Abstract

Thirty-two vanB glycopeptide-resistant enterococci (28 Enterococcus faecium and 4 Enterococcus faecalis) were collected from hospitalized patients in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, and Aberdeen, Scotland, and the vanB element in each was compared to vanB1 of E. faecalis strain ATCC 51299. HhaI digestion of PCR fragments of the vanB ligase gene was used to identify vanB subtypes. All E. faecium isolates were vanB2, and all E. faecalis isolates were vanB1. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of a 5,180-bp vanSB-vanXB long-PCR fragment of the vanB cluster showed the loss of HaeII restriction sites in vanSB, vanW, and vanXB in strains containing a vanB2 ligase gene. Partial sequences of genes in the vanB2 cluster for two genomically distinct Scottish isolates were >99.8% identical to each other. vanSB2, vanXB2, and vanB2 sequences differed at the nucleotide level from those of vanSB, vanXB, and vanB by 4.2, 4.6, and 4.8%, respectively. The vanB2 resistance element appears to be widespread among VanB glycopeptide-resistant E. faecium strains isolated in Scottish hospitals.

Glycopeptide-resistant enterococci (GRE) are increasingly being reported (15), causing great concern in the hospital environment. Acquired glycopeptide resistance is mediated by a complex, well-controlled cluster of genes, of which vanA and vanB are the most common. Both the vanA and vanB resistance clusters comprise seven genes: vanR, vanS, vanH, vanA, vanX, vanY, and vanZ and vanRB, vanSB, vanYB, vanW, vanHB, vanB, and vanXB, respectively (2).

The vanA gene cluster appears to be universally carried on transposon Tn1546 or similarly organized elements, often containing additional insertion sequence (IS) elements (1, 13, 14, 18, 26). Similarly, the vanB gene cluster is believed to be part of a larger element. Conjugative transfer of chromosomal vanB resistance is associated with the movement of 90- to 250-kb DNA fragments (6, 21, 22), and two distinct vanB-containing transposons have been described, Tn1547 (22) and Tn5382 (6).

The seven genes of the vanB cluster appear to be conserved within the strains studied to date, and unlike vanA clusters, an IS element has been detected within the cluster in only a single isolate (7). However, while the vanB gene clusters appear to be structurally conserved, heterogeneity at the nucleotide level has been reported. Based on sequence variability in the vanB ligase gene, three subtypes have been described, termed vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 (7, 11, 19). Furthermore, Dahl et al. (7) showed that the sequence of the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region varied among vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 isolates.

This paper describes a PCR-based approach to identify the vanB subtype and to assess variation in the elements mediating vanB-type glycopeptide resistance in enterococci isolated in Scotland.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 33 isolates were collected for this study (Table 1). Of these, 32 were isolated between 1995 and 1998 from hospitalized patients in Scotland, including 20 in Glasgow (17), 6 in Edinburgh (5), 5 in Dundee, and 1 in Aberdeen. The 20 Glasgow isolates were selected from a collection of 138 vanB Enterococcus faecium isolates (17), based on varied levels of resistance to vancomycin, ampicillin, tetracycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin, and included 4 clinical and 16 fecal-screen strains isolated over a 30-month period in three different hospitals. Enterococcus faecalis isolate ATCC 51299 from the United States was also included (24).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of vanB GRE isolates

| Straina | Species | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

Susceptibilityc

|

PFGE type | vanB subtypef | L-PCR-HaeII profile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VANg | TEC | AMP | TET | STR | GEN | CIP | |||||

| G-003 | E. faecium | 32 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | S | A1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-097 | E. faecium | 16 | <0.25 | R | R | R | R | S | A1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-105 | E. faecium | 32 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | S | A1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-112 | E. faecium | 8 | 0.25 | R | R | R | R | S | A1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-031 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | S | A1e | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-076 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.25 | R | S | R | R | S | A1e | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-060 | E. faecium | 8 | <0.25 | R | R | R | R | S | A2 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-153 | E. faecium | 8 | <0.25 | S | R | R | R | S | A2e | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-138 | E. faecium | 16 | <0.25 | R | R | R | R | S | A4 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-142 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | R | HLR | S | A5 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-144 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | S | A11 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-015 | E. faecium | 8 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | S | B4 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-051 | E. faecium | 128 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | S | C1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-009 | E. faecium | 32 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | S | D1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-013 | E. faecium | 8 | <0.25 | S | S | R | R | S | E1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-014 | E. faecium | 8 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | S | F1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-102 | E. faecium | 8 | 1 | R | R | HLR | R | S | G1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-116b | E. faecium | 256 | 32 | R | S | R | HLR | R | H1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-075 | E. faecium | 8 | <0.25 | R | S | R | R | R | V1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| G-139 | E. faecium | 16 | <0.25 | R | S | R | R | R | W1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| D-002 | E. faecium | 8 | 0.5 | R | S | R | R | S | J1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| D-003 | E. faecium | 8 | 1 | S | S | R | R | S | J1e | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| D-009 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | R | K1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| D-004 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | R | M1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| D-005 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | R | R | R | M1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| A-004 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | S | P1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| E-031 | E. faecium | 32 | 0.5 | R | S | HLR | R | S | N1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| E-015 | E. faecium | 16 | 0.5 | R | R | HLR | R | R | S1 | vanB2 | RFLP-2 |

| E-023 | E. faecalis | 32 | 0.25 | S | S | R | HLR | S | R1 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 |

| E-024 | E. faecalis | 32 | 0.25 | S | S | HLR | R | S | T1 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 |

| E-018 | E. faecalis | 32 | 0.5 | S | S | HLR | HLR | S | L1 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 |

| E-022 | E. faecalis | 16 | 0.25 | S | S | HLR | HLR | S | L1 | vanB1 | RFLP-1 |

| ATCC 51299 | E. faecalis | 16 | 0.5 | S | S | Rd | HLR | S | L1e | vanB1 | RFLP-1 |

Scottish isolates have been given prefixes to indicate their origins: G, Glasgow; D, Dundee; E, Edinburgh; and A, Aberdeen. ATCC 51299 was isolated in the United States (24).

Carries both vanA and vanB resistance elements (17).

R, resistant; S, susceptible; HLR, high-level resistance. The breakpoints are those in Nelson et al. (17).

Reported by Swenson et al. (24) to have high-level streptomycin resistance.

Strain with the same PFGE pattern as another isolate(s) but a different level of susceptibility to ampicillin, tetracycline, or streptomycin.

Determined by HhaI restriction pattern and sequence analysis of B1-B2 vanB PCR fragments.

VAN, vancomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; AMP, ampicillin; TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; GEN, gentamicin; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

The isolates were identified to the species level by PCR amplification of intergenic rRNA spacer regions and biochemistry as described previously (17). All of the isolates showed resistance to vancomycin (MIC > 8 μg/ml) while remaining susceptible to teicoplanin (MIC < 2 μg/ml), in accordance with the VanB phenotype, and produced a 635-bp product in amplification reactions with primers B1 and B2, indicative of the presence of the vanB ligase gene (8). Ampicillin, tetracycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin susceptibility testing was performed, and the isolates were defined as susceptible or resistant as described previously (17).

PFGE typing.

All isolates were assigned a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) type based on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns of SmaI-digested DNA as described previously (17). Strains with one to six band differences were regarded as related, and those with seven or more band differences were regarded as unrelated.

Preparation of genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA for use as a template in PCRs was isolated by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide extraction method of Wilson (27) as modified by Handwerger et al. (13).

PCR amplification of van genes.

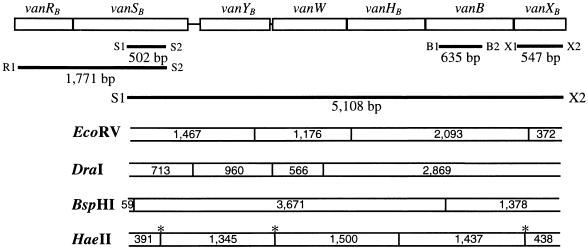

A fragment of the vanB ligase gene was amplified using primers B1 and B2 described by Dutka-Malen et al. (8). Primers were designed to amplify fragments of the vanSB and vanXB genes and regions between genes (Fig. 1) from the sequence of the vanB gene cluster of the E. faecalis vanB1 strain V583 and are listed in Table 2.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of vanB gene cluster of strain V583. PCR fragments generated from primers used in this study and the restriction profile of an L-PCR fragment are shown. ∗, HaeII sites that are not present in vanB2 strains. Sizes are given in base pairs.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for the amplification of fragments of the vanB gene cluster

Fragments smaller than 2 kb were amplified from approximately 100 ng of template DNA. The reaction mixtures and amplification conditions were as described previously (17).

L-PCR.

Fragments (5,108 bp) of vanSB-vanXB were amplified from approximately 500 ng of template DNA with primers S1 and X2 using the Expand long-template PCR (L-PCR) system (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). The reaction mixtures were prepared in buffer 1 in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications. The amplification conditions were 94°C for 2 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 5 min; 20 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 5 min with the elongation time increased by 20 s each cycle; and one cycle of 68°C for 7 min.

RFLP analysis.

All restriction enzymes were supplied by Promega (Madison, Wis.), except BspHI (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom), and were used in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications.

Sequencing.

Cycle sequencing of PCR fragments was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions using the DYEnamic ET terminator cycle-sequencing premix kit (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). The ABI 373 DNA-sequencing system was used to sequence each template from one strand only.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences generated in this study have been entered into the EMBL database. The accession numbers are AJ272437 (E. faecium D-002 vanSB) and AJ272436 (E. faecium D-002 vanXB). All sequences were aligned with that of E. faecalis strain V583 (9), GenBank accession number U35369. All position numbers given refer to this sequence.

RESULTS

In this study, the elements mediating VanB glycopeptide resistance in 32 enterococci isolated from Scottish hospitals were analyzed and compared to strain ATCC 51299 (24) and the vanB gene cluster of strain V583 (9), both from the United States.

Twenty-eight (88%) of the 32 Scottish isolates were identified as E. faecium; the remaining four (all isolates from Edinburgh) were identified as E. faecalis. Nineteen (59%) of 32 were distinct by PFGE typing. Ten of the Glasgow isolates were identical or related to the A1 type. Some of the isolates with the same PFGE type differed in their levels of susceptibility to ampicillin, tetracycline, or streptomycin (Table 1). These related isolates were included in the study, as previous workers have noted that different vanA elements may be carried in enterococci with the same PFGE pattern (12, 25) and we were interested in determining if similar phenomena may occur in vanB isolates. Furthermore, a single strain of enterococci can lose and acquire different van resistance elements over time (23, 29). The observation that two of the four Scottish E. faecalis isolates had SmaI patterns (PFGE type L1) identical to that of E. faecalis strain ATCC 52199 was of interest.

Identification of vanB subtype.

The vanB ligase gene of each isolate was amplified using the primers B1 and B2. All gave a 635-bp product. Analysis of vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 ligase gene sequences in the GenBank database suggested the different subtypes could be partially distinguished by RFLP analysis of the vanB PCR product. An A → G nucleotide substitution at position 5454 would result in the creation of an HhaI site in vanB2 isolates, while a C → T substitution at position 5618 would result in the loss of an HhaI site in vanB2 isolates (Fig. 2). Thus, HhaI digestion of the 635-bp B1-B2 vanB PCR fragment would give bands of 479 and 159 bp for vanB1 and vanB3 and bands of 313 and 322 bp for vanB2. By vanB-HhaI analysis, strain ATCC 51299 and the four E. faecalis isolates from Edinburgh gave vanB1 or vanB3 patterns while all E. faecium isolates were vanB2 (Fig. 3; the 313- and 322-bp bands appear as a single band).

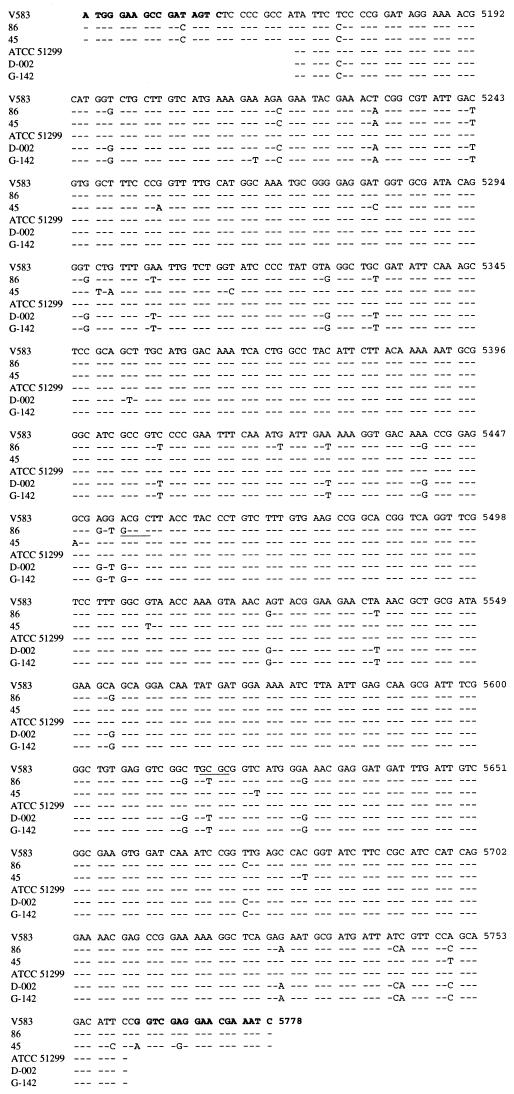

FIG. 2.

Comparison of DNA sequences of vanB genes from GRE isolates to positions 5144 to 5778 of the vanB1 sequence of strain V583. Strains 86 and 45 are vanB2 and vanB3, respectively (19). Primers B1 and B2 are shown in boldface. HhaI restriction sites are underlined. The dashes indicate identical sequence.

FIG. 3.

HhaI digestion of 635-bp B1-B2 vanB PCR fragments. Lanes: 1, G-142; 2, D-002; 3, A-004; 4, E-015; 5, E-023; 6, ATCC 51299; 7, 100-bp DNA ladder (Promega). The image was generated with Adobe Photoshop 4.0.

The B1-B2 vanB PCR fragments from the five non-vanB2 strains (ATCC 51299, E-018, E-022, E-023, and E-024) and two vanB2 isolates (G-142 and D-002) were sequenced. Over 591 bp, strain ATCC 51299 was identical to vanB1 strain V583 (Fig. 2). The four non-vanB2 isolates from Edinburgh likewise had sequences identical to that of V583 (data not shown), indicating that all were vanB1. The vanB sequences of strains G-142 and D-002 showed 27 (4.6%) nucleotide differences from strain V583. The G-142 and D-002 sequences were identical to that of vanB2 strain 86 (19), verifying the presence of the vanB2 subtype as determined by vanB-HhaI profiles.

Characterization of vanB resistance elements.

To further characterize the glycopeptide resistance elements in our isolates, L-PCR and PCR mapping were used. Primers R1 and S2 were used to amplify vanRB-vanSB, and L-PCR was used to amplify a 5,108-bp fragment of vanSB-vanXB. L-PCR products were digested with EcoRV, BspHI, and DraI. Additionally, amplified fragments were digested with HaeII, as analysis of the vanB3 sequence suggested that vanB3 isolates would have an additional HaeII site within the vanB ligase gene (downstream of primer B2).

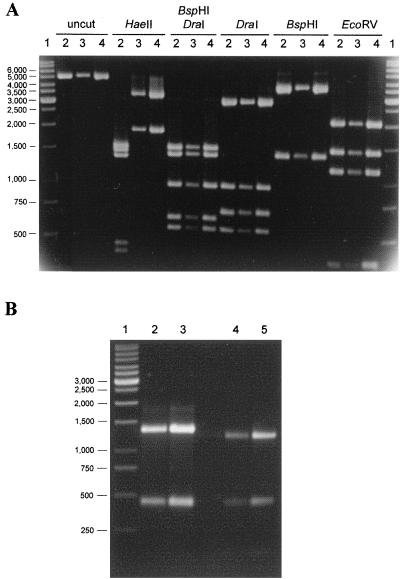

ATCC 51299 and the four E. faecalis isolates gave bands expected for vanB1 strain V583 when digested with EcoRV, BspHI, and DraI (Fig. 4A). Digestion with HaeII gave the five bands expected for strain V583 (Fig. 1), confirming the presence of a vanB1 ligase gene, not vanB3 (the five-band pattern is referred to as RFLP-1 [Table 1]).

FIG. 4.

PCR fragments and RFLP profiles of representative vanB1 and vanB2 isolates. The image was generated with Adobe Photoshop 4.0. (A) S1-X2 vanSB-vanXB L-PCR fragments and resulting RFLP profiles. Lanes: 1, GeneRuler 1-kb DNA ladder (MBI Fermentas); 2, ATCC 51299; 3, D-002; 4, G-142. (B) BspHI digestion of 1,771-bp R1-S2 vanRB-vanSB PCR fragments. Lanes: 1, GeneRuler 1-kb DNA ladder; 2, E-023; 3, ATCC 51299; 4, G142; 5, D-002.

All E. faecium isolates were identical to V583 by EcoRV, BspHI, and DraI digestion, but their HaeII digestion patterns differed. In these isolates, HaeII digestion gave two bands instead of five (RFLP-2 [Table 1]), suggesting the loss of three HaeII sites (Fig. 4A). DraI/HaeII double digests indicated HaeII sites were lost in vanSB, vanW, and vanXB (data not shown).

Dahl et al. (7) described two RFLP patterns based on BspHI digestion of vanRB-vanXB L-PCR fragments. Strains with the vanB2 gene all had an additional BspHI site in vanRB-vanSB. To determine if our vanB2 strains had the same additional BspHI site, R1-S2 PCR fragments were digested with this enzyme. All vanB2 isolates had this additional site, and the sizes of the bands suggested the additional site was within the vanSB gene (Fig. 4B).

Sequencing of vanSB and vanXB genes.

L-PCR-HaeII profiles revealed the loss of HaeII sites in the vanSB and vanXB genes. To further characterize the alterations in these genes, primers were designed to amplify fragments of the two genes (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Sequence was generated from S1-S2 and X1-X2 fragments of ATCC 51299, G-142, and D-002.

Over 430 bp of the S1-S2 PCR fragment, ATCC 51299 was identical to V583 (Fig. 5). D-002 was identical to G-142 and showed 18 nucleotide changes (4.2%) and 4 amino acid changes in 142 (2.8%) compared to strain V583. The substitution G → A at position 1865 resulted in the loss of an HaeII site. The vanSB gene of the vanB2 gene cluster has been termed vanSB2.

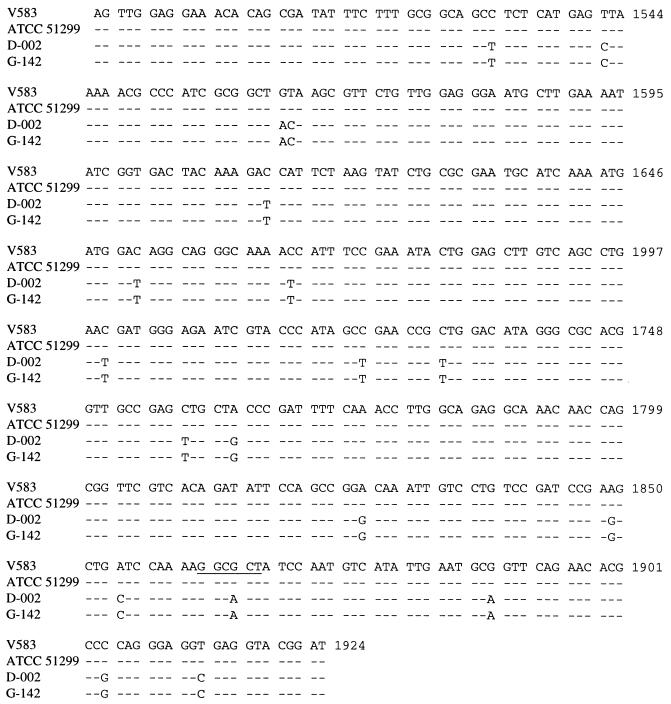

FIG. 5.

Comparison of DNA sequences of vanSB genes from GRE isolates to positions 1495 to 1924 of the vanSB sequence of strain V583. The HaeII restriction site is underlined. The dashes indicate identical sequence.

Additionally, S1-S2 PCR fragments from the remaining 30 strains were digested with AluI and Sau3AI (not shown), both of which give different bands for vanSB and vanSB2 fragments. The resulting RFLP profiles suggested that all vanB1 isolates were identical to V583 at these sites and all vanB2 isolates had the same nucleotide sequence changes at these sites as G-142 and D-002.

Likewise, X1-X2 vanXB PCR fragments were sequenced. Over 476 bp, ATCC 51299 was identical to V583 except for two nucleotide changes: C → G at position 6179 and G → C at position 6180 (Fig. 6). D-002 differed from V583 by 22 nucleotides (4.8%) (including the two differences seen in ATCC 51299) and 7 amino acids in 158 (4.4%). G-142 was identical to D-002 except for a unique nucleotide change, C → G at position 6271, which resulted in an additional amino acid change. The C → T substitution at position 6146 in G-142 and D-002 resulted in the loss of an HaeII site. The vanXB gene of the vanB2 gene cluster has been termed vanXB2.

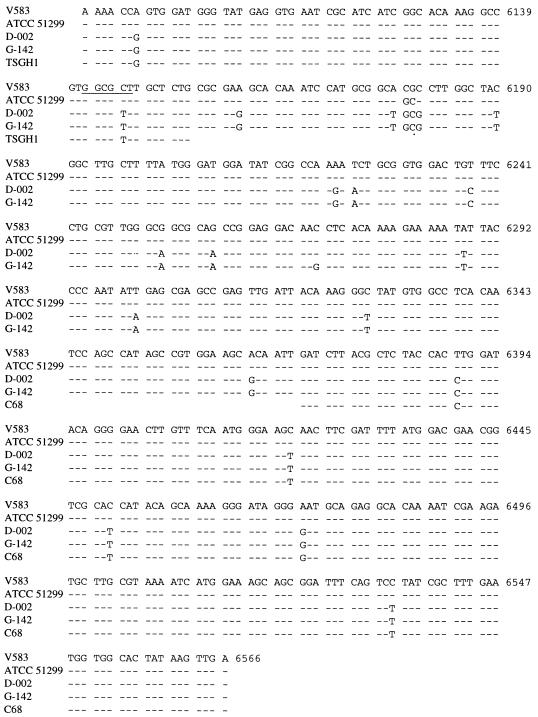

FIG. 6.

Comparison of DNA sequences of vanXB genes from GRE isolates to positions 6091 to 6566 of the vanXB sequence of strain V583. The HaeII restriction site is underlined. The dashes indicate identical sequence.

Two other sequences available in GenBank give partial sequences of the vanXB gene. Alignment of these sequences with ours shows the same differences as in G-142 and D-002 (Fig. 6). Strain C68 (a U.S. isolate in which the vanB gene cluster is contained within Tn5382 [6]) shows five nucleotide differences from V583 in a 196-bp overlap. Strain TSGH1 from Taiwan (GenBank accession no. U81452) shows two nucleotide differences in 64 bp.

DISCUSSION

VanB GRE have been reported as an important cause of infection in a number of hospitals in the United States (4, 16, 20) and recently in a Scottish hospital (17). While the structural diversity within vanA glycopeptide resistance elements has been the subject of numerous studies, there have been relatively few studies of the vanB elements, and most have focused on the vanB ligase gene. A study by Dahl et al. (7) has examined the vanB gene cluster from vanRB-vanXB, showing the element to be structurally identical in 16 of 17 isolates but with nucleotide heterogeneity in the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region and the vanB gene. In this study we report the development of PCR mapping techniques and RFLP analysis to examine diversity in vanB elements.

The PCR RFLP (vanB-HhaI) method proved useful for the identification of vanB subtypes, particularly vanB2. The vanB1 and vanB3 subtypes could not be distinguished by this method. Primers could be designed to allow amplification of a larger fragment of the vanB ligase gene that would include the additional HaeII site within the vanB3 gene. HhaI/HaeII double digests of such a vanB fragment would allow the distinction of vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3 genes. However, at present sequence analysis of the vanB gene of potential vanB1 and vanB3 isolates is recommended. When more studies have been done with a larger number of vanB strains, preferably including L-PCR analysis, the true extent of variation within the vanB subtypes may be better understood, allowing the development of methods to distinguish all subtypes.

Dahl et al. (7) suggest caution when choosing primers for vanB ligase amplification (which is the main molecular method of genotypic determination of van type in the laboratory). We found the B1-B2 primers of Dutka-Malen et al. (8) suitable for amplification of both vanB1 and vanB2 genes despite one mismatch in primer B1 in the vanB2 gene and two in B2 (Fig. 2). As we do not have any vanB3 isolates, we do not know if these primers would be suitable for the amplification of vanB3 fragments. The vanB3 sequence is identical to vanB2 for B1 but contains an additional mismatch at the 3′ end of B2. GRE with a VanB phenotype that did not produce an amplification product with vanB primers have been reported (3). This suggests the primers may not have been suitable for the amplification of all vanB subtypes or that other, as yet undetected subtypes of vanB exist. Alternatively, there may be different gene clusters that give a VanB phenotype, for example, the newly identified vanE element (10).

In this study, vanB2 was associated with E. faecium and vanB1 was associated with E. faecalis, although work by other investigators (7, 11, 19) suggests the resistance elements are not species specific. No other vanB subtypes were identified in this study. vanB2 elements have now been detected worldwide, including the United States, Europe, and Taiwan (6, 11, 19; GenBank accession no. U81452). To date, vanB3 has been detected only in a single U.S. isolate (19).

The majority of European vanB enterococci appear to carry the vanB2 element. Dahl et al. (7) found a vanB2 element in seven (88%) of eight European isolates, including strains from Sweden, Norway, Germany, and the United Kingdom, compared to only two (22%) of nine U.S. isolates. Likewise, vanB2 was detected in 88% of Scottish vanB enterococci in this study. vanB2 also appears to be the major type in Finland (23).

We have shown that vanB2 glycopeptide resistance elements differ from vanB1 elements by nucleotide heterogeneity in the vanSB and vanXB genes. The loss of a HaeII restriction site in vanW shown in this study, together with previous reports of heterogeneity in vanB (7, 11, 19), vanHB (GenBank accession no. U81452), and the vanSB-vanYB intergenic region (7), suggests all genes in the vanB2 cluster may differ from those in the vanB1 cluster.

vanB has been shown to be associated with the transfer of different-size fragments of DNA (ranging from 90 to 250 kb), which suggests the gene cluster may be contained within different structures. A number of potential elements have been described. A 64-kb composite transposon (Tn1547), bounded by IS256-like and IS16 elements, has been identified in the transposition of vanB from chromosome to plasmid DNA (22), although this element was not involved in conjugative chromosome-to-chromosome transfer. A 55-MDa transferable plasmid containing both vanB and aac6′aph2" gentamicin resistance genes has been reported (28). vanB has been associated with a 27-kb conjugative transposon (Tn5382) which may be part of a 160-kb element containing both vanB and high-level ampicillin resistance genes (6). It would be of interest to know if the different vanB subtypes are associated with different elements. Partial sequence of the vanXB gene of E. faecium strain C68 (a U.S. isolate which harbors Tn5382) (6) suggests this strain carries a vanB2 element. Future studies will examine whether Tn5382 is present in Scottish vanB2 isolates.

This study describes new techniques for the identification and characterization of vanB glycopeptide resistance elements. Previous observations of sequence variability in the gene cluster have been confirmed and extended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Scottish Office Department of Health, grant reference number K/MRS/50/C2607.

We thank R. Nelson of the Western Infirmary, Glasgow, United Kingdom; A. Brown of Edinburgh University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom; G. Phillips of Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, United Kingdom; and T. Reid of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, United Kingdom for providing strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Molinas C, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1546, a Tn3-related transposon conferring glycopeptide resistance by synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:117–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.117-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur M, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell J M, Paton J C, Turnidge J. Emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Australia: phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2187–2190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2187-2190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce J M, Opal S M, Chow J W, Zervos M J, Potterbynoe G, Sherman C B, Romulo R L C, Fortna S, Medeiros A A. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium with transferable vanB class vancomycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1148-1153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown A R, Amyes S G B, Paton R, Plant W D, Stevenson G M, Winney R J, Miles R S. Epidemiology and control of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in a renal unit. J Hosp Infect. 1998;40:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carias L L, Rudin S D, Donskey C J, Rice L B. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4426–4434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4426-4434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl K H, Simonsen G S, Olsvik O, Sundsfjord A. Heterogeneity in the vanB gene cluster of genomically diverse clinical strains of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:24–27. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.24-27.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evers S, Courvalin P. Regulation of vanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the vanSB-vanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1302-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fines M, Perichon B, Reynolds P, Sahm D F, Courvalin P. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2161–2164. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold H S, Unal S, Cercenado E, Thauvin-Eliopoulos C, Eliopoulos G M, Wennersten C B, Moellering R C. A gene conferring resistance to vancomycin but not teicoplanin in isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium demonstrates homology with vanB, vanA, and vanC genes of enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1604–1609. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goossens H, Descheemaeker P, Chapelle S, Leven M, Vandamme P, Devriese L A. Comparison of human and animal vanA Enterococcus faecium in Belgium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5(Suppl. 3):122. . (Abstract P141.) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handwerger S, Skoble J, Discotto L F, Pucci M J. Heterogeneity of the vanA gene cluster in clinical isolates of enterococci from the northeastern United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:362–368. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen L B, Ahrens P, Dons L, Jones R N, Hammerum A M, Aarestrup F M. Molecular analysis of Tn1546 in Enterococcus faecium isolated from animals and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:437–442. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.437-442.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald L C, Jarvis W R. The global impact of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1997;10:304–309. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno F, Grota P, Crisp C, Magnon K, Melcher G P, Jorgensen J H, Patterson J E. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium during its emergence in a city in Southern Texas. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1234–1237. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson R R S, McGregor K F, Brown A R, Amyes S G B, Young H-K. Isolation and characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from hospitalized patients over a 30-month period. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2112–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2112-2116.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palepou M F I, Adebiyi A M A, Tremlett C H, Jensen L B, Woodford N. Molecular analysis of diverse elements mediating VanA glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:605–612. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel R, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Steckelberg J M, Kline B, Cockerill F R. DNA sequence variation within vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2/3 genes of clinical enterococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:202–205. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlada D E, Smulian A G, Cushion M T. Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic susceptibility of enterococci in Cincinnati, Ohio: a prospective citywide survey. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2342–2347. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2342-2347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintiliani R, Courvalin P. Conjugal transfer of the vancomycin resistance determinant vanB between enterococci involves the movement of large genetic elements from chromosome to chromosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintiliani R, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1547, a composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene. 1996;172:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suppola J P, Kolho E, Salmenlinna S, Tarkka E, Varkila V. vanA and vanB incorporate into an endemic ampicillin-resistant vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus faecium strain: effect on interpretation of clonality. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3934–3939. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3934-3939.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swenson J M, Clark N C, Sahm D F, Ferraro M L, Doern G, Hindler J, Jorgensen J H, Pfaller M A, Reller L B, Weinstein M P, Zabransky R J, Tenover F C. Molecular characterization and multilaboratory evaluation of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51299 for quality-control of screening tests for vancomycin and high-level aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3019–3021. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3019-3021.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tremlett C H, Brown D F J, Woodford N. Variation in structure and location of VanA glycopeptide resistance elements among enterococci from a single patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:818–820. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.818-820.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willems R J L, Top J, vandenBraak N, vanBelkum A, Mevius D J, Hendriks G, vanSanten Verheuvel M, vanEmbden J D A. Molecular diversity and evolutionary relationships of Tn1546-like elements in enterococci from humans and animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:483–491. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, editor. Current protocols in molecular biology. Brooklyn, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates; 1994. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodford N, Jones B L, Baccus Z, Ludlam H A, Brown D F J. Linkage of vancomycin and high-level gentamicin resistance genes on the same plasmid in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:179–184. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodford N, Chadwick P R, Morrison D, Cookson B D. Strains of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium can alter their van genotypes during an outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2966–2968. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2966-2968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]