Abstract

Objective:

As a key member of transient receptor potential (TRP) superfamily, TRP canonical 3 (TRPC3) regulates calcium homeostasis and contributes to neuronal excitability. Ablation of TRPC3 lessens pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice, suggesting that TRPC3 inhibition might represent a novel antiseizure strategy. Among current TRPC3 inhibitors, pyrazole 3 (Pyr3) is most selective and potent. However, Pyr3 merely provides limited benefits in pilocarpine-treated mice likely due to its low metabolic stability and potential toxicity. We recently reported a modified pyrazole compound 20 (or JW-65) that has improved stability and safety. The objective of this study was to explore the effects of TRPC3 inhibition by our current lead compound JW-65 on seizure susceptibility.

Methods:

We first examined the pharmacokinetic properties including plasma half-life and brain to plasma ratio of JW-65 after systemic administration in mice. We then investigated the effects of TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 on behavioral and electrographic seizures in mice treated with pilocarpine. To ensure our findings are not model specific, we assessed the susceptibility of JW-65-treated mice to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures with phenytoin as a comparator.

Results:

JW-65 showed adequate half-life and brain penetration in mice, justifying its uses for CNS conditions. Systemic treatment with JW-65 before pilocarpine injection in mice markedly impaired the initiation of behavioral seizures. This antiseizure action was recapitulated when JW-65 was administered after pilocarpine-induced behavioral seizures were well established and was confirmed by time-locked electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring and synchronized video. Moreover, JW-65-treated mice showed substantially decreased susceptibility to PTZ-induced seizures in a dose-dependent manner.

Significance:

These results suggest that pharmacological inhibition of the TRPC3 channels by our novel compound JW-65 might represent a new antiseizure strategy engaging a previously undrugged mechanism of action. Hence, this proof-of-concept study establishes the TRPC3 as a novel feasible therapeutic target for the treatment of some forms of epilepsy.

Keywords: calcium channels, pentylenetetrazole, pilocarpine, seizure, status epilepticus, transient receptor potential channels

1. Introduction

As one of the most prevalent and debilitating neurological disorders, epilepsy affects approximately 65 million people worldwide. The disease is characterized by epileptic seizures resulting from hyperexcitability of a group of highly synchronized brain neurons 1. Over the course of the past three decades, we have witnessed remarkable scientific advances in understanding the pathophysiological processes underlying seizure initiation, escalation, and dissemination, facilitating introduction of the third-generation antiseizure drugs (ASDs) 2-4. However, there are still 30-40% of epilepsy patients who are inadequately treated, as their seizures are refractory to the current frontline medications 5, 6. Moreover, current ASDs are well known for their broad neurotoxic adverse effects, such as drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, headache, blurred vision, incoordination, depression in adults, and cognitive impairment in children, which are often unbearable and further complicate the seizure management 1. ASDs exert antiseizure effects mainly through four currently known mechanisms: (1) modulation of voltage-gated ion channels for sodium, calcium, and potassium; (2) augmentation of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission; (3) blockade of glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission; (4) modulation of neurotransmitter release 3, 4. Given that these antiseizure mechanisms might also underlie the adverse effects of current ASDs 3, and that the pharmacoresistance in epilepsy treatment is likely caused by target-site alterations 5, it is important to identify new antiseizure targets that may help to overcome these two issues. Developing new ASDs with novel mechanisms of action is also important to the combination therapies for an unignorable proportion of epilepsy patients that require treatment with two or more ASDs 3.

Calcium influx is essential to the spread of action potential, synaptic transmission, and neuronal excitability, and involves a variety of calcium-permeable ion channels including transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) subfamily channels, which have been implicated in many biological functions 7-9. Among the seven currently known TRPC members, TRPC3 is in a tight functional interaction with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors, contributing to store-operated Ca2+ entry in the CNS 10-12. In addition, the likely role of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis-produced diacyl glycerol (DAG) in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-evoked Ca2+ influx might also be mainly attributed to its direct action on the TRPC3 channels, as DAG-stimulated Ca2+ influx is largely prevented by blocking TRPC3 13, 14. Interestingly, intracerebroventricular administration of an anti-TRPC3 antibody prevents aberrant-sprouted mossy fiber collaterals in hippocampal CA3 region in mice after pilocarpine-induced SE 15. Genetic ablation of TRPC3 markedly decreases the duration and severity of behavioral seizures in pilocarpine-treated mice and reduces the overall power of SE 16. These findings suggest that pharmacological inhibition of the TRPC3 channels might represent a novel antiseizure and/or antiepileptogenic strategy. Among currently known TRPC3 inhibitors, pyrazole 3 (Pyr3) is most potent and selective 17, and thus is commonly used to study TRPC3 functions.

However, Pyr3 structure has two major limitations 13: (1) its trichloroacrylic amide may act as an alkylating group to cause toxicity; (2) the ester moiety can be hydrolyzed quickly in vivo and lead to low stability of the compound 18. Thus, its effective uses in animal seizure models were limited to intracranial injections 19, 20. A systemic low dose of Pyr3 (3 mg/kg, i.p.) that reduced status epilepticus (SE) power was not reported to phenocopy the significant reduction in behavioral seizures observed in TRPC3−/− mice after pilocarpine treatment 16. A higher systemic dose of Pyr3 was not reportedly used in preclinical models of epilepsy possibly due to the high toxicity associated with its alkylating moiety. To overcome these limitations, we previously hypothesized that incorporating the tail group in a conformationally restricted ring may diminish the alkylating toxicity, and that isosterically replacing the ester with a stable linker can improve the metabolic stability. We thus designed and synthesized a series of modified pyrazoles, represented by our current lead compound JW-65 (compound 20) 21, which displayed improved metabolic stability and safety without compromising the high potency or selectivity for TRPC3 inhibition when compared to Pyr3 21. Using this bioavailable, brain-permeable, metabolically stable, and drug-like TRPC3 inhibitor, we tested the hypothesis that pharmacological blockade of the TRPC3 channels could mitigate seizures in two most commonly used chemoconvulsant models. This proof-of-concept study also aimed to establish the TRPC3 as a novel feasible antiseizure target.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and drugs

Selective TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 was designed and synthesized in our laboratories (Figures 1A and S1), and its identity, purity, potency as well as selectivity were determined independently and blindly as we previously described 21. Compounds from different batches were compared to each other for consistency in both potency and selectivity. All chemicals for synthesis were of analytic grade as received from commercial sources without further purification. Methylscopolamine, terbutaline, pilocarpine, pentylenetetrazole (PTZ), and phenytoin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

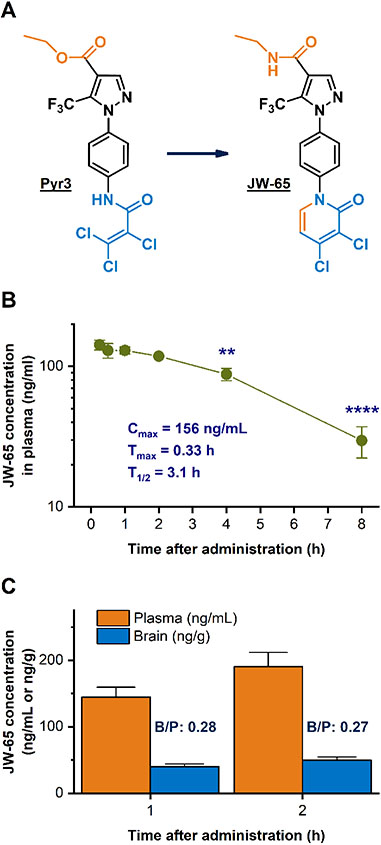

Figure 1.

JW-65 is a novel, CNS-permeable, stable, and safe inhibitor of TRPC3 channels. (A) Isosteric replacement of ester with an amide linker in the head moiety and incorporation of a conformationally restricted ring (pyridone) in the tail group of Pyr3 led to the discovery of a novel TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 (compound 20) 21, which is safer and metabolically more stable than Pyr3 without compromising its high potency and selectivity. (B) Pharmacokinetic study of JW-65 in adult male C57BL/6 mice after a single systemic dose (100 mg/kg, i.p.). The plasma concentration of compound quickly reached the maximum (156 ng/mL) about 15-30 min after injection and did not decline until 4 h after dosing (**P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test). JW-65 had a plasma half-life of 3.1 h. (C) JW-65 showed a brain to plasma ratio of ~0.3 at both 1 h and 2 h after injection. Data are shown as mean +/± SEM (N = 3 mice per time point). It is noted that the mice utilized to determine the plasma half-life of JW-65 were different from those for the evaluation of its brain penetration.

2.2. Experimental animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (the Guide) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Young adult male C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks) from Charles River Laboratories were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum before the experiments. To ensure robust and unbiased findings, the researchers who performed the animal experiments and analyzed data had no knowledge about the treatment.

2.3. Compound pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic study of TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 with systemic administration (dose: 100 mg/kg, route: i.p., formulation: 10% DMSO + 40% PEG 300 + 10% Tween 80 + 40% saline) was performed in adult male C57BL/6 mice (8-10 weeks) by WuXi AppTec. To determine the plasma half-life of the compound, blood samples were collected from the saphenous vein at seven time points after compound administration: 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h (Figure 1B and Table S1). The brain to plasma ratio of the compound was determined in a different set of mice, and blood samples were first collected at 1 h and 2 h after injection and then brain samples were collected after perfusion with saline (Figure 1C and Table S1). Brain and plasma homogenates were then extracted and analyzed for JW-65 concentrations by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The compound was below quantification limit in the plasma 24 h after administration. The plasma and brain concentrations of compound JW-65 were utilized to determine its plasma half-life and brain to plasma ratio at 1 h and 2 h after dosing.

2.4. Mouse pilocarpine model of SE

Mice were injected with methylscopolamine and terbutaline (2 mg/kg each in saline, i.p.) to minimize the unwanted effects of pilocarpine in the periphery. Thirty minutes later, pilocarpine (220 or 250 mg/kg in saline, freshly prepared, i.p.) was injected to induce seizures in mice. To determine the antiseizure effects of TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65, the compound was intraperitoneally administered to mice (100 mg/kg in 10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 10% Tween 80, and 40% saline) blindly either before pilocarpine injection (Figure 2A) or after the behavioral seizures were well established (Figure 2B). Control mice received methylscopolamine and terbutaline, followed by saline injection instead of pilocarpine. Randomization of animals was performed before the treatment with vehicle or JW-65. Behavioral seizures were classified using a modified Racine scale as we previously described 22-28: Stage 0: normal behavior – walking, exploring, sniffing, and grooming; Stage 1: immobile, staring, jumpy, and curled-up posture; Stage 2: automatisms – repetitive blinking, chewing, head bobbing, vibrissae twitching, scratching, face-washing, and “star-gazing”; Stage 3: partial body clonus, occasional myoclonic jerks, and shivering; Stage 4: whole body clonus, “corkscrew” turning & flipping, loss of posture, rearing and falling; Stage 5: SE onset – non-intermittent clonic seizure activity; stage 6: wild running, bouncing, and tonic seizures; stage 7: death.

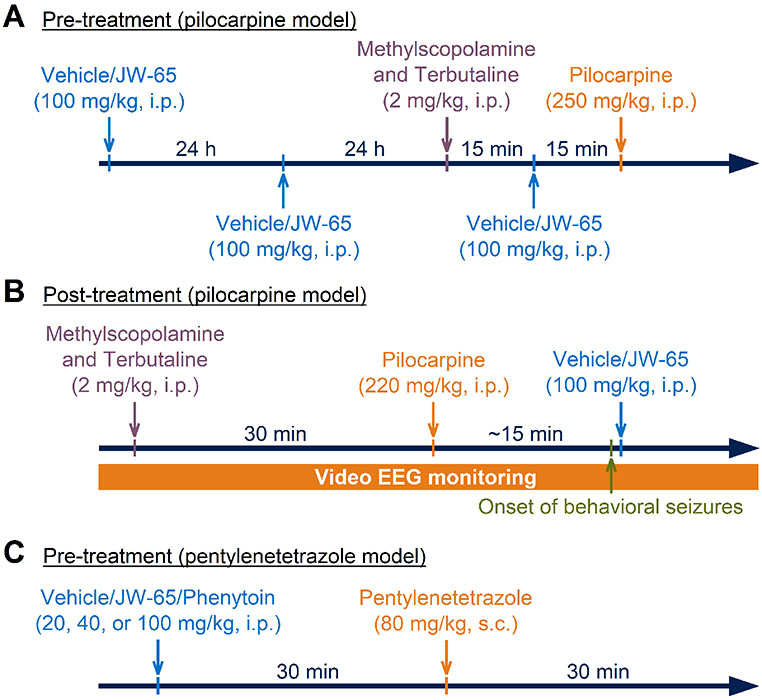

Figure 2.

Experimental procedures to examine the antiseizure effects of TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 in mouse models of chemoconvulsant-induced seizures. (A) In the pre-treatment study on pilocarpine-induced seizures, C57BL/6 mice were treated by vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 10% Tween 80, and 40% saline) or compound JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) for two consecutive days. On the experiment day, mice were treated by methylscopolamine and terbutaline (2 mg/kg each in saline, i.p.), and 15 min later by JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.). After another 15 min, mice were treated by pilocarpine (250 mg/kg in saline, i.p.) to induce SE. Behavioral seizures were observed and classified using a modified Racine scale. (B) In the post-treatment study on pilocarpine-induced seizures, mice were first treated by methylscopolamine and terbutaline (2 mg/kg each in saline, i.p.), and 30 min later by pilocarpine (220 mg/kg in saline, i.p.) to induce seizures. After behavioral seizures (stage-2) were observed, which typically occurred ~15 min after pilocarpine injection, mice were treated by JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) once. Behavioral seizures of mice were classified, and the electrographic seizures were recorded by surface electroencephalography (EEG) recording. (C) In the post-treatment study on pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures, mice were first treated by vehicle or JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) once, and 30 min later by pentylenetetrazole (~80 mg/kg, s.c.). Behavioral seizures were observed for 30 min.

2.5. Pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures

Mice were first randomized and then treated by vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 10% Tween 80, and 40% saline), JW-65 (20 or 100 mg/kg, i.p.), or phenytoin (40 mg/kg, i.p.). Thirty minutes later, mice were subcutaneously injected with pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, ~80 mg/kg) to induce seizures (Figure 2C). Mice were placed in a plexiglass chamber for observation of behavioral seizures. The latencies to the first myoclonic jerk (MJ) and the first generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) were recorded during a 30-min period of observation 29, 30. A systemic dose of 80 mg/kg for PTZ was chosen in this study, not only to ensure that most PTZ-treated animals can reach both MJ and GTCS, but also to avoid substantial mortality during the 30-min observation. This relatively high dose of PTZ would also allow rigorous evaluation on the antiseizure effects of our compound in comparison with conventional anticonvulsant phenytoin.

2.6. Electrode implantation and surface EEG recording

For intracranial surgery to implant electrodes for electroencephalography (EEG) recording, young adult C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% for induction and 2.5% for maintenance) and carefully placed on a stereotaxic frame to fix the head. Five stainless steel screws were used as electrodes or anchors, placed on the top of the dura through five small holes carefully drilled through the skull as we previously described 31: (1) two screws as electrodes were placed over cerebral cortex (coordinates from bregma: AP = −2.0 mm, ML = ±1.5 mm) with one on each brain hemisphere; (2) one screw electrode was placed over the cerebellum as the ground electrode; (3) two screws as anchors were placed over frontal cortex (coordinates from bregma: AP = +1.0 mm, ML = ±1.0 mm) with one on each brain hemisphere. The screw electrodes/anchors were then fixed to the skull using dental cement, and mice are placed on a warm pad for recovery.

2.7. EEG data acquisition and analysis

After recovery for at least five days, mice were placed in recording chambers under a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Time-locked EEG signals and synchronized video were recorded using a Grass Comet Portable EEG System powered by AS40-PLUS amplifier (Grass Technologies). The EEG signals were band-pass filtered at 1-70 Hz and sampled at 500 Hz. Evaluation of acquired EEG data was carried out by TWin 5.0.1 acquisition/review software (Grass Technologies) and DClamp 4.1 EEG analysis software, which was developed by the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA). DClamp was specifically designed for unsupervised detection of ictal-like and inter-ictal-like events in large EEG datasets and includes the algorithms for automatic detection, quantification, and analysis of seizures 32, as well as interictal spikes 33, 34. Spikes were defined as abrupt and sharp transients that have an amplitude > 2× of a 10 min baseline period prior to pilocarpine administration for seizure induction; spikes were counted blindly and verified visually as previously described 35.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism using t-test, Fisher’s exact test, or one-way/two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc multiple comparisons test as indicated in each experiment. Power analysis by G*Power 3.1 software was used to determine the required minimum sample size for each animal experiment. The Grubbs test was utilized to identify potential outliers; one was found in the PTZ study and thus excluded from the data analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were presented as mean +/± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. JW-65 is a brain-permeable TRPC3 inhibitor

As the overall best TRPC3 inhibitor that is currently available, Pyr3 has low metabolic stability, demonstrated by its short half-life (< 15 min) in mouse, rat, and human liver microsomes, and its in vivo half-life remains unknown 21. The low metabolic stability of the compound might help to explain the moderate to mild inhibition on seizures in Pyr3-treated SE mice 16, and motivated us to develop novel TRPC3 inhibitors with improved metabolic stability that might better control chemoconvulsant seizures. With several lead-optimization steps, we incorporated the trichloroacrylic amide group of Pyr3 in a conformationally-restricted ring – pyridone – and isosterically replaced the ester moiety with a more stable amide linker, leading to the discovery of a novel TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 (compound 20, Figures 1A and S1) 21. As an analog of Pyr3, JW-65 shows similar potency and selectivity on TRPC3 channels, but is metabolically much more stable than its precursor, demonstrated by its much longer half-life (> 4 h) in mouse, rat, and human liver microsomes when compared to Pyr3 21. Given the unclear in vivo half-life and brain permeability of Pyr3 that led to inconsistent doses and routes for administration found in several preclinical studies 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, we first investigated the pharmacokinetic properties of JW-65 in adult C57BL/6 mice after a systemic dose (100 mg/kg, i.p.). We found that the plasma concentration of JW-65 quickly peaked about 15-30 min following injection and this high plasma level of compound was maintained for at least 2 h afterwards (Figure 1B), leading to an adequate plasma half-life ~3 h (Table S1). The compound also showed a favorable brain to plasma ratio ~0.3 at both 1 h and 2 h after administration (Figure 1C), demonstrating its adequate and persistent brain penetration that is generally required for the treatment of most CNS conditions.

3.2. TRPC3 inhibition impairs initiation of pilocarpine-induced SE

Development of the novel TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 with much improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties allows more robust and longer inhibition of TRPC3 channels in vivo, and thus provides a better pharmacological tool to study TRPC3 than the conventional compound Pyr3. Inspired by the moderate but promising protective effects of Pyr3 against chemoconvulsant seizures as well as the largely weakened seizure activities observed in TRPC3 knock-out mice 16, we first evaluated the potential antiseizure effects of JW-65 in mice that are treated by pilocarpine. This muscarinic receptor agonist is commonly used to induce chemoconvulsant seizures in small rodents 36, 37. Adult C57BL/6 mice were pre-treated with compound JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) for two consecutive days to diminish the TRPC3 activity as much as possible (Figure 2A), aiming at a condition similar to TRPC3 ablation before pilocarpine treatment 16. On the experiment day, mice were treated by muscarinic antagonist methylscopolamine (2 mg/kg, i.p.) to antagonize the peripheral cholinergic unwanted effects of pilocarpine. Terbutaline, a β2 adrenergic receptor agonist and bronchodilator, was also administrated (2 mg/kg, i.p.) to help with respiration during the seizures. Mice were allowed to rest for about 15 min during which methylscopolamine and terbutaline were presumably mostly absorbed into the blood stream. Then mice were treated with a third dose of JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.), followed by injection with pilocarpine (250 mg/kg in saline, i.p.) another 15 min later for seizure induction (Figure 2A). Behavioral seizures were observed and classified using a modified Racine scale 23-26.

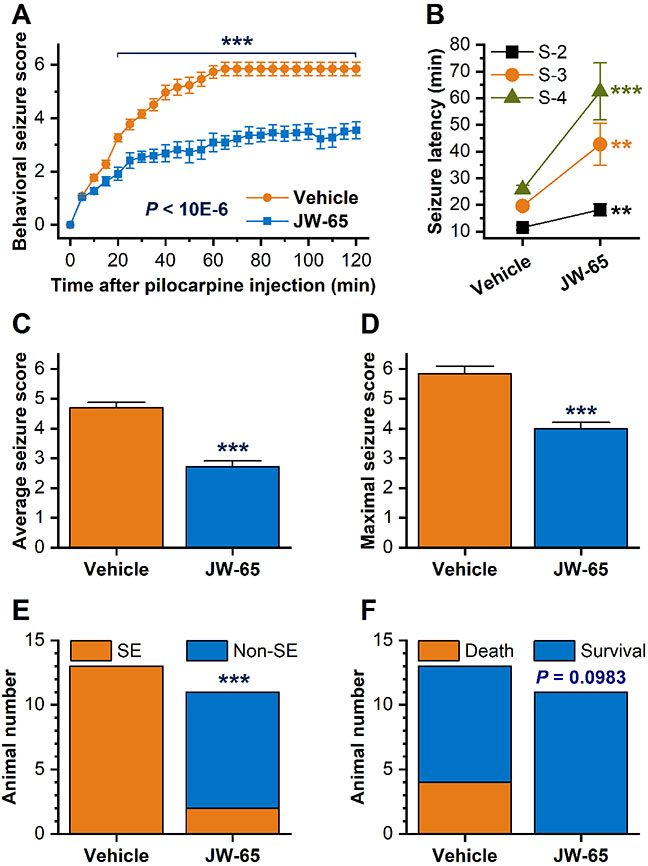

Following pilocarpine injection in mice, seizures progressed rapidly and sustained for a few hours without intervention. However, pre-treatment with JW-65 substantially decreased the overall behavioral seizure scores when compared to vehicle treatment [F(1, 550) = 764.4, P < 10E-6] (Figure 3A). The TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 also significantly increased latencies of animals to behavioral seizures [stage-2, t(22) = 3.023, P = 0.0062; stage-3, t(22) = 3.142, P = 0.0047; stage-4, t(19) = 4.355, P = 0.0003] (Figure 3B). In addition, both the average seizure scores [t(22) = 7.562, P < 0.0001, Figure 3C] and maximal seizure scores [t(22) = 5.611, P < 0.0001, Figure 3D] were decreased in JW-65-treated mice when compared to their vehicle-treated peers. All 13 vehicle-treated mice, whereas only 2 out of 11 JW-65-treated mice, experienced SE (P < 0.0001, Figure 3E). All 11 TRPC3 inhibitor-treated mice but only 9 out 13 vehicle-treated mice eventually survived pilocarpine-induced seizures (P = 0.0983, Figure 3F). These results overall suggest that pre-treatment with our TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 considerably impaired the initiation and development of pilocarpine-induced SE.

Figure 3.

Pre-treatment with JW-65 impairs the initiation and development of pilocarpine-triggered seizures. (A) Mice were pre-treated by JW-65, followed by pilocarpine injection for seizure induction. The behavioral seizure scores were tabulated every 5 min for up to 2 h and compared (N = 13 and 11 for vehicle group and JW-65 group, respectively, ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons). (B) Latencies of mice to behavioral seizures (stage-2, stage-3, and stage-4) after pilocarpine administration in mice (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, t-test). (C) The average seizure scores during the 2 hour-observation after pilocarpine injection (***P < 0.001, t-test). (D) The maximal seizure scores were compared between vehicle and JW-65 groups (***P < 0.001, t-test). (E) Number of mice that entered SE during the 2 hour-observation period (***P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). (F) Mortality of mice caused by pilocarpine-induced SE (P = 0.0983, Fisher’s exact test).

3.3. TRPC3 inhibition mitigates progression of chemoconvulsant seizures

The promising antiseizure effects by pre-treatment of JW-65 in pilocarpine SE mice encouraged us to determine the therapeutic benefits of post-treatment with the TRPC3 inhibitor after seizures are well established (Figure 2B), which is more clinically relevant than the pre-treatment strategy. Mice were first treated by methylscopolamine and terbutaline (both 2 mg/kg, i.p.) to minimize the peripheral effects of pilocarpine. Thirty minutes later, mice were systemically treated by pilocarpine (220 mg/kg, i.p.) to induce seizures (Figure 2B). After behavioral seizures (stage-2) were established in mice, which typically occurred about 15 min after pilocarpine injection, mice were randomized, treated by either vehicle or JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) once, and observed for seizure progressions.

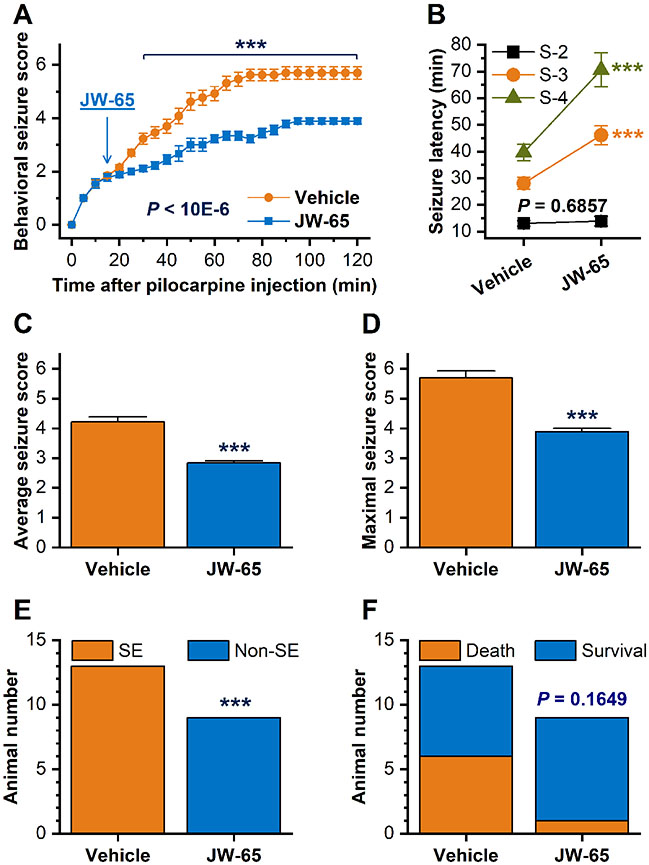

We found that the post-treatment strategy with JW-65 significantly reduced the behavioral seizures when compared to vehicle treatment [F(1, 550) = 544.9, P < 10E-6] (Figure 4A). The lack of statistically significant difference in latency to stage-2 behavioral seizures [t(20) = 0.4107, P = 0.6857] between JW-65 and vehicle groups confirmed that mice from these two experimental groups had been effectively randomized before the treatment began (Figure 4B). However, TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 drastically increased latencies of mice to stage-3 seizures [t(20) = 4.557, P = 0.0002] and stage-4 seizures [t(20) = 5.18, P < 0.0001] (Figure 4B). In line with this, both the average seizure scores [t(20) = 6.262, P < 0.0001, Figure 4C] and maximal seizure scores [t(20) = 5.985, P < 0.0001, Figure 4D] were dramatically decreased in the TRPC3 inhibitor-treated mice when compared to the vehicle-treated cohorts. All 13 vehicle-treated mice, but none of the nine JW-65-treated mice, eventually reached the long-lasting SE (P < 0.0001, Figure 4E). The animal survival rate was increased from 53.8% to 88.8% (7 out of 13 vs. 8 out of 9) by treatment with TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 (P = 0.1649, Figure 4F). The results from the post-treatment experiment together confirmed that TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 mitigated the progression of chemoconvulsant seizures in mouse pilocarpine model of SE.

Figure 4.

Post-treatment with JW-65 suppresses the progression and escalation of pilocarpine-induced SE. (A) Mice were treated by pilocarpine for seizure induction and ~15 min later by JW-65 after behavioral seizures (stage-2) were established. The behavioral seizure scores were tabulated every 5 min for up to 2 h and compared (N = 13 and 9 for vehicle and TRPC3 groups, respectively, ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons). (B) Latencies of animals to behavioral seizures (stage-2, P = 0.6857; stage-3, ***P < 0.001; stage-4, ***P < 0.001, t-test) after pilocarpine administration in mice. (C) The average seizure scores during the 2 hour-observation period after pilocarpine injection (***P < 0.001, t-test). (D) The maximal seizure scores were compared between JW-65 and vehicle-treated mice (***P < 0.001, t-test). (E) Number of mice that eventually experienced SE during the 2 hour-observation (***P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). (F) Animal mortality caused by pilocarpine-induced seizures (P = 0.1649, Fisher’s exact test).

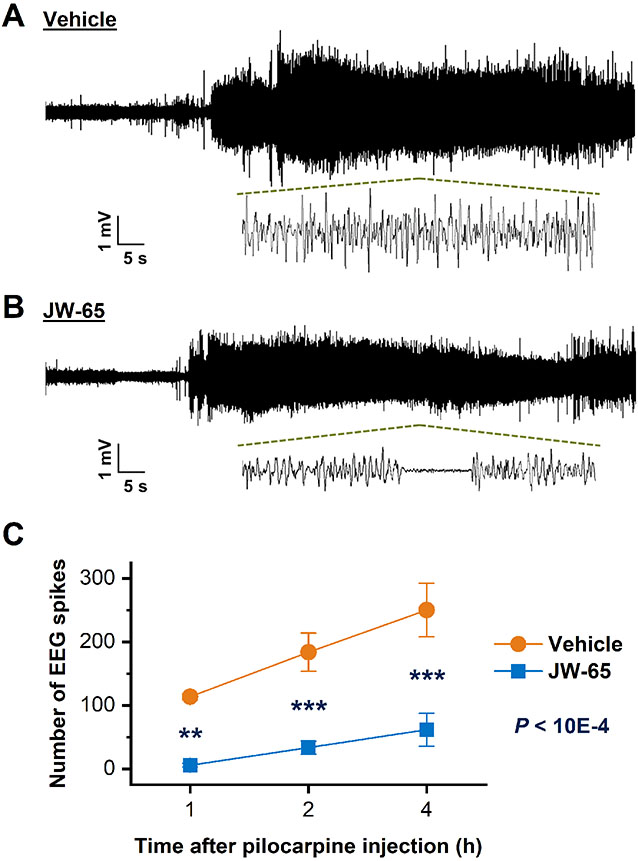

3.4. TRPC3 inhibition reduces electrographic seizures

Considering convulsive behaviors may not always correlate with electrographic seizures 38, we next examined the effects of TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 on electrographic seizures in mouse pilocarpine model of seizures using surface electroencephalography (EEG) recording. After recovery for at least five days from surgeries for electrode implantation, C57BL/6 mice were first treated by methylscopolamine and terbutaline (both 2 mg/kg, i.p.) and 30 min later by pilocarpine (220 mg/kg, i.p.) for seizure induction. After behavioral seizures (stage-2) occurred, mice were treated with vehicle or JW-65 (100 mg/kg, i.p.) (Figure 2B). Time-locked video-EEG was used to monitor the electrographic seizures in these mice (Figure 5A). EEG spikes were defined as abrupt and sharp transients that have an amplitude greater than 2× of a 10 min baseline period prior to pilocarpine administration, and the total numbers of EEG spikes were identified by DClamp 4.1 EEG analysis software and compared 35. We found that post-treatment with JW-65 substantially decreased the EEG spikes during the four-hour observation period after pilocarpine administration in a time-dependent manner [F(1, 12) = 46.77, P < 0.0001, Figure 5B]. The consistent inhibitory effects of our novel compound JW-65 on both behavioral and electrographic seizures in mouse pilocarpine model of SE together demonstrated the feasibility of targeting the TRPC3 channels as a novel antiseizure strategy.

Figure 5.

TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 reduces electrographic seizures in mouse pilocarpine model of SE. Mice were first treated by pilocarpine to induce seizures, followed by treatment with vehicle (A) or JW-65 (B). Time-locked video-EEG was used to monitor the electrographic seizures in these mice. (C) The total numbers of EEG spikes during the first hour, two hours, and four hours after pilocarpine injection were identified by DClamp 4.1 EEG analysis software and compared (N = 7, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons).

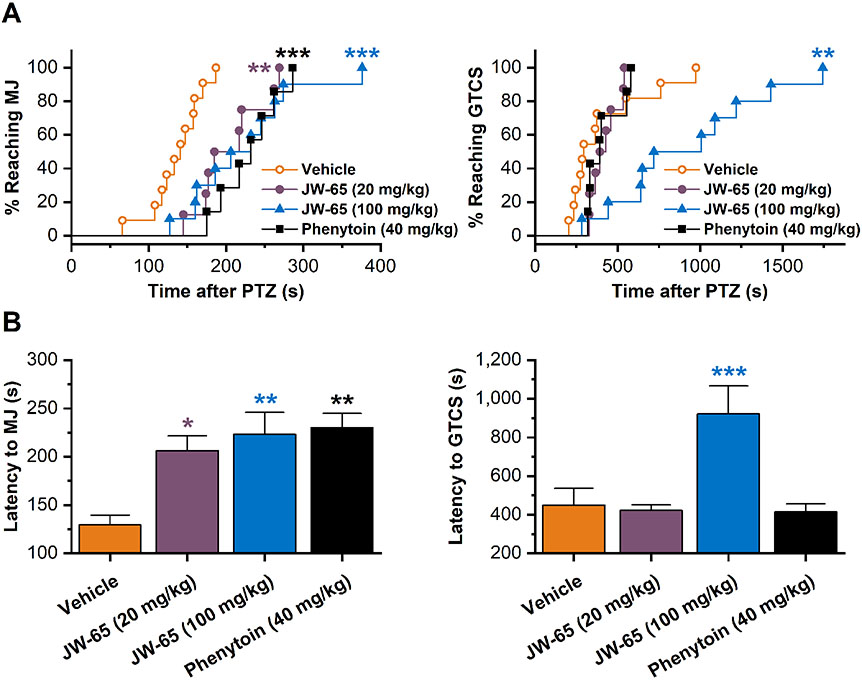

3.5. TRPC3 inhibition lessens PTZ-induced seizures

The powerful antiseizure actions of our lead compound JW-65 in pilocarpine-treated mice encouraged us to examine its effects on pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures in mice. As a GABA receptor antagonist, PTZ is another convulsant chemical commonly used to generate experimental seizures in small rodents. Adult C57BL/6 mice were first treated by vehicle or JW-65 with two doses (20 and 100 mg/kg, i.p.). Conventional anticonvulsant phenytoin (40 mg/kg, i.p.) was included in the study for positive treatment control and comparison because this ASD, with the comparable dose, has been reported to show discernible antiseizure effects in PTZ-treated mice 39, 40. Thirty minutes later, when JW-65 presumably peaked in the brain (Figure 1B,C), mice were subcutaneously injected with PTZ (~80 mg/kg) to induce seizures. Animals were placed in a plexiglass chamber, and the latencies to the first myoclonic jerk (MJ) and the first generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) were recorded during a 30-min period of observation (Figure 2C).

We found that the treatment with our TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 or the comparator phenytoin substantially reduced the percentages of mice that reached MJ when compared to treatment with vehicle only (P = 0.0014 for 20 mg/kg JW-65; P = 0.0006 for 100 mg/kg JW-65; P = 0.0001 for 40 mg/kg JW-65) (Figure 6A). However, only treatment with high-dose JW-65 (100 mg/kg) substantially delayed the PTZ-provoked mice to reach GTCS (P = 0.0029) (Figure 6A), revealing dose-dependent antiseizure effects by our TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65. In line with this, mice treated by high-dose JW-65 (100 mg/kg) showed significantly increased latencies to both the first MJ [F(3, 32) = 7.21, P = 0.0013] and GTCS [F(3, 32) = 7.49, P = 0.0009] when compared to their vehicle-treated peers (Figure 6B). Although low-dose JW-65 (20 mg/kg) and phenytoin (40 mg/kg) delayed the PTZ-treated mice to reach MJ (P = 0.0159 for 20 mg/kg JW-65; P = 0.0016 for 40 mg/kg phenytoin), they had no manifest effects on latencies to GTCS. These results together demonstrated a powerful antiseizure action from our lead compound JW-65, which is dose dependent and comparable to that of phenytoin. Considering that PTZ and pilocarpine trigger seizures via completely different mechanisms of actions, it is unlikely the antiseizure effects of our lead compound JW-65 are model specific.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of TRPC3 channels reduces susceptibility of animals to PTZ-induced seizures. Adult C57BL/6 mice were first treated by vehicle, TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 (20, or 100 mg/kg, i.p.), and 30 minutes later by pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, ~80 mg/kg, s.c.) for the induction of seizures. Conventional anticonvulsant phenytoin (40 mg/kg, i.p.) was used as a comparator in the same study. (A) Percentages of mice reaching myoclonic jerk (MJ, Left) and generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS, Right) were compared between vehicle and drug-treated mice (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, Mantel-Cox log-rank test). (B) Latencies to the first MJ (Left) and first GTCS (Right) were compared (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test). Data are shown as mean + SEM (N = 11, 8, 10, and 7 for vehicle group, 20 mg/kg JW-65 group, 100 mg/kg JW-65 group, and 40 mg/kg phenytoin group, respectively).

4. Discussion

In this study, we reported a novel small-molecule compound JW-65 as a selective TRPC3 channel inhibitor that showed adequate brain penetration and favorable CNS half-life after systemic administration in mice. Utilizing a mouse pilocarpine model of SE, we first found that inhibition of TRPC3 channels by JW-65 before pilocarpine injection in mice significantly reduced the seizure severity, elongated the seizure latencies, and decreased the number of animals that entered behavioral SE, suggesting a role of TRPC3 channels in seizure initiation. We then revealed that TRPC3 inhibition suppressed the seizure escalation when JW-65 was administered after pilocarpine-induced behavioral seizures were established in mice. Finally, we showed that the systemic treatment with JW-65 after the induction of pilocarpine-triggered seizures in mice considerably decreased EEG spike events. Importantly, the antiseizure effects in pilocarpine model were fully recapitulated in mice treated by PTZ, ruling out any model-specific actions by our lead compound. These findings demonstrate that the pharmacological inhibition of the TRPC3 channels by our novel compounds such as JW-65 might represent a new antiseizure strategy through an unprecedented mechanism of action.

Many ASDs exert their antiseizure effects dominantly via modulating various voltage-gated cation channels (Na+, Ca2+, and K+), which are activated by nearby changes in membrane potential and regulate the electrical excitability of neurons 3, 4. Ethosuximide, a first-line medication that is commonly used to treat absence seizures, is thought to lower neuronal excitability mainly through blocking the T-type calcium channels, which are low voltage-activated calcium channels that are important for the repetitive firing of action potentials. To date, no ASD has been reported to act on any TRPC cation channels, which are dominantly permeable to calcium when they are activated either by phospholipase C (PLC) or DAG 17. Among the seven currently known TRPC subfamily members, TRPC3 can be enhanced by seizures and has long been implicated in epilepsy 15, 41. The genetic ablation of TRPC3 channels markedly decreased the severity and duration of behavioral seizures in pilocarpine-treated mice and reduced the overall power of SE 16, suggesting the involvement of TRPC3 in seizure development and escalation. Likewise, results in the present study showed that the TRPC3 inhibition by our novel compound JW-65 afforded robust and long-lasting antiseizure effects (Figures 3-6). The consistent findings from studies using both genetic and pharmacological approaches validated each other and reinforced the feasibility of targeting a specific subtype of TRP channels to control convulsive seizures, demonstrating an emerging antiseizure mechanism that has not been found in any current ASDs to date 3, 42.

The genetic ablation of TRPC3 channels 16 and treatment with our TRPC3 inhibitor JW-65 (Figures 3-5) showed significant antiseizure effects in pilocarpine-treated mice at very similar levels. However, it should be noted that neither TRPC3 deficiency nor pharmacological inhibition of TRPC3 by JW-65 completely suppressed the behavioral seizures induced by pilocarpine (Figures 3 and 4), nor were they able to fully terminate the electrographic SE (Figure 5) 16, suggestive of other epileptogenic mechanisms that might be involved in this chemoconvulsant model. In the future, it is important to evaluate the combined antiseizure effects of JW-65 together with current first-line medications for SE such as benzodiazepines, which enhance GABA-mediated inhibition 3. This is of utmost significance to a non-negligible proportion of epilepsy patients who require polytherapy with two or more drugs, although seizure control by monotherapy is satisfactory in about half cases of epilepsy 43. Combining drugs with different mechanisms of antiseizure action is generally believed to be preferable, as there is increasing evidence that the rational polytherapy may also provide reasonable strategies to manage pharmacoresistant seizures 6.

It should also be noted that all previous studies on pathogenic roles of TRPC3 channels in chemoconvulsant seizures utilized either mouse or rat pilocarpine models of SE 15, 16, 19. Pilocarpine is a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, and its proconvulsant effect is likely derived from its capability to activate the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtype M1 44. The M1 receptor is predominantly coupled to Gq, and thus its activation by pilocarpine leads to the PIP2 hydrolysis to PLC and DAG, which in turn can activate the TRPC3 channels 17. In addition, pilocarpine may act on the M3 receptor subtype which is also coupled to Gq for the regulation of Ca2+ mobilization 45. It was recently reported that TRPC3 channels expressed by the cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to the inverse hemodynamic response during pilocarpine-induced SE in mice, which is a critical factor in seizure progression 46. Given that JW-65 also decreased seizures induced by PTZ, which is a GABA receptor antagonist and generates seizures via a distinct mechanism of action 36, 47, it is unlikely that TRPC3 channels promote seizures through a synergistical action with pilocarpine. Although it is possible that compound JW-65, like a number of current ASDs 3, might have more than one mechanism of action, the acute antiseizure effects of TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 in mice treated by pilocarpine or PTZ rule out the possibility that our findings are model specific.

TRPC3 is abundantly expressed in neocortex and hippocampus, where it colocalizes with BDNF and tropomyosin-related kinase receptor B (TrkB) 48, and regulates BDNF/TrkB-mediated dendritic remodeling in pyramidal neurons 14. Furthermore, the neuronal activity-dependent release of BDNF from mossy fibers and the subsequent TrkB receptor activation in the hippocampus are necessary and sufficient for the TRPC3-mediated membrane current, intracellular Ca2+ increase, and modulation of the excitatory synaptic strength at mossy fiber-CA3 synapses 49. Similarly to seizure-induced BDNF and TrkB, TRPC3 expression is elevated in epileptic foci excised from patients with intractable epilepsy 15, as well as in hippocampal neurons of rats and mice following pilocarpine-induced SE 15, 19. Given the increasingly recognized contribution of excessive BDNF/TrkB activity to the development of spontaneous seizures 26, 50, the close regulation of TRPC3-mediated Ca2+ influx by BDNF/TrkB in dendritic remodeling and excitability of hippocampal neurons, and their paralleled temporal and spatial expression in the epileptic brain, it is highly likely that TRPC3 might be involved in epileptogenesis. Thus, future efforts should be directed to evaluating longer-term effects of our lead compound JW-65 on seizure recurrence after SE by time-locked video-EEG recording and epilepsy-associated behavioral deficits. Such proof-of-concept studies will help to determine the feasibility of TRPC3 inhibition as a novel strategy to prevent the development of acquired epilepsy after precipitating events, such as de novo SE and traumatic brain injury 50, and/or to provide disease modification via reducing seizure burden and concomitant comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

JW-65 is a novel selective TRPC3 inhibitor with adequate in vivo half-life and brain penetration.

TRPC3 inhibition by JW-65 substantially impaired the initiation of pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice.

Treatment with JW-65 after seizures were established mitigated the progression of behavioral and electrographic seizures.

The TRPC3 inhibitor-treated mice manifested considerably reduced susceptibility to PTZ-triggered seizures.

The antiseizure action of JW-65 is dose dependent and comparable to that of conventional anticonvulsant phenytoin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grants R01NS100947 (J.J.), R21NS109687 (J.J.), and R61NS124923 (J.J. and W.L.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to disclose. The authors confirm that they have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

References

- 1.Devinsky O, Vezzani A, O'Brien TJ, Jette N, Scheffer IE, de Curtis M, et al. Epilepsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvill GL, Dulla CG, Lowenstein DH, Brooks-Kayal AR. The path from scientific discovery to cures for epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2020;167:107702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sills GJ, Rogawski MA. Mechanisms of action of currently used antiseizure drugs. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Löscher W, Klein P. The feast and famine: Epilepsy treatment and treatment gaps in early 21st century. Neuropharmacology. 2020;170:108055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janmohamed M, Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Pharmacoresistance - Epidemiology, mechanisms, and impact on epilepsy treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loscher W, Potschka H, Sisodiya SM, Vezzani A. Drug Resistance in Epilepsy: Clinical Impact, Potential Mechanisms, and New Innovative Treatment Options. Pharmacol Rev. 2020;72:606–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vazquez G, Wedel BJ, Aziz O, Trebak M, Putney JW Jr. The mammalian TRPC cation channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1742:21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng KT, Ong HL, Liu X, Ambudkar IS. Contribution and regulation of TRPC channels in store-operated Ca2+ entry. Curr Top Membr. 2013;71:149–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Store-Operated Calcium Channels. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1383–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiselyov K, Xu X, Mozhayeva G, Kuo T, Pessah I, Mignery G, et al. Functional interaction between InsP3 receptors and store-operated Htrp3 channels. Nature. 1998;396:478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xi Q, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Chapman KE, Waters CM, Hassid A, et al. IP3 constricts cerebral arteries via IP3 receptor-mediated TRPC3 channel activation and independently of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Circ Res. 2008;102:1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, Wong AC, Power JM, Tadros SF, Klugmann M, Moorhouse AJ, et al. Alternative splicing of the TRPC3 ion channel calmodulin/IP3 receptor-binding domain in the hindbrain enhances cation flux. J Neurosci. 2012;32:11414–11423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiyonaka S, Kato K, Nishida M, Mio K, Numaga T, Sawaguchi Y, et al. Selective and direct inhibition of TRPC3 channels underlies biological activities of a pyrazole compound. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5400–5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amaral MD, Pozzo-Miller L. TRPC3 channels are necessary for brain-derived neurotrophic factor to activate a nonselective cationic current and to induce dendritic spine formation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5179–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng C, Zhou P, Jiang T, Yuan C, Ma Y, Feng L, et al. Upregulation and Diverse Roles of TRPC3 and TRPC6 in Synaptic Reorganization of the Mossy Fiber Pathway in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:562–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelan KD, Shwe UT, Cozart MA, Wu H, Mock MM, Abramowitz J, et al. TRPC3 channels play a critical role in the theta component of pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice. Epilepsia. 2017;58:247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Cheng X, Tian J, Xiao Y, Tian T, Xu F, et al. TRPC channels: Structure, function, regulation and recent advances in small molecular probes. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;209:107497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagimori M, Murakami T, Shimizu K, Nishida M, Ohshima T, Mukai T. Synthesis of radioiodinated probes to evaluate the biodistribution of a potent TRPC3 inhibitor. MedChemComm. 2016;7:1003–1006. 10.1039/C6MD00023A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DS, Ryu HJ, Kim JE, Kang TC. The reverse roles of transient receptor potential canonical channel-3 and −6 in neuronal death following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2013;33:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun D, Ma H, Ma J, Wang J, Deng X, Hu C, et al. Canonical Transient Receptor Potential Channel 3 Contributes to Febrile Seizure Inducing Neuronal Cell Death and Neuroinflammation. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2018;38:1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S, Romero LO, Deng S, Wang J, Li Y, Yang L, et al. Discovery of a Highly Selective and Potent TRPC3 Inhibitor with High Metabolic Stability and Low Toxicity. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2021;12:572–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J, Ganesh T, Du Y, Quan Y, Serrano G, Qui M, et al. Small molecule antagonist reveals seizure-induced mediation of neuronal injury by prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3149–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang J, Yang MS, Quan Y, Gueorguieva P, Ganesh T, Dingledine R. Therapeutic window for cyclooxygenase-2 related anti-inflammatory therapy after status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;76:126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Y, Kemper T, Qiu J, Jiang J. Defining the therapeutic time window for suppressing the inflammatory prostaglandin E2 signaling after status epilepticus. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16:123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, Jiang J. COX-2/PGE2 axis regulates hippocampal BDNF/TrkB signaling via EP2 receptor after prolonged seizures. Epilepsia Open. 2020;5:418–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagib MM, Yu Y, Jiang J. Targeting prostaglandin receptor EP2 for adjunctive treatment of status epilepticus. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;209:107504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Y, Li L, Nguyen DT, Mustafa SM, Moore BM, Jiang J. Inverse Agonism of Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2 Confers Anti-inflammatory and Neuroprotective Effects Following Status Epilepticus. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;57:2830–2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro L, Wong JC, Escayg A. Reduced cannabinoid 2 receptor activity increases susceptibility to induced seizures in mice. Epilepsia. 2019;60:2359–2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ping X, Chai Z, Wang W, Ma C, White FA, Jin X. Blocking receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) or toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prevents posttraumatic epileptogenesis in mice. Epilepsia. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang J, Quan Y, Ganesh T, Pouliot WA, Dudek FE, Dingledine R. Inhibition of the prostaglandin receptor EP2 following status epilepticus reduces delayed mortality and brain inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3591–3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White AM, Williams PA, Ferraro DJ, Clark S, Kadam SD, Dudek FE, et al. Efficient unsupervised algorithms for the detection of seizures in continuous EEG recordings from rats after brain injury. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;152:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White A, Williams PA, Hellier JL, Clark S, Dudek FE, Staley KJ. EEG spike activity precedes epilepsy after kainate-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2010;51:371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen J, Berdichevsky Y, Swiercz W, Sabolek H, Staley KJ. Interictal spikes precede ictal discharges in an organotypic hippocampal slice culture model of epileptogenesis. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;27:418–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rojas A, Ganesh T, Manji Z, O'Neill T, Dingledine R. Inhibition of the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP2 prevents status epilepticus-induced deficits in the novel object recognition task in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2016;110:419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Löscher W Animal Models of Seizures and Epilepsy: Past, Present, and Future Role for the Discovery of Antiseizure Drugs. Neurochem Res. 2017;42:1873–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitkänen A, Buckmaster P, Galanopoulou AS, Moshé SL. Models of seizures and epilepsy: Academic Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelan KD, Shwe UT, Williams DK, Greenfield LJ, Zheng F. Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice: A comparison of spectral analysis of electroencephalogram and behavioral grading using the Racine scale. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandhane SN, Aavula K, Rajamannar T. Timed pentylenetetrazol infusion test: a comparative analysis with s.c.PTZ and MES models of anticonvulsant screening in mice. Seizure. 2007;16:636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akula KK, Dhir A, Kulkarni SK. Effect of various antiepileptic drugs in a pentylenetetrazol-induced seizure model in mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2009;31:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou FW, Roper SN. TRPC3 mediates hyperexcitability and epileptiform activity in immature cortex and experimental cortical dysplasia. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:1227–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porter RJ, Dhir A, Macdonald RL, Rogawski MA. Chapter 39 - Mechanisms of action of antiseizure drugs. In: Stefan H, Theodore WH, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology: Elsevier; 2012. p. 663–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Combination Therapy in Epilepsy. Drugs. 2006;66:1817–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bymaster FP, Carter PA, Yamada M, Gomeza J, Wess J, Hamilton SE, et al. Role of specific muscarinic receptor subtypes in cholinergic parasympathomimetic responses, in vivo phosphoinositide hydrolysis, and pilocarpine-induced seizure activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1403–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pronin AN, Wang Q, Slepak VZ. Teaching an Old Drug New Tricks: Agonism, Antagonism, and Biased Signaling of Pilocarpine through M3 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2017;92:601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cozart MA, Phelan KD, Wu H, Mu S, Birnbaumer L, Rusch NJ, et al. Vascular smooth muscle TRPC3 channels facilitate the inverse hemodynamic response during status epilepticus. Sci Rep. 2020;10:812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buckmaster PS. Laboratory animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Comp Med. 2004;54:473–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li HS, Xu XZ, Montell C. Activation of a TRPC3-dependent cation current through the neurotrophin BDNF. Neuron. 1999;24:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, Calfa G, Inoue T, Amaral MD, Pozzo-Miller L. Activity-dependent release of endogenous BDNF from mossy fibers evokes a TRPC3 current and Ca2+ elevations in CA3 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:2846–2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin TW, Harward SC, Huang YZ, McNamara JO. Targeting BDNF/TrkB pathways for preventing or suppressing epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2020;167:107734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.