Abstract

Human polymorphisms may contribute to SARS-CoV-2 infection susceptibility and COVID-19 outcomes (asymptomatic presentation, severe COVID-19, death). We aimed to evaluate the association of IFITM3, FURIN, ACE1, and TNF-α genetic variants with both phenotypes using meta-analysis. The bibliographic search was conducted on the PubMed and Scielo databases covering reports published until February 8, 2022. Two independent researchers examined the study quality using the Q-Genie tool. Using the Mantel–Haenszel weighted means method, odds ratios were combined under both fixed- and random-effect models. Twenty-seven studies were included in the systematic review (five with IFITM3, two with Furin, three with TNF-α, and 17 with ACE1) and 22 in the meta-analysis (IFITM3 n = 3, TNF-α, and ACE1 n = 16). Meta-analysis indicated no association of 1) ACE1 rs4646994 and susceptibility, 2) ACE1 rs4646994 and asymptomatic COVID-19, 3) IFITM3 rs12252 and ICU hospitalization, and 4) TNF-α rs1800629 and death. On the other hand, significant results were found for ACE1 rs4646994 association with COVID-19 severity (11 studies, 692 severe cases, and 1,433 nonsevere controls). The ACE1 rs4646994 deletion allele showed increased odds for severe manifestation (OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.26–1.66). The homozygous deletion was a risk factor (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.22–1.83), while homozygous insertion presented a protective effect (OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.45–0.74). Further reports are needed to verify this effect on populations with different ethnic backgrounds.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prosperodisplay_record.php?ID=CRD42021268578, identifier CRD42021268578

Keywords: polymorphism, genetic association study, candidate genes, transposable elements, biomarkers, host genetics

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) clinical presentation is heterogeneous, ranging from entirely asymptomatic up to severe cases and death. Another level of heterogeneity is observed regarding persistent symptoms: one study has estimated that the median proportion of individuals who experienced at least one persistent symptom was 73% (Nasserie et al., 2021). Uncovering biomarkers linking patients with distinct prognosis subgroups would be beneficial. Different strategies have been employed to uncover molecular markers predicting odds for better prognosis and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection susceptibility. Proteins, lipids, and metabolites have already been examined (Praissman and Wells, 2021; Samprathi and Jayashree, 2021). Genetic variability has been shown to be a valuable source for biomarker research. COVID-19 prognosis and infection susceptibility are multifactorial traits determined by the complex interaction of environmental factors and multiple genes. Thus, significant single-gene results may lead to substantial predictors such as the C–C chemokine receptor type five (CCR5) gene association with HIV susceptibility and prognosis (Liu et al., 2012), or ABO blood type and dengue severity (Hashan et al., 2021).

Genetic association studies can be designed within prespecified genes of interest (candidate gene approach) or with a broader strategy characterizing diversity across large genomic areas (genome-wide association studies, whole exome and genome sequencing). Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), human leukocyte antigen (HLA), interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), FURIN, and angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE1) were the most studied genes using the candidate gene approach in 2020 (Araújo et al., 2021). They all present strong biological plausibility since they act on viral cell entry or human immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

Findings from single association studies must always be considered carefully because of the likelihood of producing spurious outcomes (Sullivan, 2007). Replication is essential before considering using genetic markers in the clinical setting. Although that has been proved hard, inconsistency frequently can be attributed to shortfalls in study design, implementation, and interpretation, with inadequately powered sample groups being of significant concern (Hattersley and McCarthy, 2005). A systematic meta-analytic approach may support estimating population-wide effects of genetic risk factors in human diseases (Ioannidis et al., 2001). The PROSPERO (Moher et al., 2014) database, indicating protocols for systematic reviews, has already been presented for HLA (CRD42021251670) (Deb et al., 2022), ACE2, and TMPRSS2 (CRD42021229963) contribution with COVID-19 outcomes. Therefore, we focused our systematic review on IFITM3, FURIN, ACE1, and TNF-α genetic variants and their association with COVID-19 susceptibility and prognosis to reduce unnecessary duplication.

IFITM3 (MIM 605579; 11p15.5) is a protein-coding gene that disturbs cell entry by inhibiting viral fusion with cholesterol-depleted endosomes (Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al., 2013); a mechanism also described during SARS-CoV-2 infection (Prelli Bozzo et al., 2021). The IFITM3 rs12252 polymorphism has been associated with influenza severity (Prabhu et al., 2018). The TNF (MIM 191160; 6p21.33) gene encodes a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine. Although TNF-α is not as relevant as interleukin-6 on the cytokine storm presented in severe COVID-19 patients (Karki and Kanneganti, 2021), anti-TNF-α drug repositioning for COVID-19 has been proposed (Stebbing et al., 2020). FURIN is coded by the FURIN (MIM 136950; 15q26.1) gene. It regulates constitutive exocytic and endocytic pathways and has a central role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission (Peacock et al., 2021). The ACE1 (MIM 106180; 17q23.3) gene produces a protein related to blood pressure regulation and electrolyte balance, and ACE1/ACE2 balance has been suggested to play a pivotal role in the pathobiology and treatment of COVID-19 (Sriram and Insel, 2020). The ACE1 rs4646994 variant is a 287-bp Alu repeat insertion/deletion (indel) on intron 16 known to alter ACE-1 levels and influence several clinical traits (Castellon and Hamdi, 2007). Here, we present the result of a systematic review and, whenever possible, a meta-analysis of IFITM3, FURIN, ACE1, and TNF-α genetic association with susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity.

Materials and Methods

The systematic review protocol was submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42021268578). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) was adopted as a guideline for reporting this systematic review (Page et al., 2021). The study selection was carried out in three phases: identification, screening, and eligibility. Search on the PubMed and Scielo databases led to article identification. The PECO question for prognosis was Participants (P) = subjects with COVID-19, Exposition (E) = minor alleles, Control (C) = major alleles of genetic variants, and Outcomes (O) = COVID-19 severity (asymptomatic or severe presentation); while the PECO question for susceptibility was P = overall population, E = minor alleles, C = major alleles of genetic variants, and Outcomes (O) = COVID-19 positive diagnosis. The bibliographic search included all studies published until February 8, 2022, with no language restriction, using the search arguments listed in Supplementary Material SI. Two independent researchers conducted article screening. Inclusion criteria were primary articles covering genetic association of COVID-19 susceptibility or prognosis with IFITM3, FURIN, ACE1, and TNF-α variants, comprising four separate searches. Exclusion criteria were review articles or primary articles evaluating the association of COVID-19 susceptibility or prognosis with other genes.

We assessed study quality using the Q-Genie tool (Sohani et al., 2016) performed by two independent researchers. This instrument contains 11 questions to be marked on a seven-point Likert scale examining several aspects of a genetic association study: scientific basis for the development of the research question, ascertainment of comparison groups (e.g., cases and controls), technical and nontechnical classification of tested genetic variants (e.g., genotyping call rates, blinded experiments), classification of the outcome (e.g., sampling strategy, definition criteria), discussion of sources of bias, appropriateness of sample size, description of planned statistical analyses, statistical methods applied, test of assumptions in the genetic studies (e.g., Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium), and appropriate interpretation of the results. Proposed cutoffs for understanding are ≤35 poor, > 35 moderate, and ≥45 good quality, with the total score ranging from 7 to 77 points.

Meta-analysis was conducted whenever three or more studies were included for the same polymorphism and outcome. We carried out single meta-analyses for each polymorphism considering allelic and genotypic effects (under both allele recessive model assumptions). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the chi-square test. We used the metabin function coded on meta package in R (version 4.1.0) (R Core Team, 2014) to estimate overall odds ratios (ORs) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Original ORs were combined using the Mantel–Haenszel weighted means method under both fixed- and random-effect models. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

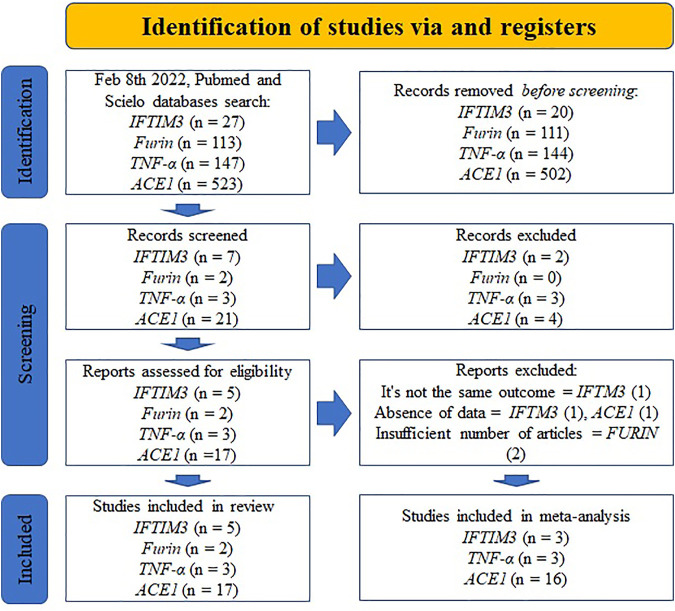

Twenty-seven studies were included in the systematic review: five with IFITM3 (Zhang et al., 2020; Alghamdi et al., 2021; Cuesta-Llavona et al., 2021; Gómez et al., 2021; Schönfelder et al., 2021), two with Furin (Latini et al., 2020; Torre-Fuentes et al., 2021), three with TNF-α (Saleh et al., 2020; Fishchuk et al., 2021; Heidari Nia et al., 2021), and 17 with ACE1 (Gómez et al., 2020; Aladag et al., 2021; Annunziata et al., 2021; Cafiero et al., 2021; Gunal et al., 2021; Hubacek et al., 2021; Karakaş Çelik et al., 2021; Kouhpayeh et al., 2021; Mir et al., 2021; Möhlendick et al., 2021; Saad et al., 2021; Verma et al., 2021; Akbari et al., 2022; Gong et al., 2022; Mahmood et al., 2022; Papadopoulou et al., 2022). (Figure 1). Inconsistencies in reported frequencies were found in two studies (Gómez et al., 2021; Karakaş Çelik et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1.

Study selection using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (16).

All manuscripts but one reached moderate or good quality scores in the Q-Genie analysis (Supplementary Material S1). Among the 11 questions, it is clear that all studies had the worst performance for questions number 5 and 10. While question 5 examines reported information regarding how genotyping was conducted (e.g., blinded experiments, batch effects), question 10 evaluated whether genetic relationships among subjects were tested, and sex and ethnicity were stated.

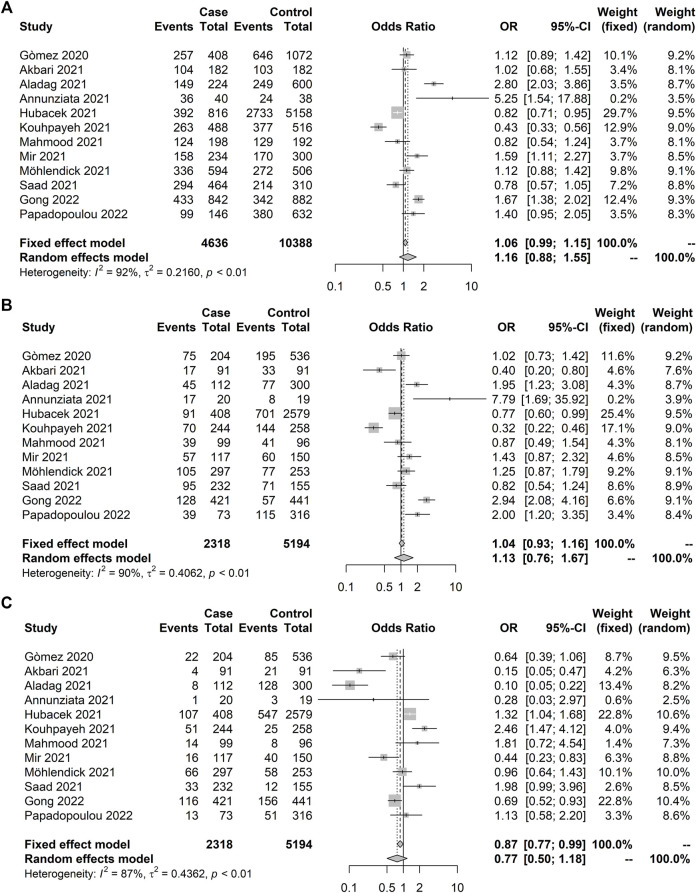

Five meta-analyses were carried out, including 22 studies evaluating three genes (IFITM3 n = 3, TNF-α n = 3, and ACE1 n = 16). Twelve studies, including 2,318 control subjects and 5,194 COVID-19 positives, evaluated the ACE1 rs4646994 association with COVID-19 susceptibility (Table 1). Significant heterogeneity was observed for all genetic models with no significant association under the random model (Figure 2). Similar findings were detected in the meta-analysis of the ACE1 rs4646994 variant with asymptomatic presentation (Table 2), indicating no significant effect pooled from three studies (Figure 3). We observed high heterogeneity in the sampling places and reported ethnic backgrounds.

TABLE 1.

Association studies of ACE1 rs4646994 (Alu 287 pb) with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) susceptibility included in the systematic review.

| Year | Author | Sample | Control | Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | Ethnic background | Size | Male n(%) | n | Criteria | n | Criteria | ||

| 2020 | Gòmez | — | Spain | Caucasian (Asturias) | 740 | 373 (0.50) | 536 | Healthy population | 204 | COVID-19 positive |

| 2021 | Akbari | 2020 | Iran | — | 182 | 105 (0.57) | 91 | Unaffected individuals without a history of exposure to COVID-19 cases | 91 | COVID-19 positive |

| Aladag | May/2020 | Turkey | — | 412 | — | 300 | General population | 112 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Annunziata | March–April/20 | Italy | Southern Italians | 39 | — | 19 | Healthy subjects | 20 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Hubacek | March–June/2020 | Czech Republic | — | 2,989 | −(0.54) | 2,579 | General population | 408 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Kouhpayeh | May–September/2020 | Iran | — | 520 | 276 (0.55) | 258 | Healthy subjects with negative PCR and clinical diagnostic criteria | 244 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Mahmood | October–December/2020 | Iraq | — | 195 | −(0.50) | 96 | Healthy subjects with negative serological test | 99 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Mir | September/2020–April/2021 | Saudi Arabia | — | 267 | 185 (0.69) | 150 | Healthy subjects | 117 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Möhlendick | March–September/2020 | Germany | — | 550 | 323 (0.59) | 253 | Patients with COVID-19 symptoms with negative PCR | 297 | COVID-19 positive | |

| Saad | — | Lebanon | Lebanese | 387 | 195 (0.50) | 155 | Participants with negative PCR | 232 | COVID-19 positive | |

| 2022 | Gong | January–March/2020 | China | — | 862 | — | 441 | Healthy subjects | 421 | COVID-19 positive |

| Papadopoulou | March–June/2020 | Greece | Caucasian (Greek) | 389 | — | 316 | Blood product donors and volunteer healthcare workers | 73 | COVID-19 positive | |

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot illustrating ACE1 rs4646994 (Alu 287 pb) association with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) susceptibility. No significant results were observed. Case and control definitions are presented in Table 1. (A) C allele association. (B) C recessive model. (C) T recessive model.

TABLE 2.

Association studies of ACE1 rs4646994 (Alu 287 pb) with COVID-19 prognosis included in the systematic review.

| Phenotype | Year | Author | Sample | Control | Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | Ethnic background | Size | Male n(%) | n | Criteria | n | Criteria | |||

| Asymptomatic × symptomatic | 2021 | Cafiero | — | Italy | — | 104 | 58 (0.56) | 50 | Asymptomatic | 54 | Symptomatic (x-ray imaging) |

| Hubacek | March–June/2020 | Czech Republic | — | 408 | −(0.55) | 163 | Asymptomatic | 245 | Symptomatic (no hospitalization) | ||

| Gunal | April–July/2020 | Turkey | — | 60 | — | 30 | Asymptomatic | 30 | Severe (RR ≥30/min; SpO2 ≤93%; PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg; mechanical ventilation or ICU) | ||

| Nonsevere × severe | 2020 | Gòmez | — | Spain | Caucasian (Asturias) | 204 | 125 (0.61) | 137 | Mild (hospitalized, nonsevere) | 67 | Severe (hospitalized, mechanical ventilation and/or ICU) |

| 2021 | Akbari | 2020 | Iran | — | 91 | 53 (0.58) | 54 | Hospitalized, non-ICU | 37 | Hospitalized, ICU | |

| Aladag | May/2020 | Turkey | — | 65 | - | 53 | Nonsevere | 12 | Severe (fever or suspected respiratory infection, plus one of the following: RR >30/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 ≤93%) | ||

| Çelik | — | Turkey | — | 154 | 78 (0.50) | 119 | Mild (outpatients) and moderate (hospitalized nonsevere) | 35 | Severe (RR ≥30/min; SpO2 ≤93%; PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg; mechanical ventilation or ICU) | ||

| Gunal | April–July/2020 | Turkey | — | 90 | - | 60 | Asymptomatic and mild | 30 | Severe (RR ≥30/min; SpO2 ≤93%; PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg; mechanical ventilation or ICU) | ||

| Kouhpayeh | May–September/2020 | Iran | — | 258 | 144 (0.56) | 106 | Nonsevere | 152 | Severe (fever or suspected respiratory infection, plus one of the following: RR >30/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 ≤93%) | ||

| Mahmood | October–December/2020 | Iraq | — | 99 | −(0.51) | 68 | Mild (with symptoms of pneumonia and no signs of severe pneumonia) | 31 | Severe (severe respiratory distress, RR ≥30 breaths/min or SpO2 ≤ 93%) | ||

| Möhlendick | March–September/2020 | Germany | — | 251 | 176 (0.59) | 207 | Mild and hospitalized (non-ICU) | 44 | Severe (hospitalized, mechanical ventilation and/or ICU) | ||

| Saad | - | Lebanon | Lebanese | 223 | 123 (0.55) | 162 | Mild and moderate | 61 | Severe (lung infiltrates on chest x-ray or CT scan and SpO2 <94% who required hospitalization with essential oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation) | ||

| Verma | August–September/2020 | India | India | 269 | 174 (0.65) | 149 | Mild (RR <24/min, SpO2 >94%) | 120 | Severe (pneumonia with RR > 30/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 ≤93%) | ||

| 2022 | Gong | January–March/2020 | China | — | 421 | — | 318 | Mild and moderate | 103 | Severe | |

| Papadopoulou | March–June/2020 | Greece | Caucasian (Greek) | 81 | 43 (0.53) | 29 | Mild and moderate (with symptoms of pneumonia and no signs of severe pneumonia) | 52 | Severe or critical (fever or suspected respiratory infection, plus one of the following: RR >30/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 ≤93%) | ||

| Alive × dead | 2021 | Mir | September/2020–April/2021 | Saudi Arabia | — | 117 | 85 (0.73) | 74 | Alive | 43 | Dead |

| Möhlendick | March–September/2020 | Germany | — | 297 | 176 (0.59) | 251 | Mild, hospitalized (non-ICU) and severe | 46 | Dead | ||

Note. RR, respiratory rate; ICU, intensive care unit; SpO2, oxygen saturation; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen pressure/fraction of inspired oxygen; CT, computerized tomography.

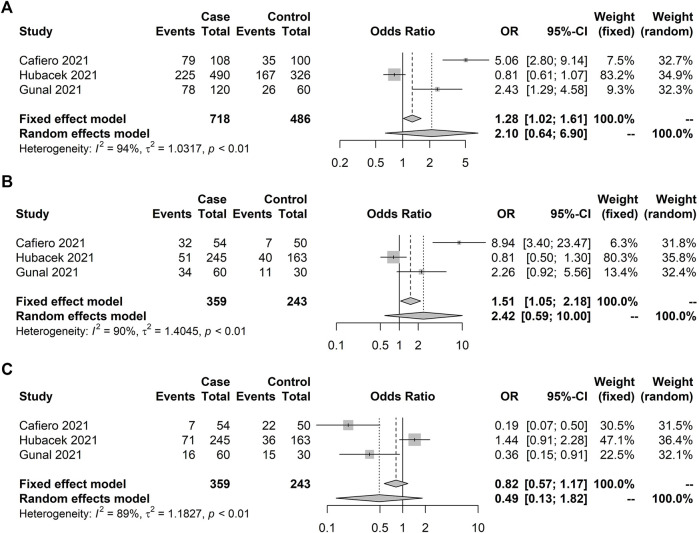

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot illustrating ACE1 rs4646994 (Alu 287 pb) association with symptom presence (asymptomatic × symptomatic). No significant allelic and genotypic effects were observed under the random model. Case and control definitions are presented in Table 2. (A) D-allele model. (B) D recessive model. (C) I recessive model.

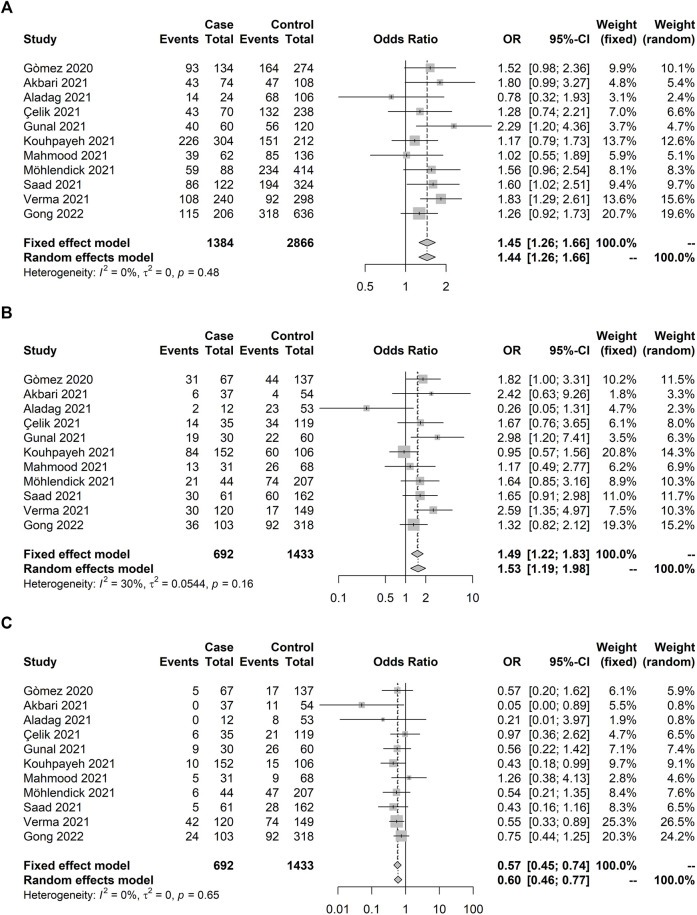

We were able to conduct a meta-analysis investigating whether ACE1 rs4646994 polymorphism could predict COVID-19 severity. Eleven studies were included reaching a total of 692 individuals with severe COVID-19 and 1,433 with nonsevere manifestation (Table 2). The allelic association was observed with increased odds for deletion (D) allele compared with I-allele (pooled OR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.26–1.66) (Figure 4A). Homozygous deletion (D/D) carriers showed 49% increased odds to present severe COVID-19 compared with heterozygous (D/I) and homozygous insertion allele (I/I) carriers combined (pooled OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.22–1.83) (Figure 4B). On the other hand, the I/I genotype was protective against severe COVID-19 (pooled OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.45–0.74) (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot illustrating ACE1 rs4646994 (Alu 287 pb) association with COVID-19 severity (severe × others). Significant allelic and genotypic effects were observed. Case and control definitions are presented in Table 2. (A) D-allele model. D-allele was associated with increased risk of COVID-19 severity. (B) D recessive model. D/D genotype carriers showed increased odds to manifest severe COVID-19 compared with D/I and I/I carriers combined (C) I recessive model. I/I genotype carriers showed decreased odds to present severe COVID-19 compared with D/I and D/D carriers combined.

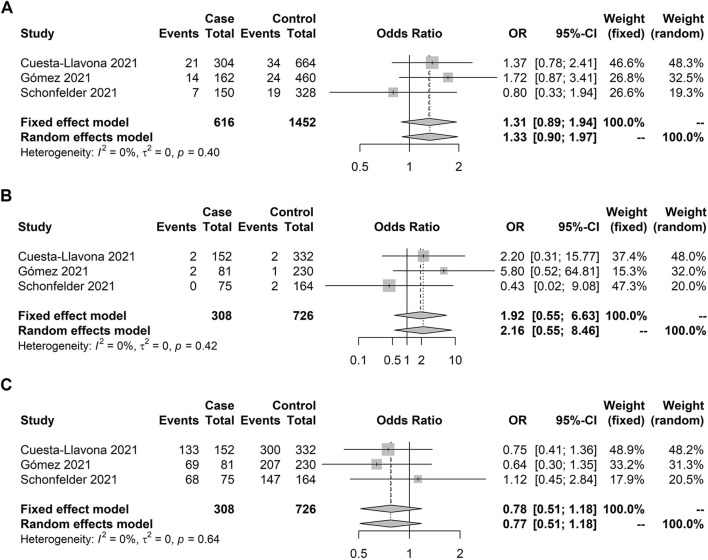

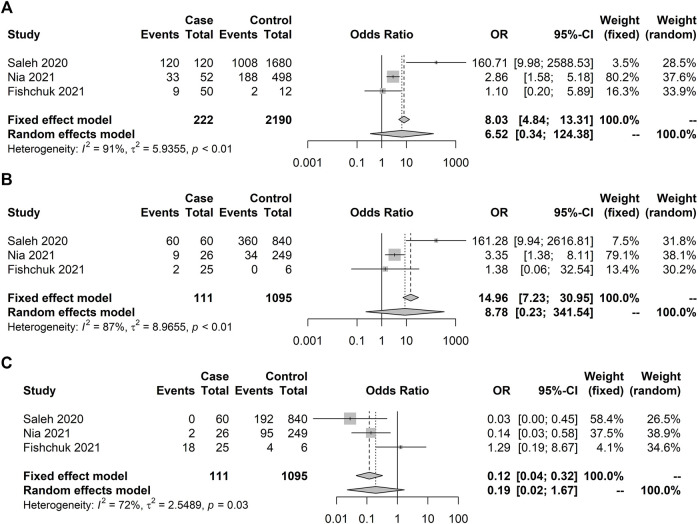

The IFITM3 rs12252 meta-analysis with severity included three studies totaling 308 individuals admitted to an intensive care unit and 726 who were not admitted (Table 3). No significant association was observed under any genetic model (Figure 5). Meta-analysis for other outcomes with the IFITM3 rs12252 could not be conducted. The TNF-α rs1800629 association with death was analyzed in three studies (Table 4), including 111 subjects who died and 1,095 survivors. No significant association was observed under the random-effect models (Figure 6). FURIN (Table 5) genetic variants had less than three studies; therefore, no meta-analyses were carried out.

TABLE 3.

Association studies of IFITM3 rs12252 with COVID-19 prognosis included in the systematic review.

| Phenotype | Year | Author | Sample | Control | Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | Ethnic background | Size | Male n(%) | n | Criteria | n | Criteria | |||

| Non-ICU × ICU | 2021 | Alghamdi | — | Saudi Arabia | Saudi | 376 | 112 (0.56) | 210 | Hospitalized, non-ICU | 166 | Hospitalized, ICU |

| 2021 | Cuesta-Llavona | March–December/2020 | Spain | Caucasian (Asturias) | 484 | 276 (0.57) | 332 | Hospitalized, non-ICU | 152 | Hospitalized, ICU | |

| 2021 | Gómez | March–August/2020 | Not informed | Caucasian (Asturias) | 311 | 174 (0.56) | 230 | Hospitalized, non-ICU | 81 | Hospitalized, ICU | |

| 2021 | Schonfelder | March–September/2020 | Germany | Caucasian | 239 | 141 (0.59) | 164 | Outpatients and hospitalized (non-ICU) | 75 | Hospitalized (ICU or mechanical ventilation) or dead | |

| Alive × dead | 2021 | Alghamdi | — | Saudi Arabia | Saudi | 861 | — | 784 | Alive | 77 | Dead |

| 2021 | Cuesta-Llavona | March–December/2020 | Spain | Caucasian (Asturias) | 484 | 276 (0.57) | 114 | Alive | 38 | Dead | |

| Other | 2020 | Zhang | January–February/2020 | China | — | 80 | 33 (0.41) | 56 | Mild (hospitalized with fever, respiratory symptoms, and pneumonia seen with imaging) | 24 | Severe (RR ≥30/min; SpO2 ≤93%; PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mmHg; mechanical ventilation or ICU) |

| 2021 | Alghamdi | — | Saudi Arabia | Saudi | 861 | — | 457 | Nonhospitalized | 374 | Hospitalized | |

Note. RR, respiratory rate; ICU, intensive care unit; SpO2, oxygen saturation; PaO2/FiO2, arterial oxygen pressure/fraction of inspired oxygen.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot illustrating IFITM3 rs12252 association with severity (non-ICU × ICU). No significant results were observed. Case and control definitions are presented in Table 3. (A) C allele association. (B) C recessive model. (C) T recessive model.

TABLE 4.

Association studies of TNF-α rs1800629 gene with COVID-19 prognosis or susceptibility included in the systematic review.

| Year | Author | Sample | Control | Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | Ethnic background | Size | Male n(%) | n | Criteria | n | Criteria | ||

| 2020 | Saleh | April—July/2020 | Egypt | — | 1,084 | 600 (0.56) | 184 | Health care workers | 900 | COVID-19 positive |

| 900 | - | 444 | Mild | 456 | Severe | |||||

| 900 | 504 (0.56) | 840 | Alive | 60 | Dead | |||||

| 2021 | Nia | June/2020—January/2021 | Iran | — | 550 | 234 (0.43) | 275 | COVID-19 negative | 275 | Hospitalized |

| 275 | 112 (0.41) | 96 | Nonsevere | 179 | Severe | |||||

| 275 | - | 249 | Alive | 26 | Dead | |||||

| 2021 | Fishchuk | April–June/2020 | Ukraine | — | 31 | 16 (0.50) | 25 | Alive | 6 | Dead |

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot illustrating TNF-α rs1800629 association with death (alive × dead). No significant results were observed under the random model. Case and control definitions are presented in Table 5. (A) C allele association. (B) C recessive model. (C) T recessive model.

TABLE 5.

Association studies of FURIN gene with COVID-19 prognosis or susceptibility included in the systematic review.

| Year | Author | Sample | Control | Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | Ethnic background | Size | Male n(%) | n | Criteria | n | Criteria | ||

| 2020 | Latini | Mar—May/2020 | Italy | — | — | — | — | Severe (respiratory impairment, requiring noninvasive ventilation) | — | Extremely severe (requiring invasive ventilation and ICU) |

| 131 | 82 (0.63) | — | Asymptomatic | — | Severe and extremely severe | |||||

| 2021 | Torre-Fuentes | — | Spain | — | 120 | - | 113 | COVID-19 negative | 7 | COVID-19 positive |

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review followed by meta-analysis including studies covering genetic association of COVID-19 susceptibility or prognosis with IFITM3, FURIN, ACE1, and TNF-α variants. Four studies included in the meta-analyses did not report the sample collection date, which is of particular interest in COVID-19 studies due to the emergence of variants of concern (VOCs) in the last part of 2020 (Konings et al., 2021). Some VOCs have been associated with higher viral load, worse prognosis, and lethality (Davies et al., 2021; Faria et al., 2021), thus, confounding factors when evaluating genetic effects. Age can also be a confounding factor for COVID-19 association analysis (Fernández Villalobos et al., 2021). Most studies failed to conduct age-corrected estimation or even describe age separately for case and control groups. The same trend was observed for comorbidities (data now shown).

Ancestrality could also contribute to COVID-19 outcomes. Several studies do not present the ethnic background or, at least, the place of birth of the included subjects. Although heterogeneity was seen in parameters associated with ancestrality, the literature fails on genetic background diversity, an issue already raised for genomic data before (Popejoy and Fullerton, 2016). Another literature issue that needs attention is the selective reporting biases leading to the more likely publication of positive findings (Munafò et al., 2009; Sagoo et al., 2009).

We did not find an association of IFITM3 rs12252 with Covid-19 severity. Our results corroborate the most extensive association study published to date since no significance was reported on any of chromosome 11 loci (Niemi et al., 2021). However, the second evaluated polymorphism, the ACE1 rs4646994, showed significant effects with homozygous D carriers presenting higher odds of developing severe COVID-19. Several hits on the large arm of chromosome 17 have been previously reported (Niemi et al., 2021), although their genomic location is too far to hypothesize linkage disequilibrium. It is important to note that genome-wide data may find hits on loci that not necessarily are the ones harboring the causative variants because of its experimental design (Spencer et al., 2009). Furthermore, candidate-gene, whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing studies are more suitable in exploring large indel variants.

The ACE1 rs4646994 has been associated with several clinical phenotypes, including COVID-19 (Castellon and Hamdi, 2007; Li et al., 2021). Most previous findings report associations with COVID-19 outcomes on a population level, indicating high variability on allelic frequencies across different populations (Delanghe et al., 2020; Pati et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2020). On a molecular level, expression results indicate increased levels of ACE1 in D-allele carriers (Suehiro et al., 2004) with increased angiotensin II production (Hamdi and Castellon, 2004) and decreased ACE2 protein levels in lung tissue, thereby potentially affecting infectivity by SARS-CoV-2 (Jacobs et al., 2021). Our group has previously indicated that lower ACE2 levels may increase the risk of COVID-19 respiratory distress (Rossi et al., 2021). Although there is a robust biological hypothesis linking ACE1 rs4646994 with COVID-19, further reports are needed to understand better whether ACE1 variants could contribute to COVID-19 severity. Moreover, studies are still required to adequately evaluate IFITM3, FURIN, and TNF-α genetic variants’ role in COVID-19 susceptibility and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

JA receives a FAPEMIG graduate fellowship. RA and RS are CNPq-Brazil Research Fellows.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

RS wrote the systematic review protocol. JA, DM, and RS conducted the systematic review. JA, RA, and RS drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.775246/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akbari M., Taheri M., Mehrpoor G., Eslami S., Hussen B. M., Ghafouri-Fard S., et al. (2022). Assessment of ACE1 Variants and ACE1/ACE2 Expression in COVID-19 Patients. Vasc. Pharmacol. 142, 106934. 10.1016/j.vph.2021.106934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladag E., Tas Z., Ozdemir B. S., Akbaba T. H., Akpınar M. G., Goker H., et al. (20212021). Human Ace D/I Polymorphism Could Affect the Clinicobiological Course of COVID-19. J. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2021, 1–7. 10.1155/2021/5509280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi J., Alaamery M., Barhoumi T., Rashid M., Alajmi H., Aljasser N., et al. (2021). Interferon-induced Transmembrane Protein-3 Genetic Variant Rs12252 Is Associated with COVID-19 Mortality. Genomics 113, 1733–1741. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S., Choi Y. J., Lee J. H., Shi M., Huang I.-C., Farzan M., et al. (2013). The Antiviral Effector IFITM3 Disrupts Intracellular Cholesterol Homeostasis to Block Viral Entry. Cell Host & Microbe 13, 452–464. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata A., Coppola A., di Spirito V., Cauteruccio R., Marotta A., Micco P. D., et al. (2021). The Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Deletion/Deletion Genotype Is a Risk Factor for Severe COVID-19: Implication and Utility for Patients Admitted to Emergency Department. Medicina 57, 844. 10.3390/medicina57080844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo J. L., Menezes D., Saraiva‐Duarte J. M., Ferreira L., Aguiar R., Souza R. (2021). Systematic Review of Host Genetic Association with Covid‐19 Prognosis and Susceptibility: What Have We Learned in 2020? Rev. Med. Virol. 32, e2283. 10.1002/rmv.2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero C., Rosapepe F., Palmirotta R., Re A., Ottaiano M. P., Benincasa G., et al. (2021). Angiotensin System Polymorphisms' in SARS-CoV-2 Positive Patients: Assessment between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients: A Pilot Study. Pgpm 14, 621–629. 10.2147/PGPM.S303666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellon R., Hamdi H. (2007). Demystifying the ACE Polymorphism: From Genetics to Biology. Cpd 13, 1191–1198. 10.2174/138161207780618902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Llavona E., Albaiceta G. M., García-Clemente M., Duarte-Herrera I. D., Amado-Rodríguez L., Hermida-Valverde T., et al. (2021). Association between the Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3 Gene (IFITM3) Rs34481144/Rs12252 Haplotypes and COVID-19. Curr. Res. Virol. Sci. 2, 100016. 10.1016/j.crviro.2021.100016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N. G., Jarvis C. I., Jarvis C. I., Edmunds W. J., Jewell N. P., Diaz-Ordaz K., et al. (2021). Increased Mortality in Community-Tested Cases of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B.1.1.7. Nature 593, 270–274. 10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb P., Zannat K. e., Talukder S., Bhuiyan A. H., Jilani M. S. A., Saif‐Ur‐Rahman K. M. (2022). Association of HLA Gene Polymorphism with Susceptibility, Severity, and Mortality of COVID ‐19: A Systematic Review. Hla. [online ahead of print]. 10.1111/tan.14560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanghe J. R., Speeckaert M. M., de Buyzere M. L. (2020). The Host's Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Polymorphism May Explain Epidemiological Findings in COVID-19 Infections. Clinica Chim. Acta 505, 192–193. 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria N. R., Mellan T. A., Whittaker C., Claro I. M., Candido D. D. S., Mishra S., et al. (2021). Genomics and Epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 Lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 372, 815–821. 10.1126/science.abh2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Villalobos N. V., Ott J. J., Klett-Tammen C. J., Bockey A., Vanella P., Krause G., et al. (2021). Effect Modification of the Association between Comorbidities and Severe Course of COVID-19 Disease by Age of Study Participants: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 10, 194. 10.1186/s13643-021-01732-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishchuk L., Rossokha Z., Pokhylko V., Cherniavska Y., Tsvirenko S., Kovtun S., et al. (2021). Modifying Effects of TNF-α, IL-6 and VDR Genes on the Development Risk and the Course of COVID-19. Pilot Study. Drug Metab. Personalized Ther. [online ahead of print]. 10.1515/dmpt-2021-0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez J., Albaiceta G. M., Cuesta-Llavona E., García-Clemente M., López-Larrea C., Amado-Rodríguez L., et al. (2021). The Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3 Gene (IFITM3) Rs12252 C Variant Is Associated with COVID-19. Cytokine 137, 155354. 10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez J., Albaiceta G. M., García-Clemente M., López-Larrea C., Amado-Rodríguez L., Lopez-Alonso I., et al. (2020). Angiotensin-converting Enzymes (ACE, ACE2) Gene Variants and COVID-19 Outcome. Gene 762, 145102. 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong P., Mei F., Li R., Wang Y., Li W., Pan K., et al. (2022). Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Genotype-specific Immune Response Contributes to the Susceptibility of COVID-19: A Nested Case-Control Study. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 759587. 10.3389/fphar.2021.759587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunal O., Sezer O., Ustun G. U., Ozturk C. E., Sen A., Yigit S., et al. (2021). Angiotensin-converting Enzyme-1 Gene Insertion/deletion Polymorphism May Be Associated with COVID-19 Clinical Severity: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Saudi Med. 41, 141–146. 10.5144/0256-4947.2021.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi H. K., Castellon R. (2004). A Genetic Variant of ACE Increases Cell Survival: a New Paradigm for Biology and Disease. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 318, 187–191. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashan M. R., Ghozy S., El‐Qushayri A. E., Pial R. H., Hossain M. A., al Kibria G. M. (2021). Association of Dengue Disease Severity and Blood Group: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Rev. Med. Virol. 31, 1–9. 10.1002/rmv.2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley A. T., McCarthy M. I. (2005). What Makes a Good Genetic Association Study? The Lancet 366, 1315–1323. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67531-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Nia M., Rokni M., Mirinejad S., Kargar M., Rahdar S., Sargazi S., et al. (2021). Association of Polymorphisms in Tumor Necrosis Factors with SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection and Mortality Rate: A Case‐control Study and In Silico Analyses. J. Med. Virol 94, 1502–1512. 10.1002/jmv.27477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubacek J. A., Dusek L., Majek O., Adamek V., Cervinkova T., Dlouha D., et al. (2021). ACE I/D Polymorphism in Czech First-Wave SARS-CoV-2-Positive Survivors. Clinica Chim. Acta 519, 206–209. 10.1016/j.cca.2021.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J. P. A., Ntzani E. E., Trikalinos T. A., Contopoulos-Ioannidis D. G. (2001). Replication Validity of Genetic Association Studies. Nat. Genet. 29, 306–309. 10.1038/ng749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M., Lahousse L., van Eeckhoutte H. P., Wijnant S. R. A., Delanghe J. R., Brusselle G. G., et al. (2021). Effect of ACE1 Polymorphism Rs1799752 on Protein Levels of ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor, in Alveolar Lung Epithelium. ERJ Open Res. 7, 00940–02020. 10.1183/23120541.00940-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaş Çelik S., Çakmak Genç G., Pişkin N., Açikgöz B., Altinsoy B., Kurucu İşsiz B., et al. (2021). Polymorphisms of ACE (I/D) and ACE2 Receptor Gene (Rs2106809, Rs2285666) Are Not Related to the Clinical Course of COVID‐19: A Case Study. J. Med. Virol. 93, 5947–5952. 10.1002/jmv.27160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki R., Kanneganti T.-D. (2021). The 'cytokine Storm': Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Prospects. Trends Immunol. 42, 681–705. 10.1016/j.it.2021.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konings F., Perkins M. D., Kuhn J. H., Pallen M. J., Alm E. J., Archer B. N., et al. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Interest and Concern Naming Scheme Conducive for Global Discourse. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 821–823. 10.1038/s41564-021-00932-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouhpayeh H. R., Tabasi F., Dehvari M., Naderi M., Bahari G., Khalili T., et al. (2021). Association between Angiotensinogen (AGT), Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) and Angiotensin-II Receptor 1 (AGTR1) Polymorphisms and COVID-19 Infection in the Southeast of Iran: a Preliminary Case-Control Study. Transl Med. Commun. 6, 26. 10.1186/s41231-021-00106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini A., Agolini E., Novelli A., Borgiani P., Giannini R., Gravina P., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and Genetic Variants of Protein Involved in the SARS-CoV-2 Entry into the Host Cells. Genes 11, 1010. 10.3390/genes11091010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Schifanella L., Larsen P. A. (2021). Alu Retrotransposons and COVID-19 Susceptibility and Morbidity. Hum. Genomics 15, 2. 10.1186/s40246-020-00299-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Kong C., Wu J., Ying H., Zhu H. (2012). Effect of CCR5-Δ32 Heterozygosity on HIV-1 Susceptibility: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e35020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood Z. S., Fadhil H. Y., Abdul Hussein T. A., Ad'hiah A. H. (2022). Severity of Coronavirus Disease 19: Profile of Inflammatory Markers and ACE (Rs4646994) and ACE2 (Rs2285666) Gene Polymorphisms in Iraqi Patients. Meta Gene 31, 101014. 10.1016/j.mgene.2022.101014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir M. M., Mir R., Alghamdi M. A. A., Alsayed B. A., Wani J. I., Alharthi M. H., et al. (2021). Strong Association of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 Gene Insertion/deletion Polymorphism with Susceptibility to Sars-Cov-2, Hypertension, Coronary Artery Disease and Covid-19 Disease Mortality. Jpm 11, 1098. 10.3390/jpm11111098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Booth A., Stewart L. (2014). How to Reduce Unnecessary Duplication: Use PROSPERO. Bjog: Int. J. Obstet. Gy 121, 784–786. 10.1111/1471-0528.12657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möhlendick B., Schönfelder K., Breuckmann K., Elsner C., Babel N., Balfanz P., et al. (2021). ACE2 Polymorphism and Susceptibility for SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Severity of COVID-19. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 31, 165–171. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafò M. R., Stothart G., Flint J. (2009). Bias in Genetic Association Studies and Impact Factor. Mol. Psychiatry 14, 119–120. 10.1038/mp.2008.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasserie T., Hittle M., Goodman S. N. (2021). Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2111417. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemi M. E. K., Karjalainen J., Liao R. G., Neale B. M., Daly M., Ganna A., et al. (2021). Mapping the Human Genetic Architecture of COVID-19. Nature 600, 472–477. 10.1038/s41586-021-03767-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 Statement: an Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou A., Fragkou P. C., Maratou E., Dimopoulou D., Kominakis A., Kokkinopoulou I., et al. (2022). Angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme Insertion/deletion Polymorphism, ACE Activity, and COVID‐19: A rather Controversial Hypothesis. A Case‐control Study. J. Med. Virol. 94, 1050–1059. 10.1002/jmv.27417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pati A., Mahto H., Padhi S., Panda A. K. (2020). ACE Deletion Allele Is Associated with Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Mortality Rate: An Epidemiological Study in the Asian Population. Clinica Chim. Acta 510, 455–458. 10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock T. P., Goldhill D. H., Zhou J., Baillon L., Frise R., Swann O. C., et al. (2021). The Furin Cleavage Site in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Is Required for Transmission in Ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 899–909. 10.1038/s41564-021-00908-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popejoy A. B., Fullerton S. M. (2016). Genomics Is Failing on Diversity. Nature 538, 161–164. 10.1038/538161a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S. S., Chakraborty T. T., Kumar N., Banerjee I. (2018). Association between IFITM3 Rs12252 Polymorphism and Influenza Susceptibility and Severity: A Meta-Analysis. Gene 674, 70–79. 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praissman J. L., Wells L. (2021). Proteomics-Based Insights into the SARS-CoV-2-Mediated COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the First Year of Research. Mol. Cell Proteomics 20, 100103. 10.1016/j.mcpro.2021.100103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelli Bozzo C., Nchioua R., Volcic M., Koepke L., Krüger J., Schütz D., et al. (2021). IFITM Proteins Promote SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Are Targets for Virus Inhibition In Vitro . Nat. Commun. 12, 4584. 10.1038/s41467-021-24817-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014). R Core Team (2014). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: : http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi Á. D., de Araújo J. L. F., de Araújo J. L. F., de Almeida T. B., Ribeiro-Alves M., de Almeida Velozo C., et al. (2021). Association between ACE2 and TMPRSS2 Nasopharyngeal Expression and COVID-19 Respiratory Distress. Sci. Rep. 11, 9658. 10.1038/s41598-021-88944-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad H., Jabotian K., Sakr C., Mahfouz R., Akl I. B., Zgheib N. K. (2021). The Role of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 1 Insertion/Deletion Genetic Polymorphism in the Risk and Severity of COVID-19 Infection. Front. Med. 8, 798571. 10.3389/fmed.2021.798571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagoo G. S., Little J., Higgins J. P. T. (2009). Systematic Reviews of Genetic Association Studies. Plos Med. 6, e1000028. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A., Sultan A., Elashry M. a., Farag A., Mortada M. I., Ghannam M. A., et al. (2020). Association of TNF-α G-308 a Promoter Polymorphism with the Course and Outcome of COVID-19 Patients. Immunological Invest., 1–12. 10.1080/08820139.2020.1851709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samprathi M., Jayashree M. (2021). Biomarkers in COVID-19: An Up-To-Date Review. Front. Pediatr. 8, 607647. 10.3389/fped.2020.607647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfelder K., Breuckmann K., Elsner C., Dittmer U., Fistera D., Herbstreit F., et al. (2021). The Influence of IFITM3 Polymorphisms on Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Severity of COVID-19. Cytokine 142, 155492. 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohani Z. N., Sarma S., Alyass A., de Souza R. J., Robiou-du-Pont S., Li A., et al. (2016). Empirical Evaluation of the Q-Genie Tool: a Protocol for Assessment of Effectiveness. BMJ Open 6, e010403. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer C. C. A., Su Z., Donnelly P., Marchini J. (2009). Designing Genome-wide Association Studies: Sample Size, Power, Imputation, and the Choice of Genotyping Chip. Plos Genet. 5, e1000477. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K., Insel P. A. (2020). A Hypothesis for Pathobiology and Treatment of COVID‐19 : The Centrality of ACE1/ACE2 Imbalance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177, 4825–4844. 10.1111/bph.15082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing J., Phelan A., Griffin I., Tucker C., Oechsle O., Smith D., et al. (2020). COVID-19: Combining Antiviral and Anti-inflammatory Treatments. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 400–402. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suehiro T., Morita T., Inoue M., Kumon Y., Ikeda Y., Hashimoto K. (2004). Increased Amount of the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) mRNA Originating from the ACE Allele with Deletion. Hum. Genet. 115, 91. 10.1007/s00439-004-1136-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. F. (2007). Spurious Genetic Associations. Biol. Psychiatry 61, 1121–1126. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre‐Fuentes L., Matías‐Guiu J., Hernández‐Lorenzo L., Montero‐Escribano P., Pytel V., Porta‐Etessam J., et al. (2021). ACE2, TMPRSS2 , and Furin Variants and SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection in Madrid, Spain. J. Med. Virol. 93, 863–869. 10.1002/jmv.26319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S., Abbas M., Verma S., Khan F. H., Raza S. T., Siddiqi Z., et al. (2021). Impact of I/D Polymorphism of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 1 (ACE1) Gene on the Severity of COVID-19 Patients. Infect. Genet. Evol. 91, 104801. 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N., Ariumi Y., Nishida N., Yamamoto R., Bauer G., Gojobori T., et al. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Infections and COVID-19 Mortalities Strongly Correlate with ACE1 I/D Genotype. Gene 758, 144944. 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Qin L., Zhao Y., Zhang P., Xu B., Li K., et al. (2020). Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3 Genetic Variant Rs12252-C Associated with Disease Severity in Coronavirus Disease 2019. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 34–37. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.