The burnout epidemic in healthcare is often in the limelight, and that focus is warranted. This phenomenon of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a missing sense of personal accomplishment [1] plagues roughly 34% [9] of surgeons and 56% [20] of residents in orthopaedics alone. Financial costs related to burnout across specialties are estimated at USD 4.6 billion annually [6], while further intangible costs are incurred from providers suffering decreased cognitive function, leaving practice, and even attempting suicide [4].

Burnout is often framed as a chronic stress response, yet interventions intended to bolster individual resilience have had little meaningful impact on the proportion of physicians experiencing burnout [14]. We believe burnout should be reframed as a moral injury, defined as the damage done to one’s conscience by a transgression of moral values. Physicians experience this constantly due to the systematic misalignment of their work, which is primarily focused on tasks more financially driven than relevant to healing patients.

In addition to moral injury, these extrinsically motivated tasks deprive physicians of their inherent enjoyment of treating patients [7]. Framing burnout as moral injury explains the ineffectiveness of resilience training initiatives and is supported by evidence that working conditions and misalignment of work with purpose are the true root causes of the burnout epidemic [1].

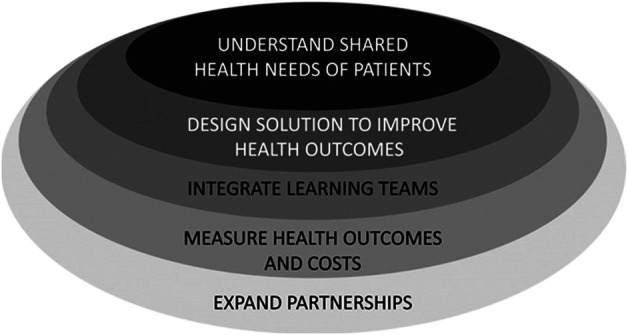

The nature and scope of the burnout problem in orthopaedics, therefore, requires system-level solutions that facilitate relationship-centered care and maximize physicians’ intrinsic motivation to heal. Our approach to combat burnout is to align clinical work and experience with patient goals using value-based healthcare principles (Table 1). Each principle builds on and informs the previous, creating a cyclical implementation strategy (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Five value-based healthcare principles that can disrupt the root causes of burnout, with goals, tips, and recommendations for additional resources

| Understand the Shared Health Needs of Patients |

| Goal: Understand patients’ needs, goals, and challenges through research with both patients and clinicians. Next, define services based on the shared needs of patients rather than on provider specialty. |

| Implementation tip: Utilize observation and interview techniques to identify shared patient needs and process mapping to identify opportunities to implement value-based healthcare principles. |

| Recommended resource: Harvard Business School provides an approach to process mapping [11]. |

| Design a Comprehensive Solution to Improve Health Outcomes |

| Goal: Broaden the services and solutions offered in a single, streamlined clinic to address not just traditional orthopaedic needs but also common psychosocial obstacles undermining health outcomes. |

| Implementation tip: Invest in finding and implementing psychosocially informed solutions that are both realistic and effective, ideally with on-site resources but potentially through online subscriptions or publicly available services. |

| Recommended resources: The National Alliance on Mental Illness [12] and National Institute for Mental Health provide a variety of resources [13]. |

| Integrate Learning Teams |

| Goal: Recruit multidisciplinary clinical teams to provide flexible, whole-person care in a shared location (possibly virtual) and create a culture of constant communication to facilitate interdisciplinary learning. |

| Implementation tip: Schedule preclinic, multidisciplinary “huddles” to quickly review the patients for the day and align on likely services needed, as well as postclinic “huddles” to make sure all outstanding questions or administrative tasks are addressed. |

| Recommended resource: Those interested in adding multidisciplinary “huddles” to their workflow can witness a huddle in action at the UTHA Immersion Program in Value-Based Health Care [19]. |

| Measure Health Outcomes and Costs |

|

Goal: Measure outcomes that matter to patients so that teams can align around the purpose of helping patients. This can help improve appropriateness, efficacy, and respectfulness of care. Implementation tip: Start with low-tech printouts of publicly available patient reported outcome measures and potentially engage pre-med or medical students to keep track of the resulting data. |

| Recommended resource: A list of condition-specific, vetted PROs can be found through the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement [8]. |

| Expand Partnerships |

|

Goal: Increase the reach of value-based care specialty practices by partnering with local primary care physicians, employers, referral sources, and related clinical practices. Implementation tip: Reach out directly to local providers to establish basic guidelines on appropriate imaging when referring patients, for example. |

| Recommended resource: A comprehensive overview of care coordination research and evaluation measures was compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [2]. |

Fig. 1.

The five-step implementation strategy to combat burnout aligns clinical work and experience with patient goals using value-based healthcare principles.

Implementing these strategies requires time, energy, and sometimes substantial resources. Accepting our approach requires acknowledging the increased regulatory oversight meant to counteract rising healthcare costs (CMS programs like the Quality Payment Program, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, and the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement [CJR] model, for example [16]). Orthopaedics finds itself at the forefront of these changes and can lead healthcare transformation. We see combatting burnout as one component of the larger argument for making the transition to a value-based healthcare model [15] that supports patients and physicians and could potentially reduce healthcare spending.

Understand the Shared Health Needs of Patients

Understanding and prioritizing patient preferences and goals is our foundational principle. Practice leaders should align their strategic decisions with clinician and patient priorities in mind rather than structuring their decisions around clinical expertise, as is traditionally done in healthcare. Relying solely on clinical expertise, or not prioritizing how patients coordinate their care, can lead to fragmentation, which negatively impacts the effectiveness, safety, and efficiency of the entire healthcare system [2]. Moreover, it confuses patients and fosters a sense of loss of control for clinicians. Referrals received are inconsistent or even inappropriate, follow-up is often lacking, and resources are wasted on duplicative testing, all of which exacerbates administrative burden and burnout.

To improve care coordination for patients and clinicians, clinics must first define (in granular detail) their patients’ needs. This requires working directly with patients to understand the outcomes and obstacles that matter to them, as well as utilizing “process mapping,” a structural engineering technique, to identify pain points and opportunities for process improvement. The sections below will explore how to address certain patient needs.

Design a Comprehensive Program to Improve Health Outcomes

This strategy is obvious on the surface: for each patient need, clinics should offer a patient-centered service that aligns patient and clinical team goals. Alleviating pain and improving function, for instance, often requires a multimodal approach involving expertise and input from a variety of different disciplines. Despite the success of traditional orthopaedic treatments, as measured by clinician-defined indicators like complication rates, a growing body of evidence indicates that self-reported capability and comfort among orthopaedic patients vary widely—and the variation is largely explained by psychosocial factors [21]. Furthermore, studies show that baseline anxiety and depression are predictive of poor postoperative patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [5]. Ignoring psychosocial issues not only affects orthopaedic outcomes but can contribute to burnout among clinicians who feel helpless in the face of systemic barriers to impacting health outcomes.

Still, most orthopaedic surgeons lack the time and expertise to address the multitude of psychosocial challenges patients face in our country—depression should not be treated with arthroplasty. Indeed, comprehensive, whole-person care requires looking beyond a traditional orthopaedic team. Admittedly, this is easier said than done. But when implemented effectively, multidisciplinary teams can achieve greater improvement in health outcomes at lower costs because the focus shifts from volume to appropriateness of care. Wasteful time and resources are minimized, thus driving down overall costs of care and making value-based transformation an achievable and equitable goal for even resource-limited practices.

Transitioning to a fully multidisciplinary team does take time, so practices may consider intermediary steps like fostering close relationships with local mental and behavioral health providers, subscribing to online services, connecting patients to publicly available resources by providing internet access via clinic-owned tablets, or even just handing out simple printed lists of mental health providers in the area.

Finding effective and realistic solutions may require upfront time, creativity, and funding, but we believe these solutions are worth the investment in terms of both patient and clinician well-being. Patients feel seen and achieve better functional outcomes, which practices can leverage to drive additional patient volume. Clinicians save time and emotional energy by having specific, preidentified resources to help reduce burnout-related costs.

Integrate Learning Teams

Delivering comprehensive solutions requires a highly coordinated, multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals. We call these “learning teams” because teammates enrich and improve their own practices through exposure to clinicians with different expertise. Such teams are the centerpiece of implementing value-based care to combat burnout, particularly if teams are colocated. Sharing patients and space facilitates informal information sharing, which improves care coordination and reduces the administrative burden of referrals. Cross-disciplinary teaching is intellectually engaging, but also flattens toxic hierarchical structures by placing value on all members of the healthcare team. Importantly, this approach promotes a positive workplace culture by aligning clinicians around shared patients and care delivery goals. These benefits can potentially combat burnout across care team members, and the positive culture can help recruitment and retention in the difficult staffing environment that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Space and budget constraints are understandably significant limitations, but do not preclude at least partial implementation of this strategy. Creative online solutions such as video conferencing, shared live documents, or ongoing chats can mimic shared physical space if used effectively. The business case for new team members is based on improving patient outcomes through physical, psychosocial, nutritional, and other support, as well as on freeing surgeon time to spend on high-margin activities by having all members of the team operate at the top of their licenses. Just as it makes no sense to have surgeons manage scheduling and billing, it makes little sense to rely on orthopaedists to provide psychosocial support. Each step taken toward relationship-centered, coordinated care is also a step toward alleviating moral injury by improving patient outcomes and increasing the appropriateness of resource utilization.

Measure Health Outcomes and Costs

Defining and measuring the success of the solutions described above is critical to achieving high-value care. Yet, traditional measures of success, dictated by reimbursement or quality improvement requirements, often have little relevance to patients’ lived experiences. Complications and mortality, for instance, give little insight into whether a patient’s musculoskeletal health has improved because of the care we provide. Moreover, framing clinical activities in terms of reimbursement plays into extrinsic motivators for physicians and inhibits their ability to derive fulfillment from practicing medicine [7].

The ultimate goal of value-based healthcare in orthopaedics is to shift incentive structures from an economic focus to a health outcomes focus using PROs [17]. Measuring improvement in capability (functional levels), comfort (reduction in physical or mental suffering), and calm (less disruption from disjointed care or excessive expense) amplifies the patient voice [10, 18]. Data on the “three Cs” [10] also provides actionable feedback about the appropriateness of care and promotes fulfilling intrinsic motivators for clinicians.

While still in its infancy in terms of influencing clinical practice and payment models, PROs are gaining traction. CMS’s CJR model, for instance, includes financial incentives for collection and submission of PROs [3]. In the context of rising healthcare costs, CMS has tested numerous alternative payment models aimed at evaluating clinicians based on quality and cost efficiency. Implementing PROs is therefore not only a tool to combat burnout, but a necessity to keep pace with changing regulations and financial incentives within orthopaedics.

Expand Partnerships

The outermost circle of the implementation strategy focuses on extending value-based principles beyond the walls of a single practice. Establishing relationships and aligning best practices with local referring or comanaging clinicians further enhance care coordination, thus reducing administrative time and improving appropriateness of healthcare utilization. Reaching out directly to local primary care practitioners and agreeing on, for instance, appropriate imaging for specific diagnoses can minimize unpredictability of referrals and inappropriate resource usage.

“Expanding partnerships” can also be thought of as a general guiding principle when implementing value-based healthcare strategies. Our strategies range widely in scale and complexity, but we do not want the most ambitious to overshadow the power of the simplest. Each step taken towards value-based healthcare can potentially reduce burnout. The power of shared goals and close-knit, locally-extended teams cannot be overstated as we seek to save patients, physicians, and dollars alike.

Footnotes

A note from the Editor-in-Chief: We are pleased to present to readers of Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® the latest Value-based Healthcare column. Value-based Healthcare explores strategies to enhance the value of musculoskeletal care by improving health outcomes and reducing the overall cost of care delivery. We welcome reader feedback on all of our columns and articles; please send your comments to eic@clinorthop.org.

One author (KJB) certifies that he, or a member of his immediate family, has received or may receive payments or benefits as a consultant, during the study period, an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Baltimore, MD, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

The opinions expressed are those of the writers, and do not reflect the opinion or policy of CORR® or The Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons®.

Contributor Information

Zoe D. Trutner, Email: zoe.trutner@austin.utexas.edu.

Elizabeth O. Teisberg, Email: teisberg@austin.utexas.edu.

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ research on clinician burnout. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/ahrq-works/impact-burnout.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Care coordination measures atlas update. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/care/coordination/atlas.html. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Comprehensive care for joint replacement model. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/cjr. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 4.Elkbuli A, Sutherland M, Shepherd A, et al. Factors influencing US physician and surgeon suicide rates 2003-2017: analysis of the CDC National Violent Death Reporting System. Ann Surg. Published online November 4, 2020. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal DKC, Stull JD, Divi SN, et al. Combined depression and anxiety influence patient-reported outcomes after lumbar fusion. Int J Spine Surg. 2021;15:234-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:784-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2485-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Our mission. Available at: https://www.ichom.org/mission/. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 9.Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout & suicide report 2020: the generational divide. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#2. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 10.Liu TC, Bozic KJ, Teisberg EO. Person-centered measurement: the three Cs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:315-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClintock TR, Friedlander DF, Feng AY, et al. Determining variable costs in the acute urolithiasis cycle of care through time-driven activity-based costing. Urology. 2021;157:107-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Alliance on Mental Illness. About mental illness. Available at: https://nami.org/About-Mental-Illness. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 13.National Institute for Mental Health. About NIMH. Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 14.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Harvard Business School Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quality Payment Program. Quality payment program overview. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/about/qpp-overview. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 17.Squitieri L, Bozic KJ, Pusic A. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in value-based payment reform. Value Health. 2017;20:834-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teisberg EO, Wallace S, O’Hara S. Defining and implementing value-based health care: a strategic framework. Acad Med. 2020;95:682-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The University of Texas Health. Immersion program in value-based health care. Available at: https://dellmed.utexas.edu/units/department-of-surgery-and-perioperative-care/immersion-program-in-value-based-health-care-musculoskeletal-institute. Accessed March 8, 2022.

- 20.Verret CI, Nguyen J, Verret C, Albert T, Fufa DT. How do areas of work life drive burnout in orthopaedic attending surgeons, fellows, and residents? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:251-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vranceanu AM, Reinier BB, Guitton TG, Janssen SJ, Ring D. How do orthopaedic surgeons address psychological aspects of illness? Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2017;5:2-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]