Abstract

Introduction:

Clopidogrel is the most frequently utilized P2Y12 inhibitor and is characterized by broad interindividual response variability resulting in impaired platelet inhibition and increased risk of thrombotic complications in a considerable number of patients. The potent P2Y12 inhibitors, prasugrel and ticagrelor, can overcome this limitation but at the expense of an increased risk of bleeding. Genetic variations of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 enzyme, a key determinant in clopidogrel metabolism, have been strongly associated with clopidogrel response profiles prompting investigations of genetic-guided selection of antiplatelet therapy.

Areas covered:

The present manuscript focuses on the rationale for the use of genetic testing to guide the selection of platelet P2Y12 inhibitors among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Moreover, a comprehensive appraisal of the available evidence and practical recommendations are provided.

Expert Commentary:

Implementation of genetic testing as a strategy to guide the selection of therapy can result into escalation (i.e., switching to prasugrel or ticagrelor) or de-escalation (i.e., switching to clopidogrel) of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy. Most recent investigations support the clinical benefit of a genetic guided selection of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergo PCI. Integrating the results of genetic testing with clinical and procedural variables represents a promising strategy for a precision medicine approach for the selection of antiplatelet therapy among patients undergoing PCI.

Keywords: genetics, antiplatelet therapy, bleeding, thrombosis, percutaneous coronary intervention, P2Y12 inhibitors

1. Introduction

The use of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), consisting of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, represents the standard of care for the prevention of systemic ischemic events [i.e., cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke] as well as local stent-related thrombotic complications [i.e. stent thrombosis (ST)] in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1, 2, 3, 4]. The antithrombotic efficacy of DAPT is attributed to the synergistic effect of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor on blocking two key platelet signaling pathways [5]. In particular, aspirin is an irreversible inhibitor of the cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme and a number of oral agents (i.e., ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor), characterized by different pharmacologic profiles, have been developed to inhibit the adenosine diphosphate (ADP) P2Y12 receptor subtype [6].

Clopidogrel is the most commonly used P2Y12 inhibitor, as it is considered the antiplatelet agent of choice among patients with chronic coronary syndromes (CCS) undergoing PCI, but it is also approved for use in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS)]. [3]. This is due to multiple factors, including its established efficacy, favorable safety profile, low costs and broad indication for use. Despite the proven efficacy of clopidogrel, pharmacodynamic studies have shown interpatient variability in response profiles with 20% to 40% of patients persisting with high platelet reactivity (HPR), a marker of thrombotic risk in patients undergoing PCI [7]. Conversely, prasugrel and ticagrelor are potent P2Y12 inhibitors with more predictable antiplatelet effects and very low rates of HPR [8]. In the absence of contraindications, these agents are recommended over clopidogrel in patients with ACS in light of their superior antithrombotic efficacy [1, 2, 4]. However, such benefit occurs at the expense of an increased risk of bleeding. Importantly, bleeding complications carry prognostic implications, including increased mortality, similar or worse than a recurrent thrombotic event [9, 10].

The availability of several oral P2Y12 inhibitors characterized by different pharmacologic, safety and efficacy profiles have prompted research aimed at individualizing the selection of agent [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. In particular, studies of tailored selection of an oral P2Y12 inhibitor have been conducted with the goal of balancing safety and efficacy outcomes in patients undergoing PCI [7, 8, 19, 20]. Platelet function and genetic tests have represented tools to assist with such individualized selection of agent. However, most recent evidence suggests the use of genetic testing as a more promising tool to be implemented in clinical practice [7]. In this manuscript we provide an overview on the pharmacology of oral P2Y12 inhibitors, the rationale for implementing genetic testing in patients undergoing PCI, and describe the available evidence and recommendations on the use of genetic testing to assist with the selection of oral P2Y12 inhibition in clinical practice.

2. Oral P2Y12 inhibitors

Mechanism of action and pharmacologic profiles

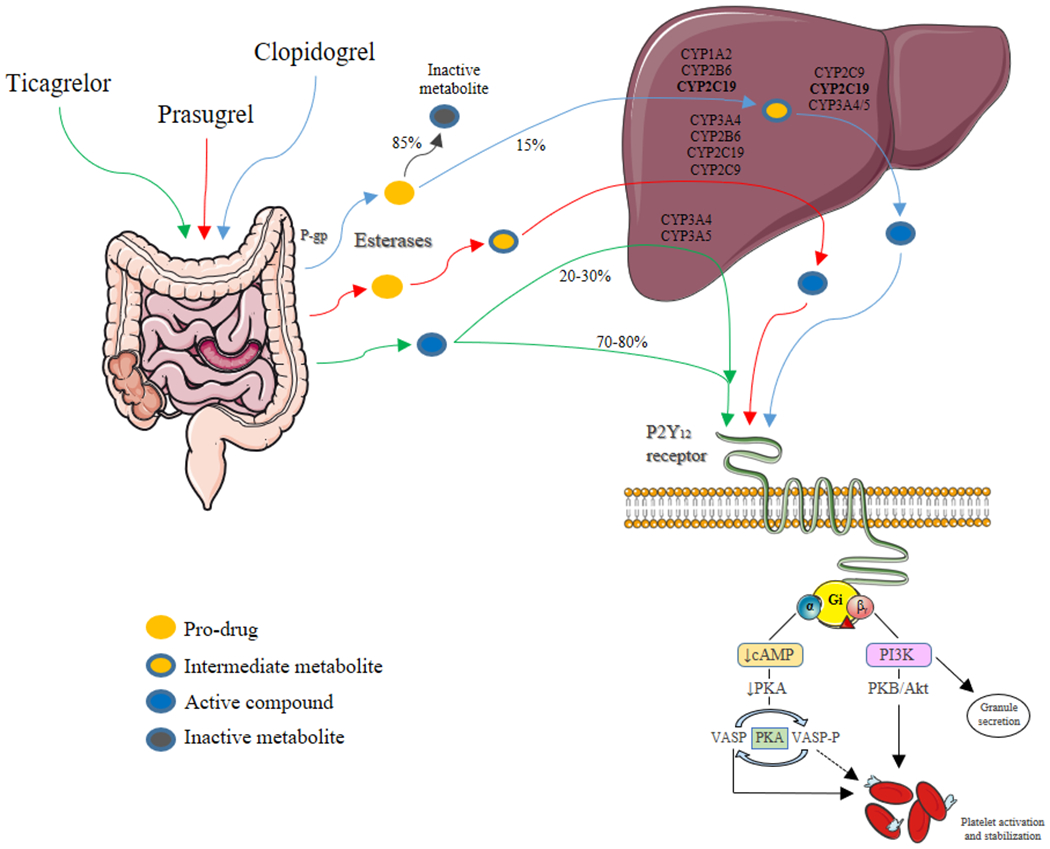

Thienopyridines (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel) are prodrugs that require hepatic metabolism to generate an active metabolite that irreversibly binds the P2Y12 receptor. Ticlopidine is a first generation thienopyridine but is no longer recommended for use because of its unfavorable safety profile and will not be discussed [21]. Clopidogrel is a second generation thienopyridine whose intestinal absorption is regulated by the efflux pump P-glycoprotein (P-gp). The majority (85%) of clopidogrel pro-drug is inactivated by esterases in the blood and only 15% of the pro-drug is available for transformation into an active metabolite after a 2-step biotransformation oxidative process by the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) system [19, 22, 23]. Formation of the active metabolite is catalyzed by various CYP enzymes with CYP1A2, CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 contributing to the first and CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4/5 to the second step of the oxidative process. Importantly, CYP2C19 is involved in both steps, making genetic variants affecting the function of this enzyme of interest [23] (Figure 1). In particular, although multiple mechanisms have shown to contribute to clopidogrel response variability, genetic polymorphisms of the CYP2C19 enzyme have shown to have a relevant role [7, 19, 24]. More specifically, carrier status for loss-of-function (LoF) alleles (also called no function alleles) of the CYP2C19 enzyme is associated with reduced generation of clopidogrel’s active metabolite and impaired platelet inhibition leading to increased HPR rates and enhanced risk of thrombotic complications in patients undergoing PCI [24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Clopidogrel’s onset and offset of action are 2 to 8 hours and 7 to 10 days, respectively [6].

Figure 1: Mechanisms of action of oral platelet P2Y12 inhibitors.

P2Y12 is a chemoreceptor for adenosine diphosphate that belongs to the Gi class of a group of G protein-coupled purinergic receptors. The G protein’s α subunit, causes a decrease in cAMP and PKA that leads to an increase of VASP and a decrease of VASP-P levels. VASP stimulates and VASP-P inhibits platelet activation and stabilization. G protein’s β subunit increases PI3K that promotes granule secretion and increases PKB/akt resulting in platelet activation and stabilization. Thus, inhibition of the P2Y12 receptor suppresses platelet activation. Three oral platelet P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor) are primarily used in clinical practice. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in an efflux pump that can return some of the thienopyridine compound to the intestinal lumen. After intestinal absorption, 85% of the oral prodrug clopidogrel is hydrolyzed in the blood and liver by esterases (carboxylase) to an inactive metabolite while the remaining 15% is converted to the active metabolite by hepatic CYP isoenzymes, through a two-step oxidation process. By contrast, esterases are part of prasugrel’s activation pathway, and prasugrel is oxidized more efficiently to its active metabolite via a single CYP- dependent step. Ticagrelor is a direct acting agent which reversibly inhibits platelet activation by allosteric modulation of the P2Y12 receptor; 20-30% of ticagrelor induced antiplatelet effects are attributed to a CYP-derived compound with similar potency compared to the parent drug.

Abbreviations: AC: adenylyl cyclase; CYP: cytochrome P450; gp: glycoprotein; PKA: protein kinase A; VASP: vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein; P: phosphorylated; PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKB/akt: protein kinase B.

Prasugrel is a third generation thienopyridine characterized by a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile than clopidogrel. Indeed, after intestinal absorption regulated by P-gp, prasugrel is hydrolyzed by intestinal esterases into an intermediate metabolite (thiolactone) that only requires a single-step hepatic metabolism, primarily by CYP3A4 and CYP2B6, with a minor role of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9, to generate its active metabolite [22, 29]. Importantly, most of prasugrel pro-drug is converted into its active metabolite [22] (Figure 1). The active metabolites of prasugrel and clopidogrel are equipotent, but since much more is generated (i.e., 5-6 fold higher) with prasugrel, a greater degree of platelet inhibition is achieved. Prasugrel’s onset and offset of action are 30 minutes to 4 hours and 7 to 10 days, respectively [6].

Ticagrelor is a cyclopentyltriazolopyrimidine (CPTP) rapidly absorbed in the intestine and is a direct acting agent (i.e., does not require further biotransformation for activation) with reversible binding to the P2Y12 receptor [30]. However, 30% of the antiplatelet effects induced by ticagrelor derive from metabolites, mainly ARC124910XX, generated by the hepatic CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 enzymes. Both the parent drug and the active metabolite have similar potency [30, 31] (Figure 1). Moreover, in addition to inhibiting the P2Y12 receptor, ticagrelor, but not its metabolites, increases local endogenous adenosine levels by inhibiting reuptake mediated by the equilibrated nucleoside transporter-1 (ENT-1) on red blood cells and platelets [32]. While such off-target effects of ticagrelor can contribute to its benefits, it may explain some of its non-bleeding side effects (i.e., dyspnea and atrioventricular conduction abnormalities) [32, 33]. Ticagrelor’s onset and offset of action are 30 minutes to 4 hours and 3 to 5 days, respectively. Since its half-life is 7 to 8 hours [6], a bis-in-die (BID) administration is required.

Key clinical outcomes trials of oral P2Y12 inhibitors

A large number of trials have been conducted over the past two decades supporting the benefit of oral P2Y12 inhibitors in patients presenting with an ACS or undergoing PCI [34, 35]. A detailed description of these trials goes beyond the scope of this manuscript. Key trials are briefly described in this section.

Following early studies supporting the concept of adding a P2Y12 inhibitor (i.e., ticlopidine) to aspirin as the most effective strategy to reduce early thrombotic complications, numerous investigations where conducted with clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor. Clopidogrel was approved following the results of the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial which showed a significant reduction (relative risk 0.80, 95 % CI 0.72-0.90) of the primary endpoint (composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke) among patients (n=6259) with unstable angina (UA)/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) who received clopidogrel (300 mg immediately, followed by 75 mg once daily) in addition to aspirin for 3 to 12 months as compared to placebo plus aspirin [36]. A number of other trials conducted in different CAD settings confirmed the benefit of adjunctive treatment with clopidogrel [37, 38, 39]. Accordingly, clopidogrel has been extensively used for both patients with CCS and ACS and is currently the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice in CCS patients undergoing PCI. However, despite the ischemic benefits achieved with clopidogrel treatment, ischemic recurrences and thrombotic complications remain elevated particularly in high-risk patients such as those with ACS. These observations are attributed, at least in part, to impaired clopidogrel response leading to HPR. Importantly, a number of studies have consistently shown on-clopidogrel-HPR to be associated with thrombotic complications in the setting of PCI [40, 41]. These observations have led to the development of the more potent oral P2Y12 inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor [42, 43].

The Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON–TIMI) 38 trial randomized 13,608 patients with ACS [UA, NSTEMI and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)] who were scheduled to undergo PCI to receive either prasugrel (60 mg loading dose followed by 10 mg daily maintenance dose) or clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily maintenance dose) in addition to aspirin and were followed up for a median of 14.5 months [43]. Compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel significantly reduced the rate of the primary efficacy composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (9.9% versus 12.1%; hazard ratio, HR, 0.81, 95% CI 0.73-0.90), driven by a reduction in non-fatal MI. Moreover, prasugrel was associated with a significant 52% reduction in the rate of stent thrombosis [43]. However, prasugrel was also associated with a significant 32% increase in non-CABG related Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major bleeding and a four-fold higher risk of fatal bleeding as compared to clopidogrel. Such increased risk of bleeding offset the benefits of prasugrel in certain patient cohorts. In particular, prasugrel had a neutral effect in elderly patients (aged ≥75 years) and those with low body weight (<60 kg), and was associated with a net harm in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack [43]. In a clinical trial of medically managed patients with ACS, prasugrel was not shown to be superior to clopidogrel [44]. In the light of these observations, prasugrel is only indicated in patients with ACS undergoing PCI. Moreover, prasugrel is contraindicated in patients at high risk of bleeding, with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, or hypersensitivity to the drug. In patients ≥75 years or in patients with a low body weight (<60 kg) the maintenance dose of prasugrel should be reduced (i.e., 5 mg) [1, 2, 4].

In the Study of Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, 18,624 patients with ACS (unstable angina, NSTEMI, and STEMI) were randomly assigned to receive either ticagrelor (180 mg loading dose followed by 90 mg twice daily maintenance dose) or clopidogrel (300–600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily maintenance dose), in addition to aspirin for 12 months [42]. The trial enrolled patients irrespective of management (both invasive and noninvasive). Ticagrelor significantly reduced the primary composite endpoint of death from vascular causes, MI, and stroke at 12 months compared with clopidogrel (9.8% versus 11.7%; HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77–0.92), driven by a reduction in cardiovascular death and non-fatal MI. Moreover, there was a significant 25% reduction of definite/probable stent thrombosis [42]. Although the overall incidence of PLATO major bleeding was similar in the two groups, ticagrelor treatment was associated with a significant 25% increase in non-CABG related TIMI major bleeding and an increase of fatal intracranial bleeding [42]. The efficacy of ticagrelor treatment was consistent across pre-specified subgroups of patients who were initially managed invasively or noninvasively [42]. Differently from the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial, there were no subgroups, including patients aged >75 years, those with a body weight <60 kg and those with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack in whom the bleeding risk offset the efficacy of ticagrelor [42]. However, a common non-bleeding adverse effect of ticagrelor was dyspnea which occurred in 15-22% of patients, which was the most common cause of drug withdrawal [42]. The benefits of long-term use of ticagrelor at a 60 mg BID maintenance dose regimen has been confirmed in other studies of high-risk patients such as those with prior MI and diabetes mellitus (DM) [45, 46]. However, ticagrelor was not shown to be superior to clopidogrel and caused more bleeding in patients with stable CAD undergoing elective PCI [47]. Accordingly, ticagrelor is currently approved for the treatment and prevention of secondary atherothrombotic events across the spectrum of patients with ACS, irrespective of the intended treatment strategy (invasive or noninvasive) as well as in patients with prior MI and high-risk patients with CAD, including those with DM [1, 2, 4]. Ticagrelor is contraindicated in patients at high risk for bleeding, a history of hemorrhagic stroke or intracranial bleeding, severe hepatic dysfunction, and hypersensitivity to the drug.

In light of the concerns surrounding the risk of bleeding in the elderly population, the Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE) trial compared the potent P2Y12 inhibitors (ticagrelor in 95% of patients and prasugrel in 5%) versus clopidogrel among patients (n=1002) aged >70 [48]. At a follow-up of 12 months, the primary outcome of PLATO major or minor bleeding, occurred significantly less often in the clopidogrel group (18% vs 24%, HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.94) and the co-primary net clinical benefit outcome (composite of all-cause death, MI, stroke, PLATO major and minor bleeding) did not differ between groups. Of note, clopidogrel was associated with a significant 67% lower incidence of non-CABG related TIMI major bleeding and a reduction in fatal and intracranial bleeding as compared to ticagrelor [48].

3. Role of genetic testing

Overview

RCTs have shown potent P2Y12 inhibition to be associated with a significant reduction of ischemic events, particularly among high ischemic risk patients (i.e., ACS, DM or patients with recurrent cardiovascular events) [1, 2, 4]. Nevertheless, this benefit occurs at the expense of an increased risk of bleeding, including major and fatal bleeding [1, 2, 4]. While in some patients the benefits outweigh the risks, in others the net clinical benefit decreases in specific cohorts of patients (e.g., elderly) [48]. Moreover, less favorable outcomes compared to those found in RCTs have been observed in some real-world registries [49, 50].The ever growing understanding of the relevant prognostic implications of bleeding complications among patients undergoing PCI [9, 10] has prompted investigations assessing bleeding reduction strategies (e.g., use of clopidogrel, reduced DAPT duration with either early discontinuation of aspirin or P2Y12 inhibitor) [51, 52, 53]. This has also been feasible thanks to the development of safer, newer-generation drug eluting stent (DES) designs characterized by very low rates of thrombotic complications which allow for less intense antiplatelet inhibition to prevent stent-related complications [54]. Nevertheless, a non-negligible cohort of patients with both ACS or CCS will experience recurrent ischemic events after PCI, which can be related to both culprit and nonculprit lesions [55], underscoring the need for adequate platelet inhibition, especially among patients with high risk procedural and clinical features [56]. In this specific cohort of patients, potent P2Y12 inhibitors may help reduce ischemic events, but should always be weighed against an acceptable increased risk of bleeding.

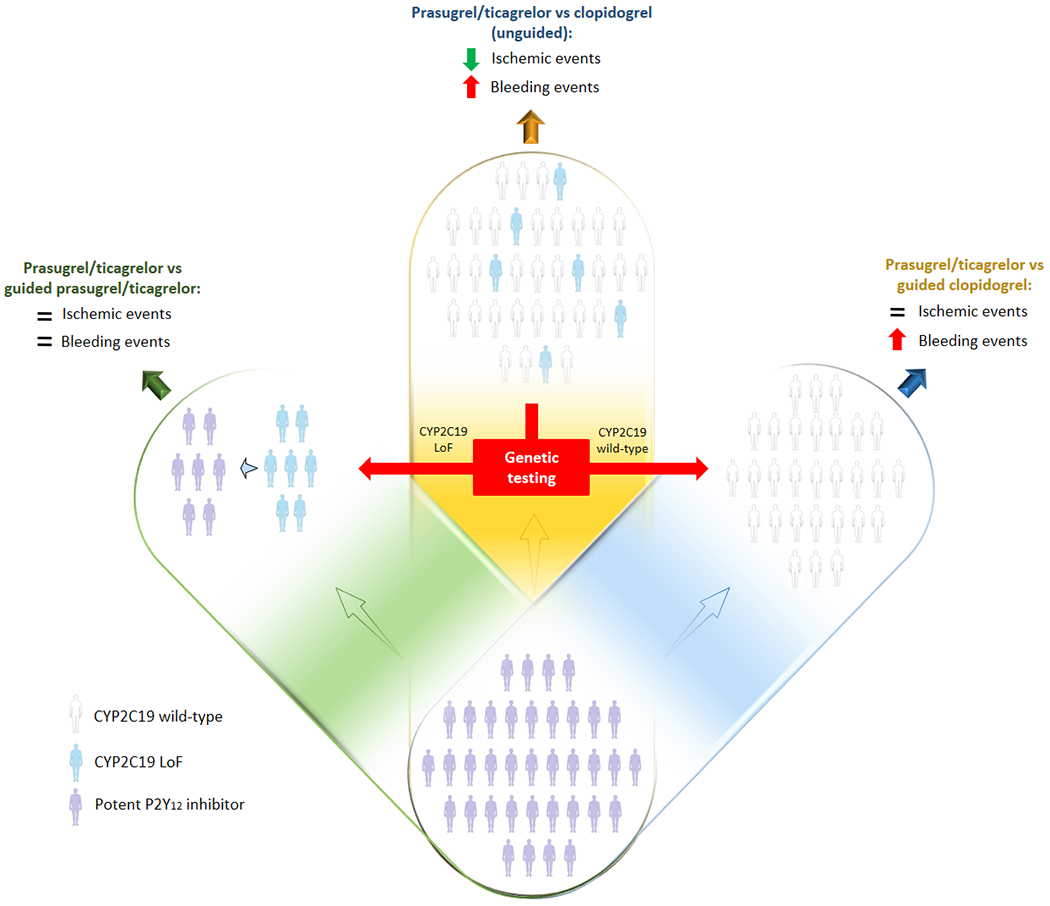

The notion that variations in an individual’s response to a P2Y12 inhibitor, in particular clopidogrel, can affect clinical outcomes in the setting of PCI [40, 41] and the availability of alternative agents, in particular prasugrel and ticagrelor, not subject to such variability in response, have prompted investigations aimed at testing the safety and efficacy associated with a guided selection of antiplatelet agent [7]. To this extent, the use of platelet function and genetic testing has been implemented to tailor such treatment to the individual patient [7, 8, 19]. Each test presents advantages and disadvantages, as summarized in Table 1. The use of a tailored approach would allow patients for whom clopidogrel-HPR is predicted based on genotype, to undergo a potent P2Y12 inhibitor to reduce the risk of thrombotic complications, while those responding to clopidogrel could avoid the use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors resulting in less bleeding but still maintaining adequate ischemic protection (Figure 2) [7].

Table 1:

Comparison of Platelet Function versus Genetic Testing

| PLATELET FUNCTION TESTING | GENETIC TESTING |

|---|---|

| Assay dependent variability | Absence of interassay variability |

| Variability of results over time that would require constant monitoring and possible ongoing changes of antiplatelet therapy | No variability of results over time |

| Results influenced by several non-patient factors | Results not influenced by non-patient factors |

| Need to be performed while on clopidogrel treatment to define responsiveness | No need to be performed while on treatment |

| Direct measure of response to therapy | Indirect measure of response to therapy |

| Assessment of impact of genetic and non-genetic factors | Assessment limited to genetic factors |

Figure 2: Clinical outcomes with unguided P2Y12 inhibitor selection (i.e. clopidogrel versus prasugrel or ticagrelor) and with guided clopidogrel versus unguided prasugrel or ticagrelor.

Randomized controlled trials comparing potent P2Y12 inhibitors versus clopidogrel showed reduced ischemic events but increased bleeding (blue). Genetic testing allows to stratify patients into two groups: CYP2C19 LoF allele carriers (left) and noncarriers (right). Among CYP2C19 LoF allele carriers, selective use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors would result in similar outcomes as compared to a default potent P2Y12 inhibitor strategy (green) while guided use of clopidogrel among CYP2C19 LoF allele noncarriers would result in reduced bleeding and similar ischemic events (yellow).

Abbreviations: LoF: loss of function; CYP: cytochrome P450.

Platelet-function testing (PFT) for the ex vivo assessment of on-treatment platelet reactivity to P2Y12 inhibitors can be classified as point-of-care or near-patient-based assays (e.g. VerifyNow, Multiplate, thromboelastography) or laboratory-based methods (e.g., light transmission aggregometry, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein, flow cytometry), with the former preferred over the latter for practical reasons [7]. Expert consensus provides standardized definitions and cutoff values to define HPR status [7]. Low platelet reactivity has also been defined and associated with an increased risk of bleeding, although data has not been as consistent as with HPR [40]. PFT as a tool to guide therapy has the advantage that it defines the platelet phenotype directly linked with thrombosis (Table 1) [7, 8]. However, it has inherent limitations including the need for a patient to be on clopidogrel to define responsiveness (time frame during which patients are at risk) and the variability in results [57]. Moreover, a considerable number of patients with HPR after de-escalation (i.e., switching from prasugrel or ticagrelor to clopidogrel) need to escalate (i.e., switch from clopidogrel to prasugrel or ticagrelor) therapy, challenging the feasibility of a close PFT monitoring, especially in non-specialized centers [57].

Genetic testing for CYP2C19 LoF alleles can overcome the above mentioned limitations given that the genetic makeup of an individual remains unvaried and does not require a patient to be on treatment (Table 1) [19]. Moreover, rapid bedside assays are now commercially available [58, 59, 60]. Specifically, two rapid assays for CYP2C19 genetic testing have been introduced: SpartanRx™ (Spartan Bioscience, Ottawa, Canada) and the Verigene® System (Nanosphere, Northbrook, Illinois) [61, 62]. The SpartanRx uses a buccal swab as a specimen and is based on polymerase chain reaction and takes only one hour to obtain genetic information [12, 63]. The Verigene CYP2C19 test, an automated microarray-based assay, uses whole blood and takes 3 hours to provide results [62]. However, CYP2C19 genotypes are not the sole contributors to clopidogrel response and thus may not always identify HPR status. Integrating clinical variables (e.g., age, body mass index, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus) with genotypes to predict HPR status has been proposed to have greater accuracy than the individual components alone [64].

Genetics of CYP2C19

CYP2C19 is an enzyme protein, member of the CYP2C subfamily of the cytochrome P450 mixed-function oxidase system. This subfamily includes enzymes that account for approximately 20% of CYPs in the adult liver [65]. In particular, it is estimated that CYP2C19 is involved in processing or metabolizing at least 10% of commonly prescribed drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines, proton pump inhibitors, anticonvulsants, hypnotics, sedatives, antidepressants, antimalarial drugs, and antiretroviral drugs) [66]. Variations in enzyme function can have a wide range of effects on drug metabolism. Polymorphisms of the CYP2C19 enzyme are the most important genetic determinants of interindividual variability in clopidogrel response [19, 24, 67, 68]. The gene that codes the CYP2C19 enzyme, located on chromosome 10 (10q24.1- q24.3), is highly polymorphic and over 35 gene alleles have been identified [69, 70]. The normal function allele (also called “wild type”) is labelled as CYP2C19*1 and represents a normal activity allele [69, 71]. The most common variant alleles include CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3 and CYP2C19*17 which contribute to interindividual differences in the pharmacokinetics and consequently the pharmacodynamic response to CYP2C19 substrates, including clopidogrel. In particular, CYP2C19*2 and *3 (loss-of-function alleles) are associated with diminished enzyme activity, whereas CYP2C19*17 (gain-of-function allele; also called an increased function allele) results in increased activity [69, 71]. There is consensus on the inclusion of these three variant alleles on standard clinical pharmacogenomic testing panels, since others alleles (i.e., CYP2C19*4A, *4B,*5, *6, *7, *8, *9, *10, and *35) are rare, are less well characterized, or lack laboratory reference material [7, 72].

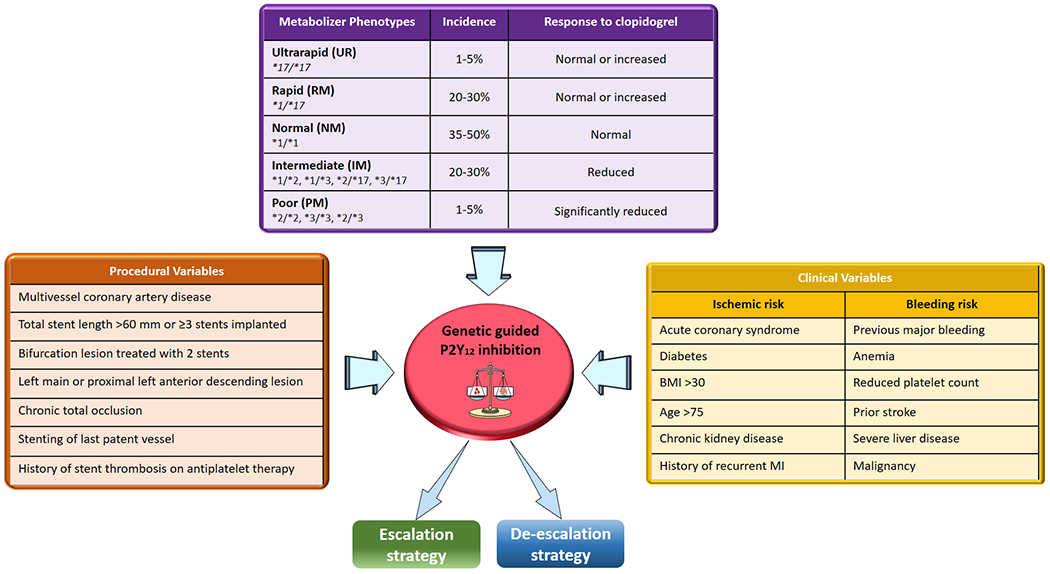

The distribution of CYP2C19 alleles allows for defining 5 different phenotypes: ultrarapid (UM), rapid (RM), normal (NM), intermediate (IM), and poor (PM) metabolizers [7, 19]. PM are carriers of 2 LoF CYP2C19 alleles (e.g. *2/*2 or *2/*3 genotype), while IM are carriers one LoF allele (e.g. *1/*2 genotype). The *1/*1, *1/*17, and *17/*17 genotypes confer the NM, RM, and UM phenotypes, respectively. There are important differences in the frequency of CYP2C19 alleles by anestry. The *2 and *3 alleles occur more commonly in East Asian than European and African ancestry populations, while *17 allele is more common in African and European than Asian ancestry populations [73]. Accordingly, the prevalence of the PM and IM phenotypes are 2-4% and 25-30% among African and Europeans ancestry populations, whereas are 10-20% and 30-40% among East Asians, respectively [73].

Several studies have shown the IM and particularly PM phenotypes to be associated with reduced levels of the active metabolite of clopidogrel, diminished platelet inhibition, and a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events following PCI, including stent thrombosis, as compared to other phenotypes [24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Nevertheless, association between CYP2C19*17 and increased risk of bleeding is less certain [74]. Importantly, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response profiles as well as clinical outcomes are not affected by CYP polymorphisms among patients treated with ticagrelor or prasugrel [75, 76].

4. Rationale for genotype guided selection of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy: escalation and de-escalation strategies

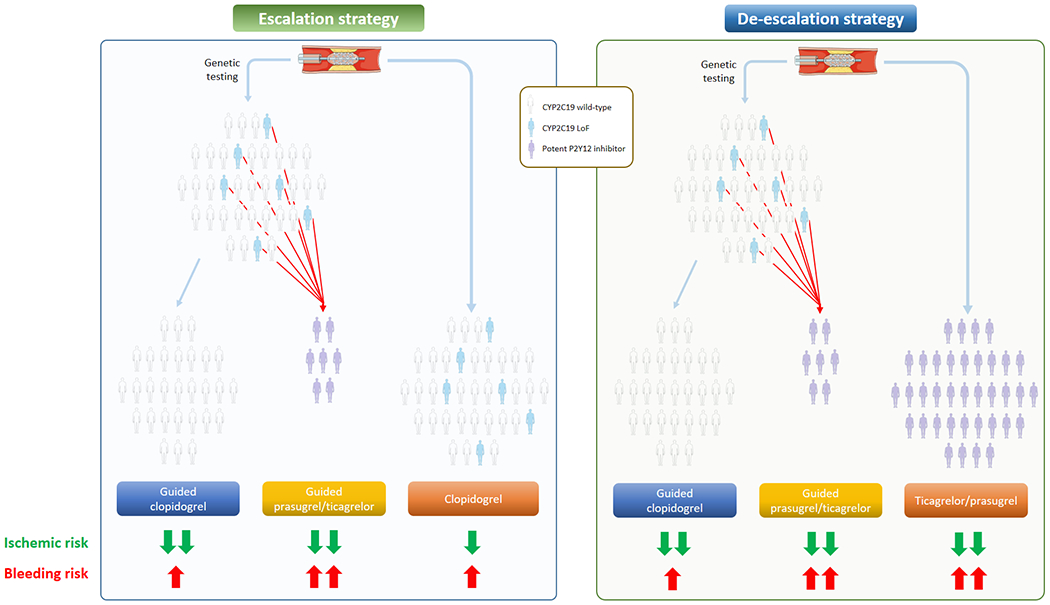

The use of genetic testing in patients undergoing PCI to guide the selection of P2Y12 inhibitor can inform the clinician to either escalation or de-escalation of therapy. A distinction between these two strategies is key to understand the rationale for their use and for a better appreciation of clinical trials on the topic of genetic guided selection of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy [77]. In fact while an escalation strategy is aimed at reducing ischemic events without trade-off in bleeding, de-escalation is aimed at reducing bleeding without trade-off in ischemic events [7].

A guided escalation strategy applies to patients in whom clopidogrel-based DAPT is initially selected (i.e., CCS but also ACS patients undergoing PCI). In this context, the scope of genetic testing is to rule out patients with CYP2C19 LoF alleles who have an increased likelihood of having impaired clopidogrel-induced platelet inhibition and thus are at risk of thrombotic complications. Thus, as compared to a default clopidogrel-based DAPT therapy, this strategy involves the selective use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors among patients with PM or IM phenotypes; patients with NM, RM and UM phenotypes would maintain clopidogrel therapy (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Escalation or de-escalation strategies following genetic testing.

According to the P2Y12 inhibitor used in the conventional therapy arm, the guided selection of P2Y12 inhibitor can result in a strategy of escalation (left) or de-escalation (right) of therapy.

Abbreviations: LoF: loss of function; CYP: cytochrome P450.

A guided de-escalation strategy applies to patients with ACS undergoing PCI initially treated with potent P2Y12 inhibitors. The strategy stems from the notion that the greatest ischemic benefit with potent platelet inhibition occurs early after PCI and reduces over time, while the risk of bleeding continues to accrue with the duration of treatment [7, 78, 79, 80]. Thus, a guided de-escalation strategy aims at identifying patients with NM, RM and UM phenotypes and selectively treating them with clopidogrel that reduces the risk of bleeding while maintaining effective ischemic protection; patients with PM and IM phenotypes would maintain treatment with potent P2Y12 inhibitors (Figure 3).

5. Clinical outcomes of genotype based personalized medicine

After the publication of a plethora of studies showing that patients with CYP2C19 LoF are at higher incidence of ischemic events as compared to noncarriers when a clopidogrel-based DAPT is used after PCI [24, 25, 26, 27, 28], two lines of research have investigated the impact of a genetic guided selection of P2Y12 inhibition among patients undergoing PCI. The first assessed outcomes associated with genetic testing selectively among patients with CYP2C19 LoF alleles (i.e., evaluating the clinical benefit of modifying P2Y12 inhibiting therapy according to the CYP2C19 genotype) and the second among the whole spectrum of PCI patients (i.e., assessing the clinical benefit of testing versus non-testing). Table 2 and 3 summarize the studies from these two lines of research.

Table 2:

Studies on CYP2C19 Genotype Guided Selection of P2Y12 Inhibitor Treatment

| Study name | Year of publication | Clinical presentation | Number of patients in each arm | Study design | Main results | Alleles genotyped (CYP2C19) | Alternative therapy | Follow-up duration (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wallentin et al | 2010 | ACS | 1384/1388 | Substudy from a multicenter RCT | Risk of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3, *4, *5,*6,*7,*8 | Ticagrelor | 12 |

| Ogawa et al | 2016 | ACS | 383/390 | Substudy from a multicenter RCT | Risk of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3 | Prasugrel* | 6 |

| Deiman et al | 2016 | CCS | 32/41 | Single-center, observational study | Risk of death from cardiovascular cause, MI, ST consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, | Prasugrel | 18 |

| Chen et al | 2017 | CCS | 46/57 | Single-center, observational study | Risk of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor | 12 |

| Zhang et al | 2017 | ACS | 100/81 | Single-center, randomized, open label | Risk of death, stroke, recurrent MI and ST consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor | 6 |

| Lee et al | 2018 | ACS and CCS | 77/186 | Single-center, observational study | Risk of death, MI, ST, ACS or stroke consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3,*17 | Ticagrelor or prasugrel | 12 |

| IGNITE | 2018 | ACS and CCS | 226/346 | Multicenter observational study | Risk of MI, stroke, or death consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor or prasugrel | 4.8 |

| GIANT | 2020 | ACS | 46/272 | Multicenter observational study | Risk of death, MI, ST consistently reduced with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3, *4, *5, *6,*17 | Clopidogrel double dose or prasugrel | 12 |

| TAILOR-PCI | 2020 | ACS and CCS | 946/903 | Multicenter, randomized, open label | Borderline non-significant reduction of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, ST, and severe myocardial ischemia with alternative therapy versus clopidogrel | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor | 12 |

Abbreviations: ACS: acute coronary syndromes CCS: chronic coronary syndromes; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CYP: cytochrome P450; LoF: loss-of-function; MI: myocardial infarction; ST: stent thrombosis; IGNITE: Implementing Genomics in Practice; GIANT: Genotyping Infarct Patients to Adjust and Normalize Thienopyridine Treatment; TAILOR-PCI: Tailored Antiplatelet Therapy Following PCI.

prasugrel 3.75 mg daily

Table 3:

Studies Comparing Guided versus Standard Selection of antiplatelet therapy.

| Study name | Year of publication | Clinical presentation | Number of patients in each arm | Study design | Main results | Alleles genotyped (CYP2C19) | Alternative therapy | Follow-up duration (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAC-PCI | 2013 | ACS | 299/301 | Single-center, randomized, open label | Escalation strategy: risk for death, MI, stroke, and TVR significantly lower with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *3 | Cilostazol on top of DAPT | 6 |

| Sánchez-Ramos et al | 2016 | ACS and CCS | 402/317 | Single-center, observational study | Escalation strategy: risk for CV death, ACS, and stroke significantly lower with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor or prasugrel | 12 |

| Shen et al | 2016 | ACS and CCS | 319/309 | Single-center, randomized, open label | Escalation strategy: risk for death, MI, and TVR significantly lower with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *3 | Clopidogrel double dose or ticagrelor | 1, 6, 12 |

| PHARMCLO | 2018 | ACS | 440/448 | Single-center, randomized, open label | Escalation strategy: risk for CV death, MI, stroke, and BARC 3–5 bleeding significantly lower with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *17 | Ticagrelor or prasugrel | 12 |

| POPular Genetic | 2019 | ACS | 1242/1246 | Multicenter, randomized, open label | De-escalation strategy: similar risk of death from any cause, MI, definite ST, stroke or PLATO major bleeding betwen groups but reduced risk of PLATO minor and major bleeding with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *3 | Clopidogrel | 12 |

| ADAPT | 2020 | ACS and CCS | 255/249 | Single-center, randomized, open label | The use of prasugrel or ticagrelor was significantly higher in the guided versus conventional group | *2, *3,*17 | Ticagrelor or prasugrel | 16 |

| TAILOR-PCI | 2020 | ACS and CCS | 2635/2641 | Multicenter, randomized, open label | Escalation strategy: non- significant reduction of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, ST, and severe myocardial ischemia with guided versus conventional therapy | *2, *3 | Ticagrelor | 12 |

Abbreviations: ACS: acute coronary syndromes CCS: chronic coronary syndromes; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; CYP: cytochrome P450; LoF: loss-of-function; MI: myocardial infarction; ST: stent thrombosis; IAC-PCI: Individual applications of clopidogrel after PCI; PHARMCLO: Pharmacogenetics of Clopidogrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes; ADAPT: Anti-Platelet Therapy in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; TAILOR-PCI: Tailored Antiplatelet Therapy Following PCI.

Outcome studies among CYP2C19 LoF patients

The genetic sub-study of the PLATO trial [75] included 10,285 patients randomized to either ticagrelor or clopidogrel. Genotyping for CYP2C19 LoF included alleles *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8 and *17. The primary composite outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke up to 12 months was consistently reduced with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.60-0.99) in patients with CYP2C19 LoF alleles. Of note, there was no difference in ischemic events among wild-type CYP2C19 carriers undergoing ticagrelor versus clopidogrel-based DAPT [75]. The studies by Deiman et al [81], Chen et al [82] and Lee et al [83] were three small single-center, observational studies that found a benefit on ischemic outcomes with the use of alternative agents (i.e. ticagrelor or prasugrel) as compared to clopidogrel therapy among patients with CYP2C19 LoF (Table 2). In a sub-study of the PRASugrel compared with clopidogrel For Japanese patIenTs with ACS undergoing PCI (PRASFIT-ACS) trial conducted in Japan [84] that randomized ACS patients undergoing PCI to receive prasugrel (loading/maintenance dose: 20/3.75mg) or clopidogrel (300/75mg) plus aspirin for 24-48 weeks, among 773 CYP2C19 LoF patients, the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (defined as the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, and ischemic stroke) was significantly lower in the prasugrel as compared to the clopidogrel group (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.45-1.35). Of note, no difference in ischemic events was found among wild-type CYP2C19 carriers treated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel-based DAPT [84]. Similarly, the randomized, open-label, single center study from Zhang et al [85] found a reduction of the composite primary endpoint at 6 months with ticagrelor as compared to clopidogrel among 181 CYP2C19 LoF ACS patients undergoing PCI [85].

The Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) study was a multicenter observational study of patients genotyped for CYP2C19 to guide antiplatelet therapy after PCI as part of clinical care. The study included 572 CYP2C19 LoF carriers treated with clopidogrel or alternative therapy including prasugrel (n=222) or ticagrelor (n=116) and 1243 CYP2C19 LoF noncarriers primarily treated with clopidogrel [86]. At a median follow-up of 4.8 months, the risk for MACE (defined as composite of MI, stroke, or death) was significantly higher in patients with a LoF allele treated with clopidogrel versus alternative therapy (HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.18-4.32) [86]. Moreover, there was no difference in outcomes between clopidogrel treated patients without a LoF allele and those with a LoF allele treated with alternative therapy. Similarly, the recent Genotyping Infarct Patients to Adjust and Normalize Thienopyridine Treatment (GIANT) study [87] was a prospective, multicenter, observational study performed at 57 sites in France enrolling 1,445 patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI. The study met its primary objective of demonstrating that the rate of ischemic events observed in CYP2C19 LoF allele carriers detected by routine genotyping and receiving adjusted higher intensity thienopyridine treatment (by using either clopidogrel 150 mg or prasugrel) was similar to that observed in patients with the CYP2C19 wild-type genotype receiving standard thienopyridine treatment. Moreover, LoF carriers who did not have had thienopyridine treatment adjusted had significantly higher rates of death, MI, and stent thrombosis at 12 month compared to those who had thienopyridine treatment adjusted [87].

Tailored Antiplatelet Therapy Following PCI (TAILOR-PCI) [14] is the largest randomized study to date to examine a clinical decision strategy that relies on CYP2C19 genotyping to guide antiplatelet drug assignment. The trial included 5,302 patients who underwent PCI, 2,650 of whom were randomized to a conventional therapy arm and received clopidogrel without initial genetic testing and 2,652 of whom were randomized to a genotype-guided therapy arm that received clopidogrel vs ticagrelor (or prasugrel) according to the absence or presence of a CYP2C19 LoF allele, respectively. The majority (85%) of CYP2C19 LoF patients were treated with ticagrelor. Patients in the conventional therapy group had genotyping performed at 12 months. Overall, the study found 1849 patients (35%) to carry a LoF allele, and these patients formed the final study cohort for the primary endpoint analysis: 903 in the genotype-guided therapy group and 946 in the conventional therapy group. Among LoF allele carriers, there was a 34% lower occurrence of the primary endpoint of MACE (composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, ST, and severe myocardial ischemia at 12 months) in the genotype-guided versus conventional therapy group but this reduction was not statistically significant (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43-1.02). However, a prespecified analysis that allowed inclusion of multiple endpoints per patient was statistically significant in favor of the genotype-based approach (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.41-0.89) [14].

Outcome studies associated with genetic testing used as a strategy

The comparison of a genotype guided versus standard selection of P2Y12 inhibitors among patients undergoing PCI is of particular clinical interest, as this helps to highlight the clinical benefits of this strategy over the standard selection of therapy. According to the clinical setting and, consequently, on the P2Y12 inhibitor used in the conventional therapy arm, genetic guidance may result in a strategy of escalation or de-escalation of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy.

Individual applications of clopidogrel after PCI (IAC-PCI) [88] and the study by Shen et al [89] were two Chinese single-center, randomized, open label trials randomizing about 600 (all ACS in the former and mixed ACS ad CCS in the latter) patients undergoing PCI to receive either a tailored treatment according to CYP2C19 genotype (i.e., adding cilostazol on top of DAPT in the former and using clopidogrel 150 mg or ticagrelor as P2Y12 inhibitor in the latter, among LoF allele carriers) or conventional antiplatelet therapy. Thus, both studies tested a guided escalation strategy. In the IAC-PCI [88] study the composite rate of death, MI, or stroke was significantly reduced in the guided as compared to the conventional group (p=0.01). Moreover, stent thrombosis (p=0.032), MI (p=0.01) and death (p=0.01) were significantly less common in the guided than in the conventional group [88]. The study by Shen et al [89] reported outcomes at 1, 6 and 12 months, showing a significant reduction in MACE (death, MI and target vessel revascularization) and the individual endpoint of MI at all the three different follow-up visits.

The single-center observational Spanish study by Sánchez-Ramos et al [90] compared a genotype-guided escalation strategy (by using ticagrelor or prasugrel in CYP2C19 LoF patients of the guided arm) [90] to standard therapy among 719 patients undergoing PCI, of whom more than 86% had ACS. At 12 months, the primary efficacy endpoint of cardiovascular death, ACS or stroke was significantly reduced with genotype-guided versus conventional therapy (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41-0.97).

The Pharmacogenetics of Clopidogrel in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes (PHARMCLO) was an Italian single-centre, randomized, open label trial [91] evaluating whether the genotype guided selection of P2Y12 inhibitors (i.e. selectively administrating ticagrelor or prasugrel among CYP2C19 LoF patients of the guided arm) leads to better outcomes as compared to standard of care among 888 ACS patients. At 12 months, the primary outcome of net clinical benefit (composite of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or BARC 3-5 bleeding) was significantly lower (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43-0.78) with guided versus conventional therapy. Moreover, a composite ischemic endpoint (including cardiovascular death, MI or stroke) was lower in the guided therapy group (HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.41-0.8). Notably, the study was stopped prematurely after enrollment of only 25% of the planned number and thus its results need to be interpreted with caution [91].

Cost-effectiveness of Genotype Guided Treatment With Antiplatelet Drugs in STEMI Patients: Optimization of Treatment (POPular Genetics) is the most relevant RCT comparing a genotype-guided to a standard of care selection of oral P2Y12 inhibitors among STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI (n=2,488)[92]. In the genotype-guided group, CYP2C19 LoF carriers received either ticagrelor or prasugrel while noncarriers received clopidogrel. Patients in the conventional group received ticagrelor or prasugrel in 93% of cases. Thus, this study tested a guided de-escalation strategy. The two primary outcomes were net adverse clinical events (composite of death from any cause, MI, definite ST, stroke, or major bleeding defined according to PLATO criteria) and PLATO major or minor bleeding. At 12 months, the genotype-guided strategy met the prespecified criterion for noninferiority but not for superiority with respect to net adverse clinical events (p<0.001 for noninferiority; HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.21, p=0.40 for superiority). The primary bleeding outcome was significantly less common in the genotype-guided group than in the standard-treatment group (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.98) [92].

Anti-Platelet Therapy in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ADAPT) [93] is a single-center, randomized, open label study randomizing 509 ACS or CCS patients undergoing PCI to a genotype guided antiplatelet therapy versus standard of care. The purpose of the study was to determine whether returning CYP2C19 genotype results along with genotype-guided pharmacotherapy recommendations using a rapid turnaround test would change antiplatelet prescribing following PCI. The primary outcome was the rate of prasugrel or ticagrelor use in each arm. The use of prasugrel or ticagrelor was significantly higher in the genotyped compared with the standard of care group (HR 1.60; 95% CI 1.07-2.42). Although this study was not designed for clinical outcomes, a non-significant trend towards reduced MACE was observed in the genotyped group [93].

The TAILOR-PCI trial initially randomized patients to a genotype guided or a conventional selection of antiplatelet therapy [14]. Although the primary endpoint of the study was to determine the effect of a genotype-guided vs. standard selection of oral P2Y12 inhibitor on ischemic outcomes selectively among CYP2C19 LoF carriers (903 from the genotype-guided group and 946 from the conventional therapy group), the trial first randomized patients to undergo a genotype-guided vs. conventional therapy among 2,652 and 2,650 patients respectively (i.e., using genetic testing used as a strategy) [14]. Overall, an escalation strategy was tested, and a non-significant trend toward a reduction of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, ST, and severe myocardial ischemia was found with guided as compared to conventional therapy (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.65, 1.07) [14]. This finding, however, is only hypothesis generating since the trial was not designed, and consequently powered, to address this outcome.

The Genotyping GUided Antiplatelet theRapy in pAtieNts Treated With Drug Eluting stEnts (GUARANTEE) trial (NCT03783351) is an ongoing RCT being conducted in China estimated to enroll 3,780 ACS or CCS patients undergoing PCI randomized to either CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy versus conventional therapy. The genotype results will be obtained within 48 hours in the genotyping arm, and carriers of LoF alleles (CYP2C19*2 or *3) will receive ticagrelor 90 mg bid, whereas non-carriers will receive clopidogrel 75 mg once daily. The primary composite endpoint will be major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event (MACCE), including all-cause death, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal MI and ischemia driven revascularization at one-year. The study is estimated to be completed in 2023 and will provide further evidence in the setting of genotype-guided versus standard selection of P2Y12 inhibitors.

6. Current guidelines and recommendations

The routine use of PFT or genetic testing to adjust antiplatelet therapy among patients with ACS or CCS is discouraged by both ACC/AHA and ESC Guidelines (Class III) [3]. This recommendation is mostly related to neutral results of early studies using PFT to guide antiplatelet therapy [13, 15, 17]. Nevertheless, results of recent trials have led to changes in recommendations, which while still not recommended for routine use, do allow the selective use of PFT and genetic testing to guide therapy. Moreover, distinction between escalation or de-escalation as two different strategies has also made its way into these recommendations [7]. In fact prior guidelines only alluded to the use of tests for an escalation approach in selected clinical scenarios [3]. However, after the results of the Testing Responsiveness to Platelet Inhibition on Chronic Antiplatelet Treatment For Acute Coronary Syndromes Trial (TROPICAL-ACS) trial [16], the 2018 ESC guidelines for myocardial revascularization [1] stated a de-escalation of P2Y12 inhibitors guided by PFT may be considered among ACS unsuitable for 12-month DAPT (Class IIb, Level of evidence B). These recommendations were extended to the recent 2020 ECS Guidelines on non-ST-segment elevation ACS to the use of genetic testing after the publication of the POPular-Genetics trial [2]. However, these Guidelines [2] were published before the publication of several relevant studies, including TAILOR PCI, ADAPT, and GIANT [14, 87, 93], and before comprehensive meta-analyses helping to overcome low statistical power of individual studies became available [94].

The most recent focused consensus document on the topic [7], published in 2019, recommend the use of genetic testing among selected clinical scenarios, underlining the need for an integrated approach that takes into consideration numerous other clinical, angiographic, procedural, and socioeconomic variables. Lastly, the more recent 2013 Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines do not provide recommendations on whether pharmacogenetic testing should be conducted, but recommend using alternative antiplatelet agents (e.g., ticagrelor or prasugrel) for CYP2C19 PMs and IMs in the absence of contraindications in ACS/PCI patients [95].

7. Conclusion

The different safety and efficacy profiles associated with the available oral P2Y12 inhibitors underscore the importance for tailoring the selection of agent to the individual patient undergoing PCI. Rapid bedside genetic testing has resulted as a useful tool to assist with the selection of P2Y12 inhibitor. In fact, studies have consistently shown CYP2C19 LoF carriers to have impaired platelet inhibition and increased risk of ischemic events compared to noncarriers when a clopidogrel-based DAPT is used. Such modulating effect of CYP2C19 genotypes is not observed with potent P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor). However, although these potent platelet inhibitors can reduce the risk of ischemic events, this comes at the expense of increased bleeding. Advances in our understanding of genetic testing, now broadly available for clinical use with rapid turnaround times, has allowed for the conduct of studies of guided selection of oral P2Y12 inhibitor. In particular, using a potent P2Y12 inhibitor in CYP2C19 LoF carriers has the potential for reducing ischemic events the benefit of which can offset the risk of bleeding, while the use of clopidogrel among noncarriers has the potential to mitigate the risk of bleeding complications without any trade-off in efficacy (Figure 2). Despite the strong rationale for a guided selection of antiplatelet therapy, many studies had pitfalls in study designs, were not powered for efficacy endpoints composed of hard ischemic events and have not provided unequivocal results. Recent studies and meta-analyses overcame in part these limitations. Moreover, since genotypes for CYP2C19 represents only one of the determinants of platelet reactivity among patients undergoing P2Y12 inhibitors, integrating procedural and clinical features to the results of genetic testing, represents the most promising approach towards the use of precision medicine to optimize the selection of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing PCI (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Integrated approach towards personalized selection of antiplatelet therapy.

Integrating the results of genetic testing with clinical and procedural variables represents a promising strategy for a precision medicine approach for the selection of antiplatelet therapy among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions.

Abbreviations: ultrarapid (UM), rapid (RM), normal (NM), intermediate (IM), and poor (PM) metabolizers.

8. Expert opinion

Oral platelet P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor) are key for the prevention of thrombotic complications in patients undergoing PCI [1, 2, 3]. Clopidogrel, the most commonly used P2Y12 inhibitor, is characterized by broad variability in individual response profiles with a considerable number of patients with impaired platelet inhibition resulting in an increased risk of thrombotic complications [40]. Clinical, cellular, and genetic factors contribute to variability in clopidogrel-induced antiplatelet effects [20]. Among the genetic factors, studies have consistently shown that functional polymorphisms of the CYP2C19 enzyme, key towards the metabolism of clopidogrel into its active metabolite, have an important role. In particular, carriers of a LoF allele treated with clopidogrel have impaired platelet inhibition and increased risk of thrombotic complications after PCI [24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 86, 87]. Importantly, the prevalence of LoF allele carrier status is overall high, varying between 20 and 40%, depending on the ancestry of the population [73]. These findings have suggested the use of genetic testing as a tool to guide the selection of P2Y12 inhibitor and thus improve outcomes [58, 96]. In particular, the selective use of a potent P2Y12 inhibitor among CYP2C19 LoF carriers has the potential for reducing bleeding risk related to their broad use and enhanced advantage over clopidogrel in reducing ischemic events the benefit of which can offset the risk of bleeding [14, 75, 81, 82, 84, 85, 86, 87, 97]. On the other hand, the selective use of clopidogrel among noncarriers of LoF alleles has the potential to mitigate the risk of bleeding complications without any trade-off in efficacy and avoiding the increase of ischemic events related to its unselective use [25, 75, 84, 97] (Figure 2).

Despite the strong rationale for the use of genetic testing to guide P2Y12 inhibitor selection in patients undergoing PCI, recent guidelines and consensus recommend the use of genetic testing only in selected scenarios [2, 7]. These recommendations stem from fact that early RCTs from a parallel line of research focused on PFT to guide antiplatelet therapy failed to demonstrate any benefit [13, 15, 17]. These results were mostly related to major pitfalls including the low risk profile of the patient population, inadequate identification of patients with impaired clopidogrel-induced platelet inhibition (i.e., suboptimal use of platelet function assays, timing of testing and HPR cut-off values) and limited use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors (i.e., prasugrel or ticagrelor) [7, 57]. An understanding of the limitations of these earlier studies led to the design of investigations better suited to define the potential benefits of a guided selection of antiplatelet therapy, including the use of genetic testing for CYP2C19 LoF alleles that can overcome several inherent limitations of PFT [7].

Two lines of research using genetic testing have been developed in patients undergoing PCI. The first tested the clinical benefit of using a more potent P2Y12 inhibition versus a clopidogrel selectively among carriers of CYP2C19 LoF alleles [14, 75, 81, 82, 84, 85, 86, 87, 89]. However, although these studies have proven useful to confirm a clinical benefit of using alternative antiplatelet agents (i.e., prasugrel or ticagrelor) instead of clopidogrel among patients carriers of CYP2C19 LoF alleles, the nature of their study design does not address an even more relevant question on the utility of using genetic testing as a strategy (i.e., assessing the clinical benefit of testing versus not testing). Thereafter, studies randomizing patients undergoing PCI to either a tailored selection of P2Y12 inhibitor based on the results of genetic testing or conventional antiplatelet therapy have been performed [12, 14, 88, 89, 90, 91, 93]. To this extent, the results of the genetic testing can lead to escalation or de-escalation of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy (Figure 3).

Nevertheless, most trials assessing an escalation approach lack of statistical power for efficacy outcomes [14, 88, 89, 90, 91, 93]. On the other hand, the use of a genotype-guided de-escalation approach as compared to conventional therapy is supported thus far by only one RCT [12]. These observations explain why genetic testing is still not recommended to be performed routinely in all patients undergoing PCI in guidelines and expert consensus statements [2, 7]. More specifically, the most recent 2020 recommendations indicate that the use of genetic testing may be considered particularly for a de-escalation approach as an alternative DAPT strategy, especially for ACS patients deemed unsuitable for potent platelet inhibition (Class IIb, Level of Evidence A)[2]. However, it is also important to note that some relevant studies were published after the development of these documents [14, 87, 93], and that a comprehensive meta-analysis helping to overcome low statistical power of individual studies have recently shown a clear benefit of guided versus standard selection of P2Y12 inhibitors among patients undergoing PCI [94]. Indeed, results from these recent studies may potentially impact future recommendations on the use of a genetic-guided selection of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy [96, 98]. Moreover, implementation of a guided strategy could also have economic (i.e., cost-saving) implications [99]. Eventually, despite genetic tests being a rapid and easy bedside tool, genotype represents only one of the determinants of platelet reactivity among patients undergoing P2Y12 inhibitors, and integrating genetic information with clinical and procedural variables is likely to represent the most successful strategy for a precision medicine approach as it relates to the selection of antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing PCI (Figure 4) [7, 64].

Highlights.

Approximately 30% of patients treated with clopidogrel persist with high platelet reactivity, a marker of thrombotic risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Although the use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors (i.e, prasugrel and ticagrelor) can overcome this limitation, this occurs at the expenses of an increased risk of bleeding.

Genetic variations of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 enzyme, a key determinant in clopidogrel metabolism, have been strongly associated with clopidogrel response profiles prompting investigations of genetic-guided selection of antiplatelet therapy.

Implementation of genetic testing as a strategy to guide the selection of therapy can result into escalation (i.e., use of prasugrel or ticagrelor) or de-escalation (i.e., use of clopidogrel) of P2Y12 inhibiting therapy with the goal of optimizing safety and efficacy outcomes.

Integrating the results of genetic testing with clinical and procedural variables represents a promising strategy for a precision medicine approach for the selection of antiplatelet therapy among patients undergoing PCI.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI R01 HL149752 (LHC, DJA) and NIH/NCATS UL1 TR001427 (LHC). M.G. is supported by a grant from Fondazione Enrico Ed Enrica Sovena (Rome, Italy).

Potential conflicts of interest:

M.G. has nothing to disclose. F.F. declares that he has received consulting fees or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer and Sanofi. F.R. declares that he has received honoraria from Chiesi. D.C. declares that he has received consulting and speaker’s fee from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Menarini outside the present work. F.C. declares that he has received consulting and speaker’s fees from Biotronic, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Servier, Menarini, BMS, outside the present work. D.J.A. declares that he has received consulting fees or honoraria from Abbott, Amgen, Aralez, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chiesi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Haemonetics, Janssen, Merck, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company and has received payments for participation in review activities from CeloNova and St Jude Medical, outside the present work. D.J.A. also declares that his institution has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biosensors, CeloNova, CSL Behring, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Matsutani Chemical Industry Co., Merck, Novartis, Osprey Medical, Renal Guard Solutions and Scott R. MacKenzie Foundation.

LIST OF ABBREVATIONS

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- CCS

chronic coronary syndrome

- UA

unstable angina

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- DAPT

dual antiplatelet therapy

- MI

myocardial infarction

- HPR

high-platelet-reactivity

- LPR

low-platelet-reactivity

- PFT

platelet-function testing

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MACCE

major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event

- DES

drug eluting stent

- BARC

bleeding academic research consortium

- TIMI

thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- NSTEMI

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- LoF

loss of function

- UM

ultrarapid metabolizers

- RM

rapid metabolizers

- NM

normal metabolizers

- IM

intermediate metabolizers

- PM

poor metabolizers

- VKA

vitamin K antagonist

- DOAC

direct oral anticoagulant

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- ST

stent thrombosis

- ENT-1

equilibrated nucleoside transporter-1

- PLATO

platelet inhibition and patient outcomes

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CPIC

clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium

- ACC

American college of cardiology

- AHA

American heart association

- ESC

European society of cardiology

- SCAI

society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions

- ACCF

American college of cardiology foundation

REFERENCES

- 1.Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. European Heart Journal. 2019;40(2):87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. European heart journal. 2020. Aug 29. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capodanno D, Alfonso F, Levine GN, et al. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: JACC Guideline Comparison. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018. Dec 11;72(23 Pt A):2915–2931. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018. Jan 7;39(2):119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossavy JP, Thalamas C, Sagnard L, et al. A double-blind randomized comparison of combined aspirin and ticlopidine therapy versus aspirin or ticlopidine alone on experimental arterial thrombogenesis in humans. Blood. 1998. Sep 1;92(5):1518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franchi F, Angiolillo DJ. Novel antiplatelet agents in acute coronary syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015. Jan;12(1):30–47. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sibbing D, Aradi D, Alexopoulos D, et al. Updated Expert Consensus Statement on Platelet Function and Genetic Testing for Guiding P2Y(12) Receptor Inhibitor Treatment in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovascular interventions. 2019. Aug 26;12(16):1521–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franchi F, Rollini F, Cho JR, et al. Platelet function testing in contemporary clinical and interventional practice. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2014. May;16(5):300. doi: 10.1007/s11936-014-0300-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buccheri S, Capodanno D, James S, et al. Bleeding after antiplatelet therapy for the treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review of the evidence and evolving paradigms. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019. Dec;18(12):1171–1189. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2019.1680637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urban P, Mehran R, Colleran R, et al. Defining high bleeding risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a consensus document from the Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk. European heart journal. 2019. Aug 14;40(31):2632–2653. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ari H, Ozkan H, Karacinar A, et al. The EFFect of hIgh-dose ClopIdogrel treatmENT in patients with clopidogrel resistance (the EFFICIENT trial). International journal of cardiology. 2012. Jun 14;157(3):374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, et al. A Genotype-Guided Strategy for Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Primary PCI. 2019;381(17):1621–1631. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collet J-P, Cuisset T, Rangé G, et al. Bedside Monitoring to Adjust Antiplatelet Therapy for Coronary Stenting. 2012;367(22):2100–2109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira NL, Farkouh ME, So D, et al. Effect of Genotype-Guided Oral P2Y12 Inhibitor Selection vs Conventional Clopidogrel Therapy on Ischemic Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The TAILOR-PCI Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2020;324(8):761–771. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price MJ, Berger PB, Teirstein PS, et al. Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial. Jama. 2011. Mar 16;305(11):1097–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibbing D, Aradi D, Jacobshagen C, et al. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017. Oct 14;390(10104):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trenk D, Stone GW, Gawaz M, et al. A randomized trial of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with high platelet reactivity on clopidogrel after elective percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of drug-eluting stents: results of the TRIGGER-PCI (Testing Platelet Reactivity In Patients Undergoing Elective Stent Placement on Clopidogrel to Guide Alternative Therapy With Prasugrel) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012. Jun 12;59(24):2159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng YY, Wu TT, Yang Y, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy guided by a novel detection of platelet aggregation function in stable coronary artery disease patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled clinical trial. European heart journal Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. 2020. Jul 1;6(4):211–221. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon JY, Franchi F, Rollini F, et al. Role of genetic testing in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Expert review of clinical pharmacology. 2018. Feb;11(2):151–164. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1353909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angiolillo DJ, Ferreiro JL, Price MJ, et al. Platelet function and genetic testing. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013. Oct 22;62(17 Suppl):S21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertrand ME, Rupprecht HJ, Urban P, et al. Double-blind study of the safety of clopidogrel with and without a loading dose in combination with aspirin compared with ticlopidine in combination with aspirin after coronary stenting : the clopidogrel aspirin stent international cooperative study (CLASSICS). Circulation. 2000. Aug 8;102(6):624–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.6.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trenk D, Hochholzer W. Genetics of platelet inhibitor treatment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(4):642–653. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12230. PubMed PMID: 23981082; eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savi P, Pereillo JM, Uzabiaga MF, et al. Identification and biological activity of the active metabolite of clopidogrel. Thromb Haemost. 2000. Nov;84(5):891–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shuldiner AR, O’Connell JR, Bliden KP, et al. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy. Jama. 2009. Aug 26;302(8):849–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, et al. Cytochrome P-450 Polymorphisms and Response to Clopidogrel. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(4):354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mega JL, Simon T, Collet JP, et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2010. Oct 27;304(16):1821–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, et al. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009. Jan 22;360(4):363–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Fromm MF, et al. Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism and of major demographic characteristics on residual platelet function after loading and maintenance treatment with clopidogrel in patients undergoing elective coronary stent placement. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010. Jun 1;55(22):2427–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehmel JL, Eckstein JA, Farid NA, et al. Interactions of two major metabolites of prasugrel, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, with the cytochromes P450. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006. Apr;34(4):600–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capodanno D, Dharmashankar K, Angiolillo DJ. Mechanism of action and clinical development of ticagrelor, a novel platelet ADP P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010. Feb;8(2):151–8. doi: 10.1586/erc.09.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.VANG JJ, Nilsson L, Berntsson P, et al. Ticagrelor binds to human P2Y(12) independently from ADP but antagonizes ADP-induced receptor signaling and platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost. 2009. Sep;7(9):1556–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine-mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014. Jun 17;63(23):2503–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Amario D, Restivo A, Leone AM, et al. Ticagrelor and preconditioning in patients with stable coronary artery disease (TAPER-S): a randomized pilot clinical trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):192–192. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galli M, Andreotti F, D’Amario D, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in the early phase of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European heart journal Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. 2020. Jan 1;6(1):43–56. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park Y, Franchi F, Rollini F, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2016. Sep;17(13):1775–87. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1202924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Effects of Clopidogrel in Addition to Aspirin in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes without ST-Segment Elevation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(7):494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT 3rd, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002. Nov 20;288(19):2411–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Addition of Clopidogrel to Aspirin and Fibrinolytic Therapy for Myocardial Infarction with ST-Segment Elevation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(12):1179–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2005;366(9497):1607–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67660-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aradi D, Kirtane A, Bonello L, et al. Bleeding and stent thrombosis on P2Y12-inhibitors: collaborative analysis on the role of platelet reactivity for risk stratification after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2015. Jul 14;36(27):1762–71. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone GW, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, et al. Platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after coronary artery implantation of drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES): a prospective multicentre registry study. Lancet (London, England). 2013. Aug 17;382(9892):614–23. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(11):1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. 2007;357(20):2001–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roe MT, Armstrong PW, Fox KAA, et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel for Acute Coronary Syndromes without Revascularization. 2012;367(14):1297–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, et al. Long-Term Use of Ticagrelor in Patients with Prior Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(19):1791–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Simon T, et al. Ticagrelor in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease and Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(14):1309–1320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silvain J, Lattuca B, Beygui F, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in elective percutaneous coronary intervention (ALPHEUS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. The Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gimbel M, Qaderdan K, Willemsen L, et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): the randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England). 2020. Apr 25;395(10233):1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.You SC, Rho Y, Bikdeli B, et al. Association of Ticagrelor vs Clopidogrel With Net Adverse Clinical Events in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Jama. 2020;324(16):1640–1650. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szummer K, Montez-Rath ME, Alfredsson J, et al. Comparison Between Ticagrelor and Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients With an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insights From the SWEDEHEART Registry. Circulation. 2020. Nov 3;142(18):1700–1708. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galli M, Capodanno D, Andreotti F, et al. Safety and efficacy of P2Y(12) inhibitor monotherapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020. Nov 30:1–13. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2021.1850691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benenati S, Galli M, De Marzo V, et al. Very Short vs. Long Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after Second Generation Drug-eluting Stents in 35,785 Patients undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: a Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. European heart journal Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. 2020. Jan 14. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]