This comparative effectiveness research study compares long-term quality-of-life outcomes in women with breast cancer after treatment with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy vs mastectomy and reconstruction without radiation therapy.

Key Points

Question

For patients with early breast cancer, what long-term quality-of-life outcomes are associated with treatment with breast-conserving surgery with radiation therapy (RT) compared with mastectomy and breast reconstruction without RT?

Findings

In this population-based comparative effectiveness research study of 647 women with breast cancer, patient-reported satisfaction with their breasts was similar 10 years after breast-conserving surgery with RT and with mastectomy and breast reconstruction without RT. However, psychosocial and sexual well-being were better in patients treated with breast-conserving surgery with RT.

Meaning

These findings may help inform preference-sensitive decision-making for women with early breast cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment options for early breast cancer include breast-conserving surgery with radiation therapy (RT) or mastectomy and breast reconstruction without RT. Despite marked differences in these treatment strategies, little is known with regard to their association with long-term quality of life (QOL).

Objective

To evaluate the association of treatment with breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT with long-term QOL.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This comparative effectiveness research study used data from the Texas Cancer Registry for women diagnosed with stage 0-II breast cancer and treated with breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy and reconstruction between 2006 and 2008. The study sample was mailed a survey between March 2017 and April 2018. Data were analyzed from August 1, 2018 to October 15, 2021.

Exposures

Breast-conserving surgery with RT or mastectomy and reconstruction without RT.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was satisfaction with breasts, measured with the BREAST-Q patient-reported outcome measure. Secondary outcomes included BREAST-Q physical well-being, psychosocial well-being, and sexual well-being; health utility, measured using the EuroQol Health-Related Quality of Life 5-Dimension, 3-Level questionnaire; and local therapy decisional regret. Multivariable linear regression models with weights for treatment, age, and race and ethnicity tested associations of the exposure with outcomes.

Results

Of 647 patients who responded to the survey (40.0%; 356 had undergone breast-conserving surgery, and 291 had undergone mastectomy and reconstruction), 551 (85.2%) confirmed treatment with breast-conserving surgery with RT (n = 315) or mastectomy and reconstruction without RT (n = 236). Among the 647 respondents, the median age was 53 years (range, 23-85 years) and the median time from diagnosis to survey was 10.3 years (range, 8.4-12.5 years). Multivariable analysis showed no significant difference between breast-conserving surgery with RT (referent) and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT in satisfaction with breasts (effect size, 2.71; 95% CI, –2.45 to 7.88; P = .30) or physical well-being (effect size, –1.80; 95% CI, –5.65 to 2.05; P = .36). In contrast, psychosocial well-being (effect size, –8.61; 95% CI, –13.26 to –3.95; P < .001) and sexual well-being (effect size, –10.68; 95% CI, –16.60 to –4.76; P < .001) were significantly worse with mastectomy and reconstruction without RT. Health utility (effect size, –0.003; 95% CI, –0.03 to 0.03; P = .83) and decisional regret (effect size, 1.32; 95% CI, –3.77 to 6.40; P = .61) did not differ by treatment group.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings support equivalence of breast-conserving surgery with RT and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT with regard to breast satisfaction and physical well-being. However, breast-conserving surgery with RT was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in psychosocial and sexual well-being. These findings may help inform preference-sensitive decision-making for women with early-stage breast cancer.

Introduction

Women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer may commonly choose between breast-conserving surgery with radiation therapy (RT) or mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction, typically without RT. Randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated similar recurrence and survival rates between individuals undergoing mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery with RT.1,2 Nevertheless, the long-term effects of these different treatment options on patient quality of life (QOL) have not been well studied. With rates of mastectomy and reconstruction for early-stage breast cancer increasing substantially in the US,3,4,5,6,7,8 with associated increased costs and complication burden,9 the need for patient-centered evidence to support the decision for breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT has become increasingly pressing.

Specific QOL outcomes relevant to the decision between breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT include satisfaction with breast cosmetic outcome and QOL across the spectrum of physical, psychosocial, and sexual well-being. However, few studies have compared breast-conserving surgery with RT and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT for these outcomes, particularly with long-term follow-up in the community setting.10 To fill this knowledge gap and support patient-centered decisions, we sought to compare long-term patient-reported outcomes after breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT using a population-based cohort selected from the Texas Cancer Registry (TCR).

Methods

Cohort Selection and Sampling

In this comparative effectiveness research study, we identified participants from the TCR with stage 0-II female breast cancer diagnosed between 2006 and 2008 who were alive in 2016, had a mailing address, and had undergone either breast-conserving surgery (n = 14 263) or mastectomy and reconstruction (n = 2070). The study was approved by the MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board and that of the Texas Department of State Health Services, and participants provided written informed consent. This study followed the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) reporting guideline.11

The cohort was stratified by TCR-coded race and ethnicity, based on patient demographic characteristics reported to the TCR by the treating hospital, and by age (<50, 50-64, or ≥65 years). The TCR race and ethnicity groups were classified as non-Hispanic Asian American/Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic of any race and ethnicity, and non-Hispanic White. We chose to sample up to 84 patients randomly selected for each unique combination of treatment, race and ethnicity, and age based on a power calculation that indicated that this study design would yield precision of ±4.3 points for outcome measurement, which is less than the threshold for clinically significant change in the BREAST-Q patient-reported outcome measure (estimated to be 8 points).12 This would permit measurement of an effect size between treatment groups of approximately 0.50, with 80% power and a 70% response rate. The final sample included 1616 patients (980 for breast-conserving surgery and 636 for mastectomy and reconstruction). Details regarding patient selection and sampling are provided in eTables 1-3 in the Supplement.

Study Measures

For this study, we adapted measures previously developed by members of our group for Medicare beneficiaries with a history of breast cancer.13,14,15,16 Measures were pilot tested with cognitive debriefing in 10 patients who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Individuals sampled for inclusion received a mailing between March 2017 and April 2018 that included a study invitation letter and consent statement, a $10 gift card, a paper survey comprising the study measures, and a postage-paid return envelope. Methods developed by Dillman17 were used to optimize response rates; these included both follow-up mailings and telephone calls when telephone numbers were available.

Study measures included the BREAST-Q12 mastectomy and reconstruction postoperative module or breast-conserving therapy postoperative module, the EuroQol Health-Related Quality of Life 5-Dimension, 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L)18 questionnaire, and the Decisional Regret Scale.19 The BREAST-Q evaluates the following QOL domains: satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial well-being, physical well-being, sexual well-being, and adverse effects of radiation.20 Satisfaction with breasts was selected a priori as the primary outcome measure for this study. Summary scores underwent Rasch transformation to yield a final score ranging from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a better QOL outcome; a minimum clinically significant change in scores was considered to be an absolute difference of 8 points.

The EQ-5D-3L index assesses mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety and depression, and it can be converted into an estimate of health utility using the US preference–based algorithm.18 Health utility ranges from −0.109 to 1, where 1 represents best possible health and 0 represents death; some health states are valued as worse than death, that is, less than 0. Important differences in EQ-5D scores were estimated to be 0.06 for US index scores.

The Decisional Regret Scale19 assessed regret regarding the decision for RT for patients in the breast-conserving surgery group and the decision for breast reconstruction for patients in the mastectomy and reconstruction group. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of regret regarding the decision to undergo the corresponding treatment.

Additional items assessed self-reported cancer treatment and type of breast reconstruction, brassiere cup size at diagnosis, height and weight at diagnosis, smoking history, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, and household income.

Classification of Breast-Conserving Surgery With RT vs Mastectomy and Reconstruction Groups

Before the survey mailing, treatment with breast-conserving surgery vs mastectomy and reconstruction was determined using treatment information reported by the TCR. However, because cancer treatment—radiation in particular—may be misclassified by the TCR,21 we confirmed treatment history by self-report to classify patients in the final treatment groups: breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT. Of the initial 356 respondents in the breast-conserving surgery group, we excluded 18 patients who denied history of breast-conserving surgery and 23 patients who denied receiving radiation during their initial treatment course, yielding 315 patients in the breast-conserving surgery with RT group for the final analysis. Of the initial 291 patients in the mastectomy and reconstruction group, all patients confirmed history of mastectomy but 15 were excluded because they denied prior reconstruction and 40 were excluded owing to self-reported radiation, yielding 236 patients in the mastectomy and reconstruction group for the final analysis. Patients who underwent mastectomy and reconstruction with radiation were excluded because radiation is rarely needed for early breast cancer after mastectomy and was expected to be associated with negative patient-reported outcomes in this patient group. As a result, of the 647 initial respondents, the treatment group was correctly confirmed for 551 (85.2%), who formed the analytic cohort for comparison of breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT.

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline patient and clinical characteristics by treatment group using the Rao-Scott χ2 goodness-of-fit test adjusted for weights from the sample design and for nonresponse rate (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Multivariable linear regression models with weights for sampling strata (treatment, age, and race and ethnicity) evaluated the association of treatment with each outcome. Candidate covariables included those from registry data (age at diagnosis, stage, tumor size, grade, number of breasts with cancer, node positivity, and estrogen receptor status) or self-report (baseline body mass index [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], brassiere cup size, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, income, educational attainment, and smoking history). Race and ethnicity were determined from self-report supplemented with TCR data and resulted in inclusion of American Indian/Alaska Native participants as a separate stratum. Backward selection retained variables with P < .10, and the treatment group was retained regardless of significance. For the primary outcome, we also tested interactions of age or race and ethnicity by treatment group. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) using 2-sided tests. The α value was divided between the primary and secondary outcomes, such that P < .025 was considered statistically significant for the test of association with treatment group and satisfaction with breasts (primary outcome) and P < .005 (0.025/5) was considered statistically significant for each of the 5 secondary outcomes. Data were analyzed from August 1, 2018, to October 15, 2021.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 647 of 1616 patients (40.0%) responded to the survey (356 had undergone breast-conserving surgery, and 291 had undergone mastectomy and reconstruction). Response rates varied by treatment group, age, race and ethnicity, and nodal status, with patients in the mastectomy and reconstruction group more likely to respond (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

The median age for all respondents was 53 years (range, 23-85 years); 7 respondents (1.1%) were American Indian/Alaska Native, 92 (14.2%) were Asian American/Pacific Islander, 144 (22.3%) were Black, 150 (23.2%) were Hispanic, and 254 (39.3%) were White. A total of 393 respondents (60.7% of the study sample) identified as racial and ethnic minorities. The interval from diagnosis to survey completion was 10.3 years (range, 8.4-12.5 years). The baseline characteristics presented in Table 1 show that mastectomy and reconstruction was more common in patients who were White, were younger, were node-positive, had larger tumors, had bilateral breast cancer, received chemotherapy, and had higher income. In the mastectomy and reconstruction group, 159 patients (54.6%) underwent bilateral mastectomy, and the types of reconstruction were implant (158 [54.3%]), abdominal (69 [23.7%]), latissimus (14 [4.8%]), and unknown (50 [17.2%]).

Table 1. Patient and Clinical Characteristics Among All Respondents by Texas Cancer Registry–Specified Treatment.

| Characteristic | Respondents, No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 647) | Breast-conserving surgery (n = 356) | Mastectomy and breast reconstruction (n = 291) | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| <50 | 257 (39.7) | 132 (37.1) | 125 (43.0) | .03 |

| 50-64 | 254 (39.3) | 136 (38.2) | 118 (40.5) | |

| ≥65 | 136 (21.0) | 88 (24.7) | 48 (16.5) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 7 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.7) | <.001 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 92 (14.2) | 77 (21.6) | 15 (5.2) | |

| Black | 144 (22.3) | 79 (22.2) | 65 (22.3) | |

| Hispanic | 150 (23.2) | 79 (22.2) | 71 (24.4) | |

| White | 254 (39.3) | 119 (33.4) | 135 (46.4) | |

| Baseline BMI | ||||

| 12.5-24.9 | 236 (36.5) | 131 (36.8) | 105 (36.1) | .61 |

| 25.0-29.9 | 186 (28.7) | 99 (27.8) | 87 (29.9) | |

| ≥30 | 147 (22.7) | 78 (21.9) | 69 (23.7) | |

| Unknown | 78 (12.1) | 48 (13.5) | 30 (10.3) | |

| Breasts with cancer, No. | ||||

| 1 | 538 (83.2) | 307 (86.2) | 231 (79.4) | .004 |

| 2 | 69 (10.7) | 25 (7.0) | 44 (15.1) | |

| Unknown | 40 (6.2) | 24 (6.7) | 16 (5.5) | |

| Brassiere cup size | ||||

| A or B | 170 (26.3) | 104 (29.2) | 66 (22.7) | .25 |

| C | 217 (33.5) | 113 (31.7) | 104 (35.7) | |

| D or greater | 165 (25.5) | 91 (25.6) | 74 (25.4) | |

| Unknown | 95 (14.7) | 48 (13.5) | 47 (16.2) | |

| Laterality | ||||

| Right | 307 (47.4) | 176 (49.4) | 131 (45.0) | .26 |

| Left | 340 (52.6) | 180 (50.6) | 160 (55.0) | |

| Grade | ||||

| Low | 109 (16.8) | 66 (18.5) | 43 (14.8) | .17 |

| Intermediate | 237 (36.6) | 137 (38.5) | 100 (34.4) | |

| High | 246 (38.0) | 128 (36.0) | 118 (40.5) | |

| Unknown | 55 (8.5) | 25 (7.0) | 30 (10.3) | |

| Nodal status | ||||

| Uninvolved (N0) | 458 (70.8) | 245 (68.8) | 213 (73.2) | <.001 |

| Involved (N+) | 92 (14.2) | 41 (11.5) | 51 (17.5) | |

| Unknown | 97 (15.0) | 70 (19.7) | 27 (9.3) | |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| 0-2 | 399 (61.7) | 238 (66.9) | 161 (55.3) | .002 |

| 2.1-4.9 | 138 (21.3) | 59 (16.6) | 79 (27.1) | |

| ≥5 | 22 (3.4) | 8 (2.2) | 14 (4.8) | |

| Unknown | 88 (13.6) | 51 (14.3) | 37 (12.7) | |

| SEER historic stage | ||||

| In situ | 187 (28.9) | 99 (27.8) | 88 (30.2) | .03 |

| Localized | 367 (56.7) | 216 (60.7) | 151 (51.9) | |

| Regional | 93 (14.4) | 41 (11.5) | 52 (17.9) | |

| Hormone therapy | ||||

| No | 198 (30.6) | 94 (26.4) | 104 (35.7) | .03 |

| Yes | 386 (59.7) | 224 (62.9) | 162 (55.7) | |

| Unknown | 63 (9.7) | 38 (10.7) | 25 (8.6) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 334 (51.6) | 199 (55.9) | 135 (46.4) | .04 |

| Yes | 267 (41.3) | 131 (36.8) | 136 (46.7) | |

| Unknown | 46 (7.1) | 26 (7.3) | 20 (6.9) | |

| Income, $ | ||||

| ≤40 000 | 201 (31.1) | 126 (35.4) | 75 (25.8) | <.001 |

| 40 001-80 000 | 171 (26.4) | 83 (23.3) | 88 (30.2) | |

| ≥80 001 | 210 (32.5) | 101 (28.4) | 109 (37.5) | |

| Unknown | 65 (10.0) | 46 (12.9) | 19 (6.5) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| High school or less | 138 (21.3) | 79 (22.2) | 59 (20.3) | .48 |

| Associate’s degree | 220 (34.0) | 119 (33.4) | 101 (34.7) | |

| College | 157 (24.3) | 86 (24.2) | 71 (24.4) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 103 (15.9) | 52 (14.6) | 51 (17.5) | |

| Unknown | 29 (4.5) | 20 (5.6) | 9 (3.1) | |

| Smoking history (lifetime) | ||||

| No | 452 (69.9) | 245 (68.8) | 207 (71.1) | .50 |

| Yes | 179 (27.7) | 100 (28.1) | 79 (27.1) | |

| Unknown | 16 (2.5) | 11 (3.1) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Current smoker (past 7 d) | ||||

| No | 593 (91.7) | 321 (90.2) | 272 (93.5) | .07 |

| Yes | 31 (4.8) | 17 (4.8) | 14 (4.8) | |

| Unknown | 23 (3.6) | 18 (5.1) | 5 (1.7) | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

BREAST-Q

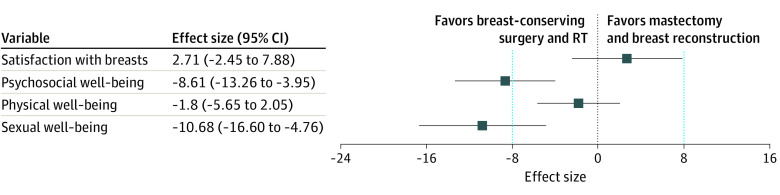

Of the 551 respondents who were treated with confirmed breast-conserving surgery with RT or mastectomy and reconstruction without RT according to their survey responses, BREAST-Q outcomes were scoreable for 542 respondents (98.4%) for satisfaction with breasts, 538 (97.6%) for psychosocial well-being, 543 (98.5%) for physical well-being, and 416 (75.5%) for sexual well-being. With breast-conserving surgery and RT as the referent, mastectomy and reconstruction without RT was not associated with a significant difference in satisfaction with breasts (effect size, 2.71; 95% CI, –2.45 to 7.88; P = .30) or physical well-being (effect size, –1.80; 95% CI, –5.65 to 2.05; P = .36). In contrast, psychosocial well-being (effect size, –8.61; 95% CI, –13.26 to –3.95; P < .001) and sexual well-being (effect size, –10.68; 95% CI, –16.60 to –4.76; P < .001) were significantly worse in patients treated with mastectomy and reconstruction without RT (Table 2, Figure). Interactions of race and ethnicity and age by treatment group were not significant for satisfaction with breasts.

Table 2. Linear Regression Weighted Models for BREAST-Q Outcomes.

| Respondents, No. | Effect size (SE) [95% CI] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with breasts (n = 542) | |||

| Intercept | NA | 53.7 (3.71) [46.43 to 60.96] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 308 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 234 | 2.64 (–2.45 to 7.88) | .30 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | –19.27 (6.50) [–32.01 to –6.54] | .003 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 74 | 1.53 (3.57) [–5.47 to 8.53] | .67 |

| Black | 126 | 4.16 (3.09) [–1.91 to 10.22] | .18 |

| Hispanic | 122 | 2.15 (3.27) [–4.25 to 8.56] | .51 |

| White | 215 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 218 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 50-64 | 208 | 1.89 (2.82) [–3.64 to 7.41] | .50 |

| ≥65 | 116 | 8.66 (3.98) [0.85 to 16.47] | .03 |

| Brassiere cup size | |||

| A or B | 148 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| C | 192 | 7.68 (3.45) [0.92 to 14.44] | .03 |

| D or greater | 153 | 5.70 (4.08) [–2.30 to 13.69] | .16 |

| Unknown | 49 | –7.19 (5.23) [–17.43 to 3.06] | .17 |

| Psychosocial well-being (n = 538) | |||

| Intercept | NA | 74.07 (4.30) [65.64 to 82.5] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 305 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 233 | –8.61 (2.37) [–13.26 to –3.95] | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | –21.35 (4.29) [–29.75 to –12.95] | <.001 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 73 | –1.35 (4.24) [–9.67 to 6.97] | .75 |

| Black | 125 | 1.11 (3.09) [–4.94 to 7.17] | .72 |

| Hispanic | 121 | –4.23 (3.18) [–10.46 to 1.99] | .18 |

| White | 214 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Brassiere cup size | |||

| A or B | 147 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| C | 190 | 8.8 (2.82) [3.27 to 14.33] | .002 |

| D or greater | 152 | 1.16 (3.87) [–6.42 to 8.74] | .76 |

| Unknown | 49 | –8.19 (5.04) [–18.07 to 1.69] | .10 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 308 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Yes | 223 | –3.47 (2.37) [–8.11 to 1.17] | .14 |

| Unknown | 7 | 16.83 (7.56) [2.02 to 31.63] | .03 |

| Income, $ | |||

| ≤40 000 | 160 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 40 001-80 000 | 149 | 10.45 (3.88) [2.84 to 18.06] | .007 |

| ≥80 001 | 178 | 8.17 (3.74) [0.85 to 15.49] | .03 |

| Physical well-being (n = 543) | |||

| Intercept | NA | 72.11 (3.97) [64.33 to 79.9] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 309 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 234 | –1.80 (1.96) [–5.65 to 2.05] | .36 |

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 218 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 50-64 | 209 | 0.94 (2.21) [–3.39 to 5.26] | .67 |

| ≥65 | 116 | 10.07 (2.50) [5.17 to 14.97] | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | –30.02 (6.90) [–43.56 to –16.49] | <.001 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 75 | –9.29 (4.42) [–17.96 to –0.63] | .04 |

| Black | 126 | 0.29 (2.23) [–4.08 to 4.66] | .90 |

| Hispanic | 122 | –4.57 (2.32) [–9.11 to –0.03] | .049 |

| White | 215 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Educational level | |||

| High school or less | 106 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Associate’s degree | 191 | 4.74 (3.25) [–1.63 to 11.1] | .15 |

| College | 134 | 11.69 (3.50) [4.84 to 18.54] | <.001 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 88 | 7.62 (3.51) [0.75 to 14.49] | .03 |

| Unknown | 24 | 6.65 (4.04) [–1.26 to 14.56] | .10 |

| Sexual well-being (n = 416) | |||

| Intercept | NA | 51.66 (5.59) [40.71 to 62.61] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 214 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 202 | –10.68 (3.02) [–16.60 to –4.76] | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | –25.39 (9.29) [–43.59 to –7.19] | .007 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 52 | 3.46 (5.15) [–6.64 to 13.55] | .50 |

| Black | 94 | 2.47 (3.53) [–4.44 to 9.38] | .48 |

| Hispanic | 92 | –4.93 (3.98) [–12.73 to 2.88] | .22 |

| White | 173 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Brassiere cup size | |||

| A or B | 104 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| C | 151 | 8.03 (4.15) [–0.12 to 16.17] | .05 |

| D or greater | 125 | 6.00 (4.34) [–2.51 to 14.52] | .17 |

| Unknown | 36 | –9.29 (7.78) [–24.54 to 5.95] | .23 |

| Income, $ | |||

| ≤40 000 | 98 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 40 001-80 000 | 117 | 9.58 (4.78) [0.22 to 18.94] | .045 |

| ≥80 001 | 165 | 5.78 (4.55) [–3.14 to 14.71] | .20 |

| Unknown | 36 | 5.59 (6.41) [–6.97 to 18.15] | .38 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NA, not applicable; RT, radiation therapy.

Figure. Adjusted Association of Breast-Conserving Surgery With Radiation Therapy (RT) vs Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction Without RT With BREAST-Q Outcomes.

Data are derived from adjusted linear regression models in Table 2. Markers represent effect sizes; error bars, 95% CIs; and vertical dashed lines, clinically significant difference in BREAST-Q score.

Compared with individuals who identified as White (n = 215), physical well-being was worse among those who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 5; effect size, –30.02; 95% CI, –43.56 to –16.49; P < .001), Asian American/Pacific Islander (n = 75; effect size, –9.29; 95% CI, –17.96 to –0.63; P = .04), and Hispanic (n = 122; effect size, –4.57; 95% CI, –9.11 to –0.03; P = .049). Individuals who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 5) experienced worse satisfaction with breasts (effect size, –19.27; 95% CI, –32.01 to –6.54; P = .003), psychosocial well-being (effect size, –21.35; 95% CI, –29.75 to –12.95; P < .001), and sexual well-being (effect size, –25.39; 95% CI, –43.59 to –7.19; P = .007).

In addition, a brassiere cup size of C compared with A or B was associated with improvements in satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being but not with better sexual well-being. Higher income ($40 001 or greater) was associated with better psychosocial well-being and sexual well-being, and educational attainment of a college degree or higher was associated with better physical well-being (Table 2). In addition, age 65 years or older compared with 18 to 49 years was associated with better satisfaction with breasts and physical well-being.

Health Utility

Of 551 respondents with confirmed treatment, health utility was assessed for 510 (92.6%). With breast-conserving surgery with RT as the referent (n = 288), mastectomy and reconstruction without RT was not associated with a significant difference in health utility (n = 222; effect size, –0.003; 95% CI, –0.03 to 0.03; P = .83). Compared with individuals who identified as White (n = 209), those who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native experienced worse health utility (n = 5; effect size, –0.22; 95% CI, –0.37 to –0.07; P = .005). Compared with patients with a low or normal baseline body mass index (n = 161), individuals with a baseline body mass index indicating obesity (≥30) experienced worse health utility (n = 34; effect size, –0.05; 95% CI, –0.09 to –0.01; P = .02). With a yearly household income of $40 000 or less as the referent (n = 146), there was no association between an income of $80 001 or more and better health utility (n = 47; effect size, 0.04; 95% CI, 0.00-0.08; P = .05) (Table 3).

Table 3. Linear Regression Weighted Model of EQ-5D-3L Health Utility Outcomes.

| Respondents, No. (N = 510) | Effect size (SE) [95% CI] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | NA | 0.87 (0.02) [0.83 to 0.91] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 288 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 222 | –0.003 (0.02) [–0.03 to 0.03] | .83 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | –0.22 (0.08) [–0.37 to –0.07] | .005 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 71 | 0.001 (0.02) [–0.04 to 0.04] | .97 |

| Black | 113 | 0.002 (0.02) [–0.04 to 0.04] | .92 |

| Hispanic | 112 | –0.03 (0.02) [–0.07 to 0.01] | .09 |

| White | 209 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Baseline BMI | |||

| 12.5-24.9 | 161 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 25.0-29.9 | 122 | –0.02 (0.02) [–0.06 to 0.01] | .25 |

| ≥30 | 34 | –0.05 (0.02) [–0.09 to –0.01] | .02 |

| Patient-reported income, $ | |||

| ≤40 000 | 146 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 40 001-80 000 | 144 | 0.04 (0.02) [–0.01 to 0.08] | .11 |

| ≥80 001 | 47 | 0.04 (0.02) [0.00 to 0.08] | .05 |

| Unknown | 47 | 0.07 (0.02) [0.03 to 0.12] | .003 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast-conserving surgery; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol Health-Related Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level questionnaire; NA, not applicable; RT, radiation therapy.

Decisional Regret

Of 551 respondents with confirmed treatment, decisional regret was assessed for 534 (96.9%). With breast-conserving surgery with RT as the reference category (n = 302), mastectomy and reconstruction without RT was not associated with a significant difference in decisional regret (n = 232; effect size, 1.32; 95% CI, –3.77 to 6.40; P = .61). Individuals who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native experienced worse decisional regret (n = 5; effect size, 15.66; 95% CI, 0.33-30.98; P = .046). No other sociodemographic factors were associated with regret (Table 4).

Table 4. Linear Regression Weighted Model of Local Therapy Decisional Regret.

| Characteristic | Respondents, No. (N = 534) | Effect size (SE) [95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | NA | 11.36 (3.41) [4.68 to 18.04] | <.001 |

| Treatment | |||

| BCS with RT | 302 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Mastectomy and breast reconstruction | 232 | 1.32 (2.59) [–3.77 to 6.40] | .61 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | 15.66 (7.82) [0.33 to 30.98] | .046 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 74 | 9.73 (7.10) [–4.18 to 23.64] | .17 |

| Black | 124 | 2.06 (2.42) [–2.69 to 6.81] | .40 |

| Hispanic | 119 | 5.44 (3.00) [–0.44 to 11.32] | .07 |

| White | 212 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Grade | |||

| Low | 93 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Intermediate | 201 | 1.52 (3.33) [–5.00 to 8.04] | .65 |

| High | 198 | 9.28 (3.86) [1.72 to 16.85] | .02 |

| Unknown | 42 | 4.20 (4.75) [–5.12 to 13.52] | .38 |

| Tumor size, cm | |||

| 0-2 | 335 | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2.1-4.9 | 115 | –2.76 (3.10) [–8.84 to 3.33] | .37 |

| ≥5 | 16 | –11.87 (4.64) [–20.97 to –2.77] | .01 |

| Unknown | 68 | –5.98 (4.32) [–14.44 to 2.48] | .17 |

Abbreviations: BCS, breast-conserving surgery; NA, not applicable; RT, radiation therapy.

Discussion

Breast cancer treatment is uniquely personal, and in early stages, local-regional treatment options of breast-conserving surgery with RT or mastectomy without RT are considered oncologically equivalent.1,2 However, the physical, aesthetic, and psychological outcomes associated with these different treatment options are less defined. This population-based study of patients with breast cancer in Texas showed similar long-term satisfaction with breasts and physical well-being after breast-conserving surgery with RT compared with mastectomy and reconstruction without RT but clinically significant differences (>8 points on the BREAST-Q) in psychosocial and sexual well-being that favored breast-conserving surgery with RT. Furthermore, the findings indicated that the burden of poor long-term QOL outcomes was greater among younger individuals, those with lower educational attainment and income, and certain racial and ethnic minority populations. These findings suggest that opportunities exist to enhance equity in the long-term QOL of individuals with breast cancer.

During the past 2 decades, a considerable increase in the use of mastectomy and reconstruction has been observed in patients who have been eligible for breast-conserving surgery. For example, Kummerow et al8 reported a 34% increase in the odds of mastectomy nationwide from 2004 to 2011 among patients eligible for breast-conserving surgery. Similar findings were reported from patients treated at the University of Michigan.22 Using data from private payers, members of our group found that patients who underwent mastectomy and reconstruction without RT experienced nearly twice the complication risk of patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery with RT, with an excess total cost of $22 481 and an excess complication-related cost of $9017.9 Similar excess complications associated with mastectomy and reconstruction were noted in a review of National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.23 Mamtani and Morrow24 summarized the increasing use of mastectomy and reconstruction, concluding that the increase was associated with patient fears of cancer recurrence and misunderstanding of future cancer risks.

Because of the increasing use of mastectomy and reconstruction, it has become important to evaluate patient-reported outcomes after breast-conserving surgery with RT vs mastectomy and reconstruction without RT. Jagsi and colleagues10 conducted a longitudinal, population-based assessment of QOL outcomes by surgical treatment approach in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of patients recruited from the Detroit and Los Angeles tumor registries. Using an outcome measure developed for the study to assess satisfaction with breast cosmesis, the authors concluded that satisfaction was similar for patients treated with breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy with reconstruction through 4 years of follow-up. Among patients treated with mastectomy, satisfaction was higher after autologous reconstruction than after implant reconstruction and lower after radiation. Our study’s findings are consistent with those findings; using the validated BREAST-Q measure, we showed that both satisfaction with breasts and physical well-being remained similar after breast-conserving surgery with RT and after mastectomy and reconstruction without RT through 10 years after diagnosis. In contrast, our finding that sexual and psychosocial well-being was better after breast-conserving surgery with RT provides novel information that could equip patients to make a more nuanced and informed treatment decision.

In recent years, several groups have reported cohort studies from academic centers evaluating QOL outcomes after local therapy for breast cancer. Flanagan and colleagues25 retrospectively evaluated 3233 women and found that treatment with breast-conserving surgery was associated with improvements in all 4 BREAST-Q outcomes compared with mastectomy with implant reconstruction, whereas treatment with radiation was associated with a decrement in all 4 BREAST-Q outcomes. Rosenberg et al26 conducted a prospective, multicenter study of 826 patients aged 40 years or younger and found that those who underwent mastectomy experienced worse body image and sexuality that persisted for 5 years. Lim and colleagues27 prospectively evaluated 475 patients with unilateral breast cancer and reported that patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery experienced better satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being than did those who underwent mastectomy. In addition, Pesce et al28 prospectively studied 203 women, reporting that treatment with breast-conserving surgery was associated with improved satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial well-being compared with bilateral mastectomy through 15 months. However, these studies may have overestimated the benefits associated with breast-conserving surgery with RT compared with mastectomy and reconstruction without RT because they included some patients treated with breast-conserving surgery without RT, which was associated with improved breast-conserving surgery QOL outcomes. The studies also included some patients treated with mastectomy without reconstruction and/or with radiation, both of which are associated with worse QOL outcomes.16 In contrast, our approach provided a direct comparison of the 2 most common treatment strategies between which patients select preoperatively when meeting with their surgical team: breast-conserving surgery with RT and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT.

In addition, the population-based nature of our study coupled with our sampling approach that resulted in a 60.7% racial and ethnic minority population enhanced the external validity of our findings to community care. Of note, racial and ethnic disparities were not pervasive but were limited to individuals who self-identified as Asian American/Pacific Islander or Hispanic for the outcome of physical well-being. Similar to Jagsi et al,10 we found that individuals who identified as Asian American/Pacific Islander, Black, or Hispanic did not experience significant long-term disparities in other outcome measures. In contrast, those who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native experienced pervasive decrements in QOL across all outcome measures. This finding should be interpreted with caution owing to small numbers but is noteworthy considering that little is known regarding outcome disparities in this group. Prior research has shown that those who identify as American Indian/Alaska Native experience considerable health disparities29,30 and, specific to breast cancer, are more likely than White patients to present for treatment with advanced-stage breast cancer31 and less likely to undergo breast-conserving surgery.32 Future work is needed to understand the barriers to quality cancer care experienced by Indigenous people to develop mitigation strategies.

Our findings that higher income levels were associated with better psychosocial well-being and sexual well-being and that higher educational attainment was associated with better physical well-being suggest that social factors beyond race and ethnicity may also be associated with long-term QOL outcomes in individuals with breast cancer. These findings are consistent with the associations of low income with less satisfaction reported by Mundy et al33 in a convenience sample of 1201 patients drawn from the online community “Army of Women” and also by Jagsi et al.10

A novel contribution of this study is the description of long-term health utility, which may be helpful in future cost-effectiveness analyses. In addition, our finding of a lack of significant difference in long-term decisional regret between breast-conserving surgery with RT and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT suggests that the specific differences in psychosocial and sexual well-being by treatment did not translate into an overall higher burden of regret associated with mastectomy and reconstruction without RT, consistent with findings from a prior study by members of our group, in which local therapy was not associated with regret in older Medicare beneficiaries with breast cancer.15

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although the study was unique in its population-based sampling and sample stratified by age and race and ethnicity, the response rate may limit broader generalizability. In addition, there were differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of age, race and ethnicity, and treatment group; however, there were no significant differences in key clinical characteristics (stage, tumor size, and grade). Another limitation is the single time point of survey capture, which likely represents long-term, stable outcomes but may not reflect earlier outcomes and did not consider pretreatment baseline. The sample size also did not permit a detailed comparison of breast-conserving surgery and RT with different types of breast reconstruction; type of breast reconstruction may be associated with long-term QOL outcomes.10,34 Similarly, the study was not designed to compare different types of radiation after breast-conserving surgery, and it is reasonable to speculate that new approaches to partial breast irradiation, more widespread use of whole-breast hypofractionation, or omission of boost in appropriate patients may be associated with better QOL outcomes after breast-conserving surgery and RT than were reported in this study.35,36

Conclusions

In this population-based comparative effectiveness research study of long-term QOL outcomes in individuals with breast cancer, the findings supported equivalence of breast-conserving surgery with RT and mastectomy and reconstruction without RT with respect to breast satisfaction and physical well-being but suggested there may be clinically meaningful improvements in psychosocial and sexual well-being associated with breast-conserving surgery with RT. These findings may inform preference-sensitive decision-making for women with early-stage breast cancer.

eTable 1. Cohort Creation

eTable 2. Age and Race and Ethnicity of Treatment Cohorts Prior to Sampling

eTable 3. Age and Race and Ethnicity of Treatment Cohorts After Sampling

eTable 4. Number of Respondents by Age and Race and Ethnicity

eTable 5. Patient and Clinical Characteristics by Response

References

- 1.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233-1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. ; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2087-2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271-289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheepens JCC, Veer LV, Esserman L, Belkora J, Mukhtar RA. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a narrative review of the evidence and acceptability. Breast. 2021;56:61-69. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santosa KB, Oliver JD, Momoh AO. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and implications for breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2021;10(1):498-506. doi: 10.21037/gs.2020.03.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albornoz CR, Matros E, Lee CN, et al. Bilateral mastectomy versus breast-conserving surgery for early-stage breast cancer: the role of breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(6):1518-1526. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kummerow KL, Du L, Penson DF, Shyr Y, Hooks MA. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):9-16. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith BD, Jiang J, Shih YC, et al. Cost and complications of local therapies for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;109(1). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagsi R, Li Y, Morrow M, et al. Patient-reported quality of life and satisfaction with cosmetic outcomes after breast conservation and mastectomy with and without reconstruction: results of a survey of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1198-1206. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger ML, Mamdani M, Atkins D, Johnson ML. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: defining, reporting and interpreting nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources: the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Retrospective Database Analysis Task Force Report—Part I. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1044-1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano SJ, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL. The BREAST-Q: further validation in independent clinical samples. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(2):293-302. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aec6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BD, Lei X, Diao K, et al. Effect of surgeon factors on long-term patient-reported outcomes after breast-conserving therapy in older breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(4):1013-1022. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08165-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karuturi MS, Lei X, Shen Y, Giordano SH, Swanick CW, Smith BD. Long-term decision regret surrounding systemic therapy in older breast cancer survivors: a population-based survey study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):973-979. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Advani PG, Lei X, Swanick CW, et al. Local therapy decisional regret in older women with breast cancer: a population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104(2):383-391. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.01.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanick CW, Lei X, Xu Y, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes in older breast cancer survivors: a population-based survey study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(4):882-890. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.11.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43(3):203-220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281-292. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345-353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker GV, Giordano SH, Williams M, et al. Muddy water? variation in reporting receipt of breast cancer radiation therapy by population-based tumor registries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):686-693. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabel MS, Kraft CT, Griffith KA, et al. Differences between breast conservation-eligible patients and unilateral mastectomy patients in choosing contralateral prophylactic mastectomies. Breast J. 2016;22(6):607-615. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyfer B, Chatterjee A, Chen L, et al. Early postoperative outcomes in breast conservation surgery versus simple mastectomy with implant reconstruction: a NSQIP analysis of 11,645 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(1):92-98. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4770-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamtani A, Morrow M. Why are there so many mastectomies in the United States? Annu Rev Med. 2017;68:229-241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043015-075227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flanagan MR, Zabor EC, Romanoff A, et al. A comparison of patient-reported outcomes after breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy with implant breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3133-3140. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07548-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberg SM, Dominici LS, Gelber S, et al. Association of breast cancer surgery with quality of life and psychosocial well-being in young breast cancer survivors. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(11):1035-1042. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim DW, Retrouvey H, Kerrebijn I, et al. Longitudinal study of psychosocial outcomes following surgery in women with unilateral nonhereditary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(11):5985-5998. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-09928-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pesce C, Jaffe J, Kuchta K, Yao K, Sisco M. Patient-reported outcomes among women with unilateral breast cancer undergoing breast conservation versus single or double mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185(2):359-369. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05964-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heck JL, Jones EJ, Bohn D, et al. Maternal mortality among American Indian/Alaska Native women: a scoping review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(2):220-229. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutchinson RN, Shin S. Systematic review of health disparities for cardiovascular diseases and associated factors among American Indian and Alaska Native populations. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e80973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wingo PA, King J, Swan J, et al. Breast cancer incidence among American Indian and Alaska Native women: US, 1999-2004. Cancer. 2008;113(5)(suppl):1191-1202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erdrich J, Cordova-Marks F, Monetathchi AR, Wu M, White A, Melkonian S. Disparities in breast-conserving therapy for non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native women compared with non-Hispanic White women. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-10788-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mundy LR, Homa K, Klassen AF, Pusic AL, Kerrigan CL. Breast cancer and reconstruction: normative data for interpreting the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(5):1046e-1055e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santosa KB, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Wilkins EG, Pusic AL. Long-term patient-reported outcomes in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(10):891-899. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coles CE, Griffin CL, Kirby AM, et al. ; IMPORT Trialists . Partial-breast radiotherapy after breast conservation surgery for patients with early breast cancer (UK IMPORT LOW trial): 5-year results from a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10099):1048-1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31145-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haviland JS, Owen JR, Dewar JA, et al. ; START Trialists’ Group . The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) trials of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: 10-year follow-up results of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(11):1086-1094. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70386-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Cohort Creation

eTable 2. Age and Race and Ethnicity of Treatment Cohorts Prior to Sampling

eTable 3. Age and Race and Ethnicity of Treatment Cohorts After Sampling

eTable 4. Number of Respondents by Age and Race and Ethnicity

eTable 5. Patient and Clinical Characteristics by Response