Abstract

BMS-232632 is an azapeptide human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitor that displays potent anti-HIV-1 activity (50% effective concentration [EC50], 2.6 to 5.3 nM; EC90, 9 to 15 nM). In vitro passage of HIV-1 RF in the presence of inhibitors showed that BMS-232632 selected for resistant variants more slowly than nelfinavir or ritonavir did. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of three different HIV strains resistant to BMS-232632 indicated that an N88S substitution in the viral protease appeared first during the selection process in two of the three strains. An I84V change appeared to be an important substitution in the third strain used. Mutations were also observed at the protease cleavage sites following drug selection. The evolution to resistance seemed distinct for each of the three strains used, suggesting multiple pathways to resistance and the importance of the viral genetic background. A cross-resistance study involving five other protease inhibitors indicated that BMS-232632-resistant virus remained sensitive to saquinavir, while it showed various levels (0.1- to 71-fold decrease in sensitivity)-of cross-resistance to nelfinavir, indinavir, ritonavir, and amprenavir. In reciprocal experiments, the BMS-232632 susceptibility of HIV-1 variants selected in the presence of each of the other HIV-1 protease inhibitors showed that the nelfinavir-, saquinavir-, and amprenavir-resistant strains of HIV-1 remained sensitive to BMS-232632, while indinavir- and ritonavir-resistant viruses displayed six- to ninefold changes in BMS-232632 sensitivity. Taken together, our data suggest that BMS-232632 may be a valuable protease inhibitor for use in combination therapy.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) protease (Prt) specifically processes gag and gag-pol polyproteins into structural proteins (MA [p17], CA [p24], NC [p7], and p6) and viral replication enzymes (reverse transcriptase [RT], integrase, and Prt) (18). The Prt functions at the late stages of viral replication during virion maturation and has proved to be an effective target for antiviral intervention. Currently, five peptidic Prt inhibitors, saquinavir (SQV), indinavir (IDV), ritonavir (RTV), nelfinavir (NFV), and amprenavir (APV), are approved for clinical use (7, 19, 30, 32, 41). This class of drugs suppresses viral replication to a greater extent than the RT inhibitors in HIV-1-infected patients (12, 13, 24, 25, 27, 28, 42). Today, the standard care for AIDS patients involves the use of two RT inhibitors and one Prt inhibitor to reduce viremia to unquantifiable levels for an extended period of time (2, 13, 14, 27, 29; M. Markowitz, Y. Cao, A. Hurley, R. Schluger, S. Monard, R. Kost, B. Kerr, R. Anderson, S. Eastman, and D. D. Ho, 5th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infections, abstr. 371, 1998). Despite such a remarkable result, 30 to 50% of patients ultimately fail therapy, presumably due to patient nonadherence to drug schedules (as a consequence of inconvenient dosing and side effects) (43), insufficient drug exposure, and resistance development. Therefore, additional Prt inhibitors that display greater potency, improved bioavailability, fewer side effects, and distinct resistance profiles are needed.

The emergence of resistant variants results from the large number of genetically diverse viruses generated in infected individuals and the subsequent selection of resistant strains in the presence of antiviral drugs. The current group of Prt inhibitors select for distinct but overlapping sets of amino acid substitutions within the Prt molecule. The key signature substitutions for IDV and RTV resistance reside at amino acid residues V82, I84, or L90, those for SQV resistance reside at G48, I84, or L90, those for NFV resistance reside at D30 or L90, and those for APV resistance reside at I50 or I84 (1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 15, 16, 22, 23, 26, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38; M. Tisdale, R. E. Myers, M. Al T-Khaled, and W. Snowden, 6th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infections, abstr. 118, 1999). In addition to these major substitutions, all five Prt inhibitors have been shown to select for additional overlapping sets of amino acid substitutions elsewhere in the enzyme. These sites include L10, M46, L63, A71, and N88 (37, 40, 42). The overlapping sets of resistance substitutions are clearly responsible for certain patterns of cross-resistance among the currently approved Prt inhibitors. More recently, amino acid substitutions located at several of the Prt cleavage sites were also described in association with the emergence of HIV-1 strains resistant to Prt inhibitors (3, 8, 9, 21, 45). These cleavage-site (P7, P1, and P6) mutations are believed to improve the cleavage efficiency of resistant Prts, compensating for any reduced catalytic efficiency of the altered enzyme.

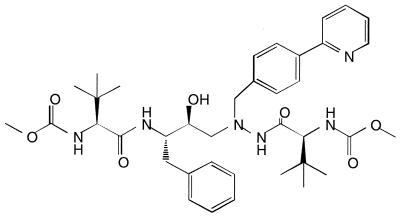

BMS-232632 is a novel azapeptide inhibitor (Fig. 1) of HIV-1 Prt currently under evaluation in clinical trials. The compound is highly selective and is an effective inhibitor of HIV-1 Prt (Ki, 2.7 nM). It also displays potent anti HIV-1 activity (90% effective concentration [EC90], 9 to 15 nM) against a variety of HIV isolates when different cell types are tested (B. S. Robinson, K. Riccardi, Y. F. Gong, K. Guo, D. Stock, C. Deminie, F. Djang, R. Colonno, and P. F. Lin, in press). Comparative anti-HIV studies showed that BMS-232632 is generally more potent than the five currently approved HIV-1 Prt inhibitors, even in the presence of human serum proteins (Robinson et al., in press). Furthermore, phase I studies have indicated that the compound has favorable bioavailability in humans and the potential for once-daily dosing (E. M. O'Mara, J. Smith, S. J. Olsen, T. Tanner, A. E. Schuster, and S. Kaul, 6th Conf. Retroviruses Opportunistic Infections, abstr. 604, 1999). In the current study, we describe the selection and characterization of BMS-232632-resistant variants in culture by using three different HIV-1 strains and the results of reciprocal cross-resistance studies with the five available Prt inhibitors.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of BMS-232632.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

MT-2 cells, HIV-1 RF, HIV-1 BRU, and the HIV-1 NL4-3 proviral clone were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institutes of Health. Clinical isolate 006 was described previously (20). NL4-3 viruses were generated by transfecting the proviral DNA into HEK 293 cells by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Promega). All HIV strains were amplified in MT-2 cells and titrated in the same cells by a virus yield assay (17). The IDV-resistant clinical isolate (patient A) (4) was provided by E. Emini of Merck. All clinical isolates were expanded in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and their Prt genes were sequenced.

Chemicals.

BMS-232632 (previously referred to as CGP73547), SQV, IDV, NFV, RTV, and APV were prepared at Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Drug susceptibility assay and cytotoxicity assay.

MT-2 cells were infected with wild-type and mutant HIV-1 strains at a multiplicity of infection of 0.005, followed by incubation in the presence of serially diluted inhibitors for 4 to 5 days. Virus yields were quantitated by an RT assay (34). The results from at least two experiments were used to calculate the EC50s. In our drug sensitivity assays, we used statistical testing by an unpaired t test in which we compared the EC50s for resistant and wild-type viruses to demonstrate that our data are statistically significant. By convention, virus was considered to have meaningful resistance when drug susceptibility levels increased over fourfold (4, 5, 33). For the cytotoxicity assay, host cells were incubated with serially diluted inhibitors for 6 days, and cell viability was quantitated by an XTT assay (44).

Selection of drug-resistant mutants.

HIV-1 variants resistant to Prt inhibitors were selected as described previously (31, 35). Briefly, HIV-1 RF was initially treated with various Prt inhibitors (BMS-232632, IDV, RTV, NFV, and APV) at a concentration two times the respective EC50 of each inhibitor and was then passaged in the presence of increasing concentrations of each compound. The infected cell pellets were periodically harvested for DNA sequence analysis, and the secreted viruses in the supernatant were collected for drug susceptibility assays. NL4-3 and BRU viruses resistant to BMS-232632 were selected by the same procedure.

In these drug selection experiments, the virus in the supernatant was inoculated into fresh MT-2 cells during each passage; therefore, the sequence of proviral DNA in the infected cell pellets should resemble that of the secreted virus. However, errors are introduced into DNA after reverse transcription, and the genotypic data derived from proviral DNA may slightly vary from those for the free virions.

Genotypic analysis of Prt mutations.

The Prt genes were amplified by PCR from infected cell pellets and were cloned into pBluescriptII KS(+) as described previously (31). The cloned Prt genes were sequenced with an ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit and were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 377 automated DNA sequencer. The abbreviations for the amino acids are as follows: A, alanine; I, isoleucine; L, leucine; M, methionine; P, proline; S, serine; V, valine; and Y, tyrosine.

RESULTS

BMS-232632 susceptibilities of HIV-1 strains resistant to current Prt inhibitors.

Because of the urgent need to identify new inhibitors effective against resistant strains, we first determined whether viral strains resistant to the five currently approved Prt inhibitors that we generated in vitro remained sensitive to BMS-232632. Assay results along with the mutational makeup of each isolate tested are summarized in Table 1. Sequence analysis of the HIV-1 RF variants selected in cell culture by IDV, NFV, and RTV revealed that the Prt substitutions present were mostly representative of those identified in clinical trials (1, 4, 5, 6, 26, 33, 38). However, the resistant RF strain selected with APV contained only the mutation V82I and not the signature substitution at amino acid residue 50 (30; Tisdale et al., 6th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infections).

TABLE 1.

Cross-resistance profile of HIV isolates resistant to Prt inhibitors

| Virus strain-selection drug (concn [μM]) | Major Prt mutations | Mean ± SEMa EC50 (nM) (fold decrease in sensitivity)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS-232632 | NFV | IDV | RTV | SQV | APV | ||

| RF | Wild type | 5.72 ± 1.00 | 44.6 ± 2.0 | 27.8 ± 5.8 | 95.5 ± 10.4 | 15.5 ± 0.8 | 81.9 ± 3.0 |

| RF-IDV (4.0) | V32I, M46I, V82F, I84V | 49.6 ± 17.5 (9)a | 374 ± 99 (8)a | 678 ± 168 (24)a | 6,833 ± 699 (72)a | 21.4 ± 5.6 (1) | 2,218 ± 286 (27)a |

| Clinicalb-IDV | Pretreatment | 10.7 ± 2.2 | 94.5 ± 14.9 | 24.0 ± 3.5 | 280 ± 23 | 76.0 ± 2.3 | 98.9 ± 16.3 |

| Clinicalb-IDV (posttreatment) | V10R, M46I, L63P, V82T, I84V | 62.9 ± 13.2 (6)a | 557 ± 96 (6)a | 350 ± 77 (15)a | 5,763 ± 898 (21)a | 482 ± 62 (6)a | 391 ± 71 (4)a |

| RF | Wild type | 5.72 ± 1.00 | 44.6 ± 2.0 | 27.8 ± 5.8 | 95.5 ± 10.4 | 15.5 ± 0.8 | 81.9 ± 3.0 |

| RF-RTV (5.0) | M46I, V82F, I84V, L90M | 38.0 ± 11.8 (7)a | 971 ± 508 (22)a | 801 ± 321 (29)a | 6,800 ± 270 (71)a | 123 ± 15 (8)a | 2,311 ± 837 (28)a |

| RF | Wild type | 0.73 ± 0.11 | 10.9 ± 0.7 | 5.81 ± 0.06 | 32.7 ± 1.5 | 5.96 ± 0.14 | 24.2 ± 2.5 |

| RF-APV (5.0) | V32I, M46I, I47V, V82I | 1.85 ± 0.71 (2) | 119 ± 1 (11)a | 63.3 ± 8.2 (11)a | 516 ± 17 (16)a | 5.65 ± 1.03 (1) | 1,984 ± 236 (82)a |

| RF | Wild type | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 34.6 ± 11.7 | 98.5 ± 6.1 | 11.3 ± 2.3 | 54.0 ± 21.7 |

| RF-NFV (2.0) | D30N, M46I | 9.7 ± 2.4 (3)a | 315 ± 6 (35)a | 101 ± 34.9 (3) | 90.5 ± 1.8 (1) | 6.5 ± 0.4 (1) | 113 ± 35.9 (2) |

| NL | Wild type | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 28.6 ± 6.5 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 24.6 ± 5.9 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 48.9 ± 7.7 |

| NLc-SQV | L10I, G48V, L90M | 0.95 ± 0.35 (1) | 44.2 ± 2.6 (2) | 10.3 ± 4.5 (3) | 54.7 ± 6.9 (2) | 35.7 ± 6.1 (8)a | 80.5 ± 9.2 (2) |

Fold decrease in sensitivity was found to be significant at the ≤0.05 level by an unpaired t test. Results were derived from four experiments each for IDV (4.0 μM) with RF, IDV with a clinical isolate, and NFV (2.0 μM) with RF and from two experiments each for SQV with NL4-3 and APV (5.0 μM) with RF.

Clinical isolate obtained from Merck.

Recombinant virus in the NL4-3 background.

The summary results in Table 1 showed that both the clinical and laboratory IDV-resistant isolates (15- and 24-fold decreases in sensitivity to IDV, respectively) displayed 6- to 9-fold resistance to BMS-232632, NFV, and SQV. In contrast, cross-resistance was observed between IDV and RTV (21- to 72-fold decrease in sensitivity) as well as between IDV and APV (4- to 27-fold). The RTV-resistant virus (71-fold decreased sensitivity to RTV) showed only moderate resistance to BMS-232632 (7-fold) and SQV (8-fold) and high-level cross-resistance to IDV (29-fold), NFV (22-fold), and APV (28-fold). The highly APV-resistant (82-fold decrease in sensitivity) HIV-1 RF strain containing the V82I mutation remained sensitive to BMS-232632. Finally, both NFV-resistant (35-fold decrease in sensitivity) and SQV-resistant (8-fold decrease in sensitivity) viruses maintained sensitivity to all of the other Prt inhibitors studied, including BMS-232632. These results suggest that some susceptibility to BMS-232632 may still be retained by those virus isolates already showing low to moderate levels of resistance to other Prt inhibitors.

Isolation of BMS-232632-resistant variants.

To further understand the low levels of cross-resistance observed as described above, BMS-232632-resistant variants were isolated in order to perform reciprocal cross-resistance evaluations. To better mimic the sequence diversity found in the heterogeneous population of clinical viruses, we studied the emergence of resistance in multiple viral strains. Three HIV-1 strains (strains RF, BRU, and NL4-3) were passaged in MT-2 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of BMS-232632. Highly cytopathic strain RF was chosen because of the ease of detection of breakthrough viruses, while the BRU and NL4-3 viruses were used because recombinant proviral clones were available for in vitro mutagenesis studies. Breakthrough virus was first detected by observation of a virus-induced cytopathic effect, and its presence was subsequently confirmed by drug sensitivity analysis.

The RF strain of HIV-1 showed a 6-fold decrease in sensitivity to BMS-232632 following 2.4 months of passage in the presence of concentrations up to 100 nM (>26-fold the EC50) (Table 2). Continued passage of the breakthrough virus in increasing concentrations of BMS-232632 up to 500 nM over the course of 4.8 months gave rise to virus that exhibited a very high level of resistance (183-fold decrease in sensitivity). In contrast, a similar selection strategy with NFV resulted in RF virus that exhibited 9-fold decrease in sensitivity to NFV after only 1 month of selection and 35-fold decrease in sensitivity after 2 months of drug treatment (data not shown). Parallel studies also showed that HIV-1 RF became 71-fold less sensitive to RTV after approximately 3 months of drug selection. This qualitative comparison suggests that in vitro viral resistance to BMS-232632 develops less rapidly than resistance to NFV or RTV for the RF strain.

TABLE 2.

Generation and drug sensitivity of BMS-232632-resistant viruses

| Virus strain | Selection

|

Major Prt substitutions | Mean ± SEM EC50 (nM) (fold decrease in sensitivity) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period (mo) | Drug concn (nM) | |||

| RF | 0 | 0 | 3.80 ± 0.31 | |

| 1 | 25 | N88S | 17.1 ± 2.1 (4)a | |

| 2.4 | 100 | N88S, M46I | 23.0 ± 5.7 (6)a | |

| 3.5 | 225 | N88S, M46I, A71V, V32I | 46.7 ± 8.5 (12)a | |

| 4.8 | 500 | N88S, M46I, A71V, V32I, I84V, L33F | 697 ± 25 (183)ab | |

| BRU | 0 | 0 | 2.75 ± 0.27 | |

| 2.6 | 28 | N88S, A71V, I50L, L10Y/F | 99.5 ± 8.4 (36)a | |

| 4.7 | 500 | N88S, A71V, I50L, L10Y/F, L63P | 256 ± 17 (93)ab | |

| NL4-3 | 0 | 0 | 1.58 ± 0.18 | |

| 3.9 | 40 | I84V, M46I V32I | 9.66 ± 1.17 (6)a | |

| 4.6 | 200 | I84V, M46I, V32I, L89M | 152 ± 28 (96)ab | |

Fold decrease in sensitivity was found to be significant at the ≤0.05 level by using an unpaired t test. Results were derived from more than nine experiments for RF and four to five experiments for BRU and NL4-3, respectively.

The infectivities of these highly resistant variants appear to be normal.

In contrast to the RF strain of HIV-1, the BRU and NL4-3 strains of HIV-1 did not replicate to appreciable levels in the presence of BMS-232632 and exhibited no apparent virus-induced cytopathic effect following nearly 2 months of treatment. However, viral variants did appear with prolonged drug selection. The breakthrough BRU viruses that emerged at 2.6 and 4.7 months displayed 36- and 93-fold decreases in sensitivity, to BMS-232632, respectively (Table 2). Only strain NL4-3 showed a 6-fold reduction in susceptibility after 3.9 months of selection, but eventually had a 96-fold reduction in susceptibility compared to the susceptibility of unpassaged virus after 4.6 months of treatment. In this one experiment, it seemed that the rate of resistance development varied for each of the three viral strains used.

Genotypic analysis of selected viruses.

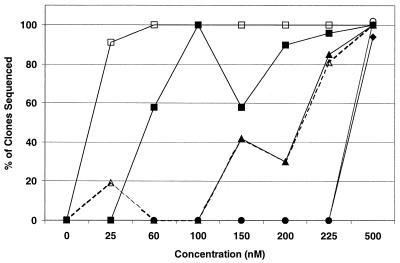

To better understand the genetic evolution that leads to BMS-232632 resistance, changes in the HIV Prt gene during drug selection were monitored by gene cloning and DNA sequencing. Figure 2 summarizes the ordered accumulation of individual amino acid substitutions within the Prt observed in HIV-1 RF populations with increasing drug concentrations. The N88S mutation emerged at 25 nM, followed by the M46I substitution at 60 nM, the A71V and V32I substitutions at 150 nM, and finally, the L33F and I84V changes at 500 nM. The appearance of an L23I substitution was observed at 200 nM, but it never occurred in more than 20% of the clones sequenced (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Appearance of amino acid substitutions in HIV-1 RF. Eleven to 32 Prt clones were sequenced for each of the provirus populations treated with BMS-232632 at 0, 25, 60, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 500 nM as described in Materials and Methods. Lines represent the percentage of sequenced clones containing N88S (□), M46I (■), A71V (▵), V32I (▴), L33F (⧫) or I84V (○) amino acid substitutions independent of whether multiple changes occurred within a given clone.

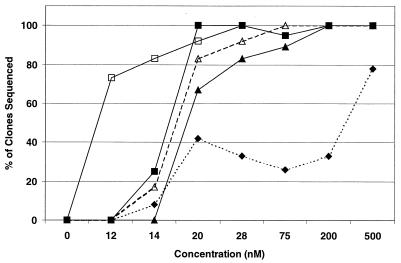

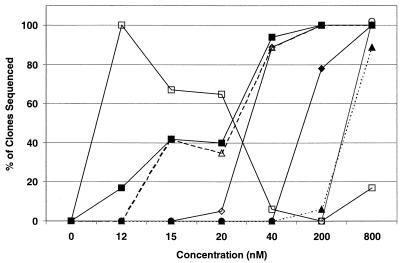

With the BRU strain (Fig. 3), the order of mutations that emerged was quite different from that observed with the RF strain. The N88S substitution also appeared first, but was followed instead by I50L, L10Y or L10F, A71V, and L63P, which appeared in over 40% of the clones at 20 nM. A V77I substitution was observed early, but it never occurred in more than 10% of the clones sequenced. The M46I substitution first appeared at 200 nM and occurred in 28% of the sequenced clones at 500 nM (data not shown). Passage of HIV-1 NL4-3 in the presence of BMS-232632 yielded yet another pattern of substitutions (Fig. 4). Unlike the RF and BRU strains, the N88S substitution was not selected at all during passage. Instead, the first substitution to appear was L23I at 12 nM, which subsequently disappeared with continued passage. Loss of L23I coincided with the appearance of M46I and I84V substitutions, both commonly associated with resistance to Prt inhibitors. V32I was the next change to appear at 40 nM, followed by L89M at 200 nM, and then A71V and L10Y at 800 nM.

FIG. 3.

Appearance of amino acid substitutions in HIV-1 BRU. Twelve to 28 Prt clones were sequenced for each of the provirus populations treated with BMS-232632 at 0, 10, 14, 20, 28, 75, 200, and 500 nM as described in Materials and Methods. Lines represent the percentage of sequenced clones containing N88S (□), I50L (■), L10Y/F (▵), A71V (▴), or L63P (⧫) amino acid substitutions independent of whether multiple changes occurred within a given clone.

FIG. 4.

Appearance of amino acid substitutions in HIV-1 NL4-3. Twelve to 32 Prt clones were sequenced for each of the provirus populations treated with BMS-232632 at 0, 10, 12, 15, 20, 40 and 200 nM as described in Materials and Methods. Lines represent the percentage of sequenced clones containing L23I (□), M46I/L (■), I84V (▵), V32I (◊), M89L (⧫), A71V (▴), or L10Y (○) amino acid substitutions independent of whether multiple changes occurred within a given clone.

Since we have not attempted to reproduce the results of this experiment due to the significant amount of work involved, we do not know whether the specific sequence of mutations that accumulated will be the same each time. We can conclude from these results only that there are several mutational pathways by which HIV-1 can become resistant to BMS-232632. Although the ordered accumulation of resistance mutations observed could result from chance events, it is more likely that the substitution patterns observed in each of the strains used resulted from the differences in genetic background (35).

The absence of the N88S substitution in strain NL4-3 was surprising, since it was the first to appear in the other two strains. To determine if the N88S substitution has a deleterious effect when introduced into the NL4-3 genetic background, a recombinant NL4-3 clone with this amino acid change was constructed, and the resulting virus was characterized in regard to phenotypic resistance to BMS-232632 and other Prt inhibitors. The results showed that a viable NL4-3 variant containing the N88S substitution could be generated and that this variant remained sensitive (less than a twofold change in resistance) to the five approved Prt inhibitors and BMS-232632 (data not shown). This was in contrast to a fourfold decrease in sensitivity to BMS-232632 observed with the RF strain that contained only the N88S mutation (Table 2). Therefore, the presence of the N88S substitution alone in strain NL4-3 may not provide a sufficient selective advantage for it to be readily selected.

A series of additional NL4-3 recombinant viruses were prepared to further understand the amino acid substitutions with the greatest impact on resistance development. The L89M substitution that appeared in resistant NL4-3 virus upon extended passage was examined because it appeared to cause a dramatic increase (6- to 96-fold) in BMS-232632 resistance levels when it was combined with V32I, M46I, and I84V (Table 2). The results indicate that this amino acid change alone has no significant effect on BMS-232632 resistance, since a recombinant NL4-3 virus that contains only the L89M substitution remained sensitive to BMS-232632 (data not shown).

Emergence of Prt cleavage-site mutations.

Several recent reports have indicated that changes in the Prt cleavage sites occurred during treatment with HIV Prt inhibitors (3, 8, 9, 21, 45). To understand whether similar mutations at the P7-P1 and P1-P6 cleavage sites developed in conjunction with the changes in the Prt noted above, we examined the gag sequence that spans the P7-P1-P6 junctions from clones obtained during passage of all three virus strains. The cleavage-site sequences and fractions of clones that contained the changes are summarized in Table 3. One BMS-232632-induced change was found at the P1-P6 site (F/LQSRP to F/LQSRL) in the highly resistant RF virus. Seven of 11 RF clones that showed a 12-fold decrease in sensitivity to BMS-232632 and all 12 RF clones that displayed a 183-fold decrease in sensitivity to BMS-232632 contained the specific P1-P6 change. Most notably, the BRU viruses with a 36- or 93-fold decrease in sensitivity carried a 12-amino-acid deletion near the P1-P6 site. Since none of the aforementioned BMS-232632-associated substitutions were associated with specific Prt gene substitutions or were found with any consistency among the three HIV strains studied, their significance remains to be determined. The typical P7-P1 change associated with IDV or RTV resistance (AN/F to VN/F) (21, 45) was observed in only 1 of the 22 selected BRU virus clones sequenced. The common substitution at the P1-P6 site (F/L to F/F) that correlated with ABT-378 or BILA-906BS treatment (3, 8, 9) was also seen only at a low frequency (2 of 12) in NL4-3 virus selected with high doses of BMS-232632.

TABLE 3.

Characterization of Prt cleavage site mutations in BMS-232632-resistant variants

| Virus strain | Selection concn (nM) | Fold decrease in sensitivity | Cleavage site sequence | Fraction of clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P7/P1 P1/P6 | ||||

| ↓↓ | ||||

| RF | 0 | EGRQAN FLGKIWPSHKGRPGNF LQSRPE | ||

| 100 | 6 | ------ -------------R-- ------ | 1/12 | |

| 225 | 12 | ------ -S-------------- ------ | 1/11 | |

| ------ ---------------- ----L- | 7/11 | |||

| 500 | 183 | ------ ---------------- ----L- | 11/12 | |

| ------ -------------E-- ----L- | 1/12 | |||

| P7/P1 P1/P6 | ||||

| ↓↓ | ||||

| BRU | 0 | TERQAN FLGKIWPSYKGRPGNF LQSRPEPTAPPFLQSRPEPTAPPEES | ||

| 28 | 36 | ------ ---------------- ----------- --- | 12/12 | |

| 500 | 93 | ------ ----S----------- ----------- --- | 1/10 | |

| ----V- ---------------- ----------- --- | 1/10 | |||

| ------ ----T----------- ----------- --- | 1/10 | |||

| ------ S--------------- ----------- --- | 1/10 | |||

| ------ ----T----------- ----------- --- | 1/10 | |||

| P7/P1 P1/P6 | ||||

| ↓↓ | ||||

| NL4-3 | 0 | TERQAN FLGKIWPSHKGRPGNF LQSRPE | ||

| 40 | 6 | N----- ---------------- ------ | 1/12 | |

| 200 | 96 | N----- ---------------- ------ | 1/12 | |

| ------ ---------------- F----- | 1/12 | |||

| N----- ---------------- F----- | 1/12 |

Cross-resistance studies with the selected BMS-232632-resistant viruses.

To complete the reciprocal cross-resistance studies mentioned above, the reference strain and two resistant isolates of each of the three HIV-1 strains were tested for their sensitivities to the five currently approved Prt inhibitors (Table 4). In each case, we tried to use variants that displayed either low or high levels of BMS-232632 resistance. The HIV-1 RF strain that is resistant (12-fold) to BMS-232632 and that contains the Prt substitutions V32I, M46I, A71V, and N88S showed a comparable decrease in sensitivity to NFV (12-fold), while no reductions in sensitivity to IDV, RTV, SQV, or APV were noted. Importantly, the highly resistant RF strain (183-fold decrease in sensitivity) still retained SQV sensitivity, although it exhibited increased levels of resistance to NFV (21-fold), IDV (36-fold), RTV (54-fold), and APV (9-fold). Such a broad increase in cross-resistance most likely resulted from the accumulation of additional Prt substitutions (L33F and I84V). In fact, these results are not surprising because the I84V substitution has been implicated in the resistance to various HIV-1 Prt inhibitors (37).

TABLE 4.

Cross-resistance profile of BMS-232632-resistant viruses to currently approved Prt inhibitors

| Virus strain (selection concn [μM]) | Major Prt substitutions | Mean ± SEM EC50 (nM) (fold decrease in sensitivity)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS-232632 | NFV | IDV | RTV | SQV | APV | ||

| RF (0) | Wild type | 3.80 ± 0.31 | 28.7 ± 2.6 | 14.8 ± 1.8 | 77.6 ± 8.9 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 58.2 ± 7.2 |

| RF (0.23) | V32I, M46I, A71V, N88S | 46.7 ± 8.5 (12)a | 332 ± 27 (12)a | 56.7 ± 13.2 (4)a | 202 ± 22 (3)a | 21.4 ± 3.3 (2)a | 22.5 ± 5.1 (0.4)a |

| RF (0.50) | V32I, L33F, M46I, A71V, I84V, N88S | 697 ± 25 (183)a | 610 ± 31 (21)a | 539 ± 38 (36)a | 4224 ± 1127 (54)a | 33.0 ± 0.9 (2)a | 500 ± 4 (9)a |

| NL (0) | Wild type | 1.58 ± 0.18 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 11.4 ± 1.5 | 31.1 ± 7.3 | 7.84 ± 2.49 | 18.0 ± 1.9 |

| NL (0.04) | V32I, M46I, I84V | 9.66 ± 1.17 (6)a | 18.2 ± 0.07 (2)a | 19.4 ± 5.9 (2) | 753 ± 122 (24)a | 4.36 ± 1.63 (1) | 42.2 ± 3.8 (2)a |

| NL (0.20) | V32I, M46I, I84V, L89M | 152 ± 28 (96)a | 80.6 ± 11.7 (8)a | 99.1 ± 26.3 (9)a | 2207 ± 17 (71)a | 18.6 ± 0.6 (2)a | 921 ± 180 (51)a |

| BRU (0) | Wild type | 2.75 ± 0.27 | 11.4 ± 1.7 | 10.4 ± 2.6 | 50.7 ± 7.9 | 8.54 ± 1.72 | 29.4 ± 5.7 |

| BRU (0.028) | L10Y, I50L, A71V, N88S | 99.5 ± 8.4 (36)a | 10.4 ± 0.07 (1) | 13.8 ± 2.4 (1) | 3.13 ± 0.48 (0.06)a | 5.00 ± 0.44 (1) | 2.68 ± 0.86 (0.1)a |

| BRU (0.50) | L10Y, I50L, L63P, A71V, N88S | 256 ± 17 (93)a | 56.9 ± 9.12 (5)a | 16.9 ± 6.7 (2) | 5.19 ± 0.97 (0.1)a | 15.9 ± 1.3 (2)a | 4.54 ± 0.42 (0.15)a |

Fold decrease in sensitivity was found to be significant at the ≤0.05 levels using an unpaired t test. Results were derived from more than nine experiments for RF and four to five experiments for BRU and NL4-3, respectively.

The low-level-resistant NL4-3 strain (6-fold decrease in sensitivity) was sensitive to IDV, NFV, SQV, and APV but was resistant (24-fold) to RTV. The highly BMS-232632-resistant NL4-3 virus that carried the V32I, M46I, I84V, and L89M substitutions remained sensitive to SQV but showed eight- to ninefold decreases in sensitivity to NFV and IDV and a pattern of high-level cross-resistance to RTV and APV.

In contrast, the BRU strain of HIV-1 that contained the Prt mutations L10Y, I50L, A71V, and N88S (36-fold decrease in sensitivity to BMS-232632) displayed full sensitivity to all five Prt inhibitors evaluated. The highly resistant (93-fold) BRU strain that contained an additional mutation L63P exhibited only a modest decrease (5-fold) in sensitivity to NFV and remained sensitive to IDV and SQV. Most interestingly, these BRU variants displayed increased sensitivity to RTV and APV (compared to that of wild-type BRU virus), even though the virus carried the I50L Prt mutation (Table 4). Increased APV sensitivities were also observed in a study that characterized 200 viruses from patients who failed IDV and NFV therapy (46).

DISCUSSION

Today, the standard care for those infected with HIV involves three-drug combinations that include at least one HIV-1 Prt inhibitor. Because failure rates remain unacceptably high, there is still a significant need for Prt inhibitors with greater potency, decreased toxicity, and more favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics. Since resistance to anti-HIV-1 drugs is frequently encountered, we studied the development of resistance to BMS-232632 by passaging three strains of HIV-1 (strains RF, BRU, and NL4-3) in MT-2 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of inhibitor. For comparison, the RF virus was also exposed to IDV, NFV, RTV, or APV in parallel experiments in which the same procedure used for BMS-232632 was used. After exposure to BMS-232632 for 1 month, the RF virus strain showed a fourfold decrease in drug sensitivity and contained the N88S substitution in the Prt (Table 2). Selection with increasing concentrations (25 to 500 nM) of inhibitor resulted in an ordered accumulation of Prt mutations: N88S → M46I → A71V,V32I → L33F and I84V. The variant that carried the M46I and N88S changes exhibited a sixfold decrease in sensitivity, and the variant with the V32I, M46I, A71V, and N88S substitutions in Prt had a 12-fold decrease in sensitivity. The N88S substitution seems to be the only amino acid change that appeared consistently in this series of RF variants, and therefore, it is most likely associated with the development of BMS-232632 resistance in the RF background. The N88S substitution has not previously been implicated as an important resistance marker for any of the approved HIV-1 Prt inhibitors, although it has been observed as a secondary substitution in viruses recovered from patients treated with IDV, NFV, and SQV (5, 33, 42). The N88S substitution was reported as the signature mutation for SC-55389A (39), a hydroxyethylurea Prt inhibitor no longer being developed. Furthermore, the mechanism by which N88S contributes to resistance is intriguing, since residue 88 is distal to the active site in the crystal structure of the enzyme. For the RF virus strain to attain a very high level of resistance (183-fold decrease in sensitivity), two additional amino acid changes, L33F and I84V, seem to be required. This virus emerged in culture only after an extended period of time (4.8 months) and treatment with high concentrations (up to 500 nM) of BMS-232632.

Interestingly, the time course to resistance development and the resulting Prt mutations were different for the BRU, NL4-3, and RF strains of HIV-1 in the one set of experiments performed. In a comparison of the genetic backgrounds of these three viruses, the BRU and RF wild-type Prts contain four different amino acids at residues 10, 13, 37, and 41, while the NL4-3 and RF Prts vary at residues 10, 13, and 41. The wild-type Prt sequences of BRU and NL4-3 differ only at amino acid residue 37. However, passage of the BRU and NL4-3 strains in the presence of BMS-232632 was slower and more difficult in the initial 2 months compared to passage of the RF virus strain, even in the presence of lower concentrations of BMS-232632. It took approximately 3 months for the BRU and NL4-3 viruses to replicate to an appreciable level in the presence of BMS-232632, whereas it took only 1 month for RF variants to do so.

The resistance substitutions selected in the Prt and Prt cleavage sites (P7-P1 and P1-P6) were also very different for these three strains of viruses (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 2 to 4). The previously reported cleavage-site substitutions in P7-P1 (AN/F to VN/F) and P1-P6 (F/L to F/F) regions occurred only infrequently and in highly resistant BRU (93-fold decrease in sensitivity) and NL4-3 (96-fold decrease in sensitivity) variants. The specific cleavage-site changes selected by BMS-232632 included the area that spans P1-P6 (F/LQSRP to F/LQSRL) in the RF variant. Most interestingly, a 12-amino-acid deletion was observed at approximately 11 amino acids from the P1-P6 carboxyl terminus in the selected BRU variants. Close examination of the mutations that evolved in both Prt and the Prt cleavage sites in various passaged viruses did not reveal any apparent correlations. The growth properties of the BMS-232632-resistant HIV-1 strains did not differ significantly from those of wild-type virus. Thus, the significance of these changes external to the Prt requires further study.

Regarding the substitutions selected within the Prt gene, it is interesting that distinct mutational patterns accumulated over time across the three strains of HIV-1 studied: for BRU, N88S → L10Y/F, I50L, L63P, and A71V; for NL4-3, L23I → M46I → I84V → V32I → L89M; and for RF, N88S → M46I → A71V and V32I → L33F and I84V). Several of the amino acid substitutions that emerged during passage of the three HIV-1 strains in the presence of BMS-232632 are also associated with resistance to other Prt inhibitors. The frequently observed A71V and L10Y (the preexisting sequence in RF) substitutions were present in all three strains, while the V32I, M46I, and I84V substitutions emerged in two of the three strains examined. The N88S and L23I substitutions appeared early during passage and may represent important substitutions for BMS-232632 resistance. The late acquisition of the L89M substitution seemed to dramatically increase the levels of BMS-232632 resistance in the NL4-3 variant (from 6- to 96-fold). The NL4-3 variant also has a well-documented resistance mutation (I84V) located near the Prt active site, whereas the resistance phenotype of BRU is attributed to a non-active-site mutation, N88S, in combination with other substitutions at residues 10, 50, 63, and 71 (Table 2). This is surprising given that the two virus strains have Prt genes that differ only at residue 37 and displayed comparable resistance phenotypes. It is possible that intricate interactive effects among the amino acid residues in the Prt and gag-pol regions determine the Prt activity in response to external drug treatments. Additional studies will be required to understand the basis of this observation.

The cumulative resistance data from the RF, BRU, and NL4-3 virus strains revealed that the emergence of the I84V mutation in response to BMS-232632 depends not only on the concentration of the Prt inhibitor present but on the strain of virus as well. It was also likely that viruses with dissimilar genetic backgrounds acquire distinct sets of Prt and cleavage-site mutations and evolve at different rates to achieve resistance. This potential effect of the viral strain on resistance has previously been shown by failure of IDV in vitro resistance development in the NL4-3 virus but not in the HXB2 virus (40, 41). Our data have further stressed the importance of using several viral strains to study resistance development. Since our selection experiment was performed only once, there is no way of knowing whether these precise resistance patterns would again emerge upon passage of these virus strains in the presence of BMS-232632. It is also unclear whether any of the resistance patterns observed in vitro will be predictive of resistance development in treated patients.

The cross-resistance profiles of anti-HIV-1 drugs are of major importance in the selection of drugs for combination treatment and in the order in which they are used. The reciprocal cross-resistance studies (Tables 1 and 4) reported here showed that the cross-resistance pattern depends not only on the HIV strain but also on the level of resistance to the original drug against which the virus was selected. In general, there was no greater than ninefold reduction in sensitivity to BMS-232632 when the drug was tested against a panel of six Prt inhibitor-resistant strains, with significant retention of activity observed against viruses resistant to NFV, SQV, and APV (Table 1). BMS-232632-resistant viruses gave mixed results. Strains RF and NL4-3 showed various levels of cross-resistance to NFV, IDV, RTV, and, in some cases, APV. The BRU variants generally remained sensitive to IDV, NFV, and SQV, with increased sensitivity observed for RTV and APV. In no case was there any evidence of cross-resistance between SQV and BMS-232632, although the SQV-resistant virus used in these studies showed only low-level resistance to SQV.

These studies emphasize the complexity of cross-resistance development and the likely impact of genetic background. The current in vitro studies provide us with a number of important observations: that resistance to BMS-232632 is unlikely to result from a single mutation but instead will require the accumulation of a series of mutations to achieve a greater than sixfold decrease in sensitivity (Table 2) and that BMS-232632 retained activity in vitro against isolates that showed modest levels of resistance to other Prt inhibitors. Ongoing testing against a large panel of resistant clinical isolates should give a more precise answer to the cross-resistance question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Emini for providing the IDV-resistant clinical virus isolate; J. Leet, J.-F. Cutrone, and J. Golik for purification of the HIV-1 Prt inhibitors used in this study; W. Blair for critical discussion; and D. Morse for preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boden D, Markowitz M. Resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2775–2783. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron D W, Japour A J, Xu Y, Hsu A, Mellors J, Farthing C, Cohen C, Poretz D, Markowitz M, Follansbee S, Angel J B, McMahon D, Ho D, Devanarayan V, Rode R, Salgo M, Kempf D J, Granneman R, Leonard J M, Sun E. Ritonavir and saquinavir combination therapy for the treatment of HIV infection. AIDS. 1999;13:213–224. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrillo A, Stewart K D, Sham H L, Norbeck D W, Kohlbrenner W E, Leonard J M, Kempf D J, Molla A. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to ABT-378, a novel protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1998;72:7532–7541. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7532-7541.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condra J H, Schleif W A, Blahy O M, Gabryelski L J, Graham D J, Quintero J C, Rhodes A, Robbins H L, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Titus D, Yang T, Teppler H, Squires K E, Deutsch P J, Emini E A. In vivo emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple protease inhibitors. Nature. 1995;374:569–575. doi: 10.1038/374569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condra J H, Holder D J, Schleif W A, Blahy O M, Danovich R M, Gabryelski L J, Graham D J, Laird D, Quintero J C, Rhodes A, Robbins H L, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Yang T, Chodakewitz J A, Deutsch P J, Leavitt R Y, Massari F E, Mellors J W, Squires K E, Steigbigel R T, Teppler H, Emini E A. Genetic correlates of in vivo viral resistance to indinavir, a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1996;70:8270–8276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8270-8276.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig C, Race E, Sheldon J, Whittaker L, Gilbert S, Moffatt A, Rose J, Dissanayeke S, Chirn G W, Duncan I B, Cammack N. HIV protease genotype and viral sensitivity to HIV protease inhibitors following saquinavir therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:1611–1618. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig J C, Duncan I B, Hockley D, Grief C, Roberts N A, Mills J S. Antiviral properties of Ro 31-8959, an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) proteinase. Antivir Res. 1991;16:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90045-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyon L, Payant C, Brakier-Gingras L, Lamarre D. Novel gag-pol frameshift site in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants resistant to protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1998;72:6146–6150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6146-6150.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyon L, Croteau G, Thibeault D, Poulin F, Pilote L, Lamarre K. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1996;70:3763–3769. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3763-3769.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastman P S, Mittler J, Kelso R, Gee C, Boyer E, Kolberg J, Urdea M, Leonard J M, Norbeck D W, Mo H, Markowitz M. Genotypic changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with loss of suppression of plasma viral RNA levels in subjects treated with ritonavir (Norvir) monotherapy. J Virol. 1998;72:5154–5164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5154-5164.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eberle J, Bechowsky B, Rose D, Hauser U, Helm K V D, Gurtler L, Nitschko H. Resistance of HIV type 1 to proteinase inhibitor Ro 31-8959. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:671–676. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flexner D. HIV-protease inhibitors. Drug Ther. 1998;338:1281–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulick R M. Current antiretroviral therapy: an overview. Quality Life Res. 1997;6:471–474. doi: 10.1023/a:1018447829842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammer S M, Squires K E, Hughes M D, Grimes J M, Demeter L M, Currier J S, Eron J J, Jr, Feinberg J E, Balfour H H, Jr, Deyton L R, Chodakewitz J A, Fischl M A. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen H, Yasargil K, Winslow D L, Craig J C, Krohn A, Duncan I B, Mous J. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants with decreased sensitivity to proteinase inhibitor Ro 31-8959. Virology. 1995;206:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsen H, Hanggi M, Ott M, Duncan I B, Owen S, Andreoni M, Vella S, Mous J. In vivo resistance to a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteinase inhibitor: mutations, kinetics, and frequencies. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1379–1387. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson V A, Byington R E. Infectivity assay (virus yield assay) In: Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1990. pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz R A, Skalka A M. The retroviral enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:133–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempf D J, Marsh K C, Denissen J F, McDonald E, Vasavanonda S, Flentge C A, Green B E, Fino L, Park C H, Kong X P. ABT-538 is a potent inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus protease and has high oral bioavailability in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2484–2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin P F, Samanta H, Rose R E, Patick A K, Trimble J, Bechtold C M, Revie D R, Khan N C, Federici M E, Li H, Lee A, Anderson R E, Colonno R J. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type I isolates from patients on prolonged stavudine therapy. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1157–1164. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mammano F, Petit C, Clavel F. Resistance-associated loss of viral fitness in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phenotypic analysis of protease and gag coevolution in protease inhibitor-treated patients. J Virol. 1998;72:7632–7637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7632-7637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markowitz M, Mo H, Kempf D J, Norbeck D W, Narayana Bhat T, Erickson J W, Ho D D. Selection and analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to ABT-538, a novel protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1995;69:701–706. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.701-706.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz M, Conant M, Hurley A, Schluger R, Duran M, Peterkin J, Chapman S, Patick A, Hendricks A, Yuen G J, Hoskins W, Clendeninn N, Ho D. A preliminary evaluation of nelfinavir mesylate, an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) protease, to treat HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1533–1540. doi: 10.1086/515312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald C K, Kuritzkes D R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:951–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molla A, Granneman G R, Sun E, Kempf D J. Recent developments in HIV protease inhibitor therapy. Antivir Res. 1998;39:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molla A, Korneyeva M, Gao Q, Vasavanonda S, Schipper P J, Mo H-M, Markowitz M, Chernyavskiy T, Niu P, Lyons N, Hsu A, Granneman G R, Ho D D, Boucher C A B, Leonard J M, Norbeck D W, Kempf D J. Ordered accumulation of mutations in HIV protease confers resistance to ritonavir. Nat Med. 1996;2:760–766. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris-Jones S, Moyle G, Easterbrook P J. Antiretroviral therapies in HIV-1 infection. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 1997;6:1049–1061. doi: 10.1517/13543784.6.8.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyle G, Gazzard B. Current knowledge and future prospects for the use of HIV protease inhibitors. Drugs. 1996;51:701–712. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy R L, Gulick R M, DeGruttola V, D'Aquila R T, Eron J J, Sommadossi J P, Currier J S, Smeaton L, Frank I, Caliendo A M, Gerber J G, Tung R, Kuritzkes D R. Treatment with amprenavir alone or amprenavir with zidovudine and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infections. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 347 Study Team. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:808–816. doi: 10.1086/314668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Partaledis J A, Yamaguchi K, Tisdale M, Blair E E, Falcione C, Maschera B, Myers R E, Pazhanisamy S, Futer O, Cullinan A B, Stuver C M, Byrn R A, Livingston D J. In vitro selection and characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates with reduced sensitivity to hydroxyethylamino sulfonamide inhibitors of HIV-1 aspartyl protease. J Virol. 1995;69:5228–5235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5228-5235.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patick A K, Rose R, Greytok J, Bechtold C M, Hermsmeier M A, Chen P T, Barrish J C, Zahler R, Colonno R J, Lin P-F. Characterization of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant with reduced sensitivity to an aminodiol protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1995;69:2148–2152. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2148-2152.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patick A K, Mo H, Markowitz M, Appelt K, Wu B, Musick L, Kalish V, Kaldor S, Reich S, Ho D, Webber S. Antiviral and resistance studies of AG1343, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus protease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:292–297. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patick A K, Duran M, Cao Y, Shugarts D, Keller M R, Mazabel E, Knowles M, Chapman S, Kuritzkes D R, Markowitz M. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants isolated from patients treated with the protease inhibitor nelfinavir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2637–2644. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potts B J. “Mini” reverse transcriptase (RT) assay. In: Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1990. pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose R E, Gong Y F, Greytok J A, Bechtold C M, Terry B J, Robinson B S, Alam M, Colonno R J, Lin P F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virus background plays a major role in development of resistance to protease inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1648–1653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schapiro J M, Winters M A, Stewart F, Efron B, Norris J, Kozal M J, Merigan T C. The effect of high-dose saquinavir on viral load and CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:1039–1050. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-12-199606150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schinazi R F, Larder B A, Mellors J W. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance. Int Antivir News. 1999;7:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmit J-C, Ruiz L, Clotet B, Roventos A, Tor J, Leonard J, Desmyter J, De Clercq E, Vandamme A M. Resistance related mutations in the HIV-1 protease gene of patients treated for 1 year with the protease inhibitor ritonavir (ABT-538) AIDS. 1996;10:995–999. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smidt M L, Potts K E, Tucker S P, Blystone L, Stiebel T R, Jr, Stallings W C, McDonald J J, Pillay D, Richman D D, Bryant M L. A mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease at position 88, located outside the active site, confers resistance to the hydroxyethylurea inhibitor SC-55389A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:515–522. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tisdale M, Myers R E, Maschera B, Parry N R, Oliver N M, Blair E D. Cross-resistance analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants individually selected for resistance to five different protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1704–1710. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vacca J P, Dorsey B D, Schleif W A, Levin R B, McDaniel S L, Darke P L, Zugay J, Quintero J C, Blahy O M, Roth E. L-735,524: an orally bioavailable human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4096–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacca J P, Condra J H. Clinically effective HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 1997;2:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volberding P A. Advances in the medical management of patients with HIV-1 infection: an overview. AIDS. 1999;13:S1–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weislow O S, Kiser R, Fine D L, Bader J, Shoemaker R H, Boyd M R. New soluble-formazan assay for HIV-1 cytopathic effects: application to high-flux screening of synthetic and natural products for AIDS-antiviral activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.8.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y-M, Imamichi H, Imamichi T, Lane H C, Falloon J, Vasudevachari M B, Salzman N P. Drug resistance during indinavir therapy is caused by mutations in the protease gene and in its Gag substrate cleavage sites. J Virol. 1997;71:6662–6670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6662-6670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziermann R, Limoli K, Petropoulos C J, Parkin N T. The N88S mutation in HIV-1 protease is associated with increased susceptibility to amprenavir. Antivir Ther. 1999;4(Suppl. 1):62. [Google Scholar]