Abstract

Aims

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and short QT syndrome (SQTS) are inherited arrhythmogenic disorders that can cause sudden death. Numerous genes have been reported to cause these conditions, but evidence supporting these gene–disease relationships varies considerably. To ensure appropriate utilization of genetic information for CPVT and SQTS patients, we applied an evidence-based reappraisal of previously reported genes.

Methods and results

Three teams independently curated all published evidence for 11 CPVT and 9 SQTS implicated genes using the ClinGen gene curation framework. The results were reviewed by a Channelopathy Expert Panel who provided the final classifications. Seven genes had definitive to moderate evidence for disease causation in CPVT, with either autosomal dominant (RYR2, CALM1, CALM2, CALM3) or autosomal recessive (CASQ2, TRDN, TECRL) inheritance. Three of the four disputed genes for CPVT (KCNJ2, PKP2, SCN5A) were deemed by the Expert Panel to be reported for phenotypes that were not representative of CPVT, while reported variants in a fourth gene (ANK2) were too common in the population to be disease-causing. For SQTS, only one gene (KCNH2) was classified as definitive, with three others (KCNQ1, KCNJ2, SLC4A3) having strong to moderate evidence. The majority of genetic evidence for SQTS genes was derived from very few variants (five in KCNJ2, two in KCNH2, one in KCNQ1/SLC4A3).

Conclusions

Seven CPVT and four SQTS genes have valid evidence for disease causation and should be included in genetic testing panels. Additional genes associated with conditions that may mimic clinical features of CPVT/SQTS have potential utility for differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, Short QT syndrome, Genetic testing, Mendelian genetics

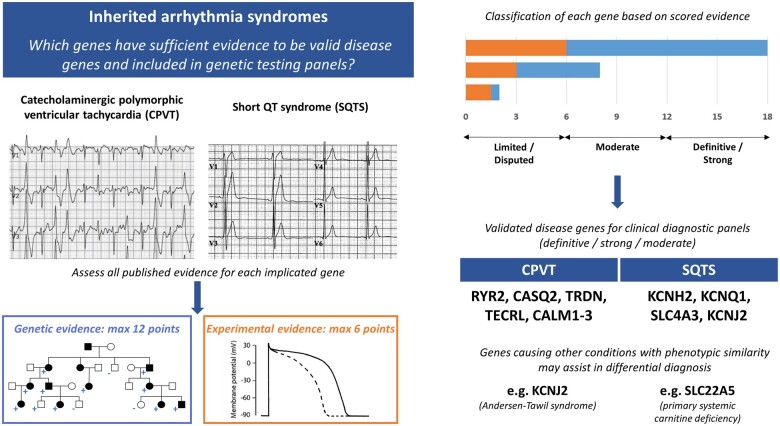

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Pandora will never regret having opened her box: reappraisal of genes associated with CPVT and SQTS’, by Minoru Horie et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab794.

Translational perspective.

This study comprehensively reappraises the evidence for genes implicated in the inherited arrhythmias catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and short QT syndrome using the ClinGen curation framework. The genes identified as having substantial evidence for disease causation should be included in clinical genetic testing panels for these diseases while genes with insufficient evidence, or those causing other arrhythmia phenotypes, should be sequenced and interpreted more cautiously. These findings will enable a more evidence-based approach to diagnostic genetic testing and help to reduce the number of uncertain or false positive findings obtained from the inclusion of wrongly implicated genes.

Introduction

In contemporary practice, genetic testing is routinely used in the evaluation of inherited cardiac syndromes, enabling the implementation of precision medicine for patients and genetic cascade screening to identify at-risk family members. This has been made possible by the identification of disease genes over the past three decades, initially through linkage analysis in large family pedigrees and more recently by unbiased whole exome sequencing and through candidate gene studies (where plausible disease genes are selected for sequencing in patient cohorts). While the latter approach has been successful in identifying some disease-causing genes in situations where large families are unavailable, its limitations in establishing valid gene–disease relationships have been exposed in recent years. We now recognize that many genetic variants previously described as pathogenic are too common in populations to be disease causing and that rare but benign variants are collectively common in many genes. These developments have prompted the re-evaluation of many gene–disease relationships and the recognition that more rigorous approaches are needed to define Mendelian disease genes.

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and short QT syndrome (SQTS) are rare inherited arrhythmogenic disorders that can lead to sudden cardiac death (SCD) at a young age. It is therefore imperative to diagnose patients early to implement primary prevention measures such as appropriate medical therapy or implantable cardioverter–defibrillator insertion. Genetic testing is now widely applied for CPVT and SQTS, but the interpretation of results is hampered by challenges in accurate phenotyping of these conditions, despite the availability of diagnostic criteria.1 , 2

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia often presents in children or young adults with syncope or SCD triggered by β-adrenergic stimulation related to exercise or emotional stress. Patients have normal electrocardiograms (ECGs) at rest with usually no evidence of structural heart disease on cardiac imaging. Diagnosis is made through the use of exercise testing (or Holter monitor in children) to detect exercise-induced arrhythmias, most commonly bi-directional and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT).2 These observations upon exercise but not at rest potentially enable clinicians to distinguish CPVT from other arrhythmogenic disorders that can induce syncope and/or cardiac arrest in patients with structurally normal hearts.

Short QT syndrome is characterized by abbreviation of the cardiomyocyte action potential duration, which manifests as a short QT interval on ECG. SQTS patients have a propensity to develop atrial fibrillation at a young age and are at risk of SCD.3 Due to the near absence of large families with SQTS, genetic research using linkage analysis is impossible and our knowledge of SQTS genetics is almost solely dependent on data derived from single patients or small kindreds.

Genes reported in CPVT and SQTS are often incorporated into clinical genetic testing panels irrespective of the strength of evidence provided for these assertions. We have previously reassessed the genetic aetiology of the arrhythmogenic disorders Brugada syndrome (BrS)4 and long QT syndrome (LQTS)5 using a standardized, evidence-based framework for examining reported gene–disease relationships.6 Here, we report the reappraisal of all previously published genes reported to cause CPVT and SQTS, to enable more accurate interpretation of genetic data and appropriate clinical management in patients and families with these potentially life-threatening conditions.

Methods

Gene curation framework

The evidence for gene–disease relationships was evaluated as previously described for BrS and LQTS.4 , 5 Briefly, three teams of biocurators independently curated each gene, applying the ClinGen Gene Curation Framework version 7 of the standard operating procedure.6 This framework uses a semi-quantitative scoring system for genetic (maximum 12 points) and experimental (maximum 6 points) evidence from published studies only, which categorizes each gene–disease relationship into a clinical validity classification level—Definitive (total of 12–18 points and replicated over time in the literature), Strong (12–18 points), Moderate (7–11 points), and Limited (1–6 points). A gene curation expert panel (GCEP), comprising 10 individuals with collectively dozens of years of experience in clinical care and/or research in the field of CPVT, SQTS, and clinical genetics, was tasked with performing final evaluation and classification on a gene-by-gene basis. The panel had the option of modifying the findings of the curation template scores (upgrade, no change, downgrade) based on the available evidence. See Supplementary material online for full details of Methods.

Results

Summary of findings

Eleven genes were evaluated as reported causes of CPVT: eight with autosomal dominant (AD) inheritance, two with autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance, and one gene, CASQ2, was analysed separately for both (Table 1). The literature search identified nine genes that have been previously reported as causing SQTS (Table 2). Detailed curation summaries and classification matrices for each gene are available in the Supplementary material online.

Table 1.

Classification of evidence for genes reported as causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

| Gene | Protein | HGNC ID | Chromosomal location | Inheritance | Presence on GTR panels, n = 12 (%) | Scoring classification | Final expert classification | Other arrhythmia conditions with valid gene–disease relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYR2 | Ryanodine receptor 2 | 10484 | 1q43 | AD | 100% | Definitive | Definitive | — |

| CASQ2 | Calsequestrin-2 | 1513 | 1p13.1 | AR | 100% | Definitive | Definitive | — |

| AD | Moderate | Moderate | ||||||

| TRDN | Triadin | 12261 | 6q22.31 | AR | 92% | Definitive | Definitive | LQTS |

| TECRL | Trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA reductase like | 27365 | 4q13.1 | AR | 25% | Definitive | Definitive | — |

| CALM1 | Calmodulin-1 | 1442 | 14q32.11 | AD | 92% | Moderate | Moderate a | LQTS |

| CALM2 | Calmodulin-2 | 1445 | 2p21 | AD | 58% | Moderate | Moderate a | LQTS |

| CALM3 | Calmodulin-3 | 1449 | 19q13.32 | AD | 67% | Limited | Moderate a | LQTS |

| KCNJ2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily J member 2 | 6263 | 17q24.3 | AD | 92% | Limited | Disputed | Andersen–Tawil syndrome, SQTS |

| SCN5A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 | 10593 | 3p22.2 | AD | 25% | Limited | Disputed | LQTS, BrS |

| PKP2 | Plakophilin-2 | 9024 | 12p11.21 | AD | 0% | Limited | Disputed | ARVC |

| ANK2 | Ankyrin-2 | 493 | 4q25-q26 | AD | 75% | Limited | Disputed | — |

Genes implicated in CPVT that were reappraised in this study.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; BrS, Brugada syndrome; CPVT, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; GTR, Genetic Testing Registry; LQTS, long QT syndrome; SQTS, short QT syndrome.

See Discussion regarding limitations of the gene curation template for the CALM gene family.

Table 2.

Classification of evidence for genes reported as causing short QT syndrome

| Gene | Protein | HGNC ID | Chromosomal location | Inheritance | Presence on GTR panels, n = 19 (%) | Scoring classifi cation | Final expert classification | Other arrhythmia conditions with valid gene–disease relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CACNA1C | Calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C | 1390 | 12p13.33 | AD | 89% | Limited | Disputed | Timothy syndrome |

| CACNA2D1 | Calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit alpha2delta 1 | 1399 | 7q21.11 | AD | 63% | Limited | Disputed | — |

| CACNB2 | Calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit beta 2 | 1402 | 10p12.3 | AD | 89% | Limited | Disputed | — |

| KCNH2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 | 6251 | 7q36.1 | AD | 100% | Definitive | Definitive | LQTS |

| KCNJ2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily J member 2 | 6263 | 17q24.3 | AD | 95% | Moderate | Moderate | Andersen–Tawil syndrome |

| KCNQ1 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 | 6294 | 11p15.5-p15.4 | AD | 100% | Strong | Strong | LQTS |

| SLC22A5 | Solute carrier family 22 member 5 | 10969 | 5q31.1 | AR | 11% | Limited | Disputed (SQTS-mimic)a | — |

| SLC4A3 | Solute carrier family 4 member 3 | 11028 | 7q36.1 | AD | 0% | Moderate | Moderate–Strong b | — |

| SCN5A | Sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 5 | 10593 | 3p22.2 | AD | 0% | Limited | Disputed | BrS, LQTS |

Genes implicated in SQTS that were reappraised in this study.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; BrS, Brugada syndrome; GCEP, gene curation expert panel; GTR, Genetic Testing Registry; LQTS, long QT syndrome; SQTS, short QT syndrome

This gene does not cause SQTS but primary systemic carnitine deficiency which may mimic SQTS.

The GCEP was divided between moderate and strong classifications (see text for details).

Definitive genes specific for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

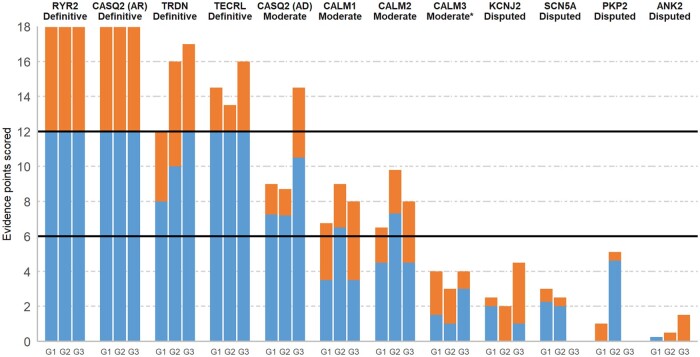

RYR2 (AD inheritance) and CASQ2 (AR inheritance) were the first genes reported to cause CPVT (in 20017 and 2002,8 respectively). Both genes were classified as Definitive after reaching the maximum amount of genetic and experimental points with curation of only a small subset of available published evidence (Figure 1). Gain-of-function missense variants in RYR2 are detected in at least 50% of CPVT cases with a definitive diagnosis,9 with the gene–disease relationship supported by multiple reports of familial segregation in large pedigrees, numerous examples of de novo inheritance in sporadic cases7 and an abundance of functional characterization of variants detected in patients. Biallelic loss-of-function variants in CASQ2 have been described in numerous CPVT cases, with the relationship further supported by a plethora of experimental evidence including knockout mice that recapitulate the disease phenotype.

Figure 1.

Disease causality classification and level of evidence scores for genes implicated in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. For each curated gene, the genetic (up to a maximum of 12 points, blue) and experimental (up to a maximum of 6 points, orange) evidence scores of the three blinded curating teams (G1, G2, G3) are detailed, along with the consensus classifications obtained. *Although CALM3 scored with Limited evidence, the gene curation expert panel unanimously decided to upgrade this to Moderate.

As some recent reports have suggested that heterozygous loss-of-function variants in CASQ2 may also be disease-causing,10 , 11 evidence for AD inheritance for CASQ2 was evaluated separately. Most of this evidence came from a recent multi-centre study on CASQ2-related CPVT that described 12 CPVT probands with heterozygous CASQ2 variants and a CPVT phenotype in 8/37 (22%) of heterozygous relatives of biallelic probands.10 After discussion, the GCEP came to the consensus that these data should be cautiously interpreted and constituted Moderate evidence for causing AD CPVT (Figure 1). The reasons included the absence of adjudicated phenotyping of cases and uncertainty about the pathogenicity of some variants, i.e. population frequencies incompatible with AD CPVT, loss-of-function variants with uncertain effects (presumed nonsense-mediated decay-escaping C-terminal truncating variants and a splice region variant of unproven effect), and missense variants with limited functional characterization. More research is required to define the penetrance of CASQ2 loss-of-function variants in the heterozygous state.

Genes with both catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and long QT syndrome phenotypes

While RYR2 and CASQ2 are associated with a distinct CPVT phenotype, a number of recently described arrhythmia genes have been shown to present with phenotypes that can include CPVT or LQTS (or features of both conditions). TRDN (encoding triadin) and TECRL (encoding trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA reductase like) were recently reported in AR CPVT and classified as Definitive genes based on multiple reports of patients with biallelic loss-of-function variants and supporting experimental data including TRDN knockout mice (Figure 1). Most of these published cases were early onset and presented in childhood with syncope or cardiac arrest. TRDN was previously classified with Strong evidence for causing an atypical and early onset form of LQTS.5 Several of the TECRL CPVT patients also displayed a longer than normal QT interval (though rarely >500 ms), but this gene was not assessed in the LQTS gene curation study.

Three calmodulin genes (CALM1, CALM2, CALM3) are located on different chromosomes but encode identical 149 amino acid proteins. All three were previously classified as having Definitive evidence for LQTS with atypical features such as presentation in infancy or early childhood and with functional heart block and severe QT prolongation.5 The recently published International Calmodulinopathy Registry described 74 cases with calmodulin variants, with a LQTS phenotype more prevalent than CPVT (49% vs. 28%).12 Based on curation of the available genetic and experimental evidence for CPVT, the genes scored as Moderate, Moderate, and Limited for CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3, respectively (Figure 1). After discussion, the GCEP decided unanimously to upgrade CALM3 to Moderate on the curation matrix. However, the GCEP believed the restrictions of the general scoring framework yielded overly conservative classifications for the calmodulin genes and that all three genes can cause CPVT (see Discussion for details).

Genes disputed as a cause for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Four genes (ANK2, KCNJ2, PKP2, and SCN5A) scored with Limited evidence as single gene causes for CPVT and were subsequently classified as Disputed by the GCEP (Figure 1). Variants in ANK2 were detected in patients with a reported CPVT-like phenotype in three families, with mutant ankyrin-B unable to rescue the arrhythmia phenotype of ankyrin-B heterozygous null mice upon transfection, in contrast to wild-type protein.13 However, each of these variants are now recognized as too common in the population to be dominant causes of CPVT, with maximum gnomAD population prevalence in the range of 1/250 individuals. Therefore, this gene–disease relationship was classified as Disputed (as it has previously been for BrS4 and LQTS5).

Variants in the other three genes (KCNJ2, PKP2, and SCN5A) were described in patients that had some phenotypic features that were clinically interpreted to represent CPVT. Although the variants reported in these genes were highly likely to be responsible for the arrhythmogenic phenotypes of these cases (based on evidence from functional assays, the enrichment of truncating variants in cases and segregation in a large family pedigree for KCNJ2, PKP2, and SCN5A, respectively), the GCEP deemed that despite the ventricular arrhythmia burden described, these cases did not have CPVT but rather represented cardiac-restricted expression of Andersen–Tawil syndrome (ATS) (KCNJ2),14–16 the concealed cardiomyopathy stage of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (PKP2),17 and a phenotype of multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions (MEPPC) (SCN5A).18 The three genes were therefore downgraded to Disputed for CPVT (see Discussion).

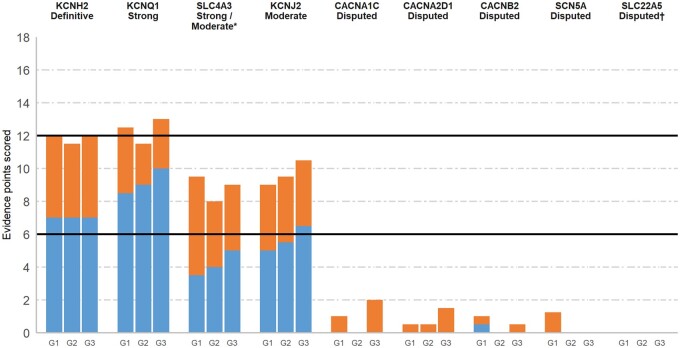

Definitive short QT syndrome-causing gene

KCNH2 was the only gene classified as Definitive for disease causality in SQTS, with variants identified in 18 SQTS probands, including seven unrelated probands of both Caucasian and Asian ethnicity with p.Thr618Ile and six with p.Asn588Lys. This genetic evidence, coupled with supporting experimental evidence, was deemed sufficient by the GCEP for classification of KCNH2 as definitively causing SQTS (Figure 2). It should be noted that the curation scores for KCNH2 were lower than those of other Definitive genes in previous gene–disease curation efforts. According to the gene curation framework utilized here, the maximum genetic evidence score cannot be reached based on identification of non-de novo missense variants alone. Additional evidence from de novo or loss-of-function variants, segregation, or case–control data would be required for a maximal score, which are not available for KCNH2 due to the disease mechanism (gain-of-function) and the paucity of cases. Accordingly, the GCEP recognized this limitation in the framework and did not view the relatively lower curation scores as dissuasion towards Definitive classification.

Figure 2.

Disease causality classification and level of evidence scores for genes implicated in short QT syndrome. Validity scores according to the ClinGen curation framework and final classifications of the gene curation expert panel. Genetic (up to a maximum of 12 points, blue) and experimental (up to a maximum of 6 points, orange) evidence scores of each of the three blinded curating teams (G1, G2, G3) are detailed. Complete list of references used for scoring of these genes is available in the supplements. *The gene curation expert panel was divided between Moderate and Strong classifications. †This gene is a short QT syndrome-mimic. See text for further details.

Genes with moderate-strong level of evidence for short QT syndrome

Variants in KCNQ1 were identified in nine SQTS probands, eight of which were the p.Val141Met variant. The presentation of all cases with p.Val141Met was similar: severe bradycardia was identified in utero or at birth, with atrial fibrillation also diagnosed in six cases and no reports of cardiac arrest or SCD.19 It was reported to be de novo in three cases (although paternity was not proven in all). The other variant, p.Val307Leu, was described in a single case with a cardiac arrest at the age of 70,20 much older than other reported SQTS cases. Three other variants (p.Phe279Ile,21 p.Arg259His,22 and p.Ala287Thr23) were reported in suspected cases of SQTS; however, due to incomplete or inconclusive phenotype data, the GCEP unanimously agreed not to score these variants. The final score for KCNQ1 and the reproducibility of supporting evidence over time was sufficient for a Definitive classification; however, the fact that almost all genetic evidence was derived from a single variant led the GCEP to limit the classification of KCNQ1 to Strong for SQTS.

Genetic evidence supporting SLC4A3 as an SQTS-causing gene is derived from one recent publication in which exome sequencing in two families, including one large pedigree, detected the same p.Arg370His rare variant.24 Experimental evidence from in vitro and zebrafish models suggests that reduced membrane localization of the mutated protein leads to intracellular alkalinization and shortening of the action potential duration. While the unbiased gene discovery approach and segregation evidence strongly supports causality of this variant, the lack of other publications supporting this gene–disease relationship led to a score in the Moderate range using the gene curation template. The GCEP discussed upgrading the final classification but was divided on this issue with four panellists voting for Strong and five for Moderate.

Genetic variants in KCNJ2 have been identified in six SQTS patients from five families, including at least two probands with a de novo variant (paternity not confirmed). Experimental evidence demonstrated that these variants lead to gain-of-function of the late repolarizing, KCNJ2-encoded I k1 current in the heart and abbreviation of the action potential duration.25 These data were considered sufficient for classifying the gene–disease relationship of KCNJ2 as Moderate.

Genes disputed as a cause for short QT syndrome

Four genes encoding calcium (CACNA1C, CACNA2D1, CACNB2) or sodium (SCN5A) channels were classified as Disputed genes for SQTS (Figure 2). The main limitation of published data associating these genes with SQTS was the absence of a typical SQTS phenotype in isolation, with a Brugada ECG pattern in addition to a commonly recognized relatively abbreviated QT interval seen in BrS cases observed in three reported probands with a CACNA1C variant, one proband with a CACNB2 variant and one proband with a SCN5A variant. The GCEP concluded that these were BrS cases and therefore not scored, though it should be noted that previous gene curation of the calcium channel genes for BrS by this GCEP also resulted in a Disputed classification.4 Similarly, another case with a CACNA1C variant was found to have hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without clinical findings typical of SQTS. Two other reported variants in SQTS cases are observed too frequently in the Ashkenazi Jewish population to be monogenic causes of SQTS (prevalence of <1/10 000)—CACNA2D1:p.Ser755Thr with an Ashkenazi prevalence of 1/50 and CACNA1C:p.Arg1977Gln (1/800) (see gene summaries in Supplementary material online for details of these reports).

Variants in SLC22A5 cause AR primary systemic carnitine deficiency (PSCD), a syndrome characterized by hypoketotic hypoglycaemia, hyperammonemia, liver dysfunction, hypotonia, and cardiomyopathy.26 Nevertheless, homozygote or compound heterozygote variants have been identified in unexplained SCD or resuscitated cardiac arrest cases without overt extra-cardiac manifestations.27 , 28 Furthermore, a short QT interval has been demonstrated in a carnitine-deficient mouse model27 as well as in patients with PSCD.27 , 28 Importantly, however, the QT interval in these patients returns to normal with carnitine supplementation treatment,27 , 28 leading the GCEP to conclude that PSCD is a metabolic and reversible SQTS-mimic and that the relationship between SLC22A5 and true SQTS is Disputed (Figure 2).

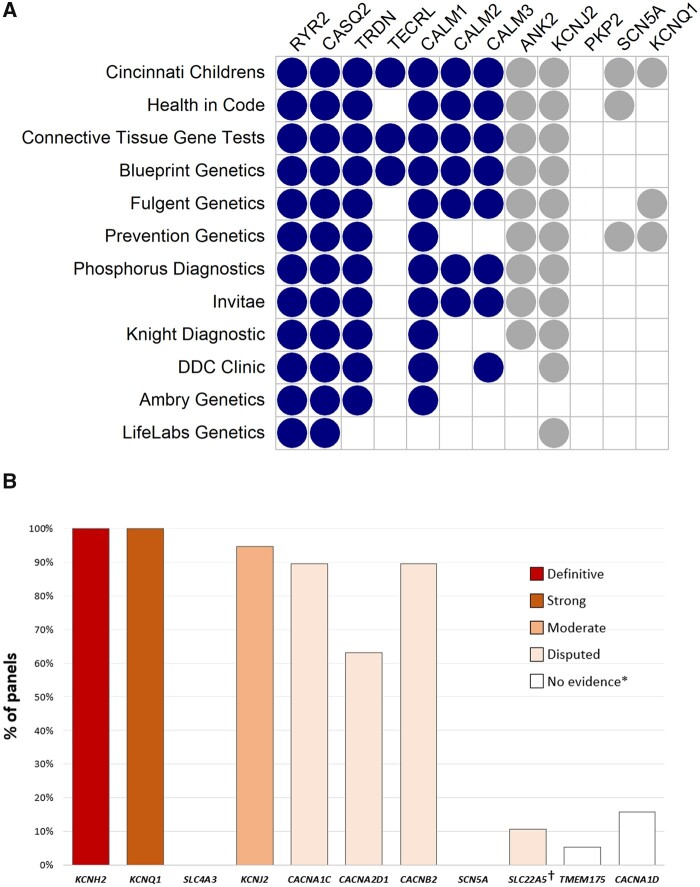

Gene panel coverage

Twelve CPVT-specific and 19 SQTS-specific clinical genetic testing panels were listed in the NCBI Genetic Testing Registry29 (Figure 3, full details in Supplementary material online). RYR2 and CASQ2 were included in every CPVT testing panel, with the other Definitive/Moderate genes present in 25–92% and the Disputed genes present in 0–92%. KCNQ1 was present in 3/12 panels despite having no reported relationship with CPVT. Of the validated SQTS genes, KCNH2 and KCNQ1 were included in all SQTS testing panels, KCNJ2 in 95% but SLC4A3 was present in none and the SQTS-mimic gene SLC22A5 was included in only 11%. The Disputed calcium channel genes were included in most panels (63–89%), with CACNA1D present in 15% despite no reports in the medical literature suggesting a relationship with SQTS.

Figure 3.

Composition of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and short QT syndrome genetic testing panels. Data derived from the NCBI Genetic Testing Registry (as of December 2020) excluding single gene or broad arrhythmia/cardiac panels. (A) Validated catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia genes are shown in dark blue, disputed and non-catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia genes are shown in grey. Although PKP2 is not currently on any panels, it was included in this reappraisal process based on a recent report where truncating variants were identified in patients previously diagnosed with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. (B) Percentage of genetic panels including genes previously reported as causing short QT syndrome. SLC4A3 (moderate evidence) was not present in any of the panels we investigated. *These are candidate genes with no evidence for gene–disease relationship and were not curated by the Biocurator teams. †This gene is a short QT syndrome-mimic and should be considered in short QT syndrome-specific genetic panels. See text for further details.

Discussion

An essential pre-requisite of clinical genetic testing in patients with conditions like CPVT and SQTS, as recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines,30 is to restrict analysis to genes with a proven role for the disease in order to avoid misinterpretation of rare variants found in genes with little evidence for disease causality. In this study, we utilized a previously published evidence-based framework6 to reappraise the genes implicated in CPVT and SQTS by evaluating the genetic, experimental, and phenotypic data in published studies. We identified seven CPVT and four SQTS genes that currently have sufficient evidence to be regarded as valid Mendelian disease genes for these disorders.

Genes disputed as causes of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and short QT syndrome based on genetic evidence

ANK2 reported for CPVT and CACNA1C and CACNA2D1 reported for SQTS represent the few genes disputed based on genetic evidence, with the reported variants now being recognized as far too common in human populations to cause these rare diseases. The reasons why CPVT and SQTS have not been encumbered with many erroneous genetic associations (in contrast to other inherited cardiac conditions4 , 5) may include the relative rarity of the conditions (∼1/10 000 for CPVT and likely rarer still for SQTS), which precludes the assembly of cohorts for candidate gene studies that led to many disputed associations in other diseases. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is also frequently observed as an early onset disease due to de novo variants or AR inheritance—pathogenic variants in such cases are easier to unambiguously identify (through trio analysis of probands and their parents) compared to later-onset diseases and AD inheritance. In contrast, the majority of Disputed classifications for both CPVT and SQTS related to disputing the phenotypes of the reported cases and the adjudication of the GCEP that these were unlikely to be CPVT/SQTS.

Genes disputed as causes of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and short QT syndrome based on phenotypic miscues

For CPVT, three genes (KCNJ2, PKP2, SCN5A) were classified as Disputed despite the likely pathogenicity of the reported variants, as the phenotypes in these reports were concluded by the GCEP to represent distinct conditions other than CPVT. Variants in KCNJ2 are causative of ATS, a condition characterized by dysmorphic features, periodic paralysis, and prominent U waves on ECG. For cases with a cardiac-restricted phenotype, distinguishing ATS from CPVT can be challenging as arrhythmia burden may increase during exercise and resemble CPVT. However, the observed high ventricular arrhythmia burden in the resting state, occasionally including the presence of bi-directional VT,15 , 31 and/or the presence of abnormal U waves or prolonged QUc on ECG,14 , 16 , 31 suggests that each of the cases reappraised in this study are likely to represent ATS lacking extra-cardiac features rather than the reported CPVT diagnosis.

Truncating variants in PKP2 were detected in 5/18 patients who had previously been diagnosed with CPVT.17 One of these patients was subsequently diagnosed with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and eventual right ventricular structural changes were observed in two others. The GCEP therefore deemed that these were highly likely to be ARVC cases in the concealed cardiomyopathy stage of the disease upon initial presentation, a conclusion indeed shared by the authors of the original study,17 and that PKP2 cannot be considered a causal gene for CPVT. The SCN5A variant p.Ile141Val was shown to segregate with an arrhythmogenic phenotype in a large Finnish pedigree (LOD score 3.56) after identification by linkage analysis and exome sequencing.18 The phenotype in this family displayed some similarities with CPVT, with individuals developing premature ventricular contractions during exercise testing (but also abundantly at rest in some), which progressed to non-sustained polymorphic VT in the majority of cases. However, the presence of features not typical of CPVT, in particular the abundant ventricular ectopy at rest in some patients, suggests that this is a distinct MEPPC arrhythmogenic phenotype that shares similarities with other MEPPC-associated gain-of-function SCN5A variants. Furthermore, the observed in vitro electrophysiological abnormalities of p.Ile141Val were comparable to those of the well-recognized MEPPC variant p.Arg222Gln.

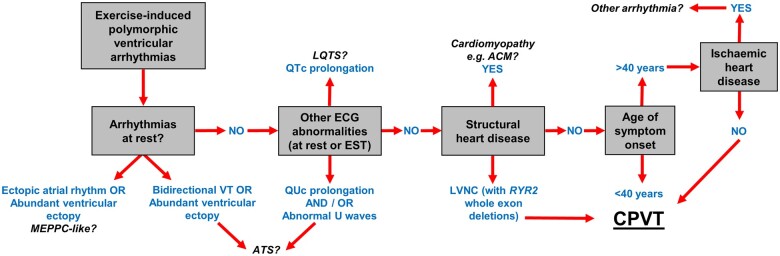

The above examples highlight the importance of accurate phenotyping and diagnosis in patients with suspected arrhythmogenic disorders like CPVT, for both research studies seeking to identify novel gene–disease relationships and applying and interpreting routine CPVT genetic testing in the clinic. The detection of ventricular arrhythmias upon exercise testing, but not at rest, is the essential diagnostic feature for CPVT cases but other clinical characteristics atypical for CPVT should also be considered during evaluation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Factors and clinical characteristics to consider for the accurate diagnosis of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Demonstrating polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias during exercise testing but not at rest is an essential pre-requisite for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia diagnosis but other potential causes should be excluded. These include arrhythmias detected by characteristic electrocardiogram abnormalities (long QT syndrome, Andersen–Tawil syndrome), cardiomyopathies detected by structural changes in the heart (ACM) and ischaemic heart disease. ACM, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; CPVT, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; ECG, electrocardiogram; EST, exercise stress test; LQTS, long QT syndrome; LVNC, left ventricular non-compaction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Four of the genes implicated in SQTS were also classified as Disputed based on the patient phenotype in the published studies. For three of these genes (CACNA1C, CACNB2, and SCN5A), most of the reported cases had BrS with a relatively short QT interval and were not regarded by the GCEP as an SQTS phenotype. SLC22A5, which causes the AR disorder PSCD, is a unique case of an SQTS-mimic as biallelic SLC22A5 variants may rarely present with an isolated cardiac phenotype that resembles SQTS. While the molecular mechanism of this observation is not clearly understood, it should be considered in the genetic investigation of SQTS cases despite being Disputed as a cause of SQTS, given that the phenotype can be readily treated with orally supplemented carnitine.

Validated short QT syndrome genes

Four causal genes for SQTS were identified by this reappraisal: KCNH2 with Definitive evidence and three other genes (KCNQ1, KCNJ2, and SLC4A3) with substantial evidence leading to classifications ranging from Moderate to Strong (Table 2 and Figure 2). Given the rarity of SQTS, it is not surprising that a paucity of cases precluded these genes from being classified as definitive. KCNQ1 is the second most common gene reported in SQTS after KCNH2. Interestingly, almost all cases were found to harbour the same genetic variant (p.Val141Met) with a similar clinical presentation. While the pathogenicity of this variant is irrefutable, there is no convincing evidence of pathogenicity for other KCNQ1 variants with SQTS. Unlike the other established SQTS genes, SLC4A3 does not encode a cardiac potassium channel but rather a chloride–bicarbonate exchanger. Loss-offunction of this exchanger is thought to lead to intracellular alkalinisation, which shortens the cardiac action potential duration. This gene’s recent association with SQTS by a single study may explain its absence from SQTS commercial genetic testing panels (Figure 3B). Nevertheless, the evidence supporting this gene’s relationship with SQTS was seen as robust by the GCEP, with future reports of SLC4A3 variants in SQTS cases likely to strengthen the level of evidence.

Validated definitive catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia genes: RYR2, TRDN, CASQ2, and TECRL

RYR2 (AD inheritance) and CASQ2 (AR inheritance) were first reported as causes of CPVT nearly 20 years ago, with repeated descriptions of both familial and de novo cases robustly establishing their pathogenic role in CPVT. Experimental data in both in vitro systems and animal models have established the net effect of these genetic defects in promoting spontaneous cytosolic fluxes of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) during adrenergic stimulation in cardiac diastole, leading to delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) and triggered arrhythmias. TRDN (encoding triadin) and TECRL (encoding trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA reductase like) were more recently reported with AR CPVT and classified as Definitive genes based on multiple reports of patients with biallelic loss-of-function variants and supporting experimental data including TRDN knockout mice and iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes harbouring TECRL variants. These genes encode proteins regulating RYR2-mediated SR calcium release and their loss-of-function provokes the classical CPVT cellular physiology of inappropriate calcium release and DADs. TRDN-related disease may also present with a phenotype of LQTS on resting ECGs, in addition to exercise-provoked polymorphic VT seen in CPVT, and thus, may present a mixed clinical picture in some cases. Similarly, some cases related to TECRL variants have been described with prolonged QT, although not to the degree as seen with TRDN.

The CALM gene family and the limitations of the ClinGen gene curation template

The family of CALM genes represents a rare phenomenon in human genetics. These genes, CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3, encode the identical protein, all are functionally active and highly expressed in the myocardium but are localized to distinct chromosomal regions within the human genome. The encoded protein calmodulin plays a critical role in intracellular calcium regulation, directly binding to the L-type calcium channel, RYR2, and the delayed rectifier potassium channel (Iks) in its role in modulating calcium levels and action potential duration. Variants in any one of these genes may cause a phenotype of LQTS, and numerous reports have described a phenotype of CPVT in isolation, or a hybrid phenotype of LQTS and CPVT features (prolonged QT at rest, and exercise-induced polymorphic ventricular arrhythmia). Most interestingly, 93% of these CALM variants are de novo and frequently the identical de novo variant is present in more than one of the CALM genes. When curated for the phenotype of isolated CPVT using the standard ClinGen curation template, gene validity scores of moderate, moderate and limited were obtained for the three CALM genes, respectively. However, the GCEP considered significant limitations of the curation template in the context of the rare scenario of the CALM gene family encoding identical proteins, and the common observations of repeated, paralogous de novo variants in these genes. In particular, the application of usual scoring for de novo variants in the template is designed for single gene–single protein scenarios and does not account for or recognize the added strength of evidence when identical de novo variants occur in any of three genes that encode the same protein sequence. Of the 18 isolated CPVT phenotypes described for the CALM genes, 14 cases from two families are due to the CALM1 p.Asn54Ile variant. Fewer cases are reported due to CALM2 or CALM3 variants. However, the GCEP considered the observation of an identical de novo variant at amino acid residue Asp132 seen on six occasions in patients with CALM-related LQTS or CPVT (or hybrid) phenotypes. The p.Asp132Glu amino acid change, described in CALM2 and CALM3 patients with clinical features consistent with CPVT, was considered as indisputable evidence for disease causation for CPVT from either CALM2 or CALM3 in addition to CALM1. Variants at Asp132 are absent from gnomAD for all 3 CALM genes, and the probability of this identical de novo variant occurring in each of these genes presenting with CALM-related LQTS or an isolated CPVT phenotype as reported for p.Asp132Glu in CALM3 would be extraordinarily low. In addition, all three CALM genes have demonstrated the classical CPVT physiology in functional experiments when mutant CALMs are expressed, including the CALM3 p.Ala103Val variant reported in CPVT, which demonstrated provocation of DADs when expressed in mice myocytes. As such, the GCEP concluded that all three CALM genes have unequivocal evidence for causation of isolated CPVT, in addition to LQTS and hybrid phenotypes.

Clinical implications

The classification of genes reported herein should be considered when designing clinical genetic testing panels for CPVT and SQTS and interpreting variants identified in such patients. Based on these findings, we recommend that CPVT panels should include, but be restricted to, all genes with Definitive to Moderate evidence (i.e. RYR2, CASQ2, TRDN, TECRL, CALM1, CALM2, CALM3) and be employed for patients diagnosed with CPVT by standard exercise stress testing (or Holter monitoring in younger patients). For cases where this is unavailable or where atypical features are observed, and where no causative variants have been identified with the standard seven gene panel, an expanded panel could be applied to identify potentially pathogenic variants in non-CPVT genes that cause conditions that may be misinterpreted as CPVT. Results from such expanded panels should be cautiously analysed, however, and interpreted in the context of the phenotype of the patient being tested, e.g. if a KCNJ2 variant is detected, does the patient have cardiac or non-cardiac features that would suggest a diagnosis of ATS?

For SQTS, although the three genes encoding cardiac calcium channels (CACNA1C, CACNB2, CACNA2D1) are included in the majority of commercial SQTS panels (Figure 3B), rare variants in these genes will almost certainly be interpreted as variants of unknown significance (VUS) (a not uncommon occurrence given that rare missense variants in these genes will be found in ∼8% of the general population). Their inclusion in SQTS-specific panels would not increase the yield of the panel but would add to turnaround time and, more importantly, may lead to anxiety and uncertainty if a VUS is reported. As the relationship of CACNB2 and CACNA2D1 with BrS has also been previously disputed, the inclusion of these genes in wider arrhythmia or pan-cardiac genetic panels should also be reconsidered. It is noteworthy that the genetic evidence supporting the relationship of KCNH2, KCNQ1, and SLC4A3 with SQTS is based on very few variants (KCNH2:p.Thr618Ile, KCNH2:p.Asn588Lys, KCNQ1:p.Val141Met, and SLC4A3:p.Arg370His) identified in multiple patients. Therefore, other rare variants in these genes should be cautiously interpreted, particularly for the potassium channel genes as gain-of-function variants in KCNH2, KCNQ1, and KCNJ2 that cause SQTS are expected to be very rare.

Lessons learned in gene discovery research

Most of the Disputed genes described here and in previous reappraisals were identified using candidate gene approaches. Although this remains a valuable application to gene discovery where large family pedigrees are unavailable, significant limitations exist in the absence of appropriately controlled study designs. Rare variants are known to be collectively relatively common for many genes and therefore will often be incidentally detected. While demonstrating an excess of rare variants in case vs. control cohorts supports disease causation, this has been rarely performed in published candidate gene studies and moreover requires very large case cohorts for less prevalent disease genes. Where human genetic evidence is limited, in vitro functional assays are often used to support the pathogenicity of rare variants. However, rare control variants are almost never functionally assessed and therefore the threshold of functional abnormality necessary to cause disease is often unknown, particularly for human physiological parameters that span a range of normal values, such as the QTc interval (360–450 ms). Rare variants may display functional differences in vitro but not reach a threshold of difference needed to induce disease, as has been observed for variants whose pathogenicity was previously supported by functional assays but are now recognized as being too common to cause rare disease.4 Due to these limitations, the candidate gene approach needs to consider innovative designs and appropriate control experiments to elevate the evidence of genes proposed to cause rare disease.

Conclusions

This reappraisal of gene–disease relationships for CPVT and SQTS provides an evidence-based analysis of which genes can currently be considered as valid disease genes and should be included in clinical genetic testing panels. Our findings suggest that a systematic, evidence-based approach should be applied to assess the validity of any reported or novel gene–disease relationships before use in patient care and that both genetic and phenotype data should be carefully assessed when investigating novel genetic causes of these conditions.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative (CVON PREDICT2 to A.A.M.W.); the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (#408226 to M.H.G.); the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health (U41HG009650 to R.E.H.); the Wellcome Trust (107469/Z/15/Z and 200990/A/16/Z to J.S.W.); and the British Heart Foundation (RE/18/4/34215 to J.S.W.). This research was funded, in part, by the Wellcome Trust (107469/Z/15/Z and 200990/A/16/Z). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Conflict of interest: A.A.M.W. is a member of the advisory board of LQT Therapeutics. J.S.W. is a consultant for MyoKardia Inc. and Foresite Labs. J.G. is a full time employee of Invitae. However, none of these entities participated in this study. All other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material, as well as on the ClinGen website (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Roddy Walsh, Department of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Heart Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Arnon Adler, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 585 University Avenue, Toronto, ON M5G 2N2, Canada.

Ahmad S Amin, Department of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Heart Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Emanuela Abiusi, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and Istituto di Medicina Genomica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go F. Vito 1, Rome 00168, Italy.

Melanie Care, Division of Cardiology, Toronto General Hospital, The Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 200 Elizabeth St, Toronto, ON M5G 2C4, Canada; Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, 1 King's College Cir, Toronto, ON M5S 1A8, Canada.

Hennie Bikker, Department of Clinical Genetics, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam 1105 AZ, The Netherlands.

Simona Amenta, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and Istituto di Medicina Genomica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go F. Vito 1, Rome 00168, Italy.

Harriet Feilotter, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Queen's University, 88 Stuart Street, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6, Canada.

Eline A Nannenberg, Department of Clinical Genetics, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam 1105 AZ, The Netherlands.

Francesco Mazzarotto, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Viale Pieraccini 6, Florence 50139, Italy; Faculty of Medicine, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Dovehouse St, London SW3 6LY, UK; Cardiovascular Research Centre, Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospitals, Sydney St, London SW3 6NP, UK.

Valentina Trevisan, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and Istituto di Medicina Genomica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go F. Vito 1, Rome 00168, Italy.

John Garcia, Invitae Corp., 1400 16th St, San Francisco, CA 94103, USA.

Ray E Hershberger, Division of Human Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, The Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 473 W 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, The Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 473 W 12th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Marco V Perez, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Stanford University, 300 Pasteur Dr, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Amy C Sturm, Geisinger Genomic Medicine Institute, 100 N Academy Ave, Danville, PA 17822, USA.

James S Ware, Faculty of Medicine, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Dovehouse St, London SW3 6LY, UK; Cardiovascular Research Centre, Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospitals, Sydney St, London SW3 6NP, UK; Cardiovascular Genomics and Precision Medicine, MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences, Imperial College London, Du Cane Rd, London W12 0NN, UK.

Wojciech Zareba, Cardiology Unit of the Department of Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642, USA.

Valeria Novelli, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and Istituto di Medicina Genomica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, L.go F. Vito 1, Rome 00168, Italy.

Arthur A M Wilde, Department of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Heart Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Michael H Gollob, Division of Cardiology, Toronto General Hospital, The Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 200 Elizabeth St, Toronto, ON M5G 2C4, Canada.

References

- 1. Gollob MH, Redpath CJ, Roberts JD. The short QT syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:802–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pflaumer A, Davis AM. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Lung Circ 2012;21:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazzanti A, Kanthan A, Monteforte N, Memmi M, Bloise R, Novelli V, Miceli C, O'Rourke S, Borio G, Zienciuk-Krajka A, Curcio A, Surducan AE, Colombo M, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Novel insight into the natural history of short QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1300–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hosseini SM, Kim R, Udupa S, Costain G, Jobling R, Liston E, Jamal SM, Szybowska M, Morel CF, Bowdin S, Garcia J, Care M, Sturm AC, Novelli V, Ackerman MJ, Ware JS, Hershberger RE, Wilde AAM, Gollob MH; National Institutes of Health Clinical Genome Resource Consortium. Reappraisal of reported genes for sudden arrhythmic death. Circulation 2018;138:1195–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adler A, Novelli V, Amin AS, Abiusi E, Care M, Nannenberg EA, Feilotter H, Amenta S, Mazza D, Bikker H, Sturm AC, Garcia J, Ackerman MJ, Hershberger RE, Perez MV, Zareba W, Ware JS, Wilde AAM, Gollob MH. An international, multicentered, evidence-based reappraisal of genes reported to cause congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation 2020;141:418–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strande NT, Riggs ER, Buchanan AH, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, DiStefano M, Dwight SS, Goldstein J, Ghosh R, Seifert BA, Sneddon TP, Wright MW, Milko LV, Cherry JM, Giovanni MA, Murray MF, O'Daniel JM, Ramos EM, Santani AB, Scott AF, Plon SE, Rehm HL, Martin CL, Berg JS. Evaluating the clinical validity of gene-disease associations: an evidence-based framework developed by the clinical genome resource. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:895–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Tiso N, Memmi M, Vignati G, Bloise R, Sorrentino V, Danieli GA. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2001;103:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Postma AV, Denjoy I, Hoorntje TM, Lupoglazoff J-M, Da CA, Sebillon P, Mannens MMAM, Wilde AAM, Guicheney P. Absence of calsequestrin 2 causes severe forms of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res 2002;91:e21–e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapplinger JD, Pundi KN, Larson NB, Callis TE, Tester DJ, Bikker H, Wilde AAM, Ackerman MJ. Yield of the RYR2 genetic test in suspected catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and implications for test interpretation. Circ Genomic Precis Med 2018;11:e001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ng K, Titus EW, Lieve KV, Roston TM, Mazzanti A, Deiter FH, Denjoy I, Ingles J, Till J, Robyns T, Connors SP, Steinberg C, Abrams DJ, Pang B, Scheinman MM, Bos JM, Duffett SA, van der Werf C, Maltret A, Green MS, Rutberg J, Balaji S, Cadrin-Tourigny J, Orland KM, Knight LM, Brateng C, Wu J, Tang AS, Skanes AC, Manlucu J, Healey JS, January CT, Krahn AD, Collins KK, Maginot KR, Fischbach P, Etheridge SP, Eckhardt LL, Hamilton RM, Ackerman MJ, Noguer FRI, Semsarian C, Jura N, Leenhardt A, Gollob MH, Priori SG, Sanatani S, Wilde AAM, Deo RC, Roberts JD. An international multicenter evaluation of inheritance patterns, arrhythmic risks, and underlying mechanisms of CASQ2-catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 2020;142:932–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gray B, Bagnall RD, Lam L, Ingles J, Turner C, Haan E, Davis A, Yang P-C, Clancy CE, Sy RW, Semsarian C. A novel heterozygous mutation in cardiac calsequestrin causes autosomal dominant catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1652–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crotti L, Spazzolini C, Tester DJ, Ghidoni A, Baruteau A-E, Beckmann B-M, Behr ER, Bennett JS, Bezzina CR, Bhuiyan ZA, Celiker A, Cerrone M, Dagradi F, Ferrari GD, Etheridge SP, Fatah M, Garcia-Pavia P, Al-Ghamdi S, Hamilton RM, Al-Hassnan ZN, Horie M, Jimenez-Jaimez J, Kanter RJ, Kaski JP, Kotta M-C, Lahrouchi N, Makita N, Norrish G, Odland HH, Ohno S, Papagiannis J, Parati G, Sekarski N, Tveten K, Vatta M, Webster G, Wilde AAM, Wojciak J, George AL, Ackerman MJ, Schwartz PJ. Calmodulin mutations and life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias: insights from the International Calmodulinopathy Registry. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2964–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohler PJ, Splawski I, Napolitano C, Bottelli G, Sharpe L, Timothy K, Priori SG, Keating MT, Bennett V. A cardiac arrhythmia syndrome caused by loss of ankyrin-B function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:9137–9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tester DJ, Arya P, Will M, Haglund CM, Farley AL, Makielski JC, Ackerman MJ. Genotypic heterogeneity and phenotypic mimicry among unrelated patients referred for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia genetic testing. Heart Rhythm 2006;3:800–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kimura H, Zhou J, Kawamura M, Itoh H, Mizusawa Y, Ding WG, Wu J, Ohno S, Makiyama T, Miyamoto A, Naiki N, Wang Q, Xie Y, Suzuki T, Tateno S, Nakamura Y, Zang WJ, Ito M, Matsuura H, Horie M. Phenotype variability in patients carrying KCNJ2 mutations. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012;5:344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kalscheur MM, Vaidyanathan R, Orland KM, Abozeid S, Fabry N, Maginot KR, January CT, Makielski JC, Eckhardt LL. KCNJ2 mutation causes an adrenergic-dependent rectification abnormality with calcium sensitivity and ventricular arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:885–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tester DJ, Ackerman JP, Giudicessi JR, Ackerman NC, Cerrone M, Delmar M, Ackerman MJ. Plakophilin-2 truncation variants in patients clinically diagnosed with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and decedents with exercise-associated autopsy negative sudden unexplained death in the young. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Swan H, Amarouch MY, Leinonen J, Marjamaa A, Kucera JP, Laitinen-Forsblom PJ, Lahtinen AM, Palotie A, Kontula K, Toivonen L, Abriel H, Widen E. Gain-of-function mutation of the SCN5A gene causes exercise-induced polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014;7:771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Villafañe J, Fischbach P, Gebauer R. Short QT syndrome manifesting with neonatal atrial fibrillation and bradycardia. Cardiology 2014;128:236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellocq C, Ginneken A. V, Bezzina CR, Alders M, Escande D, Mannens MMAM, Baró I, Wilde AAM. Mutation in the KCNQ1 gene leading to the short QT-interval syndrome. Circulation 2004;109:2394–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moreno C, Oliveras A, la Cruz A. D, Bartolucci C, Muñoz C, Salar E, Gimeno JR, Severi S, Comes N, Felipe A, González T, Lambiase P, Valenzuela C. A new KCNQ1 mutation at the S5 segment that impairs its association with KCNE1 is responsible for short QT syndrome. Cardiovasc Res 2015;107:613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu Z-J, Huang Y, Fu Y-C, Zhao X-J, Zhu C, Zhang Y, Xu B, Zhu Q-L, Li Y. Characterization of a Chinese KCNQ1 mutation (R259H) that shortens repolarization and causes short QT syndrome 2. J Geriatr Cardiol 2015;12:394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rothenberg I, Piccini I, Wrobel E, Stallmeyer B, Müller J, Greber B, Strutz-Seebohm N, Schulze-Bahr E, Schmitt N, Seebohm G. Structural interplay of KV7.1 and KCNE1 is essential for normal repolarization and is compromised in short QT syndrome 2 (KV7.1-A287T). HeartRhythm Case Rep 2016;2:521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thorsen K, Dam VS, Kjaer-Sorensen K, Pedersen LN, Skeberdis VA, Jurevičius J, Treinys R, Petersen IMBS, Nielsen MS, Oxvig C, Morth JP, Matchkov VV, Aalkjær C, Bundgaard H, Jensen HK. Loss-of-activity-mutation in the cardiac chloride-bicarbonate exchanger AE3 causes short QT syndrome. Nat Commun 2017;8:1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Priori SG, Pandit SV, Rivolta I, Berenfeld O, Ronchetti E, Dhamoon A, Napolitano C, Anumonwo J, Barletta M. D, Gudapakkam S, Bosi G, Stramba-Badiale M, Jalife J. A novel form of short QT syndrome (SQT3) is caused by a mutation in the KCNJ2 gene. Circ Res 2005;96:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nezu J, Tamai I, Oku A, Ohashi R, Yabuuchi H, Hashimoto N, Nikaido H, Sai Y, Koizumi A, Shoji Y, Takada G, Matsuishi T, Yoshino M, Kato H, Ohura T, Tsujimoto G, Hayakawa J, Shimane M, Tsuji A. Primary systemic carnitine deficiency is caused by mutations in a gene encoding sodium ion-dependent carnitine transporter. Nat Genet 1999;21:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roussel J, Labarthe F, Thireau J, Ferro F, Farah C, Roy J, Horiuchi M, Tardieu M, Lefort B, François Benoist J, Lacampagne A, Richard S, Fauconnier J, Babuty D, Guennec JL. Carnitine deficiency induces a short QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gélinas R, Leach E, Horvath G, Laksman Z. Molecular autopsy implicates primary carnitine deficiency in sudden unexplained death and reversible short QT syndrome. Can J Cardiol 2019;35:1256.e1–1256.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rubinstein WS, Maglott DR, Lee JM, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ, Ovetsky M, Hem V, Gorelenkov V, Song G, Wallin C, Husain N, Chitipiralla S, Katz KS, Hoffman D, Jang W, Johnson M, Karmanov F, Ukrainchik A, Denisenko M, Fomous C, Hudson K, Ostell JM. The NIH genetic testing registry: a new, centralized database of genetic tests to enable access to comprehensive information and improve transparency. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D925–D935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kawamura M, Ohno S, Naiki N, Nagaoka I, Dochi K, Wang Q, Hasegawa K, Kimura H, Miyamoto A, Mizusawa Y, Itoh H, Makiyama T, Sumitomo N, Ushinohama H, Oyama K, Murakoshi N, Aonuma K, Horigome H, Honda T, Yoshinaga M, Ito M, Horie M. Genetic background of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in Japan. Circ J 2013;77:1705–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material, as well as on the ClinGen website (https://www.clinicalgenome.org/).