Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to evaluate relationships between time-in-range (TIR 63–140 mg/dL), glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, and the glucose management indicator (GMI) in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes.

Research Design and Methods:

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from 27 women with type 1 diabetes were collected prospectively throughout pregnancy. Up to 90-days of CGM data were correlated with point-of-care HbA1c levels measured in the clinic at each trimester. GMI levels were calculated using a published regression formula. Liner models were used to compare TIR, HbA1c, and GMI by each trimester.

Results:

There was a significant negative correlation between TIR and HbA1c; each 10% increase in TIR was associated with a 0.3% reduction in HbA1c. The correlation between TIR and HbA1c was stronger (r = −0.8) during the second and third trimesters than during the first trimester (r = −0.4). There was good correlation between TIR and GMI during each trimester (r = 0.9 for each trimester). The relationship between GMI and HbA1c especially during second (r = 0.8) and third trimesters (r = 0.8) was strong.

Conclusion:

In the first trimester, the correlation between HbA1c level and TIR was relatively small, while that of TIR and GMI was very strong, thus GMI may better reflect glycemic control than HbA1c in early pregnancy. Each 10% increase in TIR was associated with a 0.3% reduction in HbA1c throughout pregnancy, which was lower than other published studies in nonpregnant populations reporting a 0.5%–0.8% reduction in HbA1c. Further studies are needed to understand the relationship between TIR and GMI and how GMI may affect maternal and fetal complications. Clinical Trial Registration number: NCT02556554.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Continuous glucose monitoring, Pregnancy, Glucose management indicator, Time in range

Introduction

The relationship between glycated hemoglobin A1c levels (HbA1c) in pregnancy and gestational health outcomes in women with diabetes and their infants is well known, such that higher HbA1c levels increase the risk of adverse outcomes.1 It is because of this strong relationship that multiple guidelines across the world recommend achieving and maintaining HbA1c levels of <6% (42 mmol/mol) or 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) during pregnancy.2,3 However, there are concerns about HbA1c measurements during pregnancy as physiological changes during pregnancy and iron deficiency may affect HbA1c levels.4–6 Moreover, HbA1c does not provide information on day to day glycemic fluctuation and if used alone, it may be insufficient to optimally guide intensive insulin management during pregnancy in women with diabetes. Pregnant women with preexisting diabetes are followed more frequently than nonpregnant populations, usually weekly to monthly throughout gestation; therefore, even more frequent laboratory HbA1c measurements may not reflect the changes in glucose control in real-time.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has been shown to improve glycemic control and pregnancy outcomes in women with type 1 diabetes.7,8 A large randomized controlled trial showed improved fetal outcomes with the use of CGM compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose in women with type 1 diabetes.8 Interestingly, for this cohort of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes whose third trimester HbA1c levels were in the goal range, it was likely the higher time-in-range (TIR; 63–140 mg/dL) and lower time spent in hyperglycemia (>140 mg/dL) in CGM users that contributed to improved fetal outcomes as the difference in HbA1c levels between groups was relatively small (−0.19% favoring CGM, P = 0.0207), suggesting roles of CGM and TIR beyond HbA1c in the management of diabetes during pregnancy.

Indeed, one of the advantages of CGM use in pregnancies associated with diabetes is the ability to assess not just overall glycemic control but also glycemic variability. Moreover, some studies have shown that increased glycemic variability, as measured by standard deviation, coefficient of variation, and J-index, is associated with some gestational health outcomes such as preeclampsia and large-for-gestational age infants.7,9–11 However, the associations between CGM-derived metrics and pregnancy-related outcomes are not always consistent from study to study. More studies are needed to determine what CGM measures have the highest clinical applicability in pregnancies associated with diabetes and to examine CGM measures that have not been studied at all in pregnancies associated with diabetes.

The Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) is an increasingly used mathematical formula to estimate HbA1c from CGM sensor glucose levels and is now incorporated in the ambulatory glucose profile that has become the standard way of reporting CGM data.12,13 The GMI was developed and validated from CGM data of randomized controlled clinical trials that excluded pregnant women with diabetes.12 Thus, GMI has not been validated in pregnant patients with diabetes. Considering this knowledge gap, we aimed to examine the association between HbA1c levels and GMI by each trimester in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Study design and definition of variables

We conducted secondary analyses with data collected from a pilot study comparing glycemic control in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes using CGM alone, CGM with remote monitoring, and not using CGM whose methods have been previously published.14,15 Maternal and fetal outcomes were previously reported.14 In brief, women with type 1 diabetes were recruited in a single center (Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes, BDC), open-label, investigator-initiated study to evaluate maternal glycemic control, fear of hypoglycemia, and health outcomes in pregnant women not using CGM (CGM Alone group, retrospectively identified), using CGM alone (CGM Alone group, prospectively enrolled), and using CGM with remote monitoring by family or friends (CGM Share group, prospectively enrolled).14,15 This protocol was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02556554).

Data were collected on 28 women in the CGM groups (n = 13 CGM Alone and n = 15 CGM Share). All participants in the CGM groups were given Dexcom G4 or G5 sensors, which are real-time CGM systems that provide glucose readings every 5 min. Glucose readings can be shared by the users with their family members and/or friends using Share™ technology. In comparison with the laboratory reference method, the Dexcom G4 platinum® CGM system with 505 software and the Dexcom G5 CGM system had a mean absolute relative difference of 9% and required two calibrations daily.16 Participants used their personal blood glucose meters and were instructed to calibrate the CGM system per the manufacturer's instructions.

We exported raw CGM data for the entire study duration from each pregnant participant for these analyses. CGM-based TIR (63–140 mg/dL), time above range (TAR; >140 mg/dL), and time below range (TBR; <63 mg/dL) were defined per the 2019 international consensus guidance on TIR and other CGM metrics.17 GMI was calculated using a regression formula previously published.12 In the first trimester, we used all available data from study enrollment until the end of the trimester to calculate GMI. We used 90 days of data to calculate GMI in the second trimester. In the third trimester, we used all data from start of the trimester until delivery. Point-of care HbA1c (DCA Vantage Analyzer; Siemens Health care Diagnostics, Dublin, Ireland) levels were measured in all participants every month of pregnancy at the BDC, and the mean for each trimester was calculated. The point-of-care HbA1c machine was calibrated daily.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of all variables were examined before analysis. Descriptive statistics presented include mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, frequencies, and percentages for categorical variables. Linear models were used to compare glycemic measures by trimester and to examine the association between glycemic measures. Linear models with interaction terms between trimester and glycemic measures were used to test whether the relationship between two measures of glycemia differed by trimester. Bland-Altman plots were used to assess agreement between GMI and HbA1c by trimester. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, Vienna). Summary statistics for CGM data were calculated using the R package cgmanalysis.18 All tests are two-sided with significance at 5% level.

Results

Of 28 participants, 1 was excluded due to inadequate data, therefore, a total of 27 participants were included in the final analyses. Among the 27 participants, 7 were enrolled in preconception and 20 were enrolled in pregnancy. More information about the background population and a flowchart detailing enrollment procedures have been previously published.14 The mean age of participants was 27.9 ± 5.3 years and mean body mass index was 26.7 ± 4.2 kg/m2. Most participants were non-Hispanic whites (77.8%) and the mean preconception HbA1c was 8.0% ± 1.8% (64 mmol/mol). All participants had a singleton pregnancy. Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Pregnant Women with Type 1 Diabetes

| Characteristics | N = 27 |

|---|---|

| Age at baseline, mean ± SD, years | 27.9 ± 5.3 |

| Gestational age at first pregnancy visit, mean ± SD, weeks | 6.6 ± 2.0 |

| Diabetes duration, mean ± SD, years | 14.8 ± 7.5 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 26.7 ± 4.2 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 21 (77.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (14.8) |

| Asian/Oriental | 1 (3.7) |

| Other | 1 (3.7) |

| Preconception A1c, mean ± SD, % (mmol/mol) | 8.0 (64) ± 1.8 |

| Insulin pump therapy, n (%) | 18 (66.7) |

| Insulin basal dose, mean ± SD, units | 32.3 ± 18 |

| Insulin bolus dose, mean ± SD, units | 24.3 ± 11.9 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1 (3.7) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 2 (7.4) |

| Past smoker, n (%) | 11 (40.7) |

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

The mean HbA1c levels and CGM-based TIR, TAR, and TBR by each trimester are presented in Table 2. Despite there being no significant change in TIR between the first, second, and third trimesters, HbA1c was higher during the first trimester compared to the second and third trimesters.

Table 2.

Mean HbA1c Levels and Continuous Glucose Monitoring -Based Glycemic Profiles by Each Trimester in Pregnant Women with Type 1 Diabetes

| First trimester (n = 27) | Second trimester (n = 27) | Third trimester (n = 26) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of days of CGM data, mean ± SD | 34 ± 17 | 66 ± 20 | 47 ± 21 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, % (mmol/mol) | 7.1 (54) ± 1.0 | 6.2 (44) ± 0.5 | 6.4 (46) ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| GMI, % | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Mean sensor glucose, mg/dL | 130 ± 17 | 134 ± 19 | 133 ± 18 | 0.7 |

| TIR (63–140 mg/dL), % | 58.9 ± 12.7 | 56.2 ± 12.8 | 58.0 ± 13.5 | 0.7 |

| TAR (>140 mg/dL), % | 34.7 ± 13.6 | 37.9 ± 14.0 | 37.5 ± 14.2 | 0.7 |

| TBR (<63 mg/dL), % | 6.4 ± 3.4 | 6.1 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 0.1 |

| No. of women achieving TIR ≥70%, n (%) | 6 (23) | 5 (19) | 5 (21) | 0.9 |

All data presented as mean ± SD.

CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; GMI, glucose management indicator; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range; TIR, time in range.

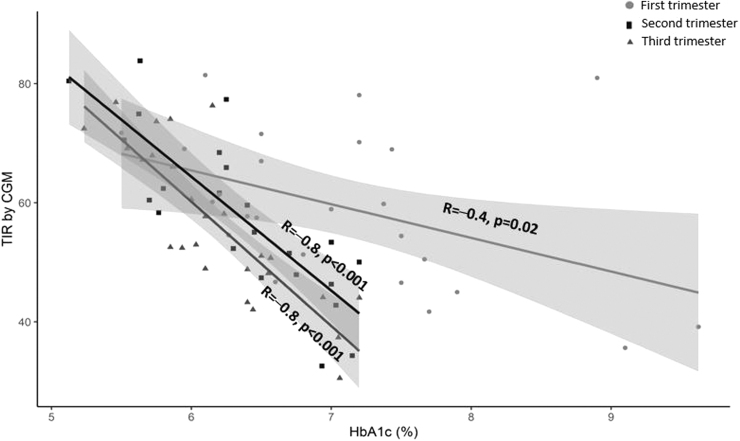

The relationships between TIR and HbA1c level in each trimester are shown in Figure 1. Higher TIR was significantly correlated with lower HbA1c levels. Correlations were stronger (r = −0.8, P < 0.001) during the second and third trimesters than during the first trimester (r = −0.4, P = 0.02). In a linear model with TIR as the outcome, the interaction between HbA1c and trimester was significant (P < 0.001), indicating that the relationship between TIR and HbA1c differed by trimester (Supplementary Table S1). Each 10% increase in TIR was associated with 0.3% reduction in HbA1c that is lower than published studies in nonpregnant populations reporting a 0.5%–0.8% reduction in HbA1c (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Correlation between CGM time-in-range (63–140 mg/dL) and HbA1c in each trimester. CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c.

Table 3.

The Relationships Between TIR and HbA1c and GMI by Each Trimester in Pregnant Women with Type 1 Diabetes Compared to Published Relationships Between TIR and HbA1c in Nonpregnant Individuals with Diabetes

| TIR | First trimester |

Second trimester |

Third trimester |

Nonpregnant subjects with DMa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (N = 26) | GMI (N = 26) | HbA1c (N = 27) | GMI (N = 27) | HbA1c (N = 25) | GMI (N = 24) | HbA1c | |

| 10 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | NR |

| 20 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.1 | 9.4 |

| 30 | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 0.04 | 8.9 |

| 40 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.04 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.03 | 8.4 |

| 50 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.04 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.03 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.02 | 7.9 |

| 60 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.03 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.03 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.01 | 7.4 |

| 70 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.05 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.04 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.03 | 7.0 |

| 80 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.04 | 6.5 |

| 90 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.05 | 6.0 |

Data are presented as least squares mean ± SE from a linear model relating HbA1c and GMI to TIR.

Relationship between TIR and HbA1c among nonpregnant subjects with diabetes. Data from Beck et al.23; only mean HbA1c was included in this table.

NR, not reported.

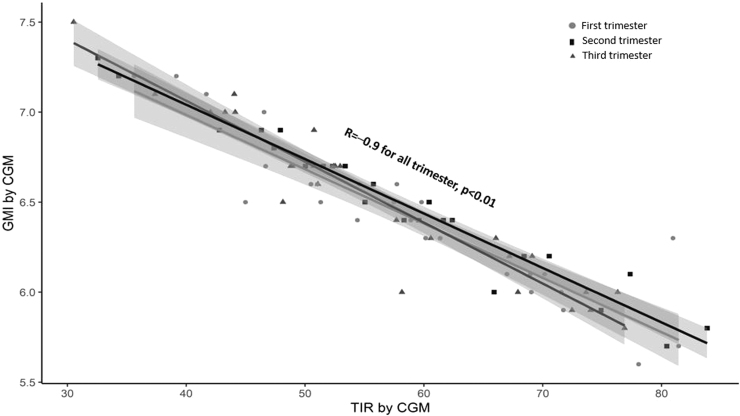

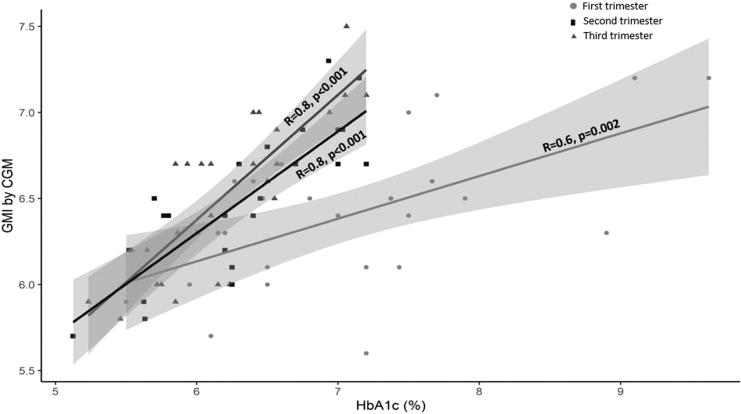

TIR and its correlations with GMI in each trimester are shown in Figure 2. There were good correlations between TIR and GMI during each trimester (r = −0.9 for all trimesters, P < 0.001). In a linear model with TIR as the outcome, the interaction between GMI and trimester was not significant (P = 0.211, Supplementary Table S1), indicating that the association between TIR and GMI was similar across trimesters, The relationships between GMI and estimated HbA1c levels are shown in Figure 3. There were strong relationships between GMI and HbA1c levels, especially during the second and third trimesters (r = 0.6 for first trimester, P = 0.02 and r = 0.8 for second and third trimesters, P < 0.001). In a linear model with GMI as the outcome, the interaction between HbA1c and trimester was significant (P < 0.001, Supplementary Table S1), supporting the conclusion that the relationship between GMI and HbA1c differed by trimester. Bland-Altman plots showing agreement of GMI and HbA1c are included in Supplementary Figure S1.

FIG. 2.

Correlation between CGM time-in-range (63–140 mg/dL) and GMI in each trimester. GMI, glucose management indicator.

FIG. 3.

Correlations between GMI and HbA1c in each trimester.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate correlations between GMI and HbA1c levels with CGM-based TIR by trimester in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes. Our study found strong correlations between TIR and GMI and between HbA1c levels and GMI. These findings suggest that GMI may be used in pregnancies associated with diabetes.

The mean TIR achieved in our cohort was 58% and remained unchanged throughout the pregnancy. This percent of TIR values in pregnancy is below the recommended goal of TIR >70%.17 However, our findings are similar to other studies reporting TIRs of 50%–68% in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes using CGM with or without insulin pump therapy,7,8,19–21 suggesting that many women do not achieve the desired target proportion of glucose values within the goal TIR during pregnancy. Unlike other studies,7,8,21 we did not see an increase in TIR from the first to the third trimester.7,8 The reasons for this are unclear. It is possible that our cohort had a relatively static TIR because we enrolled pregnant women earlier in gestation compared to other studies (mean gestational age at the first pregnancy visit ∼6.5 weeks in our study compared to ∼10 weeks in other studies).7,8 In addition, seven of the women enrolled in our study in preconception. The largest randomized control trial of CGM use in type 1 diabetes pregnancies, CONCEPTT, found that TIR did not increase as much in the group planning pregnancy (TIR 41% at baseline and 45%–49% at 24 weeks) compared to those enrolled in gestation (TIR 51%–53% at baseline and 65%–72% at 34 weeks).8 Thus, the relatively large proportion of women with preconception planning in our cohort may have affected the changes in TIR over time.

Use of the GMI in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes is still a relatively new area of research. In another study evaluating CGM accuracy in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes in the second and third trimesters,22 secondary analyses were performed to assess glycemic control and glycemic variability in pregnancies associated with diabetes (data were presented at the American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions19). In that cohort, among 20 pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, the mean HbA1c was 6.3% ± 1.4% (45 mmol/mol) and the GMI was 6.3%. GMI data were derived from 10 days of CGM wear. While correlative statistics were not performed, these data suggested high correlation between these measurements taken later in gestation.19

Our study showed good correlations between TIR and HbA1c levels during the second and third trimesters, but a weaker correlation during the first trimester. TIR and GMI reflected better glycemic control than HbA1c levels during the first trimester, which may be due to various reasons: (1) the change in glucose is generally rapid during the first trimester due to intensive insulin treatment, (2) physiological changes such as alteration in red blood cell turnover, and (3) iron deficiency or supplements may play a role in dissociations between TIR and HbA1c levels. However, GMI was lower than HbA1c levels during first trimester because GMI is a mathematical formula that estimates HbA1c from CGM glucose readings and therefore is not influenced by physiologic and other factors. In addition, in this study the CGM data used were for the last few weeks of the first trimester and thus may more accurately reflect real-time glycemic control compared to the HbA1c, which reflects the previous 3 months from preconception to first trimester. The Bland-Altman plots in the Supplementary Figure S1 suggest that the differences between GMI and HbA1c during the first trimester were larger for higher mean values of HbA1c and GMI; however, there were relatively few observations with a mean > 7.5.

Each 10% increase in TIR was associated with a 0.3% reduction in HbA1c. The relationship between changes in TIR with reductions in HbA1c levels did not change over time. In a study by Beck et al.,23 each 10% increase in TIR in subjects with diabetes (n = 545 enrolled in four randomized controlled trials) was associated with ∼0.5% reduction in HbA1c, while another study by Vigersky and McMahon24 showed a 0.8% reduction in HbA1c with each 10% increase in TIR (n = 1137 reviewed from 18 articles). Both studies included large numbers of nonpregnant subjects with diabetes. Findings from our study suggest that the HbA1c reduction with each 10% increase in TIR is lower in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes compared to the published reporting of a 0.5%–0.8% reduction in HbA1c with a similar increase in TIR in nonpregnant subjects with diabetes. It should also be noted that our results are based on a sample size of 27 pregnant women enrolled prospectively in one study, which is much smaller than the results of the above-stated studies using data from multiple clinical trials.23,24 Our findings are in agreement with a previous study reporting good correlation between mean glucose and HbA1c, but a shallower slope in pregnant women with diabetes compared to nonpregnant women with diabetes.11

The full applicability of GMI in pregnancies associated with diabetes, in terms of clinical care and prediction of adverse gestational health outcomes, has yet to be determined. In an exploratory analysis using data from the same cohort of this article, we found that GMI was associated with preeclampsia in the first trimester (6.2% absent vs. 6.8% present, P = 0.003) and in the second trimester (6.3% absent vs. 7.0% present, P = 0.001).25 GMI was also associated with lower gestational age at delivery (−0.1% decrease in GMI per 1 week greater gestational age, P = 0.0046), but not with infant birth weight.25 Future studies that include complete CGM data during organogenesis and that have adequate power to examine major maternal and fetal health outcomes, including congenital anomalies and fetal losses, would be needed to compare the standard metric (HbA1c) to newer metrics (GMI and TIR) in terms of both clinical relevance and predictive modeling.

The prospective follow-up of all women from the first trimester through delivery and the continuous collection of CGM data throughout the pregnancy are major strengths of the study. However, the small sample size and single center inclusion are some of the limitations of our study. In particular, these are secondary analyses performed with data from a small pilot study, thus the reliability of the results is limited. In addition, our HbA1c measurements were performed with point-of-care analyses, rather than venous samples. Outside pregnancy, point-of-care HbA1c has a high correlation to venous blood samples,26 but may have a small negative bias in pregnancy.27 Despite this limitation, POCT A1C testing with the DCA Vantage analyzer has been shown to be reasonably precise and accurate in a nonpregnant population,28 and POCT A1C testing has been used in large randomized controlled trials for screening and inclusion29,30. There were numerous blood glucose meters used in this study, as a standard meter was not provided by the study team. The differences in the blood glucose measurements, based on differences in blood glucose meters, may have affected the accuracy of calibration measurements and of GMI calculations. Finally, because of the length of time the CGM was worn, we did not use the standard data cleaning settings in the cgmanalysis package, and therefore, the percent of time the CGM was worn each day was not calculated. Our findings may not be generalizable and future studies are needed to validate our findings.

In summary, GMI correlates with TIR better than HbA1c during the first trimester. During the second and third trimesters, both GMI and HbA1c have good correlations with TIR. Findings of our study are clinically important as this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between GMI, TIR, and HbA1c by each trimester in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes. GMI has now been incorporated into CGM downloads, and therefore, it is easy for clinicians to translate mean glucose to GMI as an estimated HbA1c. Future studies with complete data in organogenesis and larger sample sizes are needed to fully determine the applicability of GMI and TIR clinically and as possible predictors of adverse gestational health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants of this study. We thank Mary Voelmle and Satish Garg, MD for assistance with study procedures and study design, respectively. We thank Tim Vigers for his contribution to the computer programming for CGM data analysis.

Authors' Contributions

V.S. wrote the article draft and edited the final document. R.G. curated data and reviewed the article. J.K.D. curated data, validated data, and reviewed the article. P.J. curated data, validated data, and reviewed the article. J.K.S.B. curated data, validated data, reviewed, and edited the article. L.P. curated data, performed statistical analyses, contributed to article writing, and reviewed and edited the article. S.P. wrote the protocol, curated data, analyzed some of the data, contributed to article writing, and reviewed and edited the article. S.P. is the guarantor of this work and has access to the data.

Author Disclosure Statement

V.N.S. reports receiving research grants from NIH (NIDDK and NIAMS), Eli-Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Dexcom, Insulet, and JDRF. V.N.S. had served on advisory board for Sanofi. S.P. reports research funding from Dexcom, Inc., Eli Lilly, JDRF, Leona & Helmsley Charitable Trust, NIDDK, and Sanofi, medical advisory board for Medtronic MiniMed, Inc., and consulting for the JAEB center. R.G., L.P., P.J., J.D., and J.S.B reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Funding Information

This was an investigator-initiated study, in part, supported by Dexcom, Inc., through the Board of Regents at the University of Colorado Denver. Dexcom, Inc., is the manufacturer of the CGM device and the Share software assessed here. This study was supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780. Its contents are the authors' sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent Dexcom, Inc., or official NIH views. The funders had no role in data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, et al. : Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1991–2002. (In English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. : Diabetes and pregnancy: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:4227–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. 14. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes care 2020;43(Supplement 1):S183–S192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. : HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1200–1201. (In English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herranz L, Saez-de-Ibarra L, Grande C, Pallardo LF: Non-glycemic-dependent reduction of late pregnancy A1C levels in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1579–1580.(In English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinha N, Mishra TK, Singh T, Gupta N: Effect of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Lab Med 2012;32:17–22. (In English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kristensen K, Ogge LE, Sengpiel V, et al. : Continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: an observational cohort study of 186 pregnancies. Diabetologia 2019;62:1143–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feig DS, Donovan LE, Corcoy R, et al. : Continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes (CONCEPTT): a multicentre international randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2017;390:2347–2359. (In English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGrath RT, Glastras SJ, Seeho SK, et al. : Association between glycemic variability, HbA1c, and large-for-gestational-age neonates in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40:e98–e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy HR, Howgate C, O'Keefe J, et al. : Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: a 5-year national population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9:153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Law GR, Gilthorpe MS, Secher AL, et al. : Translating HbA(1c) measurements into estimated average glucose values in pregnant women with diabetes. Diabetologia 2017;60:618–624. (In English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergenstal RM, Beck RW, Close KL, et al. : Glucose management indicator (GMI): a new term for estimating A1C from continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2275–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carlson AL, Criego AB, Martens TW, Bergenstal RM: HbA(1c): the glucose management indicator, time in range, and standardization of continuous glucose monitoring reports in clinical practice. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2020;49:95–107. (In English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Polsky S, Garcetti R, Pyle L, et al. : Continuous glucose monitor use with and without remote monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Polsky S, Garcetti R, Pyle L, et al. : Continuous glucose monitor use with remote monitoring reduces fear of hypoglycemia in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2020;14:191–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailey TS, Chang A, Christiansen M: Clinical accuracy of a continuous glucose monitoring system with an advanced algorithm. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:209–214. (In English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. : Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603. (In English) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vigers T, Chan CL, Snell-Bergeon J, et al. : cgmanalysis: an R package for descriptive analysis of continuous glucose monitor data. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polsky S, Levy C, Zhang X, et al. : Differences in time-in-range, glycemic variability, and the glucose management indicator in pregnant women with type 1 (T1D), type 2 (T2D), and gestational diabetes (GDM). American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions. virtual: Diabetes; 2020:LB-76. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stewart ZA, Wilinska ME, Hartnell S, et al. : Day-and-night closed-loop insulin delivery in a broad population of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1391–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kjölhede K, Berntorp K, Kristensen K, et al. : Glycemic, maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with type 1 diabetes using continuous glucose monitoring during pregnancy—pump vs multiple daily injections, a secondary analysis of an observational cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020. (In English). [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1111/aogs.14039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castorino K, Polsky S, O'Malley G, et al. : Performance of the Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitoring system in pregnant women with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020;22:943–947. (In Englsih). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, Cheng P, et al. : The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019;13:614–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vigersky RA, McMahon C: The relationship of hemoglobin A1C to time-in-range in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buschur E, Campbell K, Pyle L, et al. : Exploratory analysis of glycemic control and variability over gestation among pregnant women with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:768–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nathan DM, Griffin A, Perez FM, et al. : Accuracy of a point-of-care hemoglobin A1c assay. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019;13:1149–1153. (In English). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Culliney K, McCowan LME, Okesene-Gafa K, et al. : Accuracy of point-of-care HbA1c testing in pregnant women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;58:643–647. (In English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whitley HP, Yong EV, Rasinen C: Selecting an A1C point-of-care instrument. Diabetes Spectr 2015;28:201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aleppo G, Ruedy KJ, Riddlesworth TD, et al. : REPLACE-BG: a randomized trial comparing continuous glucose monitoring with and without routine blood glucose monitoring in adults with well-controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017;40:538–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pratley RE, Kanapka LG, Rickels MR, et al. : Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on hypoglycemia in older adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;323:2397–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.