normal karyotype, and are able to generate teratomas. Currently, the competence of these lines for contributing to germ-line chimeras is being tested.

Keywords: pig, naïve, primed, induced pluripotent stem cell, embryonic stem cell

Naïve and primed embryonic stem cells

Authentic or “naïve” embryonic stem cells (ESC) (Nichols and Smith, 2009), the pluripotent stem cell lines derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of the embryo, were first established from certain strains of d 3.5 mouse (m) embryos over 30 years ago (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981). Such established mESC lines are characterized by their dependence on LIF/STAT3 signaling for maintenance of pluripotency (Hall et al., 2009), the positive effects of BMP4 for self renewal and resistance to differentiation (Ying et al., 2003), and tendency to differentiate in response to activation of the FGF2 and ACTIVIN/TGFB signal transduction pathways (Li et al., 2009). Naïve ESC are also tolerant to passaging as single cells, show no signs of either senescence over extended culture doublings and, in female lines, of X chromosome inactivation. As they are pluripotent, mESC have the ability to differentiate into cell types representing the three main germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm) both in vitro and in vivo, and to give rise to germ-line chimeras and even the whole animal after being introduced into pre-implantation embryos (Evans, 2005; Wobus and Boheler, 2005). This latter attribute, which has allowed genes to be ablated or added (“knock-outs” and “knock-ins”, respectively) to the genome has helped elevate the mouse to become the principal mammalian model employed in biomedical research and may have led to other, physiologically more relevant models such as pigs (Roberts et al., 2009a) to become neglected.

Following the initial success with some, but not all strains of mouse, ESC were also later derived from monkey and human blastocysts (Thomson et al., 1998; Thomson et al., 1996). Despite being of ICM origin, these pluripotent lines were clearly dissimilar to those from the mouse and were characterized by their more flattened colony morphology and dependence on FGF2 and TGFB/ACTIVIN/NODAL signaling rather than on LIF/STAT3 for maintenance of their pluripotency (Dvorak et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2005). Human ESC rapidly differentiate when exposed to BMP4 (Das et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2002), and at least a partial inactivation of one of the X chromosomes occurs in female cell lines even when they are cultured under conditions that maintain an undifferentiated state (Silva et al., 2008). In addition, ESC from primates undergo apoptosis if they are dissociated into single cells for routine subculture and, probably, as a result, have proven difficult to cryopreserve efficiently and to transfect. Two other practical considerations relating to the culture and maintenance of hESC (Ezashi et al., 2005; Westfall et al., 2008) are, first, that they are much more prone to undergo spontaneous differentiation than their mouse counterparts, and, second, that they divide more slowly, properties that together make standard laboratory practice much more demanding for the researcher. Finally, human and mouse ESC differ in their display of cell surface antigens. While, the carbohydrate antigen SSEA1 is expressed on mESC, it is low or absent on hESC, and a series of different complex carbohydrate entities, including SSEA-3 & 4, are displayed on the human cells (Henderson et al., 2002). Together, these dissimilar properties emphasize that mouse and primate ESC are in many respects distinct, despite exhibiting the common feature of pluripotency.

Intriguingly, ESC derived from gastrulation (egg-cylinder) stage mouse embryos share striking similarities to hESC in terms of their flattened morphology, lack of dependence on LIF for maintenance, and susceptibility to trophoblast and germ cell differentiation upon BMP4 treatment, and have been named “primed” or epiblast stem cells (EpiSC) to distinguish them from the naïve, ICM-derived ESC discussed first. Such cells also differ from naïve ESC in their epigenetic status and lack of competence to form germ-line chimeras (Brons et al., 2007; Tesar et al., 2007). Such “primed” ESC have, therefore, been considered to represent a more advanced “differentiated” state than that exhibited by the naïve ESC, possibly as the result of ERK1-mediated perturbations of the ground state of the latter (Nichols and Smith, 2009). On the other hand, such primed ESC can be converted to naïve status by genetic manipulation (Hanna et al., 2010) or even by altering culture conditions (Bao et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2010), underscoring the plasticity of both stemness states. Accordingly, it is debatable whether hESC, which are derived from the ICM of human blastocysts, represent a more differentiated state than mESC, especially as there appear to be only a few underlying differences between these two cell types and that these differences are primarily based on how the cells direct LIF, BMP4, ACTIVIN/NODAL and FGF2 inputs (Greber et al., 2010). Nevertheless, from a practical perspective, there would appear to be at least two predominant types of ESC, ones that are dependent on FGF2 and ACTIVIN/NODAL signaling, (for convenience referred to here as either FGF2-dependent or primed ESC), and those, whose self-renewal and pluripotent state depends upon LIF/STAT3 and BMP4 (referred to as LIF-dependent or naïve ESC).

Pluripotent stem cells from pig

Attempts to derive porcine ESC (pESC) began at least two decades ago (Notarianni et al., 1991; Notarianni et al., 1990; Piedrahita et al., 1990), but establishment of well defined naïve pESC has continued to remain elusive. There have been many explanations for this failure, but none of them particularly convincing (Flechon et al., 2004; Telugu et al., 2010). The different culture requirements of mESC and hESC emphasized that homologous pig cells might have similarly fastidious requirements and that direct application of established culture conditions and methodologies simply might never work (Brevini et al., 2007; Keefer et al., 2007; Talbot and Blomberg le, 2008; Telugu et al., 2010; Vackova et al., 2007). Nonetheless, in some instances, porcine lines have shown some measure of stemness, including an ability to be maintained in culture for prolonged periods (Evans et al., 1990), to form teratomas, and, in one instance, to give rise to chimeras (Chen et al., 1999). Recently, however, porcine cell lines have been generated from the embryonic disc of d 10.5–12 pig conceptuses that were dependent on ACTIVIN/NODAL signaling but not on LIF, differentiated into trophoblast and germ cells upon BMP4 treatment, and could give rise to teratomas (Alberio et al., 2010). These cell lines, like those from human blastocysts, clearly fall into the primed ESC class and their existence underscores the commonality of the FGF2-dependent pluripotent state across very different species. On the other hand, naïve ESC have proven to be particularly difficult to establish from ungulate species, including the pig.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)

The establishment of hESC immediately suggested a potential use for such cells in regenerative medicine. Although, ethical concerns preclude many applications of hESC that are feasible with mESC, the human cells hold enormous therapeutic promise in tissue repair and replacement, and for gene therapy (Odorico et al., 2001). Therefore, the reports that mouse fibroblasts (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006) and human somatic cells (Lowry et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008a; Park et al., 2008b; Takahashi et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007) could be re-programmed empirically to a pluripotent state to create induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), with properties similar to ESC via introduction of just a handful of “stemness” genes in retroviral vectors created great excitement, as such a technology promised the prospect of “personalized” stem cells with a perfect genetic match to a patient. Over the four years since the paper describing mouse iPSC (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006), there have been numerous reports describing improved vectors to minimize the expression of the re-programming genes in the re-programmed cells, a widened range of differentiated cells that can be converted to iPSC, means of improving the efficiency of the technology through new combinations of genes and pharmacological agents, and better protocols for driving differentiation of the iPSC along specific lineages (Cox and Rizzino, 2010; Kiskinis and Eggan, 2010; Shao and Wu, 2010). Reprogramming procedures developed for mouse and human cells have also been adapted to an increasingly broad spectrum of species, including swine (Esteban et al., 2009; Ezashi et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009). Curiously, derivation of iPSC by using the general Takahashi and Yanamaka reprogramming approach yields either naïve or primed stemness states and not both, depending on the species. For example, mouse iPSC tend to have the general properties of naïve state ESC, while human iPSC and all the porcine lines so far reported have features of the primed state.

Although nuclear reprogramming per se is not an entirely novel concept, since it can be accomplished by fusion of somatic cells with ESC (somatic-stem cell hybrid) (Cowan et al., 2005; Do and Scholer, 2004; Tada et al., 2001) and also by somatic cell nuclear transfer into an enucleated egg (Briggs and King, 1952; Gurdon et al., 1985; Wilmut et al., 1997), advances achieved in the generation of iPSC are beginning to provide insights into the genetic and epigenetic underpinnings of the process, making it a less empirical practice (Hanna et al., 2009b, Sridharan et al., 2009). Appreciation of the biochemical networks maintaining the pluripotent state and the application of pharmacological agents, especially inhibitors of intracellular signaling pathways, has spearheaded successful attempts to derive naïve, LIF-dependent stem cell lines from previously “difficult” species, e.g. rats, human (Buehr et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008) and non-permissive mouse strains, such as NOD (Hanna et al., 2009a). In this paper, we describe the establishment of two kinds of porcine (p) iPSC from embryonic fibroblasts, one analogous to FGF2-dependent hESC, and the other to LIF-dependent mESC.

We foresee a considerable value in the use of piPSC for investigating safety and efficacy of tissue regeneration-based medicine before such technologies are used to treat humans. The pig, with its relatively long lifespan, is similar in body size, organ physiology, and morphology to the human making it ideal for investigating long term effects of transplantation therapies. It also provides a much cheaper and publicly acceptable alternative to primates (Brevini et al., 2007; Hall, 2008; Roberts et al., 2009b, Vackova et al., 2007).

Induced porcine pluripotent stem cells analogous to FGF2-dependent primed ESC

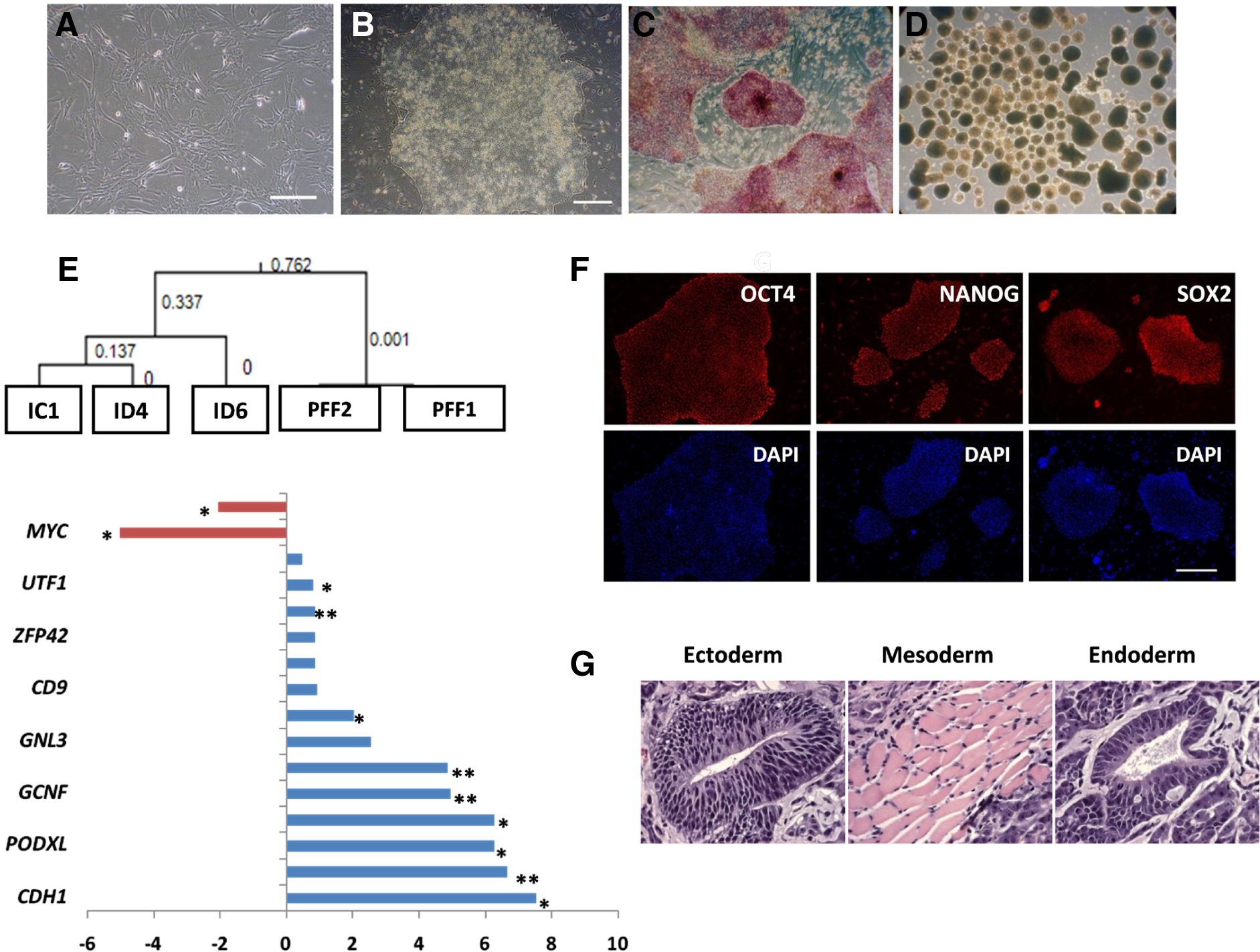

Through use of the classical combination of OCT4 (POI5F1)/SOX2/KLF4/c-MYC reprogramming factors, and conditions used to culture hESC, i.e. a feeder layer of irradiated embryonic fibroblasts and supplementing the medium with FGF2 and knock-out serum replacement (KOSR) medium, three independent groups almost simultaneously described the derivation of piPSC from somatic cells (Fig. 1A) (Esteban et al., 2009; Ezashi et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009). Barring a few exceptions, the piPSC from all three groups displayed almost identical phenotypes. For example, the colonies in each case resembled those of hESC, i.e. they were flattened (Fig. 1B), and positive for alkaline phosphatase (Fig. 1C). They also expressed genes typically associated with pluripotency (Fig. 1 E,F), and the cells could form teratomas in immuno-compromised mice (Fig. 1G).These data and the culture conditions employed suggest that the default stemness state for the ungulate iPSC is the primed rather than the naïve condition.

Fig. 1. Porcine iPSC lines derived from porcine fetal fibroblasts (PFF).

(A) Phase contrast image of PFF founder cells. (B) Representative piPSC colony resembling primed ESC following reprogramming of PFF. Such colonies begin to form ~ 3 weeks following viral infection. The colonies are alkaline phosphatase-positive (C), and the cells are capable of differentiating into embryoid bodies (D). (E) Hierarchical clustering of candidate piPSC lines analyzed by Porcine Affymetrix microarrays. Note the close clustering of the two PFF lines and the relative variability of three selected iPSC lines, including ID6. Changes (log2) in transcript concentrations of the ID6 line relative to the starting PFF cells were analyzed for significance (* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01). Note the up-regulation of porcine pluripotency genes in the reprogrammed cells (in blue), but the down-regulation of endogenous KLF4 and c-MYC (in red). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis confirms the expression of OCT4 (POU5F1), SOX2 and NANOG in the ID6 cell line [Bar, 100 μm]. (G) Teratoma derived from one of the representative piPSC lines (ID6) revealed a contribution to all the three germ layers. All data are from Ezashi, et al. (Ezashi et al., 2009) with permission from Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA.

Transcriptome analysis of the piPSC lines (Ezashi et al., 2009) (Fig. 1E) revealed the expression of many genes typically associated with pluripotency, including OCT4, CDH1, PODXL, LIN28, GCNF, GNL3, ZFP42, UTF1, TDGF1, ACVR2B, plus some signature EpiSC genes CLDN6, SAFB, GATA6 (Tesar et al., 2007), and downregulation of genes characteristic of the naïve state ESC such as PECAM1 and TBX3. A full characterization by microarray data was necessarily limited because porcine arrays still remain poorly annotated and are also probably missing many genes. Hence, it is not possible at present to comment on the presence or absence of several other genes in addition to the ones listed above that are diagnostic of either the primed state, e.g. Nodal, Otx2, Lefty1&2, Foxa2, Eomes, Dkk1, Sox17, Cer1, or naïve state, e.g., Dppa3, Dazl, Stra8, Fbx015, Piwil2, Gbx2, in mouse. Nonetheless, based on the overall phenotype of the cells it seems reasonable to conclude that all the piPSC so far described are analogous to FGF2-dependent hESC. However, the necessity for FGF2 supplementation and reliance on ACTIVIN/NODAL/TGFB inputs are features that require confirmation. This uncertainty about FGF2-dependence is especially relevant in view of the fact that Wu et al. (Wu et al., 2009) were able to maintain the iPSC they generated without the addition of FGF2, as long as doxycycline, the inducer of transgene expression was supplemented to the medium. In addition, the existing confusion surrounding the presence or absence of carbohydrate markers SSEA1,-3,-4, TRA-1-60 and TRA-1-81 among the various piPSC needs to be resolved as well (Roberts et al., 2009b).

In addition to the possible lack of FGF2-dependency of the piPSC, a recent report suggests that such cells, unlike mEpiSC, can give rise to chimeras with apparent high efficiency (West et al., 2010). These iPSC were derived from mesenchymal stem cells of bone marrow by expressing a combination of six genes, which included NANOG and LIN28 in addition to the usual four. The resulting colonies were cultured on FGF2-supplemented medium, although dependency on the growth factor was not examined. When the cells were injected into d 4.5 in vivo derived embryos and these embryos transferred to surrogate dams, the iPSC contributed to 29 of 34 live piglets as judged by analysis of ear and tail DNA. Of the 9 fetuses examined in the 2nd trimester of gestation, all demonstrated chimerism in a wide range of tissues representing the three germ layers, as well as in the gonads and the placentae. The expression in placenta marks a departure from the accepted paradigm that “true” ESC do not contribute to the placenta (Niwa et al., 2005). It seems possible that the use of primed state piPSC, which have an inherent susceptibility for spontaneous differentiation into trophoblast (Ezashi et al., 2005), could be one of the potential reasons for the contribution to the placenta. Finally, if germline transmission from the chimeric offspring can be demonstrated, another widely accepted paradigm about the nature of the primed state will have been overturned.

Induced porcine pluripotent stem cells analogous to LIF-dependent, naïve ESC

This laboratory became interested in creating naïve piPSC for a number of reasons. First we inferred, now possibly incorrectly in view of the publication by West et al. (West et al., 2010), that they would contribute to chimeras more easily than primed iPSC. Second, we reasoned that such cells would be simpler to propagate and manipulate genetically than their primed counterparts. Our approach has been based on the strategies used to generate LIF-dependent naïve ESC from blastocysts of rat (Buehr et al., 2008), a proverbial “non-permissive species”, by supplementing the medium with two protein kinase inhibitors (so-called “2i” medium). One of these, PD0325901 (PD), blocks the mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK) pathway, while the second CHIR99021 (CH), targets glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3B). The resulting lines were validated as ESC by both in vitro and in vivo pluripotency criteria, and their cells could contribute to germ-line competent chimeras. The same inhibitor combination was later demonstrated to increase the efficiency of iPSC generation (Li et al., 2009). Pharmacological interventions that activate the pathways directed by c-MYC (Marson et al., 2008) and KLF4 (Lyssiotis et al., 2009), namely CH, a component of 2i-medium described above, and kenpaullone (KP), which is a selective inhibitor of GSK-3B and cyclin B/CDK1 (Lyssiotis et al., 2009) also aided the creation of ESC from “difficult” mouse strains, such as NOD. Based on these results, we hypothesized that it would also be possible to derive piPSC by applying similar modifications to the culture medium.

The same porcine fetal fibroblasts expressing enhanced GFP (GFP-PFF) previously employed to generate primed piPSC (Ezashi et al., 2009) were reprogrammed by means of episomal rather than integrating lentiviral vectors according to the methodology outlined by Yu et al. (Yu et al., 2009). The episomal plasmids contain an EBNA1-based origin of replication which facilitates maintenance of the plasmid as an extra-chromosomal component replicating once for every round of cell division as long as antibiotic selection is maintained. The advantage with this approach over the lentiviral system is that once reprogramming is achieved the plasmids carrying the reprogramming genes are envisioned to be maintained for only a few passages in the absence of antibiotic selection. The plasmids used for reprogramming (Addgene, MA, USA) and the general approach are outlined in Fig. 2. GFP-PFF (106) were transfected by nucleofection twice (on d 1 and d 4 after passage) by using the NHDF nucleofection kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). The cells were subsequently plated onto irradiated MEF feeders and maintained on a modified LIF-based 2i medium (DMEM-F12; 20 % KOSR;1 μM PD; 3 μM CH; 250 units of hLIF/ml) (Hanna et al., 2009a). In addition, 1 μM of VPA, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, was also included to promote reprogramming (Huangfu et al., 2008). Following 10 days on the MEF (d14), the transfected cells were dissociated with TrypLE (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and plated onto a new feeder plate. Thirty days after the first nucleofection, 18 alkaline phosphatase positive colonies appeared on the plate (Fig. 2C). After initial characterization for expression of endogenous pluripotent genes, three colonies, designated II, IV and XV, representing the order in which they were picked, were selected for further characterization. These cells possessed all the hallmarks of reprogrammed cells, including the activation of endogenous pluripotent genes (Fig. 2B), and displayed high telomerase activity (Fig. 3C), tolerance to dissociation by trypsin and passage as single cells, plus a relatively short cell cycle interval (13 h for line XV). The cultures showed no signs of senescence over 30 passages (approximately 160 doublings) and appeared to be pluripotent as evident by their ability to form teratomas (Fig. 4).

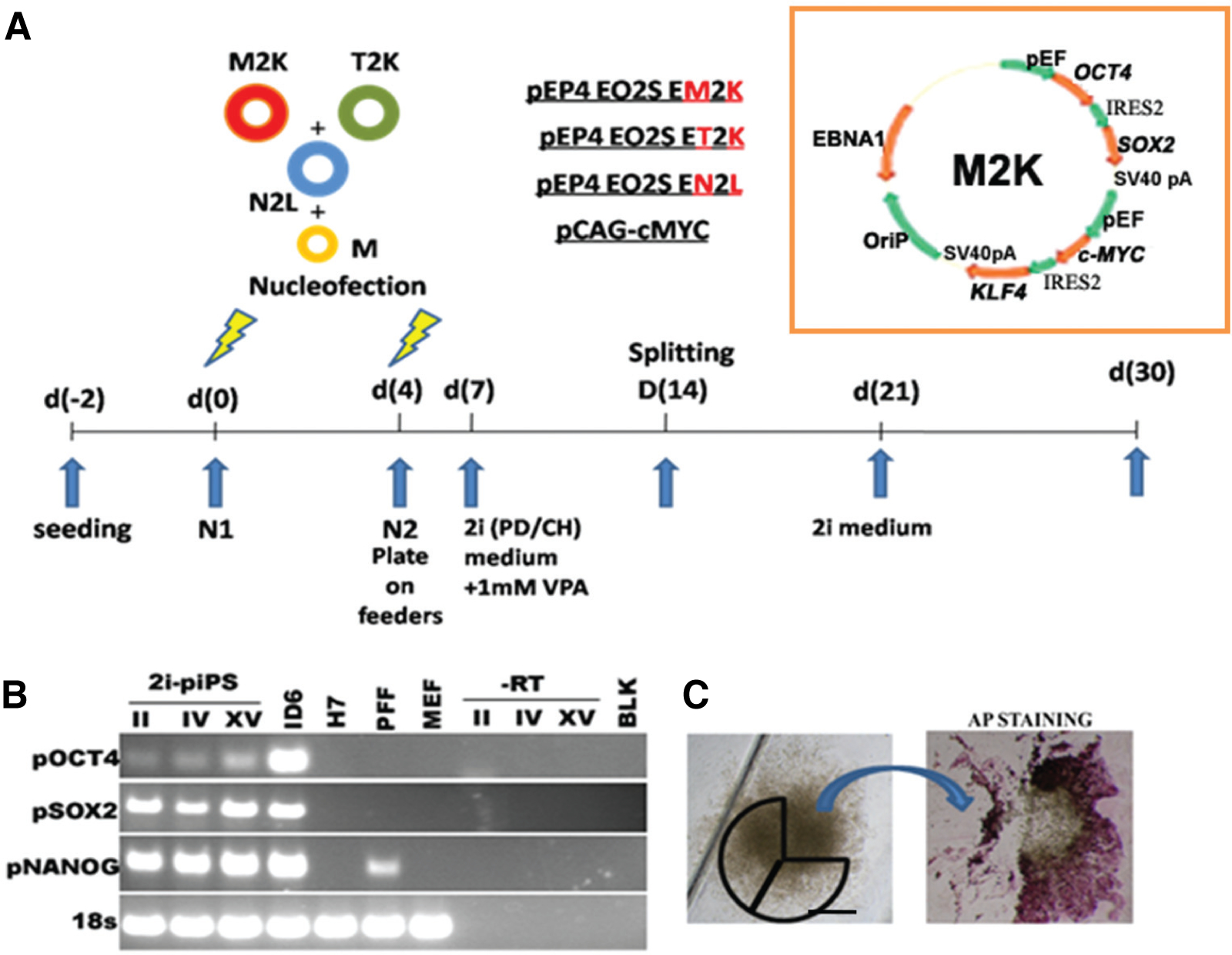

Fig. 2. Derivation of piPSC analogous to naïve ESC by using episomal plasmids.

(A) Schematic outlining the episomal plasmids carrying a combination of human reprogramming factors (Yu et al., 2009) in addition to a mouse c-Myc expression plasmid (Okita et al., 2008), and the general experimental protocol are shown. An expanded illustration of one of the episomal vectors is also displayed. All the episomal vectors consist of a combination of OCT4 (POU5F1) and SOX2 separated by an IRES2 site (O2S), followed by combinations of c-MYC and KLF4 (M2K), NANOG and LIN-28 (N2L) and T-antigen and KLF4 (T2K), each also separated by IRES2 site. In the insert, EBNA1 represents the Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 site; OriP is origin of replication and pA is a polyadenylation signal. While all the episomal plasmids are driven by the EF1 promoter, the constitutive mouse c-Myc is driven by a CAG promoter. All plasmids were obtained from Addgene. One million porcine fetal fibroblasts expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP-PFF) were nucleofected twice on d 1 and d 4 after passage by using the NHDF nucleofection kit (Lonza). Following the second nucleofection, the cells were plated onto mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeders and maintained on a modified LIF-based 2i medium (PD/CH) and supplemented with 1 μM valproic acid (VPA) for 2 weeks. On d 30 putative colonies were picked for further expansion and culture. (B) RT-PCR analysis of cDNA from respective piPS clones II, IV and XV with primers described previously (Ezashi et al., 2009). ID6, a piPS clone described in Fig. 1 was used as a positive control. Also analyzed were the hESC line,H7, PFF, and MEF. A no-RT and no-template (blank) controls were utilized to demonstrate porcine specific expression of pluripotent genes. (C) Typical iPS colony before and after alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining. The markings represent the sections of the colony used for propagation before AP staining.

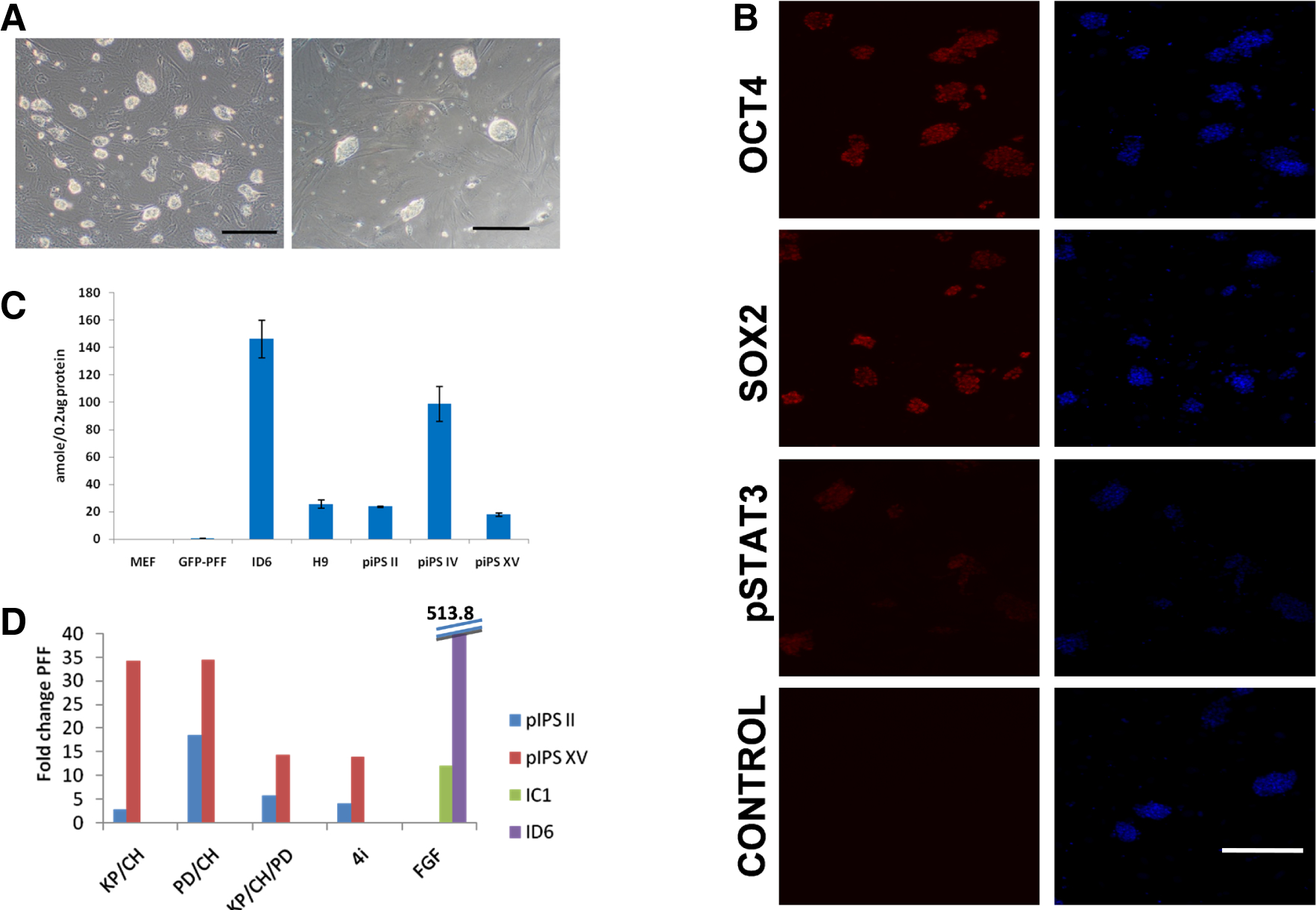

Fig. 3. Characteristics of “naïve” piPSC.

(A) Typical morphologies of completely reprogrammed piPS II on 2i medium, two (left) and three (right) days following plating on the feeder cells [Bar: 200 μm]. Note several small, compact and glistening colonies appearing from apparently single cells typically observed two to three days following passage. (B) Fluorescent microscope images of immunostaining for OCT4 (POU5F1), SOX2, and phosphorylated STAT3 of piPS clone II after 3 days in culture. The colonies were stained by previously described reagents and protocols (Ezashi et al., 2009) for OCT4 and SOX2. For phosphorylated STAT3 staining, Phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (Cell Signaling) antibody was used at 1:50 dilution alongside OCT4 and SOX2 staining using similar protocols. Note the specific nuclear localization of OCT4, SOX2 and phosphorylated STAT3 (Red). Nuclear staining was performed by using DAPI (blue) [Bar: 200 μm]. (C) Telomerase activity in 0.2 μg total protein from three piPSC lines (II, IV and XV) was measured by TRAPeze® Telomerase Detection Kit (Millipore, MA, USA) (Ezashi et al., 2009). While the telomerase activity is baseline in MEF and GFP-PFF control lines, such activity is higher in the three iPS lines (II, IV and XV) and comparable to or higher than the activity in the hESC line (H9), but less than that of the FGF2 dependent piPSC line (ID6). (D) Effect of different inhibitor/medium combinations on the maintenance of a pluripotent state as evaluated by endogenous pOCT4 expression. Two piPSC lines (II and XV) following 5-Aza treatment for two days were cultured in the LIF-medium containing the kinase inhibitors in four different combinations, PD/CH, KP/CH, PD/KP/CH (3i), and 3i + A83-01 for four passages before harvesting RNA for quantification of endogenous OCT4 levels by real time RT-PCR (Ezashi et al., 2009). The inhibitors were used at the indicated concentrations: PD (PD0325901; Stemgent, USA) 1 μM; CH (CHIR99021; Stemgent, USA) 3 μM; KP (Kenpaullone; Sigma, USA) 5 μM; and A83-01 (Tocris Bioscience, USA) 1 μM. Two previously characterized primed lines cultured on the FGF2 medium (IC1 and ID6, Fig. 1) were also included for comparison. The values represent fold change compared to PFF. Of all the inhibitor combinations tested, PD/CH preserved highest expression of endogenous OCT4 in both the lines examined. Interestingly, such expression, although comparable to that of one of FGF2-dependent iPSC line (IC1), is less than one-tenth the expression of the other (ID6).

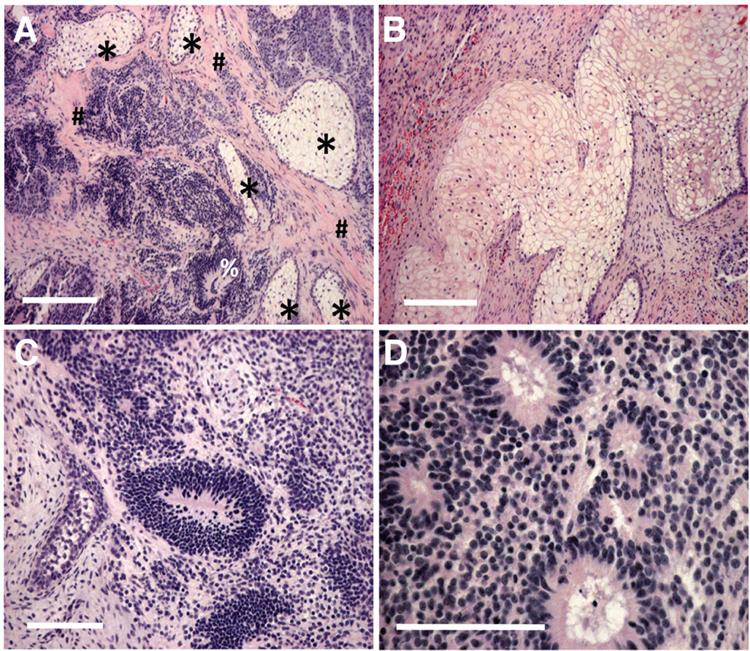

Fig. 4. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of formaldehyde-fixed teratoma tissue derived from piPSC, clone II, transplanted subcutaneously in a NOD-SCID mouse and grown for 12 weeks.

(A), Two mesodermal origin tissues, cartilage (*) and smooth muscle tissue (#) and neural epithelium (%) (ectoderm) can be observed. (B) cartilage tissue (C) Neuronal epithelium and (D) epithelium with brush border (endoderm). Bars: 200 μm in (A,B); 100 μm in (C,D).

However, all the clonal lines we have examined so far showed either signs of vector integration or persistence of episomal plasmids as evident by the amplification of vector based EBNA by genomic PCR (data not shown). In addition, upon passage, a considerable proportion of the cells routinely failed to form the three dimensional compact colonies evident in mESC and, instead, retained a somewhat loose granular phenotype. We hypothesized that our approach had failed to overcome the methylation barrier needed for complete reprogramming in these loosely clustered cells (Mikkelsen et al., 2008). Accordingly, after the initial reprogramming steps, the colonies were cultured for 2 days in the presence of 5-azacytidine (5-Aza; Sigma; 0.5 μM), a DNA methyl transferase inhibitor that inhibits de novo DNA methylation (Christman, 2002) and that increases the number of SSEA1 positive cells in naïve miPSC (Mikkelsen et al., 2008). Following 5-Aza treatment and in the presence of different combinations of inhibitors listed below for four passages, there was a complete loss of the loose granular cells, a marked improvement in colony morphology to resemble the naïve mESC type (Fig. 3A,B) and relatively high expression of endogenous OCT4 at the mRNA level (Fig. 3D) and overall OCT4 at the protein levels (Fig. 3B). These cells also stained positively for SSEA1 and SSEA4, but not for SSEA3 (data not shown). Other combinations of inhibitors, e.g. KP/CH, KP/CH/PD (3i), and 3i plus A-83-01, an ALK5 inhibitor (4i) were less effective than 2i (PD/CH) (Fig. 3D) in maintaining endogenous OCT4 expression. Accordingly, we now routinely employ 5-Aza along with PD/CH in our reprogramming protocols. Curiously, the lines with the naïve iPSC phenotype contained less than 10 % of OCT4 mRNA noted in a candidate primed ESC line (ID6) (Fig. 3D), which was described in our original publication (Ezashi et al., 2009). Additionally, the colonies are LIF-dependent as evident by the nuclear localization of phosphorylated STAT3 (Fig. 3B) (Davey et al., 2007). Upon LIF withdrawal over two successive passages, the colonies displayed overt signs of differentiation with the loss of compact colony morphology (Fig. 5). The differentiation is much more pronounced with the inclusion of JAK1 inhibitor (1 μM,JAK inhibitor 1,Calbiochem, NJ, USA), which prevents residual phosphorylation of STAT3 via LIFR heterodimer Gp130 (Davey et al., 2007) (Fig. 5). Currently, the ability of these cells to form chimeras is being tested.

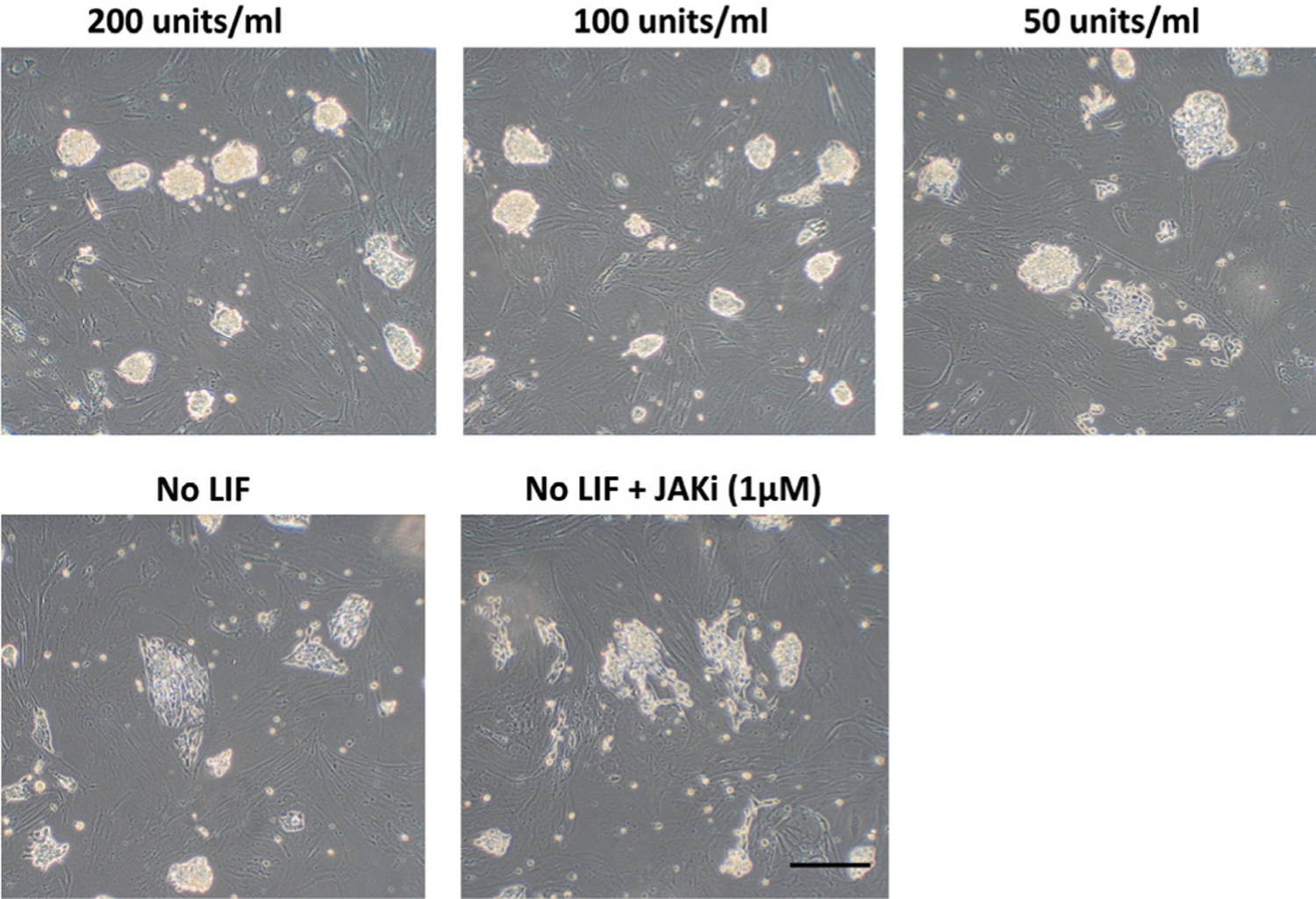

Fig. 5. Dependence of iPSC phenotype on LIF.

Cell line XV was cultured in medium containing three concentrations of hLIF (200, 100 and 50 units/ ml, respectively) and in the total absence of LIF for two passages. Overt signs of differentiation and the loss of compact colony morphology are evident as LIF concentration is reduced, and is more pronounced in the absence of LIF. Since, the LIFR heterodimer Gp130 can signal and support STAT3 activation, through binding of ligands such as IL6, the effect of the JAK1 inhibitor (1 μM) (JAK inhibitor 1, Calbiochem) was also examined. Its presence resulted in a more pronounced differentiation of the iPS cells than that observed in the absence of LIF alone. Bar, 200 μm.

Conclusions

Standard reprogramming approaches with pig embryonic fibroblasts as the targeted starter population give rise to iPSC of the epiblast/primed type, although the dependency of the derived cell lines on FGF2 remains questionable. It also appears clear that, by combining the use of exogenous reprogramming transgenes, overcoming methylation barriers, and culturing the cells with appropriate protein kinase inhibitors, it is possible to generate naïve iPSC. Our use of a plasmid-based approach to reprogram the cells was based on the assumption that we would be able to identify colonies that did not show enduring expression of the reprogramming genes. However, such loss of transgene expression was not observed, suggesting that there was either integration of plasmid DNA into the host genome or persistence of plasmid DNA as an episomal fraction over extended passage. Fortunately, this unintended consequence of nucleofection with the episomal plasmids, may have actually led to a favorable outcome, which might not have been achieved if expression of the transgenes had been short-lived. For example, in the non-permissive mouse strain, (e.g., NOD), (Hanna et al., 2009a), and with human somatic cells (Hanna et al., 2010), it is necessary to maintain upregulated expression of KLF4 either alone or in combination with KLF2/POU5F1 respectively, not only to achieve the naïve state but also to preserve it.

More recently we have resorted to lentiviral vectors containing doxcycline-inducible, floxed polycistronic gene inserts rather than plasmid-based vectors, because of the latter’s relative inefficient reprogramming rate (Okita et al., 2008). Such lentiviral vectors, although integrating, permit stringent control over expression, allow deletion of the genes after reprogramming, and reduce the number of integrations into host cell DNA. Their use, therefore, should assuage some of the concerns associated with the original lentiviral approach. Preliminary experiments indicate that such vectors, in combination with the 2i approach, can be used to produce naïve piPSC relatively efficiently.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Andrei P. Alexenko for support with mouse husbandry and Ms. Sunilima Sinha for immunostaining. Supported by Missouri Life Sciences Board Grant 00022147 to TE and NIH grant HD21896 to RMR.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- EpiSC

epiblast stem cells

- ESC

embryonic stem cells

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cells

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

References

- ALBERIO R, CROXALL N and ALLEGRUCCI C (2010). Pig Epiblast Stem Cells Depend on Activin/Nodal Signaling for Pluripotency and Self Renewal. Stem Cells Dev. 19: 1627–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAO S, TANG F, LI X, HAYASHI K, GILLICH A, LAO K and SURANI MA (2009). Epigenetic reversion of post-implantation epiblast to pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Nature 461: 1292–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREVINI TA, ANTONINI S, CILLO F, CRESTAN M and GANDOLFI F (2007). Porcine embryonic stem cells: Facts, challenges and hopes. Theriogenology 68 Suppl 1: S206–S213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIGGS R and KING TJ (1952). Transplantation of Living Nuclei From Blastula Cells into Enucleated Frogs’ Eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 38: 455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRONS IG, SMITHERS LE, TROTTER MW, RUGG-GUNN P, SUN B, CHUVA DE SOUSA LOPES SM, HOWLETT SK, CLARKSON A, AHRLUND-RICHTER L, PEDERSEN RA et al. (2007). Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448: 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUEHR M, MEEK S, BLAIR K, YANG J, URE J, SILVA J, MCLAY R, HALL J, YING QL and SMITH A (2008). Capture of authentic embryonic stem cells from rat blastocysts. Cell 135: 1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN LR, SHIUE YL, BERTOLINI L, MEDRANO JF, BONDURANT RH and ANDERSON GB (1999). Establishment of pluripotent cell lines from porcine preimplantation embryos. Theriogenology 52: 195–212(18). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTMAN JK (2002). 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene 21: 5483–5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COWAN CA, ATIENZA J, MELTON DA and EGGAN K (2005). Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells after fusion with human embryonic stem cells. Science 309: 1369–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COX JL and RIZZINO A (2010). Induced pluripotent stem cells: what lies beyond the paradigm shift. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 235: 148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAS P, EZASHI T, SCHULZ LC, WESTFALL SD, LIVINGSTON KA and ROBERTS RM (2007). Effects of FGF2 and oxygen in the BMP4-driven differentiation of trophoblast from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Research 1: 61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVEY RE, ONISHI K, MAHDAVI A and ZANDSTRA PW (2007). LIF-mediated control of embryonic stem cell self-renewal emerges due to an autoregulatory loop. FASEB J 21: 2020–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DO JT and SCHOLER HR (2004). Nuclei of embryonic stem cells reprogram somatic cells. Stem Cells 22: 941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DVORAK P, DVORAKOVA D, KOSKOVA S, VODINSKA M, NAJVIRTOVA M, KREKAC D and HAMPL A (2005). Expression and potential role of fibroblast growth factor 2 and its receptors in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 23: 1200–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESTEBAN MA, XU J, YANG J, PENG M, QIN D, LI W, JIANG Z, CHEN J, DENG K, ZHONG M et al. (2009). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from tibetan miniature pig. J Biol Chem 284: 17634–17640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS M (2005). Embryonic stem cells: a perspective. Novartis Found Symp 265: 98–103; discussion 103–106, 122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS MJ and KAUFMAN MH (1981). Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 292: 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS MJ, NOTARIANNI E, LAURIE S and MOOR RM (1990). Derivation and preliminary characterization of pluripotent cell lines from porcine and bovine blastocysts. Theriogenology 33: 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- EZASHI T, DAS P and ROBERTS RM (2005). Low O2 tensions and the prevention of differentiation of hES cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 4783–4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EZASHI T, TELUGU BP, ALEXENKO AP, SACHDEV S, SINHA S and ROBERTS RM (2009). Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from pig somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10993–10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLECHON JE, DEGROUARD J and FLECHON B (2004). Gastrulation events in the prestreak pig embryo: ultrastructure and cell markers. Genesis 38: 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREBER B, WU G, BERNEMANN C, JOO JY, HAN DW, KO K, TAPIA N, SABOUR D, STERNECKERT J, TESAR P et al. (2010). Conserved and divergent roles of FGF signaling in mouse epiblast stem cells and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6: 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURDON JB, MOHUN TJ, FAIRMAN S and BRENNAN S (1985). All components required for the eventual activation of muscle-specific actin genes are localized in the subequatorial region of an uncleaved amphibian egg. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL J, GUO G, WRAY J, EYRES I, NICHOLS J, GROTEWOLD L, MORFOPOULOU S, HUMPHREYS P, MANSFIELD W, WALKER R et al. (2009). Oct4 and LIF/Stat3 additively induce Kruppel factors to sustain embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 5: 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL V (2008). Porcine embryonic stem cells: a possible source for cell replacement therapy. Stem Cell Rev 4: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNA J, CHENG AW, SAHA K, KIM J, LENGNER CJ, SOLDNER F, CASSADY JP, MUFFAT J, CAREY BW and JAENISCH R (2010). Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 9222–9227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNA J, MARKOULAKI S, MITALIPOVA M, CHENG AW, CASSADY JP, STAERK J, CAREY BW, LENGNER CJ, FOREMAN R, LOVE J et al. (2009a). Metastable pluripotent states in NOD-mouse-derived ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 4: 513–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNA J, SAHA K, PANDO B, VAN ZON J, LENGNER CJ, CREYGHTON MP, VAN OUDENAARDEN A and JAENISCH R (2009b). Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature 462: 595–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENDERSON JK, DRAPER JS, BAILLIE HS, FISHEL S, THOMSON JA, MOORE H and ANDREWS PW (2002). Preimplantation human embryos and embryonic stem cells show comparable expression of stage-specific embryonic antigens. Stem Cells 20: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANGFU D, OSAFUNE K, MAEHR R, GUO W, EIJKELENBOOM A, CHEN S, MUHLESTEIN W and MELTON DA (2008). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Biotechnol 26: 1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEEFER CL, PANT D, BLOMBERG L and TALBOT NC (2007). Challenges and prospects for the establishment of embryonic stem cell lines of domesticated ungulates. Anim Reprod Sci 98: 147–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISKINIS E and EGGAN K (2010). Progress toward the clinical application of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest 120: 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI P, TONG C, MEHRIAN-SHAI R, JIA L, WU N, YAN Y, MAXSON RE, SCHULZE EN, SONG H, HSIEH CL et al. (2008). Germline competent embryonic stem cells derived from rat blastocysts. Cell 135: 1299–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI W, WEI W, ZHU S, ZHU J, SHI Y, LIN T, HAO E, HAYEK A, DENG H and DING S (2009). Generation of rat and human induced pluripotent stem cells by combining genetic reprogramming and chemical inhibitors. Cell Stem Cell 4: 16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY WE, RICHTER L, YACHECHKO R, PYLE AD, TCHIEU J, SRIDHARAN R, CLARK AT and PLATH K (2008). Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 2883–2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYSSIOTIS CA, FOREMAN RK, STAERK J, GARCIA M, MATHUR D, MARKOULAKI S, HANNA J, LAIRSON LL, CHARETTE BD, BOUCHEZ LC et al. (2009). Reprogramming of murine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells with chemical complementation of Klf4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 8912–8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSON A, FOREMAN R, CHEVALIER B, BILODEAU S, KAHN M, YOUNG RA and JAENISCH R (2008). Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 3: 132–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN GR (1981). Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78: 7634–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIKKELSEN TS, HANNA J, ZHANG X, KU M, WERNIG M, SCHORDERET P, BERNSTEIN BE, JAENISCH R, LANDER ES and MEISSNER A (2008). Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature 454: 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLS J and SMITH A (2009). Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell 4: 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIWA H, TOYOOKA Y, SHIMOSATO D, STRUMPF D, TAKAHASHI K, YAGI R and ROSSANT J (2005). Interaction between Oct3/4 and Cdx2 determines trophectoderm differentiation. Cell 123: 917–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOTARIANNI E, GALLI C, LAURIE S, MOOR RM and EVANS MJ (1991). Derivation of pluripotent, embryonic cell lines from the pig and sheep. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 43: 255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOTARIANNI E, LAURIE S, MOOR RM and EVANS MJ (1990). Maintenance and differentiation in culture of pluripotential embryonic cell lines from pig blastocysts. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 41: 51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ODORICO JS, KAUFMAN DS and THOMSON JA (2001). Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells 19: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKITA K, NAKAGAWA M, HYENJONG H, ICHISAKA T and YAMANAKA S (2008). Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science 322: 949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK I-H, ZHAO R, WEST JA, YABUUCHI A, HUO H, INCE TA, LEROU PH, LENSCH MW and DALEY GQ (2008a). Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK IH, ARORA N, HUO H, MAHERALI N, AHFELDT T, SHIMAMURA A, LENSCH MW, COWAN C, HOCHEDLINGER K and DALEY GQ (2008b). Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 134: 877–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIEDRAHITA JA, ANDERSON GB and BONDURANT RH (1990). On the isolation of embryonic stem cells: Comparative behavior of murine, porcine and ovine embryos. Theriogenology 34: 879–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS RM, SMITH GW, BAZER FW, CIBELLI J, SEIDEL GE JR., BAUMAN DE, REYNOLDS LP and IRELAND JJ (2009a). Research priorities. Farm animal research in crisis. Science 324: 468–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS RM, TELUGU BP and EZASHI T (2009b). Induced pluripotent stem cells from swine (Sus scrofa): why they may prove to be important. Cell Cycle 8: 3078–3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAO L and WU WS (2010). Gene-delivery systems for iPS cell generation. Expert Opin Biol Ther 10: 231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILVA SS, ROWNTREE RK, MEKHOUBAD S and LEE JT (2008). X-chromosome inactivation and epigenetic fluidity in human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4820–4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRIDHARAN R, TCHIEU J, MASON MJ, YACHECHKO R, KUOY E, HORVATH S, ZHOU Q and PLATH K (2009). Role of the murine reprogramming factors in the induction of pluripotency. Cell 136: 364–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADA M, TAKAHAMA Y, ABE K, NAKATSUJI N and TADA T (2001). Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol 11: 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI K, TANABE K, OHNUKI M, NARITA M, ICHISAKA T, TOMODA K and YAMANAKA S (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKAHASHI K and YAMANAKA S (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALBOT NC and BLOMBERG LE A (2008). The pursuit of ES cell lines of domesticated ungulates. Stem Cell Rev 4: 235–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TELUGU BP, EZASHI T and ROBERTS RM (2010). The promise of stem cell research in pigs and other ungulate species. Stem Cell Rev 6: 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TESAR PJ, CHENOWETH JG, BROOK FA, DAVIES TJ, EVANS EP, MACK DL, GARDNER RL and MCKAY RD (2007). New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature 448: 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMSON JA, ITSKOVITZ-ELDOR J, SHAPIRO SS, WAKNITZ MA, SWIERGIEL JJ, MARSHALL VS and JONES JM (1998). Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282: 1145–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMSON JA, KALISHMAN J, GOLOS TG, DURNING M, HARRIS CP and HEARN JP (1996). Pluripotent cell lines derived from common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) blastocysts. Biol Reprod 55: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VACKOVA I, UNGROVA A and LOPES F (2007). Putative embryonic stem cell lines from pig embryos. J Reprod Dev 53: 1137–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST FD, TERLOUW SL, KWON DJ, MUMAW JL, DHARA SK, HASNEEN K, DOBRINSKY JR and STICE SL (2010). Porcine Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Produce Chimeric Offspring. Stem Cells Dev 19: 1211–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESTFALL SD, SACHDEV S, DAS P, HEARNE LB, HANNINK M, ROBERTS RM and EZASHI T (2008). Identification of Oxygen-Sensitive Transcriptional Programs in Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev 17: 869–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILMUT I, SCHNIEKE AE, MCWHIR J, KIND AJ and CAMPBELL KH (1997). Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 385: 810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOBUS AM and BOHELER KR (2005). Embryonic stem cells: prospects for developmental biology and cell therapy. Physiol Rev 85: 635–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU Z, CHEN J, REN J, BAO L, LIAO J, CUI C, RAO L, LI H, GU Y, DAI H et al. (2009). Generation of pig induced pluripotent stem cells with a drug-inducible system. J Mol Cell Biol 1: 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU RH, CHEN X, LI DS, LI R, ADDICKS GC, GLENNON C, ZWAKA TP and THOMSON JA (2002). BMP4 initiates human embryonic stem cell differentiation to trophoblast. Nat Biotechnol 20: 1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU RH, PECK RM, LI DS, FENG X, LUDWIG T and THOMSON JA (2005). Basic FGF and suppression of BMP signaling sustain undifferentiated proliferation of human ES cells. Nat Methods 2: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU Y, ZHU X, HAHM HS, WEI W, HAO E, HAYEK A and DING S (2010). Revealing a core signaling regulatory mechanism for pluripotent stem cell survival and self-renewal by small molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8129–8134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YING QL, NICHOLS J, CHAMBERS I and SMITH A (2003). BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell 115: 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU J, HU K, SMUGA-OTTO K, TIAN S, STEWART R, SLUKVIN II and THOMSON JA (2009). Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science 324: 797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YU J, VODYANIK MA, SMUGA-OTTO K, ANTOSIEWICZ-BOURGET J, FRANE JL, TIAN S, NIE J, JONSDOTTIR GA, RUOTTI V, STEWART R et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318: 1917–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]