Abstract

Background:

Animal experiments indicate that environmental factors, such as cigarette smoke, can have multigenerational effects through the germline. However, there is little data on multigenerational effects of smoking in humans. We examined the associations between grandmothers’ smoking while pregnant and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in her grandchildren.

Methods:

Our study population included 53,653 Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II) participants (G1), their mothers (G0), and their 120,467 live-born children (G2). In secondary analyses, we used data from 23,844 mothers of the nurses who were participants in the Nurses’ Mothers’ Cohort Study (NMCS), a sub-study of NHS-II.

Results:

The prevalence of G0 smoking during the pregnancy with the G1 nurse was 25%. ADHD was diagnosed in 9,049 (7.5%) of the grandchildren (G2). Grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with increased odds of ADHD among the grandchildren (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2), independent of G1 smoking during pregnancy. In the Nurses’ Mothers’ Cohort Study, odds of ADHD increased with increasing cigarettes smoked per day by the grandmother (1–14 cigarettes: aOR=1.1; 95% CI, 1.0–1.2; 15+: aOR=1.2; 95% CI, 1.0–1.3), compared with non-smoking grandmothers.

Conclusions:

Grandmother smoking during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of ADHD among the grandchildren.

Keywords: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, cigarette smoke, prenatal exposures, multigenerational effects, germline cells

INTRODUCTION

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most prevalent neurodevelopmental disorders, affecting approximately 7% of children worldwide,1,2 and is characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity.3,4 Although ADHD is highly heritable, environmental factors are estimated to account for 10%−40% of ADHD ocurrence.3 Given the early onset of ADHD, the prenatal environment has been hypothesized to play an important role in the development of ADHD,3 including exposure to tobacco smoke,5 although there is controversy over whether the association is causal.6–8

Animal research has found that effects of in utero nicotine exposure can be passed to multiple subsequent generations, perhaps via epigenetic changes. These effects have included hyperactivity and other behaviors suggestive of ADHD,9–11 and could be a different mechanism than those underlying other effects on the developing fetus. However, in contrast with maternal smoking, the association between grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy and grandchild ADHD has received little attention. Only one study has looked at grand-maternal smoking, although the focus of that study was maternal smoking.12 Grand-maternal smoking was included as a presumed check on confounding, with the assumption that it could not have a causal effect. Given the animal evidence, this assumption may not be correct.

In the present study, our primary goal was to examine the association between smoking during pregnancy and ADHD in the third generation (grandchildren) using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II). Our hypothesis was that the risk of ADHD among grandchildren would be higher for grandmothers who smoked during pregnancy compared with those that did not.

METHODS

Study population

The NHS-II was established in 1989 when 116,430 female registered nurses ages 25–42 years (hereafter referred to as nurses) enrolled in the study.13 We send follow-up questionnaires to participants biennially to collect updated health information.13 For the current study we refer to these nurses or NHS-II participants as generation 1 (G1), their mothers as generation 0 (G0), and their children as generation 2 (G2).

In 2001, the Nurses’ Mothers’ Cohort Study (NMCS) obtained data directly from mothers (G0) of NHS-II participants (G1). Detailed information about the prenatal, perinatal, and early-life environment of the NHS-II nurse participants (G1) was reported by 39,904 of their mothers (G0), all of whom were alive and free of cancer in 2000.14,15 Our study was approved by the institutional review board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts.

Smoking assessment

Main analyses considered smoking during the G0 pregnancy with G1 (yes, no, or don’t know) as reported in 1999 by the G1 nurse. Additional analyses considered G0 NMCS participant reporting (in 2001) of whether they smoked while pregnant with the nurse (G1) and, if yes, how many cigarettes per day (non-smoking, smoked 1–14 cig/day, and smoked 15+ cig/day), and whether their husband (hereafter, referred to as G0 grandfathers or G1 fathers) smoked. The concordance rate between G0 and G1 reporting for G0 smoking during pregnancy was 92.9% and the kappa coefficient computed for the agreement between G0 and G1 report of G0 smoking during pregnancy did not differ by G2 ADHD status. Among the nurses (G1) who answered “don’t know” about their mothers’ (G0) smoking status while pregnant with them and whose mothers (G0) also participated in the NMCS, 53.5% of their mothers (G0) reported no smoking during pregnancy, whereas 46.5% indicated smoking during pregnancy. Data on G1 smoking during pregnancy was captured for a subset of nurses on a supplemental questionnaire in 2001.

ADHD assessment

We identified ADHD cases from the 2005 and 2013 NHS-II questionnaires. G1 women were asked whether any of their children had received a doctor’s diagnosis of ADHD. In 2005, the year of birth of the child with ADHD was not asked. Therefore, our primary analyses used the 2013 report. In sensitivity analyses, we restricted to cases whose mothers also reported a child with ADHD in 2005.

Maternal reports of ADHD in their children have shown high reliability.15 We conducted a validation study in which 92 G1 participants who reported a child with ADHD in 2005 responded to the ADHD Rating Scale-IV regarding their child’s behaviors.16 All G2 girls and 81% of boys scored above the 80th percentiles.16,17

Covariates

Potential confounding factors included the grandmother (G0) and grandfather’s education and grandfather’s occupation all reported by nurses (G1) in 2005. We also considered G1 race, and year of birth, including its squared term to account for possible non-linear trends in prevalence of smoking and ADHD over time.

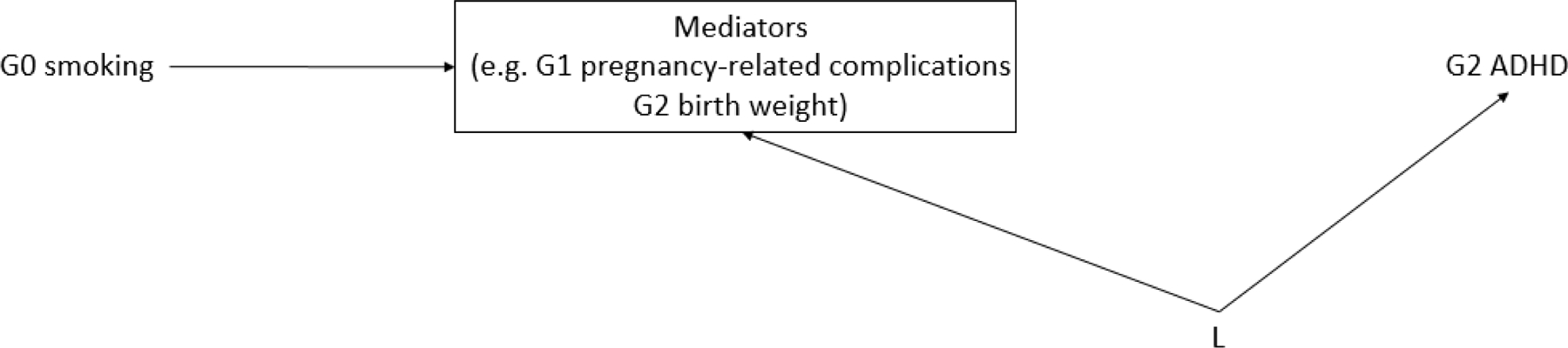

In secondary analyses, we considered the potentially mediating factors of G1 birth weight, G1 smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy with G2, G1 pre-eclampsia/toxemia, pregnancy-related high blood pressure, or gestational diabetes (each as yes/no), and G2 birth weight. In sensitivity analyses, we further considered the potential mediator–outcome confounding factors of G1 perceived socioeconomic status by ladder scale, G1 use of antidepressants reported in 1993, G1 age at G2 birth, and G1 pre-pregnancy body mass index prior to G2 birth (represented by L in Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) of possible mediator-outcome confounding by other variables (L) in the association between grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy and risk of ADHD among the grandchildren (G2).

Statistical analysis

Our analytic population was first restricted to the nurses (G1) who had a child, were not themselves adopted, and returned the 2013 NHS-II questionnaire (n=56,576). We then additionally excluded 2,796 (4.9%) G1 for whom we did not have data on mothers’ (G0) smoking during their pregnancy with G1. We then excluded any G2 who were born as part of a set of twins or triplets or in the same year as other siblings, because we could not identify which child was diagnosed with ADHD (0.5%). The final analytic sample included 53,653 G0/G1 dyads and 120,467 G2 grandchildren. Because the level of missingness was generally low in our data (< 10%), our main analyses used missing indicators. In analyses restricted to only non-missing data results were highly similar.

To account for the potentially informative clustering based on possible effects of smoking on number of children born alive,18 we calculated odds ratios (OR) for ADHD related to grandmother smoking using all grandchildren with cluster-weighted generalized estimating equation (CW-GEE) regression models with a logit link, weighted by the inverse of the number of children of each nurse (G1).19,20

Because of the concern of unmeasured confounding in the association between maternal smoking and child ADHD, and that these could also apply to grand-maternal smoking, we took several approaches to explore the possibility of unmeasured confounding. We considered maternal smoking and elements of dose–response by considering the number of cigarettes smoked per day by the grandmother and the grandfather’s smoking. While there is controversy about whether any maternal smoking–ADHD association is causal,6–8 comparing the association with ADHD between grand-maternal and maternal smoking during pregnancy can help to explore potential confounding. For example, if an association between grand-maternal smoking and grandchild ADHD is confounded, e.g. by genetics, then this confounding should also be present for maternal smoking during pregnancy in relation to ADHD in the offspring, and likely even stronger since the genetic influence on ADHD would be stronger from the mother than from the grandmother. Thus, a larger effect size for grandmother smoking than maternal smoking would not be consistent with an association only resulting from confounding by genetics. As another approach, if there is a causal effect of grand-maternal smoke exposure during pregnancy on grandchild risk of ADHD, then we might expect to see larger effect sizes with either more cigarettes smoked, or for both grandparents smoking.

Some health-risk behaviors, such as smoking, are behaviorally transmitted across generations21,22, and prenatal factors such as smoking exposure and birth weight have been linked to ADHD risk later in life.23–25 Thus, we explored whether the association between grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy and ADHD risk in grandchildren could be explained by such potential mediating factors, and if so, the proportion accounted for by the mediators. First, we used a CW-GEE model with a logit link to assess whether each potential mediating factor (G1 birth weight, G1 smoking during pregnancy, G1 alcohol use during pregnancy, G1 pregnancy-related complications, and G2 birth weight) was associated with the exposure (G0 smoking during pregnancy) and outcome (G2 ADHD). G1 birth weight was not associated with G2 ADHD (OR=0.97; 95% CI: 0.87, 1.07), but the others were at least suggestively related to both and so considered further. Second, we used logistic regression with a multiplicative interaction term between the exposure and mediator to assess the presence of exposure–mediator interaction.26 We did not find evidence of exposure–mediator interaction for any of the potential mediators (all p-values 0.24), and so used the SAS macro %mediate to estimate the proportion mediated by the included intermediate variables, applying the built-in function to obtain relative risk estimates with binomial distribution assumption and log link.27 We computed the percent difference between an unadjusted model and one adjusted for the mediators. Because this mediation method does not account for the correlation structure of our data (multiple G2 per G0/G1 dyad), we performed these analyses on a dataset for which only one grandchild (G2) per G0/G1 dyad was chosen at random.

We performed multiple sensitivity analyses. First, we calculated generalized E-values (G-values)—the magnitude of risk ratios between potential unmeasured confounding factors and both exposure (G0 smoking during pregnancy) and outcome (G2 ADHD) needed to explain away the observed association between grandmother smoking during pregnancy and ADHD among the grandchildren—for different prevalence of the unmeasured confounders.28 Second, we repeated the main analyses after excluding G2 whose mothers (G1) smoked during pregnancy to more completely remove the possibility that an association with grandmaternal smoking was only seen because of correlation with maternal smoking. Third, we used a propensity score approach to control for confounding. We estimated propensity scores for the probability of G0 smoking with the following predictors: grandmother and grandfather (G0) education, grandfather (G0) occupation, G1 race, and G1 birth year and its squared term.29 To ensure exchangeability between G2 ADHD cases versus non-cases, these analyses excluded 12 G2 non-ADHD cases (from 6 G0/G1 dyads) whose propensity scores were beyond the range of the G2 ADHD cases. Fourth, we considered only those cases reported in 2013 for whom the mother had also reported a child with ADHD on the 2005 questionnaire. In addition, the main analyses were stratified by G2 sex to explore possible sex differences in associations. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Among 120,467 G2 children, 9,049 (7.5%) were diagnosed with ADHD. Nurses (G1) reported that 13,296 (25%) of their mothers (G0) smoked while pregnant (Table 1). The associations between G0’s smoking behavior and participant characteristics is shown in Table 1. The G1 whose G0 mothers smoked while pregnant with them (G1) were slightly more likely to be white and have lower birthweight. The median number of G2 children was the same regardless of whether G0 grandmothers smoked or not, and other characteristics were generally similar by grandmother smoking during pregnancy. In the NMCS, a higher prevalence of G0 grandmother alcohol use during pregnancy was reported when the grandmother smoked during pregnancy (eTable 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the G0 (N=53,653), G1 (N=53,653) and G2 (N=120,467) generations by grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy in the Nurses’ Health Study II

| Characteristic | Grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=35,349) |

Yes (N=13,296) |

Don’t know (N=5,008) |

|

| G0 Generation | |||

| Grandmother’s education (yrs), n (%) | |||

| < 9 | 2,504 (7) | 590 (4) | 287 (6) |

| 1–3 high school | 3,449 (10) | 1,652 (12) | 567 (11) |

| 4 high school | 16,336 (46) | 5,860 (44) | 2,189 (44) |

| 1–3 college | 7,090 (20) | 3,017 (23) | 999 (20) |

| ≥ 4 college | 3,040 (9) | 1,130 (9) | 400 (8) |

| Missing | 2,930 (8) | 1,047 (8) | 566 (11) |

| Grandfather’s education (yrs), n (%) | |||

| < 9 | 3,889 (11) | 960 (7) | 439 (9) |

| 1–3 high school | 4,158 (12) | 1,628 (12) | 578 (12) |

| 4 high school | 12,415 (35) | 4,538 (34) | 1,652 (33) |

| 1–3 college | 5,155 (15) | 2,199 (17) | 755 (15) |

| ≥ 4 college | 6,449 (18) | 2,724 (21) | 889 (18) |

| Missing | 3,283 (9) | 1,247 (9) | 695 (14) |

| Grandfather’s occupation, n (%) | |||

| Blue-collar a | 16,228 (46) | 6,662 (50) | 2,419 (48) |

| Laborer | 3,896 (11) | 1,269 (10) | 544 (11) |

| Farmer | 3,020 (9) | 295 (2) | 146 (3) |

| Professional b | 8,961 (25) | 3,817 (29) | 1,272 (25) |

| No work outside home | 84 (0) | 23 (0) | 11 (0) |

| Missing | 3,160 (9) | 1,230 (9) | 616 (12) |

| Grandmother birth year, mean (SD) | 1926.8 (7.4) | 1927.3 (7.1) | 1925.6 (7.5) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3,679 (10) | 1,359 (10) | 720 (14) |

| Grandmother age (yrs) at G1 birth, mean (SD) | 27.4 (5.7) | 26.9 (5.5) | 27.6 (5.9) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3,717 (11) | 1,370 (10) | 724 (15) |

|

G1 Generation | |||

| Mother’s Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 32,971 (93) | 12,729 (96) | 4,667 (93) |

| Non-white | 1,865 (5) | 365 (3) | 274 (6) |

| Missing | 513 (2) | 202 (2) | 67 (1) |

| Mother’s Birth year, mean (SD) | 1954.3 (4.7) | 1954.3 (4.6) | 1953.3 (4.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

G1 Generation | |||

| Mother’s Birth weight, n (%) | |||

| < 5.5 lbs | 1,746 (5) | 1,365 (10) | 342 (7) |

| 5.5–9.9 lbs | 28,971 (82) | 10,313 (78) | 3,731 (75) |

| ≥ 10 lbs | 430 (1) | 55 (0) | 42 (1) |

| Missing | 4,202 (12) | 1,563 (12) | 893 (18) |

| Mother’s subjective social status in the US using a ladder scale, n (%) | |||

| Top | 13,133 (37) | 5,229 (39) | 1,797 (36) |

| Middle | 16,729 (47) | 5,961 (45) | 2,365 (47) |

| Bottom | 3,300 (9) | 1,271 (10) | 514 (10) |

| Missing | 2,187 (6) | 835 (6) | 332 (7) |

| Mother’s use of antidepressantsc, n (%) | 3,318 (9) | 1,509 (11) | 585 (12) |

|

| |||

| G2 Generation | |||

| Grandchildren | 79,742 | 29,640 | 11,085 |

| Median No. of G2d (range) | 2 (1–12) | 2 (1–11) | 2 (1–10) |

| Prenatal exposure to G1 pre-pregnancy body mass index, n (%) | |||

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 1,262 (2) | 419 (1) | 171 (2) |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 63,869 (80) | 22,884 (77) | 8,804 (79) |

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 10,919 (14) | 4,534 (15) | 1,598 (14) |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 3,692 (5) | 1,803 (6) | 512 (5) |

| Birth weight, n (%) | |||

| < 5.5 lbs | 2,748 (4) | 975 (3) | 383 (4) |

| 5.5–9.9 lbs | 74,335 (93) | 27,567 (93) | 10,311 (93) |

| ≥ 10 lbs | 1,953 (3) | 832 (3) | 304 (3) |

| Missing | 706 (1) | 266 (1) | 87 (1) |

| Mother (G1) smoking during pregnancy with G2, n (%) | |||

| No | 58,788 (74) | 20,331 (69) | 7,696 (69) |

| Yes | 5,230 (7) | 3,506 (12) | 1,149 (10) |

| Missing | 15,724 (20) | 5,803 (20) | 2,240 (20) |

| Mother (G1) alcohol use during pregnancy with G2, n (%) | |||

| No | 56,627 (71) | 19,718 (67) | 7,271 (66) |

| Yes | 7,367 (9) | 4,099 (14) | 1,571 (14) |

| Missing | 15,748 (20) | 5,823 (20) | 2,243 (20) |

| Mother (G1) pregnancy-related complications during pregnancy with G2e, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 6,417 (8) | 2,695 (9) | 893 (8) |

| Maternal (G1) age (yrs) at G2 birth, mean (SD) | 29.2 (5.0) | 29.1 (5.1) | 28.8 (5.1) |

| Missing, n (%) | 5 (0) | 4 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Birth year, mean (SD) | 1983.6 (7.4) | 1983.5 (7.4) | 1982.1 (7.4) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Sales/clerical work, service worker, mechanic/electric/skilled work, machine operator/inspector/driver, or military work

Professional, executive, or manager

Tricyclic antidepressants or Prozac reported on the 1993 questionnaire

As of 2009

Pre-eclampsia/toxemia, pregnancy-related high blood pressure, or gestational diabetes

Grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy was associated with increased odds of ADHD among the G2 generation, which was only slightly attenuated after adjustment for grandmother and grandfather (G0) education, grandfather (G0) occupation, nurse (G1) race, and nurse (G1) year of birth and its squared term (OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1–1.3) (Table 2). The odds ratio of G2 ADHD among grandmothers for whom the nurse (G1) reported “Don’t Know” about smoking was also elevated, but less so than for those reporting “Yes” for grandmother smoking.

Table 2.

Odds ratiosa (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for ADHD in third generation (G2) by grandmother’s (G0) smoking during pregnancy, among the 53,653 mothers (G1), adjusting for mother’s (G1) smoking during pregnancy in the Nurses’ Health Study II

| Exposure | Children (G2) | ADHD cases N (%) |

Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy | |||||

| No | 79,742 | 5,625 (7.1) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | |

| Yes | 29,640 | 2,567 (8.7) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.2) | |

| Don’t Know | 11,085 | 857 (7.7) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | |

| Mother (G1) smoking during pregnancy | |||||

| No | 86,815 | 6,657 (7.7) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | |

| Yes | 9,885 | 764 (7.7) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | |

| Missing | 23,767 | 1,628 (6.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 0.9) | |

Adjusted for grandmother and grandfather (G0) education, grandfather (G0) occupation, G1 race, and G1 birth year and its squared term.

Smoking of the nurse (G1) during pregnancy with her child (G2) was also associated with higher odds of ADHD in her offspring (adjusted OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0–1.2), but to a lesser degree than grandmother smoking (Table 2). When including both G0 and G1 smoking during pregnancy in the same model, point estimates for both G0 and G1 smoking remained similar.

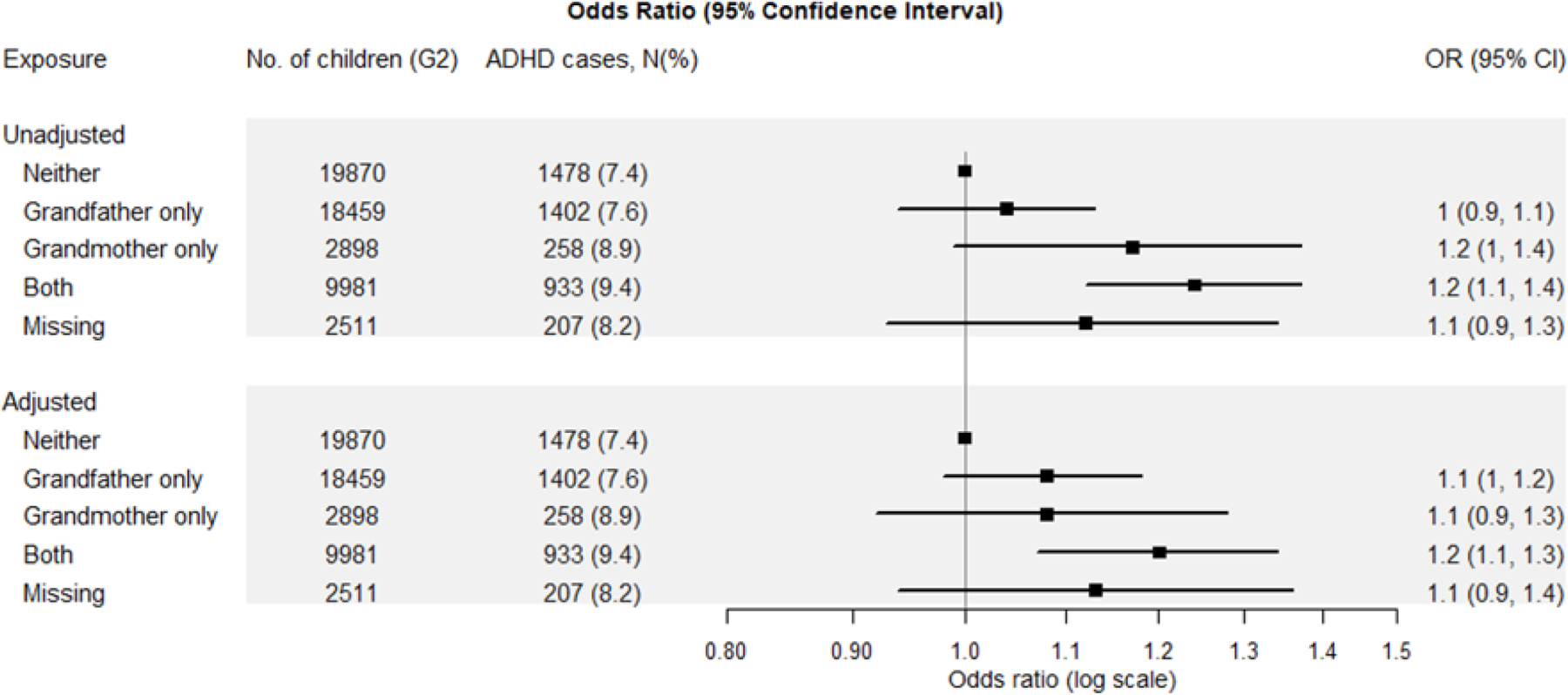

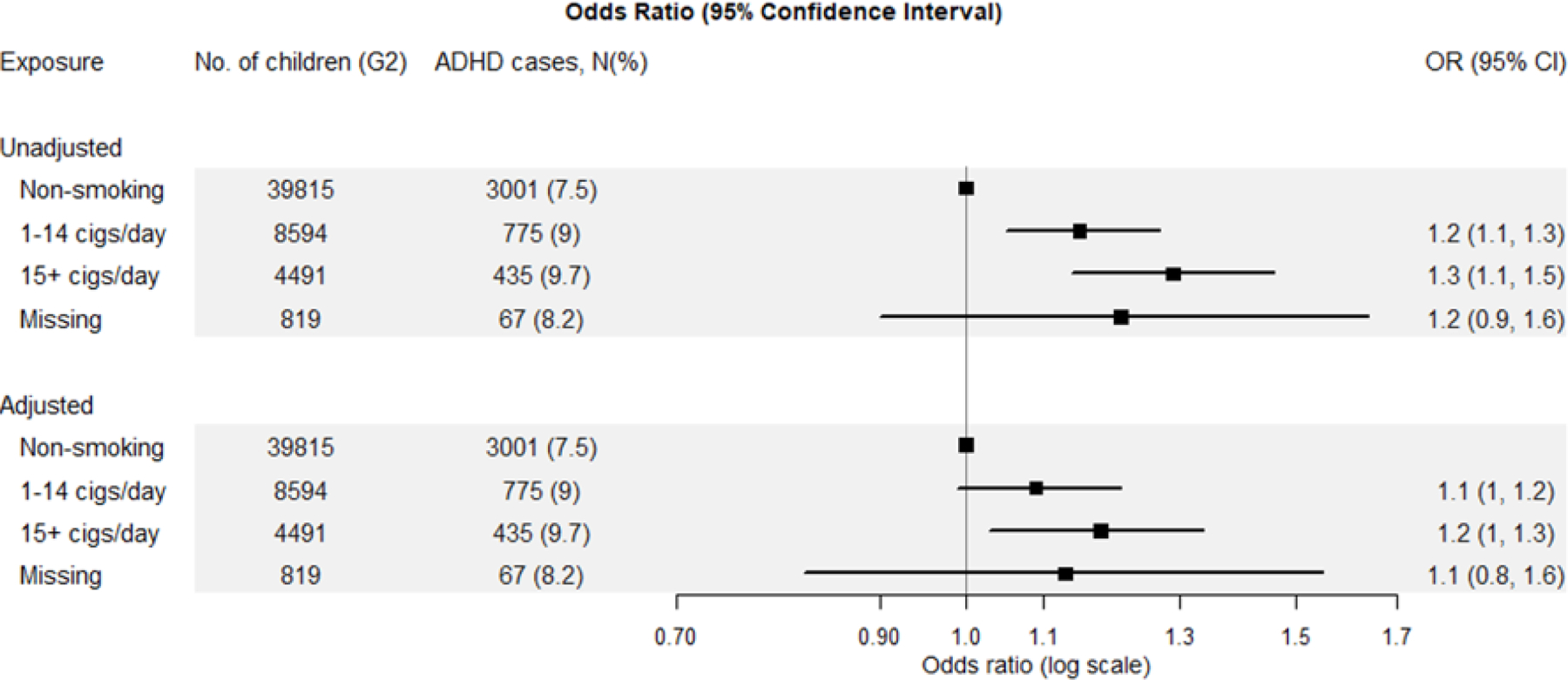

In the NMCS, we found that the OR for ADHD was slightly elevated when only the G0 grandfather smoked during the pregnancy with G1, slightly more increased when only the grandmother smoked, and most increased when both grandparents smoked (Figure 2) all compared with neither grandparent smoking. However, the confidence limits for grandmother only smoking were wide, and the effect estimate not different from grandfather only smoking in adjusted models. The OR for ADHD increased with more cigarettes smoked per day by the grandmother during pregnancy with an adjusted OR of 1.1 (95% CI: 1.0–1.2) for those who smoked 1–14 cigarettes per day and 1.2 (95% CI: 1.0–1.3) for those who smoked 15 cigarettes or more per day, compared with non-smoking grandmothers (Figure 3). In contrast, we saw no dose–response relation with cigarettes smoked per day by the mother during pregnancy (eTable 2).

Figure 2:

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for ADHD in third generation (G2) by grandparents’ (G0) smoking during pregnancy among the 23,844 grandmothers in the Nurses’ Mothers’ Cohort Study. The symbols and lines are ORs and 95% Cis, respectively. The Adjusted Model controls for grandmother (G0) race, G0 education, grandfather (G0) occupation, grandparents’ (G0) home ownership at G1 birth, G0 pre-pregnancy body mass index, G0 alcohol use during pregnancy, and maternal (G1) year of birth and its squared term.

Figure 3:

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for ADHD in third generation (G2) by grandmothers’ (G0) number of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy among the 23,844 grandmothers in the Nurses’ Mothers’ Cohort Study. The symbols and lines are ORs and 95% Cis, respectively. The Adjusted Model controls for grandmother (G0) race, G0 education, grandfather (G0) occupation, grandparents’ (G0) home ownership at G1 birth, G0 pre-pregnancy body mass index, G0 alcohol use during pregnancy, and maternal (G1) year of birth and its squared term.

In mediation analyses, the adjusted association between grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy and grandchildren’s (G2) ADHD in the population with one child per mother selected randomly was the same as in the analysis of all children (OR=1.1; 95% CI: 1.1–1.2) when not including the potential mediators (G1 smoking during pregnancy, G1 alcohol use during pregnancy, G1 pregnancy-related complications, and G2 birth weight). This OR did not change within the same level of precision (OR=1.1; 95% CI: 1.1–1.2) when the potential mediators were added to the model. The proportion of the association between G0 smoking during pregnancy and G2 ADHD explained by the selected intermediate factors was estimated to be 10.3% (4.8%, 20.5%). Further adjustment for potential mediator–outcome confounding factors did not materially change the effect estimate for G0 smoking, suggesting that mediator–outcome confounding was unlikely to have biased our mediation analyses (eTable 3).

Our calculation of G-values indicated that the association of an uncontrolled confounder with both exposure (RREU) and outcome (RRUD) would have to be 1.7 when the prevalence of the unmeasured confounder among the exposed is 100%, and as much as 3.9 when the prevalence is 10%, in order to account for our findings (eTable 4). Results were essentially unchanged in analyses that used propensity score adjustment for confounding (eTable 5). In addition, the findings remained robust when we excluded G2 whose mothers (G1) smoked during pregnancy, or when we excluded ADHD cases of mothers who did not also report a child with ADHD in 2005. There was little difference in results by G2 sex.

DISCUSSION

In this large, prospective cohort study of 53,653 female health professionals (G1) with data on their mothers (G0) and children (G2), we found that grandmother’s (G0) smoking during pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of ADHD in the grandchildren (G2). There is controversy over whether maternal smoking during pregnancy is causally related to greater risk of ADHD in her child or whether such associations seen are confounded,6–8 and similar concerns arise for grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy. However, our additional analyses to explore these concerns argued against confounding.

The association between maternal (G1) smoking during pregnancy and child (G2) ADHD was smaller in magnitude than the association with grand-maternal (G0) smoking during pregnancy, and the association with grand-maternal smoking was virtually unchanged when maternal smoking was added to the model. This pattern argues against confounding by many factors, for example, genetics. Previous literature has suggested common neurobiological factors contributing to the development of ADHD and smoking risk,30–32 but if this were confounding our G0 results, then it should confound the association with maternal (G1) smoking even more, leading to a larger effect estimate for G1 smoking since the genetics of the mother and child are closer than the grandmother and grandchild. Furthermore, if genetic confounding accounted for the observed association with grand-maternal smoking, then adjusting for maternal smoking during pregnancy (a downstream consequence of the same genetics causing the grand-maternal smoking; eFigure 1) would partly adjust for that genetic confounding, and so reduce the observed effect size for grand-maternal smoking. Yet this was not the case.33,34 Similar arguments would also apply to other types of potential confounding that are related to both G0 and G1 smoking. This also argues against the association with grand-maternal smoking being mediated through an association with maternal smoking. Furthermore, the results for grand-maternal smoking were essentially unchanged after further adjusting for the potential mediating factors, G1 pregnancy-related complications and G2 birth weight. This suggests that a different mechanism than transmission via these intermediate factors account for the association seen with grand-maternal smoking.

Our exploration of dose–response relations also argues for a causal effect of grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy. There was evidence of a dose–response relation with greater odds of ADHD with more cigarettes smoked by the grandmother during pregnancy, and to some extent by the pattern of grandparent smoking. Specifically, we found a greater risk of ADHD when both grandparents smoked during the pregnancy with G1 and lower risk when only one of the grandparents smoked compared with when neither grandparent smoked, although the distinction between grandmother only and grandfather only smoking was less clear, which may relate to misclassification of actual smoke exposure to the fetus in these cases and the large uncertainty given small numbers, particularly for grandmother only smoking. While it is possible that confounding could create such dose–response patterns, the confounding structure is likely somewhat different for numbers of cigarettes smoked by the grandmother and both grandparents smoking vs. one or none, requiring both types of confounding to be occurring to account for our findings. In addition, the odds of G2 ADHD were also elevated among grandmothers whose daughters (G1) reported “don’t know” about the grandmothers smoking, but with a lower OR than for grandmothers whose daughters reported that their mothers smoked. Among those for whom we had data, when a mother (G1) reported “don’t know” about the grandmother’s smoking, the grandmother herself reported smoking about half the time. This also fits with a causal effect of grandmother smoking that is attenuated because only half in the “don’t know” group likely actually smoked during the pregnancy with G1. While we cannot completely rule out residual confounding, a simpler explanation than all these confounding structures being just right to create these apparent dose–response relations is that the dose–response relations are driven by a true underlying causal effect of smoke exposure to the fetus during pregnancy. Furthermore, there was far less—if any—dose–response relation seen with intensity of maternal (G1) smoking and child (G2) ADHD, which, as with maternal smoking itself, likely would have been even stronger than the dose–response for grand-maternal smoking if the dose–response association with grand-maternal smoke exposure were all the result of confounding.

Animal studies have suggested multigenerational effects of in utero nicotine or smoke exposure on neurodevelopment. For instance, Zhu et al. found that prenatal nicotine exposure induced hyperactivity, a proxy for human ADHD phenotype, which was transmitted to both second and third generations via the maternal line.9 Buck et al. also demonstrated that nicotine exposure from exposing pregnant mice dams to cigarette smoke elicited hyperactivity and risk-taking behaviors in both first and second generation adolescent offspring.11

Among humans there is a paucity of data on how in utero exposures could influence the third generation, in large part related to the difficulty of following multiple generations.35 Some human studies have suggested that the effects on fetuses from tobacco smoke may extend to subsequent generations, focusing on G2 birth weight, anthropometry measures, and asthma.36–42 One study also found an association between maternal grandmother smoking during pregnancy and increased risk of autistic traits and diagnosed autism in grandchildren.43 To our knowledge, only one study, in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), has examined this relation with grandchild ADHD12. However, that study was focused on the examination of maternal smoking during pregnancy and used grand-maternal smoking as a negative control exposure44,45 with the explicit assumption that grand-maternal smoking could not have a causal effect on grandchild ADHD. If we allow that this is in fact possible as suggested by animal studies, then the MoBa results for grand-maternal smoking during pregnancy can be seen as similar to ours—a similarly increased risk of ADHD in the grandchild that is not much changed when co-adjusting for maternal smoking during pregnancy.

Several mechanisms could underlie an association between grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy and G2 ADHD. Maternal smoking during pregnancy induces DNA damage in offspring cord blood46, and prenatal exposure to maternal smoking can affect offspring DNA methylation.47–50 Oocytes that will produce the G2 generation are forming in the G1 fetus during the G0 pregnancy. Thus, G0 smoking during pregnancy could directly affect the G2 generation if it affects germline cells as it affects cord blood cells. Animal experiments suggest that epigenetic alterations of germline cells could underlie multigenerational as well as even transgenerational effects.10,11,51–57 For instance, tobacco or nicotine use is known to be endocrine disrupting, and endocrine disruptors have been found to induce heritable epigenetic modifications of the germ cells of the G1 offspring that will become the G2 generation.9,58–60

Our study has some important limitations. First, ADHD was reported by the NHS-II participants, not identified by medical record review, possibly resulting in misclassification. However, maternal report of a doctor’s diagnosis of ADHD (even among non-nurses) has been found to be quite reliable15, and we found good agreement in our validation study. There could also be error in the recall of grandmother (G0) smoking during pregnancy. If this was differentially related to grandchild ADHD, it could induce bias away from the null. However, the data on the G0 smoking during pregnancy were collected from the nurses many years before asking the nurses about ADHD in their children, thus avoiding priming of responses, and there was no suspicion of such a multigenerational association when G0 smoking was reported. Furthermore, the kappa coefficients calculated for the grandmother’s smoking during pregnancy between G0 and G1 report did not differ by G2 ADHD diagnosis status. Second, although extensive information was collected on the grandmothers to control for possible confounding, information on G0 or G1 ADHD or other neurodevelopmental disorder history as an exposure and G2 ADHD symptom severity as an outcome was not available in our data. It is possible that grandmothers’ smoking could increase risk for ADHD symptoms in the mother, which could lead the nurse (G1) to select a mate with more ADHD symptoms, increasing the genetic predisposition for ADHD in G2 offspring.61 This kind of assortative mating has been observed in the context of autism spectrum disorders.62 However, in our data we found only a weak association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and child ADHD, so if the grandmother’s smoking was similarly only weakly associated with the mother’s (G1) ADHD symptoms, then the possibility of such an influence from assortative mating might be small.

Overall, the NHS-II and the NMCS sub-study provide a unique study setting in which three generational effects can be explored, with data collected via both G0 and G1 participants. Strengths of our study include a well-characterized cohort comprised of healthcare professionals, with a high follow-up rate, which helps to avoid some selection biases. In addition, extensive data were available for adjustment, including data at the G0, G1 and G2 levels, and our results were robust to many sensitivity analyses. It should be noted, though, that the effect estimate for grandmaternal smoking was relatively modest. While this raises concern about residual confounding our G-value analysis suggests such confounding would still need to be rather strong. Further, as noted above, several of our analyses appear to argue against confounding. Alternatively, non-differential misclassification of the exposure could contribute to weakening the observed effect estimate, a possibility perhaps suggested by the weaker estimate seen for the “Don’t know” G0 smoking status group. This misclassification could relate not only to simply whether a grandmother smoked or not, but if there is in fact a critical window during pregnancy for the effects of the smoking—for example the rapid demethylation of primordial germ cells early in pregnancy63—additional error could be introduced to the extent that a grandmother who smoked during pregnancy happened to not smoke during that critical window or a grandmother who reported not smoking, was in fact exposed during that window. It is also known that smoking is a risk factor for fetal loss.64 When this is the case, live-birth bias can lead to a reduction in the effect estimate for the association between the same exposure and a child health outcome.65,66

In conclusion, we found grandmother smoking during pregnancy associated with increased ADHD risk in the third generation. One possible mechanism underlying this association is epigenetic changes to germline cells. Given the emerging evidence of multigenerational effects in humans of in utero exposures36–43,67–72, consideration should be given to germline cells in assessing the overall toxicity of different exposures and in regulatory decision making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study II, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for their substantial contributions. Informed consent was implied through the return of the baseline questionnaire of participating women. The institutional review boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health approved the study protocol. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Source of Funding:

This work was supported by NIH grants P30 ES000002, P30 ES009089, R01HD094725, and the Escher Fund for Autism. The Nurses’ Health Study II is supported by infrastructure grant U01 176726 from the National Cancer Institute. Documentation of ADHD in the NHS-II cohort was supported by grants from Autism Speaks (Grant numbers: 1788 and 2210) and the Department of Defense (Grant number: A-14917). The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study: collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None declared

Availability of data and code for replication: Researchers interested in accessing the Nurses’ Health Study data should submit a formal proposal for collaboration. For more detailed information, please see instructions in https://nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers. The computer code used for this study is available from the authors upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thomas R, Sanders S, Doust J, Beller E, Glasziou P. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015;135(4):e994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidovitch M, Koren G, Fund N, Shrem M, Porath A. Challenges in defining the rates of ADHD diagnosis and treatment: trends over the last decade. BMC Pediatr 2017;17(1):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sciberras E, Mulraney M, Silva D, Coghill D. Prenatal Risk Factors and the Etiology of ADHD-Review of Existing Evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017;19(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.He Y, Chen J, Zhu LH, Hua LL, Ke FF. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and ADHD: Results From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J Atten Disord 2017:1087054717696766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutter M, Solantaus T. Translation gone awry: differences between commonsense and science. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23(5):247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thapar A, Rutter M. Do prenatal risk factors cause psychiatric disorder? Be wary of causal claims. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195(2):100–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knopik VS, Marceau K, Bidwell LC, et al. Smoking during pregnancy and ADHD risk: A genetically informed, multiple-rater approach. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2016;171(7):971–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu J, Lee KP, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Bhide PG. Transgenerational transmission of hyperactivity in a mouse model of ADHD. J Neurosci 2014;34(8):2768–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Zhang X, Xu Y, et al. Prenatal nicotine exposure mouse model showing hyperactivity, reduced cingulate cortex volume, reduced dopamine turnover, and responsiveness to oral methylphenidate treatment. J Neurosci 2012;32(27):9410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buck JM, Sanders KN, Wageman CR, et al. Developmental nicotine exposure precipitates multigenerational maternal transmission of nicotine preference and ADHD-like behavioral, rhythmometric, neuropharmacological, and epigenetic anomalies in adolescent mice. Neuropharmacology 2019;149:66–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustavson K, Ystrom E, Stoltenberg C, et al. Smoking in Pregnancy and Child ADHD. Pediatrics 2017;139(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, et al. Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health 2016;106(9):1573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boynton-Jarrett R, Rich-Edwards J, Fredman L, et al. Gestational weight gain and daughter’s age at menarche. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(8):1193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Milberger S. How reliable are maternal reports of their children’s psychopathology? One-year recall of psychiatric diagnoses of ADHD children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34(8):1001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuPaul GPT, Anastopoulos A, et al. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao X, Lyall K, Palacios N, Walters AS, Ascherio A. RLS in middle aged women and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in their offspring. Sleep Med 2011;12(1):89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGee G, Weisskopf MG, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Coull BA, Haneuse S. Informatively empty clusters with application to multigenerational studies. Biostatistics 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seaman SR, Pavlou M, Copas AJ. Methods for observed-cluster inference when cluster size is informative: a review and clarifications. Biometrics 2014;70(2):449–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGee G, Perkins NJ, Mumford SL, et al. Methodological Issues in Population-Based Studies of Multigenerational Associations. Am J Epidemiol 2020;189(12):1600–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wickrama KA, Conger RD, Wallace LE, Elder GH Jr. The intergenerational transmission of health-risk behaviors: adolescent lifestyles and gender moderating effects. J Health Soc Behav 1999;40(3):258–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mays D, Gilman SE, Rende R, et al. Parental smoking exposure and adolescent smoking trajectories. Pediatrics 2014;133(6):983–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira PP, Da Mata FA, Figueiredo AC, de Andrade KR, Pereira MG. Maternal Active Smoking During Pregnancy and Low Birth Weight in the Americas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19(5):497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Bhattacharya S, Raikkonen K, et al. Intergenerational Transmission of Birth Weight Across 3 Generations. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187(6):1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linnet KM, Wisborg K, Agerbo E, et al. Gestational age, birth weight, and the risk of hyperkinetic disorder. Arch Dis Child 2006;91(8):655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderweele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172(12):1339–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nevo D, Liao X, Spiegelman D. Estimation and Inference for the Mediation Proportion. Int J Biostat 2017;13(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacLehose RF, Ahern TP, Lash TL, Poole C, Greenland S. The Importance of Making Assumptions in Bias Analysis. Epidemiology 2021;32(5):617–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychol Methods 2010;15(3):234–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhodes JD, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, et al. Cigarette smoking and ADHD: An examination of prognostically relevant smoking behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Psychol Addict Behav 2016;30(5):588–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. ADHD and smoking: from genes to brain to behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1141:131–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell JT, Howard AL, Belendiuk KA, et al. Cigarette Smoking Progression Among Young Adults Diagnosed With ADHD in Childhood: A 16-year Longitudinal Study of Children With and Without ADHD. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21(5):638–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland S The effect of misclassification in the presence of covariates. Am J Epidemiol 1980;112(4):564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogburn EL, Vanderweele TJ. Bias attenuation results for nondifferentially mismeasured ordinal and coarsened confounders. Biometrika 2013;100(1):241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei Y, Schatten H, Sun QY. Environmental epigenetic inheritance through gametes and implications for human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21(2):194–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hypponen E, Smith GD, Power C. Effects of grandmothers’ smoking in pregnancy on birth weight: intergenerational cohort study. BMJ 2003;327(7420):898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rillamas-Sun E, Harlow SD, Randolph JF Jr. Grandmothers’ smoking in pregnancy and grandchildren’s birth weight: comparisons by grandmother birth cohort. Matern Child Health J 2014;18(7):1691–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golding J, Northstone K, Gregory S, Miller LL, Pembrey M. The anthropometry of children and adolescents may be influenced by the prenatal smoking habits of their grandmothers: a longitudinal cohort study. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26(6):731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller LL, Pembrey M, Davey Smith G, Northstone K, Golding J. Is the growth of the fetus of a non-smoking mother influenced by the smoking of either grandmother while pregnant? PLoS One 2014;9(2):e86781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller LL, Henderson J, Northstone K, Pembrey M, Golding J. Do grandmaternal smoking patterns influence the etiology of childhood asthma? Chest 2014;145(6):1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnus MC, Haberg SE, Karlstad O, et al. Grandmother’s smoking when pregnant with the mother and asthma in the grandchild: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Thorax 2015;70(3):237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding M, Yuan C, Gaskins AJ, et al. Smoking during pregnancy in relation to grandchild birth weight and BMI trajectories. PLoS One 2017;12(7):e0179368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golding J, Ellis G, Gregory S, et al. Grand-maternal smoking in pregnancy and grandchild’s autistic traits and diagnosed autism. Sci Rep 2017;7:46179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weisskopf MG, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Raz R. Commentary: On the Use of Imperfect Negative Control Exposures in Epidemiologic Studies. Epidemiology 2016;27(3):365–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 2010;21(3):383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laubenthal J, Zlobinskaya O, Poterlowicz K, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced transgenerational alterations in genome stability in cord blood of human F1 offspring. FASEB J 2012;26(10):3946–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nielsen CH, Larsen A, Nielsen AL. DNA methylation alterations in response to prenatal exposure of maternal cigarette smoking: A persistent epigenetic impact on health from maternal lifestyle? Arch Toxicol 2016;90(2):231–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong DA, Green BB, Blair BA, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with mitochondrial DNA methylation. Environ Epigenet 2016;2(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, et al. DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2016;98(4):680–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richmond RC, Simpkin AJ, Woodward G, et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and offspring DNA methylation across the lifecourse: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Hum Mol Genet 2015;24(8):2201–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh SP, Chand HS, Langley RJ, et al. Gestational Exposure to Sidestream (Secondhand) Cigarette Smoke Promotes Transgenerational Epigenetic Transmission of Exacerbated Allergic Asthma and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Immunol 2017;198(10):3815–3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skinner MK. Endocrine disruptors in 2015: Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016;12(2):68–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skinner MK. Endocrine disruptor induction of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014;398(1–2):4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skinner MK, Manikkam M, Guerrero-Bosagna C. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors. Reprod Toxicol 2011;31(3):337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anway MD, Skinner MK. Epigenetic programming of the germ line: effects of endocrine disruptors on the development of transgenerational disease. Reprod Biomed Online 2008;16(1):23–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anway MD, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors. Endocrinology 2006;147(6 Suppl):S43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker DM, Gore AC. Transgenerational neuroendocrine disruption of reproduction. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011;7(4):197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapoor D, Jones TH. Smoking and hormones in health and endocrine disorders. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;152(4):491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tweed JO, Hsia SH, Lutfy K, Friedman TC. The endocrine effects of nicotine and cigarette smoke. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012;23(7):334–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xin F, Susiarjo M, Bartolomei MS. Multigenerational and transgenerational effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals: A role for altered epigenetic regulation? Semin Cell Dev Biol 2015;43:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Costas J Grandmaternal Diethylstilbesterol and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172(12):1203–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roberts AL, Lyall K, Weisskopf MG. Maternal Exposure to Childhood Abuse is Associated with Mate Selection: Implications for Autism in Offspring. J Autism Dev Disord 2017;47(7):1998–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anvar Z, Chakchouk I, Demond H, et al. DNA Methylation Dynamics in the Female Germline and Maternal-Effect Mutations That Disrupt Genomic Imprinting. Genes (Basel) 2021;12(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pineles BL, Park E, Samet JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179(7):807–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leung M, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Raz R, Weisskopf MG. Bias due to Selection on Live Births in Studies of Environmental Exposures during Pregnancy: A Simulation Study. Environ Health Perspect 2021;129(4):47001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raz R, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Weisskopf MG. Live-Birth Bias and Observed Associations Between Air Pollution and Autism. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187(11):2292–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kioumourtzoglou MA, Coull BA, O’Reilly EJ, Ascherio A, Weisskopf MG. Association of Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol During Pregnancy With Multigenerational Neurodevelopmental Deficits. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172(7):670–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Titus L, Hatch EE, Drake KM, et al. Reproductive and hormone-related outcomes in women whose mothers were exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES): A report from the US National Cancer Institute DES Third Generation Study. Reprod Toxicol 2019;84:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Titus-Ernstoff L, Troisi R, Hatch EE, et al. Offspring of women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES): a preliminary report of benign and malignant pathology in the third generation. Epidemiology 2008;19(2):251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Titus-Ernstoff L, Troisi R, Hatch EE, et al. Birth defects in the sons and daughters of women who were exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Int J Androl 2010;33(2):377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Titus-Ernstoff L, Troisi R, Hatch EE, et al. Menstrual and reproductive characteristics of women whose mothers were exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Int J Epidemiol 2006;35(4):862–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bygren LO, Kaati G, Edvinsson S. Longevity determined by paternal ancestors’ nutrition during their slow growth period. Acta Biotheor 2001;49(1):53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.