ABSTRACT

While infections by enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) are generally self-limiting, they can occasionally lead to serious neurological complications and death. No licensed therapies against EV-A71 currently exist. Using anti-virus-induced cytopathic effect assays, 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (3,4-DCQA) from Ilex kaushue extracts was found to exert significant anti-EV-A71 activity, with a broad inhibitory spectrum against different EV-A71 genotypes. Time-of-drug-addition assays revealed that 3,4-DCQA affects the initial phase (entry step) of EV-A71 infection by directly targeting viral particles and disrupting viral attachment to host cells. Using resistant virus selection experiments, we found that 3,4-DCQA targets the glutamic acid residue at position 98 (E98) and the proline residue at position 246 (P246) in the 5-fold axis located within the VP1 structural protein. Recombinant viruses harboring the two mutations were resistant to 3,4-DCQA-elicited inhibition of virus attachment and penetration into human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells. Finally, we showed that 3,4-DCQA specifically inhibited the attachment of EV-A71 to the host receptor heparan sulfate (HS), but not to the scavenger receptor class B member 2 (SCARB2) and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL1). Molecular docking analysis confirmed that 3,4-DCQA targets the 5-fold axis to form a stable structure with the E98 and P246 residues through noncovalent and van der Waals interactions. The targeting of E98 and P246 by 3,4-DCQA was found to be specific; accordingly, HS binding of viruses carrying the K242A or K244A mutations in the 5-fold axis was successfully inhibited by 3,4-DCQA.The clinical utility of 3,4-DCQA in the prevention or treatment of EV-A71 infections warrants further scrutiny.

IMPORTANCE The canyon region and the 5-fold axis of the EV-A71 viral particle located within the VP1 protein mediate the interaction of the virus with host surface receptors. The three most extensively investigated cellular receptors for EV-A71 include SCARB2, PSGL1, and cell surface heparan sulfate. In the current study, a RD cell-based anti-cytopathic effect assay was used to investigate the potential broad spectrum inhibitory activity of 3,4-DCQA against different EV-A71 strains. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that 3,4-DCQA disrupts the interaction between the 5-fold axis of EV-A71 and its heparan sulfate receptor; however, no effect was seen on the SCARB2 or PSGL1 receptors. Taken together, our findings show that this natural product may pave the way to novel anti-EV-A71 therapeutic strategies.

KEYWORDS: 3, 4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, enterovirus-A71, 5-fold axis, heparan sulphate

INTRODUCTION

Enterovirus-A71 (EV-A71 or EV71), which belongs to the genus Enterovirus, family Picornaviridae, is a nonenveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus with a genome of approximately 7.5 kb (1). Morphologically, EV-A71 virions have the symmetry of an icosahedron and are composed of structural proteins (2). The viral genome encodes a single polyprotein that is processed to yield four structural proteins (VP1−VP4) and seven nonstructural proteins (2A to 2C and 3A to 3D) (2).

The EV-A71 life cycle starts with a physical interaction between a host surface receptor on target cells and two virus binding sites (termed the canyon and the 5-fold axis) located within the VP1 protein (3, 4). The 5-fold axis symmetry is formed by VP1 and surrounded by a canyon (5). Three well-characterized host receptors, including human scavenger receptor class B, member 2 (SCARB2); P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1); and heparan sulfate (HS); have been implicated in EV-A71 attachment to the cell surface (4). SCARB2 can bind EV-A71 virions through the GH loop of VP1 and the EF loop of VP2 structural proteins (6–8). Conversely, PSGL-1 and HS bind to positively charged amino acids located in proximity to the 5-fold axis (4). SCARB2 is involved in viral attachment, entry, and uncoating; however, no study has reported the occurrence of uncoating following PSGL1 or HS binding (9, 10). SCARB2 triggers viral uncoating by displacing the lipid pocket factor (e.g., sphingosine) through pH-dependent conformational changes (10, 11). We have previously shown that an imidazolidinone derivative, termed PR66, interferes with EV-A71 uncoating by interacting with the VP1 structural protein (12). HS, a linear polysaccharide molecule bearing excess positive charges, is expressed on the cell surface of most tissues (13, 14). Several enteroviruses can utilize HS for initial binding to target cells (15–18). As for EV-A71, the positively charged 5-fold axis has the ability to electrostatically interact with negatively charged HS (5). In this scenario, compounds which contain sulfonated aromatic ring structures (e.g., heparin and suramin) as well as an ester of caffeic acid and 3,4-dihydroxyphenyllactic acid (e.g., rosmarinic acid [RA]) have the potential to prevent the attachment or entry of EV-A71 into host cells (19–21).

While infections by EV-A71 are generally self-limiting, they can occasionally lead to serious neurological complications (e.g., aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis) and death (22). Unfortunately, no proven effective therapies against EV-A71 currently exist. Our laboratory is involved in an ongoing effort to identify compounds with anti-EV-A71 activity from a variety of plants and natural sources (23, 24). Ilex kaushue (also known as Ilex kudingcha C. J. Tseng) is a bitter tea of Chinese origin. In this study, we show that 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (3,4-DCQA; Fig. 1) from I. kaushue exerts a significant anti-EV-A71 activity. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that 3,4-DCQA disrupts the interaction between the 5-fold axis of EV-A71 and the HS receptor, ultimately interfering with virus entry into target cells.

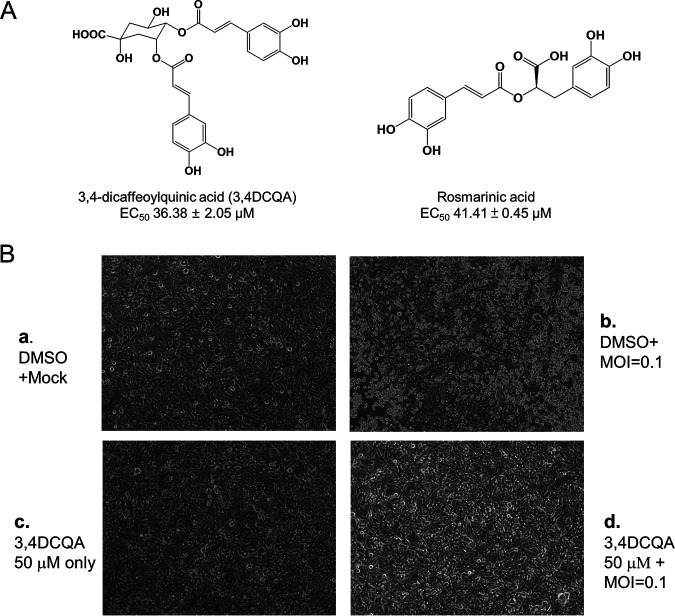

FIG 1.

3,4-DCQA suppresses EV-A71-induced cytopathic effects in RD cells. (A) Chemical structures of 3,4-DCQA and rosmarinic acid. (B) Microscopy findings revealed that 3,4-DCQA prevented EV-A71-induced cytopathic effects in RD cells. (a) Mock: mock infection with DMSO; (b) Virus: infection with EV-A71 (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.1) in DMSO; (c) 3,4-DCQA: mock infection and concomitant exposure to 3,4-DCQA (50 μM); (d) infection with EV-A71 (MOI = 0.1) in DMSO and concomitant exposure to 3,4-DCQA (50 μM).

RESULTS

Anti-EV-A71 activity of 3,4-DCQA.

While screening for medicinal plants with anti-EV-A71 activity in human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells, I. kaushue water extract was identified as having satisfactory antiviral potency (50% effective concentration [EC50]: 44.2 ± 12.7 μg/mL). The active components responsible for antiviral activity were purified with high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC; purity: >96%) (25). Three DCQA isomers (3,4-, 3,5-, and 4,5-DCQA) exhibited similar activity against EV-A71 (Table 1). Inhibition spectrum assays revealed that 3,4-DCQA had an EC50 of 36.38 ± 2.05 μM against EV-A71 TW/2231/1998, with a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of >400 μM in RD cells (Table 2). While the compound was also active against other EV-A71 genotypes, including strain 5865/sin/000009 (<50 μM), no efficacy against the influenza virus was observed (Table 2). The selectivity indices (SI) for the different EV-A71 strains were as high as 139 (Table 2). The antiviral activity of 3,4-DCQA was further investigated with an anti-cytopathic effect (CPE) assay (Fig. 1B). Exposure to 3,4-DCQA protected RD cells against EV-A71 infection (Fig. 1B, subsection b), whereas untreated control cells infected with EV-A71 acquired a rounded morphology as a result of a cytopathic effect (Fig. 1B, subsection d). 3,4-DCQA and DMSO were not cytotoxic (Fig. 1B, subsections a and c). Taken together, these results suggest that 3,4-DCQA protects cells against experimental infections with different EV-A71 strains.

TABLE 1.

Anti-EV-A71 activity of different compounds isolated from I. kaushue water extract

| Compound | EC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|

| 3-CQA | >50 |

| 4-CQA | >50 |

| 5-CQA | >50 |

| 3,4-DCQA | 36.38 ± 1.02 |

| 3,5-DCQA | 39.57 ± 0.73 |

| 4,5-DCQA | 38.75 ± 0.15 |

| Ursolic acid | >50 |

| Kudinoside A | >50 |

| Kudinoside C | >50 |

| Kudinoside D | >50 |

| Kudinoside F | >50 |

| Latifoloside H | >50 |

| Latifoloside G | >50 |

| Menisdaurin D | >50 |

| Menisdaurin | >50 |

| Menisdaurin F | >50 |

EC50: concentration of compound that inhibited EV-A71-induced cytopathic effect by 50%. Data are means ± standard deviations from at least three independent experiments.

TABLE 2.

Inhibition spectrum of 3,4-DCQA against different EV-A71 and influenza virus strains

| Target | 3,4-DCQA (μM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CC50 | EC50a | SIb | |

| Cells | |||

| RD | >400 | ||

| MDCKc | >100 | ||

| Virus strains | |||

| Influenza A/WSN/33 | >100 | ||

| EV71 BrCr (A)d | 20.80 ± 1.83 | >19 | |

| EV71 TW/2557/2012 (B) | 8.65 ± 0.24 | >50 | |

| EV71 TW/51045/2012 (B) | 2.87 ± 0.21 | >139 | |

| EV71 5865/sin/000009 (B) | 4.07 ± 0.15 | >98 | |

| EV71 TW/2231/1998 (C) | 36.38 ± 2.05 | >11 | |

| EV71 TW/184/2012 (C) | 49.92 ± 6.71 | >8 | |

| EV71 TW/73/2012 (C) | 7.41 ± 3.04 | >47 | |

Data are means ± standard deviations from two or three independent experiments.

Ratio of CC50 to EC50.

MDCK cells were used for influenza virus experiments.

Genotype.

3,4-DCQA prevents EV-A71 entry.

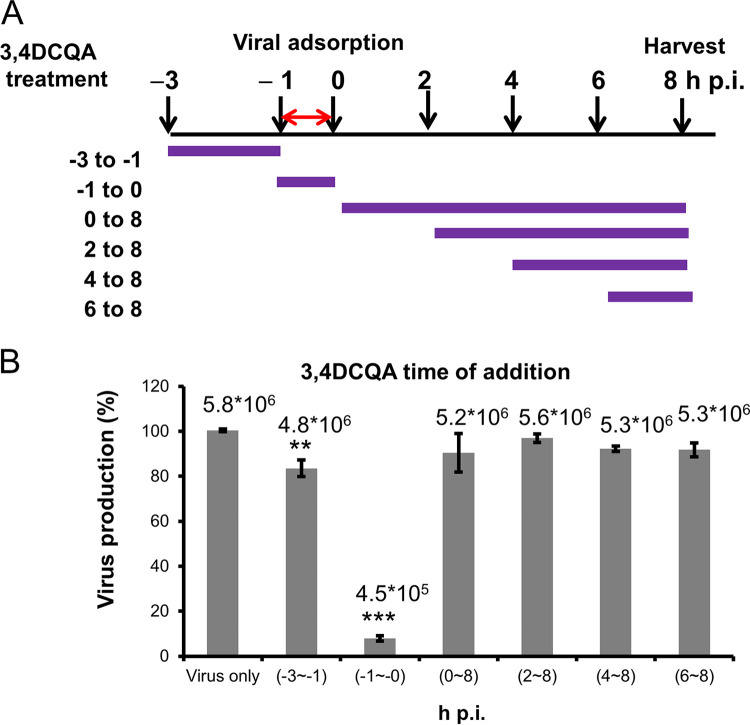

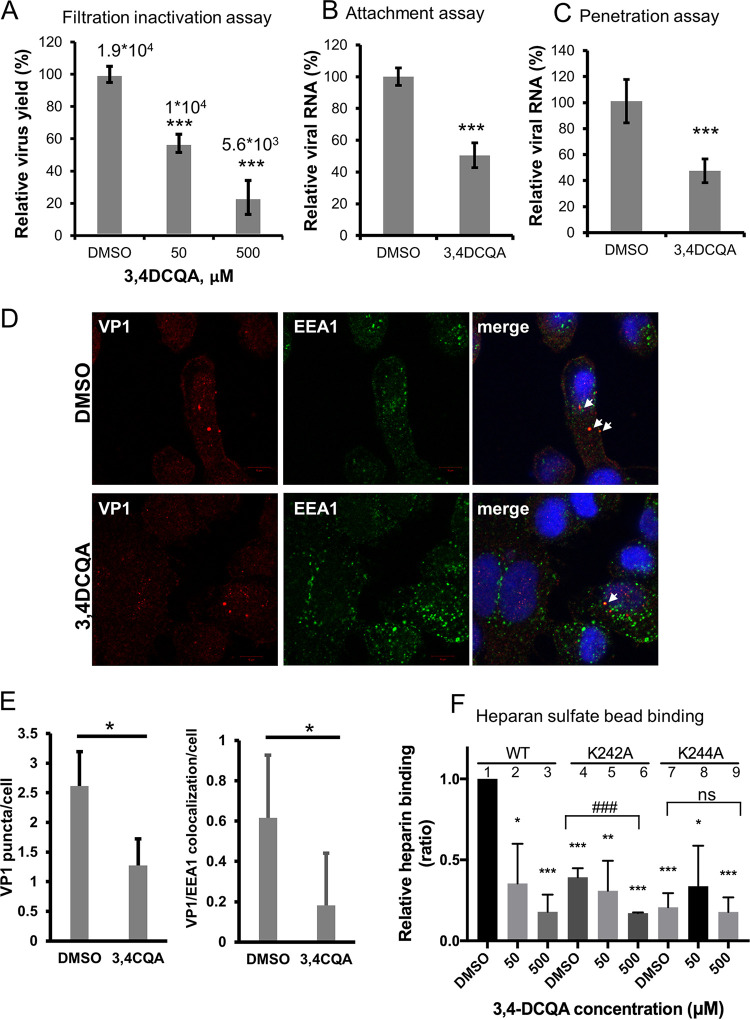

Time-of-addition assays were used to investigate the mechanisms by which 3,4-DCQA exerts its anti-EV-A71 activity (Fig. 2). Exposure to 3,4-DCQA during the pre-adsorption phase (between −3 and −1 h postinfection [hpi]) resulted in a moderate inhibition compared with unexposed control cells infected with EV-A71 (Fig. 2B). While exposure to 3,4-DCQA at different time points during the post-adsorption phases (between 0 and 8 hpi; 2 and 8 hpi; 4 and 8 hpi; and 6 and 8 hpi) did not produce significant anti-EV-A71 effects (Fig. 2B), a marked inhibitory effect was observed when 3,4-DCQA was applied during the adsorption phase (between −1 and 0 hpi.; Fig. 2B). These results suggest that 3,4-DCQA may inhibit EV-A71 entry by targeting either viral particles or host cells. To gain further mechanistic insights, a centrifugal filtration inactivation assay was performed. To this aim, the virus was preincubated with the compound. After removal of the compound by filtration, virus titers were quantified (Fig. 3A). We found that virus titers, determined with plaque assays, were significantly reduced in a dose-dependent fashion when cells were exposed to 3,4-DCQA; thus, 3,4-DCQA directly targeted EV-A71 particles (Fig. 3A). An attachment inhibition assay carried out for confirmation revealed a >50% inhibition following 3,4-DCQA exposure (50 μM; Fig. 3B). A penetration inhibition assay was performed to assess whether 3,4-DCQA was capable of inhibiting viral endocytosis. The results of reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) revealed that exposure to 3,4-DCQA (50 μM) reduced viral penetration into host cells by more than 50% (Fig. 3C). Additional confocal immunofluorescence microscopy experiments were performed to confirm endocytic uptake of the virus. Viral penetration into the cells, as reflected by endocytic VP1 puncta, was significantly inhibited by 3,4-DCQA (Fig. 3D; quantitative analysis provided in the left panel of Fig. 3E). Moreover, the colocalization of VP1 and the early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1; see arrows in figure) and their relative proportions were significantly inhibited by 3,4-DCQA (Fig. 3D; quantitative analysis provided in the right panel of Fig. 3E). These results indicate that the virus did not simply bind to the surface of RD cells; rather, it was internalized and delivered to early endosomes. This process was effectively inhibited by 3,4-DCQA. Taken together, these results indicate that 3,4-DCQA was able to directly inhibit the attachment of viral particles to host cells and block their subsequent entry. Therefore, we further examined the potential occurrence of electrostatic interactions between 3,4-DCQA and the 5-fold axis of EV-A71 at crucial HS binding sites (i.e., the elysine residues at positions 242 and 244 of VP1: VP1-K242 and VP1-K244). Mutant viruses carrying the VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A variants were previously reported to have a reduced capacity to bind HS compared with the wild-type virus 5865/sin/000009, from which these variants were derived (26, 27). We validated this finding by showing that the HS binding capacity of VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A variants was lower than that of the wild-type virus (experiments 1, 4 and 7; Fig. 3F). Binding of the wild-type virus to HS beads was more prone to be inhibited by 3,4-DCQA at low concentrations (50 μM) compared with that of the 2231/1998 strain (experiments 1 to 3; Fig. 3F; Table 2). While the K242A variant was significantly inhibited by 3,4-DCQA (500 μM) (experiments 4 to 6; Fig. 3F), no inhibition was observed for the K244A mutant (experiments 7 to 9; Fig. 3F) because the VP1-K244A mutant virus was unable to bind to HS beads (no. 1 versus no. 7, Fig. 3F).

FIG 2.

Anti-EV-A71 activity of 3,4-DCQA assessed by time-of-addition assays in RD cells. (A) Schematic representation of 3,4-DCQA exposure at different time points during the viral life cycle. Purple lines denote the duration of incubation with 3,4-DCQA, whereas the red double arrow indicates the duration of viral infection (between −1 and 0 hours postinfection [hpi]). (B) Bar chart showing the extent of reduction in EV-A71 titers related to different time points of 3,4-DCQA exposure. All data were normalized to control conditions (virus-only group arbitrarily set to 100%). Data are presented as means ± standard deviations of four replicates from two independent experiments; comparisons were carried out using the Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001). We also showed the results in mean log viral titer (PFU/mL) to ensure a significant viral titer load reduction.

FIG 3.

(A) Centrifugal filtration inactivation assay. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments, and two replicates for each assay were used. Viral titers were also expressed as PFU/mL. (B) Attachment inhibition assay and (C to E) penetration inhibition assay. (B to C) RNA was extracted and analyzed with RT-qPCR to detect viral attachment and viral penetration into cells. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. (D to E) Inhibition of penetration by 3,4-DCQA by confocal immunofluorescence microscopic analysis. Bar: 10 μm. Images of endocytosed VP1 inhibited by 3,4-DCQA were analyzed with IN Cell Investigator high-content analysis software. Viral penetration into the cells was reflected by cell-associated VP1 puncta (panel D and left part of panel E). Additionally, colocalization of VP1 and EEA1 (arrows) and their relative proportions were quantified (panel D and right part of panel E). (F) Heparan sulfate pulldown assay. The wild-type 5865/sin/000009 strain as well as mutants carrying the VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A variants were pretreated with DMSO or 3,4-DCQA before binding to heparan sulfate beads. Virus attachment was assessed with RT-qPCR. RNA copy numbers for each experiment were normalized to the wild-type dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control (arbitrarily set to 1). Results are from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, and ***, P < 0.001. ***, P < 0.001 ns for comparisons between DMSO and 3,4-DCQA (500 μM) treatment.

EV-A71 viruses with mutations affecting residues around the 5-fold axis are resistant to 3,4-DCQA inhibition.

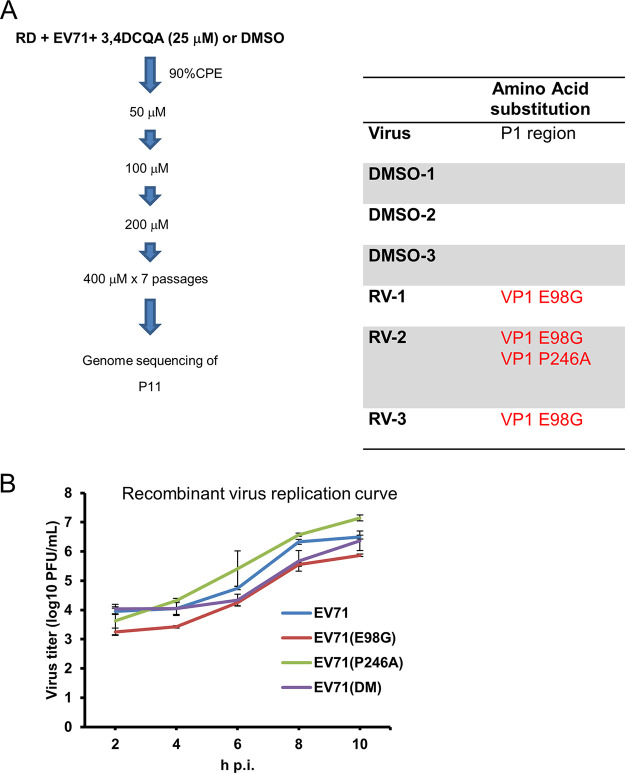

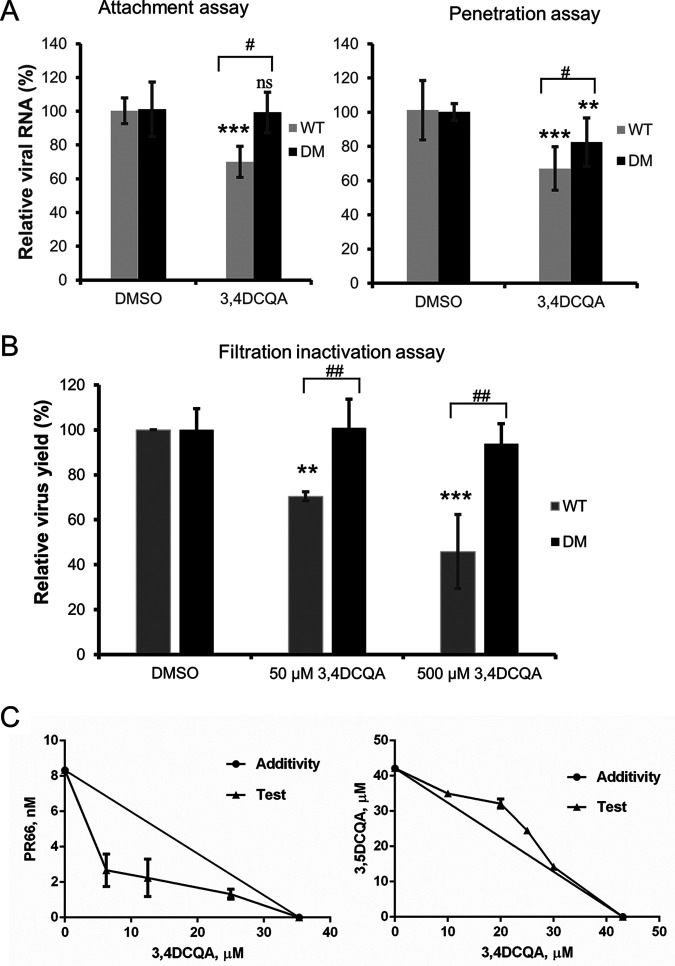

Because the VP1-K242 and VP1-K244 residues, which are responsible for HS binding, did not bind to 3,4-DCQA (Fig. 3F), selection of resistant viruses was performed to further clarify its mechanisms of action. Whole ORF genome sequencing revealed that resistant, but not wild-type, viruses carried two mutations (VP1-E98G and VP1-P246A) affecting the capsid protein VP1 (Fig. 4A). Resistance was confirmed by producing recombinant viruses from the EV-A71 TW/2231/1998 infectious clone through reverse genetics (Table 3). The results of EV-A71-induced cytopathic effect inhibition assays revealed that the plasmid-derived wild-type virus, as well as the VP1-E98G and VP1-P246A mutants, were sensitive to 3,4-DCQA and showed similar EC50 values. However, the VP1-E98G/P246A double mutant (DM) was found to be resistant (EC50 values of >400 μM); thus, the concomitant presence of the two mutations conferred resistance to 3,4-DCQA inhibition (Table 3). While viruses carrying the P246A mutation showed slightly faster growth, no significant differences were observed between wild-type and mutant viruses (Fig. 4B). Thus, the E98G and P246A mutations did not have a major impact on replication kinetics. However, 3,4-DCQA was unable to inhibit the attachment and penetration of the VP1-E98G/P246A DM variant (Fig. 5A). Similar results were observed using a filtration inactivation assay (Fig. 5B), ultimately suggesting that the DM affected attachment to receptors during EV-A71 entry. Thus, we used PR66, a compound which mimics the hydrophobic pocket of the capsid protein VP1, to stabilize virus structure and block the uncoating process (12). Isobolographic analysis revealed that the combination of PR66 and 3,4-DCQA had a synergistic effect (combination index [CI] = 0.662; Fig. 5C, left panel). Another active compound from I. kudingcha (3,5-DCQA) was structurally similar to 3,4-DCQA and showed a comparable EC50 value (Table 1). The CI value for the combination of 3,5-DCQA and 3,4-DCQA was ∼1.12, suggesting an antagonistic activity of the two compounds which may interact with similar VP1-binding sites (Fig. 5C; right panel). Taken together, these data indicate that the mechanisms of action of 3,4-DCQA and PR66 are distinct.

FIG 4.

Selection and identification of 3,4-DCQA-resistant viruses. (A) Experimental flow chart for the selection and identification of 3,4-DCQA-resistant viruses. 3,4-DCQA- or DMSO-treated viruses were plaque-purified and Sanger-sequenced (three independent clones each). (B) Growth kinetics of wild-type and mutant EV-A71 TW/2231/1998 recombinant viruses. RD cells were infected (MOI = 1) with different recombinant viruses (wild-type, E98G mutant, P246A mutant, and double-mutant) for 1 h. Samples were harvested at the reported time points and virus titers were determined using plaque assays. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from two independent experiments; duplicates were included in each experiment.

TABLE 3.

EC50 of 3,4-DCQA against wild-type and mutant EV-A71 viruses derived from cDNA clonesa

| EV-A71 virus | EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| TW/2231/1998 (WT) | 10.64 ± 0.16 |

| TW/2231/1998 (E98G) | 10.20 ± 0.49 |

| TW/2231/1998 (P246A) | 9.23 ± 0.15 |

| TW/2231/1998 (E98G/P246A) | >400 |

WT, wild type. EC50 values are means ± standard deviations from two or three independent experiments.

FIG 5.

Attachment, penetration, and filtration inactivation assays of wild-type and E98G/P246A mutant viruses. (A) Attachment (left graph) and penetration (right graph) assays. Subsequently, RNA was extracted and analyzed with RT-qPCR. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001 compared with control (DMSO). ##, P < 0.01 compared with the DM group. (B) Filtration inactivation assays. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. (C) 3,4-DCQA was used in combination with either PR66 (left) or 3,5-DCQA (right).

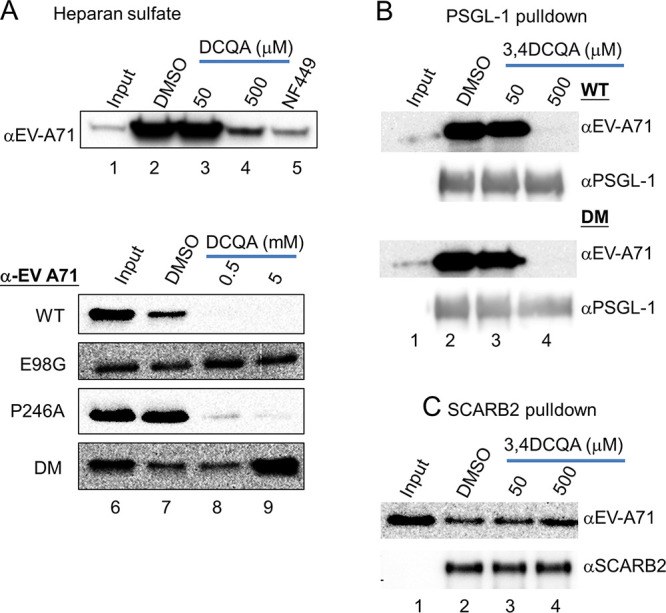

The E98/P246 VP1 residues in the 5-fold axis specifically bind to heparan sulfate.

Structural analysis revealed that the E98/P246 VP1 residues were located in the vertex of the 5-fold axis (3). We therefore used pulldown assays to investigate further the interactions between EV-A71 and the two cell receptors (HS and PSGL-1) known to interact with the 5-fold axis (26, 27). To this aim, EV-A71 was pre-incubated with 3,4-DCQA or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) before being precipitated with HS-Sepharose (Fig. 6A). High concentrations of 3,4-DCQA (500 μM) abrogated binding between wild-type virus and HS beads (Fig. 6A, lane 2 versus lane 4). A known inhibitor (NF449) of the virus-HS interaction was used as positive control (Fig. 6A, lane 5) (26). The VP1-E98G/P246A DM variant retained its ability to bind HS, thus being insensitive to 3,4-DCQA inhibition; however, this was not the case for both the wild-type virus and the viruses harboring the VP1-P246A mutation (Fig. 6A, lane 7 versus lane 8). PSGL-1 also binds to the 5-fold axis, with residue 145 in VP1 playing a crucial role in the PSGL1-virus interaction (28). Thus, we investigated whether 3,4-DCQA can inhibit PSGL-1 binding to wild-type and double-mutant EV-A71 variants. The results revealed that 3,4-DCQA effectively inhibited binding of all viruses through the PSGL-1 receptor (Fig. 6B). Thus, the E98G/P246A mutations may be responsible for resistance to the virus-HS interaction but not for the virus-PSGL1 interaction. SCARB2 pulldown assays were performed to confirm that 3,4-DCQA affects EV-A71 binding through HS recognition sites and not via the canyon region. 3,4-DCQA at high concentrations (500 μM) did not affect binding through the SCARB2 receptor (i.e., a canyon binder; Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that 3,4-DCQA inhibits EV-A71 attachment to host cells by interfering with HS, but not SCARB2, binding.

FIG 6.

Receptor pulldown assays. Heparan sulfate receptor pulldown of double- or single-mutant viruses (A). 3,4-DCQA, NF449 (50 μM), or DMSO were initially mixed on ice for 1 h with either the wild-type EV-A71 recombinant virus or viruses carrying E98G and/or P246A mutations; subsequently, heparan sulfate bead pulldown was performed. 3,4-DCQA-induced inhibition was monitored with Western blotting using anti-EV71 antibodies. (B to C) PSGL-1 and SCARB2 receptor pulldown assays. Results are from three independent and reproducible experiments (control: 10% of input).

DISCUSSION

The results of our study demonstrate that 3,4-DCQA from I. kaushue effectively inhibits EV-A71 attachment to host cells by interfering with HS binding. The chemical structure of DCQA contains one quinic acid group and two caffeic acid residues (29). Three structurally related dicaffeoylquinic acids (3,4-DCQA, 3,5-DCQAk, and 4,5-DCQA) are biologically active against EV-A71 (Table 1). A previous study also demonstrated that 3,4-DCQA can inhibit EV-A71 replication by modulation of glutathione redox homeostasis.(30) Here, we found that 3,4-DCQA exerts its anti-EV-A71 activity by targeting some crucial steps that lead to HS-mediated virus entry. Specifically, our findings indicated that 3,4-DCQA applied during the adsorption phase (between −1 and 0 hpi.) significantly reduced virus titers (Fig. 2). Additionally, 3,4-DCQA effectively inhibited virus attachment and penetration into host cells (Fig. 3B–E and Fig. 5A). Notably, inactivation of virions by 3,4-DCQA was found to prevent cell invasion (Fig. 3A and 5B). Mechanistically, selection of resistant viruses revealed that 3,4-DCQA targets the 5-fold axis located within the VP1 protein (Fig. 4), ultimately inhibiting the attachment of EV-A71 to host cells through HS (Fig. 6).

The binding of negatively charged HS on the cell surface with the 5-fold axis of EV-A71, which is rich in positively charged amino acid residues, is mediated by electrostatic interactions (27, 31, 32). As expected, EV-A71 infection rates can markedly be reduced by pretreating virions with negatively charged compounds, including heparin, suramin, and NF449 (20, 26, 33). These molecules are thought to provide their antiviral effects via partial inhibition of anionic charges on viral particles. In this regard, it should be noted that the amino acid residue at position 145 of the VP1 protein (E, Q, or G) is known to play a critical role during PSGL-1 binding. While the presence of an E residue abrogates binding of VP1 to PSGL-1, Q or G residues allow the interaction between EV-A71 and host cells (28). Both the EV-A71 TW/2231 and the 5865/sin/000009 viruses used in this study carried the VP1-Q145 variant. Thus, we assessed whether PSGL-1 beads were able to pull down EV-A71 particles (Fig. 3 and 6). We found that 3,4-DCQA effectively inhibited binding between the VP1-E98G/P246A DM variant and PSGL-1 (Fig. 6). None of the resistant viruses selected in our study were capable of interacting with PSGL-1, possibly because this receptor is mainly expressed in myeloid cells and not in RD cells (34). Notably, the VP1-E98G/P246A DM variant retained its ability to bind HS, thus being insensitive to 3,4-DCQA inhibition (Fig. 6). The E98/P246 VP1 residues are located in the 5-fold axis (Fig. 7), and six surface loops (termed BC, DE, BE, GF, GH, and HI) have been identified in this structure (35). The P246 VP1 residue is evolutionarily conserved in most EV-A71 strains, and it is located within the HI loop, which is known to interact with the uncoating regulator cyclophilin A (36). We thus reasoned that the P246 of VP1 residue could be involved in EV-A71 uncoating, but not in HS binding. However, Tan et al. (27) have previously shown that a VP1-P246S variant reduced the capacity of EV-A71 to interact with HS. Here, we found that viruses harboring the VP1-P246A variant did not differ from wild-type viruses in their capacity to bind HS in the absence of 3,4-DCQA (Fig. 6A, lane 7). These results suggest that the P246 VP1 residue most likely plays a role during uncoating, whereas its role in mediating HS binding appears non-influential. Conversely, the amino acid residue at position 98 of VP1 may be critical for mediating HS binding. In this regard, we found that the VP1-E98G mutant showed a higher affinity for HS, which was reflected by 3,4-DCQA resistance (Fig. 6A, lane 8). Intriguingly, the VP1-E98G variant effectively restored the capacity of the VP1-K242A mutant to bind HS, which was originally absent (27).

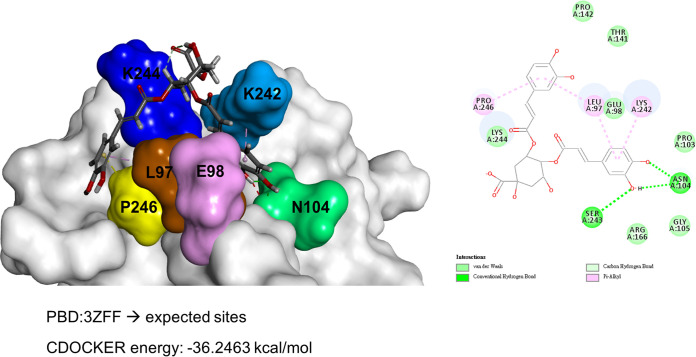

FIG 7.

Structural docking of 3,4-DCQA and the EV-A71 VP1 protein. The expected binding site of 3,4-DCQA in the 5-fold axis of VP1 (PBD ID: 3ZFF) was predicted using Discovery Studio software. Amino acid residues which play crucial roles in the binding process are highlighted with different colors.

The mechanisms by which 3,4-DCQA binds to the 5-fold axis do not seem to involve electrostatic interactions, ultimately differing from those reported for suramin and NF449. Recently, Sun et al. (37) described a new tryptophan dendrimer inhibitor (termed MADAL385) that is capable of binding to each unit of the 5-fold axis, thereby preventing EV-A71 entry into host cells. Unlike MADAL385, which causes a massive steric block of the 5-fold axis, 3,4-DCQA had limited interactions with only two residues (VP1 E98 and P246). While 3,4-DCQA is not structurally related to MADAL385, it is noteworthy that viruses resistant to both compounds were found to carry a mutation at the P246 residue. Molecular docking analysis revealed that 3,4-DCQA targets VP1 to form a stable structure through noncovalent and van der Waals interactions. The CDOCKER interaction energy between the caffeyol groups in 3,4-DCQA and the E98/P246 residues in VP1 was −36.2463 kcal/mol (Fig. 7). RA is another compound derived from natural sources which shares structural similarities with 3,4-DCQA (chemical structure in Fig. 1A). We have previously shown that RA carries out its anti-EV-A71 activity by blocking the HS-VP1 interaction (21). We also found that RA targets the residue N104 in the BC loop of VP1 within the 5-fold axis. Therefore, while the two compounds have structural similarities, they exert their anti-EV-A71 activity by binding with different amino acid residues (21).

In light of these findings, we propose that 3,4-DCQA disrupts EV-A71 binding to HS by targeting the VP1-E98 residue in the 5-fold axis, an event which eventually prevents virus entry into host cells. 3,4-DCQA may also suppress viral uncoating by targeting the P246 residue within the VP1 structural protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human RD cells prepared in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were cultured in E10 medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. EV-A71 strain 2231 (TW/2231/98) was generated by reverse genetics of an infectious plasmid (kindly provided by Mei-Shang Ho). The strain had a glutamic acid residue at position 145 of the VP1 capsid protein (VP1-145E; low HS affinity) that was highly prone to mutate to glutamine (Q) (VP1-145Q; high HS affinity) during the passaging of viruses in cell cultures. Thus, all wild-type and resistant viruses used for subsequent compound screening and mechanistic studies had a glutamine at position 145 of the VP1 capsid protein. Similarly, EV-A71 subgenotype B4 strain 41 (5865/Sin/000009; GenBank accession no. AF316321) and its VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A mutants carried the VP1-145Q variant (27). Influenza viruses obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) were amplified in MDCK cells maintained in DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Gibco), penicillin, and streptomycin (12).

Extraction and isolation of 3,4-DCQA from I. kaushue.

After obtaining appropriate genome verification of plant materials, preparation of I. kaushue water extract and isolation of 3,4-DCQA were performed as previously described (25).

Inhibition of EV-A71-induced cytopathic effect and cytotoxicity assays.

RD cells were seeded in a 96-well tissue culture plate and infected with EV-A71 (9 × TCID50 [50% tissue culture infective dose]) as previously reported (38). The cells protected by 3,4-DCQ were stained with 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) at room temperature, and the density of staining was measured in a microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, USA). The concentration of 3,4-DCQA that inhibited virus-induced CPE by 50% (EC50) was calculated with the Reed-Muench method. Cytotoxicity of the compound was also determined using an MTT assay. To this aim, RD cells were incubated with serially diluted compounds at 37°C for 72 h (38).

Microscopic assessment of inhibition of cytopathic effect by 3,4-DCQA.

RD cells were seeded in a 6-well tissue culture plate and incubated with EV-A71 TW/2231/1998 for 1 h. After exposure to 3,4-DCQA (50 μM) for 1 h, cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and maintained in E2 medium (DMEM plus 2% FBS). The antiviral effect of 3,4-DCQA was assessed by microscopic examination at 24 hpi.

Time-of-addition assay.

RD cells were seeded in a 6-well tissue culture plate and maintained for 16 to 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Subsequently, cells were treated with 3,4-DCQA (50 μM in E2 medium) at different time points, as follows: (i) pre-adsorption phase (between −3 and −1 hpi), (ii) adsorption phase (between −1 and 0 hpi), and (iii) post-adsorption phase (after 0 hpi.). During the adsorption phase (between −1 and 0 hpi), cells were exposed to EV-A71 TW/2231/1998 (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1) for 1 h. After removal of the culture medium, cells were washed twice with DPBS. After two washes in DPBS, cells were harvested at 8 hpi and virus titers were determined with a plaque assay (24).

Centrifugal filtration inactivation assay.

Viruses (5 × 104 PFU) were mixed on ice with the reported concentrations of 3,4-DCQA for 1 h. The virus/compound mixture was filtered through an Amicon centrifuge (catalog no. UFC8100, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; molecular weight cutoff: 100 kDa) at 500 × g for 30 min at 4°C to separate the retained and unbound fractions. Following virus collection, the remaining titers were determined with a plaque assay (12).

Attachment inhibition and penetration inhibition assays.

Attachment inhibition and penetration inhibition assays were performed as previously described, with slight modifications (38). In brief, the attachment assay was carried by mixing EV-A71 TW/2231/1998 viruses or recombinant viruses (5 × 104 PFU) with DMEM containing penicillin, streptomycin, and 3,4-DCQA (50 μM) on ice for 1 h. Subsequently, RD cells were incubated on ice with the virus/compound mixture for 1 h. The penetration assay was performed by infecting RD cells on ice for 1 h. Cells were subsequently washed and incubated with 3,4-DCQA (50 μM) in E2 medium at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 h. After a washing step with cold DPBS, cells were trypsinized to remove residual viruses from the surface. RNA extracted from cells was submitted for RT-qPCR analysis using specific primers for VP2 (Table 4). To distinguish virus binding from penetration into host cells, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy was performed. After overnight incubation, RD cells on a coverslip placed in a 6-well dish (2 × 105 cells per well) were precooled on ice for 30 min and subsequently inoculated with EV-A71 (MOI = 50) on ice for 1 h to promote viral attachment without inducing penetration. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min to promote viral endocytosis either in presence or absence of 3,4-DCQA (50 μM). After washing with PBS, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehye in PBS prior to further processing for immunofluorescence. Fixed cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-EV-A71 VP1 antibody (Genetex, GTX132338, 1:100 dilution) with the corresponding Alexa-568-conjugated secondary antibody, and mouse EEA1 antibody (BD-Transduction labs, catalog no. E41120, 1:100 dilution) with the corresponding Alexa-488-conjugated secondary antibody. Cells were counterstained with the nuclear dye Hoechst and observed under a laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM780). Afterwards, images were analyzed with IN Cell Investigator high-content analysis software (GE Healthcare) to determine the number of endocytic VP1 puncta and to examine the colocalization of VP1 and EEA1.

TABLE 4.

Primer sets for site-directed mutagenesis and RT-qPCRa

| Primers | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Site-directed mutagenesis | |

| VP1 E145Q/F | 5′-ATG CAC CCC TAC CGG GCA AGT TGT CCC GCA ATT G-3′ |

| VP1 E145Q/R | 5′-CAA TTG CGG GAC AAC TTG CCC GGT AGG GGT GCA T-3′ |

| VP1 E98G/F | 5′-GAG ATA GAC CTC CCT CTT GGA GGC ACA ACC AAC CCG-3′ |

| VP1 E98G/R | 5′-CGG GTT GGT TGT GCC TCC AAG AGG GAG GTC TAT CTC-3′ |

| VP1 P246A/F | 5′-GGC ACC TCG AAG TCC AAG TAC GCA TTG GTG ATC AGG AT-3′ |

| VP1 P246A/R | 5′-ATC CTG ATC ACC AAT GCG TAC TTG GAC TTC GAG GTG CC-3′ |

| RT-qPCR | |

| GAPDH/F | 5′-TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC TTA G-3′ |

| GAPDH/R | 5′-GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GAG-3′ |

| 2231/VP2/F | 5′-CTG ATG GCT TCG AAT TGC AA-3′ |

| 2231/VP2/R | 5′-GCG TTT ATG TAC GGC ACT ATT ATT-3′ |

| 5865/F | 5′-GAG CTC TAT AGG AGA TAG TGT GAG TAG GGC-3′ |

| 5865/R | 5′-ATG ACT GCT CAC CTG CGT GTT-3′ |

Underlined nucleotides represent the position of the mutation.

Heparan sulfate receptor in vitro pulldown.

HS agarose (Sigma-Aldrich; H6508) was washed twice with PBS and centrifuged at 20 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Subsequently, EV-A71 (strain 2231 and its variants) in E2 medium (20 μg) was incubated on ice with DMSO, NF449 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or 3,4-DCQA for 1 h. Following the addition of immobilized HS beads, the mixture was kept on ice for 2 h, washed three times with DPBS, and centrifuged at 20 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Precipitated viruses were quantified by Western blotting using anti-EV-A71 antibodies (1:1,000 dilution, ab36367; Abcam). The VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A mutations of 5865/sin/000009 strain were unstable and readily reverted to the wild-type sequence or resulted in different compensatory mutations. Therefore, for the purpose of pulldown assays, we used recombinant viruses from the P1 passage (27). HS pulldown assays for the VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A variants were performed using equal amounts of RNA from the wild-type 5865/sin/000009 strain and its derived variants (VP1-K242A and VP1-K244A), obtained from sequence-verified, passage P1 viruses using cDNA clones as source material (50 μL) (27). RT-qPCR quantification of precipitated virus was carried out against a standard viral RNA curve (38). Primers and conditions for RT-qPCR have been previously described (27).

3,4-DCQA-resistant virus selection and recombinant virus generation.

Selection of resistant viruses was accomplished as previously reported (12). In brief, RD cells were incubated with EV-A71 2231 in the presence of 3,4-DCQA (initial concentration: 25 μM, increased 2-fold at each step). Stable resistant viruses were selected through seven passages at a final 400 μM. DMSO and 3,4-DCQA escape mutants were purified on plaques before RNA extraction and sequencing. Recombinant mutant viruses were generated through site-direct mutagenesis (QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using specific primers (Table 4). According to a previously described methodology (12), RNA obtained from in vitro transcription of an infectious plasmid was transfected into RD cells to generate recombinant viruses.

3,4-DCQA/PR66 and 3,4-DCQA/3,5-DCQA combination assay.

RD cells were seeded in a 96-well tissue culture plate. An EV-A71-induced cell death inhibition assay was initially carried out to determine the EC50 for 3,5-DCQA and PR66. Subsequently, 3,4-DCQA at a fixed concentration was combined with PR66 or 3,5-DCQA at different concentrations to determine the EC50 for PR66 or 3,5-DCQA. The CI was calculated to investigate drug-drug interactions, as follows: CI = CA,50/EC50,A + CB,50/EC50,B, where EC50,A and EC50,B indicate the EC50 for drugs A and B, respectively; and CA,50 denotes the EC50 of drug A at a fixed concentration and drug B at different concentrations (39). The results were interpreted as follows: CI = 1, additive effect; CI < 1, synergistic effect; CI > 1, antagonistic effect.

PSGL1 or SCARB2 pulldown assay.

Dynabeads (Protein G Mag Sepharose Xtra; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) were washed twice with E5 (DMEM + 5% FBS + 0.01% Tween 20) and incubated on ice for 1 h with recombinant PSGL-1-hFc (1 μg, 3345-PS; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or SCARB2-hFc (1 μg, 1996-LM; R&D Systems) antibodies. After two washes in E5, EV-A71 in E2 (20 μg) was mixed on ice for 1 h with DMSO or 3,4-DCQA. The mixture was incubated on ice for 2 h following the addition of dynabeads. Afterwards, beads were washed three times with E5 using a magnetic plate. Precipitated viruses were quantified by Western blotting using antibodies against EV-A71, SCARB2, or PSGL1. Goat anti-SCARB2 (1:1,000 dilution) and mouse anti-PSGL1 (1:1,000 dilution) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Simulation of molecular interaction between EV-A71 VP1 and 3,4-DCQA.

In silico docking studies on the Discovery Studio 4.1 platform (Biovia, San Diego, CA, USA) were performed to investigate the interaction between 3,4-DCQA and the 5-fold axis of EV-A71. The three-dimensional structure of 3,4-DCQA was reconstructed using Chem 3D Professional 15.0 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), whereas the EV-A71 crystal structure (PDB ID: 3ZFF) was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The initial structures for VP1 and 3,4-DCQA were created using the CHARMm force field and subsequently minimized. A sphere radius of 30 Å was set and assigned to the surface of the binging site on three different loops (P96-G105, D164-L169, and V238-245). Using the CDOCKER protocol of Discovery Studio 4.1, various chemical conformations of 3,4-DCQA were generated and docked.

Data analysis.

Quantitative data were analyzed with a Student’s t test, and are presented as means ± standard deviations. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Kuo-Ming Lee for sequence analysis. We also acknowledge Ingrid Kuo and the Center for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (supported by grant no. CLRPG3D0046) of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for creating the illustrations.

This study was financially supported by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan (grants BMRP416, CMRPD1E0041-3, CMRPD1G0301-3, and CMRPD1F0581-3) and the Taiwanese Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grants 106-2320-B-182-004-MY3, 106-2811-B-182-011, 106-2632-B-182-001, and 107-2811-B-182-512). This research also received funding from the Research Center for Emerging Viral Infections (Featured Areas Research Center Program) within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project, conducted under the auspices of the Taiwanese Ministry of Education and the Taiwanese Ministry of Science and Technology (grant MOST 108-3017-F-182-001).

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Jim-Tong Horng, Email: jimtong@mail.cgu.edu.tw.

Colin R. Parrish, Cornell University

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown BA, Pallansch MA. 1995. Complete nucleotide sequence of enterovirus 71 is distinct from poliovirus. Virus Res 39:195–205. 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Racaniello VR. 2007. Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 795–838. In Knipe DavidM, Martin MalcolmA., Martin DianeE, Griffin RobertA, Lamb Bernard, Roizman, Straus Stephen E (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plevka P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2012. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science 336:1274. 10.1126/science.1218713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamayoshi S, Fujii K, Koike S. 2014. Receptors for enterovirus 71. Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e53. 10.1038/emi.2014.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggen J, Thibaut HJ, Strating J, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2018. The life cycle of non-polio enteroviruses and how to target it. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:368–381. 10.1038/s41579-018-0005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S. 2009. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:798–801. 10.1038/nm.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koike S. 2009. [Identification of an enterovirus 71 receptor; SCARB2]. Uirusu 59:189–194. 10.2222/jsv.59.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou D, Zhao Y, Kotecha A, Fry EE, Kelly JT, Wang X, Rao Z, Rowlands DJ, Ren J, Stuart DI. 2019. Unexpected mode of engagement between enterovirus 71 and its receptor SCARB2. Nat Microbiol 4:414–419. 10.1038/s41564-018-0319-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamayoshi S, Ohka S, Fujii K, Koike S. 2013. Functional comparison of SCARB2 and PSGL1 as receptors for enterovirus 71. J Virol 87:3335–3347. 10.1128/JVI.02070-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang M, Wang X, Wang Q, Wang Y, Lin J, Sun Y, Li X, Zhang L, Lou Z, Wang J, Rao Z. 2014. Molecular mechanism of SCARB2-mediated attachment and uncoating of EV71. Protein Cell 5:692–703. 10.1007/s13238-014-0087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachos C, Blanz J, Saftig P, Schwake M. 2012. A critical histidine residue within LIMP-2 mediates pH sensitive binding to its ligand beta-glucocerebrosidase. Traffic 13:1113–1123. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho JY, Chern JH, Hsieh CF, Liu ST, Liu CJ, Wang YS, Kuo TW, Hsu SJ, Yeh TK, Shih SR, Hsieh PW, Chiu CH, Horng JT. 2016. In vitro and in vivo studies of a potent capsid-binding inhibitor of enterovirus 71. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1922–1932. 10.1093/jac/dkw101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiwari V, Tarbutton MS, Shukla D. 2015. Diversity of heparan sulfate and HSV entry: basic understanding and treatment strategies. Molecules 20:2707–2727. 10.3390/molecules20022707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thacker BE, Xu D, Lawrence R, Esko JD. 2014. Heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfation: a rare modification in search of a function. Matrix Biol 35:60–72. 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlasak M, Goesler I, Blaas D. 2005. Human rhinovirus type 89 variants use heparan sulfate proteoglycan for cell attachment. J Virol 79:5963–5970. 10.1128/JVI.79.10.5963-5970.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zautner AE, Korner U, Henke A, Badorff C, Schmidtke M. 2003. Heparan sulfates and coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor: each one mediates coxsackievirus B3 PD infection. J Virol 77:10071–10077. 10.1128/jvi.77.18.10071-10077.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Shi J, Ye X, Ku Z, Zhang C, Liu Q, Huang Z. 2017. Coxsackievirus A16 utilizes cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans as its attachment receptor. Emerg Microbes Infect 6:e65. 10.1038/emi.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baggen J, Liu Y, Lyoo H, van Vliet ALW, Wahedi M, de Bruin JW, Roberts RW, Overduin P, Meijer A, Rossmann MG, Thibaut HJ, van Kuppeveld FJM. 2019. Bypassing pan-enterovirus host factor PLA2G16. Nat Commun 10:3171. 10.1038/s41467-019-11256-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arita M, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2008. Characterization of pharmacologically active compounds that inhibit poliovirus and enterovirus 71 infectivity. J Gen Virol 89:2518–2530. 10.1099/vir.0.2008/002915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan CW, Poh CL, Sam IC, Chan YF. 2013. Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. J Virol 87:611–620. 10.1128/JVI.02226-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh CF, Jheng JR, Lin GH, Chen YL, Ho JY, Liu CJ, Hsu KY, Chen YS, Chan YF, Yu HM, Hsieh PW, Chern JH, Horng JT. 2020. Rosmarinic acid exhibits broad anti-enterovirus A71 activity by inhibiting the interaction between the five-fold axis of capsid VP1 and cognate sulfated receptors. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:1194–1205. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1767512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho M, Chen ER, Hsu KH, Twu SJ, Chen KT, Tsai SF, Wang JR, Shih SR. 1999. An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. Taiwan Enterovirus Epidemic Working Group. N Engl J Med 341:929–935. 10.1056/NEJM199909233411301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin TY, Liu YC, Jheng JR, Tsai HP, Jan JT, Wong WR, Horng JT. 2009. Anti-enterovirus 71 activity screening of Chinese herbs with anti-infection and inflammation activities. Am J Chin Med 37:143–158. 10.1142/S0192415X09006734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong WR, Chen YY, Yang SM, Chen YL, Horng JT. 2005. Phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK in an early entry step of enterovirus 71. Life Sci 78:82–90. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen YL, Hwang TL, Yu HP, Fang JY, Chong KY, Chang YW, Chen CY, Yang HW, Chang WY, Hsieh PW. 2016. Ilex kaushue and its bioactive component 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid protected mice from lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Sci Rep 6:34243. 10.1038/srep34243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura Y, McLaughlin NP, Pan J, Goldstein S, Hafenstein S, Shimizu H, Winkler JD, Bergelson JM. 2015. The suramin derivative NF449 interacts with the 5-fold vertex of the enterovirus A71 capsid to prevent virus attachment to PSGL-1 and heparan sulfate. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005184. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan CW, Sam IC, Lee VS, Wong HV, Chan YF. 2017. VP1 residues around the five-fold axis of enterovirus A71 mediate heparan sulfate interaction. Virology 501:79–87. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura Y, Lee H, Hafenstein S, Kataoka C, Wakita T, Bergelson JM, Shimizu H. 2013. Enterovirus 71 binding to PSGL-1 on leukocytes: VP1-145 acts as a molecular switch to control receptor interaction. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003511. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J, Yi H, Zhao ZX, Shang XY, Zhu MJ, Kuang GJ, Zhu CC, Zhang L. 2018. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative evaluation of Ilex kudingcha C. J. Tseng by using UPLC and UHPLC-qTOF-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal 155:15–26. 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Z, Ding Y, Cao L, Ding G, Wang Z, Xiao W. 2017. Isochlorogenic acid C prevents enterovirus 71 infection via modulating redox homeostasis of glutathione. Sci Rep 7:16278. 10.1038/s41598-017-16446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S, Li G, Wang Y, Gao Q, Wang Y, Cui R, Altmeyer R, Zou G. 2016. Identification of positively charged residues in enterovirus 71 capsid protein VP1 essential for production of infectious particles. J Virol 90:741–752. 10.1128/JVI.02482-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meneghetti MC, Hughes AJ, Rudd TR, Nader HB, Powell AK, Yates EA, Lima MA. 2015. Heparan sulfate and heparin interactions with proteins. J R Soc Interface 12:e0589. 10.1098/rsif.2015.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Qing J, Sun Y, Rao Z. 2014. Suramin inhibits EV71 infection. Antiviral Res 103:1–6. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin YW, Lin HY, Tsou YL, Chitra E, Hsiao KN, Shao HY, Liu CC, Sia C, Chong P, Chow YH. 2012. Human SCARB2-mediated entry and endocytosis of EV71. PLoS One 7:e30507. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan J, Shen L, Wu J, Zou X, Gu J, Chen J, Mao L. 2018. Enterovirus A71 proteins: structure and function. Front Microbiol 9:286. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qing J, Wang Y, Sun Y, Huang J, Yan W, Wang J, Su D, Ni C, Li J, Rao Z, Liu L, Lou Z. 2014. Cyclophilin A associates with enterovirus-71 virus capsid and plays an essential role in viral infection as an uncoating regulator. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004422. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun L, Lee H, Thibaut HJ, Lanko K, Rivero-Buceta E, Bator C, Martinez-Gualda B, Dallmeier K, Delang L, Leyssen P, Gago F, San-Felix A, Hafenstein S, Mirabelli C, Neyts J. 2019. Viral engagement with host receptors blocked by a novel class of tryptophan dendrimers that targets the 5-fold-axis of the enterovirus-A71 capsid. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007760. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CW, Leu YL, Horng JT. 2012. Daphne genkwa Sieb. et Zucc. water-soluble extracts act on enterovirus 71 by inhibiting viral entry. Viruses 4:539–556. 10.3390/v4040539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao L, Au JL, Wientjes MG. 2010. Comparison of methods for evaluating drug-drug interaction. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2:241–249. 10.2741/e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]