Abstract

Antibodies that target immune checkpoint proteins such as programmed cell death protein 1, programmed death ligand 1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 in human cancers have achieved impressive clinical success; however, a significant proportion of patients fail to respond to these treatments. Galectin-9 (Gal-9), a β-galactoside-binding protein, has been shown to induce T-cell death and facilitate immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment by binding to immunomodulatory receptors such as T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing molecule 3 and the innate immune receptor dectin-1, suggesting that it may have potential as a target for cancer immunotherapy. Here, we report the development of two novel Gal-9-neutralizing antibodies that specifically react with the N-carbohydrate-recognition domain of human Gal-9 with high affinity. We also show using cell-based functional assays that these antibodies efficiently protected human T cells from Gal-9-induced cell death. Notably, in a T-cell/tumor cell coculture assay of cytotoxicity, these antibodies significantly promoted T cell-mediated killing of tumor cells. Taken together, our findings demonstrate potent inhibition of human Gal-9 by neutralizing antibodies, which may open new avenues for cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: cancer biology, immunotherapy, monoclonal antibody, immune checkpoint, TIM-3, galectin-9

Abbreviations: CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; CD, cluster of differentiation; CRD, carbohydrate-recognition domain; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4; ECD, extracellular domain; Gal-9, galectin-9; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; Ig, immunoglobin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; TIM-3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing molecule 3; Treg, regulatory T cell

Therapeutic blockade of immune checkpoints including the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death ligand 1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) has revolutionized cancer treatment and provided durable clinical response in multiple cancer types. However, the remarkable responses are currently limited to a minority of patients (1, 2), highlighting the need for identifying new therapeutic targets to further boost the immune response and benefit more patients.

Galectin-9 (Gal-9) is a member of the galectin family with two conserved carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs) for beta-galactosides (3). This special structural characteristic renders Gal-9 capable of crosslinking glycoconjugates, including glycoproteins (such as cell surface receptors) and glycolipids, thereby modulating cell signaling (4). Despite common affinities for β-galactosides, each CRD of Gal-9 has distinct glycan-binding specificity (5). Gal-9 is constitutively expressed in antigen-presenting cells and induced by interferon β in cancer cells (6). Secretion of Gal-9 from both antigen-presenting cells and cancer cells is upregulated by interferon β and γ (6). Gal-9 primarily plays an immunosuppressive role in the tumor microenvironment, via binding with several cell surface receptors expressed on immune cells. Although Gal-9 was initially identified as a ligand for T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing molecule 3 (TIM-3) in the induction of T-cell death (7), it also binds to other immunoregulatory receptors. For instance, Gal-9 binding to the innate receptor dectin-1 promotes M2 polarization of macrophages that suppresses antitumor immune responses (8). Gal-9 has also been shown to promote the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) through interaction with cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44) (9) and drive the expansion of Tregs through binding with death receptor 3 (10). In patients with virus-associated solid tumors, Gal-9 is coexpressed with PD-1 and T-cell immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory-motif domain in exhausted T cells, and its expression defines natural killer cells impaired cytotoxicity (11). Thus, Gal-9 is involved in multiple immunomodulatory pathways.

Similar to other immune checkpoint molecules (12), the prognostic values of Gal-9 also vary greatly across cancers. While Gal-9 expression is associated with favorable outcome in some cancers (13), it is associated with unfavorable prognosis in some other cancers, notably in hard-to-treat cancers, such as brain, pancreatic cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia. The levels of Gal-9 have been shown to be elevated in the tumor tissues and plasma of cancer patients and correlate with poor patient survival rates and aggressive disease in multiple tumor types. In glioblastoma multiforme, the most invasive and incurable type of glioma, Gal-9 is highly upregulated compared with normal brain tissues and lower-grade glioma and correlates with poor patient survival (14, 15). Gal-9 is also highly expressed in both tumor cells and immune cells of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (16, 17). In melanoma, Gal-9 levels are elevated in patients’ plasma compared with the healthy controls (18), and notably, Gal-9 expression is found to be higher in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from nonresponders to anti-PD-1 therapy, compared with those from the responders (6). Human myeloid leukemia stem cells have been shown to secrete Gal-9, which forms an autocrine stimulatory loop with TIM-3 to drive the self-renewal of leukemia stem cells and leukemic progression (19, 20). The aberrantly high expression of Gal-9 in a range of cancers suggests that Gal-9 could be significant both as a biomarker and a therapeutic target.

The efficacy of Gal-9 blockade in vivo has been investigated in several mouse models of cancer. In the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mouse model, blockade of Gal-9 slows tumor progression and extends mouse survival (8). In the mouse models of colon cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, Gal-9-neutralizing antibody in combination with an agonist antibody to the T-cell costimulatory receptor glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor–related protein synergistically suppresses tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival (6). Thus, Gal-9-neutralizing antibody has a great potential for cancer immunotherapy as a single agent or in combination with other modalities.

Here, we report the development and characterization of antihuman Gal-9 antibodies that are highly efficient in protecting T cells from Gal-9-induced cell death and promoting the killing of cancer cells by T cells. Our study demonstrates the potential efficacy of human Gal-9 antibodies in vitro and provides a rationale for targeting Gal-9 in cancer immunotherapy.

Results

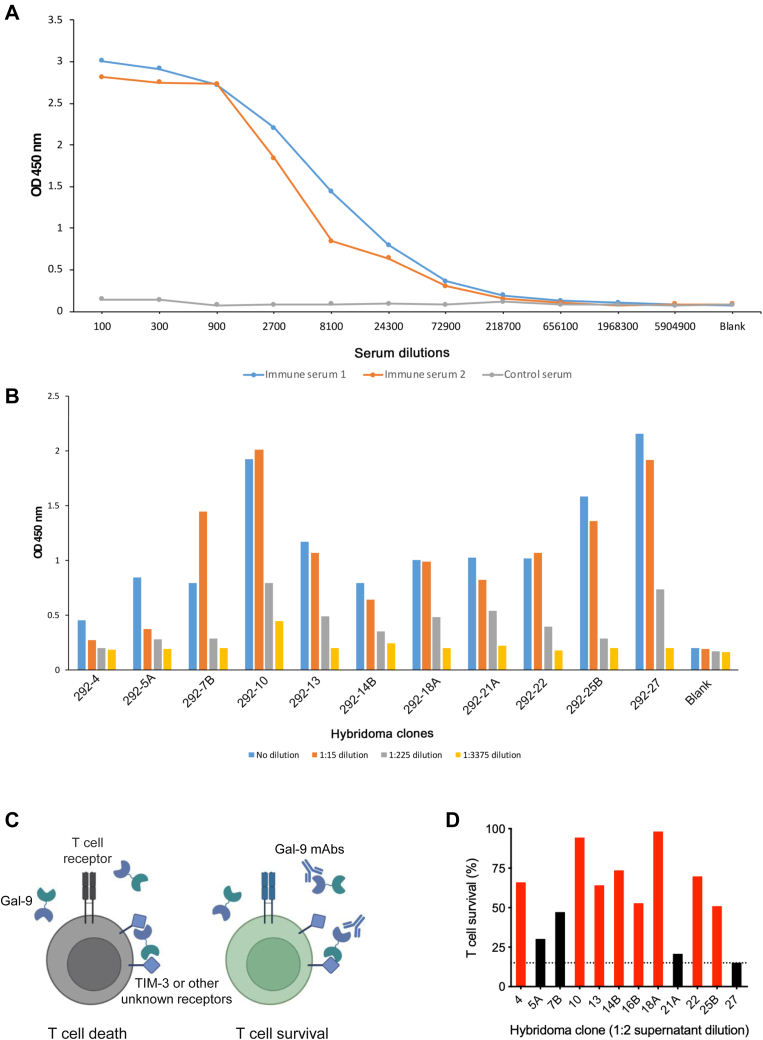

Generation of monoclonal human Gal-9 antibodies

To generate monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against human Gal-9, we purified full-length human Gal-9 protein and then immunized BALB/c mice with the recombinant Gal-9 protein. After the third immunization, we obtained serum from each mouse and titrated it for reactivity to human Gal-9 by ELISA. We found that sera from two mice reacted significantly to human Gal-9 (Fig. 1A), and mice 1# that demonstrated higher titers of Gal-9 antibodies were selected for antibody development. The splenocytes from mice 1# were then fused with the myeloma cell line Sp2/0 to generate hybridomas. We subsequently collected the hybridoma supernatants and investigated their reactivity to human Gal-9 by ELISA. We found that 11 hybridoma clones secreted Gal-9 antibodies (Fig. 1B). To evaluate the ability of these antibodies to neutralize Gal-9′ activity to induced T-cell death (Fig. 1C), human T cells expanded from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with the anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 were incubated with Gal-9 in the absence or the presence of hybridoma supernatants containing Gal-9 mAbs, and T-cell survival was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. We found that most of the clones tested protected T cells from Gal-9-induced death (Fig. 1D); notably, eight clones, including 292-4, 292-10, 292-13, 292-14B, 292-16B, 292-18A, 292-22, and 292-25B, showed high activity to inhibit Gal-9-induced T-cell death and thus were selected as candidates for antibody purification. These data indicated that human Gal-9–neutralizing mAbs were successfully generated.

Figure 1.

Generation of Gal-9 mAbs.A, Gal-9 antiserum titration by ELISA. Two BALB/c mice were immunized with human Gal-9 protein. After the third immunization, serum was obtained, serially diluted, added to the plate immobilized with Gal-9 protein, and analyzed by ELISA. B, titration of hybridoma supernatants by ELISA. Supernatants from various antibody clones were serially diluted, added to the plate immobilized with Gal-9 protein, and analyzed by ELISA. C, schematic diagram of neutralizing Gal-9 antibodies to prevent Gal-9-induced T-cell death. Gal-9 crosslinks TIM-3 or other unidentified receptors with its N-terminal and C-terminal CRDs to induce T-cell death (left); Gal-9-neutralizing antibodies disrupt such crosslinking and inhibit Gal-9-induced T-cell death (right). D, analysis of T-cell survival by MTS assay. T cells were incubated overnight with 2 μg/ml Gal-9 in the presence of indicated hybridoma supernatants. Cell survival in the absence of Gal-9 was considered as 100%. Dashed line denotes cell survival when control supernatant was used. Red columns represent the hybridoma clones selected for the following experiments, and the black ones represent the clones not selected. CRD, carbohydrate-recognition domain; Gal-9, galectin-9; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; TIM-3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing molecule 3.

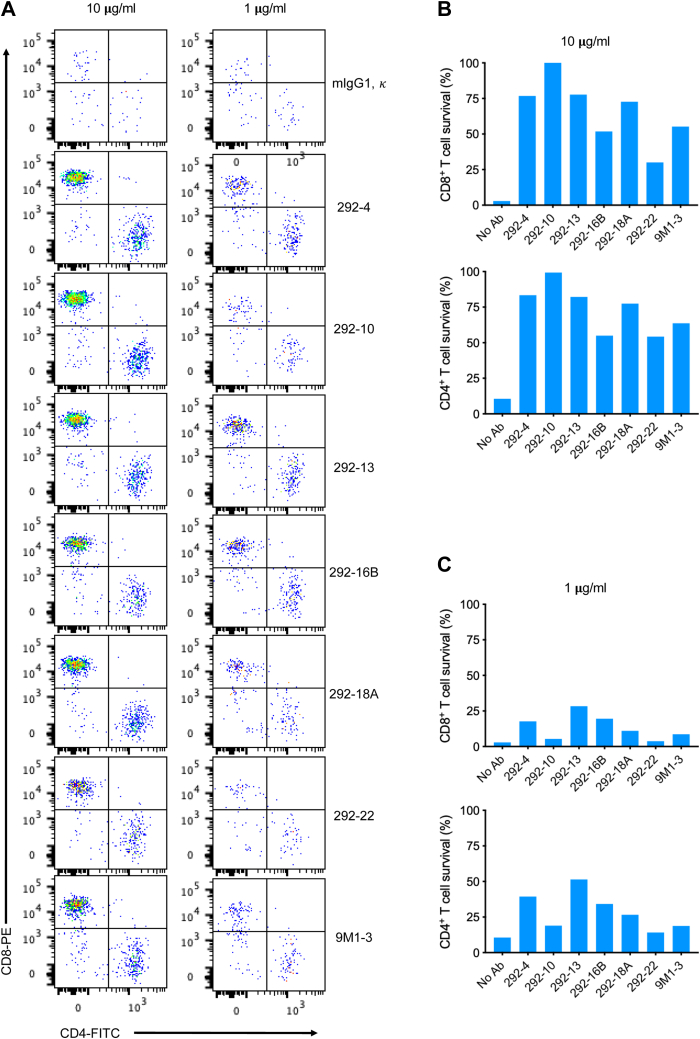

Gal-9 mAbs protect T cells from Gal-9-induced cell death

Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are sensitive to Gal-9-induced death (6). To further evaluate the neutralizing capacity of our Gal-9 mAbs to protect T cells from Gal-9-induced cell death, we incubated T cells with Gal-9 in the presence of different concentrations of purified Gal-9 mAbs and analyzed the survival of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. Fluorescent microspheres (BD FACS AccuDrop Beads) were used as an internal counting standard, and viable CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were quantified with these counting beads, which were separated from the cells as a narrow band in a forward-scatter plot versus side-scatter plot (Fig. 2A). We found that all Gal-9 mAbs tested protected T cells from Gal-9-induced death; some clones, such as 292-4, 292-13, 292-16B, and 292-18A, at concentration as low as 1 μg/ml, efficiently inhibited Gal-9-induced death of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, performing better than the commercially available 9M1-3 antibody (Fig. 2, B and C). These clones protect T cells from Gal-9-induced death to a similar extent to lactose, a well-established blocker of galectin CRDs (Fig. S1A). Although TIM-3 is not the only receptor that mediates Gal-9’s cell death–inducing activity (21), most T cells used in these experiments express this receptor (Fig. S1B). These results showed that our Gal-9 mAbs potently protected T cells from Gal-9-induced cell death.

Figure 2.

Gal-9 mAbs protect T cells from Gal-9-induced death. A, gating strategy to quantify viable CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. Pseudocolor plots of events equivalent to 3000 counting beads. B, analysis of the survival of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. T cells were incubated with 2 μg/ml Gal-9 in the presence of indicated doses of control mouse IgG or different Gal-9 mAb clones. After overnight incubation, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell survival was measured as described for (A). C, quantitation of the survival of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The experiment was performed as described for (B). CD, cluster of differentiation; Gal-9, galectin-9; IgG, immunoglobulin G; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

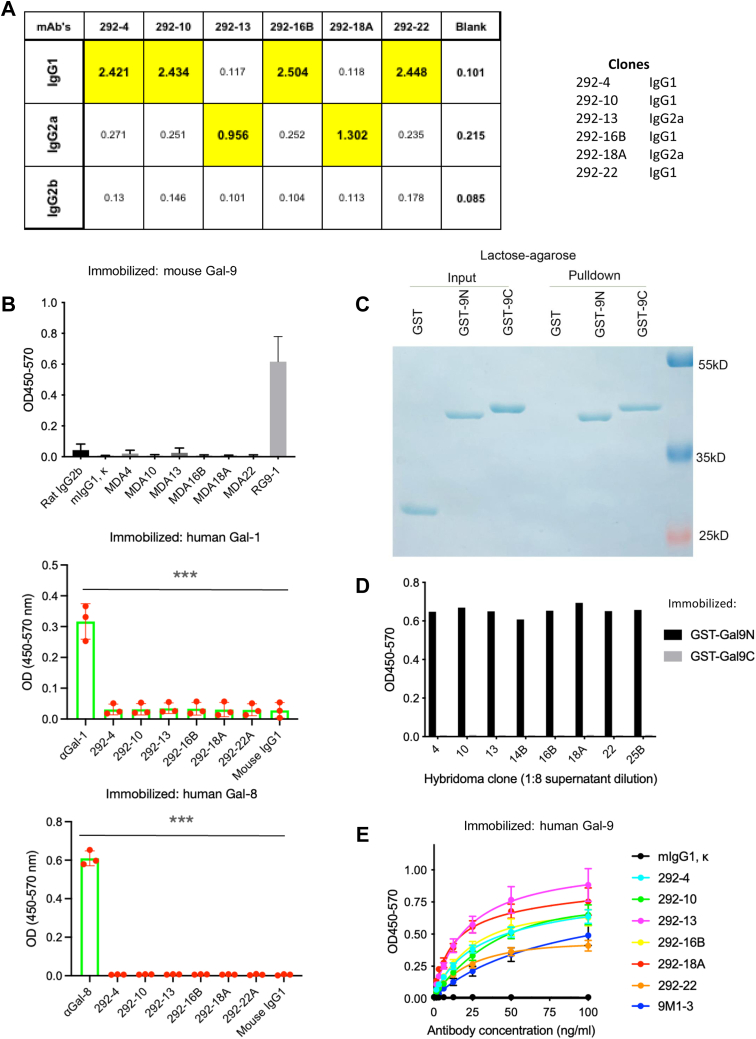

Characterization of Gal-9 mAbs

By using the ELISA-based isotyping kit, we analyzed the isotypes of the antibodies, and the results showed that four clones (292-4, 292-10, 192-16B, and 292-22) are immunoglobin G1 (IgG1) and two clones (292-13 and 292-18A) were IgG2a (Fig. 3A). We tested their crossreactivity with mouse Gal-9 by coating the plate with mouse Gal-9, with a mouse Gal-9 antibody (RG9-1) as a positive control. Figure 3B showed that none of human Gal-9 antibody clones significantly crossreacted with mouse Gal-9. Similarly, no crossreactivity with other human galectins, such as Gal-1 or Gal-8, was detected (Fig. 3B). Gal-9 consists of an N-CRD and a C-CRD connected by a linker region. To identify the domain that our Gal-9 antibodies reacted to, we purified each of the two glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fused CRDs, validated their binding activities with lactose-bead pull-down assay (Fig. 3C), and then immobilized them on the plate for ELISA. We found that all the Gal-9 antibodies that were tested reacted exclusively with GST-fused N-CRD (GST-9N) but not C-CRD (GST-9C) (Fig. 3D). Next, we evaluated the binding affinity of these antibody clones by ELISA and identified clones 292-13 and 292-18A as the strongest binders, both exhibiting higher binding affinity to Gal-9 compared with the commercially available 9M1-3 antibody (Fig. 3E). We therefore focused on these two antibodies in the ensuing experiments.

Figure 3.

Characterization of Gal-9 mAbs. A, analysis of Gal-9 mAb isotypes by ELISA. B, analysis of human Gal-9 antibody crossreactivity with mouse Gal-9 or other human galectins by ELISA. Maxisorp plates were coated with mouse Gal-9, human Gal-1, or human Gal-8, and binding to control or indicated Gal-9 mAbs was determined by ELISA. Antibody to mouse Gal-9 (RG9-1), human Gal-1, or human Gal-8 was included as positive control. Data (mean values ± SD) from three independent experiments are shown. Statistical differences were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t tests. C, analysis of binding of GST-fusion protein of Gal-9 CRDs to lactose. GST, GST-9N, or GST-9C was incubated with lactose–agarose. Bound proteins were eluted and analyzed with loading controls by SDS-PAGE. D, analysis of Gal-9 mAb binding to Gal-9 domains by ELISA. Maxisorp plates were coated with GST-9N or GST-9C, and binding to indicated hybridoma clone supernatants (1:8 dilution) was analyzed by ELISA. E, evaluation of binding affinity to human Gal-9 by ELISA. Maxisorp plates were coated with human Gal-9, and binding to indicated control or Gal-9 mAbs was determined by ELISA. Data (mean values ± SD) from three independent experiments are shown. Statistical differences were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t tests to compare area under the curves. CRD, carbohydrate-recognition domain; Gal-9, galectin-9; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; mAb, monoclonal antibody.

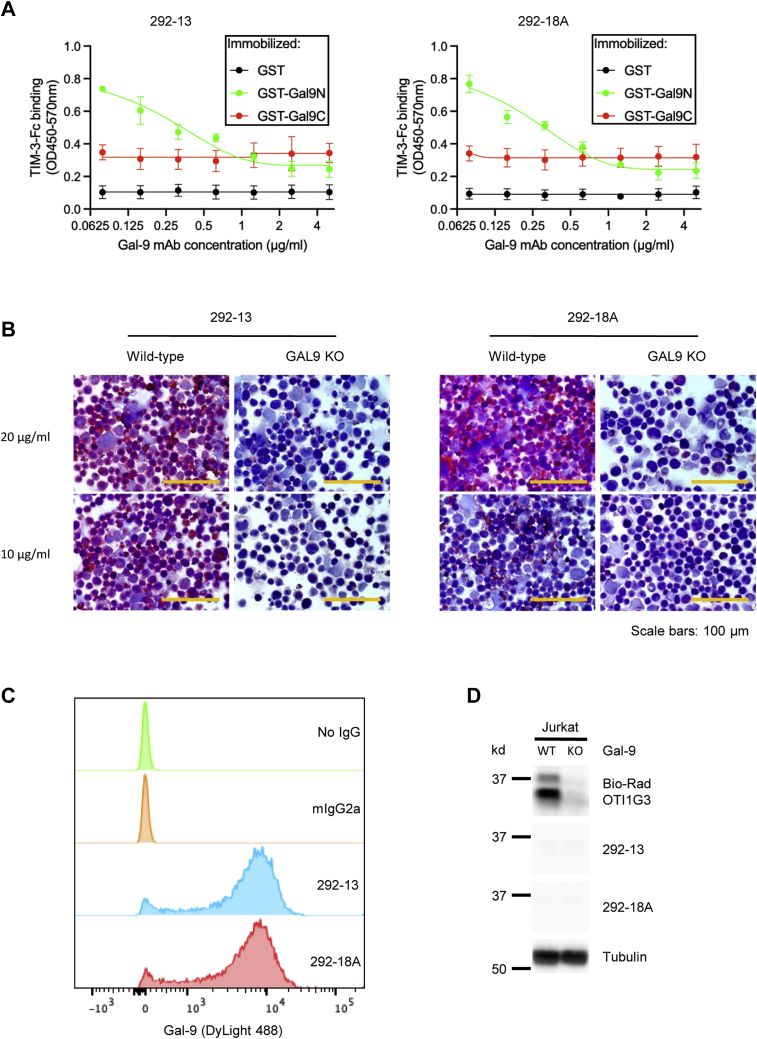

As expected, the two Gal-9 mAbs blocked the binding of GST-9N, but not GST-9C, to TIM-3, in a dose-dependent manner, as demonstrated by the plate-based binding assay (Fig. 4A). To test the binding specificity of these two antibodies in cells, we generated Gal-9 knockout Jurkat T cells using the CRISPR–Cas9 system by lentivirus transduction and then performed immunocytochemistry with the two antibody clones. Strong staining of Gal-9 was found in WT Jurkat cells (Gal-9+) but none in Gal-9 KO cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting the high binding specificity of these two antibodies. The two antibodies efficiently stained intracellular Gal-9 in flow cytometric assays (Fig. 4C) but did not denature Gal-9 in Western blotting (Fig. 4D). We also confirmed the inhibition of Gal-9-induced cell death by the two antibodies using apoptosis assay with annexin V/propidium iodide staining (Fig. S2A) and Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Fig. S2B) in Jurkat T cells. The results showed that 292-13 and 292-18A protected Jurkat T cells from Gal-9-induced death in a dose-dependent manner, with EC50 values of approximately 1 μg/ml (Fig. S2B). Thus, our Gal-9 mAbs exhibit high binding affinity and specificity to the N-CRD of native human Gal-9 and efficiently inhibit Gal-9-induced T-cell death.

Figure 4.

Characterization of 292-13 or 292-18A.A, analysis of blocking of Gal-9 (N-CRD)/TIM-3 binding by ELISA. Maxisorp plates were coated with GST, GST-9N, or GST-9C and then incubated with TIM3-ECD Fc in the presence of indicated concentrations of Gal-9 mAb clones 292-13 or 292-18A. Binding of Gal-9 CRDs to TIM-3-ECD Fc was determined by ELISA. Data (mean values ± SD) from three independent experiments are shown. Statistical differences were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t tests. B, analysis of antibody-binding specificity to cellular human Gal-9 by immunocytochemistry. WT or Gal-9 KO Jurkat cells were stained with indicated Gal-9 mAbs and then analyzed by immunocytochemistry. C, detection of cellular Gal-9 by Gal-9 mAbs via flow cytometry. Jurkat cells were stained with indicated control IgG or Gal-9 mAbs and then analyzed by flow cytometry. D, detection of Gal-9 expression by Gal-9 mAbs via Western blot. WT or Gal-9 KO Jurkat cell was lysed and stained for Western blot analysis with indicated Gal-9 mAbs or a positive control Gal-9 antibody (Bio-Rad; OTI1G3). CRD, carbohydrate-recognition domain; ECD, extracellular domain; Gal-9, galectin-9; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; mAb, monoclonal antibody; TIM-3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing molecule 3.

Gal-9 mAbs promote T-cell-mediated killing of tumor cells

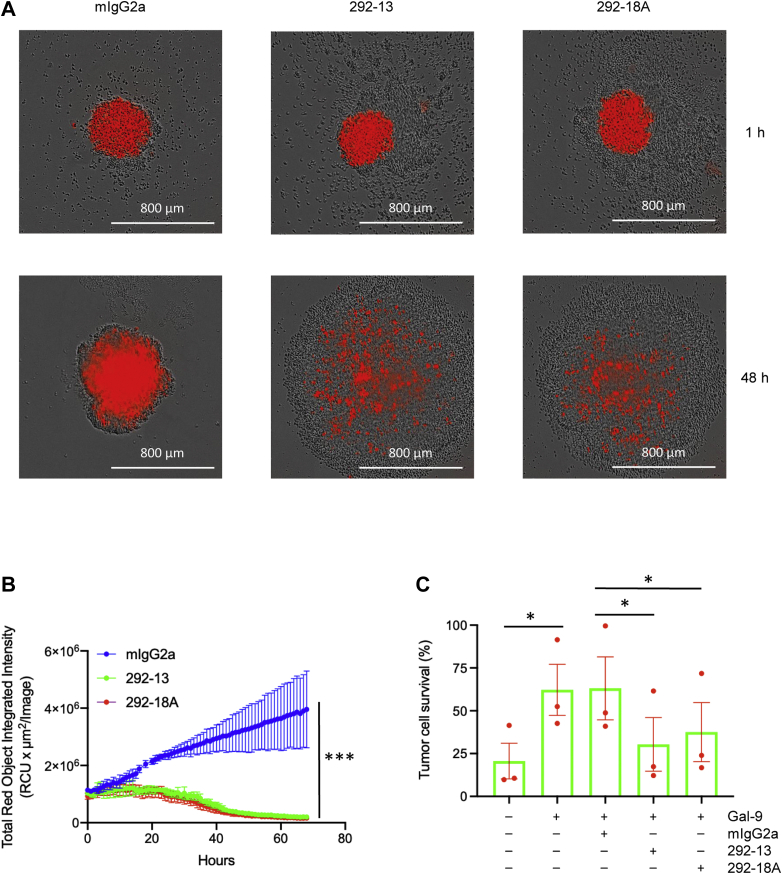

Based on the capacity of our Gal-9 antibodies to inhibit Gal-9-induced T-cell death (Figs. 2, S1 and S2), we postulated that these antibodies would promote T-cell-mediated killing of tumor cells when Gal-9 is present. To evaluate their efficacy in vitro, we used a cytotoxicity assay in which activated T cells in PBMCs were engaged with tumor cells (6), in the presence of the antibody clones 292-13 or 292-18A. In this assay, A375 human melanoma cells were engineered to express the extracellular domain (ECD) of FcγR2a and nuclear mCherry, a red fluorescent protein. The addition of the anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 is expected to trigger T-cell killing of tumor cells by simultaneously engaging T cells with tumor cells and activating T cells. Using this system, we showed that in the presence of Gal-9, both 292-13 and 292-18A antibodies efficiently promoted tumor-cell killing mediated by T cells (Figs. 5, A and B, S3 and S4). This was further confirmed by using A549 human lung cancer cells as the target cells (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrated that our Gal-9-neutralizing mAbs induce potent antitumor immunity in vitro.

Figure 5.

Promotion of T-cell-mediated tumor cell killing by Gal-9 mAbs.A, live cell image of T-cell-mediated A375 tumor cell killing. A375 cancer cells expressing FcγR2a and nuclear mCherry were cocultured with PBMCs in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody, Gal-9, and indicated control IgG or Gal-9 antibodies in 96-well U-bottom ultralow-binding plates. The survival of tumor cells (red) was monitored using IncuCyte. B, quantitation of tumor cell survival during incubation. Experiment was performed as described for (B). Data (mean values ± SD) from four independent experiments are shown. Statistical differences were assessed using unpaired two-tailed t tests to compare area under the curves. C, evaluation of T-cell-mediated A549 lung cancer cell killing by CCK-8 assay. A549 cells expressing FcγR2a and nuclear mCherry were cocultured with PBMCs in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody, Gal-9, and indicated control IgG or Gal-9 antibodies in 96-well plates. After 3 days of incubation, the survival of cancer cells was measured by CCK-8 assay. Data (mean values ± SD) from three PBMC donors are shown. Statistical differences were assessed using paired two-tailed t tests. CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; CD, cluster of differentiation; Gal-9, galectin-9; IgG, immunoglobulin G; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint therapy targeting PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 and CTLA-4 has revolutionized the field of cancer treatment by prolonging survival of patients with aggressive cancers (22). New targets for checkpoint blockade are also being investigated to further enhance the power of this approach. TIM-3 is another negative regulator of the T-cell response. Rather than dampening T-cell activity like PD-1 or CTLA-4, it induces T-cell death following Gal-9 binding (7). Several anti-TIM-3 antibodies have been evaluated in preclinical studies and some in clinical trials. However, most of these antibodies do not inhibit Gal-9–TIM-3 interaction, likely explaining their lackluster performance in these studies (23). Gal-9 has been shown to impair the immune response, but its potential as a therapeutic target has not been substantially explored. Here, we developed two human Gal-9-neutralizing antibodies and demonstrated their ability to protect T cells from Gal-9-induced death and promote T-cell-mediated tumor cell killing. Compared with inhibition of Gal-9 by small-molecule inhibitors, neutralizing Gal-9 by antibodies is expected to have the following advantages: (1) specific to Gal-9 and not affecting other members of galectin family and (2) restricted to extracellular Gal-9 and not affecting the intracellular Gal-9 with distinct functions (24). So far, very few human Gal-9 antibodies have been reported; they have been shown to perform well in preclinical studies, and some have entered clinical trials for hard-to-treat cancers. Of note, most of these Gal-9 antibodies target epitopes in the C-CRD (25, 26, 27), in contrast to ours that target the N-CRD. As the two domains have different binding specificities, antibodies targeting different Gal-9 domains are likely to have distinct functional outcomes.

In this study, we mainly focused on T cells and used T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay to evaluate the efficacy of our Gal-9 antibodies. We demonstrated that two human Gal-9 antibodies, 292-13 and 292-18A, efficiently protect T cells from Gal-9-induced death and promote T-cell-mediated tumor cell killing. Although TIM-3 is a well-established important receptor and mediator for Gal-9 function, other TIM-3-independent mechanisms of Gal-9 actions have also been reported. Gal-9 could stimulate the polyclonal activation of T cells in an antigen-independent manner (28), the biological function of which remains unclear yet. Furthermore, Gal-9 is important for dendritic cell maturation (29), Treg expansion/differentiation (9, 30), macrophage polarization (8) and natural killer cell function (11, 31). In addition to immune cells, Gal-9 could also directly bind to cancer cells and regulate the various biological processes including cell death; however, cancer cells have been shown to be much less sensitive to Gal-9-induced cell death than primary T cells (6). Still, given the multiple potential biological functions of Gal-9, further experiments are warranted to investigate the effects of Gal-9 antibodies on different cell types. On the cancer immunotherapy front, there are some potential caveats to targeting Gal-9 for cancer treatment, which may require additional therapeutic modalities to achieve better efficacy. Indeed, our group found that Gal-9 blockade in combination with an agonist of glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor showed significantly higher efficacy than monotherapy with either agent in suppressing tumor growth and extending mouse survival (6). It will be intriguing to investigate other anti-Gal-9–based combination strategies in the future, using preclinical animal-derived and patient-derived organoid tumor models.

The prognostic values of immune checkpoint molecules vary greatly across cancers, even within the same molecular subtype (12), and Gal-9 is often coexpressed with other immune checkpoints (32, 33). As such, the correlation between Gal-9 expression and patient prognosis also varies across cancer types. Although high Gal-9 expression is associated with unfavorable prognosis in some hard-to-treat cancers, such as brain tumor (34), pancreatic cancer (16, 35), and acute myeloid leukemia (36), it is associated with favorable outcome in some other cancers (13). In the latter cases, Gal-9 expression likely indicates the activated status of immune responses, as Gal-9 is mainly expressed by immune cells including T cells and induced in tumor cells by inflammatory cytokines such as interferons (6, 37). Thus, tumors that express high Gal-9 are likely T-cell-inflamed “hot” tumors that have high T-cell infiltration, which is known to have better survival and stronger response to immunotherapy (38, 39, 40). Indeed, ours and others' recent work with Gal-9 KO mice and Gal-9-neutralizing antibodies in mouse cancer models clearly demonstrate the activity of Gal-9 in suppression of antitumor immune response and serves as a proof of concept for the development and application of agents that inhibit Gal-9 function (6, 8, 41).

In summary, we report the development and characterization of two novel human Gal-9 antibodies that efficiently protect T cells from Gal-9-induced death and promote cancer cell killing mediated by T cells. Our findings demonstrate the efficacy and importance of Gal-9-neutralizing antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Further assessments of these antibodies in the preclinical investigations are warranted. As Gal-9 blockade promotes immune response through mechanisms distinct from those of PD-1 or CTLA-4 blockade, these anti-Gal-9 antibodies represent a new class of immune checkpoint inhibitors that have the potential to overcome resistance to current immunotherapies.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines and reagents

All cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, independently validated by short tandem repeat DNA fingerprinting at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and negative for mycoplasma infection. The 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, and Jurkat T cells and A375 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 media (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Primary human T cells were expanded from human PBMCs (Stemcell Technologies). Commercially available anti-Gal-9 antibodies, 9M1-3, OTI1G3, and RG9-1, were purchased from BioLegend, Bio-Rad, and GeneTex, respectively. Antibody against tubulin was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. FITC-labeled CD4 and phycoerythrin-labeled CD8 antibodies were purchased from BioLegend. ELISA-based isotyping kit (Mouse Monoclonal Antibody Isotyping Reagents) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich.

Purification of recombinant Gal-9 protein

Human full-length Gal-9, mouse full-length Gal-9, and GST-fused human N-CRD or C-CRD Gal-9 were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously (6). In brief, pET21a-Gal-9 construct was transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) (Sigma–Aldrich). Cells were allowed to grow in 2xYT medium to log phase, and then IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. The culture was incubated at 20 °C overnight and then harvested and lysed in B-PER reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per the manufacturer's instruction. Gal-9 was then purified by affinity chromatography on a lactosyl-agarose column (Sigma–Aldrich). For the purification of GST-fused N-CRD or C-CRD Gal-9, pGEX-N-CRD or pGEX-C-CRD constructs were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 and then purified by affinity chromatography with glutathione-conjugated Sepharose beads (GenScript) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Production of Gal-9 mAbs

Immunization of mice with purified full-length human Gal-9 and production of mAbs were carried out by the MD Anderson Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility. Briefly, hybridomas producing mAbs against human Gal-9 were obtained by the fusion of SP2/0 murine myeloma cells with spleen cells isolated from human Gal-9-immunized BALB/c mice according to the standardized protocol. Before fusion, sera from the immunized mice were validated for binding to the Gal-9 immunogen using ELISA. Candidate mAb-producing hybridomas were selected, and the antibody-containing supernatants were concentrated and purified. This study complied with relevant ethical regulations for animal testing and research and received ethical approval from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

ELISA

Nunc Maxisorp ELISA plates (BioLegend) were coated with 2 μg/ml of full-length Gal-9 or GST-fusion proteins of individual domains in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Plates were then washed, coated with bovine serum albumin, and incubated with various dilutions of hybridoma supernatants or purified Gal-9 antibodies. This was followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–labeled antimouse IgG antibodies (Sigma–Aldrich). After washes, the plates were incubated with 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min, and then the reaction was terminated by the addition of H2SO4. Absorbances at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 570 nm were then determined using a BioTek Synergy Neo2 plate reader. To measure the blocking of Gal-9 CRD/TIM-3 ECD binding by the mAbs, plates were coated with 2 μg/ml GST or each GST-fused Gal-9 CRD and then incubated with 0.5 μg/ml TIM3-ECD Fc in the presence of increasing concentrations (0–5 μg/ml) of Gal-9 mAbs. Binding Gal-9 CRD to TIM-3-ECD Fc was determined as described previously.

Immunocytochemistry

Jurkat cells were mounted on glass slides precoated with poly-l-lysine and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-100. The slides were then incubated with anti-Gal-9 primary antibodies at 10 μg/ml or 20 μg/ml at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with antimouse biotin-conjugated secondary antibody, and then mixed with an avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex. Amino-ethylcarbazole chromogen was used for visualization. The images were visualized with Olympus BX43 microscope and then analyzed with cellSens imaging software (Olympus).

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (42). In brief, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween-20 and 5% fat-free dry milk, incubated first with primary antibodies and then with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. Specific protein bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Biotechnology).

Generation of Gal-9 KO cells by lentiviral infection

The plasmid pLenti CRISPR-Gal-9 KO was constructed as described previously (6). To generate Jurkat Gal-9 KO cells, 293T cells were cotransfected with pLenti CRISPR-Gal-9 KO construct (4 μg) with pCMV-dR8.2 (3 μg) and pCMV-VSVG (1 μg) helper constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies). Viral stocks were harvested from the culture medium after 3 days and then filtered to remove nonadherent 293T cells. To select cells that stably express the Gal-9 KO constructs, 1 × 106 Jurkat cells were infected with a cocktail of 1 ml of virus-containing medium, 1 ml of regular medium, and 8 μg/ml polybrene, and then selected in 1 μg/ml of puromycin (InvivoGen) 72 h after lentivirus infection.

Flow cytometry

For intracellular Gal-9 staining, Jurkat cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and then washed with staining buffer (PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% NaN3). Cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl SP buffer (staining buffer supplemented with 0.1% saponin) containing 10 μg/ml mouse anti-Gal-9 antibodies and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed again, resuspended in 100 μl SP buffer containing goat antimouse IgG secondary antibody, DyLight 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalog no.: 35502) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After that, cells were washed with SP buffer, resuspended in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed with FlowJo (BD Biosciences). For apoptosis analysis, FITC-Annexin V/7-AAD (7-amino-actinomycin D) Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were collected and stained with FITC-annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D in the binding buffer for 15 min in the dark and then analyzed by flow cytometer within 1 h. Data were analyzed with FlowJo.

Antibody protection of Gal-9-induced T-cell death assay

T cells were expanded from human PBMCs by stimulation for 5 to 7 days with anti-CD3 antibody OKT3 and incubated with 2 μg/ml Gal-9 in the presence of 1 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml control mouse IgG or anti-Gal-9 antibodies. After overnight culture, cells were stained with FITC-labeled CD4 antibody and phycoerythrin-labeled CD8 antibody. Quantification of viable CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with counting beads was performed as described previously (6). Briefly, 1 × 104 BD FACS AccuDrop Beads (BD Biosciences) were added per sample, and a fixed number of 3000 bead events were acquired for each sample. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed with FlowJo.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell viability was determined by MTS or CCK-8 assay. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with 2 μg/ml Gal-9 in the presence of anti-Gal-9 antibodies overnight. After that, 20 μl MTS or 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 to 4 h. The absorbance at 450 to 490 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Beckman Coulter). EC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc).

T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity assay

A375 cancer cells were engineered to express FcγR2a and nuclear mCherry red fluorescent protein by lentiviral transduction. For cytotoxicity assay, 2000 tumor cells were cultured overnight in Nunclon Sphera–treated, U-shaped-bottom 96-well ultralow attachment microplate (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalog no.: 174925) to form spheroids. PBMCs (10,000 cells), anti-CD3 (100 ng/ml), Gal-9 (2 μg/ml), and control IgG2a or Gal-9 antibodies (10 μg/ml) were then added. The survival of tumor cells was monitored by IncuCyte over a period of 5 days.

Statistical analysis

Unless noted otherwise, data visualization and statistical analyses were performed using Prism 9.3.1 (GraphPad). p Values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical tests are specified in figure legends. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; and ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Data availability

The Gal-9 mAbs were developed by the authors and are not commercially available. Small aliquot can be provided by the corresponding authors upon request. A material transfer agreement from MD Anderson Cancer Center is required to release for industrial development.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank MD Anderson Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility for the production of Gal-9 mAbs. This work was supported by Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project, the National Institutes of Health (grant no.: CCSG CA016672), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (grant no.: RP160710), and the Patel Memorial Breast Cancer Endowment Fund.

Author contributions

R. Y., L. S., C.-F. L., Y.-H. W., W. X., and B. L. methodology; R. Y., L. S., C.-F. L., Y.-H. W., W. X., and B. L. formal analysis; R. Y., L. S., C.-F. L., W. X., and B. L. investigation; Y.-Y. C. resources; R. Y., L. S., and M.-C. H. writing–original draft; R. Y., L. S., and M.-C. H. supervision.

Funding and additional information

This work was funded in part by the following: Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (grant no.: MOST110-2639-B-039-001-ASP; to M.-C. H.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos.: 82172687 and 81972186; to L. S.); Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (grant no.: 20JCYBJC00360; to L. S.); Health Commission of Tianjin (grant no.: TJWJ2021MS002; to L. S.); China Scholarship Council (to L. S.); The Odyssey Fellowship from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (to C.-F. L.); and The University of Texas MD Anderson-China Medical University and Hospital Sister Institution Fund (to M-C. H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Edited by Peter Cresswell

Contributor Information

Riyao Yang, Email: ryyangster@gmail.com.

Linlin Sun, Email: lsun1@tmu.edu.cn.

Mien-Chie Hung, Email: mhung@cmu.edu.tw.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Kroemer G., Zitvogel L. Immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218 doi: 10.1084/jem.20201979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Miguel M., Calvo E. Clinical challenges of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang R.-Y., Rabinovich G.A., Liu F.-T. Galectins: Structure, function and therapeutic potential. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2008;10:e17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiemann S., Baum L.G. Galectins and immune responses-just how do they do those things they do? Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016;34:243–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirabayashi J., Hashidate T., Arata Y., Nishi N., Nakamura T., Hirashima M., Urashima T., Oka T., Futai M., Muller W.E.G., Yagi F., Kasai K. Oligosaccharide specificity of galectins: A search by frontal affinity chromatography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1572:232–254. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang R., Sun L., Li C.-F., Wang Y.-H., Yao J., Li H., Yan M., Chang W.-C., Hsu J.-M., Cha J.-H., Hsu J.L., Chou C.-W., Sun X., Deng Y., Chou C.-K., et al. Galectin-9 interacts with PD-1 and TIM-3 to regulate T cell death and is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:832. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21099-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu C., Anderson A.C., Schubart A., Xiong H., Imitola J., Khoury S.J., Zheng X.X., Strom T.B., Kuchroo V.K. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1245–1252. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daley D., Mani V.R., Mohan N., Akkad N., Ochi A., Heindel D.W., Lee K.B., Zambirinis C.P., Balasubramania Pandian G.S.D., Savadkar S., Torres-Hernandez A., Nayak S., Wang D., Hundeyin M., Diskin B., et al. Dectin 1 activation on macrophages by galectin 9 promotes pancreatic carcinoma and peritumoral immune tolerance. Nat. Med. 2017;23:556–567. doi: 10.1038/nm.4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu C., Thalhamer T., Franca R.F., Xiao S., Wang C., Hotta C., Zhu C., Hirashima M., Anderson A.C., Kuchroo V.K. Galectin-9-CD44 interaction enhances stability and function of adaptive regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2014;41:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madireddi S., Eun S.-Y., Mehta A.K., Birta A., Zajonc D.M., Niki T., Hirashima M., Podack E.R., Schreiber T.H., Croft M. Regulatory T cell–mediated suppression of inflammation induced by DR3 signaling is dependent on galectin-9. J. Immunol. 2017;199:2721–2728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okoye I., Xu L., Motamedi M., Parashar P., Walker J.W., Elahi S. Galectin-9 expression defines exhausted T cells and impaired cytotoxic NK cells in patients with virus-associated solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu L., Guan R., Yang H., Zhou Y., Hong W., Ma L., Zhao G., Yu M. Assessment of the expression of the immune checkpoint molecules PD-1, CTLA4, TIM-3 and LAG-3 across different cancers in relation to treatment response, tumor-infiltrating immune cells and survival. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;147:423–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X., Sun L., Jing D., Xu G., Zhang J., Lin L., Zhao J., Yao Z., Lin H. Galectin-9 expression predicts favorable clinical outcome in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:452. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z., Han H., He X., Li S., Wu C., Yu C., Wang S. Expression of the galectin-9-tim-3 pathway in glioma tissues is associated with the clinical manifestations of glioma. Oncol. Lett. 2016;11:1829–1834. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan F., Ming H., Wang Y., Yang Y., Yi L., Li T., Ma H., Tong L., Zhang L., Liu P., Li J., Lin Y., Yu S., Ren B., Yang X. Molecular and clinical characterization of Galectin-9 in glioma through 1,027 samples. J. Cell Physiol. 2020;235:4326–4334. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seifert A.M., Reiche C., Heiduk M., Tannert A., Meinecke A.-C., Baier S., von Renesse J., Kahlert C., Distler M., Welsch T., Reissfelder C., Aust D.E., Miller G., Weitz J., Seifert L. Detection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with galectin-9 serum levels. Oncogene. 2020;39:3102–3113. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1186-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavares L.B., Silva-Filho A.F., Martins M.R., Vilar K.M., Pitta M.G.R., Rêgo M.J.B.M. Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma have high serum galectin-9 levels. Pancreas. 2018;47:e59–e60. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enninga E.A.L., Nevala W.K., Holtan S.G., Leontovich A.A., Markovic S.N. Galectin-9 modulates immunity by promoting Th2/M2 differentiation and impacts survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:429–441. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikushige Y., Miyamoto T., Yuda J., Jabbarzadeh-Tabrizi S., Shima T., Takayanagi S.I., Niiro H., Yurino A., Miyawaki K., Takenaka K., Iwasaki H., Akashi K. A TIM-3/Gal-9 autocrine stimulatory loop drives self-renewal of human myeloid leukemia stem cells and leukemic progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonçalves Silva I., Rüegg L., Gibbs B.F., Bardelli M., Fruehwirth A., Varani L., Berger S.M., Fasler-Kan E., Sumbayev V.V. The immune receptor Tim-3 acts as a trafficker in a Tim-3/galectin-9 autocrine loop in human myeloid leukemia cells. OncoImmunology. 2016;5 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1195535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lhuillier C., Barjon C., Niki T., Gelin A., Praz F., Morales O., Souquere S., Hirashima M., Wei M., Dellis O., Busson P. Impact of exogenous galectin-9 on human T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:16797–16811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.661272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei S.C., Duffy C.R., Allison J.P. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1069–1086. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabatos-Peyton C.A., Nevin J., Brock A., Venable J.D., Tan D.J., Kassam N., Xu F., Taraszka J., Wesemann L., Pertel T., Acharya N., Klapholz M., Etminan Y., Jiang X., Huang Y.-H., et al. Blockade of Tim-3 binding to phosphatidylserine and CEACAM1 is a shared feature of anti-Tim-3 antibodies that have functional efficacy. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1385690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H.-Y., Wu Y.-F.Y.-H., Chou F.-C., Wu Y.-F.Y.-H., Yeh L.-T., Lin K.-I., Liu F.-T., Sytwu H.-K. Intracellular galectin-9 enhances proximal TCR signaling and potentiates autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 2020;204:1158–1172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L., Wang W., Koide A., Bolen J., Miller G., Koide S. Immunology. American Association for Cancer Research; Philadelphia, PA: 2019. Abstract 1551: First in class immunotherapy targeting Galectin-9 promotes T-cell activation and anti-tumor response against pancreatic cancer and other solid tumors. pp. 1551–1551. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lhuillier C., Barjon C., Baloche V., Niki T., Gelin A., Mustapha R., Claër L., Hoos S., Chiba Y., Ueno M., Hirashima M., Wei M., Morales O., Raynal B., Delhem N., et al. Characterization of neutralizing antibodies reacting with the 213-224 amino-acid segment of human galectin-9. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertino P., Premeaux T.A., Fujita T., Haun B.K., Marciel M.P., Hoffmann F.W., Garcia A., Yiang H., Pastorino S., Carbone M., Niki T., Berestecky J., Hoffmann P.R., Ndhlovu L.C. Targeting the C-terminus of galectin-9 induces mesothelioma apoptosis and M2 macrophage depletion. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:1601482. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1601482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gooden M.J., Wiersma V.R., Samplonius D.F., Gerssen J., van Ginkel R.J., Nijman H.W., Hirashima M., Niki T., Eggleton P., Helfrich W., Bremer E. Galectin-9 activates and expands human T-helper 1 cells. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagahara K., Arikawa T., Oomizu S., Kontani K., Nobumoto A., Tateno H., Watanabe K., Niki T., Katoh S., Miyake M., Nagahata S., Hirabayashi J., Kuchroo V.K., Yamauchi A., Hirashima M. Galectin-9 increases Tim-3+ dendritic cells and CD8+ T cells and enhances antitumor immunity via galectin-9-Tim-3 interactions. J. Immunol. 2008;181:7660–7669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv K., Zhang Y., Zhang M., Zhong M., Suo Q. Galectin-9 promotes TGF-β1-dependent induction of regulatory T cells via the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2013;7:205–210. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golden-Mason L., McMahan R.H., Strong M., Reisdorph R., Mahaffey S., Palmer B.E., Cheng L., Kulesza C., Hirashima M., Niki T., Rosen H.R. Galectin-9 functionally impairs natural killer cells in humans and mice. J. Virol. 2013;87:4835–4845. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01085-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen P., Zhang L., Zhang W., Sun C., Wu C., He Y., Zhou C. Galectin-9-based immune risk score model helps to predict relapse in stage I–III small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y., Guan C., Zhang X. Galectin-9 as a prognostic biomarker in small cell lung cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2018 doi: 10.21037/21680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang T., Wang X., Wang F., Feng E., You G. Galectin-9: A predictive biomarker negatively regulating immune response in glioma patients. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e455–e462. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sideras K., Biermann K., Yap K., Mancham S., Boor P.P.C., Hansen B.E., Stoop H.J.A., Peppelenbosch M.P., van Eijck C.H., Sleijfer S., Kwekkeboom J., Bruno M.J. Tumor cell expression of immune inhibitory molecules and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte count predict cancer-specific survival in pancreatic and ampullary cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;141:572–582. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y., Xue S., Hao Q., Liu F., Huang W., Wang J. Galectin-9 and PSMB8 overexpression predict unfavorable prognosis in patients with AML. J. Cancer. 2021;12:4257–4263. doi: 10.7150/jca.53686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imaizumi, T., Kumagai, M., Sasaki, N., Kurotaki, H., Mori, F., Seki, M., Nishi, N., Fujimoto, K., Tanji, K., Shibata, T., Tamo, W., Matsumiya, T., Yoshida, H., Cui, X.-F., Takanashi, S., Hanada, K., Okumura, K., Yagihashi, S., Wakabayashi, K., Nakamura, T., Hirashima, M., and Satoh, K. Interferon-gamma stimulates the expression of galectin-9 in cultured human endothelial cells [PubMed]

- 38.Gibney G.T., Weiner L.M., Atkins M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e542–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jochems C., Schlom J. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells and prognosis: The potential link between conventional cancer therapy and immunity. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2011;236:567–579. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trujillo J.A., Sweis R.F., Bao R., Luke J.J. T cell–inflamed versus non-T cell–inflamed tumors: A conceptual framework for cancer immunotherapy drug development and combination therapy selection. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018;6:990–1000. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Q., Munger M.E., Veenstra R.G., Weigel B.J., Hirashima M., Munn D.H., Murphy W.J., Azuma M., Anderson A.C., Kuchroo V.K., Blazar B.R. Coexpression of Tim-3 and PD-1 identifies a CD8+ T-cell exhaustion phenotype in mice with disseminated acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:4501–4510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-310425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun L., Li C.-W.W., Chung E.M., Yang R., Kim Y.-S.S., Park A.H., Lai Y.-J.J., Yang Y., Wang Y.-H.H., Liu J., Qiu Y., Khoo K.-H.H., Yao J., Hsu J.-M.M.J.L., Cha J.-H.H., et al. Targeting glycosylated PD-1 induces potent anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2298–2310. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Gal-9 mAbs were developed by the authors and are not commercially available. Small aliquot can be provided by the corresponding authors upon request. A material transfer agreement from MD Anderson Cancer Center is required to release for industrial development.