Resumo

Fundamento

A hipercolesterolemia familiar (HF) é uma doença genética dominante que se caracteriza por níveis sanguíneos elevados de colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL-C), e está associada à ocorrência de doença cardiovascular precoce. No Brasil, o HipercolBrasil, que é atualmente o maior programa de rastreamento em cascata para HF, já identificou mais de 2.000 indivíduos com variantes genéticas causadoras de HF. A abordagem padrão baseia-se no rastreamento em cascata de casos índices referidos, indivíduos com hipercolesterolemia e suspeita clínica de HF.

Objetivos

Realizar rastreamento direcionado de 11 pequenos municípios brasileiros com suspeita de alta prevalência de indivíduos com HF.

Métodos

A seleção dos municípios ocorreu de 3 maneiras: 1) municípios em que houve suspeita de efeito fundador (4 municípios); 2) municípios em uma região com altas taxas de infarto do miocárdio precoce, conforme descrito pelo banco de dados do Sistema Único de Saúde (2 municípios); e 3) municípios geograficamente próximos a outros municípios com alta prevalência de indivíduos com HF (5 municípios). A significância estatística foi considerada como valor p < 0,05.

Resultados

Foram incluídos 105 casos índices e 409 familiares de primeiro grau. O rendimento dessa abordagem foi de 4,67 familiares por caso índice, o qual é significativamente melhor (p < 0,0001) do que a taxa geral do HipercolBrasil (1,59). Identificamos 36 CIs com variante patogênica ou provavelmente patogênica para HF e 240 familiares de primeiro grau afetados. Conclusão: Nossos dados sugerem que, uma vez detectadas, regiões geográficas específicas justificam uma abordagem direcionada para a identificação de aglomerações de indivíduos com HF.

Keywords: Hipercolesterolemia Familiar, Testes Genéticos, Doenças Cardiovasculares

Introdução

Hipercolesterolemia familiar (HF) é uma doença autossômica dominante que se caracteriza clinicamente por níveis sanguíneos elevados de colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL-C), e está associada à ocorrência de doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica (DCVA) precoce.1,2

A prevalência da HF no mundo é estimada em aproximadamente 1:250 na forma heterozigótica e 1:600.000 na forma homozigótica.3 Um estudo realizado pela coorte ELSA-Brasil estimou que a prevalência de indivíduos com os critérios clínicos para a HF no Brasil seria de 1:263. Considerando essas estimativas, haveria aproximadamente 760.000 pessoas com HF no Brasil.4

Porém, embora seja relativamente frequente, a forma heterozigótica ainda é uma doença subdiagnosticada.5 Para auxiliar na identificação de indivíduos com essa doença, tem sido utilizado o rastreamento genético em cascata em vários países, como a Holanda,6 o Reino Unido7 e a Espanha.8 Este método já foi reconhecido como sendo de custo efetivo para a identificação e a prevenção de DCVA precoce em indivíduos com a HF.9,10

No Brasil, o HipercolBrasil, que é atualmente o maior programa de rastreamento genético em cascata, existe desde 201211 e já identificou mais de 2.000 indivíduos com variantes genéticas causadoras de HF. O programa atualmente realiza testes genéticos em qualquer indivíduo com LDL-C ≥ 230 mg/dL (caso índice [CI])12 e nos familiares de primeiro grau daquelas com variantes patogênicas ou provavelmente patogênicas.

Entre julho de 2017 e julho de 2019, testamos uma nova metodologia para identificar novos indivíduos com mutações genéticas para HF, direcionada a pequenos municípios com prevalência potencialmente alta de HF.

O presente estudo descreve os primeiros resultados de triagem direcionada em 11 pequenos municípios brasileiros (até 60.000 habitantes) com suspeita de alta prevalência de pessoas com HF.

Métodos

O estudo foi realizado no Laboratório de Genética e Cardiologia Molecular do Instituto do Coração (InCor) da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Brasil. O protocolo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética Institucional (CAPPesq protocolo l00594212.0.1001.0068).

Amostra do estudo

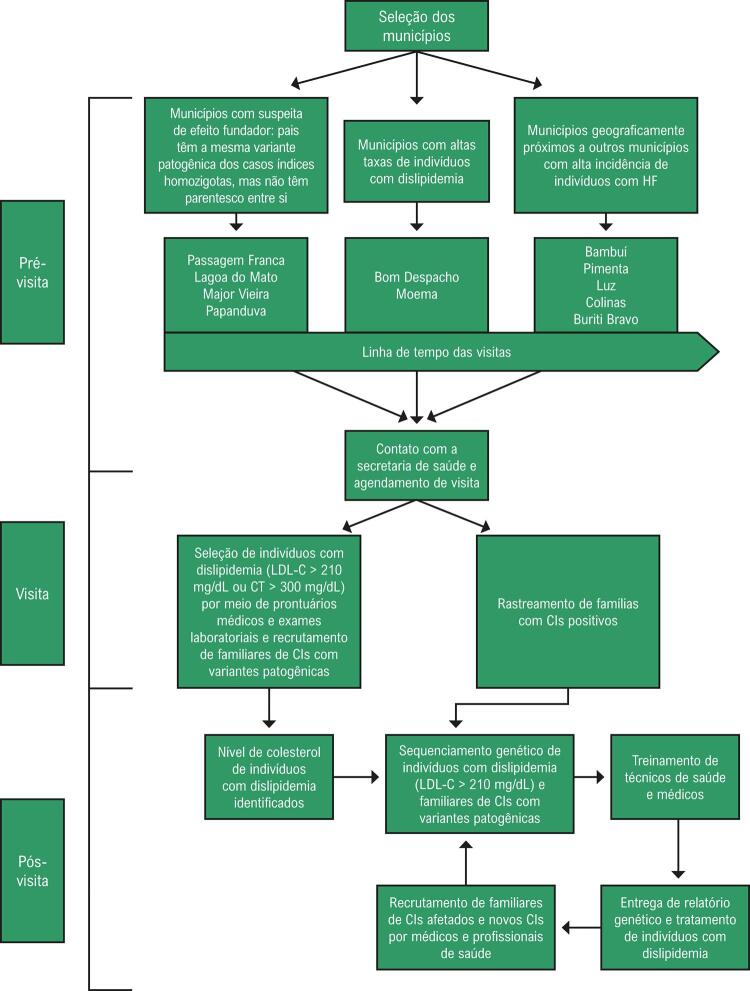

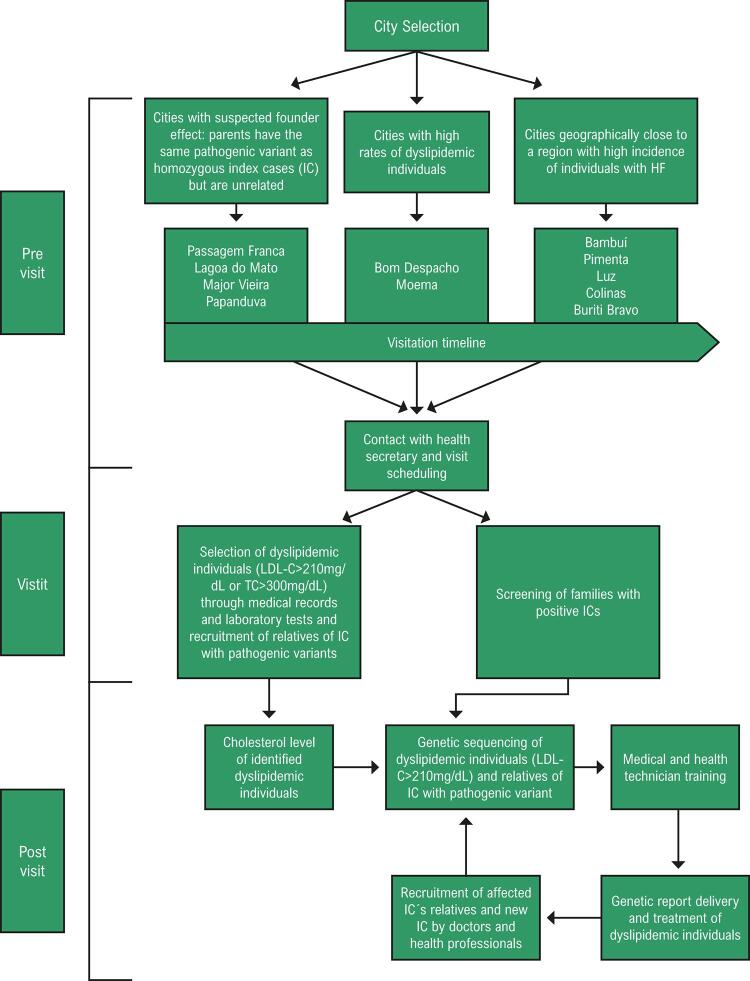

A Figura 1 mostra os critérios de inclusão e o desenho do estudo. Cadastramos indivíduos de 11 municípios selecionados com até 60.000 habitantes em todo o território brasileiro. A seleção dos municípios ocorreu de 3 maneiras: 1) municípios em que houve suspeita de efeito fundador, ou seja, ocorrência de indivíduos homozigotos, mas sem histórico de qualquer grau de parentesco entre os pais (Major Vieira, Papanduva, Lagoa do Mato e Passagem Franca); 2) municípios em uma região com altas taxas de dislipidemia, conforme relatado por médicos locais (Bom Despacho e Moema);13 e 3) municípios geograficamente próximos a outros municípios com alta prevalência de indivíduos com HF (Bambuí, Pimenta, Luz, Colinas e Buriti Bravo).

Figura 1. – Metodologia para selecionar municípios, identificar CIs e familiares e treinar profissionais de saúde para continuar o rastreamento genético em cascata.

Registro de casos índices e familiares

Em todos os municípios, foi feito um contato inicial com a secretaria saúde local de para explicar o projeto e estabelecer um acordo sobre a parceria. Foi feito contato por telefone antes de visitar cada município e realizado um acordo entre ambas as partes por e-mail. Já no município, a equipe foi atendida por um agente de saúde indicado pela secretaria de saúde. Nos municípios onde havia evidências de efeito fundador e naquelas onde havia relato de alta incidência de dislipidemia, a coleta de amostras começou com familiares de CIs previamente selecionados. Nesses municípios, também ocorreu uma busca ativa para novos CIs a partir de prontuários e exames de colesterol realizados nos laboratórios de análise clínica das unidades de saúde locais. Indivíduos foram considerados CIs quando apresentavam colesterol total > 300 mg/dL e/ou LDL-C ≥ 210 mg/dL com triglicerídeos < 300 mg/dL. Nestes casos, foi coletada uma amostra de sangue para realização de uma segunda dosagem do colesterol em nosso laboratório. Aqueles com LDL-C confirmado ≥ 210 mg/dL na segunda dosagem foram selecionados para o sequenciamento genético, enquanto os indivíduos que não atingiram este valor receberam laudo com os valores de colesterol total e as frações e foram excluídos do estudo.

Sequenciamento genético e rastreamento em cascata

Foram coletadas as amostras de sangue (10 ml de sangue periférico em tubos de EDTA) e enviadas ao Laboratório de Genética e Cardiologia Molecular do InCor/HCFMUSP para análise genética. Foi extraído o DNA genômico usando QIAamp DNA MiniKit (QIAGEN), seguindo as instruções do fabricante. Os CIs foram sequenciados por sequenciamento de próxima geração em um painel de genes incluindo os seguintes genes relacionados à dislipidemia: LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, LDLRAP1, STAP1, LIPA, APOE, ABCG5 e ABCG8. Foram realizadas as análises bioinformáticas em Varstation e CLC Genomic Workbench 9.0 (QIAGEN). A amplificação multiplex de sondas dependente de ligação (MLPA) em LDLR foi usada para rastrear variantes de número de cópias dos CIs sem qualquer tipo de variantes do tipo missense, nonsense ou frameshift identificadas no sequenciamento de próxima geração. Foi realizado o rastreamento de familiares com sequenciamento Sanger (para mutações pontuais ou pequenos indels) ou MLPA (para variantes de número de cópias). As variantes foram classificadas de acordo com as recomendações do American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.14

Análise de dados

A análise visual da distribuição das variáveis foi realizada por meio de histogramas e foi verificada a normalidade dos dados. Para variáveis contínuas com distribuição normal, foram calculados a média e o desvio padrão. As variáveis categóricas são mostradas como frequências. As diferenças entre as frequências foram comparadas pelo teste de qui-quadrado. Foram comparadas as diferenças entre as médias com o teste t de Student não pareado ou ANOVA unilateral, se necessário. As variáveis testadas apresentaram distribuição normal e optamos pelo teste paramétrico. A significância estatística foi considerada como valor p < 0,05. As análises estatísticas foram realizadas com SPSS v19.0 (IBM).

Resultados

Inicialmente, coletamos 230 CIs com pelo menos uma medida de colesterol que atendia aos critérios propostos (veja os Métodos). Porém, 125 deles apresentaram valores de LDL-C abaixo do ponto de corte após a segunda medição e não foi realizado sequenciamento posterior. No total, foram incluídos 105 ICs e 490 familiares na análise. A Tabela 1 mostra as características dos 11 municípios visitados, estado da federação brasileira, número de habitantes e data de cada visita. O município com o menor número de habitantes totais foi Moema com 7.028 e a maior foi Bom Despacho com 45.624, ambas no estado de Minas Gerais. Os primeiros municípios a serem visitados foram Major Vieira e Papanduva (setembro de 2017) e as últimas foram Buriti Bravo e Colinas (fevereiro de 2019).

Tabela 1. – Características gerais dos municípios da amostra.

| Município | Estado do Brasil | Habitantes totais (Censo do IBGE) | Data da visita | Número de casos esperados (1:263)4 | Número de casos positivos identificados |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bambuí | Minas Gerais | 22.709 | Dez 2018 | 86 | 2 |

| Bom Despacho | Minas Gerais | 45.624 | Ago 2018 | 173 | 45 |

| Buriti Bravo | Maranhão | 23.827 | Fev 2019 | 91 | 0 |

| Colinas | Maranhão | 42.196 | Fev 2019 | 160 | 4 |

| Lagoa do Mato | Maranhão | 10.955 | Abr 2018 | 42 | 32 |

| Luz | Minas Gerais | 17.492 | Dez 2018 | 67 | 6 |

| Major Vieira | Santa Catarina | 8.103 | Set 2017 | 31 | 47 |

| Moema | Minas Gerais | 7.028 | Ago 2018 | 27 | 36 |

| Papanduva | Santa Catarina | 18.013 | Set 2017 | 68 | 48 |

| Passagem Franca | Maranhão | 17.296 | Abr 2018 | 66 | 50 |

| Pimenta | Minas Gerais | 8.236 | Dez 2018 | 31 | 6 |

IBGE: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.

A Tabela 2 mostra o número de CIs e familiares sequenciados por região e seu genótipo em relação à presença de variantes patogênicas ou provavelmente patogênicas (positivos), sem variantes patogênicas (negativos) ou presença de uma variante de significado incerto (VSI), bem como o número de novos casos derivados de cada CI incluído.

Tabela 2. – CIs e familiares incluídos por região e seus genótipos para a presença de variantes genéticas de HF.

| Origem | CIs | Familiares | Número de familiares por CIs identificados | Número de indivíduos genotipados por município | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Negativo | Positivo | VSI | Negativo | Positivo | VSI | |||

| Bambuí | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Bom Despacho | 15 | 11 | 2 | 34 | 31 | 3 | 2,4 | 96 |

| Buriti Bravo | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Colinas | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0,5 | 12 |

| Lagoa do Mato | 3 | 2 | 0 | 25 | 30 | 0 | 11 | 60 |

| Luz | 21 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0,08 | 28 |

| Major Vieira | 1 | 3 | 0 | 48 | 44 | 0 | 23 | 96 |

| Moema | 1 | 4 | 0 | 36 | 32 | 0 | 13,6 | 73 |

| Papanduva | 4 | 2 | 1 | 50 | 46 | 0 | 13,7 | 103 |

| Passagem Franca | 3 | 5 | 0 | 55 | 45 | 0 | 12,5 | 108 |

| Pimenta | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0,4 | 13 |

| Total | 64 | 35 | 6 | 249 | 238 | 3 | 4,7 | 595 |

CI: caso índice; VSI: variante de significado incerto; HF: Hipercolesterolemia familiar.

A Tabela 3 mostra os três grupos de CIs (negativo, positivo ou VSI) e seus dados clínicos e bioquímicos. No total, foram sequenciados 105 CIs, sendo encontradas variantes patogênicas ou provavelmente patogênicas em 36 (37,8%) indivíduos e VSI em 5 (5,25%). A maioria dos CIs era do sexo feminino (67,6%) e quando as características clínicas e bioquímicas foram avaliadas entre os três grupos, houve, como esperado, uma diferença estatisticamente significativa em relação ao colesterol total e LDL-C basais (não tratados), com o grupo positivo apresentando os maiores valores de colesterol total e LDL-C, 382 ± 150 mg/dL e 287 ± 148 mg/dL, respectivamente. A Tabela 4 mostra as características clínicas e bioquímicas dos familiares.

Tabela 3. – Características clínicas e bioquímicas de CIs negativos, positivos e alterados por VSI.

| CI negativo | (64) | CI positivo | (36) | CI com VSI | (5) | valor p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulheres % | 45 (70,3) | 64 | 21 (58,3) | 36 | 5 (100) | 5 | 0,134 |

| Homens % | 19 (29,7) | 64 | 15 (41,7) | 36 | - | 5 | |

| Idade (anos) | 54±15 | 64 | 44±19 | 36 | 56±16 | 5 | 0,015 |

| Uso de drogas hipolipemiantes | 32 (50,0) | 64 | 24 (66,7) | 36 | 3 (60,0) | 5 | 0,261 |

| DAC precoce | 2 (3,1) | 64 | 4 (11,1) | 36 | - | 5 | 0,297 |

| Xantomas | 3 (4,7) | 64 | 3 (8,3) | 36 | 1 (20,0) | 5 | 0,365 |

| Xantelasmas | 4 (6,3) | 64 | 1 (2,8) | 36 | - | 5 | 0,696 |

| Arco córneo | 2 (3,1) | 64 | 3 (8,3) | 36 | - | 5 | 0,345 |

| CT atual | 279±65 | 62 | 316±107 | 36 | 302±28 | 5 | 0,102 |

| LDL-C atual | 195±56 | 64 | 234±104 | 36 | 207±35 | 5 | 0,051 |

| CT basal | 322±33 | 60 | 382±150 | 32 | 305±43 | 5 | 0,008 |

| LDL-C basal | 233±24 | 59 | 287±148 | 34 | 229±20 | 4 | 0,022 |

CI: caso índice; CT: colesterol total; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; LDL-C: colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade; VSI: variante de significado incerto. DAC precoce definido como evento de doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica < 55 e 60 anos de idade em homens e mulheres, respectivamente; lipídios em mg/dL; lipídios basais = não tratados.

Tabela 4. – Características clínicas e bioquímicas dos familiares positivos e negativos.

| Familiares negativos | N (249) | Familiares positivos | N (240) | valor p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulheres % | 136 (54,6) | 249 | 135 (56,3) | 240 | 0,504 |

| Homens % | 113 (45,4) | 249 | 105 (43,8) | 240 | |

| Idade (anos) | 40±21 | 249 | 38±21 | 240 | 0,710 |

| Uso de drogas hipolipemiantes | 31 (12,4) | 249 | 93 (38,8) | 240 | 0,001 |

| DAC precoce | 2 (0,8) | 249 | 9 (3,8) | 240 | 0,034 |

| Xantomas | 6 (2,4) | 249 | 17 (7,1) | 240 | 0,013 |

| Xantelasmas | 11 (4,4) | 249 | 34 (14,2) | 240 | 0,001 |

| Arco córneo | 1 (0,4) | 249 | 9 (3,8) | 240 | 0,009 |

| CT atual | 198±51 | 114 | 309±86 | 127 | 0,001 |

| LDL-C atual | 124±42 | 192 | 233±75 | 198 | 0,001 |

| CT basal | 220±191 | 97 | 318±97 | 130 | 0,001 |

| LDL-C basal | 126±41 | 169 | 243±82 | 178 | 0,001 |

DAC: doença arterial coronariana; LDL-C: colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade; CT: colesterol total. DAC precoce definido como evento de doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica < 55 e 60 anos de idade em homens e mulheres, respectivamente; lipídios em mg/dL; lipídios basais = não tratados.

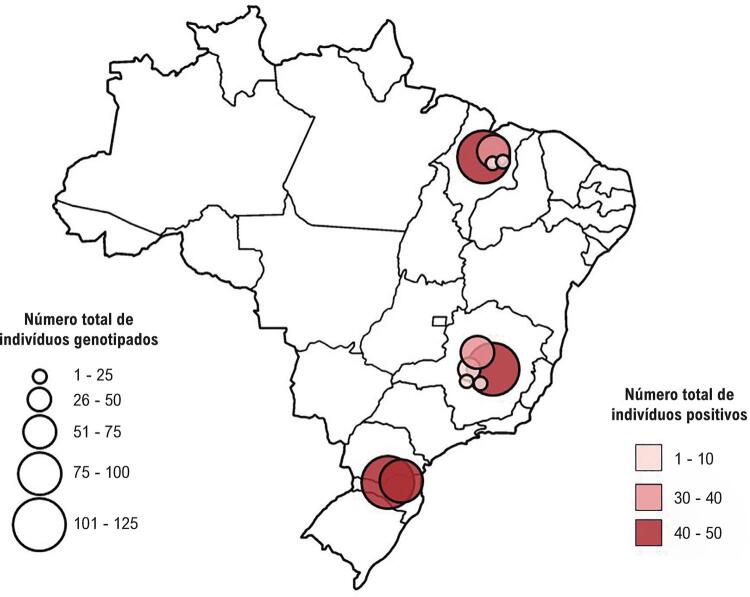

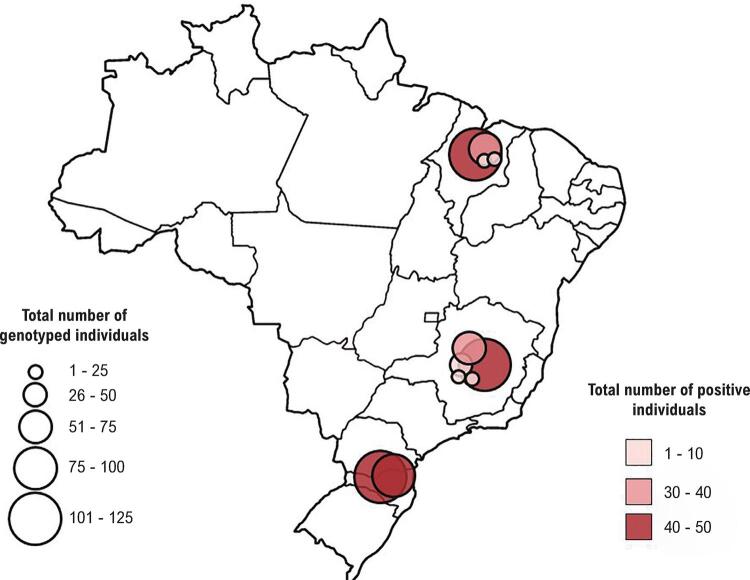

A Figura 2 mostra a distribuição geográfica dos 11 municípios localizados em 3 estados da federação brasileira, o número de casos registrados, o número de indivíduos genotipados e o número de indivíduos com uma variante patogênica.

Figura 2. – Distribuição geográfica dos casos, número de indivíduos genotipados e número de indivíduos com variante patogênica identificada (positivos).

Estados brasileiros, de cima para baixo: Maranhão, Minas Gerais e Santa Catarina

A Tabela 5 mostra todas as variantes encontradas e o local onde foram identificadas. No total, foram identificadas 21 variantes diferentes, com 3 variantes aparecendo com mais frequência. As frequências observadas para essas 3 variantes sugerem que elas têm efeitos fundadores nessas localidades. Foram encontrados 6 pacientes homozigotos e 1 heterozigoto composto em trans.

Tabela 5. – Variantes patogênicas, provavelmente patogênica e VSI de HF encontradas por município.

| Gene | Variante | Classificação da variantes | Bambuí | Bom Despacho | Luz | Pimenta | Moema | Buriti Bravo | Colinas | Lagoa do Mato | Passagem Franca | Major Vieira | Papanduva | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDLR | Duplicação do exon 4 para 8 (b) | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45b | 41 | 86 |

| LDLR | Duplicação do promoter para o exon 6 | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 29 | 49a | 0 | 0 | 83 |

| LDLR | p.Asp224Asn | Patogênica | 0 | 39 | 4 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77 |

| LDLR | p.Cys222* | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| LDLR | c.1359-1G >C | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| LDLR | p.Gly592Glu | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| LDLR | p.Ala771Val | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Pro699Leu | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Asp601His | Provavelmente patogênica | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| LDLR | p.Cys34Arg | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Arg257Trp | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Ser854Gly | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| LDLR | c.-228G>C | VSI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Ala30Gly | VSI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| APOB | p.Ala2790Thr | VSI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| APOB | p.Met499Val | VSI | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| PCSK9 | p.Arg237Trp | VSI | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| PCSK9 | p.Arg357Cys | VSI | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| STAP1 | p.Pro176Ser | VSI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LDLR | p.Cys222* | Patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1c | 1c |

| LDLR | Duplicação do exon 4 para 8 | Patogênica | ||||||||||||

| PCSK9 | p.Arg215Cys | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1c |

| APOB | p.Asp2213Asn | VSI | ||||||||||||

| APOB | p.Val3290Ile | VSI | ||||||||||||

| PCSK9 | p.Arg215Cys | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1c |

| APOB | p.Val3293lle | VSI | ||||||||||||

| PCSK9 | p.Arg215Cys | Provavelmente patogênica | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1c |

| APOB | p.Asp2213Asn | VSI |

2 homozigotas (b) 4 homozigotas (c) heterozigota composta em trans. VSI: variante de significado incerto; HF: Hipercolesterolemia familiar.

Discussão

O presente estudo descreve os resultados da implementação de um sistema de rastreamento em cascata para HF em 11 pequenos municípios brasileiros.

Apesar dos benefícios de custo conhecidos do rastreamento em cascata para HF, a implementação mundial tem sido abaixo do ideal. Diversas barreiras locais e obstáculos à implementação devem ser identificados e superados. A implementação do rastreamento em cascata em pequenas localidades, por exemplo, tem sido maiormente desconsiderado. Esse desafio é maior em países de dimensões continentais, como o Brasil, onde, além das enormes distâncias geográficas, existem desigualdades no acesso aos serviços de saúde. Descrevemos a experiência do HipercolBrasil que realizou rastreamento em cascata abrangente em pequenos municípios brasileiros. Neste novo modelo, o rastreamento genético em cascata foi realizado em municípios que apresentavam evidências de maior prevalência de HF devido ao achado prévio de indivíduos com o fenótipo homozigoto no mesmo município, ou porque essas regiões relataram elevada frequência de infarto do miocárdio.

Os municípios que apresentaram evidências de efeito fundador foram os que apresentaram maior identificação de indivíduos afetados por cada CI analisado (em ordem decrescente Major Vieira, Papanduva, Lagoa do Mato e Passagem Franca). Nestas cidades, começamos com indivíduos homozigotos cujos pais não tinham parentesco e nasceram em regiões geográficas diferentes. Obviamente, sempre que essa situação for sinalizada por um programa de rastreamento em cascata, ela merece a implantação de uma abordagem que abranja todo o município, pois os custos-benefícios deste cenário são os mais vantajosos. A implementação da cascata genética em municípios de pequeno porte mostrou-se mais eficiente quando comparada à cascata genética realizada pelo HipercolBrasil11 considerando que as taxas de familiares por CI foram de 4,7 e 1,6, respectivamente (p < 0,0001).

É importante notar que a taxa de familiares testados por CI também foi maior em municípios com suspeita de efeito fundador. Isso provavelmente ocorreu porque esses municípios possuíam um número pequeno de habitantes e a maioria dos familiares tinha algum grau de relação familiar. Isso não ocorreu em Bom Despacho, que é um município consideravelmente maior que os demais (45.624 habitantes) e, embora o número de familiares coletados tenha sido semelhante ao de outras cidades, houve maior número de CIs coletados (28), diminuindo a taxa de parentes/CI para 2,4. Essa situação exemplifica o equilíbrio tênue entre o tamanho do município e o sucesso da abordagem descrita.

Os municípios visitados que eram geograficamente próximos a municípios com suspeita de efeito fundador (Bambuí, Buriti Bravo, Colinas, Pimenta e Luz) apresentaram baixa captação de CIs e, consequentemente, baixo número de familiares identificados. Isso sugere que a concentração de esforços no município selecionado, ao invés de estender a abordagem para cidades próximas, deve ser priorizada e a captura de casos potenciais próximos deve ser deixada para o mecanismo usual de rastreamento em cascata.

Conclusão

Rastreamento em cascata em pequenos municípios (menos de 60.000 habitantes) com efeito fundador mostrou-se eficaz. Porém, alguns pontos podem ser de grande importância para que o rastreamento em cascata seja eficaz, podendo ser considerados os seguintes antes de decidir quais cidades rastrear: estabelecimento de uma parceria formal e interesse explícito por parte do departamento de saúde local em receber o programa e realizar o rastreamento em cascata; disponibilidade de conjuntos de dados laboratoriais de análises clínicas para a realização de levantamento retrospectivo dos testes de colesterol; e divulgação via rádios e redes sociais sobre a doença e o programa para maior adesão dos moradores.

O presente estudo é limitado pelo número relativo de municípios avaliados considerando o tamanho continental do Brasil. No entanto, sugere que a abordagem desenhada pode ser útil para detectar indivíduos com HF. Em conclusão, nossos dados sugerem que, uma vez detectadas, regiões geográficas específicas justificam uma abordagem direcionada para a identificação de aglomerações de indivíduos com HF.

Funding Statement

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por Amgen Biotechnology (grant number 682/2016)

Vinculação acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por Amgen Biotechnology (grant number 682/2016)

Referências

- 1.Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ, Robinson JG, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Screening, Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients: Clinical Guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3 Suppl):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed]; Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ, Robinson JG, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Screening, Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients: Clinical Guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.003.J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3) Suppl:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Graaf A, Kastelein JJP, Wiegman A. Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in Childhood: Cardiovascular Risk Prevention. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32(6):699. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1165-1. [DOI] [PubMed]; van der Graaf A, Kastelein JJP, Wiegman A. Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in Childhood: Cardiovascular Risk Prevention. 69910.1007/s10545-009-1165-1.J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32(6) doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ; National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Familial Hypercholesterolemias: Prevalence, Genetics, Diagnosis and Screening Recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3 Suppl):9-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.03.452. [DOI] [PubMed]; Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ, National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia Familial Hypercholesterolemias: Prevalence, Genetics, Diagnosis and Screening Recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.03.452.J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3) Suppl:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2011.03.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harada PH, Miname MH, Benseñor IM, Santos RD, Lotufo PA. Familial Hypercholesterolemia Prevalence in an Admixed Racial Society: Sex and RACE MATter. The ELSA-Brasil. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:273-7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed]; Harada PH, Miname MH, Benseñor IM, Santos RD, Lotufo PA. Familial Hypercholesterolemia Prevalence in an Admixed Racial Society: Sex and RACE MATter. The ELSA-Brasil. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.021.Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, Ginsberg HN, Masana L, Descamps OS, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolaemia is Underdiagnosed and Undertreated in the General Population: Guidance for Clinicians to Prevent Coronary Heart Disease: Consensus Statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(45):3478-90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, Ginsberg HN, Masana L, Descamps OS, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolaemia is Underdiagnosed and Undertreated in the General Population: Guidance for Clinicians to Prevent Coronary Heart Disease: Consensus Statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273.Eur Heart J. 2013;34(45):3478–3490. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umans-Eckenhausen MA, Defesche JC, Sijbrands EJ, Scheerder RL, Kastelein JJ. Review of First 5 Years of Screening for Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands. Lancet. 2001;357(9251):165-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03587-X. [DOI] [PubMed]; Umans-Eckenhausen MA, Defesche JC, Sijbrands EJ, Scheerder RL, Kastelein JJ. Review of First 5 Years of Screening for Familial Hypercholesterolaemia in the Netherlands. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03587-X.Lancet. 2001;357(9251):165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03587-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadfield SG, Horara S, Starr BJ, Yazdgerdi S, Marks D, Bhatnagar D, et al. Family Tracing to Identify Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: The Second Audit of the Department of Health Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Cascade Testing Project. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46(Pt 1):24-32. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.008094. [DOI] [PubMed]; Hadfield SG, Horara S, Starr BJ, Yazdgerdi S, Marks D, Bhatnagar D, et al. Family Tracing to Identify Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: The Second Audit of the Department of Health Familial Hypercholesterolaemia Cascade Testing Project. 10.1258/acb.2008.008094.Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:24–32. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.008094. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mozas P, Castillo S, Tejedor D, Reyes G, Alonso R, Franco M, et al. Molecular Characterization of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spain: Identification of 39 Novel and 77 Recurrent Mutations in LDLR. Hum Mutat. 2004;24(2):187. doi: 10.1002/humu.9264. [DOI] [PubMed]; Mozas P, Castillo S, Tejedor D, Reyes G, Alonso R, Franco M, et al. Molecular Characterization of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Spain: Identification of 39 Novel and 77 Recurrent Mutations in LDLR. 18710.1002/humu.9264.Hum Mutat. 2004;24(2) doi: 10.1002/humu.9264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sperlongano S, Gragnano F, Natale F, D’Erasmo L, Concilio C, Cesaro A, et al. Lomitapide in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Cardiology Perspective From a Single-Center Experience. J Cardiovasc Med. 2018;19(3):83-90. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed]; Sperlongano S, Gragnano F, Natale F, D’Erasmo L, Concilio C, Cesaro A, et al. Lomitapide in Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Cardiology Perspective From a Single-Center Experience. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000620.J Cardiovasc Med. 2018;19(3):83–90. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.0. Lázaro P, Isla LP, Watts GF, Alonso R, Norman R, Muñiz O, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of a Cascade Screening Program for the Early Detection of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(1):260-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lázaro P, Isla LP, Watts GF, Alonso R, Norman R, Muñiz O, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of a Cascade Screening Program for the Early Detection of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.01.002.J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(1):260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jannes CE, Santos RD, Silva PRS, Turolla L, Gagliardi ACM, Marsiglia JDC, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Brazil: Cascade Screening Program, Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(1):101-7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed]; Jannes CE, Santos RD, Silva PRS, Turolla L, Gagliardi ACM, Marsiglia JDC, et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Brazil: Cascade Screening Program, Clinical and Genetic Aspects. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.11.009Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(1):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos RD, Bourbon M, Alonso R, Cuevas A, Vasques-Cardenas NA, Pereira AC, et al. Clinical and Molecular Aspects of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Ibero-American Countries. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(1):160-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed]; Santos RD, Bourbon M, Alonso R, Cuevas A, Vasques-Cardenas NA, Pereira AC, et al. Clinical and Molecular Aspects of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Ibero-American Countries. 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.11.004.J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(1):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silvino JPP, Jannes CE, Tada MT, Lima IR, Silva IFO, Pereira AC, et al. Cascade Screening and Genetic Diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Clusters of the Southeastern Region from Brazil. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(12):9279-88. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-06014-0. [DOI] [PubMed]; Silvino JPP, Jannes CE, Tada MT, Lima IR, Silva IFO, Pereira AC, et al. Cascade Screening and Genetic Diagnosis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia in Clusters of the Southeastern Region from Brazil. 10.1007/s11033-020-06014-0.Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(12):9279–9288. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-06014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. 10.1038/gim.2015.30.Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]