Abstract

The gut microbiome includes a series of microorganism genomes, such as bacteriome, virome, mycobiome, etc. The gut microbiota is critically involved in intestine immunity and diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer (CRC); however, the underlying mechanism remains incompletely understood. Clarifying the relationship between microbiota and inflammation may profoundly improve our understanding of etiology, disease progression, patient management, and the development of prevention and treatment. In this review, we discuss the latest studies of the influence of enteric viruses (i.e., commensal viruses, pathogenic viruses, and bacteriophages) in the initiation, progression, and complication of colitis and colorectal cancer, and their potential for novel preventative approaches and therapeutic application. We explore the interplay between gut viruses and host immune systems for its effects on the severity of inflammatory diseases and cancer, including both direct and indirect interactions between enteric viruses with other microbes and microbial products. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms of the virome’s roles in gut inflammatory response have been explained to infer potential therapeutic targets with examples in specific clinical trials. Given that very limited literature has thus far discussed these various topics with the gut virome, we believe these extensive analyses may provide insight into the understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of IBD and CRC, which could help add the design of improved therapies for these important human diseases.

Keywords: Virome, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, bacteriophage, oncolytic virus

1. Introduction

According to GLOBOCAN 2020 released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in 2020 (10% incidence rate) and the second leading cause of cancer death (9.4% mortality) in the world [1]. Previous studies have shown that chronic inflammation is related to the etiology and pathogenesis of CRC, termed colitis-associated CRC (CAC) [2]. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), dramatically increases the risk of CAC [3, 4]. For instance, UC patients have a 2.4-fold increased risk of CAC occurrence [5]. CD patients have similar CAC incidence but at a younger age than the healthy population [6]. Although the molecular mechanisms of CRC remain largely unknown, one possibility is related to an aggravated immune response of genetically susceptible individuals to the gut microbiota [7, 8]. In return, the microbiota may also markedly impact the host defense and inflammatory response to shape IBD and CRC development and progression.

The gut microbiota represents a complex ecosystem and plays a vital role in human health and the pathogenesis of multiple diseases. In recent decades, trillions of bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites, and archaea have been identified with advances in high-throughput, next-generation sequencing technology and bioinformatics. Bacteria (Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancers [9]) and viruses (hepatitis B and C viruses for liver cancers and human papillomavirus for cervical cancer [10, 11]) have been found to strongly affect cancer genesis (tumorigenesis), progression, and treatment. Colitis and cancer microbiome studies have focused almost exclusively on bacterial members’ genomes [12, 13]. At present, only 11 out of the estimated 1012 distinct microbial species are considered human carcinogens [14, 15]. Increasing evidence suggests that the existence and quantity alterations of certain microbes alone are not enough to cause cancer, but they can serve as the second hit to promote inflammation and carcinogenesis caused by pathogenic bacterial infections, dysbiosis, and genetic defects in host immune regulation [16]. Large-scale clinical trials are currently testing the impact of the microbiota on cancer care, including diagnosis, dietary modification, and intratumoral injection of engineered bacteria [17].

Decades of searches have identified only a few viruses that can directly cause cancer, but many seem to have a complicated impact on the host’s immune system. The involvement of viral infection in IBD or CRC is increasingly being recognized [18–20]. CRC progresses in a stepwise process. Disturbances of viral homeostasis may trigger or facilitate inflammatory diseases (such as IBD), promote dysplasia, and ultimately lead to cancers with severe symptoms and high mortality [18, 19, 21]. It has been shown that viruses are directly involved in inflammation and tumorigenesis because of their ability to infect human cells and mutate [19, 22, 23]. In addition, the virus could act indirectly by regulating the stability and composition of bacterial communities [24, 25]. Thus, viruses are presumed to be potential modular biotherapeutics. Therefore, further understanding of how viruses impact IBD and CRC has great potential for early detection and prevention of progression beyond early cancer stages and significantly facilitates therapeutics development.

Here, we review aspects of the current essential knowledge that link the virus communities to inflammatory responses as well as the initiation and progression of colitis and CRC. We summarize the composition and direct function of mucosal virus in health and disease (e.g., colitis and CRC). Moreover, we discuss the viruses’ indirect role in impacting colitis and cancer by modulating the associated bacterial community. Finally, we try to fill the gaps in knowledge and attempt to point out potential future directions.

2. Distribution and abundance of viruses in the human gut

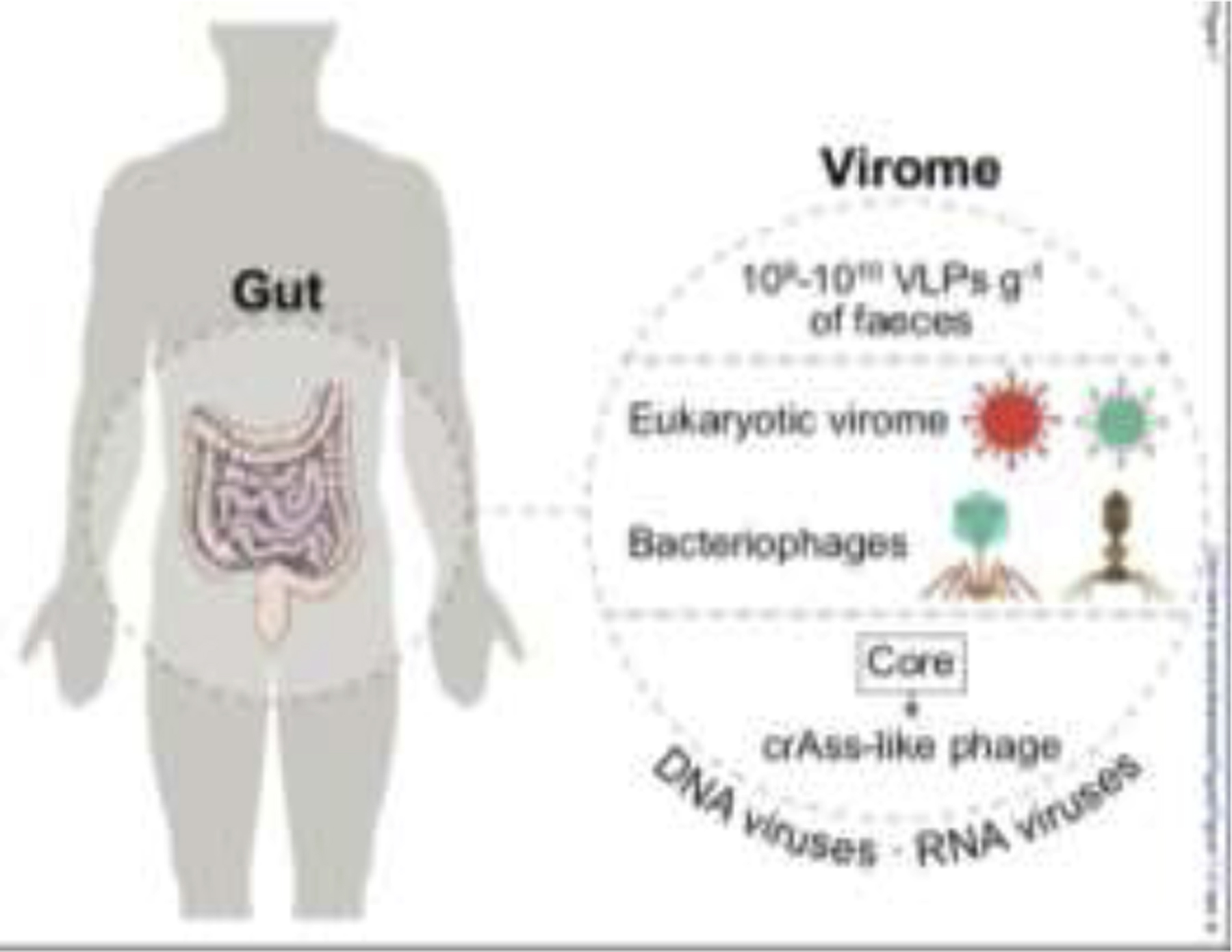

The human gut virome contains genomes of all DNA and RNA viruses naturally present in the intestine, including bacteriophages, eukaryotic viruses, archaeal viruses, and endogenous retroviruses (Figure 1). Previous research mainly focused on bacterial (bacteriophages) and eukaryotic viruses. Apart from the above, other components of the gut virome have not been studied in-depth due to limited understanding of their role in humans and a relatively small virus database.

Figure 1.

Virus distribution in the human gut. The human virome contains DNA and RNA types. Human feces contain 109-1010 virus-like particles (VLPs) per gram gross weight. The main components of virome are eukaryotic, bacterial (bacteriophage, or phage), archaeal viruses, and endogenous retroviruses. The core phage community, including crass-like phage, is the most common human gut phage. The illustration was created by adapting SMART (https://smart.servier.com) and Vecteezy (vecteezy.com) templates.

Bacteriophages (phages) are the most abundant type of bacterial viruses, which can influence homeostasis through their immunomodulatory and bactericidal effect against bacterial pathogens living in the gut [26]. The human gut virome, isolated from a single healthy individual [27], was first published in 2003 with at least 109-1010 virus-like particles (VLPs) per gram (Figure 1). The gut virome includes almost 1015 phages which are 10 times more than bacterial cells and 100 times more than human cells [28, 29]. The commensal viruses dominated by double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) phages Caudovirales and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) phages Microviridae [30] are highly specific, diverse, and stable. However, the majority of these phages remain unclassified [31]. The core phage community, including crAss-like phage, is the most abundant and widespread virus in the human gut (20–50% of individuals) [32, 33]. The composition of crAss-like phage in Western society shows a dramatic difference compared to African populations [34]. In addition, a distinct prevalent phage taxon (LAK phages) has recently been described in individuals from the region of Laksam in Bangladesh and Tanzania [35]. Since the commensal viruses are involved in host immunity education and maturation [36], a dysbiosis of these viruses might lead to IBD [24, 37] and cancer [38, 39], as we will discuss later in this review.

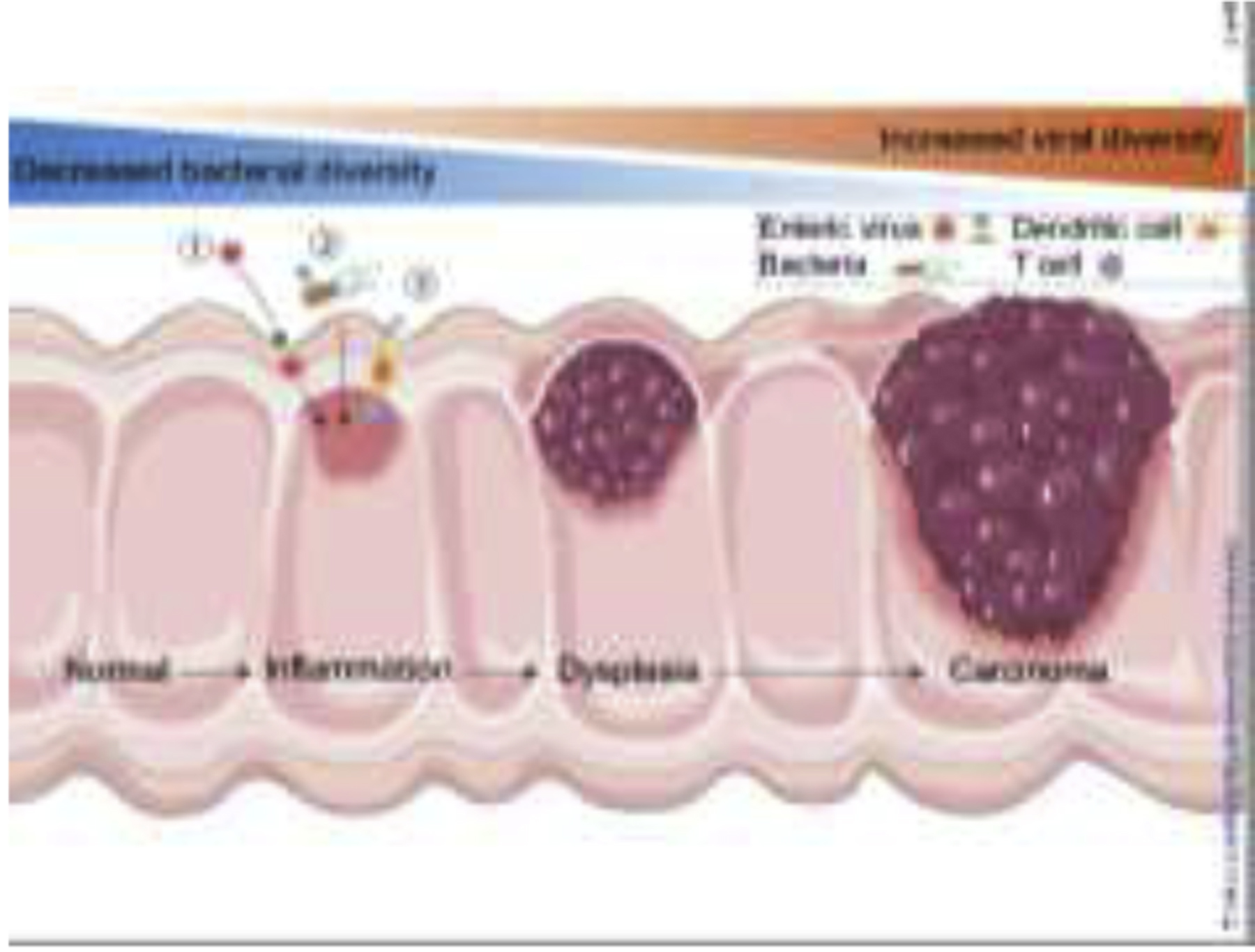

3. Viruses that are strongly related to intestinal inflammation and cancer

A variety of enteric viruses might infect humans, including retroviruses, noroviruses, rotaviruses, adenoviruses, and herpesviruses [28]. For example, norovirus is the leading cause of food-borne gastroenteritis worldwide [40]. Murine norovirus (MNoV) establishes lifelong intestinal infection in mice, and asymptomatic individuals may carry noroviruses for a long time without apparent illness [41]. Enteric viral infection may lead to pathophysiological processes, ranging from asymptomatic to moderate and severe acute or severe chronic disease, possibly resulting in colitis and cancer (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Host-virome interactions in intestinal inflammation and cancer. The enteric virome richness increases with the severity of IBD and CRC patients, while bacterial diversity and richness decrease, reflecting a reverse correlation of disease with the bacterial and viral microbiome. Induction of intestinal inflammation or direct genotoxic activity is the main mechanism underlying microbiome-induced intestinal carcinogenesis. Viruses can promote CRC in the following ways: ① directly infect the intestine, ② indirectly affect the host through bacteria, and ③ interact with the host’s immune system and induce immune responses. The illustration was created by adapting SMART (https://smart.servier.com) and Vecteezy (vecteezy.com) templates.

Over the last two decades, along with advances in viral metagenomics, the arena of research between virus and intestinal inflammation and cancer has progressed from detection of the presence of viral particles to the interaction and the virus-driven molecular mechanisms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of viruses with intestinal inflammation and cancer

| Author, Year | Virus | Disease | Sample origin | Sample size | Biospecimen type | Observations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norman et al, 2015 | Caudovirales | CD, UC | UK, USA | 72 | Feces | CD and UC patients exhibit a significant expansion of Caudovirales compared with Microviridae. | [19] |

| Wagner et al, 2013 | Caudovirales | CD | Australia | 21 | Biopsy specimens, gut wash samples | Increased abundance of Caudovirales in ileum biopsies and gut wash samples of pediatric CD patients. | [22] |

| Wang et al, 2015 | Herpesviridae | CD, UC | Canada | 10 | Biopsy specimens | Increased expression of human endogenous viral sequences in patients with herpesviridae sequences. | [42] |

| Ungaro et al, 2019 | Hepadnaviridae, Hepeviridae | CD, UC | USA | 359 | Biopsy specimens | Higher levels of eukaryotic Hepadnaviridae transcripts in UC patients; increased abundance of Hepeviridae in CD patients. | [43] |

| Cornuault et al, 2018 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii phage | CD, UC | UK, USA | 171 | Feces | F. prausnitzii phages are more prevalent or abundant in the fecal samples of IBD patients compared to healthy controls. | [44] |

| Damin et al, 2007 | HPV | CRC | Brazil | 72 | Biopsy specimens | HPV is present in the rectum and colon of most CRC patients. | [47] |

| Burnett-Hartman et al, 2013 | HPV | CRC | USA | 555 | Biopsy specimens | Very low prevalence of HPV-16 and −18 among CRC samples. | [49] |

| Gornick et al, 2010 | HPV | CRC | USA, Israel, Spain | 309 | Biopsy specimens | No association of HPV with CRC. | [50] |

| Chen et al, 2012 | CMV | CRC | Taiwan (China) | 163 | Biopsy specimens | Human CMV preferentially infects CRC lesions compared to normal healthy tissue. | [52] |

| Dimberg et al, 2013 | CMV | CRC | Sweden, Vietnam | 202 | Biopsy specimens | Human CMV DNA rate was significantly higher in cancerous tissue compared to paired normal tissue. | [53] |

| Chen et al, 2014 | CMV | CRC | Taiwan (China) | 95 | Biopsy specimens | Human CMV is associated with a worse outcome of elderly CRC patients. | [54] |

| Chen et al, 2016 | CMV | CRC | Taiwan (China) | 89 | Biopsy specimens | Human CMV may influence the outcome of CRC in an age-dependent manner. | [55] |

| Chen et al, 2015 | CMV | CRC | USA et al1 | 230 | Biopsy specimens | Human CMV genetic polymorphisms in CRC tumor tissue are associated with different clinical outcomes. | [56] |

| Harkins et al, 2002 | CMV | CRC | USA | 29 | Biopsy specimens | Association between human CMV and colon neoplasia. | [59] |

| Jung et al, 2008 | JCV | CRC | USA | 74 | Biopsy specimens | JCV T-Antigen is specifically expressed in the early stage of CRC. | [61] |

| Shavaleh et al, 2020 | JCV | CRC | Tunisia et al2 | 2,576 | Biopsy specimens | As an oncogene virus, JCV could increase the odds of CRC. | [62] |

| Campello et al, 2010 | JCV | CRC | Italy | 185 | Biopsy specimens, blood and urine samples | JCV is not detected either in normal or pathological tissues. | [63] |

| Gock et al, 2020 | JCV | CRC | Germany | 60 | Biopsy specimens, gDNA, cDNA | No direct correlation between tumorigenesis and viral load. | [64] |

| Goel et al. 2006 | JCV | CRC | USA | 100 | Biopsy specimens | Significant associations between JCV T-antigen and chromosomal instability in CRC. | [65] |

| Coelho et al, 2013 | JCV | CRC | Portugal | 200 | Biopsy specimens | JCV may be associated with tumor suppressor genes (i.e., p53) polymorphisms. | [66] |

| Enam et al, 2002 | JCV | CRC | USA, Mexico | 27 | Biopsy specimens | Possible association of JCV with CRC. | [67] |

| Destri et al, 2013 | HBV, HCV | CRC | Italy | 488 | Biopsy specimens | Hepatitis virus-infected CRC patients had better 5-year disease-free survival and a lower incidence of metachronous liver metastases. | [68] |

| Su et al, 2020 | HBV | CRC | Taiwan (China) | 69,478 | Biopsy specimens | Chronic HBV infection is strongly associated with increased risk for CRC. | [69] |

| García-Alonso et al, 2016 | HCV | CRC | Spain | 570 | Biopsy specimens | No statistically significant differences between HCV prevalence and risk factors for CRC. | [70] |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; CD, Crohn’s disease; cDNA, complementary DNA; CRC, colorectal cancer; gDNA, genomic DNA; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV: human papillomavirus; JCV, John Cunningham virus; Ref, reference; UC, ulcerative colitis.

USA, France, Italy, Japan, China, Taiwan (China).

Tunisia, China, Taiwan (China), Israel, USA, Iran, Portugal, Japan, Jordan, Netherlands, Italy, Greece, Poland.

3.1. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and viruses

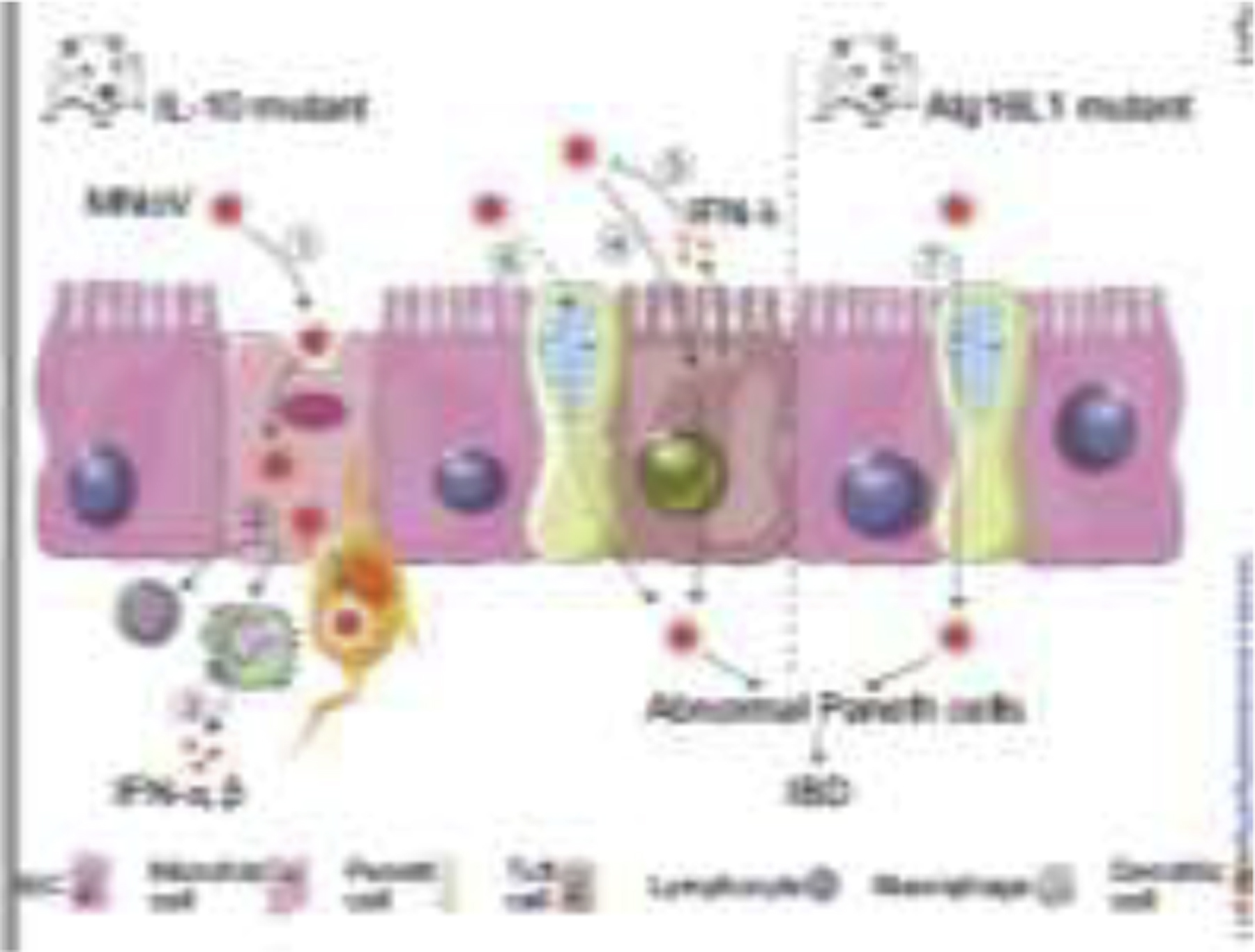

The composition of phages from individuals with IBD is significantly different from healthy controls [19, 37]. Patients with CD or UC exhibit a significant expansion of Caudovirales compared to Microviridae and a decrease in bacterial richness and diversity [19]. Caudovirales was also found to be increased in ileal biopsies of pediatric CD patients, but that in stool was not associated with UC onset [22]. In another study, patients with Herpesviridae sequences in the colons showed increased expression of human endogenous viral genes and increased microbiome diversity [42]. Within early-diagnosed treatment-naive IBD patients, patients with UC had a higher amount of Hepadnaviridae transcripts than patients with CD and controls, with a lower concentration of Polydnaviridae and Tymoviridae. In addition, CD patients showed an increased abundance of Hepeviridae compared to controls, with a reduced abundance of Virgaviridae [43]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is a species that is generally depleted in IBD patients. F. prausnitzii phages were found significantly more prevalent in samples from IBD patients than those of household controls, suggesting enhanced phage-mediated mortality of F. prausnitzii in IBD [44]. Significantly, specific viral infections can interact with IBD risk genes to alter intestinal disease in IL-10- or Atg16L1-deficient mice, indicating that certain species of the virome may contribute to IBD [45, 46] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Potential impact of enteric viruses on intestinal epithelial cells and host immune cells. In IL-10-deficient mice, MNoV ① crosses the epithelial barrier through microfold cells, ② infects immune cells including lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and ③ causes an interferon response (IFN-α, β). In IL-10-deficient mice, MNoV can ④ infect tuft cells, and ⑤ induce IFN-λ secretion, which plays a critical role in regulating persistent virus in vivo. ⑥ Persistent MNoV can also drive Paneth cell abnormalities related to IBD. ⑦ Mice with Atg16L1 mutations infected by MNoV trigger the abnormality of Paneth cell and display intestinal disease. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; MNoV, murine norovirus. The illustration was created by adapting SMART (https://smart.servier.com) and Vecteezy (vecteezy.com) templates.

3.2. Colorectal cancer and viruses

There are no significant differences in viral richness between CRC patients and healthy controls [43]. However, viral dysbiosis is reportedly associated with early- and late-stage CRCs [39]. Although the influence of viruses in the pathogenesis of CRC is growing, there has been no clear and consistent consensus conclusion yet. Further rigorous experimentation and cross-cohort validation are key to solve the myth, establishing or disproving the link of viruses to CRC, especially clinical prevalence and pathophysiology.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) genome was detected in CRC specimens, indicating a possible association of HPV presence with an increased risk of developing CRC [47, 48]. However, other studies questioned the role of HPV in CRC carcinogenesis because little or no HPV DNA was found in CRC specimens [49, 50], highlighting the need for additional research to clarify such inconsistency. Compared with HPV-negative tissues, four differentially expressed genes (WNT-5A, c-Myc, MMP-7, and AXIN2) were found to be up-regulated in HPV-positive CRC samples [51], consistent with an earlier report implicated HPV’s relevance to CRC pathogenesis [23].

It has been shown that human cytomegalovirus (CMV) preferentially infects CRC lesions rather than normal healthy tissue [52, 53], which may be related to the poor prognosis of CRC patients [54–56]. The phenomenon may be involved in CRC cell proliferation and progression, with higher expression of TLR2, TLR4, NF-κB, and TNF-α in CMV-infected CRC samples compared to control tissues [57], and increased expression levels of Bcl-2, cox-2, and Wnt/β-catenin in cancer cell lines [58, 59].

The members of the Polyomaviridae family, mainly human polyomavirus 2 (known as John Cunningham virus, JCV), are found to be linked to CRC, pointing towards a possible carcinogenic role of JCV [60–62]. However, little or no JCV DNA was detected in CRC samples in some studies [63, 64]. It has been proposed that JCV promotes colon carcinogenesis in the following ways: first, an early JCV protein T-antigen (T-ag) is believed to mediate the oncogenic potential of the virus and link to chromosomal instability [63, 65]; next, JCV may be responsible for the induction of polymorphisms and/or alterations in tumor suppressor genes (i.e., p53) [66]; last, JCV may alter cell behavior, such as migration and invasion, underlining a possible involvement of PI3K/AKT, MAPK and/or Wnt/β-catenin pathways [67].

In a rare study with Italian populations, CRC patients with hepatitis B and C virus-related liver diseases exhibited better 5-year disease-free survival and a lower incidence of metachronous liver metastases, claiming a “metalloproteinase inhibitor” hypothesis rather than a direct effect of the viral infection by the authors [68]. In a separate study, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was closely associated with an increased risk for CRC [69]. Another study found no correlation between hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and CRC development [70]. Due to the significant variability, it is necessary to further investigate the interrelationship between different types of hepatitis viruses, inflammatory diseases, and CRC.

3.3. The paradoxical role of phages in IBD and CRC

The same phages may act as a double-edged sword within the inflammatory environment of the gut. Caudovirales phages significantly reduce colonization by carcinogenic bacteria and increase the survival of animals predisposed to CRC development. However, the expansion of phages worsened IBD pathogenesis in mice [24]. Similarly, individuals with CD display a significant increase in the abundance of phages within the order Caudovirales [19]. It is necessary to analyze these complex interactions to test whether the viral microbiota may have therapeutic benefits in future work.

Thus, although it is debatable, studies in this area have found that some eukaryotic viruses can infect human cells, establish infections, trigger immune responses and, sometimes, cause serious diseases. Future studies should explore the alterations and impact of viral composition on specific intestinal disorders, including IBD and CRC.

4. Viruses that are likely associated with intestinal inflammation and cancer

Enteric viruses are first exposed to bacteria to initiate the replication in host cells (enterocytes or immune cells). Animal infection models have been commonly used to examine interactions between intestinal viruses and other microbes [71]. Currently, the experiments have been performed by using antibiotic-treated and germ-free mice or immune-deficient and/or young mice infected with human and murine viruses [28]. The beneficial effects of the bacterial microbiota on enteric viruses were not recognized until recently, possibly because many studies involved intraperitoneal injection viruses rather than the natural oral route [72, 73].

Since phages and bacteria are engaged in an intense arms race during evolution, phages may alter the bacterial microbiome and play a role in intestinal physiology and disease through complex mechanisms, which require extensive further elucidation (Figure 4A). First, enteric phages are responsible for the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among bacterial communities, including pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance, which impose a healthcare burden in controlling bacterial infection [74]. Second, the activation of phages leads to the lysis of their bacterial hosts and changes in the abundance of specific gut bacterial species [75]. Last (but not least), lysis of bacteria would release proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that serve as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) and antigens, which may trigger inflammatory signaling cascades to induce cytokines, cellular infiltration, and tissue damage [19].

Figure 4.

Transkingdom interactions and mechanisms. A, Phage directly or indirectly interacts with the host through the host-associated bacteria. These interactions may influence host genetic variations and pose distinct effects on host health. B, The mechanisms by which bacteria enhance enteric virus replication and transmission. C, Possible mechanisms of viruses affect the intestine. ① Virus can be sensed by the dendritic cell via RIG-I–MAVS–IRF1 pathway, which stimulates IL-15 secretion, thereby enhancing the proliferation and inhibiting the apoptosis of IELs. ② Resident virus is recognized by TLR3 and TLR7 on dendritic cells, producing protective IFN-β to suppress intestinal inflammation. ③ Phage is endocytosed in dendritic cells, activating B and T cells and stimulating IFN-γ-mediated TLR9-dependent immune responses, exacerbating colitis. IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide. The illustration was created by adapting SMART (https://smart.servier.com) and Vecteezy (vecteezy.com) templates.

Recent studies indicate that viruses would gain enhanced replication and transmission by bacteria via the following mechanisms (Figure 4B): (1) Virion stabilization by bacteria. Poliovirus (PV), spread through the fecal-oral route, could disseminate to the central nervous system. Intestinal bacteria stabilize virions and limit thermal inactivation to enhance PV replication and fecal-oral transmission in mice [76]. (2) Bacteria may increase host cell attachment. PV binds with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, a glycan on the surface of Gram-negative bacteria) and peptidoglycan (a major component of Gram-positive bacterial cell wall), which enhance the viral attachment to host cells [73, 76]. (3) Immune tolerance can be induced by virion-bound LPS. Mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), a member of the Retroviridae, is spread from mothers to offspring through milk in humans. MMTV binds to LPS, which induces host TLR signaling and IL-10-mediated immune tolerance and initiates viral replication and transmission [77]. (4) Host IFN-λ is likely regulated by microbiota. MNoV, a member of the norovirus genus within the Caliciviridae, is spread through the fecal-oral route. Bacteria promote MNoV replication, likely through the regulation of IFN-λ responses.

In addition to indirectly affecting the host through bacteria, phages can also directly interact with the host’s immune system and trigger immune responses. Accumulating evidence indicates that phages exert interactions with host intracellular immune pathways and activate immune responses in the intestine of individuals with IBD or CRC [24, 78, 79].

Commensal viruses have been shown to protect host animals against dextran sodium sulfate(DSS)-induced colitis via a beneficial effect on intraepithelial lymphocytes, through the RIG-I-MAVS-IRF1-IL15 axis [25], and suppression of the TLR3 and/or TLR7–IFN-β pathways [80] (Figure 4C). Caudovirales phages stimulated an immune response and aggravated colitis indirectly and directly. First, phages lyse bacteria and release pro-inflammatory products. Second, phages can promote the expansion of CD8+ and IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cell populations in lymph nodes in a TLR9/MyD88-dependent manner [24] (Figure 4C). After infection by Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages, peripheral blood monocytes exhibited a transcriptional response and notably enhanced transcription of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF [81]. The filamentous phages in the chronic human wounds infected by P. aeruginosa triggered TLR3 activation and production of type I IFN in immune cells. In turn, this type of cytokines (IFNα and IFNβ) inhibited TNF production by macrophages, thereby impairing phagocytosis and bacterial clearance and delaying wound healing [82]. Despite these advances in understanding phages’ interaction with bacteria, it is still very early to understand the arms race. In the future, more work may focus on the influence of enteric phages on the composition of the bacterial microbiota that affects phage fitness and pathogenesis.

Collectively, the interactions among viruses, bacteria, and the host immune system are being studied more commonly. However, in many cases, causality and molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood and should be explored more broadly mechanistically.

5. Phage-based therapeutics in intestinal inflammation and cancer

Phage-based therapeutics (also known as phage therapy) have existed for around 100 years [83]. The therapeutics for infectious diseases were almost abandoned in most western countries 60 years ago due to the unpredictable outcomes and dramatically improved therapy with newly discovered antibiotics [83]. However, in recent decades the abuse of antibiotics has caused the surge of antibiotic resistance. Due to the lack of effective treatments and the rapid evolution of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, phage therapies have found renewed enthusiasm as alternative approaches for multi-drug resistance bacterial infection, mostly in very severe cases. Therefore, there are a growing number of clinical reports and studies on the use of phage therapy to treat fatal bacterial infection [84] or other comorbidity diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [85, 86].

Not surprisingly, because certain pathogenic bacteria are associated with both IBD and CRC, several clinical trials with phage-related therapy are ongoing in treating colitis and CRC [26, 87]. Phage therapy may be advantageous in microbiome manipulation with the high specificity of phages targeting single bacterial species [88]. For example, phages are being tested against Clostridioides difficile in UC, adherent invasive Escherichia coli in CD, and Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer [21].

5.1. Phage-based therapy in IBD

Adherent-invasive E. coli (AIEC) might have a causal role in the pathogenesis of CD [89]. Galtier et al. isolated three phages targeting AIEC from wastewater, which can reduce the ileal and colonic colonization of AIEC and mitigate the symptoms of DSS-induced colitis in mice. This work provided a new therapeutic option in patients with CD [90]. A phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial (NCT03808103) is enrolling 30 CD patients to evaluate the effectiveness of the AIEC-specific bacteriophage cocktail (EcoActive) on disease activity, inflammatory markers, and AIEC load.

5.2. Phage-based therapy in CRC

Fusobacterium nucleatum is implicated in the pathogenesis of CRC [91, 92]. Phages targeting F. nucleatum have also entered clinical trials to utilize these viruses to treat CRC and reduce the cancer burdens [93]. However, this single targeting also presents a challenge in using phages for emerging bacterial strains that have no available specific and effective phages, which can be developed by isolating phages from the wild [94] or by engineering to generate multi-targeting universal phages [95]. Gogokhia et al. [24] reported that Caudovirales phages isolated from active UC patients inhibited the growth of cancer-causing adherent invasive E. coli and suppressed intestinal tumor growth in a mouse model. Additionally, phages encode a depolymerase that enables them to degrade biofilms and access the residing organisms [96, 97]. Phages could also be engineered to carry additional therapeutic advantages [98]. For instance, using azide-modified phages linked to irinotecan-dextran nanoparticles for treatment of mice bearing CT26 colorectal carcinomas decreased Fusobacterium spp. levels and effectively suppressed tumor growth [21].

These above studies highlight the need to indicate the potential therapeutic role of phage therapy in colitis and CRC. The major limitation that phages usually have a narrow target range for bacteria may be solved by engineering multi-valent, broad targeting artificial phages, or stock more wild-derived phages for clinical applications. Moreover, randomized controlled clinical trials on an increased scale are required to expand phage therapy applications in humans for treating IBD and CRC.

6. Oncolytic viruses for CRC treatment

Cancer virotherapy is immunotherapy based on oncolytic viruses (OVs) that modulate the tumor microenvironments (TME) to reverse the immunosuppressive states and subsequently stimulating anti-tumor immunity [99, 100]. OVs are natural or genetically modified viruses designed to target and kill cancer cells without apparent damage to normal cells [101]. Thus far, various DNA and RNA OVs are rapidly emerging as novel therapeutic approaches against cancer, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), vaccinia virus (VAC), adenovirus (AdV), reovirus (RV), measles virus (MeV), etc. [102]. OVs are currently optimized by genetic modification or combination with other strategies to provide greater specificity and efficacy against tumors without harming healthy cells [103]. The ongoing clinical trials in patients with CRC are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical trials using oncolytic viruses for treating CRC patients.

| Viral families | Viral species | Virus | Transgene | Condition | Administration | Combination | Status | Phase | Identifier1 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA | VAC | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | GM-CSF | CRC | i.v. | – | Completed | I | NCT01469611 | |

| dsDNA | VAC | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | GM-CSF | CRC | i.v. or i.t. | – | Completed | II | NCT01329809 | |

| dsDNA | VAC | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | GM-CSF | CRC | i.v. | Irinotecan | Completed | I/II | NCT01394939 | |

| dsDNA | VAC | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | GM-CSF | CRC | i.v. | – | Completed | I | NCT01380600 | |

| dsDNA | VAC | Pexa-Vec (JX-594) | GM-CSF | CRC | i.v. | anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4 | Active | I/II | NCT03206073 | [105] |

| dsDNA | VAC | TBio-6517 | FLT3 ligand, IL-12, anti-CTLA-4 | Solid tumors, TNBC, MSS-CRC | i.t. | anti-PD-1 | Recruiting | I/II | NCT04301011 | |

| dsDNA | AdV | LOAd703 | CD40L, 4-1 BBL | Pancreatic, ovarian, biliary cancer, CRC | i.t. | Chemotherapy | Recruiting | I/II | NCT03225989 | [108] |

| dsDNA | AdV | EnAd (ColoAd1) | – | Solid tumors of epithelial origin, metastatic CRC, and bladder cancer | i.v. | – | Completed | I/II | NCT02028442 | [111] |

| dsDNA | AdV | EnAd (ColoAd1) | – | Resectable CRC, non-small cell lung, bladder, renal cell cancer | i.v. or i.t. | – | Completed | I | NCT02053220 | [112] |

| dsDNA | AdV | EnAd (ColoAd1) | – | CRC, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | i.v. | anti-PD-1 | Active | I | NCT02636036 | |

| dsDNA | AdV | EnAd (ColoAd1) | – | Locally advanced rectal cancer | Capecitabine, radiotherapy | Recruiting | I | NCT03916510 | [110] | |

| dsDNA | HSV | T-VEC | GM-CSF | Metastatic TNBC & CRC | i.a. | anti-PD-L1 | Active | I | NCT03256344 | [106, 107] |

| dsDNA | HSV | NV1020 | – | CRC, liver neoplasms | i.a. | – | Completed | I/II | NCT00149396 | [121] |

| dsDNA | HSV | NV1020 | – | CRC, metastatic cancer | i.a. | – | Completed | I | NCT00012155 | [122] |

| dsDNA | HSV | OH2 | GM-CSF | Solid tumor, gastrointestinal cancer | i.v. | anti-PD-1, Irinotecan | Recruiting | I/II | NCT03866525 | |

| dsDNA | HSV | ONCR-177 | IL-12, CCL4, FLT3L, anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA-4 | CRC2 | i.t. | anti-PD-1 | Recruiting | I | NCT04348916 | [109] |

| Segmented dsRNA | RV | Reolysin | – | KRAS mutant metastatic CRC | i.v. | Irinotecan, Leucovorin, 5-FU, anti-VEGF | Completed | I | NCT01274624 | [113] |

| ssRNA | MeV | TMV-018 | Cytosine deaminase | Gastrointestinal cancer | i.t. | 5-FC, anti-PD-1 | Withdrawn | I | NCT04195373 |

5-FC, 5-fluorocytosine; 5-FU, fluorouracil; AdV, adenovirus; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HSV, herpes simplex virus; i.a., intrahepatic arterial; i.t., intratumoral; i.v., intravenous; MeV, measles virus; MSS-CRC, microsatellite stable colorectal cancer; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; Ref, reference; RV, reovirus; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; VAC, vaccinia virus; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; T-VEC, talimogene laherparepvec.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier.

Melanoma, solid tumor, squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, breast cancer, advanced solid tumor, TNBC, CRC, non-melanoma skin cancer, liver metastases. Source: clinicaltrials.gov; assessed May 2021.

OVs can act as cancer vaccines to increase tumor-specific T cell response. OVs can also be armed with immunostimulatory molecules (i.e., granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, GM-CSF) to improve their immune-activating characteristic. The OVs armed with GM-CSF facilitate dendritic cell (DC) migration and maturation, eventually leading to enhanced priming of T cell responses [104], such as talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) and pexastimogene devacirepvec (Pexa-Vec or JX-594) [105]. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) system (HSV) is a well-known, therapeutically modified virus. T-VEC has been approved by both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency to treat metastatic melanomas [106, 107]. T-VEC is currently under clinical trial for CRC [106, 107]. Pexa-Vec is a VAC modified to encode GM-CSF and β-galactosidase to inactivate the viral thymidine kinase gene and is currently undergoing multiple clinical trials [105].

IL-12, a major orchestrator of Th1-type immune response against cancer, is another cytokine used for arming OVs, such as TBio-6517 (Phase I/II) and ONCR-177 (Phase I) [108, 109]. LOAd703 (Phase I/II) is a double-armed ADV combined of two tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF) family ligands CD40L and 4-1BBL, which stimulates T cell expansion, acquisition of effector function, survival, and development of T cell memory [108].

Enadenotucirev (EnAd; ColoAd1) is a complex chimeric virus resulting from recombination between different adenovirus serotypes, and is currently under clinical investigations [110–112]. Unmodified viruses, such as the reovirus Pelareorep (Reolysin), are also being examined in clinical trials for CRC treatment [113].

In addition, OVs can be engineered in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) or cytotoxic agents to achieve the most potent cancer immunotherapy through a synergistic mechanism, such as Pexa-Vec with Tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) and Durvalumab (against PD-L1), TBio-6517 with Pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), ColoAd1 with nivolumab (anti-PD-1), T-VEC with Atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1), OH2 with HX008 (anti-PD-1), and ONCR-177 with Pembrolizumab. Through these multi-pronged research and clinical trials, we envision that some OVs may be able to earn FDA approval for clinical applications in cancer treatment successfully.

7. Emerging technologies for investigating enteric virome

The emergence of high throughput metagenomic sequencing technology allows us to understand the complexity and richness of human gut bacteriophage and various viruses’ populations [27, 114]. However, compared to the bacterial component of the intestinal microbiome, the enteric virome has been almost ignored, largely due to the limited tools available for virus identification and classification [115]. It might also be due to the significant interest in the bacterial microbiome per se, so the importance of virome is somewhat ignored. In addition, viruses exist in several genetic forms that differ by the backbone nucleic acid (RNA or DNA), the feature of strands (positive or negative sense), and the number of strands (single vs. double strands). The complexity of viruses poses challenges for library preparation and sequencing strategies. At present, it is estimated that merely 1% of the virome has been sequenced, and the number of unclassifiable sequences (taxonomically or functionally) ranges from 60% to 90% (called ‘viral dark matter’), which is awaiting characterized [116].

VLPs fractions can be examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [117], metagenomic sequencing [31], or high-throughput short-read-based technologies (Roche 454, Illumina platforms, and Ion Torrent platforms) [29]. Recently, two long-read sequencing technologies (Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore) have been developed. These technologies can assist in the construction of large novel viral genomes, obtain information on methylation patterns [118], and study population structure at a single virion level [119]. The virus metagenomic analysis workflow includes quality control, filtering and trimming of non-target reads, assembly of reads into contigs, removal of bacterial contamination, alignments to viral genomes in viral databases, and downstream analysis. A number of software and databases have been specifically designed to process high-throughput virome sequencing data (Table 3). These tools should be used after careful consideration of sample type and scientific questions. Therefore, a critical limitation is whether to have an expert bioinformatician and the appropriate hardware necessary to perform such extensive and time-consuming analysis.

Table 3.

Selected methods and databases for viral metagenomic analysis.

| Tool | Description | Reference | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality control and filtering non-target reads | |||

| Trimmomatic | A variety of useful trimming tasks for Illumina paired-end and single-ended data. | [123] | https://github.com/timflutre/trimmomatic |

| fastp | Providing fast all-in-one preprocessing for fastq files, including quality control, trimming adapters, filtering by quality, and read pruning. | [124] | https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp |

| cutadapt | Finding and removing adapter sequences, primers, poly-A tails, and other types of unwanted sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. | [125] | https://github.com/marcelm/cutadapt/ |

| FastQC | An application that takes a fastq file and runs a series of tests on it to generate a comprehensive QC report. | [126] | http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/download.html#fastqc |

| Short Read Assembly | |||

| de novo assembly and mapping | |||

| SPAdes | An assembly toolkit containing various assembly pipelines for high-throughput sequencing data. | [127] | https://github.com/ablab/spades |

| VirFinder | A novel k-mer based tool for identifying viral sequences from assembled metagenomic data. | [128] | https://github.com/jessieren/VirFinder |

| SunBeam | An extensible pipeline for analyzing metagenomic sequencing experiments. | [129] | https://github.com/sunbeam-labs/sunbeam |

| Reference-based mapping | |||

| Bowtie 2 | An ultrafast and memory-efficient tool for aligning sequencing reads to long reference sequences. | [130] | https://github.com/BenLangmead/bowtie2 |

| bwa | A software package for mapping DNA sequences against a large reference genome. | [131] | https://github.com/lh3/bwa |

| Kraken2 | A taxonomic classification system using exact k-mer matches to achieve high accuracy and fast classification speeds. | [132] | https://github.com/DerrickWood/kraken2 |

| Pavian | A comprehensive visualization program that can compare Kraken 2 classifications across multiple samples. | [133] | https://github.com/fbreitwieser/pavian |

| Bracken | Allows users to estimate relative abundances within a specific sample from Kraken 2 classification results. | [134] | https://github.com/jenniferlu717/Bracken |

| Downstream analysis | |||

| mauve | A system for constructing multiple genome alignments in the presence of large-scale evolutionary events such as rearrangement and inversion. | [135] | http://darlinglab.org/mauve/mauve.html |

| PyANI | Pairwise average nucleotide identity between genomes. | https://github.com/widdowquinn/pyani | |

| Gview | A Java package used to display and navigate bacterial genomes. | [136] | https://github.com/phac-nml/gview-wiki/wiki |

| vegan | Ordination methods, diversity analysis, and other functions for community and vegetation ecologists. | https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan | |

| ape | Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequence data. | [137] | http://ape-package.ird.fr/ |

| Databases | |||

| NCBI RefSeq Viral Genomes | Provide viral genome sequence data and related information. | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/viruses/ | |

| IMG/VR | Provide information of genomes of cultivated and uncultivated viruses. | [138] | https://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/vr/main.cgi |

| pVOGs | Provides access to the most recent database 9,518 orthologous groups shared among nearly 3,000 thousand complete genomes of viruses that infect bacteria and archaea (Prokaryotic Virus Orthologous Groups, or pVOGs). | [139] | http://dmk-brain.ecn.uiowa.edu/pVOGs/ |

Apart from the virome metagenomic sequencing, additional future complementary approaches may include gut viral metatranscriptomics (RNA-seq) and viral metaproteomics [29, 120]. The technologies mentioned above and other future development may well shape virome research to probe the pathogenesis of gut virome and its potential beneficial influence in humans, providing insight into the design of effective virome-based therapy for intestine and colorectal diseases.

8. Challenges and future directions

Despite these relatively rapid advances, there are still major gaps in our understanding of the nature of enteric viruses.

Although the involvement of viruses in the development of colitis and CRC has become increasingly evident, the current concepts and observations need further testing and verification.

With the advent of many new technologies, such as nucleic acid sequencing, omics analysis, and bioinformatics pipelines, the characterization of the gut virome and its role in the development of pathological conditions is still at an early stage.

The virus database is ralatively small and incomplete (compared to the bacterial genome database), limiting our ability to dissect the detail of mucosal viromes in health and disease.

Virology research regarding human health faces considerable inter-individual variability that may be affected by many factors, such as age, sex, ethnicity, geography, diet, and sample collection, storage, and processing.

In summary, there are many important advances in virome research, basic understanding, disease relevance, and clinical usage/therapy; there are also multiple hurdles. These obstacles mentioned above must be addressed appropriately before phage therapy and OVs are approved for broad-scope clinical application. Despite these concerns, viral therapeutics may be worth exploring and may have huge potential through molecular engineering.

Besides providing a basic concept and summarizing the connection of virome to IBD and CRC, we also discussed that phages are a promising therapeutic tool against pathogenic bacteria for human inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials with phage therapy are already ongoing in IBD and CRC. In addition, there is an urgent need to design new approaches and invent methods in virus isolation, metagenomics, enrichment culture, and bioinformatics tools to improve our ability to define and characterize viruses in the future. Further large-scale longitudinal and long-term follow-up prospective studies, as well as in-depth experimental investigation and validation are necessary. The key direction in this field is to determine the dynamic relationship (e.g., causal role) between the intestinal microbiota and innate and adaptive immunity. Furthermore, phage therapy may be applied together with bacterial or other microbiota components (via FMT, pre- and probiotics) to alter virulence and immunogenicity, effectively taming the exacerbated inflammatory disease in humans and improving human health.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AI138203 and AI109317, P20 GM103442 and GM113123 to MW) and the National Key Research and Development Project (2020YFA0509400), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019B030302012), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81821002, 81790251, and 82130082) to CH. Illustrations were created by modifying elements and templates from Vecteezy (vecteezy.com) and Smart Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Abbreviations

- 5-FC

5-fluorocytosine

- 5-FU

fluorouracil

- AdV

adenovirus

- ALEC

Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli

- CAC

colitis-associated colorectal cancer

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4

- dsDNA

double-stranded DNA

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

- EnAd

Enadenotucirev

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- gDNA

genomic DNA

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HSV

herpes simplex type virus

- i.a.

intrahepatic arterial

- i.t.

intratumoral

- i.v.

intravenous

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- JCV

John Cunningham virus

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MeV

measles virus

- MMTV

Mouse mammary tumor virus

- MNoV

Murine norovirus

- MSS-CRC

microsatellite stable colorectal cancer

- OV

oncolytic virus

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1

programmed death ligand-1

- Pexa-Vec

pexastimogene devacirepvec

- PV

poliovirus

- Ref

reference

- RV

reovirus

- ssDNA

single-stranded DNA

- ssRNA

single-stranded RNA

- T-VEC

Talimogene laherparepvec

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- VAC

vaccinia virus

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VLP

virus-like particle

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].I.A.f.R.o. Cancer, GLOBOCAN 2020 Database Provides Latest Global Data on Cancer Burden, Cancer Deaths, 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lasry A, Zinger A, Ben-Neriah Y, Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer, Nat Immunol 17(3) (2016) 230–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhao Y, Jiang Q, Roles of the Polyphenol-Gut Microbiota Interaction in Alleviating Colitis and Preventing Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer, Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B, Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies, Inflamm Bowel Dis 19(4) (2013) 789–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies, Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10(6) (2012) 639–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig CM, Osada N, Rijcken E, Vowinkel T, Krieglstein CF, Senninger N, Anthoni C, Bruewer M, Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis, J Gastrointest Surg 15(4) (2011) 576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang T, Fan C, Yao A, Xu X, Zheng G, You Y, Jiang C, Zhao X, Hou Y, Hung MC, Lin X, The Adaptor Protein CARD9 Protects against Colon Cancer by Restricting Mycobiota-Mediated Expansion of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells, Immunity 49(3) (2018) 504–514.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhu W, Miyata N, Winter MG, Arenales A, Hughes ER, Spiga L, Kim J, Sifuentes-Dominguez L, Starokadomskyy P, Gopal P, Byndloss MX, Santos RL, Burstein E, Winter SE, Editing of the gut microbiota reduces carcinogenesis in mouse models of colitis-associated colorectal cancer, J Exp Med 216(10) (2019) 2378–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr., Wilson KT, Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk, Clin Microbiol Rev 23(4) (2010) 713–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stanley M, Tumour virus vaccines: hepatitis B virus and human papillomavirus, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372(1732) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lin MV, King LY, Chung RT, Hepatitis C virus-associated cancer, Annu Rev Pathol 10 (2015) 345–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Janney A, Powrie F, Mann EH, Host-microbiota maladaptation in colorectal cancer, Nature 585(7826) (2020) 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Mühlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, Abujamel T, Dogan B, Rogers AB, Rhodes JM, Stintzi A, Simpson KW, Hansen JJ, Keku TO, Fodor AA, Jobin C, Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota, Science 338(6103) (2012) 120–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Personal habits and indoor combustions. Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens, IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 100(Pt E) (2012) 1–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Locey KJ, Lennon JT, Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(21) (2016) 5970–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kang M, Martin A, Microbiome and colorectal cancer: Unraveling host-microbiota interactions in colitis-associated colorectal cancer development, Seminars in immunology 32 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sepich-Poore GD, Zitvogel L, Straussman R, Hasty J, Wargo JA, Knight R, The microbiome and human cancer, Science 371(6536) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Duerkop BA, Kleiner M, Paez-Espino D, Zhu W, Bushnell B, Hassell B, Winter SE, Kyrpides NC, Hooper LV, Murine colitis reveals a disease-associated bacteriophage community, Nat Microbiol 3(9) (2018) 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, Droit L, Liu CY, Keller BC, Kambal A, Monaco CL, Zhao G, Fleshner P, Stappenbeck TS, McGovern DP, Keshavarzian A, Mutlu EA, Sauk J, Gevers D, Xavier RJ, Wang D, Parkes M, Virgin HW, Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease, Cell 160(3) (2015) 447–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sokol H, Leducq V, Aschard H, Pham HP, Jegou S, Landman C, Cohen D, Liguori G, Bourrier A, Nion-Larmurier I, Cosnes J, Seksik P, Langella P, Skurnik D, Richard ML, Beaugerie L, Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD, Gut 66(6) (2017) 1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zheng DW, Dong X, Pan P, Chen KW, Fan JX, Cheng SX, Zhang XZ, Phage-guided modulation of the gut microbiota of mouse models of colorectal cancer augments their responses to chemotherapy, Nat Biomed Eng 3(9) (2019) 717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wagner J, Maksimovic J, Farries G, Sim WH, Bishop RF, Cameron DJ, Catto-Smith AG, Kirkwood CD, Bacteriophages in gut samples from pediatric Crohn’s disease patients: metagenomic analysis using 454 pyrosequencing, Inflamm Bowel Dis 19(8) (2013) 1598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Marônek M, Link R, Monteleone G, Gardlík R, Stolfi C, Viruses in Cancers of the Digestive System: Active Contributors or Idle Bystanders?, Int J Mol Sci 21(21) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gogokhia L, Buhrke K, Bell R, Hoffman B, Brown DG, Hanke-Gogokhia C, Ajami NJ, Wong MC, Ghazaryan A, Valentine JF, Porter N, Martens E, O’Connell R, Jacob V, Scherl E, Crawford C, Stephens WZ, Casjens SR, Longman RS, Round JL, Expansion of Bacteriophages Is Linked to Aggravated Intestinal Inflammation and Colitis, Cell Host Microbe 25(2) (2019) 285–299.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu L, Gong T, Tao W, Lin B, Li C, Zheng X, Zhu S, Jiang W, Zhou R, Commensal viruses maintain intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes via noncanonical RIG-I signaling, Nat Immunol 20(12) (2019) 1681–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gutiérrez B, Domingo-Calap P, Phage Therapy in Gastrointestinal Diseases, Microorganisms 8(9) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Breitbart M, Hewson I, Felts B, Mahaffy JM, Nulton J, Salamon P, Rohwer F, Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces, J Bacteriol 185(20) (2003) 6220–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pfeiffer JK, Virgin HW, Viral immunity. Transkingdom control of viral infection and immunity in the mammalian intestine, Science 351(6270) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shkoporov AN, Hill C, Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The “Known Unknown” of the Microbiome, Cell Host Microbe 25(2) (2019) 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Neve H, Gibson GR, Sanderson JD, Heller KJ, van Sinderen D, Characterization of virus-like particles associated with the human faecal and caecal microbiota, Res Microbiol 165(10) (2014) 803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dion MB, Oechslin F, Moineau S, Phage diversity, genomics and phylogeny, Nat Rev Microbiol 18(3) (2020) 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Manrique P, Bolduc B, Walk ST, van der Oost J, de Vos WM, Young MJ, Healthy human gut phageome, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(37) (2016) 10400–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shkoporov AN, Ryan FJ, Draper LA, Forde A, Stockdale SR, Daly KM, McDonnell SA, Nolan JA, Sutton TDS, Dalmasso M, McCann A, Ross RP, Hill C, Reproducible protocols for metagenomic analysis of human faecal phageomes, Microbiome 6(1) (2018) 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guerin E, Shkoporov A, Stockdale SR, Clooney AG, Ryan FJ, Sutton TDS, Draper LA, Gonzalez-Tortuero E, Ross RP, Hill C, Biology and Taxonomy of crAss-like Bacteriophages, the Most Abundant Virus in the Human Gut, Cell Host Microbe 24(5) (2018) 653–664.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Devoto AE, Santini JM, Olm MR, Anantharaman K, Munk P, Tung J, Archie EA, Turnbaugh PJ, Seed KD, Blekhman R, Aarestrup FM, Thomas BC, Banfield JF, Megaphages infect Prevotella and variants are widespread in gut microbiomes, Nat Microbiol 4(4) (2019) 693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reese TA, Bi K, Kambal A, Filali-Mouhim A, Beura LK, Bürger MC, Pulendran B, Sekaly RP, Jameson SC, Masopust D, Haining WN, Virgin HW, Sequential Infection with Common Pathogens Promotes Human-like Immune Gene Expression and Altered Vaccine Response, Cell Host Microbe 19(5) (2016) 713–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zuo T, Lu XJ, Zhang Y, Cheung CP, Lam S, Zhang F, Tang W, Ching JYL, Zhao R, Chan PKS, Sung JJY, Yu J, Chan FKL, Cao Q, Sheng JQ, Ng SC, Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis, Gut 68(7) (2019) 1169–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hannigan GD, Duhaime MB, Ruffin M.T.t., Koumpouras CC, Schloss PD, Diagnostic Potential and Interactive Dynamics of the Colorectal Cancer Virome, mBio 9(6) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nakatsu G, Zhou H, Wu WKK, Wong SH, Coker OO, Dai Z, Li X, Szeto CH, Sugimura N, Lam TY, Yu AC, Wang X, Chen Z, Wong MC, Ng SC, Chan MTV, Chan PKS, Chan FKL, Sung JJ, Yu J, Alterations in Enteric Virome Are Associated With Colorectal Cancer and Survival Outcomes, Gastroenterology 155(2) (2018) 529–541.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kirk MD, Pires SM, Black RE, Caipo M, Crump JA, Devleesschauwer B, Döpfer D, Fazil A, Fischer-Walker CL, Hald T, Hall AJ, Keddy KH, Lake RJ, Lanata CF, Torgerson PR, Havelaar AH, Angulo FJ, World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis, PLoS Med 12(12) (2015) e1001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Karst SM, Wobus CE, Goodfellow IG, Green KY, Virgin HW, Advances in norovirus biology, Cell Host Microbe 15(6) (2014) 668–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang W, Jovel J, Halloran B, Wine E, Patterson J, Ford G, OʼKeefe S, Meng B, Song D, Zhang Y, Tian Z, Wasilenko ST, Rahbari M, Reza S, Mitchell T, Jordan T, Carpenter E, Madsen K, Fedorak R, Dielemann LA, Ka-Shu Wong G, Mason AL, Metagenomic analysis of microbiome in colon tissue from subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases reveals interplay of viruses and bacteria, Inflamm Bowel Dis 21(6) (2015) 1419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ungaro F, Massimino L, Furfaro F, Rimoldi V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, D’Alessio S, Danese S, Metagenomic analysis of intestinal mucosa revealed a specific eukaryotic gut virome signature in early-diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease, Gut Microbes 10(2) (2019) 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cornuault JK, Petit MA, Mariadassou M, Benevides L, Moncaut E, Langella P, Sokol H, De Paepe M, Phages infecting Faecalibacterium prausnitzii belong to novel viral genera that help to decipher intestinal viromes, Microbiome 6(1) (2018) 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Basic M, Keubler LM, Buettner M, Achard M, Breves G, Schröder B, Smoczek A, Jörns A, Wedekind D, Zschemisch NH, Günther C, Neumann D, Lienenklaus S, Weiss S, Hornef MW, Mähler M, Bleich A, Norovirus triggered microbiota-driven mucosal inflammation in interleukin 10-deficient mice, Inflamm Bowel Dis 20(3) (2014) 431–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, Liu TC, Ng AC, Storer CE, Head RD, Xavier R, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW, Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine, Cell 141(7) (2010) 1135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Damin DC, Caetano MB, Rosito MA, Schwartsmann G, Damin AS, Frazzon AP, Ruppenthal RD, Alexandre CO, Evidence for an association of human papillomavirus infection and colorectal cancer, Eur J Surg Oncol 33(5) (2007) 569–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ibragimova MK, Tsyganov MM, Litviakov NV, Human papillomavirus and colorectal cancer, Med Oncol 35(11) (2018) 140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Burnett-Hartman AN, Feng Q, Popov V, Kalidindi A, Newcomb PA, Human papillomavirus DNA is rarely detected in colorectal carcinomas and not associated with microsatellite instability: the Seattle colon cancer family registry, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22(2) (2013) 317–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gornick MC, Castellsague X, Sanchez G, Giordano TJ, Vinco M, Greenson JK, Capella G, Raskin L, Rennert G, Gruber SB, Moreno V, Human papillomavirus is not associated with colorectal cancer in a large international study, Cancer Causes Control 21(5) (2010) 737–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Qiu Q, Li Y, Fan Z, Yao F, Shen W, Sun J, Yuan Y, Chen J, Cai L, Xie Y, Liu K, Chen X, Jiao X, Gene Expression Analysis of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Colorectal Carcinoma, Biomed Res Int 2020 (2020) 5201587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Chen HP, Jiang JK, Chen CY, Chou TY, Chen YC, Chang YT, Lin SF, Chan CH, Yang CY, Lin CH, Lin JK, Cho WL, Chan YJ, Human cytomegalovirus preferentially infects the neoplastic epithelium of colorectal cancer: a quantitative and histological analysis, J Clin Virol 54(3) (2012) 240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dimberg J, Hong TT, Skarstedt M, Löfgren S, Zar N, Matussek A, Detection of cytomegalovirus DNA in colorectal tissue from Swedish and Vietnamese patients with colorectal cancer, Anticancer Res 33(11) (2013) 4947–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chen HP, Jiang JK, Lai PY, Chen CY, Chou TY, Chen YC, Chan CH, Lin SF, Yang CY, Chen CY, Lin CH, Lin JK, Ho DM, Cho WL, Chan YJ, Tumoral presence of human cytomegalovirus is associated with shorter disease-free survival in elderly patients with colorectal cancer and higher levels of intratumoral interleukin-17, Clin Microbiol Infect 20(7) (2014) 664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen HP, Jiang JK, Chen CY, Yang CY, Chen YC, Lin CH, Chou TY, Cho WL, Chan YJ, Identification of human cytomegalovirus in tumour tissues of colorectal cancer and its association with the outcome of non-elderly patients, J Gen Virol 97(9) (2016) 2411–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen HP, Jiang JK, Chan CH, Teo WH, Yang CY, Chen YC, Chou TY, Lin CH, Chan YJ, Genetic polymorphisms of the human cytomegalovirus UL144 gene in colorectal cancer and its association with clinical outcome, J Gen Virol 96(12) (2015) 3613–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Li X, Qian D, Ju F, Wang B, Upregulation of Toll-like receptor 2 expression in colorectal cancer infected by human cytomegalovirus, Oncol Lett 9(1) (2015) 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Teo WH, Chen HP, Huang JC, Chan YJ, Human cytomegalovirus infection enhances cell proliferation, migration and upregulation of EMT markers in colorectal cancer-derived stem cell-like cells, Int J Oncol 51(5) (2017) 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Harkins L, Volk AL, Samanta M, Mikolaenko I, Britt WJ, Bland KI, Cobbs CS, Specific localisation of human cytomegalovirus nucleic acids and proteins in human colorectal cancer, Lancet 360(9345) (2002) 1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Fernandes Q, Gupta I, Vranic S, Al Moustafa AE, Human Papillomaviruses and Epstein-Barr Virus Interactions in Colorectal Cancer: A Brief Review, Pathogens 9(4) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Jung WT, Li MS, Goel A, Boland CR, JC virus T-antigen expression in sporadic adenomatous polyps of the colon, Cancer 112(5) (2008) 1028–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Shavaleh R, Kamandi M, Feiz Disfani H, Mansori K, Naseri SN, Rahmani K, Ahmadi Kanrash F, Association between JC virus and colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis, Infect Dis (Lond) 52(3) (2020) 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Campello C, Comar M, Zanotta N, Minicozzi A, Rodella L, Poli A, Detection of SV40 in colon cancer: a molecular case-control study from northeast Italy, J Med Virol 82(7) (2010) 1197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Gock M, Kordt M, Matschos S, Mullins CS, Linnebacher M, Patient-individual cancer cell lines and tissue analysis delivers no evidence of sequences from DNA viruses in colorectal cancer cells, BMC Gastroenterol 20(1) (2020) 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Goel A, Li MS, Nagasaka T, Shin SK, Fuerst F, Ricciardiello L, Wasserman L, Boland CR, Association of JC virus T-antigen expression with the methylator phenotype in sporadic colorectal cancers, Gastroenterology 130(7) (2006) 1950–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Coelho TR, Gaspar R, Figueiredo P, Mendonça C, Lazo PA, Almeida L, Human JC polyomavirus in normal colorectal mucosa, hyperplastic polyps, sporadic adenomas, and adenocarcinomas in Portugal, J Med Virol 85(12) (2013) 2119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Enam S, Del Valle L, Lara C, Gan DD, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Palazzo JP, Khalili K, Association of human polyomavirus JCV with colon cancer: evidence for interaction of viral T-antigen and beta-catenin, Cancer Res 62(23) (2002) 7093–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Li Destri G, Castaing M, Ferlito F, Minutolo V, Di Cataldo A, Puleo S, Rare hepatic metastases of colorectal cancer in livers with symptomatic HBV and HCV hepatitis, Ann Ital Chir 84(3) (2013) 323–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Su FH, Le TN, Muo CH, Te SA, Sung FC, Yeh CC, Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection Associated with Increased Colorectal Cancer Risk in Taiwanese Population, Viruses 12(1) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].García-Alonso FJ, Bonillo-Cambrodón D, Bermejo A, García-Martínez J, Hernández-Tejero M, Valer López Fando P, Piqueras B, Bermejo F, Acceptance, yield and feasibility of attaching HCV birth cohort screening to colorectal cancer screening in Spain, Dig Liver Dis 48(10) (2016) 1237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Robinson CM, Pfeiffer JK, Viruses and the Microbiota, Annu Rev Virol 1 (2014) 55–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Baldridge MT, Nice TJ, McCune BT, Yokoyama CC, Kambal A, Wheadon M, Diamond MS, Ivanova Y, Artyomov M, Virgin HW, Commensal microbes and interferon-λ determine persistence of enteric murine norovirus infection, Science 347(6219) (2015) 266–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kuss SK, Best GT, Etheredge CA, Pruijssers AJ, Frierson JM, Hooper LV, Dermody TS, Pfeiffer JK, Intestinal microbiota promote enteric virus replication and systemic pathogenesis, Science 334(6053) (2011) 249–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Doran SJ, Henry RJ, Shirey KA, Barrett JP, Ritzel RM, Lai W, Blanco JC, Faden AI, Vogel SN, Loane DJ, Early or Late Bacterial Lung Infection Increases Mortality After Traumatic Brain Injury in Male Mice and Chronically Impairs Monocyte Innate Immune Function, Crit Care Med 48(5) (2020) e418–e428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Reyes A, Wu M, McNulty NP, Rohwer FL, Gordon JI, Gnotobiotic mouse model of phage-bacterial host dynamics in the human gut, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110(50) (2013) 20236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Robinson CM, Jesudhasan PR, Pfeiffer JK, Bacterial lipopolysaccharide binding enhances virion stability and promotes environmental fitness of an enteric virus, Cell Host Microbe 15(1) (2014) 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wilks J, Lien E, Jacobson AN, Fischbach MA, Qureshi N, Chervonsky AV, Golovkina TV, Mammalian Lipopolysaccharide Receptors Incorporated into the Retroviral Envelope Augment Virus Transmission, Cell Host Microbe 18(4) (2015) 456–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Duerkop BA, Hooper LV, Resident viruses and their interactions with the immune system, Nat Immunol 14(7) (2013) 654–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Roach DR, Leung CY, Henry M, Morello E, Singh D, Di Santo JP, Weitz JS, Debarbieux L, Synergy between the Host Immune System and Bacteriophage Is Essential for Successful Phage Therapy against an Acute Respiratory Pathogen, Cell Host Microbe 22(1) (2017) 38–47.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Yang JY, Kim MS, Kim E, Cheon JH, Lee YS, Kim Y, Lee SH, Seo SU, Shin SH, Choi SS, Kim B, Chang SY, Ko HJ, Bae JW, Kweon MN, Enteric Viruses Ameliorate Gut Inflammation via Toll-like Receptor 3 and Toll-like Receptor 7-Mediated Interferon-β Production, Immunity 44(4) (2016) 889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Van Belleghem JD, Clement F, Merabishvili M, Lavigne R, Vaneechoutte M, Pro- and anti-inflammatory responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages, Sci Rep 7(1) (2017) 8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Sweere JM, Van Belleghem JD, Ishak H, Bach MS, Popescu M, Sunkari V, Kaber G, Manasherob R, Suh GA, Cao X, de Vries CR, Lam DN, Marshall PL, Birukova M, Katznelson E, Lazzareschi DV, Balaji S, Keswani SG, Hawn TR, Secor PR, Bollyky PL, Bacteriophage trigger antiviral immunity and prevent clearance of bacterial infection, Science 363(6434) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG Jr., Bacteriophage therapy, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45(3) (2001) 649–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, Russell DA, Ford K, Harris K, Gilmour KC, Soothill J, Jacobs-Sera D, Schooley RT, Hatfull GF, Spencer H, Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus, Nat Med 25(5) (2019) 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Hoyle N, Zhvaniya P, Balarjishvili N, Bolkvadze D, Nadareishvili L, Nizharadze D, Wittmann J, Rohde C, Kutateladze M, Phage therapy against Achromobacter xylosoxidans lung infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis: a case report, Res Microbiol 169(9) (2018) 540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Richter WO, [Regulation of lipolysis of fatty tissue by peptide hormones], Fortschr Med 106(6) (1988) 117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Sabino J, Hirten RP, Colombel JF, Review article: bacteriophages in gastroenterology-from biology to clinical applications, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 51(1) (2020) 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Lee HL, Shen H, Hwang IY, Ling H, Yew WS, Lee YS, Chang MW, Targeted Approaches for In Situ Gut Microbiome Manipulation, Genes (Basel) 9(7) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Palmela C, Chevarin C, Xu Z, Torres J, Sevrin G, Hirten R, Barnich N, Ng SC, Colombel JF, Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease, Gut 67(3) (2018) 574–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Galtier M, De Sordi L, Sivignon A, de Vallée A, Maura D, Neut C, Rahmouni O, Wannerberger K, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Desreumaux P, Barnich N, Debarbieux L, Bacteriophages Targeting Adherent Invasive Escherichia coli Strains as a Promising New Treatment for Crohn’s Disease, J Crohns Colitis 11(7) (2017) 840–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson L, Glickman JN, Gallini CA, Michaud M, Clancy TE, Chung DC, Lochhead P, Hold GL, El-Omar EM, Brenner D, Fuchs CS, Meyerson M, Garrett WS, Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment, Cell Host Microbe 14(2) (2013) 207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Cao Y, Sukawa Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Song M, Kostic AD, Giannakis M, Bullman S, Milner DA, Baba H, Giovannucci EL, Garraway LA, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C, Meyerson M, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Ogino S, Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis, Gut 65(12) (2016) 1973–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ninio-Many N.B. Lihi, Slutskin Ilya Vainberg, Weiner Iddo, Yahav Sagit, Zigelman Yael, Dikla Berko-Ashur, Julian Nicenboim, Zelcbuch Lior, Gartman Einav Safyon, Kahan-Hanum Maya, Kredo-Russo Sharon, Golembo Myriam, Zak Naomi, Gahali-Sass Inbar, Puttagunta Sailaja and Bassan Merav, Novel Analysis of Fusobacterium Nucleatum Subspecies in Human Colorectal Cancer and Engineering of Therapeutic Bacteriophage, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Immuno-Oncology Virtual Congress 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [94].Chen F, Cheng X, Li J, Yuan X, Huang X, Lian M, Li W, Huang T, Xie Y, Liu J, Gao P, Wei X, Wang Z, Wu M, Novel Lytic Phages Protect Cells and Mice against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection, J Virol 95(8) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Yehl K, Lemire S, Yang AC, Ando H, Mimee M, Torres MT, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Lu TK, Engineering Phage Host-Range and Suppressing Bacterial Resistance through Phage Tail Fiber Mutagenesis, Cell 179(2) (2019) 459–469.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Knecht LE, Veljkovic M, Fieseler L, Diversity and Function of Phage Encoded Depolymerases, Front Microbiol 10 (2019) 2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Alves DR, Perez-Esteban P, Kot W, Bean JE, Arnot T, Hansen LH, Enright MC, Jenkins AT, A novel bacteriophage cocktail reduces and disperses Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms under static and flow conditions, Microb Biotechnol 9(1) (2016) 61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kilcher S, Loessner MJ, Engineering Bacteriophages as Versatile Biologics, Trends Microbiol 27(4) (2019) 355–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Shin DH, Nguyen T, Ozpolat B, Lang F, Alonso M, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J, Current strategies to circumvent the antiviral immunity to optimize cancer virotherapy, J Immunother Cancer 9(4) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Tang J, Shalabi A, Hubbard-Lucey VM, Comprehensive analysis of the clinical immune-oncology landscape, Ann Oncol 29(1) (2018) 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Ylösmäki E, Cerullo V, Design and application of oncolytic viruses for cancer immunotherapy, Curr Opin Biotechnol 65 (2020) 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Jin KT, Du WL, Liu YY, Lan HR, Si JX, Mou XZ, Oncolytic Virotherapy in Solid Tumors: The Challenges and Achievements, Cancers (Basel) 13(4) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Yu F, Wang X, Guo ZS, Bartlett DL, Gottschalk SM, Song XT, T-cell engager-armed oncolytic vaccinia virus significantly enhances antitumor therapy, Mol Ther 22(1) (2014) 102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Bommareddy PK, Patel A, Hossain S, Kaufman HL, Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC) and Other Oncolytic Viruses for the Treatment of Melanoma, Am J Clin Dermatol 18(1) (2017) 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Heo J, Reid T, Ruo L, Breitbach CJ, Rose S, Bloomston M, Cho M, Lim HY, Chung HC, Kim CW, Burke J, Lencioni R, Hickman T, Moon A, Lee YS, Kim MK, Daneshmand M, Dubois K, Longpre L, Ngo M, Rooney C, Bell JC, Rhee BG, Patt R, Hwang TH, Kirn DH, Randomized dose-finding clinical trial of oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccinia JX-594 in liver cancer, Nat Med 19(3) (2013) 329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Mullard A, Regulators approve the first cancer-killing virus, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 14 (2015) 811. [Google Scholar]

- [107].Raman SS, Hecht JR, Chan E, Talimogene laherparepvec: review of its mechanism of action and clinical efficacy and safety, Immunotherapy 11(8) (2019) 705–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Eriksson E, Milenova I, Wenthe J, Ståhle M, Leja-Jarblad J, Ullenhag G, Dimberg A, Moreno R, Alemany R, Loskog A, Shaping the Tumor Stroma and Sparking Immune Activation by CD40 and 4–1BB Signaling Induced by an Armed Oncolytic Virus, Clin Cancer Res 23(19) (2017) 5846–5857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]