Abstract

Introduction:

As highly sophisticated intercellular communication vehicles in biological systems, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been investigated as both promising liquid biopsy-based disease biomarkers and drug delivery carriers. Despite tremendous progress in understanding their biological and physiological functions, mechanical characterization of these nanoscale entities remains challenging due to the limited availability of proper techniques. Especially, whether damage to parental cells can be reflected by the mechanical properties of their EVs remains unknown.

Methods:

In this study, we characterized membrane viscosities of different types of EVs collected from primary human trophoblasts (PHTs), including apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and small extracellular vesicles, using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). The biochemical origin of EV membrane viscosity was examined by analyzing their phospholipid composition, using mass spectrometry.

Results:

We found that different EV types derived from the same cell type exhibit different membrane viscosities. The measured membrane viscosity values are well supported by the lipidomic analysis of the phospholipid compositions. We further demonstrate that the membrane viscosity of microvesicles can faithfully reveal hypoxic injury of the human trophoblasts. More specifically, the membrane of PHT microvesicles released under hypoxic condition is less viscous than its counterpart under standard culture condition, which is supported by the reduction in the phosphatidylethanolamine-to-phosphatidylcholine ratio in PHT microvesicles.

Discussion:

Our study suggests that biophysical properties of released trophoblastic microvesicles can reflect cell health. Characterizing EV’s membrane viscosity may pave the way for the development of new EV-based clinical applications.

Keywords: extracellular vesicle, membrane viscosity, fluorescence lifetime, placental trophoblast, hypoxia

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

As the maternal-fetal interface, the placenta is responsible for the maternal-fetal exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste products, and the production of pregnancy hormones and fetal immunological defense. It is therefore essential for fetal growth and development. Currently, the assessment of placental health during pregnancy commonly balances accuracy and invasiveness. The evaluations of placental health by biophysical parameters (e.g., volume, shape, blood flow) or by plasma proteins assays (e.g., sFlt, PlGF, PAPP-A, endoglin, and PP-13) can suggest the likelihood of disease in certain clinical contexts, but are limited in their ability to inform placental health [1-7]. On the other hand, although placental needle biopsy provides more accurate diagnosis [8,9], its invasiveness makes it unlikely to be useful as a dynamic gauge of placental fitness throughout pregnancy. Considering that a trophoblast layer surrounds the placental villi and is in direct contact with the maternal blood within the intervillous space, any maternal pathological condition, such as hypoxia or bacterial/viral infection, is expected to engage the trophoblasts before further propagating into the placenta to affect the fetus. Thus, assessing trophoblast health may provide new tools for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of placental disorders.

Recent studies have shown that trophoblasts constantly release diverse types of extracellular vesicles (EVs), including apoptotic bodies (ABs), microvesicles (MVs) and small EVs (sEVs, exosomes) [10]. Although all are packaged as lipid vesicles, EV subtypes differ in size, cargo, mechanism of formation and impact on target cells [11]. Specifically, ABs range in size from 800 nm to 5 μm and are produced from cells undergoing apoptosis. The size of MVs ranges between 100 nm and 1 μm and are generated by budding off from the plasma membrane. The even smaller sEVs (30 nm – 150 nm) are formed by an endosomal route and released to the extracellular environment after multivesicular bodies fuse with plasma membrane. Our previous study showed that, among released trophoblastic EVs, the level of MVs is several folds higher than the level of sEVs [12]. Similar results were found in placental perfusates, where most of the released EVs are from trophoblasts [13] or from placental explants [14,15]. Interestingly, trophoblast hypoxia is implicated in the gestational disorder preeclampsia, and the level of circulating EVs (MVs and sEVs) is higher in this condition [14,16-18]. However, whether damage to trophoblasts by intrauterine hypoxia can be reflected by their EVs remains unknown.

The last decade has witnessed tremendous progress in our understanding of EV functions in mediating intercellular communication, especially in the context of disease initiation and progression [19,20]. Facilitated by the rich biological information about their cellular origin carried by their cargo, EVs have emerged as novel liquid biopsy-based biomarkers for diagnostics and prognosis [21-23]. In addition to their biological signatures, identifying their mechano-physical signatures may further enhance the application of EVs to diagnostics [24,25]. In particular, changes in cell membrane viscosity have been identified in various disease types, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy [26], ischemic heart disease [27], Gaucher disease [28] and cancer [29,30]. Cell membrane viscosity is primarily dictated by its lipid composition, which is closely regulated by cellular lipid metabolism. Altered lipid homeostasis is expected to affect not only the plasma membrane but also intracellular membranes. Therefore, membrane viscosity of EVs, particularly the membrane viscosity of ABs and MVs, may inform disease state and prognosis, and thus serve as a new marker in liquid biopsy tests.

In this work, we have collected EVs from primary human trophoblasts (PHTs) medium, cultured under standard or hypoxic conditions, and quantitatively characterized their membrane viscosity using a lipophilic carbocyanine dye, 3,3’-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiO), by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). In contrast to fluorescence microscopy which generates images based on the fluorescence intensity of fluorophores, FLIM generates images based on their fluorescence lifetime which is the time that fluorophores stay in the excited state before they return to the ground state by emitting a photon. The fundamentals, instrumentation and applications of FLIM have been summarized elsewhere [31,32]. The fluorescence lifetime of carbocyanine dyes is sensitive to the viscosity of their local environment, which have allowed them to be considered as molecular rotors and used for the characterization of lipid packing and membrane tension [33-36]. Our results show that different EV types derived from the same cell type exhibit different membrane viscosities due to their distinctive lipid compositions. Hypoxic condition leads to changes in the lipid composition and consequently in the membrane viscosity. Our study suggests a causal correlation between the in vitro condition of PHT cells that mimics pathological conditions in vivo and the changes to the biochemical and mechanical properties of PHT-derived EVs, which may promote the development of EV-based assay for assessment of placental health.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and conditioned medium collection

Mouse myoblast C2C12 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). PHT cells were isolated from placentas of uncomplicated pregnancy, labor, and delivery according to our previously published protocol [37] with the approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. All cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere with 95% humidity. C2C12 cells were allowed to grow to 80% confluence in 150 mm-diameter petri dishes before replacing the old medium with culture medium supplemented with 10% bovine EV-depleted FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). PHT cells, which do not divide in culture, were maintained near confluency under either standard or hypoxic condition for 72 h. The standard culture condition (5% CO2 and ambient 20% O2) was maintained in a standard cell culture incubator, while the hypoxic condition was maintained in a hermetically enclosed incubator (Thermo Electron, Marietta, OH) that provided a hypoxic atmosphere, defined as <1% O2 (5% CO2, 10% H2, and 85% N2) [38]. For the hypoxia experiments, PHT cells were cultured under standard condition for 4 h to allow cell attachment before being transferred to the hypoxic condition for prolonged culture. The atmospheric O2 level was continuously monitored using a sensor connected to a data acquisition module (Scope; Data Translation, Marlboro, MA, USA). After 72 h, conditioned medium was collected for EV isolation.

Isolation and characterization of EVs

EVs were isolated from conditioned medium by following our previously published protocol [12]. Briefly, ABs were pelleted by centrifugation at 2,500g at 4°C for 20 min from the supernatant after removing cell debris at 500g for 3 min, and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 12,000g at 4°C for 30 min to obtain MV pellets. Both ABs and MVs were washed with PBS for three times prior to usage. The supernatant was then filtered using a 0.22 μm filter, and concentrated by a Vivacell 100 filtration unit (100 kDa MW cut-off, Sartorius, New York, NY). The concentrated medium was diluted in 15 ml PBS and ultracentrifuged at 100,000g overnight to pellet the sEVs. Crude sEVs were loaded at the bottom of 6%-40% continuous OptiPrep gradient and further purified by centrifugation at 100,000 x g at 4°C overnight. Fractions containing sEVs were pooled together and underwent the repeated PBS dilution step and centrifuge-based concentration procedure to eliminate OptiPrep in the final purified sEVs. ABs and MVs were directly visualized under an optical microscope with a X63 objective. The size of sEVs was characterized using a nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) system. Western blotting was performed to confirm the presence of characteristic sEV biomarkers [12,39]. For western blotting analyses, 5 μg sEVs were lysed in a cell lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100, supplemented with protease inhibitors (mini cOmplete Ultra tablets, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail tablets (PhosSTOP, Roche). Lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes as we previously described [40]. Membranes were immunoblotted with various primary antibodies: mouse anti-TSG101 (ab83, final concentration 0.1 μg/ml Abcam, Cambridge, MA), mouse anti-CD63 (sc-5275, final concentration 0.2 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), mouse anti-Syntenin-1 (sc-100336, final concentration 0.1 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Each was followed by appropriate horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody. Signals were visualized using SuperSignal West Dura (Thermo Fisher).

Staining of cells and EVs with DiO

C2C12 cells were stained with a working dye concentration of 5 μM at 37°C for 10 min, and then thoroughly rinsed with pre-warmed PBS for three times to remove any possible free dye. Although fluorescence lifetime is largely independent on the dye concentration, special attention was paid to minimize any structural distortion to EVs and the formation of dye aggregates. All EVs were stained overnight with a dye concentration of 50 nM at 4°C to minimize the disturbance to EV structure and the formation of dye aggregates. Significant structural distortion to EVs was observed at higher dye concentrations, as manifested by the emergence of lipid-dye aggregates with irregular morphologies (Supplementary Figure 1). Free dye was removed by spinning down stained EVs (2500 g for 20 min for ABs, 12000 g for 30 min for MVs, and 100000 g overnight in opti-prep density gradient, follow by 100 kD molecular size ultrafiltration for sEVs) and re-suspending the pellets in particle free-PBS.

Viscosity measurement of glycerol/methanol mixtures

Glycerol and methanol were mixed together thoroughly with a volume-to-volume ratio ranging from 10:90 to 85:15. The viscosity of glycerol/methanol mixtures was measured using a Brookfield DV-II+ viscometer (Brookfield, Middleboro, MA) with a CP-42 spindle at room temperature (23°C). For each volume ratio, 1 mL mixture solution is used. Measurements were performed at several different shear rates and the mixtures were confirmed to behave as a Newtonian fluid.

Surface functionalization of glass surface

To facilitate the immobilization of EVs, glass coverslips were chemically functionalized to render a layer of aldehyde groups. Specifically, glass coverslips were plasma-treated for 1 min at a high power level (18 W) using a plasma cleaner (Harrick Plasma, Ithaca, NY), followed by sequential incubations in 4% 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS; Sigma-Aldrich) in isopropanol for 30 min and then 1% glutaraldehyde solution (Alfa Aesar) for 30 min.

Artificial vesicle synthesis and size characterization

Artificial vesicles were synthesized using the lipid hydration method, followed by size control using an extruder set (Avanti Polar Lipids). Lipid mixture solutions were prepared at a total lipid concentration of 0.5 mg/mL in chloroform with 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (SOPC; Avanti Polar Lipids) and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(cap biotinyl) (Biotin-cap-PE; Avanti Polar Lipids) at a molar ratio of 0.95/0.05, and DiO at a concentration of 10 nM. The purpose of incorporating 5% biotin-cap-PE lipids was to facilitate vesicle immobilization on glass substrates via biotin-neutravidin binding for FLIM experiments. Lipid solutions were thoroughly mixed, gently dried under argon flow for 10 min and vacuum dried for 1 hour. The dried lipid films were rehydrated with PBS and maintained at 65° for 1 h. During this incubation, the lipid solution was vortexed for 15 sec every 5 min. The vesicle solutions were then extruded through porous polycarbonate membranes with a pore diameter of either 100 nm or 1 μm (Avanti Polar Lipids) back and forth for 21 times. After extrusion, the size distribution of obtained vesicles was characterized using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) particle size analyzer (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS).

FLIM measurement and data analysis

Fluorescence lifetime measurements were performed using a multiphoton FLIM system. The system setup was previously published [41]. The multiphoton laser was tuned to 860 nm to optimize the excitation level of DiO, and the photomultiplier tube was tuned to 475-650 nm to detect the full range of DiO emission. Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) was implemented using a Becker & Hickl SPC-830 acquisition package. Each measurement collected photons with a pixel resolution of 256 x 256 and a scan rate of 400 Hz with a 100x oil-immersion objective for 900 s. Fluorescence lifetime analysis was performed using SPCImage (Becker & Hickl). Thresholding treatment, designed to exclude photons emitted from regions not occupied by cells, was performed in Matlab based on the photon numbers. For EVs, lifetime images were binned with a binning factor of 10 to maximize the peak photon count, and fitted with a two-exponential decay function. Average fluorescence lifetime over the entire field of view was obtained. Reported lifetime values were average values and standard deviations of multiple fields of view from at least three independent experiments. Detailed description about the exponential decay model is available elsewhere [41].

Mass spectrometry for phospholipid analysis

Lipidomics analysis was conducted using a Vanquish UHPLC coupled to an ID-X tribrid high resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) after samples were Folch extracted and dried under N2. Before injection (2 μL) onto an Accucore C18 column (2.1 X 100 mm, 5 μ pore size), samples were reconstituted in 100 μL of ACN:IPA (1:1). The gradient consisted of solvent A (H2O:ACN (2:3) with 10 mM ammonium formate + 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (IPA:ACN (9:1) with 10 mM ammonium formate + 0.1% formic acid) and the flow rate was set to 0.26 mL/min at a column temperature of 50°C. The gradient started at 30%B and increased to 55%B at 2.1 min followed by an increase to 65%B at 12 min and another increase to 85%B at 18 min. The gradient increased to 100%B at 20 min and was held for 5 min before a decrease to 40%B and return to equilibration. The total run time was 28 min. Samples were run in both positive and negative ion mode and were analyzed using full scan accurate mass at a resolution of 70K and 35K for ddMS2 with stepped collision energy. Raw data files were processed using LipidSearch (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and manually curated to remove identifications without MS2 fatty acid side chain information and to only include the predominant lipid ion species. The individual lipid ion peak areas were summed for each type of PL so that comparison can be made among different EV types or different culture conditions.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation where relevant. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test or ANOVA followed with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Different types of PHT EVs have distinctive phospholipid compositions

We isolated ABs, MVs and sEVs from PHT conditioned medium by a well-characterized density gradient ultracentrifugation procedure [12]. The degree of apoptosis of the parental cells has been extensively characterized in our previous publications [42-44]. EVs were fluorescently labeled using the lipophilic DiO. We then allowed them to be adsorbed onto glass coverslips for further characterizations. To enable the immobilization of EVs, we chemically functionalized glass coverslips to make the surface reactive to the primary amine groups on the EV surface proteins (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Figure 1A, we were able to directly visualize MVs and ABs using an optical microscope with an ×63 objective. As expected, ABs exhibited a wide range of sizes (3.74 ± 1.62 μm in diameter) and were significantly larger than MVs. Because the size of sEVs and small MVs are below the resolution limit of regular optical microscopy, we characterized their size using a nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) system. As shown in Figure 1B, the diameter of PHT cell-derived sEVs showed a narrow distribution around 100 nm and MVs are larger, which is consistent with previously reported values [11,12]. Using western immunoblotting, the presence of characteristic sEV biomarkers, including syntenin-1, TSG-101 and CD63, in the purified sEVs has been confirmed in our previous study [12].

Figure 1. Biophysical characterization of trophoblastic EVs.

(A) Representative differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images of PHT cell-derived ABs and MVs. Scale bars: 10 μm. (B) Representative size distributions of PHT-derived MVs and sEVs measured by NTA. (C) The relative fraction of major phospholipids in AB, MV and sEV derived from PHT cells, including phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidic acid (PA), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) species. Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviation and * denotes p < 0.05 with n = 3 for each group representing number of experimental repeats.

We examined the lipid compositions of the EVs derived from PHT cells using mass spectrometry. As shown in Figure 1C, different types of EVs have distinctive phospholipid compositions. Although ABs were abundant in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), the abundance of several other different types of phospholipids, including phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidic acid (PA), was found at a similar level and not negligible. In contrast, the phospholipid components of MVs and sEVs were dominated by PE or PC, respectively. Such differences in lipid composition among different EV subtypes derived from the same cellular origin have also been identified in several other cell types and are believed to be due to their distinctive biogenesis pathways [45]. PE, because of its small polar headgroup, tends to create a more viscous membrane than PC [46]. Considering the significant difference in the abundance of PE and PC lipids, it was expected that the PHT-derived MVs would feature a much more viscous membrane than that of sEVs.

Quantification of the membrane viscosity of EVs

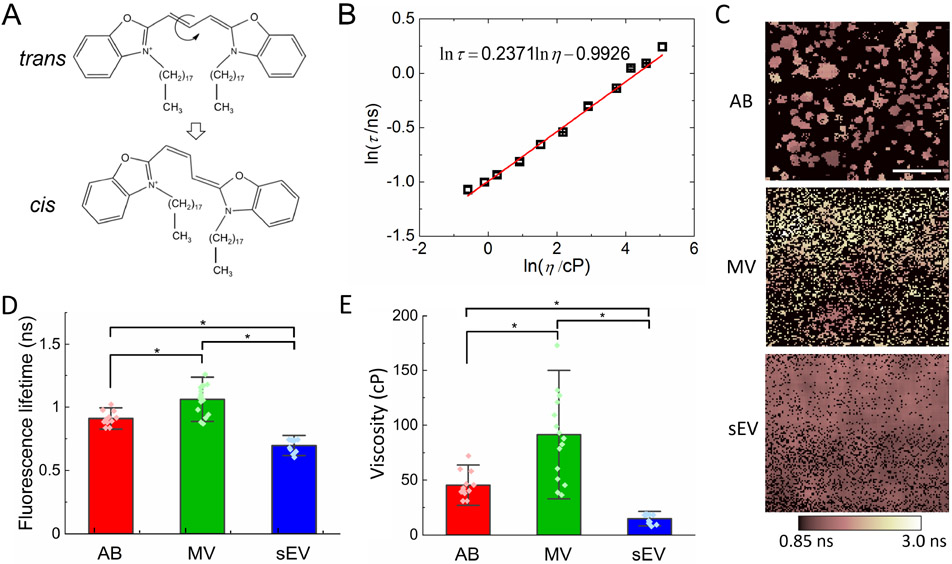

We probed the membrane viscosity of our EVs by characterizing the fluorescence lifetime of the DiO molecules embedded in the lipid bilayer using FLIM. DiO molecules preferentially stay in the trans conformation in the ground state (Figure 2A). After excitation by incident light, the molecule can return to the ground state by either emitting a photon (i.e. fluorescence) or undergoing photoisomerization around the central methine bridge to the cis conformation in a non-radiative manner [47]. The photoisomer can return to the more stable ground state through the back thermal cis-trans isomerization reaction. The non-radiative decay rate through the trans-cis isomerization is predominately mediated by the viscosity of the local environment surrounding the dye molecule, leading to a viscosity-dependent fluorescence lifetime [48]. The relation between fluorescence lifetime (τ) and local viscosity (η) is expected to follow the Forster-Hoffmann equation [49]:

| (1) |

where C and α are fitting parameters. To establish this quantitative correlation, we measured the fluorescence lifetimes of DiO dissolved in glycerol/methanol mixtures of different ratios. As shown in Figure 2B, we confirmed that the fluorescence lifetime of DiO monotonically increased with the viscosity of the solution. A linear fitting yielded α = 0.2371 and C = 0.3706. Atomistic simulations have predicted that DiO molecules are more likely to stay in the close proximity of lipid head groups with the methine bridge parallel to the membrane surface [34]. Therefore, when they are embedded in the lipid bilayer, their fluorescence lifetime is expected to reflect the local viscosity near the lipid heads.

Figure 2. FLIM-based measurements of membrane viscosity of PHT cell-derived EVs.

(A) Schematics of trans-cis isomerization of DiO through twisting around the central methine bridge. (B) Plot of fluorescence lifetime of DiO as a function of glycerol/methanol solution viscosity. (C) Representative Raw fluorescence lifetime images from the SPCImage software after two-exponent fitting. The pseudo-colored dark pink to white indicates the mean fluorescence lifetime. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Fluorescence lifetime of DiO molecules in lipid membrane of EVs (*p < 0.05). (E) Membrane viscosity of the EVs (*p < 0.05). The number of experimental repeats for AB, MV and sEV groups is n = 12, 16 and 11, respectively, and error bars represent the corresponding standard deviation.

Quantifying the fluorescence lifetime of DiO molecules embedded in EV membrane is challenging due to the difficulty of excluding any possible photons collected from the regions not occupied by EVs. For samples with well-defined boundaries, such as cells and cell nuclei, a mask based on the corresponding phase contrast image or intensity-based thresholding approach can be used to ensure that photons are collected only within the defined region of interest. However, given the nanoscale dimensions of MVs and sEVs and our limited pixel resolution (~ 586 nm/pixel), it is impossible to manually differentiate the photons collected from the regions not occupied by EVs from those coming from the dyes embedded in the membrane of individual EVs (Supplementary Figure 2). Assuming that the fluorescence decay of the DiO within the EV membrane has different characteristics from the photons collected from outside, the decay of fluorescence intensity is expected to follow a multi-exponential decay model from which the average fluorescence lifetime can be calculated by , where τi and φi are the fluorescence lifetime and the corresponding fractional contribution of each component. We fitted the fluorescence decay curves with a double-exponential model, yielding a dominant short lifetime (70-90%) of around 1.0 ns and a long lifetime of greater than 2.0 ns. The short lifetime is consistent with the reported lifetime of carbocyanine dyes in lipid environments [50], while the long lifetime component is expected to reflect background autofluorescence [51], and/or the free dyes that stick to the surface. As shown in Figure 2C, the average fluorescence lifetime images clearly showed ABs and MVs with sizes consistent with the DIC and fluorescence images in Figure 1A. By performing fluorescence lifetime measurements on individual cells whose boundaries can be easily traced, we confirmed that the short lifetime component is a faithful reflection of the fluorescence lifetime of the DiO in EV membrane (Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2D showed the fluorescence lifetime of DiO in membranes of different types of EVs derived from PHT cells. The fluorescence lifetimes of DiO among ABs, MVs and sEVs were significantly different from each other. More specifically, the fluorescence lifetime from the MV membrane was the longest while that from sEVs the shortest, indicating that the membranes of MVs and sEVs were the most and least viscous, respectively. Note that this trend is qualitatively consistent with our observation based on the average fluorescence lifetime without excluding the contribution from autofluorescence of the surrounding, as shown in Figure 2C. Based on the quantitative relationship established between the fluorescence lifetime of DiO and the viscosity of their microenvironment, we inferred the membrane viscosity for different types of EVs (Figure 2E). The membrane viscosity of MVs was significantly higher than that of ABs and sEVs. The membrane viscosities measured using FLIM were all within the range of the reported viscosity of biological membranes [52].

We used artificial vesicles to assess the influence of membrane curvature on the fluorescence lifetime of DiO probes. Artificial vesicles of two different size ranges were synthesized using the lipid film hydration method [53]. To control vesicle size, self-assembled lipid vesicles were extruded through polycarbonate porous membranes 21 times (see Materials and Methods). The vesicle size distributions after extrusion were characterized using dynamic light scattering. As shown in Supplementary Figure 3A, the use of membranes with a pore diameter of 100 nm yielded an average vesicle diameter of 152.0 ± 50.9 nm, while the 1 μm diameter pores resulted in an average vesicle size of 677.4 ± 167.5 nm. We did not detect any significant difference in fluorescence lifetime of DiO molecules between these two vesicle groups (Supplementary Figure 3B), indicating a negligible effect of membrane curvature on the molecular organization of the lipid bilayer. In fact, both computational and experimental studies have suggested that the lipid packing is only sensitive to high membrane curvature [54,55]. Thus, the low viscosity of the sEV membrane is consistent with its high PC and low PE content, as revealed in our lipidomic analysis (Figure 1C). Similarly, the high viscosity of the MV membrane corresponds to its high PE content. This direct correlation between lipid composition and biophysical properties effectively validated our FLIM-facilitated optical approach to quantitatively characterize the membrane viscosity of EVs.

Hypoxic damage to PHT cells alters lipid composition and membrane viscosity of PHT cells-derived MVs

An important application of the current study is the following comparison of membrane viscosity of EVs secreted from PHT cells cultured under standard vs. hypoxic conditions. In the current study, however, we only characterized the properties of ABs and MVs considering their common origin from the plasma membrane during their biogenesis. To mimic the intrauterine hypoxic condition in vivo, we cultured PHT cells for 72 h under hypoxic condition at O2 ≤ 1% (see Materials and Methods). We then collected the ABs and MVs from the conditioned media, fluorescently labeled them with DiO dye, and measured the fluorescence lifetime of DiO molecules. As shown in Supplementary Figure 4, no significant difference in the fluorescence lifetime of DiO in the ABs was observed between the standard and hypoxic conditions. However, the fluorescence lifetime in the MVs obtained under hypoxic condition was significantly shorter than that in the MVs under standard condition (Figure 3A), suggesting that exposure to hypoxia made the MV membrane much less viscous. To examine the biochemical changes underlying the observed change in membrane viscosity, we performed lipidomics analysis for the MVs under standard vs hypoxic conditions. As shown in Figure 3B, exposure to hypoxia reduced the abundance of PE by ~6% but increased the PC content by ~6%. Both the reduction in PE and the increase in PC tend to result in a less viscous membrane, which is in consistent with the predicted change in membrane viscosity by our fluorescence lifetime measurements.

Figure 3. Phospholipid composition and membrane viscosity characterization of the PHT cell-derived MVs under standard and hypoxic conditions.

(A) Fluorescence lifetime of DiO molecules in lipid membrane of PHT cell-derived MVs (*p < 0.05). The number of experimental repeats for standard and hypoxic groups is n = 16 and 3, respectively. (B) The relative fraction of major phospholipids in PHT cell-derived MVs (*p < 0.05 and n = 3 for each group representing number of experimental repeats). Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviation.

Discussion

As one of most common pathological conditions during pregnancy, hypoxia alters placental metabolism and consequently may adversely affect normal fetal growth and development. It has been identified that placental trophoblasts are sensitive to the hypoxic stress and can respond in various ways, including enhanced lipid droplet accumulation [38], elevated glucose consumption [56], hindered differentiation into multinucleated syntiotrophoblasts and enhanced apoptosis [44,57], and reduced expression of enzymes involved in responses to oxidative stress [58]. In this study, we have demonstrated that trophoblast hypoxia also involves alteration to lipid homeostasis, which can be identified via characterization of EV membrane viscosity using FLIM. Our results show that the membrane of PHT MVs secreted under hypoxic condition is less viscous than its counterpart under standard culture condition. A direct correlation between the reduction in the viscosity of MV membrane and the increase in PC level while decrease in PE level has been established. This correlation is well supported by R. Dawaliby et. al.’s membrane fluidity measurements on liposomes made of POPE and POPC lipids of various ratios [59]. Since the MV is generated by directly budding off from the plasma membrane, we expect that a similar alteration will occur to the lipid composition of plasma membrane of the human trophoblasts. Hypoxia-induced increase in PC content has also been identified in erythrocytes [60]. As pointed out by R. Dawaliby et al., the ratio of PE to PC is a key regulator of membrane viscosity in eukaryotic cells [59]. Considering that a direct correlation between cell membrane viscosity and diseases has been previously established for various disease types [26-30], our study may serve as the foundation for developing liquid biopsy-based disease diagnostics, and suggest new ways to monitor therapeutics and predict prognosis.

For “standard” culture conditions we used ambient 20% O2. Although this concentration is higher than the range found in the placenta in vivo after the first trimester [61-63], these standard conditions are routinely used by us and others to maintain term villous PHT cells, especially when grown on plastic dishes without pulsatile blood perfusion as happens in vivo. Notably, in previous studies we did not find evidence for marked gene expression changes or phospholipid-mediated hyperoxic damage between trophoblasts cultured in 20% vs 8% [64,65]. The use of the more extreme oxygen-rich and oxygen-depleted conditions allowed us to better assess damage to trophoblasts by intrauterine hypoxia using analysis of EV membrane viscosity.

The small size (~30 – 1000 nm) of sEVs and MVs reduces the practicality and accuracy of the techniques that have been well established for the characterization of cell membrane viscosity, such as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching [66], fluorescence correlation spectroscopy [67] and single particle tracking [68]. In contrast, fluorescent molecular rotors represent a set of probes whose fluorescence properties provide direct insights into the physical properties of their surrounding molecular environment [31,69]. Fluorescence lifetime-based molecular rotors have been particularly effective as versatile viscosity probes, due to their insensitivity to the local fluorophore concentration. Distinct from the typical viscosity defined at a macroscopic level, the local viscosity regulated by the local molecular arrangement is sensed by molecular rotors embedded in lipid bilayers. They are able to inform the micro-viscosity in various biological systems, ranging from artificial model membranes to in vitro living cells and even in vivo analysis of tumor tissues [52,70-72]

Compared to atomic force microscopy (AFM) that has been commonly used to interrogate the mechanical properties of EVs [24,73-75], FLIM-based membrane viscosity characterization is significantly high-throughput with regard to the simultaneous number of vesicles that may be interrogated. In each measurement, the photons emitted from all EVs within the entire field of view (150 μm x 150 μm) are collected and analyzed to calculate the fluorescence lifetime. We have demonstrated that the fluorescence lifetime of DiO probes can faithfully reflect the molecular organization of the EV lipid bilayer, as supported by our phospholipidomic analysis.

In this study we focused on trophoblastic MVs and sEVs, which we have previously characterized in detail [12]. In future studies it will be important to associate changes in the protein or phospholipid composition of EV membranes with FLIM measurements. Considering that FLIM systems can be implemented on both laser scanning microscopy and wide-field illumination microscopy and are commercially available [32], our approach can be readily utilized to characterize the membrane viscosity of EVs in many other physiologically and pathologically relevant context.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Fluorescence lifetime measurements enable EV membrane viscosity characterization

Different types of EVs secreted from PHTs feature distinctive phospholipid compositions

Hypoxia induces reduction in PE-to-PC ratio in PHT microvesicles

Changes in microvesicle membrane viscosity faithfully reveal hypoxic injury to PHTs

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kris Noel Dahl and Dr. Mohammad F. Islam from Carnegie Mellon University for their technical support on the FLIM system.

Funding

This work was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [R01HD086325, R37HD086916]; Nanyang Technological University [M4082352, M4082428]; the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 1 [RG92/19]; National Institute of Health [S10OD023402].

Footnotes

Declarations of interest:

None

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Salavati N, Smies M, Ganzevoort W, Charles AK, Erwich JJ, Plösch T, Gordijn SJ, The Possible Role of Placental Morphometry in the Detection of Fetal Growth Restriction, Front. Physiol 9 (2019) 1884. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphys.2018.01884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jakó M, Surányi A, Kaizer L, Németh G, Bártfai G, Maternal Hematological Parameters and Placental and Umbilical Cord Histopathology in Intrauterine Growth Restriction, Med. Princ. Pract 28 (2019) 101–108. 10.1159/000497240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hughes G, Bischof P, Wilson G, Klopper A, Assay of a placental protein to determine fetal risk, Br. Med. J 280 (1980) 671–673. 10.1136/bmj.280.6215.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rajakumar A, Powers RW, Hubel CA, Shibata E, von Versen-Höynck F, Plymire D, Jeyabalan A, Novel soluble Flt-1 isoforms in plasma and cultured placental explants from normotensive pregnant and preeclamptic women, Placenta. 30 (2009) 25–34. 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gu Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y, Placental productions and expressions of soluble endoglin, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1, and placental growth factor in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 93 (2008) 260–266. 10.1210/jc.2007-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Huppertz B, Meiri H, Gizurarson S, Osol G, Sammar M, Placental protein 13 (PP13): a new biological target shifting individualized risk assessment to personalized drug design combating pre-eclampsia, Hum. Reprod Update. 19 (2013) 391–405. 10.1093/humupd/dmt003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tong S, Joy Kaitu’u-Lino T, Walker SP, MacDonald TM, Blood-based biomarkers in the maternal circulation associated with fetal growth restriction, Prenat. Diagn 39 (2019) 947–957. 10.1002/pd.5525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Holzgreve W, Miny P, Gerlach B, Westendorp A, Ahlert D, Horst J, Benefits of placental biopsies for rapid karyotyping in the second and third trimesters (late chorionic villus sampling) in high-risk pregnancies., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 162 (1990) 1188–1192. 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sadovsky Y, Wyatt SM, Collins L, Elchalal U, Kraus FT, Nelson DM, The use of needle biopsy for assessment of placental gene expression, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 194 (2006) 1137–1142. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Bedina Zavec A, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borràs FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan M, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman MLD, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Górecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzás EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DRF, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chaudhuri AD, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FAW, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, D’Souza-Schorey C, Das S, de Candia P, De Santana EF, De Wever O, del Portillo HA, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Di Vizio D, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Dominguez Rubio AP, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TAP, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekström K, EL Andaloussi S, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrügger U, Falcón-Pérez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Försönits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gámez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gärtner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DCI, Görgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AGE, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, ichi Kano S, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Klinke DJ, Kornek M, Kosanović MM, Kovács ÁF, Krämer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lässer C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Le Lay S, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li ITS, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Linē A, Linnemannstöns K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lörincz ÁM, Lötvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SLN, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, McGinnis LK, McVey MJ, Meckes DG, Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Möller A, Møller Jørgensen M, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Nolte-’t Hoen ENM, Noren Hooten N, O’Driscoll L, O’Grady T, O’Loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Ostegaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BCH, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Pogge von Strandmann E, Polakovicova I, Poon IKH, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KMA, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saá P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sánchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schøyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PRM, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Snyder OL, Soares RP, Sódar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, van Balkom BWM, van der Grein SG, Van Deun J, van Herwijnen MJC, Van Keuren-Jensen K, van Niel G, van Royen ME, van Wijnen AJ, Vasconcelos MH, Vechetti IJ, Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot É, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Viñas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MHM, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yáñez-Mó M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Žėkas V, ye Zhang J, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK, Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines, J. Extracell. Vesicles 7 (2018). 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Akers JC, Gonda D, Kim R, Carter BS, Chen CC, Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): Exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies, J. Neurooncol 113 (2013) 1–11. 10.1007/s11060-013-1084-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ouyang Y, Bayer A, Chu T, Tyurin V, Kagan V, Morelli AE, Coyne CB, Sadovsky Y, Isolation of human trophoblastic extracellular vesicles and characterization of their cargo and antiviral activity, Placenta. 47 (2016) 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dragovic RA, Collett GP, Hole P, Ferguson DJP, Redman CW, Sargent IL, Tannetta DS, Isolation of syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles and exosomes and their characterisation by multicolour flow cytometry and fluorescence Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis., Methods. 87 (2015) 64–74. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tong M, Chen Q, James JL, Stone PR, Chamley LW, Micro- and Nano-vesicles from First Trimester Human Placentae Carry Flt-1 and Levels Are Increased in Severe Preeclampsia, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 8 (2017) 174. 10.3389/fendo.2017.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tong M, Kleffmann T, Pradhan S, Johansson CL, DeSousa J, Stone PR, James JL, Chen Q, Chamley LW, Proteomic characterization of macro-, micro- and nano-extracellular vesicles derived from the same first trimester placenta: relevance for feto-maternal communication., Hum. Reprod 31 (2016) 687–699. 10.1093/humrep/dew004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Salomon C, Guanzon D, Scholz-Romero K, Longo S, Correa P, Illanes SE, Rice GE, Placental Exosomes as Early Biomarker of Preeclampsia: Potential Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs Across Gestation., J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 102 (2017) 3182–3194. 10.1210/jc.2017-00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tannetta D, Masliukaite I, Vatish M, Redman C, Sargent I, Update of syncytiotrophoblast derived extracellular vesicles in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia., J. Reprod. Immunol 119 (2017) 98–106. 10.1016/j.jri.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gill M, Motta-Mejia C, Kandzija N, Cooke W, Zhang W, Cerdeira AS, Bastie C, Redman C, Vatish M, Placental Syncytiotrophoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Carry Active NEP (Neprilysin) and Are Increased in Preeclampsia., Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex. 1979) 73 (2019) 1112–1119. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO, Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells, Nat. Cell Biol 9 (2007) 654–659. 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Candelario KM, Steindler DA, The role of extracellular vesicles in the progression of neurodegenerative disease and cancer, Trends Mol. Med 20 (2014) 368–374. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yoshioka Y, Kosaka N, Konishi Y, Ohta H, Okamoto H, Sonoda H, Nonaka R, Yamamoto H, Ishii H, Mori M, Furuta K, Nakajima T, Hayashi H, Sugisaki H, Higashimoto H, Kato T, Takeshita F, Ochiya T, Ultra-sensitive liquid biopsy of circulating extracellular vesicles using ExoScreen, Nat. Commun 5 (2014) 3591. 10.1038/ncomms4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Westphal M, Lamszus K, Circulating biomarkers for gliomas, Nat. Rev. Neurol 11 (2015) 556–566. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yang KS, Im H, Hong S, Pergolini I, Del Castillo AF, Wang R, Clardy S, Huang CH, Pille C, Ferrone S, Yang R, Castro CM, Lee H, Del Castillo CF, Weissleder R, Multiparametric plasma EV profiling facilitates diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy, Sci. Transl. Med 9 (2017) 1–11. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Whitehead B, Wu LP, Hvam ML, Aslan H, Dong M, DyrskjØt L, Ostenfeld MS, Moghimi SM, Howard KA, Tumour exosomes display differential mechanical and complement activation properties dependent on malignant state: Implications in endothelial leakiness, J. Extracell. Vesicles 4 (2015) 1–11. 10.3402/jev.v4.29685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zlotogorski-Hurvitz A, Dayan D, Chaushu G, Salo T, Vered M, Morphological and molecular features of oral fluid-derived exosomes: oral cancer patients versus healthy individuals, J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 142 (2016) 101–110. 10.1007/s00432-015-2005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].SHA’AFI RI, RODAN SB, HINTZ RL, FERNANDEZ SM, RODAN GA, Abnormalities in membrane micro viscosity and ion transport in genetic muscular dystrophy, Nature. 254 (1975) 525–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cocchi M, Tonello L, Lercker G, Fatty acids, membrane viscosity, serotonin and ischemic heart disease, Lipids Health Dis. 9 (2010) 9–11. 10.1186/1476-511X-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Batta G, Soltész L, Kovács T, Bozó T, Mészár Z, Kellermayer M, Szöllosi J, Nagy P, Alterations in the properties of the cell membrane due to glycosphingolipid accumulation in a model of Gaucher disease, Sci. Rep 8 (2018) 1–13. 10.1038/s41598-017-18405-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kaur J, Sanyal SN, Alterations in membrane fluidity and dynamics in experimental colon cancer and its chemoprevention by diclofenac, Mol. Cell. Biochem 341 (2010) 99–108. 10.1007/s11010-010-0441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang Y, Xu C, Jiang N, Zheng L, Zeng J, Qiu C, Yang H, Xie S, Quantitative analysis of the cell-surface roughness and viscoelasticity for breast cancer cells discrimination using atomic force microscopy, Scanning. 38 (2016) 558–563. 10.1002/sca.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Berezin MMY, Achilefu S, Fluorescence Lifetime Measurements and Biological Imaging, Chem. Rev 110 (2010) 2641–2684. 10.1021/cr900343z.Fluorescence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Datta R, Heaster TM, Sharick JT, Gillette AA, Skala MC, Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: fundamentals and advances in instrumentation, analysis, and applications, J. Biomed. Opt 25 (2020) 1. 10.1117/1.jbo.25.7.071203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gullapalli RR, Tabouillot T, Mathura R, Dangaria J, Butler PJ, Integrated multimodal microscopy, time-resolved fluorescence, and optical-trap rheometry: toward single molecule mechanobiology, J. Biomed. Opt 12 (2007) 1–17. 10.1117/1.2673245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Muddana HS, Gullapalli RR, Manias E, Butler PJ, Atomistic simulation of lipid and DiI dynamics in membrane bilayers under tension, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 13 (2011) 1368–1378. 10.1039/C0CP00430H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang C, Butler PJ, Tong S, Muddana HS, Bao G, Zhang S, Substrate stiffness regulates cellular uptake of nanoparticles, Nano Lett. 13 (2013) 1611–1615. 10.1021/nl400033h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Huang C, Ozdemir T, Xu LC, Butler PJ, Siedlecki CA, Brown JL, Zhang S, The role of substrate topography on the cellular uptake of nanoparticles, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater 104 (2016) 488–495. 10.1002/jbm.b.33397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mouillet JF, Chu T, Nelson DM, Mishima T, Sadovsky Y, MiR-205 silences MED1 in hypoxic primary human trophoblasts, FASEB J. 24 (2010) 2030–2039. 10.1096/fj.09-149724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bildirici I, Schaiff WT, Chen B, Morizane M, Oh S, Brien MO, Sonnenberg-hirche C, Chu T, Barak Y, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y, PLIN2 Is Essential for Trophoblastic Lipid Droplet Accumulation and Cell Survival During Hypoxia, Endocrinology. 159 (2018) 3937–3949. 10.1210/en.2018-00752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wu M, Ouyang Y, Wang Z, Zhang R, Huang P-H, Chen C, Li H, Li P, Quinn D, Dao M, Suresh S, Sadovsky Y, Huang TJ, Isolation of exosomes from whole blood by integrating acoustics and microfluidics, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114 (2017) 10584–10589. 10.1073/pnas.1709210114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mishima T, Miner JH, Morizane M, Stahl A, Sadovsky Y, The expression and function of fatty acid transport protein-2 and −4 in the murine placenta, PLoS One. 6 (2011) 1–8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yaron PN, Holt BD, Short PA, Lösche M, Islam MF, Dahl KN, Single wall carbon nanotubes enter cells by endocytosis and not membrane penetration, J. Nanobiotechnology 9 (2011) 1–15. 10.1186/1477-3155-9-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen B, Longtine MS, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM, Hypoxia downregulates p53 but induces apoptosis and enhances expression of BAD in cultures of human syncytiotrophoblasts., Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 299 (2010) C968–76. 10.1152/ajpcell.00154.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yusuf K, Smith SD, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM, Trophoblast differentiation modulates the activity of caspases in primary cultures of term human trophoblasts., Pediatr. Res 52 (2002) 411–415. 10.1203/00006450-200209000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Levy R, Smith SD, Chandler K, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM, Apoptosis in human cultured trophoblasts is enhanced by hypoxia and diminished by epidermal growth factor, Am. J. Physiol. Physiol 278 (2000) C982–C988. 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.5.C982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Haraszti RA, Didiot M, Sapp E, Leszyk J, Scott A, Rockwell HE, Gao F, Narain NR, Difiglia M, Kiebish MA, Aronin N, Khvorova A, Haraszti RA, Didiot M, Sapp E, Leszyk J, Scott A, Rockwell HE, Gao F, Narain NR, Difiglia M, Kiebish MA, Haraszti RA, Didiot M, Sapp E, Leszyk J, Difiglia M, Kiebish MA, Aronin N, Khvorova A, High-resolution proteomic and lipidomic analysis of exosomes and microvesicles from different cell sources, J. Extracell. Vesicles 5 (2016) 32570. 10.3402/jev.v5.32570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Seu KJ, Cambrea LR, Everly RM, Hovis JS, Influence of lipid chemistry on membrane fluidity: Tail and headgroup interactions, Biophys. J 91 (2006) 3727–3735. 10.1529/biophysj.106.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Levitus M, Ranjit S, Cyanine dyes in biophysical research: The photophysics of polymethine fluorescent dyes in biomolecular environments, Q. Rev. Biophys 44 (2011) 123–151. 10.1017/S0033583510000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Widengren J, SchwiÏle P, Characterization of photoinduced isomerization and back-isomerization of the cyanine dye cy5 by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, J. Phys. Chem. A 104 (2000) 6416–6428. 10.1021/jp000059s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Forster T, Hoffmann G, VISCOSITY DEPENDENCE OF FLUORESCENT QUANTUM YIELDS OF SOME DYE SYSTEMS, Zeitschrift Fur Phys. Chemie-Frankfurt 75 (1971) 63. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Packard BS, Wolf DE, Fluorescence Lifetimes of Carbocyanine Lipid Analogues in Phospholipid Bilayers, Biochemistry. 24 (1985) 5176–5181. 10.1021/bi00340a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Patalay R, Talbot C, Alexandrov Y, Munro I, Neil MAA, König K, French PMW, Chu A, Stamp GW, Dunsby C, Quantification of cellular autofluorescence of human skin using multiphoton tomography and fluorescence lifetime imaging in two spectral detection channels, Biomed. Opt. Express 2 (2011) 3295. 10.1364/BOE.2.003295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kuimova MK, Mapping viscosity in cells using molecular rotors, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 14 (2012) 12671. 10.1039/c2cp41674c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhang H, Thin-Film Hydration Followed by Extrusion Method for Liposome Preparation, in: D’Souza GGM (Ed.), Liposomes Methods Protoc., Springer New York, New York, NY, 2017: pp. 17–22. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6591-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cooke IR, Deserno M, Coupling between lipid shape and membrane curvature, Biophys. J 91 (2006) 487–495. 10.1529/biophysj.105.078683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kamal MM, Mills D, Grzybek M, Howard J, Measurement of the membrane curvature preference of phospholipids reveals only weak coupling between lipid shape and leaflet curvature, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 106 (2009) 22245–22250. 10.1073/pnas.0907354106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Estermana A, Greco MA, Mitani Y, Finlay TH, Ismail-Beigi F, Dancis J, The Effect Glucose of Hypoxia on Human Trophoblast in Culture : Morphology , Transport and Metabolism, Placenta. 18 (1997) 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Alsat E, Wyplosz P, Malassiné A, Guibourdenche J, Porquet D, Nessmann C, Evain-Brion D, Hypoxia impairs cell fusion and differentiation process in human cytotrophoblast, in vitro, J. Cell. Physiol 168 (1996) 346–353. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hoang VM, Foulk R, Clauser K, Burlingame A, Gibson BW, Fisher SJ, Functional Proteomics : Examining the Effects of Hypoxia on the Cytotrophoblast Protein Repertoire, Biochemistry. 40 (2001) 4077–4086. 10.1021/bi0023910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dawaliby R, Trubbia C, Delporte C, Noyon C, Ruysschaert JM, Van Antwerpen P, Govaerts C, Phosphatidylethanolamine is a key regulator of membrane fluidity in eukaryotic cells, J. Biol. Chem 291 (2016) 3658–3667. 10.1074/jbc.M115.706523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Revin V, Grunyushkin I, Gromova N, Revina E, Abdulvwahid ASA, Solomadin I, Tychkov A, Kukina A, Effect of hypoxia on the composition and state of lipids and oxygen-transport properties of erythrocyte haemoglobin, Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip 31 (2017) 128–137. 10.1080/13102818.2016.1261637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E, Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy., Obstet. Gynecol 80 (1992) 283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Jauniaux E, Watson A, Burton G, Evaluation of respiratory gases and acid-base gradients in human fetal fluids and uteroplacental tissue between 7 and 16 weeks’ gestation., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 184 (2001) 998–1003. 10.1067/mob.2001.111935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Burton GJ, Cindrova-Davies T, Yung HW, Jauniaux E, HYPOXIA AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH: Oxygen and development of the human placenta., Reproduction. 161 (2021) F53–F65. 10.1530/REP-20-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Oh S-Y, Chu T, Sadovsky Y, The timing and duration of hypoxia determine gene expression patterns in cultured human trophoblasts., Placenta. 32 (2011) 1004–1009. 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Beharier O, Tyurin VA, Goff JP, Guerrero-Santoro J, Kajiwara K, Chu T, Tyurina YY, St Croix CM, Wallace CT, Parry S, Parks WT, Kagan VE, Sadovsky Y, PLA2G6 guards placental trophoblasts against ferroptotic injury., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 117 (2020) 27319–27328. 10.1073/pnas.2009201117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Axelrod D, Koppel DE, Schlessinger J, Elson E, Webb WW, Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics, Biophys. J 16 (1976) 1055–1069. 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Chiantia S, Ries J, Schwille P, Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy in membrane structure elucidation, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr 1788 (2009) 225–233. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Saxton MJ, Jacobson K, SINGLE-PARTICLE TRACKING: Applications to Membrane Dynamics, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 26 (1997) 373–399. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Haidekker MA, Theodorakis EA, Molecular rotors—fluorescent biosensors for viscosity and flow, Org. Biomol. Chem 5 (2007) 1669–1678. 10.1039/B618415D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Kowada T, Maeda H, Kikuchi K, BODIPY-based probes for the fluorescence imaging of biomolecules in living cells, Chem. Soc. Rev 44 (2015) 4953–4972. 10.1039/C5CS00030K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kuimova MK, Yahioglu G, Levitt JA, Suhling K, Molecular Rotor Measures Viscosity of Live Cells via Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging, J. Am. Chem. Soc 130 (2008) 6672–6673. 10.1021/ja800570d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Shimolina LE, Izquierdo MA, López-Duarte I, Bull JA, Shirmanova MV, Klapshina LG, Zagaynova EV, Kuimova MK, Imaging tumor microscopic viscosity in vivo using molecular rotors, Sci. Rep 7 (2017) 1–11. 10.1038/srep41097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Parisse P, Rago I, Ulloa Severino L, Perissinotto F, Ambrosetti E, Paoletti P, Ricci M, Beltrami AP, Cesselli D, Casalis L, Atomic force microscopy analysis of extracellular vesicles, Eur. Biophys. J 46 (2017) 813–820. 10.1007/s00249-017-1252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Sharma S, Rasool HI, Palanisamy V, Mathisen C, Schmidt ЌM, Wong DT, Gimzewski JK, Structural-Mechanical Characterization of Nanoparticle Exosomes in Human Saliva, Using Correlative AFM, FESEM, and Force Spectroscopy, ACS Nano. 4 (2010) 1921–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Vorselen D, van Dommelen SM, Sorkin R, Piontek MC, Schiller J, Döpp ST, Kooijmans SAA, van Oirschot BA, Versluijs BA, Bierings MB, van Wijk R, Schiffelers RM, Wuite GJL, Roos WH, The fluid membrane determines mechanics of erythrocyte extracellular vesicles and is softened in hereditary spherocytosis, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 4960. 10.1038/s41467-018-07445-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.