Abstract

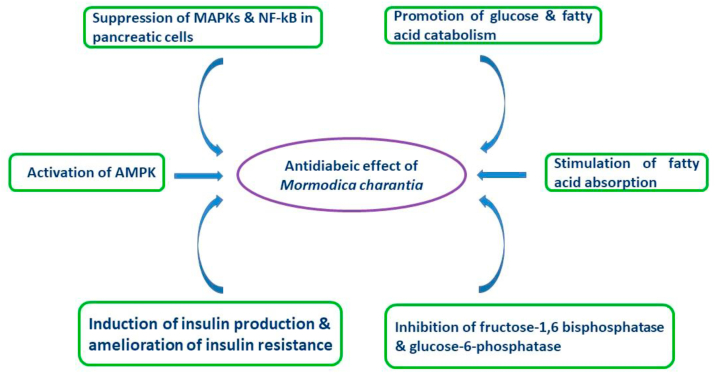

Diabetes mellitus is the most well-known endocrine dilemma suffered by hundreds of million people globally, with an annual mortality of more than one million people. This high mortality rate highlights the need for in-depth study of anti-diabetic agents. This review explores the phytochemical contents and anti-diabetic mechanisms of M. charantia (cucurbitaceae). Studies show that M. charantia contains several phytochemicals that have hypoglycemic effects, thus, the plant may be effective in the treatment/management of diabetes mellitus. Also, the biochemical and physiological basis of M. charantia anti-diabetic actions is explained. M. charantia exhibits its anti-diabetic effects via the suppression of MAPKs and NF-κβin pancreatic cells, promoting glucose and fatty acids catabolism, stimulating fatty acids absorption, inducing insulin production, ameliorating insulin resistance, activating AMPK pathway, and inhibiting glucose metabolism enzymes (fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and glucose-6-phosphatase). Reviewed literature was obtained from credible sources such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science.

Keywords: Momordica charantia, Diabetes mellitus, Anti-diabetic, Phytochemical, Cucurbitaceae, Hypoglycemic, Hyperglycemia

Momordica charantia, Diabetes mellitus, Anti-diabetic, Phytochemical, Cucurbitaceae, Hypoglycemic, Hyperglycemia.

1. Introduction

Momordica charantia (M. charantia), also known as bitter melon, karela, bitter gourd, or balsam pear, is a medicinal plant from the Cucurbitaceae family; it is predominantly cultivated in Africa, Asia, and South America [1, 2]. The name bitter guard or melon is given to it due to the fruit's bitter flavor, which becomes more pronounced as it ripens. Bitter melon is a medicinal plant with diverse beneficial effects [3], although mainly known for its anti-diabetic effects [4]. The anti-diabetic effects of M. charantia can be attributed to its different bioactive substances such as vicine, charantin, glycosides, karavilosides, polypeptide-p, and plant insulin [5]. These bioactive compounds belong to the broad class of phytochemicals: triterpene, protein, steroids, alkaloids, inorganic, lipid, and phenolic compounds [6, 7]. M. charantia's anti-diabetic activities are reported in both type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Moreover, all morphological parts of M. charantia demonstrated hypoglycemic activity in normal animals [8], alloxan-induced diabetic [9, 10], streptozotocin-induced diabetic model [11, 12], as well as diabetes genetic models [13]. In exploratory animal models, M. charantia has shown encouraging impacts in preventing diabetes mellitus and retarding the advancement of diabetic complications, including neuropathy, gastroparesis, nephropathy, waterfall, and insulin obstruction [8].

2. Methodology

A literature search was performed using PubMed, Scopus, and Google scholars on all original research articles as well as review articles written in English on phytochemical constituents and antidiabetics/hypoglycemic effect of M. Charantia within the past 25 years majorly using keywords such as ‘Momordica Charantia’, ‘Momordica Charantia + phytochemicals’, ‘Momordica Charantia + phytoconstituent’, ‘Momordica Charantia + extracts + Antidiabetics’, ‘Momordica Charantia + Antidiabetics’, ‘Momordica Charantia + hypoglycemic, ‘Momordica Charantia + extracts + hypoglycemic’. Figures were designed using, Corel Draw, online software.

3. The global burden of diabetes mellitus occurrence and mortality

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a mixture of heterogeneous problems, is usually characterized by hyperglycemia and glucose bigotry scenes resulting from the lack of insulin production, insulin resistance, or both [14]. Such complications are discernible to the absence of homeostasis in the frameworks liable for the metabolism of biomolecules [15]. DM is a significant precursor of visual impairment, kidney distress, coronary failures, stroke, and lower appendage removal [15]. It is right now a typical and genuine wellbeing concern internationally [16], and the most well-known endocrine dilemma, with approximately 690 million cases prophesied in 2045 [17]. To mitigate against this foreseen spurt in the number of diabetic patients in the near future, it is expedient to accord attention to natural products such as M. charantia that could be maximized in the therapy of DM.

4. Reported anti-diabetic activities of extracts of M. charantia

The anti-diabetic impacts of various extracts of M. charantia have been detailed in various scientific studies. Kar et al. documented the hypoglycemic effect of ethanolic sections of M. charantia (250 mg/kg) within 14 days of treatment in an alloxan-induced diabetic murine model [18]. Consecutive use of aqueous and ethanol extracts of M. charantia (200 mg/kg, orally) in alloxan- and streptozotocin- induced diabetic rats resulted in a critical reduction in plasma glucose levels after 21 days, though; the aqueous extract is found more effective [19]. The mash saponin-free methanolic concentrate of M. charantia has a huge antiglycemic impact on fasting and post-prandial conditions in normal, glucose-treated normal and non insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus rats [8]. M. charantia treatment of alloxan diabetic rats impeded cataract development, observed at 100 days in untreated diabetic rats [20]. Another study documented that, regular administration of a high dose of M. charantia extracts to alloxanized diabetic rats (120 mg/kg) for 2–8weeks delayed cataract progression to 140–180 days compared to 90–100 days in control rats [21]. Oral administration of aqueous extracts of M. charantia (400 mg/day for 15 days) to fructose-rich dietary fed rats considerably forestalled hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in comparison with fructose-rich fed untreated groups [22]. Seared M. charantia fruits devoured as a daily food supplement influence a minor but crucial increase in glucose tolerance in diabetic animals/subjects with no expansion in serum insulin levels [23]. In another clinical investigation, a homogenized suspension of M. charantia given to 100 cases of moderate T2DM human subjects resulted in a significant (P < 0.001) decrease in post-prandial serum glucose (86% cases) and fasting glucose (5% cases) [8]. Welihindaa et al. reported glucose tolerance upregulation in 73% of patients with maturity-onset diabetes administered with M. charantia fruit juice [24].

5. Phytochemical contents of Momordica Charantia

Over the years, many phytochemicals have been isolated and identified from M. charantia [25]. These bioactive compounds include numerous sterols, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, proteins, peptides, amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty acids, flavonoids, vitamins, and metals.

5.1. Phytosterols

Phytosterols, a group of sterols, can have up to 30 carbon atoms and are present in low concentrations in plants [26]. There are >200 different known plant sterols [26] with different therapeutic activities such as anti-cholesterol [27], anticancer [28], immunomodulation [26], skin protection [29], hypocholesterolemia [30], anti-inflammatory, atherosclerotic, and antioxidant activities [31, 32, 33]. Various phytosterols identified in M. charantia are Daucosterol, β-sitosterol [34], Campesterol, Stigmasterol, β-sitosterol [35], β-sitosterol [36], 25ξ-isopropenylchole-5,(6)-ene-3-O-β-D-lucopyranoside [37], Δ5–avenasterol, 25,26-dihydroelasterol [38], clerosterol, 5α-stigmasta-7-en-3β-ol [39], β-sitosterol, Stigmasterol, and Diosgenin [40].

5.2. Terpenoids

Terpenoids are the largest and most far-reaching class of secondary metabolites, predominantly in plants and lower spineless creatures [41]. Their biological activities include anticancer, anti-inflammatory [42], plant growth promotion [43] and reduction of cardiovascular disease. The predominant terpenoids found in M. charantia are cucurbitane-type terpenoids which include, 3-[(5β,19-epoxy-19,25-dimethoxycucurbita-6,23-dien-3-yl)oxy]-3-oxopropanoic acid, (3-[(5β,19-epoxy-19,25-dimethoxycucurbita-6,23-dien-3-yl)-2-oxoacetic acid, 3-[(5-formyl-7β-methoxy-7,23S-dimethoxycucurbita-5,23-dien3-yl)oxy]-3-oxopropanoic acid, 3-[(5-formyl-7β-hydroxy-25-methoxycucurbita-5,23-dien-3-yl)-oxy]-3-oxopropanoic acid, 3-[(5-formyl-7β,25- dihydroxymethoxycucurbita-5,23-dien-3-yl)- oxy]-3- oxopropanoic acid, and 3-[(25-O-methylkaravilagenin D-3- yl)oxy]-2-oxoacetic acid [44]. Other active terpenoids identified in M. charantia are charantin A and B, 3b,7b,25-trihydroxycucurbita-5,(23E)- dien-19-al, 28-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl, (1→3)-β-D-xylopyranosyl, 3β,7β-dihydroxy-25-methoxycucurbita-5,23- diene-19-al [45], charantagenins D and E [46], kuguaosides A, B, C and D, charantoside A, momordicosides I, F1, F2, K, L and U, goyaglycosides-b, goyaglycosides-d, 3-O-β-D-allopyranoside, 25-hydroxy-5β,19-epoxycucurbita-6,23-dien-19-on-3β-ol, 7β,25-dihydroxycucurbita-5,23(E)-dien-19-al, 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside [47], phytol [48] Kuguacin B, J, L, M, P and S [49], 5β,19-epoxy-25- methoxy-cucurbita-6,23-diene-3b,19-diol [38], (1→4)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl, (1→2)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl, 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl, (1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosiduronic acid, (1→3)]-β-D-fucopyranosylgypsogenin, (1→2)-[α-L-rhamnopyranosyl, (1→3)]-β-D-fucopyranosylgypsogenin, 28-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl, (1→4)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl, (1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosiduronic acid, 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl, [50], 5β,19-epoxycucurbitane triterpenoids [51], karavilagenin F, karaviloside XII and XIII, momordicine I, II, VI, VII and VIII [52].

5.3. Fatty acids

Organic compounds with saturated or unsaturated carbonic chain terminated by a carboxyl group (-COOH) are generally known as fatty acids [53, 54]. Among other roles, plant fatty acids can forestall or decrease the danger of creating cardiovascular sicknesses [55]. Their anti-bacteria [56] and anti-fungal [57] properties have also been reported. The various fatty acids found in M. charantia include palmitic [58, 59, 60, 61, 62]; myristic [58, 61, 63], pentadecanoic [58, 61, 63]; arachidic [58, 59, 60, 62, 63]; palmitoleic acids [58, 61, 63], stearic [35, 60, 62, 64], oleic [58, 59, 60, 62, 63], α-linolenic [58, 61, 62, 63], linoleic [58, 59, 60, 63], capric [59], lauric [59, 61, 63], docosanoic [61, 63], heneicosanoic [61, 62, 63], nonadecanoic [61, 63], decanoic [61, 63], tridecanoic [61, 62, 63], gadoleic acids [60], α-eleostearic [35, 60], heptadecanoic [61], tetracosanoic acids [61], behenic and lignoceric acids [62].

5.4. Phenolic compounds

Phenolics are auxiliary metabolites found in plants with benzene-like structure. They exist as coumarins, flavonoids, lignins, lignans, ordinary phenols, phenolic acids, and tannins [65]. The pharmacological effects of phenols include antioxidant, anti-microbial, anti-HIV-1, and anticancer activities [66, 67, 68, 69]. Various phenolic compounds isolated from M. charantia include gallic, kaempferol, chlorogenic, caffeic acid, catechin, rutin, quercetin [70], ellagic acids [71], epicatechin [71, 72], quercitrin, isoquercitrin, [71], ferulic acids, protocatechuic [72, 73, 74], tannic [72], vanillic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxylbenzoic, [72, 74], epigallocatechin, gallocatechingallate [72], myricetin, syringic [73, 74], apigenin, apigenin-7-O–glycoside, 3- coumaric, 4- coumaric acids, luteolin, luteolin-7-O-glycoside, naringenin-7-O-glycoside [73], biochanin a, gentisic, hesperidin, homogentisic acids, naringenin, naringin, β-resorcylic, salicylic, tcinnamic and veratric acids [74].

5.5. Amino acids

The fruits of M. charantia have been shown to possess certain amino acids. These amino acids are both essential and non-essential amino acids; they include alanine, aspartic acid, butyric acid, g-amino, glutamic acid, isoleucine, leucine, luteolin, methionine, phenylalanine, pipecolic acid, serine, threonine, and valine [75]. All amino acids have a general molecular structure contains a chiral center and two functional groups – amino and carboxyl groups.

5.6. Vitamins

The presence of specific vitamins, which include vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin B12, and folic acids, have been confirmed in small quantities in the dried leave of M. charantia. Constrastively, vitamin B3, vitamin B6, vitamin D, and vitamin K are found in trace amounts in the plant's methanol and pet-ether leaf extract [76].

5.7. Peptides and proteins

Proteins, a class of large biomolecule, have diverse biological roles in living organisms. From various morphological parts of M. charantia, a variety of peptides and proteins have been discovered and extracted. Various proteins isolated from M. charantia are highlighted below.

5.7.1. Ribosome inactivating proteins (RIPS)

Ribosome inactivating proteins (RIPs), a class of proteins, have drawn the attention of numerous specialists by virtue of their conceivably exploitable bioactivities. Ribosome-inactivating proteins are toxic N-glycosidases that depurinate eukaryotic and prokaryotic rRNAs, thereby arresting protein synthesis during translation [77]. RIPs are classified as type I or type II based on the number of subunits they contain. Type I RIPs isolated from M. charantia are single-chained. RIPs isolated and characterized from M. charantia are α-, β-, γ-, δ- and ε-momorcharin, momordica anti-HIV protein (MAP30), momordica charantia lectin, momordin, and trichosanthin. Various pharmacological activities of RIPs include anticancer, anti-microbial, anti-tumor, DNase-like, immunosuppressive, phospholipase, RNA N-glycosidase and superoxide dismutase, activities [78, 79, 80, 81].

5.7.2. Polypeptide-P

Polypeptide-P is a hypoglycemic glycoprotein peptide. It is derived from M. charantia's fruit, seeds, and tissues [82]. Two types of polypeptide-P with molecular weights of approximately 11 kD (166 amino acids) and 3.4 kD have been isolated from M. charantia [83]. It is crucial in cell recognition and adhesion reactions and has also been isolated from bitter melon [84].

5.7.3. Inhibitory proteins

Inhibitory proteins such as elastase inhibitors [85], α-glucosidase inhibitor [86], guanylatecyclase inhibitors [87], trypsin inhibitors (MC-I, -II and -III) [88], HIV inhibitory proteins like MRK29 (28.6 kDa) [89], MAP30 (30 kDa) and lectin [82] are isolated from M. charantia.

5.7.4. P-insulin

P-insulin, a phytoconstituent of M. charantia, is supposed to be a polypeptide hypoglycemic substance with a molecular weight of ∼11 kDa and comprises 166 amino acids [83]. P- insulin is found in bitter melon fruits, seeds, and several tissue cultures [3].

5.7.5. Other proteins

Apart from the specific proteins mentioned above, other proteins and peptides documented in M. charantia are peroxidase (43 kDa), momordica cyclic peptides [90], antifungal protein, cysteine knot peptides, MCha-Pr, and RNase MC2 (weight, 14 kDa) [91].

5.8. Polysaccharides

Polysaccharides rank among the essential bioactive constituents of Momordica charantia. The polysaccharides contents of M. charantia may be influenced by different conditions [92]. These polysaccharides are composed of different saccharide units, including arabinose, galactose, glucose, mannose, and rhamnose, and are thus classified as heteropolysaccharides [93]. The major polysaccharides isolated from M. charantia are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of polysaccharides isolated from Momordica charantia, their characteristics, and biological functions.

| Types of polysaccharides | Composition | Ratio of composition | Molecular weight | Biological functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic and branched heteropolysaccharide | galacturonic acid, mannose, rhamnose, galactose, glucose, xylose and arabinose | 0.01: 0.15: 0.02: 0.38: 0.31: 0.05: 0.09 | 92 kDa | antioxidant, α-amylase inhibition and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition | [94] |

| Pectic polysaccharide | 1,4,5-tri-O-acetyl-2,3,6-tri-O-methyl-D-galactitol, 1,2,4,5-tetra-O-acetyl-3,6-di-O-methyl-D-galactitol and 1,5-di-O-acetyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-methyl-D-galactitol | 3:1:1 | 20 kDa | Undefined | [95] |

| Water-soluble polysaccharides | Arabinose, xylose, galactose and rhamnose | 1.00: 1.12: 4.07: 1.79 | 1.15 × 106 Da | hypoglycemic effect | [96] |

Majorly, M. charantia polysaccharides improve cell death, hyperlipidemia, inflammation and oxidative imbalance during myocardial infarction by hindering the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) flagging pathway [97]. M. charantia polysaccharides additionally could improve overall volatile fatty acids generation, regulate the rumen fermentation pathway and impact the quantity of cellulolytic bacteria populace [98].

6. Mechanisms of anti-diabetic effect of M. charantia

Several scientists have researched the hypoglycemic and antiglycemic impacts of the various concentrates and compounds of M. charantia in human and animal models [8, 83]. M. charantia and its various concentrates and extracts applied their hypoglycemic impacts through various pharmacological, physiological, and biochemical modes [99, 100]. The reported modes of M. charantia anti-diabetic exercises include hypoglycemic activity [39, 94], incitement of glucose to the peripheral and skeletal muscles [95], restriction of intestinal glucose take-up [96, 101], hindrance of adipocyte differentiation [102], concealment of main gluconeogenic enzymes [103], incitement of the main biocatalyst of glycolytic pathway [104], and safeguarding of islet β cells and their capacities [105].

In this review, -we explicitly show that M. charantia exhibits its anti-diabetic effects through the suppression of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and NF-κβ in pancreatic cells, promotion of glucose and fatty acids catabolism, stimulation of fatty acids absorption, induction of insulin production, amelioration of insulin resistance, activation of AMP –-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and inhibition of glucose metabolism enzymes (fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and glucose-6-phosphatase) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of the anti-diabetic effects of Momordica charantia.

6.1. Suppression of MAPKs and NF-кB in pancreatic Β-cells

Cellular death of pancreatic β-cells is a key event in the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes [106]. The apoptosis of the β-cell is a systemic process triggered by cytokines family- interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrotic factor-alpha (TNF-α). These cytokines actuates several MAPKs such as stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinases (SAPK/JNKs), p38 MAPK, and p44/42 MAPK or extracellular-regulated protein kinases (ERKs), and NF-κB [107], thus leading to the pancreatic β-cells death (Figure 2) [108]. IL-1β triggers cell death by activating SAPK/JNK, p38, and p44/42 MAPKs [107]. SAPK/JNKs phosphorylates Bcl-2 which culminated in the release of mitochondrial cytochrome C [109]; p38 triggers apoptotic death of pancreatic β-cells in a similar manner [110]. SAPK/JNK is also triggered via the synergistic action of IFN-γ and TNF-α [111]. Cytokines can also promote cell death via the activation of NF-κB; NF-κB activation leads to the actuation of caspase-3 activity [112].

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of pancreatic β-cells death. Cytokines trigger apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells in two ways. (1) Cytokines (-IL-1β, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) activates MAPKs (SAPK/JNKs, p38 MAPK, and p44/42 MAPK or ERKs); the activated MAPKs phosphorylate BCl-2; the phosphorylated Bcl-2 activates cytochrome C; the activated cytochrome C recruits Apaf 1 and together converts procaspase 9 to caspase 9; caspase 9 converts procaspase 3 to caspase 3, leading to cell death. (2) Alternatively, activation of NF-κB by cytokines leads to the release of caspase 3; culminating in cell death.

Kim and Kim [113] detailed that M. charantia aqueous ethanol can inhibit the cytokine-induced pancreatic β-cells death by stifling the actuation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), p38, and p44/42 MAPK, MEK 1/2 and the activity of NF-κB in a pancreatic β-cells animal model (SV40 T-transformed insulinoma MIN6N8 cells derived from nonobese diabetic mice).

6.2. Promotion of glucose and fatty acids catabolism and fatty acid absorption

One study revealed that the M. charantia seeds improve the serum and liver lipid profiles and serum glucose levels by inducing the expression of the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) gene in the adipose tissue [105]. 9c,11t,13t-CLN is the phytochemical compound involved in the activation of PPAR-γ in M. charantia (Figure 3) [114].

Figure 3.

Structure of 9c,11t,13t-CLN.

PPAR-γ is a member of PPARs, a subfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors of the nuclear hormone receptors superfamily [115]. PPARs, generally a critical factor in the regulation of the many genes, are involved in coordinating several cellular and metabolic processes such as metabolism of glucose, lipoprotein and triglyceride, energy homeostasis, de novo lipogenesis, uptake, storage, oxidation, and transport of fatty acid, etc. [116, 117, 118, 119, 120]. M. charantia seed ameliorates hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia by acting as a PPAR-γ ligand activator, which stimulates the expression of genes involved in lipid catabolism and glucose utilization (Figure 4) [121]. The stimulation of PPAR-γ has been proven to reduce plasma triglyceride and free fatty acids levels by promoting their breakdown through the induction of lipoprotein lipase [122]. Furthermore, PPAR-γ stimulates cellular differentiation, enhances lipid storage, and regulates insulin activities in the adipose tissue [123]. Activators of PPAR-γ also enhance insulin sensitivity via adipogenesis stimulation and post-prandial fatty acid/triacylglyceride storage within the adipocytes [124].

Figure 4.

M. charantia improves serum and hepatic lipid profiles and blood sugar levels. M. charantia induces the release of PPAR-γ from the adipose tissue and the released PPAR-γ exhibits anti-diabetic action via three means: (1) by increasing the rates of glycolysis (2) degradation of TAG by increasing the expression of lipoprotein lipase enzymes (3) enhancement of insulin sensitivity by stimulating adipogenesis and increasing the storage of TAG; this leads to increased fatty acid absorption and reduction in lipid level.

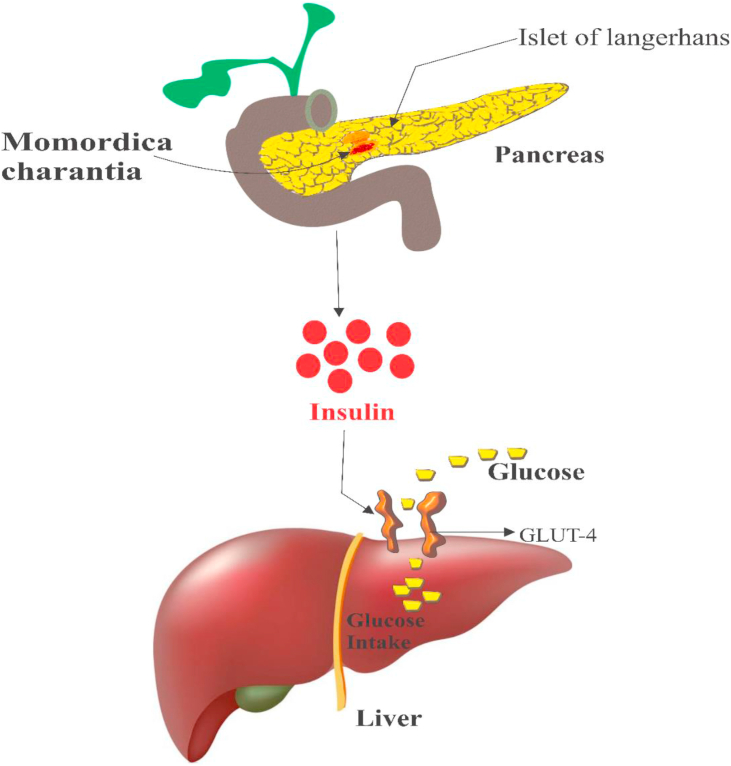

6.3. Induction of insulin production and amelioration of insulin resistance

Jeewathayaparan et al. [125] exhibited that oral administration of M. charantia could prompt insulin emission from endocrine pancreatic β cells; this result was later corroborated by Ahmed et al. [126], who explored the impact of the day to day oral administration of M. charantia natural product juice on the action of α, β and δ cells in the pancreas of STZ-initiated diabetic rodents. Administration of M. charantia alcohol concentration to alloxan-induced diabetic rats shows a strong hypoglycemic effects and significantly improved the islets of Langerhans [127]. Other studies showed that M. charantia could stimulate the emission of insulin from the endocrine pancreas and elicit glucose absorption in the liver (Figure 5) [101]. We proposed a mechanism by which the aforementioned effects are achieved - the recruitment of GLUT-4 transporter (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Induction of insulin discharge from β-cells of islets of Langerhans. M. charantia induces the secretion of insulin from the β-cell of the islet of Langerhans in the pancreas. The released insulin recruits GLUT-4 transporters which allow the absorption of glucose into the liver.

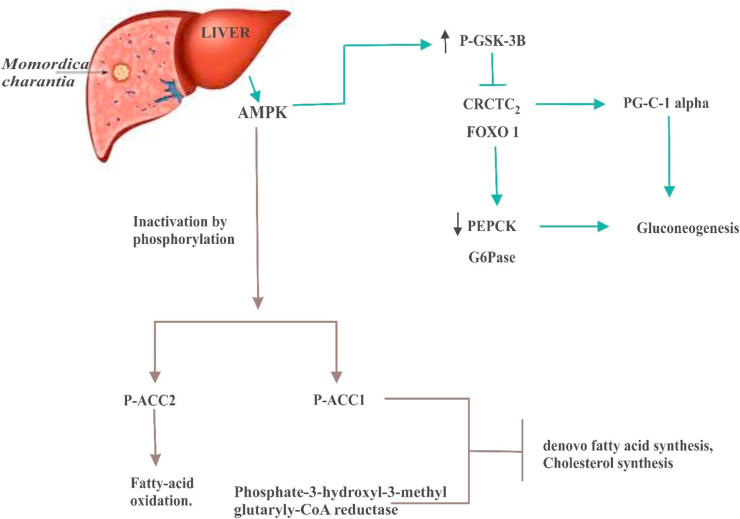

6.4. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha

M. charantia fruits have likewise indicated the capacity to upgrade cells' glucose take-up, advance insulin discharge, and potentiate insulin's impact. Bitter melon's bioactive content enacts a protein called AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase α), which is notable for controlling energy given foods digestion and empowering forms of glucose take-up, which are impeded in diabetes patients [128]. The mechanisms of anti-diabetes activities of AMPK are well characterized in the liver and the muscle tissues [129]. In the liver AMPK inhibits gluconeogenesis by suppressing the synthesis of key genes such as CREB-regulated transcription co-activator 2 (CRTC2) and forkhead Box O1 (FOXO) [130]. The actions of AMPK in the liver also leads to inhibition of de novo fatty acid synthesis and cholesterol synthesis as well as activation of fatty acid catabolism (Figure 6) [131]. M. charantia can also induce activation of AMPK in the muscle tissue, resulting primarily into an increment of fatty acid oxidation in the mitochondria and cytoplasm (Figure 7) [132].

Figure 6.

M. charantia inhibits gluconeogenesis, fatty acid synthesis, and cholesterol synthesis in the liver via the activation of AMPK. AMPK inhibits gluconeogenesis by suppressing the action of CRCTC2 and FOXO1 (genes that are critical in the activation of gluconeogenesis) either directly or indirectly (by increasing the synthesis of P-GSK-3β). The suppression of CRCTC2 and FOXO1 can promote the synthesis of PG-C1α or decrease the action of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase). AMPK also inactivates acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) and 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase leading to the inhibition of de novo synthesis of fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis. ACC2 is also phosphorylated by AMPK, resulting in increased fatty acid oxidation.

Figure 7.

M. charantia upregulates fatty acid oxidation in the muscle via the activation of AMPK. M. charantia induces the activity of AMPK in the muscle. AMPK increases the cellular level of NAD + which further increases the activity of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) leading to the activation of Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) via deacetylation and the activated PGC-1α promotes the catabolism of fatty acid in the mitochondria. Suppression of CRCTC2 by AMPK also promotes the activation of PGC-1α, leading to the catabolism of fatty acid in the mitochondria; AMPK increases fatty acid catabolism by decreasing the level of malonyl CoA via a coordinated inhibition of ACC and activation of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MCD).

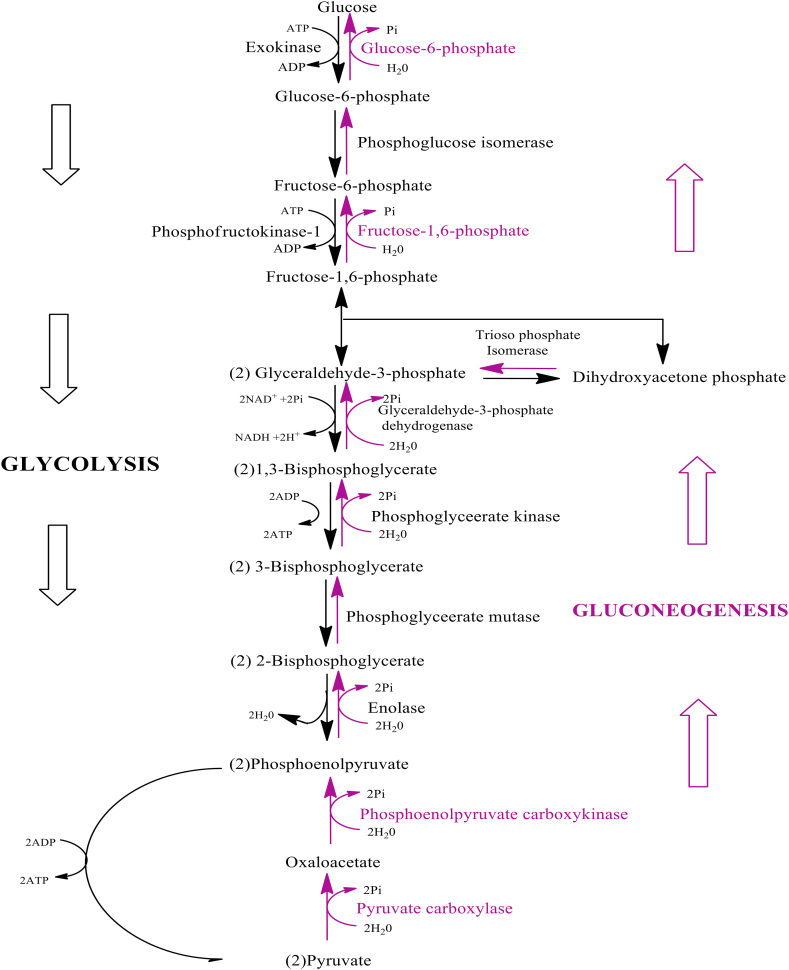

6.5. Inhibition of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose-6-phosphatase

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and glucose-6-phosphatase activities are repressed by aqueous and alcoholic concentrates of M. charantia [5]. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase catalyzes the hydrolysis of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate to fructose 6-phosphate (Figure 8) [133]. This reaction occurs in both gluconeogenesis and the Calvin cycle [134]. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase is a rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis and a key target for T2DM treatment due to the well-known involvement of abnormal endogenous glucose production in the disease's hyperglycemia [135]. Inhibition of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate has been proposed as a potential treatment for T2DM [136, 137]. Gluconeogenesis is a major contributor to surfeit glucose in this disease. Reducing its excess would help alleviate the pathology linked to elevated glucose concentrations in the blood and tissues. Inhibiting fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase only affect gluconeogenesis but not glycolysis [138, 139, 140, 141].

Figure 8.

Gluconeogenesis and glycolysis pathway. M. charantia suppresses the activities of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and glucose-6-phosphatase.

Glucose-6-phosphatase (also known as G-6-Pase), which is primarily found in the liver [142], catalyzes the final stage for both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis by changing glucose-6- phosphate to inorganic phosphate and glucose (Figure 8) [143, 144], making it an important regulator of blood glucose homeostasis [145]. The enzyme activity is several times higher in diabetic animals and, most likely, in diabetic humans, implying that it may be involved in the increased hepatic glucose production seen in T2DM [146]. Further, in the diabetic condition, the presence of both G-6-Pase (and glucokinase) in pancreatic -cells might result in higher glucose cycling, which can compromise glucose sensing and insulin secretion. Previous studies have shown an association of attenuated insulin production with higher glucose-6-phosphatase activity as well as glucose cycling in T2DM animal models [147, 148]. Therefore, M. charantia – a compound that inhibits the glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme complex – could be maximized in the treatment of T2DM.

7. Future perspective

Approval of any therapeutic substance and its application in pharmaceutical industry for human use is subjected to the success of the substance in clinical trial studies. While M. charantia and its extracts are widely regarded traditionally as a potent anti-diabetic concoction, up to date, there is scarcity of clinical trial studies on the anti-diabetic effects of the plant [8]; hence, the global acceptance of this purported “potent” antidiabetic plant in the treatment of diabetes mellitus is retarded. Unfortunately, the currently approved antidiabetic therapy has not shown maximum success, therefore more clinical studies on the anti-diabetic effects of extract of M. charantia should be encouraged. In addition, attention needs to be paid to the toxicity of M. charantia extract. Many toxicological studies have demonstrated in years past that extracts of M. charantia could be toxic in several organs of the body at varying doses. More recently a study on the reproductive toxicity of the plant in zebrafish confirm that it is teratogenic and cardiotoxic at certain dose [149]. Also, Abdillah and colleagues reported in 2020 that the administration of ethanolic extract of M. charantia for 28 consecutive days could have a toxic effect the liver and the kidney [150]. These reported toxic effects on vital organs of the body needs to be further elucidated so that a safe dose can be recommended for use [151].

8. Conclusion

The forgoing shows that M. charantia is a promising antidiabetic plant and could be of great use in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Being, a phyto-substance, it is easily accessible and relatively cheap; hence, studies should be focused on the development of the plant into a widely acceptable anti-diabetic therapy, especially with a high level of global mortality accorded to diabetes mellitus amidst various anti-diabetic drugs coupled with the outrageous increase in the number of diabetic patients is foreseen.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Cefalu W.T., et al. Efficacy of dietary supplementation with botanicals on carbohydrate metabolism in humans. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. - Drug Targets. 2008;8(2):78–81. doi: 10.2174/187153008784534376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cousens, G. There Is a Cure for Diabetes: the Tree of Life 21-day+ Program. 2007: North Atlantic Books.

- 3.Joseph B., Jini D. Antidiabetic effects of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) and its medicinal potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013;3(2):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehigie A.F., E.L., Olanlokun J.O., Oyelere S.F., Oyebode T.O., Olorunsogo O.O. Inhibitory effect of the methanol leaf extract of Momordica charantia on liver mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Eur. J. Biomed. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2019;6(8):73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph B., Jini D. Antidiabetic effects of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) and its medicinal potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013;3(2):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeed, M.K., et al., UTRITIO AL A ALYSIS ADA TIOXIDA T ACTIVITY OF BITTER GOURD (MOMORDICA CHARA TIA) FROM PAKISTA.

- 7.Budrat P., Shotipruk A. Extraction of phenolic compounds from fruits of bitter melon (Momordica charantia) with subcritical water extraction and antioxidant activities of these extracts. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2008;35(1):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z., et al. The effect of Momordica charantia in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: a review. Evidence-based Compl. Altern. Med. 2021;2021:3796265. doi: 10.1155/2021/3796265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kar A., Choudhary B., Bandyopadhyay N. Comparative evaluation of hypoglycaemic activity of some Indian medicinal plants in alloxan diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pari L., et al. Antihyperglycaemic effect of Diamed, a herbal formulation, in experimental diabetes in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001;53(8):1139–1143. doi: 10.1211/0022357011776397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed I., et al. Hypotriglyceridemic and hypocholesterolemic effects of anti-diabetic Momordica charantia (karela) fruit extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2001;51(3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover J., Rathi S., Vats V. 2002. Amelioration of Experimental Diabetic Neuropathy and Gastropathy in Rats Following Oral Administration of Plant (Eugenia Jambolana, Mucurna Pruriens and Tinospora Cordifolia) Extracts. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura T., et al. Hypoglycemic activity of the fruit of the Momordica charantia in type 2 diabetic mice. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2001;47(5):340–344. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.47.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivers N.M., et al. Diabetes Canada 2018 clinical practice guidelines: key messages for family physicians caring for patients living with type 2 diabetes. Can. Fam. Physician. 2019;65(1):14–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Röder P.V., et al. Pancreatic regulation of glucose homeostasis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016;48(3):e219. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piero M., et al. Diabetes mellitus-a devastating metabolic disorder. Asian J. Biomed. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2015;5(40):1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Virani S.S., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kar A., Choudhary B.K., Bandyopadhyay N.G. Comparative evaluation of hypoglycaemic activity of some Indian medicinal plants in alloxan diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84(1):105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathi S., Grover J., Vats V. The effect of Momordica charantia and Mucuna pruriens in experimental diabetes and their effect on key metabolic enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Phytother Res. 2002;16(3):236–243. doi: 10.1002/ptr.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rathi S., et al. Prevention of experimental diabetic cataract by Indian Ayurvedic plant extracts. Phytother Res.: Int. J. Dev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Evaluat. Nat. Prod. Derivat. 2002;16(8):774–777. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srivastava Y., et al. Antidiabetic and adaptogenic properties of Momordica charantia extract: an experimental and clinical evaluation. Phytother Res. 1993;7(4):285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vikrant V., et al. Treatment with extracts of Momordica charantia and Eugenia jambolana prevents hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in fructose fed rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahwish, et al. Bitter melon (momordica charantia L.) fruit bioactives charantin and vicine potential for diabetes prophylaxis and treatment. Plants (Basel) 2021;10(4) doi: 10.3390/plants10040730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welihinda J., et al. Effect of Momordica charantia on the glucose tolerance in maturity onset diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17(3):277–282. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karale P.A., Dhawale S., Karale M. Pharmacognosy-Medicinal Plants. IntechOpen; 2021. Phytochemical profile and antiobesity potential of momordica charantia Linn. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehi B., et al. Phytosterols: from preclinical evidence to potential clinical applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;11:1819. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.599959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabral C.E., Klein M. Phytosterols in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017;109(5):475–482. doi: 10.5935/abc.20170158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahzad N., et al. Phytosterols as a natural anticancer agent: current status and future perspective. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;88:786–794. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasserman A.M. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. Fam. Physician. 2011;84(11):1245–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi J., et al. Inhibition of cholesterol transport in an intestine cell model by pine-derived phytosterols. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2016;200:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Y., et al. Oxyphytosterols as active ingredients in wheat bran suppress human colon cancer cell growth: identification, chemical synthesis, and biological evaluation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63(8):2264–2276. doi: 10.1021/jf506361r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uddin M.S., et al. Phytosterols and their extraction from various plant matrices using supercritical carbon dioxide: a review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015;95(7):1385–1394. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramprasath V.R., Awad A.B. Role of phytosterols in cancer prevention and treatment. J. AOAC Int. 2015;98(3):735–738. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.SGERamprasath. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muronga M., et al. Three selected edible crops of the genus momordica as potential sources of phytochemicals: biochemical, nutritional, and medicinal values. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:625546. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.625546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshime L.T., et al. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) seed oil as a naturally rich source of bioactive compounds for nutraceutical purposes. Nutrire. 2016;41(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen A., et al. Analysis of IR, NMR and antimicrobial activity of β-sitosterol isolated from Momordica charantia. Sci. Secure J. Biotechnol. 2012;1(1):9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perera W.H., et al. Anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic properties and in silico modeling of cucurbitane-type triterpene glycosides from fruits of an Indian cultivar of momordica charantia L. Molecules. 2021;(4):26. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Oliveira M.S., et al. Phytochemical profile and biological activities of Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae): a review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2018;17(27):829–846. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragasa C.Y., et al. Hypoglycemic effects of tea extracts and sterols from Momordica charantia. J. Nat. Remedies. 2011;11:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villarreal-La Torre V.E., et al. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Momordica Charantia: a review. Phcog. J. 2020;12(1) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perveen S., Al-Taweel A. BoD–Books on Demand; 2018. Terpenes and Terpenoids. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu M., et al. Terpenoids and their biological activities from cinnamomum: a review. J. Chem. 2020;2020:5097542. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang W., et al. Advances in pharmacological activities of terpenoids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020;15(3) 1934578X20903555. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuan N.Q., et al. Inhibition of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by cucurbitanes from momordica charantia. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80(7):2018–2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weng J.-R., et al. Cucurbitane triterpenoid from Momordica charantia induces apoptosis and autophagy in breast cancer cells, in part, through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activation. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/935675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X., et al. Structures of new triterpenoids and cytotoxicity activities of the isolated major compounds from the fruit of Momordica charantia L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(15):3927–3933. doi: 10.1021/jf204208y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsiao P.-C., et al. Antiproliferative and hypoglycemic cucurbitane-type glycosides from the fruits of Momordica charantia. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61(12):2979–2986. doi: 10.1021/jf3041116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu C., et al. Wild bitter melon (Momordica charantia Linn. var. abbreviata Ser.) extract and its bioactive components suppress Propionibacterium acnes-induced inflammation. Food Chem. 2012;135(3):976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karale P., Dhawale S., Karale M. Antiobesity potential and complex phytochemistry of momordica charantia Linn. With promising molecular targets. Indian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2020;82(4):548–561. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma L., et al. Two new bidesmoside triterpenoid saponins from the seeds of Momordica charantia L. Molecules. 2014;19(2):2238–2246. doi: 10.3390/molecules19022238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liaw C.-C., et al. 5β, 19-epoxycucurbitane triterpenoids from Momordica charantia and their anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activity. Planta Med. 2015;81(1):62–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao G.-T., et al. Cucurbitane-type triterpenoids from the stems and leaves of Momordica charantia. Fitoterapia. 2014;95:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood M.H., et al. Comparative adsorption of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids at the iron oxide/oil interface. Langmuir. 2016;32(2):534–540. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b04435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campen S., et al. In situ study of model organic friction modifiers using liquid cell AFM; saturated and mono-unsaturated carboxylic acids. Tribol. Lett. 2015;57(2):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Delgado-Lista J., et al. Long chain omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. J. Nutr. 2012;107(S2):S201–S213. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alva-Murillo N., Ochoa-Zarzosa A., López-Meza J.E. Short chain fatty acids (propionic and hexanoic) decrease Staphylococcus aureus internalization into bovine mammary epithelial cells and modulate antimicrobial peptide expression. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;155(2-4):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urbanek A., et al. Composition and antimicrobial activity of fatty acids detected in the hygroscopic secretion collected from the secretory setae of larvae of the biting midge Forcipomyia nigra (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) J. Insect Physiol. 2012;58(9):1265–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarkar S., Pranava M., Marita A.R. Demonstration of the hypoglycemic action of Momordica charantia in a validated animal model of diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 1996;33(1):1–4. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmad Z., et al. In vitro anti-diabetic activities and chemical analysis of polypeptide-k and oil isolated from seeds of Momordica charantia (bitter gourd) Molecules. 2012;17(8):9631–9640. doi: 10.3390/molecules17089631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.GÖLÜKÇÜ M., et al. Some physical and chemical properties of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) seed and fatty acid composition of seed oil. Derim. 2014;31(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mukherjee A., Barik A.J.A.J. Long-chain free fatty acids from Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng flowers as allelochemical influencing the attraction of Aulacophora foveicollis Lucas (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Allelopathy J. 2014;33(2):255. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saini R.K., et al. Fatty acid and carotenoid composition of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) seed arils: a potentially valuable source of lycopene. J. Food Meas. Char. 2017;11(3):1266–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sarkar N., Barik A. Free fatty acids from Momordica charantia L. flower surface waxes influencing attraction of Epilachna dodecastigma (Wied.)(Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Int. J. Pest Manag. 2015;61(1):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarkar N., Mukherjee A., Barik A.J.A.-P.I. Olfactory responses of Epilachna dodecastigma (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) to long-chain fatty acids from Momordica charantia leaves. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2013;7(3):339–348. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kafkas N.E., et al. Advanced analytical methods for phenolics in fruits. J. Food Qual. 2018;2018:3836064. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roby M.H.H., et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, total phenols and phenolic compounds in thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.), sage (Salvia officinalis L.), and marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) extracts. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013;43:827–831. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alves M.J., et al. Antimicrobial activity of phenolic compounds identified in wild mushrooms, SAR analysis and docking studies. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;115(2):346–357. doi: 10.1111/jam.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu Q.-F., et al. Antiviral phenolic compounds from Arundina gramnifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76(2):292–296. doi: 10.1021/np300727f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghasemzadeh A., Jaafar H.Z. Profiling of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant and anticancer activities in pandan (Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.) extracts from different locations of Malaysia. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2013;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Snafi A.E. Phenolics and flavonoids contents of medicinal plants, as natural ingredients for many therapeutic purposes-A review. IOSR J. Pharm. 2020;10(7):42–81. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shodehinde S.A., et al. Phenolic composition and evaluation of methanol and aqueous extracts of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L) leaves on angiotensin-I-converting enzyme and some pro-oxidant-induced lipid peroxidation in vitro. J. Evid.-Based Compl. Altern. Med. 2016;21(4):NP67–NP76. doi: 10.1177/2156587216636505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi J.S., et al. Roasting enhances antioxidant effect of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) increasing in flavan-3-ol and phenolic acid contents. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2012;21(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenny O., et al. Antioxidant properties and quantitative UPLC-MS analysis of phenolic compounds from extracts of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) seeds and bitter melon (Momordica charantia) fruit. Food Chem. 2013;141(4):4295–4302. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee S.H., et al. Phenolic acid, carotenoid composition, and antioxidant activity of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) at different maturation stages. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20(sup3):S3078–S3087. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paul A., Raychaudhuri S.S. Medicinal uses and molecular identification of two Momordica charantia varieties-a review. Electr. J. Biol. 2010;6(2):43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bakare R., Magbagbeola O., Okunowo O.J. Nutritional and chemical evaluation of Momordica charantia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010;4(21):2189–2193. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu F., et al. The plant ribosome-inactivating proteins play important roles in defense against pathogens and insect pest attacks. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:146. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Puri M., et al. Ribosome inactivating proteins (RIPs) from Momordica charantia for anti viral therapy. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009;9(9):1080–1094. doi: 10.2174/156652409789839071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meng Y., et al. Preparation of an antitumor and antivirus agent: chemical modification of α-MMC and MAP30 from Momordica Charantia L. with covalent conjugation of polyethyelene glycol. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012;7:3133. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fang E.F., et al. The MAP30 protein from bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) seeds promotes apoptosis in liver cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2012;324(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jabeen U., Khanum A. Isolation and characterization of potential food preservative peptide from Momordica charantia L. Arab. J. Chem. 2017;10:S3982–S3989. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saeed F., et al. Bitter melon (Momordica charantia): a natural healthy vegetable. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018;21(1):1270–1290. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jia S., et al. Recent advances in Momordica charantia: functional components and biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(12):2555. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuan X., Gu X., Tang J. Purification and characterisation of a hypoglycemic peptide from Momordica Charantia L. Var. abbreviata Ser. Food Chem. 2008;111(2):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park S.H., et al. Antioxidative and antimelanogenesis effect of momordica charantia methanol extract. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2019;2019:5091534. doi: 10.1155/2019/5091534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sallau A., et al. In vitro effect of terpenoids-rich extract of Momordica charantia on alpha glucosidase activity. Vitae. 2018;25(3):148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soundararajan R., et al. Antileukemic potential of Momordica charantia seed extracts on human myeloid leukemic HL60 cells. Evid. base Compl. Alternative Med. 2012:2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/732404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chakraborty S., et al. Structural and interactional homology of clinically potential trypsin inhibitors: molecular modelling of cucurbitaceae family peptides using the X-ray structure of MCTI-II. Protein Eng. 2000;13(8):551–555. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.8.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jia S., et al. Recent advances in momordica charantia: functional components and biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(12) doi: 10.3390/ijms18122555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mahatmanto T.J.P.S. Review seed biopharmaceutical cyclic peptides: from discovery to applications. Pept. Sci. 2015;104(6):804–814. doi: 10.1002/bip.22741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang B., et al. Purification and characterisation of an antifungal protein, MCha-Pr, from the intercellular fluid of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) leaves. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015;107:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deng Y., et al. Comparison of the content, antioxidant activity, andα-glucosidase inhibitory effect of polysaccharides from Momordicacharantia L. species. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2014;30:102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dong Y., et al. Studies on the isolation, purification and composition of Momordica charantia L. polysaccharide. Food Sci. (N. Y.) 2005;11:23. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sărăndan H., et al. The hypoglicemic effect of Momordica charantia Linn in normal and alloxan induced diabetic rabbits. Sci. Pap.: Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2010;43(1):516–518. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Akhtar N., et al. Pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical evaluation of extracts from different plant parts of indigenous origin for their hypoglycemic responses in rabbits. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2011;68(6):919–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abdollah M., et al. The effects of Momordica charantia on the liver in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in neonatal rats. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9(31):5004–5012. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Raish M. Momordica charantia polysaccharides ameliorate oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, inflammation, and apoptosis during myocardial infarction by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;97:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kang J., et al. Effects of Momordica charantia polysaccharide on in vitro ruminal fermentation and cellulolytic bacteria. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2017;16(2):226–233. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Garau C., et al. Vol. 11. 2003. pp. 46–55. (Beneficial Effect and Mechanism of Action of Momordica Charantia in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: a Mini Review). [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bhushan M.S., et al. An analytical review of plants for anti diabetic activity with their phytoconstituent & mechanism of action. Int. J. Pharma Sci. Res. 2010;1(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jeong J.-H., et al. Effect of bitter melon (Momordica Charantia) on anti-diabetic activity in C57BLI/6J db/db mice. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2008;48(3):327–336. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nerurkar P.V., et al. Momordica charantia (bitter melon) inhibits primary human adipocyte differentiation by modulating adipogenic genes. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2010;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Manoharan G., Singh J. The anti-diabetic effects of momordica charantia: active constituents and modes of actions. Open Med. Chem. J. 2011;5(6):70–77. doi: 10.2174/1874104501105010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shibib B.A., Khan L.A., Rahman R.J.B.J. Hypoglycaemic activity of Coccinia indica and Momordica charantia in diabetic rats: depression of the hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes glucose-6-phosphatase and fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase and elevation of both liver and red-cell shunt enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1993;292(1):267–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2920267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gadang V., et al. Dietary bitter melon seed increases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ gene expression in adipose tissue, down-regulates the nuclear factor-κB expression, and alleviates the symptoms associated with metabolic syndrome. J. Med. Food. 2011;14(1-2):86–93. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen C., et al. Human beta cell mass and function in diabetes: recent advances in knowledge and technologies to understand disease pathogenesis. Mol. Metabol. 2017;6(9):943–957. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mechelke T., et al. Interleukin-1β induces tissue factor expression in A549 cells via EGFR-dependent and-independent mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(12):6606. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Briaud I., et al. Differential activation mechanisms of Erk-1/2 and p70S6K by glucose in pancreatic#2-cells. Diabetes. 2003;52:974–983. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tournier C., et al. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science. 2000;288(5467):870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mandrup-Poulsen T. Beta-cell apoptosis: stimuli and signaling. Diabetes. 2001;50(Suppl 1):S58–63. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim W.H., et al. Synergistic activation of JNK/SAPK induced by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma: apoptosis of pancreatic beta-cells via the p53 and ROS pathway. Cell. Signal. 2005;17(12):1516–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu T., et al. Signal transduct. Target. Ther. 2017;2:e17023. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim K., Kim H.Y. Bitter melon (Momordica charantia) extract suppresses cytokineinduced activation of MAPK and NF-κB in pancreatic β-Cells. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011;20(2):531–535. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chuang C.Y., et al. Fractionation and identification of 9c, 11t, 13t-conjugated linolenic acid as an activator of PPARalpha in bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) J. Biomed. Sci. 2006;13(6):763–772. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Michalik L., et al. International union of pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58(4):726–741. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ding Y., Yang K.D., Yang Q. The role of PPARδ signaling in the cardiovascular system. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2014;121:451–473. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800101-1.00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kersten S. Integrated physiology and systems biology of PPARα. Mol. Metabol. 2014;3(4):354–371. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tan N.S., et al. Transcriptional control of physiological and pathological processes by the nuclear receptor PPARβ/δ. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016;64:98–122. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Vázquez-Carrera M. Unraveling the effects of PPARβ/δ on insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2016;27(5):319–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hanhineva K., et al. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010;11(4):1365–1402. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rigano D., Sirignano C., Taglialatela-Scafati O. The potential of natural products for targeting PPARα. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2017;7(4):427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bougarne N., et al. Molecular actions of PPAR α in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2018;39(5):760–802. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Corrales P., Vidal-Puig A., Medina-Gómez G. PPARs and metabolic disorders associated with challenged adipose tissue plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(7):2124. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Votey S.R., Peters A. Diabetes mellitus, type 2-A review. J.R.D. 2005;5:2006. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jeevathayaparan S., Tennekoon K.H., Karunanayake E. A comparative study of the oral hypoglycaemic effect of Momordica charantia fruit juice and tolbutamine in streptozotocin induced graded severity diabetes in rat. Int. J. Diabetes. 1995;3:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ahmed I., et al. Beneficial effects and mechanism of action of Momordica charantia juice in the treatment of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus in rat. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;261(1):63–70. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000028738.95518.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Singh N., Gupta M., Sirohi P. Effects of alcoholic extract of Momordica charantia (Linn.) whole fruit powder on the pancreatic islets of alloxan diabetic albino rats. J. Environ. Biol. 2008;29(1):101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Anilakumar K.R., et al. Nutritional, pharmacological and medicinal properties of Momordica charantia. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015;4(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chung M.-Y., Choi H.-K., Hwang J.-T. AMPK activity: a primary target for diabetes prevention with therapeutic phytochemicals. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4050. doi: 10.3390/nu13114050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhang X., et al. Unraveling the regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2019:802. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Foretz M., Even P.C., Viollet B. AMPK activation reduces hepatic lipid content by increasing fat oxidation in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(9):2826. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ruderman N.B., Saha A.K., Kraegen E.W. Minireview: malonyl CoA, AMP-activated protein kinase, and adiposity. Endocrinology. 2003;144(12):5166–5171. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hines J.K., et al. Structure of inhibited fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase from Escherichia coli: distinct allosteric inhibition sites for AMP and glucose 6-phosphate and the characterization of a gluconeogenic switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(34):24697–24706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Timson D.J. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase: getting the message across. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39(3) doi: 10.1042/BSR20190124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hatting M., et al. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018;1411(1):21–35. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kaur R., Dahiya L., Kumar M. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase inhibitors: a new valid approach for management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;141:473–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.van Poelje P.D., Potter S.C., Erion M.D. Fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase inhibitors for reducing excessive endogenous glucose production in type 2 diabetes. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2011;(203):279–301. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17214-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Dang Q., et al. Discovery of potent and specific fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase inhibitors and a series of orally-bioavailable phosphoramidase-sensitive prodrugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129(50):15491–15502. doi: 10.1021/ja074871l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dang Q., et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase inhibitors. 1. Purine phosphonic acids as novel AMP mimics. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52(9):2880–2898. doi: 10.1021/jm900078f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dang Q., et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase Inhibitors. 2. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of a series of phosphonic acid containing benzimidazoles that function as 5'-adenosinemonophosphate (AMP) mimics. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53(1):441–451. doi: 10.1021/jm901420x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dang Q., et al. Discovery of a series of phosphonic acid-containing thiazoles and orally bioavailable diamide prodrugs that lower glucose in diabetic animals through inhibition of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54(1):153–165. doi: 10.1021/jm101035x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Nordlie R.C., Foster J.D. A retrospective review of the roles of multifunctional glucose-6-phosphatase in blood glucose homeostasis: genesis of the tuning/retuning hypothesis. Life Sci. 2010;87(11-12):339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Burchell A., Waddell I.D. The molecular basis of the hepatic microsomal glucose-6-phosphatase system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1092(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(91)90146-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mithieux G., et al. Glucose-6-phosphatase mRNA and activity are increased to the same extent in kidney and liver of diabetic rats. Diabetes. 1996;45(7):891–896. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Froissart R., et al. Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Westergaard N., Madsen P. Glucose-6-phosphatase inhibitors for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2001;11(9):1429–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Khan A., et al. Glucose cycling is markedly enhanced in pancreatic islets of obese hyperglycemic mice. Endocrinology. 1990;126(5):2413–2416. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-5-2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Khan A., Hong-Lie C., Landau B.R. Glucose-6-phosphatase activity in islets from ob/ob and lean mice and the effect of dexamethasone. Endocrinology. 1995;136(5):1934–1938. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Khan M.F., et al. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) possess developmental toxicity as revealed by screening the seeds and fruit extracts in zebrafish embryos. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2019;19(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2599-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Abdillah S., et al. Acute and subchronic toxicity of momordica charantia L fruits ethanolic extract in liver and kidney. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020;11(12):2249–2255. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Grandjean P. Paracelsus revisited: the dose concept in a complex world. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016;119(2):126–132. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.