Abstract

Group 3 innate lymphocytes (ILC3s) are important immune cells within mucosal tissues and protect against bacterial infections. They can be activated in response to the innate cytokines IL-23 or IL-1β, which rapidly increases their production of effector molecules that regulate barrier functions. Pathogens can subvert these anti-bacterial effects to evade mucosal defenses to infect the host. Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, produces two major toxins that can modulate the immune response. We have previously shown that lethal toxin downmodulates the function of ILC3s. On the other hand, edema toxin has been shown promote T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, adaptive counterparts of ILC3s, via elevation of cyclic AMP (cAMP). We hypothesized that edema toxin may also modulate ILC3 function. In this study, we show that edema toxin has the opposite effect of lethal toxin; edema toxin directly activates ILC3s independently of innate cytokine stimulation. Treatment of a mouse ILC3-like cell line with edema toxin, a potent adenylate cyclase, upregulated production of the cytokine IL-22, a major effector molecule of ILC3s and a critical factor in maintaining mucosal barriers. Forskolin treatment phenocopied the effect observed with edema toxin and led to an increase in CREB phosphorylation in ILC3s. This observation has potential implications for a role for cAMP signaling in the activation of ILC3s.

Keywords: IL-22, innate lymphocyte, cAMP signaling, CREB, bacterial toxins, anthrax

Introduction

Innate lymphocytes (ILCs) are a heterogenous family of lymphocytes that share several phenotypes and functions with CD4 T cells but unlike their T cell counterparts, lack antigen-specific receptors [1, 2]. ILCs are classified into three groups based on the expression of lineage-specific transcription factors, surface markers, and secretion of cytokines [3]. Group 3 ILCs (ILC3s) are defined by the transcription factor RORγt and activated by environmental signals, including innate cytokines such as IL-23 or IL-1β. Upon activation ILC3s produce cytokines such as IL-22, GM-CSF and IL-17 [4], similar to their adaptive counterparts, T helper 17 (Th17) cells. IL-22 is an important modulator of tissues responses during infection and inflammation by helping to maintain the epithelial barrier by preventing cell death, stimulating proliferation of epithelial stem cells and by inducing protective factors such as mucins and antimicrobial proteins [5]. ILC3s are rare, but enriched in mucosal barriers, especially the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. They are critical in regulating epithelial and mucosal barriers and therefore contribute to protection against invasion by bacterial pathogens [1, 4]. ILC3 activation is an active area of research interest not only for combatting respiratory and gastrointestinal pathogens, but also for their pathogenic role in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Toxins produced by pathogenic bacteria modulate host cell functions during infection, but have also served biologists as important tools for probing eukaryotic cell signaling pathways [6]. Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, produces two major toxins, lethal toxin (LT) and edema toxin (ET), which share a common receptor binding subunit, protective antigen (PA). PA assembles with the enzymatic subunits, lethal factor (LF) or edema factor (EF), to translocate LF or EF into the host cytosol [7]. LF is a zinc metalloprotease that cleaves mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKKs) while EF is a calmodulin and calcium dependent adenylate cyclase with 1,000-fold higher activity than mammalian adenylate cyclase in generating the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [8, 9].

Both LT and ET exert immunosuppressive activity on innate and adaptive immune cells [10–12]. We have previously shown that B. anthracis LT downregulates ILC3 function by inhibiting mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling [12]. Treatment of mouse or human primary ILC3s or a mouse ILC3-like cell line with LT prevented IL-23-mediated production of IL-22 [12]. In contrast to LT, ET, at subtoxic concentrations, has been shown to promote Th2 and Th17 differentiation via elevation of cAMP levels [13, 14]. Similar to this, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) promotes Th2 cytokine production and Th17 differentiation by inducing cAMP accumulation highlighting the role of cAMP signaling in modulation of T cell function [15–17]. More recently, PGE2 has been shown to induce IL-22 production in T cells via cAMP signaling [18]. Given the Th17 promoting activity of ET, we hypothesized ET modulates ILC3 function by activating cAMP signaling. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of ET on ILC3s. We found that ET induced IL-22 production and that another cAMP elevating agent, forskolin, also activated ILC3s. Our observation has potential implications for a role of cAMP signaling in ILC3 activation.

Materials and Methods

Cell line

MNK-3 cells clone B3, derived from single cell cloning of the ILC3-like mouse cell line MNK-3 cells [19], was maintained in DMEM (Corning; Tewksbury, MA, USA) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gemini Bio-Products; West Sacramento, CA), 2 mM GlutaMax (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GE Healthcare HyClone; Logan, UT, USA), 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma; St. Louis, MO, USA), 10 mM HEPES (Corning), 50 μg/ml gentamycin (Amresco; Solon, OH, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin (Gemini Bio-Products), 100 U/ml streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products) and 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-7 (Peprotech; Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). An equal number of cells were used in all wells within an experiment.

Bacterial toxin and forskolin

Recombinant protective antigen and edema factor were obtained from List Biologicals (Campbell, CA, USA) and Biodefense and Emerging Infections (BEI) Research Resources Repository (Manassas, VA, USA). Forskolin was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA).

Real time RT-PCR

Cells were harvested in TriPure (Roche; Nutley, NJ, USA) and RNA was prepared according to the manufacturers’ protocols. RNA was DNase (Roche) treated and cDNA was reverse transcribed using EasyScript Plus (Lamda Biotech; St. Louis, MO, USA) with oligo dT as the primer. cDNA was used as template in a real time PCR reaction using primer-probes sets on an QuantStudio5 real time PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA). Primer-probe sets were: Il22 (Mm00444241_m1; Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT); Coralville, IA, USA), Csf2 (Mm01290062_m1; IDT, Il17a Mm01290062_m1; IDT, Il17f (Mm00521423_m1; Thermo Fisher Scientific), Tnf (Mm00443260_g1; IDT)) and Hprt (Mm01545399_m1; IDT). cDNA was semi-quantitated using the ΔCT method with Hprt as an internal control for all samples.

ELISA

Mouse IL-22 ELISA (Antigenix America; Huntington Station, NY, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described [12]. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology [CST]; Danvers, MA, USA). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4–15% gradient gel (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) followed by transfer to an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore; Billerica, MA, USA) using a wet transfer method. The protein-transferred membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with the manufacturer’s recommended concentration of primary antibody overnight with rocking at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were: CREB (9197; CST), Phospho-CREB (9198; CST), Actin (3700; CST). Blots were then washed and incubated with the appropriate species-specific-HRP secondary antibody (1:1000) for 1 hr. Blots were developed using Pierce ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using a FluorChem Q imager (Alpha Innotech; San Leandro, CA, USA). For reblotting with another antibody, blots were stripped using a Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), then washed and re-blocked and used as indicated above.

Intracellular cytokine staining

MNK-3 cells were treated with toxin or forskolin for 2 hours. After 2 hours, brefeldin A (BFA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the cells and incubated for another 4 hours. MNK-3 cells were intracellularly stained with an anti-IL-22 Ab (clone IL22JOP, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, analyzed by flow cytometry on a Stratedigm S1200Ex flow cytometer (Stratedigm, San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo v.10.6 (Becton Dickinson; Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were performed at least three independent times. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0.2 (San Diego, CA, USA). Values are expressed as mean±SD. For two-way comparisons, a standard unpaired t-test was used. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA was used with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance was defined as a value of p≤0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), p<0.0001 (****). Differences that were not significant (p>0.05) are marked as ns.

Results and Discussion

Given the previous observation that ET promotes development of Th17 cells [13], adaptive immune cell counterparts of ILC3s, we hypothesized that ET activates ILC3s. To test this hypothesis, we treated MNK-3 cells, a mouse ILC3-like cell line that is well-characterized to be transcriptionally similar to primary ILC3s [19], with ET and measured mRNA levels of Il22 and other cytokine encoding genes expressed by ILC3s. We found that ET upregulated Il22 as well as Il17a and Il17f (Figure 1A). ET had no effect on Tnf levels. Csf2, which encodes GM-CSF, was decreased by ET. Treatment with EF or PA alone did not induce these effects indicating that internalization of EF was required for modulation of cytokine expression. We also observed an increase in secreted IL-22 in the supernatants of ET treated cells consistent with the increase in Il22 mRNA (Figure 1B). Thus, ET treatment of ILC3s leads cell activation as measured by production of IL-22 and other cytokines.

Figure 1. Edema toxin induces IL-22 production in ILC3s.

(A) MNK-3 cells were treated with protective antigen (PA 50 ng/ml), edema factor (EF 50 ng/ml), and edema toxin (PA 50 ng/ml+EF 50 ng/ml). Untreated MNK-3 cells were included as control. RNA was extracted after 5 hours and cDNA was synthesized. Il22, Csf2, Il17a, Il17f, and Tnf mRNA levels were measured by real time RT-PCR.

(B) MNK-3 cells were treated with EF (50 ng/ml) or ET (PA 50 ng/ml+EF 50 ng/ml) for 18 hours and IL-22 secreted in the supernatant was measured by ELISA.

Data shown are the mean±SD from one experiment of at least three experiments. p<0.01 (**), p<0.001 (***), p<0.0001 (****), p>0.05, not significant (ns).

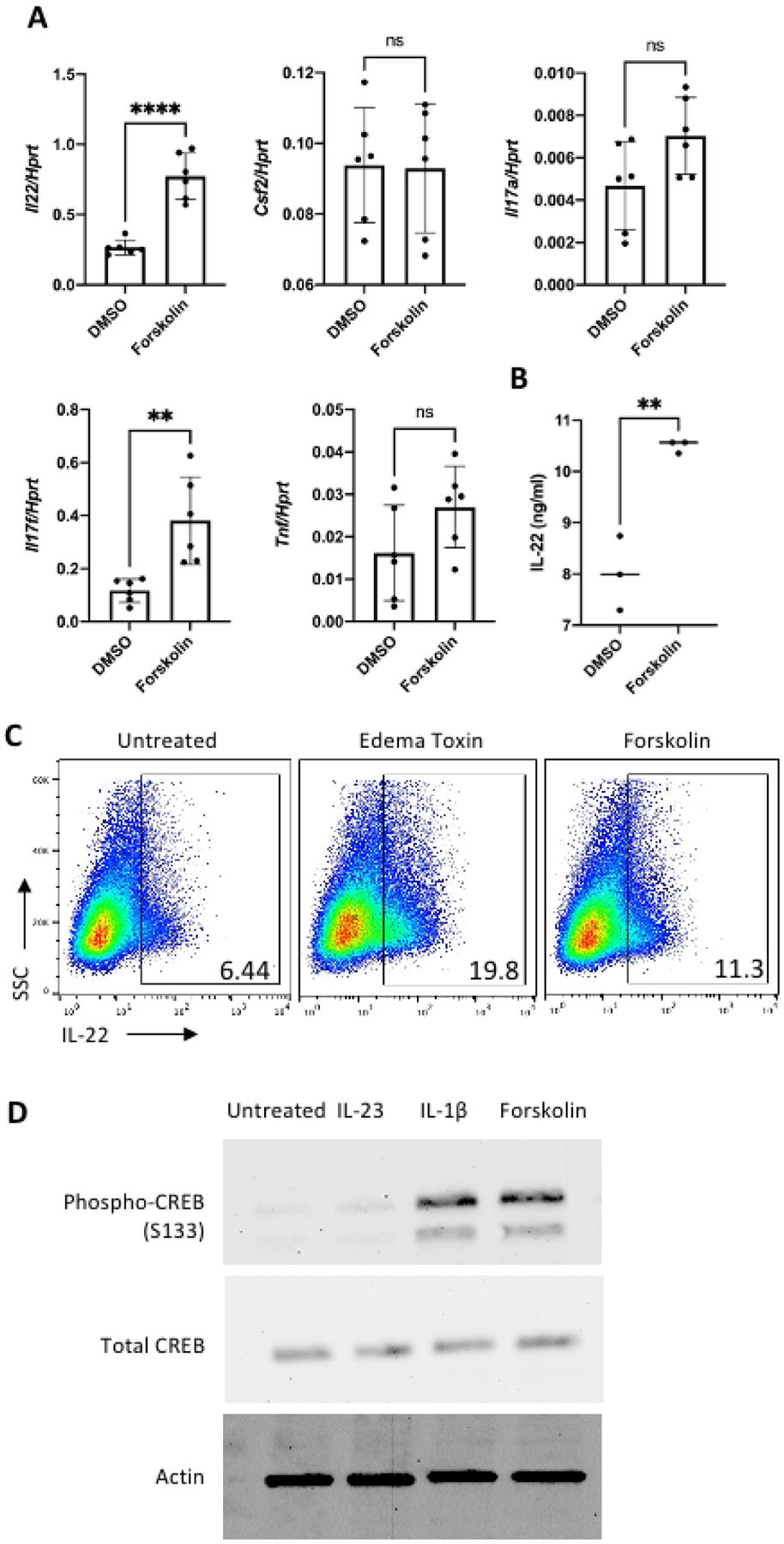

ET is a potent adenylate cyclase and results in accumulation of cAMP in the cells. This raises the question if modulation of cytokine expression by ET is due to cAMP accumulation. To address this, we used forskolin, a known inducer of mammalian adenylate cyclase [20], to treat MNK-3 cells and measured Il22 and other cytokine encoding genes expressed by ILC3s. Like ET, forskolin upregulated Il22 and Il17f levels (Figure 2A). Forskolin had no detectable effect on levels of Csf2, Il17a and Tnf. We observed an increase in secreted IL-22 and percentage of IL-22-producing cells in forskolin-treated cells compared to DMSO control as measured by ELISA and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS), respectively (Figure 2B and C). This suggests that ET and forskolin have shared, but also distinct due to differences in Csf2, mechanisms for ILC3 activation.

Figure 2. Forskolin induces IL-22 production in ILC3s.

(A) MNK-3 cells were treated with forskolin (10 μM) or as a control, DMSO, for 5 hours. RNA was extracted and cDNA was synthesized. Il22, Csf2, Il17a, Il17f, and Tnf mRNA levels were measured by real time RT-PCR.

(B) MNK-3 cells were treated with forskolin (10 μM) or a control, DMSO, for 18 hours. Supernatant from the cells were used to measure IL-22 by ELISA.

(C) MNK-3 cells were treated with ET (PA 50 ng/ml+EF 50 ng/ml) or forskolin for 2 hours followed by addition of brefeldin A (BFA) and incubated for another 4 hours. Cells were subjected to intracellular cytokine staining for IL-22 followed by FACS analysis. Shown are representative FACS plots. Number within gate represents the percentage of IL-22+ cells.

(D) MNK-3 cells were stimulated with IL-23 (50 ng/ml), IL-1β (20 ng/ml) or forskolin (10 μM) for 20 mins and cell lysate was collected. Phosphorylated CREB (S133), total CREB and actin were assessed by western blotting.

Data shown are the mean±SD from one experiment of at least three experiments. p<0.01 (**), p<0.0001 (****), p>0.05 not significant (ns).

In cells, the accumulation of cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) which phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB to regulate gene expression [21]. Therefore, we measured CREB phosphorylation during activation by forskolin and other ILC3-activating cytokines and found an increase in phosphorylated CREB (S133) during activation by forskolin or IL-1β but not IL-23 (Figure 2D).

Bacterial adenylate cyclase toxins such ET and CyaA, produced by B. anthracis and Bordetella pertussis, respectively, are known to promote Th2 and Th17 cell differentiation [13, 14]. The ability of these toxins to promote immune responses is also evidenced by their adjuvanticity [22–24]. Here we show that ET and forskolin induced IL-22 in MNK-3 cells suggesting elevation of cAMP levels can lead to activation of ILC3s. We also noted that the increase in Il22 and IL-22 expression (both mRNA and protein) was more pronounced with ET treatment than forskolin. ET is likely to elevate cAMP levels more than forskolin as it has 1,000-fold more activity than mammalian adenylate cyclases targeted by forskolin [8]. Consistent with this, PGE2 has been shown to act directly on ILC3s and enhance IL-22 production by activating cAMP signaling [25]. Moreover, PGE2 promotes Th17 differentiation and also induces IL-22 production in T cells via cAMP signaling [15, 18]. It is likely that cAMP signaling is a shared mechanism in modulating function of ILC3 and helper T cells. Classically, the effects of cAMP are mediated by activation of PKA/CREB signaling [21]. We observed an increase in CREB phosphorylation in MNK-3 cells during forskolin and IL-1β activation. Consistent with this, Duffin et al. reported an increase in CREB phosphorylation that accompanied IL-22 production in ILC3s treated with PGE2 suggesting a role for cAMP/PKA/CREB signaling in ILC3 activation [25]. A promoter analysis for transcription factor binding sites revealed several putative conserved CREB binding sites in the human and mouse IL22 and Il22 promoters (data not shown).

Our finding also has implications on the biology of anthrax infection and other respiratory and GI infectious diseases. We have previously shown that LT inhibits ILC3 activation [12] and now find that the other major toxin ET directly activates ILC3s. This is unusual as pathogens are usually implicated in downmodulating, not activating, host immune responses for evasion [26]. In a cutaneous infection model, LF was found to be produced in high amounts, with EF levels increasing during infection [27]. These toxins are readily found in the bloodstream and likely rapidly disseminate to many tissues, where they encounter ILC3s and may exert long distance effects. Infection is a complex process, but these data suggest that high levels of LT may limit ET activation of ILC3s in vivo. Future work will investigate the complex interactions of LT, ET and ILC3s in mucosal tissues.

ILC3 biology is important in understanding immune responses at mucosal barriers. Elucidating the cellular signaling pathways that activate and inhibit ILC3 functions is critical for being able to control ILC3s at sites of infection and inflammation. Our findings implicate a role of cAMP signaling in IL-22 production by ILC3s which could be targeted by existing and already in development therapeutics.

Highlights.

Bacillus anthracis edema toxin (ET), a potent adenylate cyclase, induces IL-22 in MNK-3 cells, a mouse ILC3-like cell line.

Forskolin, another cAMP elevating agent, also induces IL-22 in MNK-3 cells.

Forskolin and IL-1β induce CREB phosphorylation in MNK-3 cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Laboratory for Molecular Biology and Cytometry Research at OUHSC for the use of the Flow Cytometry and Imaging facility. We thank Biodefense and Emerging Infections (BEI) Resources for providing protective antigen and edema factor. We thank Drs. David S.J. Allan and James R. Carlyle for providing the MNK-3 cell line. This project was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM103447 and P20GM134973), a pilot award to LAZ (as part of U19AI062629), the Presbyterian Health Foundation and the Stephenson Cancer Center (SCC). Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520 awarded to the SSC and used the Molecular Biology Shared Resource.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Eberl G, Colonna M, Di Santo JP, McKenzie AN, Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology, Science 348(6237) (2015) aaa6566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Panda SK, Colonna M, Innate Lymphoid Cells in Mucosal Immunity, Front Immunol 10 (2019) 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vivier E, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie ANJ, Mebius RE, Powrie F, Spits H, Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On, Cell 174(5) (2018) 1054–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klose CSN, Artis D, Innate lymphoid cells control signaling circuits to regulate tissue-specific immunity, Cell Res 30(6) (2020) 475–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Keir M, Yi Y, Lu T, Ghilardi N, The role of IL-22 in intestinal health and disease, J Exp Med 217(3) (2020) e20192195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schiavo G, van der Goot FG, The bacterial toxin toolkit, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2(7) (2001) 530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moayeri M, Leppla SH, Vrentas C, Pomerantsev AP, Liu S, Anthrax Pathogenesis, Annu Rev Microbiol 69 (2015) 185–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Leppla SH, Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79(10) (1982) 3162–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Friebe S, van der Goot FG, Burgi J, The Ins and Outs of Anthrax Toxin, Toxins (Basel) 8(3) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gottle M, Dove S, Seifert R, Bacillus anthracis edema factor substrate specificity: evidence for new modes of action, Toxins (Basel) 4(7) (2012) 505–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Paccani SR, Baldari CT, T cell targeting by anthrax toxins: two faces of the same coin, Toxins (Basel) 3(6) (2011) 660–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Seshadri S, Allan DSJ, Carlyle JR, Zenewicz LA, Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin negatively modulates ILC3 function through perturbation of IL-23-mediated MAPK signaling, PLoS Pathog 13(10) (2017) e1006690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Paccani SR, Benagiano M, Savino MT, Finetti F, Tonello F, D’Elios MM, Baldari CT, The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bacillus anthracis is a potent promoter of T(H)17 cell development, J Allergy Clin Immunol 127(6) (2011) 1635–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rossi Paccani S, Benagiano M, Capitani N, Zornetta I, Ladant D, Montecucco C, D’Elios MM, Baldari CT, The adenylate cyclase toxins of Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis promote Th2 cell development by shaping T cell antigen receptor signaling, PLoS Pathog 5(3) (2009) e1000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Boniface K, Bak-Jensen KS, Li Y, Blumenschein WM, McGeachy MJ, McClanahan TK, McKenzie BS, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ, de Waal Malefyt R, Prostaglandin E2 regulates Th17 cell differentiation and function through cyclic AMP and EP2/EP4 receptor signaling, J Exp Med 206(3) (2009) 535–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gold KN, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ, Modulation of helper T cell function by prostaglandins, Arthritis Rheum 37(6) (1994) 925–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kalinski P, Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2, J Immunol 188(1) (2012) 21–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Robb CT, McSorley HJ, Lee J, Aoki T, Yu C, Crittenden S, Astier A, Felton JM, Parkinson N, Ayele A, Breyer RM, Anderton SM, Narumiya S, Rossi AG, Howie SE, Guttman-Yassky E, Weller RB, Yao C, Prostaglandin E2 stimulates adaptive IL-22 production and promotes allergic contact dermatitis, J Allergy Clin Immunol 141(1) (2018) 152–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Allan DS, Kirkham CL, Aguilar OA, Qu LC, Chen P, Fine JH, Serra P, Awong G, Gommerman JL, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Carlyle JR, An in vitro model of innate lymphoid cell function and differentiation, Mucosal Immunol 8(2) (2015) 340–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Seamon KB, Daly JW, Forskolin: a unique diterpene activator of cyclic AMP-generating systems, J Cyclic Nucleotide Res 7(4) (1981) 201–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sassone-Corsi P, The cyclic AMP pathway, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4(12) (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Duverger A, Jackson RJ, van Ginkel FW, Fischer R, Tafaro A, Leppla SH, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H, McGhee JR, Boyaka PN, Bacillus anthracis edema toxin acts as an adjuvant for mucosal immune responses to nasally administered vaccine antigens, J Immunol 176(3) (2006) 1776–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hormozi K, Parton R, Coote J, Adjuvant and protective properties of native and recombinant Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin preparations in mice, FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 23(4) (1999) 273–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Quesnel-Hellmann A, Cleret A, Vidal DR, Tournier JN, Evidence for adjuvanticity of anthrax edema toxin, Vaccine 24(6) (2006) 699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Duffin R, O’Connor RA, Crittenden S, Forster T, Yu C, Zheng X, Smyth D, Robb CT, Rossi F, Skouras C, Tang S, Richards J, Pellicoro A, Weller RB, Breyer RM, Mole DJ, Iredale JP, Anderton SM, Narumiya S, Maizels RM, Ghazal P, Howie SE, Rossi AG, Yao C, Prostaglandin E(2) constrains systemic inflammation through an innate lymphoid cell-IL-22 axis, Science 351(6279) (2016) 1333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Van Avondt K, van Sorge NM, Meyaard L, Bacterial immune evasion through manipulation of host inhibitory immune signaling, PLoS Pathog 11(3) (2015) e1004644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rougeaux C, Becher F, Ezan E, Tournier JN, Goossens PL, In vivo dynamics of active edema and lethal factors during anthrax, Sci Rep 6 (2016) 23346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]