Abstract

Background and Aims

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for children (aged ≤ 18 years) present methodological challenges. PROMs can be categorised by their diverse underlying conceptual bases, including functional, disability and health (FDH) status; quality of life (QoL); and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Some PROMs are designed to be accompanied by preference weights. PROMs should account for childhood developmental differences by incorporating age-appropriate health/QoL domains, guidance on respondent type(s) and design. This systematic review aims to identify generic multidimensional childhood PROMs and synthesise their characteristics by conceptual basis, target age, measurement considerations, and the preference-based value sets that accompany them.

Methods

The study protocol was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021230833), and reporting followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We conducted systematic database searches for generic multidimensional childhood PROMs covering the period 2012–2020, which we combined with published PROMs identified by an earlier systematic review that covered the period 1992–2011. A second systematic database search identified preference-based value sets for generic multidimensional PROMs. The PROMs were categorised by conceptual basis (FDH status, QoL and HRQoL) and by target age (namely infants and pre-schoolers aged < 5 years, pre-adolescents aged 5–11, adolescents aged 12–18 and multi-age group coverage). Descriptive statistics assessed how PROM characteristics (domain coverage, respondent type and design) varied by conceptual basis and age categories. Involvement of children in PROM development and testing was assessed to understand content validity. Characteristics of value sets available for the childhood generic multidimensional PROMs were identified and compared.

Results

We identified 89 PROMs, including 110 versions: 52 FDH, 29 QoL, 12 HRQoL, nine QoL-FDH and eight HRQoL-FDH measures; 20 targeted infants and pre-schoolers, 29 pre-adolescents, 24 adolescents and 37 for multiple age groups. Domain coverage demonstrated development trajectories from observable FDH aspects in infancy through to personal independence and relationships during adolescence. PROMs targeting younger children relied more on informant report, were shorter and had fewer ordinal scale points. One-third of PROMs were developed following qualitative research or surveys with children or parents for concept elicitation. There were 21 preference-based value sets developed by 19 studies of ten generic multidimensional childhood PROMs: seven were based on adolescents’ stated preferences, seven were from adults from the perspective of or on behalf of the child, and seven were from adults adopting an adult’s perspective. Diverse preference elicitation methods were used to elicit values. Practices with respect to anchoring values on the utility scale also varied considerably. The range and distribution of values reflect these differences, resulting in value sets with notably different properties.

Conclusion

Identification and categorisation of generic multidimensional childhood PROMs and value sets by this review can aid the development, selection and interpretation of appropriate measures for clinical and population research and cost-effectiveness-based decision-making.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40273-021-01128-0.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Our systematic review identified 110 versions of generic multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for children (aged ≤ 18 years) spanning childhood age groups and conceptual bases of functional, disability and health status, quality of life and health-related quality of life. |

| A supplementary systematic review identified 21 preference-based value sets for ten PROMs designed to be accompanied by preference-based value sets. |

| Our catalogues of (1) PROMs categorised by target age group, conceptual bases and related characteristics (domain coverage, respondent type and design) and (2) value sets appraised for their development and statistical features can aid the development, selection and interpretation of appropriate childhood PROMs for clinical and population research and cost-effectiveness-based decision-making. |

Background

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) enable direct assessment of health status, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or quality of life (QoL) by patients or individuals [1–3]. They are used extensively as outcome instruments and can support patient-centred care [2, 4]. The use of PROMs in childhood populations (aged ≤ 18 years) presents methodological challenges compared to application in adults. One challenge is to account for age-based biopsychosocial developmental differences between children and adults and across children of different ages [5–7]. Distinguishing the age or age group of the target childhood population is important for content validity or concept coverage of the childhood PROM, its capacity for child self-report, appropriate design, and the culturally appropriate age for child self-report [2].

There are many ways that PROMs can be categorised. They can be divided into generic measures and disease or condition-specific measures, and further into domain-specific measures and multidimensional measures [4, 8]. Generic measures have the advantage of allowing comparisons across conditions and interventions. Multidimensional measures can be both generic and condition-specific and capture the multifaceted nature of concepts including health, QoL or HRQoL. PROMs can thus be further categorised by the concept(s) they seek to measure through their descriptive systems. There are multiple definitions of these concepts in the literature, with terms often used interchangeably [3, 9]. In this paper, we draw on the categories arising from a synthesis of definitions of functioning, disability, health, HRQoL and QoL used by the World Health Organization (WHO). In this taxonomy, a QoL/HRQoL measure can be distinguished from a functional, disability and health (FDH) measure by its reflection of the individual respondent’s perception, or subjective judgement of importance, of their assessed status [3]. Specifically, an FDH measure captures the ‘interactions among body structures and function, and activities and participation in the context of the environment and personal factors’, whilst QoL is ‘a person’s perception of [his/her] position in life’, where perception involves a subjective judgement over how the position relates to his/her goals, expectations, standards, enjoyment or concerns and not just a self-report of the position. HRQoL represents the individual’s ‘perception of his/her health and health-related states’ where ‘health’ represents a narrower domain than ‘position in life’ (p. 1086) [3].

PROMs can be accompanied by preference-based value sets which produce an overall index when applied to the multidimensional states generated by the descriptive systems [8]. PROMs accompanied by preference-based value sets are often referred to as multi-attribute utility instruments in the literature [10]. The value sets accompanying these measures use stated preference methods including standard gamble (SG) and time trade-off (TTO) to trade-off between a health state and mortality risk or life expectancy, respectively [11]. A key aspect of these methods is their ability to yield values that are anchored on a scale with 0 = dead and 1 = full health, as required for the use of values for estimating quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in cost-utility analysis. Negative values are theoretically possible and represent health states considered worse than being dead. Discrete choice experiments (DCE) can also be used to elicit stated preferences for value sets for PROMs, although the resulting values lie on a latent scale unless accompanied by additional methods to allow anchoring at dead = 0 [12]. Decision makers around the world have shown a preference for country-specific value sets reflecting underlying differences in preferences of different populations [13–15].

There are considerable methodological challenges that arise in valuing childhood PROMs. Among them, there is contention around whose preferences are relevant, with some instruments offering both adult- and child-elicited value sets [16]. Eliciting values from children themselves may help to ensure that health services are relevant to their needs [17, 18], particularly when adults’ and children’s preferences differ [19]. However, there are practical and ethical issues surrounding the age at which children can be asked to participate in stated preference studies, especially where these include tasks that involve trade-offs with life expectancy. Both SG and TTO may impose high cognitive and/or emotional burden on children relative to DCE or best–worst scaling (BWS) tasks [17]. Where values are used to inform the allocation of healthcare resources financed primarily from taxation, a common normative position is that these should be based on the preferences of the adult general public [12, 20]. However, valuing childhood PROMs using adults’ preferences also raises issues. For example, it is unclear whether the respondent should be asked to think about themselves as a child, their child or another child [20].

Several systematic reviews of generic multidimensional childhood PROMs have been published since 2000 [3, 4, 21–26]. The most recent, by Janssens et al., identified 63 unique versions of PROMs (including eight accompanied by value sets) published between 1992 and 2011 [4]. Their review tabulated the characteristics of PROMs, including target age range, respondent type, domain coverage and several design features (e.g. number of items, response options and recall period) [4]. That review also mapped the domains of the PROMs onto the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Child and Youth version (ICF-CY) framework [27], but noted the shortcoming of conflating the domains of FDH and QoL/HRQoL measures that have a different conceptual basis. It did not distinguish between types of informant response as recommended by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) guideline, i.e. proxy if the informant infers the child’s perception of health/QoL states and observer if the informant focuses on observable traits without inferring perception [2]. Moreover, little attention was paid to differences in characteristics of measures across age groups, or the value set features. Fayed and colleagues distinguished between FDH and QoL/HRQoL measures; however, their search period was limited to 2004–2008 [3]. Cremeens et al. [21] and Grange et al. [24] limited their reviews to 3- to 8-year-olds and < 5 year olds, respectively, which hinders comparisons of PROM characteristics across all childhood age groups. Finally, Chen and Ratcliffe previously reported on the features of nine childhood PROMs accompanied by value sets, but this was not a systematic review [10]. These gaps in previous studies inform the aim and objectives of this systematic review.

Aim and Objectives

This systematic review aims to generate a comprehensive catalogue of generic multidimensional childhood PROMs that rely on child self- and/or informant-report (hereafter childhood PROMs for brevity in accordance with the ISPOR guideline [2]) and the value sets that accompany them. In doing so, we aim to inform the development, selection and interpretation of childhood PROMs for clinical and population research and cost-effectiveness-based decision-making. Accordingly, the objectives are to:

Systematically identify generic multidimensional childhood PROMs and preference-based value sets that accompany them.

Categorise the PROMs according to conceptual basis and target age group and evaluate their methodological features according to the ISPOR good research practice recommendations on the use of childhood PROMs [2].

Catalogue the value sets that exist for childhood PROMs, compare the methods that have been used to produce them and report the characteristics of the resulting value sets.

Methods

A pre-specified protocol outlining the systematic review methods was developed and registered with the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021230833). For reporting purposes, the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28]. See the Supplementary Information for the PRISMA checklist for this paper (see the electronic supplementary material).

Data Sources and Study Selection

Two independent systematic database searches were conducted. The first aimed to identify primary development studies for generic multidimensional childhood PROMs published between 1 January 2012 and 16 October 2020. Studies identified in the search were pooled with those published between 1 January 1992 and 20 March 2012 identified in the earlier systematic review by Janssens et al. [4]. A second search was conducted without date limits on 18 February 2021 to identify preference-based value sets for generic multidimensional childhood PROMs. This was constructed around measures identified by the first search that reported the development of a value set or the objective to develop a value set or to inform economic evaluations. Developers of PROMs were also contacted to confirm whether, to the best of their knowledge, there was no missing published value set.

Both systematic searches covered seven academic databases (Medline, Embase, PsycInfo via Ovid, EconLit via Proquest, CINAHL via EBSCOHost, Scopus and Web of Science) and one grey literature database (PROQOLID). The Medline search strategy for the first and second searches are presented in Tables A and B in the Supplementary Information (see the electronic supplementary material). Searches were limited to English language texts. In both searches, references were imported into Endnote X9 and duplicates were removed. References were then exported into Covidence [29], where two researchers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified articles. If an article received two approvals, it proceeded to the next stage, with disagreements referred to a third reviewer for the final assessment. Full text articles were independently reviewed by two reviewers with disagreements again referred to the third reviewer for final assessments.

The inclusion criteria for the systematic search of PROMs were as follows: studies reporting the development of a generic multidimensional childhood (aged ≤ 18 years) PROM and studies published in the English language. Conference abstracts with sufficient information (i.e. containing at least the acronym/name of the instrument(s), the aim/motivation of development, whether a general childhood population was targeted, and the multidimensionality of the instrument) were included alongside full text articles. Studies in adults only and animals were excluded, as were commentaries, single case reports and secondary application of PROMs. References of included studies were searched, including those published before 1 January 2012. The inclusion criteria for the systematic search to identify value sets were as follows: studies reporting the development of a value set for one or more generic multidimensional childhood PROM; the value set was anchored on a 0–1 scale required for the use of the values in QALY estimation; and studies (including full text articles and a user’s manual [no conference abstracts were identified]) published in the English language. Studies that only reported values for a sub-set of the health states described by a childhood PROM were excluded.

Data Extraction

For the first review that identified generic multidimensional childhood PROMs, data for each measure were extracted independently by two reviewers per article from a pool of eight reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion. For the second review that identified preference-based value sets, data for each value set were extracted by one reviewer, with a 20% check performed by a second reviewer. For the identified generic multidimensional childhood PROMs, the following characteristics were extracted according to proformas in Excel: acronym/name of the instrument, name of author(s)/developer(s), development year and country(ies), aim/motivation of development, target age range, background concept (e.g. definition of health/QoL adopted before commencing PROM development), development methods (e.g. focus groups with children for item selection), role of children in development, level of child’s perception captured, respondent type (e.g. child, proxy, observer), administration mode (e.g. by self, by interviewer), recall period, domains covered, number of items, response options and method for score generation (other than value set application).

For the identified value sets of the generic multidimensional childhood PROMs, the following characteristics were extracted: acronym/name of the instrument, name of author(s)/developer(s), valuation year and country(ies), methods for selecting valued health states, number of valued health states, sampling methods for valuation including target population, recruitment strategies, response rates, sample size, representativeness of sample and reasons for exclusion, and stated preference data collection methods. The latter included elicitation technique(s) (e.g. SG, TTO, DCE), the approach taken to anchoring at 0–1, characteristics of respondents, perspective and administration mode, and modelling methods. Finally, the properties of the value sets were examined (e.g. value range, proportion of health states with negative values). As some of these properties were not reported in the papers, we coded the value set algorithms based on the published results and calculated the index scores for all potential health states according to the classification system of the instruments.

Data Synthesis

Using a method similar to that of Fayed et al. [3], the generic multidimensional childhood PROMs identified were categorised by conceptual basis. The wording and response options for measure items were reviewed independently by two reviewers per article from a pool of eight reviewers. Measures with 75% or more of items that captured a child’s perception (i.e. relation to enjoyment, satisfaction, goals, expectations, standards or concerns) on health or broader position in life were labelled HRQoL or QoL measures, respectively. Measures with 25% or fewer items capturing a child’s perception were labelled FDH measures. Those with between 25 and 75% of items capturing a child’s perception were labelled hybrid HRQoL-FDH or QoL-FDH measures. Fayed and colleagues similarly described the hybrid nature of many measures: e.g. the General Health Questionnaire was classified as ‘FDH and QoL/HRQoL’, the HUI as ‘FDH (with one HRQoL/QoL attribute)’ and the KIDSCREEN as ‘HRQoL/QoL (with some functioning features)’. Instead of these mixed descriptions, this study specifies cut-off levels to allow for comparison across a wide range of measures.

Distinguishing between QoL and HRQoL was particularly challenging given the overlap between health and position in life. Indeed, Fayed et al. do not make this distinction in their results, grouping QoL and HRQoL under the same category [3]. A two-step pragmatic approach was taken: (1) refer to the stated aim/motivation of the study prior to measure development or use (e.g. some studies gave the definition of QoL or HRQoL and underlying constructs [30, 31]), and if still unclear, then (2) categorise as HRQoL measures if more than 50% of the domains cover body functioning, disabilities and daily activities (e.g. mobility, pain, vision, anxiety, depressive symptoms, chronic illness, dressing and grooming) that would constitute the concept of FDH as defined by Fayed et al. [3].

When step (1) in this pragmatic approach could not be applied (i.e. the study used conceptual labels without clearly defining them), we did not automatically apply the conceptual labels given to PROMs by the developer(s). Fayed et al. documented the discrepancies between the conceptual bases as labelled by developers and secondary applications of PROMs and those as classified by their review. For example, Fayed et al. noted that the HUI and the PedsQL were labelled as HRQoL/QoL measures in the primary and secondary literature but are more accurately labelled FDH measures [3]. In the current review, conceptual bases were similarly assigned according to extracted data rather than existing labels (unless clearly defined), but we did not document the discrepancies as was done by Fayed et al.

For measures that use informant responses, the informant type was classified according to the ISPOR guideline [2], namely proxy for QoL/HRQoL measures (since informants infer the child’s subjective perception) and observer for FDH measures (since no such inference is made). For hybrid QoL/HRQoL-FDH measures, the informant type was labelled hybrid proxy-observer.

Following the ISPOR good research practices guideline [2], we explored differences in measurement characteristics for PROMs targeted at different age groups. The ISPOR guideline’s age cut-offs were used to categorise the measures by their target age group: less than 5 years, covering infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers; 5–7 years for younger pre-adolescents; 8–11 years for older pre-adolescents; and 12–18 years for adolescents. We then explored how the characteristics of the measures (including range of domains covered, respondent and informant type, and other design features) varied by conceptual basis and target age. In cases where target ages were not clearly specified, inferences were made from the study aim and development methods to assign the target age category.

The level of content validity of each PROM was assessed according to whether children of the target age were involved in (1) the development of the measure, including qualitative research for domain and item elicitation, and (2) assessment of comprehension using cognitive interviews and/or pilot/feasibility studies. Note that appraisals of other psychometric properties such as construct validity and internal consistency are not reported here but in forthcoming work. Cultural issues present in the initial instrument development (as opposed to subsequent translations and secondary cross-cultural adaptations of the developed instrument) were similarly described.

For the review of value sets for generic multidimensional childhood PROMs, data were analysed using narrative synthesis. Summary tables were used to describe the bibliography/setting, sampling methods, preference data collection methods and statistical features of the identified value sets. Separate summaries of the modelling methods are presented for two categories of preference elicitation techniques: TTO, SG and rating scales (RS); DCEs and BWS.

Results

Search Results

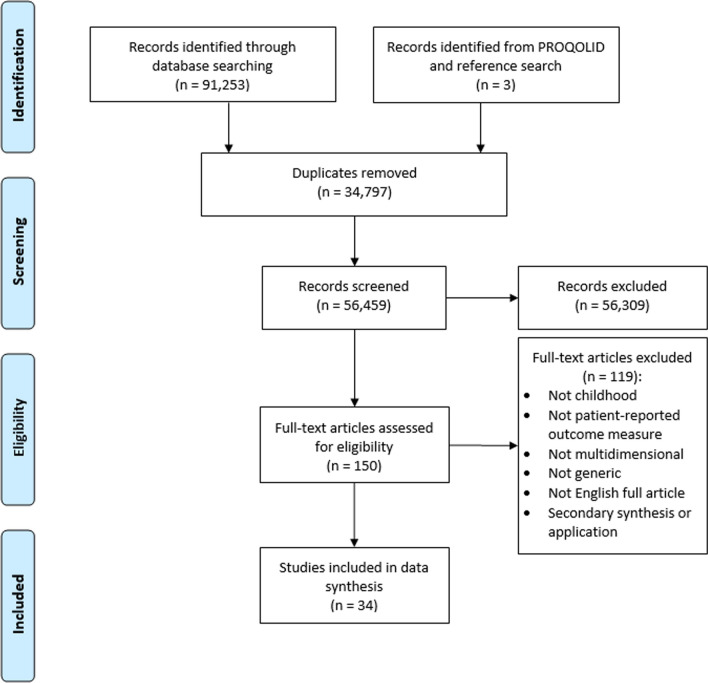

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the first search that identified primary studies developing generic multidimensional childhood PROMs published between 1 January 2012 and 16 October 2020.

Fig. 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for database searches for studies developing generic multidimensional childhood patient-reported outcome measures published between 1 January 2012 and 16 October 2020

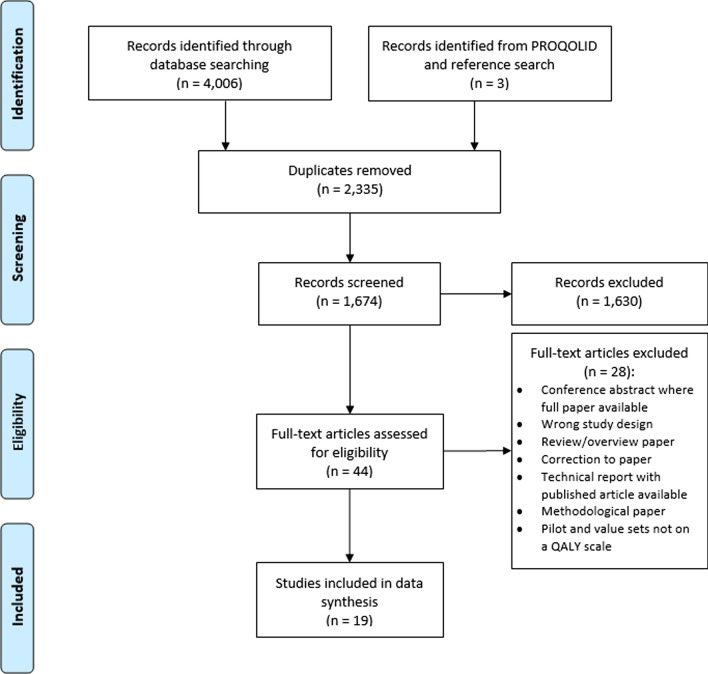

Thirty-four eligible studies were identified that described 26 PROMs. Sixty-three PROMs included in the review by Janssens et al. [4] that met the inclusion criteria were included to give 89 PROMs in total. Fourteen PROMs were accompanied or designed to be accompanied by preference-based value sets. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the identification of value sets for these 14 PROMs. Nineteen studies were identified in total that described 21 value sets.

Fig. 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for database searches for valuation studies for generic multidimensional childhood PROMs identified by search strategies. PROM patient-reported outcome measure, QALY quality-adjusted life year

Overview of Generic Multidimensional Childhood Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the identified generic multidimensional childhood PROMs that are not accompanied by or designed to be accompanied by preference-based value sets, while Table 2 does so for PROMs designed to be accompanied by preference-based value sets. Some measures have several versions, and Table 1 includes all distinct versions, providing a total of 110 unique measures (for example, the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales are composed of age-specific modules for toddlers, young children, children and teens [32]). Of the 110 measures, 52 are FDH measures, 29 are QoL measures, 12 are HRQoL measures, nine are hybrid QoL-FDH measures, and eight are hybrid HRQoL-FDH measures. Seventeen measures (reflecting two versions each for HUI2 and HUI3 and two variants of the EQ-5D-Y) are designed to be accompanied by preference-based value sets. The measures were primarily developed in high-income countries (using the 2021 World Bank classifications [33]), with only seven (6%) developed in lower- or middle-income country (LMIC) settings as part of an international development process [34–40].

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included generic multidimensional childhood patient-reported outcome measures not designed to be accompanied by preference-based value setsa

| # | Acronym: name | Reference; country | Target age (years) | Perception captured (category)b | Respondent type | Administration mode | Recall period | Domains (number, n) | Items n | Response options [scoring method] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ACHWM: Aboriginal Children's Health and Well-Being Measure | Young [48]; Canada | 8–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By staff; computer tablet | General | Spiritual; emotional; physical; mental (n = 4) | 65 | Frequency, degree of importance, yes/no (60 items); open-ended (5) [item average] |

| 2 | QUALIN: Infant's Quality of Life | Manificat [88, 106]; France | 0–3 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | General | Psychomotor development; family environment; psychopathological; sociability (n = 4) | 33 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 3 | AUQUEI Nursery: Child Pictured Self Report Nursery version | Manificat [88, 107]; France | 3–6 | Yes (QoL) | Child, aided by parents | By self | General | Family life; Social life; activities at school and leisure; health (n = 4) | 28 | 4-level pictorial happy-sad faces (26 items); open-ended (2) [item average] |

| 4 | AUQUEI Primary: AUQUEI for primary school child | Manificat (2002)c [88]; France | 6–11 | Yes (QoL) | Child, aided by parents | By self | General | Family life; social life; activities at school and leisure; health (n = 4) | 33 | 4-level pictorial happy-sad faces for satisfaction (31 items); open-ended (2) [item average] |

| 5 | OK.ado: Adolescent quality of life | Manificat (2002b) [61]; France | 11–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Leisure and relationships; school; family; self-esteem (n = 4) | 34 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 6 | CHAQ: Child Health Assessment Questionnaire | Singh [62]; US | 8–19 | No (FDH) | Child; Observer | By self | Past week | Dressing and grooming; arising; eating; walking; hygiene; reach; grip; activities. Also: aids/devices for functioning; activities needing assistance; VAS pain; VAS wellbeing (n = 8 + Aids/VAS) | 34 | 4-point scale for functioning (30 items); VAS (2); list of aids used (1); list of activities needing assistance (1) [highest item score in domain as domain score; domain average] |

| 7 | CHAQ Informant only | Singh [62] | 1–7 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past week | See CHAQ | 34 | See CHAQ |

| 8 | CHAQ38: CHAQ revised version, 38 items | Lam [108]; Canada | 5–19 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self | Past week | Same domains as CHAQ plus 8 additional items on age-appropriate physical activities and challenges | 38 | 4- or 5-point scale [item average] |

| 9 | CHAQ38 Information only | Lam [108] | < 5 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past week | See CHAQ38 | 38 | See CHAQ38 |

| 10 | CHIP-AE: Child Health and Illness Profile—Adolescent Edition | Starfield [7, 109]; US | 11–17 | No (FDH) | Child | By self | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction; comfort; resilience; risk avoidance; achievement; disorders (n = 6) | 107; 46 disease-specific items | 5-point scale [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 11 | CHIP-CE CRF: Child Health and Illness Profile—Child Edition Child-Report Form | Riley [110]; US | 6–11 | No (FDH) | Child | By self | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction; comfort; resilience; risk avoidance; achievement (n = 5) | 45 | 5 graduated circle responses with cartoons at beginning/end [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 12 | CHIP-CE PRF: CHIP-CE Parent-Report Form (long version) | Riley (2004b) [111]; US | 6–11 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction; comfort; resilience; risk avoidance; achievement (n = 5) | 76 | 5-point scale [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 13 | CHIP-CE PRF (short version) | Riley (2004b) [111]; US | 6–11 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction; comfort; resilience; risk avoidance; achievement (n = 5) | 45 | 5-point scale [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 14 | CHQ-PF50: Child Health Questionnaire Parent Form (long version) | Landgraf [112]; US | 5–18 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Proxy observer | By self; mail | Past 4 weeks; general for global health and family cohesion; compared to last year for change in health | Physical functioning; bodily pain; role functioning, physical; role, emotional; role, behavioural; general health perception; self-esteem; mental health; general behaviour; change in health; parental time impact; family activities; family cohesion (n = 13) | 50 | 4- to 6-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 15 | CHQ-PF28: CHQ-PF (short version) | Raat [113]; US | 5–18 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Proxy-observer | By self | Past 4 weeks; general for global health and family cohesion; compared to last year for change in health | Physical functioning; bodily pain; role functioning, physical; role, emotional or behavioural; general health perception; self-esteem; mental health; general behaviour; change in health; parental emotional impact; parental time impact; family activities; family cohesion (n = 13) | 28 | 4- to 6-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 16 | CHQ-CF87: CHQ Child Form (long version) | Landgraf [114]; US | 10–18 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Child | By self | Past 4 weeks; general for global health and family cohesion; compared to last year for change in health | Physical functioning; bodily pain; role functioning, physical; role, emotional; role, behavioural; general health perceptions; self-esteem; mental health; general behaviour; change in health; family activities; family cohesion (n = 12) | 87 | 4- to 6-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 17 | CHQ-CF45: CHQ-CF (short version) | Landgraf [52]; US, The Netherlands | 10–18 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Child | By self: paper or online | Past 4 weeks; general for global health and family cohesion; compared to last year for change in health | Physical functioning; Bodily pain; role functioning, physical; role, emotional or behavioural; general health perceptions; self-esteem; mental health; getting along; global behaviour; change in health; family activities; family cohesion (n = 12) | 45 | 4- to 6-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 18 | CHRS: Children's Health Ratings Scale | Maylath [115]; US | 9–12 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child, aided by staff; proxy | By self | Current; general | No domain structure but includes a range of questions on general health perceptions | 17 | 5-point scale [item sum] |

| 19 | CHSCS: Child's Health Self-Concept Scale | Hester [116]; US | 5–13 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | By self, aided by staff before start | General | Psychosocial; physical health; healthiness; values; energy (n = 5) | 34 | 4-point scale: binary choice for positive or negative perception on health issue; 2-point scale on strength of perception [not stated] |

| 20 | ComQOL-S5: Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale—School version, 5th edition | Gullone [54]; Australia | 11–18 | Some (QoLd) | Child | By self | Past three months; general | Material wellbeing; health; productivity; intimacy; safety; place in community; emotional wellbeing (n = 7) | 21 | 5-point scale for frequency, importance and satisfaction [item sum weighted by importance score] |

| 21 | COOP Charts: Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Project Charts | Wasson [95]; US | 12–21 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | By self | Past month | Physical fitness; emotional feelings; school work; social support; family communications; health habits (n = 6) | 6 | 5-point scale with descriptors and cartoons (picture-and-word chart) [item average] |

| 22 | CQoL: Child Quality of Life | Graham [117]; UK | 9–15 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | Past month | Activities; appearance; communication; continence; depression; discomfort; eating; family; friends; sight; mobility; school; self-care; sleep; worry; global QoL (n = 15) | 45 | 7-point scale [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 23 | DHP-A: Duke Health Profile—Adolescent version | Vo [118]; France | 12–19 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | By self | Past week | Physical health; mental health; social health; general health; perceived health; self-esteem; anxiety; depression; pain; disability (n = 10) | 17 | 3-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 24 | ExQoL: Exeter Quality of Life | Eiser [41]; UK | 6–12 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self, supervised; computer | General | Symptoms; social wellbeing; School achievements; physical activity; worry; family relationships (n = 6) | 12 | 12 pictures, each rated twice using VAS—(1) ‘like me’; (2) ‘I would like to be’ [item average] |

| 25 | FSIIR Infants: Functional Status II Revised, long version, Infants | Stein [119]; US | 0–1 | No (FDH) | Observer | By interviewer | Past 2 weeks | General health; total functional status; responsiveness (n = 3) | 20 | 3-point scales for function difficulty and extent due to illness [item sum as proportion of maximum] |

| 26 | FSIIR Toddlers | Stein [119]; US | 1–2 | No (FDH) | Observer | By interviewer | Past 2 weeks | General health; total functional status; responsiveness (n = 3) | 28 | See FSIIR Infants |

| 27 | FSIIR Pre-schoolers | Stein [119]; US | 2–3 | No (FDH) | Observer | By interviewer | Past 2 weeks | General health; total functional status; activity (n = 3) | 38 | See FSIIR Infants |

| 28 | FSIIR School children | Stein [119]; US | 4–16 | No (FDH) | Observer | By interviewer | Past 2 weeks | General health; total functional status; Interpersonal functioning (n = 3) | 39 | See FSIIR Infants |

| 29 | FSIIR-14: FSIIR 14 items (short version) | Stein [119]; US | 0–16 | No (FDH) | Observer | By interviewer | Past2 weeks | No domain structure but includes a range of questions on general health | 14 | See FSIIR Infants |

| 30 | GCQ: Generic Children's Quality of Life | Collier [120]; UK | 6–14 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | General | General affect; peer relationships; attainments; relationships with parents; general satisfaction (n = 5) | 25 | 5-point scales for: perceived self and preferred self; based on story child characters [item sum] |

| 31 | HAY: How Are You | Le Coq [121]; The Netherlands | 8–12 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | By self | Past week | Generic domains: physical; cognitive; social; physical complaints. asthma-specific domains (n = 5) | 32 | 4-point scale rating frequency, quality of performance and related feelings [item sum per subdomain as proportion of maximum] |

| 32 | HDQ Age 6: Health Dialogue Questionnaire for Age 6 | Holmström 2012) [122]; Sweden | 6 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Proxy-observer | By school nurse | Not stated | Physical; mental; social (n = 3) | 15 | 5-point scale [positive response as proportion of total questions] |

| 33 | HDQ Age 10 | Holmström (2012b) [123]; Sweden | 10 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Child, aided by parent | By school nurse | Not stated | Physical; mental; social (n = 3) | 15 | See HDQ Age 6 |

| 34 | HDQ Age 13 | Olofsson [124]; Sweden | 13 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Child, aided by parent | By school nurse | Not stated | Physical; mental; social (n = 3) | 15 | See HDQ Age 6 |

| 35 | HDQ Age 16 | Kristiansen [125]; Sweden | 16 | Some (HRQoL-FDH) | Child, aided by parent | By school nurse | Not stated | Physical; mental; social (n = 3) | 22 | See HDQ Age 6 |

| 36 | Healthy Pathways CRS: Healthy Pathways Child-Report Scales | Bevans [42]; US | 10–12 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | Schools with computer access: by self; computer. No access: by self for 6th graders; by interviewer for 4th/5th; paper | Past 4 weeks | Comfort; energy; resilience; risk avoidance; subjective wellbeing; achievement (n = 6) | 88 | 5-point scale [item average per subdomain] |

| 37 | Healthy Pathways PRS: Healthy Pathways Parent-Report Scales | Bevans [92]; US | 10–12 | Yes (HRQoL) | Proxy | By self | Past 4 weeks | Comfort; energy; resilience; risk avoidance; wellbeing; achievement (n = 6) | 59 | 5-point scale [item average per subdomain] |

| 38 | ILC: Inventory of Life quality in Children and adolescents | Jozefiak (2016)e [126]; Germany | 10–16 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | Past week | Global QoL; school performance; family functioning; social integration; interests and hobbies; physical health; mental health (n = 7) | 7 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 39 | ITQOL: Infant Toddler Quality of Life (long version) | Klassen [127]; Canada | 2 months–5 years | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; mail | Past 4 weeks; general for global health; compared to last year for change in health | Physical; growth and development; bodily pain; temperament/moods; general behaviour; getting along; general health perceptions; change in health; parental impact—emotion; time; mental; family cohesion; general health (n = 13) | 103 | 5-point scale except 4-point scale for parental time impact [item average per domain] |

| 40 | ITQOL SF47: ITQOL Short Form | Landgraf [128]; The Netherlands | 2 months–5 years | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past 4 weeks; general for global health; compared to last year for change in health | Physical; growth and development; bodily pain; temperament/moods; general behaviour; getting along; general health perceptions; change in health; parental impact—emotion; time; mental; family cohesion; general health (n = 13) | 47 | 5-point scale except for 4-point scale for parental time impact [item average per domain] |

| 41 | Kiddy-KINDL CQ: Kiddy-KINDL Children’s Questionnaire | Ravens-Sieberer (1998)f [89]; Germany | 4–6 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Child | By interviewer | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school (n = 6) | 12 | 3-point scale [item average] |

| 42 | Kiddy-KINDL PQ: Kiddy-KINDL Parents’ Questionnaire | Ravens-Sieberer [89]; Germany | 3–6 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Proxy-observer | By self | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school; child behaviour (n = 7) | 46 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 43 | Kid-KINDL CQ: Kid-KINDL Children’s Questionnaire | Ravens-Sieberer [89]; Germany | 7–13 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Child | By self | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school (n = 6) | 24 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 44 | Kiddo-KINDL AQ: Kiddo-KINDL Adolescents’ Questionnaire | Ravens-Sieberer [89]; Germany | 14–17 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Child | By self | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school (n = 6) | 24 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 45 | Kid- & Kiddo-KINDL PQ: Kid- & Kiddo-KINDL Parents’ Questionnaire | Ravens-Sieberer [89]; Germany | 7–17 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Proxy-observer | By self | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school (n = 6) | 24 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 46 | KINDL CAT-SCREEN: KINDL Computer Assisted Touch version | Ravens-Sieberer [43]; Germany | 6–17 | Some (QoL-FDH) | Child | By self; computer assisted (visual and audio) | Past week | Physical health; emotion; self-esteem; family; friends; school (n = 6) | 24 | 5-point scale [item average] |

| 47 | KIDSCREEN-52 | Ravens-Sieberer (2003); [56, 57]; 13 European countriesg | 8–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | Past week | Physical wellbeing; psychological wellbeing; moods and emotions; self-perception; autonomy; parent relations and home life; social support and peers; school environment; social acceptance; financial resources (n = 10) | 52 | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 48 | KIDSCREEN-27 | Ravens-Sieberer [58]; 13 European countriesg | 8–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | Past week | Physical wellbeing; psychological wellbeing; parent relations and autonomy; social support and peers; school environment (n = 5) | 27 | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 49 | KIDSCREEN-10 | Ravens-Sieberer [59]; 13 European countriesg | 8–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | Past week | Physical activity; depressive moods and emotions; social and leisure time; relationship with parents; relationship with peers; cognitive and school performance (n = 6) | 10 | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 50 | Kids-CAT: KIDSCREEN Computerized Adaptive Test | Devine (2015); Barthel [46, 129]; Germany | 7–17 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self; computerized adaptive test | Past week | Physical wellbeing; psychological wellbeing; parent relations; social support and peers; school wellbeing; chronic-generic QoL (n = 6) | 42h | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 51 | MCWBS: Multidimensional Child Well-Being Scale | Jiang [34]; China | 10–15 | No (FDH) | Child | By self, aided by staff before start | General | Physical; psychological; social; educational (n = 4) | 30 | 5-point scale [not stated] |

| 52 | Nordic QoLQ: Nordic Quality of Life Questionnaire for children | Lindström [130]; 5 Nordic countriesi | 12–18 | Some (QoLd) | Child and parent; proxy-observer | By self; mail | Past 3 months | External conditions; interpersonal conditions; psychological conditions (n = 3) | 25 | Unclear [item score dichotomised and averaged] |

| 53 | Nordic QoLQ Informant only | Lindström [130] | 2–11 | Some (QoLd) | Proxy-observer | By self; mail | Past three months | See Nordic QoLQ | 25 | See Nordic QoLQ |

| 54 | PedsQL GCS Toddler: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 Generic Core Scales, Toddler | Varni (2001)j [32]; US | 2–4 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self (paper); by interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 55 | PedsQL GCS Young Child | Varni [32]; US | 5–7 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child: by interviewer, informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | Child: 3-level pictorial faces, Informant: 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 56 | PedsQL GCS Child | Varni [32]; US | 8–12 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child and informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 57 | PedsQL GCS Teen | Varni [32]; US | 13–18 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child and informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 58 | PedsQL SF15 Toddler: PedsQL 4.0 Short Form, Toddler | Chan (2005)j [131]; US | 2–4 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self (paper); by interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 59 | PedsQL SF15 Young Child | Chan [131]; US | 5–7 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child: by interviewer, informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | Child: 3-level pictorial faces, Informant: 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 60 | PedsQL SF15 Child | Chan [131]; US | 8–12 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child and informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 61 | PedsQL SF15 Teen | Chan [131]; US | 13–18 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Child and informant: by self or interviewer (telephone) | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; school (n = 4) | 23 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 62 | PedsQL Infant Scales (1–12 months) | Varni (2011)j [132]; US | 1–12 months | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; mail | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; cognitive; physical symptoms (n = 5) | 36 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 63 | PedsQL Infant Scales (1–24 months) | Varni [132]; US | 13–24 months | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; mail | Past month (past week for acute version) | Functioning: physical; emotional; social; cognitive; physical symptoms (n = 5) | 45 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 64 | P-MYMOP: Paediatric Measure Yourself Medical Outcomes Profile | Ishaque [133]; Australia | 7–11 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child, aided by parent | By self | Past week | Symptom 1; symptom 2; activity impairment; general wellbeing (child specifies symptoms and activity impairment affecting her most) (n = 4) | 4 | 7-point pictorial faces [item average] |

| 65 | PQ-LES-Q: Pediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire | Endicott [63]; US | 6–17 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self, unassisted as far as possible | Past week | Health; mood/feelings; school/learning; helping at home; getting along with friends; getting along with family; play/free time; getting things done; love/affection; getting/buying things; place you live at; paying attention; energy level; feelings about yourself; global QoL (n = 15) | 15 | 5-point scale [item sum as proportion of maximum] |

| 66 | PROMIS PIB: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System—Pediatric Item Banks | Varni [44]; US | 8–17 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self; computer | Past week | Mobility; upper extremity; peer relationships; depressive symptoms; anxiety; anger; pain interference; lack of energy; tired; asthma impact (n = 10) | 165 | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 67 | PROMIS PIB SF: PROMIS PIB Short Form | DeWalt [45]; US | 8–17 | No (FDH) | Child | By self; computer | Past week | Mobility; upper extremity; peer relationships; depressive symptoms; anxiety; anger; pain interference; fatigue (n = 8) | 64 | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 68 | PROMIS PIB CAT: PROMIS PIB Computerized Adaptive Test | Varni [47]; US | 8–17 | No (FDH) | Child | By self; computer | Past week | Mobility; upper extremity; peer relationships; depressive symptoms; anxiety; anger; pain interference; fatigue (n = 8) | 5–12 items per domain | 5-point scale [Rasch score] |

| 69 | PROMIS PGH7: PROMIS Pediatric Global Health 7-item | Forrest [53]; US | 8–17 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self; online | General | General health; quality of life; physical health; mental health; sad; fun with friends; parents listen to ideas (n = 7) | 7 | 5-point scale [item sum] |

| 70 | PROMIS PGH7 Informant only | Forrest [53] | 5–7 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; online | General | See PROMIS PGH7 | 7 | See PROMIS PGH7 |

| 71 | PROMIS EC: PROMIS Early Childhood | Blackwell [87]; US | 1–5 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self | Past week/month | (A) Global health. (B) Mental health: anger; anxiety; depressive symptoms; positive affect; engagement—curiosity; engagement—persistence; self-control—adaptability; Self-control—self-regulation. (C) Social relationships. (D) Physical health: physical activity; sleep health (n = 12) | 138 | Not yet developed |

| 72 | PWI-SC: Personal Wellbeing Index, School Children | Cummins [64]; Australia | 5–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self or interviewer | Current | Standard of living; health; life achievement; personal relationships; personal safety; community-connectedness; future security; global QoL (n = 7) | 7 | 11-point scale (happiness) [item average] |

| 73 | PWI-SC8: PWI-SC, 8 items | Vaqué-Crusellas [134]; Spain | 10–12 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self, in classroom with adult help available) | Current | Standard of living; health; life achievement; personal relationships; personal safety; community-connectedness; future security; food satisfaction (n = 8) | 8 | 11-point scale (happiness) [item average] |

| 74 | QLQC: Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children | Bouman [135]; The Netherlands | 8–12 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | By self | Past 2 months | Physical: complaints; limitations; handicaps. Psychological: general wellbeing; cognitive; self-concept; anxious-depressed. social relations: parents (child-report only); siblings; peers; school; social conflicts; leisure-time activities (n = 13) | 81 | 3-point scale [item sum] |

| 75 | QLSI-C: Quality of Life Systemic Inventory for Children | Etienne [30]; Belgium | 8–12 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By interviewer | Current | Physical; emotional; cognitive; social; family functioning (n = 5) | 20 | Multi-component state-goal gap identification approachk [item average weighted by importance and rate of progress to goal] |

| 76 | QLSI-C Tablet: QLSI-C Tablet version | Touchèque [49]; Belgium | 8–12 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self; tablet | Current | Physical; emotional; cognitive; social; family functioning (n = 5) | 20 | See QLSI-C |

| 77 | QoL-C: Quality of Life Scale for Children | Thompson [6]; UK | 4–9 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | Age 47: by interviewer, age 8–9: by self in class, informant: by self; mail | Today | Moving; looking after myself; doing usual activities; having pain; feeling worried, sad or unhappy; global health VAS (n = 5 + VAS) | 5 | 3-level pictorial faces; VAS [item sum] |

| 78 | QOLPAV: Quality of Life Profile: Adolescent Version | Raphael [136]; Canada | 15–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By staff in groups | Not stated | Being (physical, psychological, spiritual); belonging (physical, social, community); becoming (practical, leisure, growth) (n = 3) | 54 | 5-point scales: importance; enjoyment and satisfaction. Control and opportunity scores for context [item average per subdomain; subdomain average] |

| 79 | QOLQA: Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adolescents | Wang [35]; Japan; China | 12–15 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Physical; psychological; independence; social relationship; environment (n = 5) | 70 | 5-point scale [item average per domain; domain average] |

| 80 | QOLQA-Taiwan: QOLQA Taiwanese version | Fuh [65]; Taiwan | 13–15 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Family; residential environment; personal competence; social relationships; physical appearance; psychological wellbeing; pain (n = 7) | 38 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 81 | SLSS: Student Life Satisfaction Scale | Huebner [137]; US | 8–14 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By group, questions read by staff | Past several weeks | No domain structure but includes a range of questions on life satisfactionl | 7 | 4-point scale [item sum] |

| 82 | MSLSS: Multidimensional SLSS | Huebner [138]; US | 8–14 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By group, questions read by staff | General | Family; friends; school; living environment; self (n = 5) | 40 | 4-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 83 | MSLSS Brief | Seligson [55]; US | 11–14 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Family; friends; school; living environment; self (n = 5) | 5 | 7-point scale. Importance rating scores obtained to weight each domain [item average per domain; domain average weighted by importance scores] |

| 84 | MSLSS-A: MSLSS Adolescent version | Gilligan [139]; US | 14–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Family; same-sex friends; school; living environment; self; opposite-sex relationship (n = 6) | 53 | 6-point scale [item average per domain; domain average] |

| 85 | TACQOL: TNO-AZL questionnaire for Children's health-related Quality of Life | Vogels [31]; Theunissen [140]; The Netherlands | 8–15 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child; Proxy | By self | Past few weeks | Pain and symptoms; motor functioning; autonomy; cognitive functioning; social functioning; global positive emotional functioning; global negative emotional functioning (n = 7) | 53 | 3-point scale for severity; 4-point scale for child's emotional response to item; combined into 3-point ordinal scale with range 0–2m [item sum per domain] |

| 86 | TACQOL Informant only | See TACQOL | 6–7 | Yes (HRQoL) | Proxy | By self | Past few weeks | See TACQOL | 53 | See TACQOL |

| 87 | TAPQOL: TNO-AZL questionnaire for Preschool children's health-related Quality of Life | Fekkes [141]; The Netherlands | 1–5 | Yes (HRQoL) | Proxy | By self | Past 3 months | Sleeping; appetite; lung problems; stomach problems; skin problems; motor functioning; problem behaviour; social functioning; communication; positive mood; anxiety; liveliness (n = 12) | 43 | 3-point scale for severity; 4-point scale for child's emotional response to item; combined into 5-point ordinal scale with range 0–4n [item sum per domain] |

| 88 | TedQL | Lawford [142]; UK | 3–8 | Yes (QoL) | Child; proxy | Child: by interviewero; informant: by self | Current | Physical competence; peer acceptance; maternal acceptance; psychological functioning; cognitive functioning (n = 5) | 23 | Two 4-level scales: colour circles vs. linear scale. Circles took less time and more internally consistent [item average as proportion of maximum] |

| 89 | VSP-A: Vecu et Sante Percue de l'Adolescent | Simeoni [143]; France | 11–17 | Yes (HRQoL) | Child | By self | Past month | Psychological wellbeing; energy/vitality; friends; parents; leisure; school (n = 6) | 40 | 5-point scale [item average per domain] |

| 90 | WCHMP: Warwick Child Health and Morbidity Profile | Spencer [144]; UK | 0–5 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self or interviewer | Not stated | General health status; acute minor illness; behavioural; accident; acute significant illness; hospital admission; immunization; chronic illness; functional health; HRQoL (n = 10) | 10 | 4-point scale and free text for detail [no scoring] |

| 91 | WHOQOL-BREF | Izutsu [36]; Bangladesh | 11–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By interviewer (due to low literacy) | Past 2 weeks | Physical; psychological; social relationships; environmental; global QoL and health satisfaction (n = 4) | 26 | 5-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 92 | YQoL-R: Youth Quality of Life instrument—Research version | Edwards (2002); Patrick [145, 146]; US | 12–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General | Sense of self; social relationships; environment; general quality of life (n = 4) | 41 | 11-point scale [item sum per domain] |

| 93 | YQoL-S: YQoL—Surveillance version | Topolski [147]; US | 12–18 | Yes (QoL) | Child | By self | General; past month | Contextual; perceptual (n = 2) | 10 | 5-point scale for Contextual items; 11-point scale for perceptual [item sum for Perception domain] |

FDH functioning, disability and health, HRQoL health-related quality of life, QoL quality of life, VAS visual analogue scale

aMeasures arranged alphabetically; family of measures (e.g. QUALIN, AUQUEI Nursery, AUQUEI Primary, OK.ado) arranged together

bDenotes whether the measure items capture child respondent’s perception (i.e. his/her enjoyment, satisfaction, expectations, standards and concerns) on health, health-related aspect or position in life: ‘yes’ if more than 75% of items did; ‘no’ if less than 25% of items did; ‘some’ if between 25% and 75% of items did. ‘Yes’ implies that the measure is predominantly a QoL or HRQoL measure; ‘no’ predominantly an FDH measure; and ‘some’ a mix of QoL/HRQoL and FDH

cThis article is a review of AUQUEI by instrument developers. The primary development study is not available in English

dContains subjective QoL and objective position in life items. Though the latter do not capture perception, they are associated with QoL rather than health. Hence, the measure is categorised as QoL, not QoL-FDH

eThis article is a secondary application study of ILC in Norway. The primary development study was set in Germany and is not available in English

fSee also questionnaire forms on website: https://www.kindl.org/english/questionnaires/

gAustria, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, France, The Netherlands, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Sweden, UK and Czech Republic

hDevine [46] reports that there are 155 items in total across item banks excluding chronic-generic QoL. Barthel [129] reports that the average number of items answered per child is around 42

iDenmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland

jSee also questionnaire forms on website: https://www.pedsql.org/index.html

k(1) Adjust arrows on pictorial sundial to indicate the gap the between desired and current states for each item. (2) Indicate how quickly one is advancing or moving away from the goal. (3) Value the importance of each item on 7-point scale. (4) Four scores are produced for each item: (i) State score—distance between current and ideal states; (ii) Goal score—distance between goal and ideal state; (iii) Gap score (= QoL score)—distance between current state and goal weighted by speed of improvement and rank score; (iv) Rank score—importance of each item

l‘My life is going well’; ‘My life is just right’; ‘I would like to change many things’; ‘I wish I had a different kind of life’; ‘I have a good life’; ‘I have what I want in life’; ‘My life is better than most kinds’

mNo problem; problem without emotional response; problem with emotional response

nHas problem and child feels bad; has problem and feels 'quite bad'; has problem and feels 'not so good'; has problem and feels 'fine'; has no problem. For social functioning, problem behaviour, anxiety, positive mood and liveliness, only 3-point frequency scale used with score ranging 0–2

oChildren were interviewed using two medium-sized teddy bears (one which is good at the given activity and the other bad at the activity) and asked to rate how much they liked doing what the bears are doing

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of included generic multidimensional childhood patient-reported outcome measures designed to be accompanied by preference-based value setsa

| # | Acronym: name | Reference; country | Target age (years) | Perception captured (category)b | Respondent type | Administration mode | Recall period | Domains (number, n) | Items n | Response options [scoring method] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16D: 16-Dimensional Health-Related Measure | Apajasalo [18]; Finland | 12–15 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self or interviewer | Today | Mobility; vision; hearing; breathing; sleeping; eating; speech; excretion; school and hobbies; mental function; discomfort and symptoms; depression; distress; vitality; appearance; friends (n = 16) | 16 | 5-point scale [value set available] |

| 2 | 17D | Apajasalo [67]; Finland | 8–11 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By interviewer | Today | Mobility; vision; hearing; breathing; sleeping; eating; speech; excretion; school and hobbies; mental function; discomfort and symptoms; depression; distress; vitality; appearance; friends; concentration (n = 17) | 17 | 5-point scale [value set available] |

| 3 | AHUM: Adolescent Health Utility Measure | Beusterien [78]; UK | 12–18 | No (FDH) | Child | By interviewer | Today | Self-care; pain; mobility; strenuous activities; self-image; health perceptions (n = 6) | 6 | 4- to 7-point scale [value set available] |

| 4 | AQoL-6D Adolescent: Assessment of Quality of Life, 6-Dimensional, Adolescent | Moodie [37]; Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga | 15–18 | No (FDH) | Child | By self | Past week | Physical ability; social and family relationships; mental health; coping; pain; vision, hearing and communication (n = 6) | 20 | 4- to 6-point scale [value set available] |

| 5 | CH-6D: Child Health—6 Dimensions | Kang [50]; South Korea | 7–12; 16–18 | No information | Child | By self; mobile | Not stated | Not stated (n = 6) | 6 | 3- to 4-point scale [value set planned/in development] |

| 6 | CHSCS-PS: Comprehensive Health Status Classification System—Preschool | Saigal [60]; Canada, Australia | 2–5 | No (FDH) | Observer (clinicians, parents) | By self | Past week | Vision; hearing; speech; mobility; dexterity; self-care; emotion; learning and remembering; thinking and problem solving; pain; behaviour; general health (n = 12) | 12 | 3- to 5-point scale [value set planned/in development] |

| 7 | HUI2: Health Utilities Index 2 | Torrance [75]; Canada | 8–18 | No (FDH) | Child | By self or interviewerc | General | Sensation; mobility; emotion; cognition; self-care; pain; fertility (n = 7) | 7 | 3- to 5-point scale [value set available] |

| 8 | HUI2 Informant only | Torrance [75] | 5–8 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self or interviewer | General | See HUI2 | 7 | See HUI2 |

| 9 | HUI3: Health Utilities Index 3 | Furlong [148]; Canada | 8–18 | No (FDH) | Child | By self or interviewerc | General | Vision; hearing; speech; ambulation/mobility; pain; dexterity; emotion; cognition (n = 8) | 8 | 5- to 6-point scale [value set available] |

| 10 | HUI3 Informant only | Furlong [148] | 5–8 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self or interviewer | General | See HUI3 | 8 | See HUI3 |

| 11 | CHU9D: Child Health Utility 9D | Stevens [84, 149]; UK | 7–11 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self | Today/last night | Worried; sad; annoyed; tired; pain; sleep; daily routine; school work/homework; able to join in activities (n = 9) | 9 | 5-point scale [value set available] |

| 12 | EQ-5D-Y: EuroQoL 5-Dimensional questionnaire for Youth | Wille [38]; 7 countriesd | 8–15 | No (FDH) | Child; observer | By self | Today | Mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; feeling worried/sad/unhappy; general health VAS (n = 5 + VAS) | 5 | 3-point scale + VAS [value set available] |

| 13 | EQ-5D-Y Proxy: EQ-5D-Y for informant | Gusi, Verstraete [40, 150]; Spain, South Africa | 3–7 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self (mail) or interviewer (telephone) | Today | See EQ-5D-Y | 5 | See EQ-5D-Y |

| 14 | EQ-5D-Y-5L: EQ-5D-Y, 5 levels | Kreimeier [151]; Germany, Spain, Sweden, UK | 8–15 | No (FDH) | Child | By self | Today | Mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort; feeling worried/sad/unhappy; general health VAS (n = 5 + VAS) | 5 | 5-point scale + VAS [value set planned/in development] |

| 15 | IQI: Infant health-related Quality of life Instrument | Jabrayilov [51]; UK, New Zealand, Singapore | 0–1 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; mobile | Today | Sleeping; feeding; breathing; stooling/poo; mood; skin; interaction (n = 7) | 7 | 4-point scale [value set available] |

| 16 | QWB: Quality of Well-Being scale | Kaplan [152, 153]; US | N/A | No (FDH) | Child; observer | by self or interviewer | Functional level: general, symptoms: past 3 days except today | Mobility; physical activity; social activity; symptom-problem complex (n = 4) | 61 | 2- to 4-point scale [value set available] |

| 17 | TANDI: Toddler and Infant health related quality of life instrument | Verstraete (2020b); (2020c) [39, 154]; South Africa | 0–3 | No (FDH) | Observer | By self; mail | Today | Movement; play; pain; relationships; communication; eating; general health VAS (n = 6) | 6 | 3-point scale [value set planned/in development] |

FDH functioning, disability and health, HRQoL health-related quality of life, QoL quality of life, VAS visual analogue scale, N/A Not applicable

aMeasures arranged alphabetically; family of measures (e.g. CHSCS-PS, HUI2 and HUI3) arranged together

bDenotes whether the measure items capture child respondent’s perception (i.e. his/her enjoyment, satisfaction, expectations, standards and concerns) on health, health-related aspect or position in life: ‘yes’ if more than 75% of items did; ‘no’ if less than 25% of items did; ‘some’ if between 25% and 75% of items did. ‘Yes’ implies that the measure is predominantly a QoL or HRQoL measure; ‘no’ predominantly an FDH measure; and ‘some’ a mix of QoL/HRQoL and FDH

cInterviewer-administered for age 8–12

dGermany, Spain, South Africa, Italy, Sweden, The Netherlands and the UK

Characteristics of Measure by Age Category

Age groups 5–7 and 8–11 were combined for the subsequent descriptions of measure characteristics because relatively few measures targeted these age groups. This generated three rather than four age categories for the subsequent descriptions. Overall, there were 20 measures that targeted children less than 5 years, 29 that targeted children aged 5–11 years and 24 that targeted adolescents aged 12–18 years. Thirty-seven measures covered multiple age groups. Table C in the Supplementary Information (see the electronic supplementary material) organises the included measures by the above four target age group categories.

Conceptual Basis

Figure 3 shows the number of identified PROMs by age category according to their conceptual basis. The proportion of measures designed to elicit the child’s perception of their status (i.e. QoL, HRQoL and QoL/HRQoL-FDH measures) varied between four out of 20 (20%) for the infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers category and 18 out of 24 (75%) for adolescents. Twenty of 37 (54%) measures with multi-age group coverage were designed to elicit the child’s perception of their status.

Fig. 3.

Number of identified generic multidimensional childhood PROMs by conceptual basis and age category. FDH functioning, disability and health, HRQoL health-related quality of life, PROM patient-reported outcome measure, QoL quality of life

Domain Coverage

Table 3 lists in alphabetical order the domains covered by generic multidimensional childhood PROMs stratified by age category and conceptual basis. Moreover, domains that are unique to each age category are presented in bold and underlined.

Table 3.

Domains covered by included patient-reported outcome measures by age category and conceptual basis. Domains unique to age category are highlighted in bold and underlined

| Age category | Underlying conceptual basis | Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers (age < 5)a | FDH | Accident; activities; activities needing assistance; Acute minor illness; Acute significant illness; aids/devices for functioning; anger; anxiety; arising; behaviour; bodily pain; breathing; change in health over past over; chronic illness; cognitive functioning; communication; depressive symptoms; dexterity; dressing and grooming; eating; emotion; emotional functioning; Engagement—Curiosity; Engagement—Persistence; Family cohesion; Family environment; Feeding; general behaviour; general health; general health perceptions; getting along; global health; grip; Growth and development; hearing; Hospital admission; Hygiene; Immunisation; Interaction; Learning and remembering; mobility; mood; movement; pain; parental impact—emotion; Parental impact—General health; Parental impact—Mental; parental impact—time; physical activity; physical challenges; physical functioning; Physical symptoms; play; positive affect; Psychomotor development; Psychopathological elements; reach; relationships; Responsiveness; school functioning; self-care; Self-control—Adaptability; Self-control—Self-regulation; Skin; Sleep; Sociability; Social functioning; Social relationships; Speech; Stooling; Temperaments and moods; Thinking and problem solving; total functional status; VAS general health; VAS pain; VAS wellbeing; vision; walking |

| QoL/HRQoL-FDH | Child behaviour; emotion; family; friends; physical health; school; self-esteem | |

| QoL | Activities at school and leisure; family life; global health; social life | |

| HRQoL | Anxiety; Appetite; communication; Liveliness; Lung problems; motor functioning; positive mood; Problem behaviour; Skin problems; sleeping; social functioning; Stomach problems | |

| Pre-adolescents (age 5–11)b | FDH | Able to join activities; achievement; Annoyed; appearance; breathing; cognition; comfort; concentration; Daily routine; depression; dexterity; discomfort and symptoms; distress; doing usual activities; eating; emotion; emotional functioning; excretion; feeling worried, sad or unhappy; fertility; friends; fun with friends; general health; hearing; mental function; mental health; mobility; looking after myself; moving; pain; parents listen to ideas; physical functioning; physical health; QoL; resilience; risk avoidance; sad; satisfaction; school and hobbies; school functioning; school work; self-care; sensation; Sleeping; Social functioning; speech; tired; VAS global health; vision; vitality; worried |

| QoL/HRQoL-FDH | Emotion; family; friends; mental; physical; physical health; school; self-esteem; social | |

| QoL | Activities at school and leisure; anxious-depressed; cognitive; community connectedness; emotional; family functioning; family life; family relationships; Food satisfaction; future security; general wellbeing; global health; health; leisure-time activities; life achievement; personal relationships; personal safety; physical; physical activity; physical complaints; physical handicaps; physical limitations; relation with parents; relation with peers; Relation at school; Relation with siblings; school achievements; Self-concept; Social; Social conflicts; social life; social wellbeing; standard of living; symptoms; Worry | |

| HRQoL | Achievement; Activity impairment; asthma-specific; autonomy; cognitive; cognitive functioning; comfort; energy; general health perceptions; general wellbeing; global negative emotional functioning; global positive emotional functioning; healthiness; motor functioning; pain and symptoms; physical; physical complaints; physical health; psychosocial; resilience; risk avoidance; social; social functioning; symptoms; Values; wellbeing | |

| Adolescents (age 12–18)c | FDH | Achievement; appearance; breathing; comfort; coping; depression; discomfort and symptoms; Disorders; distress; eating; emotional functioning; excretion; friends; health perceptions; mental function; mental health; Physical ability; physical functioning; resilience; risk avoidance; satisfaction; school and hobbies; school functioning; self-image; sleeping; social and family relationships; social functioning Strenuous activities; vision, hearing and communications; vitality |

| QoL/HRQoL-FDH | Bodily pain; change in health; emotion; Emotional wellbeing; external conditions; family; family activities; family cohesion; friends; general behaviour; general health perceptions; getting along; global behaviour; health; interpersonal conditions; Intimacy; Material wellbeing; mental; mental health; physical; physical functioning; physical health; Place in community; productivity; psychological conditions; role functioning—behavioural; role functioning—emotional; role functioning—physical; school; Safety; self-esteem; social | |

| QoL | Becoming; Being; Belonging; Contextual factors to QoL; Environment; family; general QoL; global QoL and health satisfaction; Independence; leisure and relationships; living environment; Opposite-sex relationship; pain; Perceptual factors to QoL; Personal competence; physical; physical appearance; psychological; psychological wellbeing; residential environment; Same-sex friends; school; self; self-esteem; Sense of self; social relationship | |

| HRQoL | Anxiety; depression; Disability; emotional feelings; energy/vitality; Family communications; friends; general health; Health habits; leisure; mental health; pain; parents; perceived health; Physical fitness; physical health; psychological wellbeing; school; school work; self-esteem; Social health; social support | |

| Multi-age group coveraged | FDH | Activities; activities needing assistance; aids/devices for functioning; ambulation; anger; anxiety; arising; asthma impact; cognition; depressive symptoms; dexterity; dressing and grooming; eating; Educational; emotion; fatigue; feeling worried/sad/unhappy; fertility; fun with friends; general health; grip; hearing; hygiene; Interpersonal functioning; lack of energy; mental health; mobility; pain; pain interference; parents listen to ideas; peer relationships; physical; physical activity; physical challenges; physical health; psychological; QoL; sad; self-care; sensation; social; Social activity; speech; symptom-problem complex; tired; total functional status; Upper extremity; usual activities; VAS general health; VAS pain; VAS wellbeing; vision; walking |

| QoL/HRQoL-FDH | Bodily pain; change in health; emotion; external conditions; family; family activities; family cohesion; friends; general behaviour; general health perception; interpersonal conditions; mental health; parental impact—emotion; parental impact—time; physical functioning; physical health; psychological conditions; role functioning—behavioural; role functioning—emotional; role functioning—physical; school; self-esteem | |

| QoL | Activities; appearance; Attainments; autonomy; chronic-generic QoL; cognitive and school performance; cognitive functioning; communication; community connectedness; Continence; depression; depressive moods and emotions; discomfort; eating; emotional; energy level; family; family functioning; feelings about yourself; Financial resources; friends; future security; general affect; general satisfaction; getting along with friends; getting along with family; Getting/buying things; getting things done; global QoL; health; Helping at home; interests and hobbies; Life achievement; Life satisfaction; living environment; love/affection; maternal acceptance; mental; mental health; mobility; mood; moods and emotions; parent relationship; parent relations and home life; parent relations and autonomy; paying attention; peer acceptance; peer relationship; personal relationships; personal safety; physical; physical activity; Physical competence; physical health; physical wellbeing; place you live at; play/free time; Psychological functioning; psychological wellbeing; school; School environment; school performance; School wellbeing; self; self-care; self-perception; sight; sleep; social and leisure times; social acceptance; Social integration; social support and peers; Spiritual; standard of living; worry | |

| HRQoL | Autonomy; cognitive functioning; global negative emotional functioning; global positive emotional functioning; motor functioning; pain and symptoms; social functioning |

FDH functioning, disability and health, HRQoL health-related quality of life, QoL quality of life, VAS visual analogue scale

aVersions for this category (see Table 1 for full names of measures): QUALIN; AUQUEI Nursery; CHAQ38 Informant only; FSIIR Infants; FSIIR Toddlers; FSIIR Pre-schoolers; ITQOL; ITQOL SF47; Kiddy-KINDL CQ; Kiddy-KINDL PQ; PedsQL GCS Toddler; PedsQL SF15 Toddler; PedsQL Infant Scales (1–12 months); PedsQL Infant Scales (13–24 months); PROMIS EC; TAPQOL; WCHMP; CHSCS-PS; IQI; TANDI

bVersions for this category: AUQUEI Primary; CHIP-CE CRF; CHIP-CE PRF; CHIP-CE PRF (short-form); CHRS; CHSCS; ExQoL; HAY; HDQ Age 6; HDQ Age 10; Healthy Pathways CRS; Healthy Pathways PRS; Kid-KINDL CQ; PedsQL GCS Young Child; PedsQL GCS Child; PedsQL SF15 Young Child; PedsQL SF15 Child; P-MYMOP; PROMIS PGH7 Informant only; PWI-SC8; QLQC; QLSI-C; QLSI-C Tablet; QoL-C; TACQOL Informant only; 17D; HUI2 Informant only; HUI3 Informant only; CHU9D

cVersions for this category: OK.ado; CHIP-AE; CHQ-CF87; CHQ-CF45; ComQOL-S5; COOP Charts; DHP-A; HDQ Age 13; HDQ Age 16; Kiddo-KINDL AQ; Nordic QoLQ; PedsQL GCS Teen; PedsQL SF15 Teen; QOLPAV; QOLQA; QOLQA-Taiwan; MSLSS-A; VSP-A; WHOQOL-BREF; YQoL-R; YQoL-S; 16D; AHUM; AQoL-6D Adolescent

dVersions for this category: ACHWM; CHAQ; CHAQ Informant only; CHAQ38; CHQ-PF50; CHQ-PF28; CQoL; FSIIR School children; FSIIR-14; GCQ; ILC; Kid- & Kiddo-KINDL PQ; KINDL CAT-SCREEN; KIDSCREEN-52; KIDSCREEN-27; KIDSCREEN-10; Kids-CAT; MCWBS; Nordic QoLQ Informant only; PQ-LES-Q; PROMIS PIB; PROMIS PIB SF; PROMIS PIB CAT; PROMIS PGH7; PWI-SC; SLSS; MSLSS; MSLSS Brief; TACQOL; TedQL; CH-6D; EQ-5D-Y; EQ-5D-Y Proxy; EQ-5D-Y-5L; HUI2; HUI3; QWB

Thirty-one domains were unique to infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers, of which 25 were unique to FDH measures and six to HRQoL measures. There were ten unique domains for pre-adolescents, 25 for adolescents and 16 for the multi-age coverage category. The unique domains were concentrated in FDH measures (19 of 25; 76%) for infants, toddlers or pre-schoolers, and in QoL measures (16 of 25; 64%) for adolescents.

Respondent/Informant Type and Other Measure Characteristics

Table 4 summarises the respondent and informant types and design features of measures by age category.

Table 4.

Frequencies of alternative characteristics of measures by target age category

| Target age category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 5 N = 20 |

Age 5–11 N = 29 |

Age 12–18 N = 24 |

Multi-age N = 37 |

Total N = 110 |

|

| Respondent and informanta type—number of measures (%) | |||||

| Designed primarily for child report | 1 (2.3) | 9 (20.5) | 18 (40.9) | 16 (36.4) | 44 (40.0) |

| Child report, aided by adult (e.g. parent) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.5) |

| Compatible with child and proxyb | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | 7 (70.0) | 10 (9.1) |

| Compatible with child and observer | 0 (0.0) | 7 (43.8) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (37.5) | 16 (14.5) |

| Compatible with proxy report onlyb | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (44.4) | 9 (8.2) |

| Compatible with observer report only | 16 (64.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (16.0) | 25 (22.7) |

| Administration mode—number of measures (%) | |||||

| Compatible with child self-report | |||||

| By self, non-electronic | 0 (0.0) | 8 (21.1) | 15 (39.5) | 15 (39.5) | 38 (50.0) |

| By self, electronic | 0 (0.0) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (63.6) | 11 (14.5) |