To the Editor: The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant has three major sublineages: BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3.1 BA.1 rapidly became dominant and has shown substantial escape from neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccination.2-4 The number of cases of BA.2 has recently increased in many regions of the world, suggesting that BA.2 has a selective advantage over BA.1. BA.1 and BA.2 share multiple common mutations, but each also has unique mutations1 (Figure 1A). The ability of BA.2 to evade neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccination or infection is unclear.

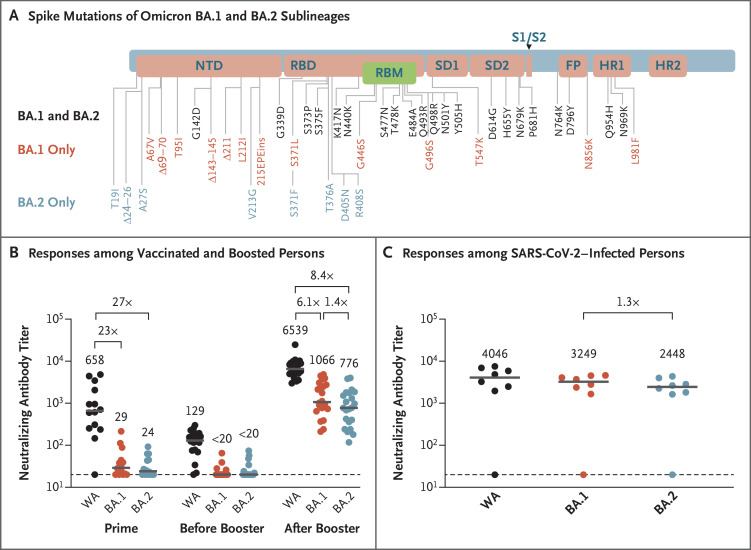

Figure 1. Mutations of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Sublineages and Neutralizing Antibody Responses.

Panel A shows the mutations of the omicron BA.1 and BA.2 sublineages in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein. Panel B shows neutralizing antibody titers that were measured by a luciferase-based pseudovirus neutralization assay in serum samples that were obtained from 24 persons who had been vaccinated and boosted. Titers were measured 2 weeks after the initial BNT162b2 vaccination (prime), before the third dose (booster) of the BNT162b2 vaccine (i.e., 6 months after the initial vaccination), and 2 weeks after the booster. Panel C shows neutralizing antibody titers that were measured in serum samples obtained from 8 persons with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, of whom 7 had been vaccinated. Titers were measured at a median of 14 days after the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, presumably with BA.1. The person with no detectable neutralizing antibody titers was unvaccinated; the serum sample was obtained 4 days after diagnosis, and the person was hospitalized with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pneumonia. In Panels B and C, neutralizing antibody responses against the SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 strain (WA) and the omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants were evaluated. Median titers (horizontal gray lines) are presented, as well as the median titer values. Dots indicate individual samples. The horizontal dashed lines along the x axes indicate the limit of detection. FP denotes fusion peptide, HR1 heptad repeat 1, HR2 heptad repeat 2, NTD N-terminal domain, RBD receptor-binding domain, RBM receptor-binding motif, SD1 subdomain 1, and SD2 subdomain 2.

We evaluated neutralizing antibody responses against the parental WA1/2020 strain of the virus, as well as against the omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants, in 24 persons who had been vaccinated and boosted with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer–BioNTech)5 and had not had infection with SARS-CoV-2 and in 8 persons with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, irrespective of vaccination status. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are provided in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

After the initial two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine, the median pseudovirus neutralizing antibody titers against WA1/2020, BA.1, and BA.2 were 658, 29, and 24, respectively (Figure 1B), indicating that the median neutralizing antibody titer against WA1/2020 was 23 and 27 times those for BA.1 and BA.2, respectively. Six months after the initial vaccination, the median neutralizing antibody titers declined to 129 for WA1/2020 and to less than 20 for both BA.1 and BA.2. Two weeks after the third dose (booster) of the BNT162b2 vaccine, the median neutralizing antibody titers increased substantially to 6539 for WA1/2020, 1066 for BA.1, and 776 for BA.2, indicating that the median neutralizing antibody titer against WA1/2020 was 6.1 and 8.4 times those for BA.1 and BA.2, respectively (Figure 1B). The median BA.2 neutralizing antibody titer was lower than the median BA.1 neutralizing antibody titer by a factor of 1.4.

We next evaluated neutralizing antibody titers in the 8 persons with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (see Tables S1 and S2) at a median of 14 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was diagnosed during a time when the omicron BA.1 sublineage was responsible for more than 99% of new infections. The median neutralizing antibody titers were 4046 for WA1/2020, 3249 for BA.1, and 2448 for BA.2 (Figure 1C). The median BA.1 neutralizing antibody titer was 1.3 times the median BA.2 neutralizing antibody titer. The one person who did not have detectable neutralizing antibody titers was unvaccinated, and the serum sample was obtained 4 days after diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Overall, these data show that neutralizing antibody titers against BA.2 were similar to those against BA.1, with median titers against BA.2 that were lower than those against BA.1 by a factor of 1.3 to 1.4. A third dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine was needed for induction of consistent neutralizing antibody titers against either BA.1 or BA.2.3,4 Moreover, in vaccinated persons who had presumably been infected with BA.1, robust neutralizing antibody titers against BA.2 developed, which suggests a substantial degree of cross-reactive natural immunity. These findings have important public health implications and suggest that the increasing frequency of BA.2 in the context of the BA.1 surge is probably related to increased transmissibility rather than to enhanced immunologic escape.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on March 16, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant CA260476), the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness, the Ragon Institute, and the Musk Foundation (Dr. Barouch). Dr. Collier is supported by the Reproductive Scientist Development Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (grant HD000849).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 2022. January 7 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cele S, Jackson L, Khoury DS, et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature 2022;602:654-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt F, Muecksch F, Weisblum Y, et al. Plasma neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. N Engl J Med 2022;386:599-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Iketani S, Guo Y, et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2022;602:676-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603-2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.