Abstract

Because of antibiotic prophylaxis for necrotizing pancreatitis, the frequency of fungal superinfection in patients with pancreatic necrosis is increasing. In this study we analyzed the penetration of fluconazole into the human pancreas and in experimental acute pancreatitis. In human pancreatic tissues, the mean fluconazole concentration was 8.19 ± 3.38 μg/g (96% of the corresponding concentration in serum). In experimental edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis, 88 and 91% of the serum fluconazole concentration was found in the pancreas. These data show that fluconazole penetration into the pancreas is sufficient to prevent and/or treat fungal contamination in patients with pancreatic necrosis.

Bacterial and fungal contamination in patients with pancreatic necrosis is now the most important cause of a fatal outcome in severe acute pancreatitis (4, 6). Studies conducted before antibiotics were regularly used documented bacterial contamination of necrotic pancreatic tissue in 40 to 70% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis (2, 3, 5, 12, 17, 19). Prophylactic treatment with antibiotics which penetrate into the pancreas and which cover the spectrum of bacteria found in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis prevents or delays bacterial infection of necrotic pancreatic tissue (7, 8, 18, 21, 23, 24).

In recent years, however, it has been noticed that antibiotic prophylaxis in necrotizing pancreatitis causes a significant shift towards fungi in the microbial spectrum of the infected necrotic pancreatic tissue. Although the overall frequency of fungal contamination was approximately 7% of all pancreatic infections in the period before antibiotics were used prophylactically (5), this frequency has increased to 40% since the use of prophylactic antibiotic regimens (1, 13). In patients with necrotizing pancreatitis this situation raises the question of whether addition of antifungal agents to the antibiotic prophylaxis could decrease the fungal infection rate in patients with pancreatic necrosis and the morbidity and mortality attributed to it (14). A prerequisite for the use of antifungals would be their proven adequate penetration into the pancreas. Therefore, we evaluated concentrations in serum and pancreatic tissue of the antifungal agent fluconazole in the human pancreas and in experimental acute pancreatitis.

In 15 patients undergoing pancreatic surgery (10 with periampullary tumors, 4 with chronic pancreatitis, and 1 other), 400 mg of fluconazole was given by a 2-h intravenous infusion. Serum fluconazole levels were measured before infusion, after 1 h, at the end of the fluconazole infusion, and at the time of pancreatic tissue or juice sampling. In addition, fluconazole concentrations were measured in the resected pancreas, pancreatic juice, and cyst fluid.

Fluconazole penetration was also analyzed in experimental edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis (n = 4), which was induced as reported before (15). To rats kept awake in single cages, fluconazole (0.57 mg/100 g of body weight) was given intravenously as a bolus injection 48 or 6 h after the induction of edematous or necrotizing pancreatitis, respectively, because after these time points pancreatitis is completely established. Two hours later, serum and pancreatic tissue fluconazole concentrations were determined.

The determination of fluconazole levels was carried out using the gas chromatographic method with electron capture detection and internal standardization, as previously reported in detail (10). Calibration curves were between 0.01 and 0.4 μg of fluconazole/g for tissue samples and 1 and 160 μg/ml for fluid samples. In serum analysis the coefficient of variation was between 2.1 and 4.2% and the accuracy was between 99.1 and 109.4%. In tissue analysis the coefficient of variation was between 4.4 and 9.3% and the accuracy was between 98.4 and 105.8%. Quality control samples at three different concentrations of fluconazole were included in each batch.

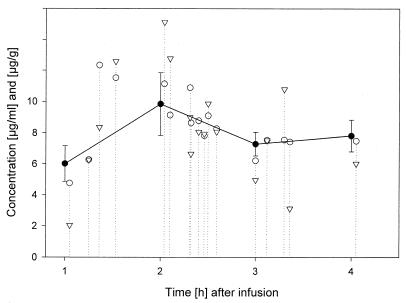

The serum fluconazole concentrations (mean ± standard deviations) in patients at the end of 1, 2, 3, and 4 h were 6.19 ± 1.30, 10.40 ± 2.06, 7.54 ± 0.91, and 7.82 ± 1.01 μg/ml, respectively. Pancreatic tissue samples were obtained at 162 ± 52 min after the start of fluconazole infusion. At this time point, the serum fluconazole concentration was 8.52 ± 2.03 μg/ml. In comparison, the mean fluconazole concentration (mean ± standard deviation) in pancreatic tissue samples was 8.19 ± 3.38 μg/g of tissue (range, 2.04 to 15.13 μg/g). Tissue samples taken between 1 and 2 h, >2 and 3 h, and >3 h after the start of fluconazole infusion had fluconazole concentrations of 7.31 ± 4.38, 9.07 ± 3.30, and 7.47 ± 3.07 μg/g, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, while overall the levels in serum were higher than the levels in pancreatic tissue, in some instances, especially 2 h after the initiation of the fluconazole infusion, the levels in pancreatic tissue rose above the levels in serum, and the drug appeared to remain in the pancreatic tissue for a period of over 4 h after the infusion. In two pancreatic juice samples, the fluconazole concentrations were 3.30 μg/ml (80 min after the start of infusion) and 11.43 μg/ml (149 min after the start of infusion), and the corresponding concentrations in serum were 7.61 and 13.28 μg/ml, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Fluconazole concentration in serum and pancreatic tissue samples from humans. The solid dots represent the mean serum fluconazole concentration measured in 1-h steps after the start of fluconazole infusion. Open triangles represent the tissue fluconazole concentrations, and open dots represent the corresponding serum fluconazole concentrations.

In two pancreatic pseudocyst fluids, the fluconazole concentrations were 0.81 μg/ml (sample obtained 149 min after initiation of fluconazole infusion) and 1.57 μg/ml (sample obtained 163 min after initiation of fluconazole infusion), and the corresponding concentration in serum was 13.28 μg/ml. In untreated control rats 2 h after bolus injection of fluconazole, the serum fluconazole concentration was 6.10 ± 1.62 μg/ml, and the corresponding pancreatic tissue fluconazole concentration was 6.06 ± 2.17 μg/g, revealing a pancreatic penetration comparable to that in humans. In edematous pancreatitis the serum and pancreatic tissue fluconazole concentrations were 5.30 ± 1.03 μg/ml and 4.64 ± 1.09 μg/g, respectively. In rats with necrotizing pancreatitis, the serum and pancreatic tissue fluconazole concentrations were 8.44 ± 1.04 μg/ml and 7.68 ± 0.25 μg/g, respectively. Thus, in experimental edematous or necrotizing pancreatitis 88 and 91% of the serum fluconazole concentration was found in the inflamed pancreas.

Detailed studies have clearly demonstrated that fluconazole penetrates into various human tissues (11). However, the penetration of fluconazole into the pancreas has not been studied. In necrotizing pancreatitis with prophylactic antibiotic use, the frequency of fungal superinfection in patients with pancreatic necrosis is increasing. (For example, in a series of 180 patients with necrotizing pancreatitis, all of whom were treated prophylactically with imipenem, the frequency of fungal infection increased from less than 7% to approximately 40% [9, 13]). Thus, a frequently discussed issue in this context is whether patients with necrotizing pancreatitis should be prophylactically treated with antibiotics and antifungal agents simultaneously (14). However, before antifungal agents are put into clinical use, their ability to penetrate into the pancreas needs to be evaluated, because if these drugs do not penetrate into the pancreas (as has been shown for some antibiotics), their usefulness to prevent fungal contamination of the pancreas would be limited.

In the present study, the penetration capability of fluconazole was evaluated in patients undergoing pancreatic resection and in experimental edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis. Simultaneous measurement of pancreatic tissue and serum fluconazole concentrations revealed that fluconazole penetrates efficiently into the pancreas. The pancreatic fluconazole concentrations achieved were 37% higher than the MIC which is required to counter the various species of contaminating fungi or to treat fungal infection in acute pancreatitis (11, 16, 20, 22). The similarity in penetration capacities of fluconazole in the normal rat and human pancreas suggests that the penetration in experimental rat pancreatitis should imitate the clinical situation in human acute pancreatitis. When fluconazole penetration into the pancreas was analyzed in experimental edematous and necrotizing pancreatitis, it was found that pancreatic fluconazole concentrations reached approximately 90% of the corresponding levels in serum, indicating that even during acute pancreatic inflammation, adequate tissue penetration by fluconazole occurs. These experimental findings suggest that even in human acute pancreatitis, fluconazole penetration is likely to be sufficient to protect and to treat fungal infection of the pancreas.

A limitation of our analysis is that no patients with necrotizing pancreatitis were enrolled. However, the animal studies indicate sufficient penetration of fluconazole into the inflamed pancreas. Our data provide evidence that fluconazole is a good candidate to treat and/or to prevent fungal contamination in necrotizing pancreatitis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aloia T, Solomkin J, Fink A S, Nussbaum M S, Bjornson S, Bell R H, Sewak L, McFadden D W. Candida in pancreatic infection: a clinical experience. Am Surg. 1994;60:793–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassi C, Falconi M, Girelli R, Nifosi F, Elio A, Martini N, Pederzoli P. Microbiological findings in severe pancreatitis. Surg Res Commun. 1989;5:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker J M, Pemberton H, DiMagno E P, Ilstrup D M, McIlrath D C, Dozois R R. Prognostic factors in pancreatic abscess. Surgery. 1984;96:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beger H G. Surgical management of necrotizing pancreatitis. Surg Clin N Am. 1989;69:529–549. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beger H G, Bittner R, Block S, Büchler M W. Bacterial contamination of pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:433–438. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley E L. Later complications of acute pancreatitis. In: Glazer G, Ranson J H C, editors. Acute pancreatitis. London, United Kingdom: Balliere Tindall; 1988. pp. 390–431. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Büchler M W, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, Bittner R, Vanek E, Schlegel P, Beger H G. The penetration of antibiotics into the human pancreas. Infection. 1989;17:20–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01643494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büchler M W, Malfertheiner P, Friess H, Isenmann R, Vanek E, Grimm H, Schlegel P, Friess T, Beger H G. Human pancreatic tissue concentration of bactericidal antibiotics. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1902–1908. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91450-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büchler, M. W., B. Gloor, C. Müller, H. Friess, C. A. Seiler, and W. H. Uhl. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: treatment strategy according to the status of infection—results of a prospective unicenter trial. Ann. Surg., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Faergemann J, Laufen H. Levels of fluconazole in serum, stratum corneum, epidermis-dermis (without stratum corneum) and eccrine sweat. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:102–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischman A J, Alpert N M, Livni E, Ray S, Sinclair I, Callahan R J, Correia J A, Webb D, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fluconazole in healthy human subjects by positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1270–1277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerzof S G, Banks P A, Robbins A H, Johnson W C, Spechler S J, Wetzner S M, Snider J M, Langevin R E, Jay M E. Early diagnosis of pancreatic infection by computed tomography guided aspiration. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1315–1320. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gloor B, Uhl W, Müller C A, Mai G, Tcholakov O, Büchler M W. Antibiotic prophylaxis and delayed surgery improve the outcome in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:A1128. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grewe M, Tsiotos G G, Luque de-Leon E, Sarr M G. Fungal infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:408–414. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofbauer B, Friess H, Weber A, Baczako K, Kissling P, Uhl W, Dervenis C, Büchler M W. Hyperlipidemia intensifies the course of acute edematous and acute necrotizing pancreatitis in the rat. Gut. 1996;38:753–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes C E, Bennett R L, Tuna I C, Beggs W H. Activities of fluconazole (UK 49,858) and ketoconazole against ketoconazole-susceptible and -resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:209–212. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones C E, Polk H C, Fulton R L. Pancreatic abscess. Am J Surg. 1975;129:44–47. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luiten E J, Hop W C, Lange J F, Bruining H A. Controlled clinical trial of selective decontamination for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1995;222:57–65. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malangoni M A, Richardson J D, Shallcross J C, Seiler J C, Polk H C. Factors contributing to fatal outcome after treatment of pancreatic abscess. Ann Surg. 1986;203:605–613. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198606000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marriot M S, Richardson K. The discovery and mode of action of fluconazole. In: Fromberg R A, editor. Recent trends in the discovery, development and evaluation of antifungal agents. J. R. Barcelona, Spain: Prous Science Publishers, S.A.; 1987. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Vesentini S, Campedelli A. A randomized multicenter clinical trial of antibiotic prophylaxis of septic complications in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:480–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers T E, Galgiani J N. Activity of fluconazole (UK 49,858) and ketoconazole against Candida albicans in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:418–422. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.3.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sainio V, Kemppainen E, Puolakkainen P, Taavitsainen M, Kivisaari L, Valtonen V, Haapianen R, Schroder T, Kivilaakso E. Early antibiotic treatment in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Lancet. 1995;346:663–667. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl W, Isenmann R, Büchler M W. Infections complicating pancreatitis: diagnosing, treating, preventing. New Horiz. 1998;6(2 Suppl.):S72–S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]