As we enter the 28th month of the ongoing devastating COVID-19 pandemic, the reality remains that WHO and the world's public health systems were unprepared, with COVID-19 causing more than 494 million cases and more than 6 million deaths worldwide as of April 5, 2022. A phenomenal amount of data has been generated in various formats across continents, which, if analysed methodically, could inform future pandemic preparedness, improve management, and enhance public health interventions and operational capacities. However, research studies so far have focused on geographically restricted cohorts or incomplete national surveillance data that are not reflective of the global picture. In The Lancet, the COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators1 have substantially decreased this gap by publishing the largest, most comprehensive exploratory analyses to date of estimates of daily infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with COVID-19 preparedness.

A strength of the study is the large dataset covering the period Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021, from 177 countries and territories and 181 subnational locations. For associations with both incidence and mortality, the authors analysed measures of pandemic preparedness, including 12 indicators of preparedness and response, seven indicators of health-system capacity, and ten other demographic, social, and political conditions. Furthermore, using a unique study design the authors controlled for demographic, biological, economic, and environmental variables associated with COVID-19 outcomes, including age, seasonality, population density, income, and health risks to identify contextual factors subject to policy control. They also adjusted inputs for under-reporting of COVID-19 outcomes, and use of population data estimates generated by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD).

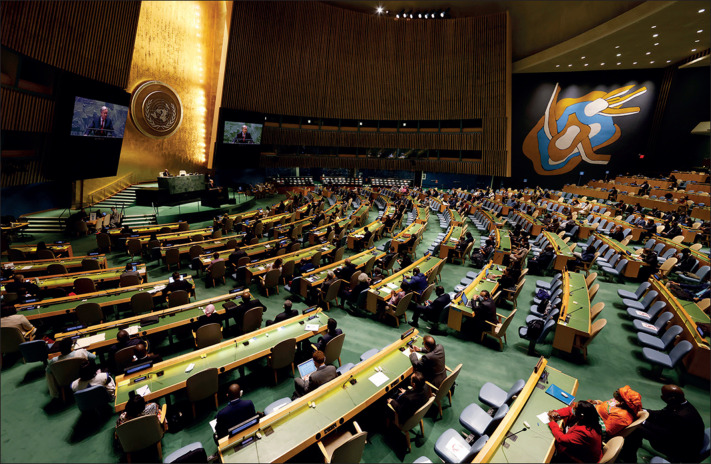

© 2022 Pool/Pool/Getty Images

There were several limitations of the study clearly delineated by the authors. Although they controlled for several key confounders, they did not cover all confounders. The estimates they report might have been affected by the varied data sources such as population and expert opinion surveys, government statistics, and modelled estimates. Furthermore, the study design was not intended to show causal relationships. However, the key findings of the study are relevant for public health systems, health-care workers, and policy makers worldwide.

First, there were large variations in differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality rates across countries and continents, even among countries within close geographical proximity. Contrary to what is assumed, low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries that rank low on public health preparedness and access to health care had lower infection rates and deaths compared with high-income countries such as the USA and France. This supports findings of an analysis of 26 countries reporting their first COVID-19 cases imported from China where the Global Health Security index and Joint External Evaluation score for health preparedness did not correlate with the countries’ COVID-19 detection response time and mortality outcome.2 Additional research is now needed to better understand within and between countries, and between continents, the variability in COVID-19 outcomes, including data on the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant (B.1.1.529).

Second, the level of trust in governments, interpersonal trust, and less government corruption were directly proportional to fewer infections and higher vaccination rates in high-income and middle-income countries. The findings indicate that if societies had had trust in governments, the world would have experienced 13% fewer infections. For social trust—ie, trust in other people around individuals—the effect would be even larger, with 40% fewer infections globally. For future pandemic preparedness, the level of trust a government earns will be crucial to mount more effective responses and increase public confidence in infection control recommendations. Improving trust will require minimising corruption and effective risk communication and community engagement strategies during public health crises, especially in settings with historically low levels of government and interpersonal trust.3, 4, 5 Since the success of these strategies is intimately tied to addressing fundamental social and economic inequalities in society, long-term political commitments to addressing these inequalities appear essential.

Third, GBD researchers have brought to light important knowledge gaps due to varying quality and quantity of data from across the world. There is a dire need for a universal approach to uniformly collect more comprehensive, quality, and accurate data to guide development of reliable metrics for health systems and national pandemic preparedness and response. Other research, political, and scientific groups have published analyses of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health systems and lessons learnt and have their own recommendations for future pandemic preparedness.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

In an era of decolonising global health,11 the IHME GBD collaboration has over the years shown visionary leadership in being more inclusive of global participation of researchers and stakeholders for collation and analyses of health metrics. An opportunity arises for IHME to take global leadership of transferring skills, technology, and expertise, and help build capacity at source for collecting data uniformly and analyses of health metrics on surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation. These areas are intrinsically political and resource issues must be addressed by both funders and researchers of health metrics enterprises. Furthermore, studies using actual and real-time data at source are required to make appropriate updated models, which will require changing from established knowledge and dogma of previous infectious disease epidemics, and a mindset change from WHO and other global public health bodies.

For worldwide COVID-19 data see https://covid19.who.int/

We declare no competing interests. FN and AZ are co-directors of the Pan-African Network on Emerging and Re-Emerging Infections (PANDORA-ID-NET; https://www.pandora-id.net/) funded by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) within the EU Horizon 2020 Framework Programme. They also acknowledge support from EDCTP Central Africa Clinical Research Network (CANTAM-3; http://cantam.net/en/). AZ is a UK National Institute for Health Research senior investigator and a Mahathir Science Award and EU-EDCTP Pascoal Mocumbi Prize laureate.

References

- 1.COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: an exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. Lancet. 2022;399:1489–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haider N, Yavlinsky A, Chang YM, et al. The Global Health Security index and Joint External Evaluation score for health preparedness are not correlated with countries' COVID-19 detection response time and mortality outcome. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e210. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OECD Trust in government. https://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm

- 4.OECD First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: a synthesis. January, 2022. www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/first-lessons-from-government-evaluations-of-covid-19-responses-a-synthesis-483507d6

- 5.Haldane V, Jung AS, Neill R, et al. From response to transformation: how countries can strengthen national pandemic preparedness and response systems. BMJ. 2021;375 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27:964–980. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herby J, Jonung L, Hanke S. A literature review and meta-analysis of the effects of lockdowns on COVID-19 mortality. Lockdowns on COVID-19 Mortality, The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ris/jhisae/0200.html

- 8.The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response COVID-19: make it the last pandemic. 2021. https://theindependentpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/COVID-19-Make-it-the-Last-Pandemic_final.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Shiffman J, Shawar YR. Strengthening accountability of the global health metrics enterprise. Lancet. 2020;395:1452–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapata N, Ihekweazu C, Ntoumi F, et al. Is Africa prepared for tackling the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic? Lessons from past outbreaks, ongoing pan-African public health efforts, and implications for the future. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.049. published online Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwete X, Tang K, Chen L, et al. Decolonizing global health: what should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Glob Health Res Policy. 2022;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s41256-022-00237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]