Abstract

Introduction:

End-of-life (EOL) conditions are commonly encountered by emergency physicians (EP). We aim to explore EPs’ experience and perspectives toward EOL discussions in acute settings.

Methods:

A qualitative survey was conducted among EPs in three tertiary institutions. Data on demographics, EOL knowledge, conflict management strategies, comfort level, and perceived barriers to EOL discussions were collected. Data analysis was performed using SPSS and SAS.

Results:

Of 63 respondents, 40 (63.5%) were male. Respondents comprised 22 senior residents/registrars, 9 associate consultants, 22 consultants, and 10 senior consultants. The median duration of emergency department practice was 8 (interquartile range: 6–10) years. A majority (79.3%) reported conducting EOL discussions daily to weekly, with most (90.5%) able to obtain general agreement with families and patients regarding goals of care. Top barriers were communications with family/clinicians, lack of understanding of palliative care, and lack of rapport with patients. 38 (60.3%) deferred discussions to other colleagues (e.g., intensivists), 10 (15.9%) involved more family members, and 13 (20.6%) employed a combination of approaches. Physician's comfort level in discussing EOL issues also differed with physician seniority and patient type. There was a positive correlation between the mean general comfort level when discussing EOL and the seniority of the EPs up till consultancy. However, the comfort level dropped among senior consultants as compared to consultants. EPs were most comfortable discussing EOL of patients with a known terminal illness and least comfortable in cases of sudden death.

Conclusions:

Formal training and standardized framework would be useful to enhance the competency of EPs in conducting EOL discussions.

Keywords: Barriers, communication, emergency department, emergency physicians, end-of-life discussion

INTRODUCTION

The emergency department (ED) is where people attend to resolve all their acute medical and surgical problems. The plethora and spectrum of these acute presentations are so varied, and the emergency physicians (EPs) are required to be extremely versatile in handling them. They may need to look into medical, social, and psychological issues and any other possible permutations: one issue that has increasingly surfaced in their armamentarium of skills and capabilities is end-of-life (EOL) communications.

The initial diagnosis of an EOL condition or a terminal progression of preexisting diseases is frequently encountered by EPs. From family members who are at a loss when confronted with the reality of active death in critically ill individuals without advanced directives to terminally ill patients requesting assistance with symptom control, these situations are particularly challenging in the ED because EPs may not have a well-established rapport with the patients. In addition, the hectic, time-restricted environment does not provide the optimal climate to discuss EOL care. However, EPs being the initial point of contact will need to acquire the capabilities, training, experience, and necessary communications skills to execute them efficiently, adequately, and in a dignified fashion for any patient in crisis.

Proficient communications with patients and their families pose an important challenge to EPs, especially given the brief yet critical interactions and possibly, unrealistic expectation of treatment outcomes.[1] EDs are spaces traditionally designated to look after acutely ill or injured undifferentiated patients across ages and diseases spectra where death is generally considered a failure. This perception leads to disproportionate health-care interventions that can result in a loss of dignity and cause more harm among EOL patients because of the conflicting principles of management. Limited evidence has suggested that patient-provider discussions about EOL preferences are associated with less aggressive treatment near death[2,3] and effective communication respecting physical, emotional, cultural, psychosocial, and spiritual differences among the terminally ill patients and their relatives can contribute to the preservation of the dying patient's dignity in EDs.[3,4] The EPs must be committed to both honoring initial resuscitation orders and having conversations that are paramount to narrow the gap between ED care and patient wishes so that people receive care that best aligns with their wishes.[1,3]

Psychological and physical barriers to proactive EOL discussions prevail, and very few studies focus on EPs’ EOL communication-specific care, especially in the Asian context.[5,6,7,8] This study aims to describe the attitudes and approaches of senior EPs toward EOL discussions in acute settings, assessing their comfort levels and ranking the importance of various barriers commonly encountered and/or cited.

METHODS

An anonymous 20-item questionnaire consisting of 16 multiple choices and four open-ended questions was developed by the authors using an electronic survey tool FORMSG™ based on the authors’ literature review.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15] It was distributed to all senior EPs (senior resident, staff registrar, associate consultant, consultant, and senior consultant) of three tertiary hospitals across Singapore: Singapore General Hospital, Changi General Hospital, and Sengkang General Hospital, with results collated between January 11, 2021, and January 31, 2021. Other than baseline demographic data, EPs were asked questions on three major aspects: physicians’ comfort level, perceived barriers, and conflict management strategies when conducting EOL discussion. Baseline patient characteristics were summarized as count (%) and mean (standard deviation [SD]). Survey ratings for comfort level and perceived importance of specified barriers were summarized as mean (SD). Comparison of means between EP seniority levels was performed using the one-way analysis of variance F-test followed by post hoc t-tests to detect significant pairwise comparisons. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 17.0.

RESULTS

In total, 63 senior EPs responded across the three institutions with 40 (63.5%) males and 23 (36.5%) females in an approximate 2:1 ratio, with the majority of them having >6 years of experience in emergency medicine practice and a median of 8 years. Out of all the respondents, 3 (4.8%) have formal palliative training and 5 (7.9%) subspecialize in palliative emergency medicine. Most 55 (87.2%) of the respondents encounter EOL discussions between daily and fortnightly and a majority 57 (90.5%) reported attaining consensus with regard to goals of care with patients and/or their family members [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demography and baseline characteristics of emergency physicians

| Baseline characteristic | Estimate (n=63), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 23 (36.5) |

| Male | 40 (63.5) |

| Rank | |

| Senior consultant | 10 (15.9) |

| Consultant | 22 (34.9) |

| Associate consultant | 9 (14.3) |

| Staff registrar/senior resident | 22 (34.9) |

| Duration of practice in ED (years) | 8 (6-10) |

| Formal palliative training | 3 (4.8) |

| Subspecialty | |

| Palliative | 5 (7.9) |

| Geriatric | 3 (4.8) |

| Critical care/airway | 11 (17.5) |

| Trauma | 13 (20.6) |

| EMS | 4 (6.3) |

| Emergency cardiology | 3 (4.8) |

| Frequency of EOL discussion | |

| Daily | 14 (22.2) |

| Weekly | 36 (57.1) |

| Fortnightly | 5 (7.9) |

| Monthly | 8 (12.7) |

| Frequency of agreement | |

| Always | 3 (4.8) |

| Generally | 54 (85.7) |

| Sometimes | 6 (9.5) |

Data represented as n (%) or median (IQR) for categorical and continuous data, respectively. EOL: End-of-life, ED: Emergency department, IQR: Interquartile range, EMS: Emergency medical service

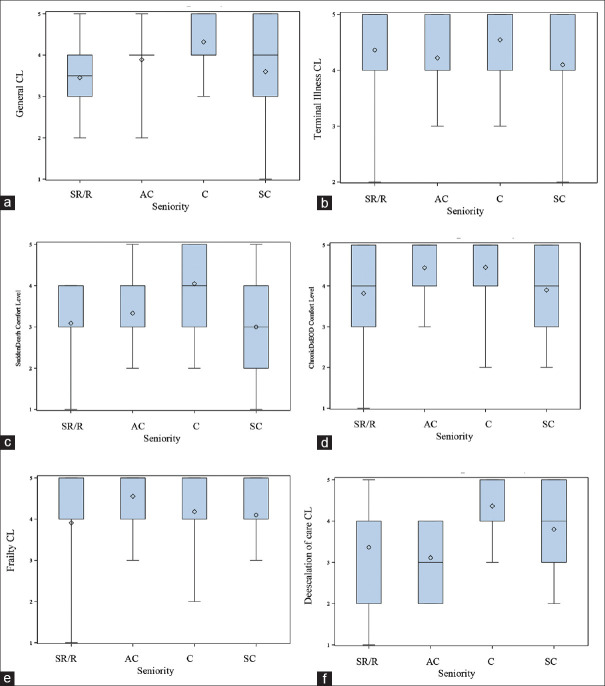

Results of our study showed that EPs are generally comfortable with conducting EOL discussions, reporting a mean comfort level of 3.84 (0.94) on a 5-point scale (5 being most comfortable). Comfort levels vary with patient type as well as EPs seniority. Not surprisingly, EPs reported the highest comfort level rating of 4.37 (0.77) for EOL discussions for patients with known terminal illnesses and the lowest rating of 3.44 (1.16) for cases of sudden death [Table 2]. Increasing seniority showed a trend for an increase in general comfort level for EOL discussions up to consultant level, after which there was a statistically significant dip in rating between consultants to senior consultants [Figure 1a and Table 2]. Similar trends were observed for EOL discussion involving chronic end-organ failure and sudden death cases [Figure 1c, d and Table 2]. Consultants and senior consultants were also much more comfortable with de-escalation of care in the ED compared to their juniors [Figure 1f]. Comfort level in discussing EOL in patients with terminal illness or frailty are similar across seniority [Figure 1b and 1e].

Table 2.

Results of survey about perspectives of and approach to end-of-life discussion among emergency physicians

| Survey components | Survey results (n=63), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Comfort level | 1 - very uncomfortable, 5 - very comfortable |

| General | 3.84 (0.94) |

| Terminal illness | 4.37 (0.77) |

| Sudden death | 3.44 (1.16) |

| Chronic disease with end-organ failure | 4.14 (1.00) |

| Frailty | 4.13 (0.91) |

| De-escalation of care | 3.75 (1.06) |

| Barriers to EOL discussion | 1 - least important; 5 - most important |

| Communication with family/clinicians | 4.38 (0.68) |

| Lack of understanding of palliative care/EOL pathways | 3.90 (0.93) |

| Lack of rapport | 3.84 (1.05) |

| ED design/space/time constraints | 3.71 (1.11) |

| ED support system | 3.54 (1.00) |

| Uncertainty/lack of collaboration | 3.48 (0.98) |

| Uncertain quality of EOL care | 3.40 (1.03) |

| Limited education/training | 3.33 (1.16) |

| Patient age | 3.33 (1.23) |

| Patient background | 3.14 (1.22) |

| Conflict resolution methods | |

| Defer to other colleagues (e.g., ICU) | 38 (60.3) |

| Involve more family members | 10 (15.9) |

| Attempt again | 8 (12.7) |

| Escalate to more senior members | 7 (11.1) |

| Continue ED management without further discussion | 4 (6.3) |

| Concur with patient/family decision | 2 (3.2) |

| Combination of >1 method | 13 (20.6) |

| Deferment of discussion | |

| Yes | 9 (14.3) |

| No | 25 (38.7) |

| Maybe | 29 (46.0) |

| Personally affected by EOL discussion | |

| Yes | 19 (30.2) |

| No | 35 (55.6) |

| Maybe | 9 (14.3) |

| Debriefing | |

| Yes | 7 (11.1) |

| No | 25 (39.7) |

| Sometimes | 31 (49.2) |

| COVID-19 affecting EOL discussions | |

| Yes | 5 (7.9) |

| No | 58 (92.1) |

Data represented as count (%) or mean (SD) for categorical and continuous data, respectively. EOL: End-of-life, ED: Emergency department, ICU: Intensive care unit, SD: Standard deviation

Figure 1.

Comparison of emergency physicians’ comfort level in end-of-life discussions by seniority in various patient encounters. Box-and-Whisker plot (diamond, mean; midline, median). Comfort level rating: 1 – very uncomfortable; 5 – very comfortable. AC – Associate consultant, C – Consultant, CL – Comfort level, R – Staff registrar, SC – Senior consultant, SR – Senior resident, a – General Comfort Level, b – Terminal Illness Comfort Level, c – Sudden Death Comfort Level, d – Chronic disease with End-organ Failure Comfort Level, e – Frailty Comfort Level, f – De-escalation of Care Comfort Level

Out of the 10 commonly cited barriers to EP-initiated EOL discussions, (i) communication with family/clinicians, (ii) lack of understanding of palliative care and evidence-based EOL pathways, and (iii) lack of rapport were ranked top 3 with ratings of 4.38 (0.63), 3.90 (0.93), and 3.84 (1.05), respectively, on a 5-point scale (5 being most important). Patients’ age, background, and limited education/training among EPs were ranked the least important barriers [Table 2]. Subgroup analysis revealed similarities in perceptions despite seniority level [Table 4]. All groups rated communication with family and patient as the most important barrier to EOL discussions and deemed patient factors (either age or background) to be of lowest importance [Table 3].

Table 4.

Emergency physicians’ perceived barriers to end-of-life discussions (by seniority)

| Perceived barriers | Seniority group | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1: Senior resident/staff registrar (n=22) | 2: Associate consultant (n=9) | 3: Consultant (n=22) | 4: Senior consultant (n=10) | ||

| Patient’s age | 4.09 (0.92) | 3.22 (1.30) | 2.68 (1.17) | 3.2 (1.14) | 0.001** |

| Patient’s background | 3.23 (1.19) | 3.78 (1.09) | 2.95 (1.17) | 2.8 (1.40) | 0.279 |

| Lack of rapport | 3.95 (1.00) | 4.00 (0.87) | 3.59 (1.22) | 4.00 (0.94) | 0.595 |

| Communication | 4.55 (0.51) | 4.44 (0.73) | 4.05 (0.79) | 4.70 (0.48) | 0.027* |

| Lack of understanding of PC/EOL pathways | 4.09 (0.81) | 3.89 (1.36) | 3.55 (0.86) | 4.30 (0.68) | 0.109 |

| Uncertainty/lack of collaborative support | 3.45 (1.14) | 3.33 (1.00) | 3.55 (0.74) | 3.50 (1.18) | 0.959 |

| Lack of ED support system | 3.64 (1.05) | 3.78 (0.83) | 3.41 (0.91) | 3.40 (1.27) | 0.740 |

| ED design/space/time | 3.41 (1.18) | 4.11 (0.78) | 3.82 (1.18) | 3.80 (1.03) | 0.392 |

| Limited training/education | 3.59 (0.96) | 3.44 (1.13) | 2.91 (1.23) | 3.60 (1.35) | 0.204 |

| Uncertain of quality of EOL care | 3.59 (1.01) | 3.22 (0.83) | 3.14 (1.04) | 3.70 (1.16) | 0.347 |

ANOVA F-test comparing means. Estimates are presented as mean (SD). As determined by post hoc t-tests, significant pairwise differences (*P<0.05, **P<0.01) in comfort level exist between groups indicated below: patient’s age: 1 versus 3**. Communication: 3 versus 4*. Non parametric analyses were also done but not presented as the results were congruent with the parametric analyses. The Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test was performed for comparison of medians and post-hoc Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner Wilcoxon z-tests for significant pairwise differences. SD: Standard deviation, EOL: End-of-life, ED: Emergency department, PC: Palliative Care

Table 3.

Emergency physicians’ comfort level in end-of-life discussions (by seniority)

| Comfort level category | Seniority group | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1: Senior resident/staff registrar (n=22) | 2: Associate consultant (n=9) | 3: Consultant (n=22) | 4: Senior consultant (n=10) | ||

| General | 3.45 (0.86) | 3.89 (0.78) | 4.32 (0.65) | 3.60 (1.35) | 0.0140 |

| Terminal illness | 4.36 (0.85) | 4.22 (0.67) | 4.55 (0.6) | 4.10 (0.88) | 0.4466 |

| Sudden death | 3.09 (1.06) | 3.33 (0.87) | 4.05 (1.00) | 3.00 (1.49) | 0.0196 |

| Chronic disease with end-organ failure | 3.82 (1.18) | 4.44 (0.73) | 4.45 (0.80) | 3.90 (0.99) | 0.1145 |

| Frailty | 3.91 (1.02) | 4.56 (0.73) | 4.18 (0.91) | 4.10 (0.74) | 0.3442 |

| De-escalation of care | 3.36 (1.22) | 3.11 (0.93) | 4.36 (0.58) | 3.8 (1.03) | 0.0021 |

ANOVA F-test comparing means. Estimates are presented as mean (SD). As determined by post hoc t-tests, significant pairwise differences (*P<0.05, **P<0.01) in comfort level exist between groups indicated below: general: 1 versus 3**, 3 versus 4*. Sudden death: 1 versus 3**, 3 versus 4*. De-escalation of care: 1 versus 3**, 2 versus 3**. Non parametric analyses were also performed but not presented as the results were congruent with the parametric analyses. The Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test was performed for comparison of medians and post-hoc Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner Wilcoxon z-tests for significant pairwise differences. SD: Standard deviation

In response to any conflicts or resistance encountered during EOL discussions, the majority 38 (60.3%) of respondents will involve other colleagues such as intensivists and/or other respective physicians for collaborative practices which could involve the execution of common clinical care pathways. Others would try to involve more family members, make another attempt at discussion, or escalate to more senior EPs. Approximately one-fifth of the respondents would adopt a multifaceted approach by employing a combination of strategies. A minority of 4 (6.3%) senior EPs would choose to continue their ED management and 2 (3.2%) would decide to concur with the patient's and/or family's wishes.

Interestingly, 9 (14.3%) senior EPs reported that they may not engage in EOL discussion with patients in the ED and would defer it [Table 2]. The majority of the senior EPs (35, 55.6%) are not personally affected by EOL discussions, and debriefing of team members is not a routine practice in most cases. Only 7 (11.1%) of EPs report conducting debriefing sessions for their team after EOL discussion. Evidently, the COVID-19 pandemic did not have much impact on the EOL communication.

DISCUSSION

EOL discussion poses an intricate dilemma for emergency care given the inertia from physicians, patients, and systems perspectives. The question of sensitively implementing EOL conversations early remains a pivotal challenge.[12] As medicine advances in our aging population, caring for critically ill patients with complex treatment and care decisions are becoming more common.[9] The emergency team must adopt a patient- and family-centered approach to EOL care.[16] Despite all these, EPs lack evidence-based, practical methods to guide seriously ill patients to discuss their values and preferences for future care.[8] Such crucial conversations are associated with improved quality of life, lower rates of in-hospital death, less aggressive medical care near death, earlier hospice referrals, increased peacefulness, and a 56% greater likelihood of having wishes known and followed.[8] Critical care literature has also reported that ineffective communication is the most significant barrier to quality EOL care.[17] Specific problems identified include inadequate time spent, lack of private space, inadequate training and education in palliative care communication, more time spent talking than listening, lack of active communication, and insufficient understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment.[18,19,20] They often rank communication skills as having equal or greater importance compared to clinical skills.[21] Mularski et al., 2006, defined four out of seven domains which are the quality indictors in EOL care for intensive care units applicable to ED: patient-/family-centered decision-making, communication between the health-care team and patients/families, emotional/practical support for families, and spiritual/cultural support of patients/families.[22] Our study was aimed at answering some of the questions, since EPs tailor manageable, shared and informed decision-making during time of “serious illness conversion” and “crisis communication,” terms deemed by Ouchi et al.[23]

Based on our survey across three tertiary institutions, EOL discussion is indeed a common encounter for the majority of senior EPs and comfort levels do vary across seniority. We have specifically targeted seniors because they are mainly responsible for making critical crisis decisions and carrying out EOL conversations. However, EP seniority does not consistently reflect proficiency in approaching difficult conversions. These could be due to experiences, area of interests, existing administrative or supervisory roles, personalities, and/or communication strategies that support shared decision-making and familiarities with EOL patients, particularly from a multiprofessional or collaborative approach. EOL discussions are complex because it is dependent on multicultural context, policies, and human and resource factors. No matter how dedicated and interpersonally skilled physicians are, the family, spiritual, ethical, cross-cultural, practical, and existential issues that rapidly rise in importance in EOL care will present formidable challenges.[12] A review of best practices has suggested that other professionals (nurses, social workers, clerks, and psychologists) can, and perhaps must, play key roles in facilitating, orchestrating, and documenting these diverse conversations, which has yet to be determined on plausibility in our EDs.[15,24]

Overall, EOL discussions revolving around patients of terminal illnesses, chronic diseases with end-organ failures, and frailty are more comfortable as opposed to those involving sudden death in ED. It could perhaps be explained partially by prior series of EOL conversations, uncomplicated diagnostic and prognostic continuance, adequate advanced care planning or preparation, etc. As more frequently such encounters are experienced, it will certainly add fine-tuning and refinement to the way such conversations are conducted; value-adding to subsequent conversations. Thus, training and experiential practices will certainly help build up capabilities, familiarity and comfort levels. Thus, training and experiential practices will certainly help build up capabilities, familiarity, and comfort levels.

There are many unanswered questions about the EPs role in the chain of communication through the complex trajectory of decision-making with critically ill patients and their family members. There is, however, ample evidence of improvement in patient-centered outcomes after serious illness communication intervention(s) across multiple disciplines and practice environments as part of an interprofessional collaborative effort.[8] Therefore, facilitating early discussion in the course of a patient's hospital journey makes a significant difference. It is surprising to find that senior EPs are occasionally not comfortable starting EOL conversations in acute scenarios, which will need to be addressed: continued medical education on issues revolving around EOL such as communications, best practices, and clinical guidelines at every level of seniority is recommended to keep everyone up to date. The availability of allied professionals such as social workers or bereavement psychologists may also greatly improve patient's experience during EOL encounters.

From our results, communication with patients/family/clinicians stood out as the most important barrier across all seniority level, suggesting that experience alone may not develop expertise in communication skills. This calls for a more structured approach to be undertaken to impart these soft skills. Having a framework, for instance, the “SPECIAL”, “ABCDE,” and “SPIKES” models can act as a memory “jolt” for recalling all the necessary pointers to be included in the conversation.[11]

Finally, comprehending evidence-based EOL and/or palliative care may be necessary, yet not sufficient, conditions for the enhancement of EOL conversations. Models of clinical practices that support such discussions may also be required through the expertise of various disciplines. From our results, the majority of senior EPs prefer collaborative communication and/or combination of techniques such as involving other physicians and more family members while confronted with conflicts. This is in agreement with current literature of framing EOL decisions as a medical consensus among health-care professionals with or without the family and the patient's wishes, gives patients/families time to decide but imposing time limit while putting forward continued treatment despite the suggestion that treatment is futile, eliciting the surrogate's views of patient preferences as the basis for shared decision-making, bringing other health-care professionals into help resolve conflict, and utilizing nurses to act as a go-between for the physicians and families.[14]

CONCLUSION

We conclude that EOL conversations must become a routine, structured intervention of ED care delivery and EPs core skills because it affects patients, families, health-care staffs, organizations, the types of care and support provided, and finally, financial implications. Further education on communication skills and evidenced-based collaborative best practices with respective disciplines will promote more holistic care of acute EOL patients. We propose two things in light of the results of the survey: (I) mandatory training and/or continued medical education in EOL communication/care be introduced or reinforced to equip all EPs and residents with the necessary skillset and (II) streamlining of a standardized framework including clinical practice guidelines or prediction tools to facilitate the integration of even the less experienced in conducting EOL discussions effectively.

There are several limitations in our analysis in addition to the usual limitations associated with survey studies (e.g., sampling bias, demand characteristic bias, desirability bias, and nonresponse bias). The first is including only EDs from one health-care cluster, which may result in sampling bias. Second, the questionnaire has not been tested on validity and reliability. Finally, we do not have an objective measurement of actual knowledge of the senior EPs and only rely on self-reported knowledge. Nevertheless, the survey provides valuable insight into the current practices, knowledge, and perception of EOL communications among senior EPs.

Research quality and ethics statement

Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee waiver was obtained through Singapore Health Services (CIRB Ref. No 2020/3123). The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Table S1.

Survey questions

| 1) Gender |

| A) Female |

| B) Male |

| 2) Job title/rank |

| A) Staff registrar |

| B) Senior resident |

| C) Associate consultant |

| D) Consultant |

| E) Senior consultant |

| 3) Years of practice in emergency department |

| 4) Area of interest/subspecialties |

| 5) Any formal palliative training |

| A) Yes |

| B) No |

| 6) How often do you need to discuss EOL during your daily work? |

| A) Daily |

| B) Weekly |

| C) Every 2 weeks |

| D) Every 3 weeks |

| E) Every monthly |

| 7) How often does patient and/or family agree with your EOL care plans? |

| A) Always |

| B) Generally |

| C) Sometimes |

| D) Seldom |

| E) Rarely |

| 8) How would you resolve any discrepancy or conflicts on EOL discussions? |

| A) Escalate to senior and/or other colleagues |

| B) Defer further discussions to other disciplines |

| C) Try again at a later time |

| D) Involvement of other or more family members |

| E) Proceed with medical management that you deemed most appropriate without further discussions |

| F) Others (please elaborate): _______________________ |

| 9) Please elaborate on above: _____________________________________________ |

| 10) How comfortable are you with EOL discussion with patients and/or NOK in the acute settings (1- very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 11) How comfortable are you with EOL discussions for the following group: Terminally ill or terminally decline in a progressive end-stage disease without any previous documentation of EOL from primary specialists (1-very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 12) How comfortable are you with EOL discussions for the following group: sudden and/or unexpected events such as RTA/sudden cardiopulmonary collapse/pediatric patients (1-very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 13) How comfortable are you with EOL discussions for the following group: Long-term chronic disease with organ failure & dysfunction (1-very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 14) How comfortable are you with EOL discussions for the following group: Elderly/”frailty syndrome” (1-very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 15) Do you prefer to defer the EOL discussion to inpatient team (eg. Palliative team, on-call medical team) |

| Yes |

| No |

| Maybe |

| 16) Does EOL care discussion with patient and/or NOK affect you personally? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Maybe |

| 17) How comfortable are you with de-escalation of care in ED (eg. Weaning down of inotropes, terminal extubations, etcs.) (1-very uncomfortable; 5-very comfortable) |

| 18) Do you routinely debrief your team after EOL discussion? |

| Yes |

| No |

| Sometimes |

| 19) Has COVID-19 pandemic affected your approach to EOL discussion with patients? Please elaborate |

| 20) Please rank the following 10 barriers in order of importance (least to very important): |

| A) Patient’s age |

| B) Access to background information (eg. Spiritual/cultural needs) |

| C) Lack of rapport |

| D) Communication with patient, families and other clinicians |

| E) Understanding of palliative care and evidence-based EOL pathways |

| F) Role uncertainty with lack of collaborative support/partnerships |

| G) Complex and/or lack of support systems and processes in your ED |

| H) Time, space and ED design constrains |

| I) Limited training, experiences and educational resources |

| J) Uncertainty on quality EOL care educational resources |

| Uncertainty on quality EOL care |

EOL: End-of-life

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott J. The POLST paradox: Opportunities and challenges in honoring patient end-of-life wishes in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández-Sola C, Granero-Molina J, Díaz-Cortés MD, Jiménez-López FR, Roman-López P, Saez-Molina E, et al. Characterization, conservation and loss of dignity at the end-of- life in the emergency department. A qualitative protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1392–401. doi: 10.1111/jan.13536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Corey KL, Meghani SH. Associations among end-of-life discussions, health-care utilization, and costs in persons with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2019;36:913–26. doi: 10.1177/1049909119848148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiménez-Herrera MF, Axelsson C. Some ethical conflicts in emergency care. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22:548–60. doi: 10.1177/0969733014549880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shearer FM, Rogers IR, Monterosso L, Ross-Adjie G, Rogers JR. Understanding emergency department staff needs and perceptions in the provision of palliative care. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:249–55. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russ A, Mountain D, Rogers IR, Shearer F, Monterosso L, Ross-Adjie G, et al. Staff perceptions of palliative care in a public Australian, metropolitan emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27:287–94. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yash Pal R, Kuan WS, Koh Y, Venugopal K, Ibrahim I. Death among elderly patients in the emergency department: A needs assessment for end-of-life care. Singapore Med J. 2017;58:129–33. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang ST, Liu LN, Lin KC, Chung JH, Hsieh CH, Chou WC, et al. Trajectories of the multidimensional dying experience for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:863–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles TM, Hammad K, Breaden K, Drummond C, Bradley SL, Gerace A, et al. Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of caring for patients who die in the emergency department setting. Int Emerg Nurs. 2019;47:100789. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2019.100789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alqahtani AJ, Mitchell G. End-of-life care challenges from staff viewpoints in emergency departments: Systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 2019;7:83. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7030083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lateef F. The Special Model for End of Life Discussions in the Emergency Department: Touching Hearts, Calming Minds. Palliat Med Care Int J. 2020;3:82–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson DG, Tobin DR. End-of-life conversations: Evolving practice and theory. JAMA. 2000;284:1573–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker C, Beck K, Vincent A, Hunziker S. Communication challenges in end-of-life decisions. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20351. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson RJ, Bloch S, Armstrong M, Stone PC, Low JT. Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat Med. 2019;33:926–41. doi: 10.1177/0269216319852007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins GD, Griffiths F, Slowther AM, George R, Frtiz Z, Satherley P, et al. Do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation decisions: an evidence synthesis. Heal Serv Deliv Res. 2016;4:1–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limehouse WE, Ramana Feeser V, Bookman KJ, Derse A. A model for emergency department end-of-life communications after acute devastating events-part I: Decision-making capacity, surrogates, and advance directives. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:E1068–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy MM, McBride DL. End-of-life care in the Intensive Care Unit: State of the art in 2006. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S306–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000246096.18214.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold R, Billings JA, Block SD, et al. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2009. [Last cited on 2021 May 31]. Hospice and Palliative Medicine Core Competencies Version 2.3 [Internet] pp. 1–20. Available from: http://aahpm.org/uploads/education/competencies/Competenciesv. 2.3.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore CD. Communication issues and advance care planning. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2005;21:11–9. doi: 10.1053/j.soncn.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaschenko J, O’Conner-Von S, Peden-McAlpine C. The “big picture”: Communicating with families about end-of-life care in Intensive Care Unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009;28:224–31. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181ac4c95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung. 1990;19:401–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, Burt R, Byock I, Fuhrman C, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: A consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S404–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouchi K, George N, Schuur JD, Aaronson EL, Lindvall C, Bernstein E, et al. Goals-of-care conversations for older adults with serious illness in the emergency department: Challenges and opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen A, Brown R, Archibald N, Aliotta S, Fox PD. Best Practices in Coordinated Care [Internet] 2000. [Last cited on 2021 May 31]. Available from: https://www.mathematica.org/publications/best-practices-in-coordinated-care .