Abstract

Background:

Trichohepatoenteric syndrome (THES) is a very rare disorder that is characterized by intractable congenital diarrhea, woolly hair, intrauterine growth restriction, facial dysmorphism, and short stature. Our knowledge of THES is limited due to the small number of reported cases.

Methods:

Thirty patients diagnosed with THES, all molecularly confirmed by whole exome sequencing (WES) to have biallelic variants in TTC37 or SKIV2L, were included in the study. Clinical, biochemical, and nutritional phenotypes and outcome data were collected from all participants.

Results:

The median age of THES patients was 3.7 years (0.9–23 years). Diarrhea and malnutrition were the most common clinical features (100%). Other common features included hair abnormalities (96%), skin hyperpigmentation (87%), facial dysmorphic abnormalities (73%), psychomotor retardation (57%), and hepatic abnormalities (30%). Twenty-five patients required parenteral nutrition (83%) with a mean duration of 13.34 months, and nearly half were eventually weaned off. Parenteral nutrition was associated with a poor prognosis. The vast majority of cases (89.6%) had biallelic variants in SKIV2L, with biallelic variants in TTC37 accounting for the remaining cases. A total of seven variants were identified in TTC37 (n = 3) and SKIV2L (n = 4). The underlying genotype influenced some phenotypic aspects, especially liver involvement, which was more common in TTC37-related THES.

Conclusion:

Our data helps define the natural history of THES and provide clinical management guidelines.

Keywords: Consanguinity, founder, intestinal failure, intractable diarrhea, malnutrition, parental nutrition, syndromic diarrhea

INTRODUCTION

Syndromic diarrhea (SD) was first described by Stankler in 1982,[1] who reported two cases with intractable diarrhea, dysmorphic features, and hair abnormalities. Subsequently, Giraulat reported eight cases with similar clinical features and evidence of immunodeficiency.[2] Additional cases associated with neonatal hemochromatosis were also reported, and SD was eventually renamed to Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome or THES.[3,4,5]

THES is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by pathogenic variants in two genes: (1) the tetratricopeptide repeat domain–containing protein 37 gene (TTC37) (MIM 614589) and (2) SKI2-Like RNA Helicase (SKIV2L) (MIM 600478).[6] The two genes encode the cofactors of the human SKI complex involved in RNA degradation.[7] Hartley sequenced TTC37 in 12 patients and identified homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for deleterious variants.[8] Fabre also analyzed TTC37 in nine patients with THES and identified 11 novel variants.[9] In 2012, Fabre identified SKIV2L as the second gene for this condition based on unrelated patients with biallelic deleterious variants in this gene.[10]

THES is a multisystem disorder incorporated in congenital diarrheal diseases known as enterocyte epithelial alteration disorders, such as tufting enteropathy and microvillus inclusion disease. THES is classified into type 1 (TTC37-related, OMIM#222470) and type 2 (SKIV2L-related, OMIM#614602).[6,11] THES features include intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) or small for gestational age, congenital intractable diarrhea, abnormal hair (uncombable, brittle, with features of trichorrhexis nodosa), facial dysmorphism, skin hyperpigmentation, chronic liver disease with cirrhosis in severe cases, and immunodeficiency (recurrent infection, hypogammaglobulinemia, lack of antibody response to vaccines, and/or increased immunoglobulin A and/or T-cell production).[11,12,13,14] Less common features include congenital heart disease and abnormal platelets.[13]

The primary management currently involves parenteral nutrition, enteral feeding, and supportive management for other involved organs. In some cases, cortico steroids, immunosuppressant medications, and immunoglobulin are also used.[14,15]

The variability of clinical features, lack of familiarity due to extreme rarity, clinical management difficulty, and uncertainty of prognosis are challenging aspects of THES management. Only 58 cases have been reported worldwide (France, Italy, Australia, India, Japan, and South Africa) including 6 cases from Saudi Arabia.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] Reported cases reveal a wide range of clinical phenotypes and management strategies with some patients achieving long-term survival after being removed from parental nutrition and others succumbing to the disease in early infancy despite intensive management.[14,16,21]

In this study, we report a much more comprehensive cohort based on a multicenter study on the clinical presentation, management, and long-term outcomes in molecularly confirmed THES patients in Saudi Arabia, that were genetically confirmed with the disease between 2003 and 2019.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study comprises multicenter retrospective chart reviews, whereby we invited all pediatric gastroenterologists in Saudi Arabia to enroll their patients of the country with THES. The diagnosis must have been confirmed by identifying biallelic pathogenic variants in TTC37 or SKIV2L. Responding gastroenterologists and their eight tertiary hospitals covered all major regions in Saudi Arabia, including their enrolled patients who were diagnosed between 2003 and 2019.

We collected data related to demographics, clinical features, presence of diarrhea, dysmorphic features, growth parameters, skin pigmentations, laboratory investigations (liver enzymes and immunoglobulins level), abdominal ultrasound results, parenteral nutrition duration, and outcome data.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed for all THES patients enrolled in this study. In all patients, excluding three (see below), biallelic variants were identified in TTC37 or SKIV2L. In these three patients (P17, P23, and P24), clinical WES was reported negative; however, the underlying causal variant was subsequently identified in one of the two genes by reanalysis as described in a study by Maddirevula et al.[22]

This study was approved by the Institution Research Board of King Fahad Medical City (Ethics Policy 19-511). Parental consent was obtained to publish clinical photographs in this article.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS. Epidemiologic data and results were expressed as means, ranks, percentages, and Chi-square test.

RESULTS

Thirty-five genetically confirmed THES patients (27 families) were referred to us, and five cases were excluded due to insufficient clinical data. Of the remaining 30 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 24 patients were newly diagnosed, and 6 patients had been previously reported.[12] Most cases (22/30) were diagnosed over the last 10 years (2009–2019). The annual number of live births in Saudi Arabia according to the General Authority for Statistics, Demographic Survey 2016 is 432,000 (https://www.stats.gov. sa/en/). Accordingly, we estimate the minimal incidence of THES in Saudi Arabia to be 1 per 196,364 live births.

WES showed that all patients were homozygous for the causal variants in TTC37 or SKIV2L, except P7 who was compound heterozygous in SKIV2L. Twenty-six patients had variants in SKIV2L (four unique variants) and only three patients in TTC37 (three unique variants) as shown in Table 1. The carrier frequency of the founder variant in SKIV2L was 0.0003743, so we could estimate the minimum disease burden based on the the carrier frequency (CF) for variant X. CF was calculated as CF(X)= qF based on the method described previously[23] in which q is the probability of the mutant allele and F is the average inbreeding coefficient in our population (0.0241) as 1 per 221,714.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical and molecular findings in the study cohort

| Patient Number | Gender | Age | Facial Dysmorphism | Hair abnormality | Skin pigmentation | Chronic liver disease | Alive/Dead | TPN duration (months) | Variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | 1.5 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Dead | 5 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P2 | F | 1.25 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | Still | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 1297C>T (p.Arg433Cys). |

| P3 | F | 1.33 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Alive | 0 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 1201G>A (p.Glu401Lys). |

| P4 | F | 4 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Alive | 0 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P5 | M | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 3 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P6 | F | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Dead | 24 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P7 | M | 1.67 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 16 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:[c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del)];[c. 2479C>T (p.Arg827*)] |

| P8 | F | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 2 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P9 | F | 0.9 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 6 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P10 | F | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 40 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 2479C>T (p.Arg827Ter). |

| P11 | M | 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alive | 32 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P12 | M | 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | Still | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P13 | F | 1.67 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dead | 20 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P14 | M | 2.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Dead | 24 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P15 | M | 7 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Alive | 12 | TTC37:NM_014639.4:c. 4175_4176dupCA (p.Val1393GlnfsTer24) |

| P16 | F | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alive | 12 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P17 | M | 1.67 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Dead | 16 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P18 | M | 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dead | 22 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P19 | F | 11 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 0 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P20 | F | 1.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alive | Still | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P21 | F | 2.42 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 0 | TTC37: NM_014639.4:c. 2181_2182delGT (p.Tyr728CysfsTer6) |

| P22 | M | 12.5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 12 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P23 | M | 3.5 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | Still | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P24 | F | 3.25 | No | Yes | No | No | Alive | 0 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P25 | F | 23 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alive | 4 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P26 | M | 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Alive | 24 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P27 | F | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | 7 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P28 | F | 12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Alive | still | TTC37: NM_014639.4:c. 4102C>T (p.Gln1368Ter) |

| P29 | M | 12 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Alive | 7.5 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

| P30 | F | 11 | Yes | NA | Yes | No | Alive | 12 | SKIV2L: NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del). |

Demographic characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Seventeen (57%) females and 13 (43%) males were included in our group. The gestational age was term except for two patients born at 36 weeks and none had a history of polyhydramnios. IUGR was observed in 22 (66.7%) patients, and all but two had a birth weight of ≤3 kg (mean birth weight 2.3 kg and the median 2.2 kg). The median age of the patients was 3.75 years (0.9–23 years old). All but two of the 27 families were consanguineous.

Table 2.

Frequency of clinical features all patients (n=30)

| Clinical features | No. of positive patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 30/30 (100) |

| FTT on first presentation | 30/30 (100) |

| Hair abnormality | 28/29 (96) |

| Low birth weight/small for gestational age | 20/30 (66.7) |

| Skin pigmentations | 26/30 (86.7) |

| Dysmorphic features | 22/30 (73) |

| Peg Teeth | 5/28 (18) |

| Term Baby | 28/30 (93) |

| Psycho motor retardation | 16/28 (57) |

| Chronic liver disease | 9/30 (30) |

| Immunodeficiency/low IgG | 5/24 (21) |

| Congenital heart disease | 1/30 (3.3) |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (6.7) |

All patients presented with diarrhea albeit of variable severity. Some patients had very mild diarrhea. The mean age at onset of diarrhea was 28.6 days, and the median was 14 days. One patient presented with late-onset diarrhea at 6 months. Twenty-six patients (86.7%) had skin hyperpigmentation (café au lait macules) mainly over the lower limbs and pelvis, and two patients had hypopigmentation. Hair abnormalities (n = 28, 96%) included woolly, hypopigmented, brittle, uncombable, or positive for trichorrhexis nodosa. Dysmorphic facial features were seen in 22 patients (73%). The dysmorphic features of our cohort patients were hypertelorism, broad nose bridge, depressed nose bridge, prominent and broad forehead, low set ears, prominent checks, and largemouth, which were similar to those reported before [Figure 1]. Surprisingly, chronic liver disease, as shown by high liver enzymes or evidence of cirrhosis, was only seen in nine patients (30%), and one case improved after being successfully weaned off parenteral nutrition. One case developed hepatocellular carcinoma. Sixteen patients (57%) had psychomotor delays. The only evidence of immunodeficiency was hypogammaglobulinemia in five patients who received immunoglobulin supplementation [Table 2]. None of our patients tested for platelet disorders, while three were tested for B-cell function and were normally found. Sixteen patients were examined for T-cell defect, which was normal; however, the CD8 number was non-significantly low for six patients (37.5%), and one patient had a non-significant increase in CD8-T cell (6.25%).

Figure 1.

A patient with skin hyperpigmentation (café au lait macules) over the lower limbs, woolly, brittle hair and dysmorphic facial features

Two out of nineteen patients (10.5%) had feeding disorders, and one patient had a gastrostomy tube. Different formulas and diets were tried (lactose-free, extensively hydrolyzed, amino acids base, fructose base, medium-chain base, and diet for age), but none had a significant response. However, most of them were on a diet for age and amino acid formula.

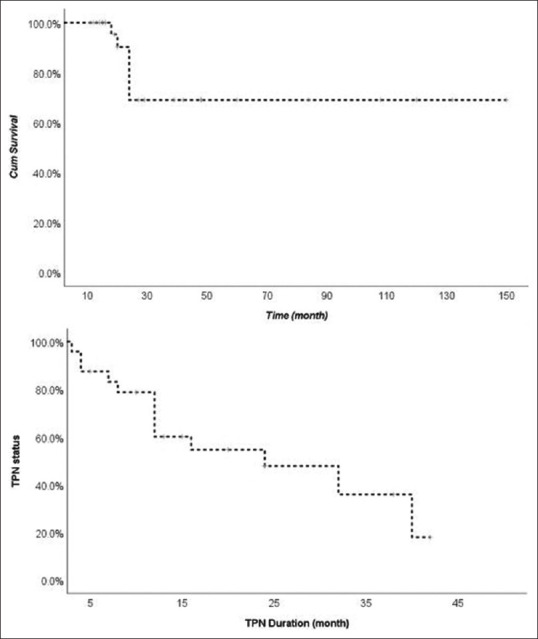

Parenteral nutrition and outcome details are shown in Table 3. Twenty-five patients (83%) received parenteral nutrition. Nearly half of the parenteral nutrition group (n = 14, 56%) were successfully weaned off parenteral nutrition over a mean duration of 13.34 months, whereas five patients remained dependent on parental nutrition for a median duration of 3.5 years (one patient remained dependent for 12 years). There were no significant differences between several clinical presentations and outcome results between patients who received and did not receive parenteral nutrition [Table 4]. Twenty-four patients remain alive at the time of recruitment accounting for an overall survival of 80%. The oldest is now 23 years of age, while six patients passed away at a mean age of 1.7 years. Three of the deceased died due to sepsis, whereas the other three died secondary to postbowel transplant, hepatoblastoma, or liver cirrhosis [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and outcomes global (n=30)

| Items | No. of positive patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Alive | 24/30 (80) |

| Died | 6/30 (20) |

| Not received TPN at all and still alive | 5/30 (17) |

| Received TPN | 25/30 (83) |

| Off TPN | 14/25 (56) |

| Patient still on TPN | 5/25 (20) |

| Died (received TPN) | 6/25 (24) |

Table 4.

Clinical features and outcome difference between the patients who received and did not receive TPN

| Patients receiving TPN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | No (n=5) | Yes (n=25) | Total | P | |

| Birth weight (Kg) | Mean±SD | 2.3±0.3 | 2.3±0.6 | 2.3±0.5 | 0.965 |

| Median (min - max) | 2.3 (2 - 2.7) | 2.2 (1.3 - 3.9) | 2.2 (1.3 - 3.9) | ||

| Age (month) | Mean±SD | 53±46 | 39±38 | 41±39 | 0.47 |

| Median (min - max) | 39 (16 - 132) | 24 (11 - 150) | 24 (11 - 150) | ||

| Onset of diarrhea (Days) | Mean±SD | 26±38 | 29±35 | 29±35 | 0.858 |

| Median (min - max) | 8 (1 - 90) | 14 (2 - 180) | 14 (1 - 180) | ||

| Last Weight | Mean±SD | 10.7±2.1 | 10.6±4.3 | 10.6±3.8 | 0.971 |

| Median (min - max) | 10.8 (8.6 - 12.7) | 8.4 (5.6 - 19.4) | 9.4 (5.6 - 19.4) | ||

| Last Height | Mean±SD | 87.8±5.8 | 83.4±16.6 | 84.4±14.9 | 0.666 |

| Median (min - max) | 88 (82 - 93.5) | 80 (64 - 116) | 84 (64 - 116) | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase | Mean±SD | 39±25 | 39±38 | 39±35 | 0.978 |

| Median (min - max) | 30 (22 - 83) | 20 (12 - 151) | 25 (12 - 151) | ||

| Aspartate transaminase | Mean±SD | 37±26 | 43±26 | 42±26 | 0.659 |

| Median (min - max) | 30 (17 - 72) | 42 (14 - 129) | 40 (14 - 129) | ||

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase | Mean±SD | 91.5±154.7 | 57.1±80.7 | 63.4±94.2 | 0.522 |

| Median (min - max) | 18.5 (6 - 323) | 15.5 (1 - 315) | 15.5 (1 - 323) | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | Mean±SD | 190±46 | 300±233 | 270±204 | 0.318 |

| Median (min - max) | 209 (130 - 231) | 220 (116 - 847) | 216 (116 - 847) | ||

| Total Bilirubin | Mean±SD | 3.9±1.7 | 24.5±58.4 | 19.1±50.5 | 0.449 |

| Median (min - max) | 3.9 (2.3 - 6.4) | 5.2 (2.6 - 220.9) | 4.8 (2.3 - 220.9) | ||

| Direct Bilirubin | Mean±SD | 1.35±1.17 | 21.1±51.25 | 16.16±44.77 | 0.464 |

| Median (min - max) | 1.15 (0.3 - 2.8) | 2.25 (0.4 - 176.39) | 1.9 (0.3 - 176.39) | ||

| International normalized ratio | Mean±SD | 1.07±0.06 | 1.25±0.23 | 1.22±0.22 | 0.203 |

| Median (min - max) | 1.1 (1 - 1.1) | 1.2 (0.87 - 1.7) | 1.17 (0.87 - 1.7) | ||

| Albumin on First time | Mean±SD | 37±9 | 36±6 | 36±7 | 0.776 |

| Median (min - max) | 40 (27 - 45) | 37 (28 - 43) | 39 (27 - 45) | ||

| Albumin (Last one) | Mean±SD | 36.7±2.7 | 32.7±9.4 | 33.7±8.3 | 0.365 |

| Median (min - max) | 36.1 (33.5 - 41) | 37 (17 - 46) | 37 (17 - 46) | ||

| white blood cells | Mean±SD | 9.5±2.86 | 14.07±5.07 | 12.73±4.93 | 0.081 |

| Median (min - max) | 9.1 (6.1 - 12.71) | 14.93 (5.6 - 23.6) | 12.71 (5.6 - 23.6) | ||

| Hemoglobin | Mean±SD | 11.9±0.8 | 10.9±1.8 | 11.2±1.6 | 0.243 |

| Median (min - max) | 12.1 (11 - 13) | 11.1 (7 - 13.7) | 11.6 (7 - 13.7) | ||

| Platelet | Mean±SD | 430±93 | 394±174 | 403±157 | 0.701 |

| Median (min - max) | 441 (326 - 513) | 379 (138 - 760) | 379 (138 - 760) | ||

Figure 2.

Survival by year and age in years by parenteral weaning

Malnutrition was common in our group; 16/24 patients (67%) were less than - 2 SD for weight, (mean - 3.5 SD, and the median - 2.84 SD). A similar trend was observed for stature with 11/24 patients (46%) being less than - 2 SD (mean - 2.28 SD, median - 1.78 SD). All five patients who remained dependent on parenteral nutrition were short and malnourished [Table 5]. There was no significant difference in growth parameters regardless of parenteral nutrition status (P values were 0.72 and 0.77 for weight and height, respectively).

Table 5.

Nutrition status of the study participants*

| Patient Number | Age (year) | Sex | Weight | Z score Weight | Height/Length | Z score Height/Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 1.5 | M | 5.1 | −8.18 | 57 | −9.05 |

| P2 | 1.25 | f | 5.6 | −6.4 | 65 | −3.85 |

| P3 | 1.33 | F | 8.6 | −2.03 | 82 | 1.21 |

| P4 | 4 | F | 12.7 | −1.89 | 93.5 | −1.11 |

| P5 | 9 | M | 19.4 | −3.05 | 116 | −0.86 |

| P6 | 2 | F | 8.4 | −3.85 | 80 | −1.65 |

| P7 | 1.67 | m | 8.3 | −3.44 | 87 | 0.95 |

| P8 | 1 | F | 7.8 | −1.88 | 70.5 | −1.12 |

| P9 | 0.9 | F | 7.7 | −1.66 | 64 | −2.90 |

| P10 | 4 | f | 13 | −1.59 | 97 | −1.54 |

| P11 | 5 | m | 16 | −1.15 | 104 | −1.05 |

| P12 | 4 | m | 10.2 | −4.83 | 86 | −2.68 |

| P13 | 1.67 | f | 7.14 | −5.06 | 73 | −2.75 |

| P14 | 2.1 | m | 13.1 | 0.21 | 75 | −3.68 |

| P15 | 7 | M | 17 | −2.52 | 107 | −0.52 |

| P16 | 10 | F | 18 | −4.03 | 115 | −1.46 |

| P17 | 1.67 | M | 7.8 | −4.17 | 81 | −0.85 |

| P18 | 2 | M | 5.8 | −7.17 | 60 | −6.44 |

| P19 | 11 | F | 26.3 | −1.98 | 128 | −2.23 |

| P20 | 1.1 | F | 3.4 | −11.02 | 58 | −5.4 |

| P21 | 2.42 | F | 9.8 | −2.72 | 81 | −1.61 |

| P22 | 12.5 | M | 26.5 | −2.96 | 135 | −2.28 |

| P23 | 3.5 | M | 13.5 | −1.10 | 99 | −1.90 |

| P24 | 3.25 | f | 10.8 | −2.70 | 88 | −2.06 |

*Patients 25-30 are previously published

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive series of THES from the Middle East. Fabre et al. reviewed THES[9,11] and concluded that the incidence was 1 in 1,000,000 in France based on the 15 patients born in France over 20 years. We estimate a much higher incidence of THES in Saudi Arabia of around 1:200,000 births, which can be explained by the high rate of consanguineous marriages in Saudi Arabia, as this is an autosomal recessive disease. Indeed, 10 out of 15 patients in the case series reported by Fabre[11] were originally from the MENA Maghreb and Middle East region in which consanguinity is common. Taking advantage of the founder nature of one common SKIV2L variant (NM_006929.5:c. 3561_3581del (p.Ser1189_Leu1195del)), we corroborated the higher THES incidence in Saudi Arabia. Even this variant-driven figure is undoubtedly an underestimation because it does not take into account all the other private variants that have no carrier frequency in the population, and this particular variant is very challenging to detect. We know several cases that tested “negative“ on WES only to be found by Sanger sequencing to have this variant, which means that the carrier frequency is underestimated. We should point here that the skewed ratio of type 1 to type 2 THES, compared to previous cohorts, is most likely related to this common founder in SKIV2L. For comparison, Fabre and Bourgeois reported 40 TTC37 versus 14 SKIV2L and 38 versus 21, respectively.[15,16]

Our patients’ primary clinical features [Figure 1] are similar to those reported in the literature: (1) intractable diarrhea albeit of variable severity, (2) dysmorphic features, and (3) intrauterine growth failure/small birth weight were high in frequency as seen in other reported patients.[9,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] However, the skin abnormalities, mainly the hyperpigmented macules that preferentially appear on the lower limbs, were very common in our cohort (86.7%) in contrast to the reports by Fabre[16] and Bourgeois[15] of 50% and 51%, respectively. We hypothesize that a Saudi infant with intractable diarrhea, small birth weight, and hyperpigmented macules most likely has THES syndrome until proven otherwise.

Chronic liver disease was found in nine patients (30%) and 30.7% of those with SKIV2L mutation in our cohort, which is low compared to 70% and 85% in the Fabre and Bourgeois groups, respectively[15,16] and 88% in the SKIV2L-related THES.[15] Liver disease was a direct cause of death in a single patient in our group compared to 40% of patients with liver disease in the literature.[2,3] One patient developed hepatocellular carcinoma, and we note that a hepatoblastoma case was previously reported by Bozzette.[24] Our data suggests that chronic liver disease is not more prevalent in patients with the SKIV2L mutation than in those with TTC37, and that SKIV2L- and TTC37-related THES are indistinguishable clinically, although we caution that the very small number of TTC37-related patients in our cohort is a study limitation. Other than five patients with hypogammaglobulinemia who received immunoglobulin supplementation, there were no apparent immunological abnormalities noted in our patients. Our study is retrospective and we consider an immune workup for such patients, especially T-cell defects.[17]

The incidence of parental nutrition in our cohort (83%) is similar to the Bourgeois et al. group (85%).[15] Five patients in our cohort did not require parenteral nutrition and are still surviving, compared to only nine patients worldwide reported to have had no parenteral nutrition.[14,21] About half of our patients achieved enteric autonomic control, and parenteral nutrition was weaned off, in contrast to 30%–50% in other studies.[14] Unfortunately, most of our patients exhibited malnutrition (66.7%) and many (45.8%) had short stature regardless of parenteral nutrition use. Barabino et al. reported two patients who were severely malnourished after stopping parenteral nutrition.[21] It seems that parenteral nutrition does not improve growth and may actually worsen the prognosis for some patients. Our data emphasizes the importance of reviewing the necessity of parenteral nutrition on a case-by-case basis. We suggest that parenteral nutrition is unnecessary if the patient does not have severe diarrhea and/or electrolyte imbalance.

In conclusion, we report a large cohort with detailed clinical delineation of THES, which we show is more common in Saudi Arabia. We define the natural history of the disease and stress that parenteral nutrition should only be used judiciously to minimize the adverse outcome in THES patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Fowzan S Alkuraya, Department of Genetics, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh for his helpful comments and edits while preparing this manuscript. Also we would like to thank Mr. Tariq Ahmad Wani, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Second Health Cluster, for his help in biostatistics analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stankler L, Lloyd D, Pollitt RJ, Gray ES, Thom H, Russell G. Unexplained diarrhoea and failure to thrive in 2 siblings with unusual facies and abnormal scalp hair shafts: A new syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:212–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.57.3.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girault D, Goulet O, Le Deist F, Brousse N, Colomb V, Césarini JP, et al. Intractable infant diarrhea associated with phenotypic abnormalities and immunodeficiency. J Pediatr. 1994;125:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verloes A, Lombet J, Lambert Y, Hubert AF, Deprez M, Fridman V, et al. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: Further delineation of a distinct syndrome with neonatal hemochromatosis phenotype, intractable diarrhea, and hair anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1997;68:391–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970211)68:4<391::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dweikat I, Sultan M, Maraqa N, Hindi T, Abu-Rmeileh S, Abu-Libdeh B. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: A case of hemochromatosis with intractable diarrhea, dysmorphic features, and hair abnormality. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:581–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabre A, André N, Breton A, Broué P, Badens C, Roquelaure B. Intractable diarrhea with “phenotypic anomalies“ and tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: Two names for the same disorder. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:584–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabre A, Martinez-Vinson C, Goulet O, Badens C. Syndromic diarrhea/Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabre A, Badens C. Human Mendelian diseases related to abnormalities of the RNA exosome or its cofactors. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3:8–11. doi: 10.5582/irdr.3.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, Donowitz M, Forman J, Pollitt RJ, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy) Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2388-98):2398.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabre A, Martinez-Vinson C, Roquelaure B, Missirian C, André N, Breton A, et al. Novel mutations in TTC37 associated with tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:277–81. doi: 10.1002/humu.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabre A, Charroux B, Martinez-Vinson C, Roquelaure B, Odul E, Sayar E, et al. SKIV2L mutations cause syndromic diarrhea, or trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:689–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabre A, Breton A, Coste ME, Colomb V, Dubern B, Lachaux A, et al. Syndromic (phenotypic) diarrhoea of infancy/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:35–8. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monies DM, Rahbeeni Z, Abouelhoda M, Naim EA, Al-Younes B, Meyer BF, et al. Expanding phenotypic and allelic heterogeneity of tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:352–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee WI, Huang JL, Chen CC, Lin JL, Wu RC, Jaing TH, et al. Identifying mutations of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37 (TTC37) gene in infants with intractable diarrhea and a comparison of Asian and Non-Asian phenotype and genotype: A global case-report study of a well-defined syndrome with immunodeficiency. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2918. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabre A, Bourgeois P, Coste ME, Roman C, Barlogis V, Badens C. Management of syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: A review of the literature. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2017;6:152–7. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2017.01040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourgeois P, Esteve C, Chaix C, Béroud C, Lévy N, et al. THES clinical consortium. Tricho-Hepato-Enteric syndrome mutation update: Mutations spectrum of TTC37 and SKIV2L, clinical analysis and future prospects. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:774–89. doi: 10.1002/humu.23418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fabre A, Bourgeois P, Chaix C, Bertaux K, Goulet O, Badens C. GeneReviews® [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 11]. Trichohepatoenteric Syndrome. 1993-2021. https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vély F, Barlogis V, Marinier E, Coste ME, Dubern B, Dugelay E, et al. Combined immunodeficiency in patients with trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1036. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinnear C, Glanzmann B, Banda E, Schlechter N, Durrheim G, Neethling A, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a novel TTC37 mutation in the first reported case of Trichohepatoenteric syndrome (THE-S) in South Africa. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18:26. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0388-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiejima E, Yasumi T, Nakase H, Matsuura M, Honzawa Y, Higuchi H, et al. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome with novel SKIV2L gene mutations: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8601. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poulton C, Pathak G, Mina K, Lassman T, Azmanov DN, McCormack E, et al. Tricho-hepatic-enteric syndrome (THES) without intractable diarrhoea. Gene. 2019;699:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barabino AV, Torrente F, Castellano E, Erba D, Calvi A, Gandullia P. “Syndromic diarrhea“ may have better outcome than previously reported. J Pediatr. 2004;144:553–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maddirevula S, Kuwahara H, Ewida N, Shamseldin HE, Patel N, Alzahrani F, et al. Analysis of transcript-deleterious variants in Mendelian disorders: Implications for RNA-based diagnostics. Genome Biol. 2020;21:145. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abouelhoda M, Sobahy T, El-Kalioby M, Patel N, Shamseldin H, Monies D, et al. Clinical genomics can facilitate countrywide estimation of autosomal recessive disease burden. Genet Med. 2016;18:1244–9. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozzetti V, Bovo G, Vanzati A, Roggero P, Tagliabue PE. A new genetic mutation in a patient with syndromic diarrhea and hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:e15. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825600c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]